Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

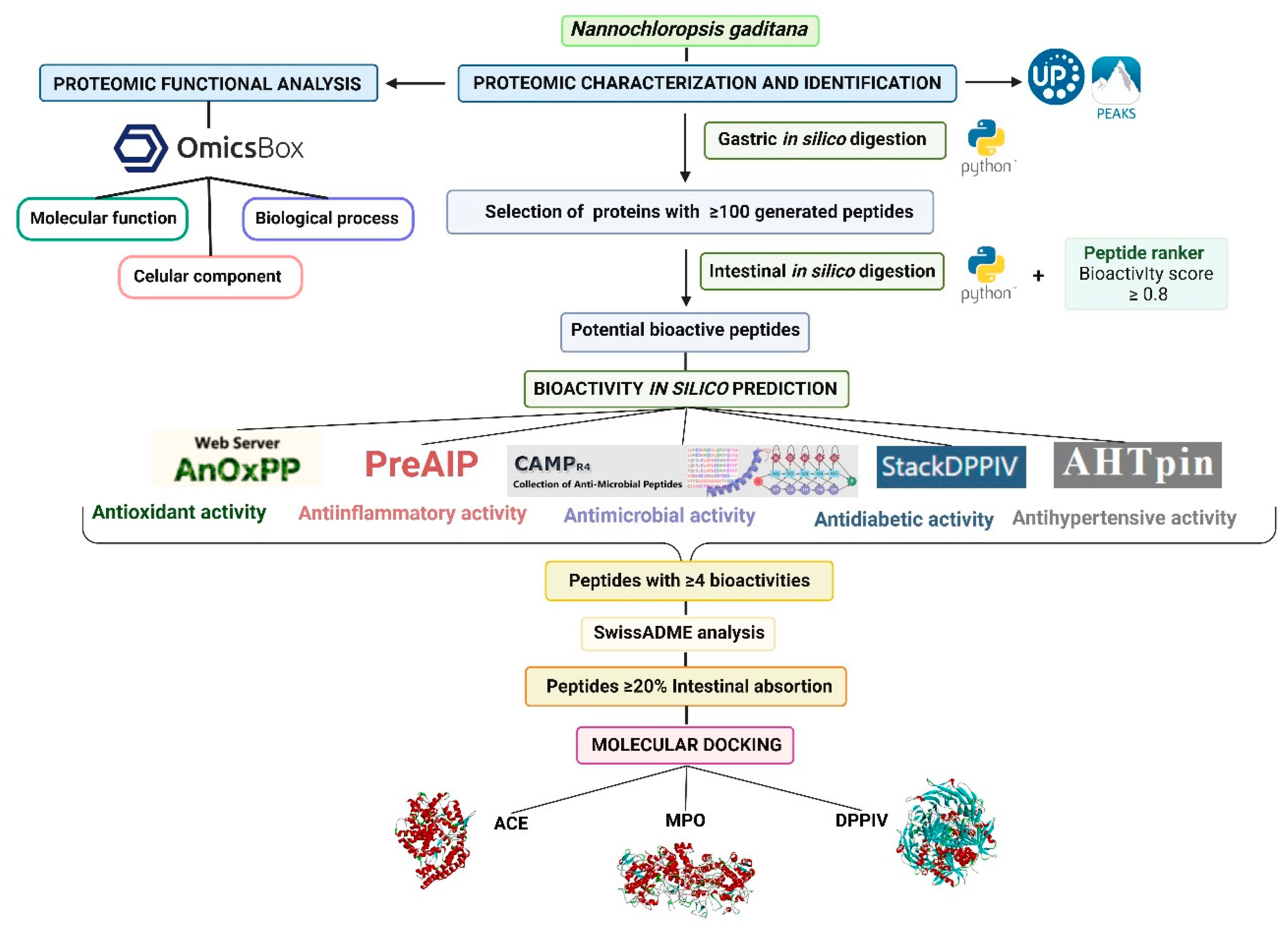

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Reagents

2.2. Proteomic Identification and Characterization

2.2.1. Protein Content and AA Profile

2.2.2. In-Gel Digestion (Stacking Gel)

2.2.3. Reverse Phase-Liquid Chromatography RP-LC-MS/MS Analysis (Dynamic Exclusion Mode)

2.2.4. Data Processing

2.3. Proteomic Functional Analysis

2.4. In silico Gastrointestinal Digestion

2.5. Bioactivity Prediction by In Silico Analysis

2.6. Physicochemical and Pharmacokinetic Analysis

2.7. Peptide Molecular Docking

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proteome of the Microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana

