Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related work

2.1. Geoinformation and Location-Based Services

2.2. Trajectory Analysis and Spatial Semantics

2.3. Augmented Reality as a Cartographic Interface

2.4. Semantic Frameworks and Narrative Cartography

2.5. Smart Heritage and Sustainability Competences

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Methodological Orientation

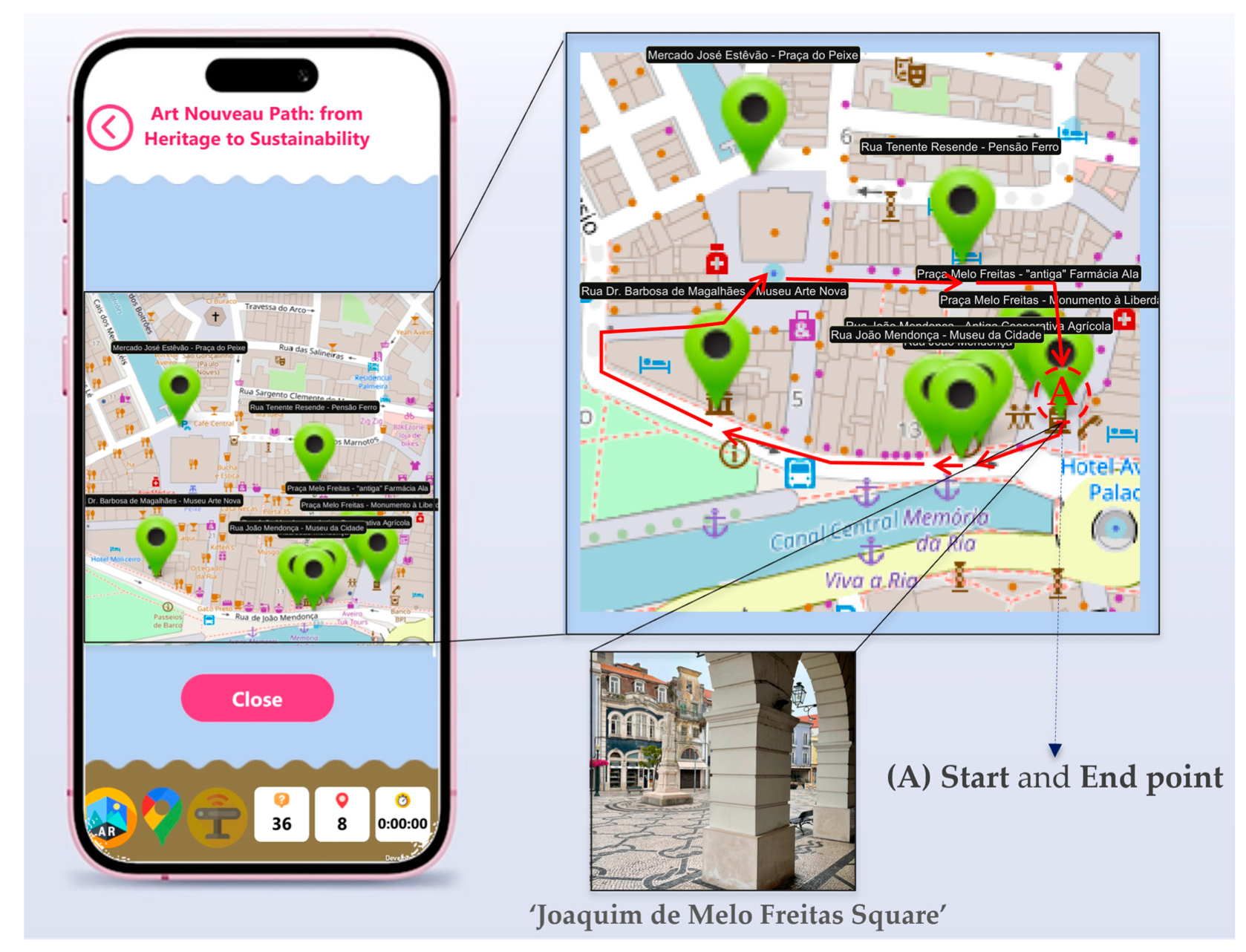

3.2. Study Context and Intervention

3.3. Participants

3.4. Data Collection Instruments

| Instrument (Code) | Participants (N) | Focus | Data Type | Purpose within the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers’ Curriculum Review (T1-R) | 3 in-service teachers | Curricular alignment, interdisciplinarity, cognitive adequacy, sustainability competences | Structured rubric with written justifications | External validation of the game’s pedagogical and curricular coherence |

| Students’ Post-Game Questionnaire (S2-POST) | 439 students | Learning outcomes, perceptions of heritage–sustainability links, AR experience | Open-ended responses (qualitative) | Capture student sense-making, affective engagement, and suggestions for improvement |

| Teachers’ Observation Protocol (T2-OBS) | 24 teachers | Student engagement, collaboration, group dynamics, AR use in situ | Likert items, checklists, narrative comments | Provide ecological evidence of learning processes under authentic conditions |

