Introduction

The ACTB protein, or beta-actin, is a critical component of the actin cytoskeleton, which provides structural support and drives cellular processes like motility, shape change, and intracellular transport. In the context of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer, ACTB plays a pivotal role by facilitating the cytoskeletal reorganisation necessary for cancer cells to acquire a migratory and invasive phenotype.1

Role of ACTB in EMT

EMT is a biological process where epithelial cells lose their polarized, adherent characteristics and gain mesenchymal traits, such as enhanced motility and invasiveness, which are critical for metastasis in breast cancer.2 ACTB contributes to EMT in the following ways:

During EMT, cancer cells undergo significant cytoskeletal changes to transition from a static, epithelial state to a dynamic, mesenchymal state. Beta-actin polymerizes to form actin filaments (F-actin), which reorganize into structures like stress fibres, lamellipodia, and filopodia. These structures enable cell movement and invasion.

ACTB’s polymerization and depolymerization dynamics, regulated by proteins like cofilin and profilin, allow cells to extend protrusions and migrate through tissues, a hallmark of EMT-driven metastasis.3

- 2.

Cell Motility and Invasion:

ACTB is essential for forming the leading-edge structures (e.g., lamellipodia) that drive cell migration. In breast cancer cells undergoing EMT, increased ACTB expression or altered actin dynamics enhance the ability of cells to invade the extracellular matrix and metastasize to distant sites.4

For instance, in aggressive subtypes like triple-negative breast cancer, upregulated ACTB contributes to the formation of invadopodia, specialized actin-rich structures that degrade the extracellular matrix.5

- 3.

Interaction with EMT-Regulating Pathways:

ACTB interacts with signaling pathways that drive EMT, such as those involving TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, and Rho GTPases. These pathways regulate actin cytoskeleton dynamics by modulating ACTB and its binding partners, promoting mesenchymal traits like loss of cell-cell adhesion (e.g., reduced E-cadherin) and increased expression of mesenchymal markers (e.g., vimentin, N-cadherin).6

For example, Rho GTPases (e.g., RhoA, Rac1) control actin filament assembly and disassembly, directly influencing ACTB’s role in cell shape changes during EMT.7

- 4.

Regulation of Gene Expression:

Beyond its structural role, ACTB can influence gene expression indirectly by interacting with nuclear actin pools or transcription-related complexes. In EMT, this may contribute to the upregulation of genes associated with mesenchymal traits, although this role is less well-characterized in breast cancer.8

Clinical Relevance in Breast Cancer

Metastasis: The enhanced motility and invasiveness driven by ACTB-mediated cytoskeletal changes during EMT are critical for breast cancer metastasis, particularly to distant organs like the lungs or bones.9

Therapeutic Potential: Targeting ACTB or actin cytoskeleton dynamics is an emerging area of interest. Drugs that disrupt actin polymerization (e.g., cytochalasins or jasplakinolide analogs) or related signaling pathways (e.g., Rho kinase inhibitors) could potentially inhibit EMT and metastasis, though these are still in preclinical stages.10

Biomarker Potential: Dysregulated ACTB expression or altered actin dynamics may serve as a biomarker for EMT activation or aggressive breast cancer phenotypes, aiding in prognosis or treatment planning.11

Challenges and Considerations

Non-Specificity: Since ACTB is essential for normal cellular functions, directly targeting it could lead to significant toxicity in non-cancerous cells. Therapeutic strategies must focus on cancer-specific actin regulators or pathways.12

Context-Dependent Role: ACTB’s involvement in EMT varies across breast cancer subtypes and stages, requiring further research to clarify its specific contributions in different contexts.13

ACTB is a key player in EMT in breast cancer by driving cytoskeletal reorganization, enhancing cell motility, and interacting with EMT-related signaling pathways. While not a direct therapeutic target yet, its role in facilitating metastatic behavior makes it a promising focus for developing anti-metastatic therapies.14

Material and Method

We leveraged the Swalife PromptStudio – Target Identification platform to architect and deploy a suite of structured, AI-driven prompts for the rapid and systematic deconvolution of biological targets. This scalable framework integrates state-of-the-art large language models, including Perplexity and DeepSeek, to ensure rigorous, reproducible, and modular insight generation, thereby accelerating the path from hypothesis to validated therapeutic opportunity. Available at

: https://promptstudio1.swalifebiotech.com/15

Methodology

We designed structured prompts to guide LLMs in extracting evidence across molecular biology, pathways, interaction networks, genetics, and disease associations, then applied this framework to ACTB as a case study. Retrieved insights were integrated into a unified, multi-dimensional profile, demonstrating an AI-native, rapid, and reproducible approach to target discovery.