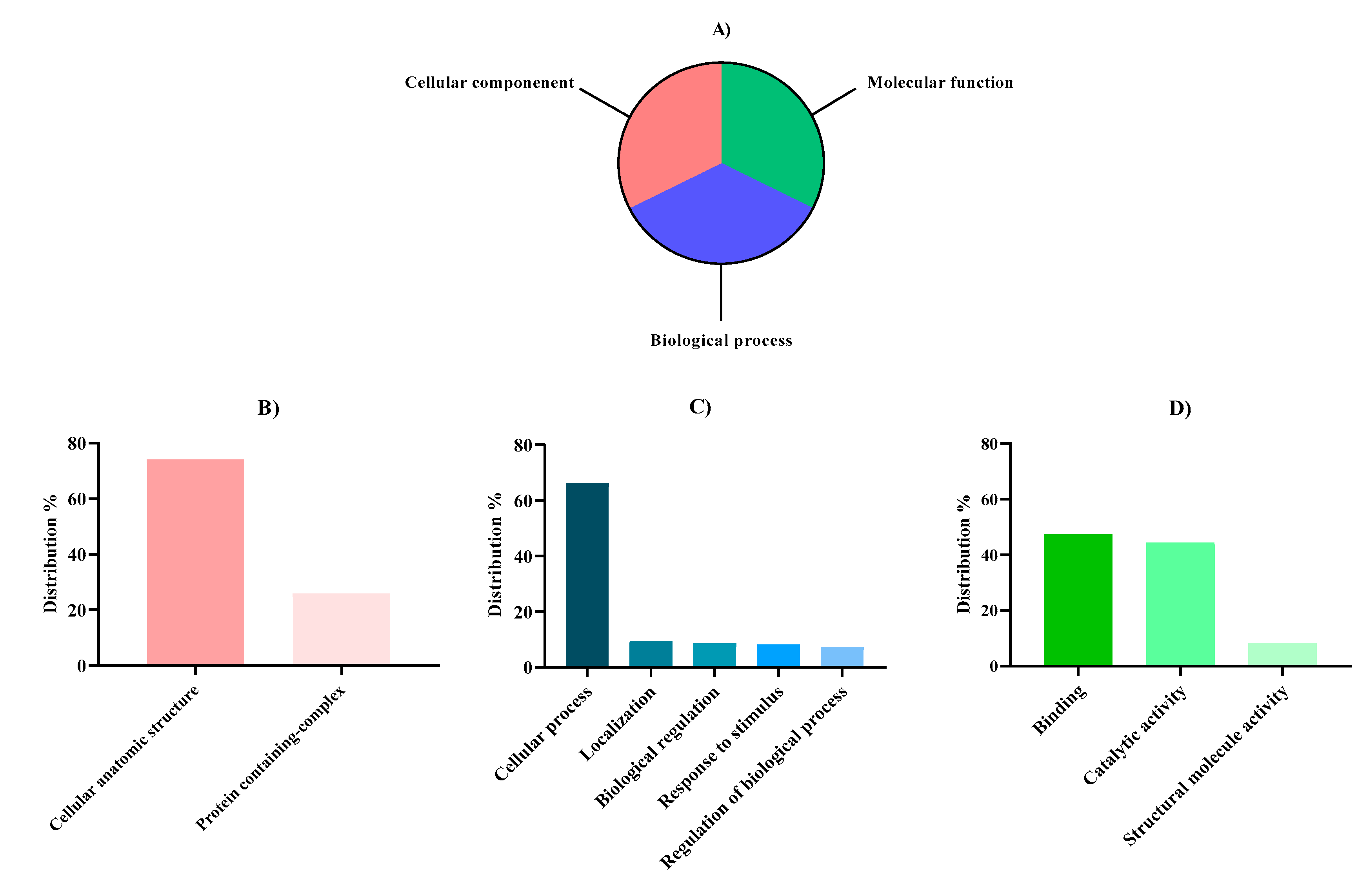

3.2. Functional Analysis of Nannochloropsis gaditana Proteome

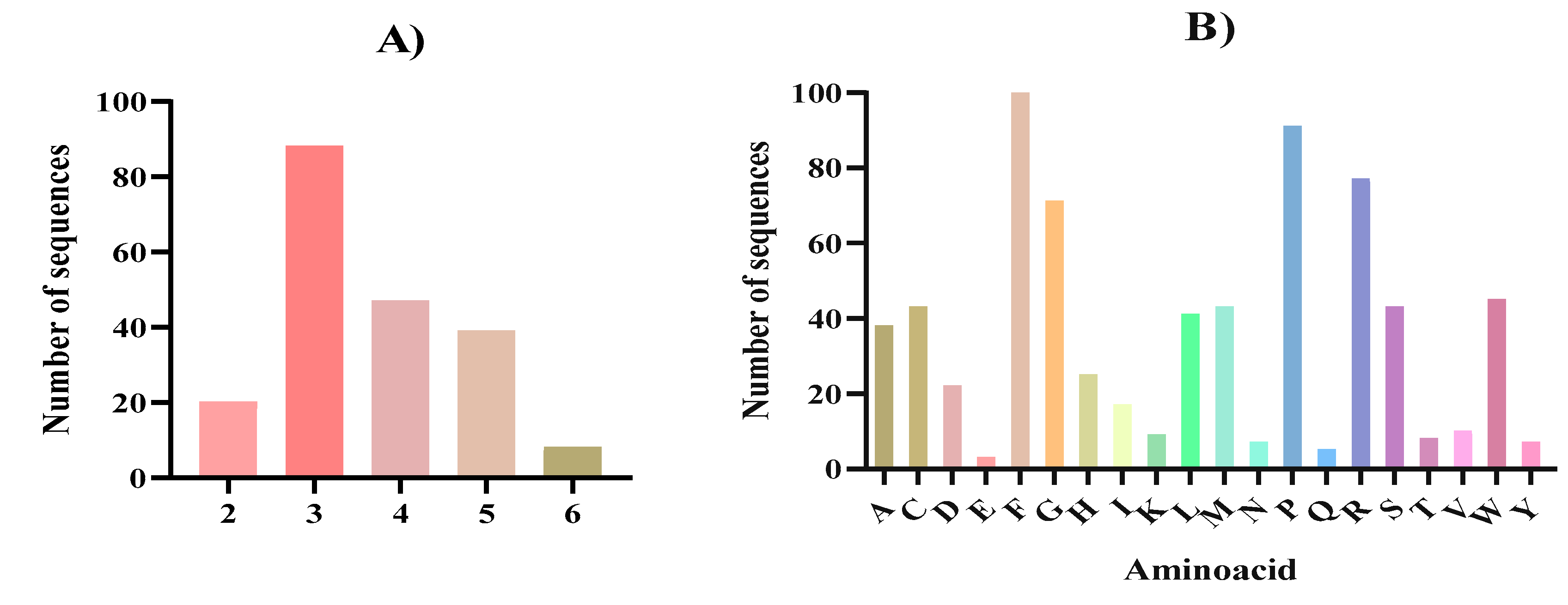

3.3. In Silico Gastrointestinal Digestion

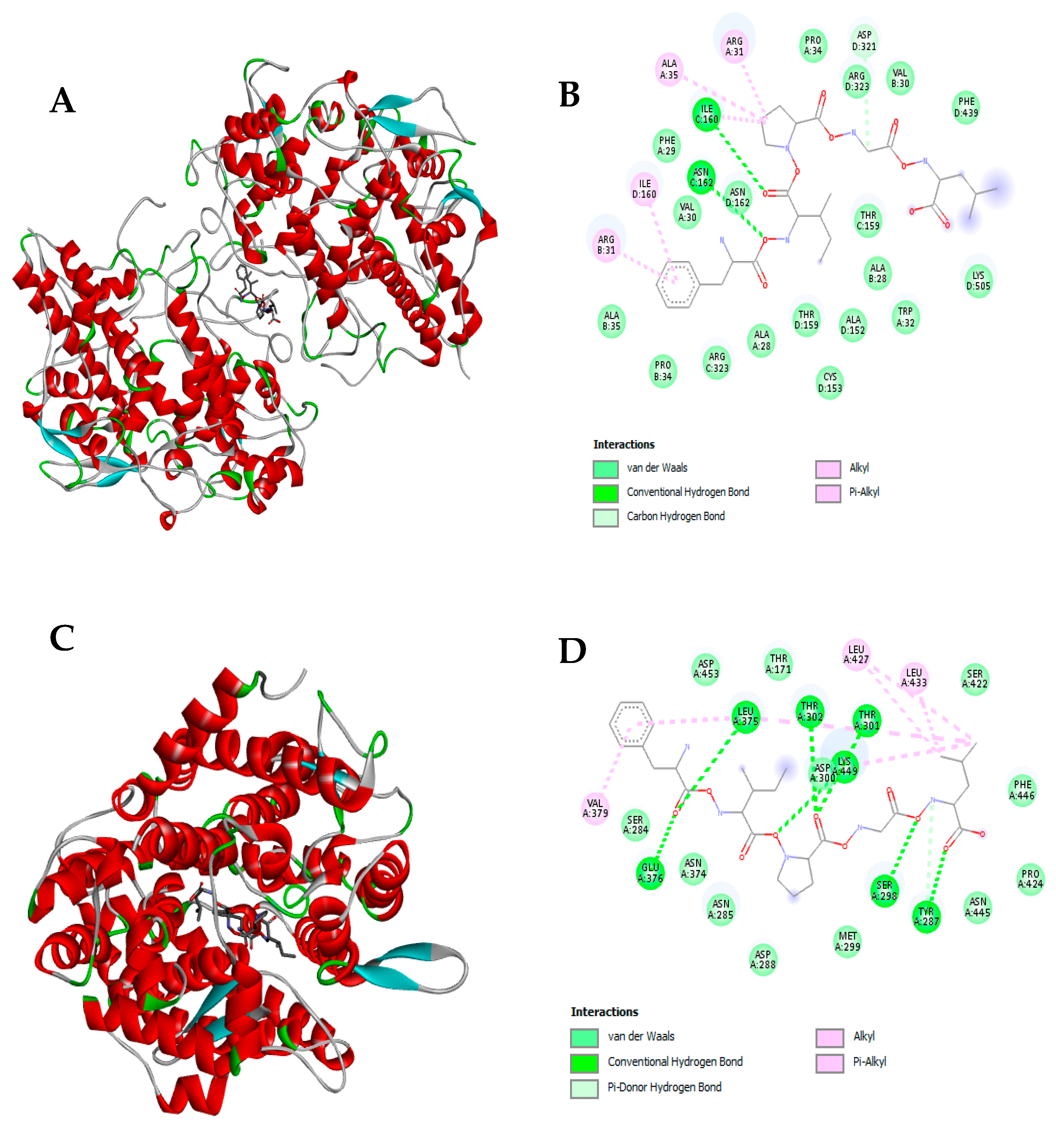

3.4. Peptide Molecular Docking

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennett, J.M.; Reeves, G.; Billman, G.E.; Sturmberg, J.P. Inflammation–Nature’s Way to Efficiently Respond to All Types of Challenges: Implications for Understanding and Managing “the Epidemic” of Chronic Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018, 5, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budreviciute, A.; Damiati, S.; Sabir, D.K.; Onder, K.; Schuller-Goetzburg, P.; Plakys, G.; Katileviciute, A.; Khoja, S.; Kodzius, R. Management and Prevention Strategies for Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) and Their Risk Factors. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 574111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floret, C.; Monnet, A.F.; Micard, V.; Walrand, S.; Michon, C. Replacement of Animal Proteins in Food: How to Take Advantage of Nutritional and Gelling Properties of Alternative Protein Sources. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 920–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvez, J.; Azzout-Marniche, D.; Tomé, D. Protein Quality, Nutrition and Health. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1406618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, D.; He, N.; Khoo, K.S.; Ng, E.P.; Chew, K.W.; Ling, T.C. Application Progress of Bioactive Compounds in Microalgae on Pharmaceutical and Cosmetics. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosibo, O.K.; Ferrentino, G.; Udenigwe, C.C. Microalgae Proteins as Sustainable Ingredients in Novel Foods: Recent Developments and Challenges. Foods 2024, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronakis, I.S.; Madsen, M. Algal Proteins. Handbook of Food Proteins 2011, 353–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski, P.; Budzulak, J.; Niedzielski, P.; Klimaszyk, P.; Proch, J.; Kozak, L.; Poniedziałek, B. Essential