Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Quantify changes in plant species diversity by assessing variations in richness, composition, and diversity indices along the gradient;

- Evaluate stand structural attributes, including tree density, basal area, canopy cover, and diameter-class distribution; and

- Analyze natural regeneration through measurements of seedling and sapling densities of S. robusta and associated species.

2. Materials and Methods

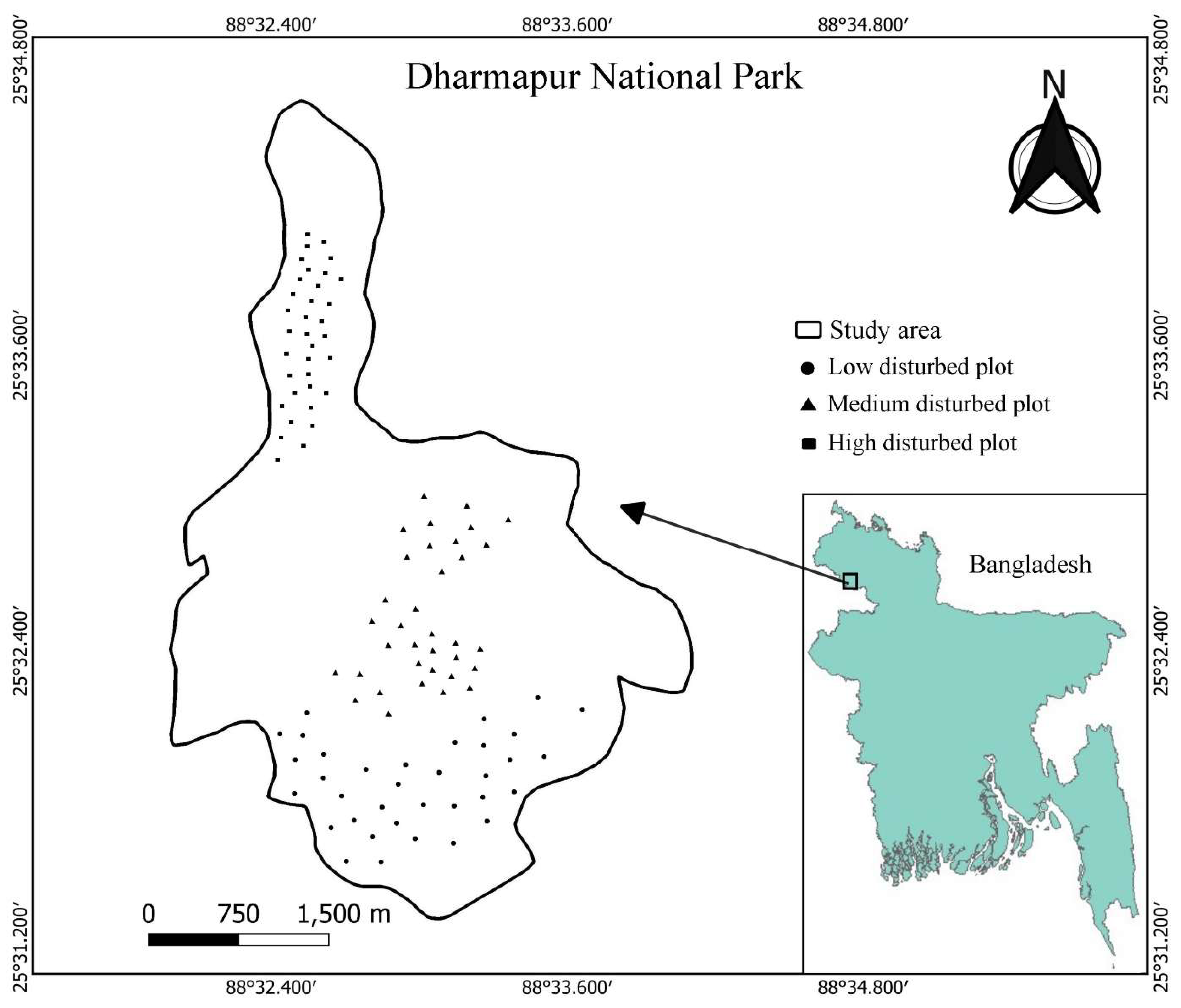

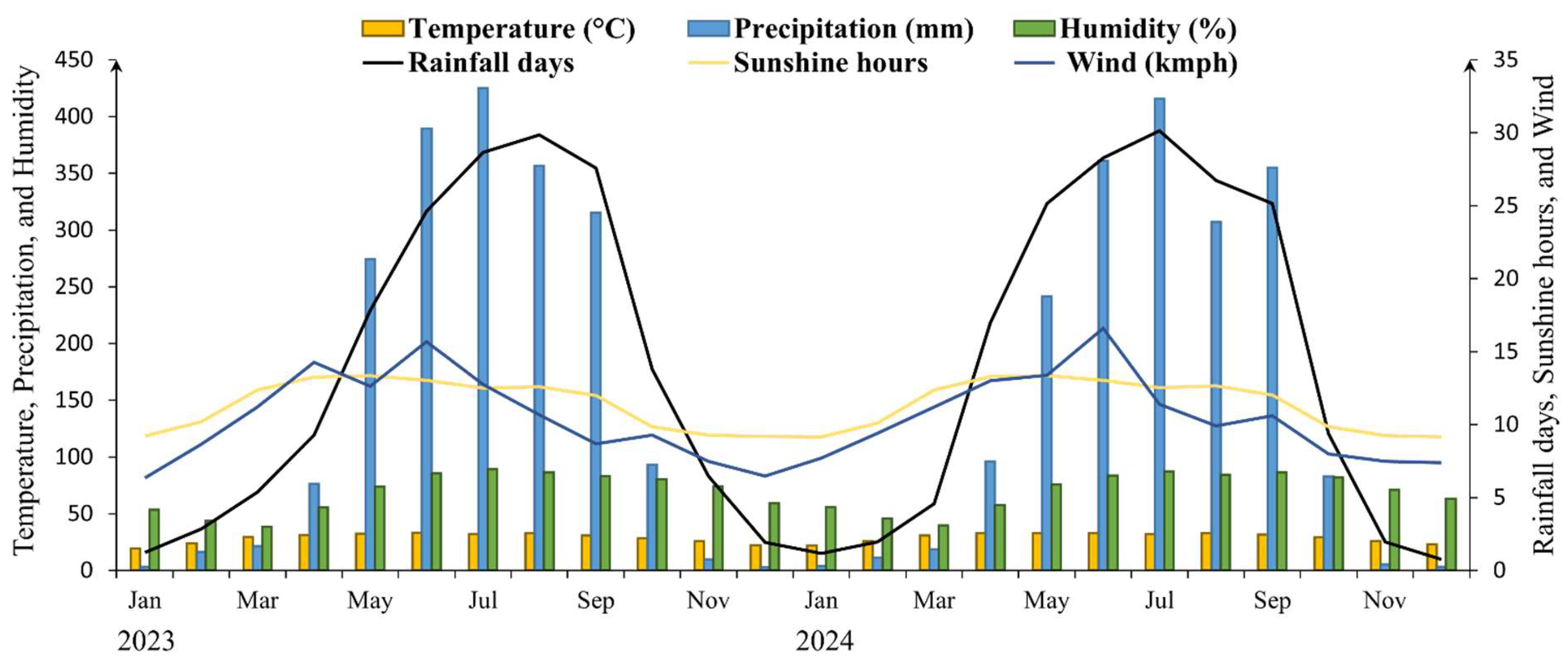

2.1. Study Area

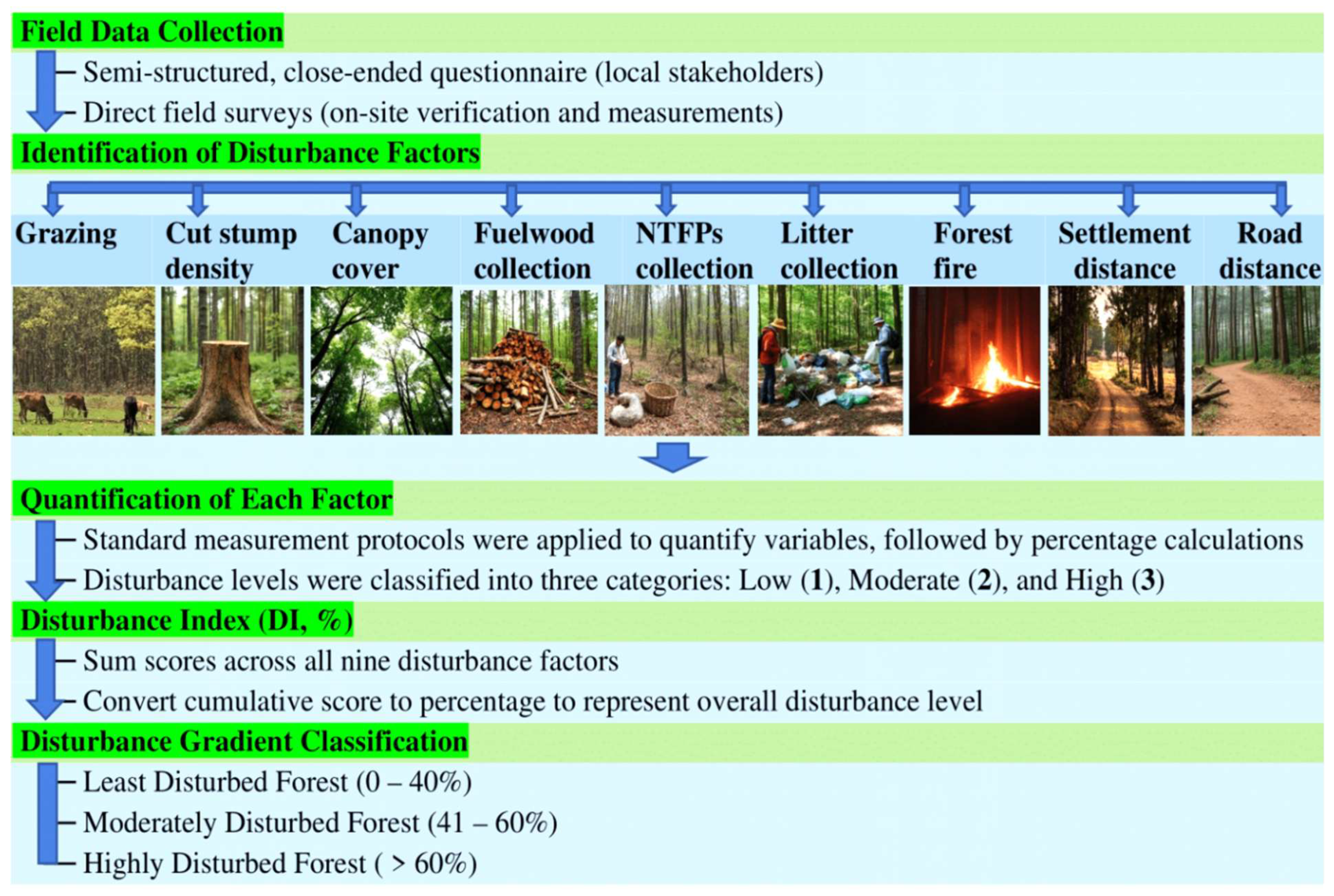

2.2. Disturbance Gradient Classification

| Grazing intensity (%) | = | Biomass of forage consumed | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total biomass of available forage | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cut stumps (%) | = | Basal area of cut stumps | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total BA (cut stump + standing) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tree canopy cover openness (%) | = | Area not covered by canopy | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total plot area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fuelwood collection (%) | = | Biomass of fuelwood removed | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total biomass (fuelwood + standing) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NTFPs collection (%) | = | NTFPs disturbance area | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total study area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Litter collection (%) | = | Weight of collected litter | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total weight of litter in the area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Forest fire (%) | = | Area of burred | × 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Settlement distance (%) | = | 1 - | Distance from the settlement | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Max distance – Min distance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Road distance (%) | = | 1 - | Distance from the road | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Max distance – Min distance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disturbance Index (%) | = | Cumulative score of disturbance factors of a plot | × 100 |

| Maximum disturbance score of a plot |

2.3. Sampling Design

2.4. Vegetation Data Collection

| Density (%) | = | Number of individuals of a species in all quadrats | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total number of quadrats | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Basal area (m2) | = | π | DBH 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency (%) | = | Number of quadrats in which the species occurs | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total number of quadrats | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Relative frequency (RF%) | = | Number of occurrences of a species | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Number of occurrences of all the species | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Relative density (RD%) | = | Number of individuals of a species | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Number of individuals of all the species | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Relative basal area (RBA%) | = | Basal area of a species | × 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total basal area of all species | ||||||||||||||||||||

