1. Introduction

Skin aging is a physiological process characterized by the progressive decline of essential skin functions, including its ability to retain water. Reduced hydration compromises the structural integrity of the epidermis, leading to dryness, loss of elasticity, wrinkle formation, and a rough, dull appearance [

1,

2]. The stratum corneum requires optimal hydration to preserve barrier function, elasticity, and a healthy appearance. Consequently, skin moisturizing is a primary objective in the development of cosmetic products designed to prevent or attenuate visible signs of aging. Insufficient moisturizing also disrupts epidermal renewal and barrier function, further exacerbating uneven skin texture and tone. To counteract these effects, humectants and moisturizers are widely incorporated into cosmetic formulations to enhance water retention and maintain skin hydration [

3,

4,

5].

In recent years, natural ingredients have gained increasing relevance as moisturizing agents due to their functional properties, safety, and compatibility with sustainable formulations. Among them, pectins—a class of plant-derived polysaccharides—are of particular interest. Pectins are known for their water-binding ability, gelling capacity, and contribution to texture and stability in cosmetic systems. Beyond their technological applications, several studies suggest that pectins exert beneficial effects on skin moisturizing and restoration. Their performance as gelling and film-forming agents depends largely on their chemical features, particularly galacturonic acid content and the degree of methoxylation [

5,

6,

7,

8]

Passiflora ligularis (granadilla), a member of the Passifloraceae family, is native to the tropical Andes and is the second most economically important species of the genus after passion fruit. Colombia is the leading global producer, with 4,500 hectares cultivated and an annual yield of approximately 20,000 tons [

9,

10,

11,

12]. This species is characterized by a diverse phytochemical profile, including flavonoids, saponins, phenolic compounds, and carbohydrates such as pectins. Structurally, pectins are complex macromolecules composed of up to 17 different monosaccharides and more than 20 types of linkages. They consist mainly of three domains: homogalacturonan (HG), rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I), and rhamnogalacturonan II (RG-II). HG is the most abundant, representing around 60% of pectins in plant cell walls. The chemical heterogeneity of RG-I and the highly conserved structure of RG-II, together with the methylation and acetylation patterns of HG, strongly influence the functional properties of pectins [

6,

7,

13,

14,

15].

Given its rich composition, P. ligularis represents a valuable source of pectins that can be extracted from peel and mesocarp. Previous studies have reported favorable extraction yields and physicochemical properties that support its potential for cosmetic applications, particularly in terms of water retention capacity [

16]. However, the use of P. ligularis pectins in topical formulations remains limited. Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the moisturizing potential of cosmetic formulations incorporating pectins extracted from agro-industrial by-products of P. ligularis, proposing a sustainable and innovative alternative for skin care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Organic residues of Passiflora ligularis (granadilla), obtained from domestic fruit consumption, were employed for pectin extraction. The residues consisted of peel and mesocarp, which were thoroughly washed with potable water followed by deionized water, oven-dried at 40 °C for 48 h and subsequently milled and sieved to achieve a uniform particle size distribution.

2.2. Exploratory Extraction

Two extraction methods were initially evaluated. The first consisted of a hot-water reflux extraction at 90 °C, using a ratio of 1 g of plant material to 20 mL of solvent. The second method involved acid extraction with citric acid (0.125 N and 0.250 N) and hydrochloric acid (0.125 N and 0.250 N) at 40 °C and 60 °C. In total, 18 trials were performed by varying solvent type, acid concentration, temperature, and extraction time. The extracted pectins were precipitated with 95% v/v ethanol, dried, and weighed to calculate yield (%).

2.3. Experimental Design

Based on the exploratory stage, a 24 factorial design was implemented to evaluate solvent (water and citric acid), extraction method (reflux and microwave-assisted), temperature (50 °C and 60 °C), and time (15 and 25 min). Sixteen experimental combinations were performed in triplicate, using extraction yield (%) as the response variable. Each pectin extract was filtered and precipitated with two volumes of 95% v/v ethanol. The recovered pectins were lyophilized, milled into a fine powder, and stored for subsequent analyses [

17,

18,

19].

2.4. Pectin Characterization

Moisture content was determined by drying the samples at 105 °C for 24 h and calculated using Equation 1 [

20]. The acidity percentage was measured by acid–base titration with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide, using phenolphthalein as an indicator, and calculated according to Equation 2 [

21]. Briefly, 0.2 g of pectin were dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water and titrated with 0.1 N NaOH until a faint pink color appeared (initial titration). Subsequently, 10 mL of 0.1 N NaOH were added, the solution was shaken, and allowed to stand for 30 min. Thereafter, 10 mL of 0.1 N HCl were added until the pink coloration disappeared. A second titration with 0.1 N NaOH was then carried out until the faint pink color persisted (final titration). The methoxyl content was calculated from the second titration (Equation 3), while the degree of esterification was determined based on the milliequivalents of NaOH consumed in both titrations (Equation 4).

