1. Introduction

The rapid worldwide increase of jellyfish has led to a highly advantageous fishery and an unconventional source for traditional fishermen, mainly owing to the decay of conventional fishing resources and their affordable cost [

1]. This decay has considerably affected the traditional fishermen’s financial stability, forcing them to face severe economic difficulties [

2]. Conversely, jellyfish fisheries represent a substantial opportunity for improving the economic conditions of these fishermen [

3], especially with the production of bioactive peptides derived from jellyfish collagens [

4].

According to systematic studies of jellyfish species, the valid species within the jellyfish family in the American Continent are

Stomolophus meleagris [

5] and

Stomolophus fritillaria [

6]. In the southern Gulf of California, specifically in the Upper Gulf of California, there resides an as-yet-undefined species of

Stomolophus jellyfish, known as

Stomolophus sp. 2, commonly referred to as the blue cannonball jellyfish [

7].

Stomolophus sp. 2 offers considerable potential profit for those highly dependent on fishing activities [

3]. Moreover, the jellyfish harvesting has become an economic alternative for coastal fishermen in central and southern Sonora, with a production about 57,000 tons reported in 2024 [

8]. Their extracted collagen shows notable antioxidant capacity [

9]. Its gelatine has been found to possess antimutagenic activity [

10], adding to the potential health benefits of jellyfish collagen hydrolysates.

Jellyfish collagen hydrolysates hold significant promise as novel sources of bioactive peptides, offering a range of health benefits such as antioxidants, antihypertensives, antimicrobials, and antiproliferative effects [

11]. These antioxidant peptides, typically composed of 2 to 20 amino acids and with molecular weights below 3,000 Da, have been the focus of increasing scientific interest [

12]. Conversely, jellyfish enzymatic hydrolysis produces peptides with molecular weights greater than 8,000 Da [

13]. The molecular weight of marine protein hydrolysates is a crucial factor in obtaining protein hydrolysates with bioactive peptides [

14].

An alternative method for generating peptides with specific molecular weights is membrane separation, a technique widely used in industry due to its economical nature. The ultrafiltration membrane separation process has been shown to enhance the specific bioactivity of jellyfish hydrolysates [

15,

16,

17]. However, despite these research efforts, there is a significant lack of information about the application of ultrafiltration to improve the antioxidant and antimutagenic properties of

Stomolophus sp. 2 mesoglea collagen hydrolysates. This gap in knowledge underscores the urgency and importance of our research. Furthermore, according to our understanding, the antimutagenic activity and potential genotoxic effects of

Stomolophus sp. 2 collagen hydrolysates have not been investigated following ultrafiltration, further highlighting the need for our study.

