Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

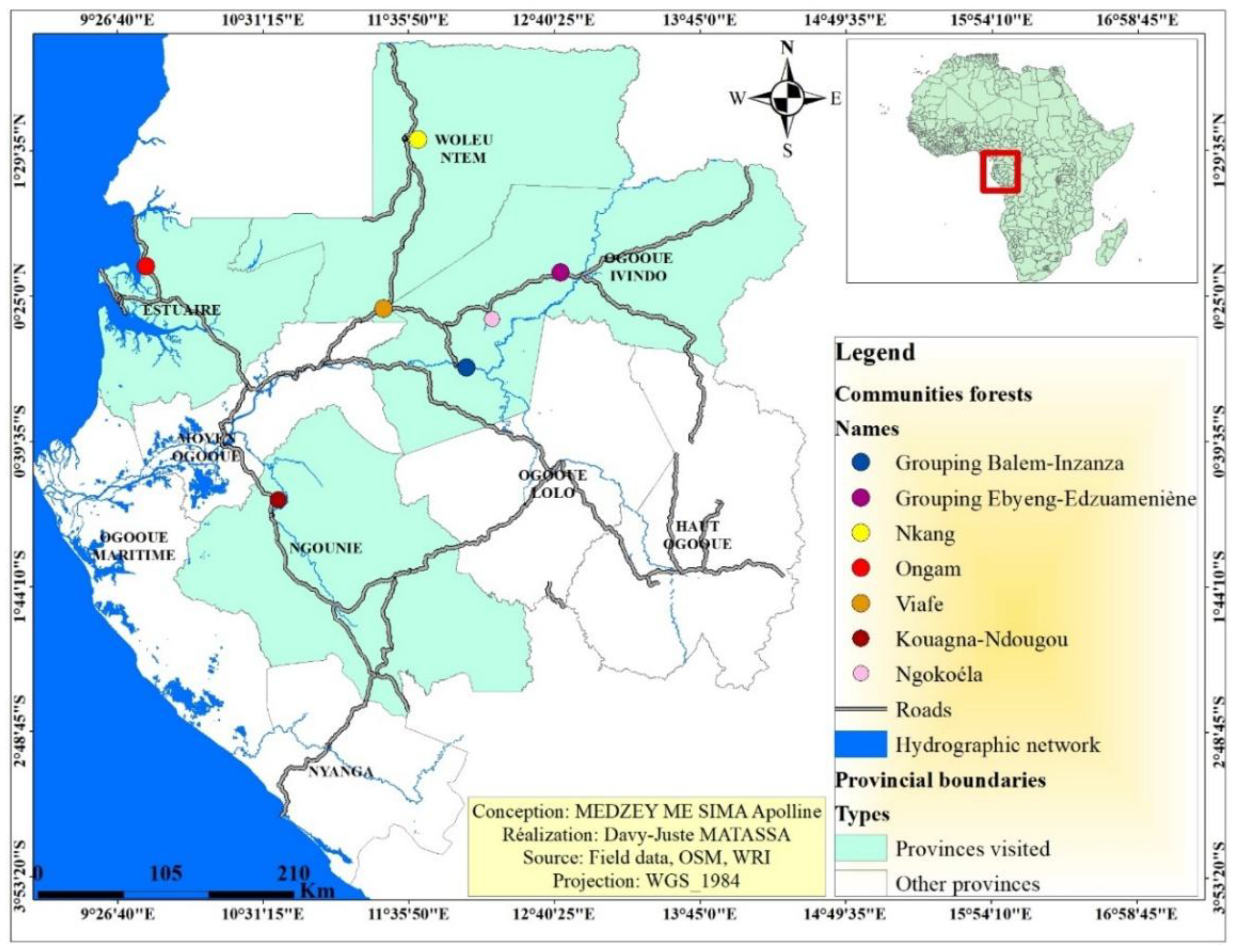

2.1. Presentation of the Study Sites

2.2. Site Selection and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics and Governance of the Studied CFs

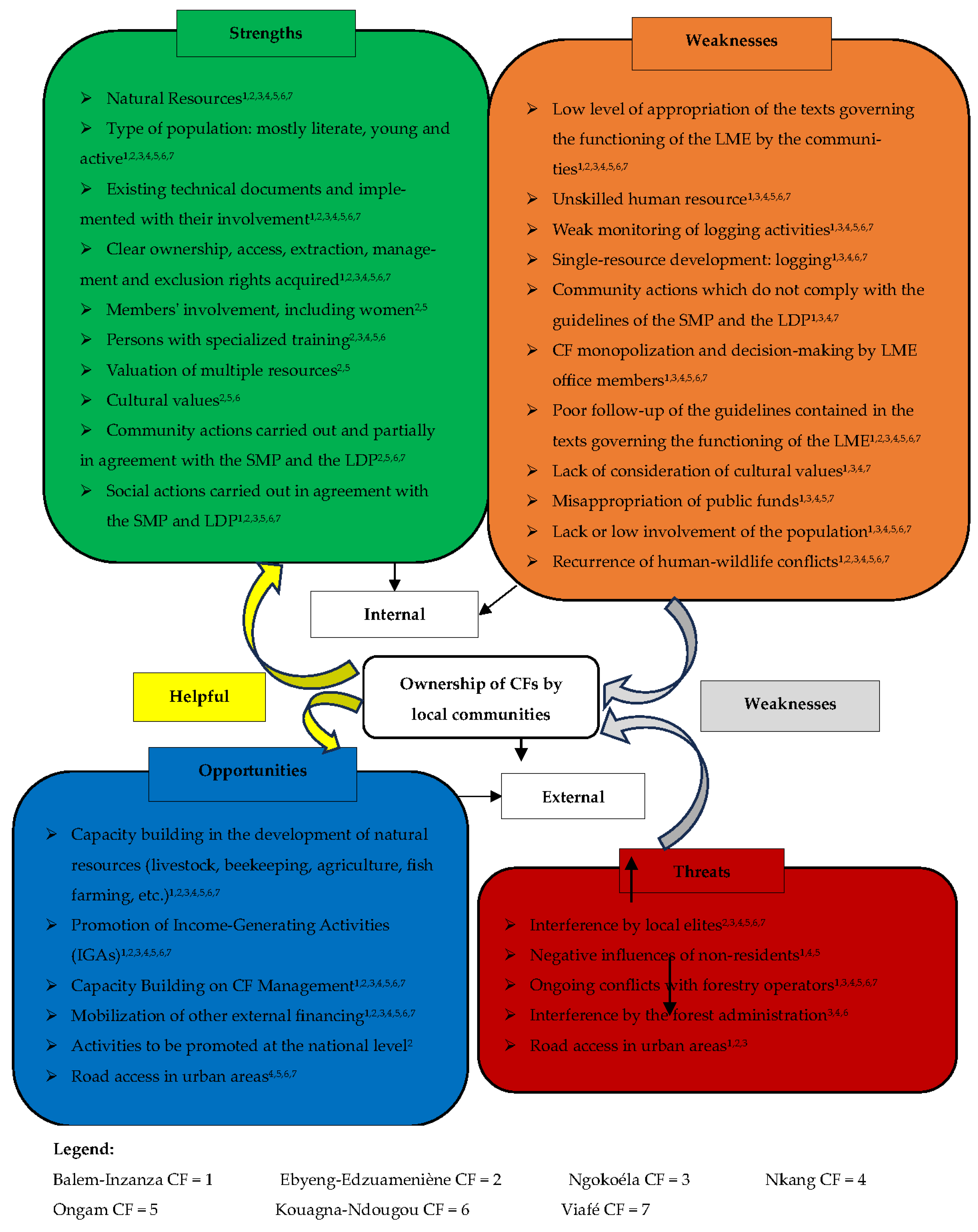

3.2. SWOT Analysis of Community Forests

3.2.1. Strengths and Weaknesses

Respondent 17: We have a lot of wood in the bush. We don't know why they made such a mess of it. We have a lot of wood in the bush that they didn't take. And we don't know why that wood is now rotting in the bush. They've been aware of this ever since, but we haven't yet had any takers who feel able to come and take everything that's on the ground. Indeed, what the project manager has just told you is all well and good, because these people know how to salvage nothing but Kevazingo [African rosewood, Guibourtia, Fabaceae]. And this Kevazingo, they haven't taken everything. Some Kevazingos are still in the bush.

Respondent 47: [...] even the head of the forestry department once told us that you have to make sacrifices because there are too many accidents. We too said yes, because we have to make sacrifices to protect the lives of human beings, other people's children and other people's drivers. Even he said that I couldn't send my contingents to go and carry out missions in your forest, because one of my sons, the deputy general secretary's grand brother, had his head cut off here, but thank God he wasn't dead.

