1. Introduction

Erwin Schrödinger’s legacy as a founder of quantum mechanics is well established. The centennial of his major contributions is upon us. His 1926 wave equation became the basis for all of quantum mechanics and he won a Nobel Prize for this contribution in 1933 (Schrödinger 1926). Despite his acknowledged status as a seminal leader in quantum theory his ontological vision of a purely wave-based reality remains under-developed and under-appreciated.

Schrödinger resisted the Copenhagen interpretation, which dominated quantum theory for decades, lamenting its abandonment of continuity and determinism in favor of probabilistic and particle-centric formulations. His “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment, in which a cat is placed inside a box with a vial of cyanide and a quantum trigger for breaking the vial, suggests that the cat exists in a strange limbo state, being both dead and alive, until an observer opens the box. Schrödinger offered this thought experiment specifically to criticize the problems of the Copenhagen interpretation—and yet today few people understand or agree with the nature of Schrödinger’s critique.

Toward the end of his life, in a 1959 letter, he insisted that “all is waves,” expressing his belief that wave mechanics should extend beyond its mathematical utility for the Copenhagen interpretation to a comprehensive ontology of nature (Moore 1989).

Einstein famously shared Schrödinger’s dissatisfaction with the Copenhagen school. Both were deeply concerned with the conceptual foundations of quantum mechanics and resisted the epistemic interpretation of the wave function as merely a tool for predicting probabilities. Einstein’s pursuit of a unified field theory and his late-career revival of ether-like concepts as dynamic fields align closely with Schrödinger’s wave-based ontology. Einstein wrote in 1930, “We may therefore regard matter as being constituted by the regions of space in which the field is extremely intense … There is no place in this new kind of physics both for the field and matter, for the field is the only reality” (Einstein 1930).

The Quantum Ocean Theory (QOT) theory continues this lineage, imagining a coherent extension of Schrödinger’s and Einstein’s ideas while integrating insights from Bohm’s deterministic quantum theory and Bell’s work on non-locality. By positing that the “quantum ocean” is a dynamic, oscillatory medium from which all forces and matter arise, QOT offers a unified view of particles, forces, and spacetime as emergent phenomena. Indeed, in QOT “all is waves.” It’s all waves, all the way down.

The quantum ocean we propose differs fundamentally from the quantum ocean state (the lowest energy state of quantum fields). Rather, it represents an active, oscillatory medium underlying all physical phenomena—a substrate supporting wave propagation at various frequencies, with different forces emerging as distinct wave patterns. While this concept shares some features with historical ideas like Maxwell’s luminiferous ether and Einstein’s “new ether,” it avoids their mechanical nature in favor of a pure field theory supporting frequency-dependent wave propagation.

This approach preserves physical realism while explaining quantum phenomena through actual wave processes rather than abstract mathematical constructs. The quantum ocean provides a concrete physical mechanism for wave function evolution and measurement, eliminating the need for mysterious collapse postulates or observer-dependent effects. Importantly, the framework maintains causality despite allowing superluminal wave propagation at finite speeds, resolving apparent tensions between quantum mechanics and relativity.

2. The Historical and Philosophical Context of Schrödinger’s Wave Ontology

The tension between particle and wave ontologies has deep roots in the history of physics, reflecting broader philosophical debates about the nature of continuity, discreteness, and physical law. While the ancient Greeks debated whether reality was fundamentally continuous (Heraclitus) or discrete (Democritus), modern physics has inherited this dialectic in increasingly sophisticated forms.

2.1. The Development of Field Theory

Maxwell’s unification of electricity and magnetism through field equations marked a crucial shift from Newtonian particle mechanics toward field-based physics. As Cao (2010) notes, this transition raised profound questions about the ontological status of fields—questions that would later resurface in quantum field theory. Maxwell’s achievement suggested that physical reality might be fundamentally continuous rather than particulate, though the notion of ether as a mechanical medium would later be considered problematic, before again being revived under different names such as spacetime, quantum ocean, etc.

2.2. Wave Mechanics and the Copenhagen Interpretation

Schrödinger’s 1926 introduction of wave mechanics represented both mathematical innovation and philosophical challenges (Schrödinger 1926). As Howard (2004) documents, Schrödinger’s realist interpretation of the wave equation faced immediate resistance from Bohr’s Copenhagen school, which advocated an instrumentalist approach emphasizing operational definitions over ontological claims—“shut up and calculate” became the short summary of this approach (Maudlin 2019). This methodological divide reflected deeper philosophical disagreements about the aims of physical theory and the nature of scientific understanding.

Einstein’s support for Schrödinger’s position stemmed not merely from personal preference for determinism but from methodological principles about physical theory. As Fine (1986) argues, Einstein’s famous assertion that “God does not play dice” reflected broader concerns about completeness and locality in physical theory. The EPR paper (Einstein et al., 1935) crystallized these concerns, suggesting that quantum mechanics’ inability to provide a complete, local description of reality indicated its provisional nature as a theory.

Schrödinger’s dissatisfaction with the Copenhagen interpretation (Cushing 1994) was rooted in his commitment to continuity and unity in physical reality. He viewed the wave function that he discovered not merely as a mathematical tool for probability calculations but as a real, physical entity that described continuous processes. Some key contemporaries, including Einstein, shared similar reservations about the particle-centric, probabilistic framework that came to dominate quantum mechanics as Bohr, Heisenberg, Born and Pauli’s Copenhagen school brooked no rivals.

Einstein’s critiques of quantum mechanics often centered on the lack of realism and completeness in its interpretations. Famously, Einstein described quantum entanglement as “spooky action at a distance” and sought a deterministic framework to replace the apparent randomness and non-locality of quantum mechanics.

Schrödinger’s wave mechanics and Einstein’s field theories, though developed independently, share a common philosophical commitment to describing nature as a unified, continuous system. David Bohm’s 1952 pilot-wave theory (with similarities to de Broglie’s earlier pilot wave work in the 1920s, though Bohm was not aware of this work until later) expanded on this commitment, introducing a deterministic framework for quantum phenomena. Bohm argued that “a particle follows a definite trajectory, determined by the wave, thus restoring causality and continuity to quantum processes” (Bohm 1952).

