1. Introduction

In the body tissues, aerobic metabolism comprises a series of biochemical reactions aimed at converting raw materials into energy, and synthesizing macromolecules, releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) through metabolic pathways. ROS constitute highly reactive and unstable molecules due to unpaired electrons, such as hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), hydroxyl radicals (HO

●), peroxynitrite (ONOO), superoxide anion (O2

●‾), and peroxyl radicals (ROO

●) [

1]. To counteract ROS production, cells have antioxidant defense mechanisms that convert free radicals into non-reactive species, and these, into harmless components. However, when ROS overload the body's defenses, oxidative stress occurs, leading to damage of vital cellular components such as proteins, lipids, and DNA [

2]. Oxidative stress in human body increase the risks of developing non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cancer, inflammation, and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases [

3].

Antioxidant peptides possess the capability to eradicate ROS and impede reactions mediated by free radicals. These peptides offer the additional benefits of being minimally toxic or non-toxic, are abundantly derived from food sources, and are preferred by individuals as an oral preventive strategy over intravenous administration [

4]. Food-derived peptides have been extensively researched over the past two decades for their capacity to mitigate oxidative stress-associated non-communicable diseases [

5,

6]. More than 1000 antioxidant peptides have been identified from milk, animal- and plant-derived foods through enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation, or autolysis techniques [

7].

Plant-derived peptides, especially from by-products like oilseed cakes, are gaining popularity due to increased awareness of sustainable food systems [

8,

9]. Sacha Inchi (SI) (

Plukenetia volubilis) is an oil-producing plant native to the Amazon region of South America that has significantly expanded into Africa and Asia due to its economic appeal [

10]. The main by-product generated by the industry is the SI Oil Press-Cake (SIPC), which represents up to 50% of the raw seeds. Due to the quality of its proteins, SIPC has recently being used as a source of protein isolates and hydrolysates with techno-functional and bioactive properties [

11,

12,

13]. However, the bioactive peptides responsible for the health benefits of SIPC may undergo digestion, absorption, and transport from the gastrointestinal tract to tissues through the bloodstream, which could potentially lead to structural changes and, as a result, alterations of their biological effects [

14]. Recently, protein hydrolysates have been obtained using digestive enzymes acting on SIPC, which exhibit antioxidant properties in

in vitro assays and

ex vivo studies [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the identification of these sequences has scarcely been conducted, and no study has yet explored the drug likeness of the derived bioactive peptides.

Traditional methods for discovering bioactive peptides, involving substrate fractionation, enzymatic hydrolysis followed by purification and bioactivity assays, are laborious, time-consuming, and costly, often yielding inconsistent results. Conversely, bioinformatics-driven

in silico approaches offer a promising, cost-effective alternative for peptide discovery. Recently, an integrated methodology that combines aspects of both approaches has emerged, using peptides identified from food hydrolysates as a starting point for targeted bioinformatics analysis [

17]. This study aims to advance research on antioxidant peptides derived from SIPC by identifying potential candidates and assessing their bioactivity and bioavailability through a combination of

in vitro,

ex vivo, and

in silico assays.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

SIPC was kindly donated by SumaSach’a (Mosquera, Cundinamarca, Colombia). All chemicals (reagents and solvents) were of analytical grade and provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA). For absorbance and fluorescence measures, Sarstedt AG & Co. (Nümbrecht, Germany) and Corning Costar Corporation (NY, USA) supplied the 96-well and 48-well plates, respectively. The electrophoresis analysis was conducted using the equipment and reagents provided by Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). Biowest (Kansas City, MO, USA) supplied reagents and culture media for RAW 264.7 macrophages assays.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Protein Concentrate Production

SIPC adequacy and Sacha Inchi Protein Concentrate (SPC) production were conducted using essentially the procedure reported [

18]. Briefly, defatted SIPC was mixed with deionized water (1:10 ratio, w/v) under alkaline conditions (pH 11.0) with continuous stirring (1 h, 800 rpm) at 60-70°C. Upon centrifugation, the supernatant was retrieved, neutralized, and diafiltrated. Subsequently, the soluble protein solution (SPC) was freeze-dried and stored at -18°C until assays.

2.2.2. Static Simulation of Gastro-Intestinal Digestion

The

in vitro INFOGEST 2.0 method [

19] was employed. Saliva gathered from twenty healthy volunteers was combined and preserved at -18°C. Simulated gastric and intestinal fluids were prepared according to the protocol. Briefly, 3 g of SPC (n=6) was dissolved in saliva at a ratio of 1:5 (w/v) and subjected to the oral phase for 5 min at 37°C. The mixture was then diluted (1:1, v/v) with simulated gastric fluid (pH 3.0) containing pepsin (EC 3.4.23.1) at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio (E:S) of 1:60 (w/w) and subjected to the gastric phase for 2 h. Samples (gastric digest, GD, n=3) were collected after pepsin inactivation (pH adjustment to 7.0, heating at 95°C for 15 min) and freezing at -40°C. After completing the gastric phase, samples were mixed with simulated intestinal fluid (1:1, v/v) containing pancreatin at an E:S ratio of 1:1.2 (w/w), and bile salts at a ratio 1:30 (w/w) and subjected to the intestinal phase for 2 h. Samples (intestinal digest, ID, n=3) were collected after pancreatin inactivation, following the same freezing protocol.

Subsequently, samples were processed using the Sartorius® ultrafiltration system (Vivaflow® TFF Cassette, Göttingen, Germany). Digests underwent ultrafiltration with a 3-kDa membrane. The resulting permeate (containing molecules <3 kDa) was collected as GD3 or ID3. The 3-kDa retentate was then filtered through a 10-kDa membrane, producing a permeate (>10 kDa) for GD1 or ID1, and a retentate (>3 kDa and <10 kDa) for GD2 or ID2. Blanks of digestion (labelled as B- plus the respective digest) without sample were also obtained and fractioned. All samples were freeze-dried and stored at -18°C until further analysis.

