E. Ring Potential

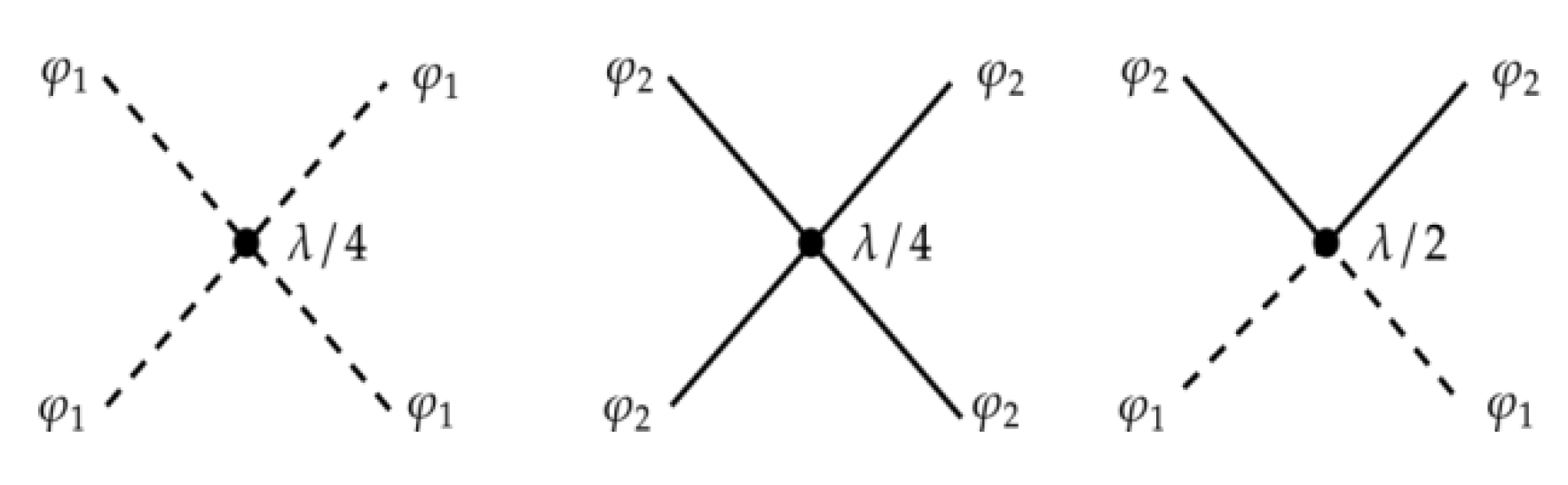

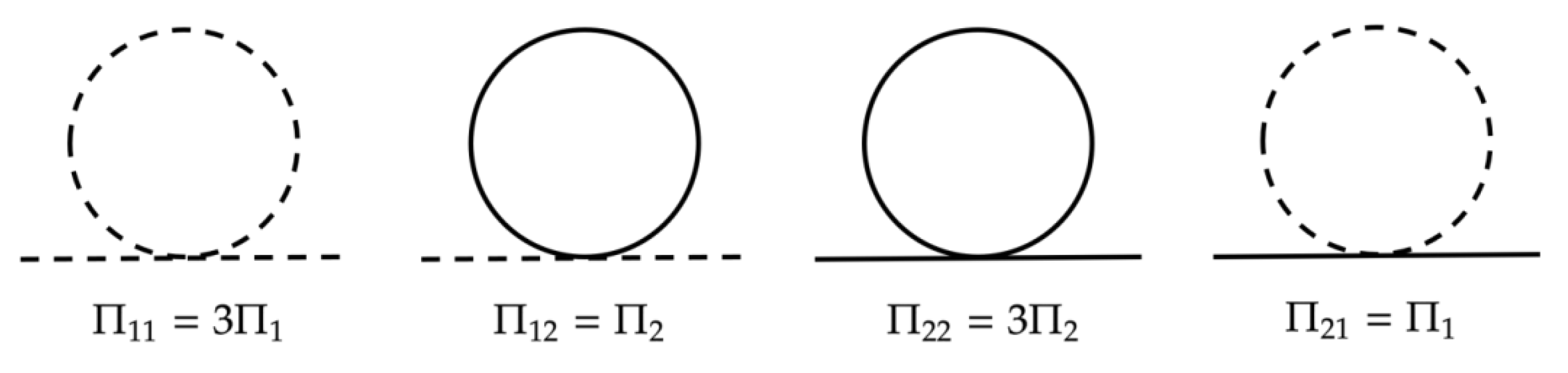

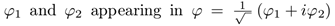

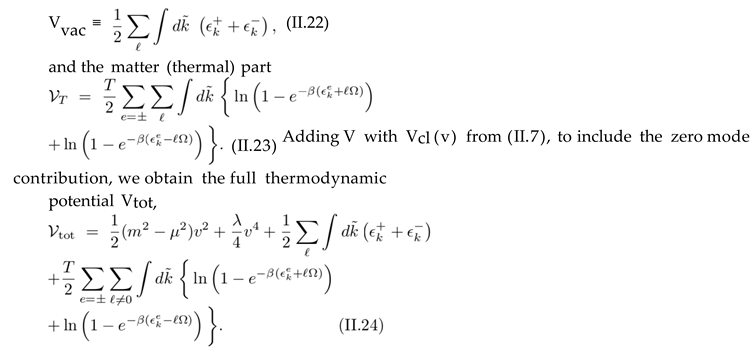

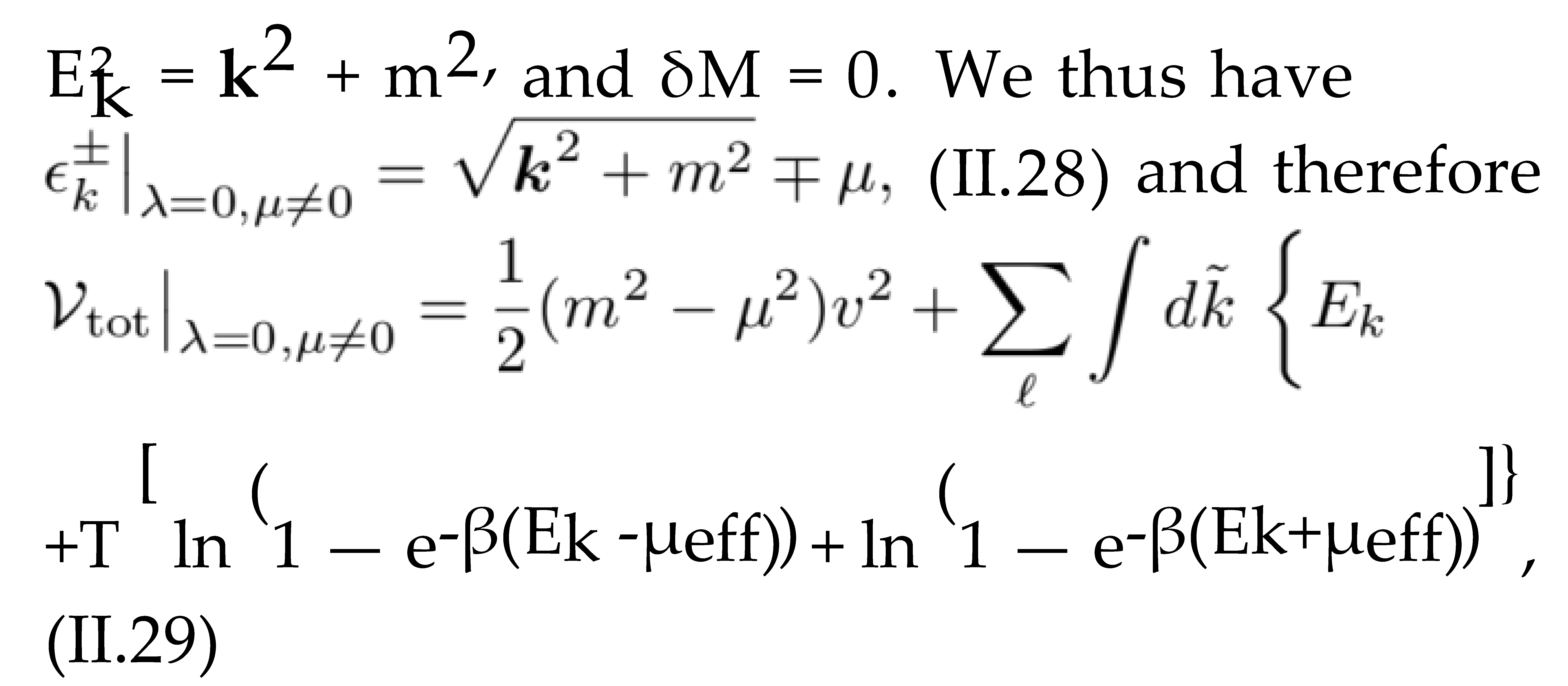

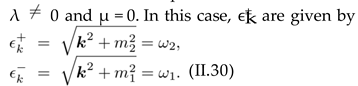

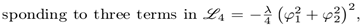

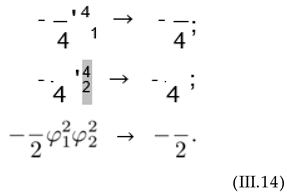

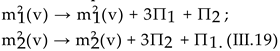

We finally consider the nonperturbative ring poten- tial Vring. As mentioned in the previous paragraphs, the Lagrangian is written in terms of φ 1 and φ2, three type of vertices appear in the λ(φ⋆ φ) model (see