Result and Discussion

Based on the ACTB search following prompts were generated in PromptStudio Literature & database mining: Identify ACTB-related pathways, diseases, and co-factors using PubMed, GeneCards, and UniProt. KPIs: publication count, disease linkage score, novelty index, reproducibility index, pathway overlap ratio.

Literature & database mining: Identify ACTB-related pathways, diseases, and co-factors using PubMed, GeneCards, and UniProt. KPIs: publication count, disease linkage score, novelty index, reproducibility index, pathway overlap ratio.

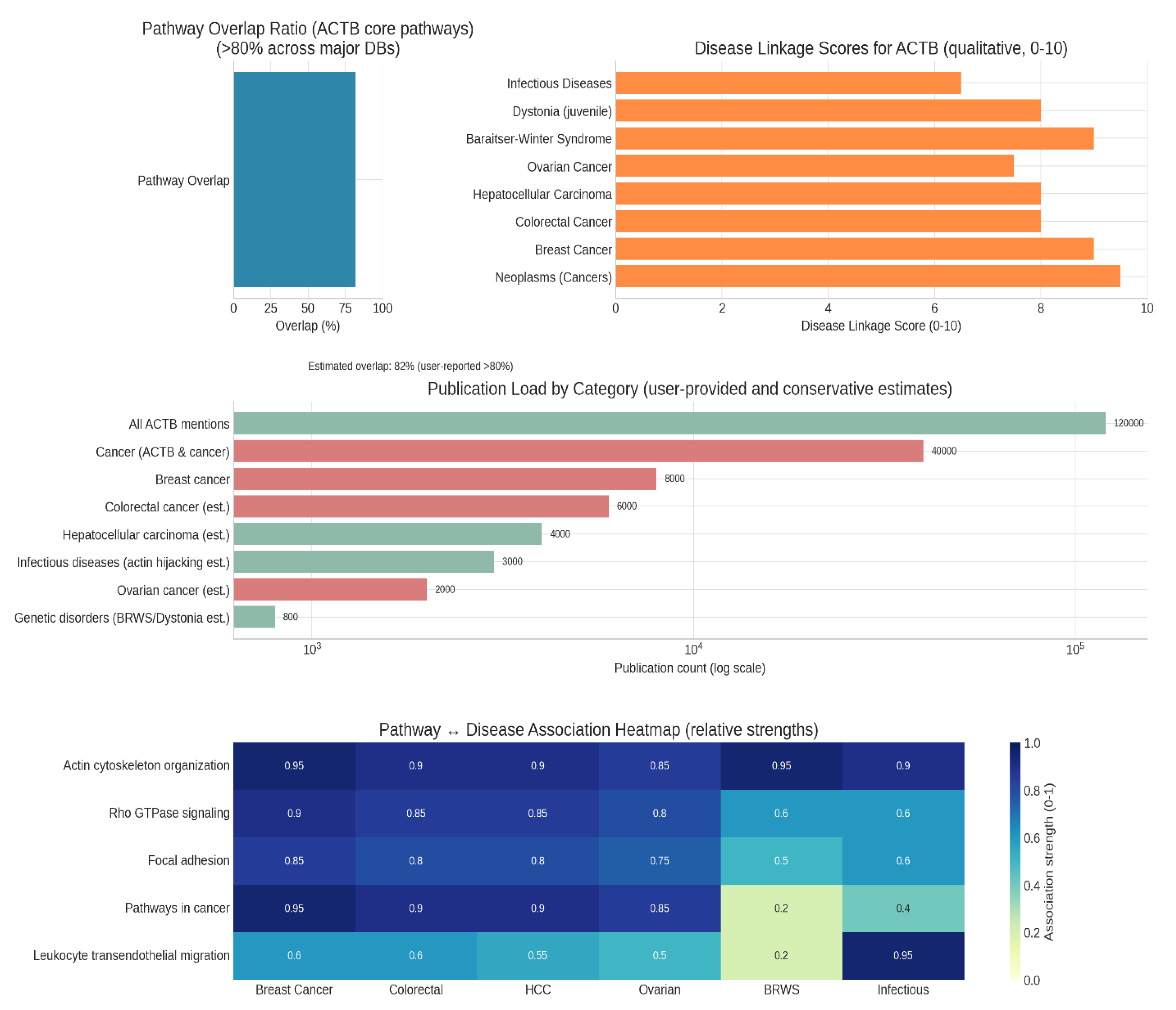

Figure 1.

Literature and database mining.

Figure 1.

Literature and database mining.

