Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

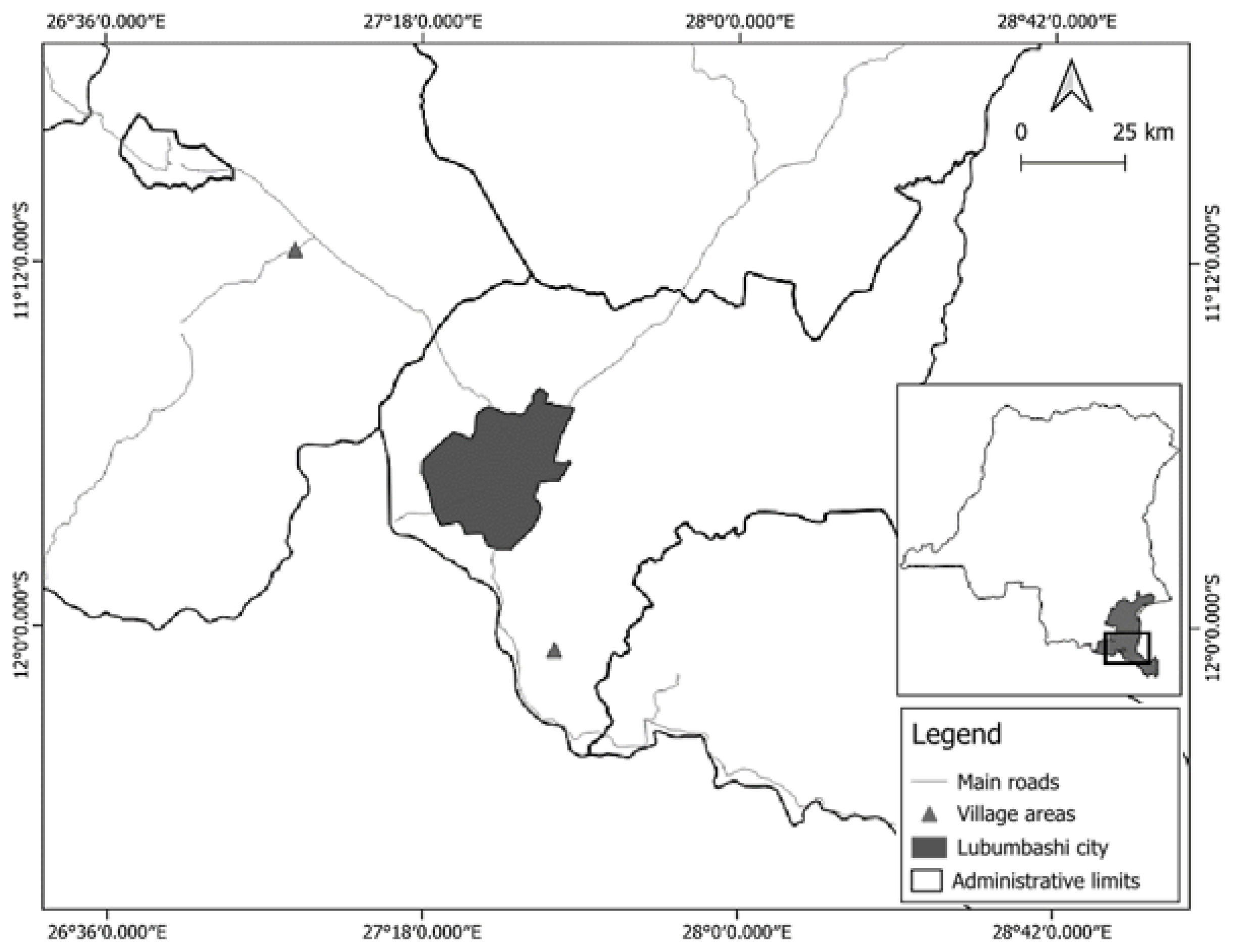

2.1. Study Environment

2.1. Methods

2.2.1. Village Areas Selection and Sampling

2.2.2. Data collection

2.2.3. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Habitats and Species Selection Criteria for Reforestation and Management of Reforested Habitats