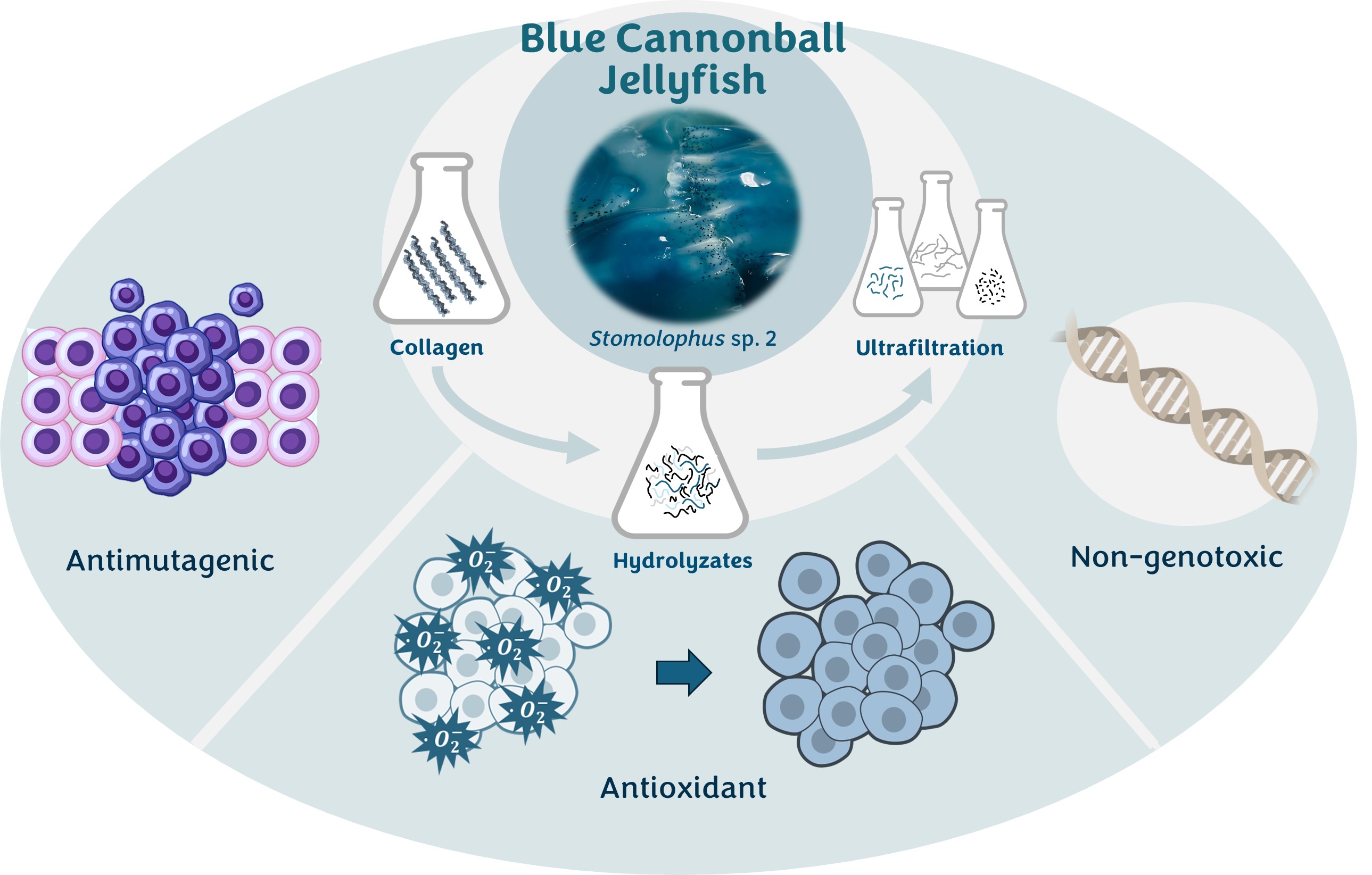

The present work considers blue cannonball jellyfish (Stomolophus sp.2) mesoglea as a source of collagen. It aims to document the bioactivity (antioxidant and antimutagenic), genotoxicity, and antioxidant storage stability over time of the fractions obtained by ultrafiltration after enzymatic hydrolysis of jellyfish collagen with Alcalase. Additionally, the bioactive peptides encoded in Stomolophus sp. 2 mesoglea’s collagen proteomes were predicted in silico.

2. Results

2.1. Collagen and Hydrolysates Yield and Properties

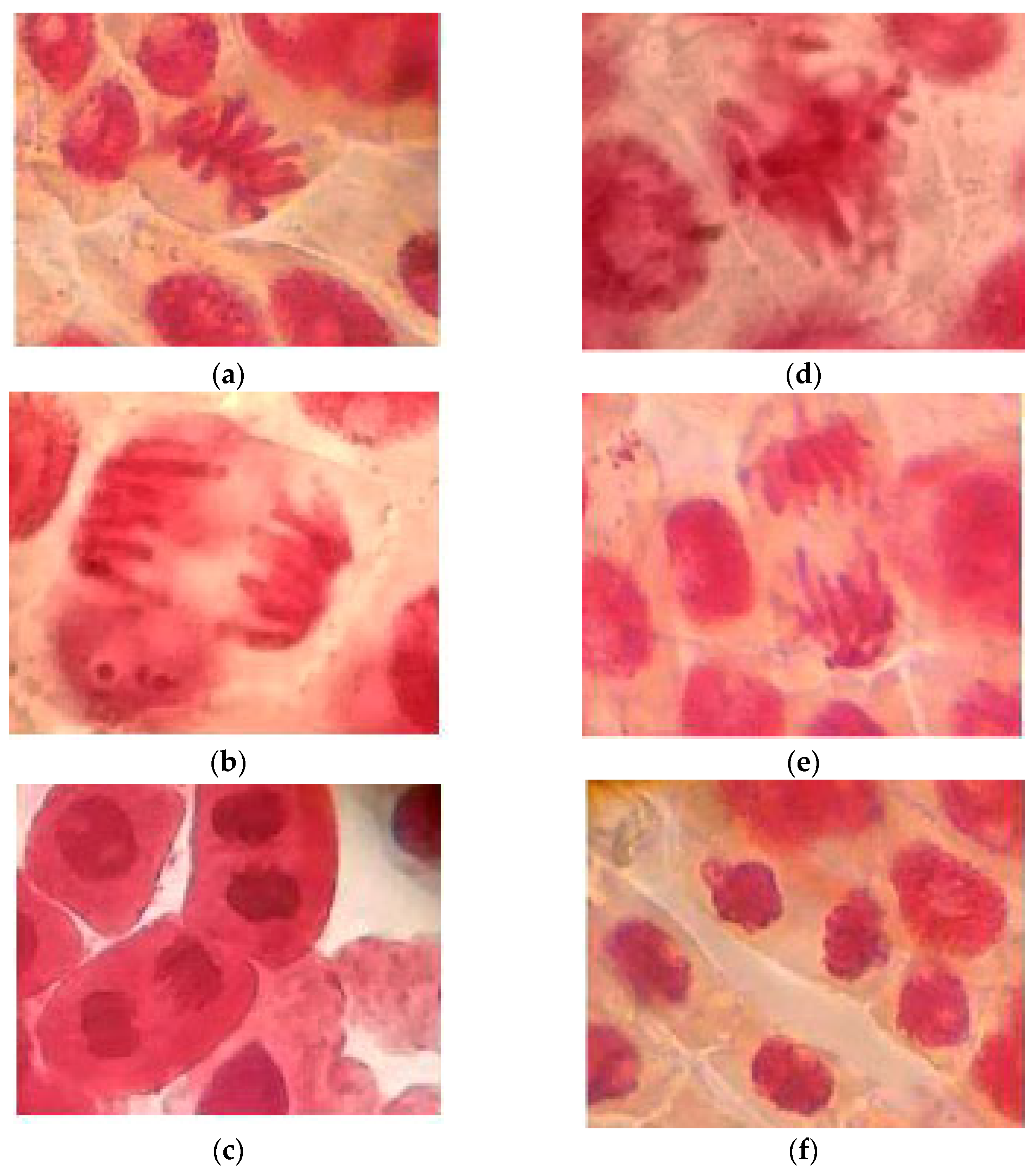

The percentage of collagen after extraction, estimated from its hydroxyproline content (5.7 ± 0.38 g/100 g), was 60.3 ± 2.2 % with a DH value of 27.2 ± 1.3 %. The hydrolysate yield (expressed as grams of dry hydrolysates per 100 g of collagen) was 11.08 %. These hydrolysates at 100 ppm show a low adverse effect on the chromosomes (3.4 % of abnormalities). Different phases of normal and abnormal mitosis are shown in

Figure 1. Based on these images, it was determined whether the hydrolysates or fraction three samples exerted harmful effects to the chromosomes, as discussed later.