Respondent 80: Normally, before starting the forest, there are tombs there. So, when it comes to exploiting this area of forest, the owners have to come and talk. At the sacrifice, you give them wine and food so that the workers don't have too many accidents, because sometimes the wood refuses to fall. It even blocks the machine. Our forest has grandfathers in it, so to work properly, we'd have to ask permission from the grandfathers. Once we've done that, it's all over, and people go to work.

Respondent 41: There's hatred. There is no understanding between families.

3.2.2. Opportunities and Threats

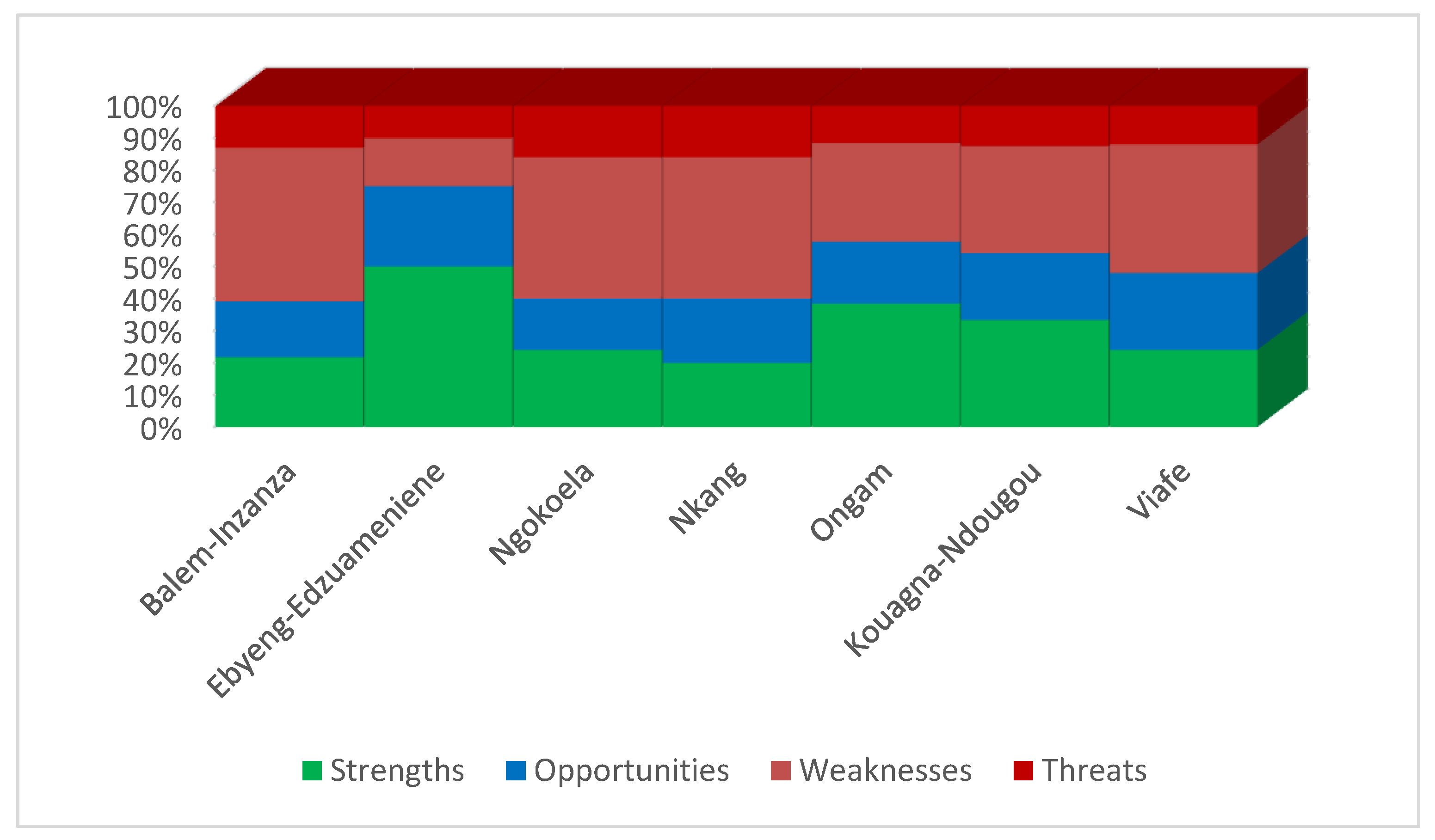

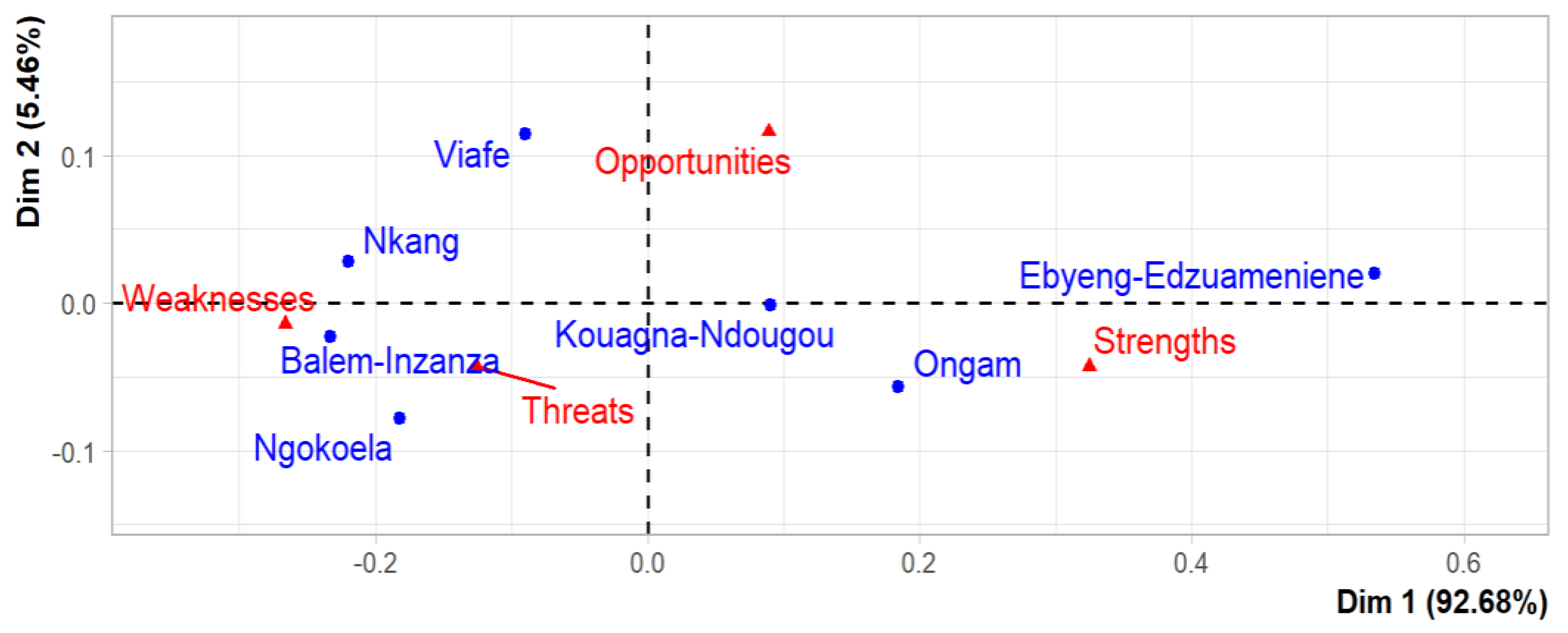

3.3. CF Representation by the Heatmap and FCA

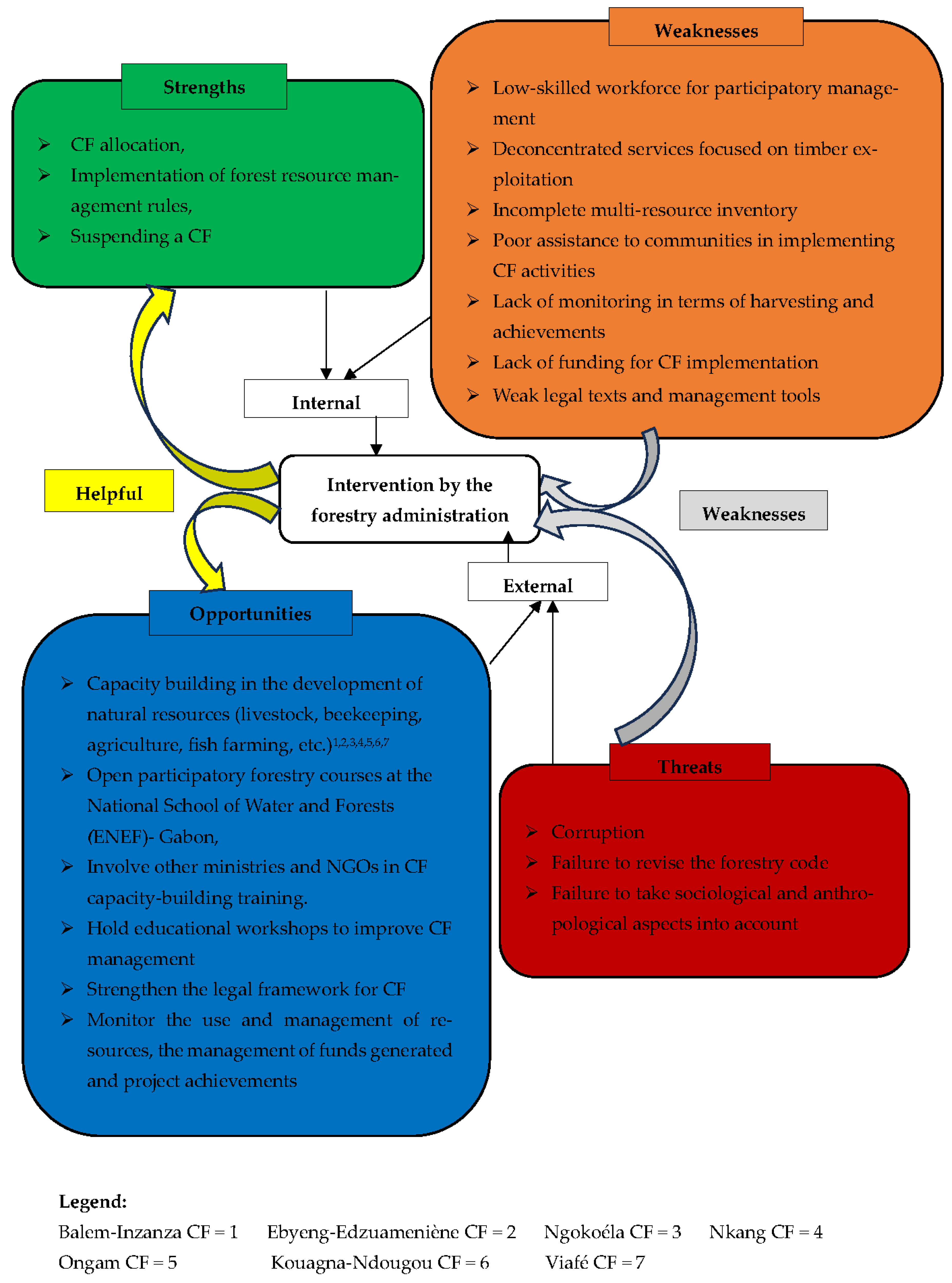

3.4. SWOT Analysis of Forest Administration Intervention in CFs