2.5. Swelling Capacity and Water Retention Capacity

Swelling capacity was determined by measuring the volumetric increase of the sample after 24 h of hydration. Briefly, 0.400 g of dry pectin were gradually dispersed in 10 mL of distilled water in a graduated cylinder [

22]. The mixture was allowed to hydrate at room temperature for 24 h, after which the volume of the solid phase and the final volume of the hydrated sample were recorded (Equation 5).

Water retention capacity was assessed by centrifuging the hydrated samples followed by gravimetric analysis. The parameter was calculated according to Equation 6, where W1 corresponds to the weight of the hydrated material after centrifugation or draining, and W0 to the initial dry weight of the sample.

2.6. ATR-FTIR and NMR Spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR spectra were acquired using a Thermo Nicolet iS50 spectrophotometer equipped with a diamond crystal. Measurements were recorded in the 4000–400 cm⁻¹ range at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, averaging 64 scans per sample. Spectral data were subsequently processed with ATR corrections and baseline adjustments to enhance signal quality.

For NMR analysis, 10 mg of pectin were dissolved in 0.5 mL of deuterium oxide (D₂O). Proton (¹H), DEPT-135, and HSQC spectra were obtained on a Bruker Ascend III HD 600 MHz spectrometer at room temperature. Chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm).

2.7. Preparation of Cosmetic Formulations

Table 1 summarizes the exploratory formulation, designed to obtain a hydrating gel with light consistency, acceptable stability, and pleasant organoleptic properties. Based on this initial approach, eight hydrating gel formulations (

Table 2) were developed using pectin extracted from Passiflora ligularis, aiming to optimize physicochemical stability, texture, sensory attributes, and skin compatibility. All ingredients were verified in the European Commission’s CosIng database to ensure safety, permitted concentrations, and authorized cosmetic use [

23].

The formulation process was carried out in two phases. Phase A consisted of dispersing Carbomer in deionized water, followed by neutralization with the selected base (triethanolamine or sodium hydroxide) until reaching an approximate pH of 6.0. Phase B contained pectin, the antioxidant, and the preservative, which were dispersed separately to prevent premature interactions that could compromise system stability. Both phases were then combined under controlled stirring and subsequently homogenized at 300 rpm using a rotor–stator system (Ultra-Turrax T25 Basic, IKA, Germany), ensuring uniform ingredient distribution and final pH adjustment to 5.5.

2.8. Preliminary Stability

The formulation was stored for seven days under the conditions described in

Table 3 to simulate thermal and environmental stress. Visual and tactile evaluations were performed to assess color, homogeneity, phase separation, texture, flow, and viscosity. Olfactory analysis was carried out to detect signs of degradation or microbial contamination. Application-related parameters, including drying time and residual skin feel, were also recorded. In addition, pH was monitored to evaluate chemical stability and potential skin compatibility.

Photostability was assessed by exposing the formulation, contained in a beaker, for 2 h in a solar simulator (Solarbox 1500e; Erichsen, Germany) equipped with a 1500 W xenon arc lamp and UV glass filters to block radiation below 290 nm. Irradiance was maintained at 325 W/m² in accordance with global solar spectral standards. Sensory analysis was subsequently performed to detect color changes indicative of oxidation [

24,

25,

26].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Multiple range tests were performed using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) procedure, and a four-way ANOVA was applied to assess possible interactions among variables. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. All results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using Statgraphics Centurion software (Statgraphics Technologies, Inc., USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Exploratory Extraction

The exploratory extraction revealed significant differences in pectin yield under the evaluated conditions. The highest yields were obtained using distilled water at 90 °C for 60 and 30 minutes, with values of 4.54% and 4.08%, respectively. Similarly, extraction with hydrochloric acid (0.125 N) at 60 °C for 60 minutes yielded 3.81%. For citric acid, the maximum yield was achieved with 0.125 N at 60 °C for 60 minutes, resulting in 3.08%.

When comparing solvents, water exhibited the highest average yield (4.31%), followed by hydrochloric acid (3.13%) and citric acid (2.14%). These results confirm that solvent type, temperature, and extraction time significantly influenced (p<0.05) both yield and physicochemical properties of the extracted pectins. The highest yields were achieved with water at 90 °C and hydrochloric acid at 60 °C.

However, pectins extracted with hydrochloric acid displayed a rigid and brittle texture, attributed to hydrolysis by this strong acid, which promotes demethylation and markedly reduces the degree of esterification (DE) and galacturonic acid content. A lower DE results in low-methoxyl pectins, which form harder gels through divalent ion interactions [

27].

Conversely, citric acid (a weak acid) yielded with more suitable physical characteristics for topical formulations. This mild hydrolysis preserved the polysaccharide backbone more effectively and favored higher methoxyl content [

27]. As a result, the gels obtained were softer, more flexible, and easier to handle, particularly in the presence of sugar and acid, thereby fulfilling cosmetic formulation requirements [

28,

29,

30].