3.1.1. Choice of Habitats for Reforestation in Village Areas

3.1.2. Choice of Woody Species for Reforestation in Village Areas

3.1.3. Management Practices on Reforested Habitats Within Village Areas

3.2. Forest Recovery in Reforested Habitats Compared to Unexploited Miombo in Both Village Areas

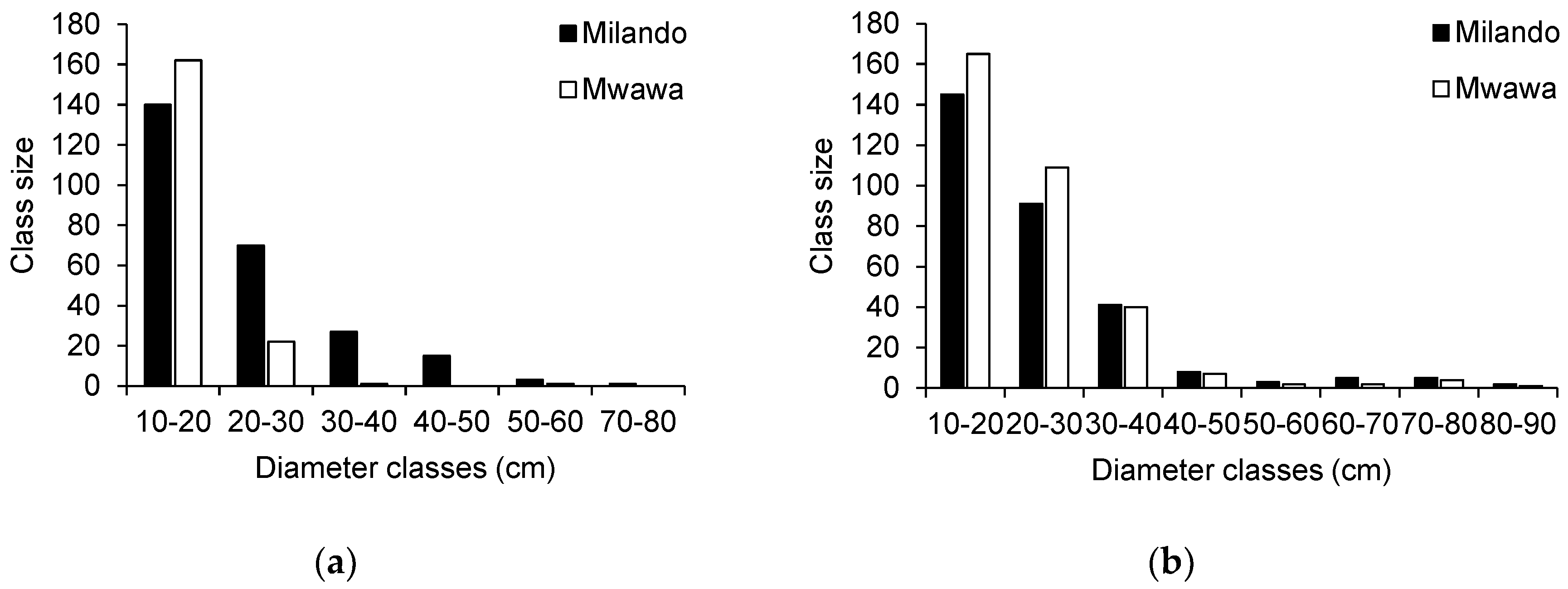

3.2.1. Diameter Structure of Individuals Inventoried in Reforested and Unexploited Habitats Within Village Areas

3.2.2. Density per Hectare and Ecological Importance of Woody Species Inventoried within Reforested and Unexploited Habitats in Both Village Areas

3.2.3. Dendrometric and floristic parameters of woody individuals inventoried within reforested and unexploited habitats in both village areas

3.2.4. Floristic Diversity Indices of Reforested and Unexploited Habitats in Both Village Areas

3.3. Similarities Between Ethnobotanical and Floristic Lists of Habitats in Both Village Areas

4. Discussion

4.1. Involvement of Local Communities in Decision-Making on Reforestation in Both Village Areas

4.2. Reconstitution of Forest Cover Within Reforested Habitats in Both Village Areas

4.3. Similarity Between Ethnobotanical and Floristic Lists of Reforested and Unexploited Habitats in Both village Areas

4.4. Implications of Results for Optimized Management of Reforested Habitats in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tchekoté, H.; Meva’a Nleme, Z.L.; Moudingo J.H.; Djofang, N.P. Diagnostic de la conservation pour une gestion durable de la biodiversité dans le Bakossi, Banyang-Mbo, Régions du Sud-Ouest et du Littoral au Cameroun. Rev. Sci. Tech. For. Environ. Bassin Congo 2020, 5, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F.K.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J.; Vinya, R. Floristic composition, species diversity and carbon storage in charcoal and agriculture fallows and management implications in Miombo woodlands of Zambia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 304, 99–109. [CrossRef]

- Eba’a Atyi, R.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Lescuyer, G.; Mayaux, P.; Defourny, P.; Bayol, N.; Saracco, F.; Pokem, D.; Sufo Kankeu, R.; Nasi, R. Les forêts du bassin du Congo : état des forêts 2021. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonésie, 2022; 474p. [CrossRef]

- FAO. La Situation des forêts du monde 2024 – Innovations dans le secteur forestier pour un avenir plus durable. FAO, Rome, Italie, 2024; 132p. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.M.P.; Chisingui, A.V.; Luís, J.C.; Rafael, M.F.F.; Tchamba, J.J.; Cachissapa, M.J.; Caluvino, I.M.C.; Bambi, B.R.; Alexandre, J.L.M.; Chissingui, M.D.G.; Manuel, S.K.A.; Jacinto, H.D.; Finckh, M.; Meller, P.; Jürgens, N.; Revermann, R. First vegetation-plot database of woody species from Huíla province, SW Angola. Veg. Classif. Surv. 2021, 2, 109–116. [CrossRef]

- Bostancı, S.H. The Role of Local Governments in Encouraging Participation in Reforestation Activities. In: Singh, P.; Milshina, Y.; Batalhão, A.; Sharma, S.; Mohd, M.H. (eds.), The Route Towards Global Sustainability. Springer nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2023; 25–44. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B. M.; Frost, P.; Byron, N. Miombo Woodlands and their use: overview and key issues. In: Campbell, B. (eds.), The Miombo in Transition: Woodlands and Welfare in Africa. Centre for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia, 2006; 1–10.

- Berrahmouni, N.; Regato, P.; Parfondry, M. Global guidelines for the restoration of degraded forests and landscapes in drylands: building resilience and benefiting livelihoods. FAO, Rome, Italie, 2015; 173 p.

- Malaisse, F. How to live and survive in Zambezian open forest (Miombo ecoregion). Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2010; 424 p.

- Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Boisson, S.; Useni, S.Y. La végétation naturelle d’Élisabethville (actuellement Lubumbashi) au début et au milieu du XXième siècle. Géo-Eco-Trop. 2021, 45(1), 41–51.

- Sawe, T.; Munishi, P.; Maliondo, S. Woodlands degradation in the Southern Highlands, Miombo of Tanzania: Implications on conservation and carbon stocks. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 6, 230–237.

