1. Introduction

Nowadays, besides advanced issues, base questions of quantum mechanics (QM) continue to be the subject of lively debates within the scientific community [

1]. The

wave-particle duality, the

measurement problem, wave collapse, quantum realism and the

correspondence principle raise a complex web of queries [

2,

3]. Over a dozen quantum theories have been proposed but they do not provide entirely satisfactory answers [

4,

5]. Some explanations seem rather bizarre if not downright fantastic, they bewilder scholars to the point that the preferred quantum interpretation depends on personal opinions rather than the successful support of experiments [

6]. This intellectual situation turns out to be so troublesome as one could ask the reasons for it, why it persists decades later despite the contributions of eminent scholars.

It is reasonable to suspect that some methodological mistakes stand in the way of quantum theorists. If this suspicion has ground, theorists should not directly attack the issues mentioned above, but should first argue the prerequisites of the investigations, the right way forward, the mathematical tools to use and other elements supporting theoretical research. Quantum scientists should ask:

Are the entities we wish to study clear? Is the probability calculus adequate for QM?

In 1900 Max Planck, assuming that energy can be released in discrete packets, solved the problem of the black body [

7]. The current work can but share the

quantization principle which formalizes quanta as elements characterized by multiples of a base value:

{1} – The quantum ξ is a discrete portion of energy and possibly matter.

Einstein [

8] investigated the statistical fluctuations of energy of the black body and the variance adds two values:

The term

refers to the fluctuations of a group of independent particles, and

corresponds to the fluctuations of classical waves in a cavity. The radiation mechanism of the black body exhibits both particle and wave aspects [

9] and the following principle holds:

{2} –

The quantum ξ behaves either as a wave or as a particle.

Physicists manage

{1} without great difficulties while the states of

{2} constitute an ongoing conundrum. Researchers have proposed an assortment of solutions, for some the particles are vibrating strings; for others the particles are an irreducible representation of the Poincaré group. The majority interprets the squared modulus of the wavefunction |Ψ|

2 as the probability density of measuring a particle as being at a given place [

10,

11]. However, all the proposals are not perfectly satisfactory, for example despite the numerous fields that take advantage of the wavefunction, scientists dispute whether Ψ is real or abstract formalism, how it carries energy, whether it collapses or not etc. The questions about quantum waves and particles are so numerous and profound that it is natural to wonder whether the scientific community has followed the correct research method so far.

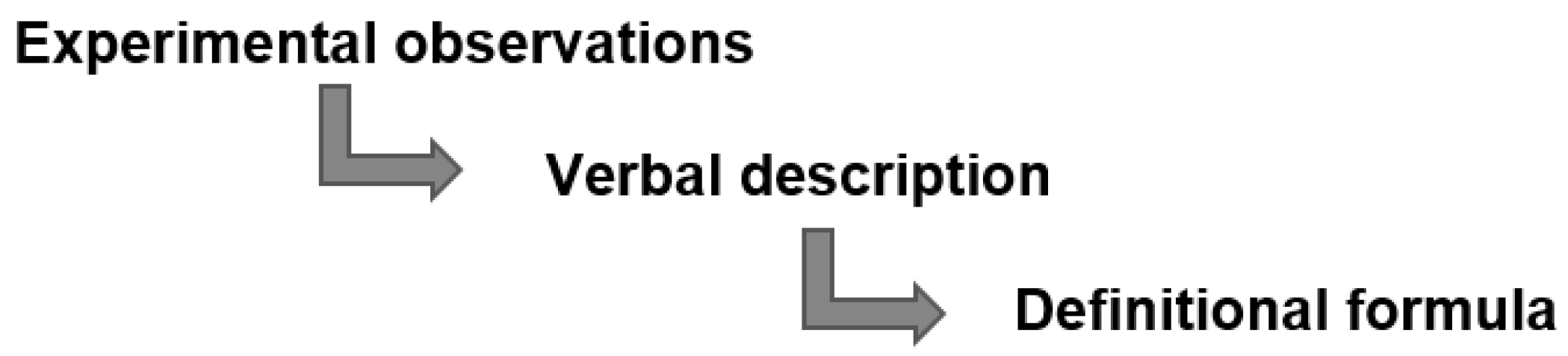

When physicists discover a new entity, they arrange several experiments; they describe the elements under scrutiny and finally translate the shared understanding into mathematical language (

Figure 1). Scientists arrive to the

definitional formula (DF) of the entity

Z which has the special capability of describing the intrinsic nature of

Z.

The computational formulas (CFs) of Z prove to be very useful, they describe significant aspects of Z or provide further insights, but do not state the basic qualities of Z. Both DF and CF provide effective aid to scientists in applied problems, but only DF explicates the essence of Z and ensures our understanding of Z. For example, various equations calculate the electric current I, but only dQ/dt makes explicit the nature of I that is the electric charge rate flowing through a conductor.

The

Schrödinger equation establishes a criterion symmetrical to the classical criterion of energy conservation [

12]. The solution to the

time independent form of the equation describes standing waves, while the

time dependent equation describes progressive waves:

The

position wavefunction Ψ(

x,t) supplies the solution to the Schrödinger equation in spatial space, and the

momentum wavefunction Φ(

p,t) in momentum space:

The two versions have precise mutual relationships:

This is just to highlight how the wavefunctions do not come from experimental observations but from calculus, thus they are computational formulas. Due to this reason, they do not explain the nature of waves and particles and the long-standing discussion about Ψ(x,t) corroborates the present conclusions. As a consequence, particles and waves should be precisely formulated on the basis of experiments, observations and this methodological rule cannot be bypassed in any way.

2. A Complex Cultural Landscape

Most authors share the idea that quantum physics is intrinsically involved with indeterminism but they are prone to downplaying difficulties. They hold the probability calculus basically is functioning and deem the divisions amongst the probabilists are no more than philosophical quarrels rather apart from physics. Instead, things are not that way.

2.1 - Since the times of Pascal, the probability (P) sector exhibits two widely differing strands of study: applied research achieved outstanding results, while theoretical inquiries began somewhat late; they advanced with difficulty and are still in trouble. We can subdivide modern probability theories in two: the first are abstract and do not have any explicit relation with the physical reality; the second are applied, they fill the gap but turn out to be numerous and incompatible with each other.

What is the reason for these irreconcilable contrasts?