Although citric acid extractions produced slightly lower yields, the quality and functional performance of the gels were prioritized over quantity. Therefore, only water and citric acid were selected as solvents for the subsequent experimental design to ensure the stability and efficacy of the final formulation.

3.2. Experimental Design

A 2⁴ factorial design was used to evaluate the effect of four factors on the yield of pectin extracted from P. ligularis: solvent, extraction method, extraction time, and temperature. ANOVA revealed that the most influential factors were the extraction method, solvent type, and their interaction, all statistically significant (p < 0.05). The determination coefficient (R²) of 95.01% confirmed the robustness and accuracy of the model.

Microwave-assisted extraction consistently yielded higher percentages than reflux. The maximum average yield (47.37%) was obtained with citric acid at 50 °C for 15 minutes (E15), followed by E13 (citric acid, 60 °C, 15 min; 45.97%) and E14 (citric acid, 60 °C, 25 min; 32.85%). In contrast, reflux extractions with citric acid (E5–E8) produced negligible yields (<2%), confirming their low efficiency (

Table 4).

Water-based extractions yielded intermediate values, ranging from 5.84% to 22.43%. Within this group, the highest results were obtained with E10 (water, 60 °C, 25 min; 22.43%) and E12 (water, 50 °C, 25 min; 14.53%). However, under some microwave conditions with water or citric acid (E9, E10, E12, E14), effective pectin precipitation was not achieved, possibly due to the co-extraction of interfering soluble solids, which highlights the need to assess not only yield but also extract quality.

These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that microwave-assisted extraction enhances efficiency by generating rapid and selective volumetric heating, promoting cell wall disruption and polysaccharide release while minimizing thermal degradation [

31,

32,

33]. Conversely, reflux extraction is less effective due to limited energy transfer and potential degradation of plant material under prolonged heat exposure.

The theoretical optimal yield was estimated at 45.23% (citric acid, microwave, 60 °C, 15 min). Nevertheless, no statistically significant differences were found compared to 50 °C and 15 min, based on multiple range tests. Therefore, 50 °C was selected as the definitive condition to reduce energy consumption and prevent excessive degradation of the pectin. Main effects analysis showed positive slopes for all factors except time, with extraction method exerting the greatest impact. Interaction plots confirmed that the microwave–citric acid combination was the most effective condition for pectin recovery.

The yields obtained in this study (up to 47.37%) are comparable to or even higher than those reported for pectins extracted from conventional sources such as citrus peel (20–35%) and apple pomace (10–20%) [

17,

18,

19]. They are also superior to yields described for passion fruit (

Passiflora edulis) by-products, which generally range from 10% to 25% depending on the extraction method [

15]. These results highlight P. ligularis peel and mesocarp as a promising, underutilized agro-industrial residue for pectin production. Beyond yield, the selection of citric acid under microwave-assisted conditions provides an environmentally friendly and efficient alternative that aligns with sustainable development goals while ensuring functional properties suitable for cosmetic applications.

3.3. Pectin Characterization

Characterization of

P. ligularis pectin included the determination of moisture content, degree of esterification, acidity, methoxyl content, swelling capacity, and water retention capacity, with results summarized in

Table 5.

The moisture content of the extracted pectin was significantly lower than the maximum limit of 12.0% established for commercial pectin [

34,

35], highlighting the efficiency of the lyophilization process. Such a low moisture level enhances physicochemical stability and minimizes the risk of microbial deterioration during storage [

35,

36]. The acidity percentage fell within the range reported for moderately acidic pectins (0.3–1.0%), indicating that

P. ligularis pectin exhibits moderate acidity. This parameter is influenced by galacturonic acid content, degree of esterification, and extraction conditions, particularly pH and processing temperature [

21].

The methoxyl content confirmed that

P. ligularis pectin is classified as high-methoxyl pectin (>7% methoxyl, DE >50%) [

37]. Such classification is associated with strong gelling capacity in acidic media with high sugar concentrations, which is advantageous for both food and cosmetic applications [

38]. In cosmetics, these properties contribute to the formation of stable gels with suitable viscosity and spreadability, while also enabling the creation of a protective film on the skin that enhances water retention and improves sensory perception.

The polymer also demonstrated excellent water absorption and swelling capacities, with a swelling value of 12.46 ± 0.01 mL/g and a water retention capacity of 12.26 ± 0.01%. These values reflect a highly hydrophilic structure, indicating a polymeric network with functional groups readily available for interaction with water. Such features are beneficial for applications requiring moisture stabilization or the development of viscous, film-forming systems [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