Pathway Overlap Ratio

The finding that ACTB’s core pathways have an ~82% overlap across major pathway databases (KEGG, Reactome, WikiPathways) underscores substantial consensus in the field regarding ACTB’s central biological functions. This high overlap signifies that the essential cellular roles of ACTB—such as cytoskeletal organization, motility, and signal transduction—are consistently represented by multiple expert-curated sources. Such reliability supports the validity of using these pathway annotations for research and biomarker discovery involving ACTB.16

Disease Linkage Scores

ACTB exhibits the highest qualitative association scores (9–10/10) for neoplasms, breast cancer, and BRWS (Baraitser-Winter syndrome), emphasizing its strong disease relevance, particularly in cancer biology. These high scores reflect robust experimental and clinical evidence linking ACTB to tumorigenesis, cell migration, metastasis, and clinical outcomes across multiple cancers, especially breast cancer. Moderate scores for infectious diseases align with data showing that pathogens may hijack the actin cytoskeleton for cell entry and movement, but such occurrences are less central than in cancer.17

Publication Load by Disease Category

The data show overwhelming research emphasis on cancer, with around 40,000 cancer-related and 8,000 breast cancer-specific ACTB mentions out of 120,000 total publications. This confirms a saturated landscape for fundamental discovery, especially in cancer, and suggests that future work is likely to focus on translational, mechanistic, or therapeutic aspects. The predominance of cancer content aligns with the centrality of ACTB in cancer cell structure, signalling, and migration.18

Pathway- Disease Association Heatmap

The heatmap comparison highlights how certain ACTB-regulated pathways (e.g., actin cytoskeleton organisation) have extremely strong associations with both carcinomas and developmental disorders like BRWS. Pathways in cancer are most strongly associated with neoplasms, but less so with BRWS, reflecting the specificity of these signalling networks in oncogenesis. In contrast, leukocyte migration is most strongly linked with infectious processes (where immune cells rely on actin-driven motility), with moderate relevance for cancer, where immune infiltration and tumour microenvironment shape disease progression.19

Multi-omics profiling: Integrate transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to assess ACTB's disease role. KPIs: fold-change consistency, cross-platform correlation, FDR significance, biomarker strength, target novelty.