Respondent 1: Our role is to support communities wishing to set up and manage community forests. This implies technical responsibility for setting up community forests and overseeing their management. This involvement takes the form of carrying out preliminary technical work before the community forest is allocated. So, according to the law, the work is carried out free of charge for the benefit of the communities, but this is not always the case in the field due to financial problems. This doesn't always make it possible to apply this free service. So some communities that have a little money, ask the administration to support them, but this support is more due to travel to be in the field, but the work is carried out by the administration. Increasingly, they are calling on external expertise other than that provided by the administration, which is often referred to as a consulting firm. But the administration is obliged to validate the work carried out by these firms.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bigombe Logo, P. Les Élites et La Gestion Décentralisée Des Forêts Au Cameroun . Essai d ’ Analyse Politiste de La Gestion Néopatrimoniale de La Rente Forestière En Contexte de Décentralisation. In Proceedings of the Colloque Gecolev (Gestion Concertée des Ressources Naturelles), Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France; 2006; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, A.M.; Castro, L.C. Sustainable Resource Use & Sustainable Development: A Contradiction? Center of Development Research, University of Bonn 2004, 1, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nkwinkwa, R. La Gestion Participative Des Forêts: Expériences En Afrique de l’Ouest et Au Cameroun. In Sustainable management of African rain forest, Part I: Workshops; 2001; pp. 155–158.

