Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

| Stage | Transition | Unit of Evolution | Feedback Medium |

| 0 | Pre-life chemistry | Molecular replicators | Chemical autocatalysis |

| 1 | Life emerges (protocells) | Metabolic gene networks | Environmental coupling |

| 2 | DNA + natural selection | Genes & genotypes | Reproductive fitness |

| 3 | Multicellularity | Cells and cell groups | Developmental programs |

| 4 | Nervous systems | Behaviors / neural circuits | Sensorimotor learning |

| 5 | Symbolic communication | Cognitive strategies | Language/memory feedback |

| 6 | Culture & institutions | Ideas / memes / cultures | Social interaction |

| 7 | Scientific civilization | Knowledge systems | Technological & symbolic |

| 8 | Post-human intelligence/ AI | Self-evolving intelligences | Recursive cybernetic loops |

| Stage | Trait ϕ | Fitness Function W | Feedback Type | Info Gain Medium |

| 1 | Membrane structure | Chemical stability + replication rate | Autocatalysis, environment | Molecular interactions |

| 2 | Genetic sequences | Reproductive fitness in given environment | Natural selection | DNA mutations |

| 3 | Cell adhesion, division | Organismal viability | Developmental signaling | Epigenetic programs |

| 4 | Neural patterns | Behavior success / survival | Neural feedback from actions | Synaptic plasticity |

| 5 | Mental models | Prediction accuracy / communication | Social feedback, language | Memory, culture |

| 6 | Institutions, norms | Collective survival / cohesion | Governance, media, economy | Cultural inheritance |

| 7 | Scientific theories | Predictive power, problem-solving | Peer review, data feedback | Symbolic language + tech |

| 8 | Code, algorithms | Performance + self-improvement | Real-time evaluation loops | Machine learning systems |

- 1)

- Transition from non-living microscopic particles to metabolically active, self-renewing protocells.

- 2)

- Transition from non-cellular living matter to single-celled organisms with defined cellular structures.

- 3)

- Evolution from unicellular to multicellular organisms with cellular differentiation.

Material and Method

Result and Discussion

- 1.

- Evolutionary Model Stage 1: From Abiotic Matter to Life-like Particles

- 2.

- Evolutionary Model Stage 2: From Proto-life to Single-cellular Life

| Symbol | Meaning |

| M(τ) | Membrane integrity factor — cumulative probability of true single-celled organisms Emergence of lipid-like membrane-bound, single-celled life (bacteria, cyanobacteria) |

| L(τ) | Life potential from earlier model-- assumed as input (amount of replicating proto-life) Formation of proto-life particles (e.g., self-replicating molecules) |

| R(τ) | Replication fidelity — higher fidelity enables stable genome maintenance |

| S(τ) | Selective pressure — advantage of stable cells under early Earth stress |

| ΔGm(τ) | Free energy for cellular organization (formation of cytoplasm, membranes, etc.) |

| T(τ) | Temperature over time |

| R | Gas constant |

- Stage 1: Prebiotic chemistry produced proto-life — organic molecules (amino acids, nucleotides), self-replicating RNA, autocatalytic networks, and protocells lacking stable membranes.

- Stage 2: Transition to true cells with lipid membranes, internal metabolism, and higher replication fidelity. Cell division and clustering under harsh conditions led to early multicellularity, initiating Stage 3: differentiation.

- 3

- Evolutionary Model Stage 3: From the Single-cellular Life to Multicellular Life

| Symbol | Name | Meaning | Why it matters |

| U(τ) | Multicellular Life Potential | Total probability that multicellular life has emerged by time t | Output of this model |

| M(τ) | Morphological Cell Potential | Availability of viable single-celled organisms (from previous layer) | Multicellular life can’t form without cells |

| Φ(τ) | Adhesion and Signaling Factor | Measures whether cells can stick together and communicate (e.g. proteins for binding, signaling molecules) | Essential for tissue formation and coordination |

| Λ(τ) | Metabolic Complementarity | Benefit from dividing metabolic roles among cells (e.g., some cells digest, others reproduce) | Drives cooperation and specialization |

| Ξ(τ) | Selective Pressure for Multicellularity | Evolutionary advantage of being multicellular (e.g., size for protection, division of labor) | Gives natural selection reason to favor multicellularity |

| e−ΔGu(τ)/RT(τ) | Energetic Feasibility | Thermodynamic likelihood of supporting multicellular structures | High energy costs make it harder to stay multicellularity |

