Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: Primary: 35Q84–49Q22–60H10–82C40–53C21. Secondary: 35A23–35B40 -68T07

1. Introduction

- Life began when environmental energy gradients and stochastic chemical reactions gave rise to spontaneously organized constraint fields.

- These emergent constraints stabilized and structured chemical dynamics, forming proto-organizational systems prior to the appearance of traditional biological macromolecules.

- Feedback loops between constrained chemical flows and the reinforcement of organizational structures promoted persistence, robustness, and evolutionary potential.

2. Conceptual Foundations: Constraints as the Primary Drivers of Life’s Emergence

2.1. What is a Functional Constraint?

- Selecting which reactions can occur within a region,

- Enhancing or suppressing reaction rates,

- Structuring spatial organization (e.g., confinement, selective permeability),

- Modulating energy dissipation pathways.

2.2. Constraint-Driven Organization vs. Molecule-Driven Evolution

- Molecules are substrates.

- Constraints are organizers.

- Selective Retention: Not all chemical outcomes are equally probable; constraint fields bias the system toward stability and self-reinforcement.

- Operational Closure: By regulating chemical flows, constraints enable the local generation of further constraints, closing causal loops.

- Proto-Individuality: Constraints delimit a “self”–a bounded domain maintaining internal coherence against external fluctuations.

2.3. Constraints as Dynamic, Self-Sustaining Structures

- Environmental energy gradients drive initial fluctuations.

- Spontaneous local structures arise that selectively stabilize certain flows.

- Stabilized flows reinforce the persistence of the structure, deepening the constraint.

- Constraint fields themselves evolve, merge, or decay, depending on the robustness of feedbacks.

2.4. From Proto-Constraints to Proto-Cells

- Support proto-metabolic cycles by stabilizing catalytic networks,

- Localize and protect informational molecules (e.g., RNA-like polymers),

- Guide the formation of semi-permeable membranes,

- Enable the system to resist entropy and maintain far-from-equilibrium organization.

3. Mathematical Framework: Modeling Constraint-Driven Emergence

3.1. State Variables

3.1.1. Chemical Concentrations

- is the local concentration (molarity or number density) of the i-th chemical species at spatial position and time t.

- N is the total number of distinct chemical species considered in the system.

- indicates that concentrations are non-negative by physical constraint.

3.1.2. Constraint Field

- measures the local intensity or “strength” of functional constraints acting on chemical processes at point and time t.

- Positive values of C correspond to stronger constraints (higher modulation of chemical flows), while corresponds to unconstrained dynamics.

- In principle, C can be generalized to a multi-component field (vector or tensor) if multiple independent types of constraints (e.g., permeability, catalysis, confinement) are to be modeled separately.

3.1.3. Environmental Free Energy Gradient

- represents the local free energy gradient available at position and time t.

- It models environmental conditions such as chemical potential gradients, temperature gradients, redox potentials, or light fluxes that can drive chemical flows.

- is treated as an external (non-dynamical) field at this stage but could itself be dynamically coupled to system behavior in extended models.

3.1.4. Summary: State Space

3.2. Evolution Equations

- Diffusion and spatial transport of chemical species,

- Local chemical reactions governed by internal states and constraints,

- Energy-driven source and sink dynamics influenced by environmental gradients.

3.2.1. Chemical Species Dynamics

-

Diffusion term:captures passive spreading of species i due to concentration gradients. Here, is the diffusion coefficient (constant or possibly dependent on C), and is the Laplacian operator over the spatial domain .Conceptually, diffusion tends to homogenize the chemical field, opposing spatial structure. Constraints (via C) must counteract this natural tendency to enable localization.

-

Reaction term:represents the net local chemical production or consumption of species i through interactions with other species , modulated by the local constraint field .Mathematically:where:

- -

- indexes the reaction channels,

- -

- are stoichiometric coefficients,

- -

- are rate laws (e.g., mass action, Michaelis-Menten) possibly modified by C.

In this way, C acts not only as a passive condition but can actively catalyze, inhibit, or otherwise bias reaction pathways. -

Source/Sink term:describes the influence of external energy inputs and sinks (e.g., light absorption, redox potential, environmental fluxes) on the chemical species.Example model:where is an effective coupling coefficient that may itself depend on the local constraint field.Conceptually, this term allows environmental gradients to feed into localized chemical dynamics in a constraint-modulated fashion.

3.2.2. Interpretation: Tension Between Homogenization and Localization

- Diffusive dispersion, driven by entropy and the tendency toward homogeneity,

- Reactive organization, driven by local chemistry and constraint amplification,

- Energy input, driven by the environment, modulated by constraints.

3.2.3. Mathematical Structure Summary

- ,

- ,

- and are vector-valued functions of chemical and constraint fields.

3.2.4. Constraint Field Dynamics

-

Constraint Production Term:represents the local generation or amplification of functional constraints as a function of:

- The local chemical composition ,

- The existing constraint field C,

- The available environmental free energy .

is a sensitivity parameter controlling the efficiency of constraint production.Conceptually, this term captures the feedback loop: organized chemical flows reinforce local structures (e.g., by building semi-permeable boundaries, concentrating catalysts, establishing selective gradients). -

Constraint Decay Term:models the natural degradation, dispersal, or weakening of constraints over time due to environmental fluctuations, diffusion, mechanical instability, or internal dissipation.Here, is a decay rate constant, representing the intrinsic instability of organizational structures in the absence of active maintenance.