2.2.3. Electrophoretic Profile

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis was carried out to assess the protein profile of SPC, following the methodology reported [

20]. A Criterion

TM Cell system (Bio-Rad) was used. 75 µg of protein quantified by using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were loaded onto a 12% Bis-Tris Criterion™ XT Precast Gel polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoretic migration was performed initially at 100 V for 5 minutes, followed by 150 V for 1 hour. The gel image was acquired using the Molecular Imager® VersaDoc™ MP 4000 (Bio-Rad) and analyzed with Image Lab 6.1 software (Bio-Rad).

2.3. In Vitro Assays

Antioxidant activity was assessed using the ABTS and ORAC assays, following the methods described [

20]. For the ABTS assay, the absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a Biotek SynergyTM HT plate reader (Winooski, VT, USA). For the ORAC assay, fluorescence readings were taken every 2 min over 120 min at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 520 nm, respectively, using a FLUOstar Optima BMG Labtech plate reader controlled by FLUOstar Control ver. 1.32 R2 Software (Ortenberg, Germany). Results from both assays were expressed as µmol Trolox equivalent (TE) per g of sample.

2.4. Ex Vivo Assays

2.4.1. Macrophages Culture

RAW 264.7 mouse macrophages (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) were cultured routinely in T75 flasks with modified Dulbecco's Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air. The culture medium was refreshed every 2-3 days. Upon reaching 80-90% confluence, cells were harvested by gentle scraping, washed with PBS, and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min to obtain cell pellets. The pellets were then resuspended in DMEM to prepare a stock solution. Cell counting was performed using an EVE™ Plus cell counter (NanoEntek, Seoul, Korea) to adjust cell suspensions to the desired density for subsequent assays.

2.4.2. Cytotoxicity Assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay, which measures the activity of cellular dehydrogenases, was determined according to the literature [

21]. RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 1 × 10

5 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with 120 µL of sample (at various concentrations) in FBS-free DMEM, and cells were further incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Negative control received FBS-free DMEM. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS, treated with MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) for 2 h at 37°C, and formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Biotek Synergy

TM HT reader. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to controls, considered as 100%.

2.4.3. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production

The evaluation of the effect of samples on the intracellular ROS levels was determined according to the literature [

22]. Cells were seeded at 5 × 10

5 cells/well in 48-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Then, the medium was discarded, and cells were treated with 120 μL of sample (at two concentrations) dissolved in DMEM without FBS, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The negative control was DMEM without FBS, and the positive control was FBS-free DMEM supplemented with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 µg/mL). After removing the treatment, 100 μL/well of 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, 0.4 mg/mL), dissolved in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), was added, and the plate incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The fluorescence was measured at 485 and 520 nm wavelengths of excitation and emission, respectively, by using the FLUOstar Optima BMG Labtech plate reader. Results were expressed as % of control, which was 100%.

2.5. De Novo Peptides Sequencing

Analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was conducted by the Proteomics Facility at the Center of Molecular Biology Severo Ochoa (CBM, CSIC-UAM, Madrid, Spain). An ion trap LTQ-Orbitrap-Velos-Pro hybrid mass spectrometer equipped with a nano spray source and an Easy-nLC 1200 system (Thermo Scientific) was used, following essentially the protocol described [

23]. The peptidome was determined using mass spectrometric data, which was analyzed with the

de novo PEAKS Studio search engine (V11.5, Bioinformatics Solutions Inc., Waterloo, Ontario, Canada). Peptides with Average Local Confidence (ALC) ≥ 85%, calculated as the sum of residue local confidence scores in the peptide divided by the peptide length, were selected for further analysis, ensuring high confidence in peptide identifications.

2.6. In Silico Assays

2.6.1. Resistant Peptides to Gastrointestinal Digestion

The data analysis was performed at the Biocomputational Analysis Core Facility (SABio, CBM). A comparison of

de novo peptide sequences of the ID sample and those of SPC generated by PEAKS Studio was performed using the find-pep-seq

script [

24], transforming peptide sequences into vectors. Based on the results, the cosine similarity measure (threshold of 0.95) was calculated [

25]. This value ranged from 0 to 1, where 0 indicated that two vectors were orthogonal, and 1 indicated that they were identical in direction. Also, paired peptide sequences with a length difference of more than 8 amino acids were discarded. This ensured that the paired sequences were comparable in magnitude. Finally, the resulting ID sequences were deduplicated to ensure each entry was unique, and formatted into a FASTA file, which was used as input in subsequent bioinformatics tools. Through this data analysis, ID peptide sequences were considered as resistant peptides to

in vitro gastrointestinal digestion.

2.6.2. Antioxidant Properties and Bioavailability of Resistant Peptides

The resistant peptides were classified as antioxidants or non-antioxidants using the AnOxPP software [

7]. Subsequently, the AnOxPePred-1.0 software [

26], predicted the likelihood of the antioxidant peptides to scavenge free radicals, with the top 20 peptides selected for further

in silico analysis: a) PlifePred [

27] was employed to predict the half-life of peptides in blood and to estimate their hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity; b) PepCalc was employed to estimate the molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI), length and solubility of peptides [

28]; c) PASTA 2.0 was employed to estimate the secondary structure [

29]; d) ToxinPred [

30], and AllerCatPro 2.0 [

31] tools were employed to predict whether the selected resistant peptides were non-toxic or allergenic, respectively; e) SwissADME [

32] was used to assess the bioavailability of the selected peptides, evaluating the drug-likeness parameters such as Lipinski filter and bioavailability score, pharmacokinetics, some physicochemical properties, and lipophilicity; and f) the probability of cell-penetrating peptides (CPP) was predicted using the BChemRF-CPPred software [

33].