and Toxic Elements in Commercial Microalgal Food Supplements. J Appl Phycol 2019, 31, 3567–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolaore, P.; Joannis-Cassan, C.; Duran, E.; Isambert, A. Commercial Applications of Microalgae. J Biosci Bioeng 2006, 101, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Navarro-Juárez, R.; López-Martínez, J.C.; Campra-Madrid, P.; Rebolloso-Fuentes, M.M. Functional Properties of the Biomass of Three Microalgal Species. J Food Eng 2004, 65, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Rubilar, M.; Shene, C.; Torres, S.; Verdugo, M. Protein Fractions with Techno-Functional and Antioxidant Properties from Nannochloropsis Gaditana Microalgal Biomass. J Biobased Mater Bioenergy 2015, 9, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, A.A.; Paterson, S.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Bioactive Peptides Released from Microalgae during Gastrointestinal Digestion. Protein Digestion-Derived Peptides. [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Gong, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P. Recent Progress in the Preparation of Bioactive Peptides Using Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion Processes. Food Chem 2024, 453, 139587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheih, I.C.; Wu, T.K.; Fang, T.J. Antioxidant Properties of a New Antioxidative Peptide from Algae Protein Waste Hydrolysate in Different Oxidation Systems. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 3419–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Isolation and Identification of Anti-Proliferative Peptides from Spirulina Platensis Using Three-Step Hydrolysis. J Sci Food Agric 2017, 97, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Separation, Antitumor Activities, and Encapsulation of Polypeptide from Chlorella Pyrenoidosa. Biotechnol Prog 2013, 29, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.; Mora, L.; Lucakova, S. Identification of Bioactive Peptides from Nannochloropsis Oculata Using a Combination of Enzymatic Treatment, in Silico Analysis and Chemical Synthesis. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, T.S.; Ryu, B.M.; Kim, S.K. Purification of Novel Anti-Inflammatory Peptides from Enzymatic Hydrolysate of the Edible Microalgal Spirulina Maxima. J Funct Foods 2013, 5, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Saleh, N.I. Optimization of Enzymatic Hydrolysis for the Production of Antioxidative Peptide from Nannochloropsis Gaditana Using Response Surface Methodology. Pertanika J Sci & Technol 2019, 27, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Aiello, G.; Fassi, E.M.A.; Boschin, G.; Bartolomei, M.; Bollati, C.; Roda, G.; Arnoldi, A.; Grazioso, G.; Lammi, C. Investigation of Chlorella Pyrenoidosa Protein as a Source of Novel Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (Ace) and Dipeptidyl Peptidase-Iv (Dpp-Iv) Inhibitory Peptides. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; Cai, S.; Ryu, B.; Zhou, C.; Hong, P.; Qian, Z.J. An ACE Inhibitory Peptide from Isochrysis Zhanjiangensis Exhibits Antihypertensive Effect via Anti-Inflammation and Anti-Apoptosis in HUVEC and Hypertensive Rats. J Funct Foods 2022, 92, 105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavonius, L.R.; Albers, E.; Undeland, I. In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Proteins and Lipids of PH-Shift Processed Nannochloropsis Oculata Microalga. Food Funct 2016, 7, 2016–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peredo-Lovillo, A.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Romero-Luna, H.E. Conventional and in Silico Approaches to Select Promising Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: A Review. Food Chem X 2021, 13, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, S.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Galvez, A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Evaluation of the Multifunctionality of Soybean Proteins and Peptides in Immune Cell Models. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Methods of Analysis, 22nd Edition (2023) - AOAC INTERNATIONAL Available online:. Available online: https://www.aoac.org/official-methods-of-analysis/ (accessed on December 2024).

