1. Introduction

Nowadays, the relationship between human health and gut microbiota is considered a key target in the study and treatment of many diseases [

1]. The community of thousands of highly diverse microorganisms that live throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract has shown to be involved in numerous trophic functions by being a regulatory element of epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation, enhancing the intestinal mucosal barrier and collaborating with the immune system in the protection against antigens and pathogenic germs, among others [

2]. In addition, one of its most attractive roles is the regulation of metabolic and nutritional functions such as the fermentation of indigestible fiber from the diet, the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFA) and vitamins, and the absorption of ions, which makes the metabolites and soluble factors resulting from its activity have a special interest for human health [

3]. Moreover, its multifunctionality and complex nature has expanded the number of factors that could be involved in maintaining its homeostasis with the host, as well as the number of strategies that attempt to modulate or influence its behavior [

4]. In fact, a dysbiosis state or imbalances in its composition have been hypothesized as contributing factors in the development of chronic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease and obesity, among others [

5]. Therefore, the interaction between gut microbiota and its influencing factors such as diet, plays an important role to maintain intestinal homeostasis, which ultimately affects the host’s health.

The current interest of consumers in sustainable and health-beneficial products as well as the growth of the world’s population and impact of the food industry on the environmental resources, has led global health organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to recommend a transition of the existing eating pattern to one more focused on the consumption of sustainable functional foods. This circumstance is prompting an ongoing worldwide search for alternative sources of bioactive compounds [

6]. Among the different options being evaluated, microalgae stand out due to their sustainable nature and associated health benefits attributed to the presence of potential bioactive compounds capable of exhibiting antioxidant, antitumor, regenerative, antihypertensive, neuroprotective and immunostimulant effects [

7,

8]. The consumption of some microalgae species such as

Arthrospira platensis, Chlorella vulgaris and

Tetraselmis chuii has been already approved by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). However, there are other species like

Nannochloropsis gaditana that are not yet approved, but their promising potential makes them a new niche to explore.

N. gaditana is a green, unicellular, subspherical, marine microalgae that has been mainly used for wastewater treatment, animal feeding, aquaculture and the extraction of bioactive lipids, mostly omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [

9]. Nevertheless, the studies focused on the health benefits of other compounds present in

N. gaditana are still scarce. To date, the studies that demonstrate the prebiotic and postbiotic capacity of microalgae are limited to the effects of oligosaccharides isolated from these organisms on the growth of specific probiotic cultures. In the study carried out by de Medeiros et al. 2021 [

10], the digests of different microalga species showed selective prebiotic effects, stimulating the proliferation

of Lactobacillus-Enterococcus spp. and

Bifidobacterium spp. and inhibiting the growth of Prevotellaceae-Bacteroidaceae,

Clostridium histolyticum, Eubacterium rectale, and

Clostridium coccoides. A more recent study carried out by these researchers demonstrated the stimulating effect of

A. platensis on the growth and metabolic activity of

Lb. acidophilus to a greater extent than that exerted by traditional fructooligosaccharides [

11]. Additionally, a pre-clinical study with

Phaeodactylum tricornutum as a suitable diet for mouse feed, showed positive effects on microbiota composition and SCFA production, suggesting beneficial effects on gut health [

12].

In case of

Nannochloropsis sp., it has demonstrated that the fecal microbiota composition of dogs fed with

N. oculata-supplemented diets was modified by promoting the beneficial

Turicibacter and

Peptococcus genera associated with gut health and activation of the immune system [

13]. Furthermore, research on European seabass (

Dicentrarchus labrax) demonstrated that the microalga

N. oceanica could modulate gut bacterial communities, with beneficial effects on gut homeostasis when combined with other algae like

Gracilaria gracilis [

14]. Specifically, regarding

N. gaditana, inclusion of its hydrolyzate in the

Sparus aurata fish diet, resulted in a beneficial effect on intestinal microbiota beyond its nutritional role without causing significant alterations in intestinal morphology or function [

15,

16]. Although scarce, these results suggest the potential of this microalga and its metabolites to modulate the gut microbiota. Therefore, the main goal of our work was to assess the role of

N. gaditana simulated gastrointestinal digests on human gut microbiota composition and derived metabolites to more comprehensively explore the potential of this microalga as a sustainable modulator agent of human gut microbiota.

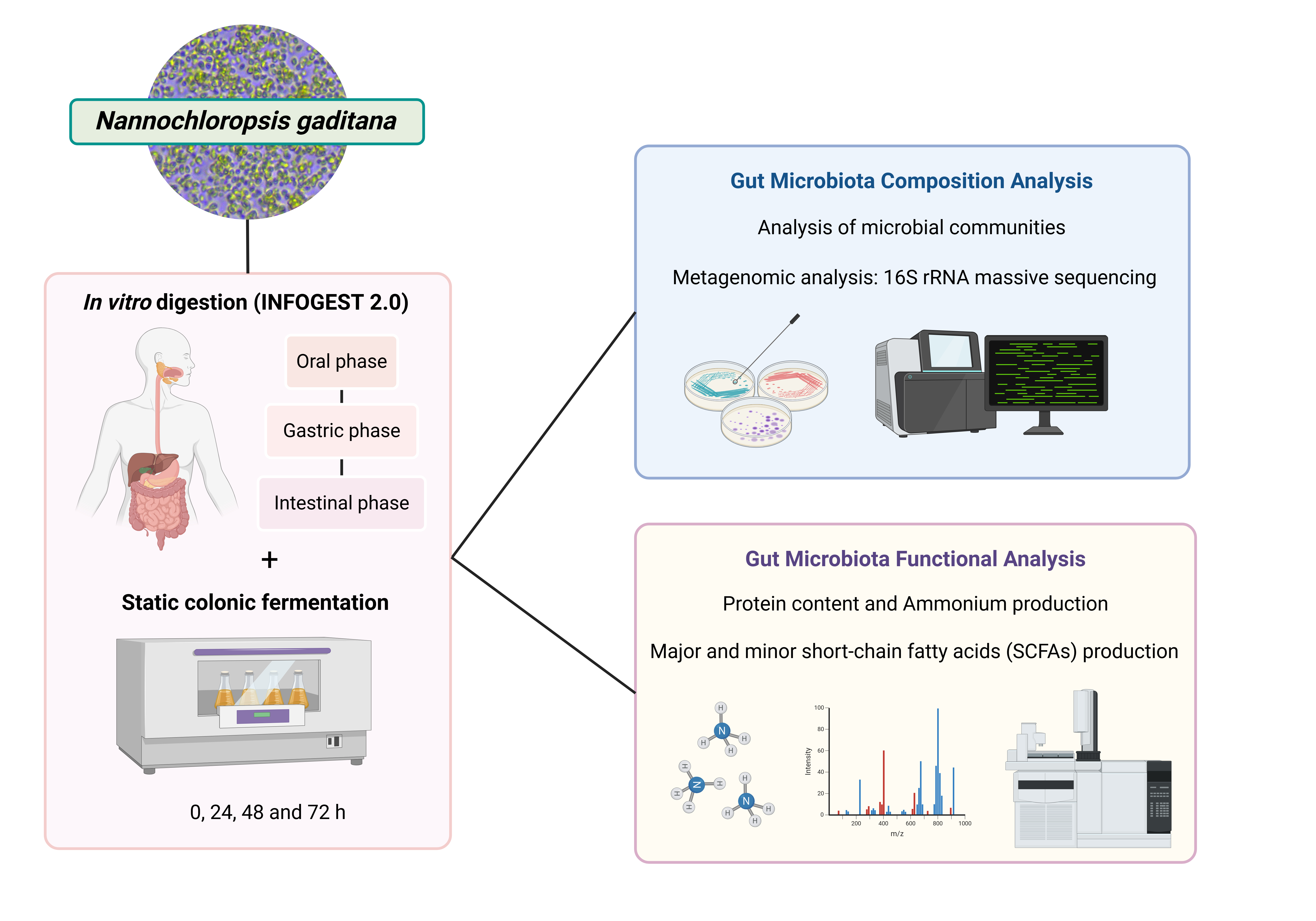

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Reagents

Commercial microalga N. gaditana biomass was kindly supplied by AlgaEnergy S.A. (Madrid, Spain). Pepsin (EC 232-629-3; 3,200 units/mg protein), pancreatin (232-468-9; 8X USP), sodium phosphate (NaH2PO4), disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4), monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4), calcium chloride (CaCl2), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium chloride (NaCl), yeast extract, dipotassium phosphate (K2HPO4), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO4·7H2O), calcium chloride hexahydrate (CaCl2·6H2O), Tween-80, hemin, vitamin K, L-cysteine and phosphoric acid (H3PO4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion

The simulated gastrointestinal digestion of microalgae biomass was conducted following the static

in vitro INFOGEST protocol [

17] with some modifications. A pool of saliva was obtained from 7 healthy volunteers and the simulated gastrointestinal fluid (SGF) and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) were prepared according to the protocol [

17] and preheated at 37°C. Pepsin from porcine gastric mucosa was mixed with ultrapure water to achieve a final concentration of 33 mg/mL. Pancreatin from porcine pancreas was prepared by dissolving it in SIF to a final concentration of 111.1 mg/mL. Finally, bovine bile was mixed with SIF to a final concentration of 12.9 mg/mL. For the recreation of the oral phase, 1 g of dried microalga biomass was dissolved in 500 µL of Milli-Q water, and 4.5 mL of saliva were added. The mixture was then incubated at 37°C with 120 rpm of agitation for 2 min in the Environmental Shaker – Incubator ES 20/60 (Biosan Medical-biological Research & Technologies, Warren, MI, USA). After completing the oral phase, 4.8 mL of SGF were added to the bolus, adjusting the pH to 3.0 with 1 M HCl. Next, 3 µL of 0.3 M CaCl

2 solution and 300 µL of pepsin (ratio enzyme:substrate, E:S, 1:100, w/w) were added to reach a final volume of 12 mL, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C with agitation for 2 h. Moreover, the orogastric chyme was mixed with 5.1 mL of SIF and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 1 M NaOH. Then, 1.5 mL of bile (1:50, w/w), 24 µL of 0.3 M CaCl

2 solution, and 3 mL of pancreatin (E:S 1:3, w/w) were added. The resultant homogenate was incubated at 37°C with agitation for 2 h. At the end of this phase, the enzymes were inactivated at 95°C for 15 min in a Memmert thermostatized bath (Schwabach, Germany), and the digest was then centrifuged in an EppendorfTM Centrifuge 5804R (Hamburg, Germany), at 2000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Two fractions were obtained, the supernatant corresponding to the absorbable fraction that was discarded, and the precipitate corresponding to the non-absorbable fraction (NAF) that was collected. Five digestion replicates were conducted, and the NAFs obtained were pooled and stored at -20°C until the colonic fermentation assays were carried out. 1 g of inulin, a well-known prebiotic carbohydrate [

18,

19], was also digested in quintuplicate, and used as control.