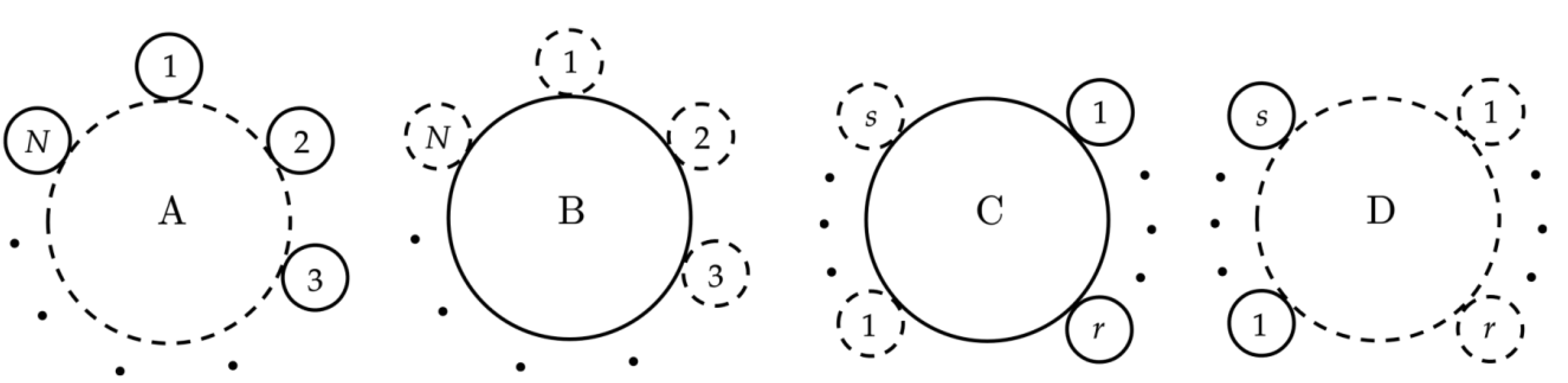

Figure 3). We thus have four different types of ring diagrams:

- Type A: A ring with N insertions of Π2 and N propagators

Dℓ (ωn,ω 1) propagators, ,

- Type B: A ring with N insertions of Π 1 and N propagators

Dℓ (ωn,ω2) propagators, ,

- Type C: A ring with r insertions of Π2 and s insertions of Π 1 with N propagators Dℓ (ωn,ω2), .

Here, r ≥ 1 and r + s = N.

- Type D: A ring with r insertions of Π 1 and s insertions of Π2 with N propagators Dℓ (ωn,ω 1), .

Similar to the previous case, r ≥ 1 and r + s = N.

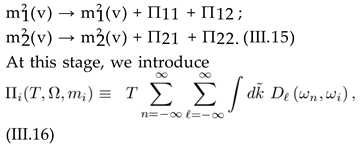

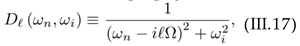

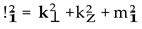

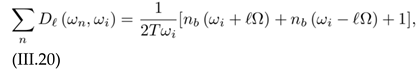

Here, Πi (T,Ω, mi) and Dℓ (ωn,ωi), i = 1, 2 are defined in (III.16) and (III.17), respectively. In

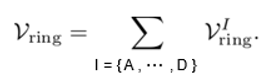

Figure 6, these different types of ring potentials are demonstrated. The full contribution of the ring potential is given by

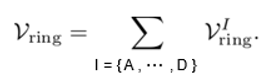

(III.43)

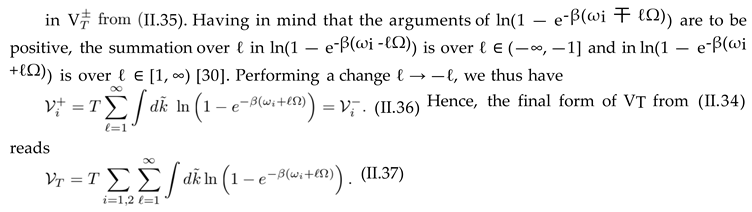

Following standard field theoretical method, it is possi- ble to determine the combinatorial factors leading to the standard form of the ring potential [

40]. In

Appendix D, we outline the derivation of

, I = A, ···, D. They

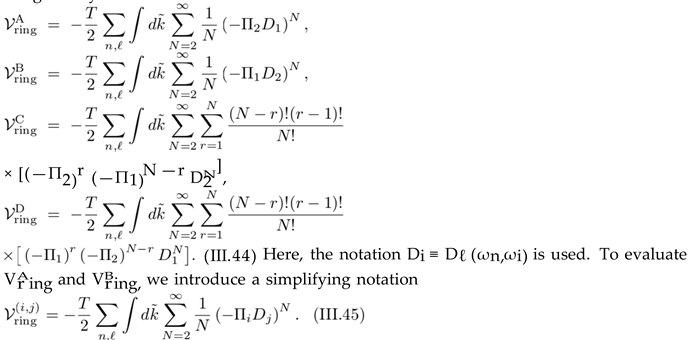

are given by

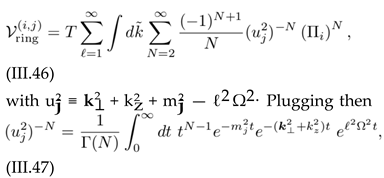

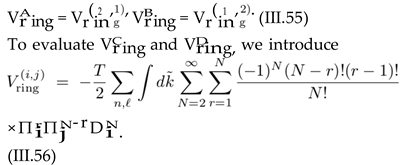

Here, (i, j) = (2, 1) and (i, j) = (1, 2) correspond to and , respectively. Plugging Dj from (III.17) into (III.45) and focusing on n = 0 as well as ℓ ≠ 0 contri- butions in the summation over n and ℓ, we arrive first at

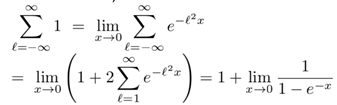

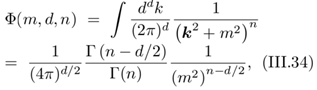

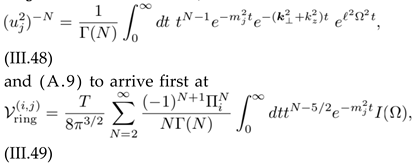

into (III.46), the integration over k⊥ and kz can be car- ried out by making used of (A.9). To limit the summation over ℓ from below, we use the fact that the summand is even in ℓ. To perform the integration over k⊥ and kz, we use the Mellin transformation of () —N,

where

(III.50) To evaluate the summation over ℓ, we expand in a Taylor expansion and obtain

(III.51) with function. Since for r ∈ N, we have ζ(—2r) = 0, the only nonvanishing contribution to the summation over r

(III.52)

Plugging this result into (III.49), using

(III.53)

and performing the summation over N, we arrive at (III.54)

We arrive eventually at

Here, (i, j) = (2, 1) corresponds to and (i, j) = (1, 2) to . Plugging Di from (III.17) into (III.56) and focusing on n = 0 and ℓ 0 contributions in the summa- tion over n and ℓ, we obtain

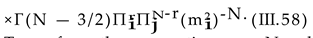

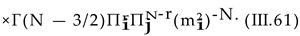

where is defined below (III.46). Following, at this stage, the same steps as described in previous paragraph, we arrive first at

To perform the summation over N and r, we use the relation

(III.59)

We thus obtain

, = V (i) + V (i,j), (III.60)

with

For V (i), the summation over N can be carried out and yields

(III.62)

As concerns V (i,j), we perform the summation over N and arrive at

(III.63)

where pFq (a;b;z) is the generalized hypergeometric function having the following series expansion

(III.64) Here, a = (a1, ···, ap), b = (b1, ···, bq) are vectors with p and q components. Moreover, (ai)k ≡ Γ(ai + k)/Γ(ai) is the Pochhammer symbol. For our purposes, it is suffi- cient to focus on the contribution at r = 1 in (III.63).

(III.65)

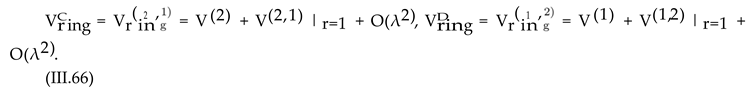

Having in mind that the one-loop contribution to the self- energy Πi, which is determined in Sec. III B is of order O(λ), the contributions corresponding to r ≥ 2 are of order O(λ2) and can be neglected at this stage. We thus have

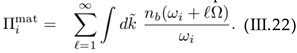

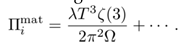

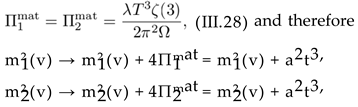

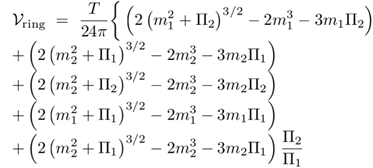

The final result for Vring is given by plugging , I = A, ···, D from (III.55) and (III.65) into (III.43),

Focusing only on the first perturbative correction to Πi and using , i = 1, 2 from (III.28), the above results is simplified as

(III.68)