2.7. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

A The in vitro and ex vivo experiments were carried out under completely randomized designs, with each parameter evaluated independently and measurements performed in triplicate at minimum. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) and test of significance (least significant differences (LSD) tests) were performed using SAS® OnDemand Software (Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., accessed in April of 2024). The homogeneity of variances was tested using Levene tests. The normality of the residuals was tested using a Shapiro-Wilks test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

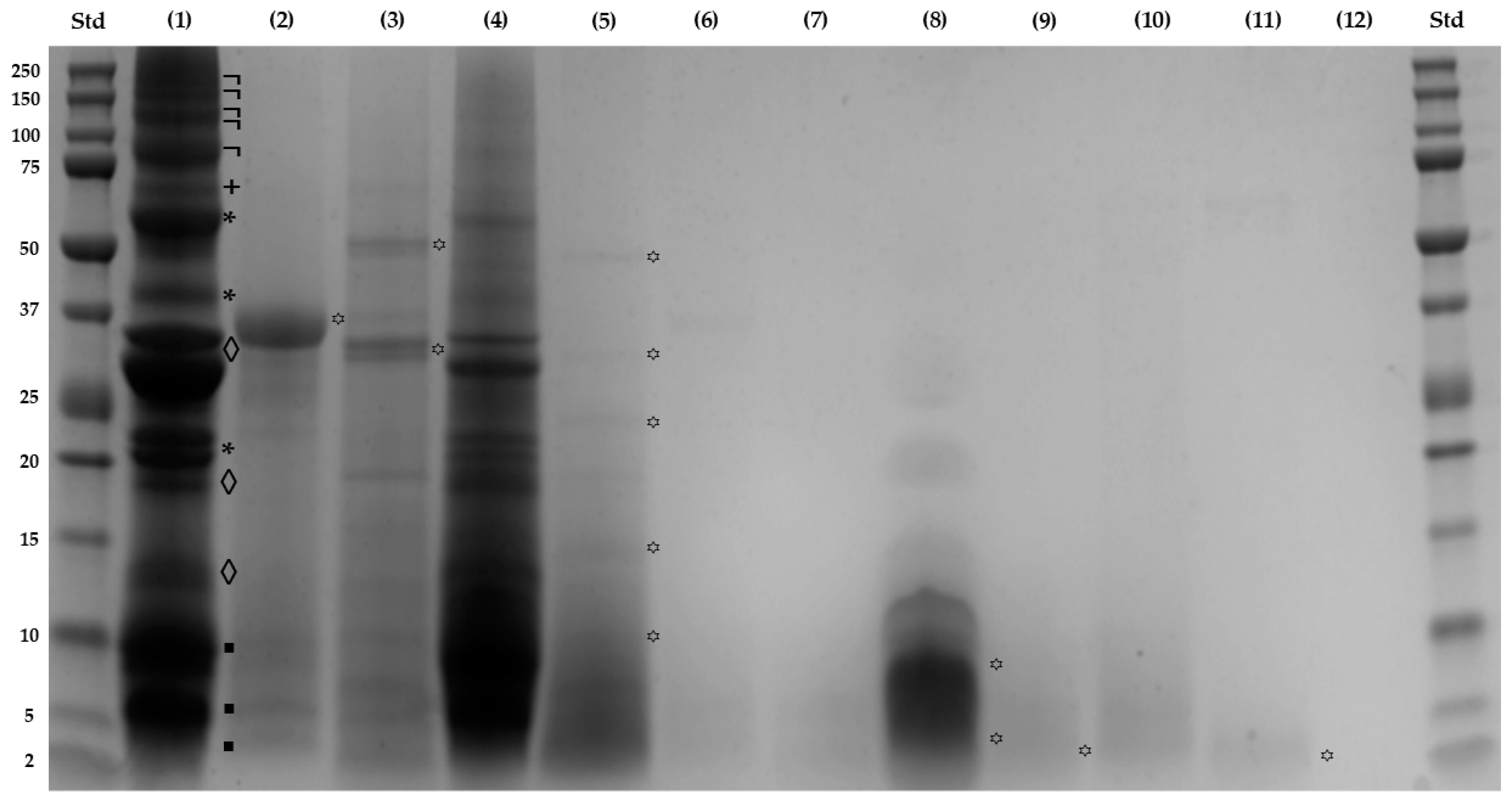

3.1. SDS-PAGE

T SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions was conducted to analyze the impact of simulated gastrointestinal digestion and ultrafiltration on the alkaline soluble protein profile of SPC, illustrated in

Figure 1. Lane (1), corresponding to SPC sample, revealed fifteen protein bands ranging from 4.2 to 186.9 kDa. The use of alkaline water and moderate temperature was highly effective in extracting major proteins: albumins (◊), including the 3S albumin (27.5 kDa); globulins (*) at 47.4, 37.7, and 21.0 kDa; prolamins (▪) at 10.0, 6.3, and 4.2 kDa; and glutelins (+) at 69.9 kDa, all them well-documented in literature [

34,

35,

36]. Additionally, novel high MW polypeptides (¬) ranging from 186.9 to 86.8 kDa were observed, potentially including glutelins with enzymatic functions like beta-galactosidase, as suggested by gene ontology analysis (data not shown), necessitating further investigation for validation.

In lines (2) and (3) (B-GD1 and B-ID1 fractions, respectively), the polypeptides (

꙳) of 37.8 kDa, 63.7 kDa and 35.6 kDa correspond to the enzymes utilized, as reported previously [

37]. The loss of these polypeptides was evident due to the ultrafiltration process, as shown in lines (6) (7), and (10), corresponding to B-GD2, B-ID2, and B-ID3 fractions, respectively. In line (4) for GD1 fraction, the degradation of higher MW polypeptides (

¬), glutelins (

+), and the globulin (

*) (37.7 kDa), and partial degradation of other proteins like albumins (◊), globulins (*) (47.4, and 21.0 kDa), and prolamins (▪), initially present in SPC (line (1)), became evident once gastric digestion was completed. Similarly, the line (5) for ID1 fraction revealed that intestinal digestion process was complete, yielding polypeptides (꙳) of 58.0, 33.0, 23.2, 16.6, and 11.3 kDa. Meanwhile, the fractionation process efficiently concentrated peptides (꙳) based on their molecular size: between 8.0 and 3.8 kDa for GD2 fraction (line (8)); 3.1 kDa for ID2 fraction (line (9)); and 3.7 kDa for GD3 fraction (line (11)). Peptides were not detectable in the ID3 fraction (line (12)) due to the resolving gel pore size used.