2.3. Static Colonic Fermentation

For the static colonic fermentation, the fecal inoculum was obtained by combining, in a Stomacher 400 Circulator (Seward, USA), 1 g of feces (from a healthy volunteer) with 10 mL of 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0) for 5 min to prepare the fecal slurry [

20]. Then, 3 g of the NAF, 6 mL of the fecal inoculum and 54 mL of colon nutrient medium [peptone water (2 g/L), yeast extract (2 g/L), NaCl (0.1 g/L), K

2HPO

4 (0.04 g/L), KH

2PO

4 (0.04 g/L), NaHCO

3 (2 g/L), MgSO

4·7H

2O (0.01 g/L), CaCl

2·6H

2O (0.01 g/L), Tween 80 (2 mL/L), hemin (0.05 g/L), vitamin K (10 μL/L), L-cysteine (0.5 g/L), bile salts (0.5 g/L), and distilled water were mixed as previously described by Tamargo et al. 2023 [

21]. The fermentation process was carried out for 72 h in triplicate. Anaerobic conditions were followed at 37°C, pH 6.8, continuous agitation (120 rpm), while taking aliquots at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. From each 5 mL-aliquot, 1 mL was used for microbial counts. Other 4 mL were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C using the Eppendorf

TM Centrifuge 5804R (Hamburg, Germany), separating the supernatants that were stored at -20°C for SCFA and ammonium analysis. The pellets were stored at -80°C until the metagenomic analysis.

2.4. Microbial Composition Analysis

2.4.1. Analysis of Microbial Communities

Bacterial counts were performed on general and selective media. Serial dilutions (1/10, 1/100, 1/1000) of the colon digests samples in sterile physiological saline solution (0.9% NaCl) were prepared. Then, spot inoculations (10 μL in triplicate) of each dilution were made on the selected media (BD Difco, NJ, USA): Tryptic Soy Agar (total aerobes), Wilkins Chalgren agar (total anaerobes), MacConkey agar (Enterobacteriaceae family), Enterococcus agar (Enterococcus sp.), De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe agar (lactic acid bacteria), Tryptose Sulfite Cycloserine agar (Clostridium sp.), BBL CHROMAgar (Staphylococcus sp.), Bifidobacterium agar modified by Beerens (Bifidobacterium sp.), and LAMVAB (Lactobacillus sp.). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 to 72 h, depending on the culture medium. All media, except Tryptic Soy Agar and BBL CHROMAgar, were incubated in an anaerobic chamber (BACTRON Anaerobic/Environmental Chamber, Shel Lab, Sheldon Manufacturing Inc., Cornelius, OR, USA). Lastly, the resultant colonies were counted with a colony counter SC6PLUS (Stuart, UK) and the results were expressed as the logarithm of colony-forming units (CFU) per mL. The differences in values were considered significant when they were higher or lower than 1 log (CFU/mL) compared to the control (inulin).

2.4.2. Metagenomic Analysis of Gut Microbiota

Extraction and Quantification of Microbial DNA

The isolation and extraction of the microbial DNA from the precipitates obtained at 0 h and 48 h-fermentation were carried out using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool mini kit (Quiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA integrity was evaluated with the BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the concentration was quantified with the fluorimeter Qubit 3.0 using the dsDNA HS assay (Life Technologies S.A., Alcobendas, Madrid, Spain).

2.4.2.2 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

All the samples underwent amplification of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the Ion 16S Metagenomics kit (Life Technologies S.A.), abled to amplify seven hypervariable regions (V2, V3, V4, V6-7, V8, and V9). Then, libraries were generated by repairing the ends of the amplicons with the Ion Plus Fragment Library kit (Life Technologies S.A.) and attaching DNA molecular identifiers using the Ion Express Barcode Kit Adapters (Life Technologies S.A.). Furthermore, libraries were diluted and underwent clonal amplification by emulsion PCR in the Ion OneTouchTM 2 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and each sample was sequenced using an Ion S5TM System with an Ion 520TM Chip (Life Technologies S.A.).

2.4.2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

Samples were filtered on the platform-specific pipeline incorporated in the Torrent Suite v5.8 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Then, the primers were removed and trimmed the sequences to 165 bp in length using a self-developed Python. FASTQ files were analyzed using QIIME 2 platform and by following Bolyen et al. [

22] and Segata et al. [

23] methodology. Reference-based clustering of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 99% similarity was performed using SILVA 16S database (v138). Relative OTU abundances were computed as percent proportions based on the total number of reads per sample.

α-diversity was assayed calculating four metrics: Observed OTUs, Chao1, and Shannon and Simpson indexes. To study β-diversity, Jaccard dissimilarity index was computed. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was then applied to the resulting dissimilarity matrices, and two-dimensional PCoA plots were used for the visualization of the results.

Taxonomic assignment of the identified OTUs was performed using QIIME2 and SILVA 16S taxonomy. PICURSt2 software package (v2.2.0-b) was used to predict the functional content of microbial communities as Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) ortholog profiles. PICRUSt2 inference relies on 16S rRNA gene sequences and associates OTUs with gene contents. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis was used to identify differentially abundant taxa and functional pathways among groups. Taxa with a relative abundance less than 0.01% were filtered for this analysis.

2.5.1. SCFA Analysis

The SCFA analysis was carried out following García-Villalba et al. [

24] methodology. The supernatants were acidified with 0.5% phosphoric acid and mixed with the internal standard (1.97 mM, 2-methylvaleric acid, Sigma-Aldrich). After extracting the mixture with n-butanol, the analysis was performed using a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with an autoinjector, a DB-WAX capillary column (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and a flame ionization detector. Quantitative data were obtained by calculating the area of each compound relative to the internal standard. The analyses were carried out in triplicate.

2.5.2. Ammonium and Protein Content

The protein concentration of supernatants was carried out by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method, using the Pierce BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions [

25]. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) at concentrations ranging from 50 to 1000 µg/mL was used as standard. The ammonium ion (NH

4+) production was measured using the Photometric Spectroquant® ammonium reagent test (Merck & Co., Kenilworth, NJ, USA), measuring the absorbance at 690 nm using the Biotek SynergyTM HT plate reader (Winooski, VT, USA). A standard curve (2-75 mg NH

4+/L) was used to calculate the content that was expressed as mg NH

4+/L. Both ammonium and protein analyses were carried out in triplicate.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of data from cultured microbial communities, SCFAs, protein and ammonium content were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey test. For the metagenomic analysis, differences among groups were analyzed with a Kruskal–Wallis test or a paired t-test as appropriate. The differences between groups regarding the β diversity were analyzed with a permutation analysis and multiple ANOVA (PERMANOVA) with 999 permutations. LEfSe consisted on the application of a Kruskal-Wallis test to identify taxa with significantly different relative abundances, followed by logarithmic Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score to determine an effect size of each taxon. Finally, the scipy PYTHON package and IBM® SPSS® Statistics software package version 27 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) were used and, for all analyses, differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microbial Composition Analysis

3.1.1. Analysis of Microbial Communities

The effect of the NAFs of

N. gaditana and inulin digests on the total aerobes and anaerobes microbial counts are shown in

Figure 1. In the case of the total aerobes (

Figure 1A), an increase was observed at 24 h in both samples, obtaining values of 8.07 CFU/mL and 8.04 CFU/mL for inulin and

N. gaditana, respectively. After that time, the values measured in the inulin sample remained constant until the end of colonic fermentation (8.25 CFU/mL), while a significant decrease was observed in the microalga sample, reaching 5.34 CFU/mL at 72 h-fermentation. Regarding total anaerobes population, both samples experienced an increase all through the fermentation and the differences between inulin and microalga samples were not significant (

Figure 1B).

In relation to the specific microbial plate counts, the NAF from

N. gaditana also exerted multiple effects. Thus, the

Enterobacteriaceae population decreased significantly from 6.42 CFU/mL at 24 h to 4.32 CFU/mL at the end of the fermentation process (

Figure 1C). However, the count reached after 24 h-fermentation with the NAF from inulin digest (7.58 CFU/mL) remained constant until the end of the fermentation (7.84 CFU/mL). Moreover, the

Staphylococcus sp. population increased after 24 h (6.20 CFU/mL) when inulin was added to the medium, remaining constant until the fermentation was completed (6.53 CFU/mL) (

Figure 1D). Nevertheless, when the NAF from

N. gaditana digest was added, a significant decrease in the microbial population was observed, decreasing to a value of 5.06 CFU/mL at 72 h.