John Bell’s work further validated the importance of non-locality in any realistic interpretation of quantum mechanics. His theorem, proved out by many experiments after his death, suggested that no local hidden-variable theory could reproduce the predictions of quantum mechanics, providing crucial support for deterministic and wave-based frameworks. Bell remarked, “The concept of ‘particles’ … is derived, not fundamental. The real stuff of the world is fields, which evolve according to wave equations” (Bell 1987).

Another significant influence on wave-based approaches to physics comes from Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy. Writing in the 1920s as quantum mechanics was being developed, Whitehead proposed that reality consists fundamentally of processes rather than substances, and that what we perceive as particles are actually patterns of recurring events or “actual occasions.” In his 1925 book, Science and the Modern World, he stated: “Nature is a structure of evolving processes. The reality is the process.... The distinction between past, present, and future is not a mere succession of actual occasions; but it marks a real physical quality of nature.”

In Process and Reality (1929), he argued that the quantum world is better understood through the lens of continuous processes and waves rather than discrete particles. His notion that apparently stable objects are actually patterns of vibration in an underlying field-like reality presaged many aspects of quantum field theory and aligns closely with QOT’s perspective. Whitehead’s insight that there is no nature at an instant—that reality consists of continuous processes rather than static states—finds remarkable validation in QOT’s picture of particles as standing waves and forces as traveling waves in the quantum ocean.

As Epperson (2004) argues in Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, Whitehead’s process-based interpretation of quantum mechanics offers a more coherent philosophical foundation than the Copenhagen interpretation’s probabilistic approach. QOT can be seen in key ways as a mathematical and physical realization of Whitehead’s philosophical vision of reality as fundamentally wave-like and processual rather than particle-like and substantial.

The QOT framework draws from these intellectual traditions, combining the wave-based ontologies of Schrödinger, Einstein and Whitehead, with the determinism of Bohm and the non-locality insights of Bell to propose a unified theory rooted in the quantum ocean.

2.3. Modern Interpretations and Wave Ontology

Recent work in foundations of physics has increasingly recognized the limitations of Copenhagen orthodoxy. Maudlin (2019) argues that the measurement problem remains fundamentally unresolved, while Ladyman and Ross (2007) suggest that our ontological categories may need radical revision. These developments create space for reconsidering wave-based approaches.

Bell’s theorem, often interpreted as supporting Copenhagen-style quantum mechanics, actually provides crucial support for wave-based ontologies. As Shimony (1993) notes, Bell’s results require abandoning either locality or realism—but a wave-based theory that allows superluminal (though finite) wave propagation can maintain both while explaining quantum correlations.

2.4. Evaluation Considerations

The development of wave-based theories raises important methodological questions about the relationship between mathematics and physical reality. French (2014) argues that physical theories necessarily involve both mathematical structures and interpretive frameworks linking those structures to observable phenomena. This suggests evaluating wave-based approaches not merely on predictive success but also on their ability to provide coherent ontological foundations and explanations that make intuitive sense—as opposed to much of today’s and historical quantum interpretations that sometimes actively defied this approach.

The success of quantum field theory, despite its interpretational difficulties, hints at the strong potential for field-based approaches. As Cao (2010) argues, QFT’s treatment of particles as field excitations suggests reality may be fundamentally continuous rather than discrete. QOT aligns with Schrödinger’s monistic vision while raising new questions about emergence and reduction in physical theory.

3. Ontological and Mathematical Foundations of QOT

3.1. The Status of Physical Law

Before presenting QOT’s mathematical framework, we must address fundamental questions about the nature of physical law. Traditional approaches, following Wigner’s (1960) notion of the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics,” often treat mathematical structures as somehow prior to physical reality. QOT suggests an alternative: mathematical regularities emerge from the fundamental wave nature of reality rather than governing it externally.

This aligns with what Mumford (2004) calls a “dispositional essentialist” view of natural law, where laws describe the inherent tendencies of physical systems rather than imposing external constraints, and Whitehead’s work in which he describes the laws of nature as more akin to “the habits” of nature. In QOT, the wave equation isn’t merely a description but reflects the behavior of the quantum ocean as an oscillatory medium.

3.2. The Ontology of the Vacuum Ocean

The quantum ocean in QOT isn’t the passive background of quantum field theory but an active, oscillatory medium spanning an immense frequency spectrum. The quantum ocean has always existed and disturbances in this field are what lead, very occasionally, to universes of matter and energy. This reconception addresses what Cao (2010) identifies as a key problem in quantum field theory: the ontological status of vacuum states. Rather than treating vacuum fluctuations as mathematical artifacts, QOT posits them as fundamental features of reality, an energetic medium that manifests all of reality through different frequencies and wave patterns.

Key ontological principles include:

Fundamental Continuity: Reality consists of continuous wave phenomena, addressing longstanding debates about continuity versus discreteness in physics.

Oscillatory Coherence: The quantum ocean exhibits inherent tendencies toward organized wave patterns, suggesting a novel approach to emergence in physical systems.

Scale-Free Dynamics: Wave phenomena exhibit self-similar patterns across scales, raising important questions about reduction and emergence in physical theory.

3.3. Mathematical Framework

3.3.1. Unified Wave Equation

The dynamics of the quantum ocean are governed by a wave equation that unifies quantum and gravitational phenomena:

Each term has precise physical significance:

∇2Ψ represents spatial variation of waves in the quantum ocean. Physically, it tells us how wave amplitudes change across space.

The factor 1/vw2 scales the temporal evolution, where vw is the wave velocity in a given frequency domain.

∂2Ψ/∂t2 describes how waves change in time, capturing oscillatory behavior.

κ(∇·Φ)eiθ represents field coupling through polarization. The factor eiθ enables complex phase relationships crucial for electromagnetic phenomena.

λ(∂μJμ) ensures conservation of energy-momentum.

