Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Exploring the Definition of Forest

1.2. Deforestation and the Plurality of Interests Among Social Groups

1.3. Influence of Perceptions of Forest Conservation on Resource Management

2. Materials and Methods

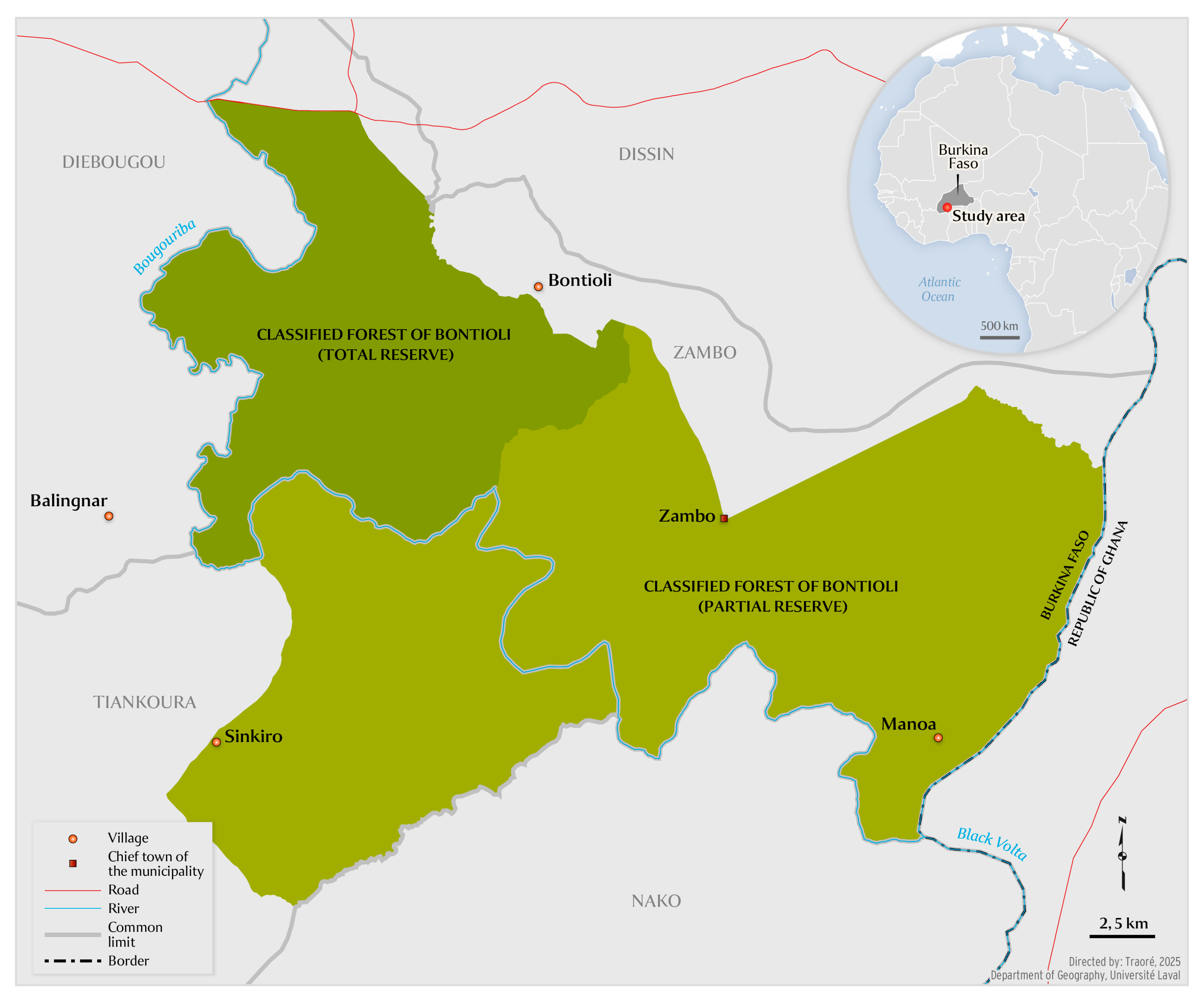

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

- Sinkiro and Manoa, located inside the forest,

- Bontioli, on the forest edge,

- Balingnar, approximately 5 kilometers from the forest.

- The selection of these villages was based on accessibility and security recommendations at the time of the surveys (January to June 2022).