F. Summary of Analytical Results in Sec. III

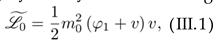

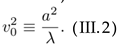

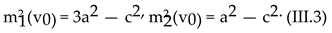

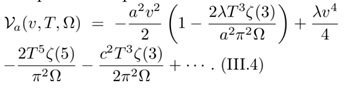

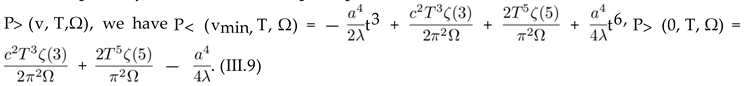

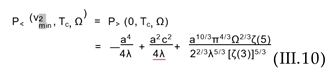

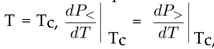

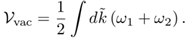

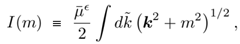

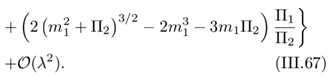

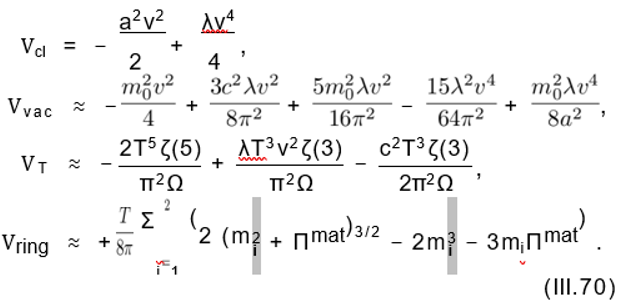

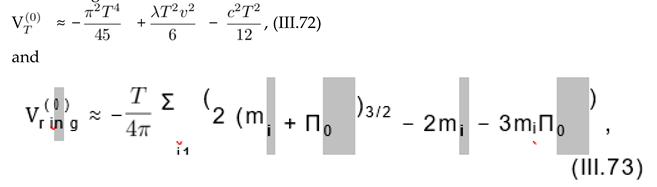

In this section, we summarize the main findings. According to these results, the total thermodynamic potential of a rigidly rotating Bose gas, Vtot, including the classical potential Vcl from (II.32) with c2 replaced with a2, the vacuum potential (II.33), the thermal part (II.34), and the ring potential (III.43) is given by

Vtot = Vcl + Vvac + VT + Vring, (III.69) with

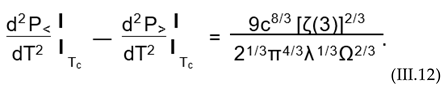

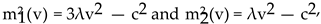

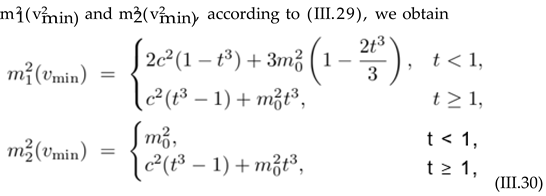

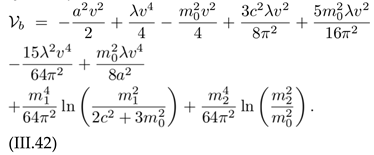

Here, a2 = c2 + m02, m12(v) = 3λv2 − c2 and m22(v) = λv2 − c2, and Πmat = λT3 ζ(3)/2π2 Ω. We notice that the logarithmic terms appearing in Vvac from (III.42) are skipped in (III.70).

In the next section, we study the effect of rotation on the formation of condensate and the critical temperature of the global U(1) phase transition. To this purpose, we compare our results with the results arising from the full thermodynamic potential of a nonrotating Bose gas. According to [40], it is given by (Subscripts (0) correspond to Ω = 0.)

= Vcl + Vvac + + , (III.71) where Vcl and Vvac are given in

(III.70), while and read

with the one-loop self-energy correction Π0mat = λT2 /3 [40] and mi2, i = 1, 2 given as above.

IV. Numerical Results

In this section, we explore the effect of rotation on different quantities related to the spontaneous breaking

of global U(1) symmetry. To this purpose, we consider different parts of Vtot from (III.69).

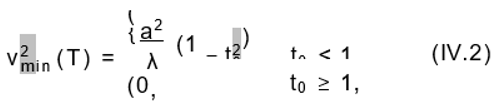

In Sec. III A, we derived the minimum of the potential

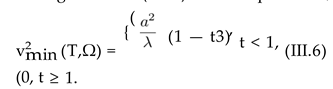

Va including Vcl and VT. We arrived at vmin2 (T,Ω) from

(III.6). Replacing VT with from (III.72) for a nonrotating Bose gas and following the same steps leading from (III.4) to (III.6), we arrive at the critical temperature

(IV.1)