The equation’s form combines features of known wave equations while introducing terms necessary for force emergence:

It reduces to the classical wave equation when coupling terms are negligible

At electromagnetic frequencies, it yields Maxwell’s equations

In the quantum domain, it reduces to Schrödinger’s equation

The dimensional consistency of each term is crucial:

∇2Ψ: [L−2] Spatial variation per unit area

1/vw2: [T2/L2] Time squared per length squared

∂2Ψ/∂t2: [T−2] Rate of change of rate of change

κ(∇·Φ): [L−2] Field coupling per unit area

λ(∂μJμ): [L−2]Energy-momentum conservation per unit area

The quantum ocean’s response to oscillations varies systematically with frequency, leading to distinct force behaviors. The wave velocity-frequency relationship emerges from the dispersion relation of Equation (1):

For waves in the quantum ocean, this yields the characteristic relationship:

where k

1 = 3.2 and k

2 = 19.8 are determined from empirically observed force behaviors. This logarithmic relationship isn’t arbitrary but reflects how waves interact with the quantum ocean’s structure:

At low frequencies (1015-1020 Hz), waves encounter minimal resistance, achieving maximum velocity (~1500c) − the nu force domain.

In intermediate frequencies (1020-1024 Hz), moderate interaction yields gravitational waves at ~3c.

At electromagnetic frequencies (1024-1030 Hz), resonant interactions fix the wave speed at exactly c.

The association of specific frequency bands with different forces isn’t arbitrary but follows from the wave equation’s natural resonance patterns. The quantum ocean’s oscillatory properties establish preferred frequency domains where specific wave patterns become stable, manifesting as the distinct forces we observe.

3.3.2. Emergence of Maxwell’s Equations

At electromagnetic frequencies (1024-1030 Hz), wave patterns in the quantum ocean naturally separate into perpendicular components. This separation isn’t imposed but emerges from conservation principles and energy minimization:

When Ψ = E + iB, substituting into our fundamental equation:

- 2.

Phase Evolution

The phase factor e

iθ evolves according to:

This evolution constrains the relationship between E and B fields:

- 3.

Emergence of Curl Terms

The proportionality relations combine with conservation of angular momentum to yield:

The curl terms emerge because:

Angular momentum conservation requires perpendicular field components

Phase relationships fix their relative orientation

Energy conservation determines their coupling strength

The conservation term λ(∂

μJ

μ) in our fundamental equation yields the divergence relations:

These emerge because:

Charge conservation requires ∇·E proportional to charge density

The absence of magnetic monopoles requires ∇·B = 0

The constants ε0 and μ0 reflect the quantum ocean’s electromagnetic response

Combining the curl and divergence equations yields the electromagnetic wave equations:

These describe electromagnetic waves propagating at velocity c in the quantum ocean, where:

Wave speed c emerges naturally from the medium’s properties

Perpendicular E and B fields maintain fixed phase relationships

Energy oscillates between electric and magnetic components

This derivation shows how the full structure of classical electromagnetism emerges from quantum ocean dynamics through:

Natural symmetry breaking at electromagnetic frequencies

Conservation principles enforcing field relationships

Phase evolution determining coupling strengths

Wave propagation at characteristic velocity c

3.3.3. Pattern of Force Emergence Across Frequency Domains

The emergence of electromagnetic phenomena at 1024-1030 Hz exemplifies a general principle: distinct forces arise from the quantum ocean’s frequency-dependent response to oscillations.

Let’s examine this pattern systematically:

Nu Force Domain (1015-1020 Hz)

Minimal coupling: κ(∇·Φ) → 0

Wave equation simplifies to: ∇2Ψ = (1/vnu2)∂2Ψ/∂t2

Maximum propagation speed (~1500c) due to minimal medium interaction

No symmetry breaking, enabling long-range quantum correlations

Gravitational Domain (1020-1024 Hz)

Weak coupling: small κg value

Wave equation: ∇2Ψ = (1/vg2)[∂2Ψ/∂t2 + κg(∇·Φ)]

Intermediate propagation speed (~3c)

Universal attraction through constructive wave interference

Electromagnetic Domain (1024-1030 Hz)

Strong coupling: optimal κ value for field separation

Full wave equation with perpendicular field components

Speed c emerges from resonant medium interaction

Bidirectional forces through phase relationships

This progression reveals how forces emerge naturally from the quantum ocean’s wave dynamics rather than being imposed externally. The frequency bands aren’t arbitrary but reflect the medium’s intrinsic resonant properties, with propagation speeds determined by wave-medium interaction strength.

Nuclear Force Domains

As frequencies increase beyond the electromagnetic domain, wave-medium interactions intensify, leading to distinct nuclear force characteristics:

Weak Nuclear Force (1030-1035 Hz)

Strong coupling: large κwf value

Wave equation: ∇2Ψ = (1/vwf2)[∂2Ψ/∂t2 + κwf (∇·Φ)eiθ + λwf(∂μJμ)]

Propagation speed drops below c

Short range due to intense wave-medium interaction

Chiral symmetry breaking emerges naturally from phase evolution

Explains weak force’s parity violation and flavor changes

Strong Nuclear Force (>1035 Hz)

Maximum coupling: very large κs value

Wave equation: ∇2Ψ = (1/vs2)[∂2Ψ/∂t2 + κs(∇·Φ)eiθ + λs(∂μJμ)]

Minimum propagation speed

Extreme localization creates color confinement

Three-fold symmetry produces color charge states

Explains quark confinement through wave trapping

This completes the unified picture of force emergence through frequency-dependent wave dynamics in the quantum ocean. Each force represents a different regime of wave-medium interaction, with distinct properties emerging naturally from the fundamental wave equation.