-

Stochastic Perturbation Term:represents random environmental noise, local fluctuations, or perturbations affecting the constraint field.It can be modeled, for example, as Gaussian white noise:where controls the noise strength.Including stochasticity allows for:

- -

- Spontaneous symmetry breaking,

- -

- Emergence of localized structures from fluctuations,

- -

- Realistic modeling of noisy prebiotic environments.

3.2.5. Constraint Production Function

- F increases with concentrations of organizing species (e.g., catalysts, structural polymers),

- F may saturate (nonlinear feedback),

- F may depend multiplicatively on energy availability ,

- F may itself be enhanced by pre-existing C (positive reinforcement).

- are effectiveness coefficients for different chemical species,

- is a threshold parameter for energy dependence,

- controls feedback amplification by existing constraints.

3.2.6. Interpretation: Constraint Self-Maintenance vs. Collapse

3.2.7. Global Mathematical Structure

4. Organizational Closure and Viability Domains

4.1. Viability Domains in State Space

- Sustain the constraint field C above a critical threshold ,

- Maintain chemical concentrations within bounds that allow regeneration of C,

- Avoid collapse due to diffusion, decay, or depletion.

4.2. Mathematical Conditions for Organizational Closure

- Constraint Self-Maintenance Condition:where defines the spatial domain of the proto-individual.

- Chemical Stability Condition:meaning that internal concentrations remain bounded and stable within a viable range.

- Energy Supply Condition:ensuring that external energy gradients are sufficient to sustain reaction dynamics and constraint regeneration.

4.3. Attractor Structure and Robustness

- Linear stability analysis (e.g., eigenvalue spectra of linearized dynamics near ),

- Stochastic resilience analysis (how constraint fields recover after noise-induced perturbations),

- Basin size estimation (measuring the volume of viable initial conditions).

4.4. Emergence of Individuality

- Boundary Formation: Sharp gradients of define an “inside” and “outside”.

- Selective Interaction: Internal states interact selectively with external flows based on constraint-mediated transport.

- Self-Maintenance: Internal reactions are organized to regenerate both chemical species and constraint structures.

4.5. Phase Transition to Organizational Closure

- Below critical conditions, chemical reactions and constraints dissipate.

- Above critical conditions, self-sustaining, self-producing constraint-chemical loops emerge.

4.6. Minimal Requirements for Constraint Self-Maintenance

4.6.1. Constraint Production Must Outweigh Constraint Decay

- is the efficiency of constraint generation from chemical organization,

- is the local constraint production function (possibly nonlinear in and ),

- is the decay constant for constraint weakening.

- Growing () when organizational processes reinforce the structure,

- Or at least sustained () against natural decay.

4.6.2. Stabilization of Chemical Flows within Constrained Domains

- is the bare diffusion coefficient of species i in the unconstrained environment,

- is the effective diffusion coefficient under the influence of the local constraint field .

- Reduce random diffusion,

- Enhance confinement and reactant localization,

- Facilitate high local concentrations for reaction dynamics.

- Semi-permeable barriers,

- Catalytic scaffolds,

- Local energy traps.

4.6.3. Energy Flow Must Sustain Internal Reactions and Constraints

- The energetic cost of internal reactions,

- The energy required for constraint reinforcement,

- Dissipative losses due to leakage, decay, and noise.

- Reactions halt,

- Constraints decay (),

- Organizational closure collapses.

4.6.4. Summary: Triple Minimal Conditions

4.7. Toward Proto-Individuality: Constraint-Bounded Domains

4.7.1. Definition of Proto-Individuals

- is the local constraint field intensity,

- is the minimal threshold required for sustained chemical and constraint self-organization.

4.7.2. Properties of Proto-Individuals

- Internal Chemical Coherence: Chemical concentrations inside are stabilized and maintained within viable bounds, enabling sustained reaction dynamics.

- Sustained Constraint Regeneration: Internal chemical processes regenerate and maintain the constraint field C, ensuring organizational closure:thereby avoiding collapse due to natural decay.

-

Selective Matter and Energy Exchange: The boundary of acts as an emergent semi- permeable membrane:

- -

- Nutrients and energy flow in,

- -

- Waste products flow out,

- -

- Diffusive losses of key internal components are minimized.

Transport across the boundary is regulated dynamically by the structure and gradients of C.

4.7.3. Conceptual Interpretation: Birth of Individuality

- Self vs Environment Distinction: defines an “inside” (where organizational rules prevail) and an “outside” (dominated by unstructured chemistry).

- Operational Closure: Internal processes are organized such that they collectively maintain the boundary and internal conditions necessary for their own persistence.

- Autonomy: Proto-individuals exert causal control over their own material constitution and energy budget, rather than being passively shaped by external conditions.

4.7.4. Dynamic Behavior of Proto-Individuals

- Growth: Expansion of as internal constraint strength and chemical resources increase.

- Division: Fission into two daughter proto-individuals if internal dynamics and spatial instabilities create multiple stable centers of constraint generation.

- Decay: Shrinkage or dissolution of when internal constraint production falls below viability thresholds.

- Evolutionary Variation: Differences in internal chemical compositions or constraint structures can lead to differential viability and adaptive evolution under environmental pressures.

5. Organizational Closure via Constraint Networks

5.1. Definition of Organizational Closure

- Every critical functional process (e.g., constraint maintenance, catalytic activity, compartmental stability) is produced and maintained by other processes within the system,

- No critical component depends exclusively on uncontrolled environmental inputs for its regeneration,

- The system as a whole maintains its boundary conditions and identity despite fluctuations and perturbations.