- Torres-Sánchez, E.; Morato, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Gutiérrez, L.F. Proteomic Analysis of the Major Alkali-Soluble Inca Peanut (Plukenetia Volubilis) Proteins. Foods 2024, 13, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchiz, Á.; Morato, E.; Rastrojo, A.; Camacho, E.; la Fuente, S.G. De; Marina, A.; Aguado, B.; Requena, J.M. The Experimental Proteome of Leishmania Infantum Promastigote and Its Usefulness for Improving Gene Annotations. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Wilm, M.; Vorm, O.; Mann, M. Mass Spectrometric Sequencing of Proteins Silver-Stained Polyacrylamide Gels. Anal Chem 1996, 68, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Pisa, D.; Marina, A.I.; Morato, E.; Rábano, A.; Rodal, I.; Carrasco, L. Evidence for Fungal Infection in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Brain Tissue from Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int J Biol Sci 2015, 11, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Qiao, R.; Xin, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Shan, B.; Ghodsi, A.; Li, M. Deep Learning Enables de Novo Peptide Sequencing from Data-Independent-Acquisition Mass Spectrometry. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.H.; Zhang, X.; Xin, L.; Shan, B.; Li, M. De Novo Peptide Sequencing by Deep Learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 8247–8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Rahman, M.Z.; He, L.; Xin, L.; Shan, B.; Li, M. Complete De Novo Assembly of Monoclonal Antibody Sequences. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 31730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillet, N. Rapid Peptides Generator: Fast and Efficient in Silico Protein Digestion. NAR Genom Bioinform 2020, 2, lqz004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, C.; Haslam, N.J.; Pollastri, G.; Shields, D.C. Towards the Improved Discovery and Design of Functional Peptides: Common Features of Diverse Classes Permit Generalized Prediction of Bioactivity. PLoS One 2012, 7, e45012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, D.; Jiao, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Liang, G. Prediction of Antioxidant Peptides Using a Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Predictor (AnOxPP) Based on Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network and Interpretable Amino Acid Descriptors. Comput Biol Med 2023, 154, 106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Kurata, H. PreAIP: Computational Prediction of Anti-Inflammatory Peptides by Integrating Multiple Complementary Features. Front Genet 2019, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawde, U.; Chakraborty, S.; Waghu, F.H.; Barai, R.S.; Khanderkar, A.; Indraguru, R.; Shirsat, T.; Idicula-Thomas, S. CAMPR4: A Database of Natural and Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D377–D383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chaudhary, K.; Singh Chauhan, J.; Nagpal, G.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, M.; Raghava, G.P.S. An in Silico Platform for Predicting, Screening and Designing of Antihypertensive Peptides. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoenkwan, P.; Nantasenamat, C.; Hasan, M.M.; Moni, M.A.; Lio’, P.; Manavalan, B.; Shoombuatong, W. StackDPPIV: A Novel Computational Approach for Accurate Prediction of Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV (DPP-IV) Inhibitory Peptides. Methods 2022, 204, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, D.E.; Taranu, I. Using In Silico Approach for Metabolomic and Toxicity Prediction of Alternariol. Toxins (Basel) 2023, 15, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Battistuz, T.; Bhat, T.N.; Bluhm, W.F.; Bourne, P.E.; Burkhardt, K.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.L.; Iype, L.; Jain, S.; et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 58, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Vital, D.; Weiss, M.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Anthocyanins from Purple Corn Ameliorated Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes via Activation of Insulin Signaling and Enhanced GLUT4 Translocation. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017, 61, 1700362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, V.M.; Navat Enriquez-Vara, J.; Urías-Silva, J.E.; del Carmen Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; Mojica, L. Mexican Grasshopper (Sphenarium Purpurascens) as Source of High Protein Flour: Techno-Functional Characterization, and in Silico and in Vitro Biological Potential. Food Research International 2022, 162, 112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavonius, L.R.; Albers, E.; Undeland, I. In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Proteins and Lipids of PH-Shift Processed Nannochloropsis Oculata Microalga. Food Funct 2016, 7, 2016–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaíno, A.J.; Sáez, M.I.; Martínez, T.F.; Acién, F.G.; Alarcón, F.J. Differential Hydrolysis of Proteins of Four Microalgae by the Digestive Enzymes of Gilthead Sea Bream and Senegalese Sole. Algal Res 2019, 37, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, W.; Perré, P.; Pozzobon, V. A Review of High Value-Added Molecules Production by Microalgae in Light of the Classification. Biotechnol Adv 2020, 41, 107545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Bioactivity and Digestibility of Microalgae Tetraselmis Sp. and Nannochloropsis Sp. as Basis of Their Potential as Novel Functional Foods. Nutrients 2023, 15, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, H.; Silva, J.; Santos, T.; Gangadhar, K.N.; Raposo, A.; Nunes, C.; Coimbra, M.A.; Gouveia, L.; Barreira, L.; Varela, J. Nutritional Potential and Toxicological Evaluation of Tetraselmis Sp. CtP4 Microalgal Biomass Produced in Industrial Photobioreactors. Molecules 2019, 24, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millward, D.J.; Layman, D.K.; Tomé, D.; Schaafsma, G. Protein Quality Assessment: Impact of Expanding Understanding of Protein and Amino Acid Needs for Optimal Health. Am J Clin Nutr 2008, 87, 1576S–1581S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Ma, B.; Zhang, K. Spider: software for protein identification from sequence tags with de novo sequencing error. J Bioinform Comput Biol 2011, 3, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.H.U.; Yi, E.K.J.; Amin, N.D.M.; Ismail, M.N. An Empirical Analysis of Sacha Inchi (Plantae: Plukenetia Volubilis L.) Seed Proteins and Their Applications in the Food and Biopharmaceutical Industries. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2024, 196, 4823–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, E.; Morato, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Gutiérrez, L.F. Proteomic Analysis of the Major Alkali-Soluble Inca Peanut (Plukenetia Volubilis) Proteins. Foods 2024, 13, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Acero, F.J.; Amil-Ruiz, F.; Durán-Peña, M.J.; Carrasco, R.; Fajardo, C.; Guarnizo, P.; Fuentes-Almagro, C.; Vallejo, R.A. Valorisation of the Microalgae Nannochloropsis Gaditana Biomass by Proteomic Approach in the Context of Circular Economy. J Proteomics 2019, 193, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Teixeira, C.; Abreu, H.; Silva, J.; Costas, B.; Kiron, V.; Valente, L.M.P. Nutritional Value, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Micro- and Macroalgae, Single or Blended, Unravel Their Potential Use for Aquafeeds. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33, 3507–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulatt, C.J.; Smolina, I.; Dowle, A.; Kopp, M.; Vasanth, G.K.; Hoarau, G.G.; Wijffels, R.H.; Kiron, V. Proteomic and Transcriptomic Patterns during Lipid Remodeling in Nannochloropsis Gaditana. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Wu, S.; Li, X.; Ge, B.; Zhou, C.; Yan, X.; Ruan, R.; Cheng, P. The Structure, Functions and Potential Medicinal Effects of Chlorophylls Derived from Microalgae. Marine Drugs 2024, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.G. In Silico Proteome Cleavage Reveals Iterative Digestion Strategy for High Sequence Coverage. Int Sch Res Notices 2014, 2014, 960902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchinin, A.G.; Bolshakova, E.I.; Barkovskaya, I.A. Bioinformatic Modeling (In Silico) of Obtaining Bioactive Peptides from the Protein Matrix of Various Types of Milk Whey. Fermentation 2023, 9, 380–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z. Zinc Finger Protein LipR Represses Docosahexaenoic Acid and Lipid Biosynthesis in Schizochytrium Sp. Appl Environ Microbiol 2022, 88, e0206321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Miao, X. Non-Tandem CCCH-Type Zinc-Finger Protein CpZF_CCCH1 Improves Fatty Acid Desaturation and Stress Tolerance in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 17188–17201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtiani, F.R.; Jalili, H.; Rahaie, M.; Sedighi, M.; Amrane, A. Effect of Mixed Culture of Yeast and Microalgae on Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase and Glycerol-3-Phosphate Acyltransferase Expression. J Biosci Bioeng 2021, 131, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardani, E.; Kallemi, P.; Tselika, M.; Katsarou, K.; Kalantidis, K. Spotlight on Plant Bromodomain Proteins. Biology 2023, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H. NgAP2a Targets KCS Gene to Promote Lipid Accumulation in Nannochloropsis Gaditana. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heda, R.; Toro, F.; Tombazzi, C.R.; Physiology, Pepsin. StatPearls 2023. Available online: https://www.statpearls.com (accessed on December 2024).

