Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

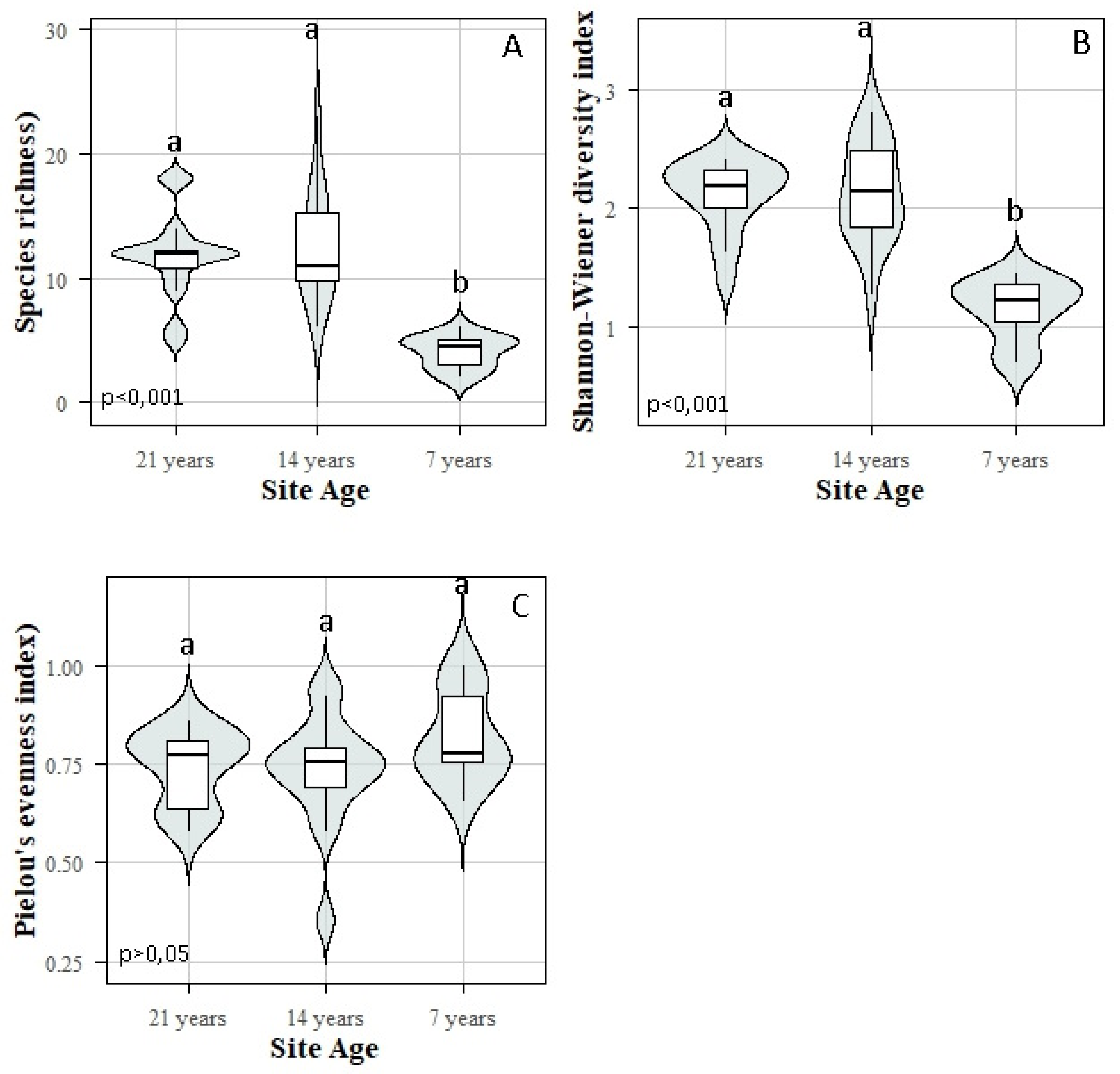

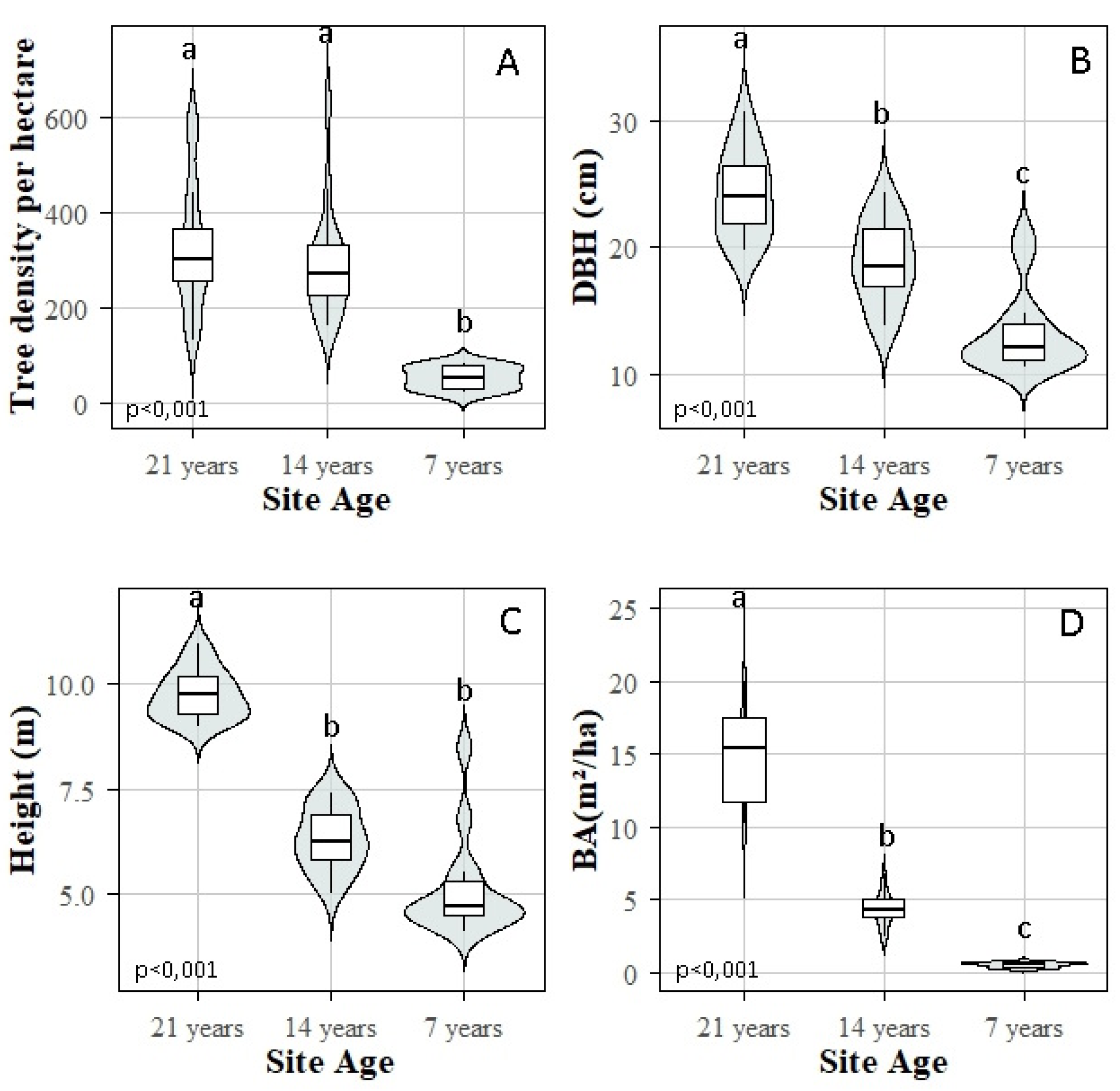

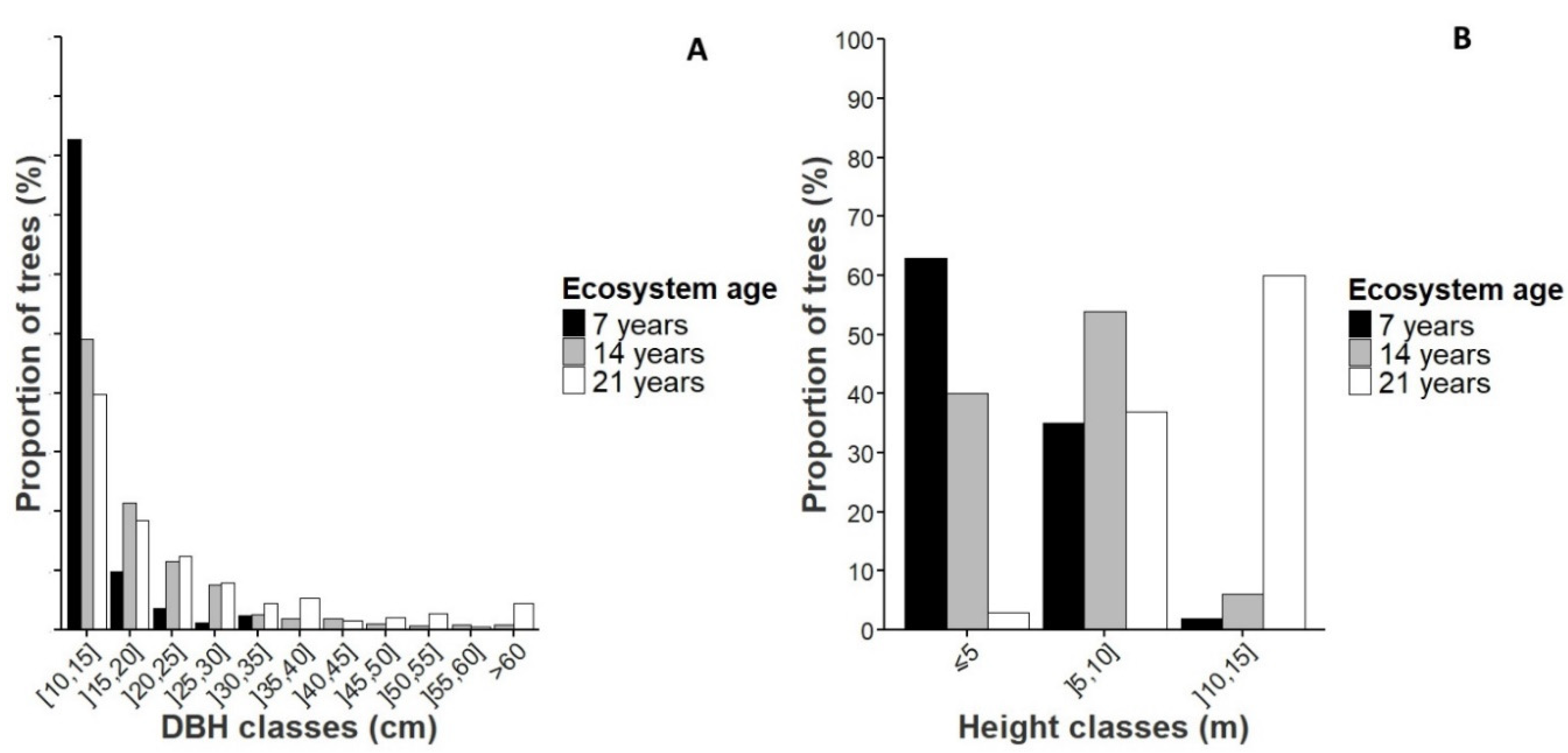

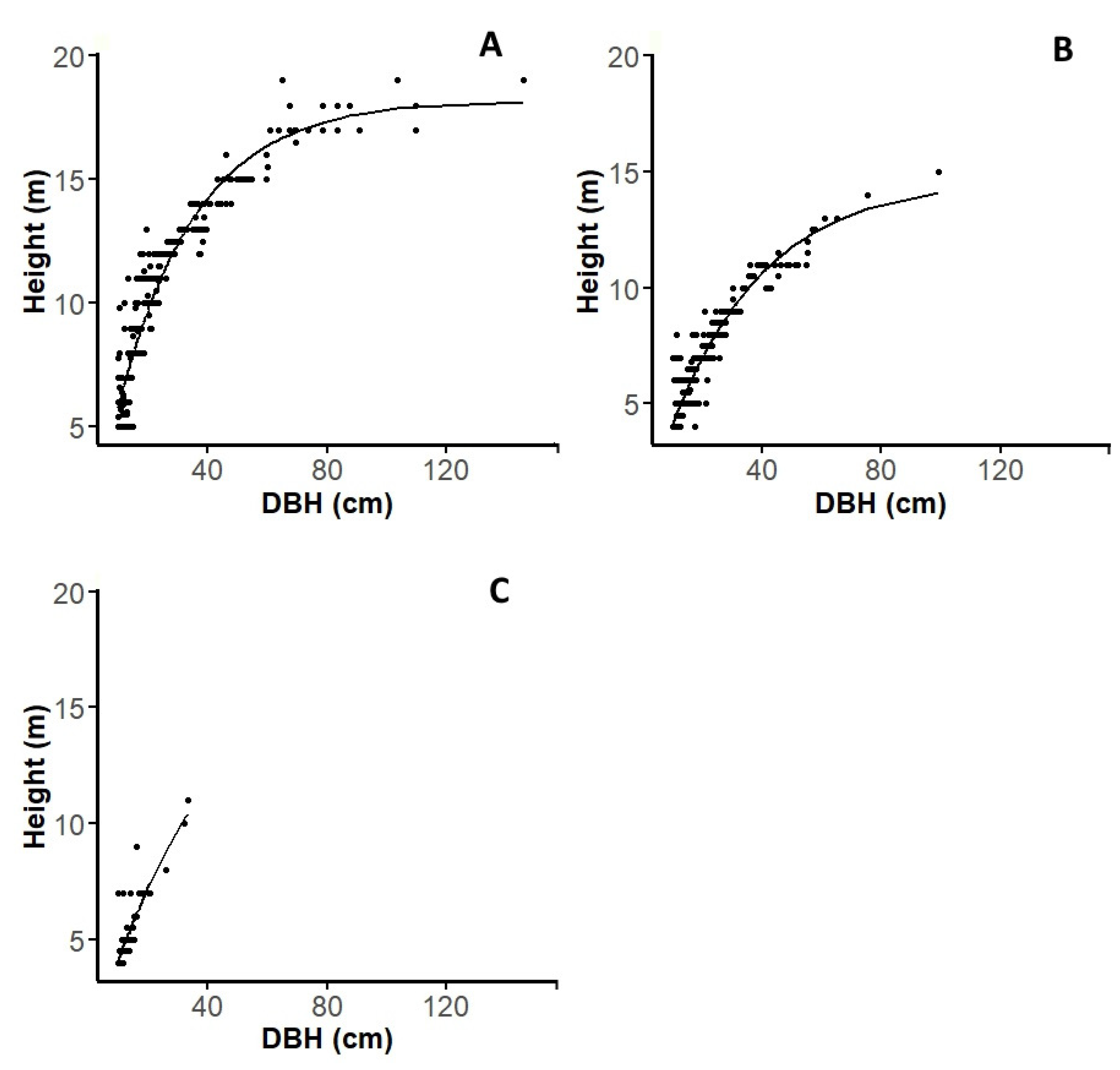

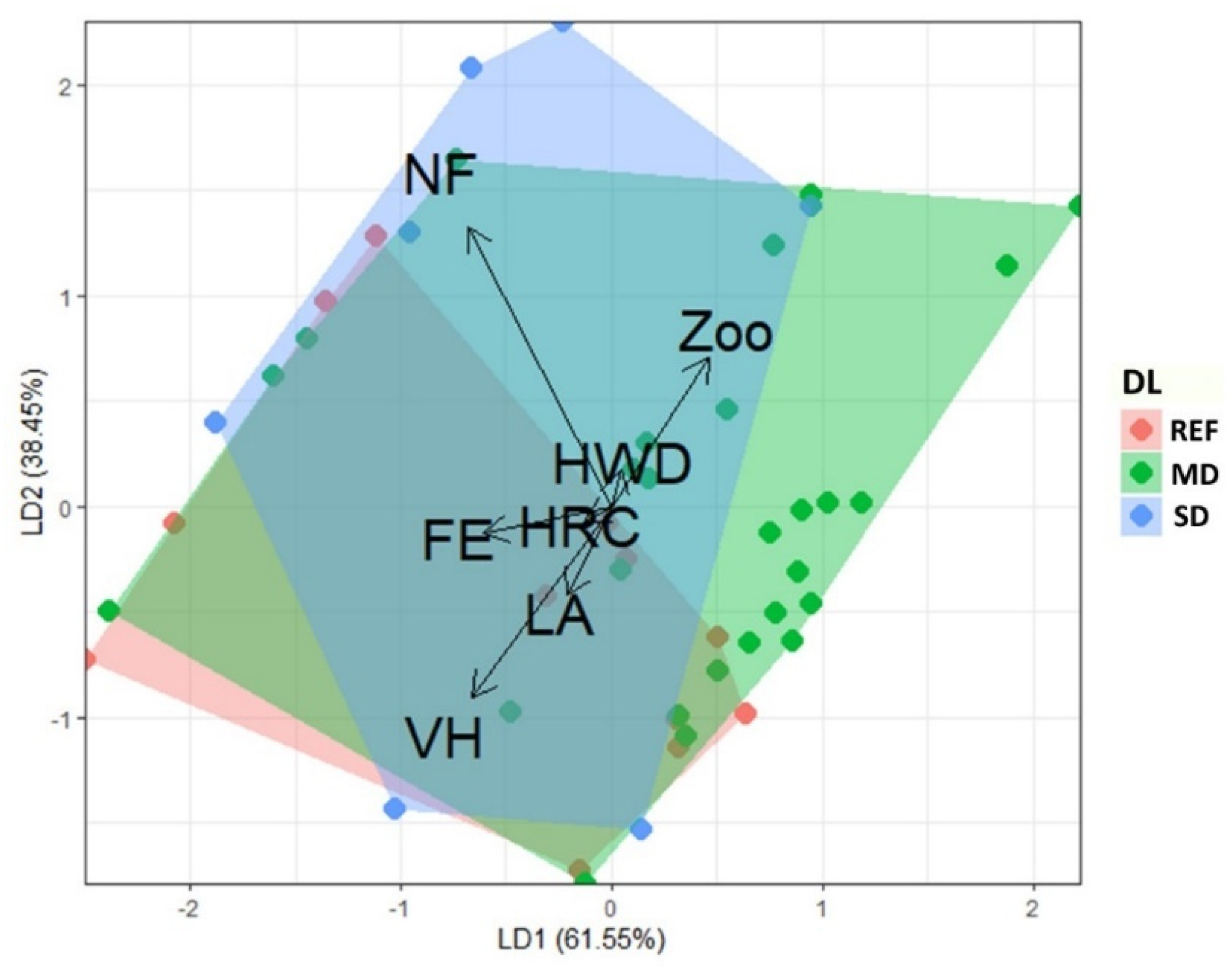

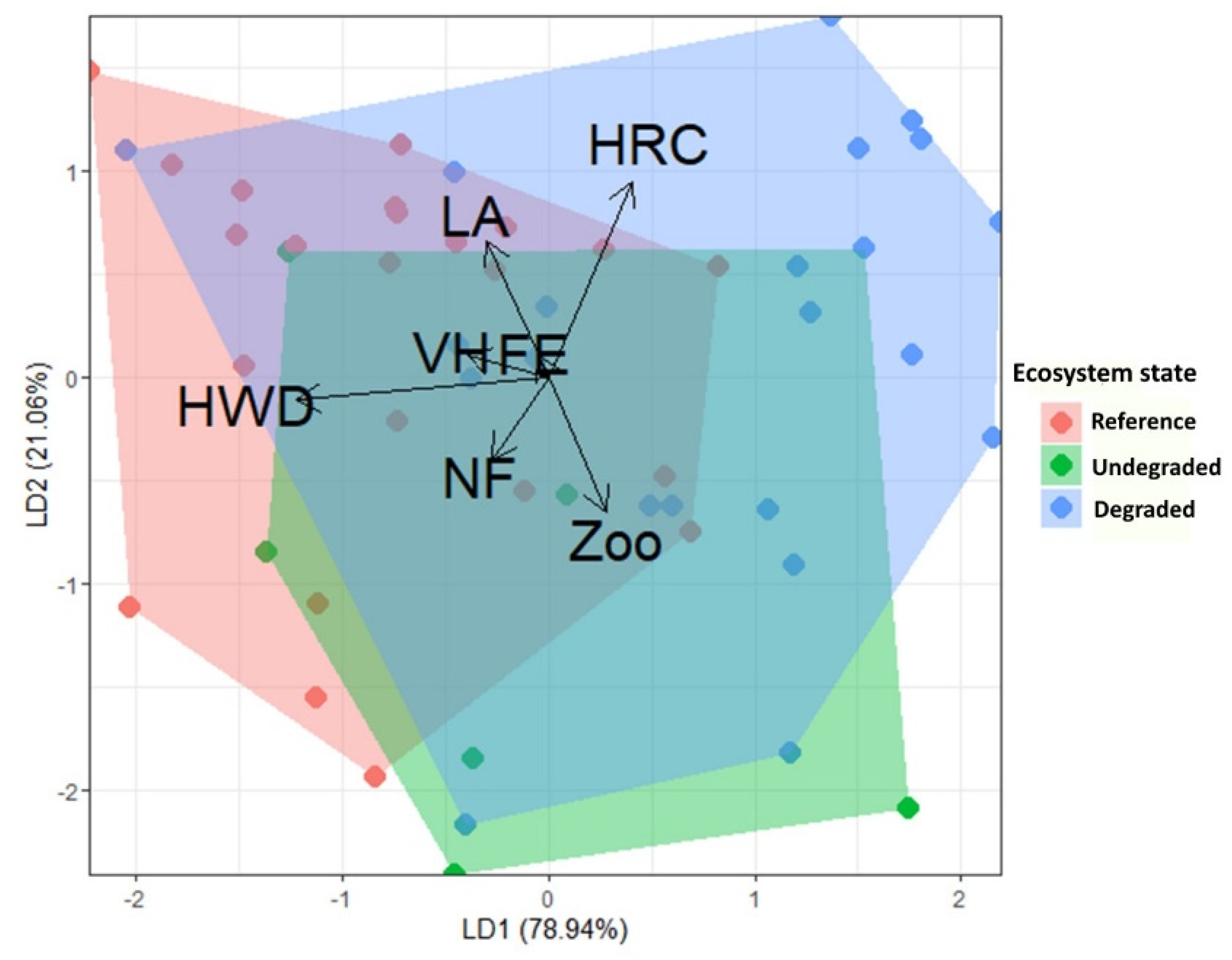

Miombo woodlands in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (LCPB) provide critical ecosystem services and harbor biodiversity essential to both rural and urban populations. However, increasing energy demands intensify anthropogenic pressures, threatening their long-term sustainability. This study evaluates the principal anthropogenic drivers and biodiversity disturbance indicators across three developmental stages (7, 14, and 21 years) of miombo woodlands within the LCPB. Transect-based inventories assessed disturbance gradients, while plot-based surveys examined floristic composition and structure. Functional trait data were obtained from specialized online ecological databases. Results