5.2. Structure of Constraint Networks

- Nodes correspond to localized chemical processes or organizational structures (e.g., catalytic loops, selective barriers, energy sinks),

- Edges represent functional dependencies mediated by constraint fields (e.g., one process stabilizing or enabling another),

- Feedback Loops are closed cycles where processes mutually support each other’s continuation.

- V is the set of organizational processes,

- is the set of directed edges indicating “process A enables process B.”

5.3. Feedback and Mutual Reinforcement

- Positive feedback loops: Enhancing the persistence of constraint structures and chemical organization.

- Negative feedback loops: Regulating fluctuations and preventing destructive runaway dynamics (e.g., uncontrolled chemical explosions).

- Nonlinear Couplings: Enabling threshold behaviors, bistability, and multistability, essential for robustness against noise.

5.4. Stability of Constraint-Closed Systems

- Linear Stability Analysis: Examining the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix of the coupled dynamical system near steady states.

- Attractor Structure: Identifying stable attractors (fixed points, limit cycles, or strange attractors) associated with constraint-closed regimes.

- Perturbation Resilience: Assessing how small environmental or internal perturbations are absorbed or amplified by the system dynamics.

5.5. Emergence of Viable Units of Evolution

- Persist: Maintain coherence over time in fluctuating environments.

- Reproduce: Undergo fission or budding when internal constraint structures replicate.

- Evolve: Accumulate variations in internal network architecture leading to differential survival and reproduction.

5.6. Summary

- It endows the system with autonomy, self-maintenance, and evolutionary potential.

- It emerges naturally from coupled constraint-chemical feedbacks under suitable energetic and material conditions.

- It defines the fundamental threshold that separates non-living matter from living organizations.

5.7. Defining Organizational Closure

5.7.1. Conceptual Definition

- Produce, maintain, and regulate the very organizational structures (constraints) necessary for their own continuation,

- Stabilize internal dynamics despite environmental fluctuations,

- Maintain an operational boundary distinguishing “self” from “non-self.”

5.7.2. Formal Mathematical Conditions

- defines the spatial domain of the proto-individual,

- The approximate stationarity () reflects the maintenance of a steady dynamic regime (e.g., limit cycles or steady states), allowing small fluctuations around a stable core.

5.7.3. Self-Sustaining Constraint-Chemistry Feedback

- Constraint → Chemistry: The constraint field modulates local reaction rates, stabilizes internal chemical compositions, and confines reactants.

- Chemistry → Constraint: Internal chemical processes regenerate and reinforce the constraint field, maintaining against natural decay.

5.7.4. Critical Thresholds for Closure

- The constraint field strength exceeds a critical value ,

- Chemical concentrations fall within viability ranges supporting sufficient constraint regeneration,

- External energy flux remains above a critical threshold .

5.7.5. Interpretation: Emergent Autonomy and Selfhood

- The system no longer depends on continuous external scaffolding for survival,

- It sustains itself through internally organized, mutually supportive processes,

- It can maintain individuality, adapt, and even evolve in fluctuating environments.

5.7.6. Summary

5.8. Feedback Loop Structure

5.8.1. Minimal Organizational Feedback Loop

- Environmental Gradient: External energy differentials (e.g., chemical potentials, thermal gradients, light fluxes) provide the driving forces necessary to power endergonic chemical reactions.

- Chemical Organization: Under the influence of energy flows, localized chemical networks (e.g., catalytic cycles, autocatalytic sets) emerge and organize, producing nontrivial spatial and functional patterns.

- Constraint Field Strengthening: Organized chemical networks generate and reinforce local constraint fields –structures that restrict, channel, or enhance specific reaction pathways and material flows.

- Stabilized Chemical Flows: The presence of strong constraints stabilizes internal chemical dynamics, enhancing reaction efficiencies, localizing reactants, and buffering against dispersive entropy.

- Sustained Constraint: Stabilized chemical flows, in turn, continually regenerate the constraint field, closing the causal loop and enabling self-maintenance.

5.8.2. Properties of the Feedback Loop

-

Closed: Every critical functional step in the loop is internally generated and maintained; no external agency or template is required beyond the basic environmental energy gradient.Mathematically, closure corresponds to the condition that all necessary variables are sustained dynamically through internal interactions:

-

Robust: The feedback loop can absorb small environmental perturbations (e.g., fluctuations in resource availability, temperature, noise) without systemic collapse.Stability analysis shows that perturbations decay over time:

-

Adaptive: Variations in the environmental gradient can modulate internal chemical and constraint dynamics without disrupting overall organizational coherence.For moderate changes in , the system dynamically adjusts its internal flows and constraint strengths to maintain viability.

5.8.3. Interpretation: Causal Self-Production

- Energy and matter are continuously transformed internally,

- Structural constraints are regenerated endogenously,

- The system persistently rebuilds itself from its own products and processes.

5.8.4. Comparison with Classical Systems

- Actively sustain non-equilibrium conditions rather than passively dissipating them,

- Self-referentially produce the organizational structures that maintain the system,

- Possess causal closure, forming autonomous operational units rather than merely reflecting external conditions.

5.9. Mathematical Stability Conditions

5.9.1. Constraint Regeneration Dominates Constraint Decay

- is the constraint production efficiency,

- encodes how chemical organization and energy flow generate constraints,

- is the intrinsic decay constant of the constraint field C.