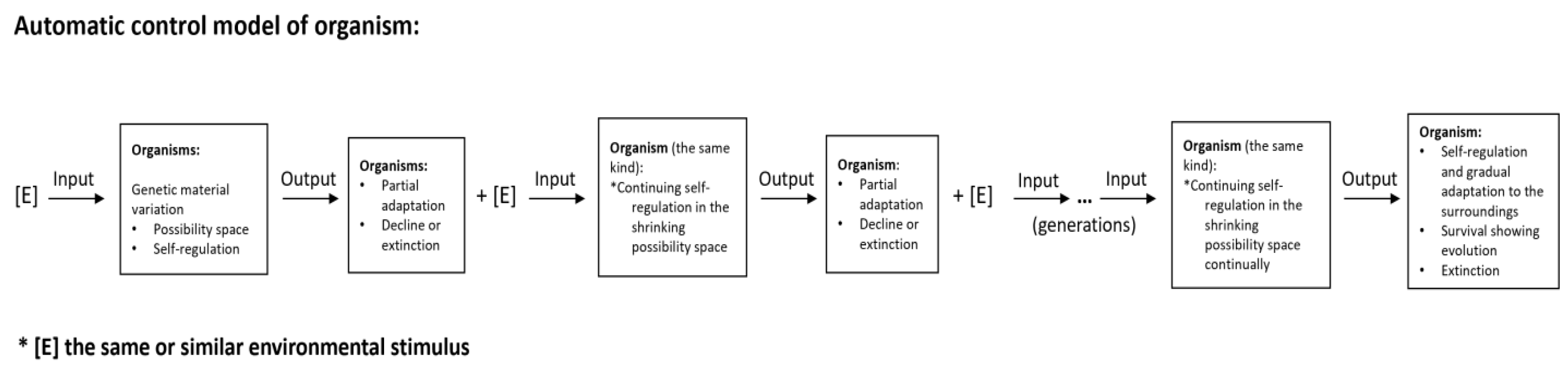

where C(t) is structural control, r(t) is regulatory responsiveness, and ωc, ωr are their weights.

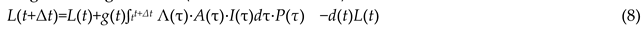

where C(t) is structural control, r(t) is regulatory responsiveness, and ωc, ωr are their weights.- L(t): cumulative structural/functional complexity.

- Λ(t): real-time adaptive control.

- 1)

- SL(t) grows when environmental demand (EL−SL) drives adaptation, constrained by energy (ΔG) and complexity(Cdiff).

- 2)

- 2) Specialization (Cdiff) increases efficiency but reduces adaptability via h(·).

- 3)

- Decay term −d(t)SL(t) reflects entropy and irreversibility.

- Φ(τ) = available free-energy throughput (power input) to the subsystem (Js −1 or similar),

- φ(τ) = local entropy-production rate (e.g. J K−1 s−1),

- κ = coupling constant (dimensionless) controlling how strongly dissipative structuring amplifies growth,

- Ψ(Φ,σ) = structural amplification function (dimensionless), and

- Sds(σ) = a sigmoid gating function (0..1) that turns on dissipative-structure enhancement only when entropy production crosses a window appropriate for self-organization

- 1)

- Low asymmetry/integration → flat Lcyb(t), representing stagnant evolution;

- 2)

- Strong cybernetic control with rising integration → accelerated growth in Lcyb, crossing thresholds (e.g., Lcyb>2.0) for the emergence of dinoflagellate-grade complexity, consistent with fossil and geobiological records.

- 3)

- 3) Environmental noise → delayed or destabilized transitions.

- σ(τ): local entropy-production rate (e.g., J K−1 s−1 or nondimensionalized).

- Ξ(Φint,σ,T): dissipative-structure coupling factor (dimensionless), modulating growth by thermodynamic favorability of maintaining low-entropy organization.

- deff(t): effective decay/loss rate, potentially dependent on entropy-production and energy availability (so disorder can increase loss).

- ι(τ): external driver (raw input --environmental throughput of energy, matter, or information: ι = 0 → no growth, ι is large → potential for growth).

Concluson

Conflicts of Interest

Author contributions statement

Declaration of funding

References

- Abigail C, Allwood MR, Walter BS, Kamber CP, Marshall, Burch IW (2006). Stromatolite reef from the Early Archaean era of Australia. Nature 441: 714–717.