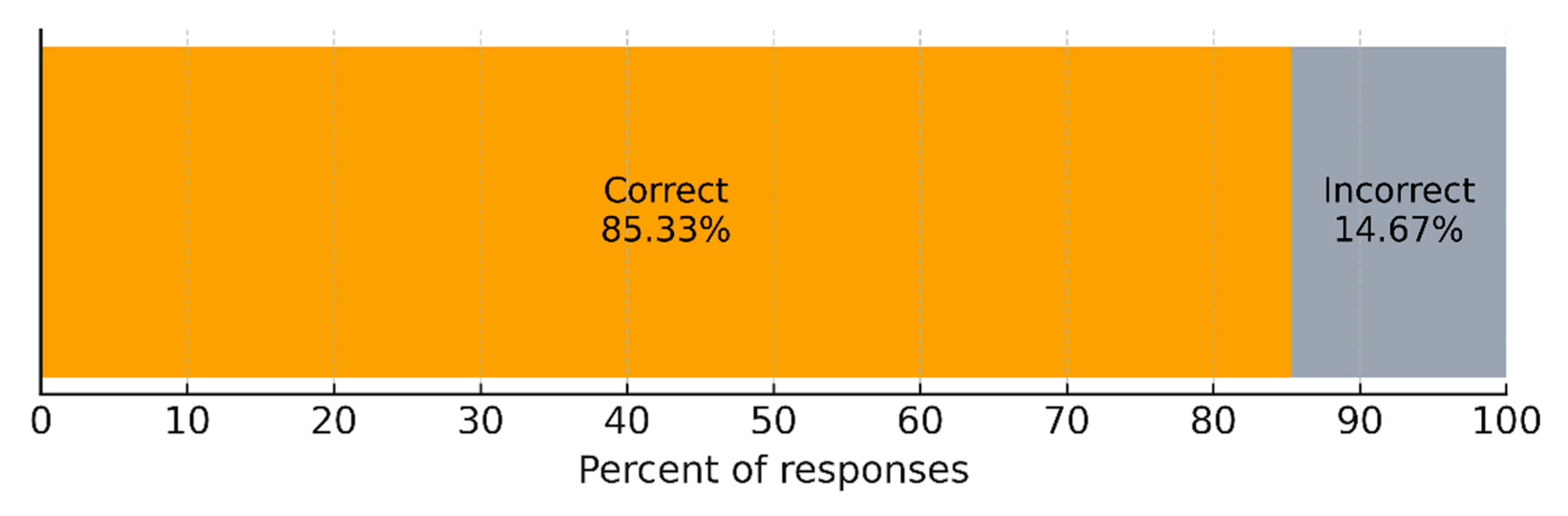

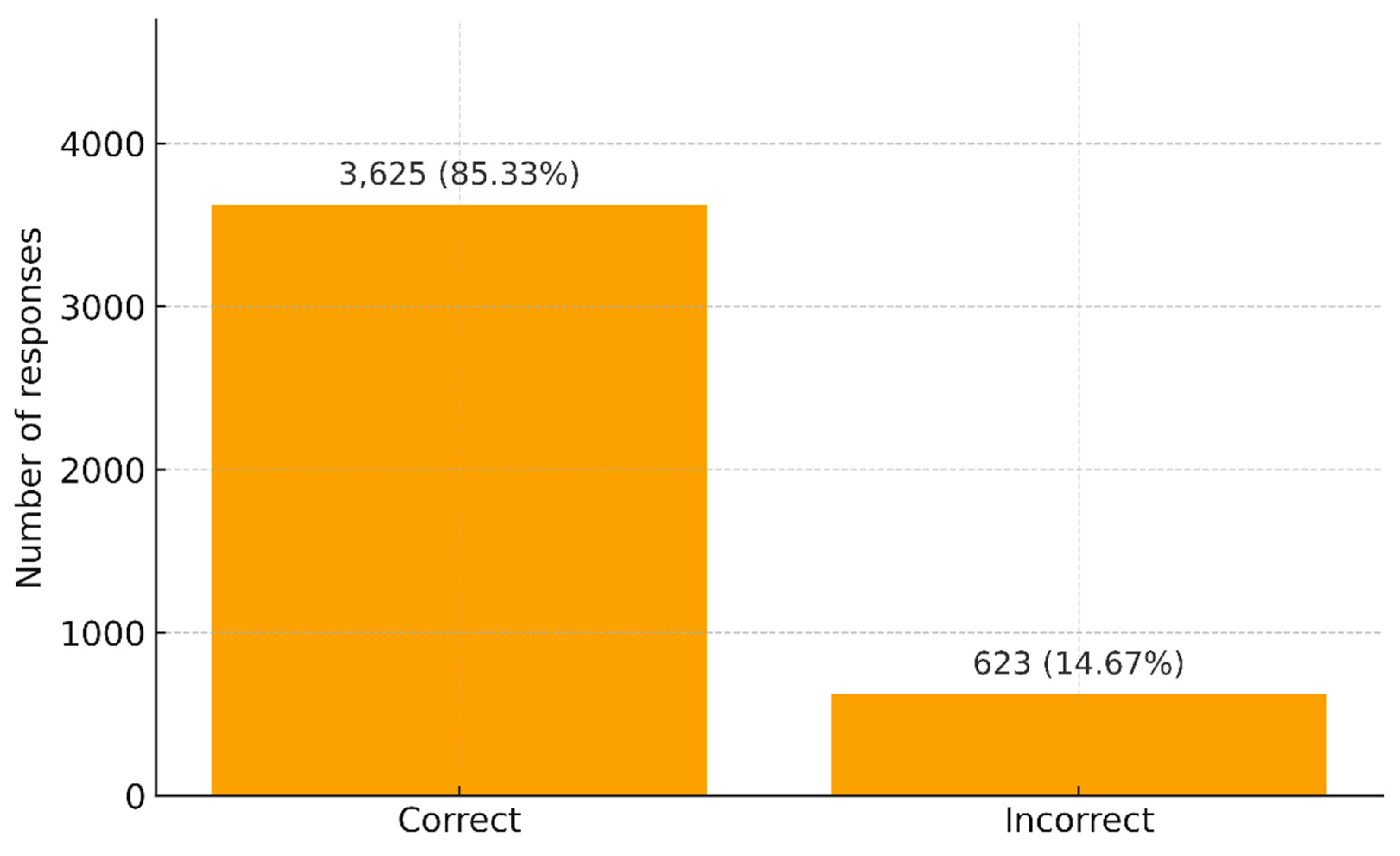

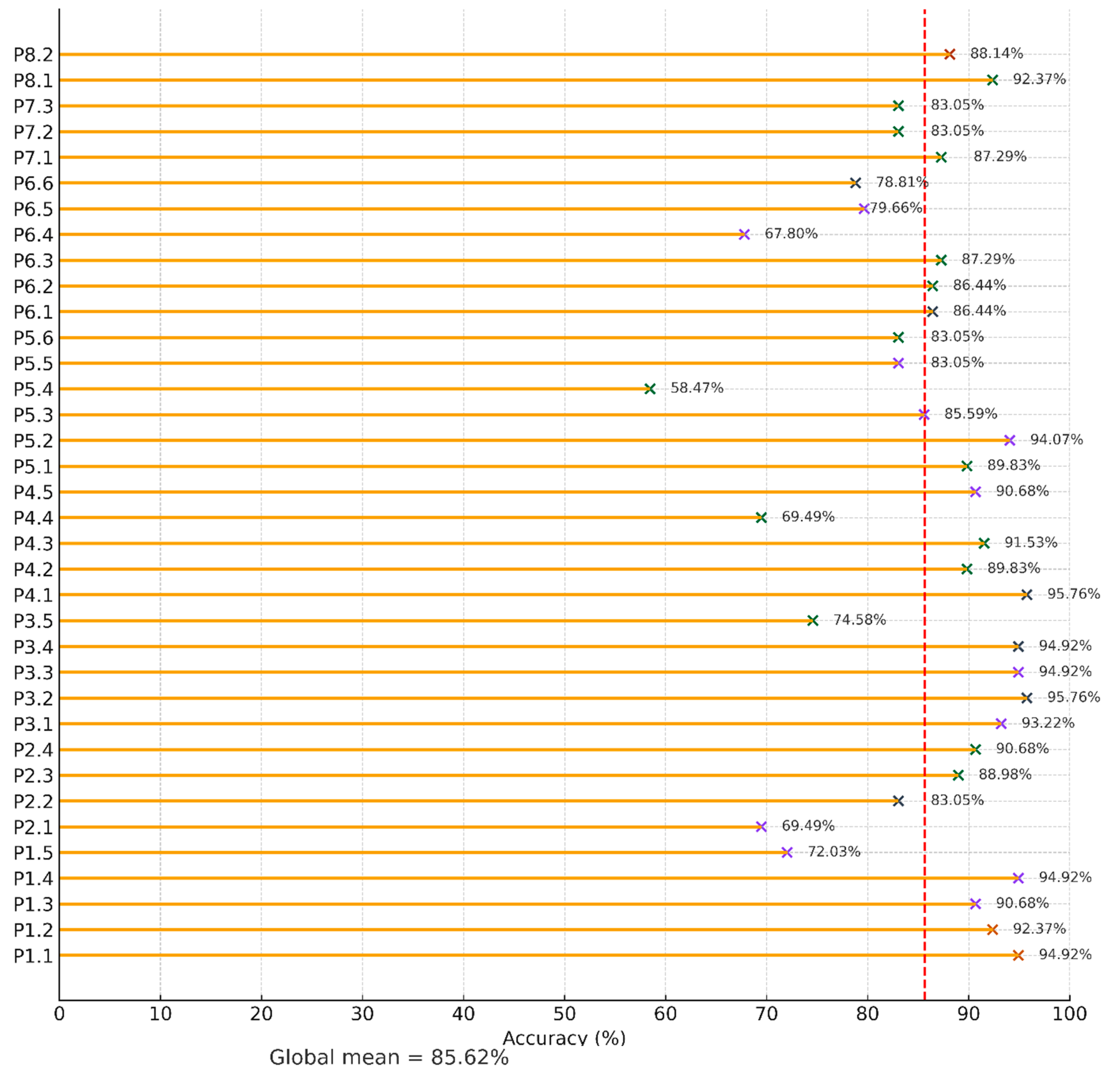