5.9.2. Chemical Stability within Constraint Domains

- Internal concentration gradients are small,

- Diffusive losses are negligible compared to local chemical reactions,

- Spatial homogeneity (or structured inhomogeneity) is dynamically stabilized by constraint-mediated confinement.

5.9.3. Selective Exchange Across Proto-Individual Boundaries

- Import of nutrients, energy carriers, or building blocks from the environment,

- Export of waste products, dissipative byproducts, and excess energy.

- is the flux of species i,

- is the outward normal vector at the boundary,

- is a function specifying controlled flux depending on constraint strength and local energy availability.

- Permeability is modulated by the local constraint field C, not imposed externally,

- Exchange remains selective, preventing catastrophic mixing or resource depletion.

5.9.4. Summary of Minimal Stability Conditions

5.10. Closure as a Phase Transition

5.10.1. Pre-Closure Regime: Open Dissipative System

- Passive Dissipation: Energy from the environment is absorbed and dissipated without internal organization.

- Unstable Constraints: Any transient constraint structures decay rapidly ().

- Chemical Homogenization: Diffusion dominates, leading to uniform chemical distributions without localized dynamics.

- No Individuality: There is no persistent boundary separating “self” from “environment.”

5.10.2. Critical Threshold: Organizational Bifurcation

- Self-reinforcing feedback loops become possible,

- Constraints can sustain themselves against decay,

- Chemical flows become localized and organized.

- The emergence of convection rolls in Rayleigh-Bénard systems,

- The spontaneous magnetization of a ferromagnet below Curie temperature,

- Percolation transitions in random networks.

5.10.3. Post-Closure Regime: Autonomous Organization

- Self-Maintenance: Internal chemical processes continually regenerate constraints.

- Localized Persistence: Spatially bounded proto-individuals emerge and maintain internal coherence.

- Robustness and Adaptation: The system can absorb moderate environmental perturbations while preserving identity.

- Evolutionary Potential: Variations in organizational structures can propagate and be subject to selection.

5.10.4. Causal Architecture Transformation

- Before closure: Environmental conditions fully determine internal dynamics (external causality dominates).

- After closure: Internal organizational dynamics maintain and regulate themselves (internal causality emerges).

- Mutual Modulation: The system can now modulate its own responses to environmental changes, enabling functional autonomy and adaptive evolution.

5.10.5. Summary

- Spontaneous emergence of constraint-maintaining cycles,

- Stabilization of localized chemical domains,

- Transition from passive dissipation to active autonomy,

- The birth of proto-individuals capable of evolution.

5.11. Emergence of Evolutionary Potential

5.11.1. Variation in Constraint Architectures

- Changes in the topology of constraint networks (e.g., addition or loss of nodes or feedback links),

- Alterations in the strength and spatial localization of constraint fields,

- Variations in chemical species abundances, reaction rates, or permeability profiles.

5.11.2. Differential Viability and Functional Selection

- Some variations may enhance constraint regeneration rates, robustness to noise, or efficiency of energy and matter use,

- Others may weaken organizational closure, making systems more prone to collapse under perturbations.

5.11.3. Evolutionary Dynamics Without Genetic Templates

- The self-sustaining constraint-chemical organization,

- Defined by its dynamic topology and material flows,

- Reproducing and varying through organizational fission, fragmentation, or extension.

5.11.4. Proto-Evolutionary Regime

- Heritable Variability: Variations in organizational patterns are passed to offspring during fission or growth.

- Differential Persistence: More robust, efficient, or adaptable proto-individuals outlast less viable variants.

- Open-Ended Complexity: There is potential for cumulative organizational innovation over time.

5.11.5. Summary

- Variation arises from internal dynamics and environmental perturbations,

- Selection operates at the level of entire constraint-maintaining organizations,

- Adaptation, diversification, and complexity become possible even before the advent of genetic information systems.

6. A Minimal Toy Model for Constraint-Driven Organization

6.1. State Variables

- : concentration of resource molecule A,

- : concentration of intermediate species B,

- : concentration of constraint-building molecule C,

- : intensity of the local constraint field,

- : external energy or resource gradient.

6.2. Reaction Scheme

6.3. Evolution Equations

6.3.1. Chemical Species Dynamics

- are the baseline diffusion coefficients,

- is a source term maintaining A under external gradient ,

- and are effective diffusion coefficients modulated by the constraint field.

6.3.2. Constraint Field Dynamics

- is the constraint production efficiency,

- is the natural decay rate of the constraint field.

6.4. Summary of Parameters

- : reaction rates,

- : baseline diffusion coefficients,

- : constraint field dynamics parameters,

- : constraint feedback strength on diffusion,

- : external resource/energy gradient.

6.5. Expected Dynamics

- Below a critical input energy threshold, no sustained organization arises: reactions dissipate randomly.

- Above the threshold, localized regions rich in C and form.

- Within these regions, diffusion is slowed, allowing for the maintenance of internal reaction cycles.

- Proto-individuals emerge as dynamically maintained chemical-constraint domains.

7. Extension to Three-Dimensional Constraint Emergence

7.1. System Setup

- : concentration of resource molecule,

- : concentration of intermediate species,

- : concentration of constraint-building molecule,

- : intensity of the constraint field,

- : external energy/resource gradient (fixed or slowly varying).