These results were consistent with recent findings where hydrolysis of glutelin from SI using pepsin and trypsin yielded peptides with MW < 3 kDa at 74% and 78%, respectively. Complete hydrolysis of all fractions (albumin, globulin, and especially glutelin) was accomplished sequentially, with trypsin being more effective due to its higher number of cleavage sites. Authors have suggested that glutelins extracted via alkaline solution, may be more readily absorbed due to their rough surface with small pores, facilitating enzyme access to recognition sites. Additionally, the limited presence of antiparallel β-sheet structures in glutelins aids their hydrolysis [

15]. These findings aligned closely with our previous results demonstrating the absence of intermolecular β-sheets in alkali-soluble proteins from SPC [

38].

3.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Performance

T To evaluate the effect of simulated digestion on the antioxidant activity of SPC, ABTS and ORAC assays were performed, as shown in

Table 1. These assays utilize distinct mechanisms to mitigate the action of free radicals. Thus, ABTS radical scavenging assay is founded upon the capacity of antioxidants to neutralize free radicals by donating an electron [

15]. On the other hand, ORAC assay measures the antioxidant capacity to inhibit the consumption of a target molecule mediated by peroxyl radicals, physiologically relevant radicals, and assesses a singular mechanism of action based on hydrogen atom transfer [

39]. SPC exhibited significantly lower (

P < 0.05) TEAC (30.85 µmol TE/g of sample) and ORAC (120.79 µmol TE/g of sample) values compared with its fractionated gastric and intestinal digests. However, the antioxidant capacity of SPC was higher than that determined (TEAC and ORAC values of 0.49 and 0.11 µmol TE/g, respectively) in an ethanolic extract obtained from SI seeds [

40].

In both assays, the antioxidant activity increased significantly after the action of gastric and pancreatic enzymes. The highest antioxidant capacity was shown by GD2, followed by ID3, and ID2 fractions. These results were consistent with Zhan and coworkers that reported ORAC values of 363.01, 313.62, and 264.74 µmol TE/g for the glutelin, albumin, and globulin fractions, respectively, representing more than double compared to the same non-digested Osborne protein fractions [

15]. Similarly, the TEAC values of a SI protein concentrate increased with the hydrolysis time and the sequential use of two enzymes compared to single-step hydrolysis. Values of 770, 950, 1100, 1190, and 1530 μmol TE/g were obtained after 240 min, employing Flavourzyme, Neutrase, Alcalase, Alcalase + Neutrase, and Alcalase + Flavourzyme, respectively [

13]. Also, the antioxidant capacity assessed using the DPPH radical method in a SI protein concentrate was 17.80 μmol TE/g. However, this activity increased upon hydrolyzing with Calotropis (27.46 μmol TE/g) and crude papain (23.15 μmol TE/g) [

11]. These findings demonstrated that the hydrolysis process of SIPC-proteins enhanced their antioxidant capacity by releasing bioactive peptides capable of counteracting oxidative agents.

3.3. Ex Vivo Antioxidant Capacity

3.3.1. Cell Viability

The MTT assay was performed to evaluate the dose-dependent effect of SPC and its digests fractions on the viability of RAW264.7 macrophages and to select those non-toxic doses (>75% viability) for subsequent experiments. The MTT assay is based on the ability of mitochondrial enzymes of viable cells to convert the MTT salt into its blue formazan derivative. The amount of formazan generated was directly proportional to the number of live cells [

41]. Doses ranged from 16 to 1000 μg sample/mL for 24 h were assayed. A significant dose-dependent reduction in cell viability was observed for all samples, except for ID2 and ID3 fractions, as shown in

Figure 2. Doses of 500-1000, 1000, 1000, and 250-1000 μg/mL were found to be cytotoxic for SPC, GD1, GD3, and ID1 fractions, respectively, resulting in a decrease in cell viability higher than 25% compared to the control treatment. These findings were consistent with previous reports for an albumin fraction obtained from SIPC, demonstrating that cellular viability in RAW264.7 macrophages significantly decreased when exposed to concentrations exceeding 320 μg/mL [

42]. In contrast, GD2, ID2, and ID3 fractions showed no cytotoxic effects at all assayed doses.