and the T dependent minima

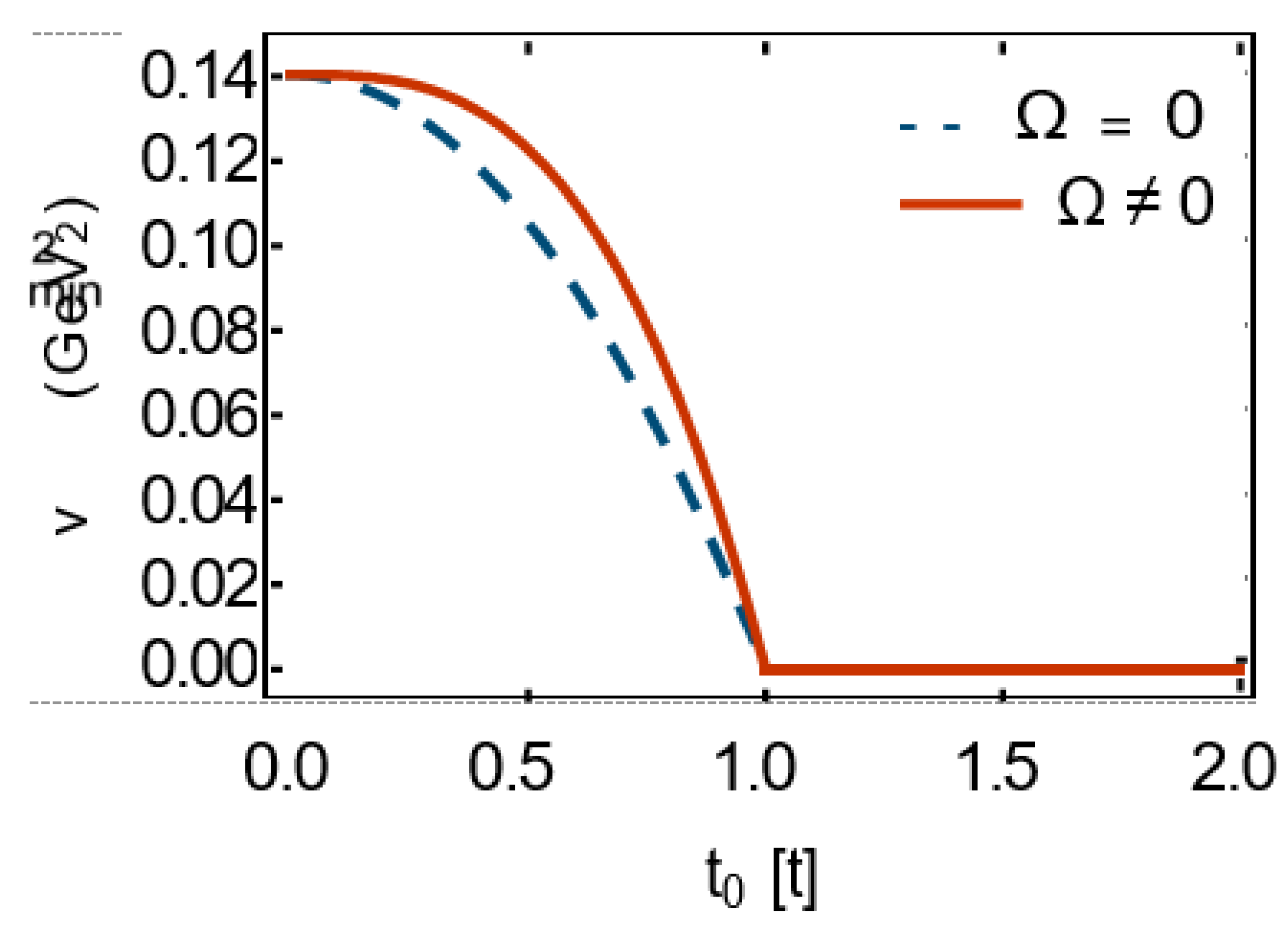

with the reduced temperature t0 = T/Tc

(0) and Tc

(0) from (IV.1). In

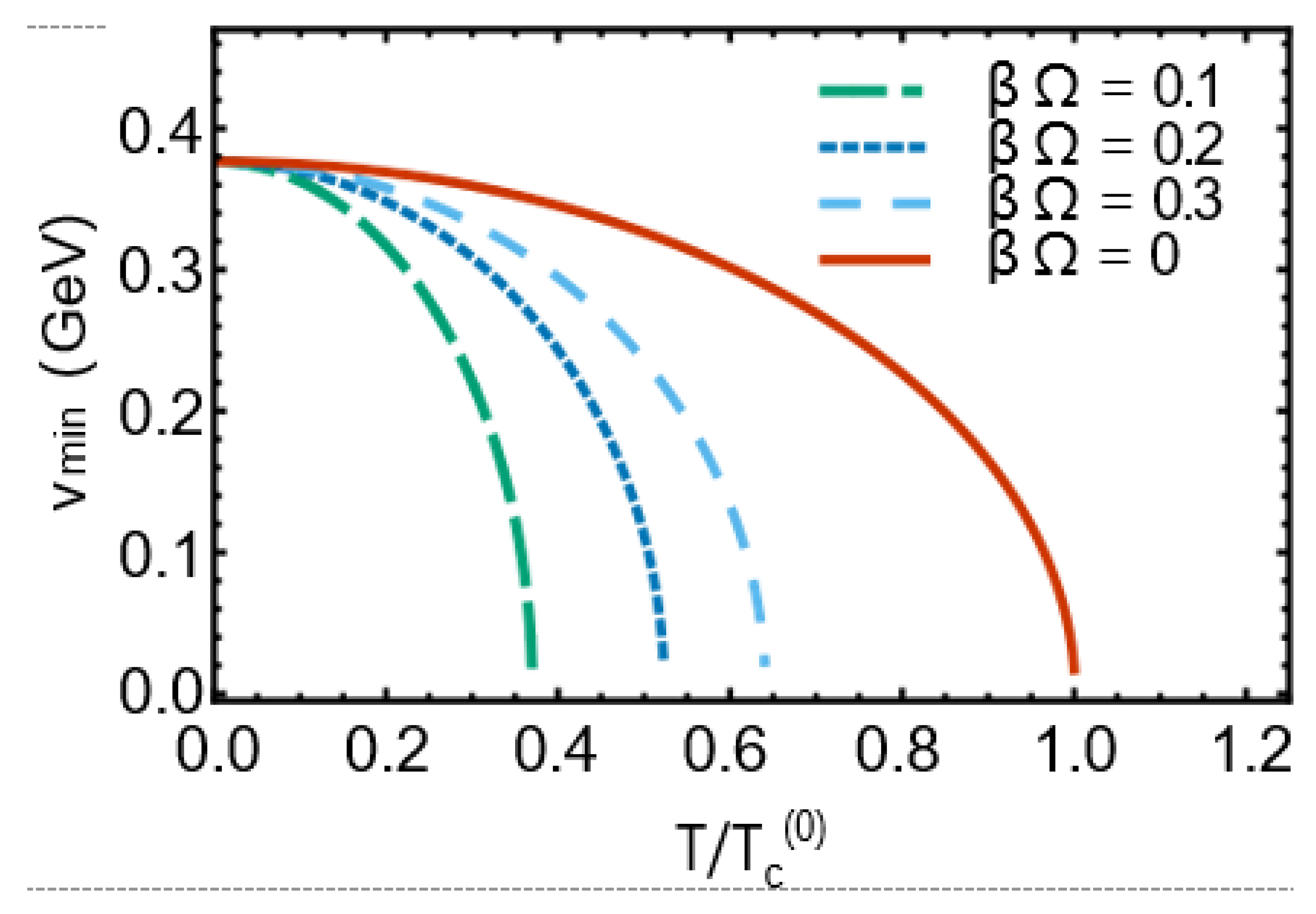

Figure 7, vmin

2 is plotted for Ω = 0 [see (IV.2)] and Ω

0 [see (III.6)] as function of the corresponding reduced temperature t0 and t. The difference between these two plots arises mainly from different exponents of the corresponding reduced temperatures t0 and t in (IV.2) and (III.6). The reason of this difference lies in dif- ferent results for the high-temperature expansion of

for Ω = 0 [see (III.72)] and VT for Ω

0 [see (III.70)].

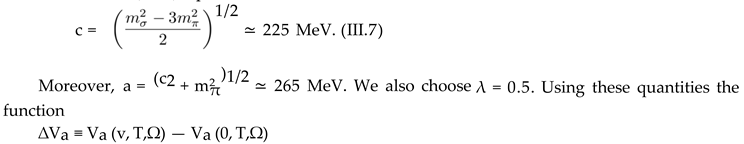

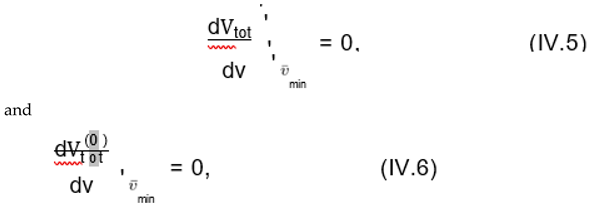

Let us consider Vtot − Vring = Vcl + Vvac + VT from (III.69). By minimizing this potential with respect to v, and solving the resulting gap equation,

it is possible to determine numerically the T dependence the minima, denoted by v-min (T,Ω), for fixed Ω. To this purpose, we use the quantities a ≃ 0.265 GeV, c ≃ 0.225 GeV, and λ = 0.5 given in (III.7). In

Figure 8, the T/Tc

(0) dependence of

min is demonstrated for βΩ = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3

(dashed, dotted, and dotted-dashed curves). The results are then compared with the corresponding minima for a nonrotating Bose gas (red solid curve). The latter is determined by minimizing the combination — , according to

with from (III.71). In both cases, Tc(0) ≃ 0.681 GeVis the critical temperature of the spontaneous U(1) sym- metry breaking in a nonrotating Bose gas. (The critical temperature is the temperature at which the condensate min vanishes.)

These results indicate that rotation lowers the critical temperature of the phase transition. However, as shown in

Figure 8, Tc increases with increasing Ω. It is also im- portant to note that this same trend is observed in a noninteracting Bose gas under rigid rotation [

30].

To answer the question whether the transition is con- tinuous or discontinuous, we have to explore the shape of the potential, the value of its first and second order derivatives at temperatures below and above the critical temperature, Tc. Using the numerical values for the set of free parameters a, c, and λ as mentioned above, the transitions turns out to be continuous not only for Ω = 0 but also for Ω 0.

To explore the effect of the ring potential on the tem- perature dependence of the condensate v-min, we solved numerically the gap equation

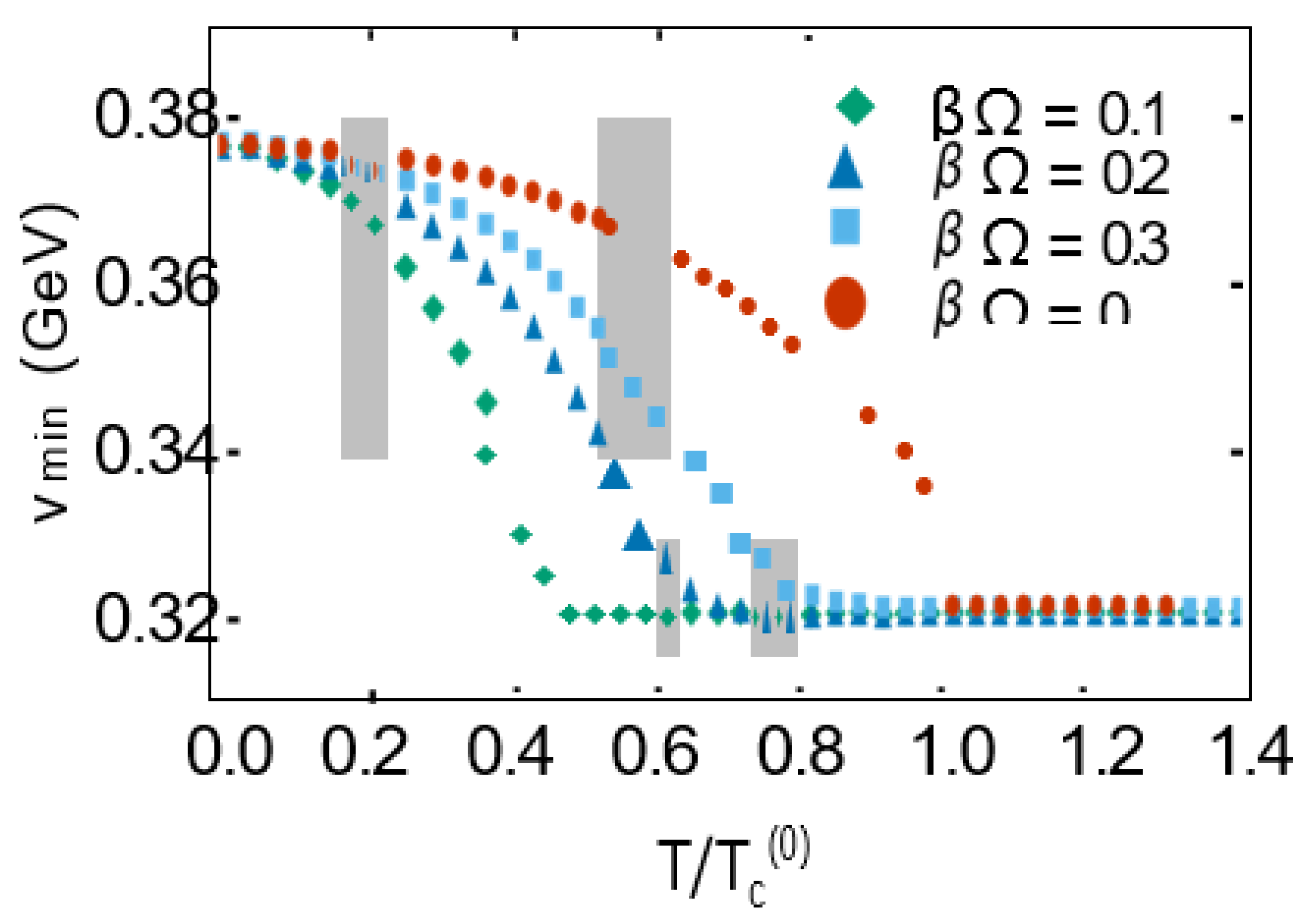

for a rotating and a nonrotating Bose gas, respectively. The corresponding results are demonstrated in

Figure 9. Because of the specific form of the ring potentials Vring and

from (III.70) and (III.73), including in particular (mi

2 + Π

mat)3/2, there is a certain value of v below which the potential is undefined (imaginary). Let us denote this value by

⋆. In both rotating and non- rotating cases v⋆ ≃ 0.319 GeV. As it is shown in

Figure 9, the minima decrease with increasing temperature and converge towards

⋆. Let us denote the temperature at which

min = v⋆ with T⋆ for Ω

0 and T⋆

(0) for Ω = 0. For Ω = 0, T⋆

(0) ≃ 0.300 GeV, and as it is shown in

Figure 9, the transition to v⋆ is discontinuous (red circles). For Ω

0, however, T⋆ < T⋆

(0) and increases with increasing βΩ, similar to the results presented in

Figure 8. Moreover, in contrast to the case of Ω = 0, the transition to

⋆ for all values of βΩ

0 is continuous.