indicate that forest degradation within the LCPB is primarily driven by charcoal-related wood harvesting, fire events, and agricultural expansion, whereas exotic species invasion, debarking, and artisanal mining exert comparatively minor impacts. Disturbance patterns did not correlate significantly with proximity to villages, despite logging, fire, and agriculture being strongly interrelated. Analysis of the developmental stages revealed significant variations in biodiversity and dendrometric indicators. The highly degraded 7-year-old stage exhibited low floristic diversity, dominated by species such as Isoberlinia angolensis (abundance = 22), Julbernardia paniculata (18), and Brachystegia wangermeeana (6), and had poor structural metrics (90 individuals, 51 trees/ha, average DBH of 11.56 cm, average height of 4.47 m). The intermediate 14-year-old stage showed increased species diversity, notably B. wangermeeana (83), Brachystegia spiciformis (56), and Albizia adianthifolia (48), alongside improved structural values (456 individuals, 285 trees/ha, average DBH of 18.83 cm, average height of 6.31 m). The least degraded 21-year-old stage had the highest floristic diversity and structural values, with dominant species Marquesia macroura (88), Diplorhynchus condylocarpon (64), and Julbernardia globiflora (71), totaling 519 individuals, 323 trees/ha, average DBH of 24.20 cm, and average height of 9.64 m. Furthermore, ecosystem condition influenced functional traits, with disturbed areas favoring zoochorous dispersal and natural regeneration, but reducing wood density and nitrogen fixation. These findings underscore severe threats to LCPB woodlands and emphasize the importance of forest degradation stages in woodland development and resilience. Immediate action is recommended to regulate wood harvesting strictly, criminalize uncontrolled fires, monitor agriculture, and protect degraded areas to foster miombo woodland regeneration.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