Differences between the effects of microalga and inulin NAF were also observed for lactic acid bacteria. In N. gaditana, there was a slight increase in the microbial population at 24 h (6.61 CFU/mL) that decreased at 48 and 72 h, with values of 5.31 and 5.13 CFU/mL, respectively. However, in the case of inulin, the lactic acid bacteria increased during the fermentation until reaching a final value of 6.29 CFU/mL. No differences were observed for Enterococcus sp., Clostridium sp. and Bifidobacterium sp. microbial counts between N. gaditana and inulin at any of the times studied.

The information available on the effects of microalgae

N. gaditana digests on microbial counts was limited. Only, in the work of Medeiros et al. 2021 [

10], a significant decrease of the relative abundances of intestinal inflammation related bacteria like

Eubacterium rectale,

Clostridium histolyticum,

Prevotellaceae,

Bacteroidaceae, and some

Porphyromonadaceae was observed in the colonic media when fructooligosaccharides and different microalgae digests were tested, suggesting microalgae potential ability to difficult the growth of inflammation related bacteria groups like

Enterobacteriaceae and

Staphylococcus sp.

The discrepancies found with our results could mainly be related to the microalgae strain, the growing conditions, and/or the experimental design. Furthermore, studies on the growth of

N. gaditana have shown that both, the microalga and its microbiome can adapt to low oxygen environments [

26,

27]. During

in vitro fermentation, a low-oxygen environment is established, and factors such as the native microbiological load of

N. gaditana, that could have resisted the digestive process should not be discarded. Moreover, the phenolic compounds bound to the undigested polysaccharides and proteins in the microalga-NAF could interact with gut microbiota after digestion. This interaction could produce energy that supports primary microbial consumers and their syntrophic partners, also exhibiting the well-known gut-modulating effects of phenolic compounds [

28,

29,

30].

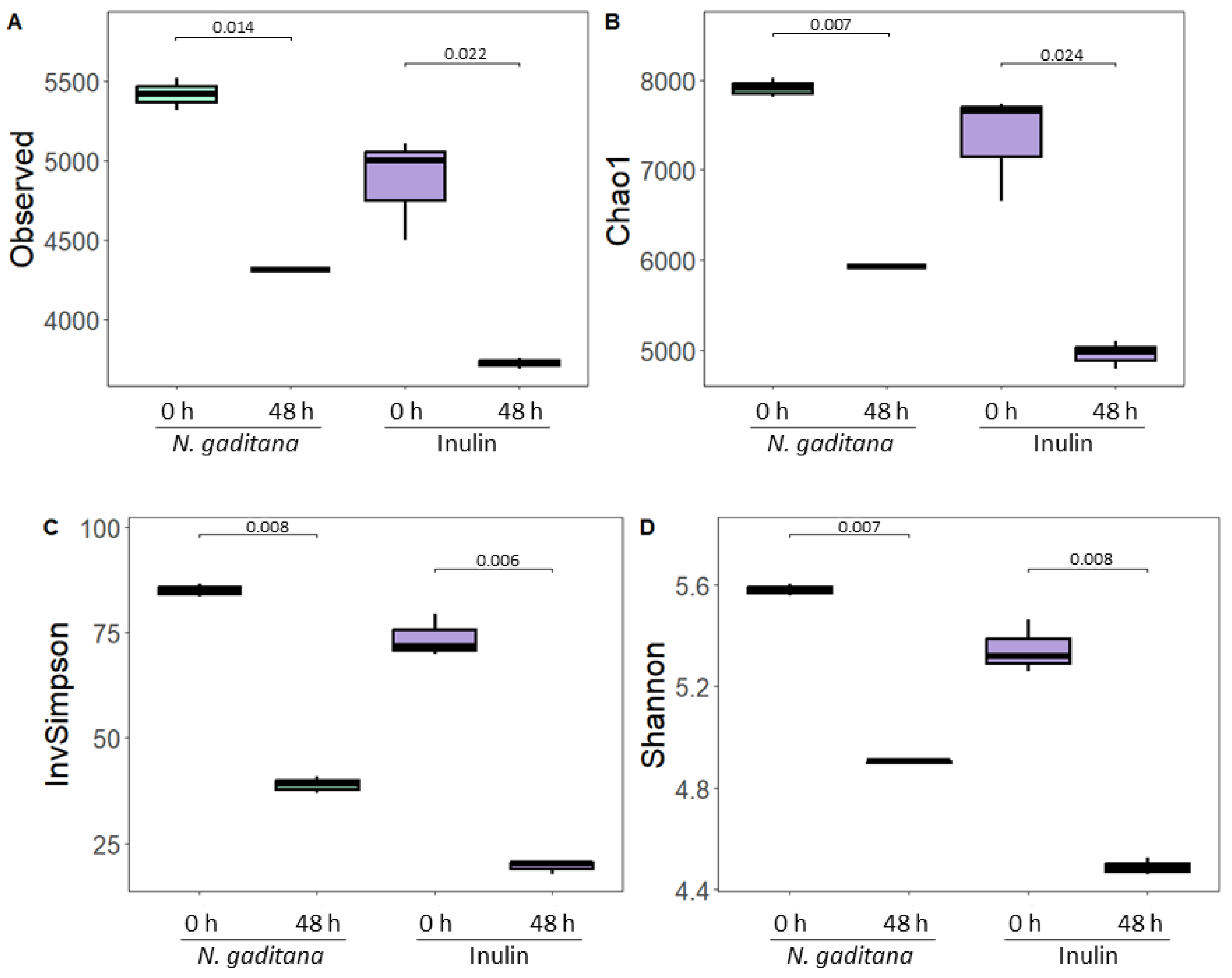

3.1.2. Metagenomic Analysis of Gut Microbiota

The effects of simulated gastrointestinal digests from

N. gaditana on gut microbiota composition were investigated by assayed bacterial community changes after 48 h of colonic fermentation, using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Initially, α-diversity, a measurement that considers the internal biodiversity of each sample considering richness and evenness (

Figure 2A-D), was calculated. For this purpose, the sequence depth in all samples was rarefied. As expected, no significant differences were found neither in terms of richness (observed OTUs and Chao1) nor evenness (Shannon, and Simpson indexes) at the baseline sample (zero time) between

N. gaditana and inulin (

Figure 2A-D). However, after 48 h of fermentation with NAFs from

N. gaditana and inulin, all α-diversity indexes decreased significantly, indicating a reduction in both bacterial richness and evenness. Previous studies have shown a decline in bacterial abundance during fermentation likely due to the competitive inhibition of less dominant strains by others [

31,

32]. Notably, samples treated with

N. gaditana NAFs exhibited higher observed OTUs and Chao1 indexes compared to inulin-treated samples, though their evenness was similar. This suggests that

N. gaditana would have a distinct impact on α-diversity compared to inulin.

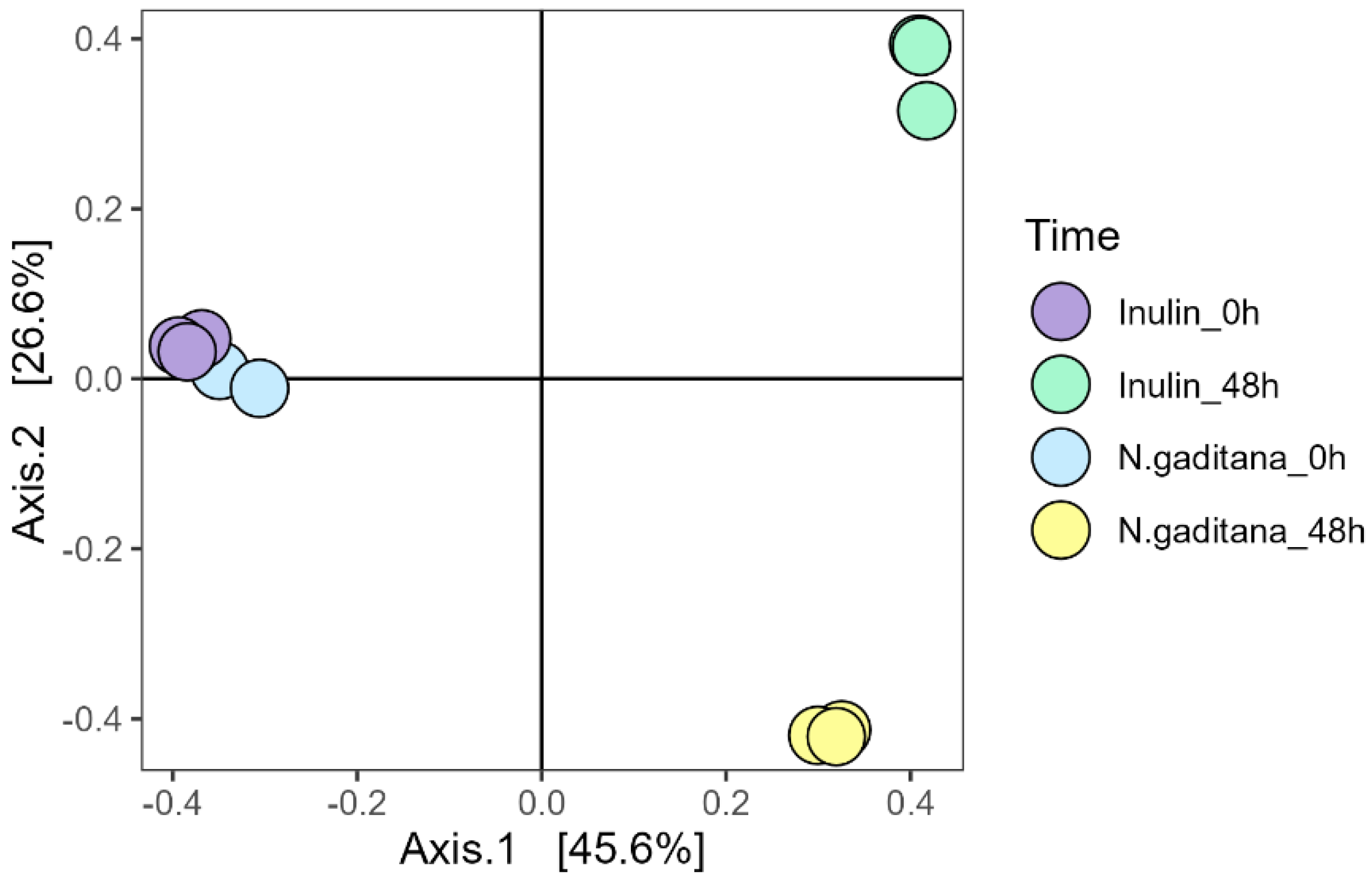

Regarding β-diversity, which accounts for differences between groups, all samples clustered at the beginning of the fermentation, indicating no initial differences (

