1. Introduction

The indistinguishability of identical particles plays a crucial role in the development of both statistical thermodynamics and quantum mechanics. In thermodynamics, it provided a solution to the Gibbs paradox [

1,

2], although some argue that the paradox could be resolved without invoking the indistinguishability of identical particles [

3]. In quantum mechanics, it leads to the concepts of bosons and fermions, as well as Pauli’s exclusion principle for fermions [

4]. This paper demonstrates that the principle of indistinguishability might yield further insights: a generalized version of this principle may help capture and stabilize a massive dark matter particle, which is thought to interact only weakly with ordinary matter [

5,

6,

7].

In quantum mechanics, the indistinguishability of identical particles can be derived from a more general principle. This principle states that if an operation on quantum states at time t does not cause any physical effects or preserves all from t to , then this operation is permitted for the dynamics. Obviously, this principle is correct for .

What about when

is not infinite? It is natural to hypothesize the existence of a critical time scale

such that when

, the above principle still holds. We can then define temporarily identical particles as those particles whose interchange would not cause any observable physical effects during a time span

, with

. In

Section 3, it will be shown that

is roughly determined by the lowest energy level of the eigenstate of one of these temporarily identical particles or systems. In this paper, we formulate the Indistinguishability Hypothesis for Temporarily Identical Particles (IHTIP) in terms of quantum mechanics and discuss its potential theoretical consequences. Specifically, it will be demonstrated that an elementary particle with extraordinarily large internal freedom, deeply entangled with the environment, can be temporarily identical to a collection of particles forming a pure entangled state. According to the hypothesis, these two systems will interchange with a certain probability, implying that the deeply entangled particle can be disentangled from the environment and become temporarily pure. Based on this analysis, we predict that a class of dark matter particles, such as Wimpzillas [

6,

7,

8,

9], can be captured using this strategy. If this prediction is confirmed by experiments in the future, it will pave a new avenue for detecting elementary particles.

Before formulating the indistinguishability hypothesis for temporarily identical particles, we would like to discuss its philosophical basis. In philosophy, the indistinguishability of identical particles can be understood through Russell’s argument [

10] about physics, which states that physics concerns itself only with the relations between systems, rather than the intrinsic nature of the systems themselves. In the language of quantum mechanics, only information that specifies the relations between systems, such as entanglement entropy, is considered physical. The exact nature of the state or wave function is less important. Therefore, any operation that preserves these relations, such as particle interchange, should be permitted within quantum dynamics. The indistinguishability of temporarily identical particles further postulates that even if an operation preserves these relations only for a finite time interval

, the operation is still allowed by the dynamics. At first glance, this postulation might seem trivial, but it introduces numerous new possibilities for quantum mechanics. Many people may think that particles are identical because they share the same intrinsic properties. However, defining identical particles this way is less precise and not practical. This paper will show that this broader definition of indistinguishability leads to significant theoretical consequences and potential applications in understanding and detecting particles, such as dark matter.

2. Indistinguishability of Identical Particles

In quantum mechanics, the indistinguishability of identical particles can be roughly formulated as follows (another formulation can be found in Ref. [

4]). If our universe can be properly described by quantum states in a finite Hilbert space (the validity of which is discussed in the discussion section), then any two particles with the same internal freedom can be shown to be identical. We assume that by a singular value decomposition [

11], the state of two systems or two particles

A and

B with the same degree of freedom can be expressed as (including the environment):

where

E denotes the environment. Note that only the first two leading terms are presented.

Now we interchange the systems

A and

B, and the above expression changes to:

Obviously, exchanging systems A and B would not cause any physical difference for all t, since all physical information contained in the density matrices remains unchanged. We emphasize that what the states and really correspond to is not important for physics. Note that the sign problems of coefficients in the above equations and the differences between fermions and bosons have not been discussed in this paper.

