Submitted:

13 September 2023

Posted:

15 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

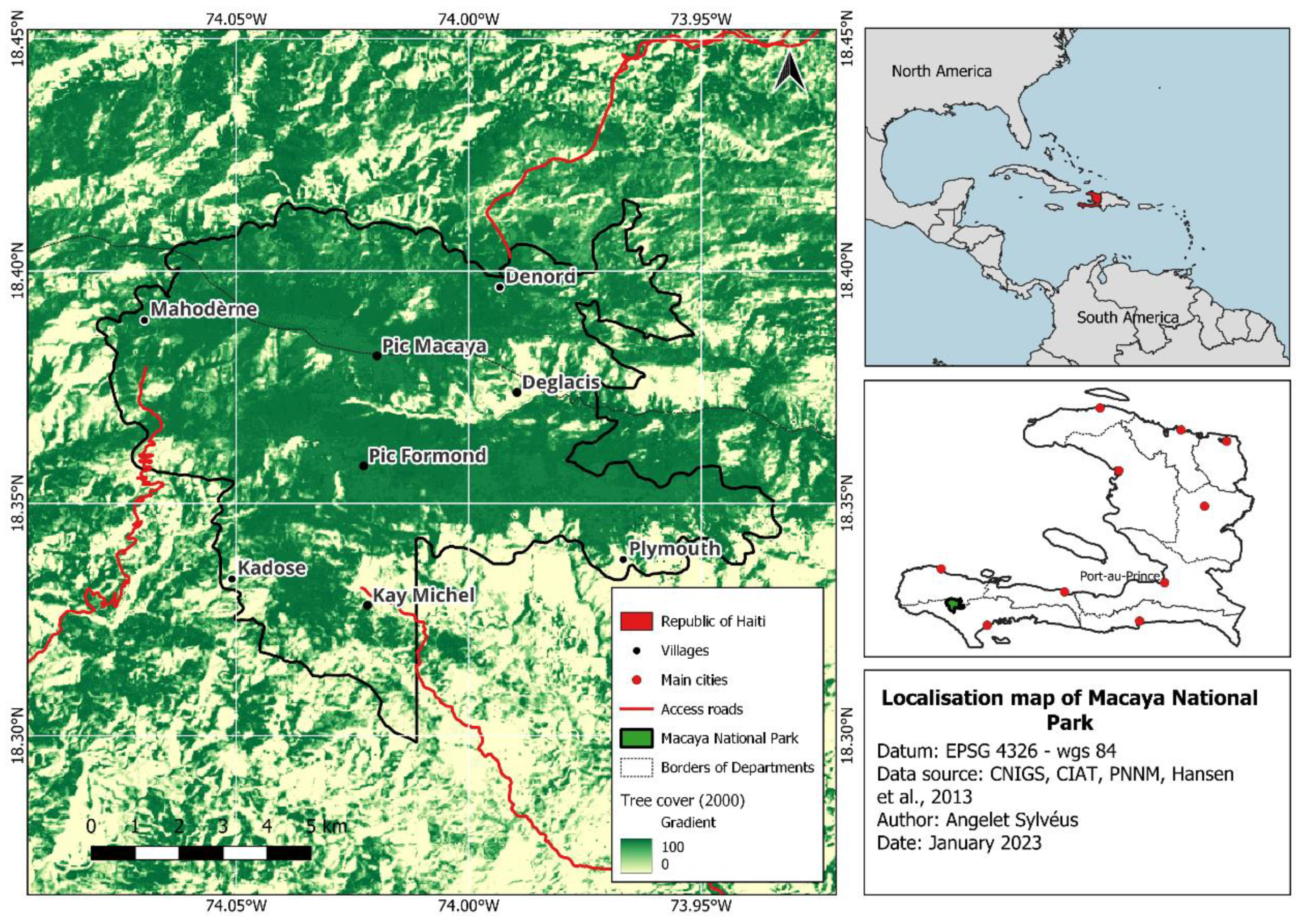

2.1. Study area

2.2. Data acquisition and pre-processing

2.3. Data analysis

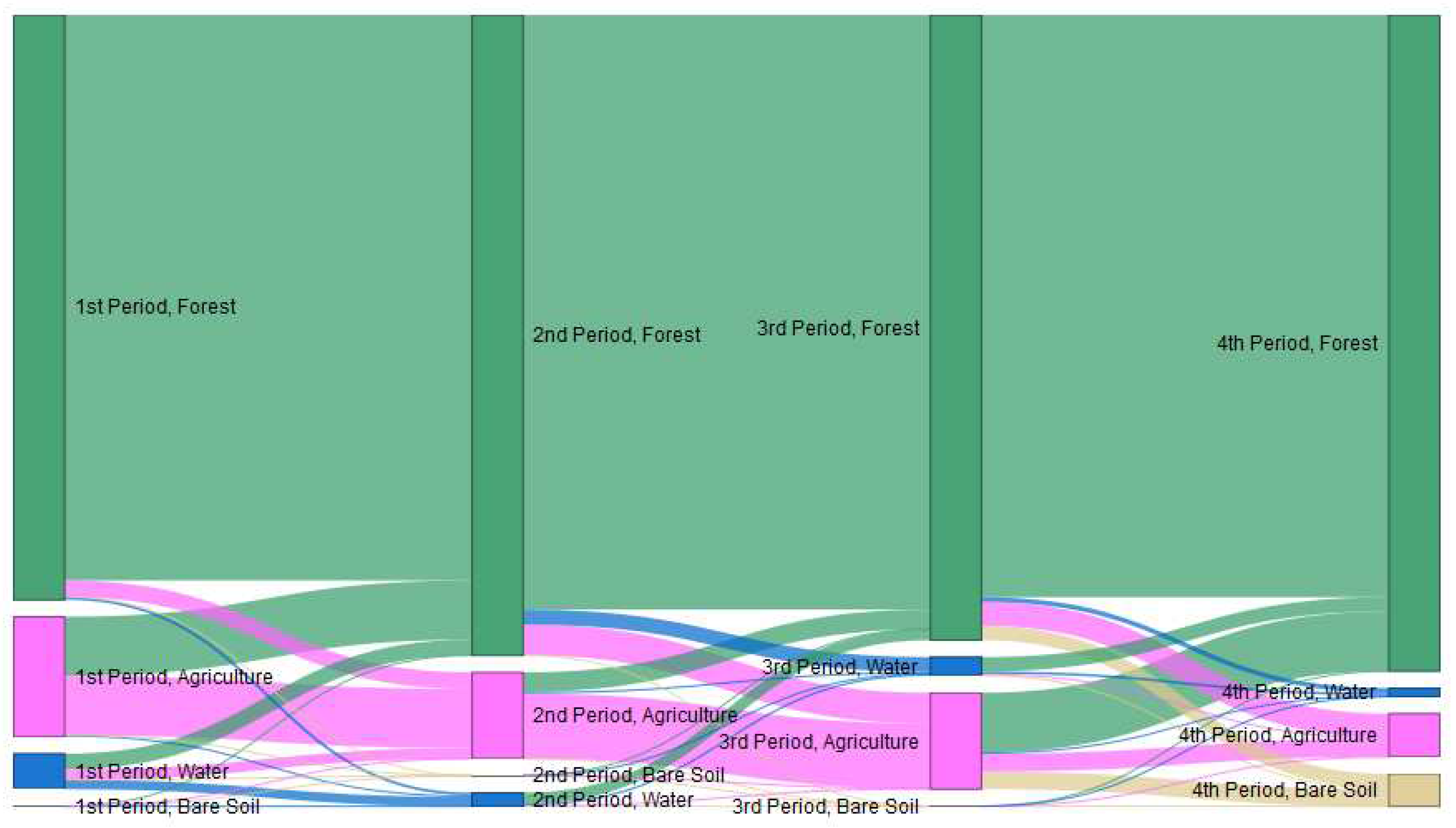

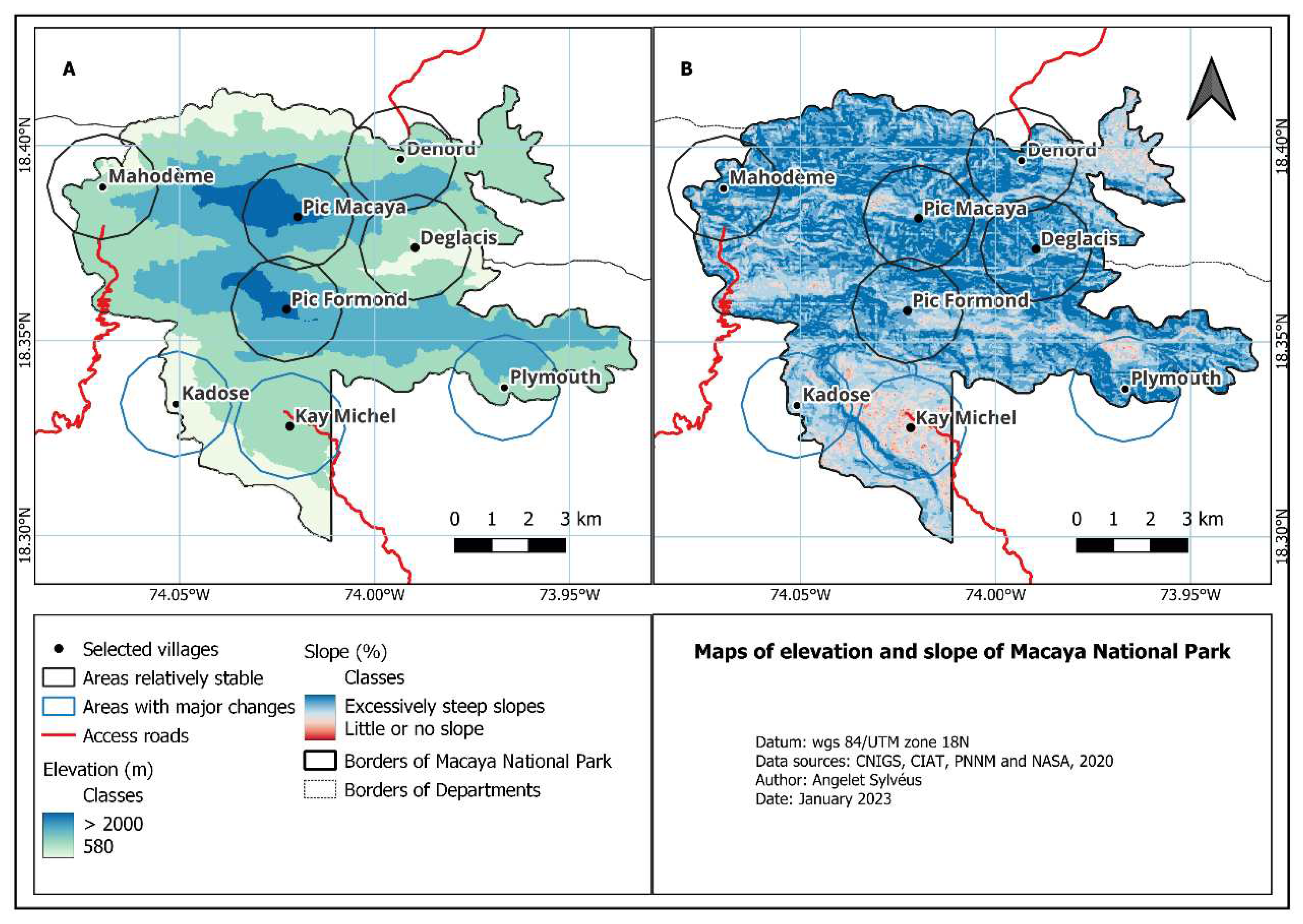

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-economic factors affecting land-use/land-cover changes

4.2. Ecological factors affecting land-use/land-cover changes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

References

- Malhi, Y.; Gardner, T. A.; Goldsmith, G. R.; Silman, M. R.; Zelazowski, P. Tropical forests in the anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2014, 39, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; França, F.; Gardner, T. A.; Hicks, C. C.; Lennox, G. D.; Berenguer, E.; et al. The future of hyperdiverse tropical ecosystems. Nature 2018, 559, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, O.; Padoch, C.; Fox, J.; Cramb, R. A.; Leisz, S. J.; Lam, N. T.; et al. Swidden change in southeast Asia: Understanding causes and consequences. Human Ecology 2009, 37, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G. P.; Rudel, T. K.; Aide, T. M.; Defries, R.; Emerson, R. A contemporary assessment of change in humid tropical forests. Conservation Biology 2009, 23, 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, P. J. A.; Pimentel, D.; Bryant, R. B. The ecological sustainability of slash-and-burn agriculture. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 1995, 52, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Truong, D. M.; Rambo, A. T.; Tuyen, N. P.; Cuc, L. T.; Leisz, S. Shifting cultivation: A new old paradigm for managing tropical forests. BioScience 2000, 50, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoya, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Shinoda, Y.; Nansai, K. Shifting agriculture is the dominant driver of forest disturbance in threatened forest species’ ranges. Communications Earth and Environment 2022, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E. F.; Meyfroidt, P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E. F.; Geist, H. J.; Lepers, E. DYNAMICS OF LAND-USE AND LAND-COVER CHANGE IN TROPICAL REGIONS. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2003, 28, 205–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay-des-Combes, J. M.; Robroek, B. J. M.; Hervé, D.; Guillaume, T.; Pistocchi, C.; Mills, R. T. E.; et al. Slash-and-burn agriculture and tropical cyclone activity in Madagascar: Implication for soil fertility dynamics and corn performance. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2017, 239, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R. L. Second Growth: The Promise of Tropical Forest Regeneration in an Age of Deforestation; 2014; Vol. 134.