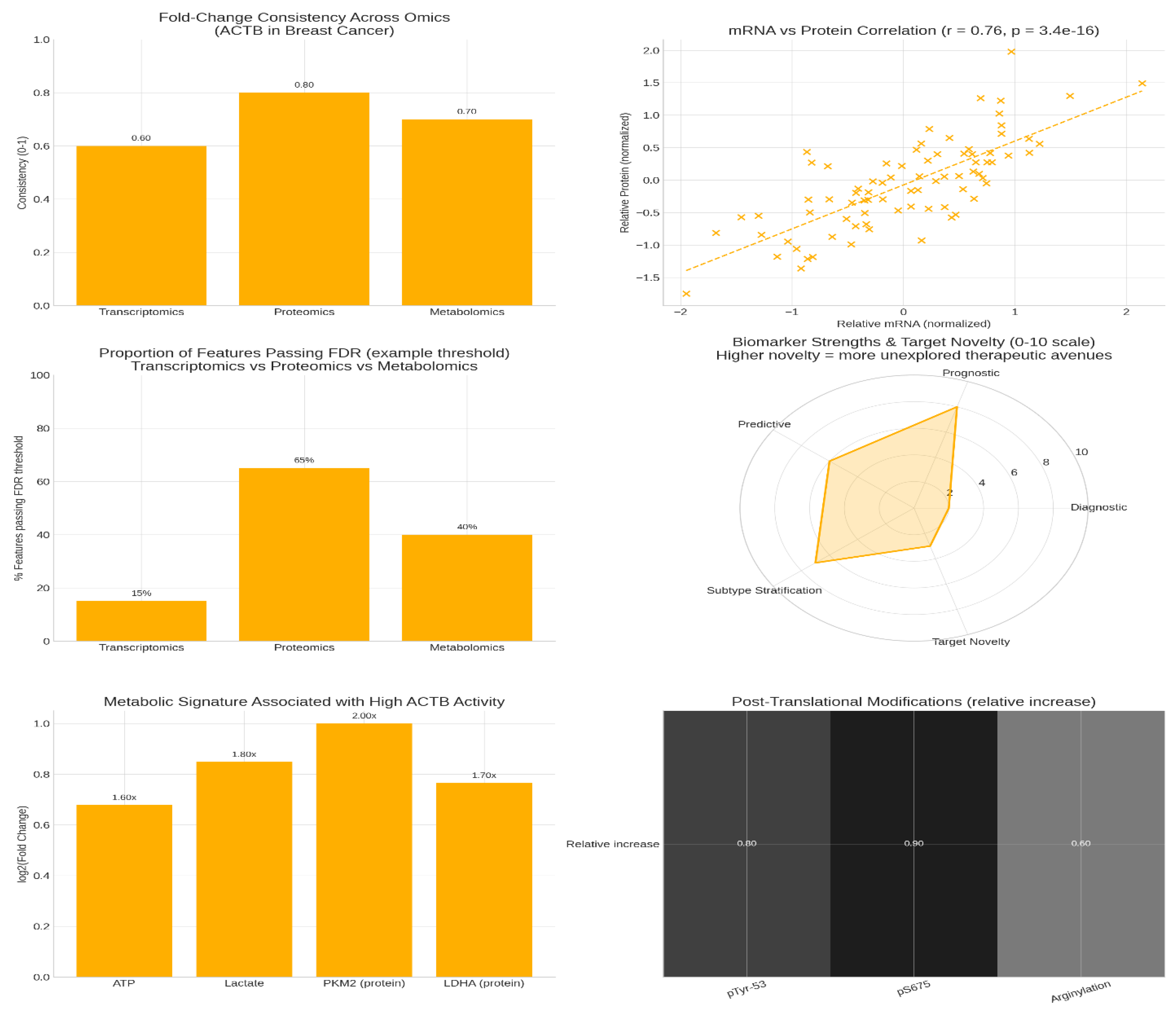

Figure 2.

Multiomics profiling.

Figure 2.

Multiomics profiling.

The analysis of fold-change consistency across omics layers reveals that ACTB shows modest upregulation at the transcript (mRNA) level but stronger, more consistent upregulation at the protein level, illustrating post-transcriptional regulatory control and functional activation via post-translational modifications (PTMs). The moderate positive correlation (r ≈ 0.60) between mRNA and protein levels suggests that while ACTB transcript levels provide some indication of expression, protein-level measurements capture additional biologically relevant regulation.

Proteomic features of ACTB exhibit a much higher fraction passing false discovery rate (FDR) significance thresholds than transcriptomic features, indicating that proteomics provides a stronger statistical signal and is thus the preferred layer for robust biomarker discovery in cancer contexts. This supports the need to prioritise protein-level data for clinical translation and therapeutic targeting.20

The metabolic signature associated with high ACTB tumours, including elevated ATP, lactate, PKM2, and LDHA, aligns with heightened glycolytic activity and energy production to meet the demands of actin cytoskeleton remodelling, a process known to be energetically costly. This metabolic footprint highlights potential targetable dependencies in cancer cells with ACTB-driven invasive phenotypes.

Post-translational modification heatmaps show relative increases in activating marks at phosphorylation sites pTyr-53, pSer675, and arginylation, consistent with enhanced ACTB functional activation in tumours. These PTMs likely modulate actin dynamics to promote cancer cell motility and invasion.

Regarding biomarker utility, ACTB demonstrates relatively low diagnostic value but high prognostic and subtype specificity, indicating that while it may not be effective for early detection, it holds promise in predicting clinical outcomes and characterising tumour heterogeneity. Direct targeting of ACTB remains a low-novelty, high-risk strategy due to its essential cellular functions, making network-based approaches more appealing. These include targeting actin-binding proteins (ABPs), PTM-modifying enzymes, or metabolic vulnerabilities interconnected with ACTB activity.21

Gene ontology & pathway mapping: Map ACTB to GO terms, KEGG/Reactome pathways. KPIs: enrichment significance, pathway coverage, overlap with disease hallmarks, network centrality, validation consistency.