3. Indistinguishability of Temporarily Identical Particles

Before considering temporarily identical particles, let’s briefly review the conditions under which particles can be observed in terms of quantum mechanics. If an elementary particle is always deeply entangled with the environment, it will be difficult to observe directly, as the information about the particle is distributed across the environment. This situation corresponds to the dark matter particle

D discussed later. Conversely, if an elementary particle is always in a pure state, isolated from the environment, it may also be challenging to observe, since there is no entanglement entropy and limited interaction with the environment. In practice, we detect elementary particles during their transitions between entangled and relatively pure states. For example, in decoherence theory [

12], a studied system first loses interference and transitions from a pure state to an entangled state with the environment. The total wave function then collapses to one of the einselected eigenstates, representing a transition from an entangled to a pure state. Note that the mechanism of wave function collapse is not explained by decoherence theory [

12], but is typically addressed by the measurement postulate in quantum mechanics.

Now, we introduce another scenario. There are two entities in the scene: (1) an elementary particle D with an extremely large internal freedom P that has a singular value decomposition with m (a small integer) vanishing terms, and (2) an almost isolated (pure) system S with total internal freedom . It is assumed that the particle D is deeply entangled with the environment and is very difficult to observe; therefore, there are no significant leading terms in its singular value decomposition, and each term has only a small contribution since P is large.

If we take Zurek’s counter system [

13] in the derivation of Born’s rule seriously, then it is possible that some of the terms will become physically negligible during a short time period

(see Appendix B). The isolated system might be composed of

particles, each with a degree of freedom of

p, and therefore,

. By separating the pure state of

S from

W and performing a singular value decomposition on the rest,

can be expressed as

Assuming that this scenario can be maintained for a period longer than

, the

m vanishing terms remain very close to zero during this period, or their moduli are smaller than

, where

is the dimension of the maximum-dimension counter system of

D (see Appendix B). Then, we can exchange

D and

S without causing any physical difference during this period, even if the systems

D and

S do not have the same degree of freedom. The point is that the effective internal freedoms of the two systems

D and

S are the same now, i.e.,

(more discussions about the degree of freedom are in the discussion section). After the interchange, the above expression can be written as

Here, we emphasize again that what and really correspond to is not important for physics, as long as exchanging them does not cause any observable physical effects. Actually, during the time interval , the world is in a superpositional state of the above two states, i.e., . It can be shown that if the system S is not pure, S and D would not be temporarily identical (see Appendix C).

Even though right after the exchange it seems that there is no difference, the isolated composite system suddenly becomes an elementary particle. Over time, the

m vanishing terms will gradually come into play. The dynamics of the elementary particle thereafter can be described by the equation

where

ℏ is set to 1, and

with

and

being the energy levels of

D and

S before the interchange (see Appendix A for detailed derivation). Eventually, this elementary particle will become deeply entangled with the environment due to its large internal degree of freedom and will likely never be detected again. Physically, we will observe the particles that make up the composite system gradually disappear. Unlike the interchange of two identical particles, this process is not time-symmetric in nature.

At the end of this section, I would like to show that roughly depends on the lowest energy level of the eigenstates of . For some instance, the actual dimension of the state is only one in the eyes of the system D. It might seem that it should be temporarily identical to a quantum system with a degree of freedom of one, but this is not the case because the state will rotate away in the dimensional Hilbert space at the next moment. Thus, should be the time span proportional to the time it takes for the state to explore the entire dimensional space. While we cannot precisely determine , it should be proportional to , where is the lowest energy of the eigenstates of . It might also be related to the Planck time . If the m vanishing terms of the SVD of D remain nearly zero for , the actual dimension of ’sensed’ by the system D would not change anymore, and these two systems can then be temporarily identical.

4. How to Detect a Dark-Matter Particle

The above discussion might already provide an easy way to detect dark-matter particles, such as Wimpzillas [

6,

8,

9]. First, prepare a series of almost isolated systems with 2, 3, 4, ...

n identical particles, each with some unknown degree of freedom

p. If

n is large enough for an appropriate

p, at least one of the numbers

,

, ...

