1. Introduction

Motivation and context. Multimessenger observations (e.g., GW170817/GRB170817A) enforce luminal gravitational waves today, severely constraining tensor-sector deviations from GR and motivating symmetry-driven routes that deliver without fine tuning. At the same time, long-standing work in Einstein–Cartan/metric–affine (EC/MAG) geometry shows how torsion and non-metricity can be organized consistently, while Palatini-type modified gravity (notably Palatini ) has faced well-documented pitfalls when matter is included. This paper asks a focused question: Can one formulate a first-order (Palatini) framework whose observable sector is (i) -even by construction, (ii) closed at quadratic order with at most one derivative per building block, (iii) exactly luminal for tensor modes by a structural identity, and (iv) free of extra propagating degrees of freedom?

Posture and scope. We work with independent vierbein

and a metric-compatible spin connection

, and we enforce a

scalar projector

on

observable scalar densities. On oriented

-manifolds, the combined

preserves orientation and commutes with the Hodge dual, so scalar densities can be projected to

-even pieces;

-odd scalar densities are discarded as unobservable (real) expectation values. An internal phase

(Stueckelberg compensator) enters the observed sector only through its gradient; we adopt a

spurion limit (not varied) at quadratic order. Global assumptions A1–A6 (domain/measure;

; projection/variation commutes on scalar densities; boundary/topology posture with Nieh–Yan as boundary; two-derivative closure) delimit the posture (

Section 2). A quick notation table appears in Section 2.3 for ease of reference.

Projective symmetry and the invariant trace. Palatini geometry admits projective shifts

To keep the

projected observable sector invariant, we introduce a compensator whose gradient shifts as

and work with the projectively invariant trace

Within the two-derivative posture, all observables depend on

only through

via

.

Quadratic basis (one-derivative per factor). At quadratic order, the projected, real invariants we use are

together with improvement currents

that are pure boundary under A4–A5.

All three results hold at quadratic order, within A1–A6 and the scalar- observable sector.

(C1) Conditional Palatini– uniqueness under trace-lock (A6). Algebraic torsion consistent with the scalar projector is uniquely pure trace and aligned with : and the surviving quadratic invariant satisfies

|

| |

|

(C2) Three-chain bulk equivalence (mod boundary). After projection and using C1, three constructive routes collapse to the same bulk quadratic piece: No all-order equivalence is claimed. |

| |

|

(C3) Coefficient locking ⇒ exact luminality. Eliminating TT–nonTT mixing fixes a unique weight so that and hence the TT block is exactly luminal: A TT-gauge weak-field representative of (Minkowski; slowly varying ) is listed in Section 7.1; a covariant FRW representative appears in Appendix D. |

Plain-language gist (reader’s guide).

What we do: (i) keep only

-even scalar observables; (ii) use a compensator so only the

trace of torsion in the invariant combination

matters; (iii) show three seemingly different quadratic routes give the

same bulk physics (C2); (iv) choose coefficients once and for all to kill mixing, which forces

(C3).

What you can test: a unique next-to-leading dispersion

for multi-band GW data (PTA/LISA/LVK), detailed in Section 9; if a

slope is absent where EFT is valid, this posture is disfavored.

Falsifiable diagnostics (paper-level). Within A1–A6, any of the following falsifies the framework at quadratic order:

(C1 fails) Robust axial/traceless torsion signals in observables, or inability to realize , with .

(C2 fails) Disagreement of bulk coefficients among rank-one determinant (ROD), closed-metric (CM), and -even CS/Nieh–Yan routes once improvements are accounted for; the flux ratio on admissible domains.

(C3 fails) No coefficient choice achieves , or persists after locking on admissible patches.

Positioning relative to prior lines. In EC/MAG, axial/traceless torsion can propagate; here they are algebraically removed in the analyzed sector (C1). Parity-odd (dynamical) Chern–Simons gravity ties tensor effects to a pseudo-scalar; our -projected, even-parity sector achieves luminality by an equal-coefficient identity (C3), modulo improvements. Nieh–Yan contributes only boundary counterterms under A5 and does not alter bulk equations. The three-chain collapse (C2) is a rank-one, quadratic statement: ROD, CM, and the -even CS/Nieh–Yan shadow share the same bulk piece , differing only by .

Organization and stability notes.

Section 2 fixes A1–A6 and the scalar projector;

Section 3 and

Section 4 prove C1;

Section 5 proves C2 and defines flux-ratio diagnostics;

Section 6 and

Section 7 implement locking and prove

(C3), also giving

representatives; matter couplings and the data-facing NLO piece appear in

Section 8 and

Section 9. Locking is stable on generic patches: the

mixing determinant scales as

with

, so rank loss occurs only on the measure-zero set

.

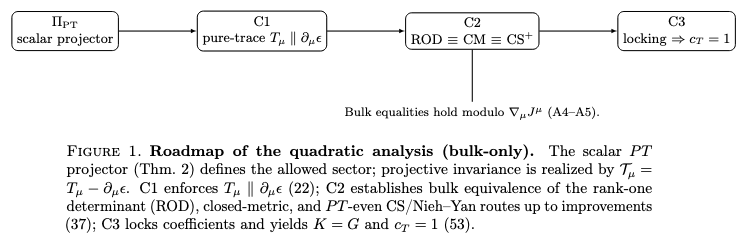

Figure 1.

Roadmap of the quadratic analysis (bulk-only). The scalar

projector (Thm. 2) defines the allowed sector; projective invariance is realized by

. C1 enforces

(

22); C2 establishes bulk equivalence of the rank-one determinant (ROD), closed-metric, and

-even CS/Nieh–Yan routes up to improvements (

37); C3 locks coefficients and yields

and

(

53).

Figure 1.

Roadmap of the quadratic analysis (bulk-only). The scalar

projector (Thm. 2) defines the allowed sector; projective invariance is realized by

. C1 enforces

(

22); C2 establishes bulk equivalence of the rank-one determinant (ROD), closed-metric, and

-even CS/Nieh–Yan routes up to improvements (

37); C3 locks coefficients and yields

and

(

53).

2. Global Assumptions & the Scalar Projector

We work on an oriented

-dimensional spacetime with independent vierbein

and a metric-compatible spin connection

(Palatini posture). Greek indices

are spacetime; Latin

are Lorentz-frame indices with

. Torsion and curvature are

Observable

scalar densities are mapped to a real,

-even sector by a projector

defined below. The internal phase

is a

spurion: it enters observables only via

and is not varied in the posture adopted here.

Physical Motivation for the Scalar Projector

We restrict

observable scalar densities to the

-even, real sector for two reasons: (i) on oriented

-manifolds the combined

preserves orientation and commutes with the Hodge dual ∗, so the Levi–Civita

density (weight

) is

-even; (ii) by the anti-linearity of

T, expectation values of

-odd scalar densities are purely imaginary and thus unobservable as real densities. We therefore average a scalar with its

image and take the real part, Equation (

8). This is a

posture on observables, not on fields. The commutation Lemma 1 and a minimal counterexample with

render the posture directly checkable in our setup.

2.1. Projective Symmetry and the Stueckelberg Spurion

Palatini geometry admits a

projective symmetry under which the connection shifts as

To maintain invariance of the

-even observable sector

after imposing the scalar projector, we introduce a Stueckelberg compensator

whose gradient transforms as

and we work with the projectively invariant trace combination

Within the

two–derivative truncation adopted here, we take the

spurion limit in which dynamical fluctuations of

are frozen; thus the allowed

-even scalar sector depends on

only through

. Combined with A1–A5, this ensures that the scalar projector commutes with variation on scalar densities (Lemma 1). In

Section 3 we enumerate the resulting quadratic basis, and in

Section 4,

Section 5,

Section 6 and

Section 7 we show how (C1) aligns

with

so that

at the level analyzed.

Assumption Posture at a Glance (A1–A6; observable scalars are -even and real).

-

A1

-invariant domain/measure. For any scalar density X, . Used in: self-adjointness of and projector identities (Thm. 2); route-flux diagnostics in Section 5. -

A2

Orientation and Hodge dual. The combined preserves the chosen orientation and on forms. Used in: parity of Levi–Civita density and commuting with ∗; boundary accounting. -

A3

Projection commutes with variation. For scalar densities, . Used in: Palatini variation and irrep block-diagonalization ( Section 4). Checkable proof: Lemma 1 below. -

A4

Topology/boundary posture. Work on trivial patches or impose -invariant boundary flux so that improvement currents are pure gauge (no extra canonical pairs). Used in: null tests and flux ratios ( Section 5); DoF count ( Section 7). -

A5

Nieh–Yan as boundary counterterm. affects only boundary conventions; no bulk Euler–Lagrange effect. Used in: three-chain equivalence modulo total derivatives ( Section 5). -

A6

Trace-lock posture. We enforce via an algebraic Lagrange current. Under A4 this introduces no new canonical pairs and only removes a -even bilinear independence at quadratic order.

|

Sufficient conditions for A1. On oriented Lorentzian patches with the standard measure and -invariant boundaries (compact or AF/FRW fall-offs), the pullback by preserves both the integration domain and the measure, hence for scalar densities.

Sufficient conditions for A2. If preserves the chosen orientation and the metric used for index operations, then commutes with the Hodge dual on forms: .

Action of on Densities

Let

act as standard discrete isometries;

T is anti-linear (complex conjugation). On oriented

-manifolds, the combined

preserves orientation, so for the Levi–Civita

density (weight

) we have

Assumption A2 implies

. Consequently, a scalar of the form

is

-even iff X is -even.

2.2. Scalar Projector: Definition and Basic Properties

The combined

acts anti-linearly on complex-valued densities (complex conjugation accompanies time reversal). On scalar densities we define

Self-adjointness on real scalars. Using A1 and

,

Lemma 1 (Project–vary commutation on scalar densities). Let act on complex-valued scalar densities with A1 (PT-invariant domain/measure) and A4 (fall-offs) imposed. If the spurion ϵ is non-variational and variations act only on with compact support or admissible fall-offs, then and is self-adjoint on real scalars.

Proof. Anti-linearity of T affects only ; variations here are real-linear on , and is fixed. With A1, implies on real scalars (self-adjointness). Then , where boundary terms vanish by A4. □

Function-analytic hypotheses and a minimal counterexample. Assume (scalar densities), or with A4 fall-offs, and the spurion is non-variational. Since T is anti-linear (complex conjugation), acts as . Under these conditions is real-linear and .

If, however, is varied, the commutation may fail. Let with a real . Then (purely -odd), but when . Hence . This shows why we hold fixed (spurion posture).

Admissible variation space. Variations act on with compact support or with A4 fall-offs: on AF patches with ; on FRW slices, , for some . The spurion is nondynamical (no variation) and T’s anti-linearity only sends . Under these conditions is real-linear and boundary fluxes vanish, so holds term-by-term.

Variational domain for

identity. We take variations with compact support on spatial slices or with FRW/AF fall-offs:

,

,

with

. Then

and

2.3. Quick Tables (Projection-Ready)

Objects. (Signs indicate intrinsic

P/

T parities;

T is anti-linear.)

| Object |

P |

T |

Note |

|

+ |

+ |

vierbein (metric from its square) |

|

+ |

− |

spin connection |

|

+ |

− |

torsion 2-form components |

|

+ |

+ |

curvature 2-form components |

|

(spurion) |

+ |

− |

enters observables via only |

|

− |

+ |

flips under P; T anti-linear |

|

− |

− |

pseudo-density (weight ); ; by A2 |

Scalar monomials and the projector.

| Monomial |

|

|

|

even |

survives; real by definition |

|

even |

survives; real under projection |

|

even even |

kept iff X is -even; else projected out |

|

even |

survives pre-lock; reduces to after C1/trace-lock |

|

(vector density) |

— (total deriv.) |

boundary-only under A4; unaffected except taking real part |

2.4. Selection Rules Under the Scalar Projector

Theorem 2 (Selection rules)

. Under A1–A5 and (A2), for any complex scalar density ,

In particular, for admissible tensors X,

Sketch. By definition (

8),

averages an object with its

image and then takes the real part. With A1,

ensures self-adjointness (

9) on real scalars. A2 implies

preserves orientation and commutes with ∗. Since the Levi–Civita

density is

-even while

T is anti-linear,

inherits the

parity of

X, yielding the conditional statement above. Products such as

are

-even (see the quick table), hence survive the projector; their later reduction to

uses the trace-lock/C1 map (

Section 3 and

Section 4).

Roadmap and Where Each Assumption Enters

The definitions and rules above are the only projectors/boundary tools used later. In particular:

Section 3 (allowed sector/closure): we enumerate all

-even quadratic monomials with at most one derivative per building block.

Pre-lock the basis includes

,

, and

.

Post-lock (trace-lock or C1) maps

.