- Salelles, L.; Floury, J.; Le Feunteun, S. Pepsin Activity as a Function of PH and Digestion Time on Caseins and Egg White Proteins under Static in Vitro Conditions. Food Funct 2021, 12, 12468–12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, K.; Reddy, N.; Sunna, A. Exploring the Potential of Bioactive Peptides: From Natural Sources to Therapeutics. Int J of Mol Sci 2024, 25, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Agyei, D.; Udenigwe, C.C. Structural Basis of Bioactivity of Food Peptides in Promoting Metabolic Health. Adv Food Nutr Res 2018, 84, 145–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.J.; Mugesh, G. Antioxidant Activity of Peptide-Based Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Org Biomol Chem 2012, 10, 2237–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.W.; Li, B.; He, J.; Qian, P. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Study of Antioxidative Peptide by Using Different Sets of Amino Acids Descriptors. J Mol Struct 2011, 998, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, R.; Sun, X.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Production of Bioactive Peptides from Microalgae and Their Biological Properties Related to Cardiovascular Disease. Macromol 2024, 4, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, L.; Perugino, F.; Galaverna, G.; Dall’Asta, C.; Dellafiora, L. An In Silico Framework to Mine Bioactive Peptides from Annotated Proteomes: A Case Study on Pancreatic Alpha Amylase Inhibitory Peptides from Algae and Cyanobacteria. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1997, 23, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, I.; Hirano, H.; Nakagome, I. Comparison of Reliability of Log P Values for Drugs Calculated by Several Methods. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1994, 42, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, I.; Hirono, S.; Liu, Q.; Nakagome, Izum. ; Matsushita, Y. Simple Method of Calculating Octanol/Water Partition Coefficient. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1992, 40, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Y.C. A Bioavailability Score. J Med Chem 2005, 48, 3164–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Xu, M.; Udenigwe, C.C.; Agyei, D. Physicochemical Characterisation, Molecular Docking, and Drug-Likeness Evaluation of Hypotensive Peptides Encrypted in Flaxseed Proteome. Curr Res Food Sci 2020, 3, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkiewicz, P.; Iwaniak, A.; Darewicz, M. BIOPEP-UWM Database of Bioactive Peptides: Current Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Su, G.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y. In Vivo Anti-Hyperuricemic and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Properties of Tuna Protein Hydrolysates and Its Isolated Fractions. Food Chem 2019, 272, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.-W.; Lin, B.-F.; Juan, H.-F.; Huang, S.-C.; Tsai, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-C. Sweet Potato Storage Root Defensin and Its Tryptic Hydrolysates Exhibited Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity in Vitro. Bot Stu 2012, 53, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Carretero, O.A.; Vuljaj, N.; Liao, T.D.; Motivala, A.; Peterson, E.L.; Rhaleb, N.E. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: A New Mechanism of Action. Circulation 2005, 112, 2436–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, V.T.T.; Ito, K.; Ohno, M.; Motoyama, T.; Ito, S.; Kawarasaki, Y. Analyzing a Dipeptide Library to Identify Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Inhibitor. Food Chem 2015, 175, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, H.S.; Wang, F.L.; Ondetti, M.A.; Sabo, E.F.; Cushman, D.W. Binding of Peptide Substrates and Inhibitors of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme. Importance of the COOH-Terminal Dipeptide Sequence. J Bio Chem 1980, 255, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, S.; Singh, J.; Singh, H. Hydrolysis of Various Bioactive Peptides by Goat Brain Dipeptidylpeptidase-III Homologue. Cell Biochem Funct 2008, 26, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y, S.; K, W.; A, K.; S, I. Structure and Activity of Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides from Sake and Sake Lees. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1994, 58, 1767–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, H.; Bao, X.; Wu, J. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Activation Is Not a Common Feature of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 8867–8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senadheera, T.R.L.; Hossain, A.; Dave, D.; Shahidi, F. In Silico Analysis of Bioactive Peptides Produced from Underutilized Sea Cucumber By-Products—A Bioinformatics Approach. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, N.T.P.; Hsu, J.L. Bioactive Peptides: An Understanding from Current Screening Methodology. Processes 2022, 10, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.G.; Dos Santos, R.N.; Oliva, G.; Andricopulo, A.D. Molecular Docking and Structure-Based Drug Design Strategies. Molecules 2015, 20, 13384–13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Cosmes, P.; Raftopoulou, S.; Mihalic, Z.N.; Marsche, G.; Kargl, J. Myeloperoxidase: Growing Importance in Cancer Pathogenesis and Potential Drug Target. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 236, 108052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakhrusheva, T. V.; Sokolov, A. V.; Moroz, G.D.; Kostevich, V.A.; Gorbunov, N.P.; Smirnov, I.P.; Grafskaia, E.N.; Latsis, I.A.; Panasenko, O.M.; Lazarev, V.N. Effects of Synthetic Short Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides on the Catalytic Activity of Myeloperoxidase, Reducing Its Oxidative Capacity. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2419–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Morton, J.S.; Panahi, S.; Kaufman, S.; Davidge, S.T.; Wu, J. Egg-Derived ACE-Inhibitory Peptides IQW and LKP Reduce Blood Pressure in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J Funct Foods 2015, 13, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Aluko, R.E.; Nakai, S. Structural Requirements of Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Modeling of Peptides Containing 4-10 Amino Acid Residues. QSAR Comb Sci 2006, 25, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natesh, R.; Schwager, S.L.U.; Sturrock, E.D.; Acharya, K.R. Crystal Structure of the Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme-Lisinopril Complex. Nature 2003, 421, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vaquero, M.; Mora, L.; Hayes, M. In Vitro and in Silico Approaches to Generating and Identifying Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme I Inhibitory Peptides from Green Macroalga Ulva Lactuca. Mar Drugs 2019, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aminoacid | Content | FAO recommendation (g/100 g protein) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| g/100 g protein | g/100 g biomass | ||

