1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder that impacts approximately 0.3–0.7% of people during their lifetime, corresponding to about 21 million individuals worldwide [

1]. Age-adjusted prevalence has remained relatively stable, but incidence rates have risen modestly over recent decades, with more new diagnoses per year [

2]. Schizophrenia is characterized by hallucinations, delusions, cognitive deficits, and social withdrawal [

3]. Environmental factors such as maternal stress and especially adolescent cannabis use may contribute to a person’s likelihood of getting schizophrenia. However, twin, family, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) firmly establish genetics as the central risk component, with genetic factors explaining approximately 80% [

4] of the risk for schizophrenia. GWAS have identified 287 genetic variants and 120 genes linked to schizophrenia. Interestingly, of the 287 genome-wide significant risk loci, only 106 are in protein-coding genes [

5,

6]. These findings highlight the importance of regulatory processes and noncoding RNAs as a risk factor for schizophrenia.

In addition, schizophrenia is widely considered a neurodevelopmental disorder, with symptoms typically emerging in adolescence or early adulthood. Converging evidence suggests that genetic risk factors act, in part, by altering neurodevelopmental trajectories: large-scale transcriptomic studies show that schizophrenia-associated genes are preferentially expressed prenatally and during adolescence, when synaptic pruning and cortical maturation occur [

7]. This framework emphasizes the importance of evaluating potential risk genes across developmental stages and brain regions.

Schizophrenia is consistently linked to structural and functional abnormalities across brain regions. Meta-analyses and longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies reveal reduced gray matter volumes and altered connectivity in areas including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, superior temporal cortex, thalamus, and anterior cingulate cortex [

8]. These structures are critical for cognition, memory, and emotional regulation, and their dysfunction highlights schizophrenia’s characterization as a dysconnection syndrome, defined by disrupted cognition and impaired high-order neural integration.

The 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) system has been consistently implicated in the pathology of schizophrenia, especially through its involvement in mood, cognition, and sensory processing [

9]. The serotonin receptor family (HTR, 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor) consists of seven main classes from

HTR1A to

HTR7 and 14 subtypes. Antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia primarily target dopamine receptors [

10], although many have also been shown to act on serotonin receptors [

11], particularly

HTR1A and

HTR2A. Interestingly, variants in

HTR2A,

HTR1A,

HTR2C, and

HTR3A have been implicated in schizophrenia [

12].

By contrast,

HTR5A is far less studied despite its clear physiological relevance.

HTR5A encodes the serotonin 5-HT5A receptor, a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that inhibits adenylate cyclase and modulates cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling [

13].

HTR5A is highly expressed in the cortex and hippocampus [

13], areas that are consistently disrupted in schizophrenia. Nevertheless, unlike

HTR2A and

HTR1A, which are highly characterized,

HTR5A’s role in psychiatric disease remains largely unexplored. This gap makes it especially intriguing to investigate

HTR5A as a potential contributor to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [

14].