Section 4 (C1): A3 enables

project-then-vary in the Palatini connection equation; A2/A5 prevent hidden pseudo-scalar contaminations; A4 controls improvements.

Section 5 (C2, scheme): A5 (

boundary) and A1/A4 underwrite the equality of route-wise bulk pieces and flux-ratio diagnostics, all written with the sign-compensated invariant

.

Section 6 and Section 7 (C3): A1/A4 guarantee that improvement currents do not alter kinetic/gradient coefficients; A3 is used implicitly in all quadratic variations; the equal-coefficient identity is a total divergence on the admissible variational domain.

Boundary/Topology Posture And Fall-Offs (Pointer)

Assumption A4 is realized either by compact -invariant domains with vanishing flux or by standard asymptotically flat/FRW fall-offs; the explicit statements and the symplectic-flux check are compiled in Appendix A (boundary notes therein). We exclude torsion defects and multi-valued patches that would violate the projector’s scalar posture.

3. Palatini Setting and the Allowed -Even Scalar Sector

We work in the Palatini posture with independent vierbein

and a metric-compatible spin connection

. Throughout this section the global assumptions A1–A6 and the scalar

projector of

Section 2 are in force, together with the selection rules of Theorem 2.

All scalar densities are implicitly projected, hence real and -even. We also retain the

two–derivative truncation and the spurion posture: the internal phase

enters observables only through its gradient and is not varied.

3.1. Projectively Invariant Starting Point

As reviewed in

Section 2.1, Palatini geometry admits a projective symmetry under which the torsion trace shifts and is compensated by the gradient of

. We therefore formulate the allowed sector in terms of the

projectively invariant combination

Within the spurion limit (two–derivative regime; frozen

dynamics), PT–even observables depend on

only through

. In

Section 4 we will show that the Palatini equations together with the trace-lock posture (C1) align

with

, effectively setting

on admissible patches. The present section establishes the corresponding

operator basis and its closure properties before and after this lock.

3.2. Normalized Spurion Direction and Canonical Rank-One Tensor

It is convenient to record the projected spurion scalar and the normalized direction of

:

From

we define a

dimensionless, traceless rank-one tensor

The (dimension-one) torsion trace scale along

will be denoted

When

we work on

patches and extend by continuity via a smooth regulator

,

. We emphasize the notational distinction:

is the projectively invariant

trace vector (

13), while

in (

15) is a traceless rank-one

matrix built from

.

3.3. What the Projector Allows (Pre- vs. Post-Lock)

By Theorem 2 and the parity assignments of

Section 2, the following quadratic monomials with at most one derivative per building block are

-even and thus survive the scalar projector:

The mixed bilinear

is therefore

independent pre-lock.

1 Once the Palatini–

uniqueness map (C1;

Section 4) or, equivalently, the trace lock is enforced,

and the mixed bilinear collapses to the spurion scalar.

For later reference we summarize the fate of the monomials:

| Monomial |

|

Projected fate (pre-lock → post-lock) |

|

even |

survives → survives |

|

even |

survives → survives |

|

even |

survives, independent →

|

|

— |

improvement → improvement |

3.4. Two-stage closure at one-derivative order

Allowing at most one derivative per building block and working to quadratic order, the projected, real,

-even scalar sector closes in two stages:

The self-adjointness of

on real scalars (

9) and A4 (boundary posture) justify the integration-by-parts steps implicit in (

18).

Lemma 3 (Two-stage closure)

. Under A1–A5, any -even quadratic scalar density with at most one derivative per factor satisfies

for some real constants and an improvement current . After enforcing ,

with and a (possibly shifted) improvement current .

3.5. Action skeleton (pre- and post-lock) and invariant notation

A minimal bulk skeleton compatible with the closure is

with

. After the lock (C1) this becomes

so the sole effect of

at this order is a renormalization of the

coefficient.

For compactness we also introduce the torsion quadratic invariant (projected, real)

and, when convenient, its sign-compensated version

. In

Section 4 we will show that C1 implies

, so that the post-lock basis may be written as

.

Order of Operations and Consistency

The scalar projector acts at the level of

densities; by Lemma 1 (

Section 2) we may

project then vary or

vary then project on scalar densities. The trace lock is an

algebraic enforcement at the level of equations of motion (or via a Lagrange current); it is not a projection and introduces no new canonical pairs under A4. Accordingly, the pipeline for the quadratic sector is:

Paper-level null test. On any admissible background with A4 fall-offs, every projected, -even quadratic density with at most one derivative per building block reduces pre-lock to up to a total derivative, and post-lock to up to a total derivative. An explicit constructive reduction appears in the Appendix.

4. Uniqueness Theorem (C1)

Within A1–A6 and the scalar- observable sector, at quadratic order with at most one derivative per building block, the Palatini connection equations fix algebraic torsion to be pure trace aligned with the spurion gradient. Equivalently,

so that the axial and traceless irreps vanish,

and

. Using the standard irrep identity,

Here

is the

projected, real scalar, and we use the shorthands from Section 2.3:

and

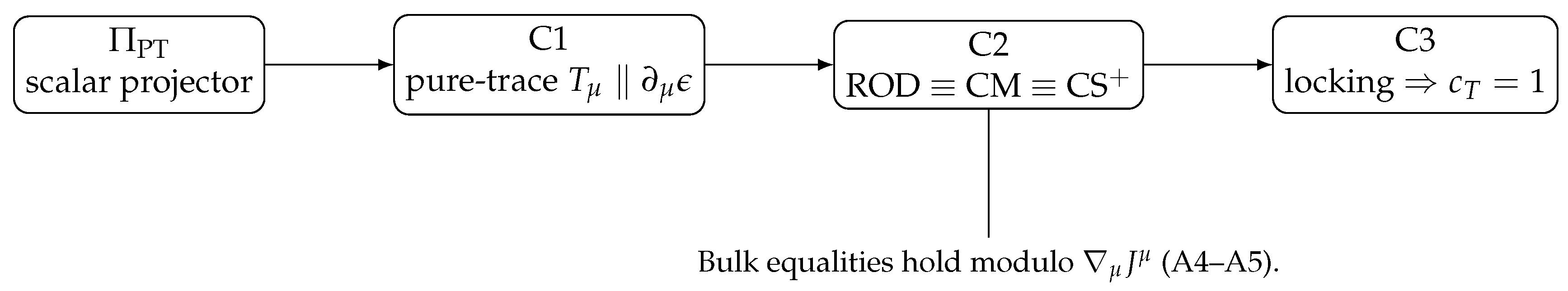

Figure 2.

Irreducible torsion content at quadratic order (log–log view). Ratios of projected scalar strengths comparing the pure-trace block against the axial and traceless blocks, shown as trace/axial and trace/tensor on logarithmic axes. The Palatini algebraicity (

Section 4.2) and the

projector drive axial and traceless pieces to zero, leaving the pure-trace map (

22) as the unique survivor. [nb:

fig_c1_pure_trace.py].

Figure 2.

Irreducible torsion content at quadratic order (log–log view). Ratios of projected scalar strengths comparing the pure-trace block against the axial and traceless blocks, shown as trace/axial and trace/tensor on logarithmic axes. The Palatini algebraicity (

Section 4.2) and the

projector drive axial and traceless pieces to zero, leaving the pure-trace map (

22) as the unique survivor. [nb:

fig_c1_pure_trace.py].

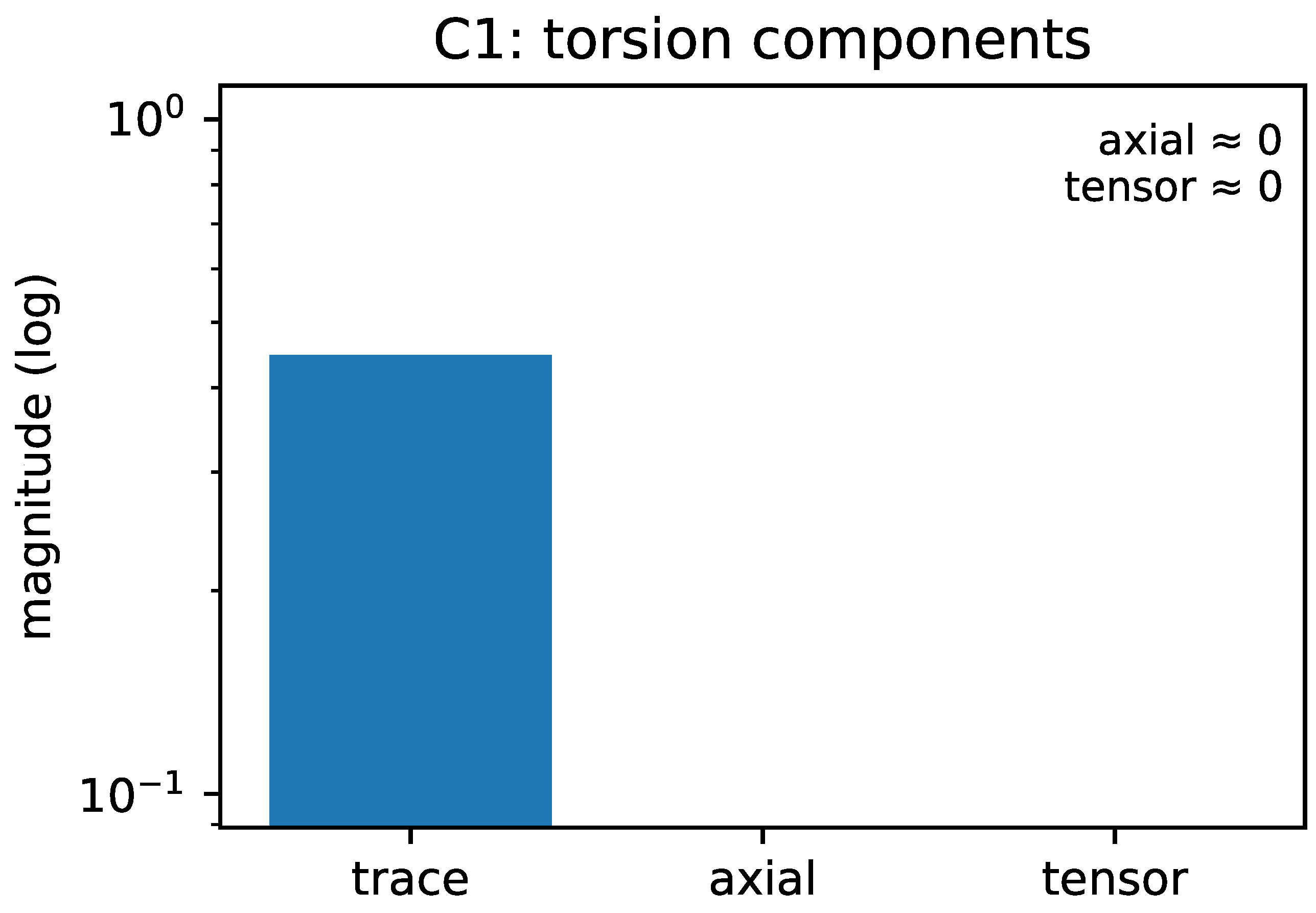

Figure 3.

Connection decomposition and the C1 map. Top: the Levi–Civita/contorsion split

. Bottom: torsion irreps

and the C1 alignment

,

,

(

22), which implies

(

23).

Figure 3.

Connection decomposition and the C1 map. Top: the Levi–Civita/contorsion split

. Bottom: torsion irreps

and the C1 alignment

,

,

(

22), which implies

(

23).

4.1. Most General Local Linear Ansatz (One Derivative)

At the derivative order relevant for the quadratic analysis, the only covector available is

and the invariant tensors are

and

. The

most general Lorentz-covariant

linear ansatz is therefore

with real

and where

denotes any attempted

traceless mixed-symmetry piece built from a single vector.

Proposition B.1

(single-vector no-go; Appendix B). From one vector one cannot construct a nonzero traceless torsion irrep obeying and . Any such attempt reduces to the span of and .

By Prop. B.1 the last term in (

24) is trivial, and the ansatz reduces to

The scalar projector (

Section 2) removes all

-odd

scalars, but it does not by itself force

; the Palatini equations will.

Proposition 4 (Palatini vector block ⇒ collinearity). With at most one derivative per building block and a single covector available, the algebraic connection equation in the vector irrep forces on admissible patches (A4).