Figure 3). However, after 48 h of fermentation, both

N. gaditana and inulin samples displayed changes in bacterial composition relative to the initial time, with significant differences observed between NFA from

N. gaditana compared to that from inulin. The first two principal coordinates explained over 72% of the variation in bacterial communities (

Figure 3). Overall, these data would indicate that fermentation of

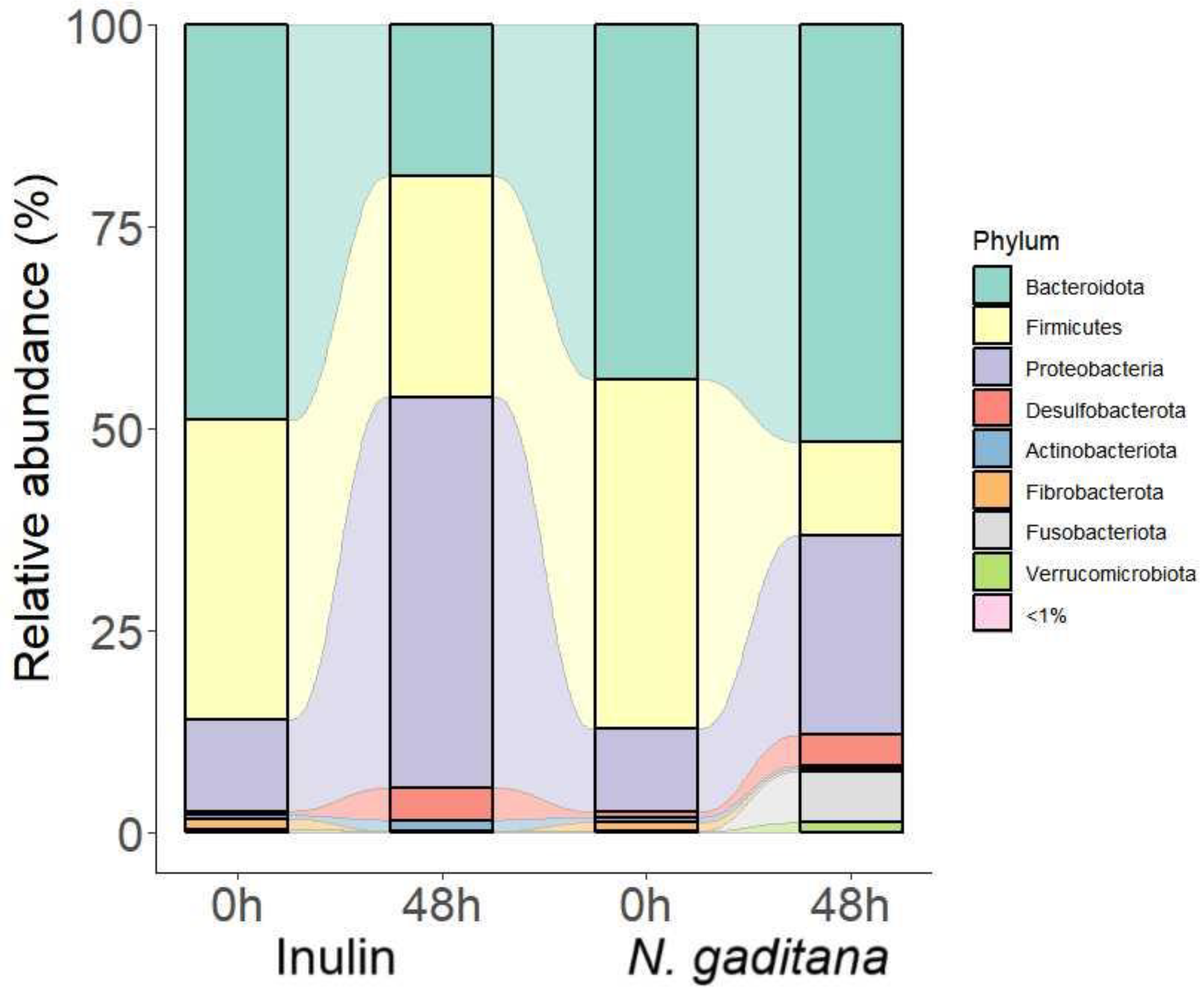

N. gaditana had a specific influence on the gut microbiota consisting in the reduction of α-diversity and alteration of microbial composition. The influence of

N. gaditana on the fecal microbiota was then evaluated by analyzing changes in the taxonomic composition of gut microbiota. Both, at the beginning of the experiment and at 48 h, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, and Proteobacteria were the most abundant phyla, accounting for around the 95% of bacterial taxa (

Figure 4). After fermentation,

N. gaditana and inulin showed a notable increase in Proteobacteria which is consisted with the production of acetic acid that lowers the pH [

33]. Regarding the less abundant phyla, there was an increase in the Fusobacteriota and Verrucomicrobiota phyla in samples treated with

N. gaditana digest, but not in those treated with inulin digest. These data, joined to a less increment in Proteobacteria phylum showed a differential effect of

N. gaditana compared to inulin in the gut microbiota composition.

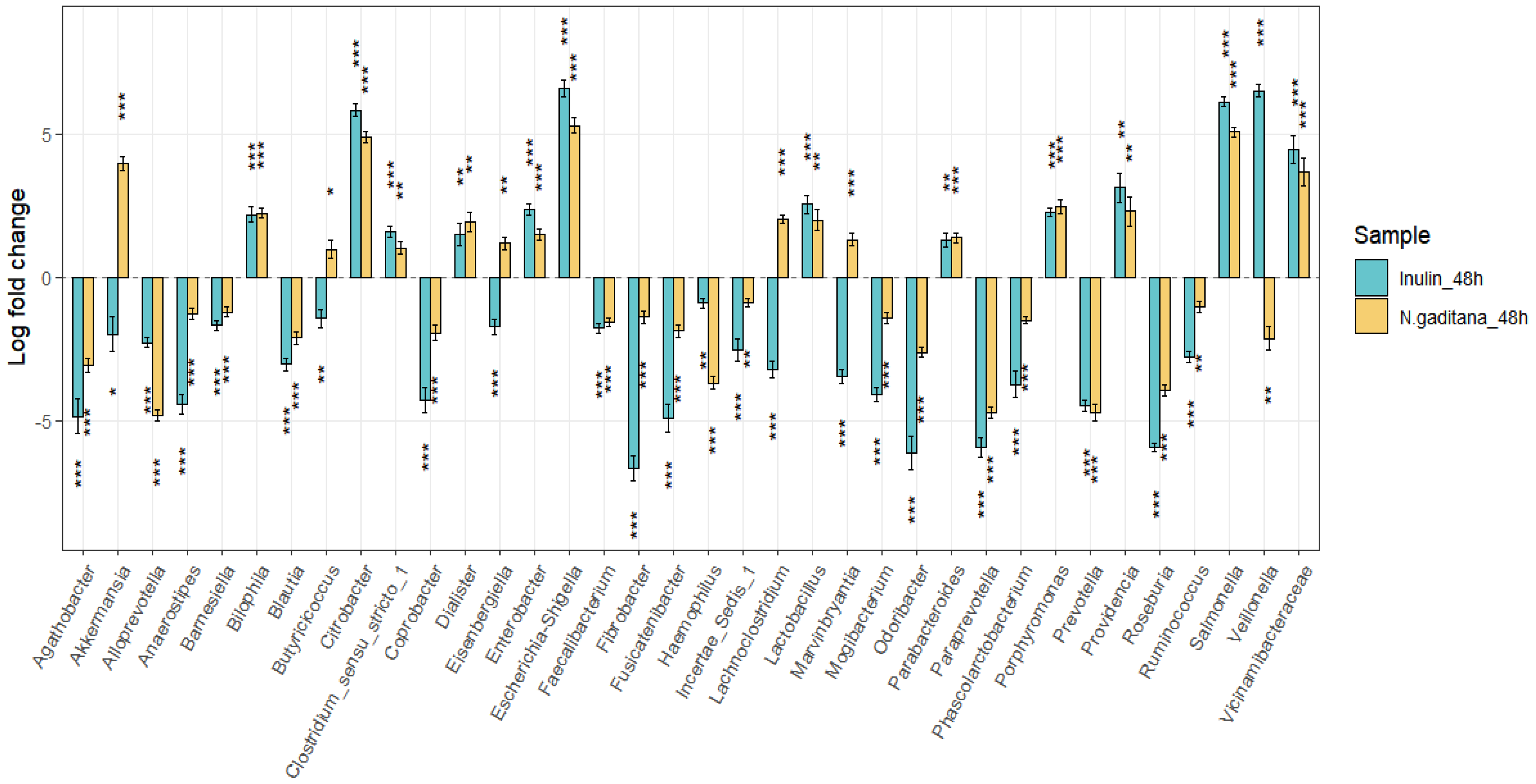

Furthermore, we investigated whether the NAFs from

N. gaditana were associated with more specific changes of the gut microbiota composition. Thirty-six genera differed significantly in abundance in comparison with the beginning of the fermentation (FDR-corrected

P < 0.05) (

Figure 5). Twelve genera were significantly increased and 18 decreased in both

N. gaditana and inulin samples (

Figure 5). However, NAFs from

N. gaditana, but not from inulin, induced an increment of the SCFA-producing bacteria

Akkermansia,

Butyricicoccus,

Eisenbergiella,

Lachnoclostridium, and

Marvinbryantia (

Figure 5).

