Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

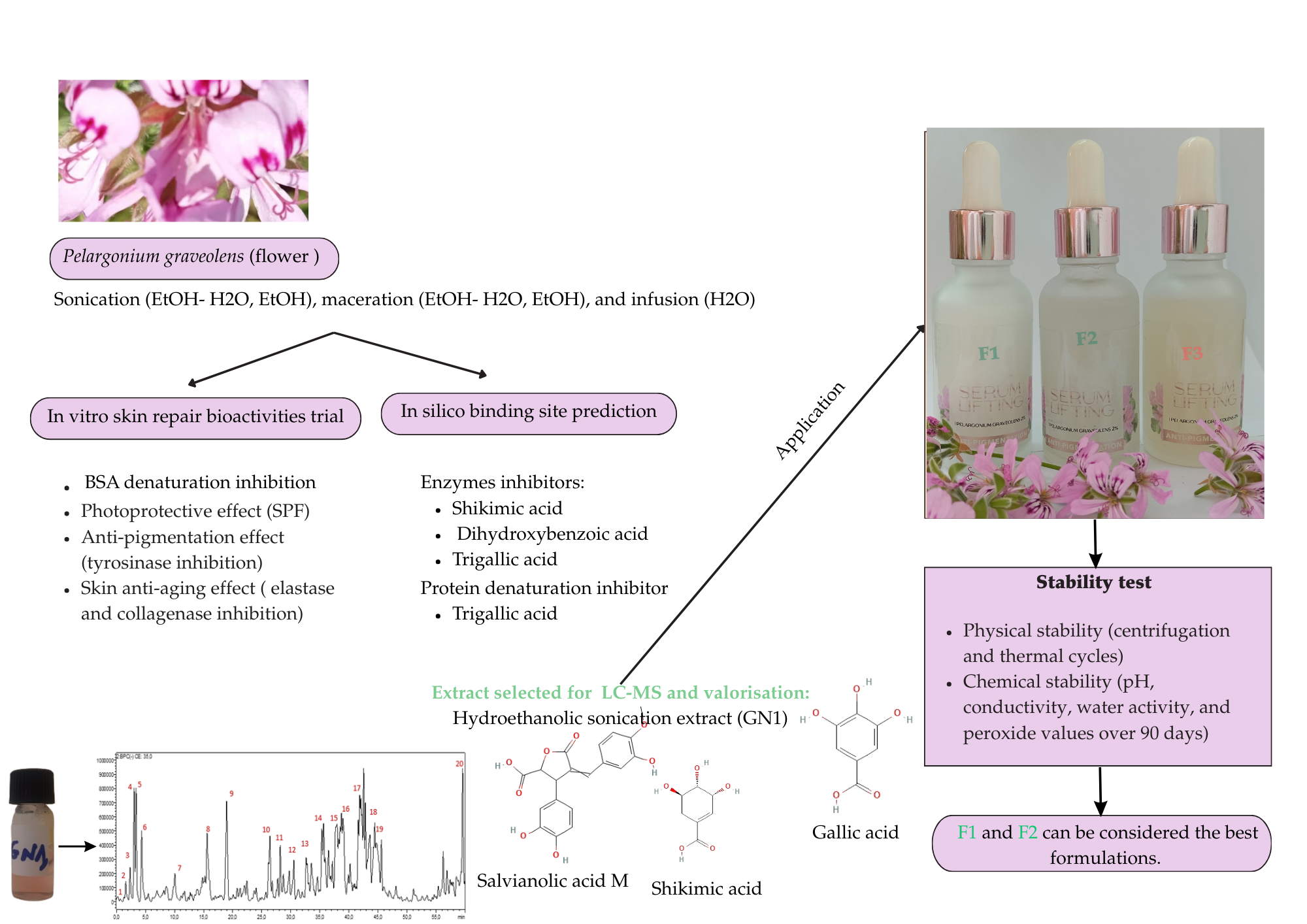

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Extraction

2.2. Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) Denaturation

2.3. Enzyme Inhibitory Activities

2.3.1. Tyrosinase

2.3.2. Elastase

2.3.3. Collagenase

2.4. UV-B Absorption: Photoprotective Effect

2.5. Interfacial and Surface Tension Characteristics

2.6. Phytochemical Analysis Using HPLC-PDA-MS/MS

2.7. In Silico Binding Site Prediction

2.7.1. Ligand

2.7.2. Protein

2.7.3. Glide Standard Precision (SP) Ligand Docking

2.8. Application on Aqueous Serum Formulas

2.8.1. Preparation