- Buttoud, G.; Nguinguiri, J.-C. L’association Des Acteurs à La Politique et La Gestion Des Forêts. Un Constat Nuancé. In La gestion inclusive des forêts d’Afrique centrale: passer de la participation au partage des pouvoirs; Buttoud, G., Nguinguiri, J.-C., Aubert, S., Karsenty, A., Kouplevatskaya Buttoud, I., Lescuyer, G., Eds.; FAO-CIFOR: Libreville-Bogor, 2016; pp. 3–15. ISBN 9786023870295. [Google Scholar]

- Nguinguiri, J.C. Les Approches Participatives Dans La Gestion Des Ecosystemes Forestiers d’Afrique Centrale: Revue Des Initiatives Existantes. 1999, 62. [CrossRef]

- Nguimbi, L. Evaluation de l’étendue et de l’efficacité de La Foresterie Participative Au Gabon; Libreville. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gareau, P. Approches de Gestion Durable et Démocratique Des Forêts Dans Le Monde. VertigO 2005, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier, Q.; Vermeulen, C.; Moumbogou, C. Les Premières Forêts Communautaires Du Gabon Sont - Elles Condamnées d ’ Avance ? Parcs et Réserves 2011, 17–22.

- McDermott, M.H.; Schreckenberg, K. Equity in Community Forestry: Insights from North and South. International Forestry Review 2009, 11, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeumo, A. Développement Des Forêts Communautaires Au Cameroun: Génèse, Situation Actelle et Contraintes. ODI Rural Development Forestry Network 2001, 25 bi.

- Federspiel, M.; Vermeulen, C.; Carr, B.; Somé, L.; Doucet, J.L. Le Projet DACEFI : Contexte, Philosophie et Résultats Attendus. In Les premières forêts communautaires au GAbon; 2008; pp. 5–8.

- Meunier, Q.; Boldrini, S.; Larzillière, A.; Federspiel, M.; Vermeulen, C. Principes Fondateurs d ’ Une Forêt Communautaire Au Gabon. Outils de Vulgarisation et de Sensibilisation, 2014.

- Mbairamadji, J. De La Décentralisation de La Gestion Forestière à Une Gouvernance Locale Des Forêts Communautaires et Des Redevances Forestières Au Sud-Est Cameroun. VertigO 2009, 9, 0–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, J. Facteurs de Succès et Contraintes à La Foresterie Communautaire : Étude de Cas et Évaluation de Deux Initiatives, Mémoire de maitrise, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2013.

- Teitelbaum, S. Criteria and Indicators for the Assessment of Community Forestry Outcomes: A Comparative Analysis from Canada. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 132, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumba, E.P. Détermination Des Préalables et Des Critères et Indicateurs de Gestion Durable, Applicables Aux Forêts Communautaires : Proposition Pour Le Gabon, Master, Université Senghor, 2009.

- Okouyi Okouyi, V.J.J. Savoirs Locaux et Outils Modernes Synégétiques: Développement de La Filière Commerciale de Viande de Brousse à Makokou (Gabon)., Thèse de Doctorat, Université d’Orléans, 2006.

- Cawthorn, D.M.; Hoffman, L.C. The Bushmeat and Food Security Nexus: A Global Account of the Contributions, Conundrums and Ethical Collisions. Food Research International 2015, 76, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Common-Pool Resources and Institutions: Toward a Revised Theory. Handbook of Agricultural Economics 2002, 2, 1315–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Baechler, L. Gouvernance Des Biens Communs, Pour Une Nouvelle Approche Des Ressources Naturelles; 2010; ISBN 978-2-8041-6141-5.

- Euler, J. Conceptualizing the Commons: Moving Beyond the Goods-Based Definition by Introducing the Social Practices of Commoning as Vital Determinant. Ecological Economics 2018, 143, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitot, A. La Chasse Villageoise et Le Commerce de Venaison, Une Évaluation Économique et Financière En République Centrafrique, Mémoire de Maitrise, AgroSup: Dijon, 2014.

- Cornelis, D.; Van Vliet, N.; Nguinguiri, J.C.; Le Bel, S. Gestion Communautaire de La Chasse En Afrique Centrale. À La Reconquête d’une Souveraineté Confisquée. In Communautés locales et utilisation durable de la faune en Afrique Centrale; Van Vlet, N., Nguinguiri, J.-C., Cornélis, D., Eds.; FAO: Bogor, 2017; pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-602-387-054-7. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, N.; Nguinguiri, J.C.; Cornelis, D.; Le Bel, S.; (eds.) Communautés Locales et Utilisation Durable de La Faune En Afrique Centrale; CIFOR, CIRAD, FAO, 2017; ISBN 9789252098041.