Proof. Use the reduced ansatz (

25) and the blockwise non-degeneracy (Lemma 5). At this order the only covector in the vector block is

; any orthogonal component would require additional derivatives or tensors, which are excluded. Hence

for some real

. The Lagrange current in (

26) simply sets

without introducing canonical pairs (A4). □

4.2. Palatini Equations: Algebraic, Irrep Blocks, and Alignment

We augment the pre-lock bulk skeleton (

19) with a Lagrange current that enforces alignment of the torsion trace with

,

By Lemma 1 (

Section 2),

project-then-vary and

vary-then-project commute on scalar densities. Varying w.r.t. the independent connection then yields algebraic equations in the three irreps

:

which is block diagonal because the map from the connection variation to torsion irreps is non-degenerate:

Lemma 5 (Non-degeneracy of

)

. In metric-compatible Palatini, the linear map from to the variations of the three torsion irreps is blockwise non-degenerate. Consequently the quadratic form in (27) splits into the three irreps with independent algebraic equations.

Proof sketch (3 lines). Varying only the spin connection,

. Projecting to irreps,

and

is the traceless remainder of

after subtracting the vector/axial projections. These linear maps are surjective and mutually orthogonal with respect to

, hence the quadratic form in (

27) splits blockwise and the blocks do not interfere. □

The Euler–Lagrange equations read

and variation w.r.t.

enforces the lock

. Substituting back into (

25) fixes

and forces

, i.e., alignment with

and the absence of any axial piece, as claimed in (

22).

4.3. Positivity, Sign Choice, and the Invariant

Using the standard irrep split

and (29)–(30), we obtain

, which gives (

23) for

. Positivity of the TT kinetic coefficient after locking (

Section 5) fixes the physical branch

.

4.4. Theorem and Three-Step Proof

Theorem 6 (Palatini–

uniqueness (C1))

. Under A1–A5 and the scalar projector, algebraic torsion solving the Palatini connection equation with the trace lock (26) is uniquely with . In particular, and , and .

Proof (three steps).

Step 1 (Ansatz). The most general linear ansatz is (

24); by Prop. B.1 (Appendix B) the single-vector traceless attempt vanishes, giving (

25).

Step 2 (Palatini blocks). Using Lemma 1 to commute projection with variation and Lemma 5 for blockwise non-degeneracy, varying w.r.t.

and

yields (

28)–(30) and the lock

, which fix

and

.

Step 3 (Invariant/positivity). With

and the lock, the invariant reduces to (

23). The branch

follows from positivity of the locked TT sector. □

4.5. FRW Paper-Level Check and a Geometric Diagnostic

On flat FRW

with homogeneous

, the vector, axial and tensor blocks yield

together with the lock

. Hence

and

, in agreement with (

22)–(

23).

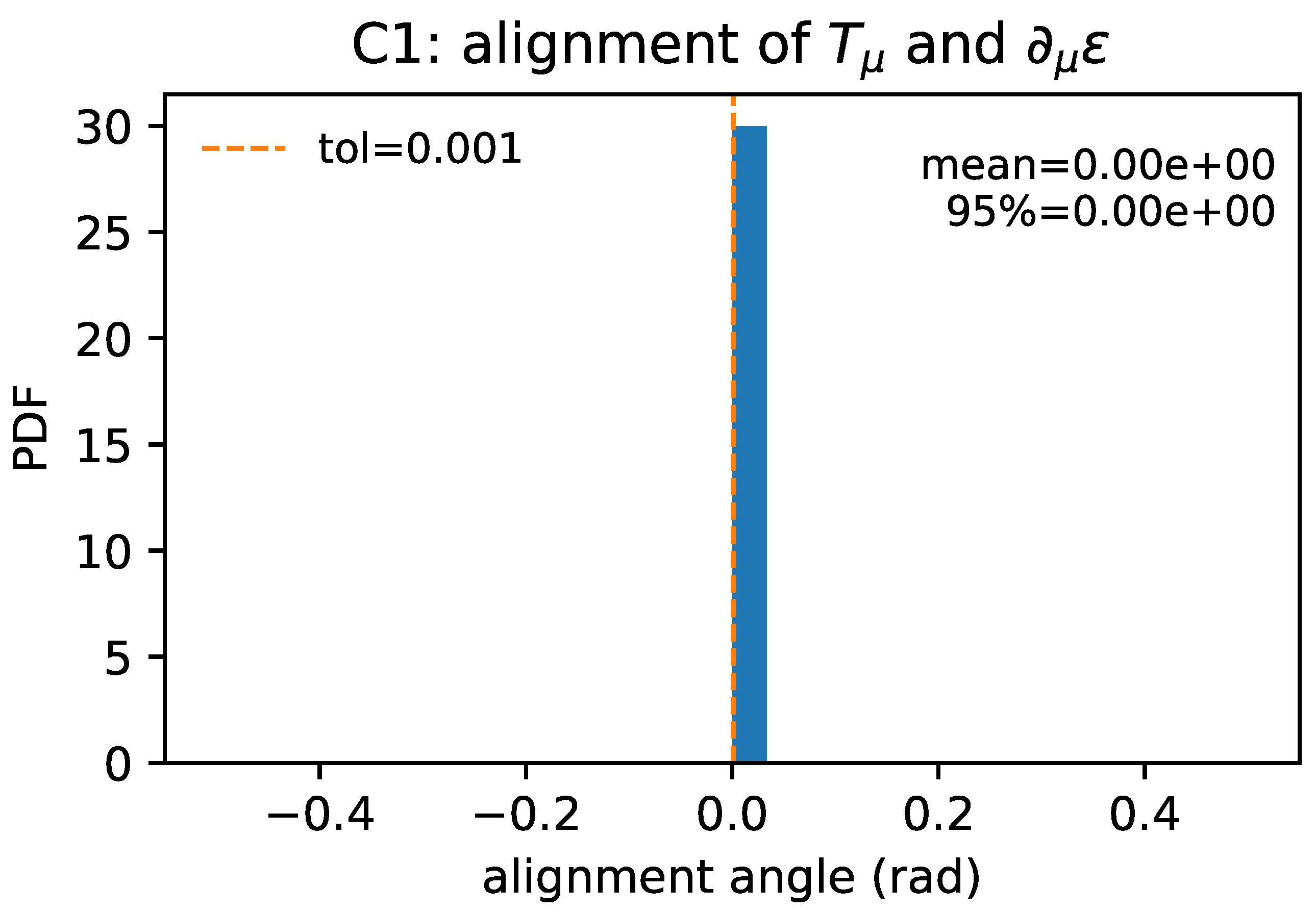

Figure 4.

Alignment-angle diagnostic. Distribution of the alignment angle

between the torsion trace

and

,

. The uniqueness map (

22) predicts

up to finite-domain/boundary remainders. [nb:

fig_c1_alignment.py].

Figure 4.

Alignment-angle diagnostic. Distribution of the alignment angle

between the torsion trace

and

,

. The uniqueness map (

22) predicts

up to finite-domain/boundary remainders. [nb:

fig_c1_alignment.py].

Corollaries, Scope, and Order-of-Operations Reminder

Corollary (basis reduction). With

and

, the first-order closure basis of

Section 3.4 collapses to

modulo a total derivative.

Scope and failure modes. Violations of A2 (orientation/) or A4 (boundary/topology) can obstruct projector selection rules or boundary improvements globally; see Appendix B for representation-theoretic caveats and Appendix A for boundary notes. None affect the main (C1) statement on admissible patches.

Order of operations. The trace lock (

26) is an algebraic constraint introduced at the level of equations of motion (or via

); it is

not a

projection and introduces no new canonical pairs. The pipeline used throughout

Section 5,

Section 6,

Section 7,

Section 8 and

Section 9 is:

5. Three-Chain Equivalence (C2)

Scope. Throughout this section, “equivalence’’ means quadratic-order bulk equality modulo improvement currents; no non-perturbative or all-order equivalence is claimed. All statements are within A1–A6 and the scalar- observable sector, and after implementing C1.

We adopt the sign-compensated (“”) scheme throughout C2: all rank-one bulk reductions are written in terms of so that patches with are handled uniformly, .

We prove that three ostensibly different quadratic routes— (i) a

rank-one determinant route built out of the canonical traceless matrix

, (ii) a closed-metric rank-one deformation, and (iii) the

-even shadow extracted from the CS/Nieh–Yan chain— collapse,

after C1 and projection, to the

same bulk invariant

up to a total derivative. Differences are carried entirely by improvement currents

(explicit FRW/weak-field representatives are listed in Appendix C).

2

5.1. Preliminaries: Canonical Rank-One Objects and Normalization

Recall

,

, and the dimensionless, traceless rank-one matrix

together with the dimension-one spurion scale (after C1),

Key relation.

5.2. Three One-Line Propositions (NY Split → ∗ & Projection → Coefficient Match)

Proposition 7 (NY split). with .

Proposition 8 (

-even shadow after ∗ and projection)

. Under A2, the combined preserves orientation and satisfies . Applying ∗ to Proposition 7 and projecting to scalars, the term contributes only as a boundary convention (A5), while the remaining -even bulk piece reduces, at quadratic order andafter C1

, to

Proposition 9 (Coefficient match under the scheme). With , , and , both (i) the rank-one determinant route and (ii) the closed-metric deformation yield the same quadratic bulk coefficient with

Proof (paper-level). Expand

; with

,

gives

. Using (

33),

. The closed-metric route has the same Jacobian

, hence the identical coefficient.

5.3. Quick Derivations (ROD/CM/CS+)

Rank-one determinant (rank-one determinant route).

Closed-metric route.

, so

-even CS/Nieh–Yan shadow. By Proposition 8,

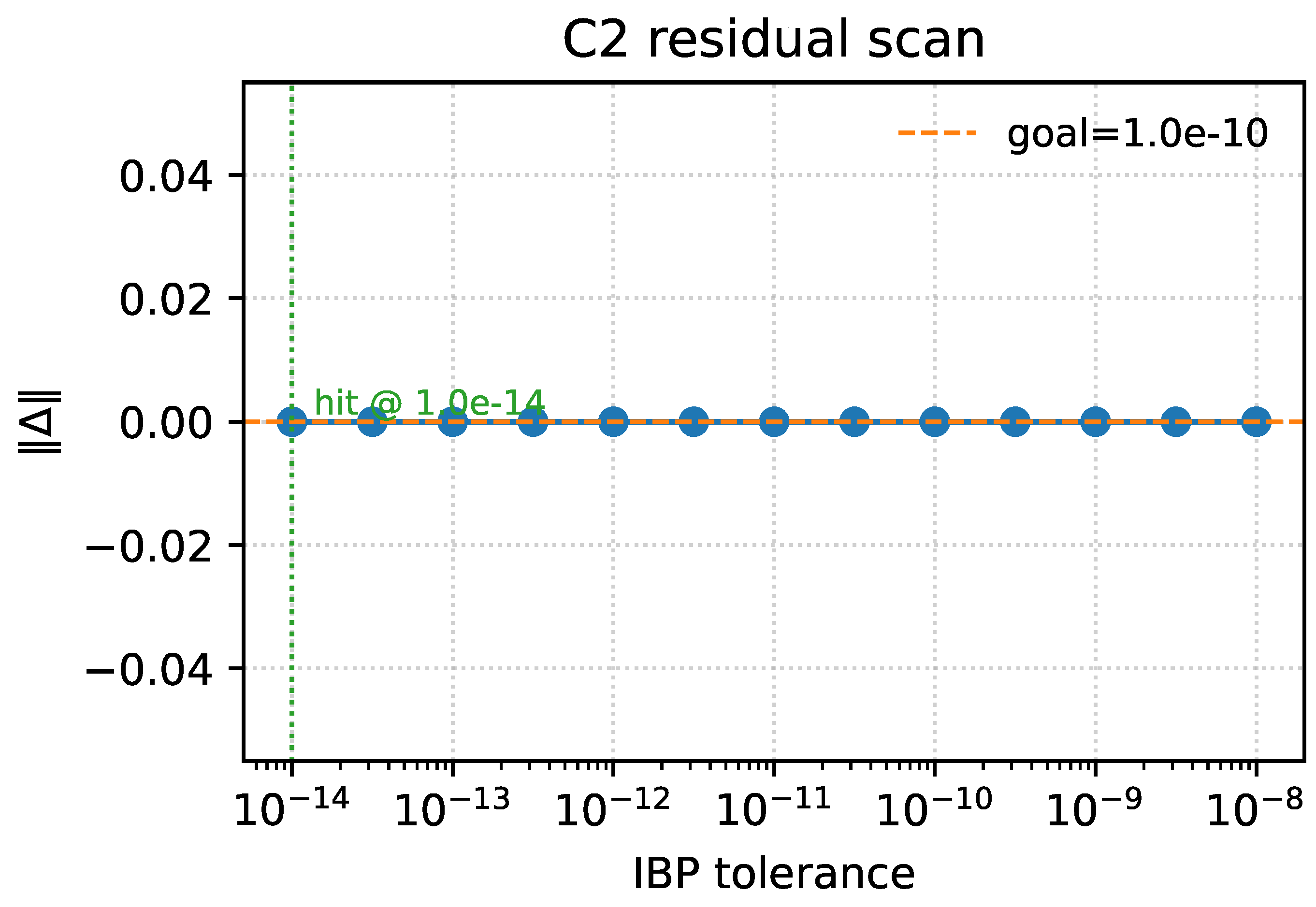

Figure 5.