2.8.2. Stability

2.9. Data analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BSA Denaturation Assay

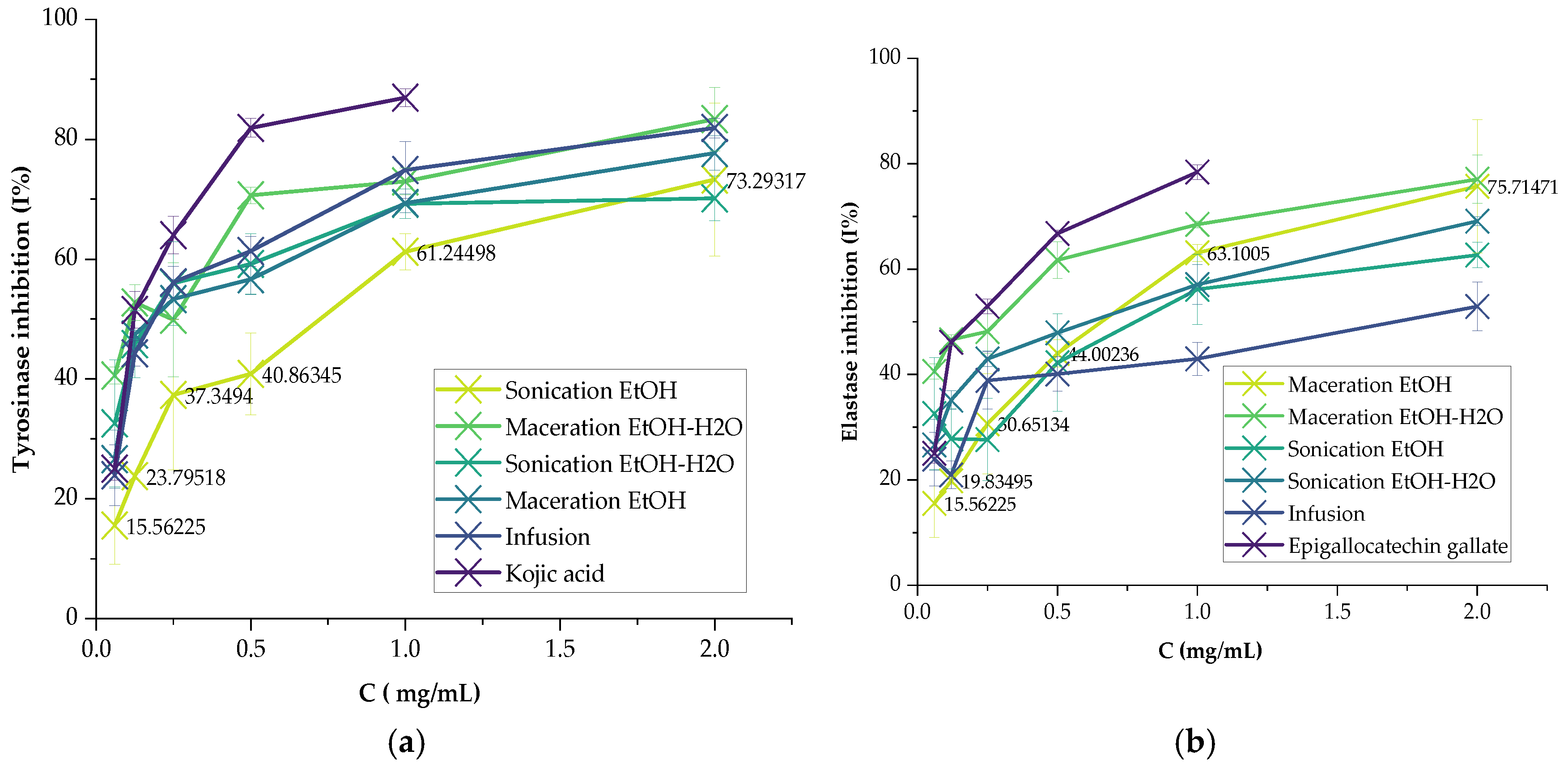

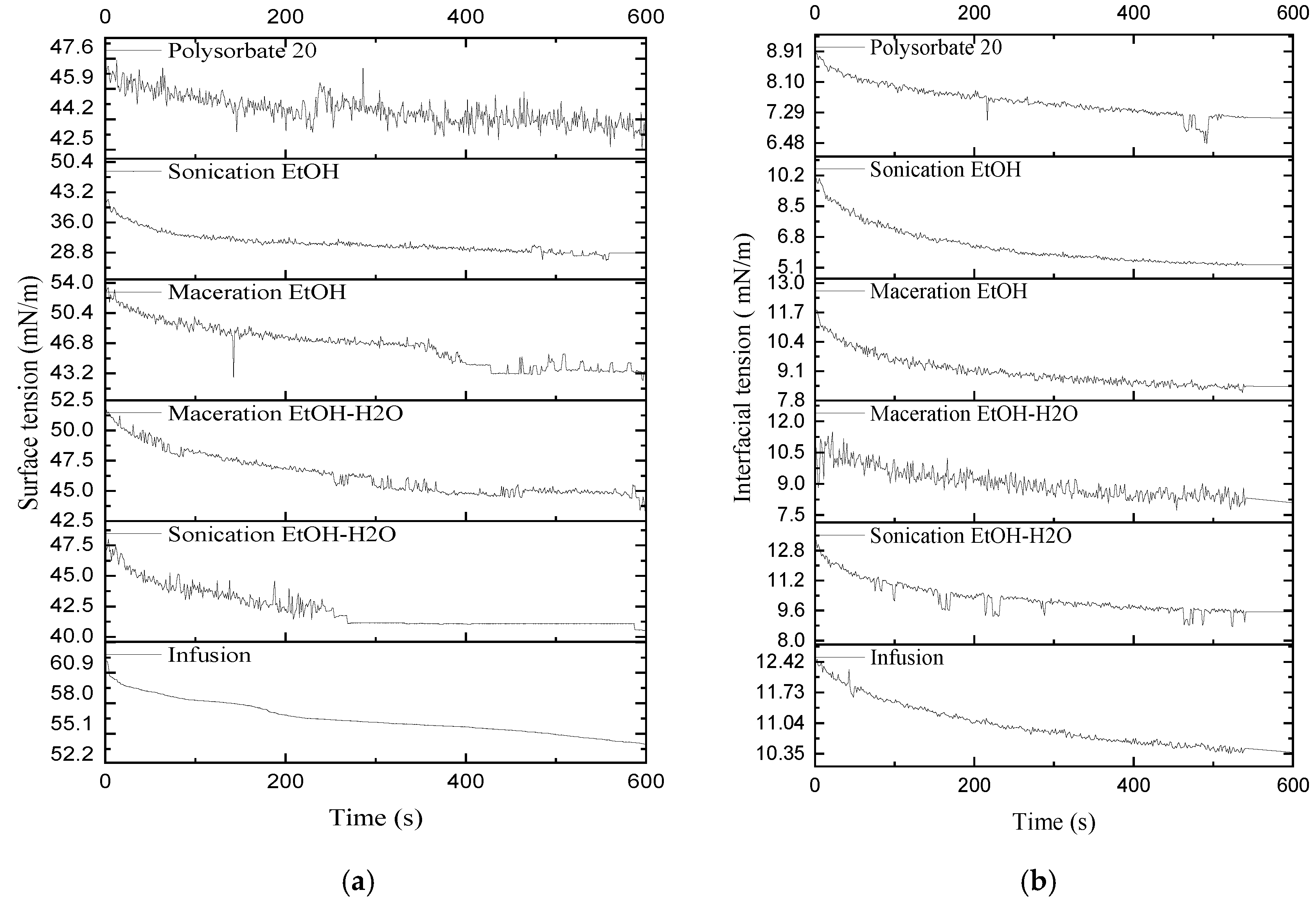

3.2. Enzyme Inhibitory Activities

3.4. Photoprotective Activity

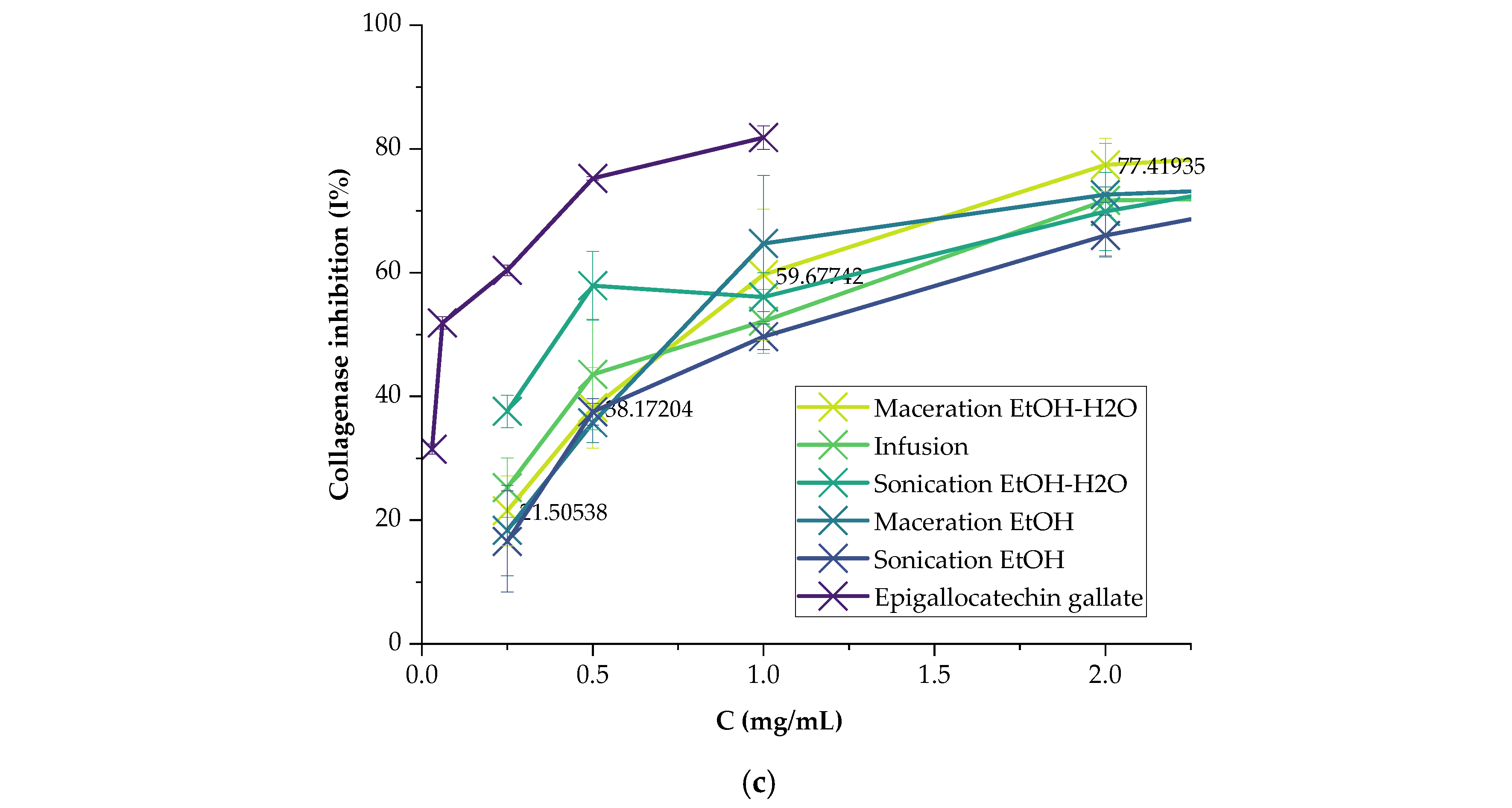

3.5. Interfacial and Surface Tension Characteristics

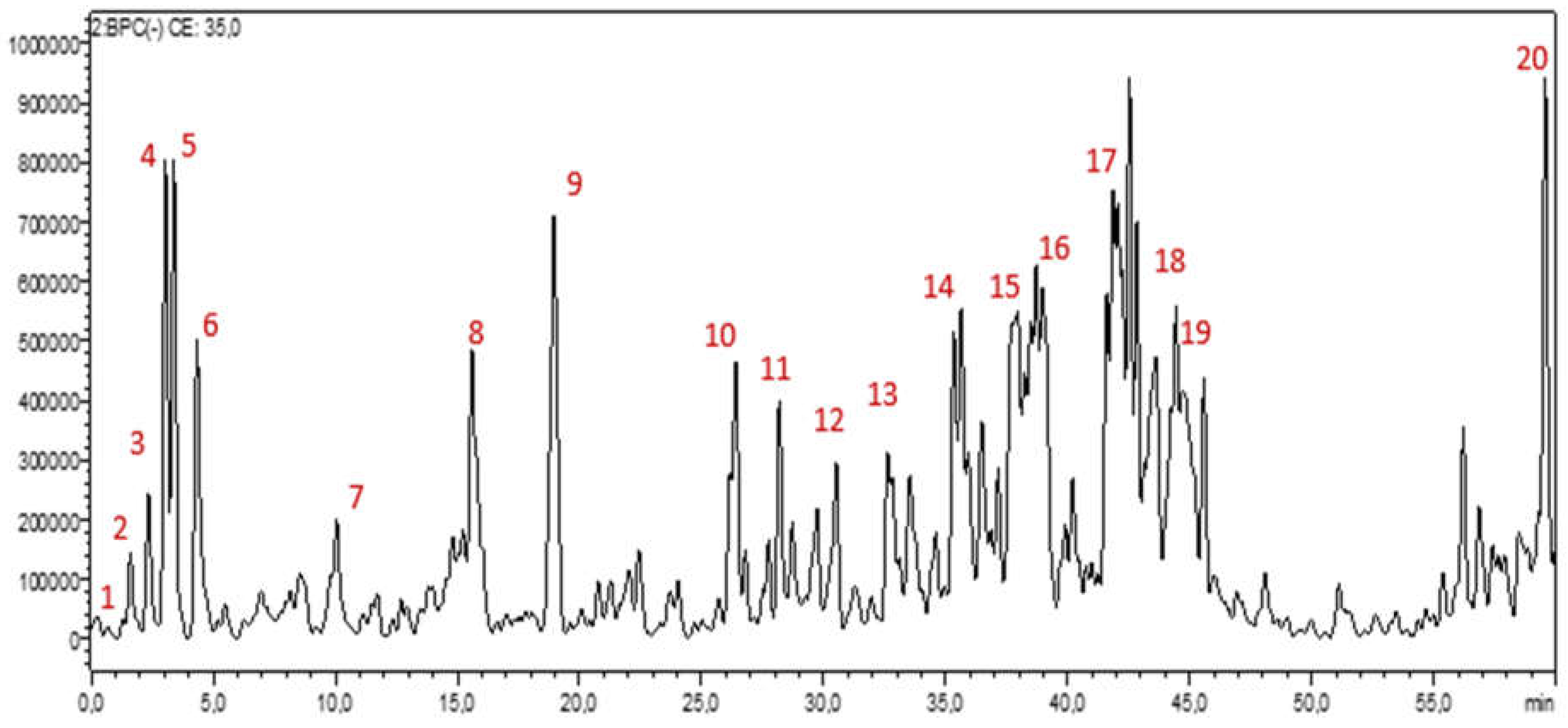

3.6. Chemical Profiling: HPLC-PDA-MS/MS

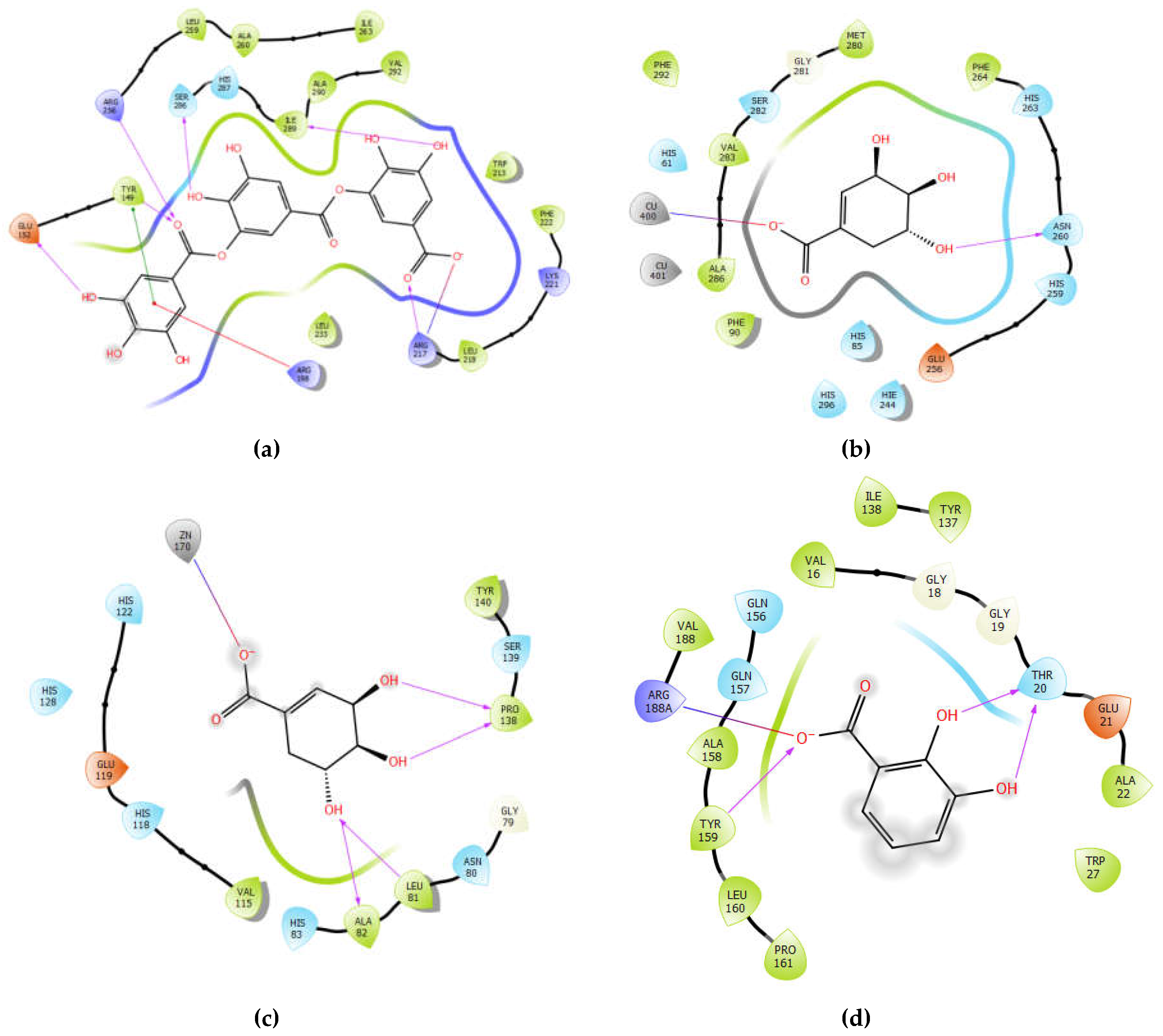

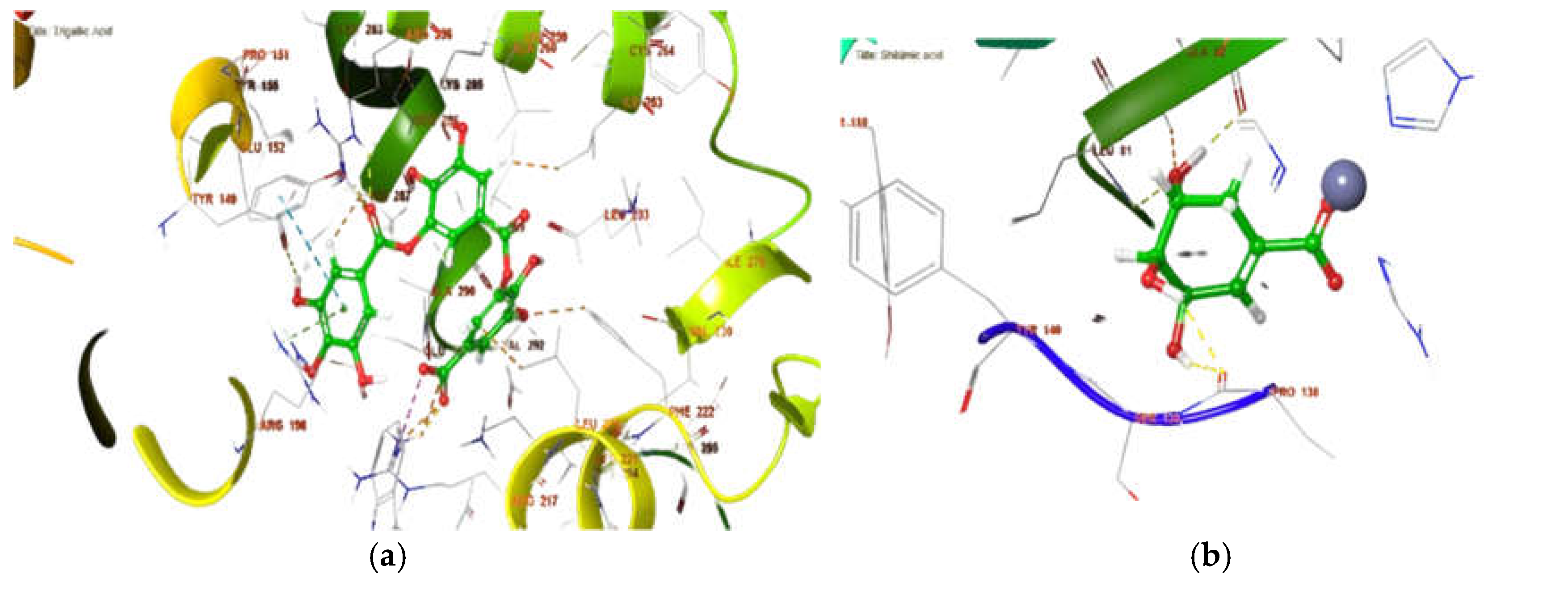

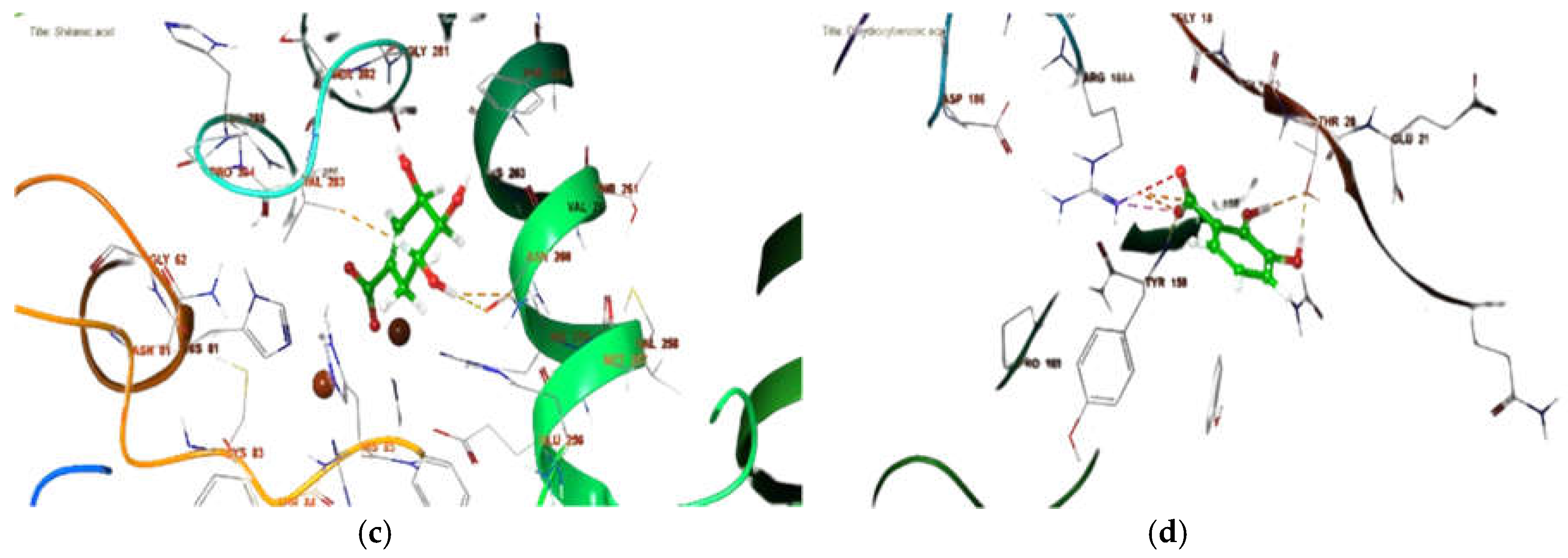

3.7. Binding Site Prediction

3.8. Application: Aqueous Serum Formulas

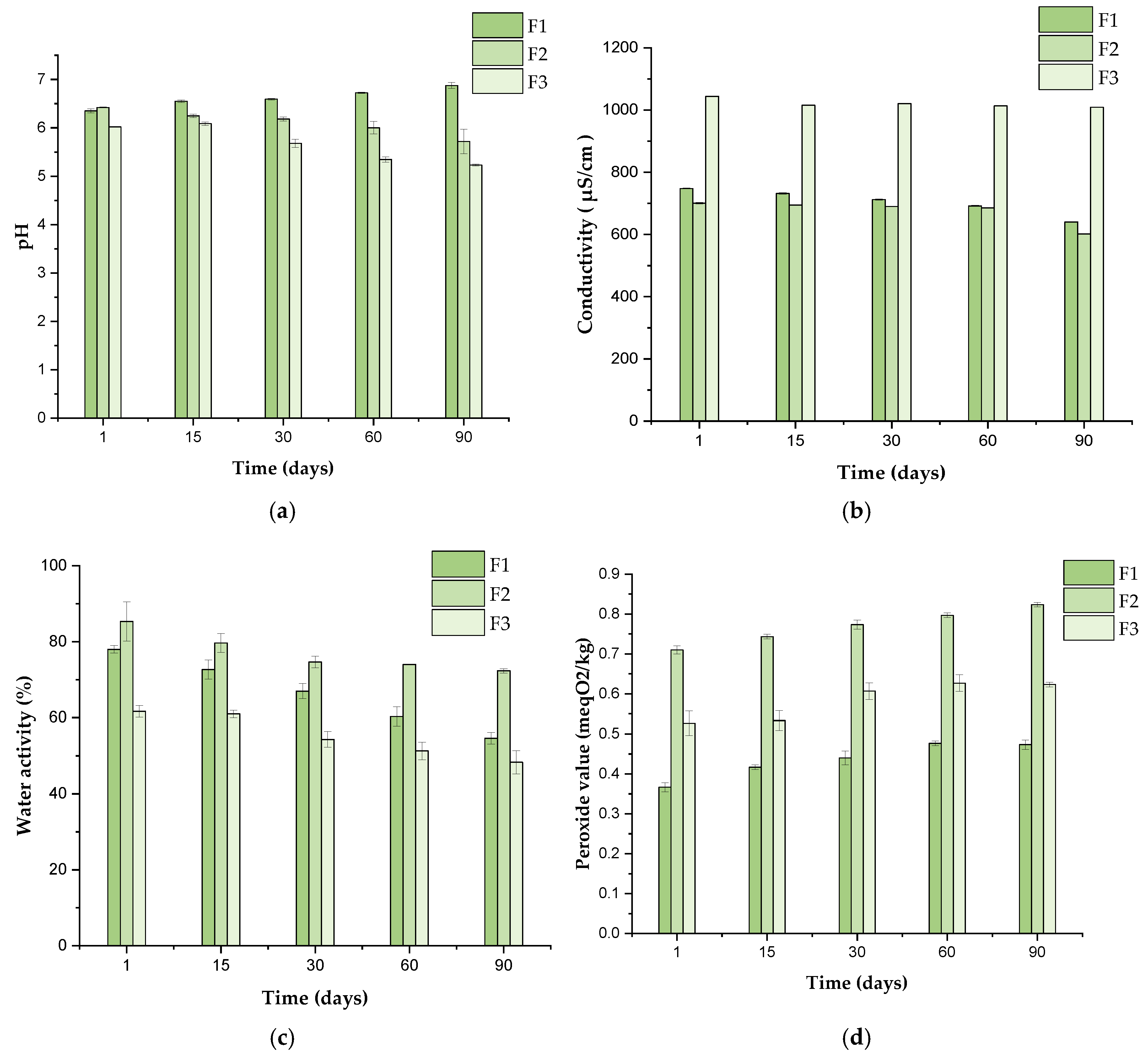