3.3.4. Unified Framework of Force Emergence

The emergence of five distinct forces from a single wave equation in the quantum ocean reveals a unity underlying physical phenomena. As frequency increases, we observe a systematic progression of frequency-dependent wave dynamics:

Nu Force (1015-1020 Hz): Maximum velocity, minimal interaction

Gravitational (1020-1024 Hz): Intermediate velocity, weak coupling

Electromagnetic (1024-1030 Hz): Light speed, optimal coupling

Weak Nuclear (1030-1035 Hz): Sub-light speed, strong coupling

Strong Nuclear (>1035 Hz): Minimum velocity, maximum coupling

This progression reflects fundamental principles:

Higher frequencies interact more strongly with the quantum ocean

Stronger interactions reduce propagation speed

Each force emerges from natural resonances in specific frequency bands

Force characteristics (range, strength, symmetries) follow directly from wave-medium interactions

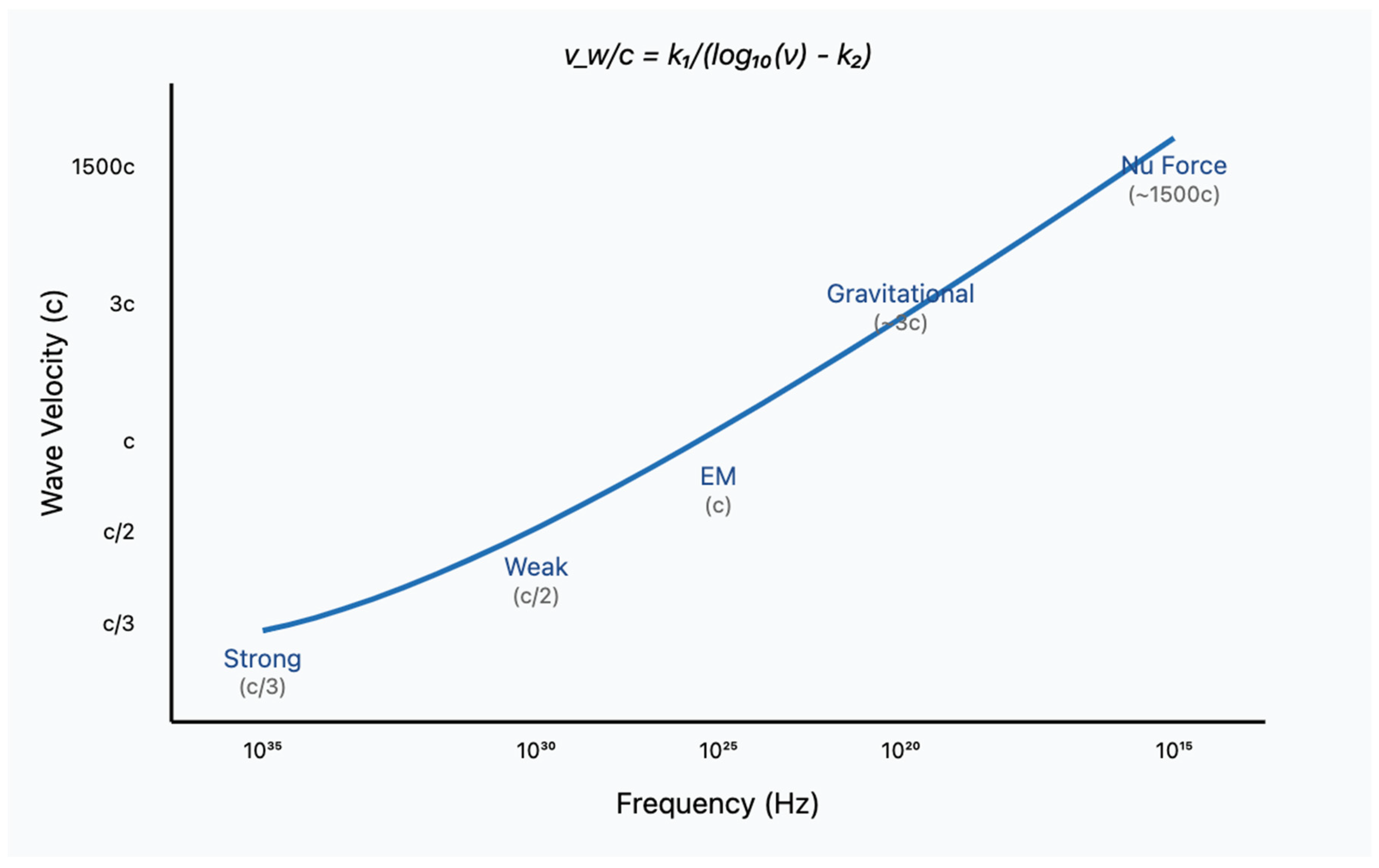

The velocity-frequency relationship: vw/c = k1/(log10(ν) − k2)

unifies all forces through a single mathematical description, with each force representing a different manifestation of the same underlying wave dynamics.

This mathematical framework demonstrates how QOT unifies diverse physical phenomena through a single wave equation while maintaining rigorous consistency with established physics.

3.3.5. Reduction to Schrödinger’s Equation

QOT’s wave equation shares much philosophically with Schrödinger’s wave equation, but the mathematics is significantly different. The transformation to Schrödinger’s equation occurs through separation of fast and slow time scales.

Writing Ψ = ψe

-iωt and averaging over fast oscillations yields:

The velocity-frequency relationship emerges from the dispersion relation of Eq.(1):

For waves in the quantum ocean, this yields:

where k

1 = 3.2 and k

2 = 19.8 are determined from:

Quantum correlations (1500c at 1015-1020 Hz)

Gravitational effects (3c at 1020-1024 Hz)

Electromagnetic waves (c at 1024-1030 Hz)

While Schrödinger’s 1926 wave equation describes quantum states through a complex-valued wavefunction, it was primarily developed as a mathematical tool for calculating probabilities rather than representing physical waves. His equation—iℏ∂ψ/∂t = -ℏ2/2m∇2ψ + Vψ—describes how quantum states evolve in time but doesn’t explain what’s actually “waving.”

QOT’s Equation 1, in contrast, describes real physical waves in the quantum ocean, energy waves that oscillate in various frequency domains and thus produce the different forces of nature. Our equation is more general, reducing to Schrödinger’s equation in the quantum domain but also describing wave phenomena across all frequency ranges. The term vw represents actual wave velocities in different frequency domains, unlike Schrödinger’s equation which assumes a fixed light speed c for all forces. The polarization term Φ and phase factor eiθ describe how waves in the quantum ocean can form stable patterns (particles) or propagate as forces, while the conservation term λ(∂μJμ) ensures physical quantities like energy and momentum are preserved.

