Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

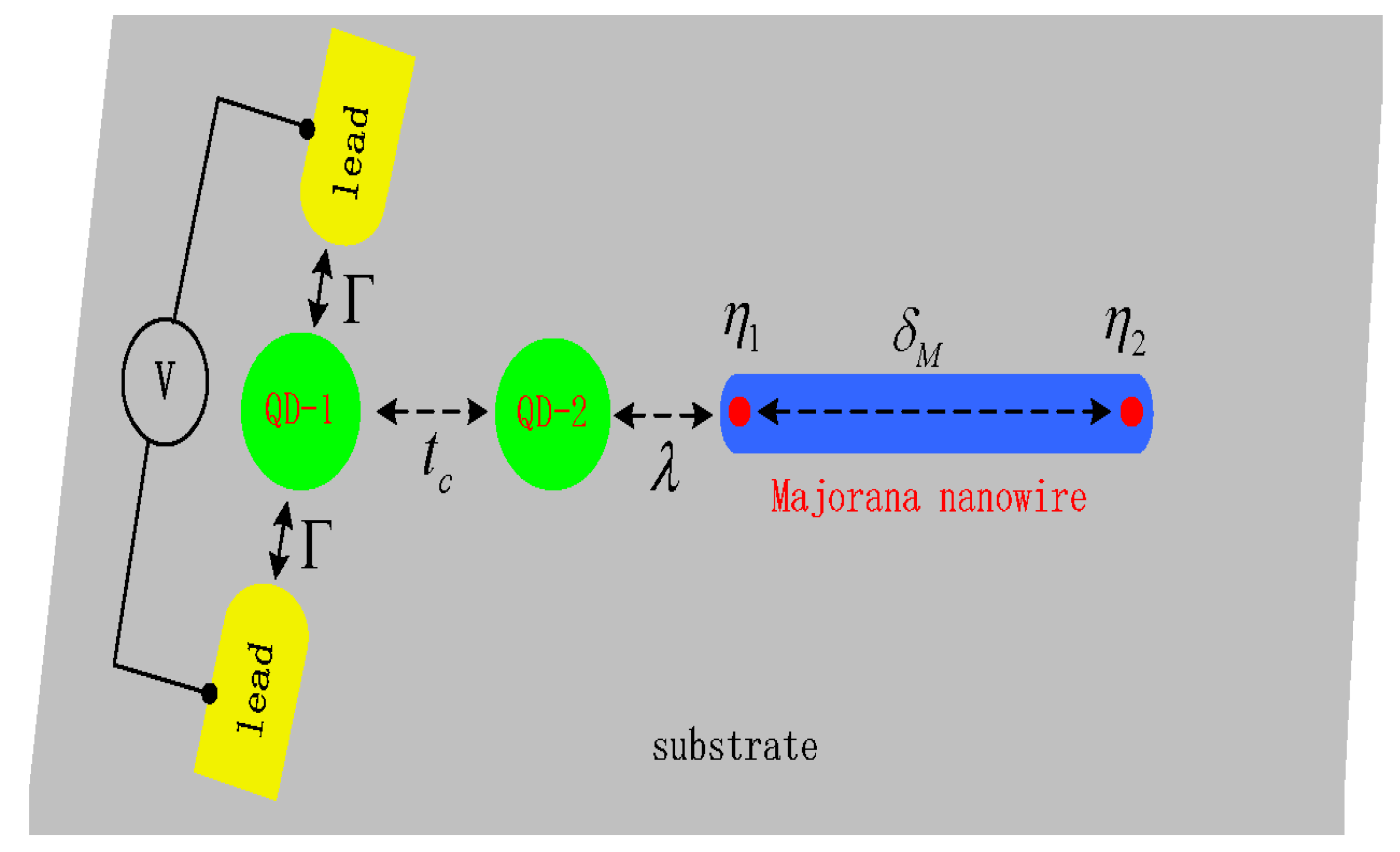

2. Model and Method

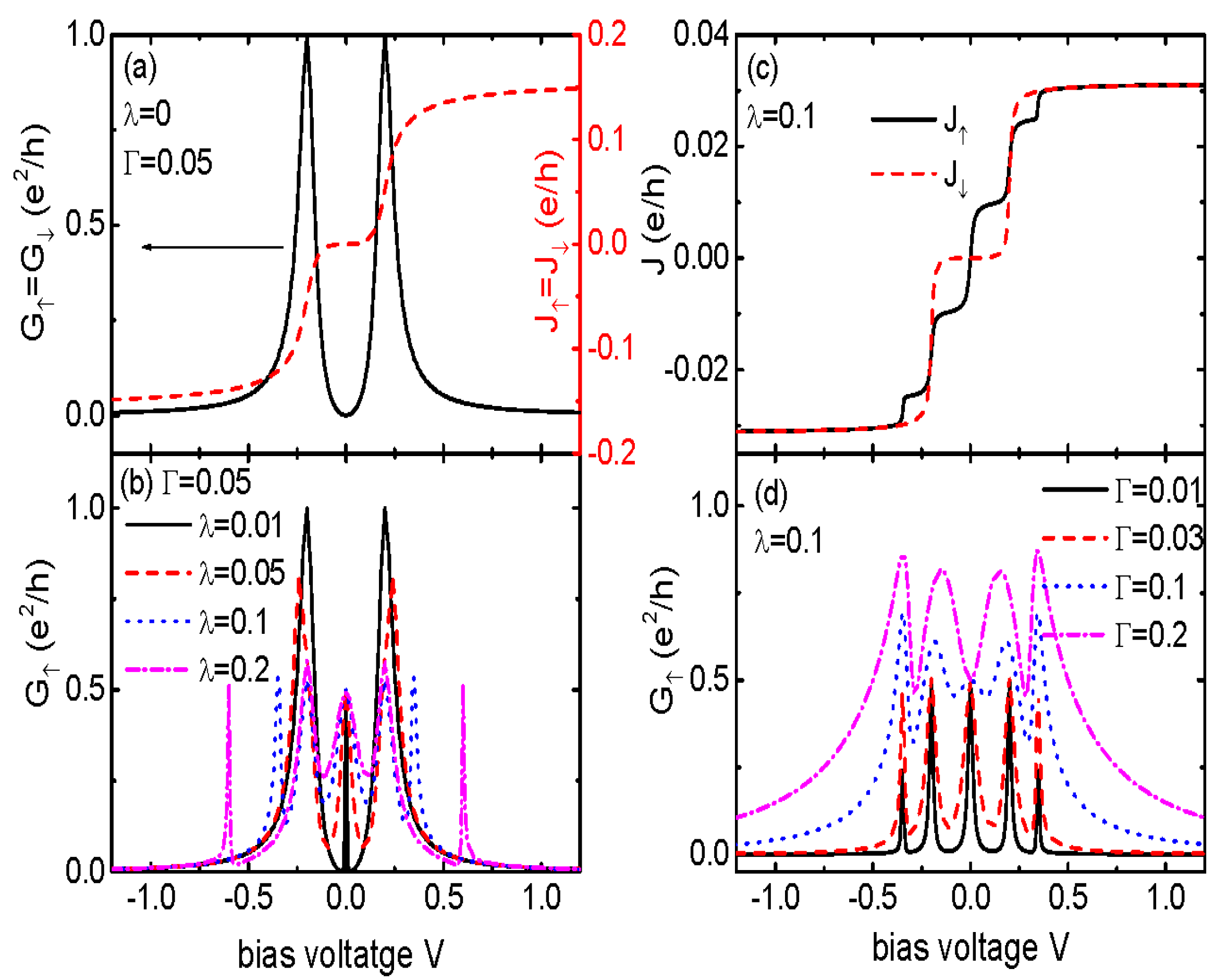

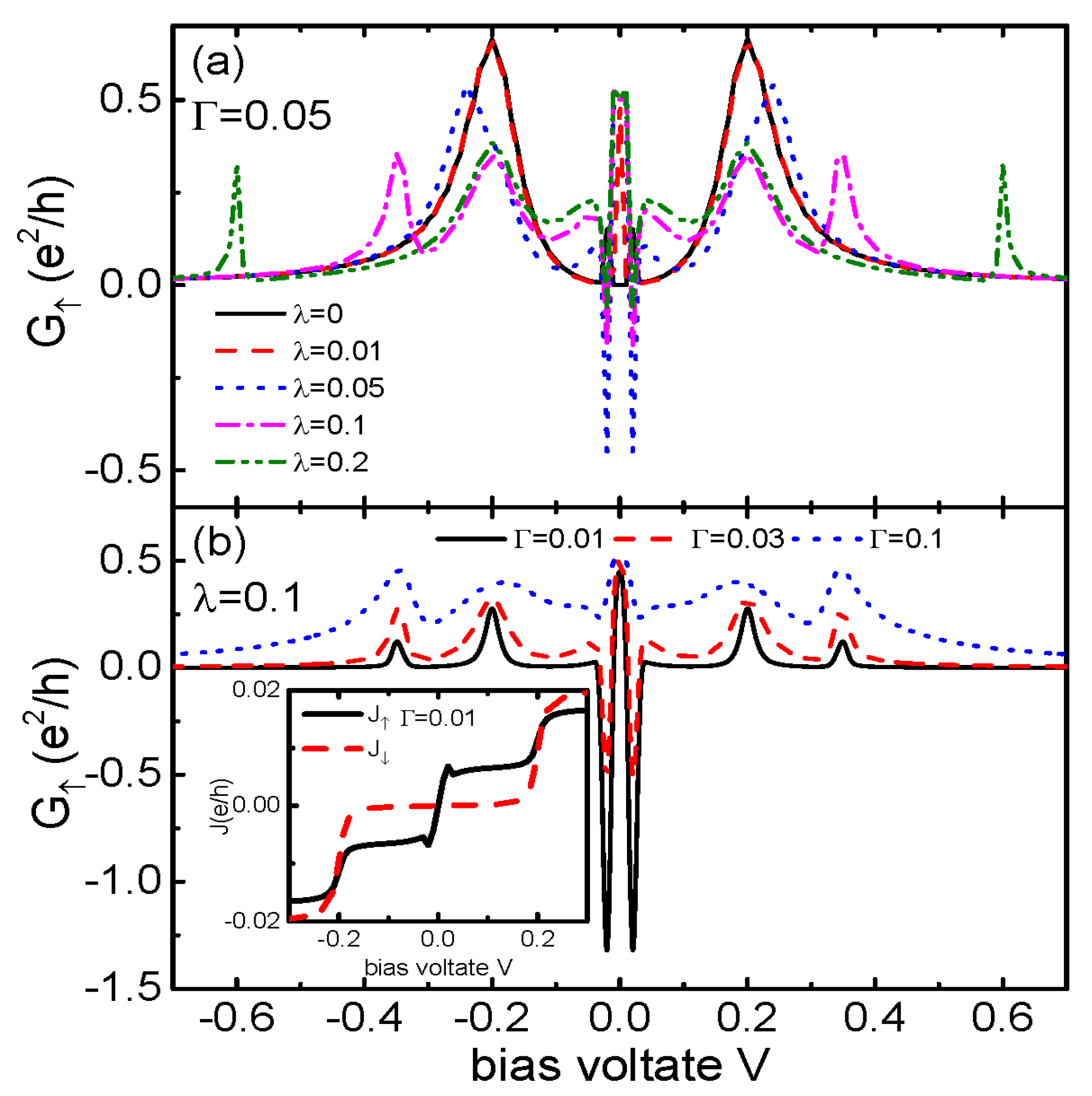

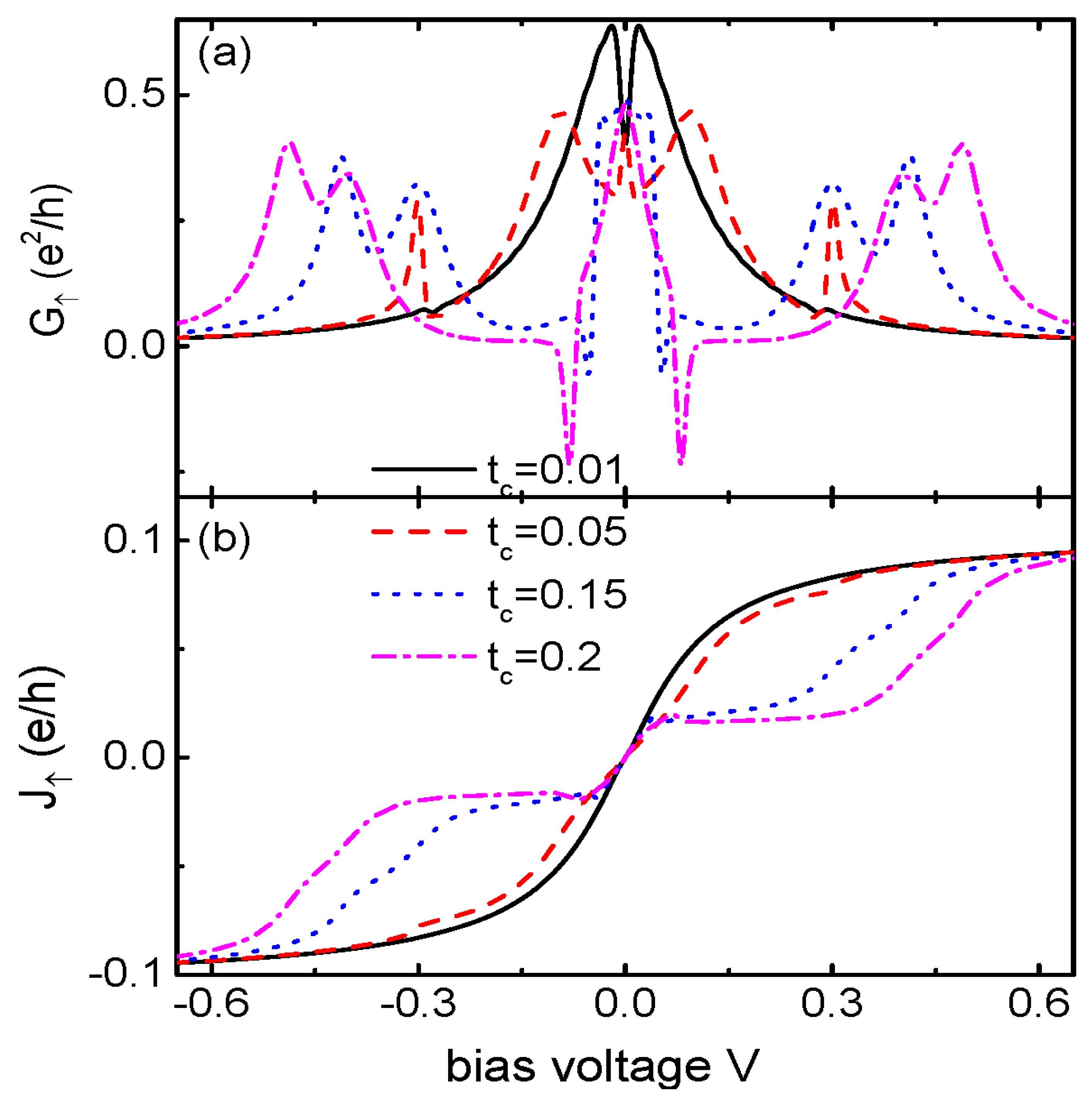

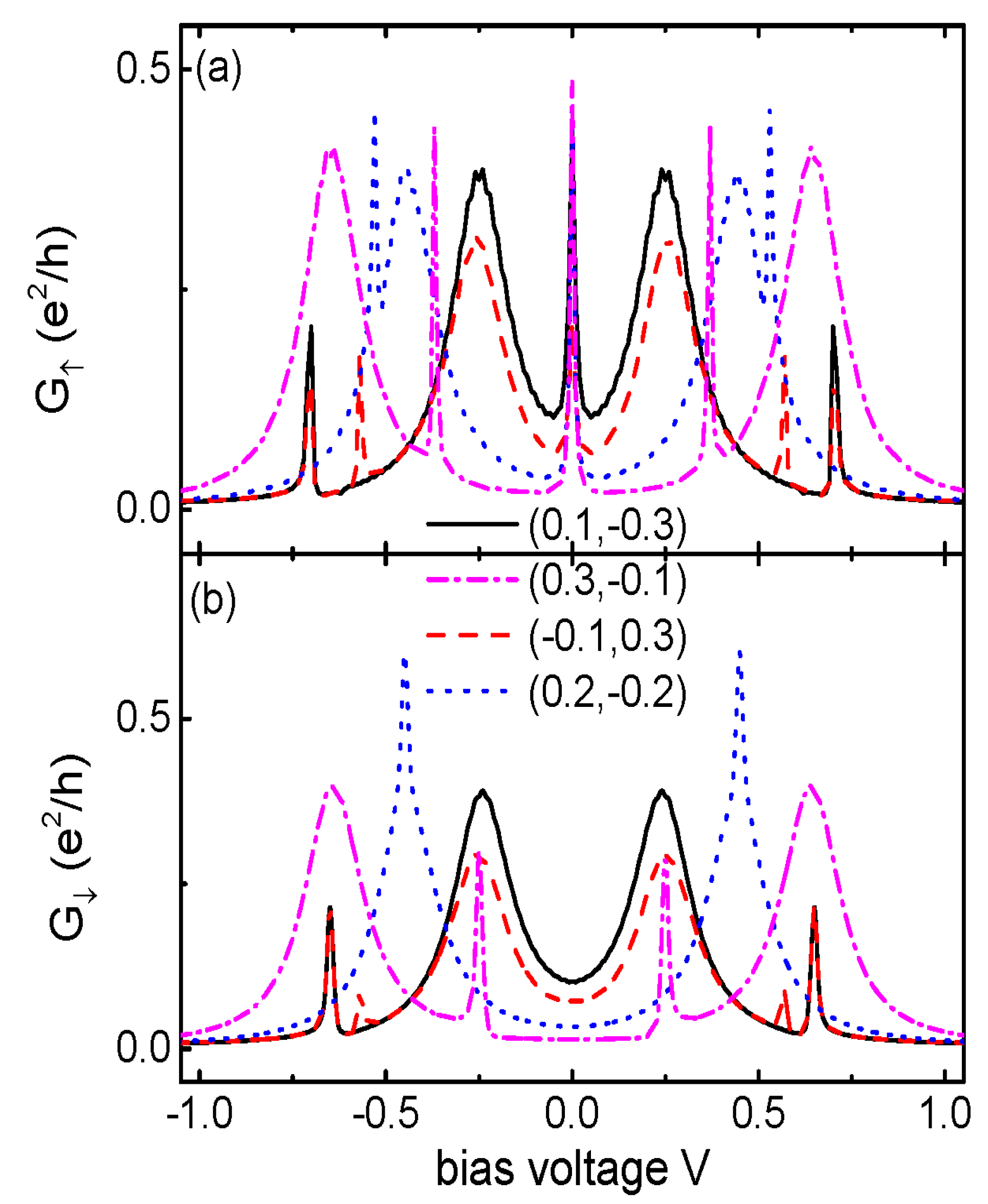

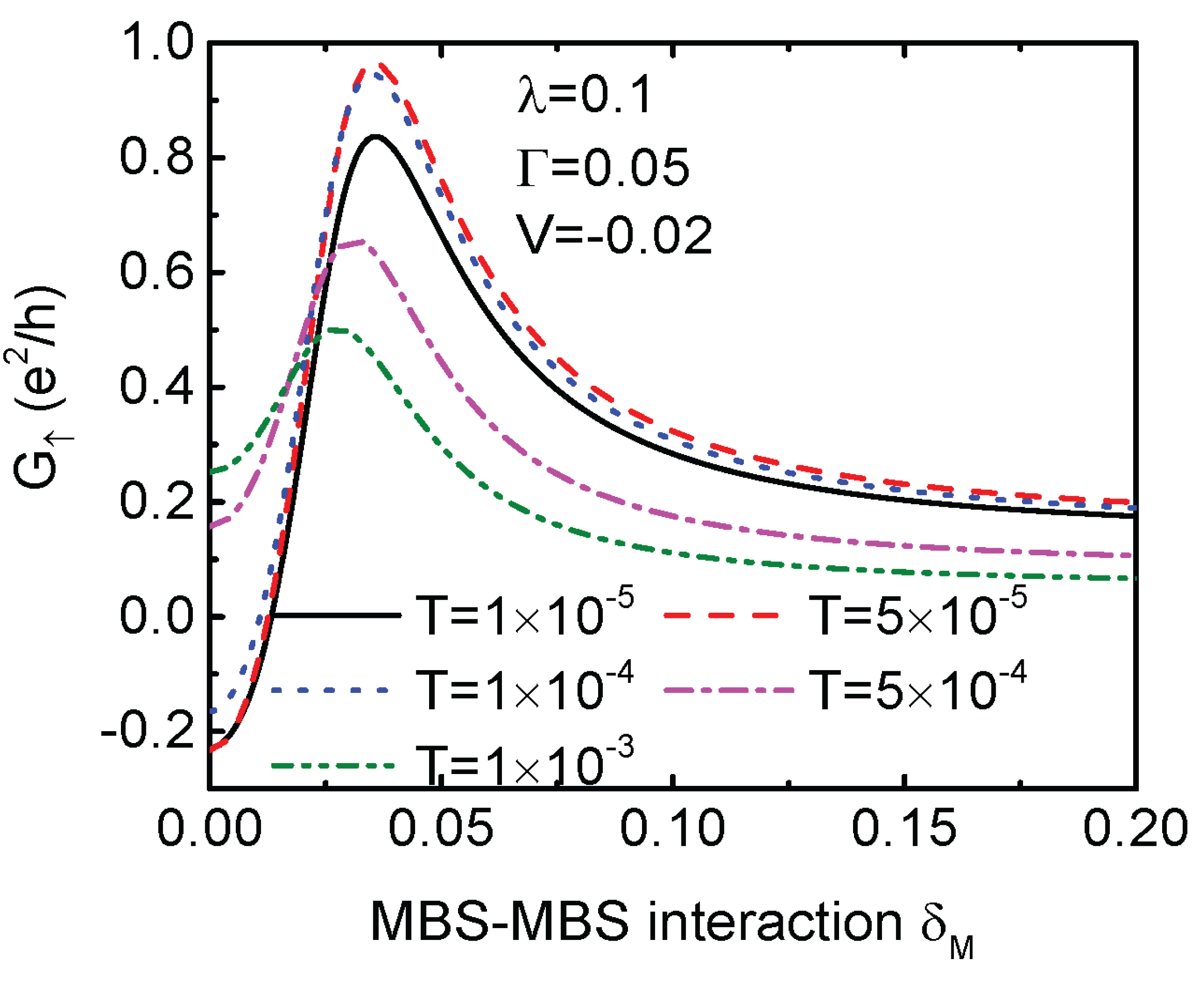

3. Numerical Results

4. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Read, N.; Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 10267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys.-Usp. 2001, 44, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.L.; Zhang, S.C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicea, J.; Oreg, Y.; Refael, G. Non-abelian statistics and topological quantum information processing in 1d wire networks. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, B.; Sun, X.Q.; Vaezi, A.; Zhang, S.C. Topological quantum computation based on chiral Majorana fermions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 10938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourik, V.; Zuo, K.; Frolov, S.M. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 2012, 336, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.T.; Yu, C.L.; Huang, G.Y.; Larsson, M.; Caroff, P.; Xu, H.Q. Anomalous Zero-Bias Conductance Peak in a Nb-InSb Nanowire-Nb Hybrid Device. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhinson, L.; Liu, X.; Furdyna, J. The fractional a.c. Josephson effect in a semiconductor-superconductor nanowire as a signature of Majorana particles. Nature Phys 2012, 8, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Kane, C.L. Superconducting Proximity Effect and Majorana Fermions at the Surface of a Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 096407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.P.; Wang, M.X.; Liu, Z.L. et al. Experimental detection of a Majorana mode in the core of a magnetic vortex inside a topological insulator-superconductor Bi2Te3/NbSe2 heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, J.D.; Lutchyn, R.M.; Tewari, S.; Das Sarma, S. Generic new platform for topological quantum computation using semiconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 040502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosur, P.; Ghaemi, P.; Mong, R.S.K.; Vishwanath, A. Majorana modes at the ends of superconductor vortices in doped topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 097001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.F.; Kong, L.Y.; Fan, P.; et al. Evidence for Majorana bound states in an iron-based superconductor. Science 2018, 362, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das Sarma, S.; Freedman, M.; Nayak, C. Topologically protected qubits from a possible non-Abelian fractional quantum Hall state. Phys. Rev. Lett., 2005, 94, 166802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.T.; Wan, C.Y.; Yang, H. et al. Signatures of hybridization of multiple Majorana zero modes in a vortex. Nature 2024, 633, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitiekenas, S.; Winkler, G.W.; van Heck, B. et al. Flux-induced topological superconductivity in full-shell nanowires. Science 2020, 367, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.H.; Chen, L.; Liu, D.E.; Zhang, F.C.; Liu, X. Majorana Zero Modes Induced by the Meissner Effect at Small Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 036602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, D.; Bouman, D.; van Woerkom, D.J. et al. Observation of the 4π-periodic Josephson effect in indium arsenide nanowires. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.L.; Pan, L.; Stern, A.L. et al. Chiral Majorana fermion modes in a quantum anomalous Hall insulator-superconductor structure. Science 2017, 357, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; Lee, M.; Serra, L.; Lim, J. Thermoelectrical detection of majorana states. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 205418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Fu, Z.G.; Liu, J.; Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P. Thermoelectric effect in a quantum dot side-coupled to majorana bound states. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Chi, F.; Fu, Z.G.; Hou, Y.F.; Wang, Z. Large enhancement of thermoelectric effect by majorana bound states coupled to a quantum dot. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 124302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Liu, J.; Fu, Z.G. Yi, Z.C.; Liu, L.M. onlinear Seebeck and Peltier effects in a Majorana nanowire coupled to leads. Chin. Phys. B. 2024, 33, 077301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klees, R.L.; Gresta, D.; Sturm, J.; Molenkamp, L.W.; Hankiewicz, E.M. Majorana-mediated thermoelectric transport in multiterminal junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 064517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Zhu, K.D. All-optical scheme for detecting the possible Majorana signature based on QD and nanomechanical resonator systems, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2015, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.Z. , Zhang, Y.T. and Liu, J.J. Photon-assisted tunneling through a topological superconductor with majorana bound states. AIP Advances 2015, 5, 127129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; He, T.Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, Z.G.; Liu, L.M.; Liu, P.; Zhang, P. Photon-assisted transport through a quantum Dot side-coupled to majorana bound states. Frontiers in Physics 2020, 8, 00254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; He, T.Y.; Zhou, G.F. Photon-Assisted Average Current Through a Quantum Dot Coupled to Majorana Bound States. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytruk, O.; Trif, M. Microwave detection of gliding Majorana zero modes in nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.N.; Das Sarma, S. Physical mechanisms for zero-bias conductance peaks in Majorana nanowires. Phys. Rev. Research 2020, 2, 013377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wiel, W.G.; Franceschi, S.D. Elzerman, J.M.; Fujisawa, T.; Tarucha, S.; Kouwenhoven, L.P. Electron transport through double quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.E.; Baranger, H.U. Detecting a majorana-fermion zero mode using a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 201308R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.T.; Vaitiekenas, S.; Hansen, E.B. et al. Majorana bound state in a coupled quantum-dot hybrid-nanowire system. Science 2016, 354, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das Sarma, S. In search of Majorana. Nat. Phys. 2023, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; von Oppen, F.; Halperin, B.I.; Yacoby, A. Hunting for Majoranas. Science 2023, 380, 