Submitted:

27 September 2025

Posted:

05 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Silica Nanoparticle Synthesis

2.3.1. Synthesis of Pristine Silica Particles by Sol Gel Method

2.3.2. Synthesis of Unmodified Silica Particles by the Stober Method

2.3.3. Sulfonation of Silica Particles

3. Results for the Nanoparticles Calcinated for 2 h

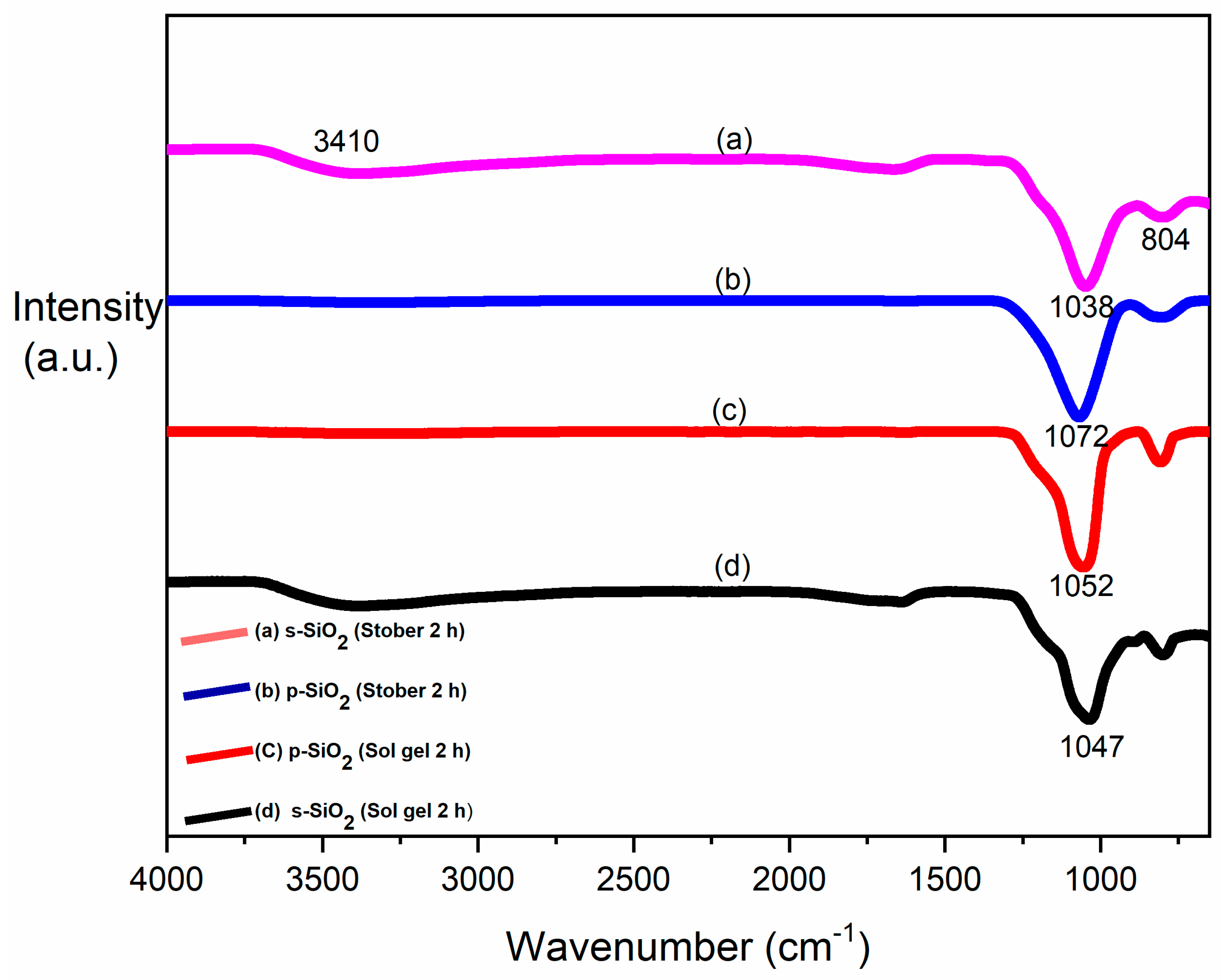

3.1. FTIR Results

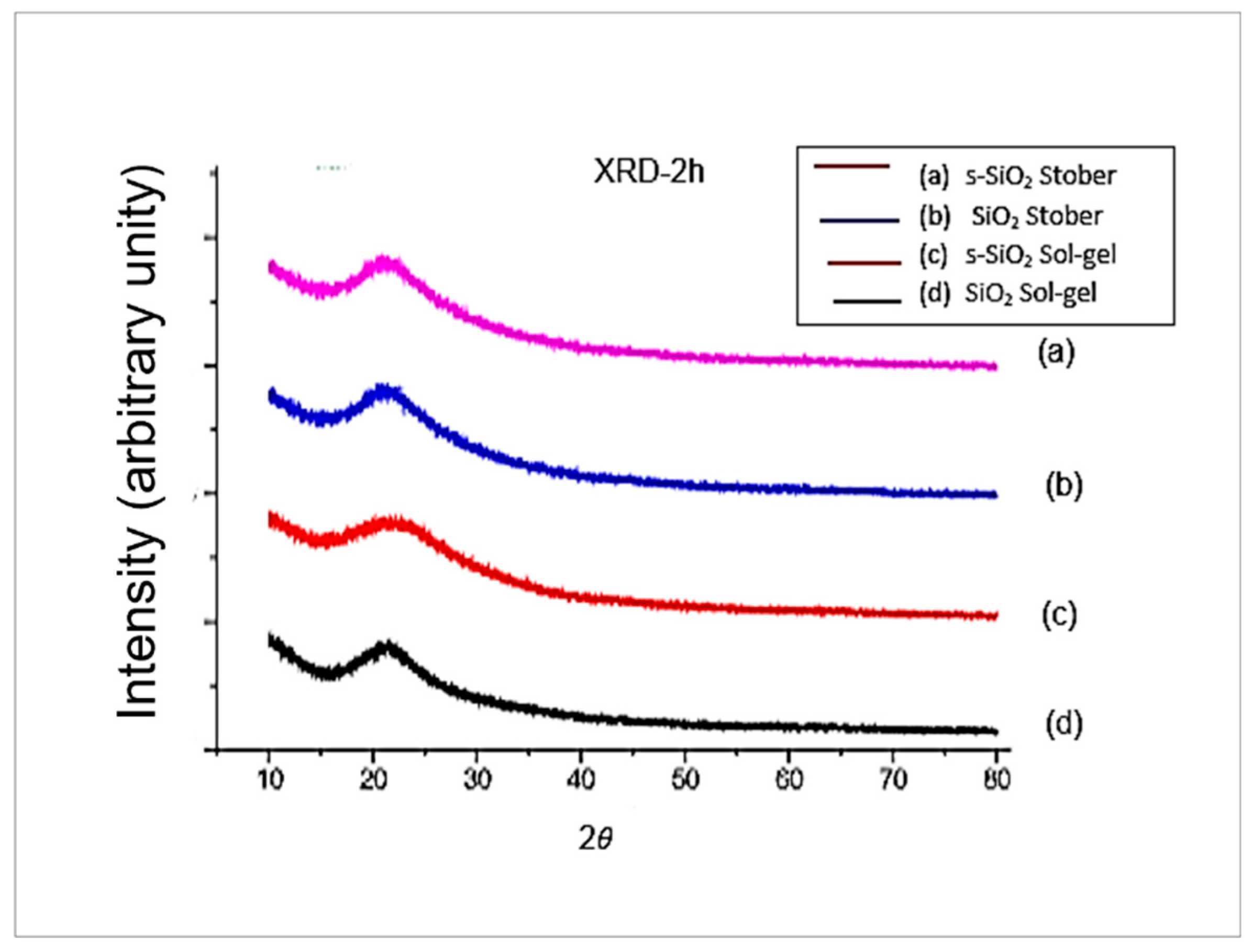

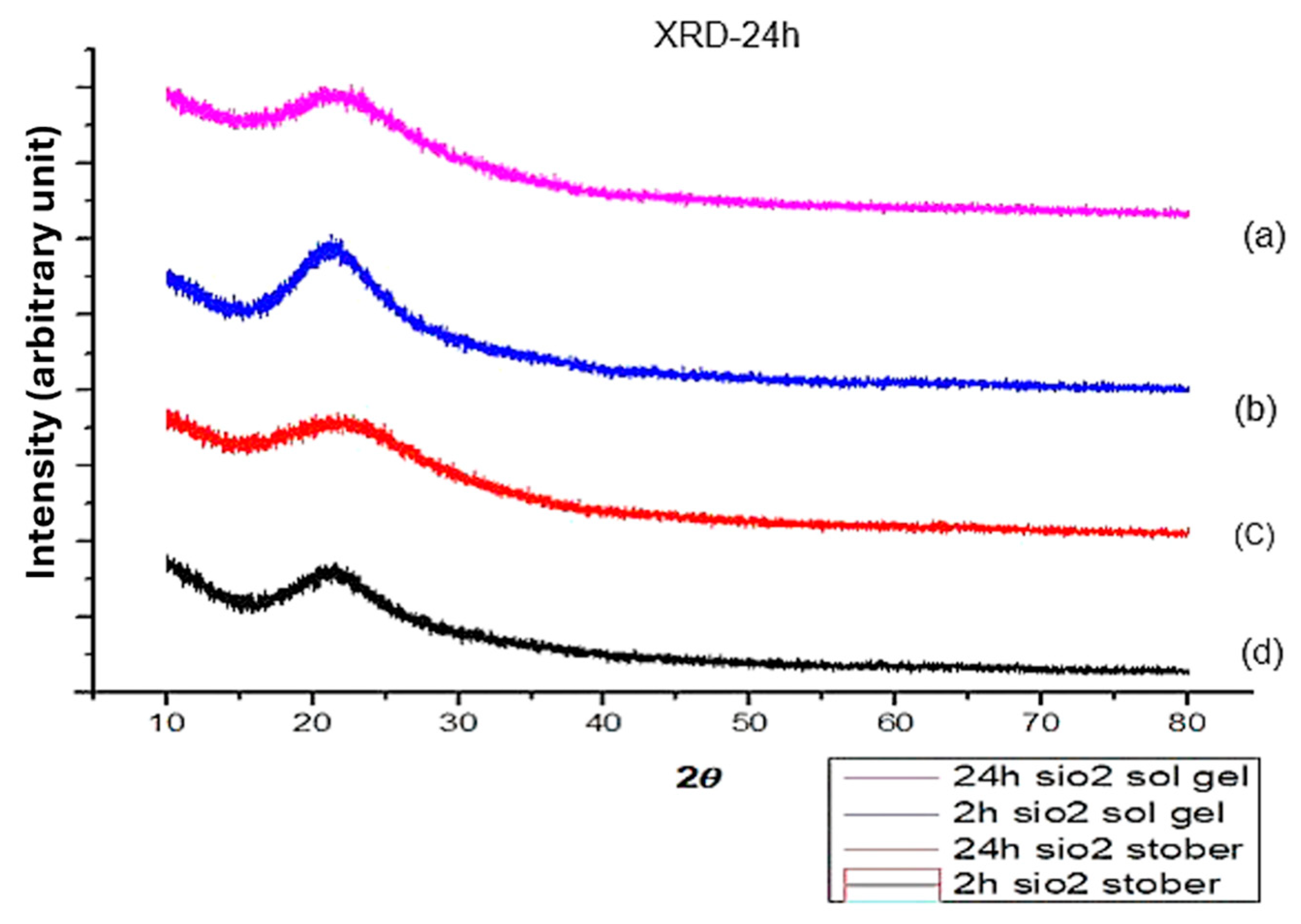

3.2. XRD for Pure and Sulfonated Silica

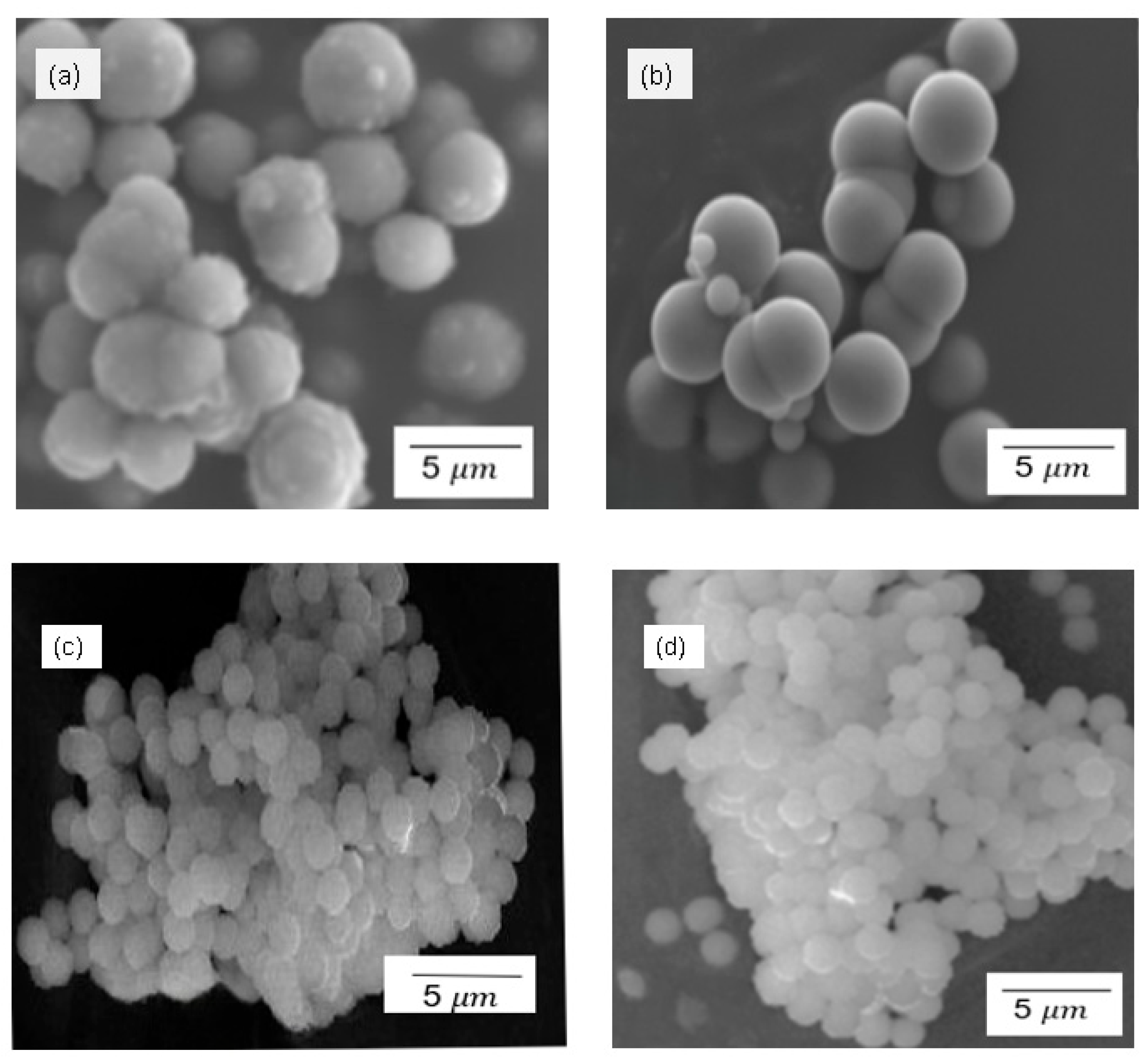

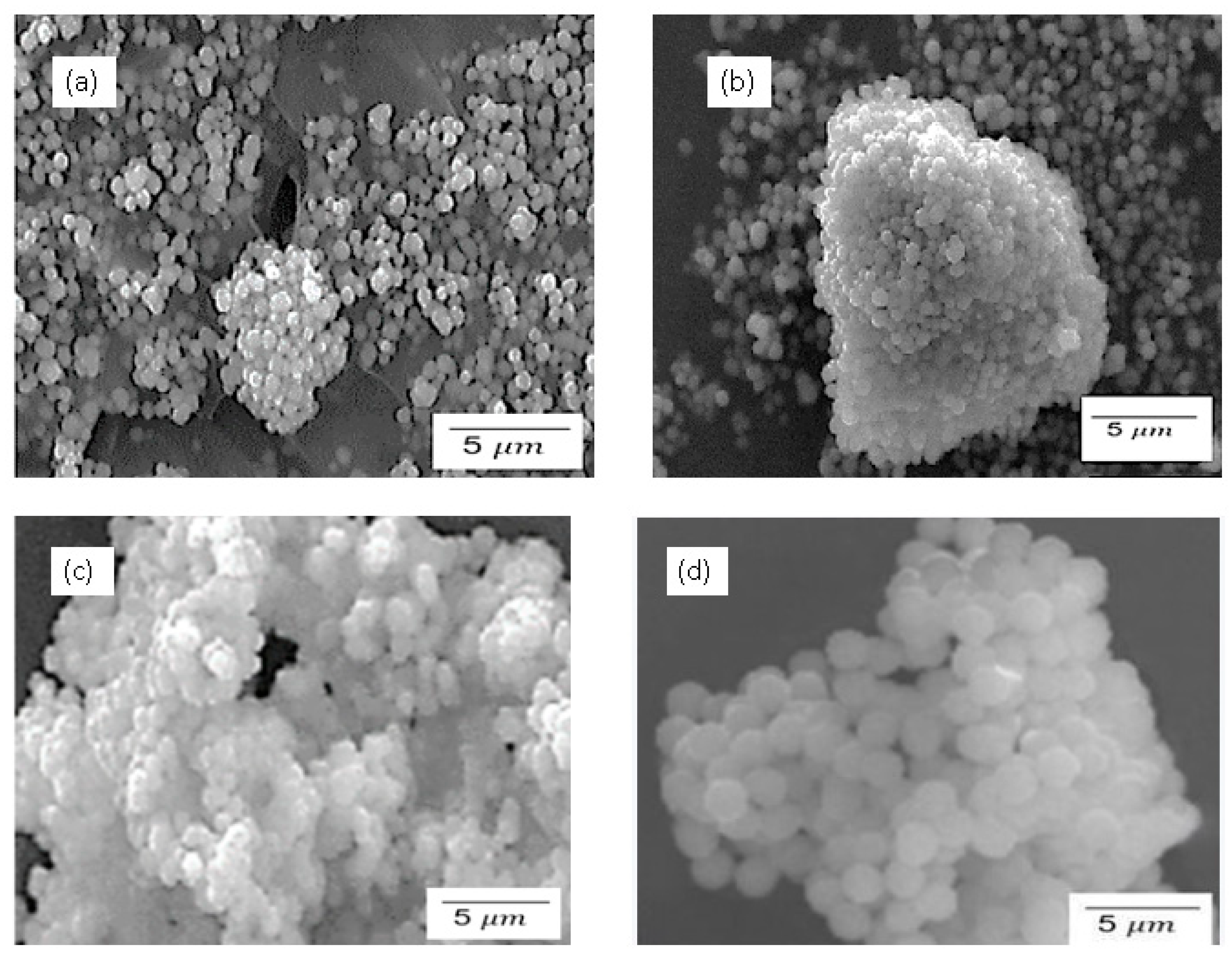

3.3. SEM Results for Pure and Sulfonated Silica

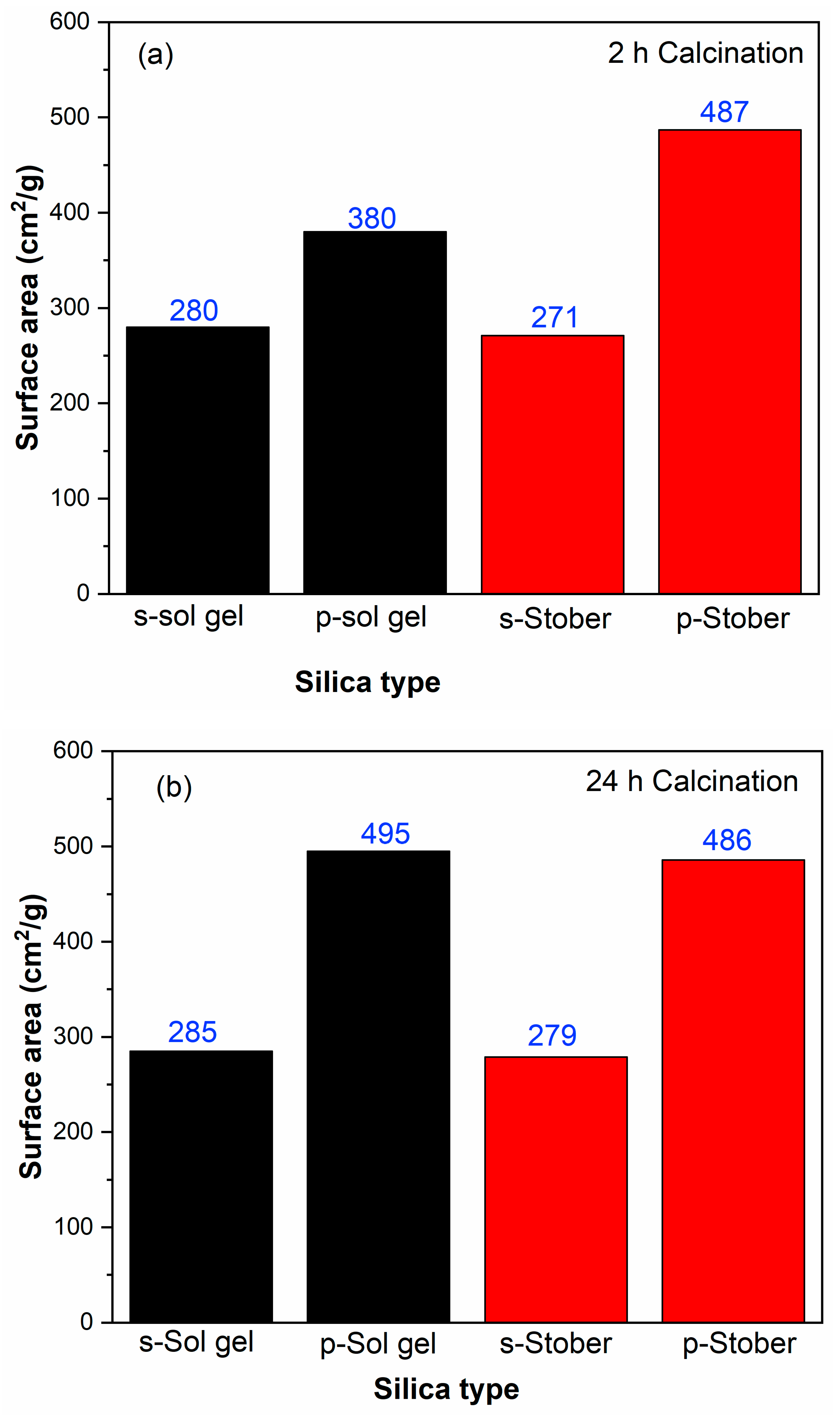

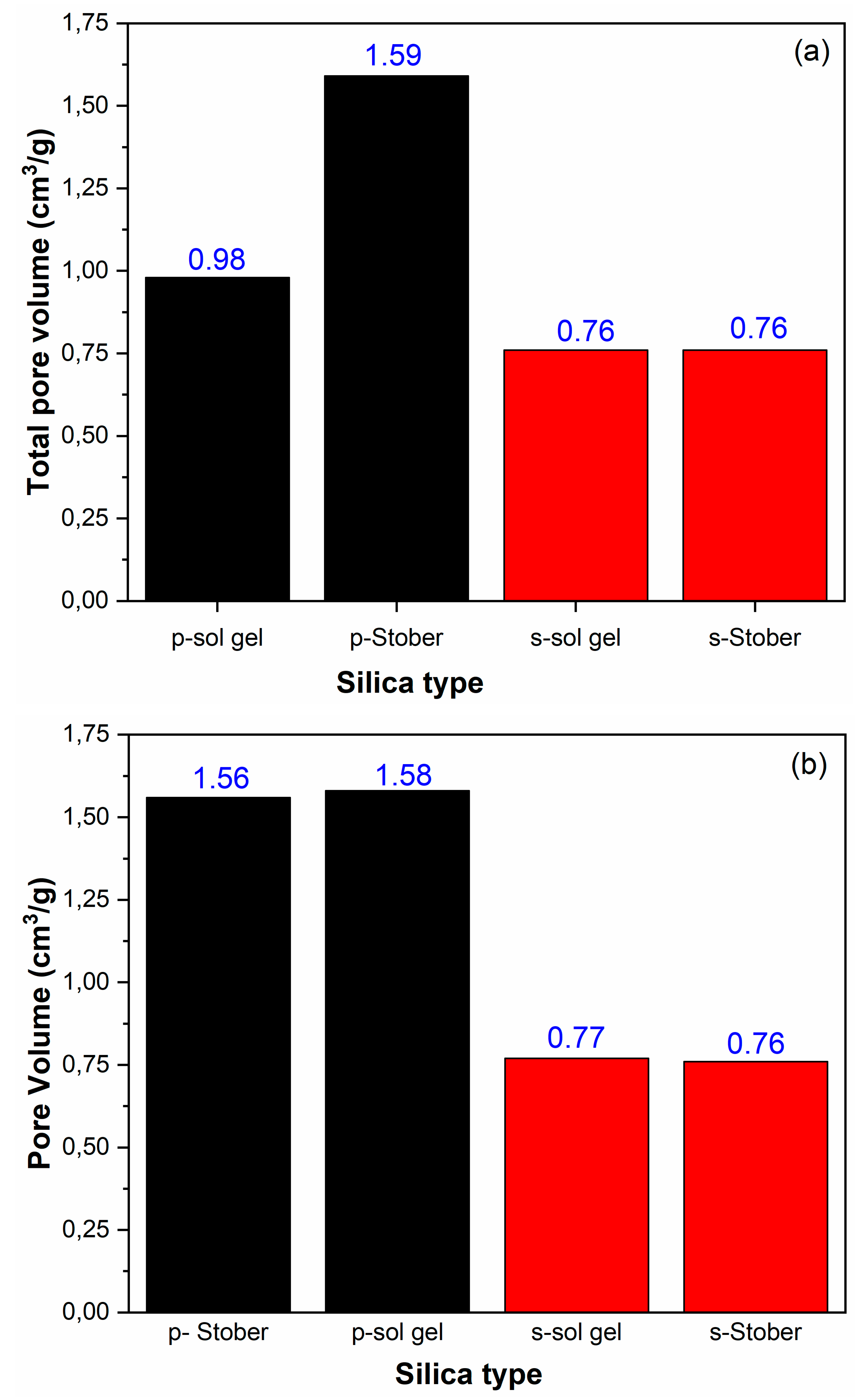

3.4. BET Results for the Pristine and Sulfonated Silica Calcinated for 2 h

- Results for silica calcinated for 24 h

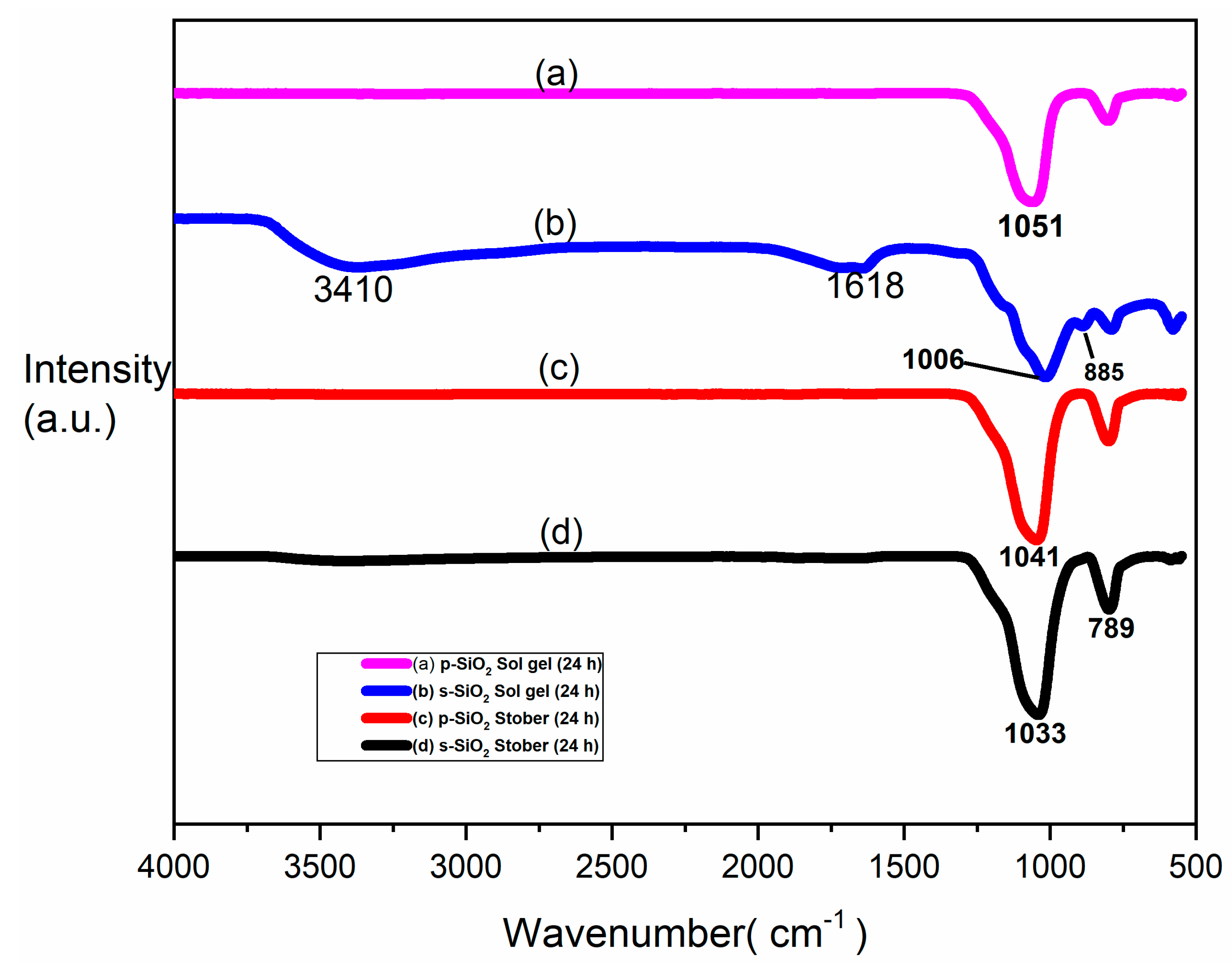

3.5. FTIR for Pure and Sulfonated Silica