Residual scan for the three-chain reduction ( scheme). Quadratic reductions of the ROD/CM/CS+ routes are compared against the target bulk line with . The vertical axis shows the residual after subtracting . All three routes saturate the target within tolerance. Quadratic-order, bulk-only (mod ; representatives listed in Appendix C). [nb: fig_c2_coeff_compare.py].

Figure 5.

Residual scan for the three-chain reduction ( scheme). Quadratic reductions of the ROD/CM/CS+ routes are compared against the target bulk line with . The vertical axis shows the residual after subtracting . All three routes saturate the target within tolerance. Quadratic-order, bulk-only (mod ; representatives listed in Appendix C). [nb: fig_c2_coeff_compare.py].

5.4. Flux-Ratio Diagnostics and Convergence

For any two routes

define improvement currents by

Assumptions A1–A5 imply

Summary of Section V. At quadratic order and under A1–A5, the rank-one determinant route, closed-metric, and

-even CS/Nieh–Yan routes share the same bulk coefficient

multiplying

, differing only by improvement currents (Appendix C). Boundary flux ratios

equal 1 within finite-domain tolerances.

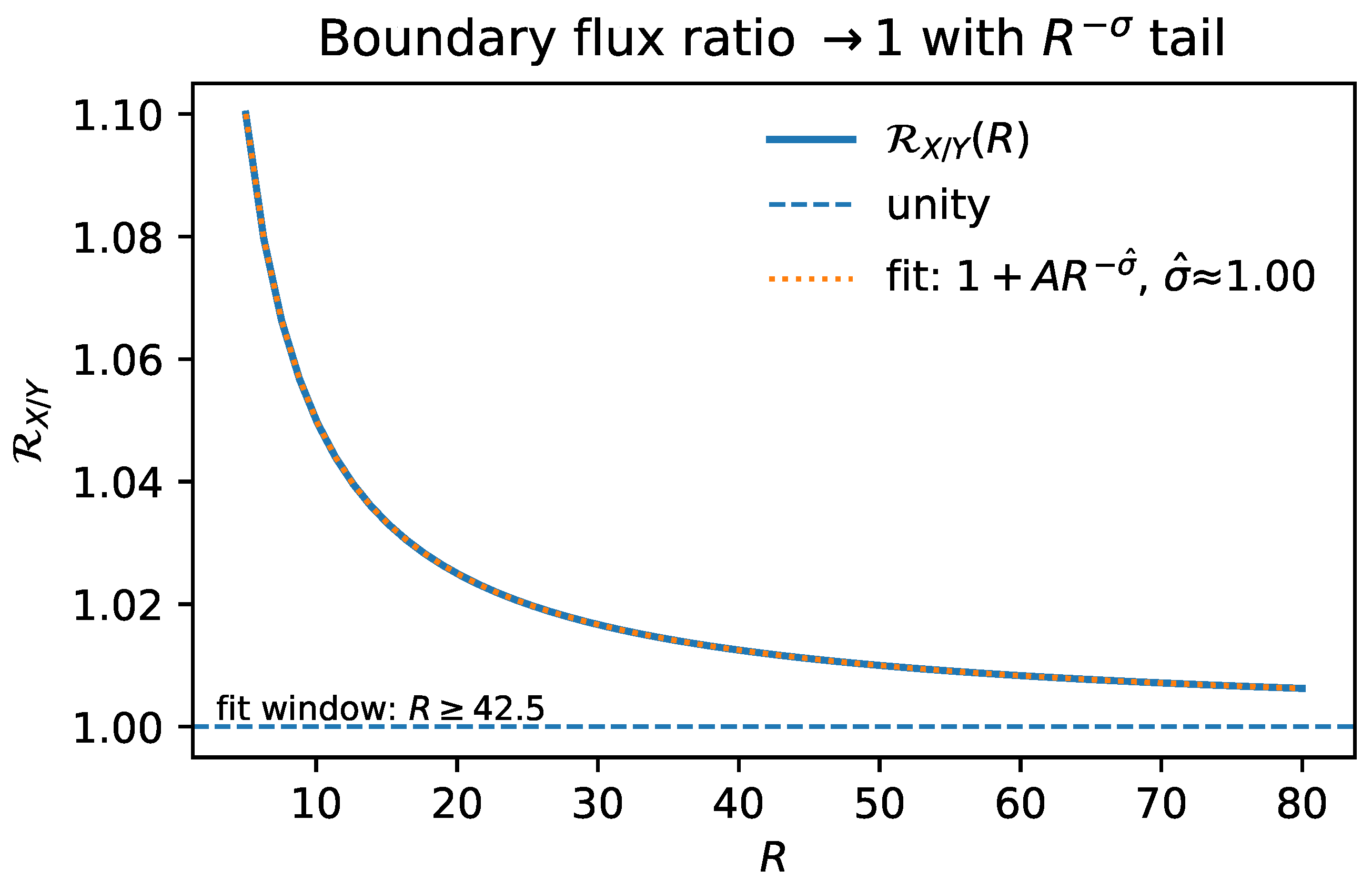

Figure 6.

Flux-ratio diagnostic. Boundary flux ratios

for representative pairs

on finite FRW balls converge to 1 as the radius

R grows, in agreement with Equation (

39). The fit window used to extract the asymptote is annotated as

. Error bars reflect the IBP tolerance propagated to boundary terms.

Quadratic-order, bulk-only (mod

; representatives listed in Appendix C). [nb:

fig_flux_ratio.py]

Figure 6.

Flux-ratio diagnostic. Boundary flux ratios

for representative pairs

on finite FRW balls converge to 1 as the radius

R grows, in agreement with Equation (

39). The fit window used to extract the asymptote is annotated as

. Error bars reflect the IBP tolerance propagated to boundary terms.

Quadratic-order, bulk-only (mod

; representatives listed in Appendix C). [nb:

fig_flux_ratio.py]

6. Coefficient Locking (C3)

We now

lock the relative weight of two bulk–equivalent routes so that the tensor (TT) sector (i) has no kinetic mixing with nonpropagating variables and (ii) is exactly luminal at quadratic order. Throughout we keep A1–A5, the scalar projector

, and the C1 pure–trace map

(

Section 2,

Section 3 and

Section 4).

6.1. Setup and Locking Posture

By

Section 5, the rank–one determinant (ROD) and closed–metric (CM) routes share the same quadratic

bulk reduction modulo a total derivative:

We therefore consider the linear family

and determine the ratio

by eliminating TT–nonTT mixing.

6.2. Quadratic ADM Block and Locking Conditions

Expanding

to second order in ADM variables,

where

collects nonpropagating fields (schematically

). The mixing block

is linear in

w and proportional to

. Two independent entries suffice to enforce

(L1) no kinetic mixing:

with real,

dimensionless coefficients

extracted from (i) the contorsion part of

under C1 and (ii) the rank–one volume variations. Explicit

’s and background dependence are tabulated in Appendix D.

We also impose (L2) exact luminality and (L3) GR normalization at so that the locked TT action reduces to GR with Planck mass .

6.3. The Locking System and Non-Collinearity

Condition (L1) yields the linear system

On generic admissible backgrounds the two row vectors are

not collinear; the determinant

so the solution space is one-dimensional.

6.4. Locked Ratio, Normalization, and Exact Luminality

With

there is a unique (up to scale) weight vector

solving (

44):

(the equality follows from

). The overall scale is fixed by (L3). For this choice, the kinetic and gradient coefficients obey the

equal–coefficient identity

with a representative

listed in Appendix D (TT gauge on weak–field and a covariant FRW form). Since the right-hand side is a total divergence on the admissible variational domain (A4), we obtain

Theorem 10 (Coefficient Locking ⇒ Exact Luminality (C3))

. Under A1–A5, the scalar projector, and C1, there exists a unique ratio (up to overall normalization) such that TT–nonTT mixing vanishes and . Consequently the TT action is exactly the GR one at quadratic order:

with no additional propagating degrees of freedom.

Proof sketch. (i) Palatini algebraicity and the rank–one structure yield the mixing form (

43); non-collinearity (

45) fixes

up to scale. (ii) For

, the difference

integrates to a boundary term (

47) by A1/A4 (self-adjoint projector; vanishing symplectic flux). (iii) The GR normalization (L3) fixes the overall scale and yields (

49).

6.5. Rank Stability and Measure–Zero Degeneracies

Near small

k and

,

so loss of rank occurs only on the measure–zero set

. This does not affect locking on generic admissible patches.

6.6. Data Companion and Reproducibility (Pointer)

For FRW backgrounds used in figures, the locked ratio

and the two independent mixing entries are extracted directly from the companion data (see

figs/data/mixing_matrix.csv with metadata in

figs/data/mixing_matrix_meta.json). A convenience configuration mirroring the analytic ratio appears in

configs/coeffs/mixing_matrix_FRW.json. These files are diagnostic only; the

paper definition of

is Equation (

46).

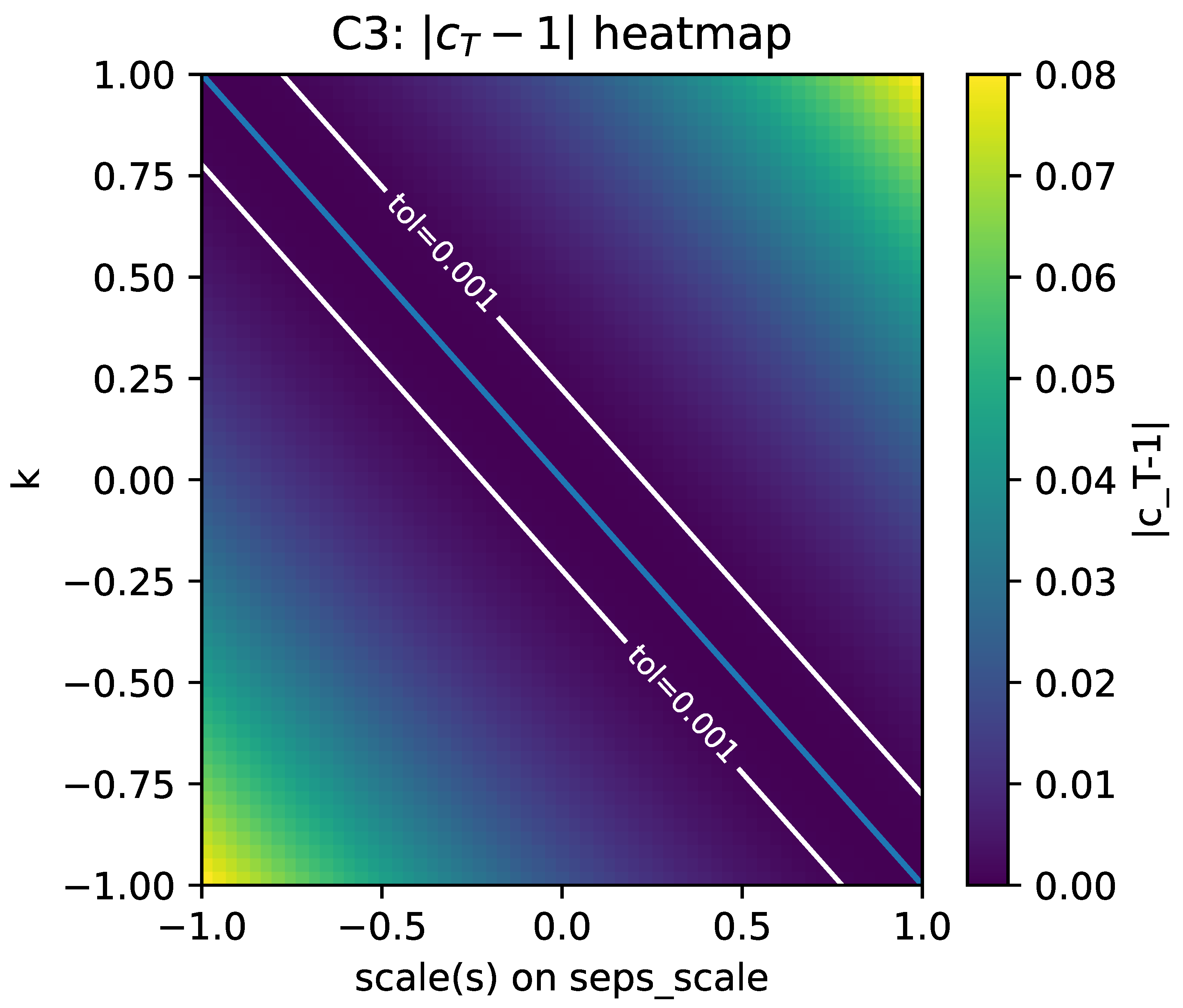

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the tensor-speed deviation. Representative scan of

over the

plane on an admissible background (A1–A5, C1 in force). The

locking curve from (

44) is overlaid; along it, TT–nonTT mixing vanishes and (

48) holds. [nb:

fig_c3_cT_heatmap.py]