7.2. Reaction Scheme

7.3. Governing Equations

7.3.1. Chemical Species Dynamics

- are the baseline (unconstrained) diffusion coefficients of species A, B, and C,

- are kinetic rate constants for the respective reactions,

- is an external source term representing a supply of A, driven by the environmental energy gradient .

7.3.1.1. Terms Explanation.

- : Represents isotropic spatial diffusion of chemical species, tending to homogenize concentrations.

- : Autocatalytic production term for B, fueled by consumption of A.

- : Transformation of intermediate B into constraint-building molecule C.

- : Natural decay or degradation of C.

7.3.2. Modulation of Diffusion by Constraints

7.3.2.1. Interpretation.

- In regions where is low (weak constraints), diffusion proceeds close to baseline rates .

- In regions where is high (strong organizational constraints), diffusion is significantly reduced, leading to spatial confinement of chemical species.

- Chemical flows are slowed and localized by self-generated constraints,

- Molecular species accumulate and interact more efficiently within organized domains,

- Autonomous regions (proto-individuals) emerge through self-reinforcing feedback between chemistry and organization.

7.3.2.2. Biophysical Analogy.

- Reduced diffusion inside cellular compartments,

- Crowding effects in cytoplasm,

- Selective permeability of membranes and cytoskeletal scaffolds.

7.3.2.3. Nonlinear Coupling.

- Local concentrations influence constraint generation,

- Constraints, in turn, modify local transport properties,

- This two-way feedback creates the conditions for emergent organizational closure.

7.3.3. Constraint Field Dynamics

- is the rate at which the chemical species C generates or reinforces constraints,

- is the natural decay rate of constraints in the absence of sustaining chemical activity.

Interpretation.

- The presence of C molecules actively promotes the build-up of organizational structures, represented by the local increase in .

- In the absence of continuous chemical support (i.e., if C vanishes), the constraint field spontaneously decays over time, modeling physical degradation or loss of functional structure.

Steady-State Solution.

Non-Equilibrium and Dynamical Effects.

- Rapid production of C can lead to the fast emergence of constraint-bounded domains.

- Variations in C can induce dynamic changes in , modulating the system’s organization over time.

- Spatial heterogeneity in C creates a patterned constraint landscape, supporting localized, autonomous behavior.

Mathematical Properties.

Biological and Physical Analogies.

- Cellular membranes, structural proteins, and regulatory complexes require continuous molecular turnover.

- Spatial organization in biological systems is inherently dynamic, arising from constant energy and matter flows.

7.4. Laplacian Operator in Three Dimensions

Interpretation.

Fields Involved.

- : concentration of the resource molecule,

- : concentration of the intermediate species,

- : concentration of the constraint-producing molecule.

7.4.1. Numerical Discretization: 6-Point Stencil

Boundary Conditions.

Computational Considerations.

- Second-order accurate in space,

- Explicit and local (only nearest neighbors needed),

- Efficient for large-scale simulations,

- Easily parallelizable on CPUs or GPUs.

7.5. Boundary Conditions

Physical Interpretation.

- There is no net diffusive flux of matter or constraint across the boundaries.

- Chemical species and constraint fields are reflected at the domain edges rather than absorbed or transmitted.

- The system is effectively "closed" with respect to spatial transport, though external sources (e.g., energy input gradients) may still operate internally.

Mathematical Implementation.

- At the minimum boundary (e.g., ), set ,

- At the maximum boundary (e.g., ), set ,

Computational Advantages.

- Simplicity: requires no additional ghost layers or complex extrapolations,

- Stability: preserves the internal dynamics without artificial losses,

- Physical relevance: appropriate for modeling proto-systems attempting to self-enclose.

Alternative Boundary Conditions.

- Dirichlet conditions () model fixed boundary concentrations, e.g., contact with an infinite reservoir,

- Periodic conditions () model spatially continuous systems without boundaries (e.g., early ocean scenarios).

7.6. Expected Phenomena in Three Dimensions

- Emergence of volumetric constraint-bounded domains (proto-vesicles),

- True spatial separation of interior and exterior chemical environments,

- Dynamic stabilization of autonomous constraint-maintained structures,

- Possible self-division and budding events,

- Hierarchical organization and compartmentalization phenomena.

8. Phase Space Structure for Constraint Emergence

8.1. Dimensionless Parameters

- : ratio of autocatalytic production to diffusion for the resource molecule A,

- : rate of transformation from B to C relative to diffusion,

- : decay rate of C relative to its diffusion,

- : effective strength of constraint feedback on diffusion,

- : ratio of constraint production to constraint decay.