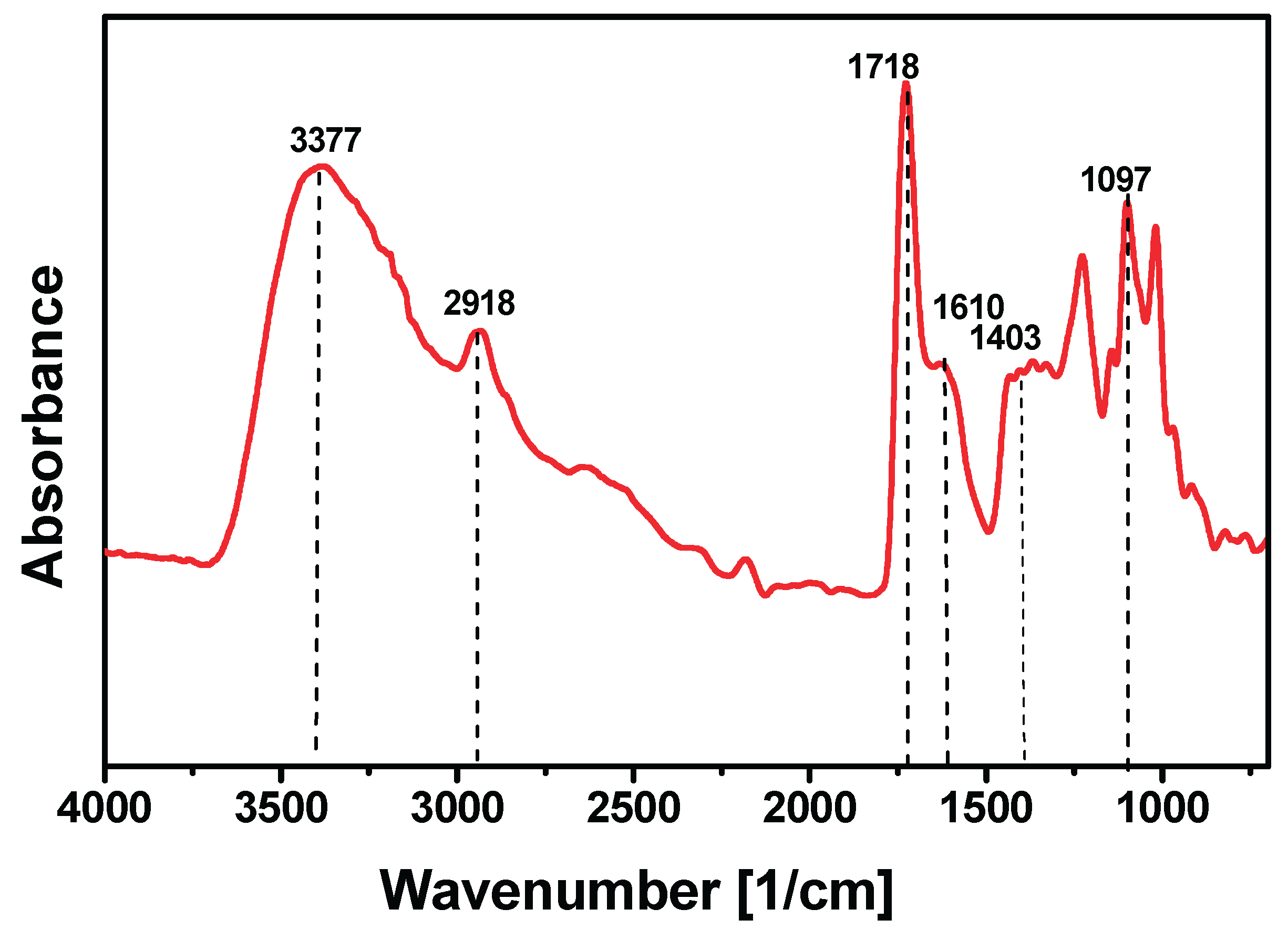

The FT-IR spectrum of

P. ligularis pectin (

Figure 1) exhibited a broad band at 3377 cm⁻¹ corresponding to –OH stretching, partly from polysaccharide hydroxyl groups and absorbed water. The band at 2918 cm⁻¹ was assigned to CH, CH₂, and CH₃ stretching vibrations of the methyl esters in galacturonic acid [

40]. A strong peak at 1718 cm⁻¹ was attributed to ester groups (COOCH₃), whose intensity indicated high methoxyl content, corroborating the NaOH titration results. The band at 1610 cm⁻¹ was associated with –OH stretching, the peak at 1403 cm⁻¹ with symmetric stretching of –COO⁻ and CH₃ groups, and absorptions between 1015–1100 cm⁻¹ with C–O vibrations [

41]. These findings are consistent with previous studies on pectins from Passifloraceae species, which display similar spectral profiles with variations in relative peak intensities due to differences in extraction method, processing conditions, and plant fraction used (peel or mesocarp) [

42].