Two health-related bacteria were identified as key biomarkers in the

N. gaditana fermentations. A significant increase in

Akkermansia was observed, which is known to influence host metabolism by producing SCFAs and regulating energy balance, contributing to protective effects against conditions like obesity and diabetes [

34]. Additionally,

Akkermansia's ability to metabolize mucin may help maintain gut barrier integrity and modulate immune responses. The bacterial genera

Butyricicoccus, Eisenbergiella, Lachnoclostridium, and

Marvinbryantia are key members of the gut microbiota involved in metabolism and inflammation regulation, largely through the production of SCFAs and other metabolites that benefit colonic health and immune modulation.

Butyricicoccus is a key productor of butyrate, an SCFA that strengthens the gut barrier, reduces inflammation, and supplies energy to colonic epithelial cells [

35,

36].

Eisenbergiella and

Lachnoclostridium are linked to the fermentation of complex carbohydrates and may indirectly support butyrate production by supplying metabolites that other bacteria can convert into SCFAs [

37,

38].

Lachnoclostridium also participates in the regulation of the immune system. In addition,

Marvinbryantia is a cellulose-degrading bacterium that produces propionate and acetate, SCFAs known to positively influence glucose and lipid metabolism [

39]. Importantly, in human gut microbiota, acetate is the predominant butyrate-producing pathway [

40]. Overall, an increment in these genera implies that

N. gaditana might act as a prebiotic, creating an intestinal environment that promotes SCFA production, which has beneficial effects on gut health and potentially on systemic metabolism.

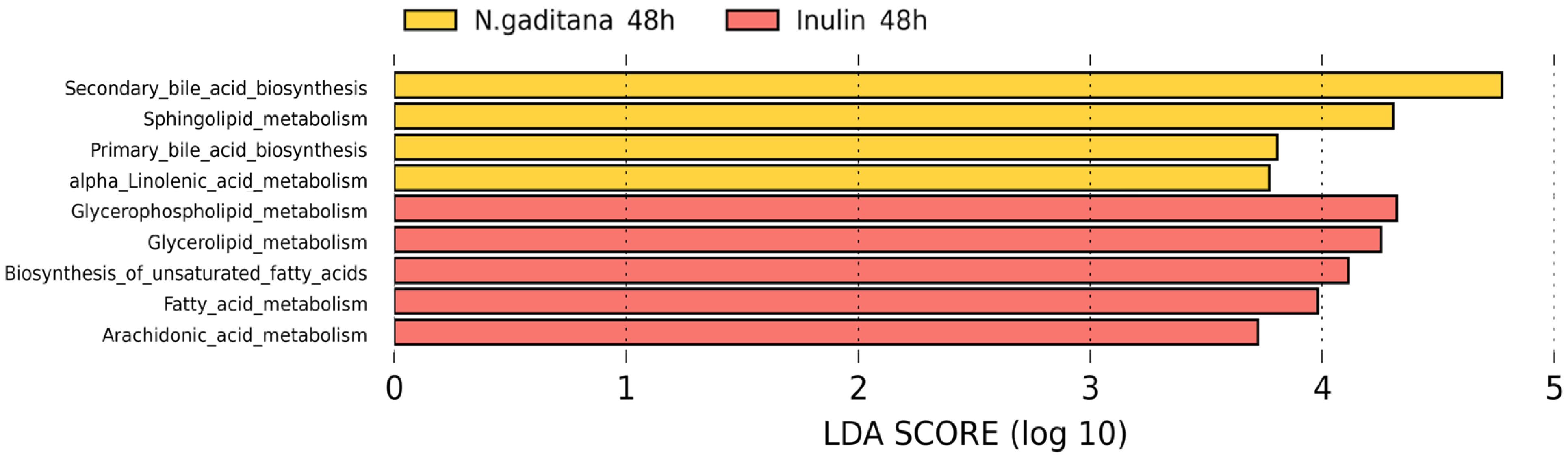

3.2. Microbial Functionality Analysis

In order to study the putative functional profiles of the microbial communities, a LEfSe analysis was performed to compare the KEGG metabolic pathways between

N. gaditana and inulin after 48 h of colonic fermentation (

Figure 6).

N. gaditana samples were more enriched in metabolic pathways related to bile acid metabolism (primary and secondary synthesis), sphingolipid metabolism and α-linolenic acid metabolism, which could be related to the abundance in

Bilophila and

Akkermansia since these bacteria are known to interact with bile acids, suggesting differential regulation of these metabolic pathways [

41,

42]. In contrast, the inulin samples were more active in pathways related to glycerophospholipid metabolism [

43], unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis and fatty acid elongation, among others. These samples showed a higher abundance of bacteria such as

Butyricicoccus,

Clostridium_sensu_stricto, and

Roseburia, which are associated with fatty acid metabolism.

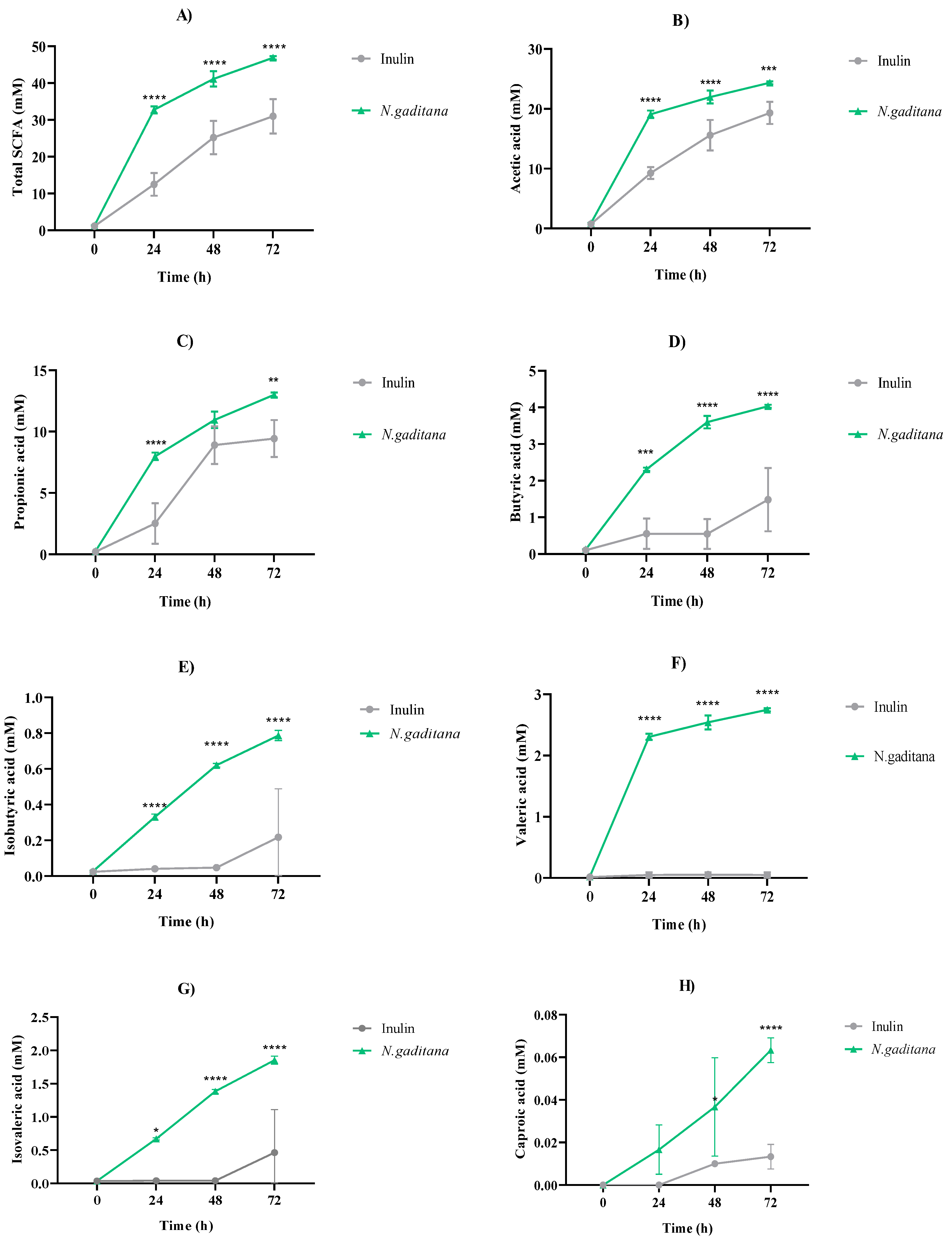

3.2.1. SCFA Profile

The concentration of the total, major and minor SCFAs production after

N. gaditana and inulin NAFs fermentation over time are shown in

Figure 7A-H.

