1. Introduction

Within the field of organic-inorganic hybrid compounds, thermal stability defines the resistance of a material to elevated temperatures without undergoing degradation of its organic fractions and is a critical factor in maintaining both its structural integrity and functional performance in advanced applications [1,2]. Thermal decomposition can also involve the cleavage of inorganic bonds, which can compromise the overall structure and limit the technological applicability. In this context, hybrid xerogels have emerged as versatile materials, combining the chemical tunability of organic moieties with the robustness of an inorganic silica matrix. Their multifunctional nature enables a wide range of applications, including optical coatings [3,4], membranes [5,6], films [5,6], catalysts [9,10], as well as applications for biomedicine [11,12] and photonics [13–15]. Among these, hybrid xerogels functionalised with organochlorinated groups, the focus of this study, stand out due to their controlled microporosity and enhanced structural order [16–18], properties that could significantly expand their potential for novel technological applications.

These materials are synthesised through the sol–gel method, which introduces organic moieties either via silane coupling agents or through co-condensation reactions between functionalised silanes and tetraalkoxysilanes. This approach allows the incorporation of organic groups into the silica matrix in a single step, tailoring both the chemical and textural properties [19]. The presence of organic substituents also promotes the formation of locally ordered domains, mediated by weak interactions such as hydrogen bonding, dispersion forces, or π–π stacking [20].

Previous studies in our group [16–18] analysed the morphology, structure, and porous texture of four series of hybrid xerogels synthesised at pH 4.5 from ClRTEOS:TEOS blends with different molar percentages of organochlorinated ClRTEOS triethoxysilanes (ClR substituent = ClM, chloromethyl; ClE, 2-chloroethyl; ClP, 3-chloropropyl; ClPh, 4-chlorophenyl). Solid-state ²⁹Si NMR spectroscopy confirmed the incorporation of organochlorinated substituents and the preservation of Si–C bonds. In the ClMTEOS and ClETEOS series, a high fraction of condensed T³ species was detected, together with increasing proportions of Q³ and Q⁴ species as the ClRTEOS content rose. These findings indicate the formation of ordered structures, which is supported by the observation of low-angle X-ray diffraction signals indicating the contraction of Si–O–Si bonds relative to the non-chlorinated analogues. These organochlorinated series also displayed higher skeletal densities, attributable to steric and electronic effects of the functional groups. Field Emission SEM analyses revealed that increasing the ClRTEOS precursor concentration modified the material morphology from granular to smoother and more compact textures, accompanied by decreasing N₂ and CO₂ adsorption capacities, evidencing the tunability of the porous texture. Remarkably, cage-like T₈ periodic structures were detected even at low ClRTEOS precursor content (as in the material obtained from TEOS:ClETEOS blend with 99:1 molar ratio), reflecting profound structural and textural changes compared with reference non-chlorinated materials. Overall, chlorine substitution was shown to promote local structural order more effectively than using non-chlorinated analogous groups, expanding the prospects of the resulting materials for their use in membranes, catalysts, optical sensors, and optoelectronic devices.

A notable property of silica-based materials is their thermal stability, which determines the maximum temperature they can endure without decomposition. In a previous work [21], we analysed the vapours released during the thermal decomposition of hybrid xerogels with a 10% molar content of the ClRTEOS precursors listed above and detected several compounds posing environmental and health risks. Therefore, it is essential to characterise the thermal degradation kinetics to ensure both the material stability and environmental safety. Through TGA analysis, three mass loss stages were identified for these compounds: the first, common to all samples, corresponds to desolvation; the second, associated with the decomposition of the organochlorinated groups, varies depending on the precursor; and the third, also common to all samples, most likely involves the transformation of the hybrid xerogels into silicon oxycarbide ceramics [22]. In the second stage, simple decomposition mechanisms were identified for ClETEOS, whereas multiple mechanistic pathways were proposed for ClMTEOS, ClPTEOS, and ClPhTEOS based on the large collection of decomposition products detected. The established order of thermal stability was ClPhTEOS > ClMTEOS > ClPTEOS > ClETEOS, indicating the maximum temperature limits for safe use. The analysis of the vapours generated during pyrolysis was carried out by coupled to FT–IR and GC–MS tecnhiques, which enabled the precise identification and quantification of volatile products, as well as the determination of the temperatures at which they reach their maximum concentration.

The objective of this study is to investigate the thermal decomposition kinetics of the four organochlorinated xerogels mentioned above and to correlate the results with the most abundant substances identified in the prior TGA/FT–IR/GC–MS analyses [21]. This approach will help define a safe operational window for new applications. Thermal degradation of hybrid materials involves complex reaction mechanisms that can be elucidated through well-known mathematical models. In this context, model-free methods such as the Flynn–Wall–Ozawa (FWO) approach are particularly useful, as they do not require prior assumptions about the reaction mechanism. These methods enable the evaluation of the apparent activation energy, Eα, which represents the energy barrier for characteristic stages of the global process. Additionally, the pre-exponential factor A, associated with the frequency of vibrations of the activated complex [23], can be deduced from Eα. Finally, the molar enthalpy change (ΔH) can also be deduced from Eα, providing insight into the endothermic nature of the thermal decomposition process in siliceous materials.

Multiple stages are typically involved in the thermal decomposition of hybrid organic-inorganic materials [22], primarily focusing on desolvation and decomposition of the organic fraction. To identify an appropriate reaction model, f(α), the International Confederation of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (ICTAC) recommends the ‘Z-master plot’ method proposed by Criado for solid-state reactions [24]. According to the literature, the thermal degradation kinetics in inorganic materials typically conform to nucleation and growth models (An) [25]. In contrast, pyrolysis of organic matrices is best described by diffusion models (Dn) [26]. Meanwhile, n-order models (Fn) and geometrical contraction models (Rn) are applicable to all material types [27,28].

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first comprehensive analysis in which both kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of the thermal decomposition of hybrid silica xerogels are determined using FWO analysis and the Criado master plot methodology. These parameters are essential for assessing the thermal stability of organochlorinated-containing materials, predicting their performance in novel applications (e.g., sensor technologies), and mitigating potential emissions of toxic compounds in occupational environments.