3.6. XRD for Pure and Sulfonated Silica Calcinated at 24 h

3.7. SEM for Pure and Sulfonated Silica Calcinated at 24 h

3.8. BET Results for Pristine and Sulfonated Silica Calcinated at 24 h

3.9. Calcination Time Effects

3.10. Effects of Sulfonation on the Silica Nanoparticles

3.11. Total Pore Volumes

3.12. Stober Versus Sol Gel Synthesis Methods

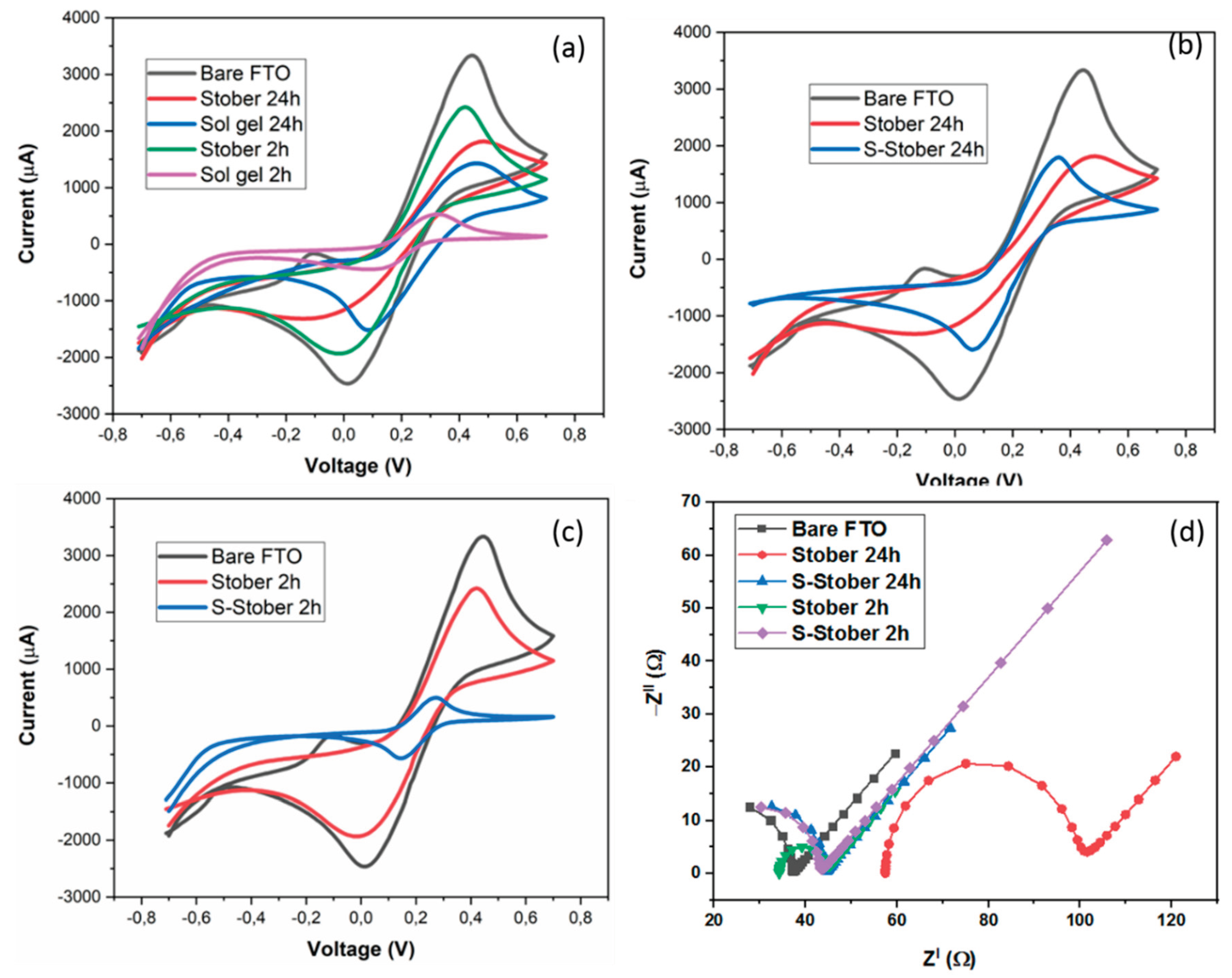

3.13. Electrochemical Characterisation

4. Conclusions

References

- Ellerbrock, R.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing Amorphous Silica, Short-Range-Ordered Silicates and Silicic Acid Species by FTIR. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, Z.; Ni, S.; Ren, B.; Hu, J. Origin, Formation, and Transformation of Different Forms of Silica in Xuanwei Formation Coal, China, and Its’ Emerging Environmental Problem. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2023, 30, 120735–120748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zargar, S. M.; Mahajan, R.; Bhat, J. A.; Nazir, M.; Deshmukh, R. Role of Silicon in Plant Stress Tolerance: Opportunities to Achieve a Sustainable Cropping System. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Y. P.; Kamarudin, S. K.; Masdar, M. S. Silica-Related Membranes in Fuel Cell Applications: An Overview. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 16068–16084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y. P.; Kamarudin, S. K.; Masdar, M. S. Silica-Related Membranes in Fuel Cell Applications: An Overview. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. Elsevier Ltd August 16, 2018, pp 16068–16084. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, G.; Luo, X.; Xiong, J.; Liu, Z.; Cai, W. Effect of Nano-Size of Functionalized Silica on Overall Performance of Swelling-Filling Modified Nafion Membrane for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Application. Appl Energy 2018, 213, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, E.; Siniwi, W. T.; Mahatmanti, F. W.; Jumaeri, J.; Atmaja, L.; Widiastuti, N. Modification of Chitosan Membranes with Nanosilica Particles as Polymer Electrolyte Membranes. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics Inc., 2016; Vol. 1725. [CrossRef]

- Budnyak, T. M.; Vlasova, N. N.; Golovkova, L. P.; Markitan, O.; Baryshnikov, G.; Ågren, H.; Slabon, A. Nucleotide Interaction with a Chitosan Layer on a Silica Surface: Establishing the Mechanism at the Molecular Level. Langmuir 2021, 37, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modau, L.; Sigwadi, R.; Mokrani, T.; Nemavhola, F. Chitosan Membranes for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Applications. Membranes (Basel) 2023, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio, M.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Nosach, L. V.; Voronin, E. F. Chitosan–Silica Composites for Adsorption Application in the Treatment of Water and Wastewater from Anionic Dyes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. dos S. da; Santos, J. H. Z. dos. Silica Particle Size and Polydispersity Control from Fundamental Practical Aspects of the Stöber Method. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2024, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R. S.; Raimundo, I. M.; Pimentel, M. F. Revising the Synthesis of Stöber Silica Nanoparticles: A Multivariate Assessment Study on the Effects of Reaction Parameters on the Particle Size. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2019, 577, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M. C. Sol-Gel Silica Nanoparticles in Medicine: A Natural Choice. Design, Synthesis and Products. Molecules 2018, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St, E.; Nanoparticles, S.; Mechanism, G.; Nanostructures, S.; Imaging, M. Engineering Stöber Silica Nanoparticles : Insights into the Growth Mechanism and Development of Silica-Based Nanostructures for Multimodal Imaging Oscar Hernando Moriones Botero.

- Mujiyanti, D. R.; Surianthy, M. D.; Junaidi, A. B. The Initial Characterization of Nanosilica from Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) with the Addition Polivynil Alcohol by Fourier Transform Infra Red. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2018, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzmüller, L.; Nitschke, F.; Rudolph, B.; Berson, J.; Schimmel, T.; Kohl, T. Dissolution Control and Stability Improvement of Silica Nanoparticles in Aqueous Media. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammud, A. M.; Gupta, N. K. Nanostructured SiO2 Material: Synthesis Advances and Applications in Rubber Reinforcement. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 18524–18546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petreanu, I.; Niculescu, V. C.; Enache, S.; Iacob, C.; Teodorescu, M. Structural Characterization of Silica and Amino-Silica Nanoparticles by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Raman Spectroscopy. Anal Lett 2023, 56, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, P.; Gayathri, R.; Pugalenthi, M. R.; Cao, G.; Liu, C.; Prabhu, M. R. Nanosulfonated Silica Incorporated SPEEK/SPVdF-HFP Polymer Blend Membrane for PEM Fuel Cell Application. Ionics (Kiel) 2020, 26, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvimary, J.; Sundararajan, M.; Prabhu, M. R. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Hybrid Polymer Electrolyte Membranes for Fuel Cell Application. Ionics (Kiel) 2018, 24, 3555–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangasamy, V. S.; Thayumanasundaram, S.; Seo, J. W.; Locquet, J. P. Vibrational Spectroscopic Study of Pure and Silica-Doped Sulfonated Poly(Ether Ether Ketone) Membranes. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2015, 138, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sompech, S.; Dasri, T.; Thaomola, S. Preparation and Characterization of Amorphous Silica and Calcium Oxide from Agricultural Wastes. 2016.