The reason is somewhat apparent. Probability supports countless fields and theories mirror the variety of this concern. Each author applies

P(

Ej) to the special argument

Ej and leading works center on diverse topics. For instance, the formal probability definition of Pierre Simon Laplace [

13] regards

equally likely events (Classical theory). George Boole [

14] associates probability with the logic of human thought and

P qualifies

propositions that may be true or false (Logic-algebraic theory). For John Maynard Keynes [

15], probability provides

logical support to the hypothesis which yields a conclusion. He identifies degrees of

P with degrees of rational belief which however cannot always be estimated (Inferential theory). Rudolf Carnap [

16] views probability theory as an extension of first-order logic, specifically as a logic of partial implication, and sees probability as the measure of the degree of

confirmation of logical induction (Logical theory). Karl Popper [

17] interprets

P as

a property of experiments which is objective and mind-independent (Propensity theory). Jacob Bernoulli, Antoine Cournot, John Venn, Joseph Bertrand and others anticipated the position of Richard von Mises [

18] who identifies probability as the measure of the

collective that is an indefinitely prolonged sequence of trials (Frequentist theory). Frank Ramsey [

19] and Bruno de Finetti [

20], later followed by Leonard Savage [

21] and other Bayesians, regard probability as the assessment of

personal degree of credence established on the basis of prior information (Subjective/ Bayesian theory). Special phenomena occurring in the economy and quantum physics consist of

coupled and mutually compensating events. They can be assessed by means of probabilities that can be lower than zero [

22] (Negative probability theory). For the sake of completeness, I recall a circle of mathematicians which is inclined to bring different perspectives closer together. Among the most stimulating contributions, it should be mentioned David Lewis [

23], P. Philip Dawid and Richard Cox [

24] who, however, do not reach universal consensus.

It is evident how the topics E1, E2, E3, E4… that is to say the collective, a personal belief, rational credence, inductive reasoning and others, can but lead to different views or interpretations; P(Ej) turns out to be objective or subjective, empirical or logical, epistemic or ontological, and real or unreal depending on Ej.

The arguments E1, E2, E3, E4… demonstrate to be anything but trivial since they constitute the first assumptions of the current probability theories. Most of these theories share the axioms of non-negativity, normalization and additivity, however ‘the axiom of the argument P=P(Ej)’ is the most significant for the theory j because it precedes all the others in point of logic. Ordinarily the author of theory j does not formalize the axiom of the argument but appends a lot of verbal annotations to explain it. Moreover, he goes to great lengths to prove to have discovered the unique and authentic probability model P(Ej); and rejects all the others. It may be said that each probability theory is not complete, yet it pretends to become the unique reference in literature. This dogmatic position has led the scientific community to an intellectual deadlock.

Every argument Ej casts light on a significant aspect of indeterminism, it descends from ponderous inquiries and cannot be rejected even if it covers a narrow area. Therefore, the present intellectual deadlock can be overcome by means of a comprehensive construction which embraces all the topics E1, E2, E3, E4…. The present methodological criterion shows how it is impossible to bypass the complete work plan, despite the fact it is far from being popular in the scientific community.

2.2 - The probability domain presents another complex and unresolved difficulty. The so called ‘single case problem’ means that the probability of an individual aleatory outcome does not correspond to the reality, it is unreal. E.g. When one flips a coin, he gets either tails or heads which mismatch with the probability values calculated in abstract.

Frequentist and subjectivist masters are fully aware of this problem and try to overcome it through philosophical and managerial criteria. Frequentists claim to be interested in the experimental control of the random outcome and neglect whether the collectives constitute a special category of events. Subjectivists (including Bayesians) mean to assess any aleatory result, regardless of whether the probability cannot be controlled with experiments. On one side, frequentists focus on the event that is physical but not individual; on the other side, subjectivists use probability to quantify personal belief that is a single event but immaterial. Philosophical approaches prove to be arbitrary in a way, and raise endless disputes. A complete probability theory should go beyond the present intellectual situation; it should unravel the single case problem in mathematical-analytical terms and untangle fundamental questions that have remained unresolved over time.

3. Historical Parallel

Mathematics and hard sciences have close ties in particular they are often subject to a definite priority. I mean to say that physicists can work out a theoretical solution if mathematicians come up with the necessary formal tools in advance. If the latter fail, the former cannot move forward since they lack the necessary language and notions. This methodological precedence leaves no room for personal discretion and allows us to compare the current cultural situation with the birth of classical mechanics (CM).

Motion, velocity, acceleration and force are characterized by magnitude, direction and sense. Newton did not have the rigorous

vectorial theory in hand, yet he was familiar with the parallelogram rule and other notions, which were sufficient to underpin the definitional formulas of classical mechanics [

25]. More lagging behind was research in the area of

infinitesimal analysis which was not invented until the middle of the 17

th century. At that point, the way was opened to develop CFs of modern mechanics [

26,

27].

Nowadays, something like occurs in QM while the obstacles to overcome are placed in the inverse order. Quantum theorists develop CFs but are unable to state DFs. They are familiar with sophisticated mathematical weaponry and calculate complex quantum systems, but the fragmentary probability theories prevent them from explicating the nature of quantum waves and particles.

The failures of eminent scientists reinforce the idea that a precise method is required, a precise direction is to be taken, that is to say, the unified probability theory has top priority for QM. The exhaustive theory is expected to underpin the quantum definitional formulas, while linear operators, spectral theory, complex numbers, Hilbert spaces, etc. support advanced issues with success.

Table 1.

How mathematics sustained the pioneers of classical and quantum mechanics.

Table 1.

How mathematics sustained the pioneers of classical and quantum mechanics.

| |

Support to DFs |

For

Pioneers

|

Support to CFs |

For

Pioneers

|

| CM |

Vector Theory |

Ready |

Infinitesimal Calculus, etc. |

Nearly ready |

| QM |

Probability Theory |

Nearly ready |

Linear Algebra, Differential Calculus, Functional Analysis, etc. |

Ready |

The idea of generalizing some concepts of probability theory with the intent of covering QM, is not new in the literature; various attempts have been made such as the following [

28,

29,

30].

4. Proposing a Way out of the Deadlock

In consequence of the previous remarks (

Section 2) the present research project means to develop a comprehensive construction which begins with the axiom of the argument that is the first to be examined in point of logic [

31,

32].

