Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of ZrO2 Nanoparticles

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy

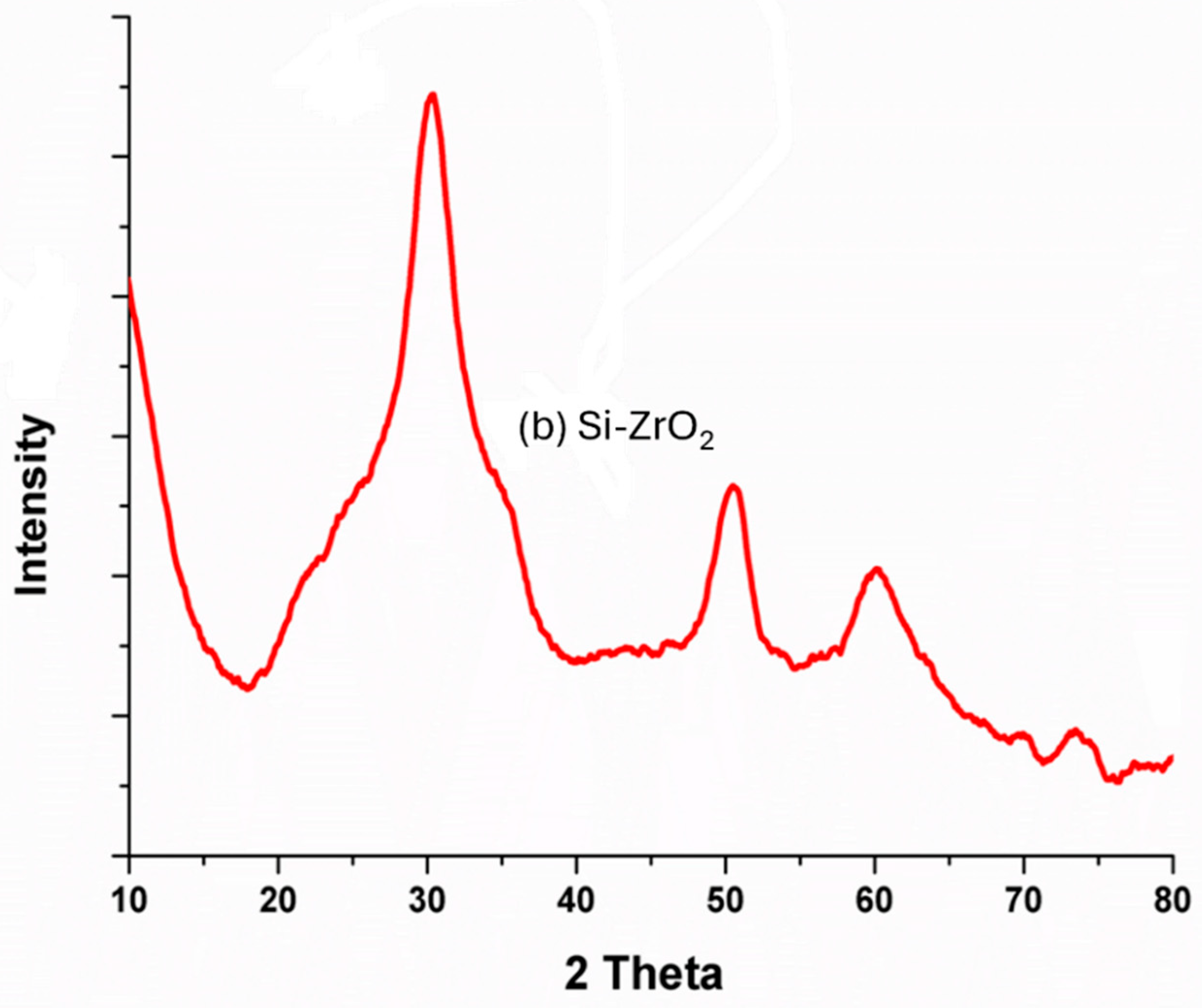