N. gaditana digest was able to significantly increase the total SCFAs concentration up to 46.84 mM at 72 h, surpassing inulin SCFAs production (30.98 mM,

Figure 7A). It would be related to the increase in SCFA-producing bacteria from the NAF of

N. gaditana, such as

Akkermansia,

Butyricicoccus,

Eisenbergiella,

Lachnoclostridium, and

Marvinbryantia (

Figure 5). The concentrations of the major SCFAs, acetic acid (

Figure 7B) and propionic acid (

Figure 7C), over time were also higher when colonic medium was treated with NAF from

N. gaditana digest than with inulin-NAF, reaching final concentrations of 24.36 and 13 mM, respectively. Similar results were obtained for butyric acid, which concentration at the end of the fermentation with the microalga was 2.7-fold higher than that determined when inulin-NAF was added to the medium (

Figure 7D).

Several biological functions have been attributed to these major SCFAs, acting as key signaling molecules in human metabolic health [

44]. Acetate and propionate have important roles in human metabolism being utilized in lipid synthesis, acetylation reactions, and source of energy [

45]. Most obesity animal models and human trials have suggested a beneficial effect of both SCFAs, favoring weight loss and improving insulin sensitivity [

46,

47,

48]. On the other hand, butyric acid stands out as a key metabolite of the colonic microbiome. Recent studies have explored its chemistry, cellular signaling mechanisms, and clinical benefits, particularly for the colonic mucosa, where it serves as the main fuel source for mature colonocytes [

49]. Beyond the colon, butyric acid also functions as a local and systemic microbial metabolite with significant anti-inflammatory activity, making it a widely recognized biomarker of intestinal health [

50].

Our findings correlate well with previous results from other microalgae species and suggest the potential of the green microalgae

N. gaditana, as an important inducer of gut SCFAs production. Jin et al. [

19] demonstrated prebiotic effects of the digests of different microalgae on microbial species involved in propionic acid metabolism, which resulted in an increase of this SCFA. Moreover, de Medeiros et al. [

10,

11] determined the major SCFAs produced by different microalgae species like

A. platensis, C. vulgaris, and

D. maximus. Regarding acetic acid, its production was increased when the medium was treated with

C. vulgaris or

A. platensis biomass, while butyric acid was highly increased in the fermentation of

D. maximus biomass after 48 h. A more recent study focused on

A. platensis and

P. tricornutum extracts subjected to

in vitro digestion and fermentation, showed beneficial effects because of the increased production of acetic, propionic, and butyric acids [

51].

N. gaditana-NAF also exerted a stimulatory effect over the production of minor SCFAs, when compared to inulin-NAF (

Figures 7E-7H). A potent stimulating effect was observed for valeric acid production up to 2.74 mM at 72 h-fermentation, in contrast to the level reached by inulin-NAF (0.05 mM) (

Figure 7F). Recently, valeric acid has been identified as one of the most potent histone deacetylase inhibitors, demonstrating anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities in different

in vitro and

in vivo studies [

52]. Dietary fiber oat β-glucans, soybean isoflavones and other plant derived polysaccharides have been mainly reported to induce the generation of valeric acid by gut microbiota [

53,

54].

N. gaditana is considered one of the microalgae with the thickest cell walls with polysaccharides mainly composed of glucose (68%) along with rhamnose, mannose, ribose, xylose, fucose, and galactose (4-8%) [

55]. Hence, our findings suggested that during simulated gastrointestinal digestion, this polysaccharide rich cell wall could be partially degraded, being susceptible to the action of gut microbiota and the consequent release of major and minor SCFAs during the fermentation process.

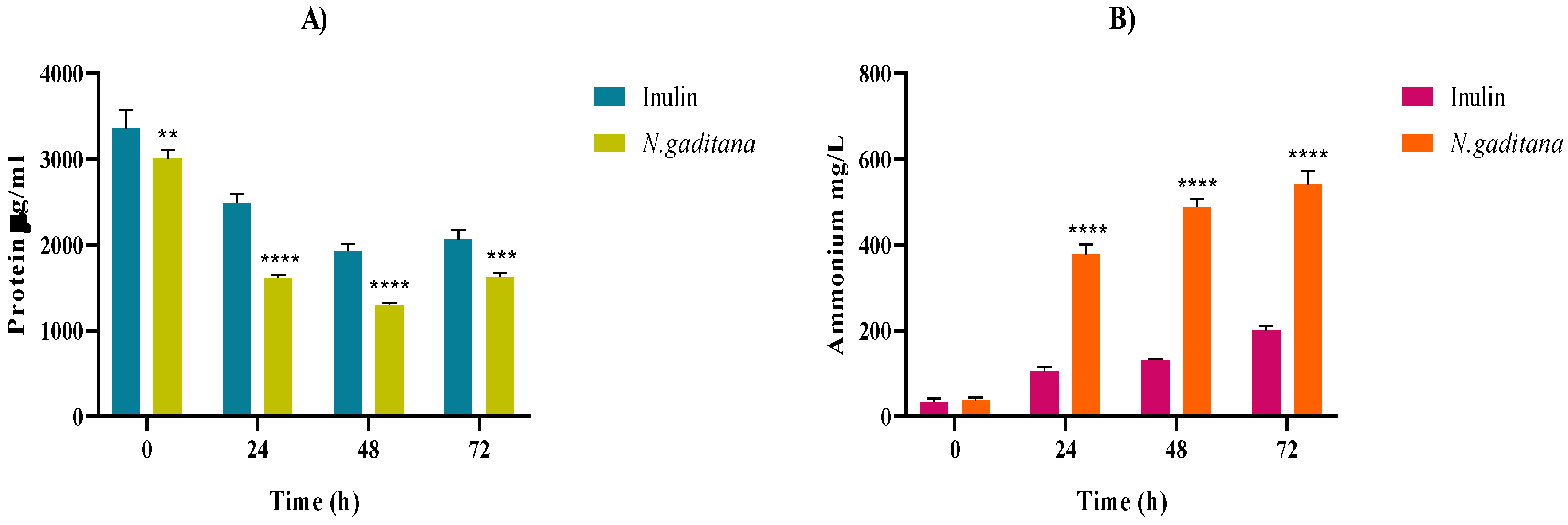

3.2.2. Protein Degradation and Ammonium Production

The protein and ammonium levels throughout the colonic fermentation of the NAF of

N. gaditana and inulin are shown on

Figure 8.

N. gaditana protein content decreased during the first 48 h of fermentation (

Figure 8A) and inversely, the ammonium content increased over time in both samples, being significantly higher in the case of

N. gaditana (540.91 mg/mL) than that of inulin (200.15 mg/mL) at the end of the fermentation (

Figure 8B). Proteins contained in the microalgal biomass together with peptides and amino acids released during the gastrointestinal digestion could be a nitrogen source for the growth of gut microbiota, releasing ammonium as a protein metabolism indicator [

56]. Ammonium is known to play a significant role in human health by influencing the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota. The study by Regueiro et al. [

57] examined the microbiome's response to controlled shifts in ammonium and long-chain fatty acids in anaerobic co-digestion systems. They found that high ammonium levels were correlated with shifts in microbial community composition, increasing the abundance of certain bacteria linked to SCFA production, while also leading to volatile fatty acid accumulation. This highlights the complex relationship between ammonium levels and SCFA production, suggesting that the higher SCFA stimulation observed with

N. gaditana, compared to the inulin control, may also be linked to the increase in ammonium levels.

4. Conclusions

Our findings support the modulatory role of N. gaditana on human gut microbiota composition and derived metabolites after its simulated gastrointestinal digestion. After 48 h of colonic fermentation, NAFs from N. gaditana significantly changed gut microbiota bacterial composition favoring the rise of health-related bacteria genera such as Akkermansia, Butyricicoccus, Eisenbergiella, Lachnoclostridium, and Marvinbryantia in contrast with inulin. Moreover, compared to this prebiotic, N. gaditana’s simulated gastrointestinal digests increased the production of major and minor SCFAs, especially the key bioactive SCFAs butyric acid and valeric acid, as well as the ammonium production after complete protein digestion. Consequently, this works highlights for the first time the potential of N. gaditana microalgae as new sustainable modulator agent of human gut microbiota composition and functionality that could become a practical food ingredient to enhance health by improving the intestinal microbial environment. Additional studies should be carried out to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the compounds responsible for the observed effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G.-C., and B.H.-L.; methodology, S.P., and M.M.; formal analysis, S.P., M.M., D.G.-N., A.O.-H., and S.S.-G.; investigation, S.P., M.M., A.O.-H.; S.S.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., M.M.; writing—review and editing, D.G.-N., M.A.F., P.G.-C., and B.H.-L.; supervision, D.G.-N., P.G.-C., B.H.-L., funding acquisition, P.G.-C., and B.H.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (grant number PID2021-122989OB-I00). S. Paterson gratefully acknowledges the Autonomous Community of Madrid for his predoctoral contract PIPF-2022/BIO-24996.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank C.C., and R. D.-S. for the technical support during the colonic fermentation process, and the Analytical, Instrumental and Microbiological Techniques Service Unit (ICTAN, CSIC) for carrying out the SCFA analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Merlo, G.; Bachtel, G.; Sugden, S.G. Gut Microbiota, Nutrition, and Mental Health. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- McCallum, G.; Tropini, C. The Gut Microbiota and Its Biogeography. Nat Rev Microbiol 2024, 22, 105–118. [CrossRef]