2. Results and Discussion

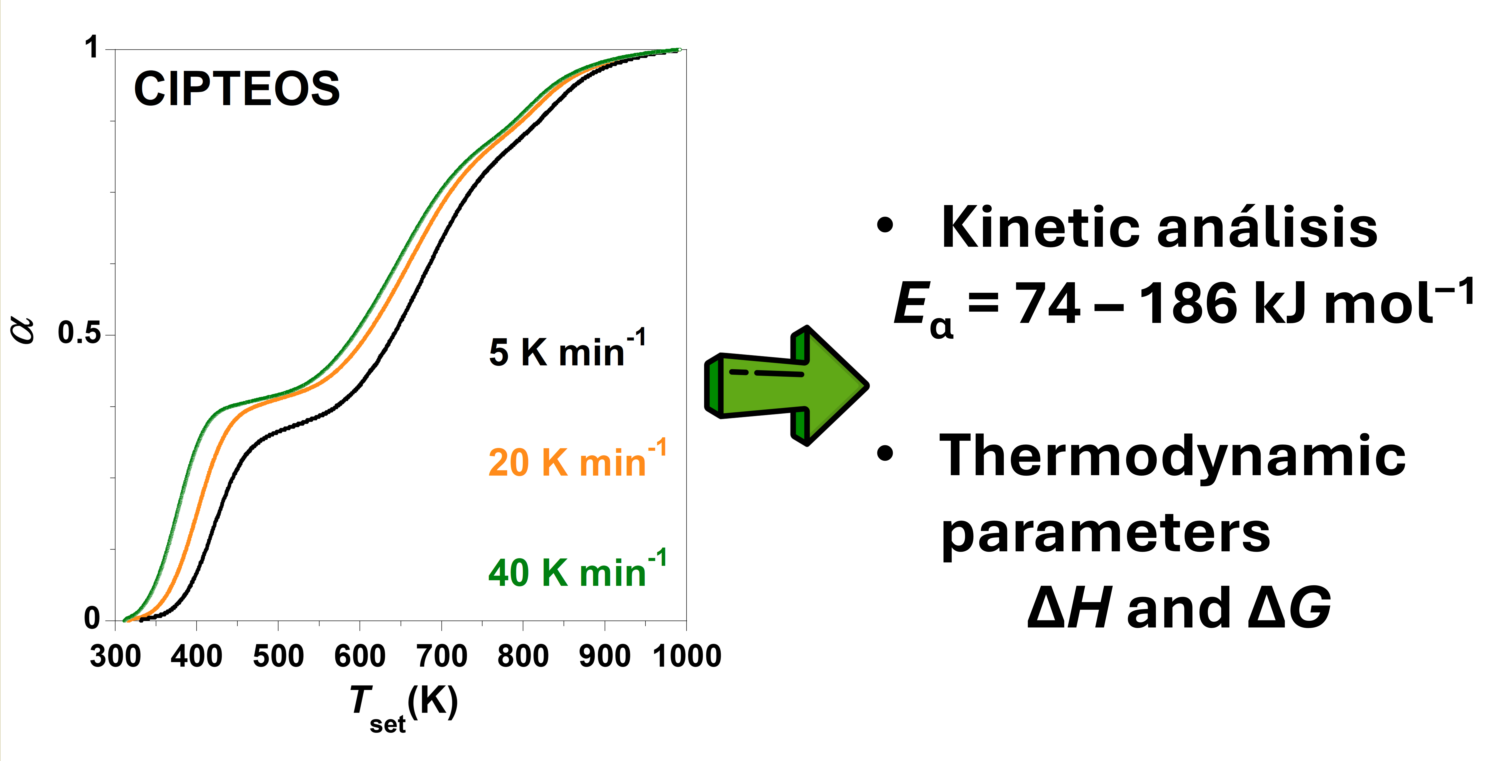

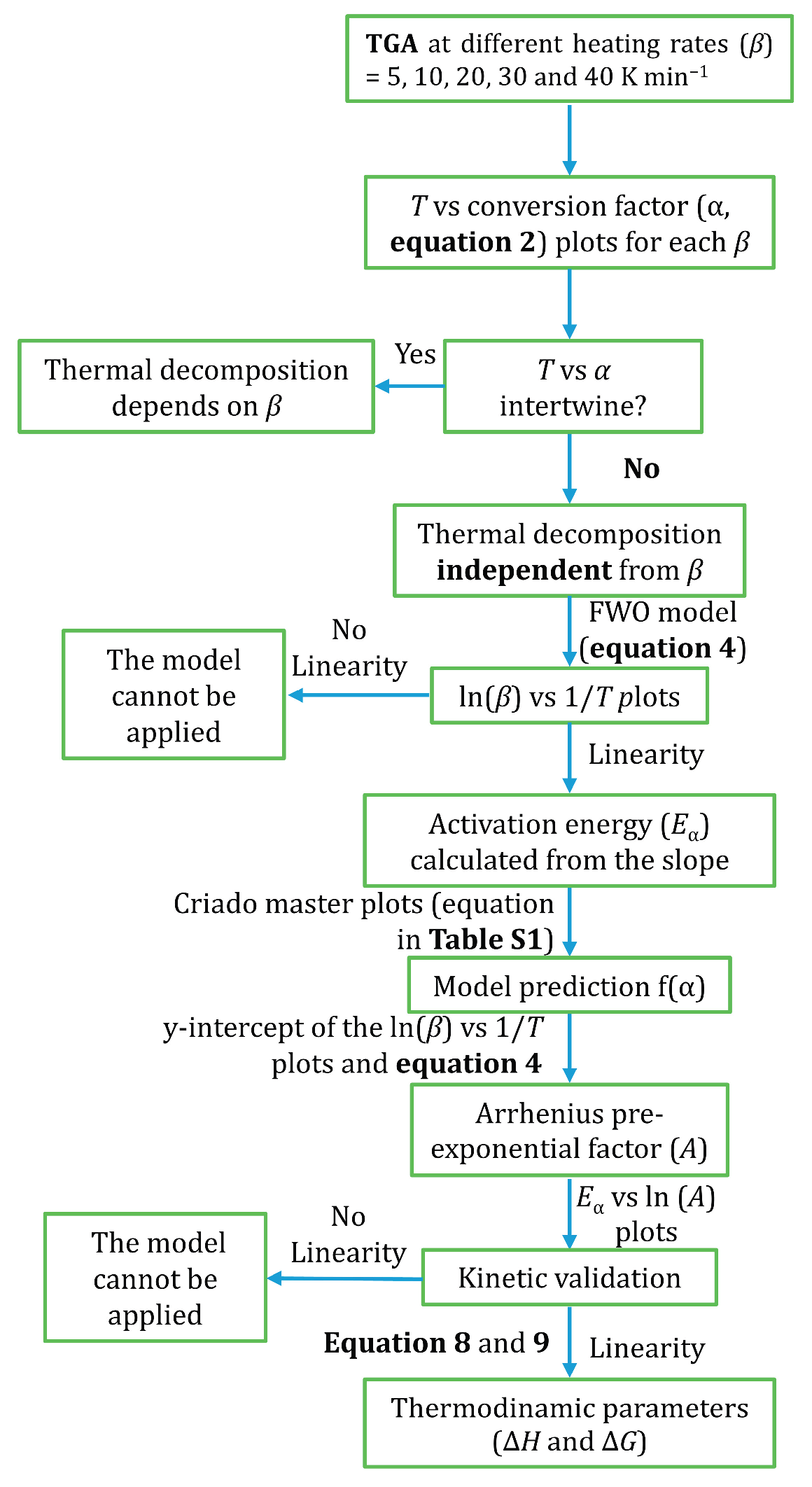

Figure 1 schematises the methodologic procedure followed for the kinetic analysis of the thermal decomposition of organochlorinated silica xerogels in this work. This methodology consists of: 1) verifying that the

T vs conversion degree (α) plots for different heating rates (

β) do not intertwine, 2) applying the FWO method, 3) calculating the

Eα, and 4) determining the thermodynamic parameters (Δ

H and Δ

G).