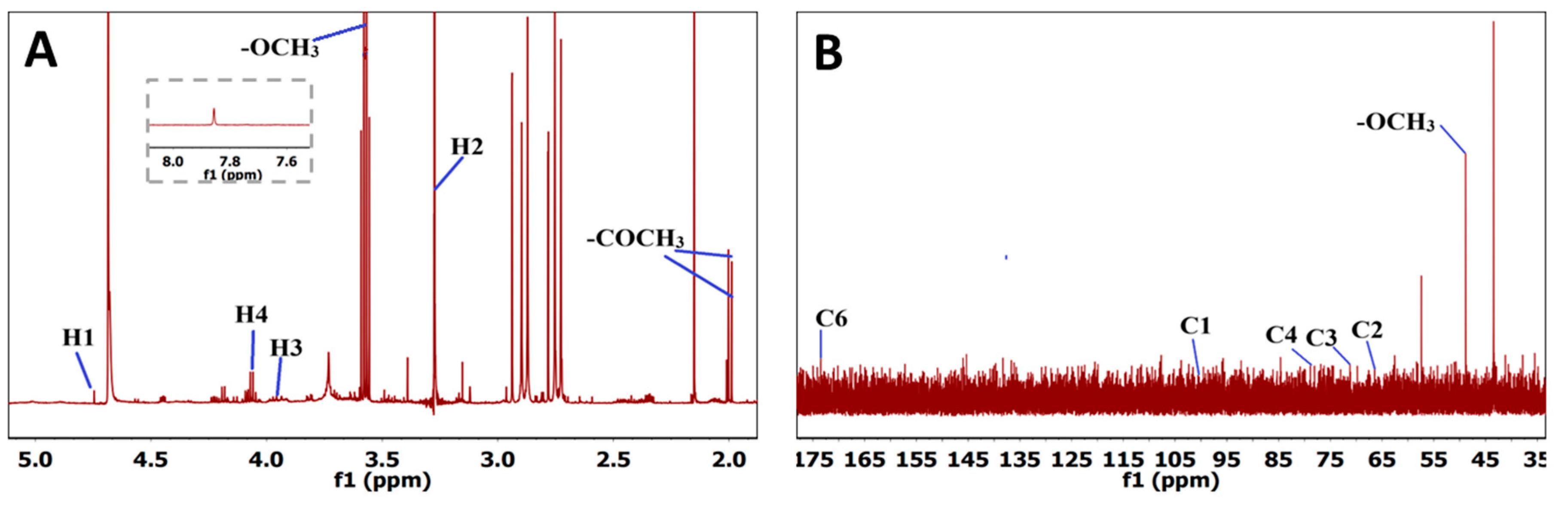

¹H NMR analysis (

Figure 2A) revealed a sharp signal at 3.57 ppm, assigned to the –OCH₃ protons of esterified galacturonic acid, reinforcing the classification as high-methoxyl pectin. Four characteristic signals were identified for D-GalA protons: H-1 at 4.75 ppm, H-2 at 3.29 ppm, H-3 at 3.93 ppm, and H-4 at 4.05 ppm, consistent with previous reports. Weak peaks at 1.98 and 2.08 ppm corresponded to O-acetyl groups (–COCH₃). A minor resonance at 7.86 ppm was attributed to residual phenolic compounds [

43], which are common in Passiflora extracts due to the peel’s richness in flavonoids and polyphenols [

37]. The ¹³C NMR spectrum (

Figure 2B) showed a strong peak at 57.14 ppm assigned to the methyl carbons linked to galacturonic acid carboxyl groups, along with characteristic signals at 100.40, 67.76, 71.10, 78.51, and 173.04 ppm for C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, and C-6 of D-GalA, respectively [

39,

44].

Overall, the physicochemical and structural profile of P. ligularis pectin (low moisture, high methoxyl content, and moderate acidity) confirms its classification as a high-methoxyl pectin with strong gelling potential. The combination of excellent swelling, water-binding capacity, and gel-forming properties suggests broad applicability, ranging from food systems that require gel stability and moisture control to cosmetic formulations designed to enhance moisturizing, viscosity, and sensory attributes.

3.4. Cosmetic Gel Formulations and Preliminary Stability

To identify the most stable formulation, a preliminary physical and sensory stability study was conducted on eight cosmetic gels designed with different gelling systems and pH ranges. Distinct behavioral patterns were observed under stress conditions of heating, refrigeration, time, and light exposure (

Table 3). The results of the physicochemical and organoleptic characteristics of the evaluated formulations are summarized in

Table 6.

In the initial centrifugation test (day 1), all formulations were physically stable, with no evidence of phase separation, indicating good initial resistance to mechanical forces simulating accelerated aging. However, differences among formulations became more evident under extreme storage conditions. At elevated temperatures (40 °C), the formulation prepared exclusively with pectin and no carbomer (F1), as well as those containing guar gum (F5 and F6), showed a marked loss of viscosity accompanied by sensory changes such as alterations in color and odor. These results suggest that these gelling systems alone do not provide a sufficiently robust matrix to resist thermal degradation, likely due to the disruption of the polymeric network.

In contrast, formulations containing carbomer at pH ≥ 6.5 (particularly F7 and F8) demonstrated superior thermal resistance. These samples more consistently preserved their organoleptic characteristics, including viscosity, color, and odor, with less deterioration under heat stress, indicating improved colloidal stability when carbomer is adequately neutralized.