- Dasriya, V.L.; Samtiya, M.; Ranveer, S.; Dhillon, H.S.; Devi, N.; Sharma, V.; Nikam, P.; Puniya, M.; Chaudhary, P.; Chaudhary, V.; et al. Modulation of Gut-Microbiota through Probiotics and Dietary Interventions to Improve Host Health. J Sci Food Agric 2024, 104, 6359-6375. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, N.; Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolites Maintain Gut and Systemic Immune Homeostasis. Cells 2023, 12, 793. [CrossRef]

- Hamjane, N.; Mechita, M.B.; Nourouti, N.G.; Barakat, A. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis -Associated Obesity and Its Involvement in Cardiovascular Diseases and Type 2 Diabetes. A Systematic Review. Microvasc Res 2024, 151, 104601. [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R.; Fresán, U.; Marsh, K.; Miles, F.L.; Saunders, A. V.; Haddad, E.H.; Heskey, C.E.; Johnston, P.; Larson-meyer, E.; et al. The Safe and Effective Use of Plant-based Diets with Guidelines for Health Professionals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4144. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Why Alternative Proteins Will Not Disrupt the Meat Industry. Meat Sci 2023, 203, 109223. [CrossRef]

- Thavamani, A.; Sferra, T.J.; Sankararaman, S. Meet the Meat Alternatives: The Value of Alternative Protein Sources. Curr Nutr Rep 2020, 9, 346-355. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Bioactivity and Digestibility of Microalgae Tetraselmis sp. and Nannochloropsis sp. as Basis of Their Potential as Novel Functional Foods. Nutrients 2023, 15, 477. [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, V.P.B.; de Souza, E.L.; de Albuquerque, T.M.R.; da Costa Sassi, C.F.; dos Santos Lima, M.; Sivieri, K.; Pimentel, T.C.; Magnani, M. Freshwater Microalgae Biomasses Exert a Prebiotic Effect on Human Colonic Microbiota. Algal Res 2021, 60, 102547. [CrossRef]

- Barros de Medeiros, V.P.; Salgaço, M.K.; Pimentel, T.C.; Rodrigues da Silva, T.C.; Sartoratto, A.; Lima, M. dos S.; Sassi, C.F. da C.; Mesa, V.; Magnani, M.; Sivieri, K. Spirulina platensis Biomass Enhances the Proliferation Rate of Lactobacillus Acidophilus 5 (La-5) and Combined with La-5 Impact the Gut Microbiota of Medium-Age Healthy Individuals through an in Vitro Gut Microbiome Model. Food Res Int 2022, 154, 110880. [CrossRef]

- Stiefvatter, L.; Neumann, U.; Rings, A.; Frick, K.; Schmid-Staiger, U.; Bischoff, S.C. The Microalgae Phaeodactylum tricornutum Is Well Suited as a Food with Positive Effects on the Intestinal Microbiota and the Generation of SCFA: Results from a Pre-Clinical Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2504–2504. [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, A.R.J.; Guilherme-Fernandes, J.; Spínola, M.; Maia, M.R.G.; Yergaliyev, T.; Camarinha-Silva, A.; Fonseca, A.J.M. Effects of Microalgae as Dietary Supplement on Palatability, Digestibility, Fecal Metabolites, and Microbiota in Healthy Dogs. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Abdelhafiz, Y.; Abreu, H.; Silva, J.; Valente, L.M.P.; Kiron, V. Gracilaria gracilis and Nannochloropsis oceanica, Singly or in Combination, in Diets Alter the Intestinal Microbiota of European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Front Mar Sci 2022, 9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cerezo-Ortega, I.M.; Di Zeo-Sánchez, D.E.; García-Márquez, J.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; Sáez-Casado, M.I.; Balebona, M.C.; Moriñigo, M.A.; Tapia-Paniagua, S.T. Microbiota Composition and Intestinal Integrity Remain Unaltered after the Inclusion of Hydrolysed Nannochloropsis gaditana in Sparus aurata Diet. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 18779. [CrossRef]

- Jorge, S.S.; Enes, P.; Serra, C.R.; Castro, C.; Iglesias, P.; Oliva Teles, A.; Couto, A. Short-term Supplementation of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata) Diets with Nannochloropsis gaditana Modulates Intestinal Microbiota without Affecting Intestinal Morphology and Function. Aquac Nutr 2019, 25, 1388–1398. [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static in Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 991–1014. [CrossRef]

- Hiel, S.; Bindels, L.B.; Pachikian, B.D.; Kalala, G.; Broers, V.; Zamariola, G.; Chang, B.P.I.; Kambashi, B.; Rodriguez, J.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Effects of a Diet Based on Inulin-Rich Vegetables on Gut Health and Nutritional Behavior in Healthy Humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2019, 109, 1683–1695. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.B.; Cha, J.W.; Shin, I.S.; Jeon, J.Y.; Cha, K.H.; Pan, C.H. Supplementation with Chlorella vulgaris, Chlorella protothecoides, and Schizochytrium sp. Increases Propionate-Producing Bacteria in in Vitro Human Gut Fermentation. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 2938–2945. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Sánchez, I.; Cueva, C.; Sanz-Buenhombre, M.; Guadarrama, A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Bartolomé, B. Dynamic Gastrointestinal Digestion of Grape Pomace Extracts: Bioaccessible Phenolic Metabolites and Impact on Human Gut Microbiota. J Food Comp Anal 2018, 68, 41–52. [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, A.; de Llano, D.G.; Cueva, C.; del Hierro, J.N.; Martin, D.; Molinero, N.; Bartolomé, B.; Victoria Moreno-Arribas, M. Deciphering the Interactions between Lipids and Red Wine Polyphenols through the Gastrointestinal Tract. Food Res Int 2023, 165, 112524. [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 852–857. [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic Biomarker Discovery and Explanation. Genome Biol 2011, 12, R60. [CrossRef]

- García-Villalba, R.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Carlos Espín, J.; Larrosa, M. Alternative Method for Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Faecal Samples. J Sep Sci 2012, 35, 1906–1913. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Galvez, A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Evaluation of the Multifunctionality of Soybean Proteins and Peptides in Immune Cell Models. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1220. [CrossRef]

- Jinkerson, R.E.; Radakovits, R.; Posewitz, M.C. Genomic Insights from the Oleaginous Model Alga Nannochloropsis gaditana. Bioengineered 2013, 4, 37-43. [CrossRef]

- Verspreet, J.; Kreps, S.; Bastiaens, L. Evaluation of Microbial Load, Formation of Odorous Metabolites and Lipid Stability during Wet Preservation of Nannochloropsis gaditana Concentrates. Appl Sci (Switzerland) 2020, 10, 3419. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Majchrzak, M.; Alexandru, D.; Di Bella, S.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Arranz, E.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Impact of the Biomass Pretreatment and Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion on the Digestibility and Antioxidant Activity of Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris and Tetraselmis chuii. Food Chem 2024, 453, 139686. [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Pang, D.; Wen, L.; You, L.; Huang, R.; Kulikouskaya, V. In Vitro Digestibility and Prebiotic Activities of a Sulfated Polysaccharide from Gracilaria lemaneiformis. J Funct Foods 2020, 64, 103652. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Duan, X.; Zhou, L.; Hill, D.R.A.; Martin, G.J.O.; Suleria, H.A.R. Bioaccessibility and Bioactivities of Phenolic Compounds from Microalgae during in Vitro Digestion and Colonic Fermentation. Food Funct 2023, 14, 899–910. [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.; Wang, J.; Chao, C.; Yu, J.; Copeland, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, S. RS5 Produced More Butyric Acid through Regulating the Microbial Community of Human Gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 3209–3218. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pan, L.; Wang, B.; Zou, X.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y. Simulated Digestion and Fecal Fermentation Behaviors of Levan and Its Impacts on the Gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 1531–1546. [CrossRef]

- Firrman, J.; Liu, L.S.; Mahalak, K.; Tanes, C.; Bittinger, K.; Tu, V.; Bobokalonov, J.; Mattei, L.; Zhang, H.; Van Den Abbeele, P. The Impact of Environmental PH on the Gut Microbiota Community Structure and Short Chain Fatty Acid Production. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2022, 98, fiac038. [CrossRef]

- Segers, A.; de Vos, W.M. Mode of Action of Akkermansia muciniphila in the Intestinal Dialogue: Role of Extracellular Proteins, Metabolites and Cell Envelope Components. Microbiome Res Rep 2023, 2, 6. [CrossRef]

- Eeckhaut, V.; Ducatelle, R.; Sas, B.; Vermeire, S.; Van Immerseel, F. Progress towards Butyrate-Producing Pharmabiotics: Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum Capsule and Efficacy in TNBS Models in Comparison with Therapeutics. Gut 2014, 63, 367. [CrossRef]

- Devriese, S.; Eeckhaut, V.; Geirnaert, A.; Van den Bossche, L.; Hindryckx, P.; Van de Wiele, T.; Van Immerseel, F.; Ducatelle, R.; De Vos, M.; Laukens, D. Reduced Mucosa-Associated Butyricicoccus Activity in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Correlates with Aberrant Claudin-1 Expression. J Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 229–236. [CrossRef]