4.1 - Usually, authors apply

P to what happens or will happen, called

event, or the way in which the event

E can happen, which is named

outcome or

result e. From the times of Laplace onwards, the concepts of

case,

event, and

result came to be overlapping. Presently most writers agree that the event is

a set of outcomes belonging to the event space [

33]:

This definition means that the event is no more than a collection of results, that is to say, E and e are homogeneous in nature. The two entities should have similar characteristics and substance, but the conceptual equality event = outcome raises the following non-trivial issues.

The notion of ‘event’ has increasingly attracted the attention of philosophers outside the probabilistic domain. Since the early 20th century, the growing prominence of the concept of change, to which the event seems inextricably linked, stimulated a number of research [

34]. Moreover, events are logically connected to the systems that are central in computer science, operational research, economics and other fields [

35]. The view expressed by (9) sounds like a questionable simplification in the light of recent studies. The specific properties of the event do not emerge from (9), which appears to be a correct but generic reference.

Probabilists agree that the ‘initial conditions’ are necessary to establish whether an event is random, certain or impossible. For instance, the case in which

A never occurs under the definite conditions is called impossible event; and the case in which

A may occur or not under the definite conditions is random. Essential criteria in the indeterministic domain regard the initial conditions that (9) omits [

36].

Often our representation of the world is propositional or sentential, namely it is of the subject-predicate form, Logicians, subjectivists and others formalize events and results by means of propositions that do not conform to (9). For example, the following event: “Denmark is more likely to win than either of Argentina or China” cannot be represented by the set model.

Concluding, the event is something characterized by the results and also by some preliminaries that are called initial conditions in a material occurrence, hypotheses in abstract reasoning, prior knowledge or information in subjective credence etc. The capability of happening implies an antecedent and a sunsequent when the element that links the first to the second is named process, action, belief, reasoning, deduction and so forth.

4.2 - It is reasonable to assume that the probability argument is equipped with three principal parts, and the

structure in the context of Boolean algebra enables the formalization of these three parts. I mean to employ the formalization developed by Burgin who calls

X the

basic fundamental triad or

basic named set [

37,

38]:

Where X is called the support of X, N is the component of names (reflector) or set of names of X and f is the naming correspondence of X.

I use (10) to define the event which preferably is called

triad or

structure A equipped with the initial conditions

i, the result

x and the relation

r:

The reader can note how (11) does not deny (9) but completes it. Moreover, the outcome x can be formalized as a subset or a proposition depending on the type of problem under examination.

The overall framework based on (11) is named

structural theory of probability; it embraces the frequentist, subjective, logical, etc. viewpoints, in that it allows us to specify the hypotheses

E1,

E2,

E3,

E4…. typical of the varaious views. In fact, the model

A explains how events happen in the physical world and the human mind too. However, this paper centers on the former and overlooks the latter; the complete discussion can be found in [

31,

39,

40].

The

event is something that happens and the triad (11) includes the first and last elements which are linked by

r. The three parts portray the mechanism by which the occurrence of the event is graded. More precisely, if

r definitively connects

i with

x, then the event

A is certain, it occurs for sure. If

r does not link at all,

A is impossible and finally, if the connection of

r does not systematically work, then

A is uncertain and does not regularly happen. The components (

i, r, x) make explicit the grades of event existence, so we define probability

P(

A) as

the theoretical parameter which qualifies the occurrence of A in keeping with the Kolmorovian axioms:

Probability measures the event's avverability and consequently is symmetrical to the

relative frequency F(

x) sometimes called ‘

empirical probability’. Decimal

P(

x) and

F(

x) allow us to formalize the

indeterminate status x(I) of

x; the

determinate status x(D) is given by integers:

We mean to focus on physical occurrences

An that repeat

n times, in particular we bring attention to the single event

A1 and the collective

A∞ which is made by countless single events

A1k (

k=1,2,3…) where the double brackets denote how they are independent and identically distributed. A symmetrical expression holds for the outcomes:

5. Phenomenology of Probability

Physics, chemistry and other hard sciences ordinarily explore phenomena that occur again and again.

5.1 - We assume

A is a repeatable physical event, thus it is possible to establish whether

A is certain, impossible or random (Section 4.2) by analyzing the very structure

A. The three properties are expressed by means of probability in the following manner respectively:

These expressions can be controlled and take clear physical meanings in the world.

Example 1 - A mechanical scale has worn pins. The operator examines the pins and concludes that correct weighing Aw is not sure. The inspection corroborates the decimal value of probability and the randomness of Aw.

Probability (15c) is not a precise numerical value; now we hypothesize that

P(

A) is a precise value consisting of

k digits:

And (16) has been got from calculations, so we wonder:

Can we verify the exact number P(A) in the world?

We shall answer this query by means of theorems whose proofs and complete illustration are included in the book [

40] therefore this paper does not repeat those details.

Theorem of Large Numbers (TLN).

For the random physical event An, if:

The relative frequency approaches the probability:

Example 2 - A fair coin is tossed 1,000 times and the operator gets tails 483 times. The relative frequency of tails 0.483 fairly approaches 0.5.

TLN is the Borel version of the Law of Large Numbers and demonstrates how P(A∞) can be detected and measured, how P(A∞) corresponds with something physical. The unlimited set (14a) constitutes an ideal case; it is unattainable, nonetheless it can be brought as close as the operator likes; the larger n of trials and the better the control of the calculated P(A∞).

Theorem of a Single Number (TSN).

For the random physical event An, if:

The relative frequency mismatches with the probability:

Example 3 - Probability of getting heads (or tails) from a fair coin is 0.5; the relative frequency of each result is 0 or 1.

Basically, TSN begins to address the single case problem in mathematical terms. TSN proves that experimental substantiation of P(A1) is unworkable, because the outcome of the single event is out of control. There are not any instrumental or operational obstacles which could be overcome by technological progress. Statement (20) is obtained on the logical plane and future technical advance will not disprove it.

