Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

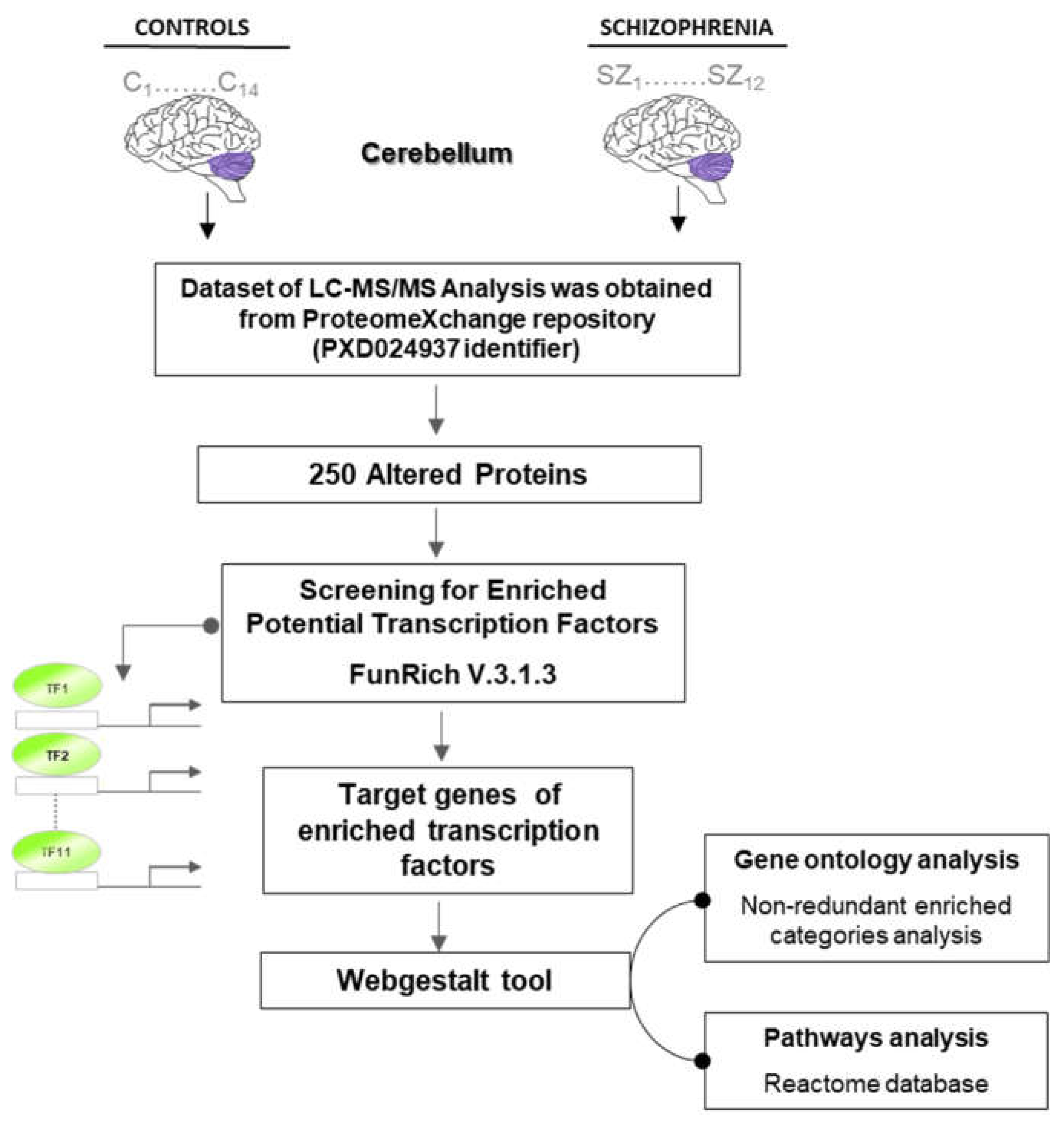

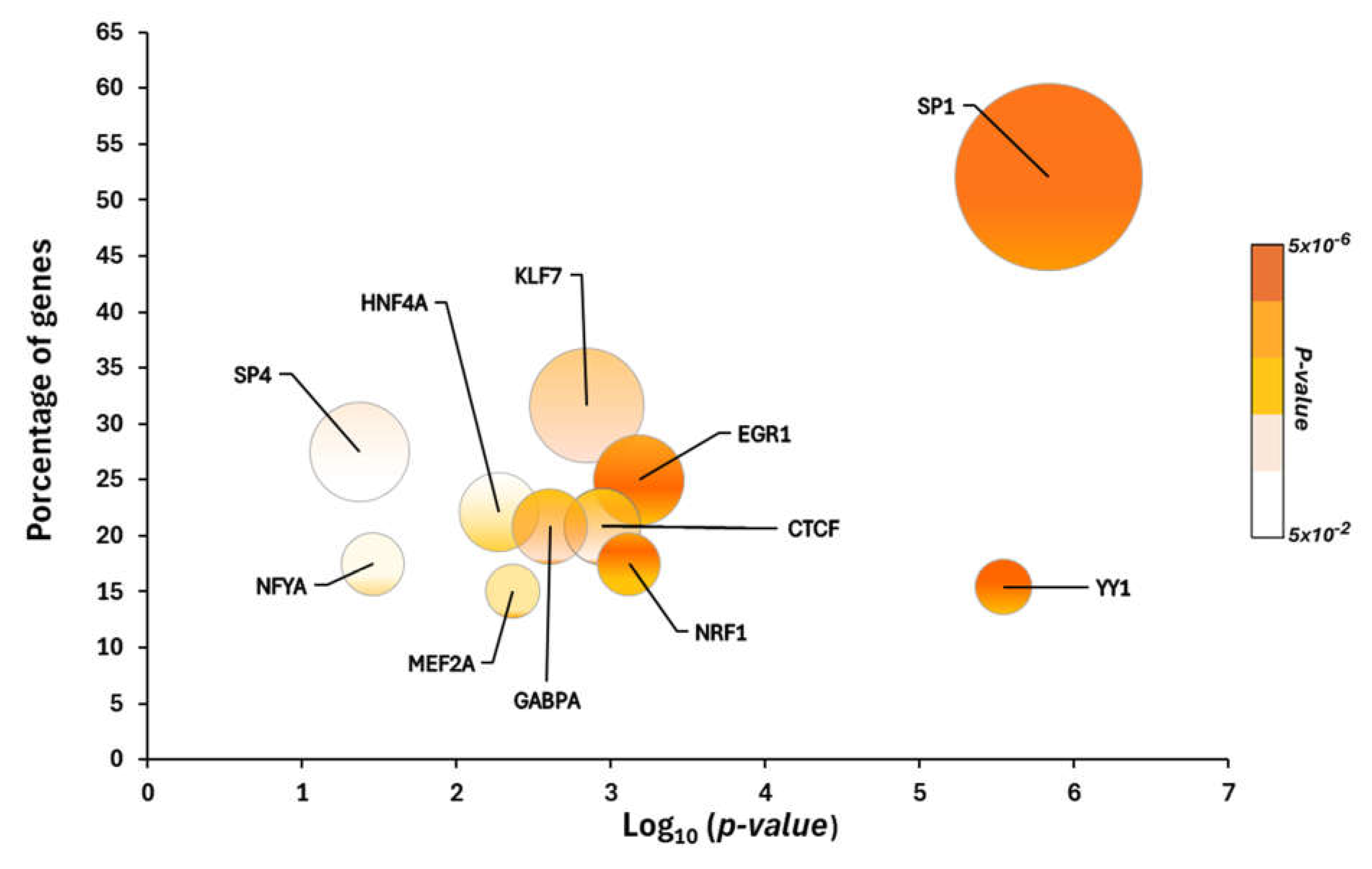

2.1. Putative Transcriptional Programs Responsible of Changes in the Proteomic Profile in the Cerebellum

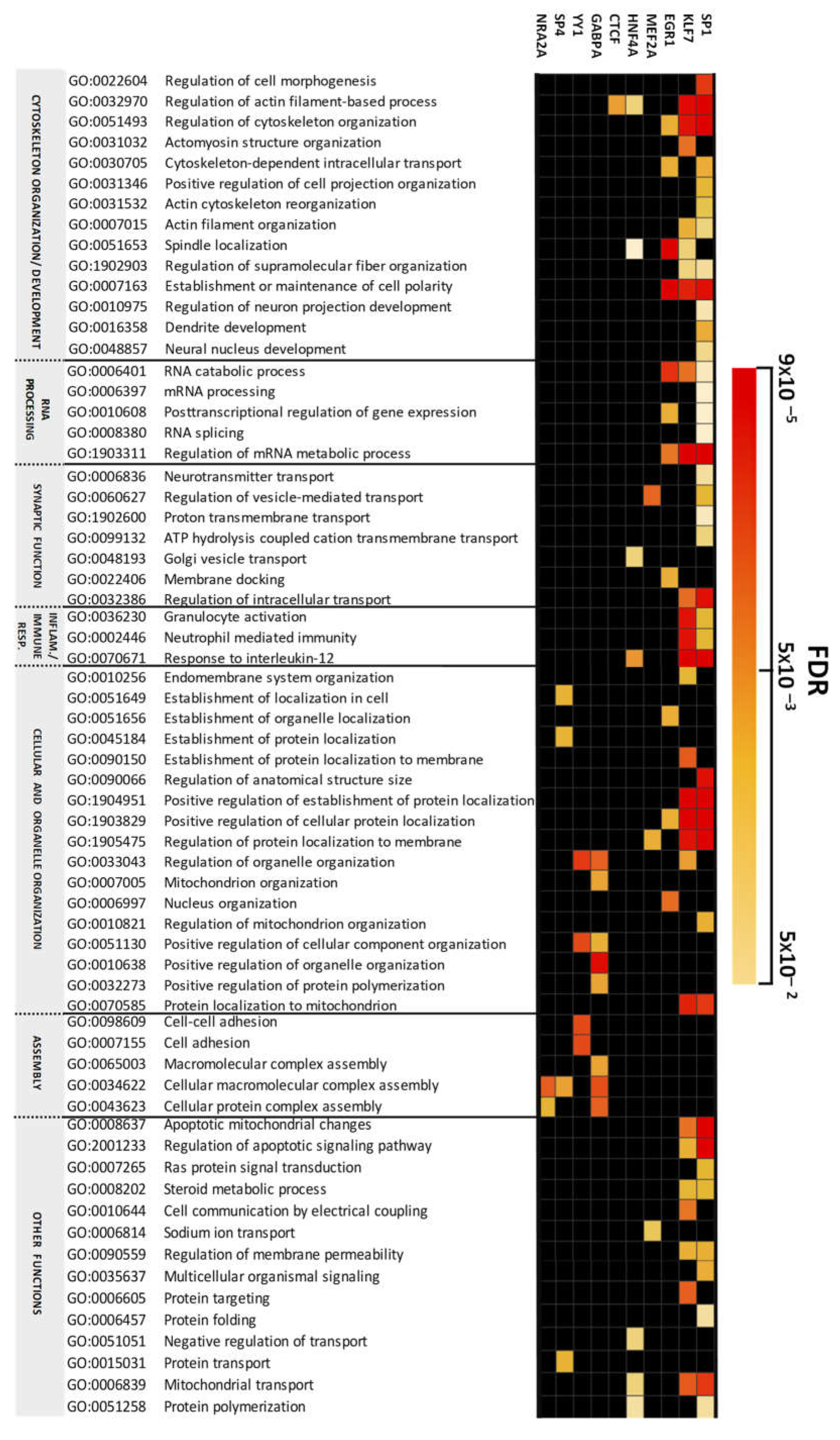

2.2. Altered Biological Processes Controlled by Transcriptional Programs in the Cerebellum in Chronic Schizophrenia

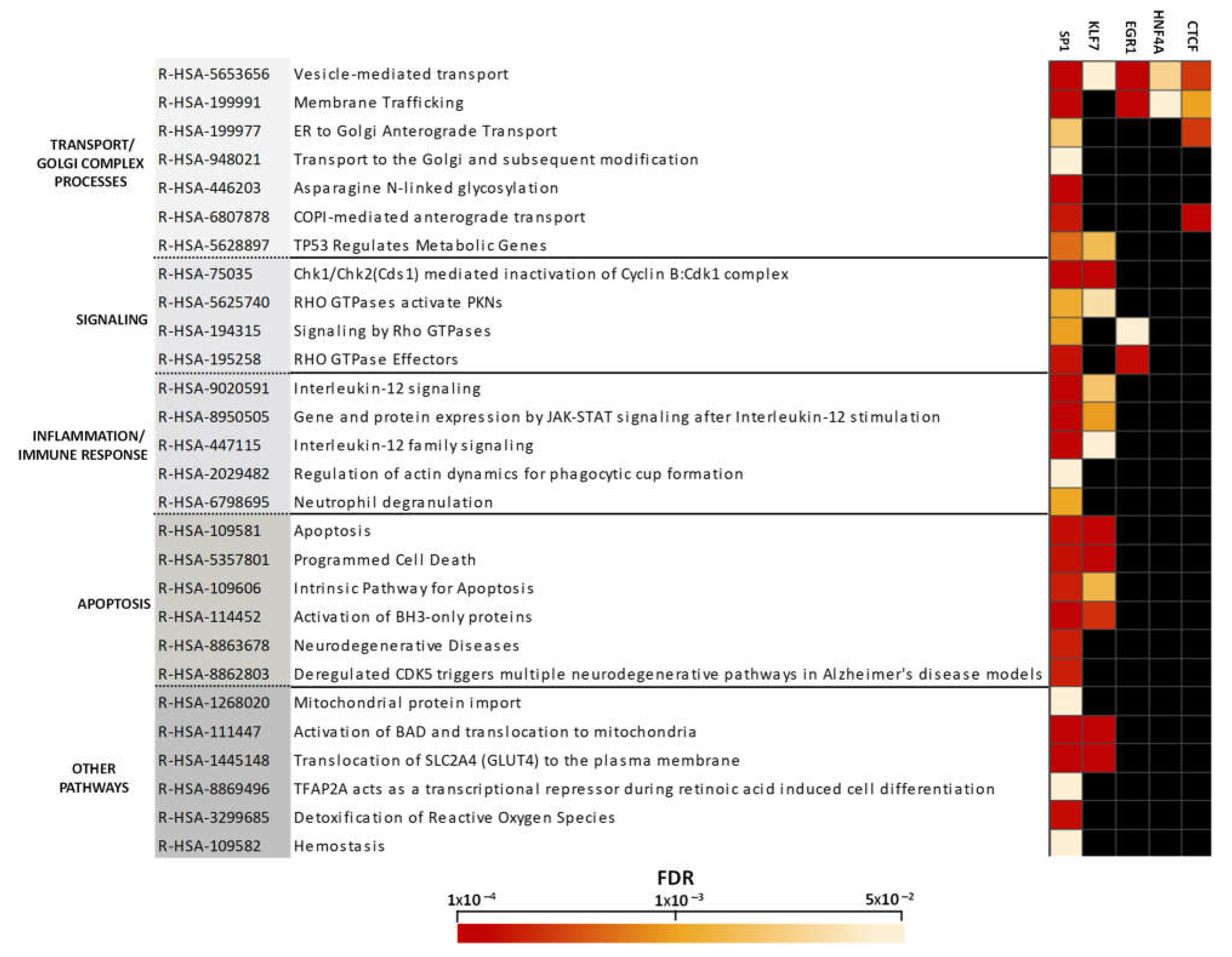

2.3. Altered Pathway Analysis Controlled by Transcriptional Programs in the Cerebellum in Chronic Schizophrenia

3. Discussion

3.1. Transcription Factor Dependent-Enriched Biological Processes

3.1.1. Cytoskeleton and Organelle Organization

3.1.2. mRNA Processing and Splicing

3.1.3. Synaptic Function

3.2. Transcription Factor Dependent-Enriched Pathways

3.2.1. Transport and Golgi Complex

3.2.2. Immune Response and Inflammatory Processes

3.2.3. Apoptotic Events

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bioinformatic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SZ | Schizophrenia |

| CB | Cerebellum |

| CCTC | Cortico-thalamo-cerebellar circuit |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| TFs | Transcription factors |

| NKX2-1 | Homeobox protein Nkx-2.1 |

| SP1 | Transcription factor SP1 |

| SP4 | Transcription factor SP4 |

| KLF7 | Krüppel-like factor 7 |

| EGR1 | Early growth response protein 1 |

| HNF4A | Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha |