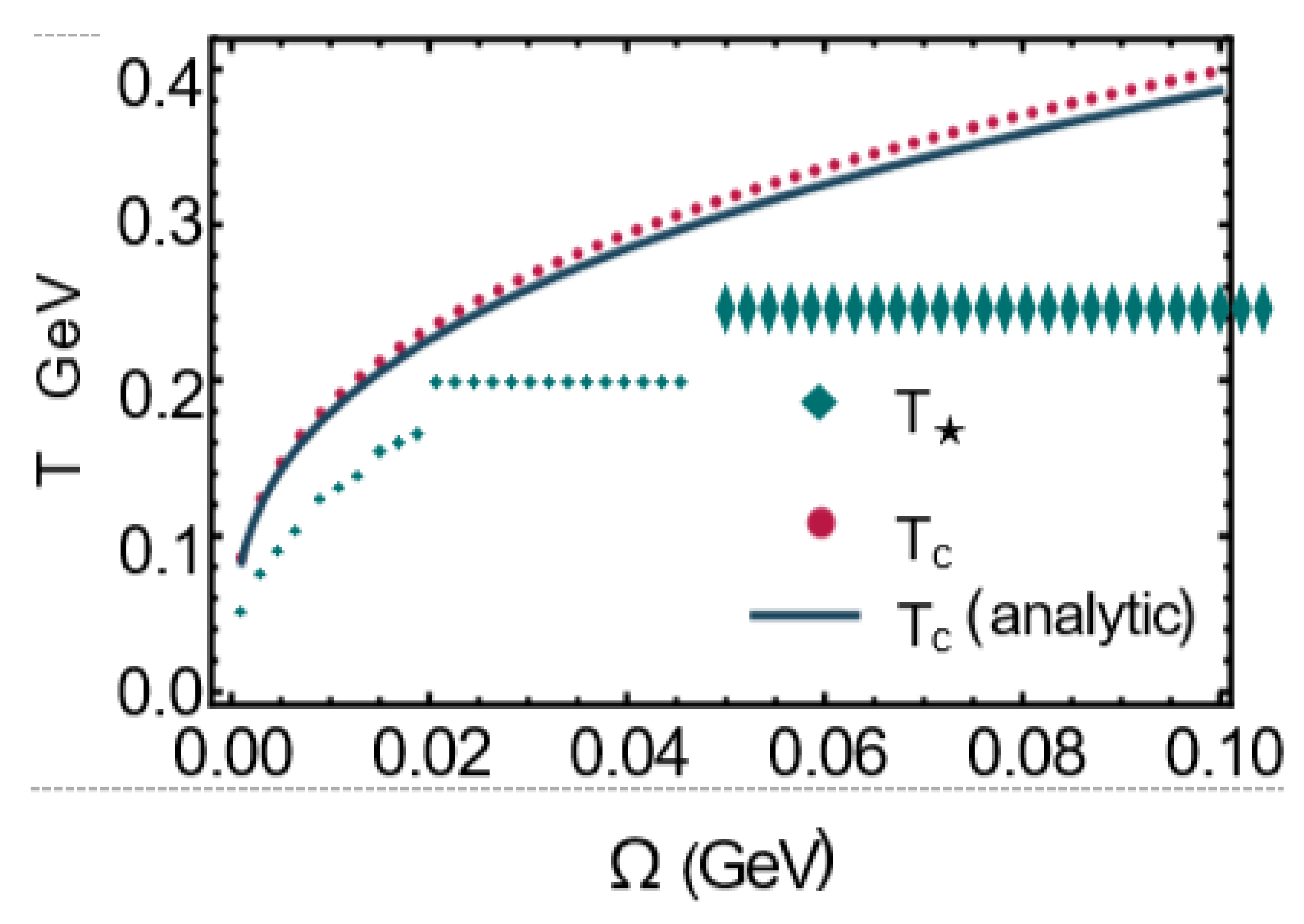

In

Figure 10, the phase diagram Tc-Ω is plotted for two cases: The blue solid curve demonstrates Tc from (III.5) arising from Vcl + VT. Red dots denote the Ω depen- dence of Tc arising from the potential Vtot − Vring. A comparison between these data reveals the effect of Vvac in increasing Tc. Apart from the Ω dependence of Tc, the Ω dependence of T⋆ is demonstrated in

Figure 10. It arises by adding the ring contribution to Vcl + VT + Vvac, as described above. According to the results demonstrated in

Figure 10, considering Vring decreases Tc. But, simi- lar to Tc, T⋆ also increases with increasing Ω. It should be emphasized that the transition shown in

Figure 8 is a crossover, since

⋆

0.

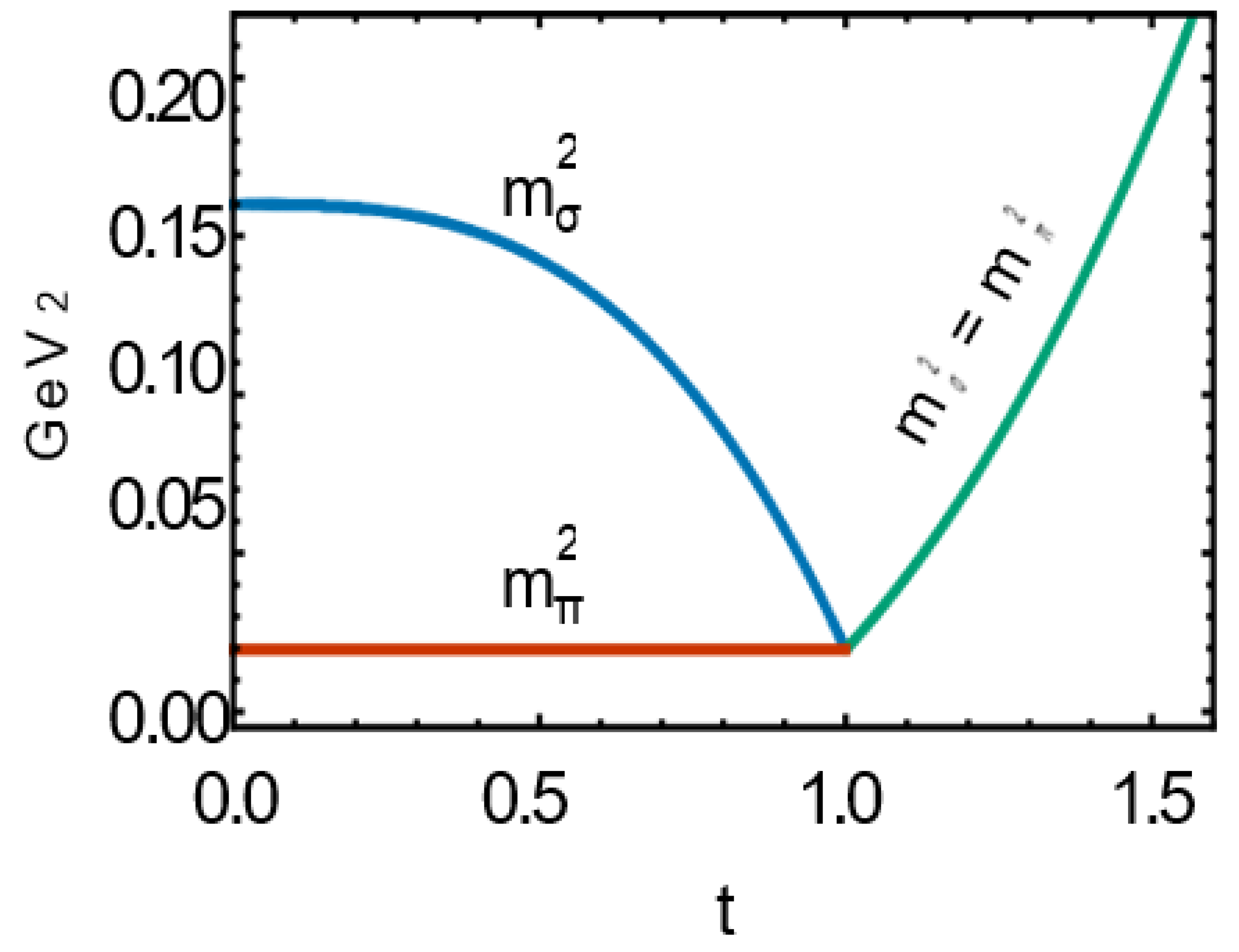

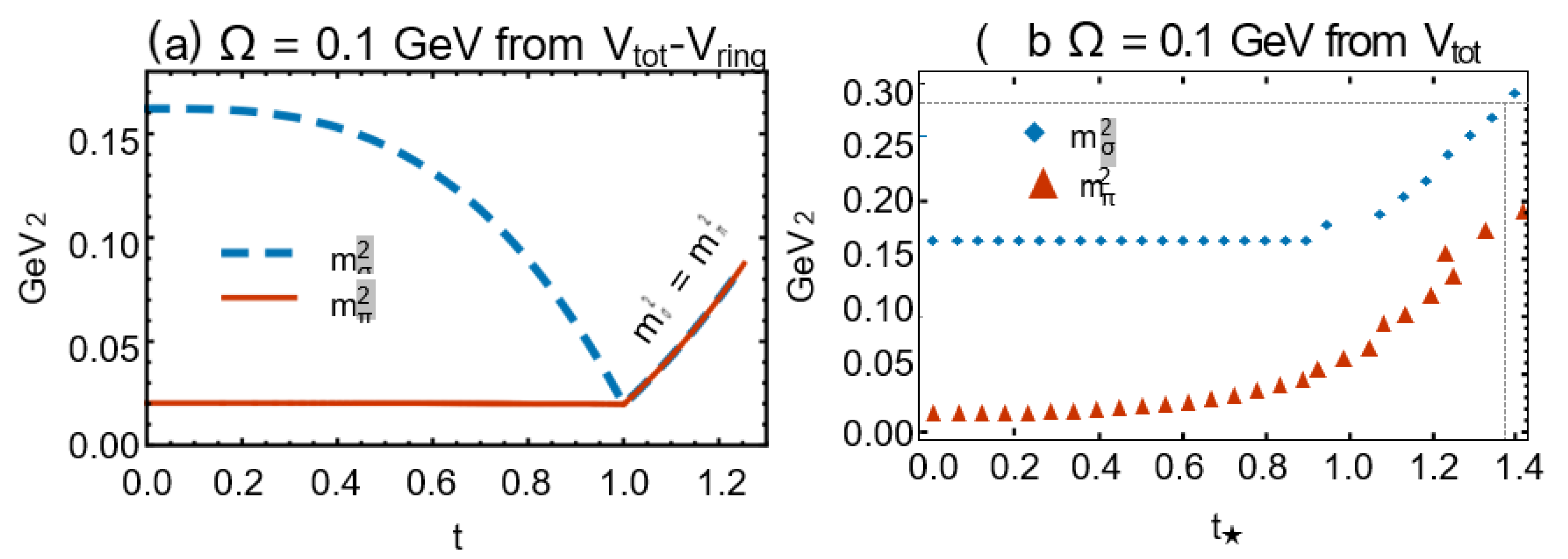

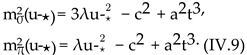

In Sec. III B, the masses m12, i = 1, 2 including the one-loop correction are determined [see (III.29)]. Identi- fying m12 with mσ2 and m22 with mπ2, we arrive at