Our equation reduces to Schrödinger’s in the quantum domain but extends beyond it to describe wave phenomena across all frequency ranges and forces. The polarization term enables both particle-like and wave-like behavior to emerge naturally from the same equation, while the conservation term ensures consistency with known physics. Most importantly, our equation describes actual physical waves in a real medium rather than abstract probability waves. This fulfills Schrödinger’s original dream of describing quantum phenomena through real physical waves while extending to all forces and scales.

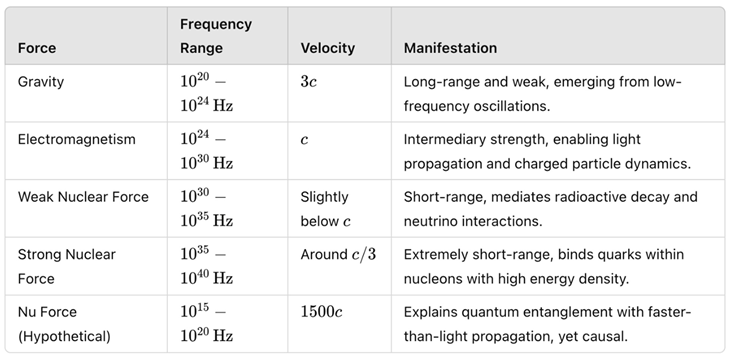

Table 1.

Summary of the five forces in QOT.

Table 1.

Summary of the five forces in QOT.

Each force arises from oscillatory modes in the vacuum, with its distinct frequency band dictating its velocity and interaction range.

Figure 1 shows the smooth logarithmic curve connecting each force’s velocity, based on its frequency range. See Appendix 1 for more details on how all forces arise from the wave equation.

An important precursor to QOT is Larry Reed’s wave mechanics framework (2022), which reconceptualizes gravity and electromagnetism as wave phenomena in a dynamic vacuum medium. Reed describes how gravitational effects emerge from constructive wave interference while electromagnetic phenomena arise through vacuum polarization. His detailed treatment of wave propagation in the quantum ocean and his emphasis on frequency domains provided key inspiration for QOT’s broader unification project. While Reed focuses primarily on gravity and electromagnetism, QOT extends this wave-based approach to all forces, introducing the concept of the “nu force” to explain quantum entanglement and developing a single wave equation that encompasses all force domains. Reed’s insight that forces can be understood through wave mechanics in different frequency domains is fundamental to QOT’s unified framework.

3.4. The Status of Physical Constants

QOT suggests a novel perspective on physical constants, aligning with Brown’s (2005) argument that constants should be explained rather than merely assumed. The framework derives constants like c (light speed) from quantum ocean properties rather than treating them as fundamental.

The relationship between frequency and propagation speed follows a natural logarithmic form: vw/c = k1/(log10(ν) − k2)

This suggests physical constants might vary slightly in regions where quantum ocean properties differ, raising important questions about the universality of physical law.

4. Resolving Foundational Issues in Quantum Theory

One of the most perplexing aspects of quantum mechanics has been the apparent wave-particle duality of matter and light. For nearly a century, physicists have grappled with how something can be both a wave and a particle. The famous double-slit experiment seems to suggest that individual particles somehow go through both slits at once, interfering with themselves like waves—but only when we’re not looking. This paradox disappears in the quantum ocean framework.

What we call particles are actually standing waves in the quantum ocean—like steady vibrations on a drum head. When these waves encounter the two slits, they spread out and interfere just as water waves would when passing through two openings in a barrier. The interference pattern we observe isn’t mysterious; it’s exactly what we should expect from waves. When we detect individual “particles,” we’re actually seeing these waves interact with our measuring devices (themselves made of standing waves) to form new localized wave patterns. No mysterious collapse or observer effect is needed—it’s all just waves interacting with waves.

Quantum entanglement has been equally puzzling. Einstein called it “spooky action at a distance” because changes to one particle seemed to instantly affect its entangled partner, no matter how far apart they were. This apparent faster-than-light influence troubled Einstein deeply. But in the quantum ocean framework, entanglement isn’t spooky at all. It’s maintained by what we call the “nu force”—waves in the quantum ocean that travel about 1,500 times faster than light. While this is incredibly fast, it’s still finite, preserving causality. No instantaneous action is required.

When particles become entangled, they’re connected by these faster-than-light nu force waves. Changes to one particle propagate to its partner extremely quickly—but not instantaneously. This explains the correlations we observe in Bell test experiments while maintaining Einstein’s insistence on realism and causality. The “spooky action” isn’t spooky anymore; it’s just very fast wave propagation.

The measurement problem in quantum mechanics has also resisted satisfactory explanation. The standard Copenhagen interpretation suggests that measurement somehow causes the quantum wave function to “collapse” into a definite state, but only when an observer is involved. This mysterious collapse has never been observed directly, and the special role of observers seems philosophically problematic.

In the quantum ocean framework, measurement is simply what happens when quantum waves interact with measuring devices. There’s no collapse and no special role for observers. When we measure a quantum system, we’re seeing the resonant interaction of its waves with the standing waves that make up our measuring apparatus. The apparent “collapse” is just the formation of new standing wave patterns through natural wave interactions. This process is deterministic but practically irreversible—much like dropping a stone in a pond creates waves that can’t easily be put back together to recreate the original splash.

The probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, which seemed to Einstein to indicate its incompleteness (“God does not play dice”), also finds natural explanation in the quantum ocean framework. The complex interactions of countless waves in the quantum ocean give rise to probability distributions that match quantum mechanical predictions exactly. But these probabilities emerge from deterministic wave dynamics—there’s no fundamental randomness involved. This resolves the apparent conflict between quantum probabilities and physical realism that troubled Einstein and Schrödinger.

Finally, the framework eliminates the mysterious boundary between quantum and classical behavior. In traditional quantum mechanics, there’s an unclear transition between the quantum world of superpositions and the classical world of definite properties. The quantum ocean framework describes everything—from subatomic particles to macroscopic objects—as wave patterns in the same medium. The apparent emergence of classical behavior from quantum systems results from the progressive interaction of waves at different scales. There’s no sharp boundary, just a smooth transition from one regime to another.