Antioxidant values (

Table 1) showed that the obtained hydrolysates exhibited the ability to undergo single electron transfer (SET) mechanisms against the ABTS radical, as well as hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) capacity against the AAPH radical, and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). Moreover, these hydrolysates effectively inhibited the mutation induced by AFB

1 on

Salmonella typhimurium strain TA100, with an inhibition percentage greater than 50 % (

Table 2), which could be considered as a moderate inhibition of the control mutagen [

18].

The hydrolysates obtained were rich in glycine, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, arginine, and proline, accounting for 23, 13, 10, 9, and 9 % of the total amino acid composition, respectively. The amino acids with hydrophobic chains, glycine, alanine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, proline, phenylalanine, and methionine, represent about 49 % of jellyfish hydrolysates.

2.2. Fractions Characterization

2.2.1. Antioxidant Capacity

The membrane ultrafiltration process applied to hydrolysates allowed the separation of the peptides based on their molecular weight (F1, F2, F3). The three obtained hydrolysate peptide fractions showed the capacity to donate hydrogen atoms and electrons, reduce Fe

3+ to Fe

2+, and scavenge oxygen-derived radicals (

Table 1). Among them, the most significant antioxidant activity (

p < 0.05) was detected in the fraction with < 3 kDa (F3). As expected, low-molecular-weight peptides exhibit higher antioxidant activity [

19].

2.2.2. Antimutagenic Capacity

The highest antimutagenic activity, measured as the percentage of inhibition of

S. typhimurium TA100 revertants/plate, was detected in F3 even at the lowest concentration (

Table 2), which was consistent with the antioxidant activity detected. Therefore, the peptides present in the obtained fractions may protect against the type of mutation induced by the TA100 strain, base substitutions or frameshift mutations [

20].

2.2.3. Genotoxicity of Hydrolysates and Fraction < 3 kDa

The JCH and F3 did not cause a change in the frequencies of different cell stages, and their treatments did not induce a wide range of mitotic abnormalities as compared to the sodium aside in the root tip of

Allium fistulosum (

Figure 1). The mitotic index (MI) of

A. fistulosum root was not significantly (p > 0.05) decreased by JCH and F3 (

Table 3). The level of abnormalities and MI of JCH and F3 indicate that these compounds are not genotoxic at 100 ppm, respectively [

21].

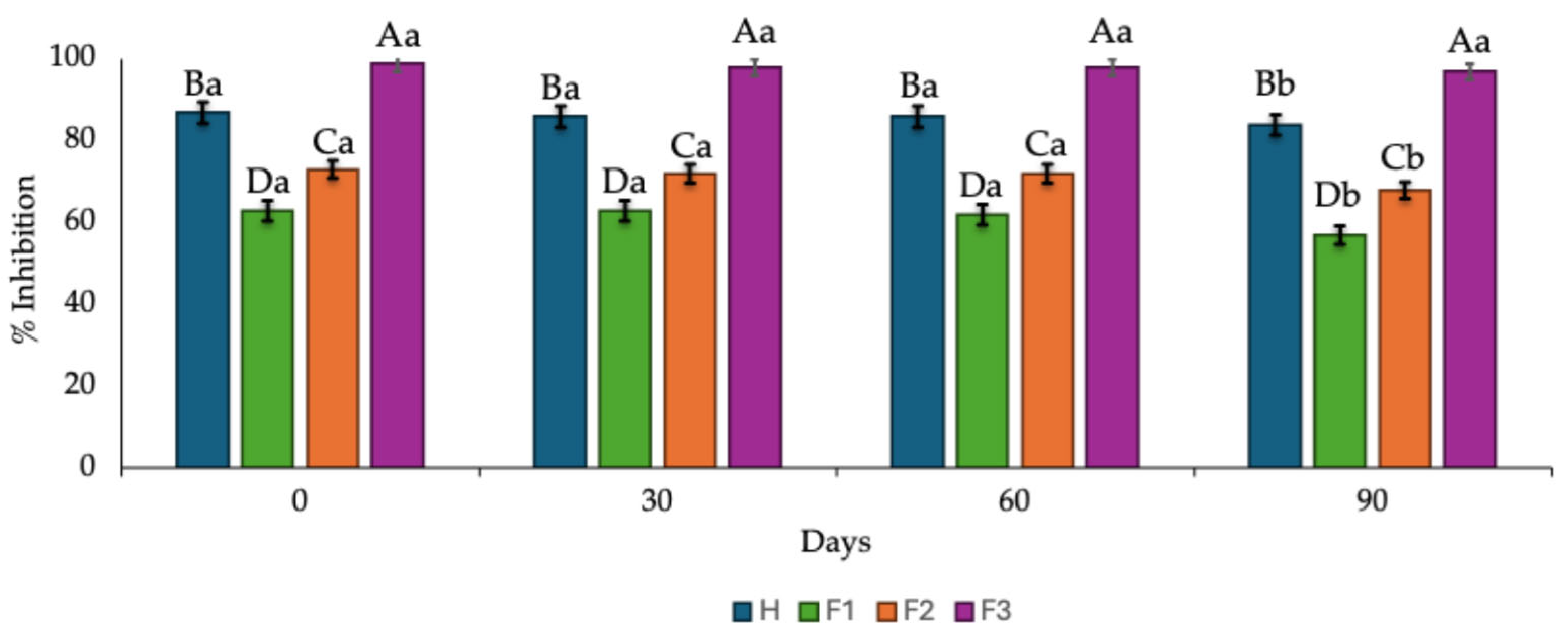

2.2.4. Effect of the Storage Time on the Antioxidant Activity of Hydrolysates and Fractions

The effect of storage time (90 days) at 4 °C on the ability to scavenge ABTS radicals by the hydrolysates and fractions is shown in

Figure 2. Fraction F3 (< 3 kDa MW) remained more stable during the 90 days of storage, showing a slight decrease in its ability to quench the ABTS radical. In contrast, a gradual yet significant (

p < 0.05) decline after 60 days of storage was observed in the hydrolysates and fractions F1 (> 10 kDa MW) and F2 (3 - 10 kDa).