| Essential | |||

| Lysine (K) | 4.53 ± 0.09 | 2.01 ± 0.04 | 5.20 |

| Tryptophan (W) | n.d. | n.d. | 0.70 |

| Phenylalanine (F) | 3.62 ± 0.17 | 1.61 ± 0.08 | 4.60a |

| Tyrosine (Y) | 2.42 ± 0.07 | 1.07 ± 0.03 | |

| Methionine (M) | 1.57 ± 0.01 | 0.70 ± 0.01 | 2.60b |

| Cysteine (C) | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | |

| Threonine (T) | 3.40± 0.15 | 1.51 ± 0.06 | 2.70 |

| Leucine (L) | 5.97 ± 0.01 | 2.65 ± 0.00 | 6.30 |

| Isoleucine (I) | 2.53 ± 0.03 | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 3.10 |

| Valine (V) | 3.40 ± 0.02 | 1.51 ± 001 | 4.20 |

| Non-essential | |||

| Aspartic acid + Asparragine (D + N) | 6.44 ± 0.00 | 2.85 ± 0.00 | |

| Glutamic acid + Glutamine (E + Q) | 8.81 ± 0.09 | 3.91 ± 0.04 | |

| Serine (S) | 3.29 ± 0.15 | 1.46 ± 0.07 | |

| Histidine (H) | 1.38 ± 0.01 | 0.61 ± 0.00 | |

| Arginine (R) | 4.17 ± 0.00 | 1.85 ± 0.00 | |

| Alanine (A) | 5.02 ± 0,01 | 2.22 ± 0.01 | |

| Proline (P) | 6.44 ± 0,01 | 2.85 ± 0.00 | |

| Glycine (G) | 3.55 ± 0.02 | 1.57 ± 0.01 | |

| EAA | 28.31 | 14.13 | |

| NEAA | 39.01 | 17.28 | |

| TAA | 67.41 | 31.41 | |

| EAA*100/TAA (%) | 42.00 | ||

| EAA*100/NEAA (%) | 72.57 | ||

| HAA*100/TAA (%) | 47.23 | ||

| AAA*100/TAA (%) | 8.96 | ||

| Accession a | -10logP b | Description c | Average mass (KDa) |

Peptides generated after in silico gastric digestion |

| I2CQP5 | 426.87 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | 235,196 | 207 |