In essence, the quantum ocean framework achieves what Einstein and Schrödinger sought: a continuous, deterministic theory that accounts for quantum phenomena without sacrificing physical reality or introducing observer-dependent effects. It resolves quantum paradoxes not by adding new mathematical machinery but by returning to the simple idea that everything—particles, forces, and even spacetime itself—consists of waves in a single underlying medium.

5. Philosophical Implications

The quantum ocean framework suggests a profound shift in how we understand physical reality. Rather than a world built from discrete particles interacting through various forces, we find a continuous ocean of waves from which both particles and forces emerge naturally. This vision aligns closely with what Schrödinger and Einstein sought—a unified, realistic description of nature that maintains continuity and causality while explaining quantum phenomena.

At its heart, the framework embraces monism—the idea that reality consists of a single kind of thing. In this case, that fundamental reality is waves in the quantum ocean. Everything we observe, from electrons to galaxies, emerges from patterns in this oscillatory medium. This radical simplification of ontology—explaining many phenomena from a single principle—exemplifies Occam’s Razor, the principle that simpler explanations are preferable to complex ones.

This return to monism has deep philosophical roots. The ancient Greeks debated whether reality was fundamentally continuous or discrete, with Heraclitus arguing for continuous flux while Democritus advocated for indivisible atoms. The quantum ocean framework suggests a resolution: while reality appears particulate at certain scales, this discreteness emerges from underlying continuous wave phenomena. The apparent conflict between continuity and discreteness dissolves.

The framework also restores a stronger form of realism to physics than the Copenhagen interpretation allows. The quantum world isn’t fundamentally probabilistic or observer-dependent; it follows deterministic wave dynamics. Probability enters not as a fundamental feature of reality but as a practical necessity when dealing with complex wave interactions. This aligns with Einstein’s famous assertion that “God does not play dice with the universe.”

Causality also finds firmer footing in the quantum ocean framework. While quantum entanglement involves faster-than-light influences through the nu force, these influences propagate at finite (though very high) speeds. This preserves causality while explaining quantum correlations, resolving the tension between quantum mechanics and special relativity that troubled Einstein.

The framework suggests interesting implications for the nature of time and space. Rather than being fundamental aspects of reality, spacetime emerges from the dynamics of the quantum ocean. The speed of light, rather than being a universal constant, emerges as the characteristic propagation speed of electromagnetic waves in the quantum ocean. Different forces propagate at different speeds because they represent waves of different frequencies.

Questions of free will and determinism also take on new dimensions in this framework. While the underlying wave dynamics are deterministic, they’re so complex that perfect prediction becomes impossible in practice. This suggests a kind of “soft” determinism that preserves causality while allowing for effective freedom at higher levels of organization.

The framework also offers fresh perspective on the relationship between mind and matter. If all physical phenomena emerge from waves in the quantum ocean, consciousness too might be understood in terms of wave dynamics and coherence. This hints at potential connections between physics and consciousness that respect both the physicality of mind and its distinctive features.

Perhaps most profoundly, the quantum ocean framework suggests a kind of “panexperientialism”—the idea that experience or proto-experience exists throughout nature. If reality consists fundamentally of oscillatory patterns, then every physical system, from particles to planets, represents a kind of organized experience (Hunt and Schooler 2019 offers a congruent approach to understanding consciousness, General Resonance Theory), albeit highly fleeting compared to mammalian or human consciousness. This doesn’t mean that all systems are conscious in a way like humans are, but it suggests that consciousness exists on a spectrum of organized wave patterns, with EM field binding being the primary mechanism for the arising of complex consciousness.

In returning physics to a wave-based ontology, we find ourselves revisiting ancient philosophical questions with new tools and insights. The quantum ocean framework suggests that reality is both simpler and richer than we imagined—simpler in its fundamental nature as an oscillatory medium, but richer in the endless patterns and possibilities that this medium supports. Schrödinger’s dream of a purely wave-based physics may lead us not just to better physical theories, but to deeper philosophical understanding as well.

6. Physical Implications in Quantum Theory and Cosmology

Quantum Foundations

The quantum ocean framework sheds new light on several enduring puzzles in quantum mechanics. Consider the famous Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment. In traditional quantum mechanics, the cat is supposedly both alive and dead until observed. In the quantum ocean framework, there’s no mysterious superposition or collapse—just continuous wave evolution. The quantum trigger, the cat, and the measurement apparatus are all wave patterns interacting in predictable ways. The apparent quantum-to-classical transition happens smoothly through wave interactions, with no arbitrary cut between quantum and classical realms.

Similarly, quantum tunneling—where particles appear to pass through energy barriers—becomes more intuitive. Rather than a particle mysteriously appearing on the other side of a barrier, we have waves diffracting and interfering in ways that concentrate energy beyond the barrier. This is analogous to how ocean waves can sometimes appear to pass through breakwaters.

The Hubble Tension

Modern cosmology faces a crisis in measuring the universe’s expansion rate. Different methods give incompatible results—the so-called Hubble tension, which some cosmologists are now viewing as a crisis in the Standard Model (see, e.g., Scolnic et al. 2025). The quantum ocean framework suggests this tension may arise from misinterpreting the physical basis for redshift. Rather than indicating the expansion of space itself, QOT suggests that redshift might result from light waves gradually losing energy through interaction with the quantum ocean—a kind of cosmic friction effect. This mechanism, a kind of “tired light” approach, preserves the successes of standard cosmology while potentially resolving the Hubble tension.

Galactic Dynamics and Dark Matter

Recent observations have revealed unexpected synchronization between galaxies separated by vast distances—phenomena difficult to explain under standard physics (Lee et al. 2019). The quantum ocean framework predicts such correlations through shared origins in the same galactic neighborhood, followed by “galactic wandering” over vast periods of time. Such synchronized galaxies may also maintain gravitational influence through the superluminal (~3c) velocity of gravity in QOT.

This faster-than-light gravity might also explain galactic rotation curves without invoking dark matter. The framework suggests that gravity’s behavior at galactic scales emerges from low-frequency wave dynamics in the quantum ocean, potentially reproducing MOND-like (Modified Newtonian Dynamics) effects naturally.