| CTCF | Transcriptional repressor CTCFL |

| GABPA | GA-binding protein alpha chain |

| NRF1 | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane sensor NFE2L1 |

| NFYA | Nuclear transcription factor Y subunit alpha |

| MEF2A | Myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2A |

| YY1 | Transcriptional repressor protein YY1 |

References

- Murray, R.M.; Bhavsar, V.; Tripoli, G.; Howes, O. 30 Years on: How the Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis of Schizophrenia Morphed Into the Developmental Risk Factor Model of Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2017, 43, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.; Eyre, H.; Jacka, F.N.; Dodd, S.; Dean, O.; McEwen, S.; Debnath, M.; McGrath, J.; Maes, M.; Amminger, P.; et al. A review of vulnerability and risks for schizophrenia: Beyond the two hit hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016, 65, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapoport, J.L.; Giedd, J.N.; Gogtay, N. Neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2012. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrin CGJ, Doorduin J, Sommer IE, de Vries EFJ. The dual hit hypothesis of schizophrenia: Evidence from animal models. Vol. 131, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. Elsevier Ltd; 2021. p. 1150–68.

- Andreasen NC, Daniel S, Leary SO, Paradiso S. ·" Cognitive of " Cognitive Dysmetria " as an Integrative Theory of Dysfunction in Cortical- Schizophrenia : A Dysfunction Subcortical--Cerebellar Circuitry ? Network. 2018;(March):203–18.

- Andreasen, N.C.; Nopoulos, P.; O'Leary, D.S.; Miller, D.D.; Wassink, T.; Flaum, M. Defining the phenotype of schizophrenia: Cognitive dysmetria and its neural mechanisms. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.A.; Orr, J.M.; Mittal, V.A. Cerebello-thalamo-cortical networks predict positive symptom progression in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. NeuroImage: Clin. 2017, 14, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun Kim S, Jung S, Sung G, Bang M, Lee SH. Impaired cerebro-cerebellar white matter connectivity and its associations with cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ye, E.; Jin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L. Association between Thalamocortical Functional Connectivity Abnormalities and Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, DW. Neuroscience in the 21st century: From basic to clinical. Neuroscience in the 21st Century: From Basic to Clinical. 2013;1–3111.

- Leto, K.; Arancillo, M.; Becker, E.B.E.; Buffo, A.; Chiang, C.; Ding, B.; Dobyns, W.B.; Dusart, I.; Haldipur, P.; Hatten, M.E.; et al. Consensus Paper: Cerebellar Development. Cerebellum 2016, 15, 789–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badowska DM, Brzózka MM, Kannaiyan N, Thomas C, Dibaj P, Chowdhury A, et al. Modulation of cognition and neuronal plasticity in gain-and loss-of-function mouse models of the schizophrenia risk gene Tcf4. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mesman, S.; Bakker, R.; Smidt, M.P. Tcf4 is required for correct brain development during embryogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 106, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, B.; Gaudillière, B.; Bonni, A.; Gill, G. Transcription factor Sp4 regulates dendritic patterning during cerebellar maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 9882–9887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinacho, R.; Valdizán, E.M.; Pilar-Cuellar, F.; Prades, R.; Tarragó, T.; Haro, J.M.; Ferrer, I.; Ramos, B. Increased SP4 and SP1 transcription factor expression in the postmortem hippocampus of chronic schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 58, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, L.; McLachlan, I.; Younger, S.; Jan, L.Y.; Jan, Y.N. Differential Regulation of Dendritic and Axonal Development by the Novel Krüppel-Like Factor Dar1. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 3309–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsueh YP, Hirata Y, Simmen FA, Denver RJ, Ávila-Mendoza J, Subramani A. Krüppel-Like Factors 9 and 13 Block Axon Growth by Transcriptional Repression of Key Components of the cAMP Signaling Pathway. 2020; Available from: www.frontiersin.