- Abramov O, Mojzsis SJ (2009). Microbial habitability of the Hadean Earth during the late heavy bombardment. Nature 459 (7245):419-422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08015.

- Allwood AC, GrotzingerJP, Knoll AH, Burch IW, Anderson MS, Coleman ML, I (2009). Controls on development and diversity of Early Archean stromatolites. PNAS 106(24): 9548–9555.

- Anbar AD, Knoll AH (2002). Proterozoic ocean chemistry and evolution: A bioinorganic bridge? Science 297(5584), 1137–1142. [CrossRef]

- Badcock PB, Friston KJ, Ramstead MJD (2022). Applying the Free Energy Principle to Complex Adaptive Systems. Entropy 24(5):689. [CrossRef]

- Bamforth EL, Narbonne GM (2009) New Ediacaran rangeomorphs from Mistaken Point, Newfoundland, Canada. Journal of Paleontology 83 (6):897-913. [CrossRef]

- Becker S, Feldmann J, Wiedemann S, Okamura H, Schneider C, Iwan K, Crisp A, Rossa M, Amatov T, Carell T(2019). Unified prebiotically plausible synthesis of pyrimidine and purine RNA ribonucleotides. Science 366(6461):76–82. [CrossRef]

- Bell EA, Boehnke P, Harrison TM, Mao WL (2015). Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon. PNAS 112 (47): 14518–14521. [CrossRef]

- Bengtson S, Sallstedt T, Belivanova, V, Whitehouse M (2017). Three-dimensional preservation of cellular and subcellular structures suggests 1.6 billion-year-old crown-group red algae. PLoS Biology 15(3): e2000735. [CrossRef]

- Bontognali TRR, Sessions AL, Allwood AC, Fischer WW, Grotzinger JP, Summons RE, Eiler JM (2012). Sulfur isotopes of organic matter preserved in 3.45-billion-year-old stromatolites reveal microbial metabolism. PNAS 109(38): 15146–15151. [CrossRef]

- Brooks DR, Wiley EO (1986). Evolution as Entropy: Toward a Unified Theory of Biology. University of Chicago Press.

- Butterfield NJ (2000) Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n.sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity and the Mesoproterozoic–Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology 26 (3): 386–404.

- Canfield DE, Poulton SW, Narbonne GM (2007). Late-Neoproterozoic deep-ocean oxygenation and the rise of animal life. Science 315 (5808):92-95. [CrossRef]

- Capra F (2014). The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision (co-authored with Pier Luigi Luisi) Cambridge University Press.

- Crowe SA, Døssing LN, Beukes NJ, Bau M, Kruger SJ (2013). Atmospheric oxygenation three billion years ago. Nature 501(7468): 535-538. [CrossRef]

- de Mendoza A, Sebé-Pedrós A, Šestak MS, Matejčić M, Torruella G, Domazet-Lošo, T, Ruiz-Trillo I (2013). Transcription factor evolution in eukaryotes and the assembly of the regulatory toolkit in multicellular lineages. PNAS 110(50):e4858–4866. [CrossRef]

- Deacon TW (2011). Incomplete nature: how mind emerged from matter. W.W. Norton.

- Despons A (2025). Nonequilibrium properties of autocatalytic networks.Physical Review E 111: 014414. [CrossRef]

- El Albani A, Stefan Bengtson S, Meunier A (2010). Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago. Nature 466(7302): 100-104. [CrossRef]

- Eigen M, Schuster P (1977). The hypercycle: A principle of natural self-organization. Part A: Emergence of the hypercycle. Die Naturwissenschaften 64(11): 541–565.

- Eigen M, Schuster P (1979). The Hypercycle: A Principle of Natural Self-Organization. Springer-Verlag. (Book; Springer).

- Farquhar J, Bao H, Thiemens MH (2000). Atmospheric influence of Earth’s earliest sulfur cycle. Science 289(5480): 756-758. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi K, Naraoka H, Ohmoto H (2008). Oxygen isotope study of Paleoproterozoic banded iron formation, Hamersley Basin, Western Australia. Resource Geology 58 (1): 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Fensome RA, MacRae RA, Moldowan JM, Taylor FJR, Williams GL (2016).The early Mesozoic radiation of dinoflagellates. Paleobiology 22(3):329–338. [CrossRef]

- Ferris JP (1984). The chemistry of life's origin. Chem Eng News 62:22-35.