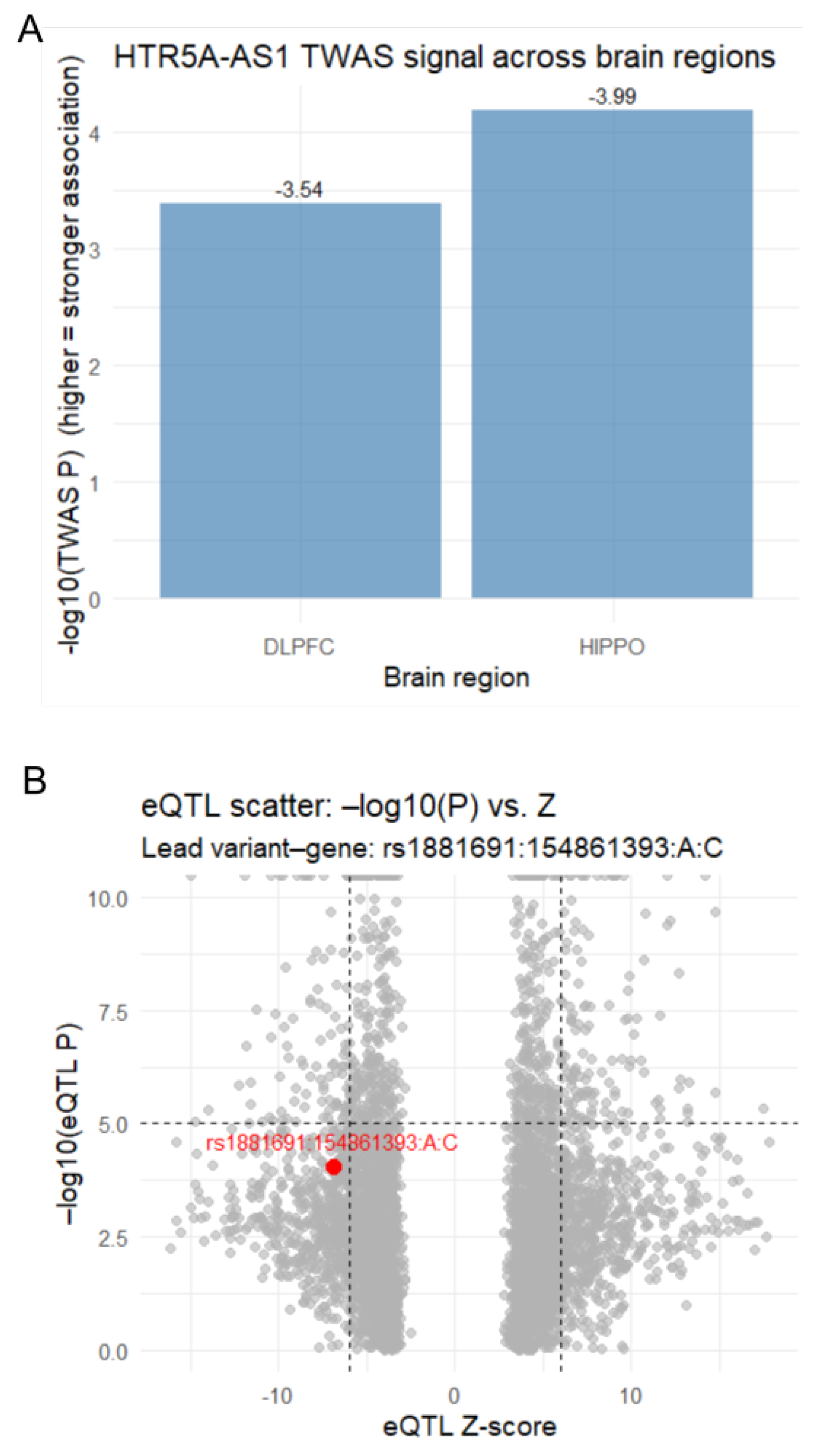

Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) present a means of addressing gene-disease associations by integrating GWAS summary statistics with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data to score a gene based on an association between its predicted expression and a trait [

15]. A recent TWAS study identified the expression of a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) transcribed antisense to

HTR5A,

HTR5A-AS1, to be significantly associated with schizophrenia risk [

16]. Collado-Torres et al. profiled 900 postmortem brain tissue samples from the hippocampus (

) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC;

) from 286 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and 265 not diagnosed with schizophrenia. By integrating the most recent schizophrenia GWAS and their own eQTL results, the authors performed brain region-specific TWAS [

16] and reported over 1,140 significant associations spanning 333 genes, including two independent associations with

HTR5A-AS1: a junction-level hippocampal signal (

,

, false discovery rate [FDR]

) and an exon-level signal in the dlPFC (

,

, FDR

). The significant association of

HTR5A-AS1 in the hippocampus is linked to schizophrenia GWAS variants that are predicted to act as eQTLs regulating its expression. Nevertheless,

HTR5A-AS1 remains largely unexplored in the literature, with PubMed [

17] and GeneCards [

18] searches showing no PubMed-indexed publications explicitly mentioning it to date.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

R [

22] version 4.4.3 with the

readr [

23],

dplyr [

24],

ggplot2 [

25], and

stringr [

26] packages was used to analyze Collado-Torres et al. TWAS results, which were downloaded from

http://eqtl.brainseq.org/phase2/. The TWAS data were imported, and gene identifiers were cleaned by removing Ensembl version suffixes to allow for consistent matching across datasets. The data were then filtered to include only rows containing

HTR5A-AS1 or its Ensembl ID: ENSG00000220575. TWAS

p-values were converted to a numeric format, and the lowest

p-values across all brain regions were identified and tested to determine the most significant gene–trait association for

HTR5A-AS1. This step was performed to establish whether

HTR5A-AS1 showed robust statistical evidence for involvement in schizophrenia across the transcriptome.