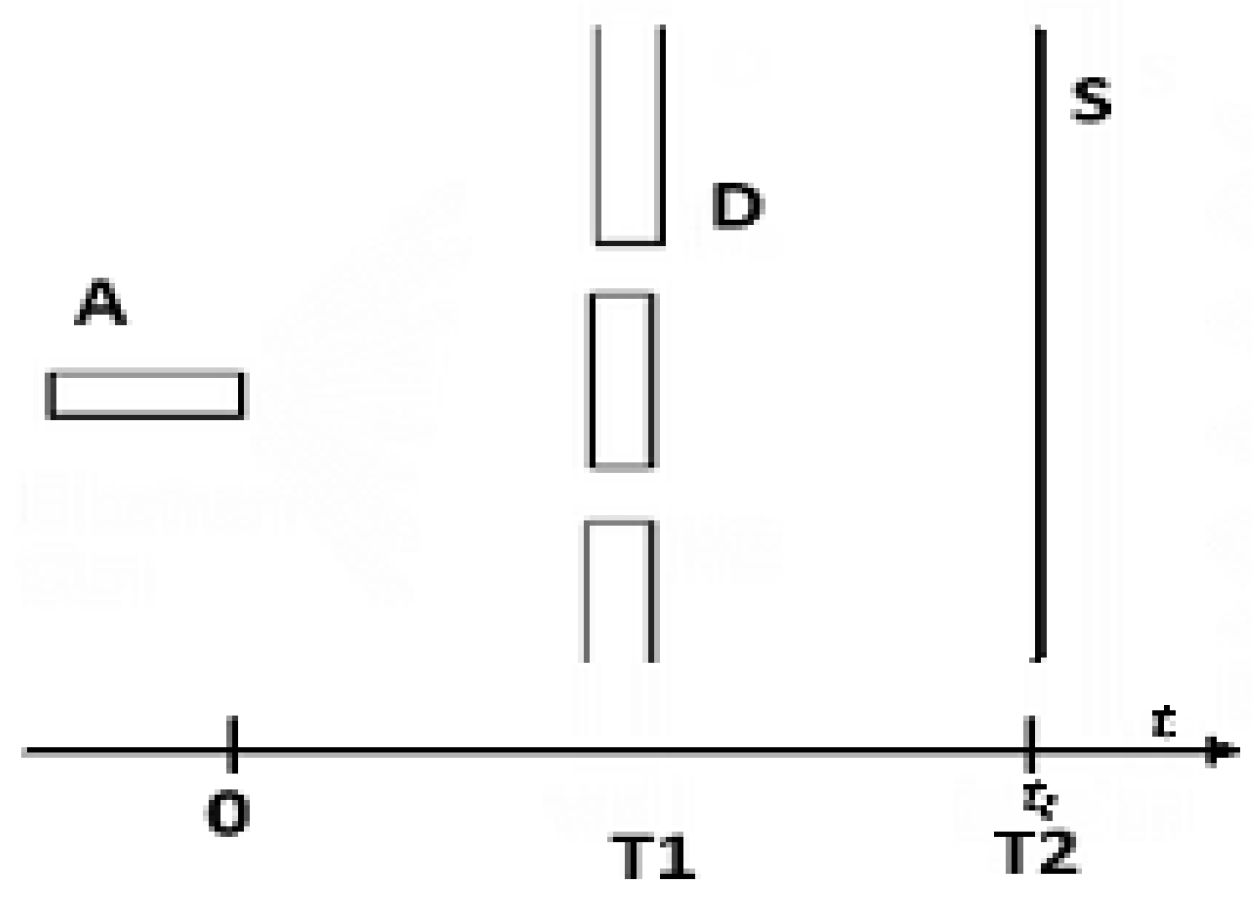

5.2 - Science and technology are based on testing and TSN leads us to explore the topic further. We locate (11) in the time scale; A starts at the instant to = 0 and finishes at tx that is the delivery time of x. When the event repeats tx is the time of the last outcome. We obtain the time intervals T1 with 0 < t < tx, and T2 with t ≥ tx.

Authors usually assess the probability of the random outcome regardless of the temporal evolution of x. Iit may be said authors assign probability ‘en block’; instead things are much more complicated. We examine the determinate/indeterminate statuses of x in the intervals T1 and T2 respectively.

Corollary of Initial Conditions (CIC). Supposing An complies with (15c), then also the outcome xn is random in T1:

This statement, somewhat intuitive, introduces the study of the interval T2.

Theorem of Continuity (TC). The outcome of the long-term event keeps the indeterminate status in T2:

Example 4 – The result tails of Example 2 occurs 483 times, statement (22) says that tails are uncertain during T1 and also in T2 when the thousand throws are over.

Theorem of discontinuity (TD): The outcome of the single event switches from the indeterminate to the determinate status at the end of T1.

This statement confirms and clarifies TSN: P(x1) cannot be measured since the random x1 no longer exists. The change (23) is fast [(23) is instantaneous], global [(23) involves x1entirely] and irreversible, thus (23) describes the collapse of x1(I).

Example 5 – The result heads of Example 3 is uncertain when the coin flies in the air (= T1) and becomes certain or impossible as soon as the coin lies on the table (= T2).

5.2.1 – We become aware that the paired theorems TLN-TC and TSN-TD present diverse and rather contrasting phenomena:

TLN and TC prove that P(x∞ ) can be measured. The greater the number of trials n, the more experimental results approximate the calculated value.

TSN and TD prove that the value P(x1) not only cannot be measured, it neither can be detected because x1(I) becomes determinate namely it vanishes. Expression (15c) formalizes the randomness of the outcome in T1 that can be forecast in a way; by contrast, the precise number P(x1) cannot be controlled because x1 collapses.

5.2.2 - Collapsing does not undergo spatial constraints because TD is true regardless of the distance between the parts involved. The outcome switching does not have distance limitations; it produces instantaneous effects over remote systems and has non-locality property.

Example 6 - A deck of cards is shuffled, and the probability of each card C is one over fifty-two during the shuffling process (= T1). Now suppose the king of diamonds

K is picked up so the frequency of the king becomes a unit while the frequency of the other cards drops to zero in T2:

Now suppose the cards are randomly distributed in the Universe. Each lies in a different galaxy and change (24) is true even if the cards are light years apart from one another.

Is there any information exchange among the cards?

Semiotics, the science of signs and information, holds that any communication has a material conveyor called signifier and represents something called meaning or signified. This entails that whatever communication is bound to some exchange of energy or matter. Instead, the theorem of discontinuity does not involve anything material; it proves that the instantaneous status change does not depend on physical actions or objects. There is no transmission of signals at faster speed than that of light; so, non-locality, the property typical of the single random event, does not violate the special relativity. All this is consistent with the no-communication theorem proved in quantum mechanics.