- Malt, E.A.; Juhasz, K.; Malt, U.F.; Naumann, T. A Role for the Transcription Factor Nk2 Homeobox 1 in Schizophrenia: Convergent Evidence from Animal and Human Studies. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 59–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Montecinos, A.; Rodríguez-Mias, R.; MacDowell, K.S.; García-Bueno, B.; Bris, Á.G.; Caso, J.R.; Villén, J.; Ramos, B. Analysis of Molecular Networks in the Cerebellum in Chronic Schizophrenia: Modulation by Early Postnatal Life Stressors in Murine Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Shachar, D. The interplay between mitochondrial complex I, dopamine and Sp1 in schizophrenia. J Neural Transm. 2009;116(11):1383–96.

- Fusté, M.; Meléndez-Pérez, I.; Villalta-Gil, V.; Pinacho, R.; Villalmanzo, N.; Cardoner, N.; Menchón, J.M.; Haro, J.M.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Ramos, B. Specificity proteins 1 and 4, hippocampal volume and first-episode psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté, M.; Pinacho, R.; Meléndez-Pérez, I.; Villalmanzo, N.; Villalta-Gil, V.; Haro, J.M.; Ramos, B. Reduced expression of SP1 and SP4 transcription factors in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in first-episode psychosis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1608–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Li, T.; Wang, M.; Wen, Z.; Li, W.; Qiang, Y.; et al. Role played by theSP4gene in schizophrenia and major depressive disorder in the Han Chinese population. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinacho, R.; Villalmanzo, N.; Roca, M.; Iniesta, R.; Monje, A.; Haro, J.M.; Meana, J.J.; Ferrer, I.; Gill, G.; Ramos, B. Analysis of Sp transcription factors in the postmortem brain of chronic schizophrenia: A pilot study of relationship to negative symptoms. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinacho, R.; Saia, G.; Meana, J.J.; Gill, G.; Ramos, B. Transcription factor SP4 phosphorylation is altered in the postmortem cerebellum of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia subjects. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1650–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saia, G.; Lalonde, J.; Sun, X.; Ramos, B.; Gill, G. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor Sp4 is reduced by NMDA receptor signaling. J. Neurochem. 2014, 129, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinacho, R.; Saia, G.; Fusté, M.; Meléndez-Pérez, I.; Villalta-Gil, V.; Haro, J.M.; Gill, G.; Ramos, B. Phosphorylation of Transcription Factor Specificity Protein 4 Is Increased in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of First-Episode Psychosis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0125115–e0125115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Over-representation of potential SP4 target genes within schizophrenia-risk genes. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 27, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.-M.; Chen, S.-J.; Hsu, S.-H.; Cheng, M.-C. Functional analyses and effect of DNA methylation on the EGR1 gene in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 275, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaker, R.C.; Bowling, K.M.; Lasseigne, B.N.; Hagenauer, M.H.; Hardigan, A.A.; Davis, N.S.; Gertz, J.; Cartagena, P.M.; Walsh, D.M.; Vawter, M.P.; et al. Post-mortem molecular profiling of three psychiatric disorders. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, Y.; Kawahara-Miki, R.; Kida, S.; Sotoyama, H.; Gabdulkhaev, R.; Takahashi, H.; Kunii, Y.; Hino, M.; Nagaoka, A.; Izumi, R.; et al. Elevation of EGR1/zif268, a Neural Activity Marker, in the Auditory Cortex of Patients with Schizophrenia and its Animal Model. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 2715–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vawter, M.P.; Mamdani, F.; Macciardi, F. An integrative functional genomics approach for discovering biomarkers in schizophrenia. Briefings Funct. Genom. 2011, 10, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraeva, D.; Haenisch, B.; Zapatka, M.; Frank, J.; GROUP Investigators ,; PSYCH-GEMS SCZ working group ,; Witt, S.H.; Mühleisen, T.W.; Treutlein, J.; Strohmaier, J.; et al. Integrated Pathway-Based Approach Identifies Association between Genomic Regions at CTCF and CACNB2 and Schizophrenia. PLOS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004345. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Luo, X.-J. Functional genomics reveal gene regulatory mechanisms underlying schizophrenia risk. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Huo, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Xiao, X.; et al. Regulatory variants at 2q33.1 confer schizophrenia risk by modulating distal gene TYW5 expression. Brain 2021, 145, 770–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeekin, L.J.; Lucas, E.K.