Cold storage (2–8 °C) also revealed critical challenges. Refrigeration generally induced clumping or precipitation in most formulations, negatively impacting texture and spreadability. Formulations F2, F3, and F4, which contained carbomer at slightly acidic pH (6.0–6.5), were the most affected, showing decreased viscosity, reduced odor intensity, and pH fluctuations. This finding reinforces the observation that slightly acidic pH values can compromise the integrity of polymeric systems, leading to both physical and sensory instability.

With respect to pH, most formulations remained within the cosmetically acceptable range (4.5–6.5). However, significant fluctuations were observed in formulations with higher pH values (F7 and F8), indicating lower compatibility and formulation control under these conditions. This is particularly relevant since pH influences both gel stability and the safety/tolerability of the final product.

Olfactory analysis showed a generalized loss of aromatic intensity (citrus, fruity, and honey notes) under both hot and cold stress conditions. Nevertheless, formulations F7 and F8 preserved their olfactory profile more effectively, an important attribute for consumer perception and product freshness. Similarly, texture and ease of application were severely compromised in guar gum-based gels (F5 and F6), which tended to leave residues on the skin or became excessively fluid after stress cycles. In contrast, F7 and F8 maintained a stable, homogeneous sensory profile without clumping or loss of spreadability, even at the end of the observation period.

Among these, formulation F8 can be considered the most robust and sensorially acceptable, as it combined physical stability, favorable thermal performance, and positive sensory perception under simulated storage conditions (

Table 6 and

Table 7). For this reason, it was selected for photostability testing under simulated light exposure. After two hours, noticeable darkening, the formation of a denser and more elastic texture, and visible volume loss were observed, changes consistent with radiation-induced degradation, likely involving ascorbic acid and the gelling system. These results indicate that the formulation is photosensitive, highlighting the need for opaque or UV-protective packaging, as well as storage instructions to avoid direct sunlight, in order to preserve integrity and efficacy during consumer use [

45].

4. Conclusions

The methodological strategy implemented allowed the optimization of the pectin extraction process from Passiflora ligularis residues, demonstrating that the use of citric acid as a solvent, in combination with microwave-assisted extraction at 50 °C for 15 minutes, maximizes yield while preserving the physicochemical properties of the biopolymer. This condition not only showed reproducibility but also favored the recovery of high-methoxyl pectins, suitable for cosmetic applications due to their proven moisturizing capacity associated with excellent water retention. The factorial design and ANOVA analysis confirmed that the extraction method was the most influential factor, establishing a robust basis for future production scaling and applications in sustainable natural products. Preliminary stability tests on moisturizing formulations enabled the selection of a final version (Formulation 8) that met criteria of homogeneity, physical stability, acceptable rheological behavior, and skin compatibility. This formulation maintained its organoleptic characteristics, viscosity, and pH within optimal ranges under thermal and environmental stress conditions, without phase separation or sensory deterioration. The incorporation of extracted pectins as a gelling agent proved functional and effective, positioning this biomolecule as a viable, natural-origin cosmetic ingredient. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of P. ligularis pectin as a multifunctional biopolymer for cosmetic applications, combining gelling capacity, water retention, and consumer-acceptable sensory attributes. Future studies should address long-term stability, scalability of the extraction process, and clinical evaluations to further validate its effectiveness and safety in topical formulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. M.-G.; methodology, J.C.M.-G, D.T. M.-C., M.C. R.-Z., P.A. C.-P. and E. M.-H.; formal analysis, J.C.M.-G, D.T. M.-C., M.C. R.-Z., P.A. C.-P. and E. M.-H.; investigation, M.C. R.-Z., P.A. C.-P. and E. M.-H.; data curation, J.C. M.-G. and D.T. M.-C.; writing-original draft, M.C. R.-Z., P.A. C.-P. and E. M.-H.; writing-review and editing, J.C. M.-G. and D.T. M.-C.; supervision, J.C. M.-G. and D.T. M.-C.; project administration, J.C.M.-G; funding acquisition, J.C.M.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out with the financial support of the University of Antioquia Foundation, Vice-Rectorate of Research and RedSIN of the University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia within the framework of the Ideación 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the teaching laboratories of Phytochemistry, Cosmetics, and Pharmaceutical Technology at the University of Antioquia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.C.; Ma, S.H.; Chang, Y.T.; Chen, C.C. Clinical Evaluation of Skin Aging: A Systematic Review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2025, 139, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, T.; Moran, H.; Vu, P.; Maddern, G.; Wagstaff, M. Commonly Recommended Moisturising Products: Effect on Transepidermal Water Loss and Hydration in a Scar Model. Burns 2025, 51, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.; Xiong, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Shen, J. A Dehydratable and Rapidly Rehydratable Hydrogel for Stable Storage and On-Demand Moisturizing Delivery. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2025, 726, 138102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Perez, Y.; Puertas-Mejia, M.A.; Mejia-Giraldo, J.C. Marine Macroalgae: A Source of Chemical Compounds with Photoprotective and Antiaging Capacity—an Updated Review. J Appl Pharm Sci 2021, 11, 001–011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, J.; Lin, L.; Zheng, G. Extraction, Moisturizing Activity and Potential Application in Skin Cream of Akebia Trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz Polysaccharide. Ind Crops Prod 2023, 197, 116613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouémazong, E.D.; Christiaens, S.; Shpigelman, A.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. The Emulsifying and Emulsion-Stabilizing Properties of Pectin: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2015, 14, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, A.; Winkler, C.; Carle, R.; Endress, H.; Rentschler, C.; Neidhart, S. Processes Involving Selective Precipitation for the Recovery of Purified Pectins from Mango Peel. Carbohydr Polym 2017, 174, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koubala, B.B.; Kansci, G.; Mbome, L.I.; Crépeau, M.J.; Thibault, J.F.; Ralet, M.C. Effect of Extraction Conditions on Some Physicochemical Characteristics of Pectins from “Améliorée” and “Mango” Mango Peels. Food Hydrocoll 2008, 22, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Hernandez, J.C.; Taborda-Ocampo, G.; González-Correa, C.H. Folin-Ciocalteu Reaction Alternatives for Higher Polyphenol Quantitation in Colombian Passion Fruits. Int J Food Sci 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardanega, R.; Fuentes, F.S.; Palma, J.; Bugueño-Muñoz, W.; Cerezal-Mezquita, P.; Ruiz-Dominguéz, M.C. Extraction of Valuable Compounds from Granadilla (Passiflora Ligularis Juss) Peel Using Pressurized Fluids Technologies. Sustain Chem Pharm 2023, 34, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, D.; Fernandes, T.A.; Sulis, P.M.; Gonçalves, R.; Sepúlveda R, M.; Silva Frederico, M.J.; Aragon, M.; Ospina, L.F.; Costa, G.M.; Silva, F.R.M.B. Cellular Target of Isoquercetin from Passiflora Ligularis Juss for Glucose Uptake in Rat Soleus Muscle. Chem Biol Interact 2020, 330, 109198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardanega, R.; Fuentes, F.S.; Palma, J.; Bugueño-Muñoz, W.; Cerezal-Mezquita, P.; Ruiz-Domínguez, M.C. Valorization of Granadilla Waste (Passiflora Ligularis, Juss.) by Sequential Green Extraction Processes Based on Pressurized Fluids to Obtain Bioactive Compounds. J Supercrit Fluids 2023, 194, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, G.E.; Púa, A.L.; Alba, D.D. De; Pión, M.M. Extracción y Caracterización de Pectina de Mango de Azúcar ( Mangifera Indica L .) Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Sugar Mango ( Mangifera Indica L .). 2017.