2.2. Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

LD statistics were obtained using the

LDlinkR [

27] package in R, which provides programmatic access to the NIH LDlink suite [

28]. The

LDpair() function was used to calculate pairwise LD between the schizophrenia GWAS sentinel SNP (rs1583830) and the lead exon-level eQTL SNP (rs1881691). Analyses were restricted to the European (EUR) reference population from the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 under the GRCh38 genome build. LD metrics reported include

,

, and

p-values. This analysis was performed to evaluate whether the schizophrenia risk SNP and the eQTL regulating

HTR5A-AS1 are linked on the same haplotype, suggesting a shared genetic mechanism.

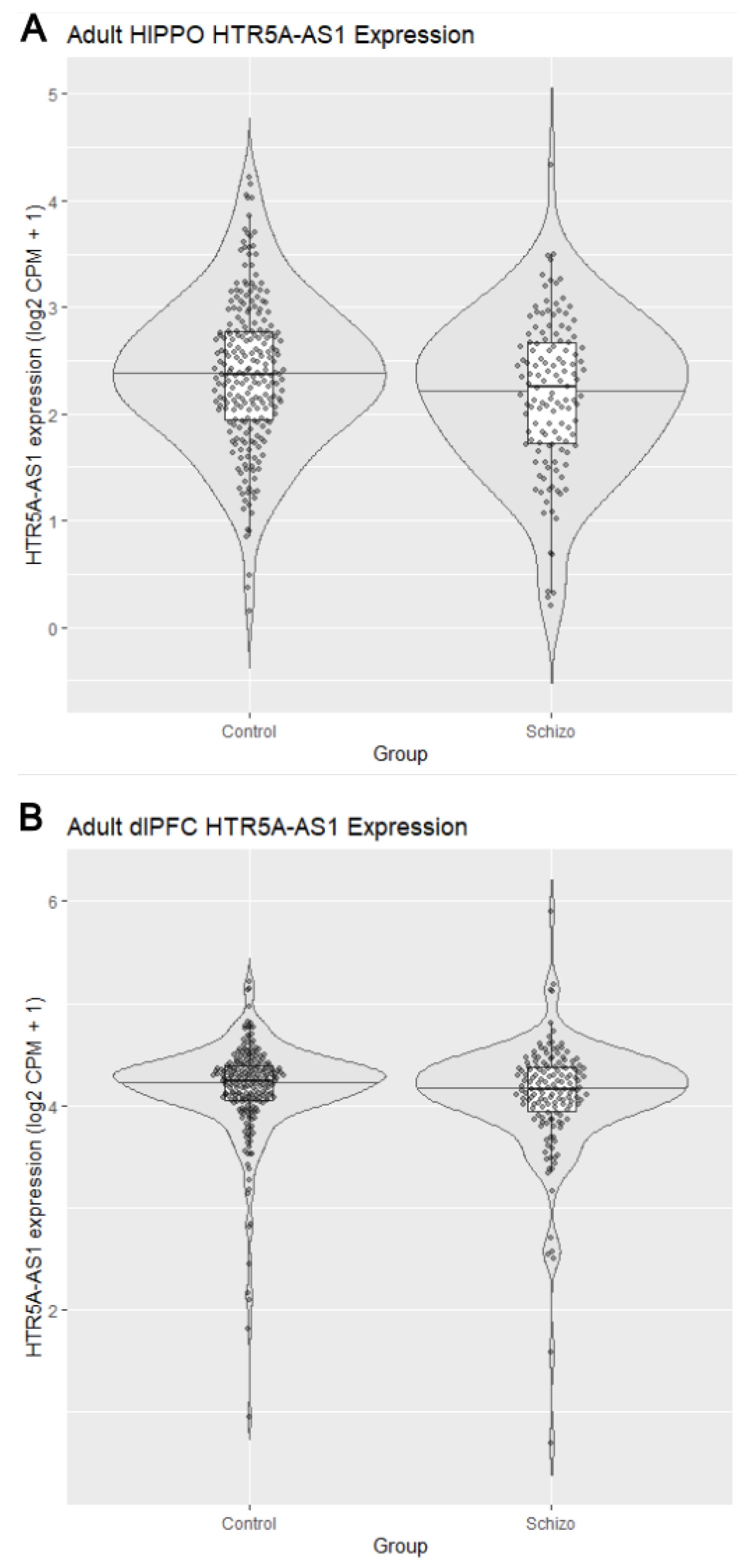

2.3. Postmortem Expression Analysis (BrainSeq)

Bulk RNA-seq expression data containing raw count data and sample metadata from postmortem brain tissue were loaded into R. The

SummarizedExperiment [

29],

dplyr,

ggplot2,

forcats [

30], and

ggbeeswarm [

31] packages were used to extract expression values for

HTR5A-AS1, which were converted to counts per million (CPM) using sample-specific library sizes. The samples were filtered to include only adult donors (at least 18 years old) from the hippocampus and dlPFC. Expression data were log

2-transformed, and group differences between control and schizophrenia samples were assessed using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. This analysis directly tested whether

HTR5A-AS1 dysregulation is present in disease-relevant cortical and limbic regions.