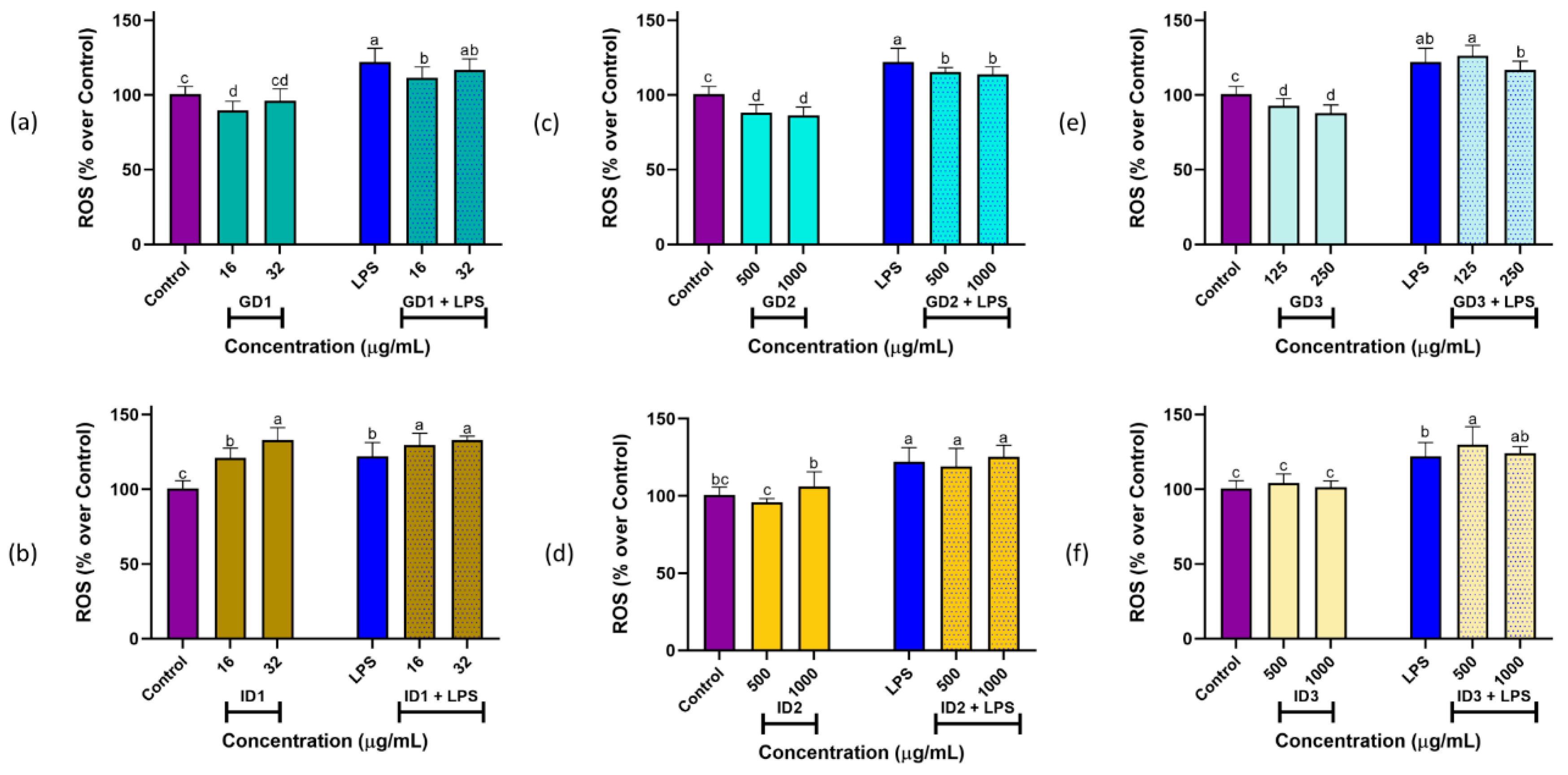

3.3.2. Intracellular ROS Production in RAW264.7 Cells

To assess the ROS scavenging ability of peptides in SPC and its digest fractions, a DCFH-DA assay was conducted. The ROS production values of RAW 264.7 cells under basal and stimulated conditions are shown in

Figure 3. LPS treatment at 10 µg/mL significantly (

P < 0.05) induced ROS production (122.12 ± 9.17%) in comparison with control cells (100.00 ± 4.95%). These ROS-inducing effects had been previously reported [

20,

43]. In the case of SPC sample (data not plotted), under basal conditions, treatment with 63 µg/mL did not produce any significant effect on ROS levels (106.35 ± 10.43%,

P > 0.05). However, at 125 µg/mL, oxidative damage increased significantly (118.57 ± 7.80,

P < 0.05). Conversely, under stimulated conditions, both 63 and 125 µg/mL of SPC significantly potentiated LPS-inducing effects up to ROS levels of 155.81 ± 9.42% and 131.20 ± 10.87%, respectively. This result indicated that SPC induced oxidative damage in macrophages, as was also evidenced by the high cytotoxic effects exerted by this sample.

When basal RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with two concentrations of each GD1, GD2, and GD3 fractions (

Figure 3a,c,e, respectively), a significant protective effect against oxidative stress was observed, leading to reduced ROS levels (

P < 0.05) compared with control treatment. The radical scavenging activity demonstrated in this study through

in vitro assays for these fractions could contribute to the observed ROS-reducing effects. Also, under stimulated conditions, both fractions GD1 (16 µg/mL) and GD2 (500 and 1000 µg/mL) significantly reverted the inducing damage caused by LPS (

P < 0.05), while fraction GD3 at two assayed doses did not exert any effects. In the case of intestinal fractions, under basal conditions, ID1 exerted significant ROS-inducing effects (

P < 0.05), while ID2 and ID3 did not exert any effect at both doses of 500 and 1000 µg/mL (

P > 0.05). Finally, under stimulated conditions, ID1 at both doses and ID3 at 500 µg/mL potentiated the ROS-inducing effects of LPS (

P < 0.05), whereas ID2 and the highest dose of ID3 showed the same effect (

P > 0.05) as LPS treatment alone (

Figure 3b,d,f).

The antioxidant activity of peptides could be attributed to their amino acid sequence, with residues tyrosine, methionine, histidine, and phenylalanine being demonstrated to exert an important contribution [

13]. Considering that pepsin cleaves peptide bonds of side chains of aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids such as leucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine [

44], a significant free radical scavenging is attributed to the π-bonds in the structure of these amino acids, which act similarly to antioxidants such as flavonoids, polyphenols, and carotenoids, known for their conjugated π-systems in their molecular structure [

6]. This could be the main reason of the protective effects exerted by gastric digest fractions in comparison with intestinal digest fractions.