0850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, E.; Aguado, R.; San-Jose, P. Measuring Majorana nonlocality and spin structure with a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 085418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.J.; Wang, J.R.; Mao, H.; Jin, J.S. Distinguishing Majorana bound states from Andreev bound states through differential conductance and current noise spectrum. 20 February; 27.

- Gong, W.J.; Zhang, S.F.; Li, Z.C.; Yi, G.Y.; Zheng, Y.S. Detection of a Majorana-fermion zero mode by a T-shaped quantum-dot structure. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 245413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, T.I. Coherent tunneling through a double quantum dot coupled to Majorana bound states. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 035417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majek, P.; Gorski, G.; Domanski, T.; Weymann, I. Hallmarks of Majorana mode leaking into a hybrid double quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 155123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, S.V. Probing Majorana bound states through an inhomogeneous Andreev double dot interferometer. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 085417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, D.M.; Souto, R.S.; Aguado, R. Minimal Kitaev-transmon qubit based on double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 075101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, B.; Lee, S.Y. Two-dimensional materials based on negative differential transconductance and negative differential resistance for the application of multi valued logic circuit: a review. Carbon Letters 2023, 33, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, J. Theory of current-voltage asymmetries in double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 201304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Li, S.S. Current voltage characteristics in strongly correlated double quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 123704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, M.L.; Frisenda, R.; Koole, M. et al. Large negative differential conductance in single-molecule break junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Astier, H.P.A.G. et al. Dynamic molecular switches with hysteretic negative differential conductance emulating synaptic behaviour. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.G. et al. Charge transfer mechanism for realization of double negative differential transconductance. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2024, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H.; Guo, H.W.; Wang, H.Y.; Wei, Z.J.; Liang, X.H. Controllable antiresonance and low-bias negative differential conductance in T-shaped double dots with electron-phonon interaction. Physica E: Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2024, 163, 116014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.G.; Sun, Q.F. Josephson current transport through T-shaped double quantum dots. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 505202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathe, M.; Sticlet, D.; Zarbo, L.P. Quantum transport through a quantum dot side-coupled to a Majorana bound state pair in the presence of electron-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 155409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.M.; Shen, Y.H.; Chi, F.; Yi, Z.C.; Liu, L.M. Quantum Transport through a Quantum Dot Coupled to Majorana Nanowire and Two Ferromagnets with Noncollinear Magnetizations. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, B.; Verma, S.; Ajay. Josephson and thermophase effect in interacting T-shaped double quantum dots system. Physica E: Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2025, 66, 116142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, A.M.; Pacheco, M.; Martins, et al. Fano-Andreev effect in a T-shape double quantum dot in the Kondo regime. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 135301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).