2.1. Thermal Analysis

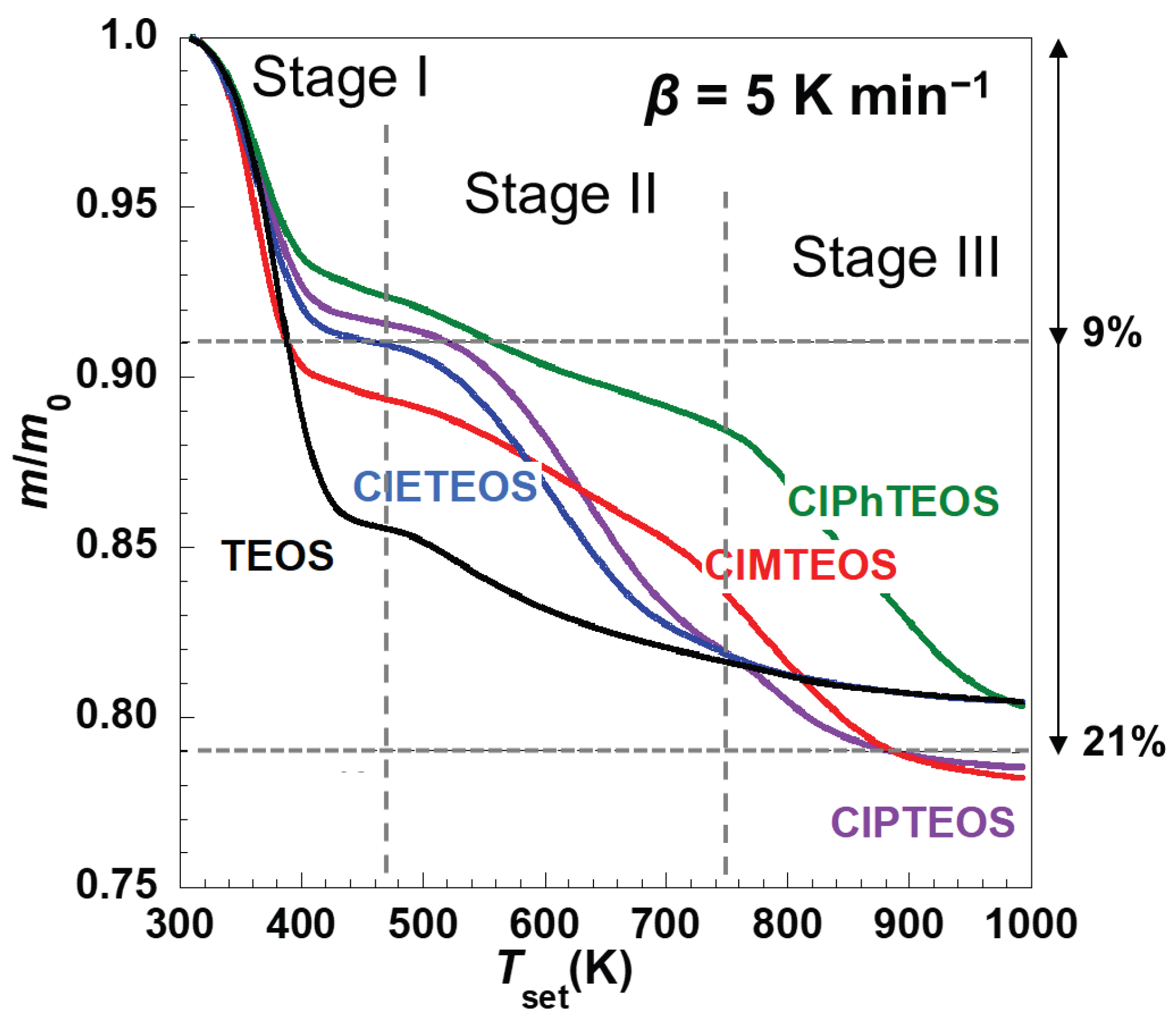

Figure 2 depicts the thermal evolution of the normalised mass loss (

mloss) of the reference xerogel (synthesised using only TEOS) and the four organochlorinated hybrid xerogels ClMTEOS, ClETEOS, ClPTEOS, and ClPhTEOS (with 10% molar content of the corresponding ClRTEOS precursor) for a heating rate (

β) of 5 K min

−1. The evolutions for the rest of heating rates applied in the TGA analyses (

β = 10, 20, 30 and 40 K min

−1) are gathered in

Figure S1. The different organic moieties of the ClRTEOS materials produced different behaviours during their decomposition at constant heating rates. Nevertheless, at least two distinct thermal decomposition stages are evident in all cases.

While the total mloss during the overall process was approximately 20–22% in all cases, the relative mass fractions of the individual decomposition stages differed significantly between TEOS and ClRTEOS. Notably, the overall stability of TEOS is enhanced by the incorporation of just 10% of organochlorinated precursor. This enhancement can be attributed to a modified porous texture in the resulting xerogels, whereby the inclusion of such precursors reduces both the pore size distribution and the specific surface area, cancelling the mesoporous domain present in TEOS and diminishing the pore volume [21].

For the reference material, the first stage (desolvation) constitutes the primary decomposition process, whereas the principal mloss for the ClRTEOS materials occurs at higher temperatures (from 450-500 K up to 900-1000 K) and associates with the decomposition of organic fractions. The decomposition profiles of the hybrid xerogels prepared using 3-chloropropyl and 2-chloroethyl-containing triethoxysilane precursors (ClPTEOS and ClETEOS, respectively) are similar and display a steep mloss extending up to ca. 750 K as the second stage. These profiles differ from those of the materials prepared with the chloromethyl and 4-chlorophenyl derivatives (ClMTEOS and ClPhTEOS, respectively), which are alike and exhibit a progressive, extensive mloss that reaches higher temperatures between ca. 750 and 800 K instead.

According to literature kinetic analyses on the thermal decomposition of a methyl and vinyl-substituted polysiloxane, the temperatures at which the second stage takes place correspond to the release of volatile simple silane species such as SiH4 and CH3SiH3, along with hydrogen and ethane, among others [22]. These molecules originate from the rearrangement of the bonding scheme involving the exchange of Si–O bonds with Si–H and/or Si–C bonds. In our previous investigations on the products released during the pyrolysis of organochlorinated xerogels [21], we could not identify any silanes, but mainly small molecules like CO2 or HCl (accompanied with chloroethane) for ClMTEOS and ClETEOS, respectively, and larger species for ClPTEOS (cyclopropane, chloroethane) and ClPhTEOS (propene, chlorobenzene and a collection of chlorinated aromatics). The nature of the released vapours suggests that it is governed by dechlorination and chain-decomposition reaction mechanisms.

For all hybrid xerogels except ClETEOS, the thermal decomposition proceeds up to temperatures above 900 K with a further mloss. In the case of organopolysiloxanes, this high-temperature third process (ca. 1000 K) has been attributed to various cleavage reactions of Si–H and Si–C bonds accompanied with the release of CH4 and H2 and the generation of free carbon clusters within the final silicon oxycarbide ceramic [22]. The formation of a silicon oxycarbide cannot be disregarded for organochlorinated silica xerogels, but the vapours released were identified to be mainly chloromethane for ClMTEOS, cyclopropane for ClPTEOS and chlorobenzene for ClPhTEOS [21]. In all cases, these molecules were accompanied by benzene and other heavier molecules, such as alkenes and dienes (hexadiene for ClMTEOS, butene and cyclopentadiene for ClPTEOS) or aromatic compounds (naphthalene for ClMTEOS, toluene for ClPTEOS and styrene for ClPhTEOS). These findings align with the fact that the formation of heavy organic compounds through chain cyclisation and aromatisation require higher decomposition temperatures. Thus, the decomposition behaviour of the hybrid xerogels differs markedly compared to the TEOS reference, which constitutes 90% of the composition in the ClRTEOS materials, indicating that the silica matrix is more thermally stable, whereas the chlorinated organosilane moieties are the most thermally susceptible.

The decomposition of the ClRTEOS materials at different heating rates faster than 5 K min

−1 (

β = 10, 20, 30 and 40 K min

−1) exhibit analogous decomposition profiles with the upper limits of the decomposition stages shifting toward higher temperatures as

β increases (

Figure S1). The

mloss in the initial desolvation stage decreases slightly with increasing the heating rate, except for TEOS and ClPhTEOS. Both materials undergo an increase in

mloss within this stage, which is remarkable in the case of TEOS. Increasing

β causes thermal decomposition products to be released rapidly and the energy required for decomposition to be reached more quickly, as observed for these two xerogels (TEOS and ClPhTEOS). In the second stage, the

mloss decreases slightly as the heating rate

β becomes faster in all materials except TEOS. In contrast, slight increases of

mloss with

β are observed within the third stage

, ClPhTEOS having the bigger

mloss.