3. Results

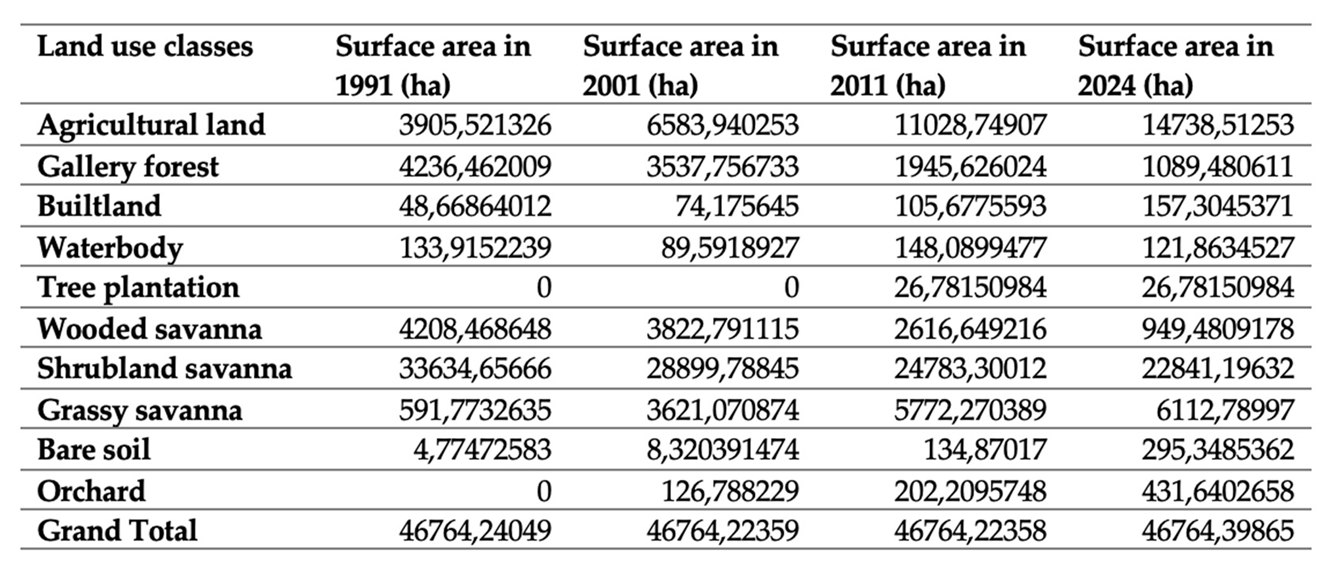

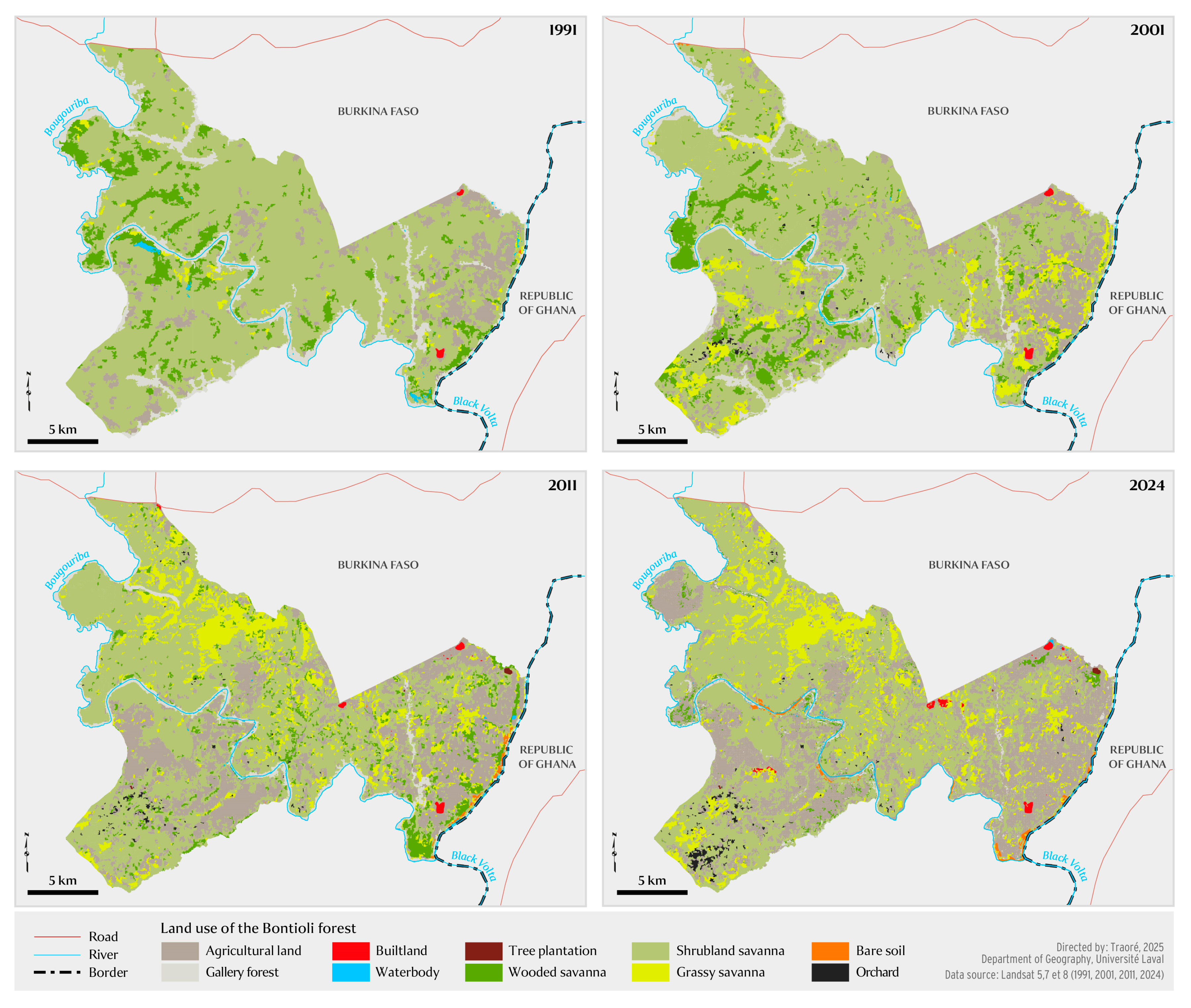

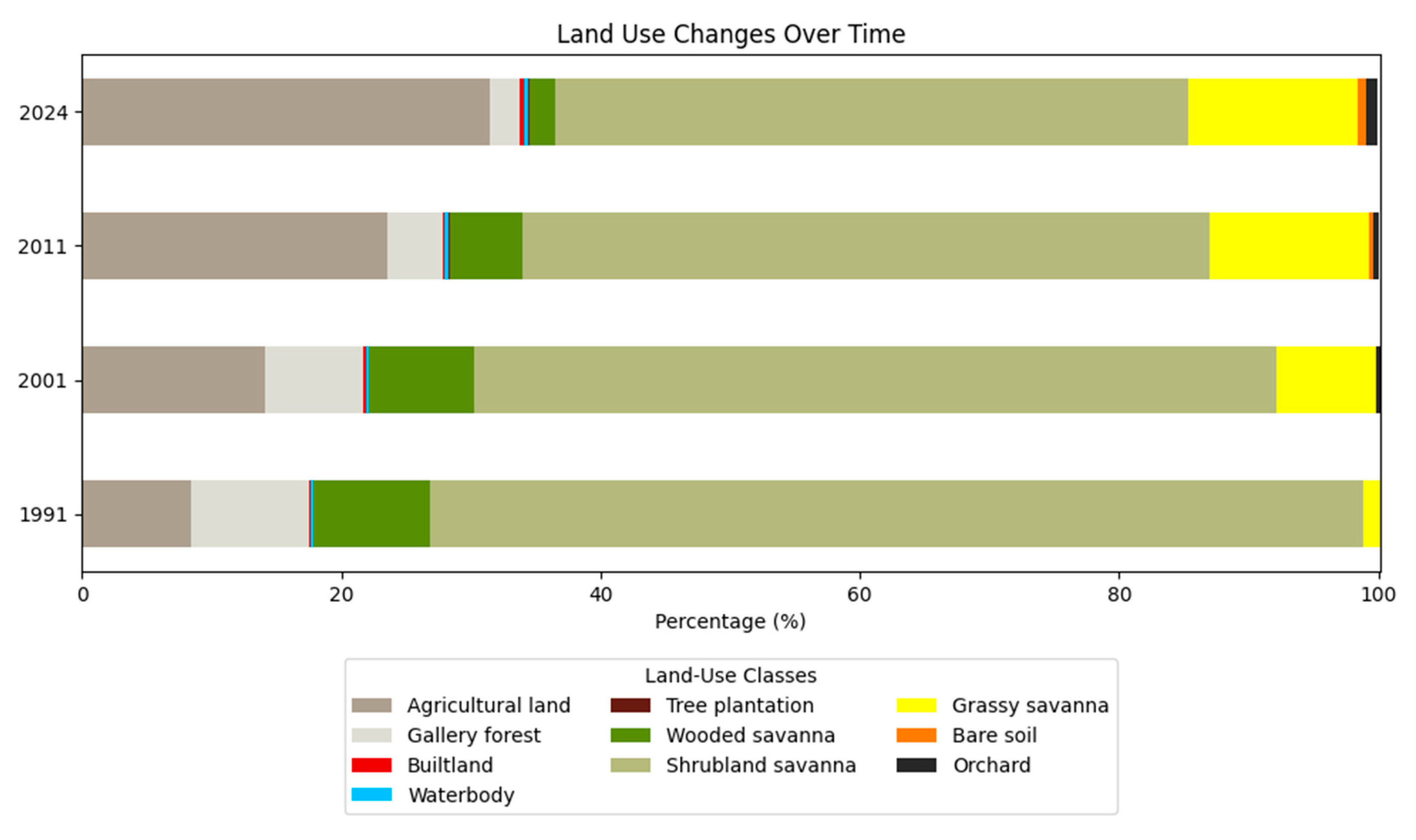

3.1. Land Use Dynamics and Key Drivers of Deforestation

3.2. Different Perceptions of Deforestation

“The forest is everything to us. It’s our sorghum, our millet, our sauce. Everything we have comes from the forest. Seeing it disappear like this deeply saddens us. We collect non-timber forest products (NTFPs), and we also gather wood, which is our main source of energy. The forest must be preserved.”

“During awareness sessions, agricultural officers recommend that we keep 20 fruit trees per hectare of cultivated land. But whenever we come across useful trees, like fruit trees, we preserve them systematically. Sometimes we even keep more than the recommended amount.”

“We don’t cut down trees randomly. We usually remove old trees that no longer offer much benefit. If a tree casts too much shade, we cut it down because it affects agricultural yields. So we don’t act carelessly. In fact, fruit trees are more productive on cultivated land than on uncultivated land.”

3.3. Toward Local Forms of Adaptation

3.4. Implications of Forest Conservation for Socio-Economic Development