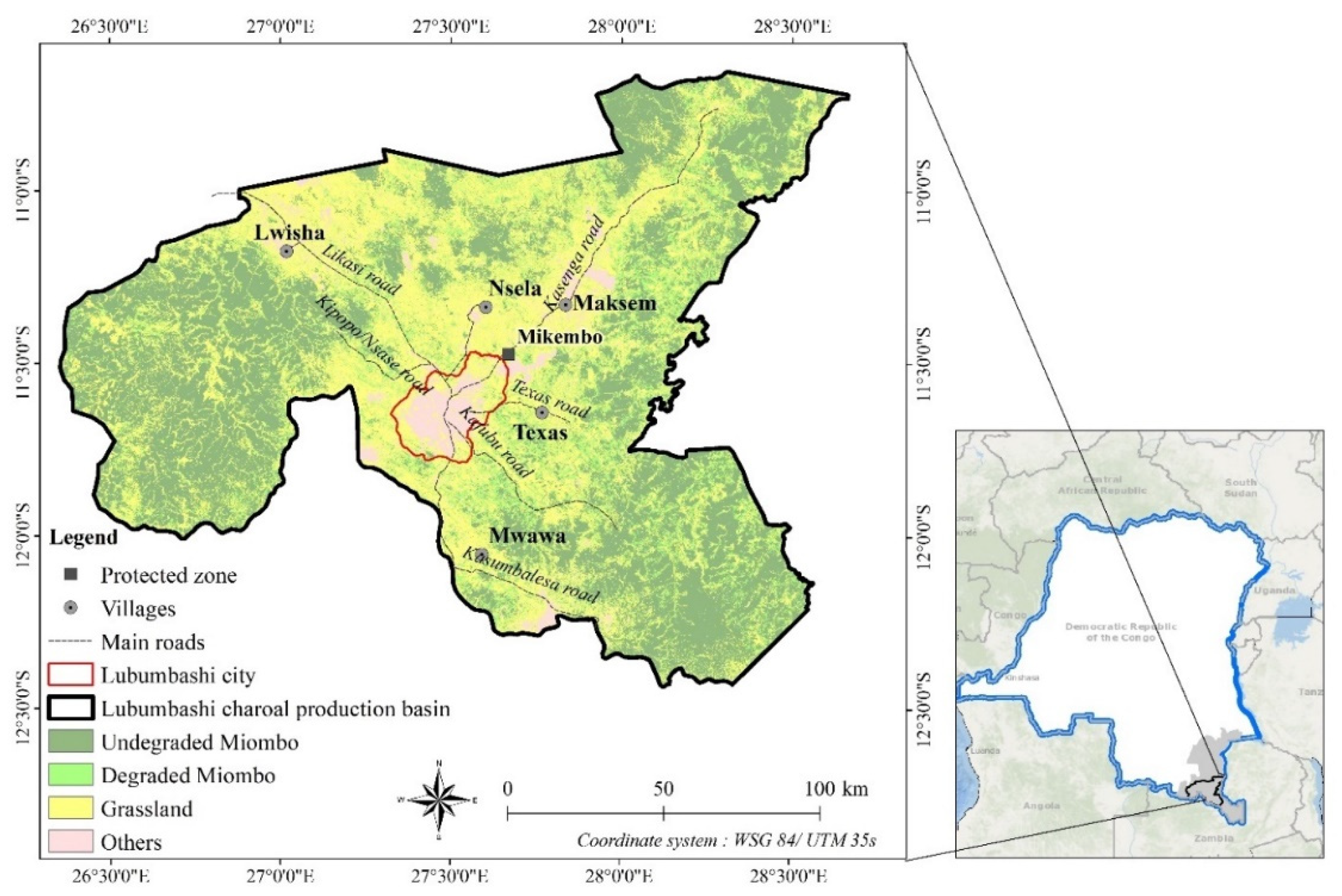

2.1. Study Area

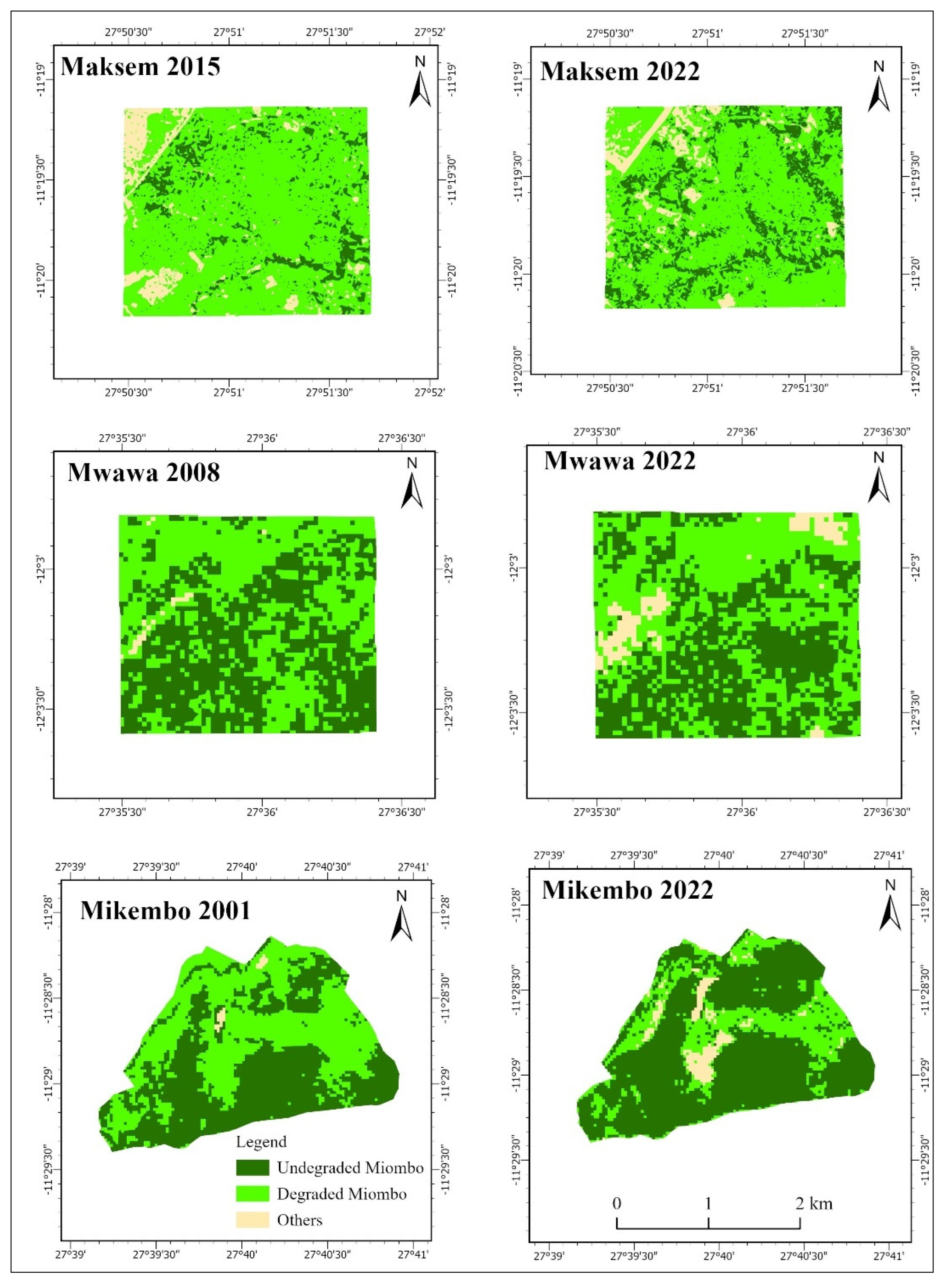

2.2. Study Site Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Identification of Disturbance Factors in the LCPB

2.3.2. Collection of Floristic and Dendrometric Data

2.3.3. Collection of Functional Trait Data

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Analysis of Disturbance Factors