- Fields C (2024). The free energy principle induces intracellular compartmentalization. Biochemical and biophysical research communicatios 723:150070. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R. A. (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press (Oxford).

- Gibson TM, Shih PM, Cumming VM, Fischer WW, Crockford PW, Hodgskiss MSW, … Rainbird RH (2018). Precise age of Bangiomorpha pubescens dates the origin of eukaryotic photosynthesis. Geology 46(2):135–138. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert W (1986). Origin of life: The RNA world. Nature, 319: 618. [CrossRef]

- Gözen I (2022). Protocells: Milestones and Recent Advances. Small 18(16): e2106624 Hagan MF, Baskaran A (2016). Emergent Self-organization in Active Materials. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 38:74–80. [CrossRef]

- Han TM, Runnegar B (1992). Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1 billion-year-old Negaunee Iron-Formation, Michigan. Science 257 (5067):232-235.

- Hansma HG (2010). Possible origin of life between mica sheets. Journal of Theoretical Biology 266(1): 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Hansma HG (2014). The power of crowding for the origins of Life. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres 44: 307–311. [CrossRef]

- Hansma HG (2017). Better than Membranes at the Origin of Life? Life 7(2): 28. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi K, Naraoka H, Ohmoto H (2008). Oxygen isotope study of Paleoproterozoic banded iron formation, Hamersley Basin, Western Australia. Resource Geology 58 (1):43-51. [CrossRef]

- Heylighen F, Joslyn C (2001). Cybernetics and Second-Order Cybernetics In: Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology (3rd ed.), Vol. 4: 155–170. Academic Press.

- Hodgskiss MSW, Crockford PW, Turchyn AV (2023). Deconstructing the lomagundi–jatuli carbon isotope excursion. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 51:301-330. [CrossRef]

- Hordijk W (2013). Autocatalytic sets: from the origin of life to the economy. BioScience 63(11):877-881.

- Huson D, Xavier JC, Steel M (2024). Self-generating autocatalytic networks: structural results, algorithms and their relevance to early biochemistry. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 21(214):20230732. [CrossRef]

- Huson DH., Xavier JC, Steel MA (2024). CatReNet: interactive analysis of (auto-)catalytic reaction networks. Bioinformatics 40(8), btae515. [CrossRef]

- Javaux EJ, Lepot K (2017). The Paleoproterozoic fossil record: Implications for the evolution of the biosphere during Earth’s middle-age. Earth-Science Reviews 176:68–86. [CrossRef]

- Jenewein C, Maíz-Sicilia A, Rull F, González-Souto L, García-Ruiz JM (2024). Concomitant formation of protocells and prebiotic compounds under a plausible early Earth atmosphere. PNAS 122(2): e2413816122. [CrossRef]

- Jia TZ, Chandru K, Hongo Y, Afrin R, Usui T, Myojo K, Cleaves II HJ (2019). Membraneless polyester microdroplets as primordial compartments at the origins of life. PNAS 116(32): 15830–15835.

- Joyce GF (1989). RNA evolution and the origins of life. Nature 338(6212):217–224. [CrossRef]

- Kalambokidis M, Travisano M (2024). The eco-evolutionary origins of life. Evolution 78(1):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Kicsiny R, Bódai A, Székely L, Varga Z (2025). Extended discrete-time population model to describe the competition of nutrient-producing protocells. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 87(8):111. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy R, Hud N (2020) Introduction: Chemical Evolution and the Origins of Life. Chem Rev.120(11):4613-4615. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman SA (1993). The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution Oxford University Press.

- Keeling PJ (2004). Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts. American Journal of Botany 91(10), 1481–1493. [CrossRef]

- Eugene V. Koonin (2007). An RNA-making reactor for the origin of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 104(22):9101–9106. [CrossRef]

- King N, Westbrook MJ, Rokhsar D(2008). The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans. Nature 451(7180):783–788. [CrossRef]

- Lane N, Martin W (2010). The energetics of genome complexity. Nature, 467(7318):929–934.

- Lin S (2024). A decade of dinoflagellate genomics illuminating an enigmatic eukaryote cell. BMC Genomics 25:932. [CrossRef]

- Lincoln TA, Joyce GF (2009). Self-Sustained Replication of an RNA Enzyme. Science 323(5918):1229–1232. [CrossRef]

- Love GD, Grosjean E, Stalvies C, Fike DA, Grotzinger JP, Bradley, Kelly AE, Bhatia M,, Meredith W, Snape CE, Bowring SA, Condon DJ, Summons RE (2009). Fossil steroids record the appearance of Demospongiae during the Cryogenian period. Nature 457(7230):718-721.