- Lugo, A. E. Effects and outcomes of Caribbean hurricanes in a climate change scenario. The Science of the Total Environment 2000, 262, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R. A.; Rubiera, J.; Landsea, C.; Fernández, M. L.; Klein, R. Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials. Natural Hazards Review 2003, 4, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovac, C. C.; Dutrieux, L. P.; Siti, L.; Peña-Claros, M.; Bongers, F. Spatial and temporal dynamics of shifting cultivation in the middle-Amazonas river: Expansion and intensification. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Harsh, M. Landscape change in Guatemala: Driving forces of forest and coffee agroforest expansion and contraction from 1990 to 2010. Applied Geography 2013, 40, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, T. F.; Escada, M. I. S.; Valeriano, D. M.; Hostert, P.; Gollnow, F.; Müller, H. Forest degradation associated with logging frontier expansion in the Amazon: The BR-163 region in southwestern pará, Brazil. Earth Interactions 2016, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W. F.; Curran, T. J. Impacts of wind disturbance on fragmented tropical forests: A review and synthesis. Austral Ecology 2008, 33, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, A. E. Visible and invisible effects of hurricanes on forest ecosystems: An international review. Austral Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Aide, T. M.; Clark, M. L.; Grau, H. R.; López-Carr, D.; Levy, M. A.; Redo, D.; et al. Deforestation and Reforestation of Latin America and the Caribbean (2001-2010). Biotropica 2013, 45, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, A.; Ladet, S.; Coqué, N.; Gibon, A. Agricultural land-use change and its drivers in mountain landscapes: A case study in the Pyrenees. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2006, 114, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, V.; Francesconi, W. Environmental predictors of forest change: An analysis of natural predisposition to deforestation in the tropical Andes region, Peru. Applied Geography 2018, 91, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, V.; Francesconi, W.; Quintero, M. Spatial modeling of deforestation processes in the Central Peruvian Amazon. Journal for Nature Conservation 2016, 29, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrowclough, M.; Stehouwer, R.; Alwang, J.; Gallagher, R.; Barrera Mosquera, V. H.; Domínguez, J. M. Conservation agriculture on steep slopes in the Andes: Promise and obstacles. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2016, 71, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boose, E. R.; Foster, D. R.; Fluet, M. Hurricane Impacts to Tropical and Temperate Forest Landscapes. Ecological Monographs 1994, 64, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovac, C. C.; Peña-Claros, M.; Mesquita, R. C. G.; Bongers, F.; Kuyper, T. W. Swiddens under transition: Consequences of agricultural intensification in the Amazon. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2016, 218, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padoch, C.; Coffey, K.; Mertz, O.; Leisz, S. J.; Fox, J.; Wadley, R. L. The demise of Swidden in Southeast Asia? Local realities and regional ambiguities. Geografisk Tidsskrift 2007, 107, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerkasem, K.; Lawrence, D.; Padoch, C.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; Ziegler, A. D.; Bruun, T. B. Consequences of swidden transitions for crop and fallow biodiversity in southeast asia. Human Ecology 2009, 37, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, D. L. Use of Tropical Rainforests by Native Amazonians. BioScience 1990, 40, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Lennox, G. D.; Ferreira, J.; Berenguer, E.; Lees, A. C.; Nally, R. Mac; et al. Anthropogenic disturbance in tropical forests can double biodiversity loss from deforestation. Nature 2016, 535, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, C.; Veríssimo, A.; Mattos, M. M.; Brandino, Z.; Guimarães Vieira, I. C. Social, economic, and ecological consequences of selective logging in an Amazon frontier: the case of Tailândia. Forest Ecology and Management 1991, 46, 243–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkin, A.; Bolker, B.; Peña-Claros, M.; Licona, J. C.; Putz, F. E. Fates of trees damaged by logging in Amazonian Bolivia. Forest Ecology and Management 2015, 357, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G. P.; Knapp, D. E.; Broadbent, E. N.; Oliveira, P. J. C.; Keller, M.; Silva, J. N. Ecology: Selective logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Science 2005, 310, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, B. M.; Levis, C. Human-food feedback in tropical forests. Science 2021, 372, 1146–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, B. M.; Staal, A. Feedback in tropical forests of the Anthropocene. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 5041–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovac, C. C.; Junqueira, A. B.; Crouzeilles, R.; Peña-Claros, M.; Mesquita, R. C. G.; Bongers, F. The role of land-use history in driving successional pathways and its implications for the restoration of tropical forests. Biological Reviews 2021, 96, 1114–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suding, K. N.; Gross, K. L.; Houseman, G. R. Alternative states and positive feedbacks in restoration ecology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2004, 19, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, B. M.; Staal, A.; Jakovac, C. C.; Hirota, M.; Holmgren, M.; Oliveira, R. S. Soil erosion as a resilience drain in disturbed tropical forests. Plant and Soil 2019, 450, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G. S. A Review of Social Dilemmas and Social-Ecological Traps in Conservation and Natural Resource Management. Conservation Letters 2018, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M. L. Principless for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems; 2015.