2.2.5. Bioactive Peptides Identified by Informatics Analysis

The proteins identified from jellyfish protein extracts using nano-LC-MS/MS were derived from 3,086 identified spectra (PSM), which included 707 distinct peptides corresponding to 10 proteins. Notably, collagen was identified among the proteins. The collagen characterized in this study was type IV, encompassing 15 unique peptides (

Table 4).

Bioactive peptides remain inactive while embedded in proteins and exhibit their activity once released through enzymatic action. In this study, the bioactive peptides in the collagenous extracts of

Stomolophus sp. 2 mesoglea were predicted using Peptide Ranker software (

http://distelldeep.ucd.ie/PeptideRanker). The analysis revealed that 100% of the identified peptides had a molecular weight below 3,000 Da, with 80% falling within the range of 1,000 – 2,215 Da and 20% below 1,000 Da. Among the 15 unique peptides identified in the collagen of

Stomolophus sp. 2 through bioinformatic analysis, ten peptides scored above 0.5 [

22,

23], indicating a high probability of bioactivity (

Table 4).

3. Discussion

It is considered that hydroxyproline content is the best means for estimating the percentage of collagen. In the present work, the collagen content detected in

Stomolophus sp. 2 was comparable to values previously reported for another jellyfish species, as

Rhopilema esculentum (65%) [

25] and

Rhopilema pulmo (61.15%) [

26].

The in vitro Ames antimutagenic assay is a biological assay that uses a mutant strain of

Salmonella typhimurium to evaluate whether a substance can prevent or reduce the mutagenicity induced by a mutagenic agent. Since cancer is often linked to DNA damage, the test also serves as a rapid assay to estimate the anticarcinogenic potential of a compound. If the compound is antimutagenic, it reduces the frequency of mutations (revertants) observed in the bacteria compared to the control, indicating that the substance possesses protective properties against genetic damage [

27]. The Ames test showed that the

Stomolopus sp. 2’s hydrolysate contained peptides with antimutagenic effects, capable of inhibiting mutations or DNA damage associated with carcinogenesis. These peptides present in the hydrolysates could act as antioxidants and cell regulators, making them a promising alternative for disease prevention. However, more studies are required to confirm this.

The antioxidant and antimutagenic activities detected in the obtained hydrolysates could be attributed to the presence of some amino acids, such as glycine and proline. Glycine acts as an indirect antioxidant by being a component of glutathione, a potent antioxidant in the body. It also has antimutagenic properties by suppressing the formation of free radicals and stabilizing cell membranes, thus helping to protect against cellular damage and oxidative stress [

28]. Proline, on the other hand, can act as a compatible osmolyte to protect cells, and reduces oxidative damage caused by environmental factors and antimutagenic agents in various organisms [

29].

In vitro assays assess the ability of a group of compounds to interact with a free neutral radical that possesses an unpaired electron in one of its orbitals [

30]. Free radicals are unstable and highly reactive; when they seek stability through electron uptake, they can initiate chain reactions that damage cellular structures, including membranes, lipids, and proteins [

31]. Therefore, the peptides present in the fractions obtained from collagen hydrolysates extracted from jellyfish, by presenting antioxidant properties, may help to protect cells present in organisms against oxidative stress by scavenging free radicals and enhancing natural antioxidant defenses. It has been shown that peptides extracted from jellyfish collagen can increase the levels of superoxide dismutase [

12], a key cellular antioxidant, and reduce reactive oxygen species [

32].

The higher antioxidant and antimutagenic capacity of the fraction with molecular weight below 3 kDa may be attributed to its exposure to a hydrophobic surface during the fractionation process [

33]. This fraction could have more amino acids exposed to the surface, enhancing their interaction with free radicals, converting them into more stable products [

33] protecting the cells against oxidative stress more efficiently. However, an amino acid profile of each fraction should be developed to confirm this. Moreover, the peptides’ efficiency in reacting with radicals as electron donors and preventing radical chain reactions is strongly affected by their amino acid sequence.

The stability of peptides is considered crucial to establishing their application as functional ingredients [

34]. The results obtained in this study indicated that both the hydrolysates and fractions F1 and F2 maintained more than 80% of their antioxidant activity, while fraction F3 retained almost 100% of this activity. The slight decrease detected in the antioxidant capacity of the hydrolysates and fractions F1 and F2 can be attributed to peptide modifications such as dehydration, glycation, and oxidation of aromatic rings, which alter their structure and consequently their bioactivity [

35]. The apparent greater stability of fraction F3 could be attributed to the type of secondary structure formed by its peptides, as well as to the sequence of its amino acids [

36]. It has been documented that the peptides present in hydrolyzed proteins can form both b-sheet and a-helix structures, with the b- structure being the most stable [

36]. Likewise, if amino acids such as aspartic acid, glutamic acid or arginine are found in the peptide sequence, peptides will be more susceptible to moisture absorption [

37].