- Lyons TW, Reinhard CT, Planavsky NJ (2014). The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506(7488):307–315. [CrossRef]

- Lyons TW, Diamond CW, Planavsky NJ, Reinhard CT, Li C (2021) Oxygenation, Life, and the Planetary System during Earth’s Middle History: An Overview. Astrobiology 21(8): 906–923. [CrossRef]

- Mänd K, Robbins LJ, Planavsky NJ, Bekker A, Konhauser KO (2021). Iron Formations as Palaeoenvironmental Archives, part of Elements in Geochemical Tracers in Earth System Science. Cambridge University Press Element, pp. 1-94.

- Mann S (2012). Review: Systems of Creation: The Emergence of Life from Nonliving Matter. Accounts of Chemical Research 45(12):2131-2141. [CrossRef]

- Martin W, Russell MJ (2007). On the origin of biochemistry at an alkaline hydrothermal vent. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 362(1486):1887–1925. [CrossRef]

- Maturana HR, Varela FJ (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. D. Reidel Publishing Company.

- Maynard Smith J, Szathmáry E (1995). The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Miller JG (1978). Living Systems. McGraw-Hill. pp. 1102.

- Mojzsis SJ, Arrhenius G, McKeegan KD, Harrison TM, Nutman AP, Friend CRL (1996). Evidence for life on Earth before 3,800 million years ago. Nature 384 (6604):55–59.

- Mojzsis SJ, Harrison TM, Pidgeon RT (2001). Oxygen-isotope evidence from ancient zircons for liquid water at the Earth's surface 4,300 Myr ago. Nature 409 (6817):178-181. [CrossRef]

- Moldavanov A (2021). Abiogenesis-Biogenesis Transition in Evolutionary Cybernetic System. Cybernetics and systems 53(2):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Nutman AP, Bennett VC, Friend CRL, Kranendonk MJV, Chivas AR (2016). Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature 537(7621):535–538. [CrossRef]

- Ohtomo Y, Kakegawa T, Ishida A, Nagase T, Rosing MT (2014). Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks. Nature Geoscience 7(1):25–28. [CrossRef]

- Pei ZC (2025). Biological evolution cybernetics. Journal of evolutionary biology research 9(1):12-31.

- Planavsky NJ, Asael D, Hofmann A, Reinhard CT, Lalonde SV, Knudsen A, Wang XL, Ossa FO, Pecoits E, Smith AJB, Beukes NJ, Bekker A, Johnson TM, Konhauser KO, Lyons TW, Rouxel OJ (2014). Evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis half a billion years before the Great Oxidation Event. Nature Geoscience 7 (4): 283-286. [CrossRef]

- Planavsky NJ, Reinhard CT, Wang XL,Thomson D, McGoldrick P, Rainbird RH, Thomas Johnson T, Fischer WW, Lyons TW (2014). Low Mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Nature 506:307-315. [CrossRef]

- Pleasant LG, Ponnamperuma C (1984). Chemical evolution and the origin of life: bibliography supplement. Orig Life Evol Biosph 15:55-69.

- Pressman A, Blanco C, Chen IA (2015). The RNA World as a Model System to Study the Origin of Life. Current Biology 25(19): R953–R963. [CrossRef]

- Ramstead MJD, Badcock PB, Friston KJ (2018). Answering Schrödinger’s question: A free-energy formulation. Physics of Life Reviews 24: 1–16.

- Ramstead MJD, Constant A, Badcock PB, Friston KJ (2019). Variational ecology and the physics of sentient systems. Physics of Life Reviews 31: 188–205. [CrossRef]

- Ricardo A, Carrigan MA, Olcott AN, Benner SA (2004). Borate minerals stabilize ribose. Science 303(5655):196. [CrossRef]

- Riding JB, Mantle DJ, Backhouse J (2010). A review of the chronostratigraphical ages of Middle Triassic to Late Jurassic dinoflagellate cyst biozones of the North West Shelf of Australia. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 162:543–575. [CrossRef]

- Riding JB, Head MJ (2018). Preparing photographic plates of palynomorphs in the digital age. Palynology 42(3):354–365. [CrossRef]

- Rimmer PB, Shorttle O (2019). Origin of life's building blocks in Carbon and Nitrogen rich surface hydrothermal vents. Life 9(1): 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/life9010012.