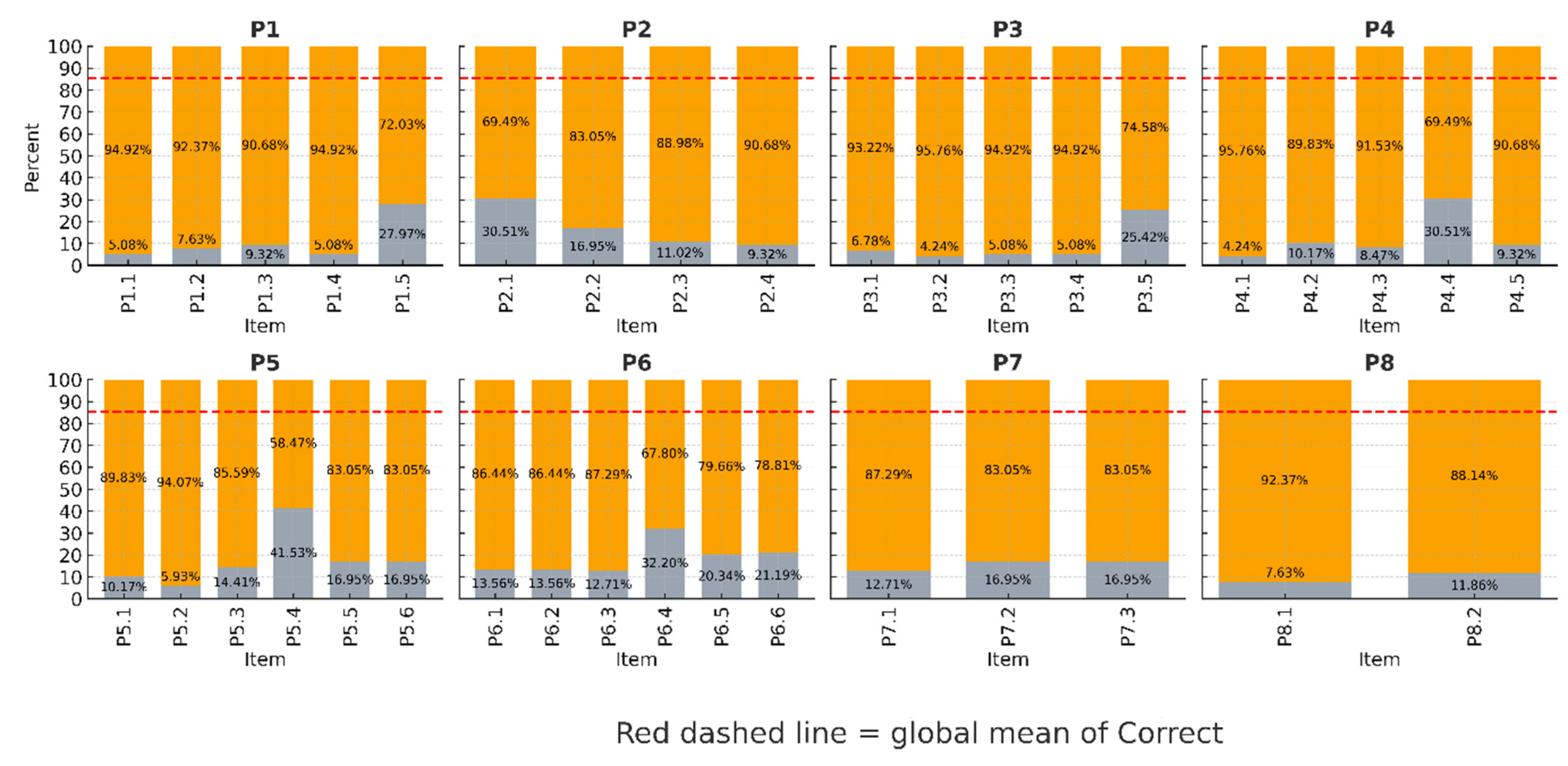

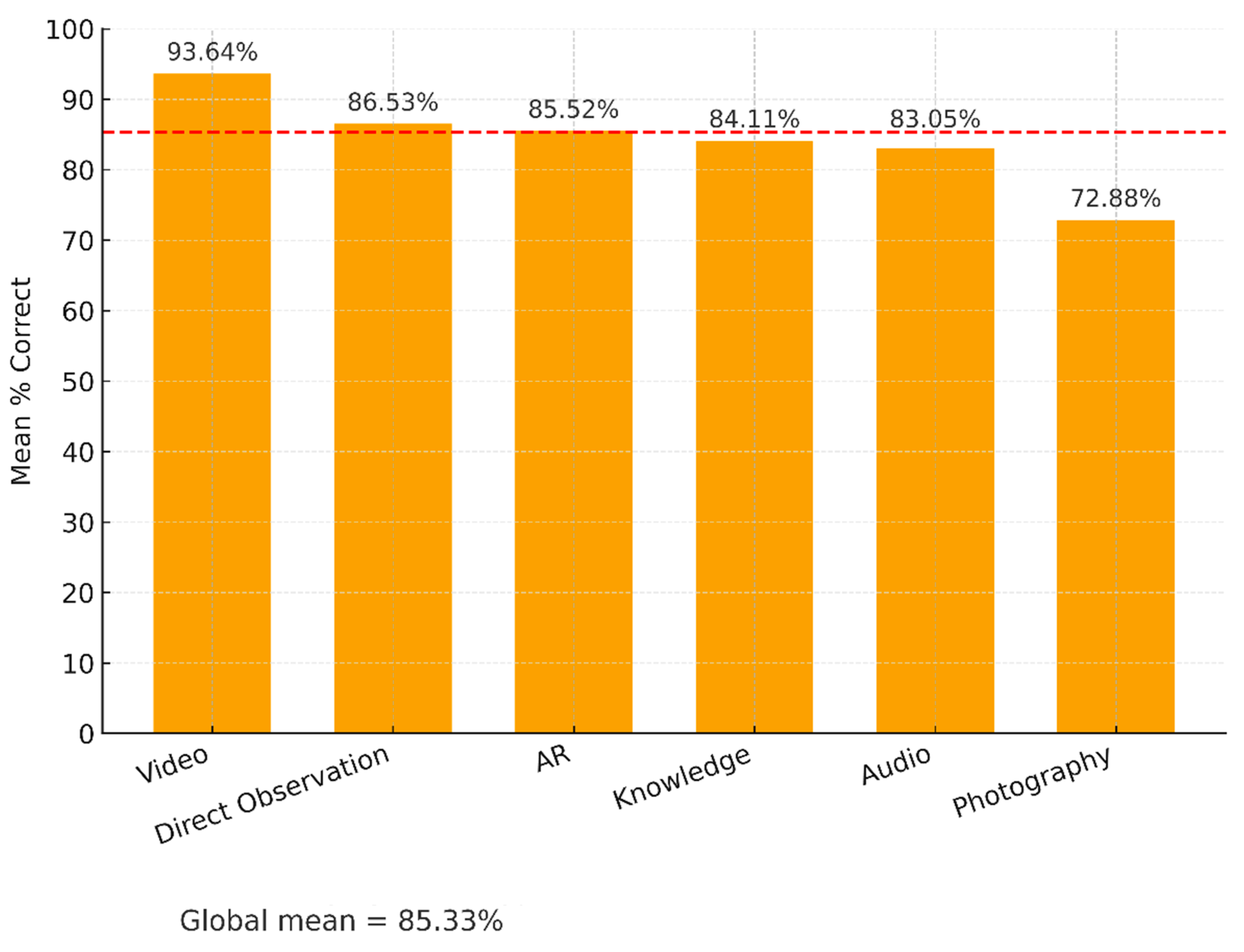