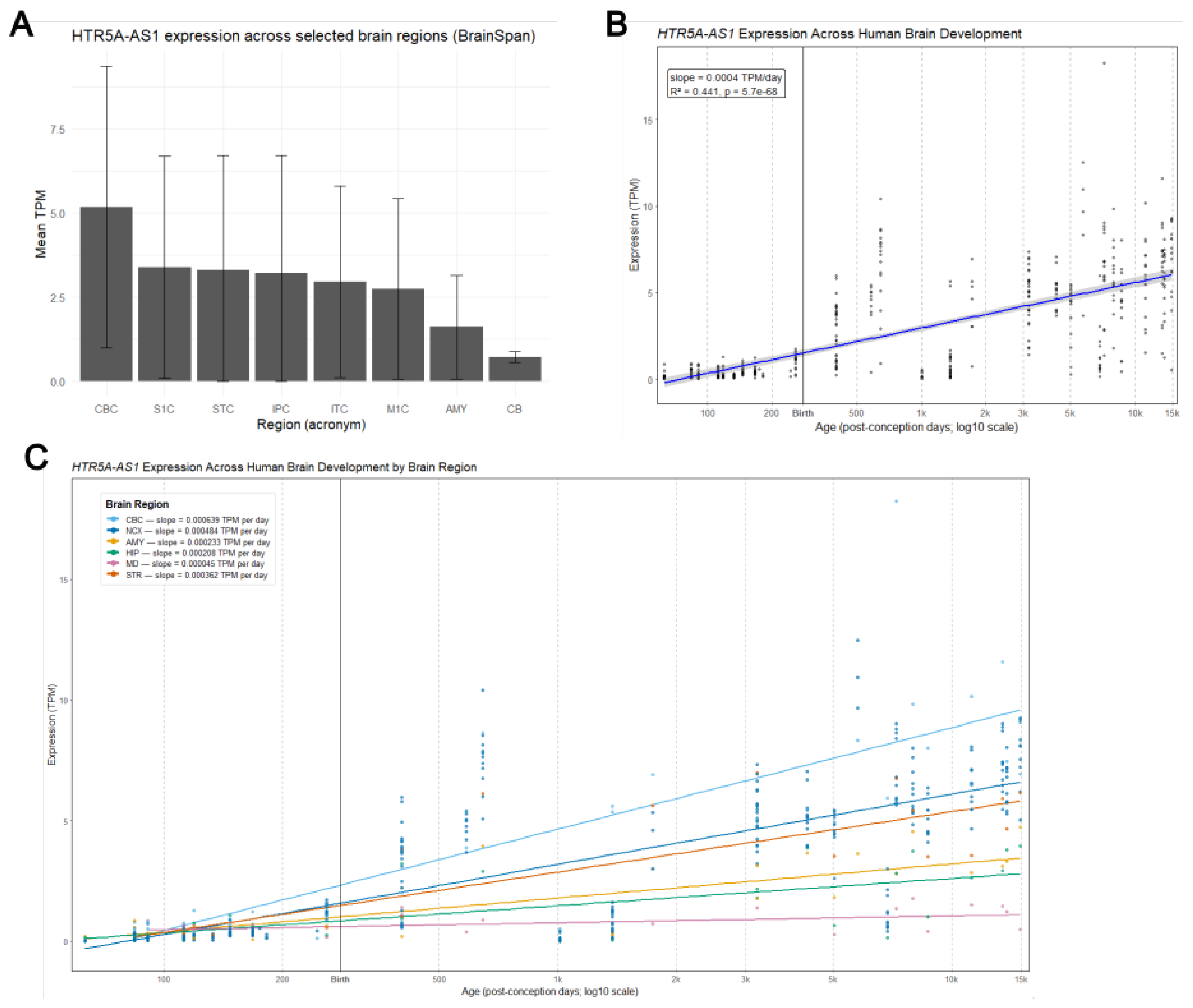

2.4. Developmental Expression Trajectories (BrainSpan)

Expression trajectories of HTR5A-AS1 were derived from BrainSpan bulk RNA-seq data. Transcript abundance values were extracted from the expression matrix using gene annotations from the accompanying metadata. Reported sample ages were parsed into post-conception days (PCD) by converting gestational weeks, months, and years into a continuous day scale, with birth defined at 280 days. Expression values were plotted against log10-scaled PCD, with vertical reference lines marking birth and selected developmental timepoints.

A linear regression model (TPM ∼ PCD) was fit to quantify the global developmental trend. The regression slope (TPM/day), coefficient of determination (

), and

p-value were calculated using the

broom [

32] package and annotated directly onto the plot. The slope serves as a quantitative measure of whether

HTR5A-AS1 expression systematically increased or decreased across human brain development.

Sample metadata were mapped from BrainSpan structure acronyms into broad anatomical classes: NCX, hippocampus, STR, MD, AMY, and CBC. Regions with the six highest median TPM values were retained for visualization. For each of the six regions, linear regression models (TPM ∼ PCD) were fit independently. Slopes (TPM change per post-conception day) were extracted using the broom package, and slope values were embedded into the figure legend for interpretability. Points were overlaid on regression lines, with a log-scaled x-axis and vertical markers at birth and selected guide marks, enabling identification of the most developmentally dynamic brain regions for HTR5A-AS1 expression.

2.5. UCSC Genome Browser Validation

The UCSC Genome Browser (hg38 assembly, accessed 2025) was used to confirm the presence and transcriptional structure of HTR5A-AS1. The locus was examined with the following tracks enabled: Base Position, database of single nucleotide polymorphisms (dbSNP) build 155 (to visualize genome-wide significant GWAS SNP rs1583830 and the lead eQTL SNP rs1881691), GENCODE v48 annotation, CLS transcript models, Adult Blood/Brain transcript models, Cell Line and Embryonic Brain transcript models, ENCODE4 long-read transcripts, and GTEx tissue expression. A PDF export of the genome browser view was generated to document transcript models and SNP placement relative to HTR5A-AS1.

