Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

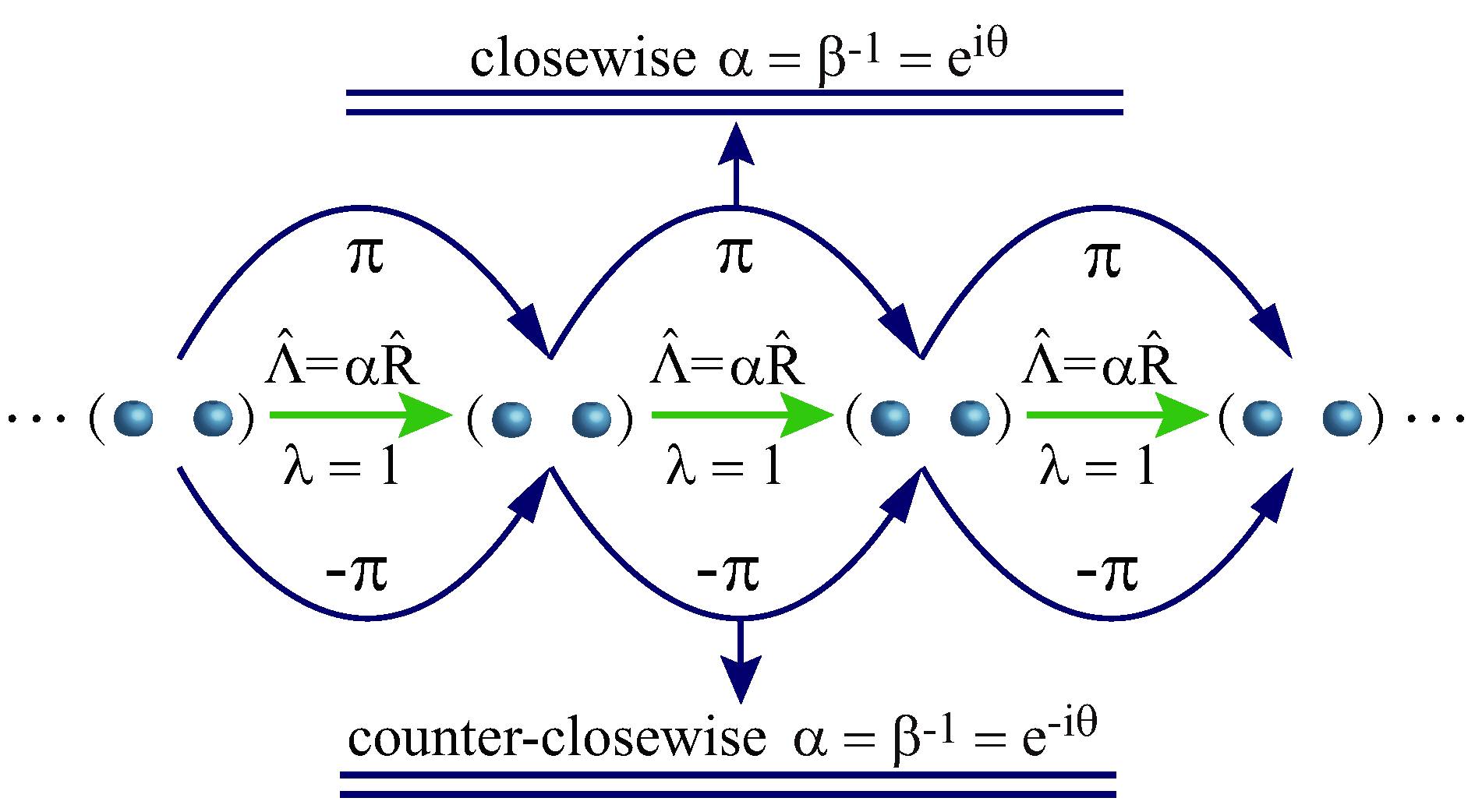

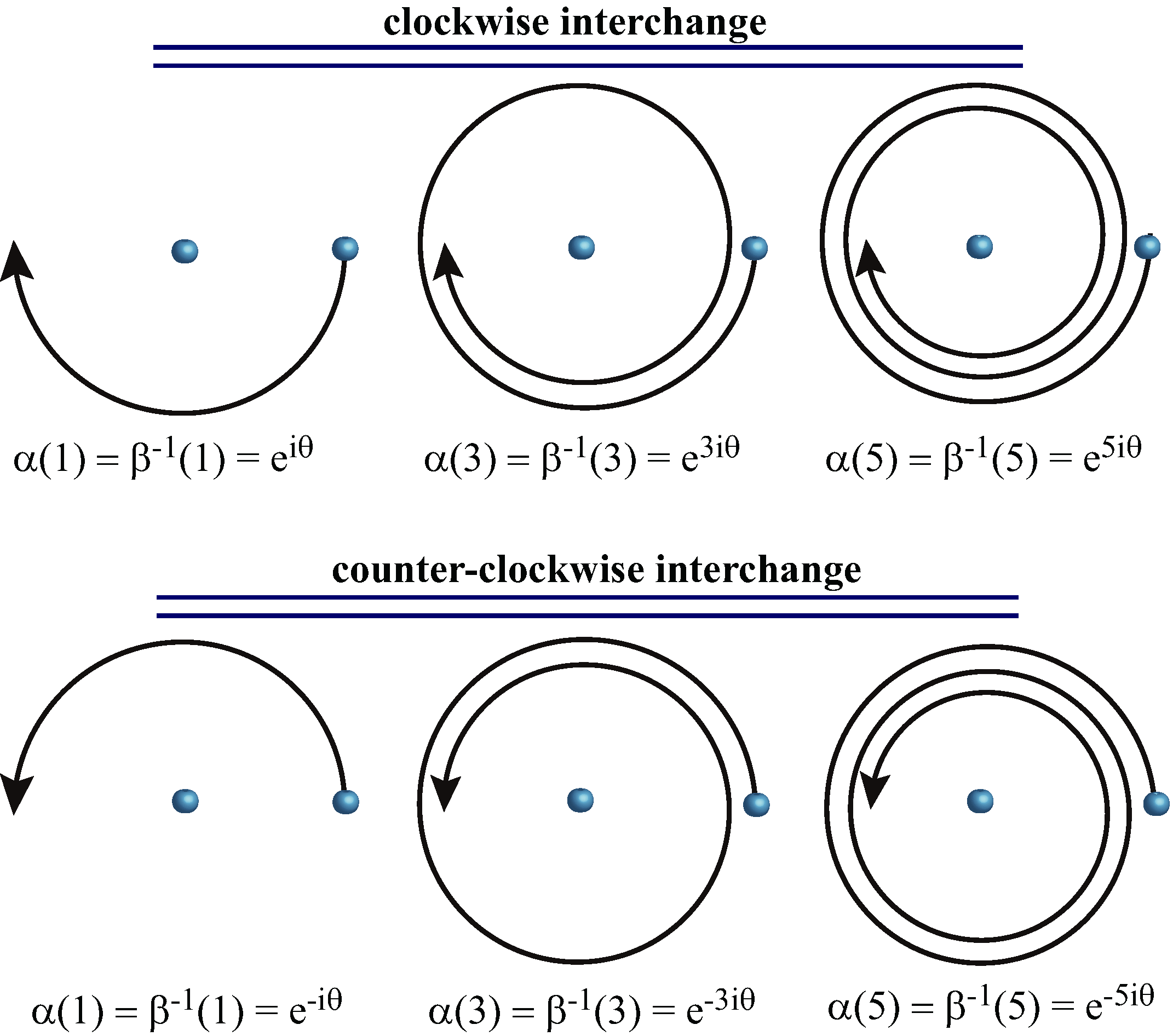

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Rigorous Derivation of the Relationship Between and