5.2.3 - Probability is a parameter that presents weird behaviors; however, these behaviors are forecast by the previous theorems with precision. We are able to describe objects and properties, even if they cannot be measured. Writers call counterfactual definiteness the ability to speak meaningfully of the results of measurements that cannot be performed.

5.2.4 - In conclusion, the structural theory of probability proves that classical physics shares the untestability of the single random result, collapsing, non-locality and counterfactual definiteness that seemedexclusive to quantum physics so far.

5.2.5 - In recent years, applications of quantum theory in fields other than physics have increased in number and variety, they extend to fields such as psychology, decision making, economics, finance, social sciences, genetics and molecular biology [

41]. Theorists are also reformulating quantum measurement theory to make the use of quantum concepts clearer [

42,

43]. The present structural modeling supports this challenging research as it establishes all the elements that are necessary to obtain the probability of an event; moreover formal representations specialize for events occurring in the material world and for those occurring in the human mind. However, the analysis which goes beyond the scopes of the present paper can be found in [

40].

6. Quantum Interpretation Based on Probability

The scope of this work is to show how the structural theory of probability offers an aid to disentangle foundational quantum issues, so we employ the concepts and theorems just presented [

44], and shall keep aside Hilbert space, eigenfunctions and other formal tools ordinarily used in quantum mechanics.

6.1 Premise - We assume principles

{1} and

{2} true; and we mean to formalize the particle and wave states following the correct methodology which relies on universal empirical knowledge (

Section 1).

Undisputable experience brings evidence of how the particle has a null volume, whereas the wave occupies a certain volume in the Euclidean space Σ:

Because of the uncertainty principle, we introduce the probability of finding ξ in a point of Σ: P[ξ χ (x,y,z)].

6.2 DFs and CFs - The particle is a condensed portion of energy and possibly matter that I define as the

determinate spatial status ξ(D) of the quantum

ξ:

The wave is spreading, and I fix it as the

indeterminate spatial status of ξ:

From the integer values of (26a), we obtain that the Dirac Delta function δ is the spatial probability distribution of

ξ(D):

In consequence of the indeterminate status of the wave, we use the wavefunction to detail

ξ(I). In other words, the present theory justifies Born’s rule on the basis of definition (26b):

Definitional formulas (26a) and (26b) establish the general statuses of ξ(D) and ξ(I) while the shapes of (25a) and (25b) are given by δ(x,y,z) and |Ψ(x,y,z,t)|2 that play the roles of computational formulas. Universal experience corroborates that particles have a unique shape, while quantum waves take an assortment of forms depending on specific physical constraints.

Quantum waves are diffused portions of energy and possibly matter while particles consist of condensed energy/matter, there is a physical continuity between the two states that P[ξ χ (x,y,z)] formally ensures. Also, CFs exhibit continuity because Dirac function is a limit case of |Ψ(x,y,z,t)|2.

6.3. Can We Test DF and CF Using Experiments?

TSN and TLN demonstrate that probability behaves differently depending on the number of events involved, so we distinguish two kinds of waves:

Example 7 – Suppose ξ1(I) is a photon, then (31) is an electromagnetic radiation which matches with the quantic interpretation of electromagnetic wave including countless photons.

Let us verify the concepts just introduced by means of the simplest experiment:

the free motion of quanta AF in Σ. It is not trivial since it is a part of several quantum phenomena. We define the structure

AF of the free movement including the emitter, the moving and the result that are

n quanta at the arrival:

By definition, the ergodic source does not determine any precise trajectory of ξn so the event AF is random. The corollary of initial conditions proves that also the outcome ξn is random in T1, namely, the quanta launched by the ergodic source are waves, no matter they are single or make a radiation. The present theory links ξn(I) to the emitter and several experiments confirm that tungsten filaments, hot ovens, molybdenum emitters, radioactive sources, plasma emitters, fluorescent tubes, and laser systems cast waves and not particles. Countless tests corroborate this conclusion deduced on paper and ignored by several physicists.

Example 8 – For the sake of simplicity, I confine myself to a couple of pioneers’ works. Thomson, Davisson and Germer first showed that the electrons cast by a tungsten filament are waves [

45].

The flight AF remains free as long as nothing modifies it; when a physical element affects (32), by definition, AF is no longer free and terminates in a way. It is important to underscore that ‘Moving’ is random in (32), it is indifferent to the trajectory direction and thus mirrors, prisms, slits and other devices that modify the trajectory of ξn do not determine the end of AF, which remains free. The movement (32) finishes only if the result changes namely ξn absorbs or cedes energy. For example, in consequence of anelastic collision, the flight is no longer free, and AF ends. Here, we pay attention to the measurement or even the detection processes that typically absorb energy and cause the free movement to terminate; in particular we assume the measurement is destructive and T2 lasts an instant.

What does exactly happen when AF terminates?

It depends on the number of flying quanta.

▪ TLN and TC prove that the radiation

ξ∞(I) can be controlled since it keeps the indeterminate status in T2:

This conclusion is amply corroborated - for example - in classical optics and later we shall provide particulars about this point.

▪ TSN and TD prove that the wavelet cannot be measured since it becomes determinate when the free motion finishes, in physical terms the wavelet becomes a particle in T2:

The termination of AF of the single quantum is a complicated; it includes various mechanisms, physical and probabilistic as well.