- Robbins LJ, Funk SP, Flynn SL, Warchola TJ, Li ZQ, Lalonde SV, Rostron BJ, Smith AJB, Beukes NJ, de Kock MO, Heaman LM, Alessi DS, Konhauser KO (2019). Hydrogeological constraints on the formation of Palaeoproterozoic banded iron formations. Nature Geoscience 12 (7):558-563. [CrossRef]

- Robertson MP, Joyce GF (2012). The Origins of the RNA World. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 4(5): a003608, pp. 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Rosing MT (1999). 13C-depleted carbon microparticles in >3700-Ma sea-floor sedimentary rocks from West Greenland. Science 283 (5402):674–676.

- Schopf JW (1993). Microfossils of the Early Archean Apex chert: new evidence of the antiquity of life. Science 260 (5108):640–646. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Mougoyannis P, Tarabella G, Adamatzky A (2022). A review on the protocols for the synthesis of proteinoids. [arXiv preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Sleep NH, Zahnle K, Neuhoff PS (2001). Initiation of clement surface conditions on the earliest Earth. PNAS 98 (7):3666-3672. [CrossRef]

- Strother PK, Battison L, Brasier MD, Wellman CH (2011). Earth’s earliest non-marine eukaryotes. Nature 473(7348):505-509.

- Szathmáry E (2015). Toward major evolutionary transitions theory 2.0. PNAS 112(33): 10104–10111. [CrossRef]

- Szostak JW, Bartel DP, Luisi PL (2001). Synthesizing life. Nature 409(6818):387–390. [CrossRef]

- Tang S, Gao M (2025). The Origin(s) of LUCA: Computer Simulation of a New Theory. Life 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Tashiro T, Ishida A, Hori M, Igisu M, Koike M, Méjean P, Takahata N, Sano Y, Komiya T (2017). Early trace of life from 3.95 Ga sedimentary rocks in Labrador, Canada. Nature 549(7673):516–518. [CrossRef]

- Tice MM, Lowe DR (2004).Photosynthetic microbial mats in the 3,416-Myr-old ocean. Nature 431 (7008): 549–552. [CrossRef]

- Valley JW, Peck WH, King EM, Wilde SA (2002). A cool early Earth. Geology 30 (4):351-354. [CrossRef]

- Vanchurin V, Wolf YI, Katsnelson MI, Koonin EV (2022). Toward a theory of evolution as multilevel learning. PNAS 119(6): e2120037119. Vanchurin V, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Katsnelson MI (2022). Thermodynamics of evolution and the origin of life. PNAS 119(6), e2120042119. Vay KL, Mutschler H (2019). The difficult case of an RNA-only origin of life. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences 3(5):469–475. [CrossRef]

- Villani M, Alboresi E, Serra R (2024). Models of Protocells Undergoing Asymmetrical Division. Entropy 26(4):281. [CrossRef]

- Wacey D, Kilburn MR, Saunders M, Cliff J, Brasier M (2011). Microfossils of sulphur-metabolizing cells in 3.4-billion-year-old rocks of Western Australia. Nature Geoscience 4(10): 698–702. [CrossRef]

- Wiener N (1948). Cybernetics: or control and communication in the animal and the machine. MIT Press.

- Williamson MP (2024). Autocatalytic selection as a driver for the origin of life. Life 14(5):590. [CrossRef]

- Yuan XL,Chen Z, Xiao SH, Zhou C, Hua H (2011). An early Ediacaran assemblage of macroscopic and morphologically differentiated eukaryotes. Nature 470 (7334): 390-393. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann J, Werner E, Sodei S, Moran J (2024). Pinpointing conditions for a metabolic origin of life: underlying mechanisms and the role of coenzymes.Accounts of Chemical Research 57(20), 3032–3043. [CrossRef]

- Zorc SA, Roy RN (2024). Origin & influence of autocatalytic reaction networks at the origin of life. RNA Biology 21(1):1023-1037.