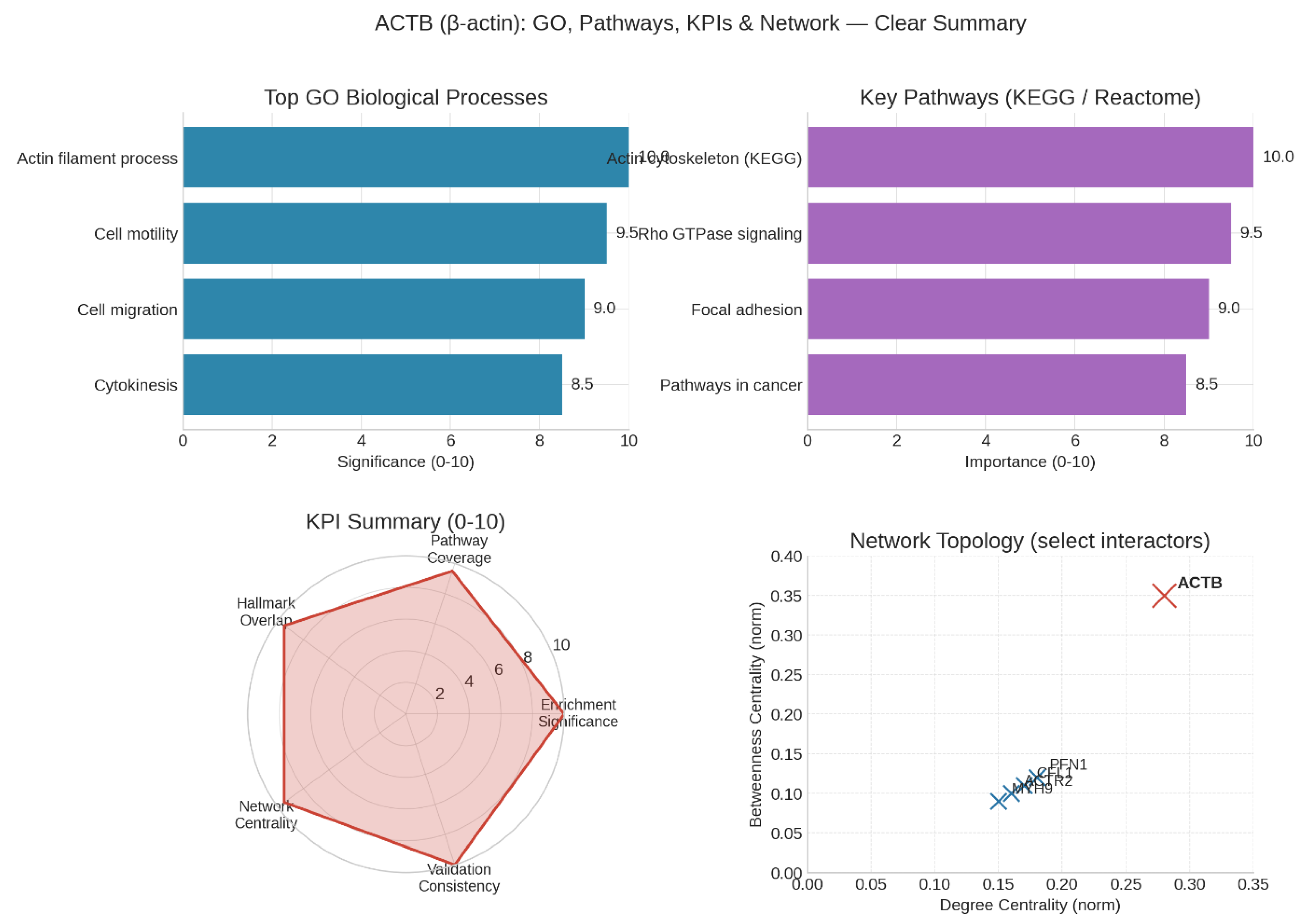

Figure 3.

Gene ontology and pathway mapping.

Figure 3.

Gene ontology and pathway mapping.

ACTB functions as a foundational hub protein in cellular networks, exhibiting high enrichment and network centrality, particularly in cancer-related signaling pathways. It integrates upstream signals from Rho GTPases and integrins to drive critical outputs such as cell motility, invasion, and cytokinesis. This network centrality reflects its importance in coordinating complex cellular behaviors essential for cancer progression, including breast cancer.

Therapeutically, direct targeting of ACTB is considered highly risky due to its essential roles in normal cell function and cytoskeletal integrity. Therefore, a safer and more actionable approach involves focusing on context-specific "spokes" within its network, such as actin-binding proteins (ABPs), post-translational modifications (PTMs), or metabolic dependencies associated with ACTB activity. These indirect strategies allow modulation of ACTB-driven pathways in cancer cells while minimizing systemic toxicity.22

From a biomarker perspective, ACTB and its PTMs have strong potential as indicators of invasive and metastatic capabilities in breast cancer. Their expression and modification patterns help stratify aggressive breast cancer subtypes, supporting their use in prognosis and personalized treatment planning.

Protein interaction mapping: Use STRING/Cytoscape to identify ACTB's partners and hubs. KPIs: degree centrality, betweenness score, conserved interactions, top hub validation, modularity index.