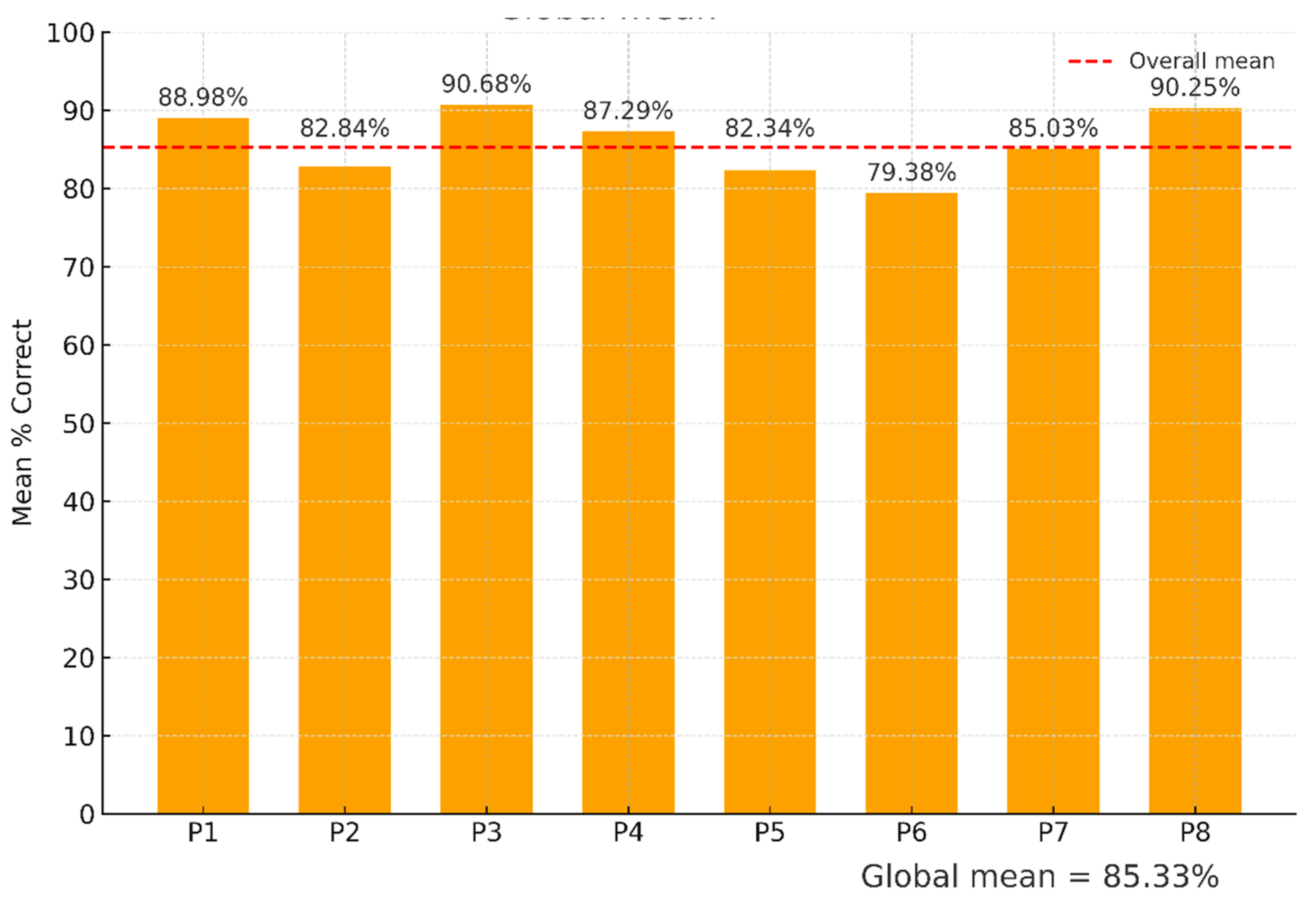

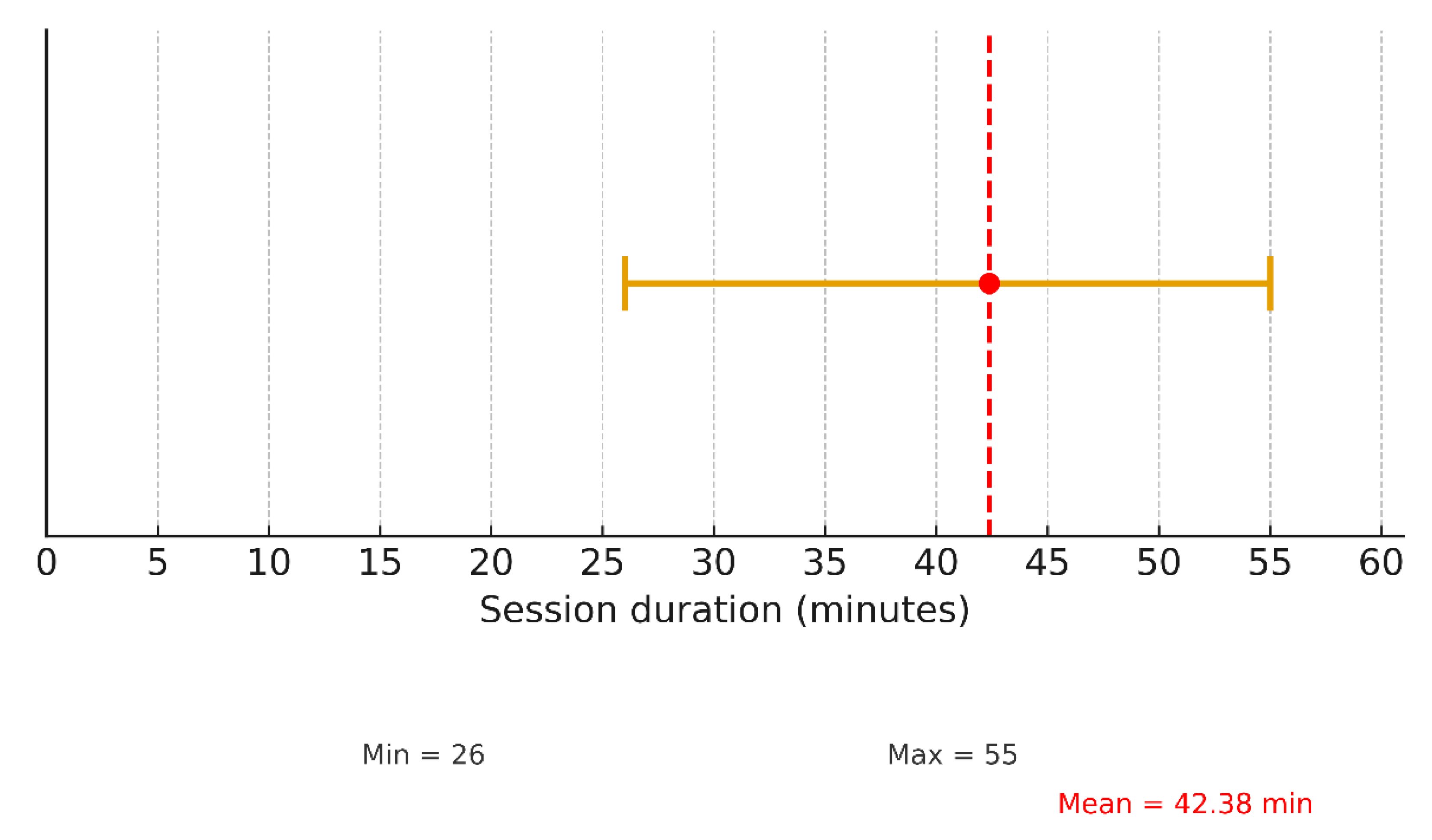

| Automated Gameplay Logs | 118 student groups | Completion, correctness, distractor choice, total session duration | App-generated, anonymised performance traces | Identify accuracy patterns, common misconceptions, and feasibility of path duration |