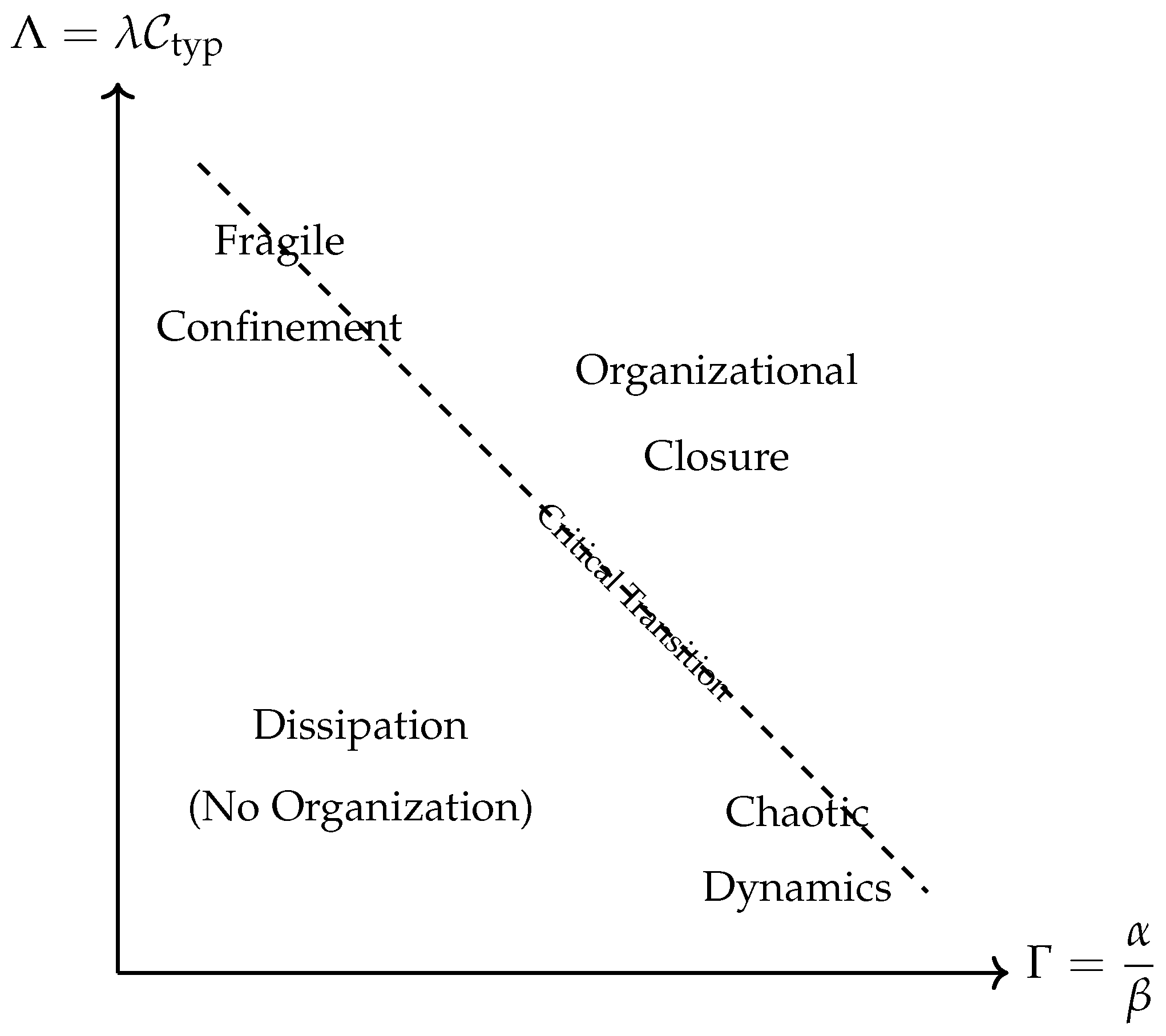

8.2. Phase Diagram Axes

- The system’s ability to sustain self-generated constraints (),

- The system’s ability to modulate internal diffusion based on constraint fields ().

8.3. Behavioral Regimes

- Low , Low : Diffusion dominates; no sustained organization; purely dissipative structures.

- High , Low : High constraint production, but insufficient spatial regulation; chaotic or unstable chemical patterns.

- Low , High : Strong spatial confinement, but insufficient self-maintenance; fragile, transient structures.

- High , High : Emergence of stable, localized, constraint-maintained domains; proto-autonomous individuals.

8.4. Critical Transition

8.5. Implications for Simulations

- The constraint production rate and decay rate (thus modifying ),

- The strength of constraint feedback (thus modifying ).

- Average lifetime of constraint-bounded regions,

- Size distribution of organized domains,

- Degree of internal chemical coherence,

8.6. Summary Table

| Regime | Behavior | Interpretation |

| Low , Low | Diffusion dominates | No organization, noise |

| High , Low | Chaotic chemical dynamics | Energy-rich but unstable |

| Low , High | Confinement but decay | Fragile compartments |

| High , High | Emergent autonomy | Proto-individuals, closure |

9. Discussion and Implications

9.1. From Molecules to Organization

- The first replicators (e.g., RNA molecules),

- The first metabolic cycles (e.g., reverse citric acid cycle),

- The first compartments (e.g., lipid vesicles).

- Life begins not with molecules, but with the self-organization of functional relationships,

- These relationships materialize as constraint networks regulating matter and energy flows,

- Chemical and spatial structures are shaped by, and sustain, internal organizational logic.

9.2. Mathematical Contributions

- The coupled dynamics of chemical fields and constraint fields C,

- The emergence of viability domains in state space,

- The conditions for organizational closure as a non-equilibrium phase transition,

- The robustness, resilience, and adaptive potential of proto-individuals.

- Stability and instability of organizational attractors,

- Bifurcation phenomena associated with closure and collapse,

- Evolutionary dynamics arising from constraint-driven selection.

9.3. Philosophical and Foundational Implications

- Life as Organization: Life is fundamentally an organizational phenomenon, not a molecular or thermodynamic anomaly.

- Causal Autonomy: True biological individuality emerges when systems gain internal causal closure, allowing them to maintain and regulate themselves despite environmental fluctuations.

- Continuity of Complexity: Life and non-life are not separated by a sharp molecular boundary, but by a phase transition in dynamical organization.