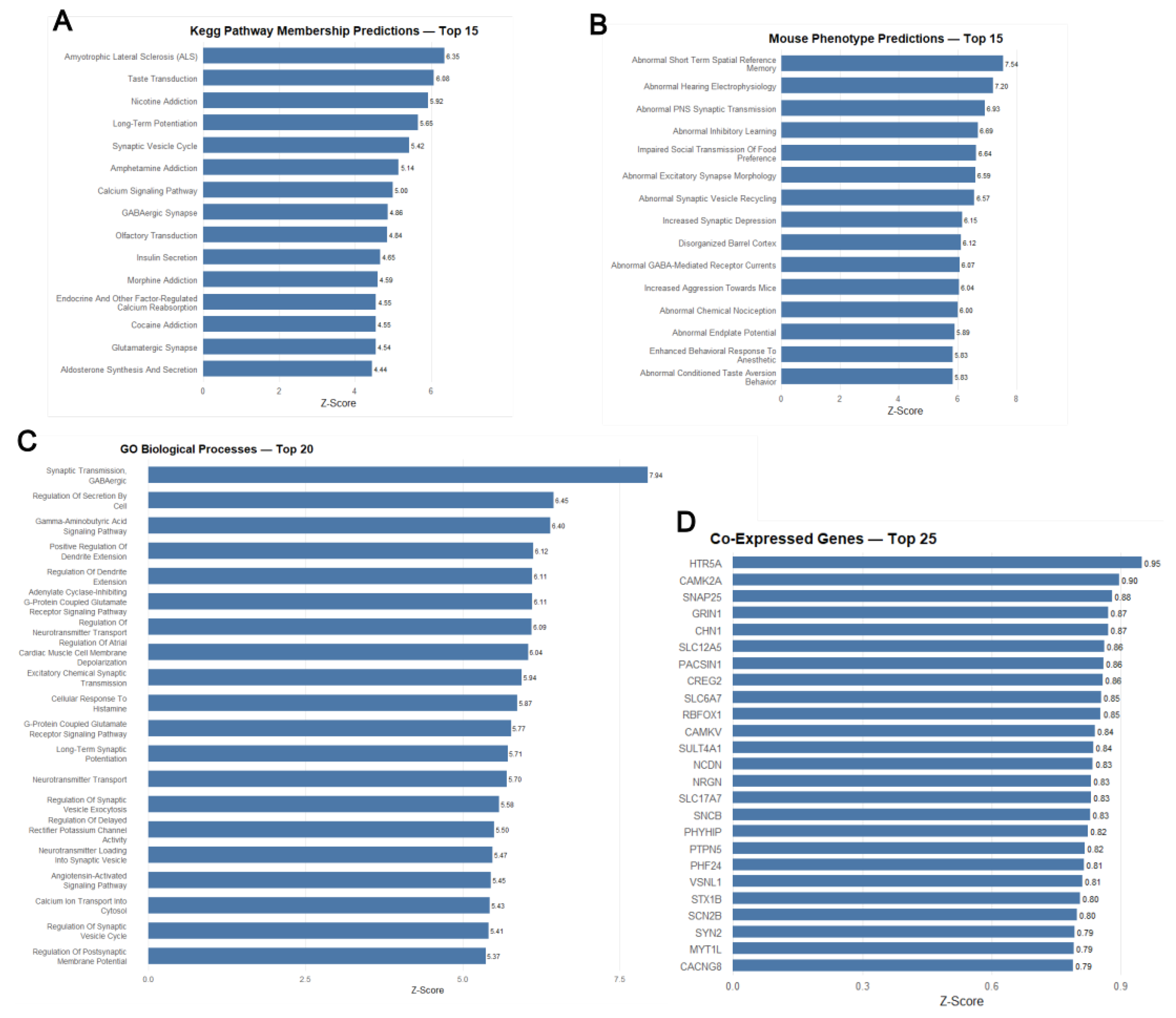

2.6. Functional Predictions (lncHUB)

Functional predictions for

HTR5A-AS1 were obtained from the lncHUB platform [

21], including Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG) pathway

Z-scores, Mammalian/MGI mouse phenotype

Z-scores, Gene Ontology (GO) biological process

Z-scores, and co-expressed gene

Z-scores. The exported result tables were read into R and processed in

dplyr; display names were wrapped for readability and converted to title case while preserving acronyms (e.g., GPCR, GABA). For each category, the top entries by

Z-score were selected without transformation (KEGG top 15; Mouse Phenotype top 15; GO Biological Process top 20; Co-expression top 25). Ranked horizontal bar charts were generated in

ggplot2, with bars representing the reported

Z-scores and numeric labels printed just beyond bar ends. Axis text was brought closer to bars to improve legibility, and figure margins were adjusted to avoid clipping of labels. No statistical re-analysis or rescaling of

Z-scores was performed; ordering and formatting were applied for visualization. All plots were produced in R (packages:

tibble [

33],

dplyr,

ggplot2,

stringr,

forcats,

rlang [

34],

grid [

35]) using fixed fill colors and identical geometries across panels to facilitate comparison.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first detailed characterization of a lncRNA transcribed antisense to the serotonin receptor gene