3.5. Attributing Responsibility for Forest Resource Degradation

3.6. Loss of Traditional Values and Forest Conservation

3.7. A Contrasting View of Opportunities Available to Local Populations

4. Discussion

4.1. Survival and Deforestation

4.2. Resource Use Conflicts and Deforestation

4.3. Diverging Perceptions of Forest Conservation

4.4. Socio-Economic Consequences of Forest Conservation

4.5. Perspectives for Better Integration of Local Needs into Forest Conservation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lapola, D.; Pinho, P.; Barlow, J.; Aragão, L.; Berenguer, E.; Carmenta, R.; Liddy, H.; Seixas, H.; Silva, C.; Silva-Junior, C.; et al. The drivers and impacts of Amazon forest degradation. Science 2023, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belem, M.; Zoungrana, M.; Moumouni, N. Les effets combinés du climat et des pressions anthropiques sur la forêt classée de Toéssin, Burkina Faso. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2018, 12, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B.; Sanou, L.; Koala, J.; Hien, M. Perceptions locales de la dégradation des ressources naturelles du corridor forestier de la Boucle du Mouhoun au Burkina Faso. 2022, 352, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global forest resources assessment 2015. Desk reference. 2015.

- Nesha, K.; Herold, M.; De Sy, V.; Duchelle, A.; Martius, C.; Branthomme, A.; Garzuglia, M.; Jonsson, O.; Pekkarinen, A. An assessment of data sources, data quality and changes in national forest monitoring capacities in the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005-2020. Environmental Research Letters 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly-Lingani, P. Appraisal of the Participatory Forest Management Program in Southern Burkina Faso. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, B. Forest Policies and Forest Fringe Households’ Resilience against Poverty in Participatory Forest Management Sites in Burkina Faso. Environmental Management and Sustainable Development 2018, 7, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiri, B.; Eveline, C.; Jacqueline, S.; Patrice, T.; Souleymane, O. Participatory Forest Management in Burkina Faso: Perceptions of Local Populations in the Cassou Managed Forest. Humanities and Social Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACO/IUCN. Évaluation de l’efficacité de la gestion des aires protégées : parcs et réserves du Burkina Faso; IUCN: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2009.