- Pre-Genetic Evolution: Evolution by selection on organizational structures predates the emergence of templated genetic replication.

9.4. Experimental and Synthetic Implications

- Designing Proto-Individuals: Constructing artificial systems where chemical reactions self-organize constraint fields, leading to sustained localized structures.

- Testing Phase Transition Hypotheses: Observing critical thresholds where passive chemical systems become autonomously organizing under varying environmental gradients.

- Minimal Life Simulations: Simulating constraint-chemical feedback systems to study the emergence of viability domains, robustness, and proto-evolutionary behaviors.

- Energy Flow Experiments: Testing how sustained energy gradients influence the emergence and maintenance of constraint-closed systems.

9.5. Broader Implications

- The evolution of biological complexity (e.g., emergence of multicellularity),

- The origin of cognitive and social systems (organizational closure at higher levels),

- Artificial life and synthetic biology (designing constraint-sustaining autonomous systems),

- The search for extraterrestrial life (identifying signs of organizational autonomy rather than specific molecular markers).

9.6. Summary

9.7. Comparison with Traditional Theories

- Metabolism-First Approaches: These theories focus on the spontaneous emergence of autocatalytic cycles and energy-driven reaction networks that could sustain themselves independently of genetic templates [8,10]. They highlight the thermodynamic necessity of maintaining far-from-equilibrium states through chemical fluxes.

- Compartment-First Approaches: These models propose that spatial compartmentalization–the formation of lipid vesicles or protocells–was the first critical step, enabling localized reaction environments protected from external perturbations [5].

- Metabolism models elucidate how chemical networks could self-sustain energetically.

- Replication models explain how heredity and evolution could become possible.

- Compartmentalization models clarify how individuality and internal coherence could be achieved.

9.7.1. Limitations of Reductionist Approaches

- Replication without metabolism lacks an energy and material basis for sustaining copying.

- Metabolism without information lacks directionality and evolutionary adaptability.

- Compartments without internal organization are merely passive enclosures, easily dissipated.

9.7.2. Constraint Emergence Hypothesis: A Holistic Framework

- Life emerged not from the dominance of one subsystem, but from the co-emergence and mutual reinforcement of metabolic, informational, and structural constraints.

- These subsystems were tightly coupled from the outset through dynamic feedback loops, enabled by environmental gradients and internal organizational dynamics.

- Organizational closure–not molecular replication or metabolic flux alone–defines the critical transition into autonomy and evolutionary competence.

9.7.3. Summary

- The indispensability of integrating energy flow, information storage, and spatial organization from the outset,

- The central role of dynamical constraints and feedback structures,

- The emergence of life as a phase transition in organizational dynamics, not a simple molecular event.

9.8. Experimental Implications

9.8.1. Focus on Constraint Formation

- Identifying environmental gradients (chemical, thermal, redox, electrochemical) that drive self-organization,

- Observing how coupled reaction-diffusion systems generate localized regions of functional constraint (e.g., catalytic scaffolds, semi-permeable barriers, energy concentration zones),

- Measuring the persistence, robustness, and feedback effects of emergent constraint structures.

9.8.2. Design of Synthetic Proto-Systems

- Coupled chemical networks embedded in spatially structured environments (e.g., microfluidic gradients, porous matrices),

- Energy-driven reaction systems (e.g., redox couples, light-activated reactions) under sustained non-equilibrium conditions,

- Incorporating materials or mechanisms that allow for self-assembling selective barriers and internal energy recycling loops.

9.8.3. Minimal Autonomy Experiments

- Maintain internal organization via self-produced constraints,

- Regulate matter and energy intake and waste expulsion,

- Exhibit resilience to environmental perturbations,

- Possibly undergo fission or variation under suitable conditions.

- The formation of spatially bounded, stable chemical domains,

- Fluctuation-driven transitions from passive dissipation to active self-organization,

- Measurements of constraint field strength, chemical stabilization, and persistence over time.

9.8.4. Toward a Unified Experimental Framework

- Systems Chemistry: Understanding how chemical complexity arises and stabilizes under flow conditions,

- Synthetic Biology: Engineering life-like properties into non-living matter,

- Complex Systems Physics: Modeling critical transitions, emergent behaviors, and self- organized criticality.

9.8.5. Summary

- Test the minimal requirements for life-like autonomy,

- Reproduce critical organizational phase transitions in the laboratory,

- Discover alternative life-like systems independent of contemporary biochemistry,

- Illuminate the universal pathways through which matter self-organizes into living organization.

9.9. Philosophical and Theoretical Implications

9.9.1. Life as Organization of Constraints

- Life is a property of organized constraints– dynamically maintained structures that regulate and shape flows of matter and energy to sustain themselves.

- Biological individuality arises from the emergence of autonomous constraint-maintaining systems, not from the passive aggregation of complex molecules.

- Material substrates matter, but only insofar as they support the self-production of organizational closure.

9.9.2. Emergence without Design

- No external design, teleology, or pre-existing genetic blueprint is necessary for the emergence of life-like systems.

-

Self-producing organizations can spontaneously arise under suitable energetic and material conditions, driven by:

- -

- Environmental gradients (energy sources),

- -

- Stochastic fluctuations (variation and diversity),

- -

- Dynamical feedback (self-reinforcement of constraints).

- Purpose, functionality, and selfhood emerge a posteriori as properties of dynamically sustained constraint networks.

9.9.3. Universality of Life

- Organizationally universal: Wherever matter and energy can self-organize into constraint-closed, self-maintaining systems, life-like phenomena could emerge.