3.5. Field Procedures and Data Capture

3.6. Data Analysis Strategy

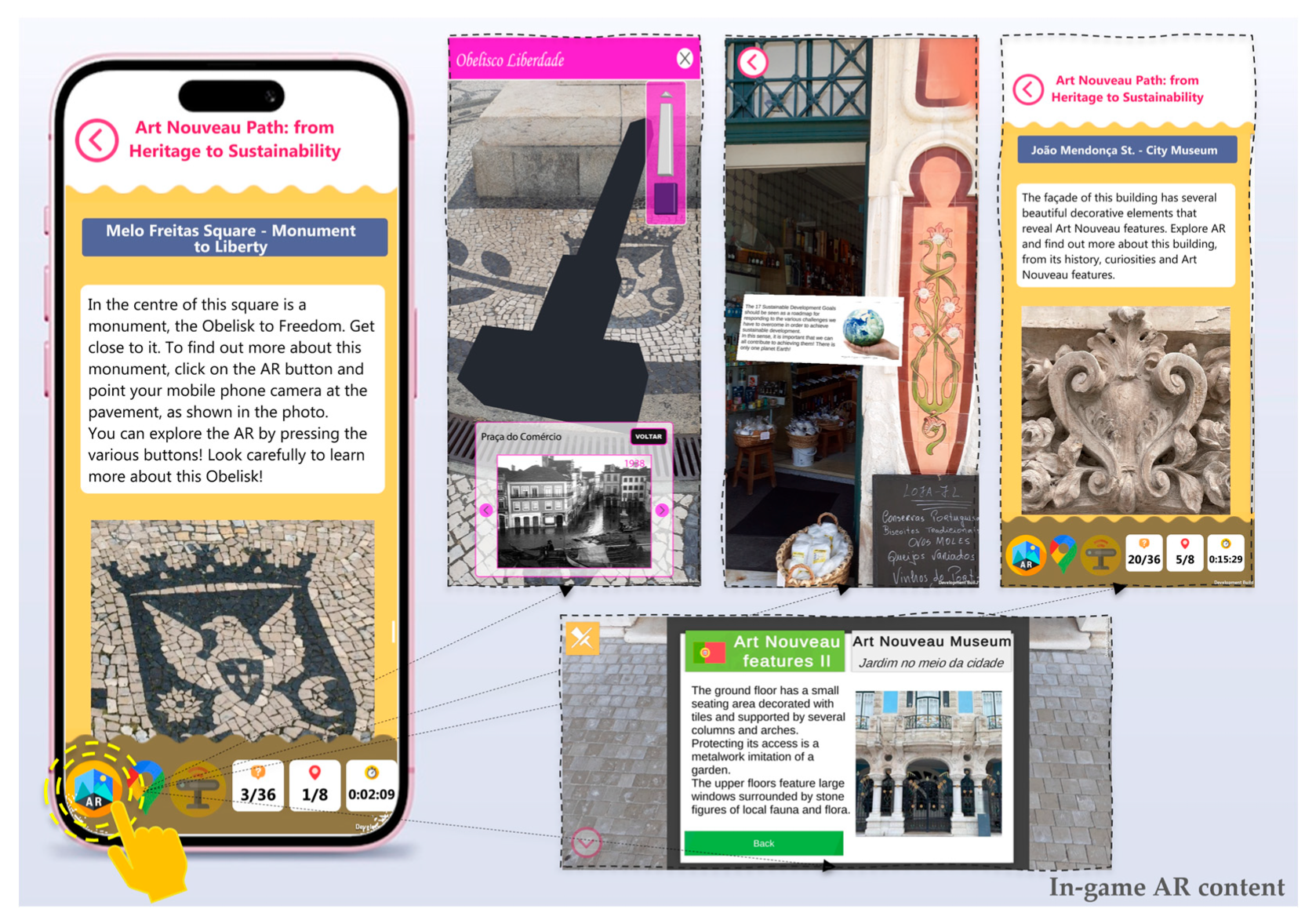

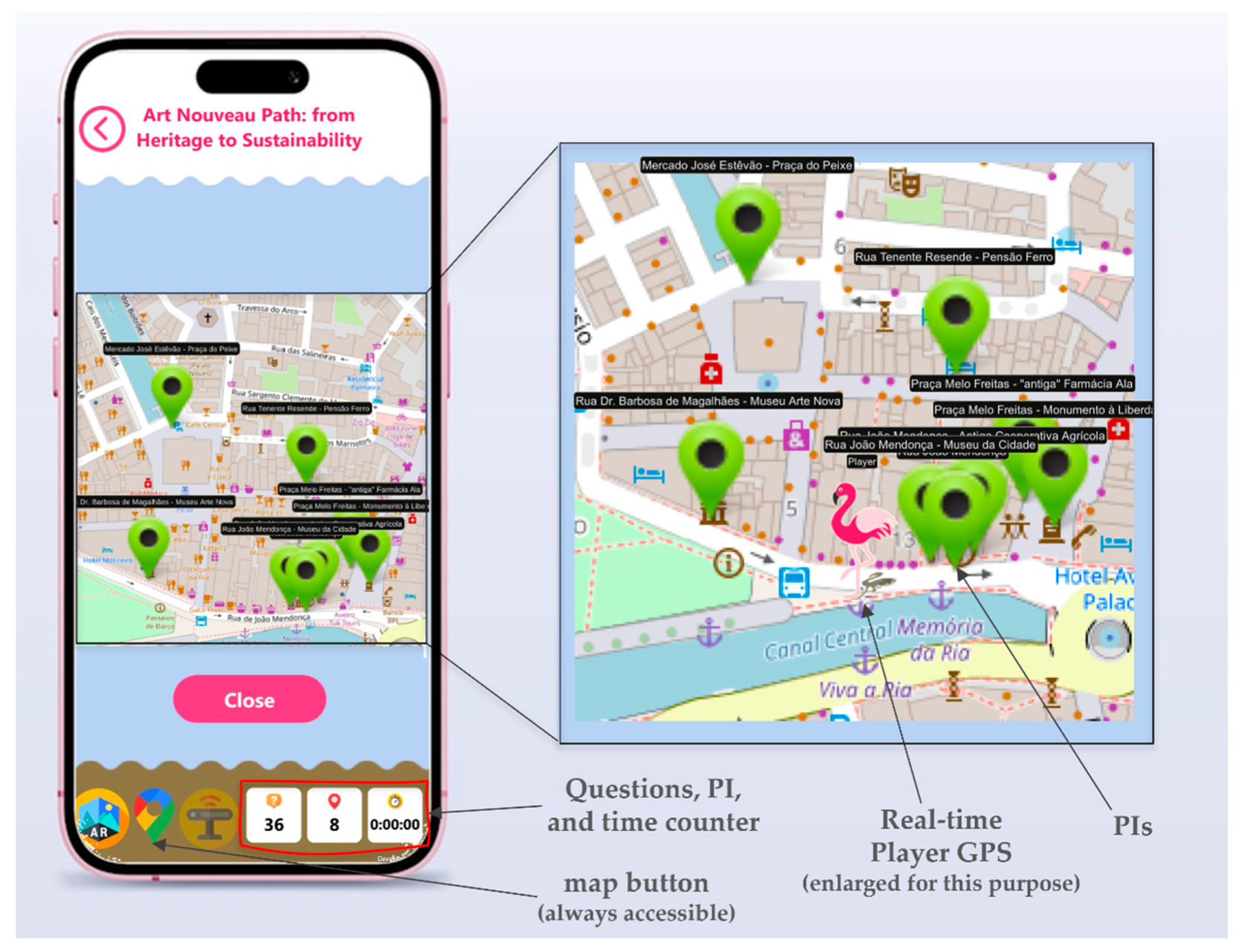