- Zwicker D, Seyboldt R, Weber CA, Hyman AA, Jülicher F (2016). Growth and division of active droplets: a model for protocells. Physical Review Letters 116(9): e098102. [CrossRef]

| Feature | Value / Description | Geological Evidence |

| Ocean Temperature | ~90–120°C | |

| Ocean Oxygen | None | Zircon crystals (4.4 Ga): |

| pH | Acidic (~5 or lower) | Suggest liquid water was present soon after Earth’s formation. |

| Iron (Fe²⁺) | High | |

| Atmospheric CO₂ | Very high | |

| Atmosphere | Anoxic; mostly CO₂, N₂, H₂, H₂O vapor | Isotopic ratios in ancient rocks: Suggest early oceans were warm and reducing |

| Life | Absent | |

| Continents | None or proto-crus | No fossil evidence of life until ~3.5–3.8 Ga → supports that life hadn’t yet arisen when ocean was ~100°C. |

| Volcanic Activity | Intense | |

| Hydrothermal Systems | Active, possibly key for early chemistry |

| Parameter | Condition ca. 2 Ga | Geological Evidence |

| Oxygen (O₂) | Low, localized | Oxygen Rise (Great Oxidation Event, ~2.4–2.3 Ga): |

| Iron (Fe²⁺) | High | Banded Iron Formations (BIFs), Sulfur Isotopes (MIF-S) Disappear, Detrital Pyrite/Uraninite destroyed by O₂, Red Beds & Paleosols appeared. |

| Sulfate (SO₄²⁻) | Low | |

|

Methane (CH₄) |

High | |

| pH | ~6.5 (acidic) | Global Glaciations (Huronian & Makganyene, ~2.4–2.2 Ga): Glacial Deposits at Low Latitudes |

| Temperature | ~40–60°C | Early Life Expansion |

| Ocean Redox | Stratified: oxic surface, anoxic deep | Stromatolites: Common after ~2.7 Ga → microbial mats, including oxygenic phototrophs; Redox-stratified Oceans: Shallow O₂-rich zones, deeper anoxic waters |

| Banded Iron Formations | Still forming or waning | Crustal & Magmatic Activity: Large Igneous Provinces (~2.45 Ga): Supplied Fe²⁺ to oceans; drove massive BIF formation and nutrient cycling. |

| Nutrients | Low (especially nitrate, phosphate) | |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) |

High levels of CO₂ in both atmosphere and ocean |

Carbon Cycle Shift (Lomagundi Event, ~2.3–2.1 Ga): High δ¹³C in Carbonates |

| Parameter |

Condition (~2.0 Ga) | Geological Evidence |

| Atmospheric Oxygen | Rising O₂ levels after the Great Oxidation Event (~2.4–2.0 Ga); not yet modern levels | Banded Iron Formations (BIFs) decrease; Red Beds appear; Sulfur isotope fractionation (Δ³³S) declines |

| Ocean Chemistry | Stratified oceans: surface oxygenated, deep anoxic and sulfidic (euxinic) | BIFs, Fe-rich shales, and S-rich black shales in sedimentary records |

| Temperature | Likely warm but gradually cooling; some periods of glaciation may have begun earlier (~2.3 Ga) | Glacial deposits (Huronian glaciation), isotopic data from carbonates |

| UV Radiation | High UV levels due to lack of an ozone layer (low atmospheric O₂); early life likely lived underwater or in microbial mats | Stromatolite structures in shallow water environments (UV protection by mats) |

| Nutrient Availability | Increasing availability of nutrients (Fe²⁺, P) in oceans; biological productivity rising slowly | Isotopic signatures (δ¹³C), presence of trace metals in sedimentary rocks |

| Sulfur Cycle | Active sulfur cycling, possibly with sulfate-reducing bacteria | Sulfur isotope records (including mass-independent fractionation) |

| Methane Levels | Declining atmospheric CH₄ due to increased O₂ and lower methanogen activity | Carbon isotope excursions; drop in greenhouse warming potential |

| Tectonic Activity | Continents forming/supercontinent cycles starting (e.g., Columbia/Nuna); influencing ocean basins and nutrient input |

Zircon dating, sedimentary basins, supercontinent reconstructions |

| Biological Innovation | Rise of oxygen-using prokaryotes and possibly early eukaryotes; microbial mats and biofilms prevalent | Fossil evidence: microfossils (e.g., Grypania spiralis), biomarkers (steranes), stromatolites |

| Redox State of Oceans | Development of redox-stratified oceans; oxic-anoxic interfaces crucial for early metabolism evolution | Iron speciation studies in shales; presence of euxinic indicators like molybdenum and uranium enrichment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).