2.5. Diversity Indices

2.6. Natural Regeneration Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Disturbance Index and Contributing Factors

3.2. Species Richness and Composition

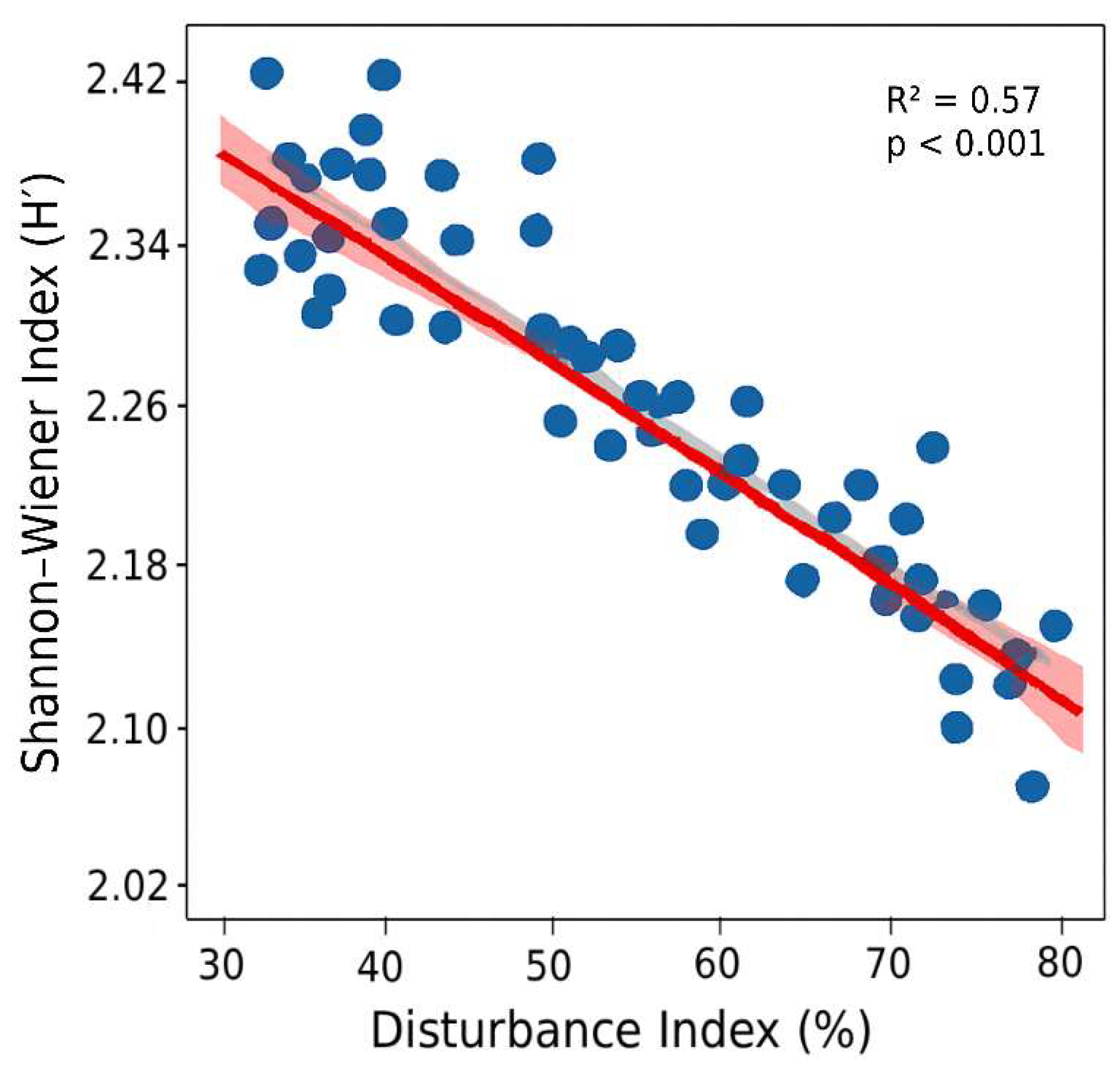

3.3. Diversity Indices

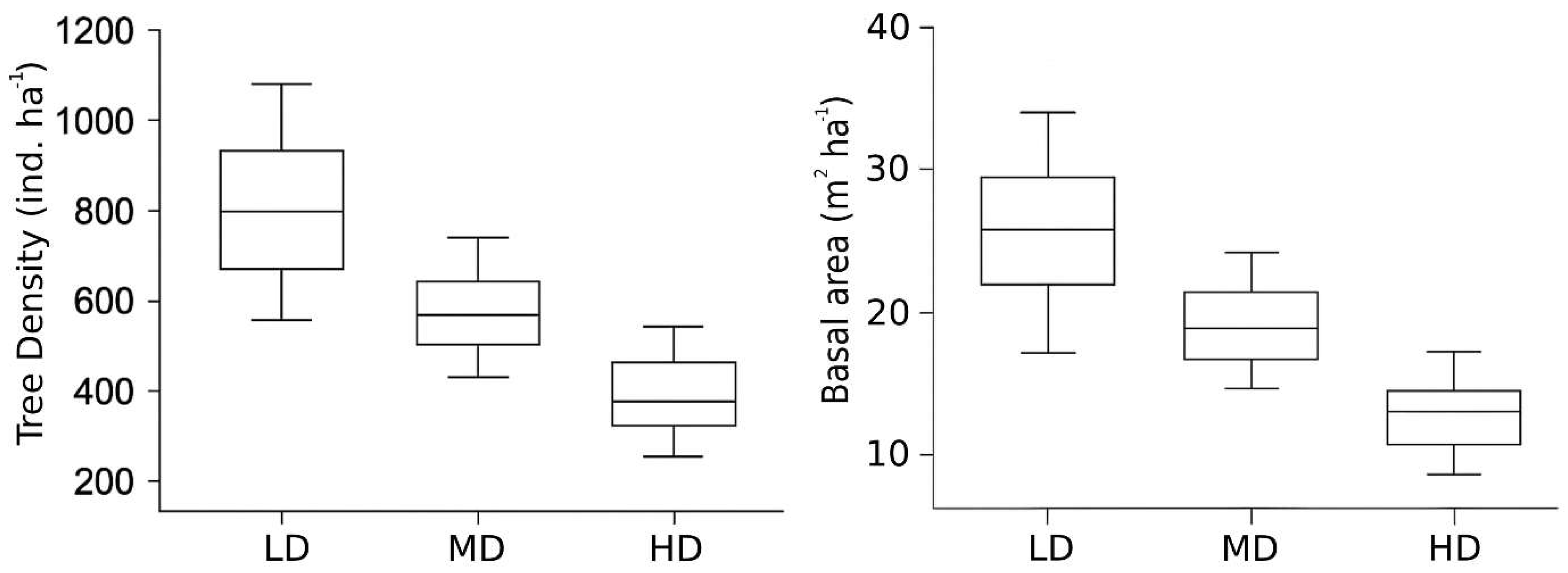

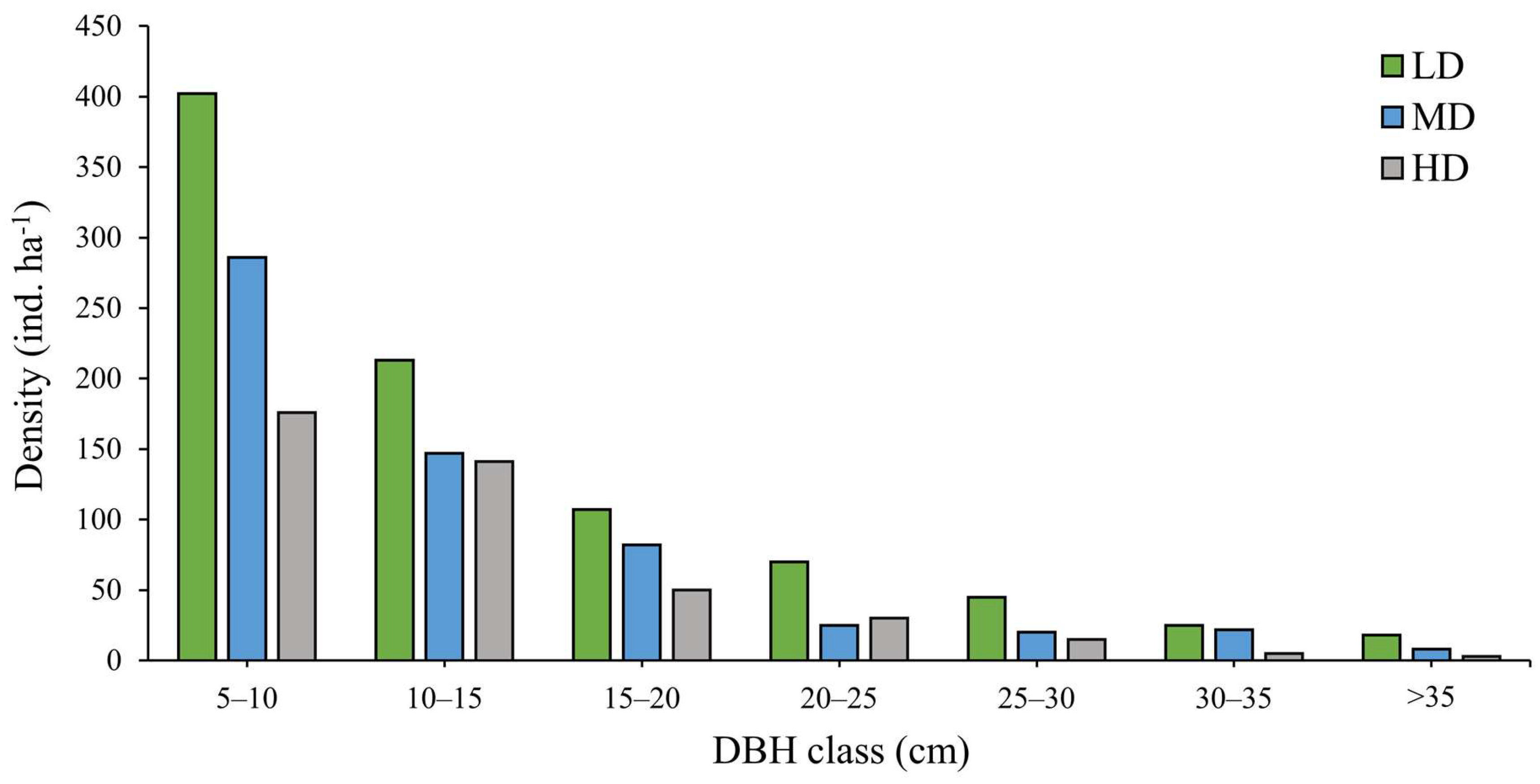

3.4. Stand Structure

3.5. Relationships Between Disturbance Index and Forest Attributes

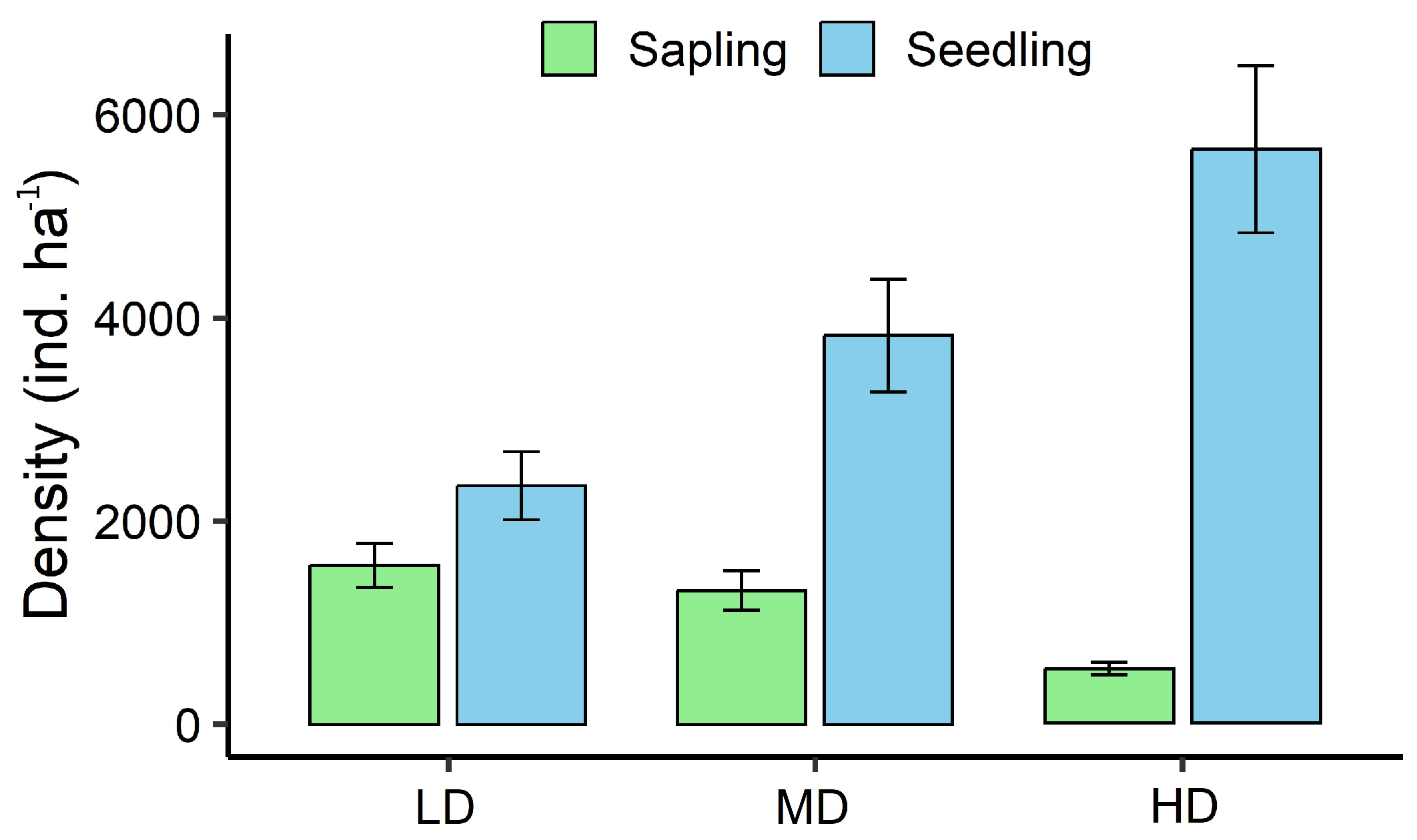

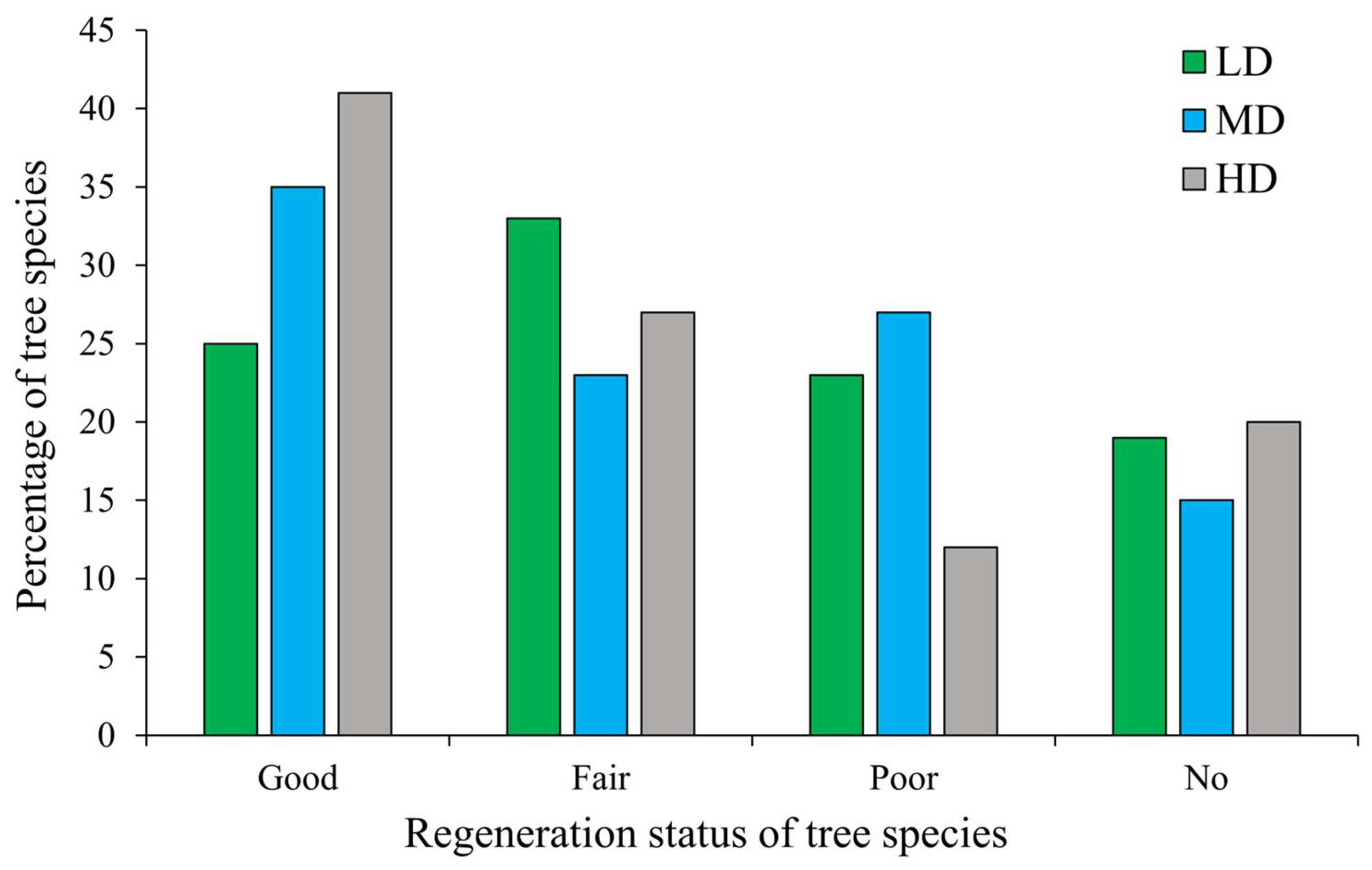

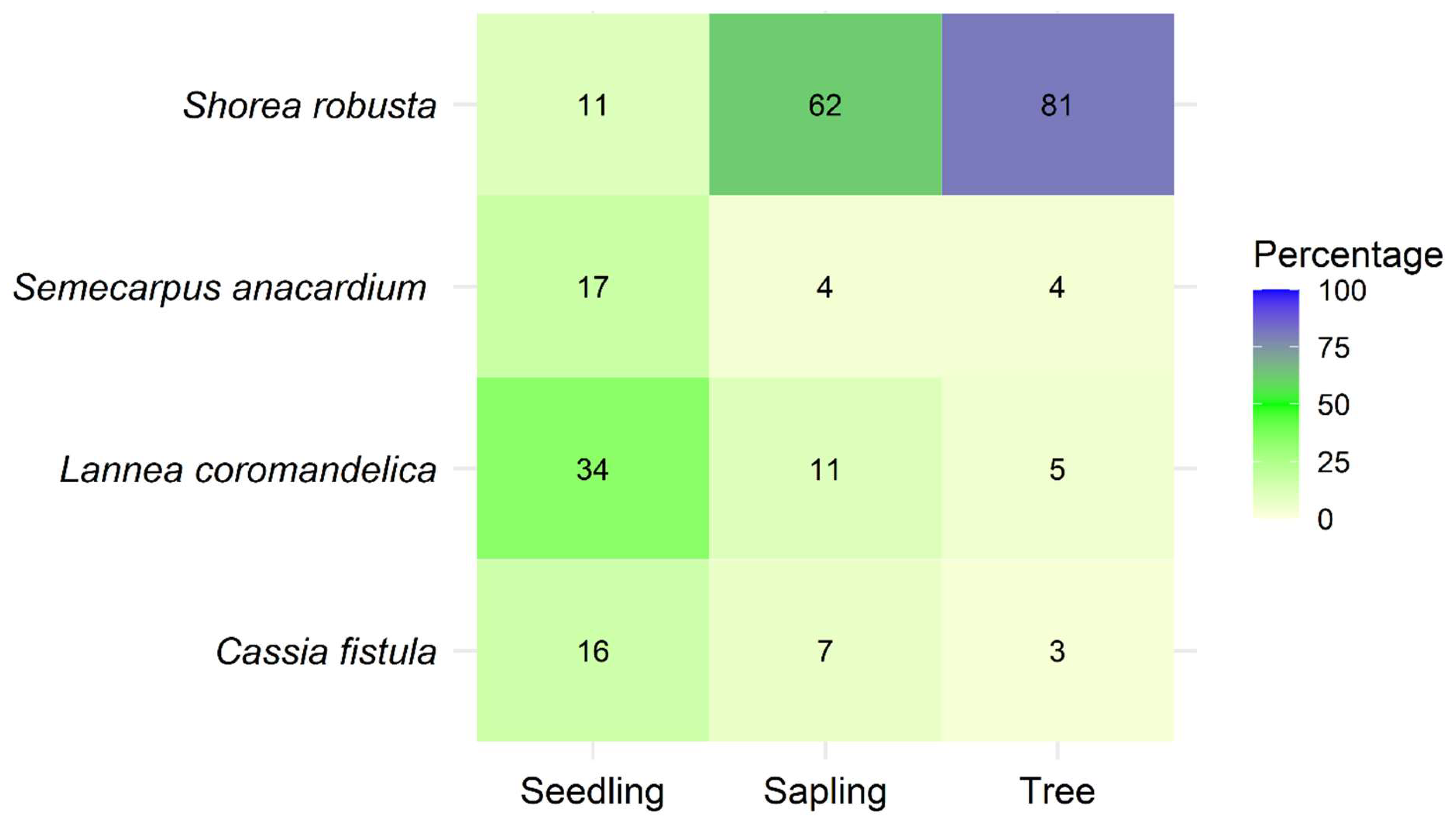

3.6. Regeneration

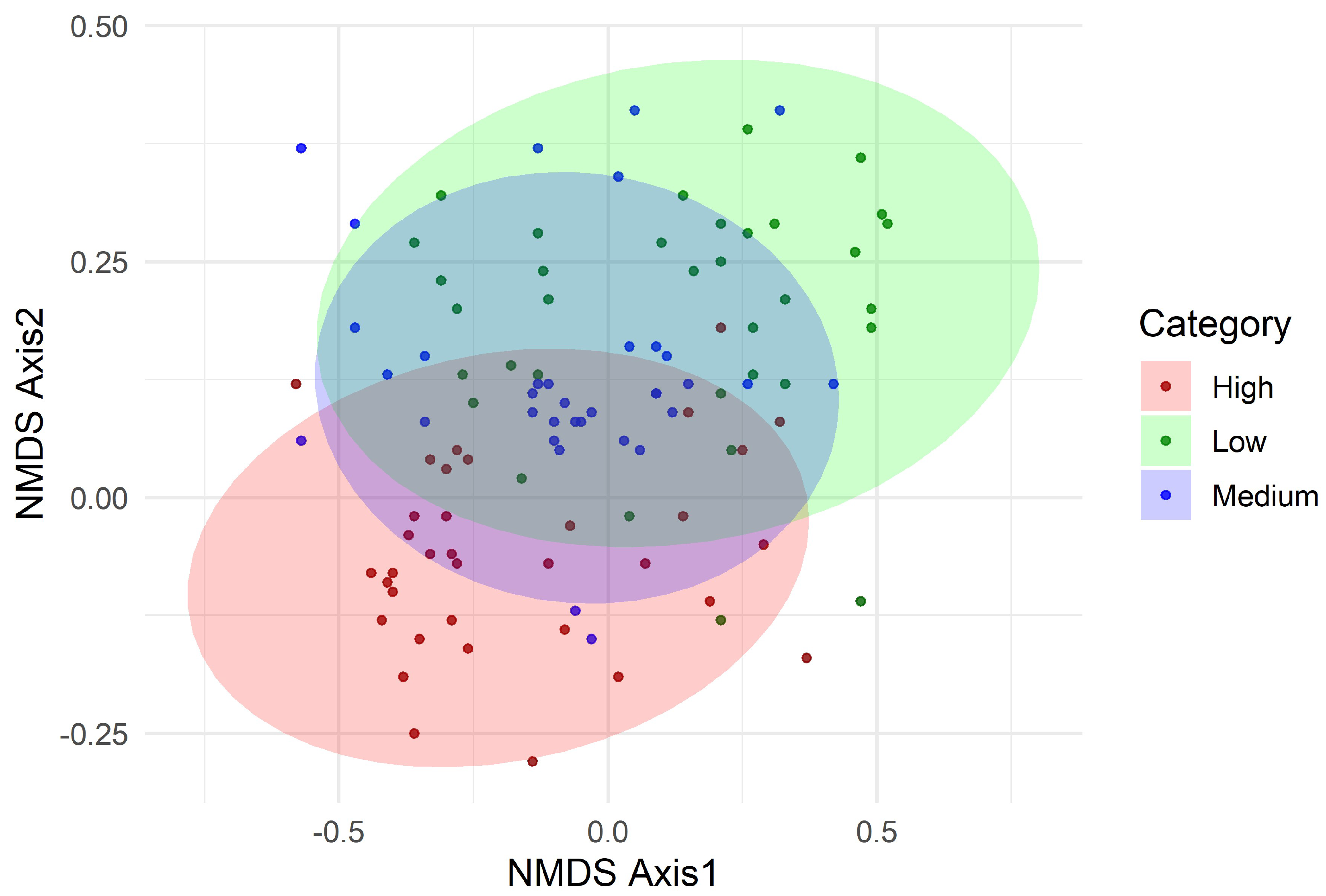

3.7. Community Similarity and Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Stand Structure and Forest Dynamics

4.2. Regeneration Dynamics

4.3. Community Composition and Beta Diversity

4.4. Regional and Management Implications

5. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Du, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhou, J.; Ciais, P.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Liu, R.; Lin, G.; Fan, L. Recent advances and challenges in monitoring and modeling of disturbances in tropical moist forests. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1332728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Seidl, R.; Grünig, M.; Bauhus, J.; Willig, J.; Hlásny, T.; Nabuurs, G.-J.; Patacca, M.; Peltoniemi, M.; Espelta, J.M.; et al. Managing Forest Disturbances in a Changing Climate; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolila, N.J.; Shirima, D.D.; Mauya, E.W. Tree species composition along environmental and disturbance gradients in tropical sub-montane forests, Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.A.M.; Lindeskog, M.; Smith, B.; Poulter, B.; Arneth, A.; Haverd, V.; Calle, L. Role of forest regrowth in global carbon sink dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4382–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.L.; Lambin, E.F.; Reenberg, A. The emergence of land change science for global environmental change and sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20666–20671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazdon, R.L. Second Growth: The Promise of Tropical Forest Regeneration in an Age of Deforestation; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs: High diversity of trees and corals is maintained only in a nonequilibrium state. Science 1978, 199, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, J.