3.2. Structural Analysis

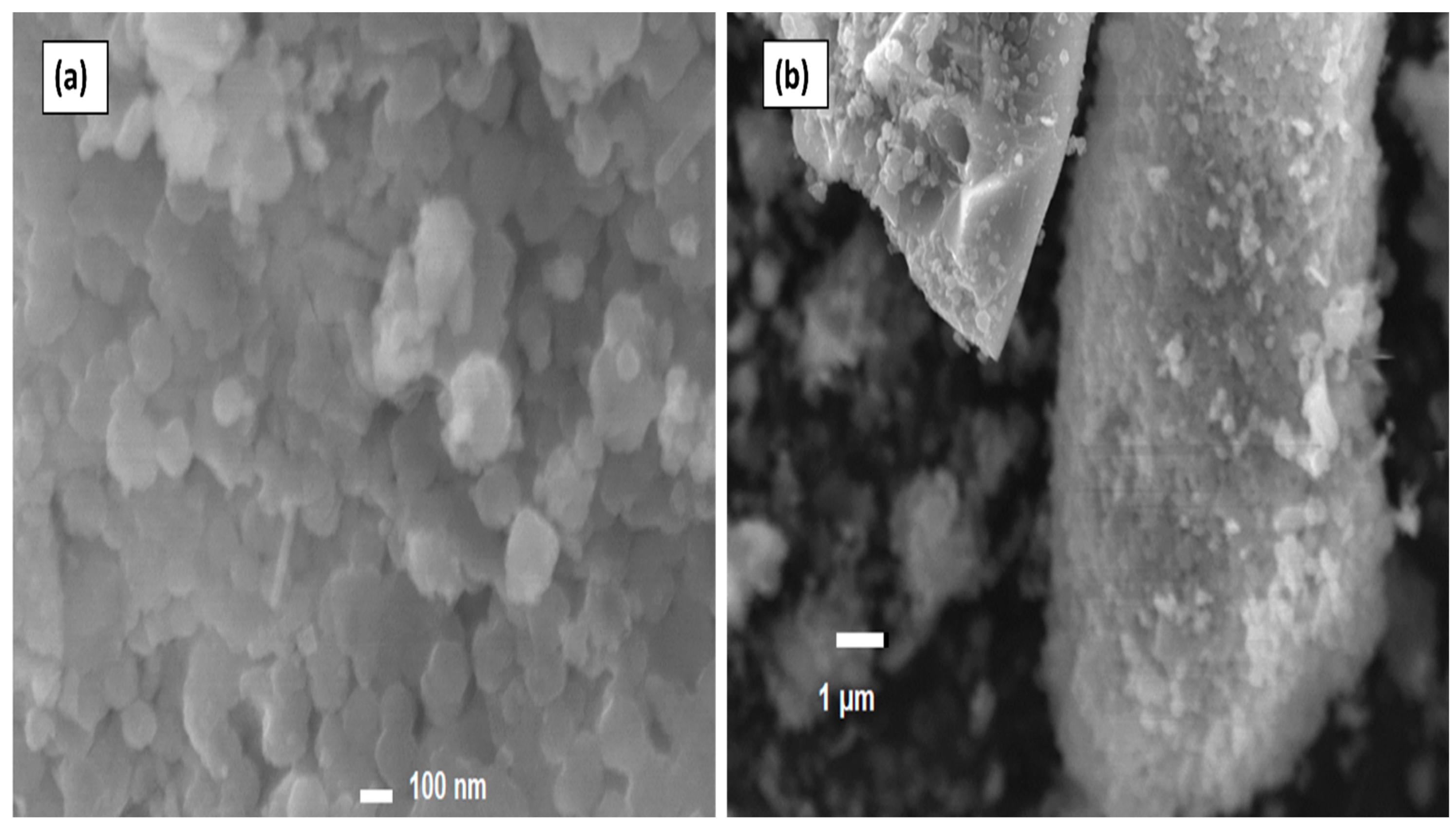

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