3. Dynamical Dual-Phase Generation from Topology and Time Evolution

4. Phase Dynamics in Bosonic and Fermionic Systems

5. Discussion

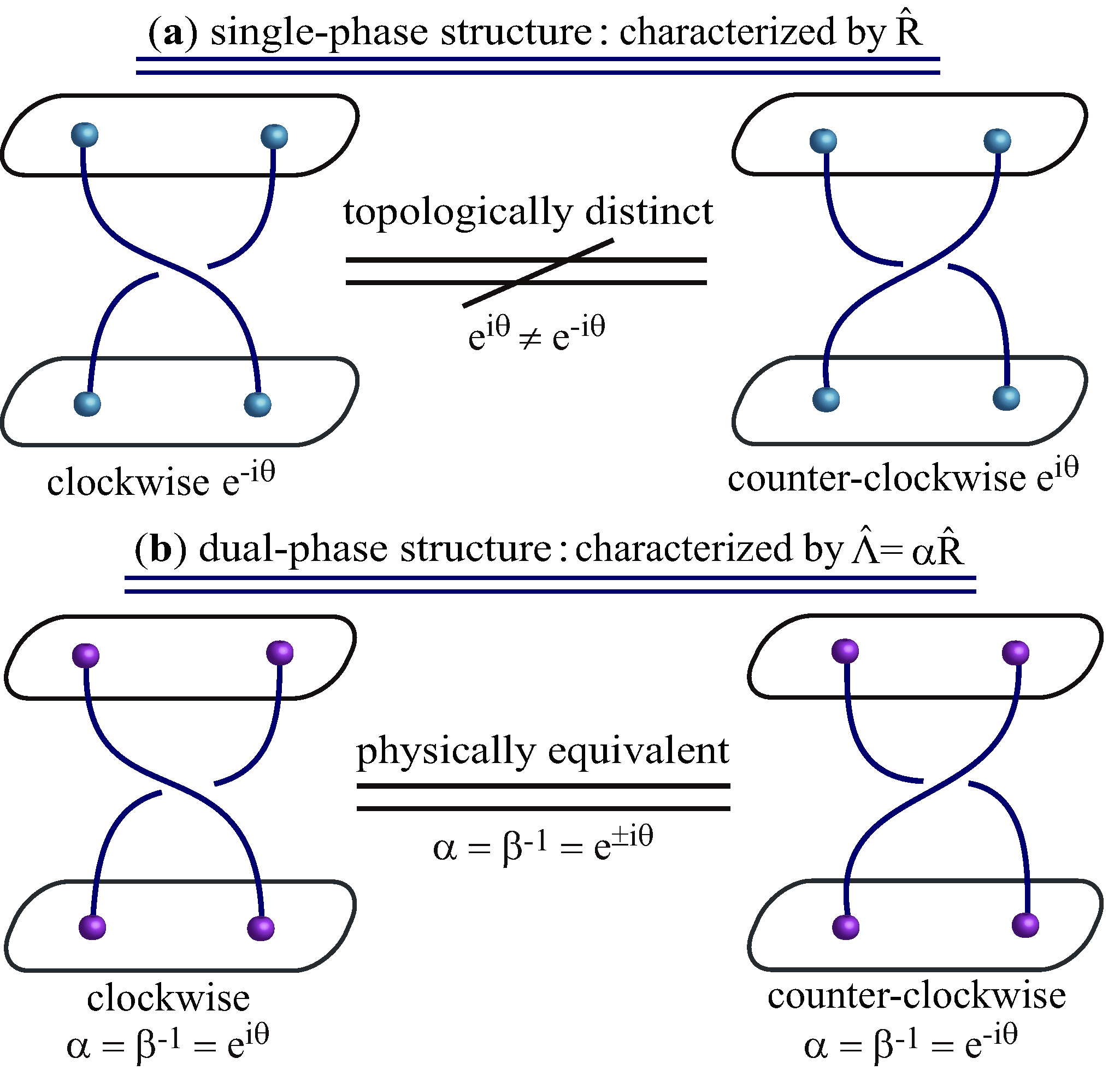

5.1. Dual-Phase Structure of Identical Particle

5.2. Challenges to the Conventional Existence of Non-Abelian Anyons

5.3. The -Operator Representation for Quantum Many-Body Systems

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Wang, J.H. The operator approach for representing the symmetry of many-electron systems (series I). AIP Advances 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.F. Methods of Electronic Structure Theory; Plenum: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, W.; Müller, B. Quantum Mechanics: Symmetries, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weissbluth, M. Atoms and Molecules; Academic Press, 1978.