Quantum Gravity and Black Holes

The framework offers a new perspective on quantum gravity—the long-sought unification of quantum mechanics and gravity. Rather than trying to quantize gravity directly, QOT suggests both quantum effects and gravity emerge from the same underlying wave dynamics at different frequencies. This unification happens automatically, without the infinities that plague other approaches to quantum gravity.

Black holes also appear different in the quantum ocean framework. Rather than containing singularities where physics breaks down, black holes represent regions of extreme wave coherence in the quantum ocean. Information isn’t truly lost but becomes encoded in complex wave patterns. These patterns can gradually “leak” through Hawking radiation, preserving information while explaining black hole thermodynamics.

Dark Energy and Cosmic Expansion

The quantum ocean framework suggests an alternative to dark energy for explaining cosmic acceleration. Rather than space itself expanding, the framework proposes that wave interactions in the quantum ocean create the appearance of acceleration. This could explain cosmic acceleration without invoking a mysterious dark energy that makes up most of the universe’s energy content.

Time and Causality

The framework maintains strict causality despite allowing faster-than-light wave propagation in certain frequency domains. The nu force’s speed of ~1500c explains quantum entanglement while still being finite, preserving cause-and-effect relationships. Similarly, gravitational waves at ~3c explain galaxy correlations while maintaining causality. This shows how apparent faster-than-light effects can be reconciled with relativistic causality through the quantum ocean’s wave mechanics.

Emergence of Physical Constants

Perhaps most intriguingly, the framework suggests that physical “constants” like the speed of light emerge from the quantum ocean’s properties rather than being fundamental. Their values reflect characteristic wave propagation speeds in different frequency domains. This raises the possibility that these constants might vary slightly in regions where the quantum ocean’s properties differ, potentially explaining certain cosmological anomalies.

These implications paint a picture of a universe more coherent and interconnected than previously imagined. Wave patterns in the quantum ocean maintain correlations across vast distances and timescales, while giving rise to the rich structure we observe from quantum to cosmic scales. This unified perspective offers solutions to numerous current puzzles in physics while suggesting new avenues for theoretical and observational investigation.

7. Technological Implications

The quantum ocean framework suggests several intriguing technological possibilities, though we must be careful to distinguish between near-term applications and more speculative long-term possibilities. Understanding matter and forces as wave phenomena in the quantum ocean opens new approaches to energy, propulsion, and field manipulation. These ideas remain untested but the implications discussed below follow naturally from the new understanding of forces in the QOT framework.

Energy Applications

One of the most promising near-term applications involves energy generation through controlled quantum ocean wave interactions. Just as ocean waves can drive turbines, organized wave patterns in the quantum ocean might be harnessed for energy production. The framework suggests specific frequency domains and resonance conditions where such energy extraction might be most efficient.

For example, high-frequency electromagnetic fields could potentially be manipulated to create localized regions of wave coherence, similar to how noise-canceling headphones work but operating at much higher frequencies. These coherent regions might enable more efficient energy transfer or storage. The mathematics of QOT provides specific guidance on optimal frequencies and configurations for such devices.

Field Manipulation and Propulsion

The framework’s understanding of gravity as low-frequency waves in the quantum ocean suggests new approaches to field manipulation. Controlled modification of local gravitational fields might be possible through carefully tuned wave interactions. The mathematics predicts that interference patterns at specific frequencies could create regions of slightly modified gravitational effects.

Such field manipulation might enable new propulsion technologies that don’t rely on reaction mass. By creating controlled wave patterns in the quantum ocean, it might be possible to generate directional forces through wave interference effects. While the energy requirements would likely be substantial, the approach offers a potential path to space propulsion without carrying large amounts of fuel.

This kind of field manipulation remains highly speculative at this time, but the QOT framework allows for such technological development through breakthroughs in our understanding of how forces are generated and interact with each other.

Quantum Coherence Technologies

Understanding quantum effects as wave phenomena in specific frequency domains suggests new approaches to quantum computing and communication. Rather than trying to maintain fragile quantum states, we might work with the natural coherence properties of the quantum ocean. The nu force domain, in particular, might offer new possibilities for quantum information processing that are more robust against decoherence.

The framework predicts that quantum entanglement, mediated by nu force waves, could potentially be controlled more precisely than current approaches allow. This might enable more reliable quantum communication channels or new types of quantum sensors that exploit quantum ocean wave dynamics.

Material Science Applications

The wave-based understanding of matter suggests new approaches to materials engineering. By thinking of materials as organized standing wave patterns, we might find ways to create new types of metamaterials with properties designed through wave interference effects. The framework provides specific guidance on how different frequency domains interact, potentially enabling materials that respond in novel ways to electromagnetic or gravitational fields.

Fusion Energy Possibilities

Nuclear fusion might be approached differently when understood through quantum ocean dynamics. Rather than trying to confine plasma through brute force, we might use wave interference patterns to create more stable containment. The framework’s understanding of nuclear forces as high-frequency quantum ocean waves suggests specific frequencies and configurations that might enhance fusion efficiency.

Near-Term Applications

More immediate applications might come from using the framework’s insights to improve existing technologies. Better understanding of wave coherence could enhance quantum computing designs. Insights into electromagnetic wave propagation might improve antenna designs or lead to more efficient energy transmission systems. The framework’s predictions about wave interactions could guide the development of new materials or sensor systems.

The technological implications of QOT suggest exciting possibilities while demanding careful, systematic development. By understanding the universe as an interconnected wave medium, we might eventually develop technologies that seem like science fiction today. However, progress will require patient research, rigorous testing, and careful attention to safety and practical limitations. The framework provides a roadmap for this development, grounded in solid physics while pointing toward revolutionary possibilities.

8. Testing QOT

Any new theoretical framework must make testable predictions that differ from existing theories. The quantum ocean framework suggests several experimental tests ranging from tabletop laboratory experiments to astronomical observations. Here we explore some of the most promising ways to test the theory’s predictions.

The Grain of Sand Experiment

Perhaps the most striking near-term test would involve trying to create a small anti-gravity effect through wave interference. The experiment would attempt to levitate a single grain of sand by about one centimeter using carefully tuned wave generators. While simple in concept, this experiment would provide a crucial test of QOT’s predictions about gravity as a wave phenomenon.