, say

, will be very close to the degree of freedom

P of some dark-matter particle. In this case, the dark-matter particle, originally deeply entangled with the environment, can potentially be captured and localized by this composite system. Conversely, the

elementary particles are instantly moved to the locations originally occupied by the dark-matter particle. Subsequently, the dark-matter particle will gradually delocalize and become deeply entangled with the environment again. Effectively, the

elementary particles have disappeared, even though they are actually in different locations (see

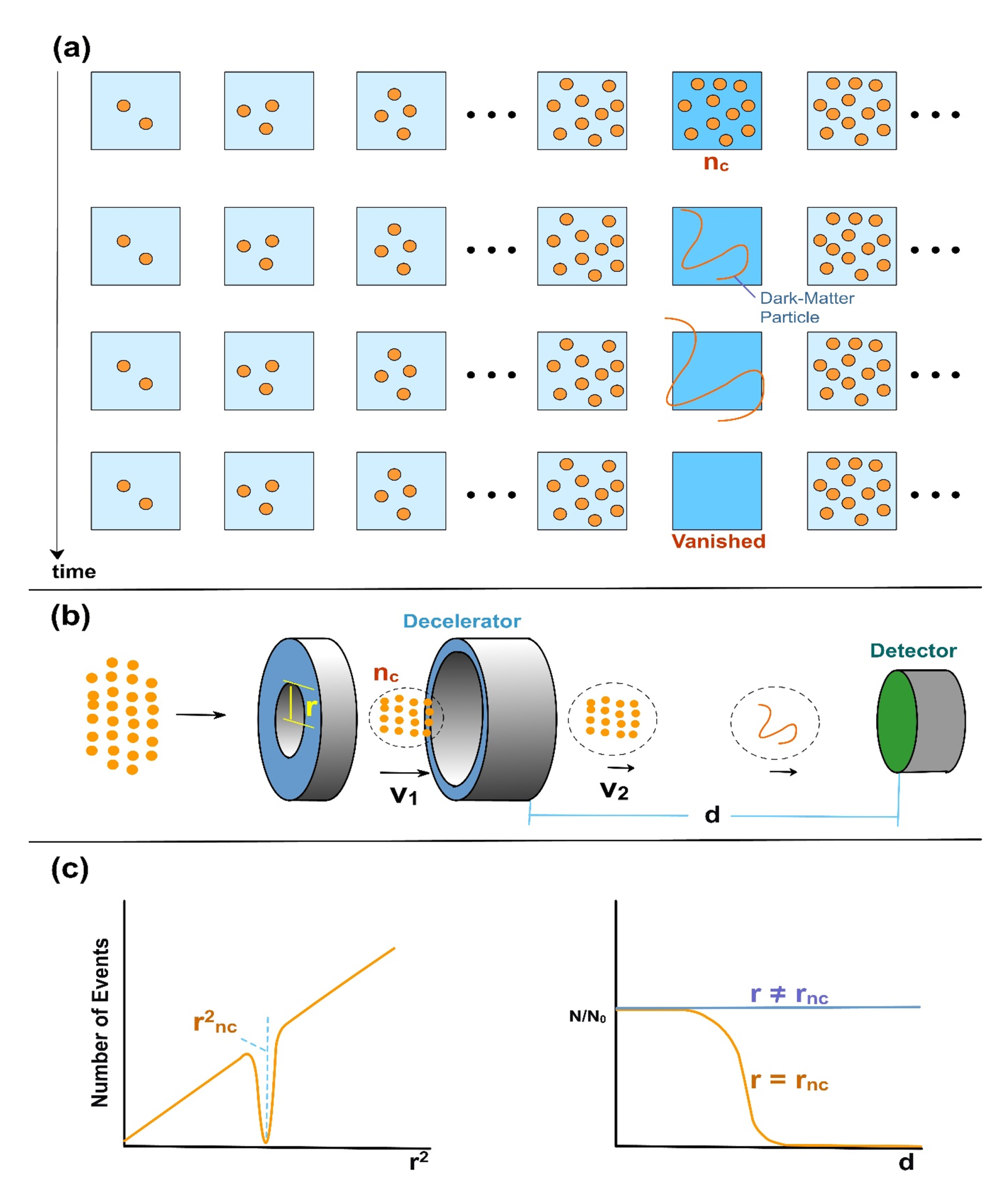

Figure 1(a)).