- Mwitwa, J.; German, L.; Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Puntondewo, A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscape shaped by mining: mining forestry linkages and impacts in the copper belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 25, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.M.P.; Revermann, R.; Cachissapa, M.J.; Gomes, A.L.; Aidar, M.P.M. Species diversity, population structure and regeneration of woody species in fallows and mature stands of tropical woodlands of southeast Angola. J. For. Res. 2018, 29, 1569–1579. [CrossRef]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Brooks, T.M.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Konstant, W.R.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kormos, C. Wilderness and biodiversity conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A, 2003, 100, 10309–10313. [CrossRef]

- Godlee, J.L.; Gonçalves, F.M.; Tchamba, J.J.; Chisingui, A.V.; Ilunga, M.J.; Ngoy, S.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Brade, T.K.; Dexter, K.G. Diversity and Structure of an Arid Woodland in Southwest Angola, with Comparison to the Wider Miombo Ecoregion. Diversity 2020, 12, 140. [CrossRef]

- Munyemba, K. F.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et dynamique spatiotemporelle de l’occupation du sol dans la région de Lubumbashi entre 1956 et 2009. E-revue Unilu 2014, 1, 3–23.

- Mojeremane, W.; Lumbile, A. A review of Pterocarpus angolensis DC. (Mukwa) an important and threatened timber species of the Miombo woodlands. Res. J. For. 2016, 10, 8–14.

- Khoji, M.H.; N’tambwe, N.D.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Cabala, K.S..; Munyemba, K.F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [CrossRef]

- Cabala, K.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bogaert, J. Activités anthropiques et dynamique spatiotemporelle de la forêt claire dans la Plaine de Lubumbashi. In: Bogaert, J., Colinet, G. & Mahy, G. (Eds), Anthropisation des paysages katangais. Les Presses Universitaires de Liège, Liège, Belgique, 2018; 253-266.

- Khoji, M.H.; N’tambwe, N.D.; Mwamba, K.F.; Harold, S.; Munyemba, K.F.; Malaisse, F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Useni, S.Y.; Bogaert, J. Mapping and Quantification of Miombo Deforestation in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo): Spatial Extent and Changes between 1990 and 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1852. [CrossRef]

- Syampungani, S.; Geldenhuys, C.J.; Chirwa, P.W. Regeneration dynamics of miombo woodland in response to different anthropogenic disturbances: forest characterisation for sustainable management. Agrofor. Syst. 2016, 90, 563–576. [CrossRef]

- Mpanda, M.M.; Khoji, M.H.; N’Tambwe, N.D.; Sambieni, R.K.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala, K.S.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11, 1541. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Cirezi Cizungu, N.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Vegetation Fires in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (The Democratic Republic of the Congo): Drivers, Extent and Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Land 2023, 12, 2171. [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, P.W.; Larwanou, M.; Syampungani, S.; Babalola, F.D. Management and restoration practices in degraded landscapes of Southern Africa and requirements for up-scaling. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.V.; Turubanova, S.A.; Hansen, M.C.; Adusei, B.; Broich, M.; Altstatt, A.; Mane, L.; Justice, C.O. Quantifying forest cover loss in Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2000–2010, with Landsat ETM+ data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 106–116. [CrossRef]

- Cadre Intégré de Classification de la sécurité Alimentaire. Analyse de l’IPC de l’insécurité alimentaire chronique. IPC-Kinshasa, Kinshasa, République démocratique du Congo, 2024 ; 120p.

- N’tambwe, D.N.; Khoji, M.H.; Kasongo, K.B.; Kouagou, S.R.; Malaisse, F.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests 2023, 14, 687. [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, T.; Muller, A.; Morris, M. Manuel La Régénération Naturelle Assistée (RNA). Une ressource pour les gestionnaires de projets, les utilisateurs et tous ceux qui ont un intérêt à mieux comprendre et soutenir le mouvement pour la RNA. FMNR Hub, World Vision, Melbourne, Australia, 2020; 241p.

- Awono, A.; Assembe-Mvondo, S.; Tsanga, R.; Guizol, P.; Peroches, A. Restauration des paysages forestiers et régimes fonciers au Cameroun : Acquis et handicaps. Document Occasionnel 10. CIFOR-ICRAF, Bogor, Indonésie, 2023; 43p. [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D.; Aide, T.M. When and where to actively restore ecosystems? For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1558–1563. [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Guariguata, M.R. Natural regeneration as a tool for large-scale forest restoration in the tropics: prospects and challenges, Biotropica 2016, 48(6), 716–730. [CrossRef]

- Reyniers, C. Agroforesterie et déforestation en République démocratique du Congo. Miracle ou mirage environnemental ? Monde dev. 2019, 187, 113–132. [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe, N.D.; Khoji, M.H.; Salomon, W.; Cuma, M.F.; Malaisse, F.; Ponette, Q.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Floristic Diversity and Natural Regeneration of Miombo Woodlands in the Rural Area of Lubumbashi, D.R. Congo. Diversity 2024, 16, 405. [CrossRef]

- Buttoud, G.; Nguinguiri J.C., 2016. La gestion inclusive des forêts d’Afrique centrale : passer de la participation au partage des pouvoirs. FAO-CIFOR, Bogor, Indonésie, 2016; 250p.