2.4.2. Analysis of Floristic and Dendrometric Parameters

2.4.3. Functional Trait Analysis

3. Results

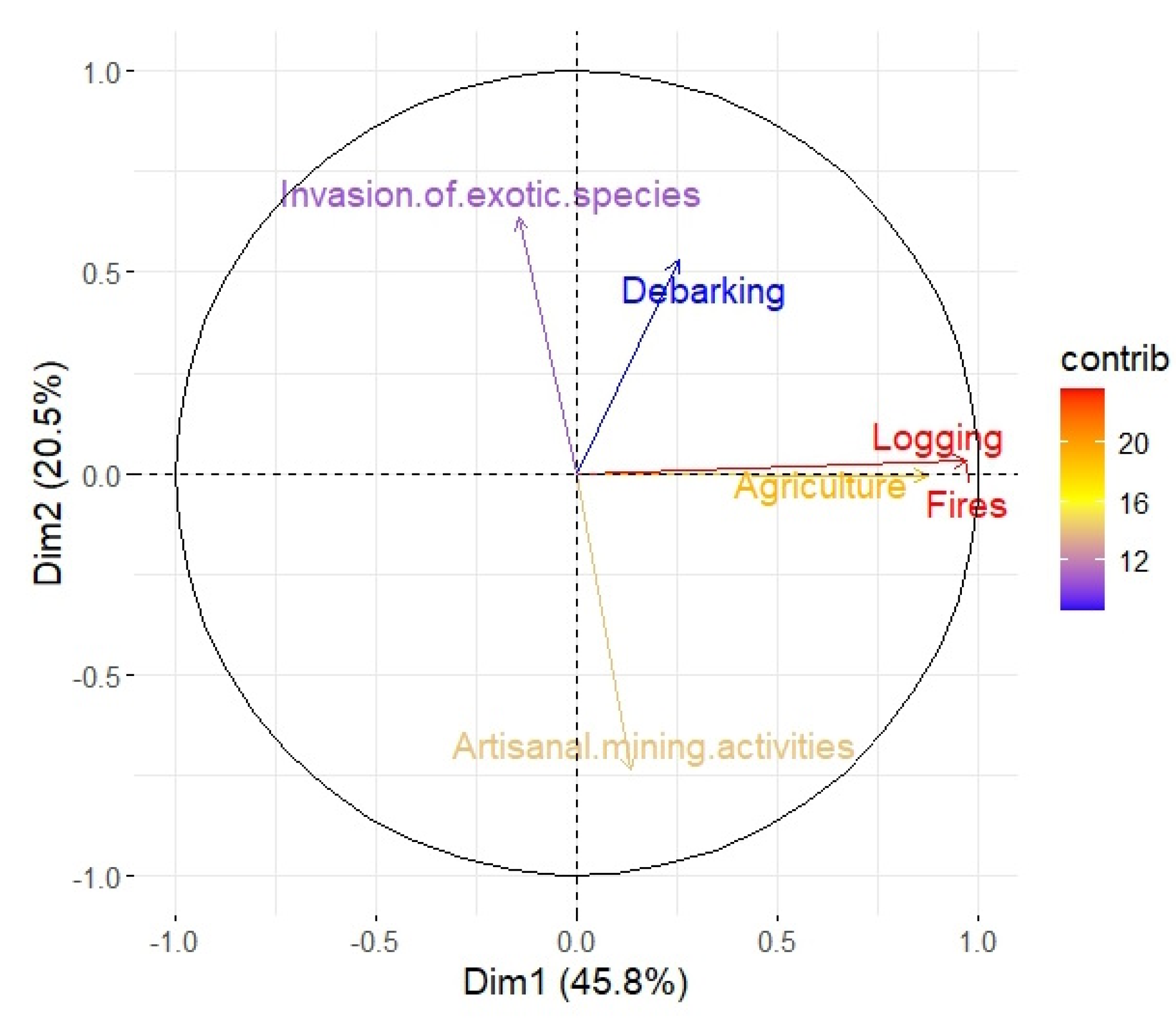

3.1. Degradation Factors Affecting Woodland Biodiversity in the LCPB

3.2. Floristic Composition and Diversity

3.3. Dendrometric Parameters

3.4. Functional Trait Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Approach

4.2. Miombo Degradation Factors in the LCPB

4.3. Floristic and Dendrometric Indicators of Miombo Degradation in the LCPB

4.4. Impact de la Dégradation Forestière sur les Traits Fonctionnels

4.5. Implications for Forest Management

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jhariya, M.K.; Banerjee, A.; Meena, R.S.; Yadav, D.K. Agriculture, Forestry and Environmental Sustainability: A Way Forward. In Sustainable Agriculture, Forest and Environmental Management; Jhariya, M.K., Banerjee, A., Meena, R.S., Yadav, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 9789811368301. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO FRA 2015 Termes et Définitions; document de travail de l’évaluation des ressources forestières; Organisation des Nations-Unies pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture: Rome, 2012.

- Lapola, D.M.; Pinho, P.; Barlow, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Berenguer, E.; Carmenta, R.; Liddy, H.M.; Seixas, H.; Silva, C.V.J.; Silva-Junior, C.H.L.; et al. The Drivers and Impacts of Amazon Forest Degradation. Science 2023, 379, eabp8622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujino, R.; Yumoto, T.; Kitamura, S.; Djamaluddin, I.; Darnaedi, D. History of Forest Loss and Degradation in Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Évaluation des ressources forestières mondiales 2020; FAO ;, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134306-7.

- Zhao, Z.; Li, W.; Ciais, P.; Santoro, M.; Cartus, O.; Peng, S.; Yin, Y.; Yue, C.; Yang, H.; Yu, L.; et al. Fire Enhances Forest Degradation within Forest Edge Zones in Africa. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.S.; Syampungani, S.; Matakala, N.M.; Nangoma, D.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I. Miombo Woodlands Research Towards the Sustainable Use of Ecosystem Services in Southern Africa. In Biodiversity in Ecosystems - Linking Structure and Function; Lo, Y.-H., Blanco, J.A., Roy, S., Eds.; InTech, 2015; pp. 475–491 ISBN 978-953-51-2028-5.

- Ryan, C.M.; Williams, M. How Does Fire Intensity and Frequency Affect Miombo Woodland Tree Populations and Biomass? Ecological Applications 2011, 21, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.S.; Silva de Miranda, P.L.; Timberlake, J. Biogeography and Ecology of Miombo Woodlands. In Miombo Woodlands in a Changing Environment: Securing the Resilience and Sustainability of People and Woodlands. In Miombo Woodlands in a Changing Environment: Securing the Resilience and Sustainability of People and Woodlands; Ribeiro, N.S., Katerere, Y., Chirwa, P.W., Grundy, I.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-50104-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nduwarugira, D.; Mpawenayo, B.; Roisin, Y. The Role of High Termitaria in the Composition and Structure of the Termite Assemblage in Miombo Woodlands of Southern Burundi. Insect Conservation and Diversity 2017, 10, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo, E.N.; Gumbo, D.J. The Environmental Impacts of Charcoal Production in Tropical Ecosystems of the World: A Synthesis. Energy for Sustainable Development 2013, 17, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de l’Environnement, Conservation de la Nature et Tourisme Synthèse Des Études Sur Les Causes de La Déforestation et de La Dégradation Des Forêts En République Démocratique Du Congo; Version finale; 2012.