- Biddle, A.; Stewart, L.; Blanchard, J.; Leschine, S. Untangling the Genetic Basis of Fibrolytic Specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in Diverse Gut Communities. Diversity 2013, 5, 627–640. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, P.O.; Martin, J.C.; Lawley, T.D.; Browne, H.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Duncan, S.H.; O’Toole, P.W.; Scott, K.P.; Flint, H.J. Polysaccharide Utilization Loci and Nutritional Specialization in a Dominant Group of Butyrate-Producing Human Colonic Firmicutes. Microb Genom 2016, 2, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Rey, F.E.; Faith, J.J.; Bain, J.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Stevens, R.D.; Newgard, C.B.; Gordon, J.I. Dissecting the in Vivo Metabolic Potential of Two Human Gut Acetogens. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 22082–22090. [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Long, W.; Hao, B.; Ding, D.; Ma, X.; Zhao, L.; Pang, X. A Human Stool-Derived Bilophila wadsworthia Strain Caused Systemic Inflammation in Specific-Pathogen-Free Mice. Gut Pathog 2017, 9, 59. [CrossRef]

- Perino, A.; Demagny, H.; Schoonjans, K. A Microbial-Derived Succinylated Bile Acid to Safeguard Liver Health. Cell 2024, 187, 2687–2689. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Huang, F.; Zhao, A.; Lei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, G.; Chen, T.; Qu, C.; Rajani, C.; Dong, B.; et al. Bile Acid Is a Significant Host Factor Shaping the Gut Microbiome of Diet-Induced Obese Mice. BMC Biol 2017, 15, 120. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Trone, K.; Kelly, C.; Stroud, A.; Martindale, R. All Fiber Is Not Fiber. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2023, 25, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jang, C.; Liu, J.; Uehara, K.; Gilbert, M.; Izzo, L.; Zeng, X.; Trefely, S.; Fernandez, S.; Carrer, A.; et al. Dietary Fructose Feeds Hepatic Lipogenesis via Microbiota-Derived Acetate. Nature 2020, 579, 586–591. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.F.; Falk Petersen, K.; Impellizeri, A.; Cline, G.W.; Shulman, G.I. The Effects of Increased Acetate Turnover on Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion in Lean and Obese Humans. J Clin Transl Sci 2019, 3, 18–20. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.S.; Viardot, A.; Psichas, A.; Morrison, D.J.; Murphy, K.G.; Zac-Varghese, S.E.K.; MacDougall, K.; Preston, T.; Tedford, C.; Finlayson, G.S.; et al. Effects of Targeted Delivery of Propionate to the Human Colon on Appetite Regulation, Body Weight Maintenance and Adiposity in Overweight Adults. Gut 2015, 64, 1744–1754. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D.P.; Shah, P.; Van Den Abbeele, P.; Marzorati, M.; Calatayud, M.; Ghyselinck, J.; Dubey, A.K.; Narayanan, S.; Jain, M. Microbial Fermentation of FossenceTM, a Short-Chain Fructo-Oligosaccharide, under Simulated Human Proximal Colonic Condition and Assessment of Its Prebiotic Effects-a Pilot Study. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2021, 368, fnab147. [CrossRef]

- Gerunova, L.K.; Gerunov, T. V.; P’yanova, L.G.; Lavrenov, A. V.; Sedanova, A. V.; Delyagina, M.S.; Fedorov, Y.N.; Kornienko, N. V.; Kryuchek, Y.O.; Tarasenko, A.A. Butyric Acid and Prospects for Creation of New Medicines Based on Its Derivatives: A Literature Review. J Vet Sci 2024, 25, e23. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Lee, G.D.; Son, H.W.; Koh, H.; Kim, E.S.; Unno, T.; Shin, J.H. Butyrate Producers, “The Sentinel of Gut”: Their Intestinal Significance with and beyond Butyrate, and Prospective Use as Microbial Therapeutics. Front Microbiol 2023, 13, 1103836. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Bäuerl, C.; Cortés-Macías, E.; Calvo-Lerma, J.; Collado, M.C.; Barba, F.J. The Impact of Liquid-Pressurized Extracts of Spirulina, Chlorella and Phaedactylum tricornutum on in Vitro Antioxidant, Antiinflammatory and Bacterial Growth Effects and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Food Chem 2023, 401, 134083. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, B.; Kumari, U.; Singh, D.K.; Husain, G.M.; Patel, D.K.; Shakya, A.; Singh, R.B.; Modi, G.P.; Singh, G.K. Molecular Targets of Valeric Acid: A Bioactive Natural Product for Endocrine, Metabolic, and Immunological Disorders. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2024, 24, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Luo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guan, J.; Zhou, T.; Du, Z.; Yong, K.; Yao, X.; Shen, L.; et al. Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites with Dietary Fiber Oat β-Glucan Interventions to Improve Growth Performance and Intestinal Function in Weaned Rabbits. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zheng, T.; Hui, H.; Xie, G. Soybean Isoflavones Modulate Gut Microbiota to Benefit the Health Weight and Metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.J.; Weiss, T.L.; Jinkerson, R.E.; Jing, J.; Roth, R.; Goodenough, U.; Posewitz, M.C.; Gerken, H.G. Ultrastructure and Composition of the Nannochloropsis gaditana Cell Wall. Eukaryot Cell 2014, 13, 1450–1464. [CrossRef]

- Amaretti, A.; Gozzoli, C.; Simone, M.; Raimondi, S.; Righini, L.; Pérez-Brocal, V.; García-López, R.; Moya, A.; Rossi, M. Profiling of Protein Degraders in Cultures of Human Gut Microbiota. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 2614. [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, L.; Carballa, M.; Lema, J.M. Microbiome Response to Controlled Shifts in Ammonium and LCFA Levels in Co-Digestion Systems. J Biotechnol 2016, 220, 35–44. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Impact of the non-absorbable fractions (NAF) of Nannochloropsis gaditana and inulin on gut microbiota microbial counts (log Colonies Forming Units (CFU)/mL) after 0, 24, 48 and 72 h of colonic fermentation. (A) Total Aerobes, (B) Total Anaerobes, (C) Enterobacteriaceae (D) Staphylococcus sp. *differences in values were considered significant when they were higher or lower than 1 log (CFU/mL) compared to the inulin (control).

Figure 2.

Gut microbiota diversity of NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin at zero time and after 48 h. α diversity is presented by observed OTUs (A), Chao1 (B), Simpson richness index (C), and Shannon diversity index (D). The results are shown in boxplots.

Figure 2.

Gut microbiota diversity of NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin at zero time and after 48 h. α diversity is presented by observed OTUs (A), Chao1 (B), Simpson richness index (C), and Shannon diversity index (D). The results are shown in boxplots.

Figure 3.

β diversity presented by PCoA plot of Jaccard dissimilarity index of NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin at zero time and after 48 h. PCo1 and PCo2 values for each sample are plotted with the percentage of explained variance shown in parentheses.

Figure 3.

β diversity presented by PCoA plot of Jaccard dissimilarity index of NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin at zero time and after 48 h. PCo1 and PCo2 values for each sample are plotted with the percentage of explained variance shown in parentheses.

Figure 4.

Gut microbiota composition at phylum level of NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin at zero time and after 48 h.

Figure 4.

Gut microbiota composition at phylum level of NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin at zero time and after 48 h.

Figure 5.

Changes in the abundance of bacteria genera differentially expressed on NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin after 48 h. Data are expressed as log fold changes with respect to zero time. *** P < 0.0001 vs zero time.

Figure 5.

Changes in the abundance of bacteria genera differentially expressed on NAFs from N. gaditana and inulin after 48 h. Data are expressed as log fold changes with respect to zero time. *** P < 0.0001 vs zero time.

Figure 6.

LEfSe analysis showing discriminative KEGG metabolic pathways between N.gaditana and inulin after 48 h of colonic fermentation. All KEGG pathways showed a statistically significant change (P < 0.05), with an LDA score threshold set to 2.5.

Figure 6.

LEfSe analysis showing discriminative KEGG metabolic pathways between N.gaditana and inulin after 48 h of colonic fermentation. All KEGG pathways showed a statistically significant change (P < 0.05), with an LDA score threshold set to 2.5.

Figure 7.

Major and minor short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) production after the colonic fermentation of the non-absorbable fractions (NAF) from Nannochloropsis gaditana and inulin (control) at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. (A) Total SCFAs, (B) Acetic acid, (C) Propionic acid, (D) Butyric acid, (E) Isobutyric acid, (F) Valeric acid, (G) Isovaleric acid, (H) Caproic acid. Level of significance each time compared to the inulin (control): * 0.01 < P-value < 0.05; ** 0.001 < P-value < 0.01; *** 0.0001 < P -value < 0.001; **** P-value < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

Major and minor short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) production after the colonic fermentation of the non-absorbable fractions (NAF) from Nannochloropsis gaditana and inulin (control) at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. (A) Total SCFAs, (B) Acetic acid, (C) Propionic acid, (D) Butyric acid, (E) Isobutyric acid, (F) Valeric acid, (G) Isovaleric acid, (H) Caproic acid. Level of significance each time compared to the inulin (control): * 0.01 < P-value < 0.05; ** 0.001 < P-value < 0.01; *** 0.0001 < P -value < 0.001; **** P-value < 0.0001.

Figure 8.

Protein and ammonium levels throughout the colonic fermentation of the non-absorbable fractions (NAF) of Nannochloropsis gaditana and inulin (control) at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. (A) Protein content (µg/mL) (B) Ammonium content (mg/mL). Level of significance each time compared to the inulin (control): * 0.01 < P-value < 0.05; ** 0.001 < P-value < 0.01; *** 0.0001 < P-value < 0.001; **** P-value < 0.0001.

Figure 8.

Protein and ammonium levels throughout the colonic fermentation of the non-absorbable fractions (NAF) of Nannochloropsis gaditana and inulin (control) at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. (A) Protein content (µg/mL) (B) Ammonium content (mg/mL). Level of significance each time compared to the inulin (control): * 0.01 < P-value < 0.05; ** 0.001 < P-value < 0.01; *** 0.0001 < P-value < 0.001; **** P-value < 0.0001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).