- Hervé, D.; Randriambanona, H.; Ravonjimalala, H. R.; Ramanankierana, H.; Rasoanaivo, N. S.; Baohanta, R.; Carrière, S. M. Perceptions des fragments forestiers par les habitants des forêts tropicales humides malgaches. Bois For. Trop. 2020, 345, 43–62. [CrossRef]

- Nansikombi, H.; Fischer, R.; Kabwe, G.; Günter, S. Exploring patterns of forest governance quality: Insights from forest frontier communities in Zambia’s Miombo ecoregion. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Asaah, E.K.; Tchoundjeu, Z.; Leakey, R.R.B.; Takousting, B.; Njong, J.; Edang, I. Trees, agroforestry and multifunctional agriculture in Cameroon. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2011, 9:110–119. [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B.; Sanou, L.; Koala, J.; Hien M. Perceptions locales de la dégradation des ressources naturelles du corridor forestier de la Boucle du Mouhoun au Burkina Faso. Bois For. Trop. 2022, 352, 43–60. [CrossRef]

- Baïyabe, I.-M.; Dongock, N.D.; Amougoua, A.C.; Tchobsala; Mapongmetsem, P.M. Perceptions paysannes des sites reboisés de la région de l’extrême-nord, cameroun. Rev. ivoir. sci. technol. 2023, 42, 114–131.

- Diawara, S.; Dao, A.; Ouattara, M.; Savadogo, P. Evaluation des connaissances locales dans la restauration écologique des paysages forestiers dégradés au Burkina Faso. Sci. Nat. Appl. 2024, 43(1), 180–205.

- Landry, J.; Chirwa, PW. Analysis of the potential socioeconomic impact of establishing plantation forestry on rural communities in Sanga district, Niassa province, Mozambique. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 542–551. [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, E.P.; Grady, K.C. Symphony for the native wood(s): Global reforestation as an opportunity to develop a culture of conservation. People Nat. 2022, 4, 576–587. [CrossRef]

- Montfort, F. Dynamiques des paysages forestiers au Mozambique : étude de l’écologie du Miombo pour contribuer aux stratégies de restauration des terres dégradées. Bois For. Trop. 2023, 357, 105–106. [CrossRef]

- Bisiaux, F.; Peltier, R.; Muliele, J.-C. Plantations industrielles et agroforesterie au service des populations des plateaux Batéké, Mampu, en République Démocratique du Congo. Bois For. Trop. 2009, 301(3), 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Muchiza, B.I.; Monga, I.D.R.; Mumba, T.U.; Ndabereye, S. M.D.A.; Kalombo, W.K.C.; Nono, M.N. Perceptions des populations locales sur la forêt, la déforestation et leur participation à la gestion forestière du Miombo dans l’hinterland de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga/RDC). Rev. Afr. Environ. Agric. 2022, 5(4), 108–115.

- Numbi, M.D.; Mbinga, L.B.; Mpange, K.F.; Mukendi, E.; Kazaba, K.P.; Nzuzi, M.G.; Kapend, K.D.L.V.; Kaya, B.H.H.; Lwamba, B.J.; Monga, I.D.R.; Ngoy, S.M. Influence de traitements sur la germination et la croissance en pépinière d’Afzelia quanzensis Welw. (Fabaceae) à Lubumbashi en République Démocratique du Congo. Rev. Afr. Environ. Agric. 2024, 7(1), 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Khoji, M.H.; Mpanda, M.M.; Kipili, M.I.; Malaisse, F.; N’tambwe, N.D.; Kasanda, M.N.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni, S.Y. Protected area creation and its limited effect on deforestation: Insights from the Kiziba-Baluba hunting domain (DR Congo). Trees, Forests and People 2024, 18, 100654. [CrossRef]

- Kalombo, K. D. Evolution des éléments du climat en RDC : Stratégies d'adaptation des communautés de base, face aux événements climatiques de plus en plus fréquents. Éditions universitaires européennes, Sarrebruck, Allemagne, 2016; 220p.

- Kasongo, L.M.E.; Banza, M.J. Evaluation de la réponse du soja aux doses croissantes d’un compost à base de Tithonia diversifolia sur un sol fortement altéré. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2015, 11(2), 273–281.

- Johnston, L.G.; Sabin, K. Échantillonnage déterminé selon les répondants pour les populations difficiles à joindre. Methodol. Innovations 2010, 5(2), 38–48. [CrossRef]

- Marpsat, M.; Razafindratsima, N. Les méthodes d’enquêtes auprès des populations difficiles à joindre : Introduction au numéro spécial. Methodol. Innovations 2010, 5(2), 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Traoré, L.; Hien, M.; Ouédraogo, I. Usages, disponibilité et stratégies endogènes de préservation de Canarium schweinfurthii (Engl.) (Burseraceae) dans la région des Cascades (Burkina Faso). Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2021, 21(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, É.; Michaux, E. Étalonnages à l’aide d’enquêtes de conjoncture : de nouveaux résultats. Econ. Prévis. 2006, 172 : 11-28. [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, P.; Boston, K.; Siry, P.J.; Grebner, L.D. Forest Management and Planning. Academic press, 2nd ed, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2016; 362p.

- Smith, P.; Allen, Q. Field guide to the trees and shrubs of the miombo woodlands. Royal Botanic Gardens, Brussels, Belgium, 2004; 176p.

- Meerts, P.J.; Hasson, M. Arbres et Arbustes du Haut-Katanga. Editions Jardin Botanique de Meise, Brussels, Belgium, 2016; 386p.

- Vollesen, K.; Merrett, L. A photo rich field guide to the (wetter) Zambian Miombo woodland: Based on Plants from the Mutinondo Wilderness Area, Northern Zambia. Lari Merret, Lusaka, Zambia, 2020; 1200p.

- Thiombiano, A.; Glele kakaï, R.; Bayen, P.; Boussim, J.I.; Mahamane, A. Méthodes et dispositifs d’inventaires forestiers en Afrique de l’Ouest : état des lieux et propositions pour une harmonisation. Ann. Sci. Agron. 2016, 20, 15–31.