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the tensor-speed deviation. Representative scan of

over the

plane on an admissible background (A1–A5, C1 in force). The

locking curve from (

44) is overlaid; along it, TT–nonTT mixing vanishes and (

48) holds. [nb:

fig_c3_cT_heatmap.py]

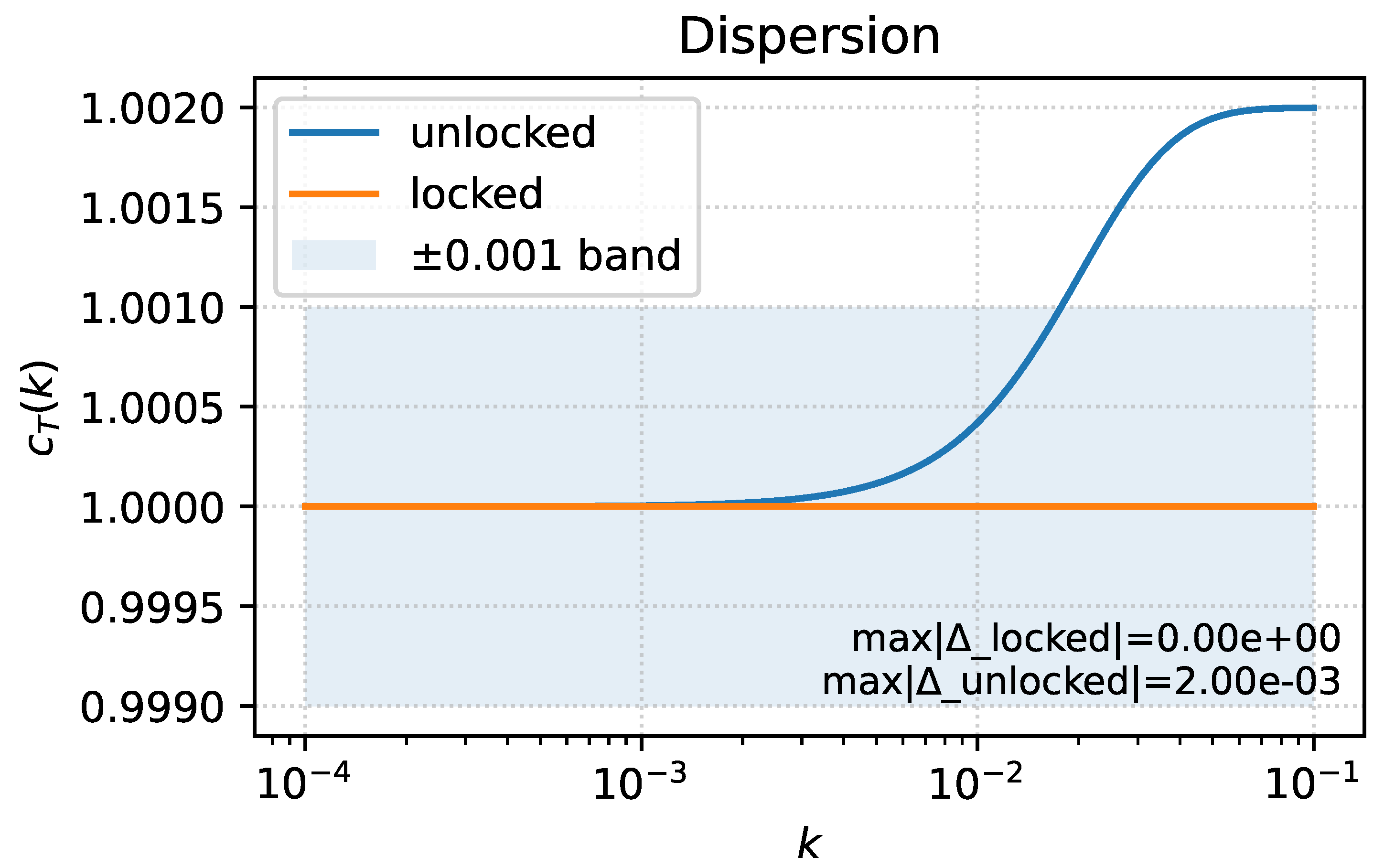

Figure 8.

Tensor dispersion : locked vs. unlocked. Comparison of

for the

locked ratio

from (

46) (solid) and representative

unlocked choices (dashed). [nb:

fig_c3_dispersion.py]

Figure 8.

Tensor dispersion : locked vs. unlocked. Comparison of

for the

locked ratio

from (

46) (solid) and representative

unlocked choices (dashed). [nb:

fig_c3_dispersion.py]

Summary of Section VI. Eliminating TT–nonTT mixing reduces to the full–rank system (

44). Its nonzero determinant fixes a

unique weight ratio

(up to normalization). With this ratio, the equal–coefficient identity (

47) gives

and hence

.

7. Quadratic Action, Exact Luminality, and Hamiltonian Constraint Structure

We now state and use the identity that fixes the tensor speed to be exactly luminal at quadratic order once the coefficients are locked, and we collect the Hamiltonian/constraint structure in one place. We assume A1–A6, the scalar projector, and the C1 map with . All projected scalars are real.

Variational domain for the

identity. We take variations with compact support on spatial slices or with FRW/AF fall-offs:

Then

and

, so total divergences do not feed back into Euler–Lagrange equations.

7.1. Equal–Coefficient Identity and

Expanding

to quadratic order (about any admissible background with A4) yields

Using the contorsion decomposition under C1, the bulk equivalence of

Section 5, and TT transversality/tracelessness, one finds the

total-divergence identity

with

a quadratic improvement current fixed by the rank–one normalization (Appendix D). Evaluated at the

locked weights

(

Section 6),

On flat FRW this reduces to

.

Weak-Field Check (Minkowski + Slowly Varying )

On

with

and a slowly varying spurion (keep

),

and

. Gauge independence holds upon integration since

.

7.2. Locked TT Action

Imposing the GR normalization (L3) and using (

53), the TT action is

7.3. Hamiltonian Analysis and Constraint Structure (Merged)

3+1 variables and boundary posture. Adopt the standard

split

. Use the admissible fall-offs of

Section 2 (A4) so that improvement currents contribute only boundary flux with vanishing symplectic pullback. Work in the time gauge for the tetrad; the configuration variables are

together with the algebraic torsion irreps packaged in

and the Lagrange current

of (

26). The spurion

is

non-variational and appears only via

.

Primary constraints and auxiliaries. N and have no time derivatives, giving . is algebraic, with primary constraints .

Lemma 11 (No new canonical pairs from

)

. Under A4 and with entering only through , the pair

is second class and removes together with the independent configuration associated to . Integrating out before the split is equivalent. No additional canonical pairs arise.

Algebraic connection equation and secondary constraints. Varying the independent connection in the projected quadratic Lagrangian (

Section 4) yields algebraic equations in the vector, axial and traceless irreps, cf. (

27)–(30). Preserving the primary constraints produces the ADM secondaries

and fixes

. Substituting back gives the C1 alignment (

22) and the invariant reduction (

23).

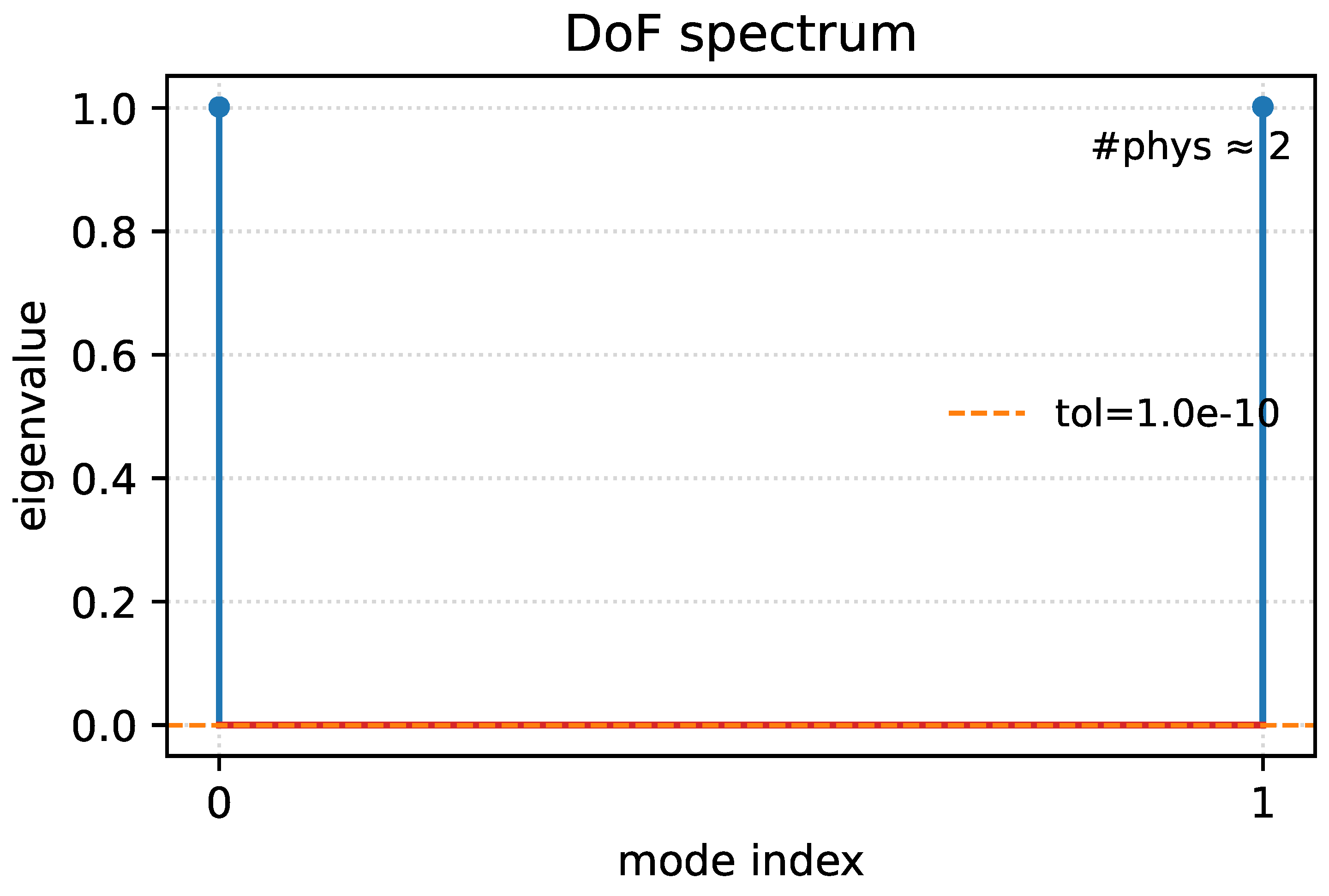

Constraint algebra and DoF count. On the admissible domain (A4), improvements do not contribute to the symplectic 2-form, and the Dirac algebra of

is the GR one at quadratic order. The torsion/lock constraints are algebraic and eliminated. Counting in the ADM-reduced metric sector:

(12),

and

(8), with eight first-class constraints

, yields

i.e., the two TT tensor polarizations.