The setup would include:

A single grain of sand weighing about 10-6 kg

Wave generators operating in the gravitational frequency range (1020-1024 Hz)

High-precision position sensors

A vacuum chamber to minimize environmental interference

Thermal isolation systems

The experiment would generate phase-inverted wave patterns matched to gravitational frequencies, focusing these waves on the test mass using resonant wave guides. If successful, we should observe a measurable displacement of the test mass correlating with the applied wave patterns. The energy requirements would be modest since we’re working with such a small mass, making this a practical laboratory test.

Success would provide dramatic evidence for QOT’s wave-based interpretation of gravity. Failure would suggest either technical limitations in our ability to generate the required wave patterns or potentially falsify this aspect of the theory.

Astronomical Tests

The framework makes several predictions about astronomical phenomena that can be tested with existing and near-future telescopes:

The galactic synchrony patterns discovered by Lee et al. (2019) provide a natural test bed. QOT predicts that regions showing synchrony today should trace to past proximity beyond the standard model’s 13.8-billion-year limit. By mapping galactic velocities and trajectories, we can identify regions where galaxies would have been neighbors more than 13.8 billion years ago and test whether these regions show higher degrees of rotational synchrony.

The James Webb Space Telescope can also test QOT’s predictions about ancient galaxies. The framework predicts that galaxies at high redshift should show signs of extended evolution incompatible with standard cosmological timelines. Recent observations of surprisingly mature early galaxies may already support this prediction.

Quantum Experiments

Several quantum mechanical predictions of QOT could be tested in laboratory settings:

The framework predicts specific coherence patterns and transitions between force behaviors at particular frequency domains. High-precision measurements could detect these transitions.

Quantum entanglement experiments could test the prediction that correlations propagate at finite but superluminal speeds (~1500c) through nu force waves.

New types of interference experiments could test QOT’s predictions about wave interaction patterns across different frequency domains.

Nuclear Scale Tests

At nuclear scales, QOT makes specific predictions about how strong and weak nuclear forces emerge from high-frequency quantum ocean waves. These could be tested through:

Precise measurements of nuclear decay rates under controlled wave interference conditions

Studies of particle interaction patterns in accelerators

New types of detectors designed to measure wave patterns in nuclear frequency domains

Challenges in Testing

Several challenges complicate testing QOT:

Many predicted effects require precise control of high-frequency waves beyond current technical capabilities.

Environmental noise can mask subtle wave interference patterns.

Some predictions involve scales (both very large and very small) that are difficult to observe directly.

The framework suggests that our measuring devices themselves consist of wave patterns, which must be accounted for in experimental design.

Future Prospects

As technology improves, new testing opportunities will emerge:

Advanced gravitational wave detectors might detect wave patterns predicted by QOT.

Improved quantum sensors could probe quantum ocean wave dynamics more directly.

New space-based telescopes could provide better data on galactic evolution and cosmic structure.

Advanced particle accelerators could test predictions about nuclear force emergence.

Advanced particle accelerators could test predictions about nuclear force emergence.

The key to testing QOT lies in designing experiments that can distinguish its predictions from those of standard theories while remaining within current or near-future technical capabilities. The framework’s unified wave-based approach suggests numerous potential tests across different domains of physics, from quantum to cosmic scales. Success in any of these tests would provide strong support for the theory, while failures would help refine or potentially falsify aspects of the framework.

9. Conclusions

The Quantum Ocean Theory framework imagines what Schrödinger’s project might have become had he pursued his wave-based ontology further. By treating the quantum ocean as an oscillatory medium, QOT unifies fundamental forces and particles under a single framework while resolving persistent conceptual challenges in quantum mechanics. This approach not only honors Schrödinger’s philosophical commitments but also builds on Einstein’s quest for a unified field theory, Whitehead’s process philosophy, and the non-locality insights of Bohm and Bell. Together, these perspectives converge into a coherent vision of reality where “all is waves.”

References

- Baggen, J.F.W.; van Dokkum, P.; Labbé, I.; et al. Resolved Rest-frame UV Sizes of the Red Objects at. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2023, 955, L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox. Physics Physique Физика 1964, 1(3), 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, D. A Suggested Interpretation of Quantum Theory in Terms of ‘Hidden’ Variables. Physical Review 1952, 85(2), 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.R. Physical Relativity: Space-time Structure from a Dynamical Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, T.Y. From Current Algebra to Quantum Chromodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, J.T. Quantum Mechanics: Historical Contingency and the Copenhagen Hegemony; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. The New Ether. Zeitschrift für Physik 1930, 60, 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Physical Review 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epperson, M. Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead; Fordham University Press: New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, A. The Shaky Game: Einstein, Realism and the Quantum Theory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- French, S. The Structure of the World: Metaphysics and Representation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, D. Who Invented the Copenhagen Interpretation? A Study in Mythology. Philosophy of Science 2004, 71, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T.; Schooler, J.W. The Easy Part of the Hard Problem: A Resonance Theory of Consciousness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2019, 13, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladyman, J.; Ross, D. Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; et al. The Mysteriously High Fraction of Systems with Both Clockwise and Counter-clockwise Angular Momenta. The Astrophysical Journal 2019, 883, L29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudlin, T. Philosophy of Physics: Quantum Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.C. A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Mermin, N.D. What’s Wrong with This Pillow? Physics Today 1989, 42(4), 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W. Schrödinger: Life and Thought; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, S. Laws in Nature; Routledge: London, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, L.J. Quantum Wave Mechanics, 4th ed.; Booklocker: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Annalen der Physik 1926, 384(4), 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.; et al. The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2025, 979, L9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony, A. Search for a Naturalistic World View; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Leja, J.; et al. RUBIES: Evolved Stellar Populations with Extended Formation Histories at z ~ 7-8 in Candidate Massive Galaxies Identified with JWST/NIRSpec. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2024, 969, L13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

27.Whitehead, A.N. Science and the Modern World; Macmillan: New York, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A.N. Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology; Macmillan: New York, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Wigner, E.P. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 1960, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).