- Ballet, J.; Kouamékan, J.-M.K.; Kouadio, B.K. La Soutenabilité Des Ressources Forestières En Afrique Subsaharienne Francophone: Quels Enjeux Pour La Gestion Participative? Mondes endéveloppement 2009, 148, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonye, D. Evaluation de l’impact de La Gestion Des Forêts Communautaires Au Cameroun, Mémoire de Maitrise, Université Laval, Québec, 2008.

- Nelson, F. Gestion Communautaire de La Faune Sauvage En Tanzanie, 2007.

- Fortin, M.-F.; Gagnon, J. Fondements et Étapes Du Processus de Recherche: Méthodes Quantitatives et Qualitatives; 3e édition.; Chenelière éducation,: Montréal. 2016; ISBN 2765050066. [Google Scholar]

- Beaud, J.-P. L’échantillonnage. In Recherche sociale. De la problématique à la collecte des données; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Québec, 2009; Vol. 5, pp. 169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Savoie-zajc, L. Comment Peut-on Construire Un Échantillonnage Scientifique Valide? Recherches Qualitatives 2006, 5, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ibnezzyn, N.; Benabdellah, M.; Aitlhaj, A. Analyse SWOT de La Filière de l’arganier: Etat Des Lieux, Défis et Des Perspectives. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét 2022, 10, 287–291. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team RA Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical. 2021.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, R.; Kozak, R.A.; El-Lakany, H.; Innes, J.L.; Robert, A. kozak; Hosny, E.-L.; John, L.I. Community Forests for Forest Communities: Integrating Community-Defined Goals and Practices in the Design of Forestry Initiatives. Land use policy 2013, 34, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, S.E. Community Forestry in Canada: Lessons from Policy and Practice; UBC Press, 2016; ISBN 077483191X.

- Chapman, J.M.; Schott, S. Knowledge Coevolution: Generating New Understanding through Bridging and Strengthening Distinct Knowledge Systems and Empowering Local Knowledge Holders. Sustainability Science 2020, 15, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqmain, H.; Nadeau, S.; Bélanger, L.; Courtois, R.; Bouthillier, L.; Dussault, C. (2006) Valoriser Les Savoirs Des Cris de Waswanipi Sur l’orignal Pour Améliorer l’aménagement Forestier de Leurs Territoires de Chasse. Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec 2006, 36, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqmain, H.; Dussault, C.; Courtois, R.; Bélanger, L. Moose-Habitat Relationships: Integrating Local Cree Native Knowledge and Scientific Findings in Northern Quebec. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2008, 38, 3120–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqmain, H.; Bélanger, L.; Courtois, R.; Dussault, C.; Beckley, T.M.; Pelletier, M.; Gull, S.W. Aboriginal Forestry: Development of a Socioecologically Relevant Moose Habitat Management Process Using Local Cree and Scientific Knowledge in Eeyou Istchee. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2012, 42, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouki, T. La Participation Dans Les Forêts Communautaires Du Sud-Cameroun. In La gestion inclusive des forêts d’Afrique centrale: passer de la participation au partage des pouvoirs; Buttoud, G., Nguinguiri, J.-C., Aubert, S., Bakouma, J., Karsenty, A., Kouplevatskaya Buttoud, I., Lescuyer, G., Eds.; FAO-CIFOR: Libreville-Bogor, 2016; pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kialo, P. Les Forêts Communautaires Au Gabon. Les sylvo-anthroponymes pové: Cahiers Gabonais d’anthropologie 2006, 2115–2136.