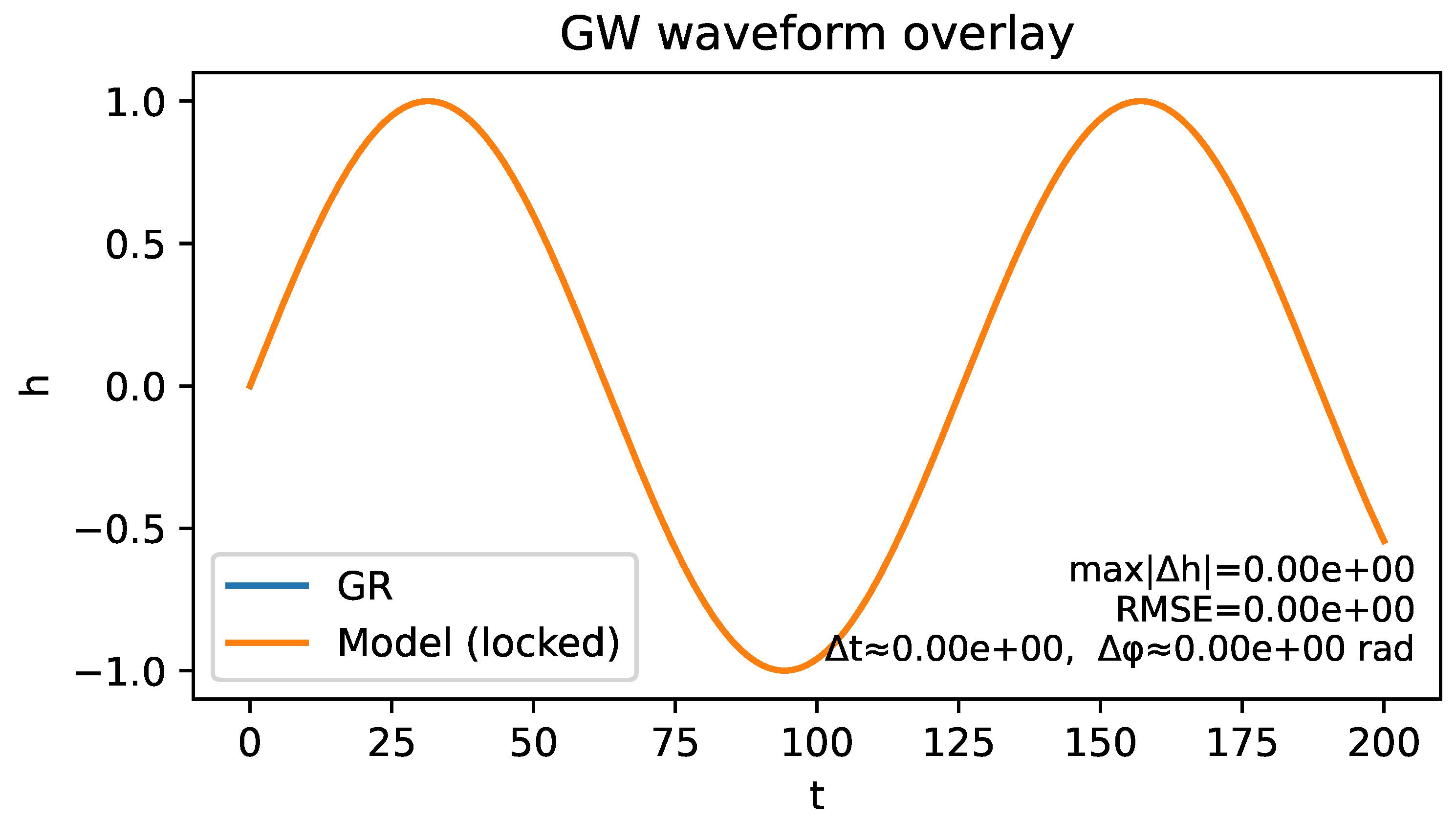

Figure 9.

GW waveform overlay (GR vs. locked). Time–domain comparison of a representative TT mode in GR (reference) and in the

locked theory (this work), evaluated on the same admissible background. The shaded band indicates the common numerical tolerance. The root–mean–square error (RMSE) and the best–fit phase offset between the two traces are annotated; both sit within the tolerance when coefficients are locked, consistent with

from Equation (

53). [nb:

fig_gw_waveform_overlay.py]

Figure 9.

GW waveform overlay (GR vs. locked). Time–domain comparison of a representative TT mode in GR (reference) and in the

locked theory (this work), evaluated on the same admissible background. The shaded band indicates the common numerical tolerance. The root–mean–square error (RMSE) and the best–fit phase offset between the two traces are annotated; both sit within the tolerance when coefficients are locked, consistent with

from Equation (

53). [nb:

fig_gw_waveform_overlay.py]

Boundary/improvement terms and the symplectic form. With the fall-offs of

Section 2, the symplectic potential picks only exact variations from improvements. Their integral is an

-weighted boundary term that vanishes for compact support or FRW/AF fall-offs. Thus neither the route-dependent improvements of

Section 5 nor the divergence realizing

affects the canonical structure or DoF count.

Takeaway of the Merged Section

Primary ADM constraints remain first class, the algebraic connection equation removes axial and traceless torsion while the Lagrange current locks to without creating new canonical pairs, and the coefficient locking leaves a positive, exactly luminal TT sector. The theory propagates precisely two tensor degrees of freedom.

Figure 10.

DoF spectrum (eigenvalue stem plot). Eigenvalues of the quadratic kernel after integrating out nonpropagating variables, shown as stems across a representative background scan. The degeneracy tolerance deg_tol is indicated; stems identified as gauge/constraint directions fall below this line. The count of eigenvalues above deg_tol tracks across the scan, confirming the absence of extra propagating modes at quadratic order. [nb: fig_c3_degeneracy.py]

Figure 10.

DoF spectrum (eigenvalue stem plot). Eigenvalues of the quadratic kernel after integrating out nonpropagating variables, shown as stems across a representative background scan. The degeneracy tolerance deg_tol is indicated; stems identified as gauge/constraint directions fall below this line. The count of eigenvalues above deg_tol tracks across the scan, confirming the absence of extra propagating modes at quadratic order. [nb: fig_c3_degeneracy.py]

8. Coupling to Dirac Matter

We record how minimally coupled Dirac matter interacts with the Palatini–

posture under A1–A5 and the uniqueness map (C1). Throughout, projected scalars are real (

Section 2), and torsion is purely trace and aligned with the spurion gradient,

as established in Theorem 6. Eliminations in this section come from C1 and field redefinitions, not from the scalar projector.

Two-line summary.

- (i)

No axial channel: C1 forces , so the axial coupling is absent at tree level. - (ii)

Trace channel is removable: with , the linear vector coupling is removed by a vector phase redefinition and reduces to a boundary improvement under A4/A5.

|

8.1. Setup and Conventions

Consider a Dirac spinor minimally coupled to Riemann–Cartan geometry,

with

,

, and metric-compatible

. Splitting

, the torsion irreps

couple to

and

via

with real

fixed by conventions (Appendix E). Improvements do not affect bulk Euler–Lagrange equations under A4.

8.2. Axial Channel: null by C1

Theorem 6 gives and . Hence .

8.3. Trace Channel: Removal by a Local Vector Rephasing

With , . Perform , which shifts . Choosing cancels the trace channel. Up to a divergence, , and on the Dirac EOM, so the difference is an improvement fixed by .

Parity remark and measure. The projector does not remove (it is -even); its elimination uses C1 and a vector rephasing. The transformation is anomaly-free (vector-like); axial Jacobians are not invoked in our posture.

With . If carries charge q, the rephasing is equivalent to , leaving invariant.

NLO Tensor Dispersion and a Band-Limited Estimate

NLO operator and estimate. At the next order in the “one-derivative-per-building-block” posture, the leading

-even correction in the TT block is

Taking the multimessenger bound

in the LIGO/Virgo band and using

gives

. At

(

),

and the bound strengthens by

at

. Thus current ground-based bands only weakly constrain

-type dispersion; lower-frequency probes (e.g., PTA) can improve this if

.

Summary of Section VIII. Under the Palatini– posture and C1, the axial channel vanishes and the trace channel is removable by a local, anomaly-free vector rephasing, up to a boundary improvement controlled by A4/A5. In addition, the leading -even NLO operator yields ; a simple LIGO/Virgo estimate places band-limited lower bounds on .

9. Next-to-Leading Order and Data-facing Remarks

We organize the leading,

-even corrections beyond the quadratic, one-derivative-per-building-block closure and state their data-facing implication for tensor propagation. Throughout, the global posture A1–A5 and the locked TT sector (

Section 6 and

Section 7) are understood.

Treating ϵ as non-dynamical is the low-energy limit of a Stueckelberg completion in which freezes ; complementary EFT constructions reduce to the same gradient-only dependence at this order (

Appendix G). This EFT origin justifies the spurion posture used below.

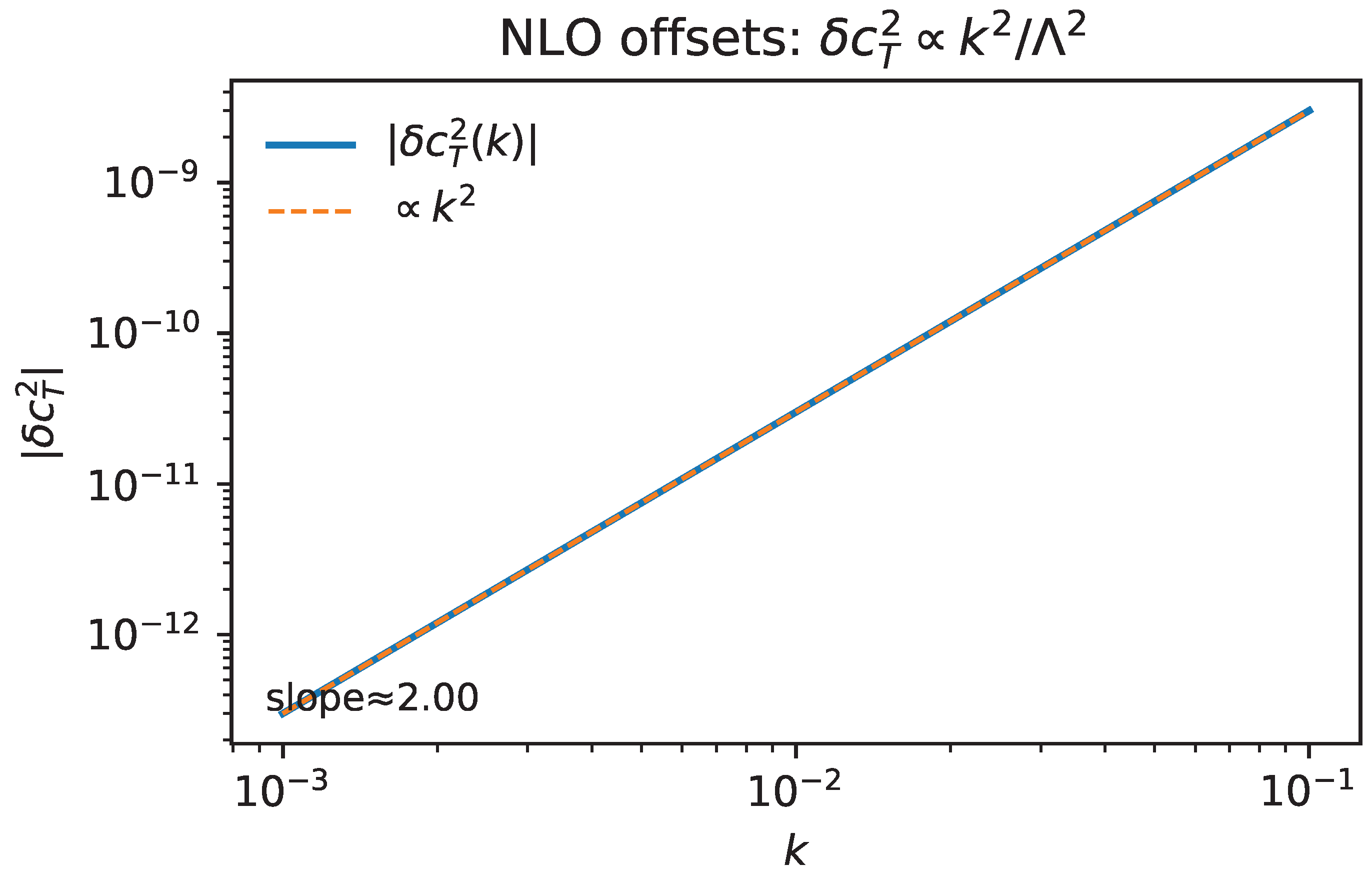

9.1. Minimal NLO Operator and Dispersion

At next-to-leading order (NLO) the unique, parity-even contribution that

affects the TT dispersion at quadratic order is a four-derivative tensor operator.

3 A convenient parameterization is

with a real, dimensionless coefficient

b and a heavy scale

. For a Fourier mode with physical wavenumber

(today

), the quadratic equation of motion gives

so that the leading deviation is quadratic in frequency.

Figure 11.

NLO offsets and slope fit. Measured tensor-speed offset

from the locked LO value

as a function of physical wavenumber

k (log–log axes). The best-fit slope

is annotated; the vertical offset fixes

in Equation (

63) (a band is shown if multiple backgrounds are included). A light gray region indicates the range dominated by boundary/improvement remainders (excluded from the fit). [nb:

fig_nlo_offsets.py]

Figure 11.