Previous research has indicated that jellyfish collagen is chemically simple, contributing to its versatile and adaptable tissue properties. As a result, it has been classified as collagen type 0 [

38]. This type of collagen exhibits a chemical composition similar to that of various collagen classes [

38] and shares numerous functions with more specialized collagens [

39], including antioxidant properties [

11], through the Peptide Ranker program and the ranks assigned to the probability of specific peptide of being bioactive [

22]. The eight peptides identified with a substantial likelihood of bioactivity, containing fewer than 20 residues with the presence of amino acids considered crucial for the antioxidant activities of peptides [

40]: glycine, proline, leucine, alanine, phenylalanine, and valine. Therefore, the predicted peptides present in the

Stomolophus sp.2 collagen could be responsible for the bioactive properties detected in the obtained hydrolysates and fractions. Nevertheless, to ensure this, studies integrating in vitro and in silico techniques are necessary to evaluate and confirm their potential antioxidant and antimutagenic activity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Samples and Chemicals

Sixty-five jellyfish Stomolophus sp. 2 specimens from Kino Bay (28°43’N/111°54’W, 24-36°C) were collected. The jellyfish organisms’ measures were weight 0.45 to 1.1 kg and length 12-17 cm. Specimens stored in an ice bed system were transported to the laboratory, and mesoglea was gathered from the organisms. All chemicals used were of analytical reagent grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

4.2. Collagen Extraction

The extraction of collagen followed the procedure described previously [

9]. Mesoglea jellyfish were cut into small pieces (100 g), and collagen was obtained with 0.1 M NaOH (1:5 w/v) and mechanically stirred for 24 h. After centrifugation (39,200 x g, 4 °C, 90 min), the pellet was sequentially rinsed until the pH dropped to seven and freeze-dried. After that, it was treated with 0.5 M CH

3COOH (1:5 w/v) and pepsin (10 mg/sample in 0.5 M CH

3COOH; 1:5 w/v). At each step, after stirring for 24 h, the samples were centrifuged (39,200 x g, 4 °C, 15 min). Finally, the samples dialyzed at 4 °C against water (cellulose membrane 50 kDa molecular weight cut-off) were lyophilized and stored at -80°C for further analyses. The collagen present in the sample was determined by its hydroxyproline (Hyp) and protein content. Crude protein was quantified with a LECO FP-2000 Nitrogen Protein Analyzer (Method 9993.13, AOAC. 2000. “Official Methods of Analysis” 17th ed. Association of Analytical Chemists. Washington, DC.). Hyp was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (RP–HPLC, Agilent Technologies) [

41].

4.3. Preparation of Enzymatic Hydrolysates

Hydrolysates were produced by a commercial enzyme system (Alcalase) according to the method described previously [

42] with some modifications. The pepsin solubilized collagen (200 mg) was dissolved in a 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer of pH 7.5 (0.4 mg protein/mL). The beakers were placed in a 55 °C water bath under constant mixing for 5 h. The enzyme-substrate ratio (E/S) was 0.2 % (w/w). The enzyme was inactivated by heating the sample to 95 °C for 15 min. The supernatants obtained after centrifugation (6000 x

g, 15 min) were considered to contain hydrolysates (JCH). The freeze-dried samples were stored at -80 °C for further assays.

4.4. Membrane Ultrafiltration

The JCH was dissolved in deionized water (1 mg/mL) and fractionated by ultrafiltration through an ultrafilter (Amicon Stirred Cell, Model 8200) equipped with a 10 kDa membrane into one fraction: F1, composed of peptides with molecular weights >10 kDa, The F3 was subjected to ultrafiltration using a 3 kDa membrane and fractionated into two fractions: F2 consisting of peptides from molecular weight >3 kDa and <10 kDa, and F3, comprising peptides of molecular weight <3 kDa. The fractionated temperature was 4 °C, and the pressure was 0.2 MPa. The collected fractions were freeze-dried and stored at -80 °C.

4.5. Analysis

4.5.1. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH)

DH was established by analysing free amino groups by reaction with the

O-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) reagent [

43]. The serine was employed as a standard. The a, b, and htot values were 1.00, 0.40, and 8.6, respectively.

4.5.2. Amino Acid Profile of Hydrolysates

The amino acid content of JCH was determined by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Hewlett-Packard RP-HPLC, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Freeze-dried samples (100 mg) were hydrolysed under reduced pressure (6 M HCl, 150°C, 6 h). The hydrolysate residues, after centrifugation, were neutralised in 2 mL of 4 M NaOH and filtered using a cellulose-acetate syringe filter unit (0.2 mm). After filtration, the samples were mixed with potassium borate buffer (pH 10.4) and

O-phthaldialdehyde (1:1, v/v) and applied to the RP-HPLC system. The chromatogram recordings and integrations were performed using ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies). Fluorescence was measured at wavelengths of 330 nm (excitation) and 418 nm (emission) [

44]. Analysis was performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as g/100 g sample.

4.5.3. Antioxidant Activity of Hydrolysates and Fractions

Three assays evaluated the in vitro antioxidant activity of JCH and its fractions at a concentration of 0.75 mg/mL, and the results were expressed as mmol TE (Trolox equivalent)/g.

The sample scavenging capacity to reduce the 2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation (ABTS

●+) was measured [

45]. ABTS in water (7 mmol) was dissolved in 2.45 mmol potassium persulfate (dark room, 25 °C, 16 h) to produce the ABTS

●+. Then, 20 μL aliquot samples were added to 980 μL of ABTS

●+ diluted with methanol (Abs

734nm = 0.70), and the decrease in absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a 96-well microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) capacity of the samples was adapted to microplate equipment and carried out according to previous studies [

46]. The FRAP working solutions comprised of 300 mM acetic acid–sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 20 mM FeCl3•6 H2O, and 10 mM 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ) in 40 mM HCl (10:1:1 ratio). The mixture of FRAP working solution (280 mL) and the sample (20 mL) was incubated at 25°C in the dark for 30 min before its absorbance was recorded at 638 nm using a microplate reader.

Samples’ capacity to quench the oxygen radicals produced by the 2,2’-azobos(2-amidinopropane) (AAPH) was evaluated by the ORAC assay [

47], which was the third chemical assay. The inhibition of fluorescence decay was evaluated over 60 min at 37°C at 485 nm (excitation) and 520 nm (emission) in a Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) after mixing 100 mL of the samples with a mixture of 75 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.3 (1.7 mL), 0.36M AAPH (0.1 mL), and 0.048 mM fluorescein (100 mL).