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H.; McCullumsmith, R.E.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Gamble, K.L.; Cowell, R.M. Cortical PGC-1α-Dependent Transcripts Are Reduced in Postmortem Tissue From Patients With Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Long, Q.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Guo, Z.; Teng, Z.; Zeng, Y. The NRF1/miR-4514/SOCS3 Pathway Is Associated with Schizophrenia Pathogenesis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosci. 2021, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeland, O.B.; Frei, O.; Kauppi, K.; Hill, W.D.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Krull, F.; Bettella, F.; Eriksen, J.A.; Witoelar, A.; et al. Identification of Genetic Loci Jointly Influencing Schizophrenia Risk and the Cognitive Traits of Verbal-Numerical Reasoning, Reaction Time, and General Cognitive Function. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.C.; Javidfar, B.; Pothula, V.; Ibi, D.; Shen, E.Y.; Peter, C.J.; Bicks, L.K.; Fehr, T.; Jiang, Y.; Brennand, K.J.; et al. MEF2C transcription factor is associated with the genetic and epigenetic risk architecture of schizophrenia and improves cognition in mice. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, J.; Crofts, L.A.; Quinlan, K.G.; Czolij, R.; Perkins, A.C.; Crossley, M. Human KLF17 is a new member of the Sp/KLF family of transcription factors. Genomics 2006, 87, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, J.; Kim, S.; Reimers, M.; Bacanu, S.-A.; Yu, H.; Liu, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, Q.; et al. Transcriptome sequencing and genome-wide association analyses reveal lysosomal function and actin cytoskeleton remodeling in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-Y.; Hsu, T.-I.; Chuang, J.-Y.; Su, T.-P.; Chang, W.-C.; Hung, J.-J. Sp1 in Astrocyte Is Important for Neurite Outgrowth and Synaptogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, B.; Valín, A.; Sun, X.; Gill, G. Sp4-dependent repression of neurotrophin-3 limits dendritic branching. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2009, 42, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, F.; Lei, L.; Sumiyoshi, H.; Kajimura, D.; Dragomir, C.; Smaldone, S.; Puche, A.C.; Petros, T.J.; Mason, C.; Parada, L.F.; et al. Transcription Factor KLF7 Is Important for Neuronal Morphogenesis in Selected Regions of the Nervous System. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 5699–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, F.; Aldabe, R.; Friedrich, V.; Ohnishi, S.; Yoshida, T.; Ramirez, F. Developmental Expression of Mouse Krüppel-like Transcription Factor KLF7 Suggests a Potential Role in Neurogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2001, 233, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, F.; Lei, L.; Sumiyoshi, H.; Kajimura, D.; Dragomir, C.; Smaldone, S.; Puche, A.C.; Petros, T.J.; Mason, C.; Parada, L.F.; et al. Transcription Factor KLF7 Is Important for Neuronal Morphogenesis in Selected Regions of the Nervous System. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 5699–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, G.; A Briggs, J.; Vanichkina, D.P.; Poth, E.M.; Beveridge, N.J.; Ratnu, V.S.; Nayler, S.P.; Nones, K.; Hu, J.; Bredy, T.W.; et al. The long non-coding RNA Gomafu is acutely regulated in response to neuronal activation and involved in schizophrenia-associated alternative splicing. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saia-Cereda, V.M.; Santana, A.G.; Schmitt, A.; Falkai, P.; Martins-De-Souza, D. The Nuclear Proteome of White and Gray Matter from Schizophrenia Postmortem Brains. Complex Psychiatry 2017, 3, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, K.; Lipska, B.K.; Hyde, T.M.; Ye, T.; Newburn, E.N.; Morita, Y.; Vakkalanka, R.; Barenboim, M.; Sei, Y.; Weinberger, D.R.; et al. DISC1 splice variants are upregulated in schizophrenia and associated with risk polymorphisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 15873–15878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, A.J.; Kleinman, J.E.; Weinberger, D.R.; Weickert, C.S. Disease-associated intronic variants in the ErbB4 gene are related to altered ErbB4 splice-variant expression in the brain in schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberstein, M.; Amit, M.; Vaknin, K.; O'Donnell, A.; Farhy, C.; Lerenthal, Y.; Shomron, N.; Shaham, O.; Sharrocks, A.D.; Ashery-Padan, R.; et al. Regulation of transcription of the RNA splicing factor hSlu7 by Elk-1 and Sp1 affects alternative splicing. RNA 2007, 13, 1988–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalizi A, Gaudillière B, Yuan Z, Stegmüller J, Shirogane T, Ge Q, et al. A Calcium-Regulated MEF2 Sumoylation Switch Controls Postsynaptic Differentiation. Science (1979). 2006 Feb 17;311(5763):1012 LP – 1017.