Finding

(or equivalently

P) is similar to finding a Mersenne prime [

14] in number theory, where a Mersenne prime is defined as a prime number close to (one less than) a power of 2 (a similar idea is also discussed in ref. [

15]). Similarly,

P, the degree of internal freedom of a dark-matter particle, should be a special type of integer (not necessarily a prime) close to a power of

p. However, it is expected to be much more challenging to find

for the following reasons: (i) one must first identify the correct

p or type of particles; otherwise,

may not exist at all; (ii) it is extremely difficult to isolate particles in experiments, even though techniques developed in quantum computing [

16] can be directly used to isolate a number of elementary particles; and (iii) it is also challenging to distinguish between the phenomenon of decoherence and the disappearance of a number of particles. The requirement for

P to be a special type of integer reminds us of the requirement for elementary particles in quantum field theory to transform under irreducible unitary representations of the Poincaré group [

17,

18]. However, they are not exactly the same, and detailed discussions are referred to in the discussion section.

A possible experiment to implement the strategy of

Figure 1(a) is suggested in

Figure 1(b) and (c). In

Figure 1(b), a bunch (pulse) of elementary particles are first accelerated to some velocity

. Some of them then pass through a hole in a shielding plate, and before hitting the detector, they are decelerated to

. By properly choosing the flux of the colliding particles and the hole size

r, the number of particles passing through the hole can be tuned to

by monitoring the number of events observed by the detector. If the Indistinguishability Hypothesis for Temporarily Identical Particles (IHTIP) is correct and

d is greater than some threshold, these

particles will turn into a dark-matter particle, and the detector will observe no event. Therefore, the dependence of the number of events

N on the hole size (or the flux) is shown in

Figure 1(c), where

for

. The possible dependence of the relative number of events

on the distance from the decelerator to the detector is also given in

Figure 1(c), but this dependence is only illustrative and cannot be explicitly worked out in this work (also see (ii) in the discussion section). Regarding parameter settings,

r is suggested to be several hundred nanometers to several microns, and

should be large enough for the particles to pass through the hole (i.e.,

).

should be chosen so that

.

5. Discussions

Several comments can be made about the present work:

(i) The interchange of identical particles is obviously a time-symmetric operation, while the interchange of temporarily identical particles is not time-symmetric. This might be responsible for the time-asymmetric nature of wave-function collapse. However, it does not imply that the indistinguishability of temporarily identical particles alone can solve the measurement problem, as the interchange rule of temporarily identical particles is still unknown. Furthermore, a complete solution to the measurement problem might still need to explicitly include the observer in the theory. In the future, a complete quantum dynamics might be depicted as follows: time-symmetric dynamics dominated by unitary evolution and time-asymmetric dynamics given by the interchange operation of temporarily identical particles.

(ii) Because the interchange rule of temporarily identical particles is not determined in the current work, we have not computed the probability of dark-matter being captured by the pure entangled system. It is also not possible to determine the critical time scale . However, it is reasonable to suggest that is small since it is related to the time scale of the time-asymmetric phenomena of quantum events such as wave-function collapse. If is small, then the experiment mentioned in the previous section is not that difficult to implement. As long as the type and the number of particles are correct, and the particles happen to be totally isolated for a short time period , they can disappear by being traded for a dark-matter particle.