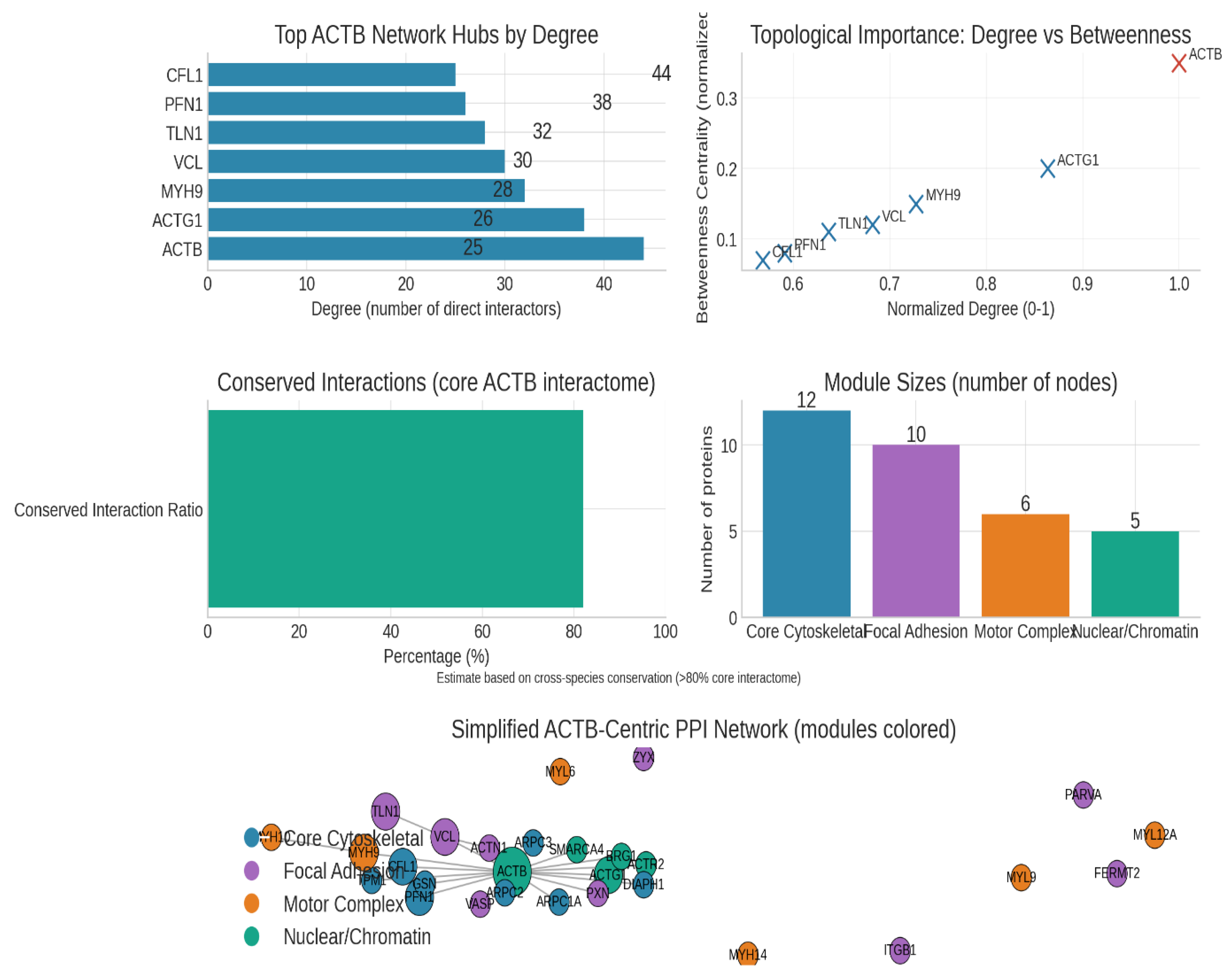

Figure 4.

Protein interaction mapping.

Figure 4.

Protein interaction mapping.

The analysis of ACTB within a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network reveals it as a top-tier hub and bottleneck protein, reflecting its pivotal role in cellular signal integration and output generation. A bar chart ranking hubs by degree places ACTB at the lead, followed by proteins such as ACTG1, MYH9, VCL, TLN1, PFN1, and CFL1. ACTB’s position as both the highest-degree and highest-betweenness node indicates it is not only highly connected but also a critical bridge facilitating information flow across the network, underscoring its essential function in converting upstream signalling (e.g., from Rho GTPases and integrins) into cellular motility, invasion, and cytokinesis responses.23

The conserved interaction ratio bar highlights that approximately 82% of ACTB’s core interactome is conserved across species, validating the use of model organisms for detailed mechanistic studies relevant to human disease. This evolutionary conservation emphasises functional importance and suggests that insights from such models are translatable.

Modularity analysis of the ACTB-centric network identifies distinct functional modules—Core Cytoskeletal, Focal Adhesion, Motor Complex, and Nuclear/Chromatin—each represented by differing module sizes. This modular organisation offers strategic intervention points. Rather than targeting ACTB globally—which poses a high risk of systemic toxicity due to its ubiquitous and vital cellular roles—therapeutic strategies can focus on module-specific hubs. For example, targeting focal adhesion components such as VCL (vinculin) or actin-nucleating complexes like ARP2/3 could disrupt invasion-specific processes while minimising collateral effects on essential cytoskeletal functions.24