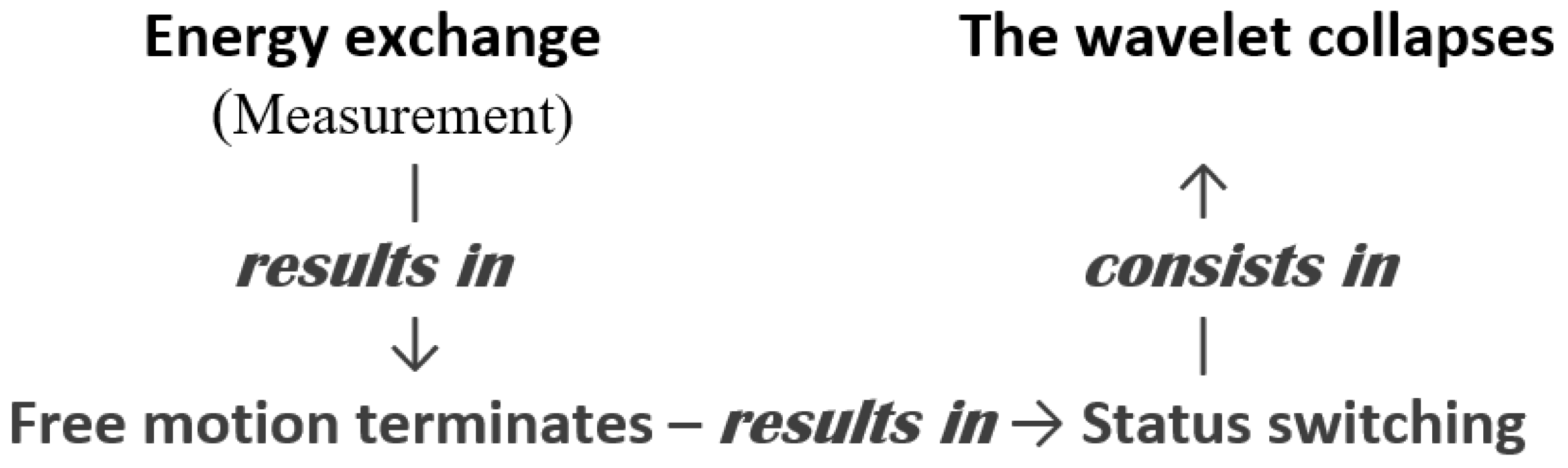

How are they logically connected? What are the causes, what the consequences?

The operator activates the entire process, namely the measurement device absorbs energy and results in the end of

AF. This termination, in turn, causes the probability switching, that consists in the collapse of the wavelet.

Figure 2 presents the probability notions placed in the bottom line that justify the physical mechanisms placed in the upper line.

In the history of QM, the idea of collapse was introduced by scientists to make sense of an important problem. If the wavefunction says the particle can ‘be’ in a bunch of different places, and then we observe it to be in a specific place, what happens to the rest of the wave?

The wave collapse was proposed as a solution to this kind of problem, but it is not a definitely know fact about the way wavefunctions behave. So, the present framework provides a detailed answer and makes explicit the mechanisms occurring at the end of the free motion of ξ1(I).

7. Double Slits Experiment

How can we observe the wave collapse?

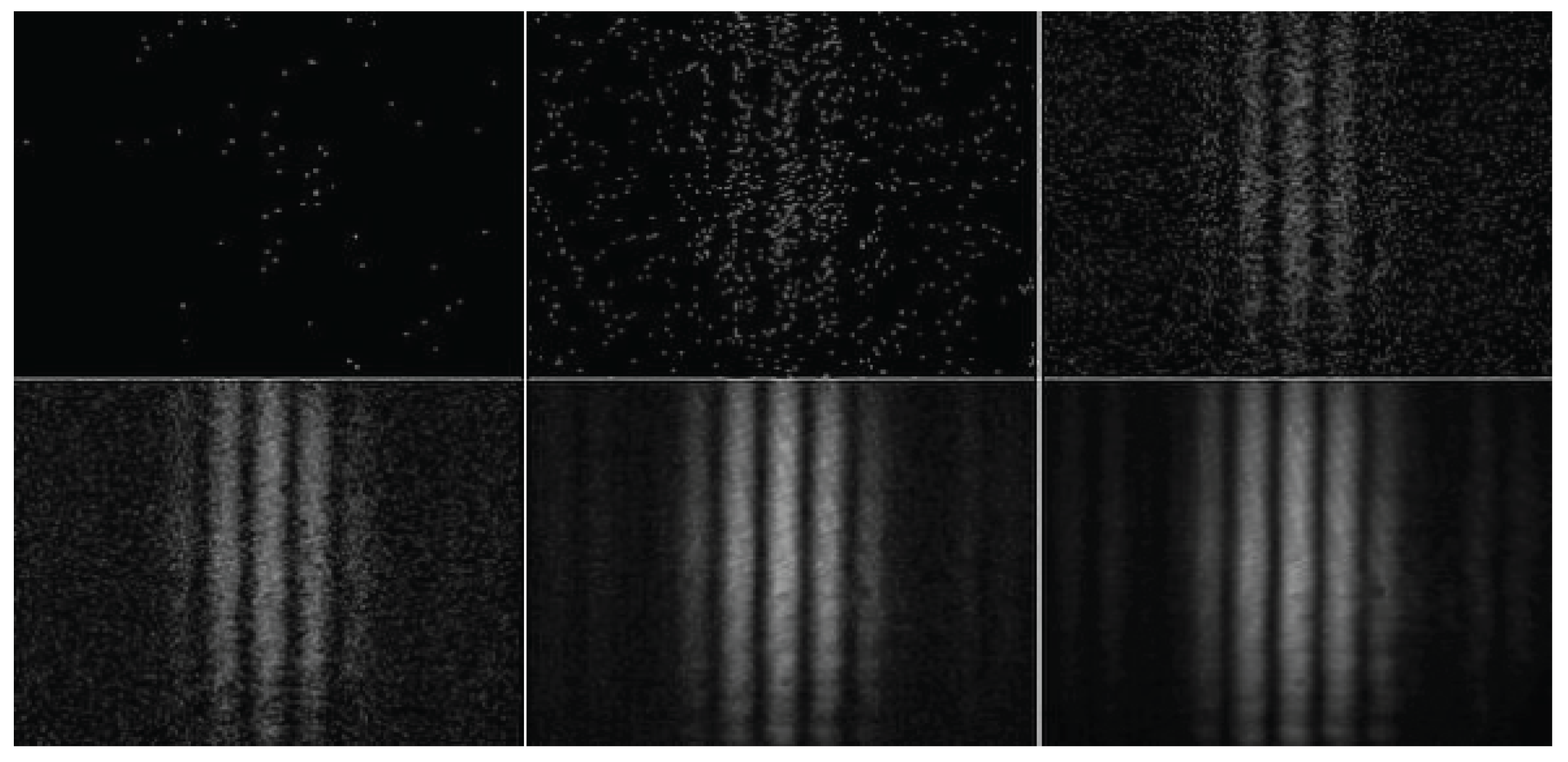

The double slits experiment is the ‘most beautiful’ test for this purpose (

Figure 3). The laser casts an intense beam in the first version of the test and a photon at time in the second version [

46].