(iii) It should be noted that we have implicitly assumed the degree of internal freedom of an elementary particle or a dark-matter particle satisfies some condition and is finite. However, according to quantum field theory, where spacetime is assumed to be continuous, elementary particles transform under irreducible unitary representations of the Poincaré group [

17,

18]. Wigner [

17,

19] has proved that there are no such finite-dimensional unitary representations, so it seems that the indistinguishability hypothesis of temporarily identical particles cannot be correct. However, the hypothesis can still be true for three reasons. First, as suggested by loop quantum gravity [

20], spacetime might be quantized and finite as a whole, allowing every system to be spanned in a finite Hilbert space in the end. Second, Mach’s view about our universe suggests that there might be no background time and space since they could emerge as relations (such as relative distances [

21]) between different entities in the universe. Therefore, internal freedoms might be all the freedoms that an elementary particle can have and can be finite. In short, it is still controversial whether our universe can be represented by a quantum state spanned on a basis with finite dimensions. If future experiments support the predictions of this work, then it will be highly possible that our universe is finite and discrete. Third, some might argue against this possibility by claiming that in this framework, elementary particles should have a prime-number degree of freedom. However, as suggested above, the total degree of freedom of a particle is obviously a composite number expressed as

, where

is the internal freedom of the particle, and

is the freedom of the particle to store its spatial information. This problem can be solved by redefining a particle as a composite system consisting of a subsystem with the internal freedom

and another subsystem with a prime-number internal freedom

, where

. These two subsystems can stabilize each other to form an elementary particle, also by the indistinguishability principle of temporarily identical particles.

(iv) After learning about the indistinguishability of temporarily identical particles, some might wonder why macroscopic systems are stable and have not been replaced by dark-matter particles. First, macroscopic systems are extremely difficult to isolate and are almost impossible to be temporarily identical to other systems or particles. Second, if the internal freedoms of dark-matter particles are sparsely distributed in the natural number set, similar to prime numbers, it would be highly unlikely that the overall internal freedom of a macroscopic system happens to be close to that of some dark-matter particle.

6. Summary

In summary, an Indistinguishability Hypothesis for Temporarily Identical Particles (IHTIP) has been proposed and formulated, suggesting that a type of dark-matter particles with an extremely large inner freedom (such as Wimpzillas [

8,

9]) can possibly be captured and stabilized due to the indistinguishability of temporarily identical particles. This hypothesis is testable, and if proven true, it could provide a completely new strategy for studying elementary particles. Additionally, this hypothesis might offer a potential solution to the measurement problem, as it is time asymmetric in nature and does not contradict the basic principles of quantum mechanics.

We acknowledge that the formulation of IHTIP in this work is not very rigorous, primarily because it is challenging to clearly define the states of elementary particles in finite Hilbert space. Nevertheless, the proposed strategy based on this hypothesis to study dark-matter particles remains attractive to experimentalists. It offers an alternative, simple, and potentially cost-effective experimental method to detect dark matter, especially given the uncertainty surrounding the success of traditional, expensive experiments [

7].

A possible experiment based on this strategy has also been suggested. This experiment departs from the traditional philosophy of collider physics, which pursues high kinetic energy, and instead confines a specific number of particles in a very small space to produce new particles. For example, a controlled number of particles could be isolated and monitored to observe the predicted disappearance and subsequent detection of dark-matter particles. This novel approach, if successful, could significantly advance our understanding of dark matter and elementary particles.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Derivation of Eq. (6)

In the main context, we only present, without proof, the dynamical equation of the elementary particle

D after it has been interchanged with the composite-particle system. In this Appendix section, a simple proof of the dynamical equation is given. Here we recover the dynamics and rewrite eq. (3) in the main text as follow,

In the above expression, ℏ has been set to 1. Because t is assumed to be small so the Hamiltonian of W can be assumed to be approximately separable, i.e. . , and are assumed to be eigenstates of the Hamiltonian and , and denote the corresponding energy levels of these eigenstates, respectively. Actually if they are not the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian, one can always re-express them in terms of the eigenstates.

Now we interchange

S and

D, eq. (8)becomes

where

.

On the other hand, the above equation can be re-derived by evolving the state

for a time span

t as follow,

Note that for small

t,

and Hamiltonian not only depends on the type of particle but also depends on its surrounding environment. Because the environments for

S,

E and

D have been slightly changed after interchange of

S and

D so

,

and

,

might be different from those before interchange. Further, it is not guaranteed that

are the eigenstates of

anymore. But for

D, we can still assume that

are eigenstates to see if the story can be consistent in the end. By letting eq. (9) be equal to eq. (10) and focusing on the last square bracket, we have

and therefore

When

t is small, the above equation is reduced to

Actually, this equation determines dynamics of the elementary particle D after the exchange (also see eqs. (5) and (6) in the main context). It seems that the elementary particle D would be more energetic thereafter because for each energy level .