4.5.4. Antimutagenic Activity of Hydrolysates and Fractions

Salmonella/microsome assay [

48] was employed to evaluate the antimutagenic potential of hydrolysates and fractions. Salmonella tester strain TA100 was used with bioactivation (S9, Aroclor 1254-induced, Sprague-Dawley male rat liver in 0.154 M KCl solution). Bacteria reproduction (2×109 cells/ml, overnight culture, 37 °C) was developed in a nutrient broth. The mutagen employed was Aflatoxin B

1 (with S9 mix) (500 ng/mL). The assay involved 100

μL of hydrolysates (0, 0.5, and 5 mg/mL) and fractions (0, 0.002, 0.02, 0. 2, and 2.0 mg/mL) in test tubes. Then, each tube was mixed with bacteriological agar containing histidine and biotin, bacterial culture (100

μL), and S9 mix (500

μL). 10% DMSO (100 μL) without AFB

1 was used as a negative control. The mixture obtained was transferred to minimal agar plates. The plates were incubated (37 °C, 48 h), and each plate’s revertant bacterial colonies were counted. The inhibition rate for mutagenic activity was calculated according to Equation 1.

where T is the number of revertant in presence of AFB

1 and test samples plates, and M is the number of revertant per plate in the mutagen without extras, subtracting the spontaneous revertant from the numerator and denominator. A > 40% was considered as strong antigenotoxicity, 25–40% moderate antigenotoxicity, and

25% no antigenotoxicity (Owen et al., 2004). Each dose was tested in triplicate.

4.5.6. Storage Antioxidant Stability of Hydrolysates and Fractions

For three months, freeze-dried hydrolysates and fractions (about 10 mg) were placed in Eppendorf tubes and stored in a 4°C refrigerator to explore their stability and ability to scavenge the radical ABTS.

4.5.5. Genotoxicity Test of Hydrolysate and Fraction 3

Onions (Allium cepa) were allowed to germinate by immersion in distilled water and stored in the dark at 25 ± 2°C. Onions roots about 5 cm long were used for testing. The onion roots were treated with hydrolysate and F3 samples at 50 and 100 ppm concentrations for 24 h. The control group was treated with distilled water. The root tips were dehydrated (45 min) in a 3:1 (v/v) ethanol–acetic acid solution, then fixed in 1 N hydrochloric acid (2 min, 60 °C). After that, the samples were stained with orcein for one minute and finally squashed. The mitotic cells were observed and counted with a microscope.

4.5.7. Nano LC-MS/MS Analysis

The collagen sample was dissolved and identified with a nano LC-MS/MS platform (Ultimate 3000 nano-UHPLC system and Orbitrap Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer with Nanospray Flex Ion Source, Thermo Scientific) as previously reported [

10]. The pepsin protein extracts were poured into a C18 SPE column (Thermo Scientific) with 0.1% formic acid to remove the salt, and 1 mg of the sample was loaded into the Nanoflow UPLC. The MS/MS conditions were set as follows: scan (300 – 1,650 m/z, resolution 60,000 at 200 m/z, 3e6; operated in Top 20 mode (resolution 15,000 at 200 m/z; automatic gain control target 1e5; maximum injection time 19 ms; normalized collision energy 28%; and an isolation window of 1.4 Th); and charge state exclusion parameters set to unassigned, 1, > 6, and a dynamic exclusion of 30 s. Raw MS files were analysed and searched against the jellyfish protein database based on the species of the samples using PEAKS Studio 8.5. The parameters were set as follows: the protein modifications were carbamidomethylation (fixed) and methionine oxidation (variable), and the enzyme specificity was pepsin. There were two maximum missed cleavages; the precursor and ion mass tolerance were 10 ppm and 0.5 Da, respectively.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

The statistical design applied to the chemical characterization of the jellyfish collagen hydrolysates and fractions was used to minimize variation in the replicates. Data (n = 3) obtained from the biological activities were subjected to the ANOVA method (p < 0.05) to investigate differences in variance using the SPSS® program (SPSS Statistical Software, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation out of three determinations. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between the results were identified using the Tukey test.

5. Conclusions

The hydrolysates derived from jellyfish collagen demonstrated notable in vitro antioxidant and antimutagenic properties while showing no clastogenic effects. Following the ultrafiltration process, the antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of the hydrolysates were enhanced; however, clastogenicity remained unaffected. The highest bioactivity observed in fractions with a molecular weight of less than 3.0 kDa is likely attributed to the presence of peptides that aid in scavenging free radicals and blocking reactive oxygen species. These findings indicate that low molecular weight hydrolysate peptide fractions from jellyfish collagen warrant further investigation for purification and potential application as a bioactive food supplement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.E.-B and W.T-.A.; methodology, B. del S. V.-U., L.E. H-A., J.E.Ch.-H., I.M. W.T.-A., J.M.E.-B.; software, B. del S. V.-U. and J.M. E.-B.; validation, J.M.E.-B., I.M., and W.T.-A.; formal analysis, B. del S., V.-U., L.E. H.-A., J.E.Ch.-H.; investigation, J.M.E.-B., W.T.A., I.M., L.E. H.-A., and J.E. Ch.-H; resources, J.M.E.-B.; data curation, B. del S. V.-U., W.T.-A., L.E.H.-A., I.M., J.E.Ch.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, B. del S. V.-U., L.E. H-A, and J.E. Ch.-H; writing—review and editing, J.M. E.-B., W.T.-A., L.E. H-A, I.M., and J.E. Ch.-H.; visualization, J.M. E.-B., W.T.-A., L.E. H-A, I.M., and J.E. Ch.-H.; supervision, W.T.-A., I.M., and J.M. E.-B.; project administration, J.M.E.-B.; funding acquisition, J.M.E.-B. and W.T.-A.