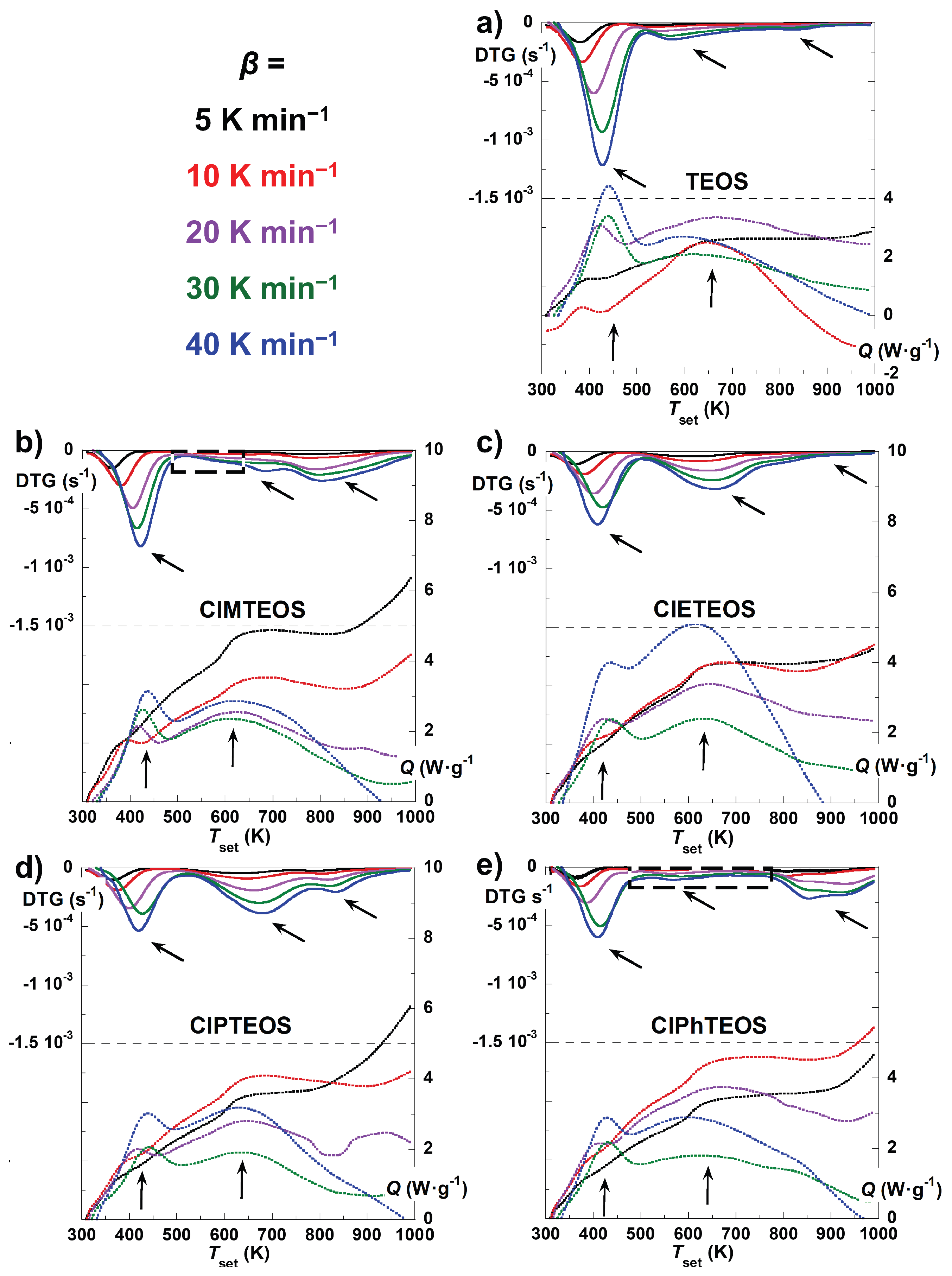

Figure 3 shows the thermal evolution of both the first time-derivative of the normalised mass (DTG, top solid curves) and the normalised heat flux (

Q, bottom dotted curves) of the TEOS reference and the four hybrid xerogels recorded at five different values of

β. The DTG curves exhibit up to three minima, each one corresponding to each of the three decomposition stages. In the case of TEOS, the

mloss above 750 K is negligible, thus the third stage cannot be confirmed from the

Q data. For ClPhTEOS and ClMTEOS, the second stage displays a notably flat profile (enclosed in a dashed box in

Figure 3), which may compromise the accuracy of subsequent kinetic calculations.

In the Q curves, the different endothermic signals are indicated on the graphs using arrows. For all the studied xerogels, the first two maxima are well defined and clearly distinguishable, while the third signal is in most cases not as clear because it is shadowed by that of the second stage and becomes difficult to be distinguished with enough definition. This third signal is best observed in the case of ClPTEOS, its maximum appearing centred at approximately 900 K. In all instances, the maxima corresponding to the second thermal stage display considerable width, suggesting that they likely encompass multiple overlapping processes of different nature.

2.2. Kinetic Analysis

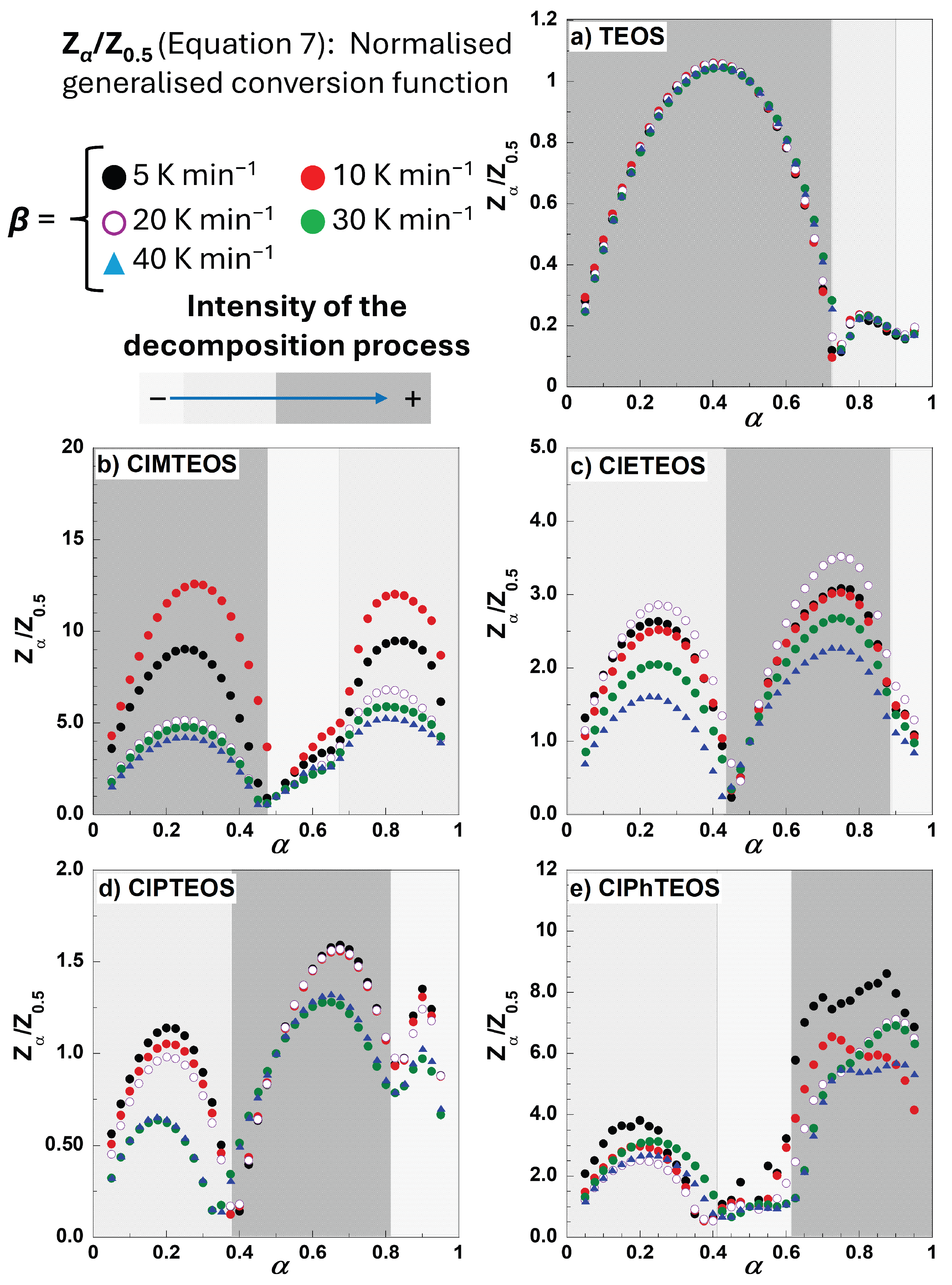

To perform a preliminary evaluation of the mechanism governing the global decomposition process, normalised Criado master plots were constructed for all xerogels after confirming that their T vs α plots for the five different heating rates do not intertwine significantly. The Criado master plots were obtained by following the methodology described in section 4.1 (see from equation 1 to 7) and the results are shown in

Figure 4.

The simplest behaviour is found in the case of TEOS, with the first stage serving as the principal governing process. For the organochlorinated xerogels, the first stage occurs at a conversion degree of approximately α = 0.4 (40% of the total mloss), whereas the second and subsequent stages differ markedly in both the shape and extent of decomposition. The transition between the second and the third stages is not well defined, especially for ClMTEOS and ClPhTEOS, as the Zα/Z0.5 curve does not reach a value of zero, indicating the initiation of an alternative mechanism. This transition is almost imperceptible for TEOS and ClETEOS.