- Traoré, M.A. Impacts environnementaux et retombées socioéconomiques de la gestion tripartite de la faune dans la concession de chasse de Pagou-Tandougou (province de la Tapoa). Université Joseph Ki-Zerbo, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2019.

- Yelkouni, M. Gestion d'une ressource naturelle et action collective : le cas de la forêt de Tiogo au Burkina Faso. Université d'Auvergne - Clermont-Ferrand I, 2004.

- Devineau, J.-L.; Fournier, A.; Nignan, S. “Ordinary biodiversity” in western Burkina Faso (West Africa): what vegetation do the state forests conserve? Biodiversity and Conservation 2009, 18, 2075–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, S.; Savadogo, P.; Tigabu, M.; Ouadba, J.M.; Odén, P.C. Consumptive values and local perception of dry forest decline in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2010, 12, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiribou, R.; Dimobe, K.; Yameogo, L.; Yang, H.; Santika, T.; Dejene, S. Two decades of land cover change and anthropogenic pressure around Bontioli Nature Reserve in Burkina Faso. Environmental Challenges 2024, 17, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjognon, G.S.; Rivera-Ballesteros, A.; van Soest, D. Satellite-based tree cover mapping for forest conservation in the drylands of Sub Saharan Africa (SSA): Application to Burkina Faso gazetted forests. Development Engineering 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisberger, H.; Kindt, R.; Loo, J.; Schmidt, M.; Bognounou, F.; Da, S.S.; Diallo, O.; Ganaba, S.; Gnoumou, A.; Lompo, D.; et al. Spatially explicit multi-threat assessment of food tree species in Burkina Faso: A fine-scale approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatya, D.M.; Sun, G.; Rossi, C.G.; Ssegane, H.S.; Nettles, J.E.; Panda, S. Forests, Land Use Change, and Water. 2015.

- Michon, G. Ma forêt, ta forêt, leur forêt. Perceptions et enjeux autour de l’espace forestier. Bois Et Forets Des Tropiques 2003a, Numéro Spécial: ‘Forêts Détruites Ou Reconstruites ?, 278 : 215-224.

- FAO. Comparison of forest area and forest area change estimates derived from FRA 1990 and FRA 2000. In Proceedings of the Forest Resources Assessment, 2000; p. 59.

- Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Laestadius, L.; Bennett-Curry, A.; Buckingham, K.; Kumar, C.; Moll-Rocek, J.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Wilson, S.J. When is a forest a forest? Forest concepts and definitions in the era of forest and landscape restoration. Ambio 2016, 45, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.G. When Is a Forest Not a Forest? Journal of Forestry 2002, 100, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergeest, P.; Lee Peluso, N.; Bryant, R.L. The International Handbook of Political Ecology. In Chapter 12: Political forests; Edward Elgar Publishing: 2015.

- Putz, F.E.; Redford, K.H. The Importance of Defining ‘Forest’: Tropical Forest Degradation, Deforestation, Long-term Phase Shifts, and Further Transitions. Biotropica 2010, 42, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatiuk, R.; Tickle, P.; Wood, M.S.; Howell, C. Defining Australian forests. Australian Forestry 2003, 66, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Rapport spécial du GIEC sur les conséquences d’un réchauffement planétaire de 1,5 °C par rapport aux niveaux préindustriels et les trajectoires associées d’émissions mondiales de gaz à effet de serre dans le contexte du renforcement de la parade mondiale au changement climatique, du développement durable et de la lutte contre la pauvreté; 2018; p. 32.

- Claeys, F. Impacts du changement climatique sur la durabilité de l’exploitation forestière en Afrique centrale. 2018, 318.

- Sasaki, N.; Putz, F.E. Critical need for new definitions of “forest” and “forest degradation” in global climate change agreements. Conservation Letters 2009, 2, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Zarin, D.J. What Does Zero Deforestation Mean? Science 2013, 342, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, K.A.; Mohren, G.M.J.; Peña-Claros, M.; Kyereh, B.; Arts, B.J.M. Tracing forest resource development in Ghana through forest transition pathways. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Persson, U.M.; Godar, J.; Kastner, T. Deforestation displaced: trade in forest-risk commodities and the prospects for a global forest transition. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, N.; Naughton-Treves, L. Linking National Agrarian Policy to Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon: A Case Study of Tambopata, 1986–1997. In Proceedings of the Ambio, 2003.