- Maxwell, E.G.; Belshaw, N.J.; Waldron, K.W.; Morris, V.J. Pectin - An Emerging New Bioactive Food Polysaccharide. Trends Food Sci Technol 2012, 24, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas de Oliveira, C.; Giordani, D.; Lutckemier, R.; Gurak, P.D.; Cladera-Olivera, F.; Ferreira Marczak, L.D. Extraction of Pectin from Passion Fruit Peel Assisted by Ultrasound. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2016, 71, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.C.; Benites, E.A.; Carlos, J.; Gomero, M. Extracción y Caracterización de Pectinas Obtenidas a Partir de Frutos de La Biodiversidad Peruana Extraction and Characterization of Pectins in Several Types of Fruits of the Peruvian Biodiversity.

- Dranca, F.; Vargas, M.; Oroian, M. Physicochemical Properties of Pectin from Malus Domestica ‘Fălticeni’ Apple Pomace as Affected by Non-Conventional Extraction Techniques. Food Hydrocoll 2020, 100, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodsamran, P.; Sothornvit, R. Microwave Heating Extraction of Pectin from Lime Peel: Characterization and Properties Compared with the Conventional Heating Method. Food Chem 2019, 278, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ma, X.; Jiang, P.; Hu, L.; Zhi, Z.; Chen, J.; Ding, T.; Ye, X.; Liu, D. Characterization of Pectin from Grapefruit Peel: A Comparison of Ultrasound-Assisted and Conventional Heating Extractions. Food Hydrocoll 2016, 61, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.S.; Muruganandam, L.; Ganesh Moorthy, I. Pectin from Fruit Peel: A Comprehensive Review on Various Extraction Approaches and Their Potential Applications in Pharmaceutical and Food Industries. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2025, 9, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentería-Ortega, M.; Colín-Alvarez, M. de L.; Gaona-Sánchez, V.A.; Chalapud, M.C.; García-Hernández, A.B.; León-Espinosa, E.B.; Valdespino-León, M.; Serrano-Villa, F.S.; Calderón-Domínguez, G. Characterization and Applications of the Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Passiflora Tripartita Var. Mollissima. Membranes (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. yi; Liao, J. song; Qi, J. ru; Jiang, W. xin; Yang, X. quan Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Pectin-Rich Dietary Fiber Prepared from Citrus Peel. Food Hydrocoll 2021, 110, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission CosIng - Cosmetics Ingredients Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/advanced (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria Guía de Estabilidad de Productos Cosméticos; 2005; pp. 1–52;