- Folke, C. Resilience (Republished). Ecology and Society 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.; Xepapadeas, T.; Crépin, A. S.; Norberg, J.; De Zeeuw, A.; Folke, C.; et al. Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: Modeling and policy implications. Environment and Development Economics 2012, 18, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 42. Ministère de L’Environnement. Plan de Gestion Parc National Naturel Macaya.

- Sergile, F. E.; Woods, C. A.; Paryski, P. E. Final Report of the Macaya Biosphere Reserve Project; Gainesville, 1992.

- 44. Le Moniteur. Décret du 4 Avril 1983 déclarant “Parcs Nationaux Naturels” les aires entourant le morne La Visite e le morne Macaya entourant le Pic Macaya au massif de La Hotte. Le Moniteur, 1983.

- Hedges, S. B.; Cohen, W. B.; Timyan, J.; Yang, Z. Haiti’s biodiversity threatened by nearly complete loss of primary forest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 201809753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robart, G. Végétation de la République d’Haïti, Université scientifique et médicale de Grénoble, 1984.

- 47. USAID. Vulnérabilité Environnementale En Haïti: Conclusions et Recommandations.

- Crausbay, S. D.; Martin, P. H. Natural disturbance, vegetation patterns and ecological dynamics in tropical montane forests. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzolla Gatti, R.; Castaldi, S.; Lindsell, J. A.; Coomes, D. A.; Marchetti, M.; Maesano, M.; et al. The impact of selective logging and clearcutting on forest structure, tree diversity and above-ground biomass of African tropical forests. Ecological Research 2014, 30, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 50. Unesco. La Hotte Biosphere Reserve, Haiti.

- Hansen, M. C.; Potapov, P. V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S. A.; Tyukavina, A.; et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, C. A.; Ottenwalder, J. A. The Natural History of Southern Haiti; Florida Museum of Natural History: Gainesville, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sergile, F. Arbres et Arbustes de Macaya; Florida Museum of Natural History: Gainesville, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 54. AVSI. Analyse et Étude Du Contexte Socio-Économique et Environnementale Du Parc Macaya, Haïti, 2012.

- 55. PNUD. Rapport OMD 2013, Haïti: Un Nouveau Regard, 2014.

- Leutner, B.; Wegmann, M. Pre-processing Remote Sensing Data. In Remote Sensing and GIS for Ecologists: Using Open Source Software. Wegmann, M., Leutner, B., Dech, S., Eds.; Pelagic Publishing: UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J. W.; Haas, R. H.; Schell, J. A.; Deering, D. W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS (Earth Resources Technology Satellite). Proceedings of 3rd Earth Resources Technology Satellite Symposium; Greenbelt; 1973; pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- McFEETERS, S. K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, B.; Verbesselt, J.; Kooistra, L.; Herold, M. Robust monitoring of small-scale forest disturbances in a tropical montane forest using Landsat time series. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. O.; Malhi, Y.; Aragão, L. E. O. C.; Ladle, R.; Arai, E.; Barbier, N.; et al. Remote sensing detection of droughts in Amazonian forest canopies. New Phytologist 2010, 187, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. 2017.