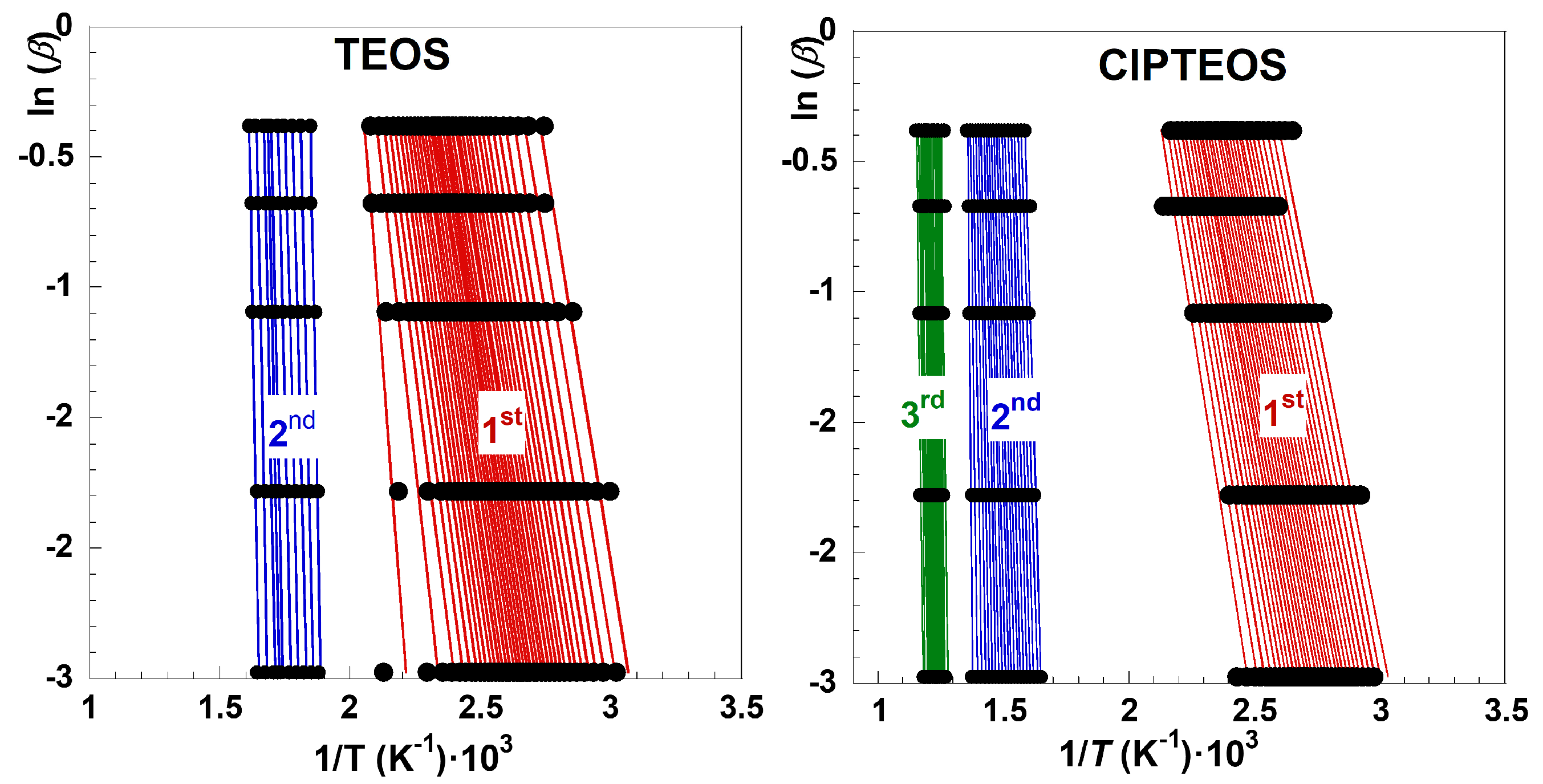

To determine the kinetic decomposition mechanism using an isoconversional method, the first task was to identify the temperature intervals over which each stage develops and to define the fraction of mass lost in each case. For this work, this identification was guided by the shaded regions marked in

Figure 4, determined by applying equation 4. According to the FWO method and by plotting ln(

β) against 1/

T within the

α = 0.05–0.95 using increments of 0.025 [29], linear trends with regression coefficients higher than 0.97 were obtained for TEOS and ClPTEOS, as shown in

Figure 5 (

Figure S2 collects the ln(

β) vs 1/

T plots for the remaining three xerogel samples). The corresponding slopes are parallel, except within those temperature intervals where different mechanisms overlap, denoting the independence of the decomposition with

β. This finding indicates a good agreement for the best fit to calculate the kinetic parameters.

Although α varies from 0 to 1 in both graphs in

Figure 5, the sensitivity of the study may not be equivalent within the whole range. The sensitivity will be linked to the relative mass loss of each stage, which is quite different for each xerogel sample studied in this work according to the results gathered in

Figure 2. For example, the

mloss associated with the first and second decomposition stages of TEOS corresponds to 14% and 6%

, respectively, whereas

mloss values of 8% and 12% are observed in the case of ClPTEOS, the third stage encompassing an additional

mloss of 1%. The slope of the ln(

β)

vs 1/

T lines increases as the stages evolve, and this trend was also found for rest of organochlorinated xerogels (

Figure S2).

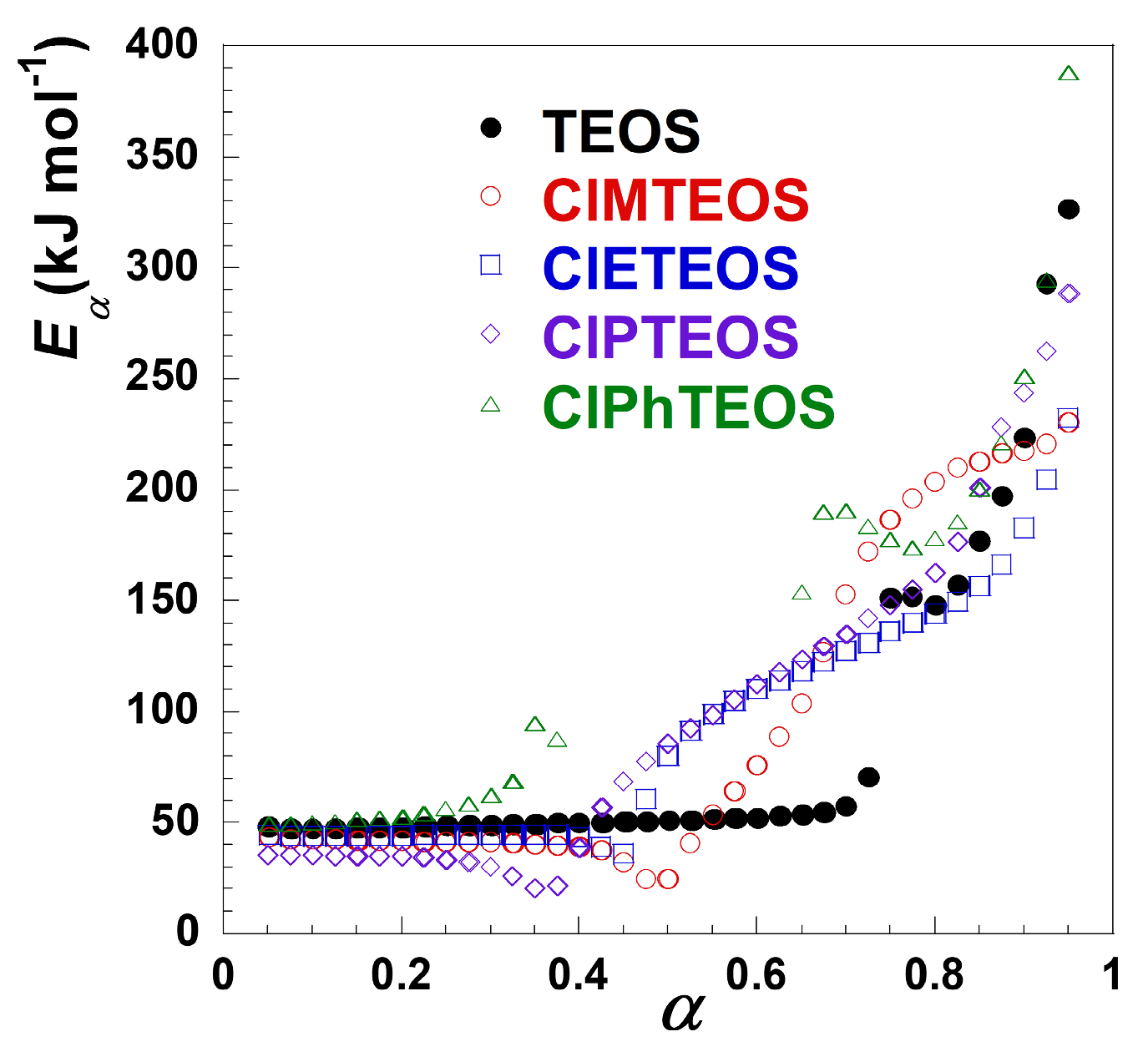

Figure 6 shows the variation of the activation energy (

Eα) with α obtained from the FWO method, where

Eα exhibits different values for each decomposition stage, confirming the multi-step nature of the thermal decomposition [30]. The progressive increase in Eα with each subsequent stage indicates stable decomposition reactions and consistent disorder degree [31].

Table 1 summarises the minimum and the maximum values of

Eα for each decomposition stage, which were calculated form the slope of the FWO plots using the methodologies described in section 4.1. The obtained values agree with the one found in the literature, considering that the errors are similar (in the 5–10% order), mainly due to the fitting of d

α/d

t [32].