| W7U8G3 | 380.26 | ATP-citrate synthase | 120,317 | 102 |

| W7TN63 | 348.14 | Choline dehydrogenase | 138,839 | 113 |

| K8YSL1 | 287.43 | Aminopeptidase N | 137,581 | 102 |

| W7TQD1 | 264.44 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit alpha | 120,314 | 103 |

| W7TTR4 | 192.91 | P-type atpase | 129,122 | 103 |

| W7UC18 | 192.19 | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase | 145,158 | 113 |

| W7TNH0 | 182.55 | Pyruvate carboxilase | 134,055 | 102 |

| K8Z9A0 | 174.11 | Uncharacterized protein | 123,187 | 107 |

| W7TRK7 | 118.17 | Coatomer subunit alpha | 141,192 | 119 |

| W7UBG5 | 106.82 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme e1 | 136,993 | 111 |

| W7U8K2 | 105.69 | Clathrin heavy chain | 196,113 | 163 |

| W7TM9 | 93.66 | Pentatricopeptide repeat containing protein | 171,849 | 132 |

| W7UBN0 | 87.72 | WD40-repeat-containing protein | 138,346 | 110 |

| W7U2D5 | 80.11 | Peptidase M16 | 143,228 | 109 |

| W7U0Z1 | 79.24 | Hydantoin utilization protein | 146,652 | 128 |

| W7U5E4 | 65.46 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase | 168,186 | 140 |

| W7U2B9 | 62.39 | Zinc finger. ZZ-type | 552,820 | 376 |

| K8YRI3 | 61.47 | DUF2428 domain-containing protein (Fragment) | 124,306 | 102 |

| W7TVB1 | 56.86 | Bromodomain containing 1 | 243,436 | 169 |

| W7TYI7 | 46.56 | Cytochrome p450 | 118,277 | 117 |

| W7U1T9 | 46.41 | Nuclear receptor corepressor 1-like protein | 164,110 | 122 |

| W7U7L8 | 45.19 | Protease-associated domain PA | 142,381 | 101 |

| W7TPR4 | 44.49 | Tubulin-specific chaperone d | 147,094 | 109 |

| TOTAL | 3160 |

| Peptide | Molecular weight (Da) | Lipophilicity (MLogP)a | Bioavailability scoreb | Water solubility (log mol/L)c |

% Intestinal absorptiond | AMES toxicitye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FK FR GF RF ARF1 DPMP FHPR FSPR HPKF MPPR VPGF APMRP FIPGL1, 2 GPGCG KAPPF KSPGW1 PCMIR PFGNR PRPMR RRCLF1 WWGGV YLPPR2 AVMPIF EFPMIR FARPGL1 FGPQGG1 FLPPAL1 |

293.36 | 0.6 | 0.55 | -2.818 | 35.3 | No |

| 321.37 | 0.15 | 0.55 | -2.643 | 21.61 | No | |

| 222.24 | 0.34 | 0.55 | -1.85 | 41.89 | No | |

| 321.37 | 0.14 | 0.55 | -2.617 | 21.43 | No | |

| 60.06 | -1.6 | 0.55 | 0.824 | 71.496 | No | |

| 458.53 | -1.11 | 0.11 | -2.27 | 0 | No | |

| 555.63 | -1.46 | 0.17 | -2.875 | 6.011 | No | |

| 505.57 | -1.56 | 0.17 | -2.835 | 0 | No | |

| 527.62 | -1.11 | 0.17 | -2.815 | 17.04 | No | |

| 499.63 | -1.01 | 0.17 | -2784 | 6.78 | No | |

| 418.49 | -0.1 | 0.55 | -2.524 | 28.49 | No | |

| 570.71 | -1.53 | 0.17 | -2.922 | 0 | No | |

| 545.67 | 0.15 | 0.17 | -3.174 | 21.02 | No | |

| 389.43 | -2.73 | 0.55 | -2.516 | 2.96 | No | |

| 558.67 | -0.6 | 0.17 | -2.833 | 16.56 | No | |

| 573.64 | -2.17 | 0.17 | -2.862 | 0.134 | No | |

| 618.81 | -1.32 | 0.17 | -2.889 | 0 | No | |

| 589.64 | -2.49 | 0.17 | -2.889 | 0 | No | |

| 655.81 | -1.98 | 0.17 | -2.889 | 0 | No | |

| 693.86 | -1.22 | 0.17 | -2.894 | 0 | No | |

| 603.67 | -0.74 | 0.17 | -3.015 | 19.76 | No | |

| 644.76 | -0.84 | 0.17 | -2.904 | 19.333 | No | |

| 676.87 | -0.07 | 0.17 | -3.012 | 11.265 | No | |

| 791.96 | -1.31 | 0.17 | -2.894 | 0 | No | |

| 659.78 | -1.51 | 0.17 | -2.922 | 0 | No | |

| 561.59 | -2.77 | 0.17 | -2.977 | 0.112 | No | |

| 656.81 | 0.12 | 0.17 | -3.29 | 17.79 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).