3.8.1. Stability

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, M.A. The skin. Tech. Small Anim. Wound Manag. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Elbuluk, N.; Grimes, P.; Chien, A.; Hamzavi, I.; Alexis, A.; Taylor, S.; Gonzalez, N.; Weiss, J.; Desai, S.R.; Kang, S. The Pathogenesis and Management of Acne-Induced Post-inflammatory Hyperpigmentation. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 22, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkoszka, M.; Rok, J.; Wrześniok, D. Melanin Biopolymers in Pharmacology and Medicine—Skin Pigmentation Disorders, Implications for Drug Action, Adverse Effects and Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami, A.; Hassan Khan, M.T.; Munoz-Munoz, J.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Saboury, A.A. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habachi, E.; Rebey, I.B.; Dakhlaoui, S.; Hammami, M.; Sawsen, S.; Msaada, K.; Merah, O.; Bourgou, S. Arbutus unedo: Innovative Source of Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Tyrosinase Phenolics for Novel Cosmeceuticals. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Amaral, M.N.; Reis, C.P.; Custódio, L. Marine Natural Products as Innovative Cosmetic Ingredients. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fecker, R.; Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Cocan, I.; Alexa, E.; Popescu, I.M.; Lombrea, A.; et al. Oxidative Stability and Protective Effect of the Mixture between Helianthus annuus L. and Oenothera biennis L. Oils on 3D Tissue Models of Skin Irritation and Phototoxicity. Plants 2022, 11, 2977. [Google Scholar]

- Arraiza, M.P.; Calderón-Guerrero, C.; Guillén, S.C.; Sarmiento, M.A. Industrial Uses of MAPs: Cosmetic Industry. Med. Aromat. Plants: Basics Ind. Appl. 2017, 1, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Savary, G.; Grisel, M.; Picard, C. Cosmetics and personal care products. Nat. Polym. : Ind. Tech. Appl. 2016, 219–261.