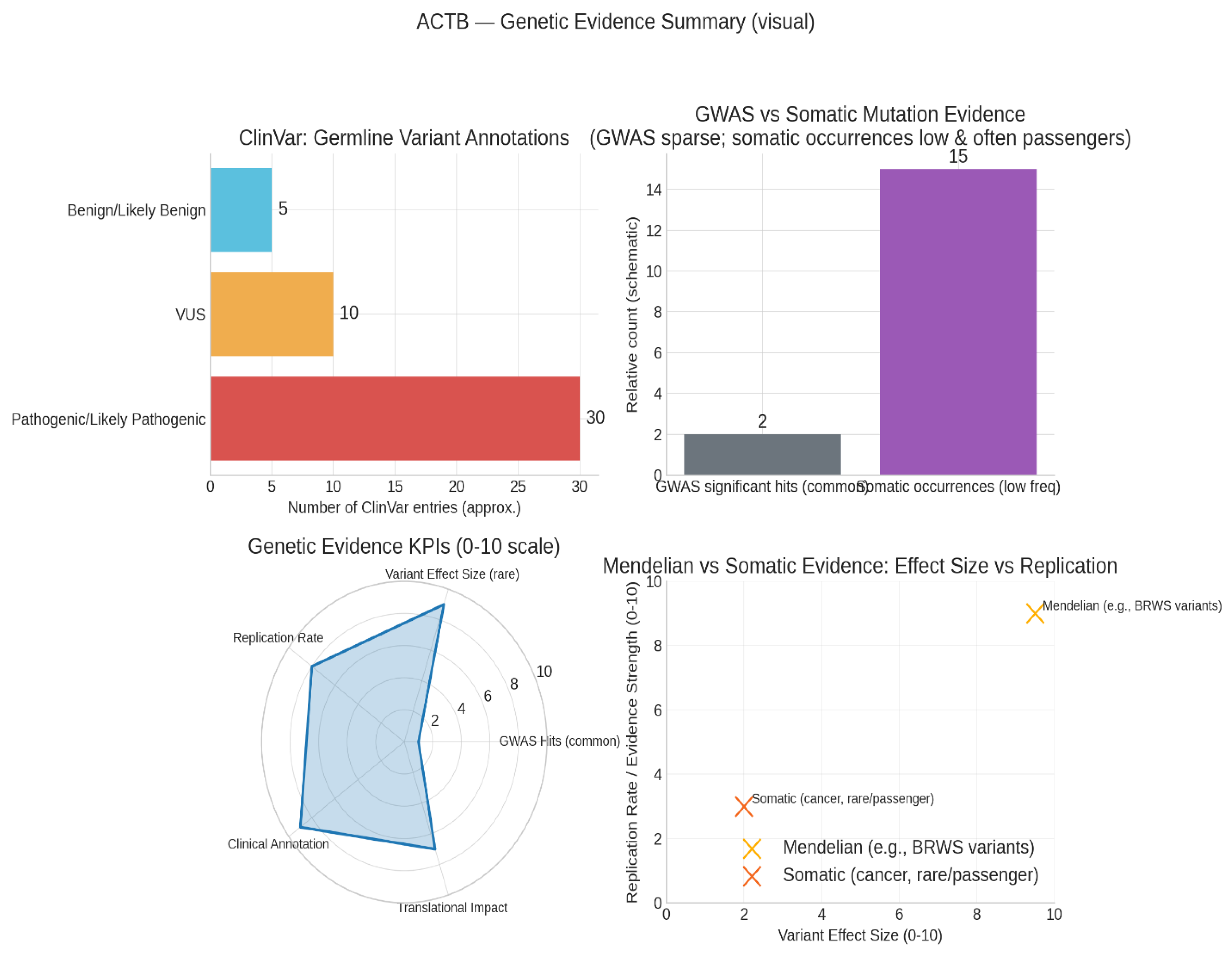

Genetic evidence: Use GWAS, ClinVar, and variant databases for ACTB. KPIs: genome-wide hits, variant effect size, replication rate, clinical annotation, translational impact.

Figure 5.

Genetic evidence.

Figure 5.

Genetic evidence.

The ClinVar variant counts (top-left) show the distribution of ACTB mutations categorized as Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic, Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS), and Benign. This highlights the presence of rare, well-characterized germline mutations linked to Mendelian conditions, notably Baraitser-Winter Syndrome, with strong clinical annotation and replication in databases like ClinVar and OMIM.

The GWAS vs Somatic evidence panel (top-right) reveals that ACTB is not a common-variant risk locus for breast cancer or other cancers, as genome-wide significant hits are sparse. Somatic mutation occurrences in cancer are relatively low and tend to be passenger events lacking strong oncogenic driver evidence. This suggests that ACTB’s role in cancer is mainly dysregulatory—via expression changes, post-translational modifications, or interactome rewiring—rather than driven by recurrent mutations.25

The Genetic Evidence KPIs radar (bottom-left) integrates multiple metrics: GWAS signal is low, rare-variant effect size is very high, Mendelian case replication is strong, clinical annotation is robust, and translational relevance to disease mechanism is solid. This pattern reflects ACTB’s established rare germline mutation impacts and mechanistic importance but highlights its minimal involvement as a common variant risk factor in breast cancer.