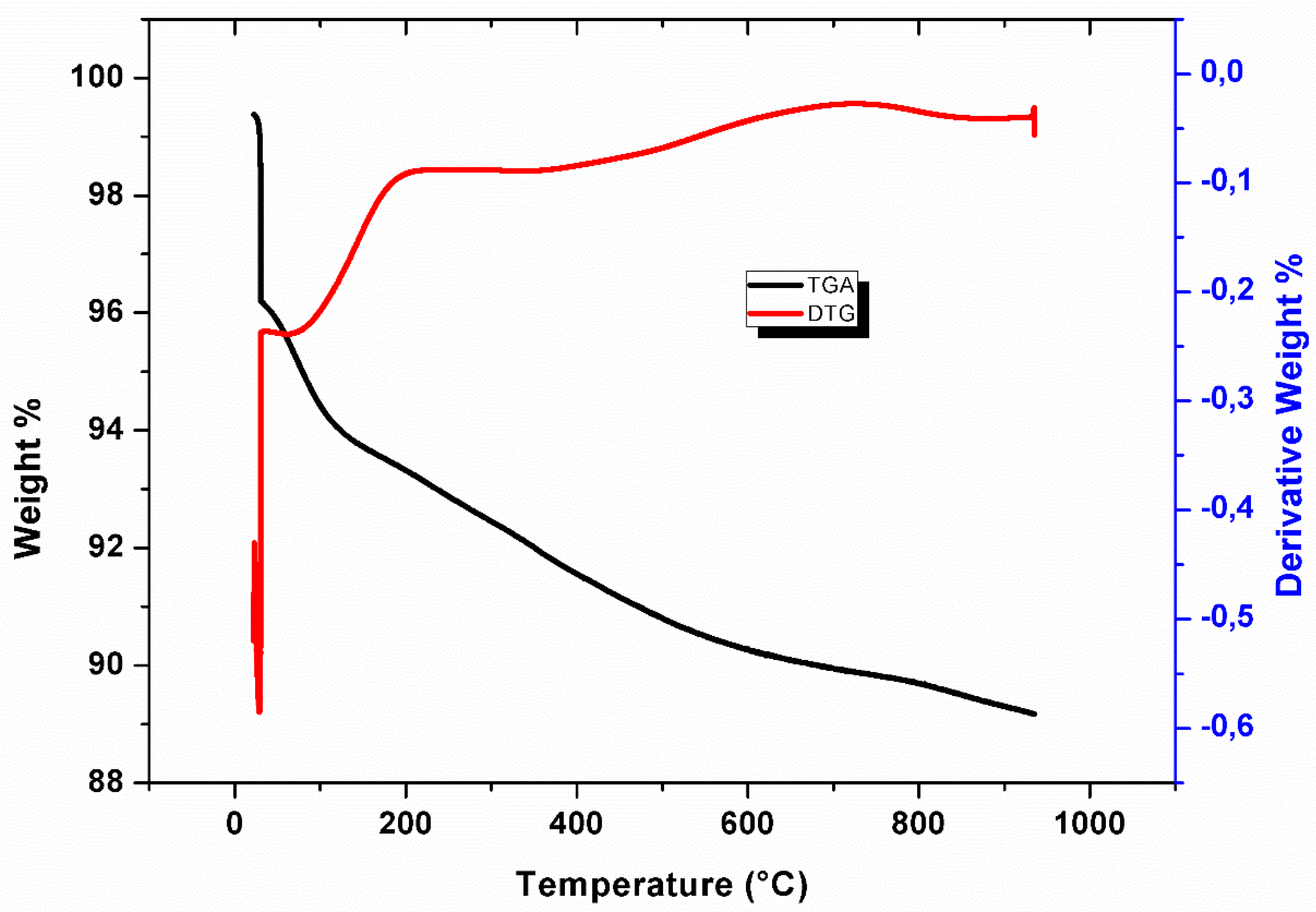

3.4. TGA and Derivative Thermo-Gravimetric (DTG)

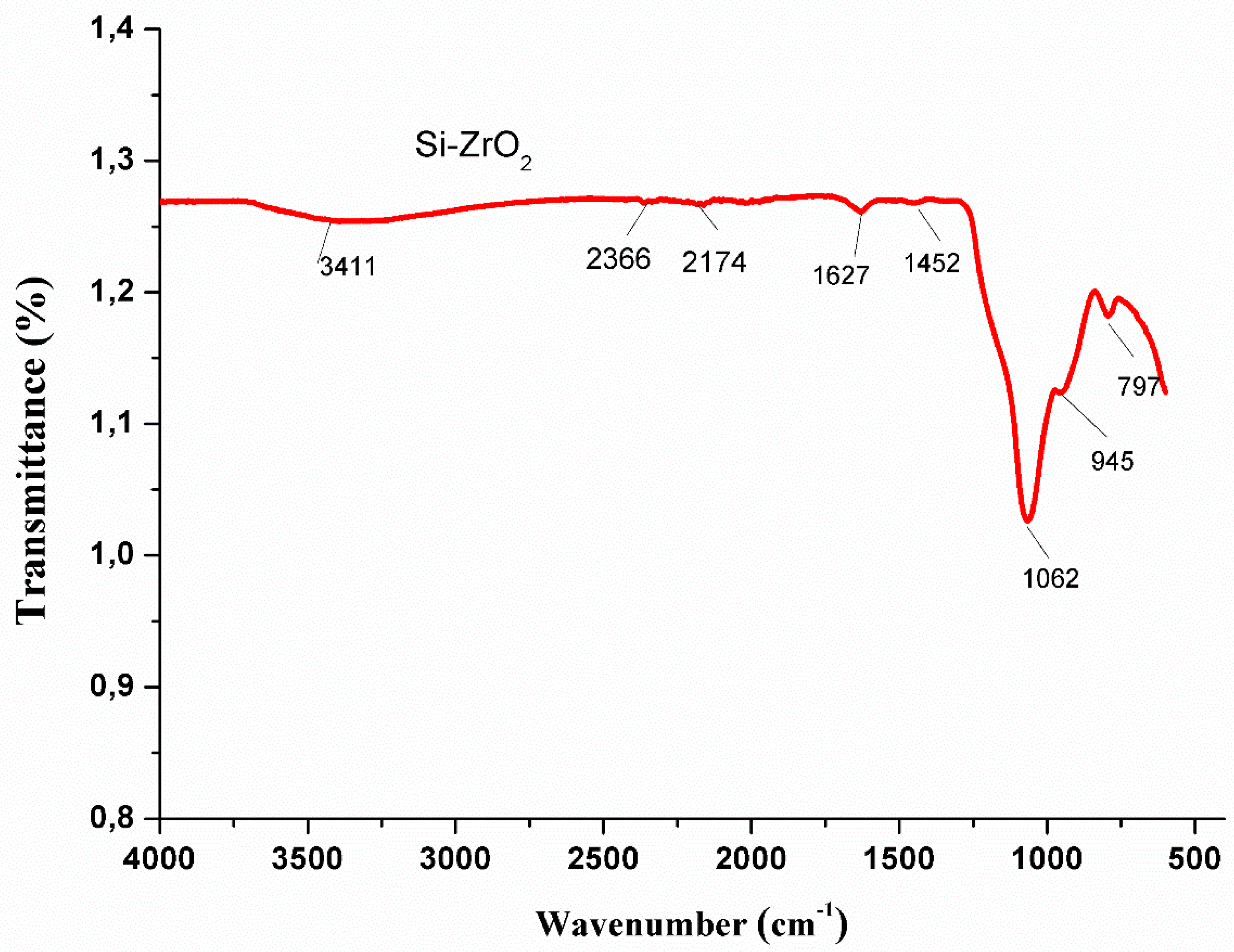

3.5. FTIR Spectrum of ZrO2 Nanoparticles