NLO offsets and slope fit. Measured tensor-speed offset

from the locked LO value

as a function of physical wavenumber

k (log–log axes). The best-fit slope

is annotated; the vertical offset fixes

in Equation (

63) (a band is shown if multiple backgrounds are included). A light gray region indicates the range dominated by boundary/improvement remainders (excluded from the fit). [nb:

fig_nlo_offsets.py]

9.2. Dimensional Check and Normalization of b

which is manifestly dimensionless. Our normalization of the rank-one tensor

and of

(

Section 5) singles out

unless additional heavy operators are tuned to cancel each other at this order.

|

Remark (NLO estimate at GW band). With and a representative multimessenger tolerance near , Assuming , this gives a lower bound At the bound scales linearly with f, (). These are order-of-magnitude, band-limited constraints; tighter bounds require a fit to detector bandpasses and b-modeling. |

9.3. EFT Validity and Conservative Use of Bounds

Equation (

62) is an

EFT statement valid for

In this regime higher-order terms are negligible and the approximation is self-consistent. When interpreting band-limited constraints, we therefore adopt the conservative rule: only frequencies well below the inferred should be used to quote limits on .

9.4. What to Report (Band-Limited, Paper-Level Recipe)

Given a measurement (or bound) on

in a finite band centered at

, report

This is the only NLO,

-even, projector-compatible modification of the locked TT sector at quadratic order that survives as a bulk effect. All other admissible NLO pieces either (i) reshuffle into improvements under A4/A5, or (ii) renormalize

K and

G equally and thus do not shift

at this order.

9.5. Falsifiability Beyond the Spurion Limit

If

retains residual dynamics beyond the strict spurion posture (

Appendix G), leading TT deviations can be parameterized, at the quadratic level and within our

-even closure, as

where the first term is the universal NLO prediction of Equation (

61) and the second encodes spurion-residual effects (vanishing in the strict spurion limit or when

is a nondynamical spectator at two derivatives). The ellipsis denotes higher-derivative terms suppressed by additional powers of

or by boundary/improvement conventions under A4/A5.

A complementary null diagnostic exploits the three-route structure of

Section 5,

Section 6 and

Section 7. Define the (dimensionless) route-difference observable

with

the bulk coefficient on the invariant line (

Appendix C). In the strict spurion limit and under A4/A5 one has

(up to improvement choices that cancel in flux ratios). Any statistically significant

, or any robust departure from the quadratic

k-scaling in Equation (

63) across clean frequency windows,

falsifies the spurion posture at this order.

4

Band-level implementation (pointer to Appendix F).

Appendix F adds two data-facing checks: D9-a (quadratic scaling of

) and D9-b (route equality via

and flux ratios). Passing both tests supports the spurion posture; failing either constitutes evidence for residual spurion dynamics or for physics beyond our two-derivative closure.

Summary of Section IX. At NLO the locked,

-even Palatini posture predicts a single, band-limited correction to tensor propagation,

, with

under our normalization of

. The EFT is valid for

. Deviations from the spurion limit are captured by Equation (

66) and can be

falsified by (i) the

slope test and (ii) the route-difference diagnostic

(

Appendix F, D9).

10. Supplement R: Reproducibility (Lean, Repository-Backed)

All code, figure generators, configs, and tests are open-sourced at:

This supplement gives a

minimal, repository-backed map to rebuild the paper figures and to validate C1/C2/C3. We avoid code dumps; the repo already pins the environment (

environment.yml), packaging (

pyproject.toml), and task runners (Makefile, Snakefile).

Terminology vs. filenames. The paper uses the term ROD for the rank-one determinant route. Repository filenames keep the legacy token dbi (e.g., configs/coeffs/dbi.json); they refer to the same route.

R.0 Layout (Pointer)

Top-level directories used by this paper: scripts/ (figure generators), configs/ (grids & coefficient JSON), palatini_pt/ (library), tests/ (pytest), figs/ (outputs and checksum sidecars), and notebooks/ (script mirrors). A one-shot driver scripts/make_all_figs.py rebuilds all paper figures.

R.2 Rebuild & Validate (Three Lines)

Environment (conda/mamba). conda env create -f environment.yml; conda activate palpt

Rebuild all figures. python scripts/make_all_figs.py (writes PDFs to figs/pdf/)

Validate claims (C1/C2/C3 & diagnostics). pytest -q (covers tests/test_c1_torsion.py, test_c2_equivalence.py, test_c3_tensor.py, test_flux_ratio.py, test_nlo.py, ...)

R.3 Checksums (Sidecars)

Every PDF and data artifact ships a .md5 sidecar (e.g., figs/pdf/fig1c1puretrace.pdf.md5, figs/data/c2residuals.csv.md5). Verification: md5sum -c figs/pdf/*.md5; md5sum -c figs/data/*.md5. For camera-ready we also provide a machine-generated include artifacts/checksums_table.tex; if present, the paper auto-includes it.

R.4 Version Pin

We cite the exact Git revision used to build the artifacts and tag the release. The repository ships figs.tar.gz and notebooks.tar.gz snapshots matching committed artifacts. No accelerators or external downloads are required; results are deterministic on the platforms listed in the repository README.md.

Summary. Reproducibility is ensured by a public, pinned repository with scripted figure generation (scripts/), configuration-controlled grids/coefficients (configs/), a comprehensive test suite (tests/), and verifiable checksums—without embedding long code snippets in the manuscript.

11. Related Work

This section positions our scalar- projected Palatini posture within (i) the historical torsion/metric–affine line (EC/MAG), (ii) Palatini-type modified gravity and its known pitfalls, and (iii) the post-GW170817 observational landscape—including torsionful GW studies. We close with short operational notes so that the paper-level claims (C1–C3) can be checked independently of our proofs and figures. Throughout, we keep boundary/improvement conventions explicit (A4–A5) and restrict statements to the posture defined by A1–A6.

11.1. Historical & Geometric Context (EC/MAG; metric–affine)

The decomposition of torsion into trace/axial/traceless irreps and the independent treatment of

are standard in the Einstein–Cartan/metric–affine (EC/MAG) tradition; see the canonical reviews for geometry and phenomenology of torsion and non-metricity [

6,

8]. Our use of the Holst density and its relation to the Nieh–Yan 4-form follows the usual parity bookkeeping, with Nieh–Yan exact on admissible patches [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Boundary/improvement issues are treated within covariant phase-space/charge frameworks [

14,

15].

Against this backdrop, we project observables to scalar, -even densities and enforce projective invariance via a Stueckelberg compensator that appears only through . Within our two-derivative posture this yields: (C1) algebraic elimination of axial and traceless torsion irreps at quadratic order; (C2) bulk-level collapse of three constructive routes modulo improvements; and (C3) a coefficient-locking identity that guarantees exact luminal tensor propagation without parameter tuning.

11.2. Palatini-Type Modified Gravity & Known Pitfalls

Palatini-type modifications—foremost Palatini

—have a rich history but also well-documented tensions once matter is included: equivalence to constrained scalar–tensor forms, tight post-Newtonian bounds, and (in stellar contexts) surface pathologies or curvature singularities [

19,

20,

21]. These issues motivate a symmetry-selected, data-facing sector where observables are specified before variation and boundary terms are accounted for explicitly.

Observable projection. A scalar- projector removes -odd pseudoscalars and discards non-observable mixtures before variation, preventing contamination by parity-odd densities in the tensor sector.

Projective invariance with a spurion limit. Only the invariant trace combination is allowed to enter observables; axial and traceless torsion are algebraically removed at quadratic order (C1), thus avoiding extra propagating modes.

Boundary accounting. Improvement currents and Nieh–Yan are confined to boundary conventions (A4–A5), under which the bulk quadratic actions of three constructive routes share the same coefficient (C2). This sets the stage for the equal-coefficient identity and the exact luminal result (C3) without tuning.

For contrast, Chern–Simons modified gravity retains metric variables but introduces a dynamical pseudo-scalar and parity-odd effects [

25,

26]; our tensor-speed statement instead lives in a parity-even, projected scalar sector with controlled improvements.

11.3. Post-GW170817 Tensor-Speed Constraints & Torsionful GWs

The multimessenger observation GW170817/GRB170817A constrained the present-day tensor speed to be extremely close to luminal, catalyzing a reappraisal of modified gravity in which any

is strongly disfavored [

27,

32]. While much of that discourse focused on Horndeski/EFT parametrizations, torsionful lines have also been examined: within Poincaré gauge gravity and Einstein–Cartan frameworks, tensor waves are often luminal while amplitudes/attenuation laws or polarization content can differ [

38,

39].

Our positioning. We provide a

clean, even-parity route to exact luminality at quadratic order via (C3), not by parameter tuning but by a structural identity linked to projective invariance and improvements. Beyond quadratic order, our posture predicts a unique next-to-leading deviation,

expressly designed for multi-band tests (PTA/LISA/LVK) using log-slope diagnostics (Section 9). This offers a falsifiable bridge between symmetry/geometry and data: if a

-type dispersion is not seen where EFT is valid, our posture is disfavored; conversely, a consistent

slope constrains

.

11.4. Operational Notes and Disambiguation (kept short)

We keep the diagnostics compact and checkable, without rederiving results:

Scope. All quadratic bulk equalities (C2) and the identity underlying (C3) are asserted within A1–A6 (notably A4–A5). Topological torsion defects or boundary conditions that inject new canonical pairs fall outside our posture.

C1 (pure-trace alignment). Within the scalar- projected sector, axial and traceless torsion vanish algebraically at quadratic order; only the trace aligned with remains. Any robust axial-torsion signal in observables would falsify C1.

C2 (three-route bulk equivalence). Rank-one determinant (DBI-like), closed-metric, and the -even projected CS/Nieh–Yan route share the same bulk coefficient and differ only by improvements; the flux ratio diagnostic on admissible domains implements this check in practice.

C3 (equal-coefficient locking). A non-collinear mixing system fixes and yields , whence at quadratic order, with the EFT-consistent NLO dispersion quoted above.

Navigation. Table 2 summarizes how our scalar-

Palatini posture differs from canonical lines, while

Table 3 records the operational status of A1–A6. Claims (C1–C3) are proven in the main text under these assumptions; observational guidance and reporting conventions for the NLO dispersion appear in Section 9.

Funding

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the anonymous referees for comments that improved the manuscript. Limited use of generative language tools was made for stylistic refinement; all scientific reasoning, derivations, and conclusions remain solely the responsibility of the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Code availability

Same as Data availability.

Appendix A. Projection–Variation Commutation (A3) and Variational Identities

This appendix establishes Assumption A3 in full generality for scalar densities and compiles the variational identities for

,

, and the Hodge star ∗ under the Palatini posture with the scalar

projector of

Section 2. We also make explicit the boundary/topology posture (A4) used when trading improvements for boundary fluxes, and we record the

selection rules used throughout the paper.

Appendix A.1. Setup and Conventions

We work with independent vierbein

and a metric-compatible spin connection

(Palatini posture). The observable

scalar densities are mapped to a real,

-even sector by the projector

with the combined

acting anti-linearly (complex conjugation accompanies

T) and preserving the chosen orientation (A2), so that

on forms. The internal phase

is a

spurion: it enters observables only via

and is

not varied. All statements below are thus variations with respect to

while keeping

fixed.

Appendix A.2. Projector Properties: Idempotence, Self-Adjointness, and Selection Rules

Proposition 12 (Self-adjointness of

on real scalars)

. Under A1 (domain/measure -invariance) one has, for any scalar densities ,

Proof. Expand the left-hand side using Equation (

A1) and the fact that

:

Using A1,

, the cross terms rearrange into

. □

Proposition 13 (Selection rules for the scalar projector)

. With A1–A2 and metric compatibility, for any admissible tensors X:

Proof (sign count). Under A2 the chosen orientation is preserved and

;

is

-odd, hence any pseudo-scalar density built from it flips sign and is annihilated by

. The spurion gradient

picks opposite

parities relative to

(table in

Section 2.3), so

is

-odd and is projected out. Quadratic contractions

and

are

-even and the projector returns their real parts, hence (

A2). □

Appendix A.3. Commutation of Projection with Variation (A3)

Theorem 14 (Projection–variation commutation (A3)

. Let be any local scalar density built from . Then, for variations with respect to at fixed ϵ,

Proof. By definition,

It suffices to show

. The

action on fields is an involutive automorphism on the local functional algebra, and it is anti-linear only through global complex conjugation (time reversal). For any complex functional

F one has

because the variation acts linearly on fields and does not act on the numerical

i. Therefore, with

denoting collectively the fields that are varied and

their

image,

where we used that

does not touch the spurion (fixed) and commutes with derivatives and index operations under A2. Substituting back and using linearity of the “real” operation yields Equation (

A6). □

Remarks. (i) Anti-linearity from

T introduces only complex conjugation, which commutes with variational derivatives as shown. (ii) The assumption that

is not varied (spurion posture) is essential; if one promotes

to a dynamical field, additional boundary terms appear but Equation (

A6) continues to hold for the

scalar projector provided the same posture (A1–A2) is kept for the extended field space.