- Slater, J.C. The theory of complex spectra. Phys. Rev. 1929, 34, 1293–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiah, A.; Greenberg, O.W. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B248–B267. [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum mechanics: non-relativistic theory; Pergamon: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczek, F. Quantum Mechanics of Fractional-Spin Particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arovas, D.P.; Schrieffer, R.; Wilczek, F.; Zee, A. Statistical Mechanics of Anyons. Nucl. Phys. B 1985, 251, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1984, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.; Simon, S.H.; Stern, A.; Freedman, M.; Sarma, S.D. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 1083–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Liang, S.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Direct observation of anyonic braiding statistics. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinaas, J.M.; Myrheim, J. On the theory of identical particles. Nuovo Cimento B 1977, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klitzing, K.V.; Dorda, G.; Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized hall resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, D.C.; Stormer, H.L.; Gossard, A.C. Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1559–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, R.B. Anomalous Quantum Hall Effect: An Incompressible Quantum Fluid with Fractionally Charged Excitations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Zee, A. Broken SU(5) and proton decay. Phys. Lett. B 1984, 147, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Magnetic flux, angular momentum, and statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Quantum mechanics of fractional-spin particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, N.; Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 10267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.G.; Zee, A. Quantum statistics and superconductivity in two spatial dimensions. Nucl. Phys. B 1990, 15, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, B.I.; March-Russell, J.; Wilczek, F. Consequences of time-reversal-symmetry violation in models of high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 40, 8726–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Read, N. Nonabelions in the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect. Nucl. Phys. B 1991, 360, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.J.; Alicea, J.; Shtengel, K. Exotic Non-Abelian Anyons from Conventional Fractional Quantum Hall States. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkeshli, M.; Jian, C.M.; Qi, X.L. Twist Defects and Projective Non-Abelian Braiding Statistics. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 045130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, N.H.; Berg, E.; Refael, G.; Stern, A. Fractionalizing Majorana Fermions: Non-Abelian Statistics on the Edges of Abelian Quantum Hall States. Phys. Rev. X 2012, 2, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.E.; Halperin, B.I. Fractional charge and fractional statistics in the quantum Hall effects. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84, 076501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.A. Non-Abelian Statistics of Half-Quantum Vortices in p-Wave Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Seiberg, N. Classical and Quantum Conformal Field Theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 1989, 123, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbo, T.D.; Imbo, C.S.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. Identical Particles, Exotic Statistics and Braid Groups. Phys. Lett. B 1990, 234, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mong, R.S.K.; Clarke, D.J.; Alicea, J.; Lindner, N.H.; Fendley, P.; Nayak, C.; Oreg, Y.; Stern, A.; Berg, E.; Shtengel, K.; et al. Universal Topological Quantum Computation from a Superconductor-Abelian Quantum Hall Heterostructure. Phys. Rev. X 2014, 4, 011036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 2003, 303, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.H.; Kitaev, A.; Larsen, M.J.; Wang, Z. Topological Quantum Computation. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2003, 40, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicea, J.; Oreg, Y.; Refael, G.; von Oppen, F.; Fisher, M.P.A. Non-Abelian statistics and topological quantum information processing in 1D wire networks. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.; Lindner, N.H. Topological Quantum Computation—From Basic Concepts to First Experiments. Science 2013, 339, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, A.; Wootton, J.R.; Loss, D. Parafermions in a Kagome Lattice of Qubits for Topological Quantum Computation. Phys. Rev. X 2015, 5, 041040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, M.; Heiblum, M.; Umansky, V.; Feldman, D.E.; Oreg, Y.; Stern, A. Observation of half-integer thermal Hall conductance. Nature 2018, 559, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.K.W.; Feldman, D.E. Partial equilibration of integer and fractional edge channels in the thermal quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 085309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Fallahi, S.; Sahasrabudhe, H.; Rahman, R.; Liang, S.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Aharonov–Bohm interference of fractional quantum Hall edge modes. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrega, M.; Chirolli, L.; Heun, S.; et al. Anyons in quantum Hall interferometry. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, H.K.; Biswas, S.; Ofek, N.; Umansky, V.; Heiblum, M. Anyonic interference and braiding phase in a Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Nat. Phys. 2023, 19, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, R.L.; Shtengel, K.; Nayak, C.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; Chung, Y.J.; Peabody, M.L.; Baldwin, K.W.; West, K.W. Interference measurements of non-Abelian e/4 and Abelian e/2 quasiparticle braiding. Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13, 011028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourik, V.; Zuo, K.; Frolov, S.M.; Plissard, S.R.; Bakkers, E.P.A.M.; Kouwenhoven, L.P. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 2012, 336, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.T.; Yu, C.L.; Huang, G.Y.; Larsson, M.; Caroff, P.; Xu, H.Q. Anomalous zero-bias conductance peak in a Nb-InSb nanowire-Nb hybrid device. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Ronen, Y.; Most, Y.; Oreg, Y.; Heiblum, M.; Shtrikman, H. Zero-bias peaks and splitting in an Al-InAs nanowire topological superconductor as a signature of Majorana fermions. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.M.; Higginbotham, A.P.; Madsen, M.; Kuemmeth, F.; Jespersen, T.S.; Nygård, J.; Krogstrup, P.; Marcus, C.M. Exponential protection of zero modes in Majorana islands. Nature 2016, 531, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.T.; Vaitiekenas, S.; Hansen, E.B.; Danon, J.; Leijnse, M.; Flensberg, K.; Nygård, J.; Krogstrup, P.; Marcus, C.M. Majorana bound state in a coupled quantum-dot hybrid-nanowire system. Science 2016, 354, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, P.; Stenger, J.; Hocevar, M.; Car, D.; Plissard, S.R.; Bakkers, E.P.A.M.; Stanescu, T.D.; Frolov, S.M. Experimental phase diagram of zero-bias conductance peaks in superconductor/semiconductor nanowire devices. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, R.A.; Kouwenhoven, L. Majorana qubits for topological quantum computing. Phys. Today 2020, 73, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayyalha, M.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, R.; Shin, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Y.F.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, L.; Fijalkowski, K.M.; et al. Absence of evidence for chiral Majorana modes in quantum anomalous Hall-superconductor devices. Science 2020, 367, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, B.I. APS Medal for exceptional achievement in research: Topology and other tools in condensed matter physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, S. Quantum computing’s reproducibility crisis: Majorana fermions. Nature 2021, 592, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, N.P.; Itoh, K.M.; Kim, D.; Mehta, K.K.; Northrup, T.E.; Paik, H.; Palmer, B.S.; Samarth, N.; Sangtawesin, S.; Steuerman, D.W. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science 2021, 372, eabb2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.G. Quantum Many-Body Theory: From the Origin of Phonons to the Origin of Photons and Electrons; Oxford Univ. Press, 2004.