3.4. Peptidome Characterization

The peptidomes of the SPC and digests-derived fractions were characterized using the robust search engine PEAKS Studio, known for accurate

de novo sequencing by directly computing the optimal sequence from all possible combinations of amino acids for peptides derived from their tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectra [

45]. The key findings are summarized in

Table 2. After gastric and intestinal digestion, a notable increase in the number of peptides was observed. Moreover, there was a notable rise in the percentage of peptides with medium chain lengths (6-10 amino acids) in GD3, ID2, and ID3 fractions compared to SPC. The proportion of short peptides (2-5 AA) remained consistent across samples, with a slight decrease observed for long peptides (> 10 AA). This study pioneered the use of

de novo sequencing to analyze the SI proteome. The ALC of 85% used as a benchmark ensured accurate peptide identification.

3.5. In Silico Analysis

3.5.1. Antioxidant Potential of Resistant Peptides

Following LC-MS/MS analysis,

de novo peptides derived from the gastrointestinal digest (ID fraction) were compared with those from the SPC to identify peptides resistant to the complete digestive process. A total of 416 peptides (data not shown) were identified with a cosine similarity value greater than 0.95 and a maximum sequence length difference of 8 amino acids. The

in vitro and

ex vivo assay results demonstrated that both gastric and intestinal digests exhibited high antioxidant activity. There is a particular interest in resistant peptides due to their potential bioavailability. In this context, the AnOxPP tool, employing artificial intelligence, predicted peptides with antioxidant properties based on quantitative structure-activity relationship [

7]. Out of the 416 peptides identified as resistant, 367 were classified as antioxidants, while the remaining 49 were classified as non-antioxidants. Then, the AnOxPePred web server was utilized to assess the probability of peptides to scavenge free radicals (FRS), selecting the top 20 peptides for subsequent analysis as suggested in the literature [

26].

The antioxidant probabilities of resistant peptides, as well as their physicochemical characteristics evaluated using bioinformatics tools are presented in

Table 3. The peptides SVMGPYYNSK and EWGGGGCGGGGGVSSLR exhibited the highest FRS values, and the scores of the selected peptides ranged from 0.47 to 0.60. These findings were consistent with values reported for peptides initially identified in fish hydrolysates, and subsequently chemically synthesized and validated as antioxidants in

in vitro assays [

46]. Physicochemical characteristics of peptides such as hydrophobicity, attributed to amino acid residues like proline, leucine, valine, and alanine, enhances antioxidant activity by facilitating interactions with free radicals at water-lipid interfaces. Conversely, hydrophilicity provided by amino acid residues such as glycine promotes peptide flexibility and acts as hydrogen donors to neutralize ROS [

7]. The peptides RHWLPR and LQDWYDK exhibited high solubility in water and contained significant proportions of aromatic amino acids (33.3% and 28.6%, respectively). These aromatic residues can stabilize ROS by electron or proton transfer, as previously reported [

47].

Seventy-five percent of the peptides selected exhibited 100% coil structures, recently identified as predictive of bioactive peptides [

47]. According to predictions from ToxinPred and AllerTop, these peptides were assessed as non-toxic and non-allergenic (data not shown). This property might be attributed to their length and secondary structure, particularly the random coil and extended strand conformations, known for their lower toxicity [

48].

3.5.2. Bioavailability Analysis of Antioxidant Peptides

Peptide bioavailability indicates effective utilization and intact systemic circulation post oral ingestion [

49]. Traditional drug development assesses absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), with Lipinski's rule-of-five (Ro5) setting thresholds for oral drug suitability (drug-likeness concept) based on physicochemical properties (MW, coefficient between n-octanol and water, water solubility, hydrogen donor and acceptor) [

50]. Early ADME minimizes pharmacokinetic failures in clinical trial phases. SwissADME uses machine learning to predict small molecule pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness [

32].

Table 4 presents bioavailability parameters for the selected peptides. Eleven peptides lacked established parameters due to size limitations (< 200 characters) in Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry Specification (SMILES). Drug-likeness considers physicochemical traits like lipophilicity, assessed by the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (log

Po/w) [

32]. The log

Po/w values obtained for the selected peptides ranged between -2.2 and -10.14. These values classified the peptides as lipophilic, and they did not exceed the threshold established in Ro5: log

Po/w < 4.15. The parameter log

S estimated a molecule's water solubility; values more negative (< −10 per Ro5) indicated greater insolubility. All selected peptides exhibited very-high solubility. However, they did not meet Ro5 thresholds for MW (

Table 3), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), and hydrogen bond donors (HBD): MW between 150 and 500 g/mol, ≤ 10 HBA, and ≤ 5 HBD, resulting in Lipinski violations.

The Bioavailability Score assessed the likelihood of peptides achieving 10% oral bioavailability or measurable Caco-2 permeability based on factors like total charge, topological polar surface area, and Lipinski filter violations [

32]. The selected peptides had low scores in this parameter, ranging between 0.11 and 0.17. Finally, predictions for passive gastrointestinal absorption focused on the ability of a molecule to act as a substrate or inhibitor of proteins that govern pharmacokinetic behaviors in humans, and the selected peptides exhibited a low classification.

Despite the antioxidant peptides not meeting optimal bioavailability criteria for small molecules according to Ro5, their bioactivity aligned with literature findings. These peptides might bind to cell surface receptors, initiating specific intracellular effects similar to proteins and antibodies, potentially benefiting gastrointestinal tissues [

51]. Due to inherent challenges in peptide drug-likeness development, membrane impermeability and poor

in vitro stability—over 90% of peptides in active clinical development target extracellular receptors [

52]. As shown in

Table 4, precisely 90% of the selected peptides could be studied under this approach. Additionally, the peptides RHWLPR and ALEETNYELEK showed potential as cell-penetrating peptides, facilitating the transport of high MW polar molecules as 'Trojan horses' [

33]. Another critical parameter is the peptides' half-life in blood, averaging 816 seconds (13.6 minutes), that is consistent with other bioactive peptides and circulating hormones [

47].