- Ameja, L.G.; Ribeiro, N.S.; Sitoe, A.; Guillot, B. Regeneration and Restoration Status of Miombo Woodland Following Land Use Land Cover Changes at the Buffer Zone of Gile National Park’s Central Mozambique. Trees, Forests and People 2022, 9, 100290. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zang, R.; Lu, X.; Huang, J. The impacts of selective logging and clear-cutting on woody plant diversity after 40 years of natural recovery in a tropical montane rain forest, south China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1683–1691. [CrossRef]

- Rondeux, J. La mesure des arbres et des peuplements forestiers. 3ème édition. Les Presses Universitaires de Liège – Agronomie – Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2021; 738p. http://hdl.handle.net/2268/262622.

- Badjaré, B.; Kokou, K.; Bigou-lare, N.; Koumantiga, D.; Akpakouma, A.; Adjayi, M.B.; Abbey, G.A. Etude ethnobotanique d’espèces ligneuses des savanes sèches au Nord-Togo, diversité, usages, importance et vulnérabilité. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2018, 22(3), 152–171.

- Amba, G.J.A.; Gnahoré, É.; Diomandé, S. Diversité floristique et structurale de la forêt classée de la Mabi au Sud-Est de la Côte d’Ivoire. Afr. Sci. 2021, 18(1), 159–171.

- Zébazé, D.; Gorel, A.; Gillet, J.-F.; Houngbégnon, F.; Barbier, N.; Ligot, G.; Lhoest, S.; Kamdem, G.; Libalah, M.; Droissart, V.; Sonké, B.; Doucet, J.-L. Natural regeneration in tropical forests along a disturbance gradient in South-East Cameroon. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 547, 121402. [CrossRef]

- Ostertagová, E.; Ostertag, O.; Kováč, J. Methodology and Application of the Kruskal-Wallis Test. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 611, 115–120. [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.M.; Wah, Y.B. Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. J. Stat. Model. Anal. 2011, 2(1), 21-33.

- Gupta, B.; Mishra, T.K. Analysis of tree diversity and factors affecting natural regeneration in fragmented dry deciduous forests of lateritic West Bengal. Trop. Ecol. 2019, 60, 405–414. [CrossRef]

- Heinken, T.; Diekmann, M.; Liira, J.; Orczewska, A.; Schmidt, M.; Brunet, J.; Chytrý, M.; Chabrerie, O.; Decocq, G.; De Frenne, P.; Dřevojan, P.; Dzwonko, Z.; Ewald, J.; Feilberg, J.; Graae, B.J.; Grytnes, J.; Hermy, M.; Kriebitzsch, W.; Laiviņš, M.; Lenoir, J.; Lindmo, S.; Marage, D.; Marozas, V.; Niemeyer, T.; Paal, J.; Pyšek, P.; Roosaluste, E.; Sádlo, J.; Schaminée, J.H.J.; Tyler, T.; Verheyen, K.; Wulf, M.; Vanneste, T. The European Forest Plant Species List (EuForPlant): Concept and applications. J. Veg. Sci. 2022, 33, e13132. [CrossRef]

- Albatineh, A.N.; Niewiadomska-Bugaj, M. Correcting Jaccard and other similarity indices for chance agreement in cluster analysis. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 2011, 5, 179–200. [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe, N.D.; Khoji, M.H.; Cabala, K.S.; Malaisse, F.; Amisi, M.Y.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Spatial Footprint of anthropogenic activities in the Charcoal Production Basin of Lubumbashi (D.R. Congo): Applicability of Kevin Lynch's (1960) approach. J. nat. conserv. (In press). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4743650.

- Aerts, R.; Honnay, O. Forest restoration, biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. BMC Ecol. 2011, 11, 29. [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.D.; Zipper, E.C.; Burger, A.J.; Strahm, D.B.; Villamagna, M.A. Reforestation practice for enhancement of ecosystem services on a compacted surface mine: Path toward ecosystem recovery. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 51, 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Yona Mleci, J.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. The Restoration of Degraded Landscapes along the Urban–Rural Gradient of Lubumbashi City (Democratic Republic of the Congo) by Acacia auriculiformis Plantations: Their Spatial Dynamics and Impact on Plant Diversity. Ecologies 2024, 5, 25–41. [CrossRef]

- Doren, R.F. ; Volin, J.C.; Richards, J.H. Invasive Exotic Plant Indicators for Ecosystem Restoration: An Example from the Everglades Restoration Program. Ecol. Indic. 2009, 9, 29–36.

- Useni, S.Y.; Mpibwe, K.A.; Yona, M.J.; N’Tambwe, N.D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Assessment of Street Tree Diversity, Structure and Protection in Planned and Unplanned Neighborhoods of Lubumbashi City (DR Congo). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3830. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Restauration du paysage forestier. Unasylva, Rome, Italie, 2015; 116p. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i5212f.

- Tiki, L.; Abdallah, J.M.; Marquardt, K.; Tolera, M. Does Participatory Forest Management Reduce Deforestation and Enhance Forest Cover? A Comparative Study of Selected Forest Sites in Adaba-Dodola, Ethiopia. Ecologies 2024, 5, 647–663. [CrossRef]

- Kimambo, N.E.; L’Roe, J.; Naughton-Treves, L.; Radeloff, V.C. The role of smallholder woodlots in global restoration pledges – Lessons from Tanzania. Forest Policy Econ. 2020, 115, 102144. [CrossRef]

- Giliba, R.A.; Mafuru, C.S.; Paul, M.; Kayombo, C.J.; Kashindye, A.M.; Chirenje, L.I.; Musamba, E.B. Human Activities Influencing Deforestation on Meru Catchment Forest Reserve, Tanzania. J. Hum. Ecol. 2011a, 33(1): 17–20. [CrossRef]

- Van Wilgen, B.W.; De Klerk, H.M.; Stellmes, M.; Archibald, S. An analysis of the recent fire regimes in the Angolan catchment of the Okavango Delta, Central Africa. Fire Ecol. 2022, 18, 13. [CrossRef]