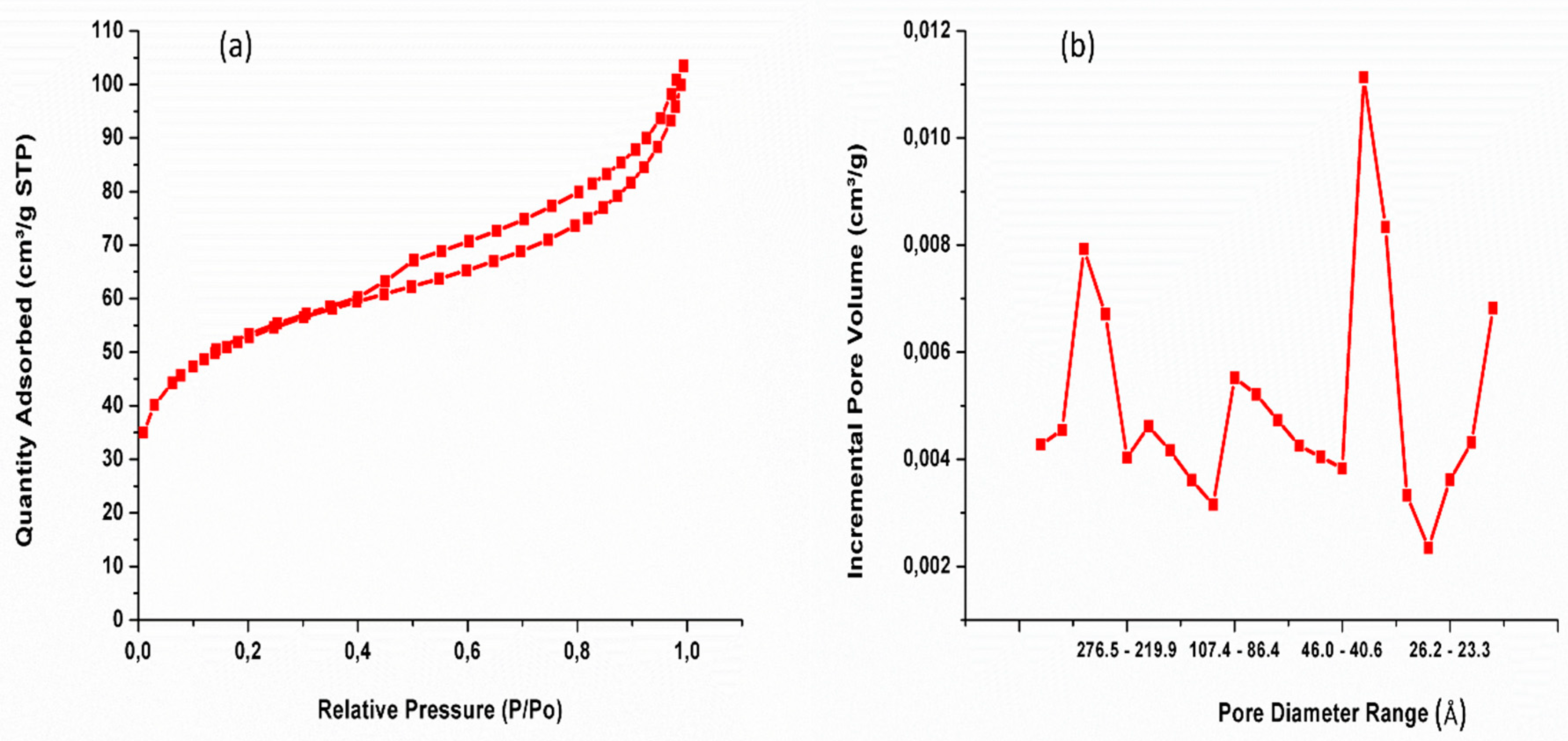

3.6. Nitrogen Adsorption-Desorption

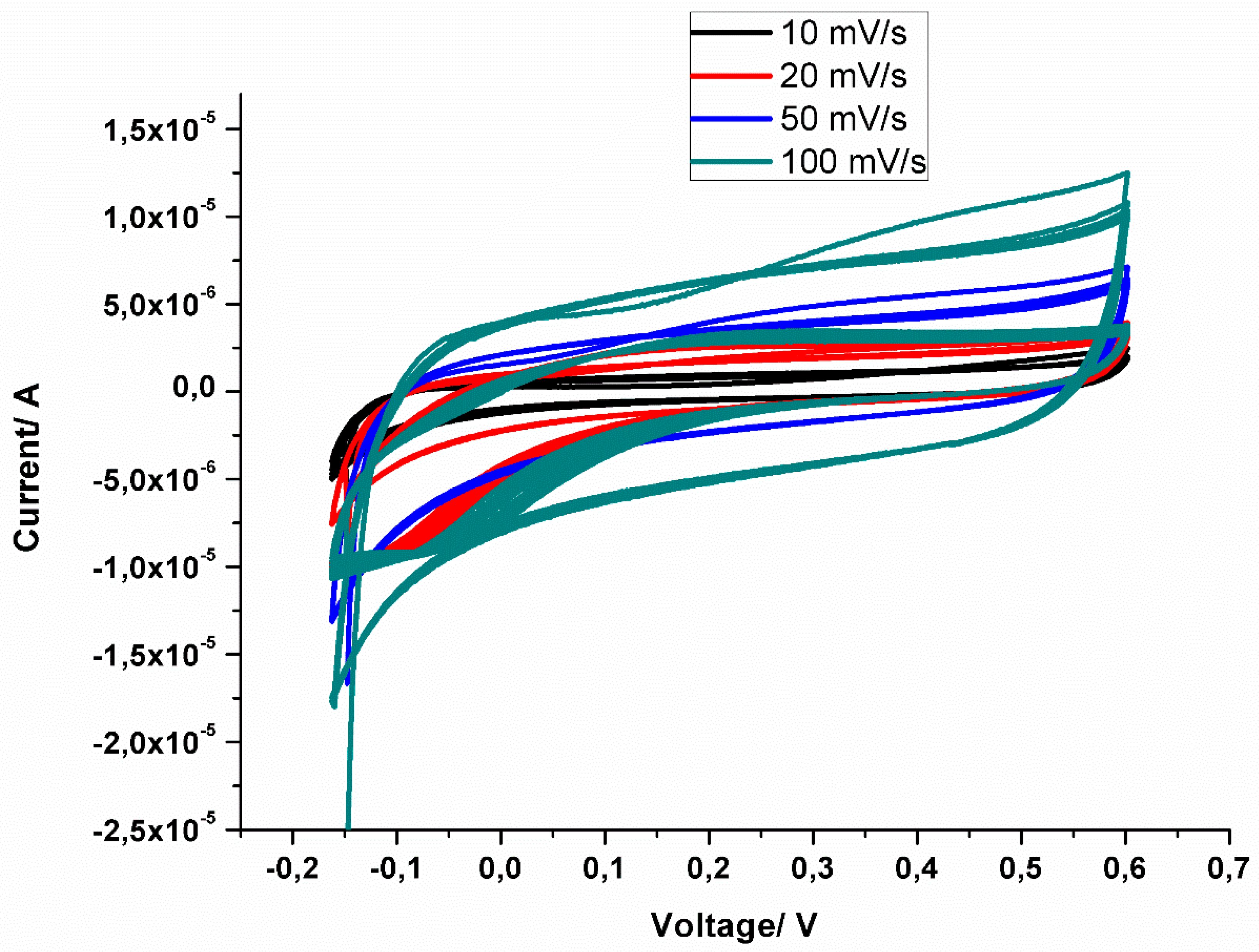

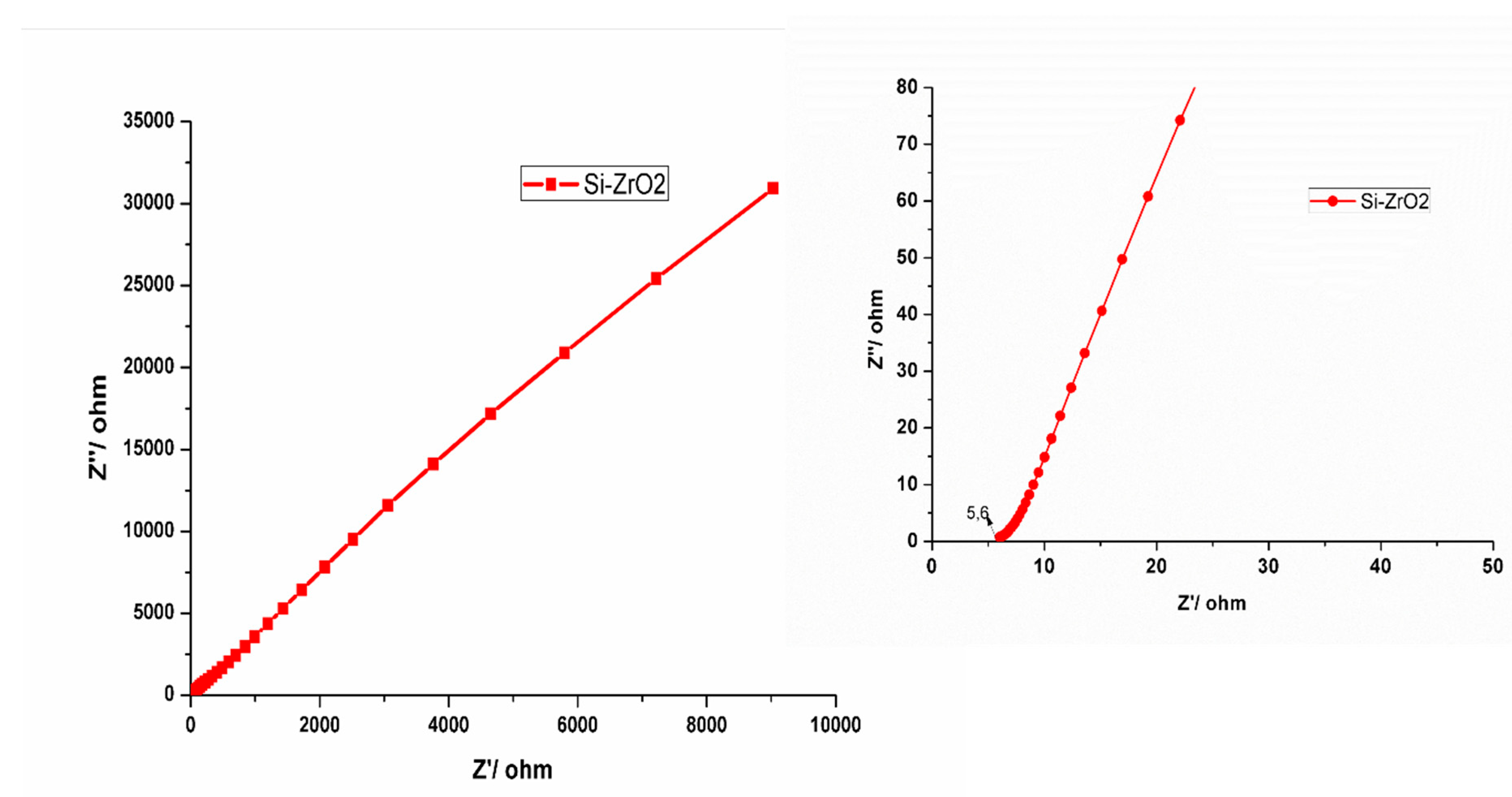

3.7. Electrochemical Results

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- S. Anjum, S. Ishaque, H. Fatima, W. Farooq, C. Hano, B.H. Abbasi, I. Anjum, Emerging Applications of Nanotechnology in Healthcare Systems: Grand Challenges and Perspectives, Pharmaceuticals, 14 (2021) 707. [CrossRef]