4. Conclusions

Alkali-soluble proteins from SPC underwent simulated gastrointestinal digestion using the INFOGEST 2.0 protocol. In vitro assays, including ABTS and ORAC, revealed that hydrolysis released bioactive peptides with strong antioxidant properties. These effects were corroborated in ex vivo assays, where SPC digests reduced ROS levels, alleviated stress, and mitigated dysfunction in RAW264.7 cells. This study marked the first use of de novo sequencing to assess the SI peptidome. Despite low bioavailability indices predicted by in silico tools due to challenges like membrane impermeability and low in vitro stability, the peptides showed promise for extracellular targets and drug delivery systems. Future research should focus on chemical synthesis of identified sequences SVMGPYYNSK, EWGGGGCGGGGGVSSLR, RHWLPR, LQDWYDK, and ALEETNYELEK to validate their antioxidant activity and bioavailability through experimental and in vivo models.

Author Contributions

E. Torres-Sánchez: Investigation; Writing - Original Draft; Formal analysis; Methodology; Conceptualization. I. Lorca-Alonso and S. González-de la Fuente: Software. B. Hernández-Ledesma: Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. L.-F. Gutiérrez: Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sistema General de Regalías (SGR) [BPIN project number 2020000100169].

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions of confidential information that they are immersed but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Sistema General de Regalías. The authors would like to acknowledge the Biocomputational Analysis Core Facility (SABio) at the Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa (CBM, CSIC-UAM) for their role in the data analysis for identifying peptide sequences that are potentially resistant to in vitro gastrointestinal digestion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Fernández-Tome, S.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Functionality of Soybean Compounds in the Oxidative Stress-Related Disorders. In Gastrointestinal Tissue; Elsevier Inc., 2017; pp. 339–353 ISBN 9780128053775.

- Indiano-Romacho, P.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Amigo, L.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Multifunctionality of Lunasin and Peptides Released during Its Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intiquilla, A.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Guzmán, F.; Alvarez, C.A.; Zavaleta, A.I.; Izaguirre, V.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Novel Antioxidant Peptides Obtained by Alcalase Hydrolysis of Erythrina Edulis (Pajuro) Protein. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2420–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, N.; Dyer, J.M.; Richena, M.; Domigan, L.J.; Gerrard, J.A.; Clerens, S. Self-Assembling Bioactive Peptides for Gastrointestinal Delivery—Bioinformatics-Driven Discovery and in Vitro Assessment. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 2927–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-tomé, S.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Current State of Art after Twenty Years of the Discovery of Bioactive Peptide Lunasin. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-García, G.; Dublan-García, O.; Arizmendi-Cotero, D.; Gómez Oliván, L.M. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Peptides Derived from Food Proteins. Molecules 2022, 27, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, D.; Jiao, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Liang, G. Prediction of Antioxidant Peptides Using a Quantitative Structure−activity Relationship Predictor (AnOxPP) Based on Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network and Interpretable Amino Acid Descriptors. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravel, A.; Doyen, A. The Use of Edible Insect Proteins in Food: Challenges and Issues Related to Their Functional Properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 59, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençdağ, E.; Görgüç, A.; Yılmaz, F.M. Recovery of Bioactive Peptides from Food Wastes and Their Bioavailability Properties. Turkish J. Agric. - Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawdkuen, S.; Ketnawa, S. Extraction, Characterization, and Application of Agricultural and Food Processing By-Products. In Food Preservation and Waste Exploitation; Socaci, S.A., F?rca?, A.C., Aussenac, T., Laguerre, J.-C., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2019; pp. 1–32.

- Rawdkuen, S.; Rodzi, N.; Pinijsuwan, S. Characterization of Sacha Inchi Protein Hydrolysates Produced by Crude Papain and Calotropis Proteases. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 98, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanangul, S.; Sangsawad, P.; Alashi, M.A.; Aluko, R.E.; Tochampa, W.; Chittrakorn, S.; Ruttarattanamongkol, K. Antioxidant Activities of Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia Volubilis l.) Protein Isolate and Its Hydrolysates Produced with Different Proteases. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 15, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos, R.; Pedreschi, R.; Campos, D. Enzyme-Assisted Hydrolysates from Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia Volubilis) Protein with in Vitro Antioxidant and Antihypertensive Properties. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A Standardised Static in Vitro Digestion Method Suitable for Food- an International Consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Gong, F.; Hao, L.; Wu, H. The Antioxidant Activity of Protein Fractions from Sacha Inchi Seeds after a Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. LWT 2021, 145, 111356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, T.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X. Antioxidant and Hypoglycemic Activity of Sacha Inchi Meal Protein Hydrolysate. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, S.; Cattivelli, A.; Conte, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Application of a Combined Peptidomics and In Silico Approach for the Identification of Novel Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV-Inhibitory Peptides in In Vitro Digested Pinto Bean Protein Extract. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Sánchez, E.G.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Gutiérrez, L.-F. Sacha Inchi Oil Press-Cake: Physicochemical Characteristics, Food-Related Applications and Biological Activity. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F. INFOGEST Static in Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Galvez, A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Evaluation of the Multifunctionality of Soybean Proteins and Peptides in Immune Cell Models. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Shao, J.; Shu, X.; Jia, J.; Ren, X. Macrophage Immunomodulatory Activity of the Polysaccharide Isolated from Collybia Radicata Mushroom. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBel, C.P.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Bondy, S.C. Evaluation of the Probe 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescin as an Indicator of Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Oxidative Stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992, 5, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Sánchez, E.; Morato, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Gutiérrez, L.-F. Proteomic Analysis of the Major Alkali-Soluble Inca Peanut (Plukenetia Volubilis) Proteins. Foods 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, T.C.; Abreu, J.P.; Oliveira, J.P.S.; Macedo, A.F.; Rodríguez-Vega, A.; Tonin, A.P.; Cardoso, F.S.N.; Meurer, E.C.; Koblitz, M.G.B. Bioactive Properties of Peptide Fractions from Brazilian Soy Protein Hydrolysates: In Silico Evaluation and Experimental Evidence. Food Hydrocoll. Heal. 2023, 3, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, L. Distance Weighted Cosine Similarity Measure for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning – IDEAL 2013; Yin, H., Tang, K., Gao, Y., Klawonn, F., Lee, M., Weise, T., Li, B., Yao, X., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 611–618.