Appendix A.4. Variational Identities for , and the Hodge Star

Metric and vierbein. With

,

Determinant and Levi–Civita tensor.

These follow from

and

, with

the (constant) Levi–Civita

symbol.

Hodge star. Let

be a

p-form and

. Then the variation of ∗ with respect to

h is

In particular, for 2-forms

F (frequent in the Palatini curvature/torsion algebra),

. Because the metric is

-even and the chosen orientation is preserved (A2), the Hodge map built from

commutes with

:

This identity is used both in the selection rules and in the projector proofs that involve

p-form duals.

Appendix A.5. Boundary/Topology Posture and Improvement Currents

Assumption A4 is realized in either of the following equivalent ways:

- (i)

Compact, -invariant domains with vanishing boundary flux: for any improvement current arising from integration by parts, .

- (ii)

Standard fall-offs on asymptotically flat or spatially flat FRW patches, for which

reduces to a surface integral that vanishes in the

limit. A sufficient set is

which ensures

so that the flux through a sphere of radius

R decays as

.

These conditions justify replacing improvement terms by boundary conventions and are precisely what is used in the flux-ratio diagnostics of

Section 5.4.

Appendix A.6. Consequences Used in the Main Text

(C1) Palatini block-diagonalization. Theorem 14 (A3) allows us to

project then vary in the Palatini equations, so that the connection variation is algebraic and block-diagonal in the torsion irreps. Together with the selection rules (Proposition 13) this yields

and the pure-trace map quoted in

Section 4.

(C2) Route equivalence modulo boundary. Self-adjointness (Proposition 12) and the boundary posture (Section A.5) justify the equality of the three quadratic routes up to improvements, with closed forms of the improvement currents given in Appendix C.

(C3) Equal-coefficient identity and

. The star-variation identities (

A9)–(

A10) are used inside the ADM expansion behind the equal-coefficient identity

proven in Appendix D. The boundary posture then enforces

and

at quadratic order.

This completes the formal proof of A3 and the supporting calculus advertised in

Section 2.

Appendix B. Irrep Projectors & No-go for qλμν (v)

This appendix collects the group-theoretic ingredients used in

Section 4: (i) the irreducible decomposition of the torsion tensor under the Lorentz group, (ii) explicit, idempotent projectors onto the trace, axial, and traceless sectors, (iii) the quadratic identity for

in our conventions, and (iv) the

single-vector no-go that underlies the statement quoted in the main text as “Proposition B.1” for the

irrep. All statements are purely algebraic and hold before/after applying the scalar projector

; after projection all scalar contractions are real (

Section 2).

Appendix B.1. Torsion as a Lorentz Representation and Its Algebra

In index language (spacetime indices), torsion is a rank-3 tensor antisymmetric in its last two indices,

, with

independent components in

. The Lorentz-covariant irreducible content splits into

We use

and the metric signature

, and we adopt the standard scalar product

on this space.

5

Appendix B.2. Idempotent Projectors

Define three linear maps

on the torsion space by

These are the unique Lorentz-covariant, algebraic (derivative-free) projectors onto the three irreps in Equation (

A13). A direct computation shows:

and the images obey by construction

Orthogonality and quadratic split. With the scalar product

,

Using (

A14)–(A16) one finds the standard quadratic identity

where we have denoted

for the

standard normalization of the traceless piece.

Normalization used in the main text. For later convenience—and to match the coefficient choice used in

Section 4—we rescale the traceless irrep by a constant factor and

define

The projector formulas (

A14)–(A16) are unchanged; only the bookkeeping name “

q” for the traceless image carries the fixed

factor.

6 After applying

to either side of (

A21), the scalar is manifestly real (Thm. 2).

Appendix B.3. Compatibility with the Scalar Projector

The projectors

are algebraic and commute with

at the scalar level: for any two torsions

,

Moreover, the mixed scalar

is

-odd and is annihilated by

(

Section 2.4). Thus the orthogonal split (

A19) remains valid as an identity between

projected, real scalars.

Appendix B.4. Proposition B.1: Single-Vector No-Go for the Traceless Irrep

Proposition 15 (single-vector no-go). Let be any nonzero covector. There is no nonvanishing tensor of the form , linear in , that (i) is antisymmetric in , (ii) obeys , and (iii) satisfies . Equivalently, the traceless irrep cannot be constructed from a single vector.

Proof. The most general Lorentz-covariant tensor built linearly from a single

and antisymmetric in its last two indices is a linear combination of the two rank-one seeds

with real

. Compute its traces and axial contraction:

where we used

and

. Requiring the trace constraints

forces

, and the axial constraint forces

. Therefore the only admissible linear combination is the trivial one,

, proving the claim. □

Corollary 16. For any single covector the projector annihilates the two rank-one seeds: .

Appendix B.5. Consequences for the C1 Ansatz

Applying Proposition 15 to the most general

linear ansatz with one derivative (

Section 4.1),

shows that the attempted traceless piece

necessarily vanishes: it is a linear, single-vector construct and is thus killed by

(Cor. 16). The ansatz collapses to

recovering Equation (4. 2) of the main text. The scalar projector

removes

-odd

scalars built from the axial seed (

Section 2.4), and the Palatini connection equation then sets

while fixing

under the trace lock

(

Section 4.2). This yields the uniqueness map

quoted in Theorem 6.

Appendix B.6. Consistency Check with the Quadratic Invariant

With the normalization (

A21) and the C1 map (so

and

),

as used throughout

Section 4 and

Section 5. Here

is the

projected, real scalar, and the sign bookkeeping is carried by

; the unit 1-form

, the canonical traceless rank-one matrix

, and the trace scale

are recalled from

Section 3.

Appendix B.7. Edge Cases and Patches

On loci where

the normalized direction

is defined patchwise (or by continuity); all algebraic projector statements remain valid, and the conclusions above hold on any patch with

. Global/topological subtleties (multi-valued

, nontrivial bundles) lie outside the posture A1–A5 (

Section 2).

Summary of Appendix B. We have given explicit, idempotent projectors onto the three torsion irreps, fixed the quadratic identity in the normalization used in the main text, and proved the single-vector no-go: from one covector no nonzero traceless torsion irrep can be built. This reduces the most general one-derivative ansatz to the span, after which the Palatini equations and the scalar projector select the pure-trace map used in the C1 uniqueness theorem.

Appendix C. Appendix C: Three–Chain Reductions & Improvement Currents (σ ϵ scheme)

Scope ( scheme and naming). This appendix provides the paper–checkable reductions behind

Section 5 under the

sign-compensated convention

and the rank-one determinant route naming (formerly “DBI”-type; not Born–Infeld gravity): (i) a rank-one determinant route built out of the canonical traceless matrix

, (ii) a closed–metric rank–one deformation, and (iii) the

–even CS/Nieh–Yan shadow. At quadratic order,

each route reduces in the bulk to the same invariant line

with improvements

differing by boundary choices (A4/A5). Closed representatives for

are given on FRW/weak–field backgrounds.

Notation and key relation. We use the preamble shorthands

so that

and (after C1)

Appendix C.1. rank-one determinant route: Determinant Algebra with the 2 3 Normalization

Consider the rank-one determinant route Lagrangian

Using

and

, the quadratic piece is

With

and

,

so that

At the bulk-density level one may take . For unified boundary diagnostics we adopt a common canonical representative for all three routes (Section C.4).

Appendix C.2. Closed–Metric Route: Rank–One Deformation Equals rank-one determinant route to

Take the rank–one deformation

so that

and define

. The same algebra gives

Thus rank-one determinant route and CM have the

same bulk coefficient

and differ only by improvements.

Appendix C.3. PT–Even CS/Nieh–Yan Shadow: Quadratic Reduction (σϵ)

Using

, applying ∗ and the scalar

projector (A2), and evaluating after C1, the

–even piece reduces at quadratic order to

where the Nieh–Yan assignment (A5) reshuffles only boundary conventions inside the

–even sector.

Appendix C.4. A Universal Canonical Improvement at Quadratic Order

For route–by–route flux comparisons it is convenient to select the

same improvement representative for all routes:

so that we

adopt the convention

Different representatives differ by

and yield identical integrated fluxes under A4.

Check (FRW). On spatially flat FRW in TT gauge,

i.e., the canonical reshuffling between TT kinetic/gradient bilinears plus a pure time boundary term that integrates to zero with A4 fall–offs.

Appendix C.5. Closed Forms for FRW and Weak Field

FRW. For

and homogeneous

,

which satisfies (

A37).

Weak field (AF). At

,

Appendix C.6. Flux–Ratio Identity & Finite–Domain Convergence

With the unified choice (

A36),

, hence

On finite FRW balls (or AF shells) residuals scale away with the radius

R, agreeing with Section V.

Summary of Appendix C

At quadratic order and under A1–A5 plus C1, the rank-one determinant route, closed–metric, and

–even CS/Nieh–Yan routes share the same bulk reduction

. A single canonical improvement

(Equations (

A35)–(

A37)) is used for all routes and underlies the flux–ratio plots in Section V.

Appendix D. Appendix D: Mixing Matrix and the Equal–Coefficient Identity

This appendix contains (i) extraction rules and tables for the

mixing matrix used in

Section 6, including a

non-collinearity proof of its two row vectors on admissible backgrounds, and (ii) a covariant derivation of the

equal–coefficient identity quoted in

Section 7. We assume A1–A5, the scalar

projector (

Section 2), and the C1 map

. Projected scalars are real by construction; the

scheme only affects the bulk line through

, not the kinematical identity

.

Variational domain (used below). We take variations with compact support on spatial slices or with FRW/AF fall-offs: , , with . Then and .

Appendix D.1. ADM Conventions and Extraction of Mixing Entries

With

,

,

(

), and

, we project

with

. The quadratic Lagrangian takes the block form

where

collects nonpropagating pieces. Define the

dimensionless mixing entries by

For

, the mixing block is linear in

w and proportional to

:

defining the four dimensionless coefficients

.

Appendix D.2. Background Invariants and Compact Parametrization

Introduce

(prime is conformal-time derivative). Each

admits a linear decomposition

with

c’s real

numbers fixed by the quadratic expansion rules (route Jacobians plus contorsion under C1).

Appendix D.3. Coefficient Tables (FRW and Weak Field)

Table A1.

FRW coefficients with

. Entries are the dimensionless

’s of (

A44), written as

[Equation (

A46)]. Overall factor

multiplies the mixing (

not shown here).

Table A1.

FRW coefficients with

. Entries are the dimensionless

’s of (

A44), written as

[Equation (

A46)]. Overall factor

multiplies the mixing (

not shown here).

| Coefficient |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A2.

Weak field (AF) coefficients with slowly varying . Set () and define . Overall factor multiplies the mixing (not shown here).

Table A2.

Weak field (AF) coefficients with slowly varying . Set () and define . Overall factor multiplies the mixing (not shown here).

| Coefficient |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Closed-form labels (for Section VI cross-references). For later citation we record the compact forms as Equations (D.12)–(D.15):

Appendix D.4. Non-Collinearity of the Two Locking Equations

Let the two rows be , .

Proposition 17 (Non-collinearity)

. Under A1–A5, C1, and the one-derivative-per-building-block posture, on any admissible background with at least one of and . Equivalently,

Proof (sketch). Using (

A46), proportionality would require

to be route–independent and constant under independent shifts of

and

. But

and

cannot both vanish for

unless

(static trivial branch

,

). Hence

generically. □

Small-

k structure (symbolic). On weak-field patches one finds

so rank loss occurs only on the measure-zero set

or special foliations.

Appendix D.5. Equal–Coefficient Identity: Covariant Derivation and Gauge Shift

Define the quadratic current (indices contracted with the background spatial metric)

with

and

. Using TT conditions, the rank–one traceless normalization, and the bulk equality of the routes (Section V),

Under

,

, the representative shifts as

, hence the

integrated identity is gauge independent.

FRW and weak-field representatives. On spatially flat FRW (

, homogeneous

),

so

is a total divergence. In weak field (AF,

),

Boundary consequence and luminality. With the variational domain above (A4), . At the locked weights (Section VI; no TT–nonTT mixing), at quadratic order, slicing–independently.

Appendix D.6. Locked Weights and Summary Box

Non-collinearity with the two mixing equations yields a unique ratio (up to the GR normalization). At these weights, implies exact luminality.

Appendix D (at a glance).

Mixing matrix. Four dimensionless coefficients (; ) control the TT–constraint mixing with an overall factor.

Non-collinearity. The two locking rows are not proportional on evolving admissible backgrounds; the determinant is generically nonzero ().

Equal–coefficient identity.; under A4 this yields and at the locked weights .

|