Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Responses

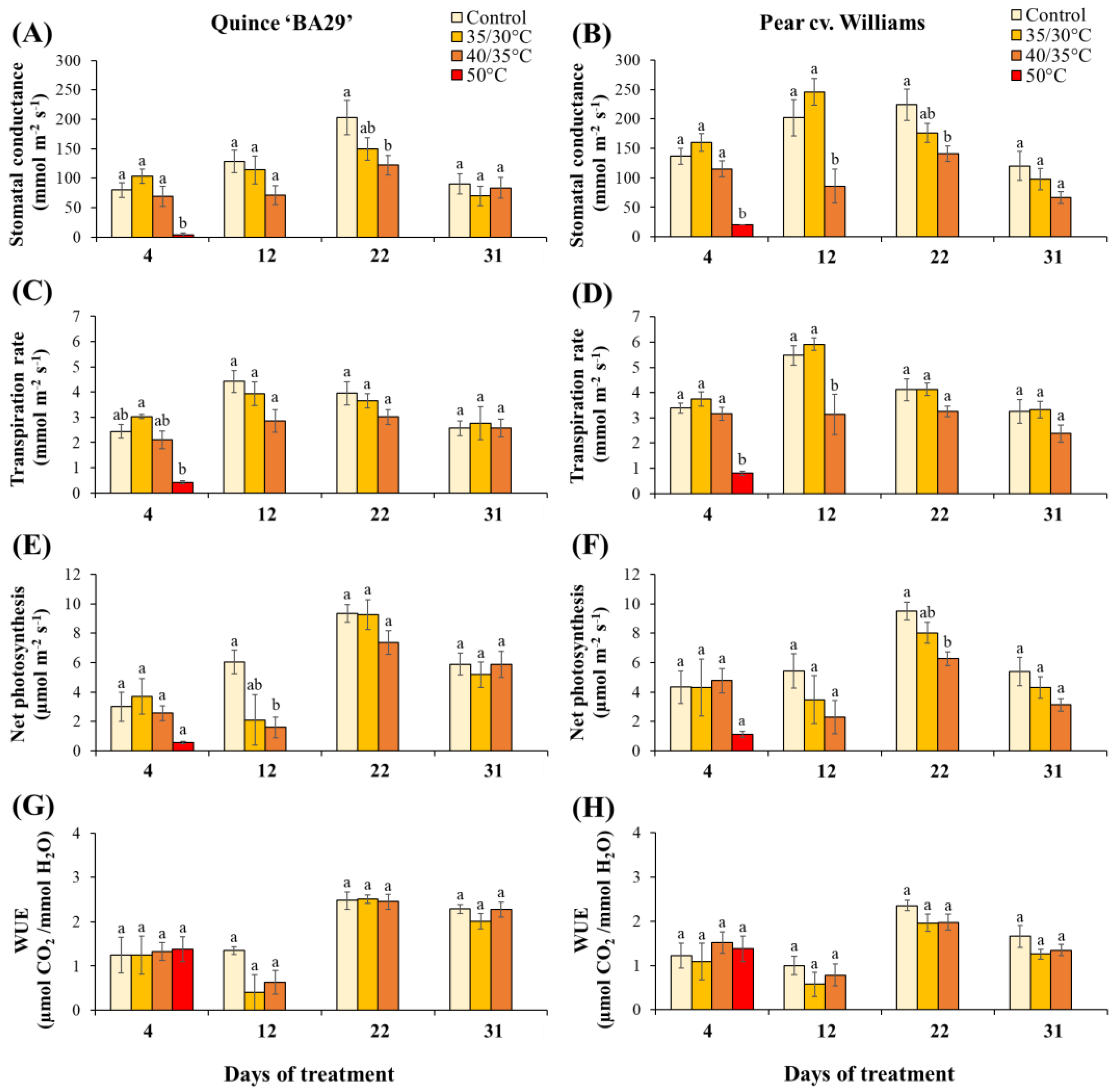

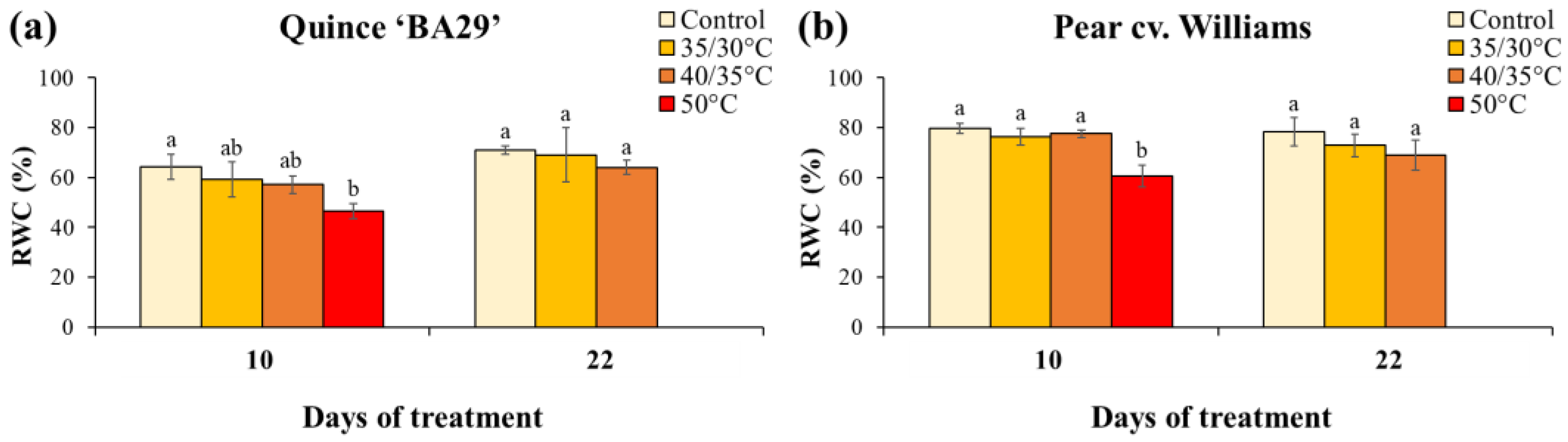

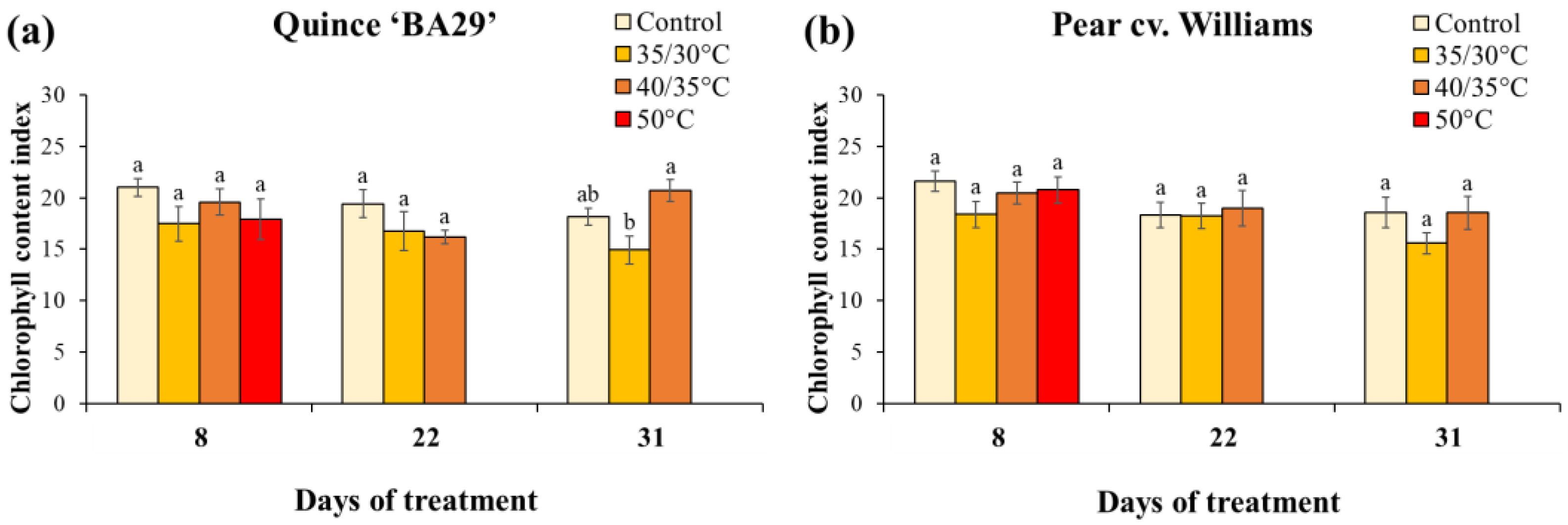

3.2. Physiological Responses

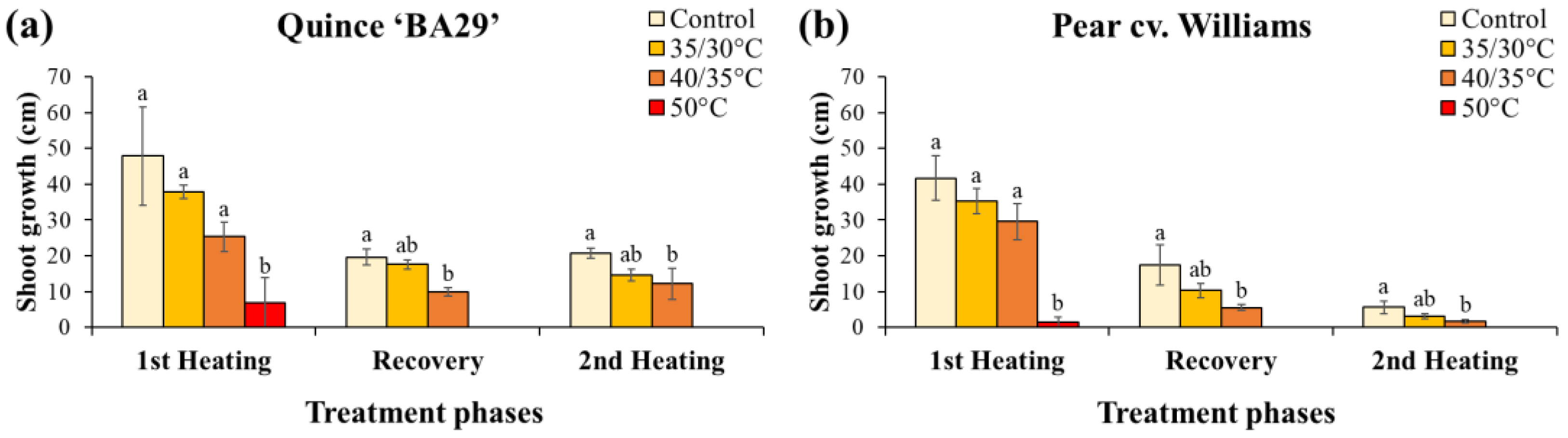

3.3. Growth Responses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameter | Factor | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 4 | Day 12 | Day 22 | Day 31 | ||

| gs | S | < 0.001*** | < 0.001*** | 0.210 ns | 0.379 ns |

| T | < 0.001*** | < 0.001*** | < 0.001*** | 0.234 ns | |

| S × T | 0.693 ns | 0.057 ns | 0.985 ns | 0.329 ns | |

| E | S | 0.002 ** | 0.01 * | 0.305 ns | 0.310 ns |

| T | < 0.001*** | < 0.001*** | 0.014 * | 0.342 ns | |

| S × T | 0.758 ns | 0.241 ns | 0.915 ns | 0.480 ns | |

| Pn | S | 0.126 ns | 0.617 ns | 0.251 ns | 0.054 ns |

| T | 0.043 * | 0.008 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.342 ns | |