-F.; Sabatier, D. Tree diversity in tropical rain forests: A validation of the intermediate disturbance hypothesis. Science 2001, 294, 1702–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, F.; Poorter, L.; Hawthorne, W.D.; Sheil, D. The intermediate disturbance hypothesis applies to tropical forests, but disturbance contributes little to tree diversity. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, I.P.; Tigabu, M.; Oden, P.C. Species diversity and regeneration of old-growth seasonally dry Shorea robusta forests following gap formation. J. For. Res. 2025, 20, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F.; Camargo, J.L.C.; Luizão, R.C.C.; Laurance, S.G.; Pimm, S.L.; Bruna, E.M.; Stouffer, P.C.; Williamson, G.B.; Benítez-Malvido, J.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; et al. The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: A 32-year investigation. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Nishat, A.; Vacik, H. Anthropogenic disturbances and plant diversity of the Madhupur Sal forests (Shorea robusta C.F. Gaertn) of Bangladesh. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Manag. 2009, 5, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, D.R.; Thakur, C.L.; Katoch, N.; Sharma, J.P. Floristic diversity and dominance patterns of Sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.) forests in North Western Himalayas: Implications for conservation and sustainable management. Front. For. Glob. Change 2025, 8, 1524808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, H.G.; Seth, S.K. A Revised Survey of the Forest Types of India; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 1968; p. 404. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S.K.; Shukla, R.P. Plant diversity in managed Sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn.) forests of Gorakhpur, India: Species composition, regeneration and conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 2295–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, K.H.; Devoe, N.N. Ecological and anthropogenic niches of Sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.) forest and prospects for multiple-product forest management—A review. Forestry 2006, 79, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Howe, H.F. Species composition and fire in a dry deciduous forest. Ecology 2003, 84, 3118–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. Tree species diversity, composition and structure in the tropical moist deciduous forest of Kadigarh National Park, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Asian J. For. 2024, 8, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Pavel, M.A.A.; Harada, K.