- Bhattacharjee, S.M.; Mahan, M.J.; Bandyopadhyay, A., Eds. Topology and Condensed Matter Physics; Vol. 19, Texts and Readings in Physical Sciences, Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017.

- Hansson, T.H.; Hermanns, M.; Simon, S.H.; Viefers, S.F. Quantum Hall physics: Hierarchies and conformal field theory techniques. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabl, F. Quantum Mechanics, 4th ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nolting, W.; Brewer, W.D. Fundamentals of Many-body Physics; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S. Topological Phases in Condensed Matter Physics; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Burmistrov, S.N. Statistical and Condensed Matter Physics; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, T. Statistical Mechanics of Superconductivity; Graduate Texts in Physics, Springer Japan: Tokyo, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Piazza, R. Statistical Physics: A Prelude and Fugue for Engineers; UNITEXT for Physics, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Laskin, N. Fractional Quantum Mechanics. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.Z.; Kane, C.L. Colloquium: Topological Insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 3045–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, M.G.G.; DeWitt, C.M. Feynman functional integrals for systems of indistinguishable particles. Phys. Rev. D 1971, 3, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J.; Schroeter, D.F. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yakaboylu, E.; Lemeshko, M. Anyonic statistics of quantum impurities in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 045402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, S. Quantum mechanics and field theory with fractional spin and statistics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1992, 64, 193–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.A.; Lawler, M.J.; Vishveshwara, S.; Fradkin, E. Measuring fractional charge and statistics in fractional quantum Hall fluids through noise experiments. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 155324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S. Multiparticle quantum mechanics obeying fractional statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 53, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Space-time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1948, 20, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, L. A path integral for spin. Phys. Rev. 1968, 176, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canright, G.S.; Girvin, S.M. Fractional Statistics: Quantum Possibilities in Two Dimensions. Science 1990, 247, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiter, M.; Wilczek, F. Fractional statistics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2024, 15, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Search for non-Abelian Majorana braiding statistics in superconductors. SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Rossi, R.; Vicentini, F.; Carrasquilla, J.; Georges, A.; et al. Variational benchmarks for quantum many-body problems. Science 2024, 386, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamon, C.D.C.; Freed, D.E.; Kivelson, S.A.; Sondhi, S.L.; Wen, X.G. Two point-contact interferometer for quantum Hall systems. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, A. Superconducting analogue of the parafermion fractional quantum hall states. Phys. Rev. X 2014, 4, 031009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Liang, S.; Gardner, G.C.; Manfra, M.J. Fabry-Pérot Interferometry at the ν=2/5 Fractional Quantum Hall State. Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13, 041012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.L.; Zhang, S.C. Topological Insulators and Superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicea, J. New directions in the pursuit of Majorana fermions in solid state systems. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2012, 75, 076501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Random-Matrix Theory of Majorana Fermions and Topological Superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015, 87, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pientka, F.; Keselman, A.; Berg, E.; Yacoby, A.; Stern, A.; Halperin, B.I. Topological Superconductivity in a Planar Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 021032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotetes, P. Classification of engineered topological superconductors. New J. Phys. 2013, 15, 105027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.C. Quantum Theory of Atomic Structure; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Troyer, M.; Wiese, U.J. Computational complexity and fundamental limitations to fermionic quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 170201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleo, G.; Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science 2017, 355, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correggi, M.; Duboscq, R.; Lundholm, D.; Rougerie, N. Vortex patterns in the almost-bosonic anyon gas. EPL 2019, 126, 20005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, D.; Seiringer, R. Fermionic behavior of ideal anyons. Lett. Math. Phys. 2018, 108, 2523–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardot, T. Average field approximation for almost bosonic anyons in a magnetic field. J. Math. Phys. 2020, 61, 071901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardot, T.; Rougerie, N. Semiclassical Limit for Almost Fermionic Anyons. Commun. Math. Phys. 2021, 387, 427–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correggi, M.; Fermi, D. Magnetic perturbations of anyonic and Aharonov-Bohm Schrödinger operators. J. Math. Phys. 2021, 62, 032101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de las Heras, A.; Macaluso, E.; Carusotto, I. Anyonic Molecules in Atomic Fractional Quantum Hall Liquids: A Quantitative Probe of Fractional Charge and Anyonic Statistics. Phys. Rev. X 2020, 10, 041058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti-Rojas, G.; Westerberg, N.; Öhberg, P. Synthetic flux attachment. Phys. Rev. Research 2020, 2, 033453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakaboylu, E.; Ghazaryan, A.; Lundholm, D.; Rengerie, N.; Lemeshko, M.; Seiringer, R. Quantum impurity model for anyons. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 102, 144109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougerie, N.; Yang, Q. Anyons in a tight wave-guide and the Tonks-Girardeau gas. SciPost Physics Core 2023, 6, 079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Murthy, G.; Rao, S.; Jain, J.K. Kohn-Sham density functional theory of Abelian anyons. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 035124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, D.; Rougerie, N. Emergence of Fractional Statistics for Tracer Particles in a Laughlin Liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 170401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | Fermions | Bosons |

|---|---|---|

| Relative phase | ||

| Exchange phase | ||

| Total phase operator | ||

| Spatial phase operator | ||

| Spin phase operator | ||

| Spatial wave function | ||

| Spin wave function | ||

| Relationship between and | ||

| Relationship between and | ||

| Relationship between and |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).