Funding

This research was funded by the Secretary of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHTI) via the Mexican Government, grant number CBF-2025-I-4163.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available in the article. Further information is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Secretary of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHTI) via the Mexican Government for the scholarship given to Villalba-Urquidy and Hernández-Aguirre, and to Marco Antonio Ross Gamez for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| JCH |

Jellyfish collagen hydrolysates |

| F1 |

Fraction molecular weight > 10 kDa |

| F2 |

Fraction 10 kDa > molecular weight > 3 kDA |

| F3 |

Fraction molecular weight > 3 kDa |

| ABTS |

2,2’-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic-acid) |

| FRAP |

Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| AAPH |

2,2’-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride |

| FRAP |

Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| SET |

Single electron transfer |

| HAT |

Hydrogen atom transfer |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| UHPLC |

Ultra-High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| ORAC |

Oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

References

- Cisneros-Mata, M.A.; Mangin, T.; Bone, J.; Rodriguez, L.; Smith, S.L.; Gaines, S.D. Fisheries Governance in the Face of Climate Change: Assessment of Policy Reform Implications for Mexican Fisheries. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0222317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotz, L.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Cisneros-Mata, M.Á. The Race for Jellyfish: Winners and Losers in Mexico’s Gulf of California. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salinas, L.C.; López-Martínez, J.; Morandini, A.C. The Young Stages of the Cannonball Jellyfish (Stomolophus Sp. 2) from the Central Gulf of California (Mexico). Diversity 2021, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, G.; Martinez, K.A.; Martín, J.; Reyes, F.; D’Ambra, I.; Lauritano, C. Jellyfish as an Alternative Source of Bioactive Antiproliferative Compounds. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarms, G.; Morandini, A. World Atlas of Jellyfish; Dölling und Galitz Verlag.: Aamburg, Germany, 2019; p. 816. [Google Scholar]