For the first stage, the

Eα value ranges from 35 to 60 kJ mol

−1, which relates to the release of the surface physiadsorbed ethanol species. This process shows a direct correlation with the material textural properties, exhibiting higher

Eα values for samples with wider mesoporous distribution [16–18]. The second stage covers the thermal decomposition of the chlorinated organosilane moieties and further condensation of the Si–OH groups. For this stage, the Eα values increase progressively with the thermal decomposition evolution, likely due to reduced accessibility of free silanol groups within the matrix. For the organochlorinated xerogels, the dehydroxylation reaction becomes less significant due to the lower amount of TEOS used in their preparation, resulting in silica matrices with lower abundance of Si–OH groups. However, the use of a 10% molar content of ClRTEOS precursors introduces additional, alternative decomposition pathways due to the organochlorinated moieties. Furthermore, the collapse of the matrix porosity reduces the diffusion rate of decomposition products [33]. Notably, the determination of

Eα was precluded for ClMTEOS and ClPhTEOS due to the markedly flat DTG evolution in their second decomposition stages (marked with dashed boxes in

Figure 3). Kappert et al. reported that the

Eα values for the dehydroxylation reaction are highly dependent on the conversion degree, ca 150–300 kJ mol

−1, whereas the degradation of the functional group in organosilica matrices requires slightly lower values, 160–190 kJ mol−1 [33].

Crucially, both the second and third decomposition stages (occurring above 420–500 K, depending on

β) generate the most hazardous vapour species released from the thermal decomposition.

Table 2 summarises the predominant species identified during the thermal decomposition of the ClRTEOS xerogels in a recent work [21], along with the characteristic temperature ranges for each mass loss stage. The first stages are associated with the diffusion process of ethanol out of the silica network. The second stages originate mainly from the dehydroxylation of the material, together with minor decomposition of the organic fragments from ClRTEOS moieties. The Si–C bonds break at the same time, bringing out the isolation of additional siloxane (Si–O–Si) bonds, which hinders the convergence of silanol groups and increases the dehydroxilation activation energy as a result. Hence,

Eα increases with the conversion degree, and a higher value of energy is required for the thermal decomposition to proceed in agreement with the siloxane bonds stablished between the silanols. The third stage is only observed for ClMTEOS, ClPTEOS and ClPhTEOS and involves the highest

Eα values, most likely because it relates to cyclisation and aromatisation of the organic fragments. Based on these results, ClPTEOS and TEOS demonstrated the highest thermal stability, while ClPhTEOS showed the lowest stability among the studied materials.

The values of ∆

H calculated from equation 8 (

Figure S3) were positive for all stages, reflecting the well-known, endothermic nature of the decomposition process. The numerical values were slightly lower (ca. 3–8 kJ mol

−1) than those of the corresponding

Eα. The values of Δ

G were also calculated from equation 9 (

Figure S4), resulting in positive high values as corresponds to non-spontaneous processes, which increase with the temperature required for the thermal decomposition.

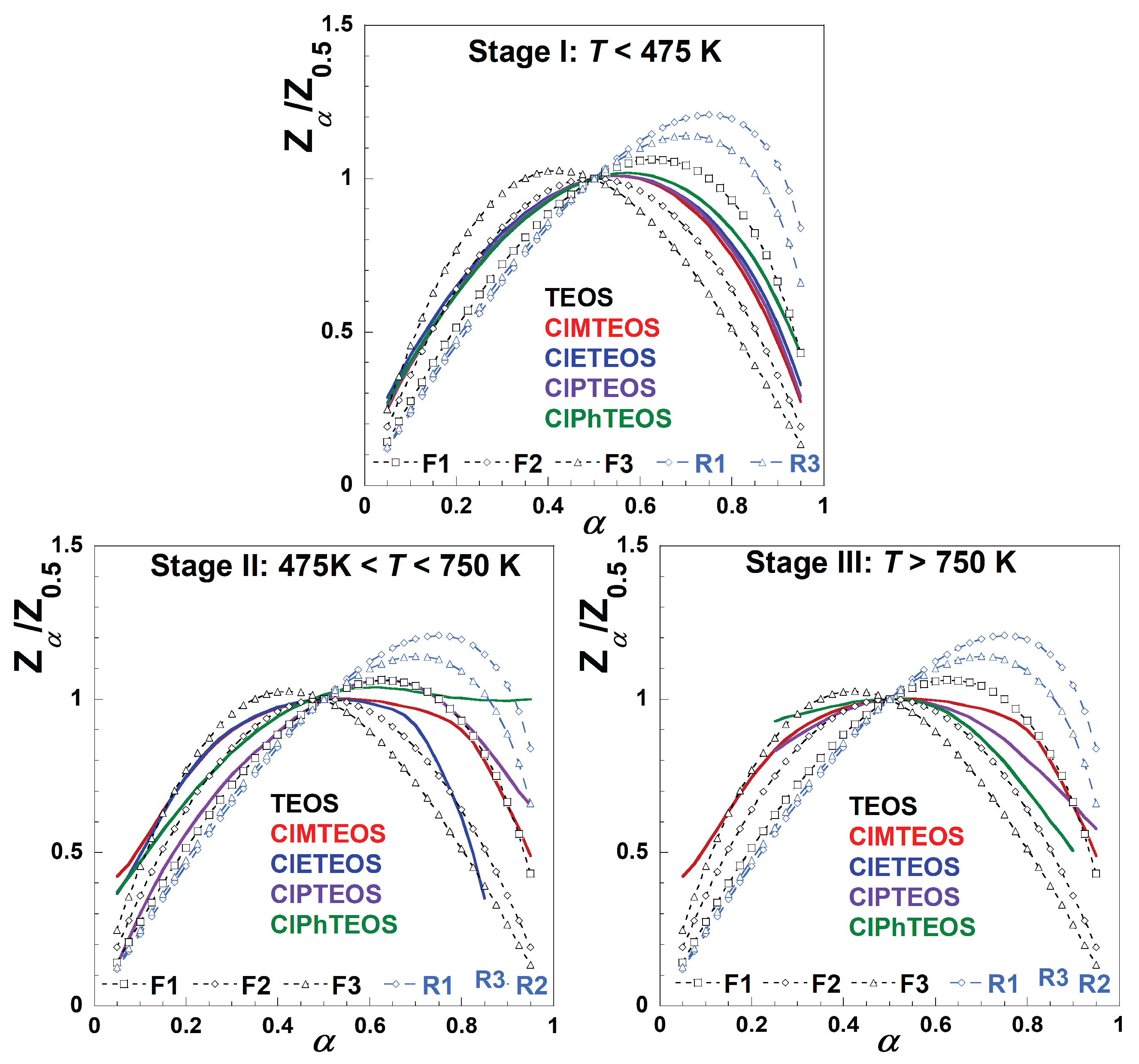

The Criado master plot technique was employed to evaluate the most probable reaction model for all samples. Equation 7 was used to plot the theoretical and reduced rate curves of Z

α/Z

0.5 against

α for each decomposition stage of each sample using the mathematical expressions of the main kinetic models collected in

Table S1. The best-fitting model was that of nth order kinetics, F

n.

Figure 7 shows the experimental Criado master plots at

β = 5 K min

−1 for the TEOS reference and the four ClRTEOS materials compared to the predicted values for first, second and third order,

f(

α) = (1-

α)

n, and for contracting geometrical models, being n = 1/2 for contracting area and n = 2/3 for contracting volume.

The comparison between the experimental and predicted Criado master plots for other considered models for solid-state reactions are included in

Figure S5. All the hybrid xerogels display a similar experimental behaviour and the F

n order models afforded the best fits. For the first stage, the experimental curve overlaps the F2 model when α is lower than 0.5, whereas at higher

α values the experimental evolution lies between the first and second order. The behaviour for the second stage depends on the specific nature of the chlorinated organosilane moiety. While ClPTEOS follows the F1 model for almost the whole

α range, the best fitting at

α values lower than 0.5 corresponds to F2 for ClPhTEOS, the xerogels with the shorter alkyl chains (ClMTEOS and ClETEOS) deviating from the F3 model toward the F2 at low

α values just above ca. 0.20. The trends above

α = 0.5 are complex and do not adjust to any model except for ClMTEOS, which approaches the F1 model at high conversion degree. In the third stage, the analysis is more complex and the evolution for all the xerogels is included between the models F1 and F2, which could be due to the scarce

mloss involved and the complex decomposition pathways resulting in silicon oxycarbide ceramics.