Using the data for

min

2 arising from the solution of the gap equation (IV.3) and (IV.5), and evaluating mσ

2(v

2) and mπ

2 (v

2) from (IV.7) at m2 in for a fixed βΩ, the t = T/Tc dependence of mσ

2 and mπ

2 is determined. In

Figure 11(a), the dependence of mσ

2(

2min) and mπ

2 (

2min) with vmin arising from (IV.3) on the reduced tempera- ture t = T/Tc is plotted for fixed βΩ = 0.1. Here, the contribution of the ring potential is not taken into ac- count. Hence, a continuous phase transition occurs with the critical temperature Tc ∼ 0.399 GeV for Ω = 0.1 GeV. In contrast, in

Figure 11(b), mσ

2 and mπ

2 are determined by plugging the data of

min arising from (IV.5), with Vtot including the ring potential. Hence, the difference between the plots demonstrated in Figs. 11(a) and 11(b) arises from the contribution of the nonperturbative ring potential. As we have mentioned above, when the ring potential is taken into account, the data demonstrated in

Figure 9 do not describe a true transition, since

⋆ is not zero. The reduced temperature in

Figure 11(b) is thus defined by t⋆ ≡ T/T⋆, where, according to the data pre- sented in

Figure 10 T⋆ ∼ 0.278 GeV for Ω = 0.1.

Let us compare the results demonstrated in

Figure 11(a) with that in

Figure 5. In both cases, before the phase transition at t < 1,

decreases with increasing t. Moreover, whereas in

Figure 5,

remains constant, it slightly decreases once the Vvac contribution is taken into account.

After the transition, at t ≥ 1, becomes equal to and they both increase with increasing t. It is straight- forward to verify this statement using equation (IV.7). Given that, in this case, the minima of the potential at t ≥ 1 are zero, it follows that both masses are equal, specifically (0) = (0), once we substitute min = 0 into (IV.7).

This behavior is expected from the case of Ω = 0 and in the framework of fermionic Nambu-Jona–Lasinio (NJL) model: As noted in [

45], in the symmetry-broken phase,

>

. As the transition temperature is approached,

decreases, and at a certain dissociation temperature Tdiss, the masses mσ and mπ become de-generate. This temperature is characterized by mσ (Tdiss) = 2mπ (Tdiss). (IV.8)

As it is described in [

45], σ mesons dissociates into two pions because of the appearance of an s-channel pole in the scattering amplitude π + π → π + π. In this process a σ meson is coupled to two pions via a quark triangle. In the symmetry-restored phase, at t ≥ 1, mσ becomes equal to mπ. They both increase with increasing T [

45,

46].

In

Table 1, the σ dissociation temperatures are listed for Ω = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 GeV. The data in the second (third) column correspond to Tdiss (

) for the case when

min is the solution of (IV.3) [(IV.5)] for Ω

0 and (IV.4) [(IV.6)] for Ω = 0. Comparing Tdiss and

with Tc and T⋆ shows that Tdiss < Tc and similarly

< T⋆. The property Tdiss

Tc is because we are working with mπ

0. Let us notice that, as aforementioned, the σ dissociation temperature is originally introduced in a fermionic NJL model [

45]. In this model, nonvanishing mπ

0

0 implies a crossover transition charac- terized by Tdiss

Tc. It seems that in the bosonic model studied in the present work, a nonvanishing pion mass leads similarly to Tdiss

Tc.

The behavior demonstrated in

Figure 11(a) changes once the contribution of the ring potential is taken into account. As it is shown in

Figure 11(b), in the symmetry- broken phase at t⋆ < 1, mσ decreases slightly with T, while mπ increases with T. Moreover, in contrast to the case in which Vring is not taken into account, mσ and mπ are not equal at t ≥ 1. This observation highlights the ef- fect of nonperturbative ring contributions on the relation between mσ and mπ, mainly in the symmetry-restored phase. This behavior is directly related to the fact that the effect illustrated in

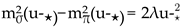

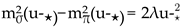

Figure 9 is a crossover once the ring contribution is considered: Plugging u-⋆ into (IV.7), the masses of σ and π mesons are given by

Their difference is thus given by

and remains constant in t. This fact can be observed in

Figure 11(b) at t⋆ ≥ 1.

V. Summary and Conclusions

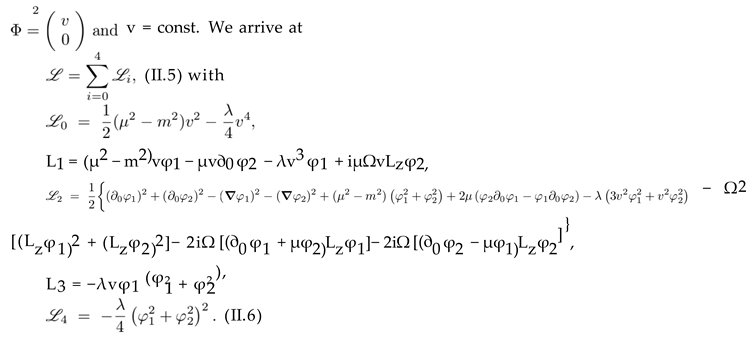

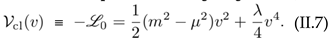

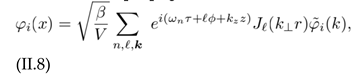

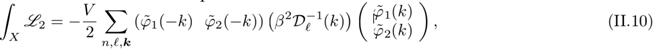

In this paper, we extended the study of the effects of rigid rotation on BE condensation of a free Bose gas in [

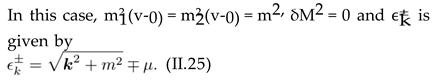

30], to a self-interacting charged Bose gas under rigid rotation. In the first part, we considered the Lagrangian density of a complex scalar field 夕 with mass m, in the presence of chemical potential μ and angular velocity Ω. The interaction was introduced through a λ(夕⋆ 夕) term. This Lagrangian is invariant under global U(1) transfor- mation. To investigate the spontaneous breaking of this symmetry, we chose a fixed minimum with a real com- ponent u, and evaluated the original Lagrangian around this minimum to derive a classical potential. Then, we applied an appropriate Bessel-Fourier transformation to determine the free propagator of this model, expressed in terms of two masses m1 and m2, corresponding to the two components of the complex field 夕. These masses depend explicitly on u,λ, and m, and played a crucial role when the spontaneous breaking of U(1) symmetry was consid- ered in a realistic model that includes σ and π mesons. Using the free boson propagator of this model, we derived the thermodynamic potential of self-interacting Bose gas at finite temperature T. This potential consists of a vac- uum and a thermal part. Along with the classical poten- tial, this forms the total thermodynamic potential of this model V

tot from (II.24). This potential is expressed in terms of the energy dispersion relation

from (II.15), and explicitly depends on lΩ. A novel result presented here is that, although lΩ appears to resemble a chemical potential in combination with

in Vtot, the chemical potential μ affects

in a nontrivial manner. The effec-tive chemical potential μeff = μ + lΩ appears solely in a noninteracting Bose gas under rotation (see the special case 1 in Sec. II D and compare the thermodynamic po- tential with that appearing in [

30]).