- L. Fu, B. Wang, S.K.M. Sathyanath, J. Chang, J. Yu, K. Leifer, H. Engqvist, Q. Li, W. Xia, Microstructure of rapidly-quenched ZrO2-SiO2 glass-ceramics fabricated by container-less aerodynamic levitation technology. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 106 (2023) 2635-2651. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, S. Mansoor, Z. Rafi, B. Kumari, A. Shoaib, M. Saeed, S. Alshehri, M.M. Ghoneim, M. Rahamathulla, U. Hani, A review on nanotechnology: Properties, applications, and mechanistic insights of cellular uptake mechanisms. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 348 (2022) 118008. [CrossRef]

- S. Hassanzadeh-Tabrizi, Precise calculation of crystallite size of nanomaterials: A review. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, (2023) 171914. [CrossRef]

- H. Lin, C. Yin, A. Mo, Zirconia Based Dental Biomaterials: Structure, Mechanical Properties, Biocompatibility, Surface Modification, and Applications as Implant. Frontiers in Dental Medicine, 2 (2021) 689198. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, M. Javaid, R.P. Singh, S. Rab, R. Suman, Applications of nanotechnology in medical field: a brief review. Global Health Journal, 7 (2023) 70-77. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Ballem, J.M. Córdoba, M. Odén, Mesoporous silica templated zirconia nanoparticles. Journal of nanoparticle research, 13 (2011) 2743-2748. [CrossRef]

- S. Raj, M. Hattori, M. Ozawa, Ag-doped ZrO2 nanoparticles prepared by hydrothermal method for efficient diesel soot oxidation. Materials Letters, 234 (2019) 205-207. [CrossRef]

- D. Hidayat, A. Syoufian, M. Utami, K. Wijaya, Synthesis and Application of Na2O/ZrO2 Nanocomposite for Microwave-assisted Transesterification of Castor Oil. ICS Physical Chemistry, 1 (2021) 26-26. [CrossRef]

- P. Bansal, N. Kaur, C. Prakash, G.R. Chaudhary, ZrO2 nanoparticles: An industrially viable, efficient and recyclable catalyst for synthesis of pharmaceutically significant xanthene derivatives. Vacuum, 157 (2018) 9-16. [CrossRef]

- P. Sengupta, A. Bhattacharjee, H.S. Maiti, Zirconia: A Unique Multifunctional Ceramic Material. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals, 72 (2019) 1981-1998. [CrossRef]

- C. Verdi, F. Karsai, P. Liu, R. Jinnouchi, G. Kresse, Thermal transport and phase transitions of zirconia by on-the-fly machine-learned interatomic potentials. npj Computational Materials, 7 (2021) 156. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Chitoria, A. Mir, M. Shah, A review of ZrO2 nanoparticles applications and recent advancements. Ceramics International, 49 (2023) 32343-32358. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Matt, S. Raghavendra, M. Shivanna, M. Sidlinganahalli, D.M. Siddalingappa, Electrochemical Detection of Paracetamol by Voltammetry Techniques Using Pure Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticle Based Modified Carbon Paste Electrode. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials, 31 (2021) 511-519. [CrossRef]

- S. Yilmaz, S. Cobaner, E. Yalaz, B. Amini Horri, Synthesis and Characterization of Gadolinium-Doped Zirconia as a Potential Electrolyte for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Energies, 15 (2022) 2826. [CrossRef]

- E. Gorbova, F. Tzorbatzoglou, C. Molochas, D. Chloros, A. Demin, P. Tsiakaras, Fundamentals and Principles of Solid-State Electrochemical Sensors for High Temperature Gas Detection. Catalysts, 12 (2021) 1. [CrossRef]

- F. Ahmadi, A. Sodagar-Taleghani, P. Ebrahimnejad, S.P.H. Moghaddam, F. Ebrahimnejad, K. Asare-Addo, A. Nokhodchi, A review on the latest developments of mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a promising platform for diagnosis and treatment of cancer. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 625 (2022) 122099. [CrossRef]