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Jentsch, A.; Uddin, M.B. Tree species diversity in relation to environmental variables and disturbance gradients in a northeastern forest in Bangladesh. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubair, A.N.M.; Rahman, M.S.; Sarmin, I.J.; Raihan, A. Tree diversity and regeneration dynamics toward forest conservation and environmental sustainability: A case study from Nawabganj Sal Forest, Bangladesh. J. Agric. Sustain. Environ. 2023, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabha, D. Species composition and structure of Sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.) forests along disturbance gradients of Western Assam, Northeast India. Trop. Plant Res. 2014, 1, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, I.P.; Tigabu, M.; Oden, P.C. Spatial distribution, advanced regeneration and stand structure of Nepalese Sal (Shorea robusta) forests subject to disturbances of different intensities. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1966–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. Effects of light intensity on seed germination and early growth of Spondias mombin seedlings in Bangladesh. Cell Biol. Dev. 2023, 7, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.; Forstenhäusler, N.; Graham, E.; Osborn, T.J.; Warren, R. Report on the observed climate, projected climate, and projected biodiversity changes for Dharmapur under differing levels of warming; Wallace Initiative, University of East Anglia: Norwich, UK, 2024; Available online: https://wallaceparcs.uea.ac.uk/Bangladesh/Dharmapur.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Chapagain, U.; Chapagain, B.P.; Nepal, S.; Manthey, M. Impact of disturbances on species diversity and regeneration of Nepalese Sal (Shorea robusta) forests managed under different management regimes. Earth 2021, 2, 826–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, L.; Korhonen, K.T.; Rautiainen, M.; Stenberg, P. Estimation of forest canopy cover: A comparison of field measurement techniques. Silva Fenn. 2006, 40, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratovonamana, R.Y.; Rajeriarison, C.; Roger, E.; Kiefer, I.; Ganzhorn, J.U. Impact of livestock grazing on forest structure, plant species composition and biomass in southwestern Madagascar. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 95, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J.L.; Pieper, R.D.; Herbel, C.H. Range Management: Principles and Practices, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, U. A case of high tree diversity in a Sal (Shorea robusta)-dominated lowland forest of Eastern Himalaya: Floristic composition, regeneration and conservation. Curr. Sci. 2001, 81, 776–786. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24106397 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Thiele, J.; Schulte Auf’M Erley, G.; Glemnitz, M.; Gabriel, D. Efficiency of spatial sampling designs in estimating abundance and species richness of carabids at the landscape level. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, D.G.; Mohr, M.S.; Newman, K.B. Stratified sampling. In Sampling Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, O.L.; Vásquez Martínez, R.; Núñez Vargas, P.; Lorenzo Monteagudo, A.; Chuspe Zans, M.-E.; Galiano Sánchez, W.; Peña Cruz, A.; Timaná, M.; Yli-Halla, M.; Rose, S. Efficient plot-based floristic assessment of tropical forests. J. Trop. Ecol. 2003, 19, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condit, R. Tropical Forest Census Plots; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.U.; Begum, Z.N.T.; Hassan, M.A.; Khondker, M.; Kabir, S.M.H.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, A.T.A.; Rahman, A.K.A.; Haque, E.U. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Flora and Fauna of Bangladesh; Asiatic Society of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2008–2009; Vols. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- World Flora Online. WFO Plant List, December 2023 release. World Flora Online Consortium. Available online: https://wfoplantlist.org/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Lemmon, P.E. A spherical densiometer for estimating forest overstory density. For. Sci. 1956, 2, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, S. Assessing forest canopies and understorey illumination: Canopy closure, canopy cover and other measures. Forestry 1999, 72, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. Allometric modeling for leaf area and leaf biomass estimation of Swietenia mahagoni in the north-eastern region of Bangladesh. J. For. Environ. Sci. 2014, 30, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. Modeling develops to estimate leaf area and leaf biomass of Lagerstroemia speciosa in West Vanugach Reserve Forest of Bangladesh. ISRN For. 2014, 2014, 486478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.T.; McIntosh, R.P. An upland forest continuum in the prairie-forest border region of Wisconsin. Ecology 1951, 32, 476–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R. Ecology Workbook; Oxford & IBH Publishing Co.: New Delhi, India, 1968.