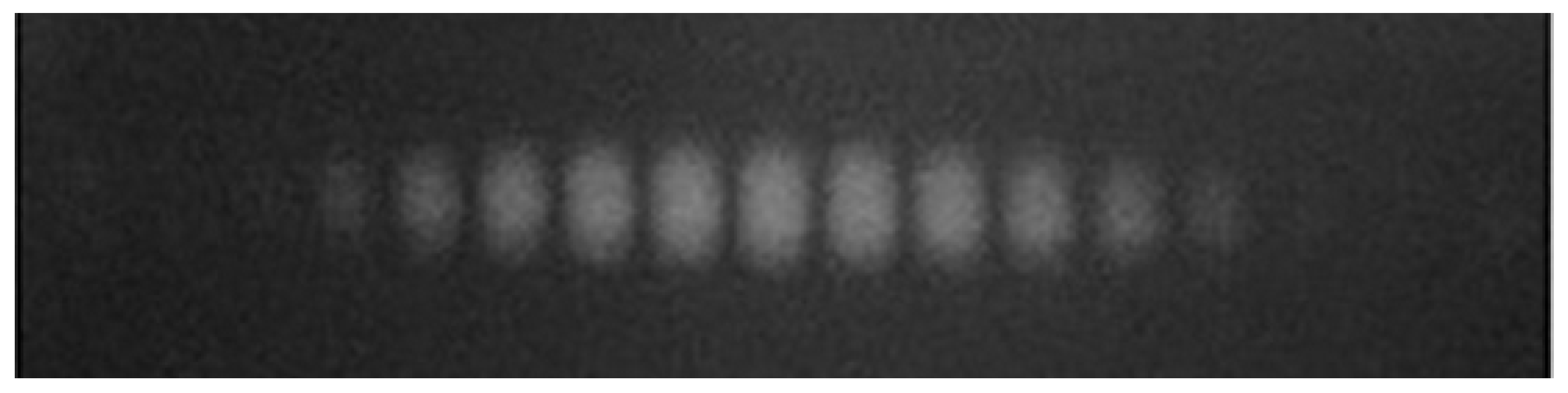

First version: Laser

A emits radiation which crosses the slits

D. The screen

S exhibits a continuous interference pattern (

Figure 4) which brings evidence that the photons moving in T1 are waves in conformity with the corollary of initial conditions. The pattern on the screen even indicates that the radiation of photons remains during T2 which lasts only one instant due to the destructive measurement:

The strong beam remains indeterminate during T1 and T2, and this experiment typical of classical optics substantiates TLN and TC.

Second version: Now suppose A casts a single photon at a time; we observe effects i) and ii) occurring in parallel.

i) The screen exhibits a single spot bringing evidence there is a particle in T2. CIC proves that the ergodic source emits a wavelet, therefore the incoming single photon is a wavelet in the time interval T1 and becomes the particle

ξ1(D) in T2:

The wavelet which collapses corroborates TSN and TD.

ii) When several photons are launched one by one, the present theory entails that they make the following radiation:

Actually, the flow of photons crosses the slits and creates the discrete interference pattern on

S (

Figure 5) because it is a radiation which perfectly substantiates (36). The larger the number of incoming photons, the more clearly the discrete spectrum brings evidence of

ξ∞(I) in accordance with TLN. The second version of the double slit experiment corroborates the notions of measurement and collapsing proposed in this paper.

This experiment turns out to be a complex phenomenon and raises some questions which we can answer in the following manner:

What is measurement?

For the present framework, measurement is a process that typically absorbs energy from ξn(I) due to the anelastic microscopic collisions and results in closing the free flight of ξn(I).

Does the wavefunction collapse involve human consciousness?

TSN and TD deal with the quantum wave and do not deal with any mental or human factor. They involve solely objective mechanisms. Experimental evidence confirms how nonconscious systems such as an unmonitored measuring device can result in the collapse of the wavelet.

How to find the slit crossed by the single photon?

The present theory demonstrates that the ergodic source triggers the aleatory movement

AF, so it launches waves and not particles. The so called ‘which way problem’ has no ground here because this theory demonstrates that no particle is flying in T1. Moreover, the interference pattern is incompatible with any information about the path taken by the quantum [

49]. In fact, the present theory demonstrates that whatever detection of wavelets results in the end of the free movement.

If one closes a slit, does he obtain a gaussian distribution on the screen?

This result was imagined by Feynman [

50] who devised a thought experiment with a slit closed and the other opened. It is important to underline that the lateral fringes of the diffraction pattern created with a slit are feebler than those of the interference pattern created with two slits. Despite this difficulty, Bach [

51] and others (Zeilinger, Zhou etc.) bring evidence that a weak beam of electrons, photons etc. when crossing a slit, create a diffraction pattern in perfect agreement with the present theory.

Is the double slits experiment exclusive to elementary particles?

Principles of quantization and duality establish the double nature of quanta. This means that any portion of energy/matter that conforms with

{1} and

{2}, is a quantum for the present theoretical framework. Significant improvements in interferometric resolution techniques have enabled scientists to observe the patterns created by atoms and large molecules [

52] which corroborate assumptions

{1} and

{2} of present theory.

8. Conclusion and Outlook

This inquiry begins with a methodological remark. It supposes that quantum mechanics meets some ‘pre-problems’ which hinder the progress of our knowledge. They relate to the methodology of theory-building and have not been adequately addressed by quantum scientists, and this is a reason why QM is not as well understood as it could be. The paper identifies the features of computational and definitional formulas as the first methodological issue to resolve, the fragmentary interpretations of probability as another and lastly the single case problem.

The research plan makes a radical decision, it proposes a novel and comprehensive probability theory – called structural theory - in order to unify all the current viewpoints, to resolve the single case problem and formalize the particle and wave states of quanta.

The structural theory begins with the accurate modeling of the arguments and derives the main probability theorems from this concept. In particular it shows how the untestability, collapsing, non-locality and counterfactual definiteness are typical of indeterminism in both quantum and classical contexts. The probability-based interpretation of QM comes from this premise and makes an attempt to answer the problems about quantum duality, measurement, collapsing, and the relationship classical-quantum physics. It is an incredibly simple framework since the issues have been set in advance.

Someone asks the reasons for my double affiliation, which are as follows.