- Ghazoul, J.; Buřivalová, Z.; García-Ulloa, J.; King, L. Conceptualizing Forest Degradation. Trends in ecology & evolution 2015, 30 10, 622-632.

- Thompson, I.D.; Guariguata, M.R.; Okabe, K.; Bahamóndez, C.; Nasi, R.; Heymell, V.; Sabogal, C. An Operational framework for defining and monitoring forest degradation. Ecology and Society 2013, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Grandón, A.; Donoso, P.J.; Gerding, V. Forest Degradation: When Is a Forest Degraded? Forests 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokkalingam, U.; Jong, W.d. Secondary forest: a working definition and typology. International Forestry Review 2001, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Montes de Oca, A.; Gallardo-Cruz, J.A.; Ghilardi, A.; Kauffer, E.; Solórzano, J.V.; Sánchez-Cordero, V. An integrated framework for harmonizing definitions of deforestation. Environmental Science & Policy 2021, 115, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. How blaming'slash and burn'farmers is deforesting mainland Southeast Asia. 2000.

- Aleixandre-Benavent, R.; Aleixandré-Tudo, J.L.; Castelló-Cogollos, L.; Aleixandre, J.L. Trends in global research in deforestation. A bibliometric analysis. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, M.B.; Barua, R. Effects of Deforestation on Environment: Special Reference to Assam. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development 2019.

- Mammadova, A.; Behagel, J.H.; Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.M. Deforestation As a Systemic Risk. The Case of Brazilian Bovine Leather. Forests 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, G.; Moizo, B.; Verdeaux, F.; De Foresta, H.; Aumeeruddy, Y.; Gely, A.; Smektala, G. Perceptions et usages de la forêt en pays bara (Madagascar). 2003b.

- Perlin, J. A Forest Journey: The Story of Wood and Civilization. 1989.

- Williams, M. Deforesting the earth from prehistory to global crisis : an abridgment; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2006.

- Harrison, R.P. Forests : the shadow of civilization; University of Chicago Press: Chicago (Ill.), 1992.

- Corvol, A. L'arbre et la nature (XVIIe-XXe siècles). 1987, 6, 67-82. [CrossRef]

- Soni, K. FOREST CONSERVATION & ENVIRONMENT. Journal of Science Innovations and Nature of Earth 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, K.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: A case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. Forest Policy and Economics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Hamad, H.; Andrews, J.; Hillis, V.; Mulder, M.B. Effects of perceptions of forest change and intergroup competition on community-based conservation behaviors. Conservation biology : the journal of the Society for Conservation Biology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joa, B.; Schraml, U. Conservation practiced by private forest owners in Southwest Germany – The role of values, perceptions and local forest knowledge. Forest Policy and Economics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Smith-Ramírez, C.; Claramunt, V. Differences in stakeholder perceptions about native forest: implications for developing a restoration program. Restoration Ecology 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maioli, V.; Monteiro, L.; Tubenchlak, F.; Pepe, I.; De Carvalho, Y.; Gomes, F.; Strassburg, B.; Latawiec, A. Local Perception in Forest Landscape Restoration Planning: A Case Study From the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pouliot, M.; Treue, T.; Obiri, B.; Ouédraogo, B. Deforestation and the Limited Contribution of Forests to Rural Livelihoods in West Africa: Evidence from Burkina Faso and Ghana. AMBIO 2012, 41, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Governor General of French West Africa. Arrêté conjoint portant délimitation et classement de le forêt et réserve totale de faune de Bontioli, portant délimitation et fixant le régime de la réserve partielle de faune de Bontioli-Cercle de Diébougou. 1957, 4.

- National Institute of Statistics and Demography. Cinquième récensement général de la population et de l’habitation : Monographie de la région du Sud-Ouest; 2022; p. 212.

- Gansaonré, R.N. Dynamique du couvert végétal et implications socio-environnementales à la périphérie du parc W/Burkina Faso. 2018, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.; Shahzad, A.; Zafar, B.; Shabbir, A.; Ali, N. Remote Sensing Image Classification: A Comprehensive Review and Applications. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Lu, Y.; Liu, T.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, C. Vectorization Method for Remote Sensing Object Segmentation Based on Frame Field Learning: A Case Study of Greenhouses. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.J.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O.Nyumba, T.; Wilson, K.A.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2018, 9, 20 - 32.