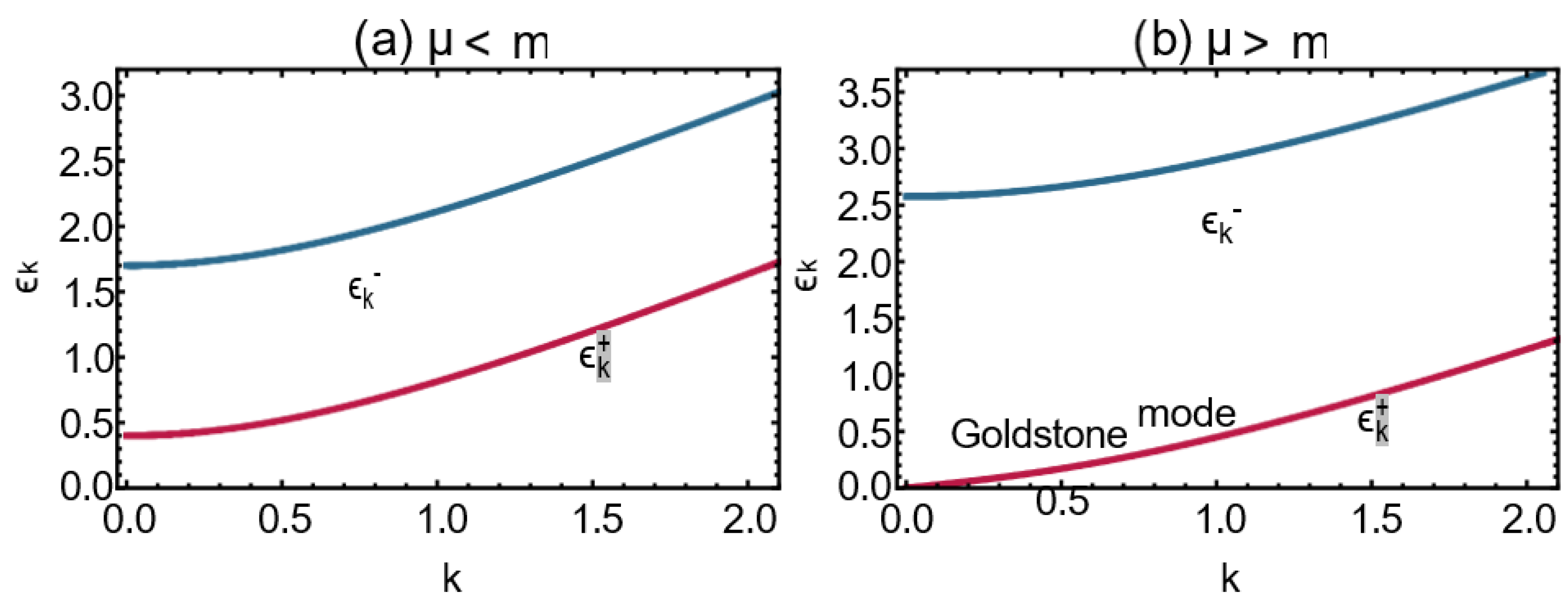

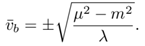

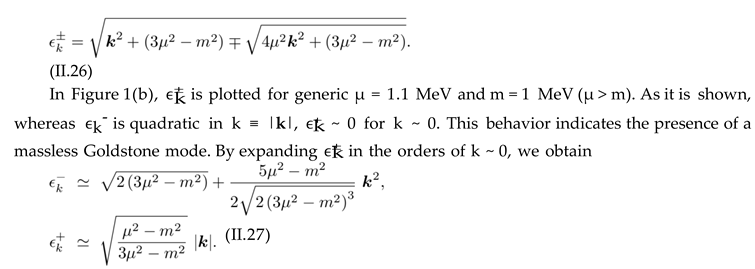

For λ,μ 0, we explored two cases μ > m and μ < m. The former corresponds to the phase where U(1) symme- try is broken, while the latter describes the symmetry- restored phase. By expanding the two branches of the energy dispersion relation around k ~ 0 in the symmetry- broken phase, we identified ∈k+ and ∈k- as phonon and roton, with the latter representing a massless Goldstone mode. Upon comparison with analogous results for a nonrotating and self-interacting Bose gas, we found that rigid rotation does not alter the behavior of at k ~ 0. This is mainly because rotation appears in terms of lΩ within Vtot, rather than directly affecting .

In the second part of this paper, we examined the effect of rigid rotation on the spontaneous breaking of U(1) symmetry in an interacting Bose gas at μ = 0 (see Sec. III). In this case, where m

2 < 0, we replaced m

2 with −c

2, where c

2 > 0. By introducing an additional term to the original Lagrangian, we defined a new mass, a

2= c

2 + m0

2. We demonstrated that the minimum of the classical potential is nonzero, indicating a sponta- neous breaking of U(1) symmetry. We then addressed the question about the position of this minimum, specif- ically its dependence on T and Ω, after accounting for the thermal part of the effective potential combined with the classical potential. To investigate this, we performed a high-temperature expansion of the thermal part of the potential, utilizing a method originally introduced in [

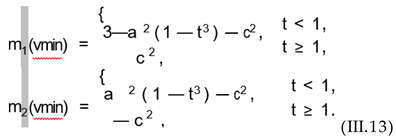

30]. This approach enabled us to sum over the angular mo- mentum quantum numbers ℓ for small values of βΩ, al- lowing us to derive both the critical temperature of the phase transition Tc and the dependencies of the mini- mum of the potential on T and Ω. At this stage, we have Tc ∝ λ

-1/3, which is in contrast to the Tc

(0) ∝ λ

-1/2 for a nonrotating Bose gas. In addition, Tc ∝ Ω

1/3. Let us remind that the critical temperature of a BEC transi- tion for a noninteracting Bose gas in nonrelativistic and ultrarelativistic limits are Tc ∝ Ω

2/5 and Tc ∝ Ω

1/4, re- spectively [

30]. This demonstrates the effect of rotation in changing the critical exponents of different quantities in the symmetry-broken phase.

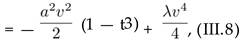

We defined a reduced temperature t = T/Tc, and showed that in the symmetry-broken phase, the minimum men- tioned above depends on (1-t3), while for a nonrotating Bose gas this dependence is (1 - ), where t0 = T/Tc(0). In the symmetry-restored phase, this minimum vanishes. This indicates a continuous phase transition in both non- rotating and rotating Bose gases. Plugging these minima into (v) and (v), it turned out that at t ≥ 1, i.e., in the symmetry-restored phase m1 and m2 are imaginary. Since, according to our arguments in Sec. III, m2 is the mass of a Goldstone mode, we expect that in the chiral limit, i.e., when m0 = 0, it vanishes in the symmetry- broken phase at t < 1. However, as it is shown in (III.13), < 0 in this phase.

To resolve this issue, we followed the method used in [

40] and added the thermal part of one-loop self-energy diagram to the above results. In contrast to the case of nonrotating bosons, where the thermal mass square is proportional to λT

2, for rotating bosons it is proportional to λT

3 /Ω. To arrive at this result, a summation over ℓ was necessary. This was performed by utilizing a method originally introduced in [

30]. Adding this perturbative contribution to

, i = 1, 2 at t < 1 and t ≥ 1, we showed that the Goldstone theorem is satisfied in the chiral limit [see Sec. III C].

In Secs. III D and III E, we added the vacuum and nonperturbative ring potentials to the classical and ther- mal potentials. The main novelty of these sections lies in the final results for these two parts of the total potential, specifically the method we employed to sum over ℓ. Ac- cording to this method the vacuum part of the potential for a rigidly rotating Bose gas is the same as that for a nonrotating gas. We followed the method described in [

43] to dimensionally regularize the vacuum potential. As concerns the ring potential, we present a novel method to compute this nonperturbative contribution to the ther- modynamic potential. In particular, we summed over ℓ by performing a ζ-function regularization. In Sec. III F, we presented a summary of these results.

In Sec. IV, we used the total thermodynamic poten- tial presented in Sec. III to study the effect of rotation on the spontaneous U(1) symmetry breaking of a realistic model including σ and π mesons. Fixing free parameters mσ, mπ, and λ, and identifying m1 and m2 with the me- son masses mσ and mπ, we obtained numerical values for c and a (see Sec. III A). First, we determined the T de- pendence of the minima of the total thermodynamic po- tential, excluding the ring contribution. According to the results presented in

Figure 8, rotation decreases the critical temperature of the U(1) phase transition. Additionally, it is shown that Tc increases with increasing Ω. In [

30], it is shown that the critical temperature of the BEC in a noninteracting Bose gas under rotation behaves in the same manner. This phenomenon indicates that rotation enhances the condensation. Recently, a similar result was observed in [

47], where it is demonstrated that the inter- play between rotation and magnetic fields significantly increases the critical temperature of the superconducting phase transition.

To explore the effect of nonperturbative ring poten- tial, we numerically solved the gap equation correspond- ing to the total thermodynamic potential and determined its minima

min. Because of the specific form of the ring potential, there was a certain

⋆ through which all the curves v-min (T,Ωf), independent of the chosen Ωf, con- verge (see

Figure 9). Moreover, the transition for Ω = 0 turned out to be discontinuous, while it is continuous for all Ω

0. As it is demonstrated in Figure (10), T⋆ increases with increasing Ω.

Finally, we determined the T dependence of the masses mσ and mπ mesons for a fixed value of Ω. To achieve this, we utilized (IV.7) along with

min, which is derived from Figs. 8and 9. The plot shown in

Figure 11(a), based on the total potential excluding the ring contribu- tion, is representative of the T dependence of mσ and mπ (see e.g., [

46]). However, when we include the ring contribution, the shape of the plots changes, especially at T > T⋆. The reason is that considering the ring potential changes the order of the phase transition from a second order transition to continuous (for Ω

0) or discontinu- ous (for Ω = 0) a crossover. In this context, we numer- ically determined the σ dissociation temperature Tdiss, which may serve as an indicator for type of the transi- tion into the symmetry-restored phase. We showed that Tdiss < Tc and

< T⋆, as expected from a crossover transition [

46].

It would be intriguing to extend the above findings, in particular those from Sec. III, to the case of nonvanish- ing chemical potential. In [

48], the kaon condensation in a certain color-flavor locked phase (CFL) of quark mat- ter is studied at nonzero temperature. This is a state of matter which is believed to exist in quark matter at large densities and low temperatures. Large densities at which the color superconducting CFL phase is built are expected to exist in the interior of neutron stars. One of the main characteristic of these compact stars, apart from densities, is their large angular velocities. It is not clear how a rigid rotation, like that used in the present paper, may affect the formation of pseudo-Goldstone bosons and the critical temperature of the BE condensation in this nontrivial environment. We postpone the study of this problem to our future publication.

and perform the shift φi → Φi + φi with

and perform the shift φi → Φi + φi with

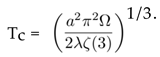

. (III.5) In [30], the BE transition in a noninteracting Bose gas under rigid rotation is studied. It is shown that in nonrel- ativistic regime Tc ∝ Ω2/5 and in ultrarelativistic regime Tc ∝ Ω 1/4. In the present case of interacting Bose gas, similar to that noninteracting cases, the critical temper- ature increases with increasing Ω.