- Chemically agnostic: Life may not require carbon, water, or Earth-like environments, but merely the right conditions for organizational closure and constraint generation.

- Emergent across scales: Similar principles may underlie the emergence of cognitive systems, ecosystems, social organizations, and even technological autonomous agents.

9.9.4. Toward a Unified Science of Autonomous Systems

- Prebiotic chemistry,

- Biological origins,

- Cognitive emergence,

- Artificial life and synthetic autonomous systems,

- Universal evolutionary dynamics across substrates and scales.

9.9.5. Summary

- Life is not a substance, but a dynamical process of autonomous constraint self-organization,

- No external design is needed; organization emerges naturally from internal dynamics under suitable conditions,

- Life may be a universal outcome of complex systems evolution, not a rare anomaly.

9.10. Future Directions

9.10.1. Detailed Mathematical Analysis

- Stability Analysis: Characterizing the attractor structures corresponding to constraint-closed states and determining their domains of attraction under perturbations.

- Bifurcation Theory: Identifying critical parameters where transitions occur between dissipative, closed, and collapsed regimes; understanding phase diagrams and organizational thresholds.

- Pattern Formation: Studying spatial and temporal patterns arising from constraint-chemical feedbacks, including localization phenomena, wavefronts, and oscillatory structures. Analogous mechanisms have been mathematically modeled in biological pattern formation [15], although our emphasis is on organizational autonomy.

- Critical Phenomena: Investigating whether the transition to closure exhibits features of criticality, such as scaling laws, universality classes, and self-organized criticality.

9.10.2. Simulation of Constraint Fields and Proto-Individual Dynamics

- Developing spatially resolved models of coupled reaction-diffusion-constraint systems,

- Simulating the spontaneous formation, growth, fission, and decay of constraint-bounded proto-individuals,

- Exploring the evolutionary dynamics of constraint networks under stochastic perturbations and resource limitations,

- Visualizing transitions from passive dissipation to autonomous closure across parameter spaces.

9.10.3. Synthesis of Proto-Constraints in Laboratory Systems

- Engineering chemical networks capable of generating localized constraints (e.g., catalytic scaffolds, microcompartment formation),

- Designing physical setups where environmental gradients can drive the emergence of organizational feedbacks,

- Demonstrating minimal systems exhibiting self-sustained constraint-chemical cycles and proto-individual behavior,

- Exploring transitions between organizational collapse, metastability, and robust autonomy.

9.10.4. Interdisciplinary Integration

- Systems Chemistry: Understanding how chemical complexity arises and self-organizes under flow.

- Synthetic Biology: Designing life-like properties in non-living matter.

- Complex Systems Physics: Modeling criticality, emergence, and self-organization.

- Philosophy of Biology: Revisiting fundamental questions about individuality, autonomy, and the nature of life.

9.10.5. Summary

- Develop rigorous mathematical frameworks for constraint-driven organization,

- Simulate the emergence and evolution of constraint fields in complex chemical systems,

- Build minimal synthetic systems demonstrating organizational closure in the laboratory,

- Integrate insights from chemistry, biology, physics, and philosophy to build a unified science of autonomous systems.

10. Conclusions

- A unified understanding of metabolism, information, and compartmentalization as emergent from constraint-driven self-organization,

- New experimental and computational avenues for the synthesis and study of minimal autonomous systems,

- A broader philosophical and scientific foundation for thinking about life as a universal phenomenon of complex systems.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mouhot, C., & Otto, F. (2023). Transport metrics and phase transitions for spatially inhomogeneous kinetic equations. Communications in Mathematical Physics.

- Desvillettes, L., & Trescases, A. (2022). Trend to equilibrium for reaction–diffusion systems arising from complex balanced chemical reaction networks. SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis.

- Eigen, M., & Schuster, P. (1979). The Hypercycle: A Principle of Natural Self-Organization. Springer.

- Gilbert, W. (1986). The RNA World. Nature, 319(6055), 618.

- Deamer, D. (2011). First Life: Discovering the Connections between Stars, Cells, and How Life Began. University of California Press.

- Maturana, H., & Varela, F. (1972). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. D. Reidel Publishing Company.

- Moreno, A., & Mossio, M. (2015). Biological Autonomy: A Philosophical and Theoretical Enquiry. Springer.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1986). Autocatalytic sets of proteins. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 119(1), 1?24.

- Morowitz, H. J. (1992). Beginnings of Cellular Life: Metabolism Recapitulates Biogenesis. Yale University Press.

- Luisi, P. L. (2006). The Emergence of Life: From Chemical Origins to Synthetic Biology. Cambridge University Press.

- Gánti, T. (1971). The Principles of Life. Oxford University Press (English translation).

- Carlen, E. A., & Maas, J. (2023). Nonlinear flows and gradient flow structures in the Wasserstein space. Journal of Functional Analysis.

- Guerra, G. Y., & Degond, P. (2023). Emergence of collective organization in agent-based models: A mean field game perspective. Journal of Mathematical Biology.

- Burger, M., & Velichkov, B. (2022). Mathematical models of biological pattern formation. In Handbook of Mathematical Models in Life Sciences. Springer.

- Barbachoux, C., & Kouneiher, J. (2025). Analytical and geometric foundations and modern applications of kinetic equations and optimal transport. To be published in Special issue : Mathematical and Statistical Methods and Their Applications, 2nd Edition, Axioms.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).