| S × T | 0.806 ns | 0.705 ns | 0.615 ns | 0.329 ns | |

| WUE | S | 0.981 ns | 0.751 ns | 0.010 * | < 0.001*** |

| T | 0.837 ns | 0.042 * | 0.582 ns | 0.167 ns | |

| S × T | 0.953 ns | 0.526 ns | 0.619 ns | 0.625 ns | |

| Factor | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 10 | Day 22 | |

| S | < 0.001*** | 0.115 ns |

| T | < 0.001*** | 0.101 ns |

| S × T | 0.851 ns | 0.895 ns |

| Factor | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 8 | Day 22 | Day 31 | |

| S | 0.180 ns | 0.357 ns | 0.733 ns |

| T | 0.093 ns | 0.521 ns | 0.017 * |

| S × T | 0.872 ns | 0.310 ns | 0.479 ns |

| Factor | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Heating | Recovery | 2nd Heating | |

| S | 0.828 ns | < 0.001*** | 0.001 ** |

| T | < 0.001*** | < 0.001*** | < 0.001*** |

| S × T | 0.832 ns | 0.949 ns | 0.958 ns |

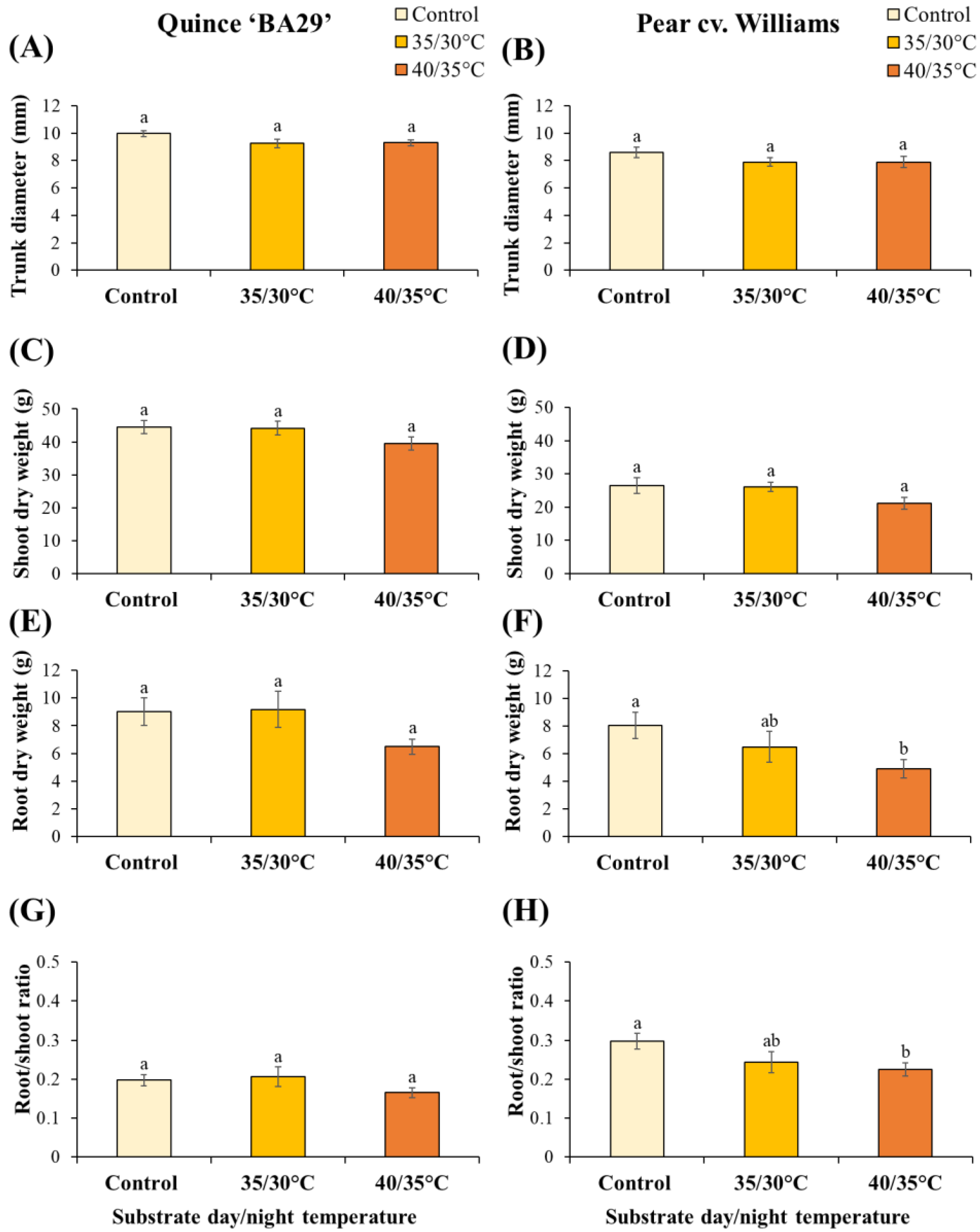

| Response | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S | T | S × T | |