The selection of the best-fit reaction model was based on the calculation of the non-regression coefficient (R

2) and the lowest value of the root mean square error (RMSE). In the first stage the evolution is common for all matrices, with the second order being the one that fits the best. In the second and the third stages, the thermal degradation is more complex, as illustrated by the overlapping mechanisms in

Figure 7. A reaction order greater than one is the result of the decrease in the decomposition rate with increasing

mloss. In heterogeneous reactions such as those in the present study, the reaction could be diffusion-controlled across an unstable interface that is reducing by a sintering process, or the accumulation of products at the interface could even lead to an increase of the diffusion resistance along the decomposition process.

3. Conclusions

This study evaluated the thermal decomposition kinetics of various organochlorinated silica xerogels. The results demonstrate a multi-step decomposition mechanism, with two to three distinct mass loss stages observed for both a pure silica reference (TEOS) and a series of hybrid silica materials with chloroalkyl and chlorophenyl groups. This work also confirms that characteristic species previously identified by GC–MS studies are generated and released at each decomposition stage. These stages were: (i) the release of physiadsorbed solvent, (ii) dehydroxylation and dechlorination of the material, and (iii) breaking of bonds between organic groups and silicon centres with consequent cyclisation and aromatisation. Nevertheless, this study found that much more complex mechanistic pathways are involved in each of these stages.

The nature of the organic moieties directly influences the studied thermal properties. The series of materials synthesised using chloroalkyltriethoxysilanes (chloromethyl, 2-chloroethyl and 3-chloropropyl) follow quite different thermal decomposition mechanisms, whereas that of the 4-chlorophenyl-containing xerogel closely resembles the one determined for the chloromethyl derivative. This is due to the reaction between alkyl chains radicals, which can favour the release of organic compounds or the collapse of the surface.

The FWO method provided results consistent with literature. The Eα increased with the evolution of the thermal degradation at each stage. The exponential nucleation, random nucleation and nuclei growth and diffusion models were not representative for the decomposition of the studied xerogels. Reaction order models afforded the best fitting, with the second and third order being the most suitable for all materials except ClPTEOS, which was best fitted to the first order due to the cyclisation capacity of the 3-chloropropyl moiety.

These findings highlight the crucial importance of characterising the thermal stability of hybrid materials to ensure their safe and effective implementation in applications such as sensing devices. Since the temperature directly influences the sensor response characteristics, operating under thermal conditions above moderate temperatures can compromise the device performance. For the materials studied, a safe operational window below 450 K has been established to prevent thermal degradation and maintain the functionality.

4. Materials and Methods

Monoliths of the pure silica reference material (TEOS) and the four organochlorinated hybrid silica xerogels (ClMTEOS, ClETEOS, ClPTEOS, and ClPhTEOS) were obtained as described in previous works [16–18]. The xerogels were prepared through the sol–gel method in acidic conditions using blends of tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) and the corresponding ClRTEOS triethoxysilane (ClR substituent = ClM, chloromethyl; ClE, 2-chloroethyl; ClP, 3-chloropropyl; ClPh, 4-chlorophenyl) with a 90:10 molar ratio. A 10% content of organochlorinated groups is enough to the study of effect of the incorporation of such moieties into silica materials without compromising their structural integrity.

The monoliths were grounded and dried under vacuum for at least 12 h to extract their surface moisture before performing the thermogravimetric experiments (TGA/DTG), which were carried out under a N2 flow of 40 mL min−1 using a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 3+ series thermogravimetric analyser. Samples of approximately 15 mg were placed in 70 μL sapphire crucibles for thermal analysis from 303 to 1273 K at constant heating rates of 5, 10, 20, 30 and 40 K min−1.

4.1. Methodology of Kinetic Studies

For a single-step process, the reaction rate can be represented by the Equation (1):

where

k(

T) is the kinetic constant as a function of absolute temperature

T;

f(α) denotes the kinetic model function that depends on the reaction mechanism and the conversion degree α;

Aα is the Arrhenius pre-exponential factor, and

Eα represents the apparent activation energy. The kinetic model is defined in terms of the global conversion

α, which represents the mass fraction volatilised. For each decomposition stage,

α can be defined as follows:

where

mo,i,

mT,i, and

mf,i designate the initial, instantaneous, and final masses within each stage, respectively. Equation (3) displays the integral form of the kinetic model function,

g(

α):

This integral does not have an exact analytical solution, but it can be solved by numerical approximation methods or by using other approximations proposed in the literature. For example, the Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO) model [34] that employs the Doyle’s approximation [35] can be applied for 20 ≤

E/

R T ≤ 60 when the thermal decomposition is carried out a constant value of the heating rate

β. At these conditions, Equation (3) can be rearranged as follows:

For isoconversional data, g(α), Aα and Eα have constant values Thus, by registering the temperatures necessary (Tα) to reach a particular decomposition degree α at different heating rates β, the activation energy Eα can be calculated from the slope of linear ln β vs. 1/Tα plots (m = 1.052·Eα/R). The application of the isoconversional treatment allows to obtain Eα without considering any reaction model f(α).

For thermal processes developed at a constant heating rate (

β =d

T/d

t), Equation (3) can be written as the following temperature integral having an analytical solution

In this context, Criado proposed the use of the variable

Z(

α), which is defined as the product of differential and integral model contributions,

f(

α)

·g(

α), and the values of which can be easily calculated for each

α from experimental TGA/DTG data [24]. The expression of

Z(

α) is given in Equation (6):

The mathematical expressions of

f(

α) and

g(

α) are well known for numerous kinetic models and

Table S1 collects the equations for the main ones. Applying these expressions allows to calculate the theoretical values of Z

α for each

α. A Criado master plot consists of a representation against

α of the values of the variable

Z(

α), either experimental or theoretical, normalised with the corresponding value at

α = 0.5 according to Equation (7):

The comparison of experimental and theoretical data by means of Criado master plots allows identifying the predominant kinetic mechanism within a thermal decomposition process, of organochlorinated hybrid silica xerogels in this case.

The implementation of the FWO method has important limitations, the first and main one being that the thermal decomposition cannot depend on

β Other limitations relate to the linear behaviour of the ln

β vs 1/

T or ln

β vs ln

A plots.

Figure 1 schematises the calculation procedure followed in this work for implementing and validating the FWO method. Once the validation is satisfactorily completed, the molar enthalpy (

∆H) and Gibbs energy (

∆G) changes can be calculated through Equations (8) and (9) [36,37]:

where

Tm is the maximum decomposition temperature,

KB is Boltzmann constant (1.381·10

−23 J K

−1) and

h is Planck constant (6.626·10

−34 J s).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Evolution of the normalised mass as a function of the programmed temperature for the TEOS reference and the four organochlorinated ClRTEOS materials at heating rates of 10, 20, 30 and 40 K min−1; Figure S2: Linearity of the FWO method for the thermal decomposition of ClMTEOS, ClETEOS and ClPhTEOS using ln(β) vs 1/T plots within the α = 0.05–0.95 range with increments of 0.025; Figure S3: Dependence of the molar enthalpy change with α for the TEOS reference and the four organochlorinated ClRTEOS xerogels; Figure S4: Dependence of the Gibbs energy change with α for the TEOS reference and the four organochlorinated ClRTEOS xerogels; Figure S5: Criado master plots for the three decomposition stages of the TEOS reference and the four organochlorinated ClRTEOS materials using the different Pn, An, Dn, and Rn models collected in Table S1; Table S1: Fitting performance of various kinetic models with different values of f(α) and g(α).