- Patil, M.; Joshi, M.; Kadam, J.; Zambare, V.; Sinha, S.; Pawar, R.; et al. Application as cosmetic bioactives of phytochemicals extracted from the post distillation biomass of geranium. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Asgarpanah, J.; Ramezanloo, F. An overview on phytopharmacology of Pelargonium graveolens L. 2015.

- El-Otmani, N.; Zeouk, I.; Hammani, O.; Zahidi, A. Analysis and Quality Control of Bio-actives and Herbal Cosmetics: The Case of Traditional Cooperatives from Fes-Meknes Region. 8, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekouaghet, A.; Boutefnouchet, A.; Bensuici, C.; Gali, L.; Ghenaiet, K.; Tichati, L. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the hydroalcoholic extract and its fractions from Leuzea conifera L. roots. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 132, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mijalli, S.H.; Mrabti, H.N.; Assaggaf, H.; Attar, A.A.; Hamed, M.; EL Baaboua, A.; El Omari, N.; El Menyiy, N.; Hazzoumi, Z.; A Sheikh, R.; et al. Chemical Profiling and Biological Activities of Pelargonium graveolens Essential Oils at Three Different Phenological Stages. Plants 2022, 11, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S.; Mahdi, I.; Drissi, B.; Fahsi, N.; Bouissane, L.; Sobeh, M. Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast.: Volatile constituents, antioxidant, antidiabetic and wound healing activities of its essential oil. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Uyama, H.; Kobayashi, S. Inhibition effects of (+)-catechin–aldehyde polycondensates on proteinases causing proteolytic degradation of extracellular matrix. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 320, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, J.d.S.; Breder, M.N.R.; Mansur, M.C.d.A.; Azulay, R.D. Determinaçäo do fator de proteçäo solar por espectrofotometria. An Bras Dermatol. 1986, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chebaibi, M.; Bourhia, M.; Amrati, F.E.-Z.; Slighoua, M.; Mssillou, I.; Aboul-Soud, M.A.M.; Khalid, A.; Hassani, R.; Bousta, D.; Achour, S.; et al. Salsoline derivatives, genistein, semisynthetic derivative of kojic acid, and naringenin as inhibitors of A42R profilin-like protein of monkeypox virus: in silico studies. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1445606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourabi, M.; Nouioura, G.; Touijer, H.; Baghouz, A.; El Ghouizi, A.; Chebaibi, M.; et al. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Insecticidal Properties of Chemically Characterized Essential Oils Extracted from Mentha longifolia: In Vitro and In Silico Analysis. Plants 2023, 12, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meryem, M.J.; Agour, A.; Allali, A.; Chebaibi, M.; Bouia, A. Chemical composition, free radicals, pathogenic microbes, α-amylase and α-glucosidase suppressant proprieties of essential oil derived from Moroccan Mentha pulegium: in silico and in vitro approaches. J. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2024, 1, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Taibi, M.; Rezouki, S.; Moubchir, T.; El Abdali, Y.; Mssillou, I.; El Barnossi, A.; Elbouzidi, A.; Haddou, M.; Baraich, A.; Berraaouan, D.; et al. Satureja calamintha essential oil: Chemical composition and assessing insecticidal efficacy through activity against acetylcholinesterase, chitin, juvenile hormone, and molting hormone. J. Biol. Biomed. Res. (ISSN: 3009-5522) 2025, 1, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniaich, G.; Hafsa, O.; Maliki, I.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; El Moussaoui, A.; Chebaibi, M.; et al. GC-MS characterization, in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, and in silico nadph oxidase inhibition studies of anvillea radiata essential oils. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebaibi, M.; Mssillou, I.; Allali, A.; Bourhia, M.; Bousta, D.; Gonçalves, R.F.B.; Hoummani, H.; Aboul-Soud, M.A.M.; Augustyniak, M.; Giesy, J.P.; et al. Antiviral Activities of Compounds Derived from Medicinal Plants against SARS-CoV-2 Based on Molecular Docking of Proteases. J. Biol. Biomed. Res. (ISSN: 3009-5522) 2024, 1, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.M.; Santos, L. A Potential Valorization Strategy of Wine Industry by-Products and Their Application in Cosmetics—Case Study: Grape Pomace and Grapeseed. Molecules 2022, 27, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, J.J.L.; de Oliveira, A.F.M. Exploring the therapeutic potential of Brazilian medicinal plants for anti-arthritic and anti-osteoarthritic applications: A comprehensive review. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 103064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.F.; Pereira, O.R.; Cardoso, S.M. Health-promoting effects of Thymus phenolic-rich extracts: Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.A.F.; Campos, M.L.; Irioda, A.C.; Stremel, D.P.; Trindade, A.C.L.B.; Pontarolo, R. Anti-inflammatory effect of Malva sylvestris, Sida cordifolia, and Pelargonium graveolens is related to inhibition of prostanoid production. Molecules 2017, 22, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aanachi, S.; Gali, L.; Nacer, S.N.; Bensouici, C.; Dari, K.; Aassila, H. Phenolic contents and in vitro investigation of the antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, photoprotective, and antimicrobial effects of the organic extracts of Pelargonium graveolens growing in Morocco. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Biswas, R.; Sharma, A.; Banerjee, S.; Biswas, S.; Katiyar, C. Validation of medicinal herbs for anti-tyrosinase potential. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Locatelli, M.; Carradori, S.; Mocan, A.M.; Aktumsek, A. Total phenolics, flavonoids, condensed tannins content of eight Centaurea species and their broad inhibitory activities against cholinesterase, tyrosinase, α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2016, 44, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, C. Molecular mechanisms of skin photoaging and plant inhibitors. Int. J. Green Pharm. (IJGP) 2017, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, N.S.; Torres-Obreque, K.M.; Oliveira, C.A.; Rabelo, J.; Baby, A.R.; Long, P.F.; Young, A.R.; Rangel-Yagui, C.d.O. Enzymes for dermatological use. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenauer, J.; Mäckle, S.; Sußmann, D.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Carle, R. Inhibitory effects of polyphenols from grape pomace extract on collagenase and elastase activity. Fitoterapia 2015, 101, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, Y.C.; Hu, H.-C.; Yu, S.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Korinek, M.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chang, F.-R.; Chen, Y.-J. Development on potential skin anti-aging agents of Cosmos caudatus Kunth via inhibition of collagenase, MMP-1 and MMP-3 activities. Phytomedicine 2023, 110, 154643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniz, F.S.S.; Salmas, R.E.; Emerce, E.; Cankaya, I.I.T.; Yusufoglu, H.S.; Orhan, I.E. Evaluation of collagenase, elastase and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of Cotinus coggygria Scop. through in vitro and in silico approaches. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 132, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; Hou, Y.; Ai, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Meng, X. Gallic acid: Pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Gallego, J.S.; Pedroza-Escobar, D.; Caicedo-Ortega, A.R.; Berumen-Murra, M.T.; Novelo-Aguirre, A.L.; de Sotelo-León, R.D.; et al. Human neutrophil elastase inhibitors: Classification, biological-synthetic sources and their relevance in related diseases. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 2023.