| Trunk diameter | <0.001 *** | 0.051 ns | 0.997 ns |

| Shoot dry weight | <0.001 *** | 0.018 * | 0.994 ns |

| Root dry weight | 0.027 * | 0.003 ** | 0.688 ns |

| Root/shoot ratio | <0.001 *** | 0.012 * | 0.414 ns |

References

- Allan, R.P.; Arias, P.A.; Berger, S.; Canadell, J.G.; Cassou, C.; Chen, D.; Cherchi, A.; Connors, S.L.; Coppola, E.; Cruz, F.A.; Diongue-Niang, A. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bita, C.E.; Gerats, T. Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment: scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Manjeet, M. Heat stress effects in fruit crops: A review. Agric. Rev. 2020, 41, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, F.; Darbyshire, R.; Farrell, A.; Lakso, A.; Lawson, J.; Meinke, H.; Nelson, G.; Stöckle, C. Assessing temperature-based adaptation limits to climate change of temperate perennial fruit crops. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2557–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat tolerance in plants: An overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenweider, P.; Günthardt-Goerg, M.S. Diagnosis of abiotic and biotic stress factors using the visible symptoms in foliage. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 137, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, D.M.; Kim, S.-H.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Läderach, P. Response of perennial horticultural crops to climate change. Hortic. Rev. 2014, 41, 47–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Duan, D.; Zheng, W.; Huang, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Mao, K.; Ma, F. MdVQ37 overexpression reduces basal thermotolerance in transgenic apple by affecting transcription factor activity and salicylic acid homeostasis. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtai, W.; Asensio, D.; Kadison, A.E.; Schwarz, M.; Raifer, B.; Andreotti, C.; Hammerle, A.; Zanotelli, D.; Haas, F.; Niedrist, G.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Tagliavini, M. Soil water availability modulates the response of grapevine leaf gas exchange and PSII traits to a simulated heat wave. Plant Soil 2024, 501, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotelli, D.; Montagnani, L.; Andreotti, C.; Tagliavini, M. Water and carbon fluxes in an apple orchard during heat waves. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 134, 126460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Hidaka, T.; Fukamachi, H. Heat tolerance in leaves of tropical fruit crops as measured by chlorophyll fluorescence. Sci. Hortic. 1996, 67, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Q.; Xi, X.; He, Y.; Yin, X.; Jiang, A. Effect of short-time high-temperature treatment on the photosynthetic performance of different heat-tolerant grapevine cultivars. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, H. Soil, vine, climate change; the challenge of predicting soil carbon changes and greenhouse gas emissions in vineyards and is the 4 per 1000 goal realistic? OENO One 2022, 56, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namaghi, M.N.; Davarynejad, G.H.; Ansary, H.; Nemati, H.; Feyzabady, A.Z. Effects of mulching on soil temperature and moisture variations, leaf nutrient status, growth and yield of pistachio trees (Pistacia vera L.). Sci. Hortic. 2018, 241, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.M.; Egipto, R.; Aguiar, F.C.; Marques, P.; Nogales, A.; Madeira, M. The role of soil temperature in Mediterranean vineyards in a climate change context. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1145137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadish, S.V.K.; Way, D.A.; Sharkey, T.D. Plant heat stress: Concepts directing future research. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1992–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóia Júnior, R.S.; do Amaral, G.C.; Pezzopane, J.E.M.; Toledo, J.V.; Xavier, T.M.T. Ecophysiology of C3 and C4 plants in terms of responses to extreme soil temperatures. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2018, 30, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Fujita, M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9643–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, B.L.; Burke, J.J. Soil temperature and root growth. Hortic. Rev. 1998, 22, 247–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlova, R.; Boer, D.; Hayes, S.; Testerink, C. Root plasticity under abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckathorn, S.A.; Giri, A.; Mishra, S.; Bista, D. Heat stress and roots. In Climate Change and Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Tuteja, N., Gill, S., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Weinheim, Germany, 2013; pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, V.; Guizzardi, M.; Dradi, D.; Crescenzi, S.; Monaci, E.; Chiari, G.; Anconelli, S.; Bortolotti, P.P.; Nannini, R.; Casoli, L.; Neri, D. Root architecture affected by pear degeneration in relation to rootstock and soil characteristics. Acta Hortic. 2024, 1403, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, D.; Crescenzi, S.; Massetani, F.; Manganaris, G.A.; Giorgi, V. Current trends and future perspectives towards sustainable and economically viable peach training systems. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 305, 111348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverigiani, S.; Kelderer, M.; Neri, D. Growth of ‘M9’ apple root in five Central Europe replanted soils. Plant Root 2014, 8, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverigiani, S.; Franzina, M.; Neri, D. Effect of soil condition on apple root development and plant resilience in intensive orchards. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappel, F.; Granger, A.; Hrotkó, K.; Schuster, M. Cherry. In Fruit Breeding; Badenes, M.L., Byrne, D.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 459–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, M.; Pallotti, G.; Bortolotti, P.P.; Casoli, L.; Nannini, R.; Dradi, D.; Giorgi, V.; Neri, D. Pear degeneration in Emilia Romagna Region. Acta Hortic. 2024, 1403, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musacchi, S.; Iglesias, I.; Neri, D. Training systems and sustainable orchard management for European pear (Pyrus communis L.) in the Mediterranean area: A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondini, L.; Sansavini, S. European Pear. In Fruit Breeding. Handbook of Plant Breeding; Badenes, M., Byrne, D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 8, pp. 441–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Buwalda, J.G.; Green, T.G.A.; Clark, C.J. Effect of oxygen supply and temperature at the root on the physiology of kiwifruit vines. New Phytol. 1989, 113, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D. L.; Ruter, J. M.; Martin, C. A. Characterization and impact of supraoptimal root-zone temperatures in container-grown plants. HortScience 2015, 50, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Gao, F.; Ni, Z.; Lin, L.; Deng, Q.; Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Xia, H. Melatonin improves heat tolerance in kiwifruit seedlings through promoting antioxidant enzymatic activity and glutathione S-transferase transcription. Molecules 2018, 23, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Gong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, M.; Bai, J.; Zhang, S.; Lu, H. Effects of root-zone warming, nitrogen supply and their interactions on root-shoot growth, nitrogen uptake and photosynthetic physiological characteristics of maize. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramcharan, C.; Ingram, D.L.; Nell, T.A.; Barrett, J.E. Fluctuations in leaf carbon assimilation as affected by root-zone temperature and growth environment. HortScience 1991, 26, 1200–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ahammed, G.J.; Zhou, G.; Xia, X.; Zhou, J.; Shi, K.; Yu, J.; Zhou, Y. Unraveling main limiting sites of photosynthesis under below- and above-ground heat stress in cucumber and the alleviatory role of luffa rootstock. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Gao, Z.; Du, Y. Effects of long-term high temperatures in the root zone on the physiological characteristics of grapevine leaves and roots: Implications for viticulture practices. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, A. Effects of high temperatures at the root zone and the graft union on the development of temperate fruit trees. In Temperate Fruit Crops in Warm Climates; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Xu, J. Root carbon and protein metabolism associated with heat tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3455–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, A.; Heckathorn, S.; Mishra, S.; Krause, C. Heat stress decreases levels of nutrient-uptake and-assimilation proteins in tomato roots. Plants 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).