- Olsen, T.H.; Yesiltas, B.; Marin, F.I.; Pertseva, M.; García-Moreno, P.J.; Gregersen, S.; Overgaard, M.T.; Jacobsen, C.; Lund, O.; Hansen, E.B.; et al. AnOxPePred: Using Deep Learning for the Prediction of Antioxidative Properties of Peptides. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, D.; Singh, S.; Mehta, A.; Agrawal, P.; Raghava, G.P.S. In Silico Approaches for Predicting the Half-Life of Natural and Modified Peptides in Blood. PLoS One 2018, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lear, S.; Cobb, S.L. Pep-Calc.Com: A Set of Web Utilities for the Calculation of Peptide and Peptoid Properties and Automatic Mass Spectral Peak Assignment. J. Comput. Aided. Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, I.; Seno, F.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Trovato, A. PASTA 2.0: An Improved Server for Protein Aggregation Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kapoor, P.; Chaudhary, K.; Gautam, A.; Kumar, R.; Consortium, O.S.D.D.; Raghava, G.P.S. In Silico Approach for Predicting Toxicity of Peptides and Proteins. PLoS One 2013, 8, e73957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.N.; Krutz, N.L.; Limviphuvadh, V.; Lopata, A.L.; Gerberick, G.F.; Maurer-Stroh, S. AllerCatPro 2.0: A Web Server for Predicting Protein Allergenicity Potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W36–W43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, E.C.L.; Santana, K.; Josino, L.; Lima e Lima, A.H.; de Souza de Sales Júnior, C. Predicting Cell-Penetrating Peptides Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Navigating in Their Chemical Space. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathe, S.K.; Kshirsagar, H.H.; Sharma, G.M. Solubilization, Fractionation, and Electrophoretic Characterization of Inca Peanut (Plukenetia Volubilis L.) Proteins. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2012, 67, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čepková, P.H.; Jágr, M.; Viehmannová, I.; Dvořáček, V.; Huansi, D.C.; Mikšík, I. Diversity in Seed Storage Protein Profile of Oilseed Crop Plukenetia Volubilis from Diversity in Seed Storage Protein Profile of Oilseed Crop Plukenetia Volubilis from Peruvian Amazon. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2019, 21, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, S.K.; Hamaker, B.R.; Sze-Tao, K.W.C.; Venkatachalam, M. Isolation, Purification, and Biochemical Characterization of a Novel Water Soluble Protein from Inca Peanut (Plukenetia Volubilis L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4906–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcacundo, R.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Release of Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV, α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Peptides from Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) during in Vitro Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 35, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Gutiérrez, L.-F. Isolation and Characterization of Protein Fractions for Valorization of Sacha Inchi Oil Press-Cake. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Dávalos, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Amigo, L. Preparation of Antioxidant Enzymatic Hydrolysates from α-Lactalbumin and β-Lactoglobulln. Identification of Active Peptides by HPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Borges, L.B.; Sartim, M.A.; Carreño Gil, C.; Vilela Sampaio, S.; Viegas Rodrigues, P.H.; Regitano-d’Arce, M.A.B. Sacha Inchi Seeds from Sub-Tropical Cultivation: Effects of Roasting on Antinutrients, Antioxidant Capacity and Oxidative Stability. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 4159–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Fornasiero, M.C.; Isetta, A.M. MTT Colorimetric Assay for Testing Macrophage Cytotoxic Activity in Vitro. J. Immunol. Methods 1990, 131, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wen, J.; Ma, X.; Lin, F.; Jiang, Z.; Du, B. Structural, Functional Properties and Immunomodulatory Activity of Isolated Inca Peanut (Plukenetia Volubilis L.) Seed Albumin Fraction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca-Oliveira, G.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J.; Morato, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Contribution of Proteins and Peptides to the Impact of a Soy Protein Isolate on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation-Associated Biomarkers in an Innate Immune Cell Model. Plants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, N. Rapid Peptides Generator: Fast and Efficient in Silico Protein Digestion. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 2020, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Zhang, K.; Hendrie, C.; Liang, C.; Li, M.; Doherty-Kirby, A.; Lajoie, G. PEAKS: Powerful Software for Peptide de Novo Sequencing by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 17, 2337–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaha, A.; Wang, B.-S.; Chang, Y.-W.; Hsia, S.-M.; Huang, T.-C.; Shiau, C.-Y.; Hwang, D.-F.; Chen, T.-Y. Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides with Antioxidative Capacity, Xanthine Oxidase and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity. Processes 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-de la Rosa, T.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Rivero-Pino, F. Production, Characterisation, and Biological Properties of Tenebrio Molitor-Derived Oligopeptides. Food Chem. 2024, 450, 139400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, S.S.; Hosseini, H.M.; Mirhosseini, S.A. Evaluation of Anti-Endotoxin Activity, Hemolytic Activity, and Cytotoxicity of a Novel Designed Peptide: An In Silico and In Vitro Study. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2024, 30, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larder, C.E.; Iskandar, M.M.; Kubow, S. Assessment of Bioavailability after in Vitro Digestion and First Pass Metabolism of Bioactive Peptides from Collagen Hydrolysates. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 43, 1592–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, H.S.; Murti, T.W.; Agus, A.; Pertiwiningrum, A. The Exploration of Bioactive Peptides That Docked to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein from Goats’ Milk Beta-Casein by In Silico. Molekul 2023, 18, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide Therapeutics: Current Status and Future Directions. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic Peptides: Current Applications and Future Directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).