- Curtis, J.T. The Vegetation of Wisconsin: An Ordination of Plant Communities; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Song, W.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S. Global high-resolution forest disturbance type dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Mahapatra, C.K.; Biswas, S.K.; Das, P.; Majumdar, A. Suitability of the normal, log-normal and Weibull distributions for modeling diameter and height distributions of Swietenia mahagoni plantations in Bangladesh. J. Biol. Nat. 2018, 8, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mansingh, A.; Pradhan, A.; Sahoo, S.R.; Cherwa, S.S.; Mishra, B.P.; Rath, L.P.; Ekka, N.J.; Panda, B.P. Tree diversity, population structure, biomass accumulation, and carbon stock dynamics in tropical dry deciduous forests of Eastern India. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2025, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall/Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 944. ISBN 9780131008465. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package (Version 2.7-1) [R package]. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Das, N.; Sarker, S.K. Tree species diversity and productivity relationship in the central region of Bangladesh. J. For. 2015, 2, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, M.C.; Sahoo, U.K.; Mohanty, T.L.; Prus, P.; Smuleac, L.; Pascalau, R. Species composition and diversity of plants along human-induced disturbances in tropical moist Sal forests of Eastern Ghats, India. Forests 2023, 14, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, T.P.; Mandal, T.N. Effect of disturbance on plant species diversity in moist tropical Sal forests of eastern Nepal. Our Nat. 2018, 16, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.K.; Sato, N. Deforestation, land conversion and illegal logging in Bangladesh: The case of the Sal (Shorea robusta) forests. iForest 2012, 5, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disturbance category | Disturbance Index (%) | Disturbance Factors (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grazing | Cut stump density | Canopy cover | Fuelwood collection | NTFPs collection | Litter collection | Forest fire | Settlement distance | Road distance | ||

| LD | 33.3 | 17.6 | 3.5 | 74.3 | 1.2 | 7.8 | 12.5 | 13.6 | 26.5 | 29.1 |

| MD | 51.8 | 32.3 | 11.4 | 56.1 | 1.9 | 9.3 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 36.7 | 48.4 |