- Buramuge, V.A.; Ribeiro, N.S.; Olsson, L.; Bandeira, R.R. Exploring Spatial Distributions of Land Use and Land Cover Change in Fire-Affected Areas of Miombo Woodlands of the Beira Corridor, Central Mozambique. Fire 2023a, 6, 77. [CrossRef]

- Buramuge, V.A.; Ribeiro, N.S.; Olsson, L.; Bandeira, R.R.; Lisboa, S.N. Tree Species Composition and Diversity in Fire-Affected Areas of Miombo Woodlands, Central Mozambique. Fire 2023b, 6, 26. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, A.I.R.; Vasconcelos, M.J.; Oom, D.; Sardinha, R. Spatial dynamics and quantification of deforestation in the central-plateau woodlands of Angola (1990–2009). Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1185–1193. [CrossRef]

- Barbara, N.; Linda, N.; Ngonga, C. Drivers of Deforestation in the Miombo Woodlands and Their Impacts on the Environment. Adv. Res. 2016, 6(5), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Cabala, K.S.; Useni, S.Y.; Amisi, M.Y.A.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bogaert, J. Activités anthropiques et dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers dans les zones territoriales de l’Arc Cuprifère Katangais (RD Congo). Tropicultura 2022, 40(3/4), 210. [CrossRef]

- Kabanyegeye, H.; Useni, S.Y.; Sambieni, K.R.; Masharabu, T.; Havyarimana, F.; Bogaert, J. Trente-trois ans de dynamique spatiale de l’occupation du sol de la ville de Bujumbura, République du Burundi. Afrique Sci. 2021, 18, 203–2015. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/256070.

- Giliba, R. A.; Boon, E. K.; Kayombo, C. J.; Musamba, E. B.; Kashindye, A. M.; Shayo, P. F. Species composition, richness and diversity in Miombo woodland of Bereku Forest Reserve, Tanzania. J. Biodivers. 2011b, 2(1), 1–7.

- Chirwa, W.P.; Mahamane, L. Overview of restoration and management practices in the degraded landscapes of the Sahelian and dryland forests and woodlands of East and southern Africa, Southern Forests. J. For. Sci. 2017, 17(3), 20-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.2989/20702620.2016.1255419.

- Vinya, R.; Syampungani, S.; Kasumu, E.C.; Monde, C.; Kasubika, R. Preliminary study on the drivers of deforestation and potential for REDD+ in Zambia. A consultancy report prepared for Forestry Department and FAO under the national UN-REDD+ Programme Ministry of Lands & Natural Resources. Lusaka, Zambia, 2011; 65p.

- Masharabu, T.; Noret, N.; Lejoly, J.; Bigendako, M-J.; Bogaert, J. Etude comparative des paramètres floristiques du Parc National de la Ruvubu, Burundi. Géo-Eco-Trop. 2010, 34, 29 – 44.

- Gonçalves, F.M.P.; Revermann, R.; Gomes, A.L.; Aidar, M.P.M.; Finckh, M.; Juergens, N. Tree Species Diversity and Composition of Miombo Woodlands in South-Central Angola: A Chronosequence of Forest Recovery after Shifting Cultivation. Int. J. For. Res. 2017, 2017, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Montfort, F.; Nourtier, M.; Grinand, C.; Maneau, S.; Mercier, C.; Roelens, J.-B.; Blanc, L. Regeneration capacities of woody species biodiversity and soil properties in Miombo woodland after slash-and-burn agriculture in Mozambique. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 488, 119039. [CrossRef]

- Kissanga, R.; Catarino, L.; Máguas, C.; Cabral, A.I.R.; Chozas, S. Assessing the Impact of Charcoal Production on Southern Angolan Miombo and Mopane Woodlands. Forests 2023, 15, 78. [CrossRef]

- Kaumbu, J.M.K.; Mpundu, M.M.M.; Kasongo, E.L.M.; Ngoy Shutcha, M.; Tekeu, H.; Kalambulwa A.N.; Khasa, D. Early Selection of Tree Species for Regeneration in Degraded Woodland of Southeastern Congo Basin. Forests 2021, 12, 117. [CrossRef]

- Tonga, K.P.; Zapfack, L.; Kabelong B.L.P.R.; Endamana, D. Disponibilité des produits forestiers non ligneux fondamentaux à la périphérie du Parc national de Lobeke. Vertigo 2017, 17(3), consulté le 20 octobre 2024. [CrossRef]

- Caro, TM.; Sungula, M.; Schwartz, M.W.; Bella, EM. Recruitment of Pterocarpus angolensis in the wild. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 219, 169–175.

- Alemagi, D. ; Hajjar, R. ; Tchoundjeu, Z.; Kozak, R.A. Cameroon’s environmental impact assessment decree and public participation in concession-based forestry: An exploratory assessment of eight forest-dependent communities. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6(10), 8–24.

- Fobissie, K.; Chia, E.; Enongene, K., 2017. Mise en œuvre de la REDD+, du MDP et de la CDN du secteur AFAT en Afrique francophone. Forum For. Afr. 2017, 3(7), 61p.

- Wily, L.A. Vers une gestion démocratique des forêts en Afrique orientale et australe. International Institute for Environment and Development, Programme zones arides. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Londres, au Royaume-Uni, 2000; 27p.

- Kiyulu, J.; Mpoyi, M.A. Mécanismes d’amélioration de la gouvernance forestière en République Démocratique du Congo : Rapport national d’études juridiques et socio-économiques. UE, IUCN, Kinshasa, RDC, 2007; 88p.

- Ibanda, K.P. La réforme forestière de 2002 en République démocratique du Congo. Essai d’évaluation de ses conséquences juridiques, fiscales, écologiques et socio-économiques. L'Harmattan, Paris, France, 2019; 22p.