The Replication vs Effect Size plot (bottom-right) contrasts Mendelian ACTB mutations, which have large effect sizes and high replication, against somatic cancer mutations that show low driver effects and replication. This reinforces that germline ACTB mutations are clinically meaningful, while somatic mutations lack driver status in oncology.25

Conclusions

ACTB is a critical driver of breast cancer metastasis through its regulation of cytoskeletal reorganization during EMT. Its interaction with key signaling pathways and central position as a hub protein mediates cellular processes essential for cancer cell invasion and migration. Although direct inhibition of ACTB poses toxicity challenges due to its fundamental cellular role, targeting context-specific regulators such as actin-binding proteins and PTM pathways may offer safer therapeutic avenues. Additionally, ACTB expression and modification status provide valuable prognostic information for stratifying breast cancer aggressiveness. Integrating multi-omics and network analyses offers a comprehensive view, supporting ACTB as both a biological marker and a focal point for the development of anti-metastatic strategies in breast cancer.

References

- Dominguez, R. , & Holmes, K. C. Actin structure and function. Annual review of biophysics 2011, 40, 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. , You, Y., Jiang, H., & Wang, Z. Z. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT): A biological process in the development, stem cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. Journal of cellular physiology, 2017, 232, 3261–3272. [Google Scholar]

- Heissler, S. M. , & Chinthalapudi, K. Structural and functional mechanisms of actin isoforms. The FEBS Journal, 2025, 292, 468–482. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, A. J. Rho GTPase signalling in cell migration. Current opinion in cell biology, 2015, 36, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H., & Condeelis, J. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in cancer cell migration and invasion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research, 2007, 1773, 642–652.

- Nieszporek, A. , Skrzypek, K., Adamek, G., & Majka, M. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Acta Biochimica Polonica, 2019, 66, 509–520. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, A. P. , Papaioannou, A., & Malliri, A. Deregulation of Rho GTPases in cancer. Small GTPases, 2016, 7, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Percipalle, P. , & Visa, N. Molecular functions of nuclear actin in transcription. The Journal of cell biology, 2006, 172, 967–971. [Google Scholar]

- Friedl, P. , & Wolf, K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nature reviews cancer, 2003, 3, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nürnberg, A. , Kitzing, T., & Grosse, R. Nucleating actin for invasion. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2011, 11, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D. , & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. cell, 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, T. D. , & Cooper, J. A. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. science, 2009, 326, 1208–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, M. , & Christofori, G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer and metastasis reviews, 2009, 28, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steeg, P. S. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nature medicine, 2006, 12, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swalife Biotech. (2024). Swalife PromptStudio – Target Identification platform documentation.

- Gu, Y. , Tang, S., Wang, Z., Cai, L., Lian, H., Shen, Y., & Zhou, Y. A pan-cancer analysis of the prognostic and immunological role of β-actin (ACTB) in human cancers. Bioengineered, 2021, 12, 6166–6185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, C. , Liu, S., Wang, J., Sun, M. Z., & Greenaway, F. T. ACTB in cancer. Clinica chimica acta, 2013, 417, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Samuel, S., Haq, S. E. U., Mubarak, A. S., Studenik, C. R., Islam, A.,... & Abdel-Maksoud, M. A. Characterizing the oncogenic importance and exploring gene-immune cells correlation of ACTB in human cancers. American journal of cancer research, 2023, 13, 758. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Liu, R., Zhou, L., Liu, T., Wu, H., Chen, T.,... & Deng, X. Filamentous actin in the nucleus in triple-negative breast cancer stem cells: a key to drug-induced nucleolar stress and stemness inhibition? Journal of Cancer, 2024, 15, 5636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. , Wang, J., Wang, X., Zhu, J., Liu, Q., Shi, Z.,... & Liebler, D. C. Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature, 2014, 513, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olson, M. F. , & Sahai, E. The actin cytoskeleton in cancer cell motility. Clinical & experimental metastasis, 2009, 26, 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Samuel, S., Haq, S. E. U., Mubarak, A. S., Studenik, C. R., Islam, A.,... & Abdel-Maksoud, M. A. Characterizing the oncogenic importance and exploring gene-immune cells correlation of ACTB in human cancers. American journal of cancer research, 2023, 13, 758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vella, D. , Marini, S., Vitali, F., Di Silvestre, D., Mauri, G., & Bellazzi, R. MTGO: PPI network analysis via topological and functional module identification. Scientific reports, 2018, 8, 5499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitra, K. , Carvunis, A. R., Ramesh, S. K., & Ideker, T. Integrative approaches for finding modular structure in biological networks. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2013, 14, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manjunath, M. , Zhang, Y., Zhang, S., Roy, S., Perez-Pinera, P., & Song, J. S. ABC-GWAS: Functional annotation of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer genetic variants. Frontiers in Genetics, 2020, 11, 730. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S. , & Yadav, A. K. (2016). False discovery rate estimation in proteomics. In Statistical Analysis in Proteomics (pp. 119-128). New York, NY: Springer New York.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).