- Lisek, M.; Przybyszewski, O.; Zylinska, L.; Guo, F.; Boczek, T. The Role of MEF2 Transcription Factor Family in Neuronal Survival and Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, C.; Drago, A.; Calabrò, M.; Spina, E.; Serretti, A. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry A molecular pathway analysis informs the genetic background at risk for schizophrenia. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 59, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, J.H.; Zambach, S.K.; Ingason, A.; Lundin, P.; Hansen, T.; Bertalan, M.; Rosengren, A.; Bjerre, D.; Ferrero-Miliani, L.; Rasmussen, H.B.; et al. Linkage and whole genome sequencing identify a locus on 6q25–26 for formal thought disorder and implicate MEF2A regulation. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 169, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, R.E.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Craig, T.J.; Ashby, M.C.; Henley, J.M. MEF2A regulates mGluR-dependent AMPA receptor trafficking independently of Arc/Arg3.1. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson P, T DJS. ER-to-Golgi transport : Form and formation of vesicular and tubular carriers. 2005;1744:304–15.

- Qin, F.; Chen, G.; Yu, K.N.; Yang, M.; Cao, W.; Kong, P.; Peng, S.; Sun, M.; Nie, L.; Han, W. Golgi Phosphoprotein 3 Mediates Radiation-Induced Bystander Effect via ERK/EGR1/TNF-α Signal Axis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadik M, Nia A, Wetter L, Feuk L. Transcriptome analysis of fibroblasts from schizophrenia patients reveals differential expression of schizophrenia-related genes. 2020;1–9.

- Vawter M, Mamdani F, Macciardi F. An integrative functional genomics approach for discovering biomarkers in schizophrenia. 2011;(December).

- Altamura, A.C.; Pozzoli, S.; Fiorentini, A.; Dell'Osso, B. Neurodevelopment and inflammatory patterns in schizophrenia in relation to pathophysiology. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 42, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.M.; McEvoy, J.P.; Davis, V.G.; Goff, D.C.; Nasrallah, H.A.; Davis, S.M.; Hsiao, J.K.; Swartz, M.S.; Stroup, T.S.; Lieberman, J.A. Inflammatory Markers in Schizophrenia: Comparing Antipsychotic Effects in Phase 1 of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness Study. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, W.S.; Phillips, M.R.; Yang, L.H.; Kegeles, L.S.; Susser, E.S.; Lieberman, J.A. Neurodegenerative model of schizophrenia: Growing evidence to support a revisit. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 243, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comer, A.L.; Carrier, M.; Tremblay, M.È.; Cruz-Martín, A. The Inflamed Brain in Schizophrenia: The Convergence of Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors That Lead to Uncontrolled Neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gober, R.; Dallmeier, J.; Davis, D.; Brzostowicki, D.; Vaccari, J.P.d.R.; Cyr, B.; Barreda, A.; Sun, X.; Gultekin, S.H.; Garamszegi, S.; et al. Increased inflammasome protein expression identified in microglia from postmortem brains with schizophrenia. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 83, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.J.; Goldsmith, D.R. Evaluating the Hypothesis That Schizophrenia Is an Inflammatory Disorder. FOCUS 2020, 18, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes OD, Mccutcheon R. Inflammation and the neural diathesis-stress hypothesis of schizophrenia: a reconceptualization. 2017;7. Available from: www.nature.com/tp.

- Hughes, H.; Ashwood, P. Overlapping evidence of innate immune dysfunction in psychotic and affective disorders. Brain, Behav. Immun. - Heal. 2020, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond G, Lançon C, Korchia T, Auquier P, Boyer L. The Role of Inflammation in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Vol. 11, Frontiers in Psychiatry. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020.

- Carril Pardo C, Oyarce Merino K, Vera-Montecinos A. Neuroinflammatory Loop in Schizophrenia, Is There a Relationship with Symptoms or Cognition Decline? Vol. 26, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2025.

- Cui, L.-B.; Wang, X.-Y.; Fu, Y.-F.; Liu, X.-F.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, S.-W.; Gu, Y.-W.; Fan, J.-W.; Wu, W.-J.; Gong, H.; et al. Transcriptional level of inflammation markers associates with short-term brain structural changes in first-episode schizophrenia. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, M.; Zohora, F.T.; Anka, A.U.; Ali, K.; Maleknia, S.; Saffarioun, M.; Azizi, G. Interleukin-6 cytokine: An overview of the immune regulation, immune dysregulation, and therapeutic approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 111, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Liang M, Tang Y, Ma D, Li M, Yuan C, et al. KLF7 promotes adipocyte inflammation and glucose metabolism disorder by activating the PKCζ/NF-κB pathway. FASEB Journal. 2023 Jul 1;37(7).

- Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Ha, X.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Feng, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. The Effect and Mechanism of KLF7 in the TLR4/NF-κB/IL-6 Inflammatory Signal Pathway of Adipocytes. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovac, J.; Bosch, M.; Okamoto, K. Regulation of actin dynamics during structural plasticity of dendritic spines: Signaling messengers and actin-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 91, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tian, B.; Han, H.-B. Serum interleukin-6 in schizophrenia: A system review and meta-analysis. Cytokine 2021, 141, 155441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, L.; Goduni, L.; Takami, Y.; Sharma, N.; Kapil, P.; Jain, M.K.; Mahabeleshwar, G.H. Kruppel-Like Factor 2 Is a Transcriptional Regulator of Chronic and Acute Inflammation. 2013, 182, 1696–1704. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.-W.; Lian, H.; Zhong, B.; Shu, H.-B.; Li, S. Krüppel-like factor 4 negatively regulates cellular antiviral immune response. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, D.; Das, R.; Narla, G.; Simon, D.I.; Jain, M.K.; Mahabeleshwar, G.H. Kruppel-like Transcription Factor 6 Regulates Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 10318–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Kim, H.-P.; Xue, H.-H.; Liu, H.; Zhao, K.; Leonard, W.J. Interleukin-21 Receptor Gene Induction in Human T Cells Is Mediated by T-Cell Receptor-Induced Sp1 Activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 9741–9752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Said H, FKMAR; et al. MiR302c, Sp1, and NFATc2 regulate interleukin-21 expression in human CD4+CD45RO+ T lymphocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5998–6011.