- Etrillard, C. Paiements pour services environnementaux : nouveaux instruments de politique publique environnementale. Dev. Durab. Territ. 2016, 7(1), 1–8. Consulté le 15 février 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lescuyer, G.; Karsenty, A.; Eba'a Atyi, R. Un nouvel outil de gestion durable des forêts d'Afrique Centrale : les paiements pour services environnementaux. In : De Wasseige, C.; Devers, D.; De Marcken, P.; Eba'a Atyi, R.; Nasi, R.; Mayaux, P. (Eds.), Les forêts du bassin du Congo : état des forêts 2008. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2009; 143-155.

- Dewees, P.A.; Campbell, B.M.; Katerere, Y.; Sitoe, A.; Cunningham, A.B.; Angelsen, A.; Wunder, S. Managing the miombo woodlands of southern Africa: policies, incentives and options for the rural poor. J. nat. resour. policy res. 2010, 2(1), 57–73.

- Martin, A.; Akol, A.; Phillips, J. Just conservation? On the fairness of sharing benefits. In: Sikor, T.; Fisher, J.; Few, R.; Martin, A.; Zeitoun, M. (Eds), The justices and injustices of ecosystem services. 1st éd, Routledge, London, UK, 2013; 69-91. [CrossRef]

| Selection criteria | Reforested habitats (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Milando (n=50) | Mwawa (n=50) | |

| Choice of the village chief | 48.00 | 24.00 |

| Choice of the village chief and NGO | 6.00 | 4.00 |

| Choice of the village chief and notables | 14.00 | 12.00 |

| Consultation | 22.00 | 44.00 |

| Selection criteria | Reforested habitats (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Milando (n=50) | Mwawa (n=50) | |

| Timber | - | 4.00 |

| Village chief and notables | - | 6.00 |

| Choice of NGO | 16.00 | 16.00 |

| Seed availability | 44.00 | 18.00 |

| NTFP sources | 40.00 | 52.00 |

| Soil type | - | 4.00 |

| Management practices | Reforested habitats (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Milando (n=50) | Mwawa (n=50) | |

| Firebreaks | 38.00 | 46.00 |

| Plant nursery | - | 4.00 |

| Planning/assessment meetings | 38.00 | 26.00 |

| Surveillance (Brigade) | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| Species | Families | Density/ha | IVI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milando | Mwawa | Milando | Mwawa | ||||||

| Re | Un | Re | Un | Re | Un | Re | Un | ||

| Acacia polyacantha Willd. | Fabaceae | -+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Afzelia quanzensis Welw. | Fabaceae | -+ | - | -+ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Albizia adianthifolia (Schumach.) W. F. Wight | Fabaceae | -* | 6 | 37 | 14 | - | 8.36 | 55.73 | 15.24 |

| Albizia antunesiana Harms | Fabaceae | 20* | 8 | 6* | 9 | 24.37 | 10.77 | 10.82 | 8.78 |

| Albizia versicolor Welw. ex Oliv. | Fabaceae | - | 1 | 7 | 1 | - | 1.39 | 12.50 | 1.29 |

| Anisophyllea boehmii Engl. | Anisophylleaceae | -* | 4 | -* | 1 | - | 4.81 | - | 1.40 |

| Baphia bequaertii De Wild. | Fabaceae | - | 11 | 7 | 12 | - | 11.67 | 10.13 | 10.80 |

| Bobgunnia madagascariensis (Desv.) J.H.Kirkbr. & Wiersema | Fabaceae | 8* | 2 | 5* | 4 | 9.88 | 2.85 | 11.91 | 3.51 |

| Brachystegia boehmii Taub. | Fabaceae | 5* | - | 10* | - | 13.70 | - | 13.36 | - |

| Brachystegia floribunda Benth. | Fabaceae | - | - | -+ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Brachystegia spiciformis Benth. | Fabaceae | 23* | 59 | 10* | 70 | 24.59 | 42.38 | 15.94 | 49.86 |

| Brachystegia wangermeeana De Wild. | Fabaceae | 24 | 98 | 15 | 108 | 31.99 | 69.52 | 20.54 | 68.83 |

| Combretum collinum Fresen. | Combretaceae | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1.94 | - | 1.88 |

| Combretum molle R.Br ex G. Don | Combretaceae | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 1.96 | - | 3.41 |

| Combretum zeyheri Sond. | Combretaceae | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2.03 | - |

| Dalbergia boehmii Taub. | Fabaceae | 2 | - | - | - | 3.51 | - | - | - |

| Diplorhynchus condylocarpon (Müll. Arg.) Pichon | Apocynaceae | 15* | 8 | 21 | 8 | 16.72 | 9.26 | 29.01 | 8.77 |

| Ekebergia benguelensis Welw. ex C.DC. | Meliaceae | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.43 | - | - |

| Erythrina abyssinica (Hochst.) A. Rich. | Fabaceae | 4 | - | 12 | - | 5.80 | - | 27.58 | - |

| Erythrophleum africanum (Welw. ex Benth.) Harms | Fabaceae | - | 4 | - | 3 | - | 5.20 | - | 4.01 |

| Faurea rochetiana (A.Rich.) Chiov. ex Pic. Serm. | Proteaceae | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.89 | - |

| Ficus sp | Moraceae | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.97 | - |

| Isoberlinia angolensis (Benth.) Hoyle & Brenan | Fabaceae | 20* | 7 | 19* | 12 | 22.81 | 8.89 | 24.26 | 13.34 |

| Julbernardia globiflora (Benth.) Troupin | Fabaceae | 4 | - | 1 | - | 6.88 | - | 1.97 | - |