- R. Sigwadi, T. Mokrani, M. Dhlamini, The synthesis, characterization and electrochemical study of zirconia oxide nanoparticles for fuel cell application. Physica B: Condensed Matter, 581 (2020) 411842. [CrossRef]

- R. Sigwadi, M.S. Dhlamini, T. Mokrani, P. Nonjola, Effect of Synthesis Temperature on Particles Size and Morphology of Zirconium Oxide Nanoparticle. Journal of Nano Research, 50 (2017) 18-31. [CrossRef]

- W.-S. Dong, F.-Q. Lin, C.-L. Liu, M.-Y. Li, Synthesis of ZrO2 nanowires by ionic-liquid route. Journal of colloid and interface science, 333 (2009) 734-740. [CrossRef]

- Kocjan, M. Logar, Z. Shen, The agglomeration, coalescence and sliding of nanoparticles, leading to the rapid sintering of zirconia nanoceramics. Scientific reports, 7 (2017) 2541. [CrossRef]

- N.D. Lestari, R. Nurlaila, N.F. Muwwaqor, S. Pratapa, Synthesis of high-purity zircon, zirconia, and silica nanopowders from local zircon sand. Ceramics International, 45 (2019) 6639-6647. [CrossRef]

- N.Y. Mostafa, Z. Zaki, Q. Mohsen, S. Alotaibi, A. Abd El-moemen, M.A. Amin, Carboxylate-assisted synthesis of highly-defected monoclinic zirconia nanoparticles. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1214 (2020) 128232. [CrossRef]

- S. Soontaranon, W. Limphirat, S. Pratapa, XRD, WAXS, FTIR, and XANES studies of silica-zirconia systems. Ceramics International, 45 (2019) 15660-15670. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, H. Lei, Z. Ding, Y. Chen, R. Ding, T. Kim, Preparation of the rod-shaped SiO2@C abrasive and effects of its microstructure on the polishing of zirconia ceramics. Powder Technology, 395 (2022) 338-347. [CrossRef]

- H.-K. Min, Y.W. Kim, C. Kim, I.A. Ibrahim, J.W. Han, Y.-W. Suh, K.-D. Jung, M.B. Park, C.-H. Shin, Phase transformation of ZrO2 by Si incorporation and catalytic activity for isopropyl alcohol dehydration and dehydrogenation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 428 (2022) 131766. [CrossRef]

- S. Saravanan, R. Dubey, Synthesis of SiO2 nanoparticles by sol-gel method and their optical and structural properties. Romanian Journal of Information Science and Technology, 23 (2020) 105-112.

- X. Lv, L. Yuan, C. Rao, X. Wu, X. Qing, X. Weng, Structure and near-infrared spectral properties of mesoporous silica for hyperspectral camouflage materials. Infrared Physics & Technology, 129 (2023) 104558. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Y. Guo, Y. Zhu, D. An, W. Gao, Z. Wang, Y. Ma, Z. Wang, A sustainable route for the preparation of activated carbon and silica from rice husk ash. Journal of hazardous materials, 186 (2011) 1314-1319. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, Y. Xu, S. Li, L. Zhong, J. Wang, Y. Chen, High-surface-area mesoporous silica-yttria-zirconia ceramic materials prepared by coprecipitation method ― the role of silicon. Ceramics International, 48 (2022) 21951-21960. [CrossRef]

- Bumajdad, A.A. Nazeer, F. Al Sagheer, S. Nahar, M.I. Zaki, Controlled Synthesis of ZrO2 Nanoparticles with Tailored Size, Morphology and Crystal Phases via Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Films. Scientific reports, 8 (2018) 3695. [CrossRef]

- C.V. Reddy, B. Babu, I.N. Reddy, J. Shim, Synthesis and characterization of pure tetragonal ZrO2 nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Ceramics International, 44 (2018) 6940-6948. [CrossRef]

- S. Khalid, C. Cao, L. Wang, Y. Zhu, Microwave Assisted Synthesis of Porous NiCo2O4 Microspheres: Application as High Performance Asymmetric and Symmetric Supercapacitors with Large Areal Capacitance. Scientific reports, 6 (2016) 22699. [CrossRef]

- L.-P. Lv, Z.-S. Wu, L. Chen, H. Lu, Y.-R. Zheng, T. Weidner, X. Feng, K. Landfester, D. Crespy, Precursor-controlled and template-free synthesis of nitrogen-doped carbon nanoparticles for supercapacitors. RSC Advances, 5 (2015) 50063-50069. [CrossRef]

|

Sample ID |

Surface area (m2/g) |

Pore volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Si- ZrO2 | 185 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).