| HD | 77.7 | 45.7 | 17.2 | 31.6 | 4.4 | 21.7 | 26.8 | 15.1 | 69.2 | 71.6 |

| Parameter | LD | MD | HD | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Species | 35 | 25 | 17 | - | - |

| Number of Family | 19 | 15 | 10 | - | - |

| Number of Genera | 27 | 21 | 15 | - | - |

| Shannon–Wiener index (H′) | 2.36 ± 0.07 | 2.24 ± 0.05 | 2.12 ± 0.05 | 4.25 | <0.001 |

| Pielou’s evenness (J′) | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 17.12 | 0.006 |

| Simpson’s dominance (D) | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 3.78 | 0.001 |

| Tree density | 802 ± 86.3 | 585 ± 61.4 | 397 ± 36.2 | 48.42 | <0.001 |

| Basal Area | 25.7 ± 3.8 | 18.6 ± 2.1 | 13.4 ± 1.8 | 22.57 | <0.001 |

| Name of species |

Family |

Disturbance Category | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | MD | HD | ||||||||

| TD (ind. ha-1) |

BA (m2 ha-1) |

IVI | TD (ind. ha-1) |

BA (m2 ha-1) |

IVI | TD (ind. ha-1) |

BA (m2 ha-1) |

IVI | ||

| Acacia auriculiformis A.Cunn. ex Benth. | Fabaceae | 36 | 2.31 | 34.1 | 14 | 1.14 | 25.01 | 8 | 1.2 | 10.13 |

| Ardisia solanacea Roxb. | Primulaceae | 2 | 0.16 | 1.01 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | Moraceae | 20 | 1.15 | 12.59 | 24 | 1.61 | 20.56 | 16 | 1.19 | 17.8 |

| Artocarpus lacucha Buch.-Ham. | Moraceae | 6 | 0.16 | 3.99 | 4 | 0.19 | 2.32 | 4 | 0.24 | 4.2 |

| Bauhinia acuminata L. | Fabaceae | 28 | 1.23 | 15.95 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bombax ceiba L. | Malvaceae | 6 | 0.16 | 3.13 | 12 | 0.62 | 13.27 | 6 | 0.34 | 7.81 |

| Butea monosperma (Lam.) Taub. | Fabaceae | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 0.22 | 4.24 |

| Cassia fistula L. | Fabaceae | 18 | 0.6 | 12.19 | 14 | 0.76 | 11.56 | 8 | 0.53 | 6.43 |

| Cassia javanica L. | Fabaceae | 2 | 0.04 | 0.93 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cassia roxburghii DC. | Fabaceae | 6 | 0.43 | 5.05 | 2 | 0.04 | 5.35 | - | - | - |

| Dillenia indica L. | Dilleniaceae | 8 | 0.37 | 11.09 | 4 | 0.07 | 3.37 | - | - | - |

| Dipterocarpus turbinatus C.F.Gaertn. | Dipterocarpaceae | 60 | 3.39 | 37.49 | 15 | 1.95 | 13.67 | - | - | - |

| Elaeocarpus serratus L. | Elaeocarpaceae | - | - | - | 11 | 0.13 | 6.37 | 6 | 0.3 | 7.6 |

| Ficus benghalensis L. | Moraceae | 2 | 0.12 | 3.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ficus benjamina L. | Moraceae | 4 | 0.1 | 2.24 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ficus hispida L.f. | Moraceae | 38 | 6.34 | 37.25 | 24 | 4.12 | 29.93 | 4 | 0.43 | 5.47 |

| Ficus rumphii Bl. | Moraceae | 22 | 1.04 | 14.13 | 10 | 0.33 | 8.27 | - | - | - |

| Flacourtia indica (Burm.f.) Merr. | Salicaceae | 24 | 0.58 | 18.33 | 34 | 1.02 | 26.76 | - | - | - |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | Lamiaceae | 54 | 2.93 | 44.99 | - | - | - | 4 | 0.29 | 4.86 |

| Hydrolea zeylanica (L.) Vahl | Hydroleaceae | 6 | 0.31 | 4.35 | 24 | 0.71 | 18.35 | - | - | - |

| Lagerstroemia indica L. | Lythraceae | 40 | 2.28 | 31.99 | 32 | 1.4 | 24.38 | 38 | 1.86 | 32.93 |

| Lannea coromandelica (Houtt.) Merr. | Anacardiaceae | 18 | 1.23 | 24.9 | 20 | 0.99 | 14.41 | 10 | 0.29 | 12.32 |

| Litsea monopetala (Roxb.) Pers. | Lauraceae | 2 | 0.01 | 1.38 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Madhuca indica J.F. Gmel. | Sapotaceae | 8 | 0.1 | 6.16 | 6 | 0.13 | 4.1 | - | - | - |

| Mangifera indica L. | Anacardiaceae | 22 | 1.08 | 21.35 | 22 | 0.91 | 8.73 | - | - | - |

| Neolamarckia cadamba (Roxb.) Bosser | Rubiaceae | 32 | 5.98 | 38 | 24 | 5.47 | 34.11 | - | - | - |

| Phyllanthus acidus (L.) Skeels | Phyllanthaceae | 4 | 0.17 | 1.83 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Phyllanthus emblica L. | Phyllanthaceae | 20 | 1.12 | 11.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Semecarpus anacardium L.f. | Anacardiaceae | - | - | - | 2 | 0.07 | 1.19 | 2 | 0.05 | 1.02 |

| Shorea robusta Gaertn. f. | Dipterocarpaceae | 316 | 16.11 | 325.32 | 212 | 11.59 | 216.93 | 154 | 6.38 | 142.67 |

| Spondias pinnata (L.f.) Kurz | Anacardiaceae | 38 | 1.39 | 16.37 | 22 | 1.17 | 17.96 | 14 | 0.49 | 15.07 |

| Syzygium jambos L. (Alston) | Myrtaceae | 18 | 1.14 | 13.93 | - | - | - | 8 | 0.42 | 6.3 |

| Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.) Wight & Arn. | Combretaceae | 24 | 0.8 | 9.36 | 12 | 0.26 | 7.89 | - | - | - |

| Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb. | Combretaceae | 32 | 1.57 | 17.65 | 8 | 0.39 | 6.8 | 8 | 0.12 | 5.97 |

| Terminalia chebula Retz. | Combretaceae | 54 | 2.43 | 33.47 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Terminalia reticulata Engl. | Combretaceae | 58 | 3.12 | 47.92 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trema orientale (L.) Blume | Cannabaceae | 6 | 0.11 | 3.22 | 4 | 0.16 | 2.2 | 4 | 0.2 | 3.41 |

| Trewia nudiflora L. | Euphorbiaceae | - | - | - | 4 | 0.22 | 2.92 | - | - | - |

| Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. | Rhamnaceae | 8 | 0.21 | 2.58 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Disturbance Category | Jaccard Index | Bray-Curtis Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | MD | HD | LD | MD | HD | ||

| LD | 1 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.82 | |||

| MD | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 0.80 | |||

| HD | 0.69 | 0.72 | 1 | 1 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).