I worked at IBM and received the title of emeritus docent when I retired. Shortly later I joined LUISS which is a private university in Rome. After so many years, I lost all contacts with the corporation, and this research is just a solitary personal initiative. Various researchers interested in the present results, wait for a corporate signal that cannot come instead. They are holding back from giving an evaluation and it is natural to conclude how this ample and unfortunate work is destined to go into ‘oblivion’ forever.

The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Myrvold W. Philosophical Issues in Quantum Theory, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2016. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qt-issues/ (accessed on February 2025).

- Barrett J.A. The Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Maudlin T. Philosophy of Physics, Quantum Theory, vol. 2, Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Wimmel H. Quantum Physics & Observed Reality: A Critical Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. World Scientific, 1992.

- Hughes R.I.G. The Structure and Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Harward University Press, 1989.

- Manzano D. The Ongoing Debate About the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, 2013. https://mappingignorance.org/2013/01/21/the-ongoing-debate-on-the-foundations-of-quantum-mechanics/ (accessed on February 2025).

- Baggott J.E. The Quantum Story: A History in 40 Moments. Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Einstein A. On the present status of the radiation problem, Physikalische Zeitschrift, 1909, 10: 185-193.

- Anastopoulos C. Particle or Ware, The Evolution of the Concept of Matter in Modern Physics, 2020, Princeton University Press.

- Ney A., Albert D. (eds) The Wave Function: Essays on the Metaphysics of Quantum Mechanics, Oxford University Press, 2013.

-

D'Auria R., Trigiante M. From Special Relativity to Feynman Diagrams. Springer, 2012.

- Shan G. (ed.) Collapse of the Wave Function: Models, Ontology, Origin, and Implications, Cambridge University Press., 2018.

- Laplace P.S. Théorie Analytique des Probabilités, Courcier, 1812.

- Boole G. An Investigation of the Laws of Thought on Which are Founded the Mathematical Theories of Logic and Probabilities, MacMillan, 1854.

- Keynes J.M. A Treatise of Probability, McMillan & Co., 1921.

- Carnap R. Logical Foundations of Probability, University of Chicago Press, 1950.

- Popper K.R. The Propensity Interpretation of Probability, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 1959, 10(37): 25-42.

- von Mises R. Probability, Statistics and Truth, Dover Publications, 1981.

- Ramsey F.P. Truth and probability, In Braithwaite R.B. (ed), The Foundations of Mathematics and other Logical Essays, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1931.

- de Finetti B. Sul significato soggettivo della probabilità, Fondamenta Matematicae, 1931, 17: 298-329.

- Savage L.J. The Foundations of Statistics, John Wiley & Sons, 1954.

- Khrennikov A. Interpretations of Probability, De Gruyter, 2009.

- Lewis D.K. A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In Richard C. Jeffrey (ed.), Studies in Inductive Logic and Probability, vol II: 263-293, University of California Press, 1980.

- Cox R.T. The Algebra of Probable Inference, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1961.

- Truesdell C. (ed) Essays in the History of Mechanics. Springer, 1968.

- Dellian E. Inertia, The innate force of matter: A legacy from Newton to modern physics, In. P. Scheurer, G. Debrock, (Eds.) Newton’s scientific and philosophical legacy, Kluwer Academic Publisher, 1998.

- Westfall R.S. Force in Newton’s physics. Macdonald, 1971.

- Mancini S., Man'ko V.I., Tombesi P. Symplectic tomography as classical approach to quantum systems, Physics Letters A, 1996, 213 (1-2): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9601(96)00107-7 (accessed on February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wetterich C. Quantum particles from classical statistics, 2010, arXiv:0904.3048v2.

- Chernega V.N., Man’ko O.V. Dynamics of System States in the Probability Representation of Quantum Mechanics, Entropy, 2023, 25(785):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Rocchi P. The Structural Theory of Probability, Kluwer/Plenum, 2003.

- Rocchi P., Burgin M. An essay on the prerequisites for the probability theory, Advances in Pure Mathematics, Special issue on Probability and Mathematical Statistics, 2020, 10: 685-698. [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov A. Foundations of the Theory of Probability, Dover Publ. Inc., 2018.

- Honderich T. Events. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Hustwit J.R. Process Philosophy. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2007. https://philpapers.org/rec/HUSPP (accessed on February 2025).

- Strevens M. Dynamic probability and the problem of initial conditions, Synthese, 2021, 199: 14617-14639. [CrossRef]

- Burgin M. Theory of Named Sets, Nova Science Publ., 2011.

- Burgin M. Structural Reality, Nova Science Publ., 2012.

- Rocchi P. Janus-Faced probability, Springer, 2014.

- Rocchi P. Probability, Information and Physics: Problems with quantum mechanics in the context of a novel probability theory, World Scientific, 2023.

- Khrennikov A.Y. Open Quantum Systems in Biology, Cognitive and Social Sciences, Springer, 2023.

- Davies E.B., Lewis J.T. An operational approach to quantum probability. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 1970,17: 239-260. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa M. Conditional probability and a posteriori states in quantum mechanics, Publications of the Research Institute of Mathematical Sciences, 1985, 21(2): 279-295.

- Rocchi P. A Short Report on the Probability-Based Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Open Physics, 2024, 22(1): 20240047. https://doi.org/10.1515/phys-2024-0047 (accessed on February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rohlf J.W. Modern Physics from A to Z, Wiley, 1994.

- Howie A., Fowcs W.J.E. (eds) Interference: 200 years after Thomas Young's discoveries, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 2002, 360: 803-1069.

- Fanaro M., Arlego M., Otero M.R. The double slit experience with light from the point of view of Feynman’s sum of multiple paths, Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Fısica, 2014, 36(2): 2308. [CrossRef]

- Anton Paar, Photos available at: https://wiki.anton-paar.com/be-fr/experience-du-dispositif-a-double-fente/#double-slit-experiment-with-single-photons (accessed on February 2025).

- Tan S.M., Walls D.F. Loss of Coherence in Interferometry, Physical Review A,1993, 47(6):4663-4676.

- Feynman R.P. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, 1965, Vol. 3: 1–8, Addison-Wesley.

- Bach R., Pope D., Liou S., Batelaan H. Controlled double-slit electron diffraction, New Journal of Physics, 2013, 15(3), 1–7.

- Hackermüller L., Uttenthaler S., Hornberger K., Reiger E., Brezger B., Zeilinger A., and Arnd M. Wave nature of biomolecules and fluorofullerenes, Physical Review Letter, 2003, 91, 90408. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).