Author Contributions

B.R.-R.: investigation, data curation and writing—original draft. G.C.-Q.: formal analysis, writing—review and editing. P.P.: investigation. S.R.: funding acquisition, writing—review and editing.; C.E.: writing—review and editing.; G.A.: data curation, writing—review and editing.; M.V.L.-R.: writing—review and editing; J.J.G.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the projects PID2020-113558RB-C42, PID2022-137437OB-I00 and PID2022-142169OB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

J.J.G. and S.R., C.E. and M.V.L.-R. acknowledge the financial support from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Government of Spain and the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación (projects PID2020-113558RB-C42, PID2022-137437OB-I00 and PID2022-142169OB-I00, respectively). The authors thank the technical and human resources from UCTAI (UPNA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TEOS |

Tetraethoxysilane |

| ClMTEOS |

(Chloromethyl)triethoxysilane |

| ClETEOS |

(2-Chloroethyl)triethoxysilane |

| ClPTEOS |

(3-Chloropropyl)triethoxysilane |

| ClPhTEOS |

(2-Chlorophenyl)triethoxysilane |

| FWO |

Flynn–Wall–Ozawa |

|

Eα

|

Activation energy |

| ΔH

|

Variation of the molar enthalpy |

| ICTAC |

International Confederation of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry |

| An |

Nucleation and growth models |

| Dn |

Diffusion models |

| Fn |

n-Order models |

| Rn |

Geometrical contraction |

| α |

Conversion factor |

| β |

Heating rate |

|

mloss

|

Mass loss |

| Q |

Heat flux |

| Zα/Z0.5

|

Normalised generalised conversion function |

References

- Ochoa, M.; Durães, L.; Matos Beja, A.; Portugal, A. Study of the suitability of silica based xerogels synthesized using ethyltrimethoxysilane and/or methyltrimethoxysilane precursors for aerospace applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2012, 61, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottathara, Y.B.; Bobnar, V.; Finšgar, M.; Grohens, Y.; Thomas, S.; Kokol, V. Cellulose nanofibrils-reduced graphene oxide xerogels and cryogels for dielectric and electrochemical storage applications. Polymer 2018, 147, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Gwon, K.; Kim, H.; Park, B.J.; Shin, J.H. High-performance amperometric carbon monoxide sensor based on a xerogel-modified PtCr/C microelectrode. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 369, 132275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myadam, N.L.; Nadargi, D.Y.; Gurav Nadargi, J.D.; Shaikh, F.I.; Suryavanshi, S.S.; Chaskar, M.G. A facile approach of developing Al/SnO2 xerogels via epoxide assisted gelation: A highly versatile route for formaldehyde gas sensors. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 116, 107901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.K.; Maimunawaro; Rahma, A.; Syauqiah, I.; Elma, M. Functionalization of hybrid organosilica based membranes for water desalination – Preparation using Ethyl Silicate 40 and P123. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 31, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, L. Pre-coagulation with cationic flocculant-composited titanium xerogel coagulant for alleviating subsequent ultrafiltration membrane fouling by algae-related pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, F.T.; Machado, V.G. Hybrid films composed of ethyl(hydroxyethyl)cellulose and silica xerogel functionalized with a fluorogenic chemosensor for the detection of mercury in water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 304, 120480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Kan, X.-T.; Zhou, Q.; Niu, Y.-B.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Wei, T.-B.; Lin, Q. Lanthanide-mediated cyclodextrin-based supramolecular assembly-induced emission xerogel films: A transparent multicolor photoluminescent material. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 13048–13055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styskalik, A.; Kordoghli, I.; Poleunis, C.; Delcorte, A.; Aprile, C.; Fusaro, L.; Debecker, D.P. Highly porous hybrid metallosilicate materials prepared by non-hydrolytic sol-gel: Hydrothermal stability and catalytic properties in ethanol dehydration. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 297, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styskalik, A.; Kordoghli, I.; Poleunis, C.; Delcorte, A.; Moravec, Z.; Simonikova, L.; Kanicky, V.; Aprile, C.; Fusaro, L.; Debecker, D.P. Hybrid mesoporous aluminosilicate catalysts obtained by non-hydrolytic sol–gel for ethanol dehydration. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 23526–23542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-J.; Teng, S.-H.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Qian, H.-S. Green strategy to develop novel drug-containing poly (ε-caprolactone)-chitosan-silica xerogel hybrid fibers for biomedical applications. J. Nanomater. 2020, 2020, 6659287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendels, S.; de Souza Porto, D.; Avérous, L. Synthesis of biobased and hybrid polyurethane xerogels from bacterial polyester for potential biomedical applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.E.; Durán, A.; Balda, R.; Fernández, J.; Mather, G.C.; Castro, Y. A new sol-gel route towards Nd3+-doped SiO2-LaF3 glass-ceramics for photonic applications. Mater. Adv. 2020, 1, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, R.R.C.; Zanoni, K.P.S.; de Oliverira, M., Jr.; de Vicente, F.S.; de Camargo, A.S.S. Structural and photophysical characterization of highly luminescent organosilicate xerogel doped with Ir(III) complex. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2022, 102, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Reina, B.; López-Torres, D.; Cruz-Quesada, G.; Espinal-Viguri, M.; Elosúa, C.; Reinoso, S.; Garrido, J.J. Tuning the sensitivity of photonic sensors toward alkanes through the textural properties of hybrid xerogel coatings. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2413871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Quesada, G.; Espinal-Viguri, M.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Garrido, J.J. Novel organochlorinated xerogels: From microporous materials to ordered domains. Polymers 2021, 13, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Quesada, G.; Espinal-Viguri, M.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Garrido, J.J. Hybrid xerogels: Study of the sol-gel process and local structure by vibrational spectroscopy. Polymers 2021, 13, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Quesada, G.; Espinal-Viguri, M.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Garrido, J.J. Novel silica hybrid xerogels prepared by co-condensation of TEOS and ClPhTEOS: A chemical and morphological study. Gels 2022, 8, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.; Soler-Illia, G.J.; de A.A. Soler-Illia, G. J.; Ribot, F.; Lalot, T.; Mayer, C.R.; Cabuil, C. Designed hybrid organic-inorganic nanocomposites from functional nanobuilding blocks. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 10–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Mortalò, C.; Comune, L.; Raffani, G.; Fiorentino, M.; Catauro, M. Sol–gel synthesized silica/sodium alginate hybrids: Comprehensive physico-chemical and biological characterization. Molecules 2025, 30, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Reina, B.; Cruz-Quesada, G.; Pujol, P.; Reinoso, S.; Elosúa, C.; Arzamendi, G.; López-Ramón, M.V.; Garrido, J.J. Determination of hazardous vapors from the thermal decomposition of organochlorinated silica xerogels with adsorptive properties. Environ. Res. 2024, 256, 119247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Garrido, C.; Sánchez-Jiménez, P.E.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Perejón, A.; Criado, J.M. Combined TGA-MS kinetic analysis of multistep processes. Thermal decomposition and ceramification of polysilazane and polysiloxane preceramic polymers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 29348–29360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortezaeikia, V.; Tavakoli, O.; Khodaparasti, M.S. A review on kinetic study approach for pyrolysis of plastic wastes using thermogravimetric analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 160, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, J.M. Kinetic analysis of DTG data from master curves. Thermochim. Acta 1978, 24, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liang, Q.; Hou, H. Thermal decomposition mechanism and kinetics of Pd/SiO2 nanocomposites in air atmosphere. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 135, 2733–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açikalin, K. Determination of kinetic triplet, thermal degradation behaviour and thermodynamic properties for pyrolysis of a lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Jiménez, P.E.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Perejón, A.; Criado, J.M. Generalized kinetic master plots for the thermal degradation of polymers following a random scission mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010, 114, 7868–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiya-Prabhakaran, S.P.; Swaminathan, G.; Viraj, V.J. Thermogravimetric analysis of hazardous waste: Pet-coke, by kinetic models and Artificial neural network modeling. Fuel 2021, 287, 119470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.A.D.; Cardoso de Morais, L. Kinetic parameters of red pepper waste as biomass to solid biofuel. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 204, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.H. Investigation of thermodynamic parameters in the thermal decomposition of plastic waste−waste lube oil compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5313–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anca-Couce, A.; Tsekos, C.; Retschitzegger, S.; Zimbardi, F.; Funke, A; Banks, S.; Kraia, T.; Marques, P.; Scharler, R.; de Jong, W.; Kienzl, N. Biomass pyrolysis TGA assessment with an international round robin. Fuel 2020, 276, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappert, E.J.; Bouwmeester, H.J.M.; Benes, N.E.; Nijmeijer, A. Kinetic analysis of the thermal processing of silica and organosilica. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 5270–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, T. Kinetics of non-isothermal crystallization. Polymer 1971, 12, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.D. Estimating isothermal life from thermogravimetric data. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1962, 6, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muigai, H.H; Choudhury, B.J.; Kalita, P.; Moholkar, V.S. Co-pyrolysis of biomass blends: Characterization, kinetic and thermodynamic analysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 143, 105839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Jiang, K.; Chen, Y.; Lei, Z.; Chen, K.; Cheng, X.; Qi, J.; Xie, J.; Huang, X.; Jiang, Y. Kinetics and thermodynamic analysis of recent and ancient buried Phoebe zhennan wood. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20943–20952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).