HTR5A,

HTR5A-AS1, in the context of schizophrenia. TWAS analyses [

16] identified two significant associations between

HTR5A-AS1 expression and schizophrenia: a junction-level signal in the hippocampus and an exon-level signal in the dlPFC. Beyond genetic associations, expression analyses revealed significantly reduced

HTR5A-AS1 expression in the hippocampus of schizophrenia brain donors, aligning with TWAS predictions [

16]. While the reduction in the dlPFC did not reach statistical significance, the trend aligns with the negative TWAS association and should be interpreted cautiously. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, which compares observed expression distributions between diagnostic groups, does not account for technical factors or genetically mediated effects. By contrast, TWAS integrates eQTL and GWAS data, making it more sensitive to genetic associations that may be obscured in bulk RNA-seq analyses. Notably, the TWAS associations were identified at the junction and exon level, suggesting that schizophrenia risk may involve altered isoform usage of

HTR5A-AS1. Such splicing-dependent effects would be diluted in bulk gene-level differential expression analyses, underscoring the need for isoform-aware approaches.

Using BrainSpan data [

19], analyses revealed that

HTR5A-AS1 is developmentally regulated, with distinct region-specific trajectories. Consistent with schizophrenia’s developmental origins,

HTR5A-AS1 displayed steep increases in expression in the cerebellar cortex (CBC) and neocortex (NCX), moderate increases in the hippocampus and amygdala, and relative stability in the thalamus. These trajectories suggest that

HTR5A-AS1 may contribute to the maturation of cortical–cerebellar and cortico-limbic circuits, which are strongly implicated in schizophrenia’s cognitive and affective dysfunction. Thus, the developmental regulation of

HTR5A-AS1 aligns it with the temporal and regional vulnerability windows most relevant to schizophrenia risk.

The possibility that

HTR5A-AS1 is simply transcriptional noise arising from

HTR5A was also refuted. This study provides multiple independent lines of evidence to validate the transcript’s authenticity: multi-exonic structure validated by long-read RNA-seq, consistent annotation in GENCODE, and strong independent expression signals across multiple datasets [

20]. Its co-expression with

HTR5A is expected for antisense pairs but does not negate potential regulatory function. Instead, it raises the possibility of cis-regulation of

HTR5A, as well as coordinated involvement in common pathways.

Functional predictions and co-expression analyses consistently implicated synaptic and cognitive processes, particularly GABAergic signaling and long-term potentiation [

21]. These findings align with the developmental regulation and cortical–hippocampal enrichment of

HTR5A-AS1, regions in which disruptions of inhibitory–excitatory balance are strongly implicated in schizophrenia. Together, these results suggest that

HTR5A-AS1 may modulate neuronal excitability or plasticity, potentially by regulating

HTR5A expression or by interacting with other synaptic genes such as

CAMK2A,

SNAP25, and

GRIN1.

These findings support a model in which HTR5A-AS1 plays a role in shaping typical brain development and synaptic function. Its developmental trajectory suggests a role in tuning serotonergic and inhibitory circuits during adolescence, consistent with the developmental onset of schizophrenia. In pathology, reduced hippocampal expression of HTR5A-AS1, coupled with its genetic associations, raises the possibility that its dysregulation contributes to schizophrenia disease risk by disrupting serotonergic signaling, inhibitory balance, or developmental trajectories in vulnerable brain regions.

There are several implications to be acknowledged. First, most predicted associations obtained from lncHUB are correlative based on co-expression, and functional experiments are required to establish their causality [

21]. Second,

HTR5A-AS1’s high co-expression with

HTR5A complicates interpretation, as distinguishing cis (local effects on the paired sense transcript) from trans (distal effects on other genes) effects will require CRISPR-mediated perturbation, allele-specific expression assays, or other targeted experiments. Third, sample sizes, while larger than prior work, are still few relative to the polygenic architecture of schizophrenia, and expression variability across cell types is obscured in bulk tissue. Future work should emphasize single-cell and spatial transcriptomic profiling to define cellular specificity, along with experimental manipulations in neuronal models to test regulatory effects on

HTR5A and synaptic physiology.