- Trisunaryanti, W.; Larasati, S.; Triyono, T.; Santoso, N. R.; Paramesti, C. Selective Production of Green Hydrocarbons from the Hydrotreatment of Waste Coconut Oil over Ni- And NiMo-Supported on Amine-Functionalized Mesoporous Silica. Bulletin of Chemical Reaction Engineering & Catalysis 2020, 15, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Su, H.; Wang, S. The Combined Method to Synthesis Silica Nanoparticle by Stöber Process. J Solgel Sci Technol 2020, 96, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivolapov, P.; Myronyuk, O.; Baklan, D. Synthesis of Stober Silica Nanoparticles in Solvent Environments with Different Hansen Solubility Parameters. Inorg Chem Commun 2022, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivolapov, P.; Myronyuk, O.; Baklan, D. Synthesis of Stober Silica Nanoparticles in Solvent Environments with Different Hansen Solubility Parameters. Inorg Chem Commun 2022, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modena, M. M.; Rühle, B.; Burg, T. P.; Wuttke, S. Nanoparticle Characterization: What to Measure? Advanced Materials. Wiley-VCH Verlag 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, O.; Stoeger, T. Surface Area Is the Biologically Most Effective Dose Metric for Acute Nanoparticle Toxicity in the Lung. J Aerosol Sci 2016, 99, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolai, J.; Mandal, K.; Jana, N. R. Nanoparticle Size Effects in Biomedical Applications. ACS Applied Nano Materials. American Chemical Society July 23, 2021, pp 6471–6496. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, J. W.; Santos, J. L.; Williford, J. M.; Mao, H. Q. Control of Polymeric Nanoparticle Size to Improve Therapeutic Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2015, 219, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Qi, J.; Gogoi, R.; Wong, J.; Mitragotri, S. Role of Nanoparticle Size, Shape and Surface Chemistry in Oral Drug Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 238, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javdani, H.; Khosravi, R.; Etemad, L.; Moshiri, M.; Zarban, A.; Hanafi-bojd, M. Y. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials Tannic Acid-Templated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as an Effective Treatment in Acute Ferrous Sulfate Poisoning. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2020, 307, 110486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Malik, M. M.; Purohit, R. Synthesis of High Surface Area Mesoporous Silica Materials Using Soft Templating Approach. Mater Today Proc 2018, 5, 4128–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thahir, R.; Wahab, A. W.; Nafie, N. La; Raya, I. Synthesis of High Surface Area Mesoporous Silica SBA-15 by Adjusting Hydrothermal Treatment Time and the Amount of Polyvinyl Alcohol. Open Chem 2019, 17, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S. zhong; Zeng, X.; Huang, L.; Wu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zou, J. The Formation Mechanisms of Porous Silicon Prepared from Dense Silicon Monoxide. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 7990–7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, F.; Castaldo, R.; Latronico, T.; Lasala, P.; Gentile, G.; Lavorgna, M.; Striccoli, M.; Agostiano, A.; Comparelli, R.; Depalo, N.; Curri, M. L.; Fanizza, E. High Surface Area Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with Tunable Size in the Sub-Micrometer Regime: Insights on the Size and Porosity Control Mechanisms. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Ding, L.; Wu, T.; Xu, G.; Yang, F.; Xiang, M. Effect of Surfactant on Morphology and Pore Size of Polysulfone Membrane. Journal of Polymer Research 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, S. K.; Park, J. O.; Choi, S. W.; Kim, K. H.; Ko, T.; Pak, C.; Lee, J. C. Highly Reinforced Pore-Filling Membranes Based on Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone)s for High-Temperature/Low-Humidity Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. J Memb Sci 2017, 537, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L. The in Fl Uence of the Ammonia Concentration and the Water Content on the Water Sorption Behavior of Ambient Pressure Dried Silica Xerogels. J Solgel Sci Technol 2020, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon V, S.; Ribeiro, T.; Farinha, J. P. S.; Baleizão, C.; Ferreira, P. J. On the Structure of Amorphous Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles by Aberration-Corrected STEM. Small 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Subhani, T.; Husain, S. W. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica Nanoparticles from Clay. Journal of Asian Ceramic Societies 2016, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Subhani, T.; Wilayat Husain, S. Synthesis of Silica Nanoparticles from Sodium Silicate under Alkaline Conditions. J Solgel Sci Technol 2016, 77, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, H. K.; Taherizadeh, A.; Maleki, A. Atomistic-Level Study of the Mechanical Behavior of Amorphous and Crystalline Silica Nanoparticles. Ceram Int 2020, 46, 21647–21656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Subhani, T.; Husain, S. W. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica Nanoparticles from Clay Synthesis and Characterization of Silica Nanoparticles from Clay. Integr Med Res 2018, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. ting; Wu, Y. bo; Bi, Y. guang. Rapid Synthesis of SiO2 by Ultrasonic-Assisted Stober Method as Controlled and PH-Sensitive Drug Delivery. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Su, H.; Wang, S. The Combined Method to Synthesis Silica Nanoparticle by Stöber Process. J Solgel Sci Technol 2020, 96, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R. S.; Raimundo, I. M.; Pimentel, M. F. Revising the Synthesis of Stöber Silica Nanoparticles: A Multivariate Assessment Study on the Effects of Reaction Parameters on the Particle Size. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2019, 577, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagar, M. E.; Afifi, T. H. Catalytic Activity of Sulfated and Phosphated Catalysts towards the Synthesis of Substituted Coumarin. 2018, No. January. [CrossRef]

- Dhaneswara, D.; Fatriansyah, J. F.; Situmorang, F. W.; Haqoh, A. N. Synthesis of Amorphous Silica from Rice Husk Ash: Comparing HCl and CH3COOH Acidification Methods and Various Alkaline Concentrations. International Journal of Technology 2020, 11, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usgodaarachchi, L.; Thambiliyagodage, C.; Wijesekera, R.; Bakker, M. G. Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Derived from Rice Husk and Surface-Controlled Amine Functionalization for Efficient Adsorption of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2021, 4, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfawaz, A.; Alsalme, A.; Alkathiri, A.; Alswieleh, A. Surface Functionalization of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with Brønsted Acids as a Catalyst for Esterificatsion Reaction. J King Saud Univ Sci 2022, 34, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, L.; Hoa, M.; Chi, N. T.; Dang, L. Q.; Nguyen, M. T.; Le, T.; Tran, T. Synthesis of Amorphous Silica and Sulfonic Acid Functionalized Silica Used as Reinforced Phase for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane. [CrossRef]

| Bet surface area (m2/g) | Total pore volume (cm3/g) | Average pore diameter (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| s-SiO2(sol gel) | 280 | 0.76 | 21.00 |

| SiO2 (sol gel) | 398 | 0.98 | 10.67 |

| s-SiO2 (Stober) | 271 | 0.76 | 20.89 |

| SiO2 (Stober) | 487 | 1.59 | 12.45 |

| Bet surface area (m2/g) | Total pore volume (cm3/g) | Average pore diameter (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| s-SiO2(Sol gel) | 285 | 0.77 | 21.02 |

| SiO2(Sol gel) | 495 | 1.58 | 12.10 |

| s-SiO2 (Stober) | 279 | 0.76 | 21.52 |

| SiO2 (Stober) | 486 | 1.56 | 12.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).