- Banha, T.N.S.; Morandini, A.C.; Rosário, R.P.; Martinelli Filho, J.E. Scyphozoan Jellyfish (Cnidaria, Medusozoa) from Amazon Coast: Distribution, Temporal Variation and Length–Weight Relationship. J. Plankton Res. 2020, 42, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastré-Velásquez, C.D.; Rodríguez-Armenta, C.M.; Minjarez-Osorio, C.; Re-Vega, E.D.L. Estado actual del conocimiento de la medusa bola de cañón (Stomolophus meleagris). EPISTEMUS 2022, 16, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagarhpa Favorece Gobierno de Sonora a Pescadores Con Asistencia Técnica y de Organización En El Golfo de Santa Clara. Available online: https://sagarhpa.sonora.gob.mx/acerca-de/acciones/favorece-gobierno-de-sonora-a-pescadores-con-asistencia-tecnica-y-de-organizacion-en-el-golfo-de-santa-clara (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- del S. Villalba-Urquidy, B.; Torres-Arreola, W.; Toro-Sánchez, C.L.D.; Medina, I.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Brauer, J.M.E.; del C. Santacruz-Ortega, H. Collagen Extracts from Blue Cannonball Jellyfish (Stomolophus Meleagris): Antioxidant Properties, Chemical Structure, and Proteomic Identification. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2025, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza-Espinoza, D.M.; Del Carmen Santacruz-Ortega, H.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M.; Aubourg, S.P.; Salazar-Leyva, J.A.; Rodríguez-Felix, F.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M. Chemical-Structural Identification of Crude Gelatin from Jellyfish (Stomolophus meleagris) and Evaluation of Its Potential Biological Activity. Fishes 2023, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarelli, P.G.; Suh, J.H.; Pegg, R.B.; Chen, J.; Mis Solval, K. The Emergence of Jellyfish Collagen: A Comprehensive Review on Research Progress, Industrial Applications, and Future Opportunities. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 104206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Li, R.; Geng, H.; Xing, R.; Liu, S.; Li, P. Jellyfish Peptide as an Alternative Source of Antioxidant. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Hou, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B. Effects of Collagen and Collagen Hydrolysate from Jellyfish (Rhopilema esculentum) on Mice Skin Photoaging Induced by UV Irradiation. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, H183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soufi-Kechaou, E.; Derouiniot-Chaplin, M.; Ben Amar, R.; Jaouen, P.; Berge, J.-P. Recovery of Valuable Marine Compounds from Cuttlefish By-Product Hydrolysates: Combination of Enzyme Bioreactor and Membrane Technologies: Fractionation of Cuttlefish Protein Hydrolysates by Ultrafiltration: Impact on Peptidic Populations. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2017, 20, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raksha, N.; Halenova, T.; Vovk, T.; Kostyuk, O.; Synelnyk, T.; Andriichuk, T.; Maievska, T.; Savchuk, O.; Ostapchenko, L. Anti-Obesity Effect of Collagen Peptides Obtained from Diplulmaris antarctica, a Jellyfish of the Antarctic Region. Croat. Med. J. 2023, 64, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Jia, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Z.; Liu, C. Purification and Characterization of Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides from Jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, B. Production of the Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme (ACE)-Inhibitory Peptide from Hydrolysates of Jellyfish (Rhopilema esculentum) Collagen. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.W.; Haubner, R.; Würtele, G.; Hull, E.; Spiegelhalder, B.; Bartsch, H. Olives and Olive Oil in Cancer Prevention. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. Off. J. Eur. Cancer Prev. Organ. ECP 2004, 13, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Pan, B.S.; Chang, C.-L.; Shiau, C.-Y. Low-Molecular-Weight Peptides as Related to Antioxidant Properties of Chicken Essence. J. Food Drug Anal. 2005, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, J.; Alejandre-Durán, E.; Pueyo, C. Genetic Differences between the Standard Ames Tester Strains TA100 and TA98. Mutagenesis 1993, 8, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.; Kumar, V.; Roy, B.K. Assessment of Genotoxicity of Some Common Food Preservatives Using Allium cepa L. as a Test Plant. Toxicol. Rep. 2014, 1, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, C.; Haslam, N.J.; Pollastri, G.; Shields, D.C. Towards the Improved Discovery and Design of Functional Peptides: Common Features of Diverse Classes Permit Generalized Prediction of Bioactivity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Miao, J.; Chen, B.; Guo, J.; Ou, Y.; Liang, X.; Yin, Y.; Tong, X.; Cao, Y. Purification, Identification, and Antioxidative Mechanism of Three Novel Selenium-Enriched Oyster Antioxidant Peptides. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, K.R.; Baker, P.; Burlingame, A.L. Role of Accurate Mass Measurement (±10 Ppm) in Protein Identification Strategies Employing MS or MS/MS and Database Searching. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71, 2871–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felician, F.F.; Yu, R.-H.; Li, M.-Z.; Li, C.-J.; Chen, H.-Q.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, T.; Qi, W.-Y.; Xu, H.-M. The Wound Healing Potential of Collagen Peptides Derived from the Jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2019, 22, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkus, B.; Arslan, Y.E.; Bayrac, A.T.; Kantarcioglu, I.; Emregul, K.C.; Emregul, E. Development of a Novel Aptasensor Using Jellyfish Collagen as Matrix and Thrombin Detection in Blood Samples Obtained from Patients with Various Neurodisease. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 228, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słoczyńska, K.; Powroźnik, B.; Pękala, E.; Waszkielewicz, A.M. Antimutagenic Compounds and Their Possible Mechanisms of Action. J. Appl. Genet. 2014, 55, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-F.; He, C.-T.; Chen, Y.-T.; Hsieh, P.-S. Lipoic Acid Suppresses Portal Endotoxemia-Induced Steatohepatitis and Pancreatic Inflammation in Rats. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2013, 19, 2761–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcarea, C.; Laslo, V.; Memete, A.R.; Agud, E.; Miere (Groza), F.; Vicas, S.I. Antigenotoxic and Antimutagenic Potentials of Proline in Allium Cepa Exposed to the Toxicity of Cadmium Antigenotoxic and Antimutagenic Potentials of Proline in Allium Cepa Exposed to the Toxicity of Cadmium. Agriculture 2022, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumilaar, S.G.; Hardianto, A.; Dohi, H.; Kurnia, D. A Comprehensive Review of Free Radicals, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Overview, Clinical Applications, Global Perspectives, Future Directions, and Mechanisms of Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoid Compounds. J. Chem. 2024, 2024, 5594386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinic-Haberle, I.; Tovmasyan, A.; Roberts, E.R.H.; Vujaskovic, Z.; Leong, K.W.; Spasojevic, I. SOD Therapeutics: Latest Insights into Their Structure-Activity Relationships and Impact on the Cellular Redox-Based Signaling Pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 2372–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wan, S.; Liu, J.; Zou, Y.; Liao, S. Antioxidant Activity and Stability Study of Peptides from Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Male Silkmoth. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lao, F.; Pan, X.; Wu, J. Food Protein-Derived Antioxidant Peptides: Molecular Mechanism, Stability and Bioavailability. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udenigwe, C.C.; Fogliano, V. Food Matrix Interaction and Bioavailability of Bioactive Peptides: Two Faces of the Same Coin? J. Funct. Foods 2017, 35, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Mirdamadi, S.; Safavi, M.; Soleymanzadeh, N. The Stability of Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Peptides as Influenced by Peptide Sequences. LWT 2020, 130, 109710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lin, S.; Ye, H. Water Distribution and Moisture-Absorption in Egg-White Derived Peptides: Effects on Their Physicochemical, Conformational, Thermostable, and Self-Assembled Properties. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqui, N.; Williams, D.S.; Briones, A.; Kepiro, I.E.; Ravi, J.; Kwan, T.O.C.; Mearns-Spragg, A.; Ryadnov, M.G. Extracellular Matrix Type 0: From Ancient Collagen Lineage to a Versatile Product Pipeline – JellaGelTM. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 22, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.J.; Ekbom, D.C.; Hunter, D.; Voss, S.; Bartemes, K.; Mearns-Spragg, A.; Oldenburg, M.S.; San-Marina, S. Larynx Proteomics after Jellyfish Collagen IL: Increased ECM/Collagen and Suppressed Inflammation. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, T.-B.; He, T.-P.; Li, H.-B.; Tang, H.-W.; Xia, E.-Q. The Structure-Activity Relationship of the Antioxidant Peptides from Natural Proteins. Molecules 2016, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Ortíz, F.A.; Morón-Fuenmayor, O.E.; González-Méndez, N.F. Hydroxyproline Measurement by HPLC: Improved Method of Total Collagen Determination in Meat Samples. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2004, 27, 2771–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzideh, Z.; Latiff, A.A.; Gan, C.; Benjakul, S.; Karim, A.A. Isolation and Characterisation of Collagen from the Ribbon Jellyfish ( C Hrysaora Sp.). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P. m.; Petersen, D.; Dambmann, C. Improved Method for Determining Food Protein Degree of Hydrolysis. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Ortiz, F.A.; Caire, G.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Hernández, G. High Performance Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Free Amino Acids in Shrimp. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 1995, 18, 2059–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. [2] Ferric Reducing/Antioxidant Power Assay: Direct Measure of Total Antioxidant Activity of Biological Fluids and Modified Version for Simultaneous Measurement of Total Antioxidant Power and Ascorbic Acid Concentration. In Methods in Enzymology; Oxidants and Antioxidants Part A; Academic Press, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, R.L.; Hoang, H.; Gu, L.; Wu, X.; Bacchiocca, M.; Howard, L.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Jacob, R. Assays for Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Antioxidant Capacity (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORACFL)) of Plasma and Other Biological and Food Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3273–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, D.M.; Ames, B.N. Revised Methods for the Salmonella Mutagenicity Test. Mutat. Res. Mutagen. Relat. Subj. 1983, 113, 173–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).