- Shbeer, A.M.; Robadi, I.A. The role of Interleukin-21 in autoimmune Diseases: Mechanisms, therapeutic Implications, and future directions. Cytokine 2024, 173, 156437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.-J.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.-L.; Wei, L.; Li, F.; Lu, J.; Huang, B.-Q. Transcription Factors Ets2 and Sp1 Act Synergistically with Histone Acetyltransferase p300 in Activating Human Interleukin-12 p40 Promoter. Acta Biochim. et Biophys. Sin. 2006, 38, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.D.; Read, K.A.; Sreekumar, B.K.; Jones, D.M.; Oestreich, K.J. IL-12 signaling drives the differentiation and function of a TH1-derived TFH1-like cell population. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Y k, Suh I b, Kim H, Han C s, Lim C s, Choi S h, et al. The plasma levels of interleukin-12 in schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar mania : effects of psychotropic drugs. 2002;1107–14.

- Ozbey, U.; Tug, E.; Kara, M.; Namli, M. The value of interleukin-12B (p40) gene promoter polymorphism in patients with schizophrenia in a region of East Turkey. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 62, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-. .-W.; Lee, Y.; Kwon, H.-.-J.; Kim, D.-.-S. Sp1-associated activation of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 promoter by CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide and lipopolysaccharide. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaszko, M.; Kimmel, M. NF-κB and IRF pathways: cross-regulation on target genes promoter level. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, K.S.; Pinacho, R.; Leza, J.C.; Costa, J.; Ramos, B.; García-Bueno, B. Differential regulation of the TLR4 signalling pathway in post-mortem prefrontal cortex and cerebellum in chronic schizophrenia: Relationship with SP transcription factors. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 79, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell BF, Faux SF, McCarley RW, Kimble MO, Salisbury DF, Nestor PG, et al. Increased Rate of P300 Latency Prolongation with Age in Schizophrenia: Electrophysiological Evidence for a Neurodegenerative Process. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995 Jul 1;52(7):544–9.

- Morén, C.; Treder, N.; Martínez-Pinteño, A.; Rodríguez, N.; Arbelo, N.; Madero, S.; Gómez, M.; Mas, S.; Gassó, P.; Parellada, E. Systematic Review of the Therapeutic Role of Apoptotic Inhibitors in Neurodegeneration and Their Potential Use in Schizophrenia. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glantz, L.A.; Gilmore, J.H.; Lieberman, J.A.; Jarskog, L.F. Apoptotic mechanisms and the synaptic pathology of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2006, 81, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parellada, E.; Gassó, P. Glutamate and microglia activation as a driver of dendritic apoptosis: a core pathophysiological mechanism to understand schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniaud, E.; Baguet, J.; Mathieu, A.-L.; Pagès, G.; Marvel, J.; Leverrier, Y. Overexpression of Sp1 transcription factor induces apoptosis. Oncogene 2006, 25, 7096–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, B.; Flashner, S.; Beishline, K.; Sowash, A.; Donovan, K.; Bassett, G.; Azizkhan-Clifford, J. Caspase cleavage of transcription factor Sp1 enhances apoptosis. Apoptosis 2018, 23, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniaud E, Baguet J, Chalard R, Blanquier B, Brinza L, Meunier J, et al. Overexpression of transcription factor Sp1 leads to gene expression perturbations and cell cycle inhibition. Overexpression of Transcription Factor Sp1 Leads to Gene Expression Perturbations and Cell Cycle Inhibition. PLoS One [Internet]. 2009;4(9). Available from: https://inria.hal.science/hal-00851247.

- Lei, L.; Laub, F.; Lush, M.; Romero, M.; Zhou, J.; Luikart, B.; Klesse, L.; Ramirez, F.; Parada, L.F. The zinc finger transcription factor Klf7 is required for TrkA gene expression and development of nociceptive sensory neurons. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallipattu, S.K.; Horne, S.J.; D’agati, V.; Narla, G.; Liu, R.; Frohman, M.A.; Dickman, K.; Chen, E.Y.; Ma’ayan, A.; Bialkowska, A.B.; et al. Krüppel-like factor 6 regulates mitochondrial function in the kidney. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 1347–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piret, S.E.; Guo, Y.; Attallah, A.A.; Horne, S.J.; Zollman, A.; Owusu, D.; Henein, J.; Sidorenko, V.S.; Revelo, M.P.; Hato, T.; et al. Krüppel-like factor 6–mediated loss of BCAA catabolism contributes to kidney injury in mice and humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Kong, F.; Zhao, G.; Jin, J.; Feng, S.; Li, M. USP7 alleviates neuronal inflammation and apoptosis in spinal cord injury via deubiquitinating NRF1/KLF7 axis. Neurol. Res. 2024, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarskog, L.F.; Glantz, L.A.; Gilmore, J.H.; Lieberman, J.A. Apoptotic mechanisms in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005, 29, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Duncan, D.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, B. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W77–W83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).