As for the first bracket of eq. (10), because S is deeply entangled with E and are not necessarily eigenstates of , so it is difficult to work out as functions of .

Appendix B. Effective Dimension of a Quantum State in a Finite-Hilbert-Space Universe

Consider a system

D with an extremely large inner freedom

P in a finite-Hilbert-Space (FHS) universe

that can be singular-value decomposed as,

where

E denotes the environment. If Zurek W H’s derivation of Born’s rule is correct [

13], then it can be shown that the effective dimension of

D can be smaller than

P for a short time and it is viable.

In his beautiful derivation [

13], Zuek W H employed a `counter’ system

M as technical tool and this work will takes this system seriously. Because the dimension of the universe

W in this work is assumed to be finite, so the dimension of all counterweight systems

has to be also finite. We can assume that among these systems that can be made to measure the properties of system

D, the counter system

has the maximum freedom

.

However, according to Zurek W H’s work [

13], the probabilities of a state measured by this counter system can only be

with

k an integer (

). Therefore, for all

in eq. (

A6) that are smaller than

they can be effectively seen as being vanished or the counter system

cannot detect them. If there are

m such

’s then the effective dimension of the system

D can be reduced to

.

Appendix C. Why the Composite-Particle System Has to be Pure

If the system

S is not pure or not relatively pure, then one will quickly find that

S and

D are not temporarily identical anymore. Now

can be expressed as

From the above expression, it is highly impossible that S and D can be interchanged, since the effective inner freedom of D is now bigger than that of S. The point is that all , ... ... can be hardly expressed as linear combinations of orthogonal state vectors , ... , which implies that the effective inner freedom of D should be bigger than . As a matter of fact, it is not difficult to show that as long as at least one of the two systems is isolated and the two systems have the same effective inner freedoms, then these two systems can be seen as two temporarily identical particles.

References

- Gibbs, J.W. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics; Dover Publications Inc.: New York, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Landé, A. New Foundations of Quantum Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Versteegh, M.A.M.; Dieks, D. The conceptual basis of quantum field theory. Am. J. Phys. 2011, 79, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinaas, J.M.; Myrheim, J. On the theory of identical particles. IL Nuovo Cimento B 1977, 37, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungman, G., K. M.; Griest, K. Supersymmetric dark matter. IL Nuovo Cimento B 1977, 37, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bertone, G., H. D.; Silk, F. Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints. Phys. Rept. 2005, 405, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undagoitia, T.M.; Rauch, L. Dark matter direct-detection experiments. J. Phys. G 2016, 43, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, E. W. D. In J.; Riotto, A. Wimpzillas. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Dark Matter in Astro and Particle Physics, [hep-ph/9810361]. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S., C. C.; Faraggi, A.E. Moduli space of heterotic strings with H-fluxes. Nucl. Phys. B 1996, 477, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B. The Analysis of Matter; Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner &, Ed.; Co. Ltd.: London, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- More precisely, it is just a tensor decomposition. Actually, the formulation of the indistinguishable principle of identical particle does not rely on the tensor decomposition. We express the principle in this way in order to make a relatively smooth transition to the formulation for temporarily identical particle.

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Environment-induced superselection rules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanks, D. Solved and unsolved problems in number theory. Vol. I; Spartan Books: Washington D.C, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.F. The Silence of Art; Social Sciences Academic Press (China): Beijing, 2018. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- DiVincenzo, D.P. Quantum Computation. Science 1995, 270, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields. Volume 1: Foundation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.D. Quantum Field Theory and the Standard Model; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wigner, E.P. On unitary representations of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group. Ann. Math. 1939, 40, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background independent quantum gravity: A status report. Class. Quant. Grav. 2004, 21, R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J. The timelessness of quantum gravity. Nature 1974, 249, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).