- Potapov, P.V.; Turubanova, S.A.; Hansen, M.C.; Adusei, B.; Broich, M.; Altstatt, A.; Mane, L.; Justice, C.O. Quantifying Forest Cover Loss in Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000–2010, with Landsat ETM+ Data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 122, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaisse, F. How to Live and Survive in Zambezian Open Forest (Miombo Ecoregion). Les presses agronomiques de Gembloux Gembloux 2010, 23, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Meerts, P.; Hasson., M. Arbres et arbustes du Haut-Katanga; Jardin Botanique de Meise, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, S.Y.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala, K.S.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bogaert, J. Le rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (HautKatanga, R.D. Congo): synthèse. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Kabulu, D.J.-P.; Vranken, I.; Bastin, J.-F.; Malaisse, F.; Nyembwe, N.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Ngongo, L.M.; Bogaert, J. Approvisionnement En Charbon de Bois Des Ménages Lushois : Quantités, Alternatives et Conséquences. In Anthropisation des paysages katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Liège: Liège, Belgique, 2018; pp. 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Khoji, M.H.; N’Tambwe, D.-D.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Cabala, K.S.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M.H.; N’Tambwe, N.D.-D.; Mwamba, K.F.; Strammer, H.; Munyemba, K.F.; Malaisse, F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Useni, S.Y.; Bogaert, J. Mapping and Quantification of Miombo Deforestation in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo): Spatial Extent and Changes between 1990 and 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasongo, L.M.E.; Mwamba, M.T.; Tshipoya, M.P.; Mukalay, M.J.; Useni, S.Y.; Mazinga, K.M.; Nyembo, K.L. Réponse de La Culture de Soja (Glycine Max L. (Merril) à l’apport Des Biomasses Vertes de Tithonia Diversifolia (Hemsley) A. Gray Comme Fumure Organique Sur Un Ferralsol à Lubumbashi, R.D. Congo. Journal of Applied Biosciences 2013, 63, 4727–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igini, M. Deforestation in Africa: Causes, Effects, and Solutions Available online:. Available online: https://earth.org/deforestation-in-africa/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Useni, S.Y.; Cabala, K.S.; Halleux, J.M.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Caractérisation de la croissance spatiale urbaine de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo) entre 1 989 et 201 4. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cabala, K.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Amisi, M.Y.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Analyse structurale de la dynamique forestiere dans la région de I’Arc Cuprifére Katangais en République Démocratique du Congo: II. Analyse complémentaire de la fragmentation forestiere. Pattern Analysis of Forest Dynamics of the Katangese Copper Belt Region in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: II. Complementary Analysis on Forest Fragmentation 2018, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Mpanda, M.M.; Khoji, M.H.; N’Tambwe, N.D.-D.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala, K.S.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus Tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilunga, M.J.; drouet, T.; Lejolly, J.; Ngongo, L.M.; Ngoy, S.M.; Meerts, P. Les Dispositifs Permanents Du «Sanctuaire Mikembo» (Haut-Katanga), Des Outils Pour Le Monitoring de La Forêt Claire Katangaise Anthropisée. In Anthropisation des paysages katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Liège: Liège, Belgique, 2018; pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nkulu, F.Y.; Mwamba, C.T.; Kimonge, I.M.; Djibu, K. Contribution à l’estimation de la biomasse aérienne des forêts Miombo du Haut Katanga : Etude préliminaire (RD Congo). 2018, 24.

- Useni, S.Y.; Khoji, M.H.; Langunu, S.; EBUY, A.J.; Munyemba, K.F. Structure des peuplements ligneux des formations végétales d’un paysage protégé en zone périurbaine de la ville de Lubumbashi (RD Congo). Geo-Eco-Trop 2019, 44, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- N’tambwe, N.D.; Khoji, M.H.; Salomon, W.; Cuma, M.F.; Malaisse, F.; Ponette, Q.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Floristic Diversity and Natural Regeneration of Miombo Woodlands in the Rural Area of Lubumbashi, D.R. Congo. Diversity 2024, 16, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessenmöller, D.; Elsenhans, A.-S.; Schulze, E.D. Sampling Forest Tree Regeneration with a Transect Approach. Annals of Forest Research 2013, 56, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotondrasoa, L.O.; Ayral, A.; Stein, J.; Rajoelison, G.L.; Ponette, Q.; Malaisse, F.; Ramamonjisoa, B.; Raminosoa, N.; Verheggen, F.; Poncelet, M.; et al. Analyse des facteurs anthropiques de dégradation des bois de tapia (Uapaca bojeri) d’Arivonimamo. In Les vers à soie malgaches. Enjeux écologiques et socio-économiques; Verheggen, F., Bogaert, J., Haubruge, E., Eds.; Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgique, 2013; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Rakotondrasoa, L.O.; Malaisse, F.; Rajoelison, G.L.; Gaye, J.; Razafimanantsoa, T.M.; Rabearisoa, M.R.; Ramamonjisoa, B.S.; Raminosoa, N.; Verheggen, F.; Poncelet, M.; et al. Identification des indicateurs de dégradation de la forêt de tapia (Uapaca bojeri) par une analyse sylvicole. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thiombiano, A.; Glele, K.; Bayen, P.; Boussim, J.I.; Mahamane, A. Méthodes et disposotifs d’inventaires en Afrique de l’Oeust : Etat des lieux et propositions pour une harminisation. Annales des Sciences Agronomiques - spécial Projet Undesert-UE 2016, 20, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Banza, W.B.B.; Kiseya, T.F.; Bouillard, P. Spatial Distribution of Electrical Infrastructures: Impact of Urban Sprawl in Lubumbashi, DR Congo. Asian Journal of Industrial Engineering 2016, 8, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. metz 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalombo Evaluation Des Éléments Du Climat En R.D.C.; Omn.univ.europ.; Editions Universitaires Européennes.; Saarbrücken (Allemagne), 2016.

- Kasongo, L.M.E.; Baert, G.; Ngongo, L.M.; Verdoodt, A.; Van Ranst, E. Esquise Des Pédopaysages Du Katanga et Aperçu Sur Les Potentialités Agricoles et Activités Minières. In Anthropisation despaysages katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Liège: Liège, Belgique, 2018; pp. 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Population Prospects; UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3., 2022.

- Kalambulwa, N.A.; Kakule, M.S.; Mumba, T.U.; Lobho, L.J. Dynamics of the Forest Landscape in the Mikembo Sanctuary: 20 Years after Its Creation as a Flora and Fauna Conservation Reserve, Upper-Katanga, DR Congo. Environment & Ecosystem Science 2023, 7, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Polain de Waroux, Y. Environmental Degradation and Economic Development in the Argan Woodlands of Aoulouz (Morocco). Science et Changements Planetaires - Secheresse 2013, 24, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giliba, R.A.; Mafuru, C.S.; Paul, M.; Kayombo, C.J.; Kashindye, A.M.; Chirenje, L.I.; Musamba, E.B. Human Activities Influencing Deforestation on Meru Catchment Forest Reserve, Tanzania. Journal of Human Ecology 2011, 33, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameja, L.G.; Ribeiro, N.; Sitoe, A.A.; Guillot, B. Regeneration and Restoration Status of Miombo Woodland Following Land Use Land Cover Changes at the Buffer Zone of Gile National Park, Central Mozambique. Trees, Forests and People 2022, 9, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallmeier, F. Long-Term Monitoring of Biological Diversity in Tropical Forest Areas: Methods for Establishment and Inventory of Permanent Plots; Man and Biosphere Digest 11, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization., Ed.; UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Paris, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ilunga, M.J.; Bauman, D.; Drouet, T.; Vleminckx, J.; Jacobs, A.; Lejoly, J.; Meerts, P.; Shutcha, M.N. Fine-Scale Habitats Influence Tree Species Assemblage in a Miombo Forest. Journal of Plant Ecology 2017, 10, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, J.; Garzon-Lopez, C.X.; Yeager, L.; Fortunel, C.; Cordeiro, N.J.; Beckman, N.G. The Effects of Habitat Loss and Fragmentation on Plant Functional Traits and Functional Diversity: What Do We Know so Far? Oecologia 2019, 191, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W. Patterns and Uncertainties of Species’ Range Shifts under Climate Change. Global Change Biology 2004, 10, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, C.N.; Jackson, D.A. Reconstructing Community Relationships: The Impact of Sampling Error, Ordination Approach, and Gradient Length. Diversity and Distributions 2007, 13, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal Component Analysis: A Review and Recent Developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M.; Groenen, P.J.F.; Hastie, T.; D’Enza, A.I.; Markos, A.; Tuzhilina, E. Principal Component Analysis. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2022, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Walker, N.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Causton, D.R. An Introduction to Vegetation Analysis: Principles, Practice and Interpretation; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012; ISBN 978-94-011-9737-3.