. (III.5) In [30], the BE transition in a noninteracting Bose gas under rigid rotation is studied. It is shown that in nonrel- ativistic regime Tc ∝ Ω2/5 and in ultrarelativistic regime Tc ∝ Ω 1/4. In the present case of interacting Bose gas, similar to that noninteracting cases, the critical temper- ature increases with increasing Ω.

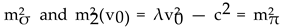

with v0 the classical minimum from (III.2). Moreover, we choose m0 in (III.1) equal to mπ. For mσ = 400 MeV, and mπ = 140 MeV, we obtain

with v0 the classical minimum from (III.2). Moreover, we choose m0 in (III.1) equal to mπ. For mσ = 400 MeV, and mπ = 140 MeV, we obtain

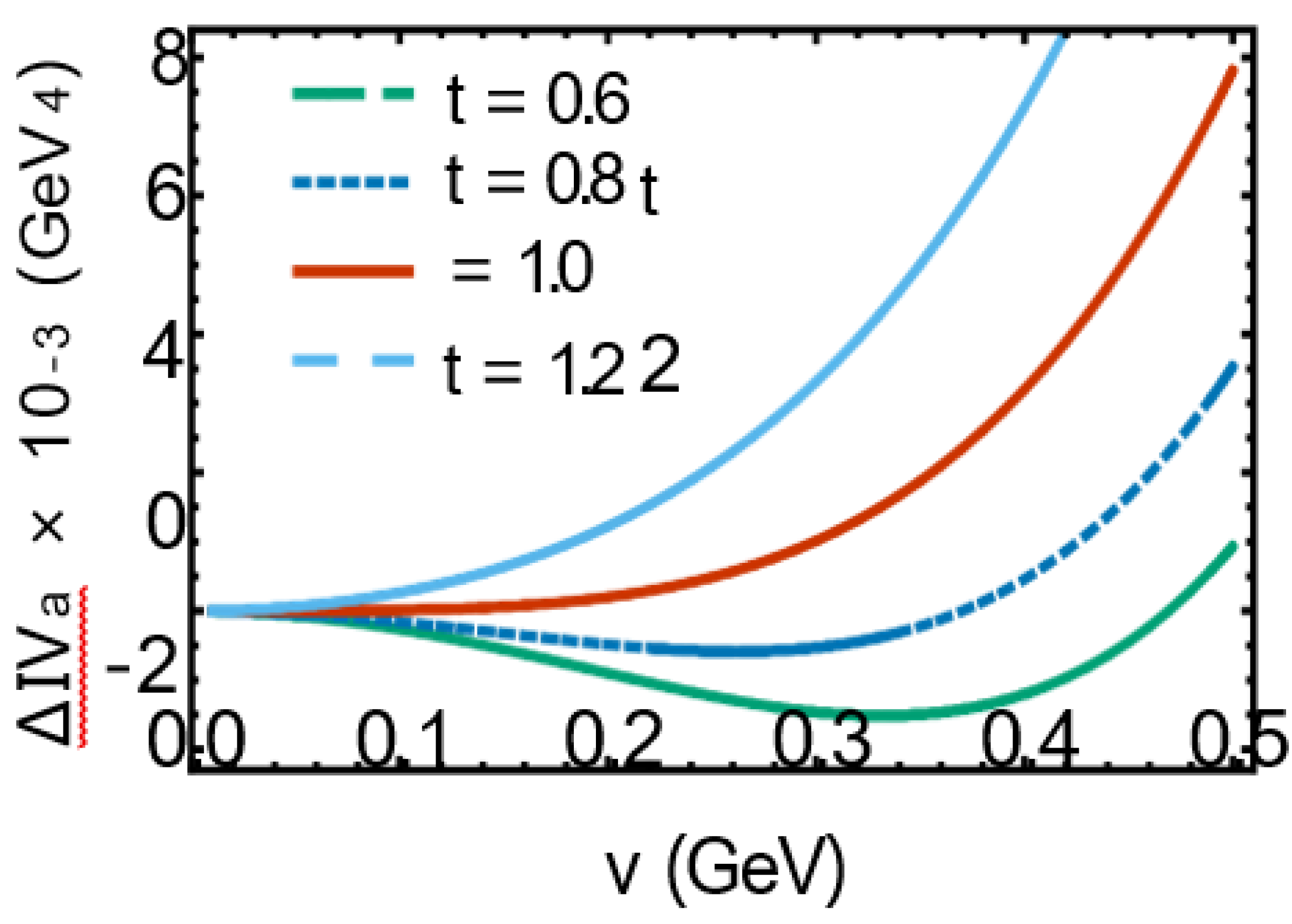

is plotted in Figure 2 at t = 0.6, 0.8 in the symmetry-broken phase and t = 1.2 in the symmetry-restored phase. At t = 1 a phase transition from the symmetry-broken phase to a symmetry-restored phase occurs. Let us notice, that the effect of rotation consists of changing the power of t in (III.6) and (III.8) from t2 to t3. This is apart from the Ω dependence of the critical temperature Tc from (III.5) (see Figure 7).

is plotted in Figure 2 at t = 0.6, 0.8 in the symmetry-broken phase and t = 1.2 in the symmetry-restored phase. At t = 1 a phase transition from the symmetry-broken phase to a symmetry-restored phase occurs. Let us notice, that the effect of rotation consists of changing the power of t in (III.6) and (III.8) from t2 to t3. This is apart from the Ω dependence of the critical temperature Tc from (III.5) (see Figure 7).

(III.11)

(III.11)

, we arrive at

, we arrive at

be considered in this computation (see Figure 3),

be considered in this computation (see Figure 3),

and i = 1; 2. Using this notation, it turns out that

and i = 1; 2. Using this notation, it turns out that To evaluate Πi from (III.16), we follow the same steps as presented in [30]. The Matsubara summation is eval- uated with

To evaluate Πi from (III.16), we follow the same steps as presented in [30]. The Matsubara summation is eval- uated with

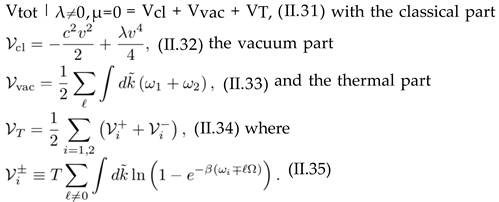

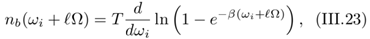

(III.21) Having in mind that in nb (!i ± `Ω), we must have eβ(ωi ±ℓΩ) - 1 > 0, it is possible to limit the summation over `. We thus obtain

(III.21) Having in mind that in nb (!i ± `Ω), we must have eβ(ωi ±ℓΩ) - 1 > 0, it is possible to limit the summation over `. We thus obtain Let us notice that in the term including nb (!i - `Ω) an additional shift ` → -` is performed. To carry out the summation over ` and eventually the integration over k⊥ and kz, we use

Let us notice that in the term including nb (!i - `Ω) an additional shift ` → -` is performed. To carry out the summation over ` and eventually the integration over k⊥ and kz, we use

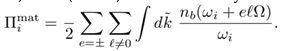

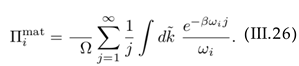

(III.25) The summation over ` can be performed by making use of (A.4). Assuming Ω < 1 and using (A.5), Π1mat reads

(III.25) The summation over ` can be performed by making use of (A.4). Assuming Ω < 1 and using (A.5), Π1mat reads

(III.27) The first term in (III.27) is analogous to the thermal mass λT2 /3 in a nonrotating interacting Bose gas [40] and the ellipsis includes higher order corrections of Π1mat in βmi.

(III.27) The first term in (III.27) is analogous to the thermal mass λT2 /3 in a nonrotating interacting Bose gas [40] and the ellipsis includes higher order corrections of Π1mat in βmi.

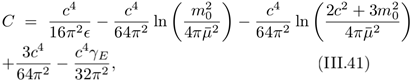

(III.32)

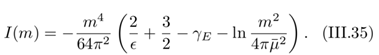

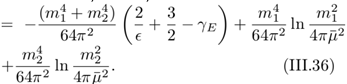

(III.32) (III.33) with ϵ = 3-d. Here, d is the dimension of spacetime and denotes an appropriate energy scale. Later, we show that can be eliminated from the computation. Utilizing

(III.33) with ϵ = 3-d. Here, d is the dimension of spacetime and denotes an appropriate energy scale. Later, we show that can be eliminated from the computation. Utilizing

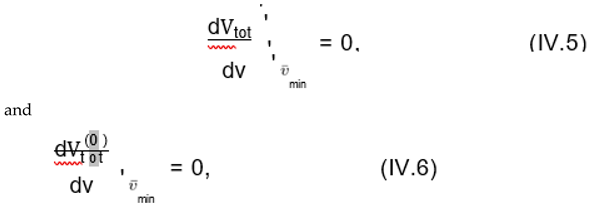

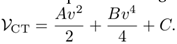

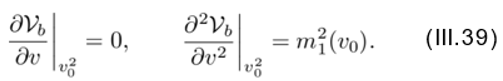

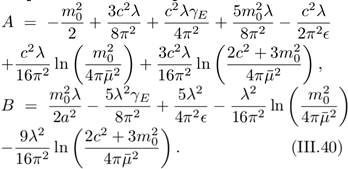

(III.38) The coefficients A and B are determined by utilizing two prescriptions

(III.38) The coefficients A and B are determined by utilizing two prescriptions

(III.43)

(III.43)

and remains constant in t. This fact can be observed in Figure 11(b) at t⋆ ≥ 1.

and remains constant in t. This fact can be observed in Figure 11(b) at t⋆ ≥ 1.