- He, H.; Li, A.; Li, S.; Tang, J.; Li, L.; Xiong, L. Natural components in sunscreens: Topical formulations with sun protection factor (SPF). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Gaivão, I. Natural Ingredients in Skincare: A Scoping Review of Efficacy and Benefits. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. J. 2023, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threskeia, A.; Sandhika, W.; Rahayu, R.P. Effect of turmeric (Curcuma longa) extract administration on tumor necrosis factor-alpha and type 1 collagen expression in UVB-light radiated BALB/c mice. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadvaja, N.; Gautam, S.; Singh, H. Natural polyphenols: a promising bioactive compounds for skin care and cosmetics. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 50, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekar, M.; Mary, J.; Sivakumar, M.; Selvam, M. Recent developments in sunscreens based on chromophore compounds and nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 2529–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taarji, N.; Bouhoute, M.; Chafai, Y.; Hafidi, A.; Kobayashi, I.; Neves, M.A.; Tominaga, K.; Isoda, H.; Nakajima, M. Emulsifying Performance of Crude Surface-Active Extracts from Liquorice Root (Glycyrrhiza Glabra). ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, C.; Dreher, J.; Helgason, T.; Tadros, T. Investigation of emulsifying properties and emulsion stability of plant and milk proteins using interfacial tension and interfacial elasticity. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 39, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhris, M.; Simmonds, M.S.; Sayadi, S.; Bouaziz, M. Chemical composition and biological activities of polar extracts and essential oil of rose-scented geranium, Pelargonium graveolens. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelouhab, K.; Guemmaz, T.; Karamać, M.; Kati, D.E.; Amarowicz, R.; Arrar, L. Phenolic composition and correlation with antioxidant properties of various organic fractions from Hertia cheirifolia extracts. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 235, 115673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezig, K.; Benkaci-Ali, F.; Foucaunier, M.L.; Laurent, S.; Umar, H.I.; Alex, O.D.; et al. HPLC/ESI-MS Characterization of Phenolic Compounds from Cnicus benedictus L. Roots: A Study of Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anti-Alzheimer's Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202300724. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, Z.-R.; Du, S.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J. Polyphenol-sodium alginate supramolecular injectable hydrogel with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory capabilities for infected wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 257, 128636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, V.; Kanika, S.; Jinu, J.; Venkateswarlu, R.; Deepa, M.; Rohini, A. 43 Phenolic Phytochemicals from Sorghum, Millets, and Pseudocereals and Their Role in Human Health. Nutriomics of Millet Crops: CRC Press. 2024; pp. 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrabadi, N.S.; Vedad, A.; Asadi, K.; Poorbagher, M.R.M.; Tabrizi, N.A.; Dorooki, K.; Sabouni, R.S.; Moghadam, M.B.; Shafaei, N.; Karimi, E.; et al. Nanoliposome-loaded phenolics from Salvia leriifolia Benth and its anticancer effects against induced colorectal cancer in mice. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2024, 71, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, M.; Tešić, Ž.; Blagojević, S. Flavonoids in Pollen. Pollen Chemistry & Biotechnology: Springer; 2024. p. 127-45.

- Elshamy, S.; Handoussa, H.; El-Shazly, M.; Mohammed, E.D.; Kuhnert, N. Metabolomic profiling and quantification of polyphenols from leaves of seven Acacia species by UHPLC-QTOF-ESI-MS. Fitoterapia 2023, 172, 105741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomphen, L.; Yamanont, P.; Morales, N.P. Flavonoid Metabolites in Serum and Urine after the Ingestion of Selected Tropical Fruits. Nutrients 2024, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunil, C.; Gowda, N.N.; Nayak, N.; Rawson, A. Unveiling the effect of processing on bioactive compounds in millets: Implications for health benefits and risks. Process. Biochem. 2024, 138, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, D.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Piórecki, N.; Sozański, T. The Health-Promoting Quality Attributes, Polyphenols, Iridoids and Antioxidant Activity during the Development and Ripening of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L. ). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Oyom, W.; Li, S.; Xie, P.; Bi, Y.; Wei, J.; George, G. Comparison of nutrient composition, phytochemicals and antioxidant activities of two large fruit cultivars of sea buckthorn in Xinjiang of China. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, X.; Chang, Y.; Ma, R.; Cao, X.; Wang, S. Dynamics of Physicochemical Characteristics, Bioactive Substances and Microbial Communities in Lycium Ruthenicum Murr. Compound Jiaosu During Spontaneous Fermentation. Compound Jiaosu During Spontaneous Fermentation.

- Kebede, I.A.; Gebremeskel, H.F.; Ahmed, A.D.; Dule, G. Bee products and their processing: a review. Pharm. Pharmacol. Int. J. 2024, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Orejon, F.L.; Huaman, J.; Lozada, P.; Ramos-Escudero, F.; Muñoz, A.M. Development and Functionality of Sinami (Oenocarpus mapora) Seed Powder as a Biobased Ingredient for the Production of Cosmetic Products. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esho, B.A.; Samuel, B.; Akinwunmi, K.F.; Oluyemi, W.M. Membrane stabilization and inhibition of protein denaturation as mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory activity of some plant species. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Dewanjee, D.; Ghosh, S.; Khatua, S.; Rapior, S. Ganoderma in skin health care: A state-of-the-art review. Ganoderma. 2024, 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Latreille, B.; Paquin, P. Evaluation of Emulsion Stability by Centrifugation with Conductivity Measurements. J. Food Sci. 1990, 55, 1666–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-OTMANI, Najlae (2025). Phytochemical profiling, enzymes inhibition, anti-inflammatory, antidermatophytes 989 activities_Raw_Data. figshare. Dataset. [CrossRef]

| F1 (INCI) | %, w/w | F2 (INCI) | %, w/w | F3 (INCI) | %, w/w |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqua | 71.5 | AQUA | 71.5 | AQUA | 71.5 |

| Xhantan gum | 0.2 | Tragacanth Gum | 0.2 | Linum usitatissimum seed extract | 0.2 |

| Sodium Benzoate | 0.3 | Sodium Benzoate | 0.3 | Sodium Benzoate | 0.3 |

| Glycerin | 7 | Glycerin | 7 | Glycerin | 7 |

| Propylene glycol | 4 | Propylene glycol | 4 | Propylene glycol | 4 |

| Myritol | 10 | Myritol | 6,5 | Myritol | 0.2 |

| Polysorbate 80 | 0.5 | Polysorbate 80 | 0.5 | Carboxymethy cellulose | 0.5 |

| Triethanolamine (50%) | Q. s | Triethanolamine (50%) | Q. s | Triethanolamine (50%) | Q. s |

| P.graveolens extract | Q. s | P.graveolens extract | Q. s | P. graveolens extract | Q. s |

| Methods | Positive Controls |

Sonication | Maceration | Infusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH- H2O | EtOH | EtOH- H2O | EtOH | H2O | ||

| SPF | 11.88 ± 2.0881 , a | 26.02 ± 0.020b | 24.33 ± 0.15b | 24.78 ± 0.127b | 25.49 ± 0.016 b | 25.56 ± 0.059b |