- Macron, E. Mesures de La Biodiversité; UMR Écologie des forêts de Guyane, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, F.M.P.; Revermann, R.; Gomes, A.L.; Aidar, M.P.M.; Finckh, M.; Juergens, N. Tree Species Diversity and Composition of Miombo Woodlands in South-Central Angola: A Chronosequence of Forest Recovery after Shifting Cultivation. International Journal of Forestry Research 2017, 2017, e6202093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burju, T.; Hundera, K.; Kelbessa, E. Floristic Composition and Structural Analysis of Jibat Humid Afromontane Forest, West Shewa Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences 2013, 8, 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Savadogo, S.; Sambare, O.; Ouedraogo, I.; Thiombiano, A. Espèces exotiques indicatrices de dégradation des bois sacrés au Burkina Faso. Geo-Eco-Trop 2020, 44, 409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Borcard, D.; Gillet, F.; Legendre, P. Canonical Ordination. In Numerical Ecology with R; Borcard, D., Gillet, F., Legendre, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-71404-2. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. The Use of Transects for Resilient Design: Core Theories and Contemporary Projects. Landscape Ecol 2021, 36, 1567–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirche, A.; Salamani, M.; BOUGHANI, M.; Ratiba, H.; Zina, K.; Slimani, H.; Nedjraoui, D. Guide Technique Écologie Pour La Collecte, l’analyse Des Données et Le Calcul Des Indicateurs Écologiques Suivant l’approche Harmonisée; Observatoire du Sahara et du Sahel: OSS, Tunis, 2015; ISBN 978-9973-856-9-3. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity. Current Biology 2021, 31, R1174–R1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, C.; Lejeune, P.; Michez, A.; Fayolle, A. How Can Remote Sensing Help Monitor Tropical Moist Forest Degradation?—A Systematic Review. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R.; Doss, C. Analyzing Technology Adoption, Challenges and Limitations of Micro Studies. Agricultural economics 2006, 34, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, M. La Figure de l’enquêteur Dans Le Quartier de La Villeneuve de Grenoble. Les Politiques Sociales 2021, 1–2, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barima, S.S.Y.; Barbier, N.; Ouattara, B.; Bogaert, J. Relation entre la composition floristique et des indicateurs de la fragmentation du paysage dans une région de transition forêt-savane ivoirienne. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2010, 14, 617–625. [Google Scholar]

- Vinya, R.; Malhi, Y.; Brown, N.D.; Fisher, J.B.; Brodribb, T.; Aragão, L.E.O.C. Seasonal Changes in Plant–Water Relations Influence Patterns of Leaf Display in Miombo Woodlands: Evidence of Water Conservative Strategies. Tree Physiology 2019, 39, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano, F.; Mizu-Siampale, A.; Duncanson, L.; Liang, M. Influence of Charcoal Production on Forest Degradation in Zambia: A Remote Sensing Perspective. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doggart, N.; Meshack, C. The Marginalization of Sustainable Charcoal Production in the Policies of a Modernizing African Nation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péroches, A.; Nge, O.A.; Gazull, L.; Dubliez, E. Programme de Consommation Durable et Substitution Partielle Au Bois-Énergie. Rapport d’étude Sur La Filière Bois-Énergie de La Ville de Lubumbashi; CIRAD, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amisi, M.; Vranken, I.; Nkulu, M.F.J.; Lubala, T.R.F.; Kyanika, D.; Tshibang, N.S.; Mastaki, U.F.; Bulambo, J.-P.; Bogaert, J. L’activité Minière Au Katanga et La Perception de Ses Impacts à Lubumbashi. In Anthropisation des Paysages Katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2018; pp. 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Katumbi, N.; Nyengere, J.; Mkandawire, E. Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Dzalanyama Forest Reserve in Malawi. 2015, 6, 889–893. [Google Scholar]

- Sedano, F.; Silva, J.A.; Machoco, R.; Meque, C.H.; Sitoe, A.; Ribeiro, N.; Anderson, K.; Ombe, Z.A.; Baule, S.H.; Tucker, C.J. The Impact of Charcoal Production on Forest Degradation: A Case Study in Tete, Mozambique. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 094020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe, N.D.; Khoji, M.H.; Biloso, M.A.; Malaisse, F.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Socio-Economic Value and Availability of Plant-Based Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) within the Charcoal Production Basin of the City of Lubumbashi (DR Congo). Sustainability 2023, 15, 14943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda, M.M.; Khoji, M.H.; Cirezi, C.N.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Vegetation Fires in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (The Democratic Republic of the Congo): Drivers, Extent and Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Land 2023, 12, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda, M.M.; Malaisse, F.; Kazaba, K.P.; Bogaert, J. The Spatiotemporal Changing Dynamics of Miombo Deforestation and Illegal Human Activities for Forest Fire in Kundelungu National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fire 2023, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wilgen, B.W.; De Klerk, H.M.; Stellmes, M.; Archibald, S. An Analysis of the Recent Fire Regimes in the Angolan Catchment of the Okavango Delta, Central Africa. fire ecol 2022, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.; Edwards, D.P.; Giam, X.; Wilcove, D.S. The High Costs of Conserving Southeast Asia’s Lowland Rainforests. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2011, 9, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullison, R.E.; Frumhoff, P.C.; Canadell, J.G.; Field, C.B.; Nepstad, D.C.; Hayhoe, K.; Avissar, R.; Curran, L.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Jones, C.D.; et al. Tropical Forests and Climate Policy. Science 2007, 316, 985–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masolele, R.N.; Marcos, D.; De Sy, V.; Abu, I.-O.; Verbesselt, J.; Reiche, J.; Herold, M. Mapping the Diversity of Land Uses Following Deforestation across Africa. Scientific Reports 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala, K.S.; Kalumba, M.A.; Amisi, M.; Nkuku, K.C.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Tree Diversity and Structure on Green Space of Urban and Peri-Urban Zones: The Case of Lubumbashi City in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 41, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinlein, T. Invasive Alien Plants and Their Effects on Native Microbial Soil Communities. In Progress in Botany: Vol. 74; Lüttge, U., Beyschlag, W., Francis, D., Cushman, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-30967-0. [Google Scholar]