- Horning, N.; Leutner, B.; Wegmann, M. Land Cover or Image Classification Approaches. In Remote Sensing and GIS for Ecologists: Using Open Source Software. Wegmann, M., Leutner, B., Dech, S., Eds.; Pelagic Publishing: UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2022.

- Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, V: for Statistical Computing, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. The R Journal 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R. J.; Etten, J. van. raster: Geographic analysis and modeling with raster data. 2012.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag: New York 2016.

- Dunnington, D.; Thorne, B.; Hernangómez, D. Spatial Data Framework for ggplot2. 2022.

- Allaire, J. J.; Ellis, P.; Gandrud, C.; Owen, J.; Russell, K.; Rogers, J.; et al. Package ‘networkD3.’ 2022.

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E. F. Global Forest Transition: Prospects for an End to Deforestation; 2011; Vol. 36. [CrossRef]

- Costa, R. L.; Prevedello, J. A.; de Souza, B. G.; Cabral, D. C. Forest transitions in tropical landscapes: A test in the Atlantic Forest biodiversity hotspot. Applied Geography 2017, 82, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R. The scale of forest transition: Amazonia and the Atlantic forests of Brazil. Applied Geography 2012, 32, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X. P.; Hansen, M. C.; Stehman, S. V.; Potapov, P. V.; Tyukavina, A.; Vermote, E. F.; et al. Global land change from 1982 to 2016. Nature 2018, 560, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Environmental Eduaction for Community Participation in Conservation of Macaya, Massif de la Hotte Key Biodiversity Area. Available online: https://www.cepf.net/grants/granteeprojects/environmental-education-community-participation-conservation-macaya-massif.

- Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Ecosystem Threat Assessment and Protected Area Strategy for the Massif de la Hotte Key Biodiversity Area, Phase 2. Available online: https://www.cepf.net/grants/grantee-projects/ecosystem-threatassessment-and-protected-area-strategy-massif-de-la-hotte-0.

- Tarter, A.; Freeman, K. K.; Sander, K. A History of Landscape-Level Land Management Efforts in Haiti: Lessons Learned from Case Studies Spanning Eight Decades; 2016.

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 78. MDE. Sixième Rapport National Sur La Biodiversité d’Haïti.

- Thompson, J.; Brokaw, N.; Zimmerman, J. K.; Waide, R. B.; Edwin, M.; Iii, E.; et al. Land Use History, Environment, and Tree Composition in a Tropical Forest. Ecological Applications 2002, 12, 1344–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boose, E. R.; Serrano, M. I.; Foster, D. R. Landscape and regional impacts of hurricanes in Puerto Rico. Ecological Monographs 2004, 74, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T. H.; Heard, M. S.; Isaac, N. J. B.; Roy, D. B.; Procter, D.; Eigenbrod, F.; et al. Biodiversity and Resilience of Ecosystem Functions. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2015, 30, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzolla Gatti, R.; Castaldi, S.; Lindsell, J. A.; Coomes, D. A.; Marchetti, M.; Maesano, M.; et al. The impact of selective logging and clearcutting on forest structure, tree diversity and above-ground biomass of African tropical forests. Ecological Research 2015, 30, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Folke, C.; Nyström, M.; Peterson, G.; Bengtsson, J.; Walker, B.; et al. Response diversity, ecosystem change, and resilience. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2003, 1, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvério, D. V.; Brando, P. M.; Bustamante, M. M. C.; Putz, F. E.; Marra, D. M.; Levick, S. R.; et al. Fire, fragmentation, and windstorms: A recipe for tropical forest degradation. Journal of Ecology 2019, 107, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nes, E. H.; Staal, A.; Hantson, S.; Holmgren, M.; Pueyo, S.; Bernardi, R. E.; et al. Fire forbids fifty-fifty forest. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hurricane | Date | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Gilbert | September/88 | 5 |

| Georges | September/98 | 4 |

| Lili | September/02 | 4 |

| Ivan | September/04 | 5 |

| Dean | August/07 | 5 |

| Sandy | October/12 | 3 |

| Matthew | October/16 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).