- The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd Ed. ed.; Sage Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2013.

- Reed, J.; Vianen, J.; Foli, S.; Clendenning, J.; Yang, K.; MacDonald, M.; Petrokofsky, G.; Padoch, C.; Sunderland, T. Trees for life: the ecosystem service contribution of trees to food production and livelihoods in the tropics. Forest Policy and Economics 2017, 84, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PIF. Actualisation du plan d’aménagement et de gestion des réserves partielle et totales de faune de Bontioli. 2017, 101.

- Olorunfemi, I.E.; Olufayo, A.A.; Fasinmirin, J.T.; Komolafe, A.A. Dynamics of land use land cover and its impact on carbon stocks in Sub-Saharan Africa: an overview. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ordway, E.; Asner, G.; Lambin, E. Deforestation risk due to commodity crop expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12. [CrossRef]

- Etongo, D.; Djenontin, I.; Kanninen, M.; Fobissie, K.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Djoudi, H. Land tenure, asset heterogeneity and deforestation in Southern Burkina Faso. Forest Policy and Economics 2015, 61, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomini, E.; Imoh, J.; Ameh, M.; Henry, M.; Ademiluyi, I.; Mbah, J.; Vihi, S.; Nguwap, Y.; Ogenyi, R.; Chomini, M. Forestry Resource Exploitation by Rural Household, Their Pathways out of Poverty and its Implications on the Environment. A Case Study of Toro LGA of Bauchi State, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2022. [CrossRef]

- Püttker, T.; Crouzeilles, R.; Almeida-Gomes, M.; Schmoeller, M.; Maurenza, D.; Alves-Pinto, H.; Alves-Pinto, H.; Pardini, R.; Vieira, M.; Banks-Leite, C.; et al. Indirect effects of habitat loss via habitat fragmentation: A cross-taxa analysis of forest-dependent species. Biological Conservation 2020, 241, 108368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brottem, L. Environmental Change and Farmer-Herder Conflict in Agro-Pastoral West Africa. Human Ecology 2016, 44, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alusiola, R.; Schilling, J.; Klär, P. REDD+ Conflict: Understanding the Pathways between Forest Projects and Social Conflict. Forests 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badola, R. Attitudes of local people towards conservation and alternatives to forest resources: A case study from the lower Himalayas. Biodiversity & Conservation 1998, 7, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, T.; Vasquez, W. Forest Conservation, Rights, and Diets: Untangling the Issues. 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Chomba, S.; Nathan, I.; Minang, P.; Sinclair, F. Illusions of empowerment? Questioning policy and practice of community forestry in Kenya. Ecology and Society 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ece, M.; Murombedzi, J.; Ribot, J. Disempowering Democracy: Local Representation in Community and Carbon Forestry in Africa. Conservation and Society 2017, 15, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaugh, J.; Pradhan, N.; Adams, J.; Oldekop, J.; Agrawal, A.; Brockington, D.; Pritchard, R.; Pritchard, R.; Chhatre, A. Global forest restoration and the importance of prioritizing local communities. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2020, 4, 1472–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massinga, J.; Lisboa, S.; Virtanen, P.; Sitoe, A. Impact of Conservation Policies on Households’ Deforestation Decisions in Protected and Open-Access Forests: Cases of Moribane Forest Reserve and Serra Chôa, Mozambique. 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Duguma, L.; Minang, P.; Foundjem-Tita, D.; Makui, P.; Piabuo, S.M. Prioritizing enablers for effective community forestry in Cameroon. Ecology and Society 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- Majambu, E.; Wabasa, S.M.; Elatre, C.W.; Boutinot, L.; Ongolo, S. Can Traditional Authority Improve the Governance of Forestland and Sustainability? Case Study from the Congo (DRC). Land 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajembe, G.; Luoga, E.; Kijazi, M.; Mwaipopo, C. The role of traditional institutions in the conservation of forest resources in East Usambara, Tanzania. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 2003, 10, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, M.D.; Barati, A.; Azadi, H.; Scheffran, J.; Shirkhani, M. Analyzing forest residents' perception and knowledge of forest ecosystem services to guide forest management and biodiversity conservation. Forest Policy and Economics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).