- ISO - International Standards Organization ISO/TR 18811:2018. Cosmetics — Guidelines on the Stability Testing of Cosmetic Products; 2028; pp. 1–16;

- Pablo Díaz-Castillo, J.; Jhoana Mier Giraldo, H.; Fernando Sánchez, M.; Nuñez Hernandez, G.; Lucia Camargo Gómez, C.; Janneth Moyano Bonilla Profesional Especializado, L. Estudios de Estabilidad de Productos Cosméticos Recomendaciones Para El Desarrollo de Supervisión y Coordinación: Programa de Calidad Para El Sector Cosméticos-Safe+. Consultor Nacional Calidad Cosméticos, Programa Safe+ de ONUDI Investigación y Escritura; Colombia, 2018; pp. 1–90;

- Nadar, C.G.; Arora, A.; Shastri, Y. Sustainability Challenges and Opportunities in Pectin Extraction from Fruit Waste. ACS Engineering Au 2022, 2, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; Lee, H.V.; Juan, J.C.; Phang, S.-M. Production of New Cellulose Nanomaterial from Red Algae Marine Biomass Gelidium Elegans. Carbohydr Polym 2016, 151, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapo, B.M. Biochemical Characteristics and Gelling Capacity of Pectin from Yellow Passion Fruit Rind as Affected by Acid Extractant Nature. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Rolin, G.B. Seymour, J.P.K. Pectins and Their Manipulation; Blackwell.; 2002.

- Liew, S.Q.; Chin, N.L.; Yusof, Y.A. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Passion Fruit Peels. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 2014, 2, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Robinson, J.P.; Binner, E.R. Current Status of Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Pectin. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 473. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah, M.; Hasibuan, I.M.; Misran, E.; Maulina, S. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Pectin Extraction from Cocoa Pod Husk. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriani, R.; Legowo, A.M.; Susanti, S. Characteristics of Pectin Isolated from Mango ( Mangifera Indica ) and Watermelon ( Citrullus Vulgaris ) Peel. 2012, 4, 31–34. [CrossRef]

- Susanti, S.; Legowo, A.M.; Nurwantoro; Silviana; Arifan, F. Comparing the Chemical Characteristics of Pectin Isolated from Various Indonesian Fruit Peels. Indonesian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 21, 1057–1062. [CrossRef]

- Reichembach, L.H.; de Oliveira Petkowicz, C.L. Extraction and Characterization of a Pectin from Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Pulp with Gelling Properties. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 245, 116473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; An, F.; He, H.; Geng, F.; Song, H.; Huang, Q. Structural and Rheological Characterization of Pectin from Passion Fruit (Passiflora Edulis f. Flavicarpa) Peel Extracted by High-Speed Shearing. Food Hydrocoll 2021, 114, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia-Rivera, S.; Herrera-Pool, I.E.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Lizardi-Jiménez, M.A.; García-Cruz, U.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C.; Cervantes-Uc, J.M.; Pacheco, N. Kinetic, Thermodynamic, Physicochemical, and Economical Characterization of Pectin from Mangifera Indica L. Cv. Haden Residues. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ai, B.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, D.; Sheng, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, S. Passion Fruit Peel-Derived Low-Methoxyl Pectin: De-Esterification Methods and Application as a Fat Substitute in Set Yogurt. Carbohydr Polym 2025, 347, 122664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, M.; Akpınar, Ö. Valorisation of Fruit By-Products: Production Characterization of Pectins from Fruit Peels. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2019, 115, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, A.; Środa-Pomianek, K.; Górniak, A.; Wikiera, A.; Cyprych, K.; Malik, M. Structural Determination of Pectins by Spectroscopy Methods. Coatings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N.; Montanez, J.C.; Brandelli, A.; Espinoza-Perez, J.D.; Renard, C.M.G.C. Pectin from Passion Fruit Fiber and Its Modification by Pectinmethylesterase. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition 2010, 15, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, K.; Zhong, Y.; Cui, W.; Jia, X.; Yin, L. Synthesis, Characterization and Application of Sugar Beet Pectin-Ferulic Acid Conjugates in the Study of Lipid, DNA and Protein Oxidation. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 307, 141358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; He, H.; Huang, Q.; An, F.; Song, H. Flash Extraction Optimization of Low-Temperature Soluble Pectin from Passion Fruit Peel (Passiflora Edulis f. Flavicarpa) and Its Soft Gelation Properties. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2020, 123, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.; Chourasiya, Y.; Maheshwari, R.; Tekade, R.K. Current Developments in Excipient Science: Implication of Quantitative Selection of Each Excipient in Product Development. Basic Fundamentals of Drug Delivery 2019, 29–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).