- Siachoono, S.M.; Syampungani, S.; Mundike, J. Invasive Alien Species in Zambia. Invasive Alien Species 2021, 1, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpouni, V.; Lenga-Sacadura, M.-Y.; Mamboueni, J.C.; Mikoko, E.N. Phytodiversite Et Pharmacopée Traditionnelle De La Communauté Kaamba De Madingou (Bouenza - Congo). ESJ 2018, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozanayi, W.; Wynberg, R.; Hoffman, M.T. Does Tenure Influence Sustainable Use? The Ecological Impacts of Harvesting Baobab (Adansonia Digitata). African Journal of Ecology 2022, 60, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.S.; Snook, L.K.; Nunes de Carvalho Vaz, I.C.; Alves, T. Gathering Honey from Wild and Traditional Hives in the Miombo Woodlands of the Niassa National Reserve, Mozambique: What Are the Impacts on Tree Populations? Global Ecology and Conservation 2019, 17, e00552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megevand, C.; Mosnier, A.; Hourticq, J.; Sanders, K.; Doetinchem, N.; Streck, C. Dynamiques de deforestation dans le basin du Congo: reconcilier la croissance economique et la protection de la foret; The World Bank: Washington, D.C, 2013; ISBN 978-0-8213-9838-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ncube-Phiri, S.; Ncube, A.; Mucherera, B.; Ncube, M. Artisanal Small-Scale Mining: Potential Ecological Disaster in Mzingwane District, Zimbabwe. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2015, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Ayral, A.; Rajoellison, L.G.; Ponette, Q.; Malaisse, F.; Ramamonjisoa, B.S.; Raminosoa, N.; Verheggen, F.J.; Poncelet, M.; Haubruge, É.; et al. Analyse Des Facteurs Anthropiques de Dégradation Des Bois de Tapia (Uapaca Bojeri) d’Arivonimamo. In Les vers à soie malgaches : Enjeux écologiques et socio-économiques; Verheggen, F., Bogaert, J., Haubruge, É., Eds.; Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux (Belgique), 2013; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hick, A.; Hallin, M.; Tshibungu, A.; Mahy, G. La Place de l’arbre Dans Les Systèmes Agricoles de La Région de Lubumbashi. In Anthropisation des paysages katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Eds.; Presses Universitaires de Liège – Agronomie-Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgique, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, N.; Allen, C.D.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; Brando, P.; Brienen, R.; Chambers, J.; Christoffersen, B.; Davies, S.; Doughty, C.; Duque, A.; et al. Drivers and Mechanisms of Tree Mortality in Moist Tropical Forests. New Phytologist 2018, 219, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewees, P.A.; Campbell, B.M.; Katerere, Y.; Sitoe, A.; Cunningham, A.B.; Angelsen, A.; Wunder, S. Managing the Miombo Woodlands of Southern Africa: Policies, Incentives and Options for the Rural Poor. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research 2010, 2, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.M.; Pritchard, R.; McNicol, I.; Owen, M.; Fisher, J.A.; Lehmann, C. Ecosystem Services from Southern African Woodlands and Their Future under Global Change. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 371, 20150312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.L.; Revermann, R.; Meller, P.; Gonçalves, F.M.P.; Aidar, M.P.M.; Lages, F.; Finckh, M. Functional Traits and Symbiotic Associations of Geoxyles and Trees Explain the Dominance of Detarioid Legumes in Miombo Ecosystems. New Phytologist 2021, 230, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deconchat, M.; Balent, G. Effets Des Perturbations Du Sol et de La Mise En Lumière Occasionnées Par l’exploitation Forestière Sur La Flore à Une Échelle Fine. Ann. For. Sci. 2001, 58, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giliba, R.A.; Boon, E.K.; Kayombo, C.J.; Musamba, E.B.; Kashindye, A.M.; Shayo, P.F. Species Composition, Richness and Diversity in Miombo Woodland of Bereku Forest Reserve, Tanzania. Journal of Biodiversity 2011, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F.K.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J.; Vinya, R. Floristic Composition, Species Diversity and Carbon Storage in Charcoal and Agriculture Fallows and Management Implications in Miombo Woodlands of Zambia. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 304, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montfort, F.; Nourtier, M.; Grinand, C.; Maneau, S.; Mercier, C.; Roelens, J.-B.; Blanc, L. Regeneration Capacities of Woody Species Biodiversity and Soil Properties in Miombo Woodland after Slash-and-Burn Agriculture in Mozambique. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 488, 119039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjate, M.J.; Massuque, J.Z. Composição Florística e Estrutura Da Vegetação Da Savana de Miombo Em Dois Ambientes Distintos No Distrito de Sanga, Norte de Moçambique. RICA 2019, 10, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukumary, S.D.; Proces, P.; Dubiez, E.; Marien, J.-N.; Peltier, R.; Bellefontaine, R. Caractérisation partielle de la régénération naturelle d’Albizia adianthifolia sur le plateau Batéké (République Démocratique du Congo). VertigO - la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, A.; Aroui, A.; Defaa, C.; El Mousadik, A.; Msanda, F. Effet de La Mise En Défens Sur La Richesse Floristique et La Densité Dans Deux Arganeraies de Plaine. Actes du Premier Congrès International de l’ Arganier 2011, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Clovis, K.O.; Louis, Z.; Claude, G.; Valery, N.N.; Bernard-Aloys, N. Diversité Floristique Et Structurale De Deux Forêts Communautaires Sous Exploitation Au Cameroun: Cas De Kompia Et Nkolenyeng. ESJ 2018, 14, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, K.S.; Dee, L.E.; Miller, S.J.; Bogan, M.T.; Lytle, D.A.; Gitelman, A.I. Linking Multidimensional Functional Diversity to Quantitative Methods: A Graphical Hypothesis--Evaluation Framework. Ecology 2016, 97, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaporte, A. Vers une compréhension fonctionnelle des dépérissements forestiers : étude du cas du hêtre (Fagus sylvatica L.) en forêt de Fontainebleau. Thèse de Doctorat, Ecologie, Environnement. Université Paris Sud - Paris XI: France, 2015.

- Hawes, J.E.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Magnago, L.F.S.; Berenguer, E.; Ferreira, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Cardoso, A.; Lees, A.C.; Lennox, G.D.; Tobias, J.A.; et al. A Large-Scale Assessment of Plant Dispersal Mode and Seed Traits across Human-Modified Amazonian Forests. Journal of Ecology 2020, 108, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, T.H.; Zackrisson, O.; Gundale, M.J.; Nilsson, M.-C. Ecosystem Feedbacks and Nitrogen Fixation in Boreal Forests. Science 2008, 320, 1181–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamidis, G.C.; Kazakou, E.; Fyllas, N.M.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. Species Adaptive Strategies and Leaf Economic Relationships across Serpentine and Non-Serpentine Habitats on Lesbos, Eastern Mediterranean. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulusu, M.; Martius, C.; Clendenning, J. Carbon Stocks in Miombo Woodlands: Evidence from over 50 Years. Forests 2021, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, A. De la « Fortress Conservation » aux nouveaux modèles de gestion participative de la biodiversité en Tanzanie. vertigo 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borokini, T.I.; Babalola, F.D.; Amusa, T.O.; Ivande, S.T.; Wala, Z.J.; Jegede, O.O.; Tanko, D.; Ihuma, J.O. Community-Based Forest Resources Management in Nigeria: Case Study of Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve, Mambilla Plateau, Taraba State, Nigeria. JTFE 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaivoarisoa, H.F.; Ramananarivo, S.; Ramananarivo, R.; Aubert, S. L’agriculture Durable, Element de Strategie Pour Le Developpement Rural Communal Cas De La Commune d’Ampitatafika- District d’Antanifotsy- Region Du Vakinankaratra.; ISDA: Montpellier, France, June 28 2010; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- N’tambwe, N.D.; Khoji, M.H.; Kasongo, B.W.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of Miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests 2023, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katani, J.Z.; Madoffe, S.S.; Amanzi, N.S.; Rija, A.A.; Midtgaard, F.; Mbeyale, G.; Zahabu, E.; Tarimo, B.C. Assessment of Fire Prevalence and Reduction Strategies in Miombo Woodlands of Eastern Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Forestry and Nature Conservation 2014, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Ndong, S.N.; Mouloungi, A.G.K.; Ze, S.O. Gouvernance des forêts et enjeux de création des parcs nationaux au Gabon : cas du parc national de la Lopé. Revue forestière française 2019, 71, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Villages | GC | H | DL | DFL | RC | MA | ADF | ADI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lwisha | 11°10’ S ; 27°01’ E | 2760 | MD | 86 km | VG | 1, 2, 3, 4 | X | |

| Maksem | 11°19’ S ; 27°50’ E | 356 | HD | 72 km | VG | 1, 2, 3 | X | X |

| Mwawa | 12°03’ S ; 27°35’ E | 115 | MD | 60 km | G | 1, 2, 3 | X | X |

| Nsela | 11°20’ S ; 27°36’ E | 129 | HD | 30 km | LG | 1, 2, 3, 4 | X | |

| Texas | 11°39’ S ; 27°46’ E | 179 | HD | 30 km | LG | 1, 2, 3 | X | |

| Mikembo | 11°28’ S ; 27°40’ E | 0 | SD | 30 km | VG | - | - | X |

| N° | Degradation factor | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Logging | Presence of tree stumps or trunks with resprouts, signs of charcoal production activities, including the presence of kilns. |

| 2 | Agriculture | Presence of cultivated fields or fallow land. |

| 3 | Vegetation fires | Observation of blackened marks on trees or charred trunks. |

| 4 | Debarking | Presence of bark harvesting marks on a tree trunk. |

| 5 | Invasion of exotic species | Inventory of exotic species, including Eucalyptus sp., Pinus sp., Acacia sp., and others. |

| 6 | Artisanal mining activities | Presence of small-scale mining sites and artisanal miner camps |

| Degradation factor | Presence-Absence (%) |

|---|---|

| Logging | 90,00 |

| Fires | 90,00 |

| Agriculture | 83,75 |

| Invasion of exotic species | 37,50 |

| Debarking | 21,25 |

| Artisanal mining activities | 5,00 |

| Logging | Fires | Agriculture | IES | Debarking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fires | 69,27*** | - | - | - | - |

| Agriculture | 39,22*** | 39,22*** | - | - | - |

| IES | 0,15 NS | 0,14 NS | 0,15 NS | - | - |

| Debarking | 1,19 NS | 1,19 NS | 0,84 NS | 0,04 NS | - |

| AMA | 0,05 NS | 0,04 NS | 0,04 NS | 1,12 NS | 0,19 NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).