| Julbernardia paniculata (Benth.) Troupin | Fabaceae | 12* | 5 | 4* | 2 | 12.94 | 6.33 | 7.04 | 1.93 |

| Lannea discolor (Sond.) Engl. | Anacardiaceae | 2 | 4 | - | 4 | 3.04 | 3.70 | - | 3.46 |

| Maranthes floribunda (Baker) F.White | Chrysobalanaceae | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.87 | - |

| Markhamia obtusifolia (Boulanger) Sprague | Bignoniaceae | - | 3 | - | 3 | - | 10.34 | - | 10.72 |

| Marquesia macroura Gilg | Dipterocaerpaceae | -* | 18 | 1* | 8 | - | 32.40 | 1.88 | 17.00 |

| Monotes africanus Gilg | Dipterocaerpaceae | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4.90 | 2.10 | 2.67 | 2.06 |

| Monotes katangensis De Wild. | Dipterocaerpaceae | 7 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 8.34 | 8.41 | 4.69 | 4.64 |

| Mystroxylon aethiopicum (Thunb.) Lœs. | Celastraceae | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2.04 | - | 1.99 |

| Ochna schweinfurthiana F.Hoffm. | Ochnaceae | - | 2 | 4 | 6 | - | 2.73 | 7.98 | 6.69 |

| Olax obtusifolia De Wild. | Olacaceae | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.49 |

| Parinari curatellifolia Planch. ex Benth. | Chrysobalanaceae | 2* | 3 | 5* | 6 | 2.96 | 3.38 | 10.02 | 6.84 |

| Pericopsis angolensis (Harms) Van Meeuw. | Fabaceae | 29* | 7 | 2* | 5 | 32.44 | 8.12 | 2.83 | 6.87 |

| Philenoptera katangensis (De Wild.) Schrire | Fabaceae | 1 | - | - | - | 1.47 | - | - | - |

| Phyllocosmus lemaireanus (De Wild. & T. Durand) T. Durand & H. Durand | Ixonanthaceae | - | 1 | - | 4 | - | 1.60 | - | 3.63 |

| Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia Pax | Phyllanthaceae | 5 | 2 | - | 1 | 4.69 | 2.79 | - | 1.26 |

| Psorospermum febrifugum Spach | Hypericaceae | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.39 | - | - |

| Pterocarpus angolensis DC. | Fabaceae | 1* | 4 | 4* | 14 | 1.45 | 5.30 | 7.97 | 13.89 |

| Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. | Fabaceae | 3* | - | -* | - | 6.42 | - | - | - |

| Salacia rhodesiaca Blakelock | Celastraceae | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2.00 | - |

| Strychnos cocculoides Boulanger | Loganiaceae | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 3.69 | - | 1.67 |

| Strychnos innocua Del. subsp. innocua | Loganiaceae | 1 | - | - | - | 1.42 | - | - | - |

| Strychnos pungens Soler. | Loganiaceae | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1.64 | - | 1.56 |

| Strychnos sp | Loganiaceae | - | 2 | - | 2 | - | 3.17 | - | 2.95 |

| Strychnos spinosa Lam. | Loganiaceae | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1.50 | - | 1.41 |

| Syzygium guineense (Willd.) DC. subsp. Macrocarpum | Myrtaceae | -* | - | 2* | - | - | - | 4.27 | - |

| Uapaca kirkiana Müll. Arg. | Phyllanthaceae | 43* | 10 | 2* | 7 | 36.46 | 11.64 | 2.64 | 8.14 |

| Uapaca nitida Müll.Arg. | Phyllanthaceae | 15 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 15.05 | 5.91 | 2.43 | 5.38 |

| Uapaca pilosa Hutch. var. pilosa | Phyllanthaceae | 7 | - | 1 | - | 8.15 | - | 2.07 | - |

| Uapaca robynsii De Wild. | Phyllanthaceae | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | 1.39 | - | 3.90 |

| Vitex doniana Sweet | Lamiaceae | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1.39 |

| Parameters | Reforested habitats | Unexploited habitats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milando | Mwawa | Milando | Mwawa | |

| Dendrometric parameters | ||||

| Density (individuals/ha) | 256.00 ± 111.77ab | 186.00 ± 64.15b | 300.00 ± 97.18a | 330.00 ± 123.47a |

| Mean square diameter (cm) | 21.94 ± 3.11a | 14.97 ± 2.54b | 24.64 ± 4.71a | 22.73 ± 3.11a |

| Basal area (m2 /ha) | 11.52 ± 5.52a | 3.40 ± 1.17b | 17.23 ± 7.70a | 15.89 ± 6.72a |

| Floristic parameters | ||||

| Taxa/plot | 10.40 ± 3.10a | 9.10 ± 2.92a | 10.30 ± 3.43a | 11.20 ± 2.86a |

| Type/ plot | 8.30 ± 2.71a | 7.70 ± 2.71a | 8.30 ± 2.58a | 9.00 ± 2.11a |

| Families/ plot | 3.60 ± 1.43a | 3.90 ± 2.03a | 5.00 ± 2.21a | 5.10 ± 2.23a |

| Indices | Milando reforested | Milando unexploited |

Mwawa reforested | Mwawa unexploited |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson | 0.0834 | 0.1581 | 0.08689 | 0.1633 |

| Shannon | 2.731 | 2.531 | 2.809 | 2.503 |

| Piélou's equitability | 0.8593 | 0.712 | 0.8342 | 0.7039 |

| Milando reforested | Milando unexploited |

Mwawa reforested |

Milando ethnobotany |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milando unexploited | 40.00 | |||

| Mwawa reforested | 55.56 | - | ||

| Mwawa unexploited | - | 93.75 | 47.62 | |

| Milando ethnobotany | 43.75 | - | - | |

| Mwawa ethnobotany | - | - | 31.58 | 66.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).