- Schippers, C.; Bracke, C.; Ndouna Ango, A.; Ndongo Nguimfack, C.; Mihindou, V.; Bouroubou, F.; Dissaki, A.; Vermeulen, C. Délimiter Les Forêts Communautaires: Une Approche Par Contraintes Multiples. In Les premières forêts communauatires du Gabon; Vermeulen, C., DOUCET, J.-L., Eds.; 2008; pp. 47–55.

| Name of the CF | Province | SIG | Villages / districts | Ethnic groups | Name of LME | Final agreement |

| Balem- Inzanza |

Ogooué-Ivindo |

0°6'11.88"N 11°59'33.47"E |

Balem et Inzanza |

Makina, Saké Ndambomo, Kota et Fang | Melare (Gathering of villages) |

2017 |

| Ebyeng-Edzuameniène | Ogooué-Ivindo | 0°35'34.30"N 12°42'36.79"E | Ebyeng Edzuame-niène | Fang |

A2E (Ebyeng-Edzuameniène association) |

2013 |

| Ngokoéla |

Ogooué-Ivindo |

0°16'42.72"N 12°12'32.34"E |

Ngouriki, Nkaritom, Kombani Elata-Bakota | Fang, Kota, Makina Saké | Ngokoéla (abreviation of the name of 4 districts) | 2016 |

| Nkang |

Woleu-Ntem | 1°35'5.75"N 11°41'29.80"E | Nkang |

Fang |

Nnem mbô (Our hearts are one) | 2013 |

| Viafé |

Woleu-Ntem | 0°19'27.34"N 11°24'52.92"E | Viafé |

Fang |

Obangame (Defending your own) | 2017 |

| Kouagna-Ndougou | Ngounié |

1°1'53,29"S 10°36'18,24"E |

Kouagna Ndougou |

Tsogo, Eshira Akélé |

Tokano |

2017 |

| Ongam |

Estuaire | 0°38'30.66"N 9°39'21.56 "E | Ongam, Abenelang, Biyemame, Nzong-Meyong, Alos, Nombo |

Fang, Puvi Sékiani |

Elat-Meyong (union of tribes) | 2016 |

| Populations Technical documents Type of LME Decision-making body Areas (hectares) Breakdown of funds generated Planned income-generating community activities Community income-generating activities Community development projects planned Community development projects completed |

Educational level: 11% illiterate; 21% primary; 56% secondary and 12% university Fairly young: on average, 48% are in the 0-17 age group; 31%, 19% of whom are women, are in the 18-49 age group and 21% are in the 50+ age group LME certificate, articles of association, internal rules, SMP, LDP Associations1,2,4,5,6,7 and cooperative3 General Meeting 9 5291, 1 2562, 4 9933, 2 9734, 2 9655, 9 3896 et 2 5397 Development projects from 25% to 50%2,3,7, social projects 25%2,3,5, LME management costs from 5% to 25%2,3,7, relief fund 10%2,3, worker’s wages from 10% to 25%2,3, purchase and maintenance of equipment from 5% to 10%2,3, ecomuseum 5%2 Logging1,2,3,4,6,7, sawmill6, NTFP1,2,3,6, agriculture1,2,3,6, agroforestry1,3,6, forestry1,6, livestock1,2,3,4,6, fishing1,2,3,6,7, hunting1,2,3,4,6,7, construction of a cassava processing unit1,6, commissary1,6, carpentry1,6, conservation1,2,6, tourism1,6, beekeeping2,3,4, fish farming4, purchase of equipments3, purchase of vehicles1,6 Logging1,3,4,5,6,7, rental of cassava processing machine1, beekeeping2, iboga cultivation2, NTFP exploitation2, ecolodges (room rental)2, sale of tree species from nurseries2, reforesttion2, fishing5, sand exploitation5, tent and chair rental5, chainsaw rental5, equipment purchase2,3,5 Village hydraulics1,2,3,4,6,7, electrification1,3,4,6,7, housing modernization1,3,6, construction of a listening hut1,2,4,6,7, purchase of two vehicles1, construction or renovation of a school2,6,7, infirmary2,6, construction of a church2, construction of LME headquarters2, construction of a pharmaceutical depot3, donations of school kits3,7, construction of a public market6, construction of a playground6, construction housing for teachers and nurses4,7 Unfinished village hydraulics project1,7, electrification1,3, purchase of TVsets1, purchase of TV subscription boxes1, back-to-school kits1,5,7, assistance with healthcare, deaths and mariage1,4,5,6,7, rehabilitation of 15 km of old road1, gendarmerie post2, construction of unfinished church2, infirmary2, purchase medecines2,5 modernization of housing3,5, rehabilitation of school5,6,7, construction of listening hut7 |

|

Legend: Balem-Inzanza CF = 1 Ebyeng-Edzuameniène CF = 2 Ngokoéla CF = 3 Nkang CF = 4 Ongam CF = 5 Kouagna-Ndougou CF = 6 Viafé CF = 7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).