| BSA (IC50 mg/mL) | 0.175 ± 0.0102, a | 0.20 ± 0.031a | 0.61 ± 0.030a | 0.44 ± 0.024a | 0.38 ± 0.022a | 1.64 ± 0.111b |

| Tyrosinase (IC50 mg/mL) | 0.071 ± 0.013 3, a | 0.06 ± 0.079 a | 0.82 ± 0.306 b | 0.15 ± 0.103 a | 0.37 ± 0.017a | 0.34 ± 0.070 a |

| Elastase (IC50 mg/mL) | 0.11 ± 0.0034, a | 0.75 ± 0.011 b | 1.00 ± 0.309 b | 0.12 ± 0.100 b | 0.81 ± 0.155 b | 1.49 ± 0.243 b |

| Collagenase (IC50 mg/mL) | 0.08 ± 0.0034, a | 0.52 ± 0.104 a c | 1.46 ± 0.137 b | 0.95 ± 0.139 a c d | 1.16 ± 0.275 d | 1.09 ± 0.187 c d |

| Rt (min) | [M-H]- | MS/MS | Proposed compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.57 | 149 | 103 | Tartaric acid |

| 1.81 | 133 | 115 | Malic acid |

| 1.90 | 173 | 129 | Shikimic acid |

| 2.35 | 191 | 111 | Citric acid |

| 2.72 | 493 | 125, 169 | Gallic acid diglucoside |

| 2.83 | 331 | 125, 169 | Gallic acid glucoside |

| 4.27 | 169 | 125 | Gallic acid |

| 5.71 | 491 | 123, 167 | Vanillic acid diglucoside |

| 6.64 | 315 | 153 | Protocatechuic acid glucoside |

| 6.77 | 233 | 153 | Dihydroxybenzoic acid sulfate |

| 7.75 | 325 | 125, 169 | Gallic acid shikimate |

| 7.87 | 153 | 108 | Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

| 7.88 | 305 | 125, 179 | Gallocatechin |

| 9.48 | 483 | 169 | Digallic acid glucoside |

| 9.60 | 395 | 153, 315 | Protocatechuic acid sulfoglucoside |

| 10.54 | 371 | 167, 197 | Quinylsyringic acid/ Salvianolic Acid M |

| 11.24 | 341 | 135, 161, 179 | Caffeic acid glucoside |

| 12.34 | 321 | 125, 169 | Digallic acid |

| 13.08 | 295 | 125, 169 | Gallic acid triacetate |

| 15.22 | 329 | 167 | Vanillic acid glucoside |

| 18.78 | 581 | 287, 447 | Eriodictyol glucoside pentoside |

| 20.59 | 633 | 169, 301, 463 | Unknown |

| 21.04 | 467 | 153, 169 | Dihydroxybenzoic acid galloyl glucoside |

| 22.19 | 197 | 125, 169 | Syringic Acid |

| 25.97 | 473 | 169, 321 | Trigallic Acid |

| 26.12 | 479 | 271, 317 | Myricetin glucoside |

| 26.41 | 625 | 271, 317 | Myricetin glucoside rhamnoside |

| 27.85 | 595 | 271, 301 | Quercetin glucoside pentoside |

| 28.95 | 449 | 301, 317 | Myricetin pentoside |

| 29.49 | 463 | 301, 317 | Myricetin rhamnoside |

| 29.49 | 609 | 271, 301 | Quercetin rutinoside |

| 30.35 | 463 | 301 | Quercetin glucoside |

| 30.55 | 593 | 285 | Kaempferol glucoside rhamnoside |

| 31.17 | 579 | 285 | Kaempferol glucoside pentoside |

| 32.07 | 565 | 271, 301 | Quercetin dipentoside |

| 32.93 | 433 | 271, 301 | Quercetin pentoside |

| 34.53 | 447 | 255, 285 | Kaempferol glucoside |

| 34.57 | 623 | 301, 315 | Isorhamnetin glucoside rhamnoside |

| 34.74 | 287 | 259 | Eriodictyol |

| 35.32 | 545 | 125, 169, 241 | Unknown |

| 37.85 | 621 | 125, 169, 241 | Unknown |

| 39.86 | 697 | 169, 317, 469, 617 | Unknown |

| 41.01 | 773 | 169, 241, 317, 493, 617 | Unknown |

| 44.17 | 285 | 151 | Kaempferol |

| 45.61 | 447 | 315 | Isorhamnetin pentoside |

| 50.70 | 315 | 315 | Isorhamnetin |

| 56.19 | 313 | 283, 295 | Cirsimaritin |

| Compounds | Glide gscore (Kcal/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tyrosinase (PDB :2Y9X) | Collagenase (PDB : 2TCL) | Elastase (PDB: 7EST) | BSA (PDB: 6QS9) |

|

| Caffeic acid glucoside | -6.22 | -5.817 | -4.292 | -5.667 |

| Cirsimaritin | - | -5.281 | -4.2 | -5.885 |

| Citric acid | -6.071 | -7.165 | -4.832 | -5.014 |

| Digallic acid | -7.277 | -7.704 | -4.121 | -6.361 |

| Dihydroxybenzoic acid | -7.966 | -8.532 | -5.381 | -6.235 |

| Eriodictyol | -6.814 | -7.657 | -4.705 | -6.041 |

| Gallic acid | -7.518 | -7.828 | -4.924 | -6.137 |

| Gallic acid glucoside | -7.219 | -5.804 | -4.092 | -5.949 |

| Gallic acid triacetate | -6.181 | -7.367 | -4.538 | -7.001 |

| Gallocatechin | -6.822 | -8.548 | -3.562 | -6.703 |

| Isorhamnetin | -5.979 | -6.308 | -4.61 | -6.111 |

| Isorhamnetin glucoside | -5.443 | -5.924 | -4.094 | |

| Kaempferol | -5.862 | -5.79 | -5.191 | -5.961 |

| Kaempferol glucoside | -5.358 | -6.028 | -4.73 | -6.224 |

| Malic acid | -6.109 | -7.032 | -4.567 | -4.036 |

| Myricetin glucoside | -4.35 | -6.365 | -4.339 | -6.844 |

| Myricetin pentoside | -6.985 | -7.242 | -5.264 | -5.91 |

| Myricetin rhamnoside | -6.351 | -7.265 | -5.144 | -6.497 |

| Protocatechuic acid glucoside | -7.372 | -8.622 | -4.799 | -6.951 |

| Quercetin glucoside | -4.465 | -6.918 | -4.764 | -5.873 |

| Quercetin rutinoside | -5.329 | -8.184 | -5.195 | - |

| Salvianolic Acid M | -5.324 | -7.943 | -4.808 | -7.665 |

| Shikimic acid | -8.116 | -9.1 | -4.887 | -6.097 |

| Syringic Acid | -7.905 | -7.828 | -4.267 | -6.368 |

| Tartaric acid | -5.709 | -7.519 | -4.459 | -4.283 |

| Trigallic Acid | -7.004 | -9.146 | -5.046 | -8.321 |

| Vanillic acid | -7.661 | -7.96 | -4.217 | -6.725 |

| Vanillic acid glucoside | -6.983 | -8.22 | -4.516 | -5.504 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).