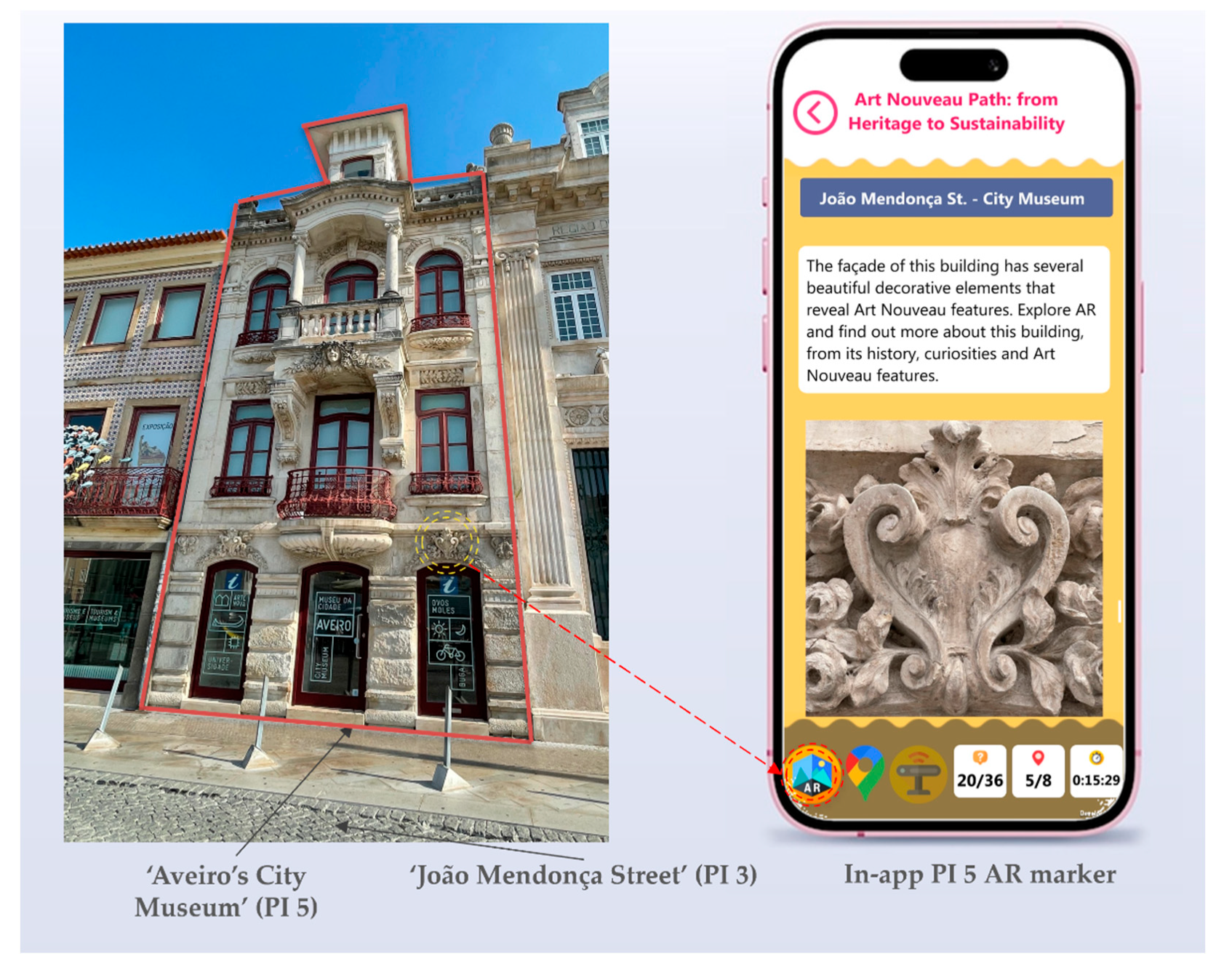

4. Findings from the Art Nouveau Path Implementation

4.1. Overview of Data Sources

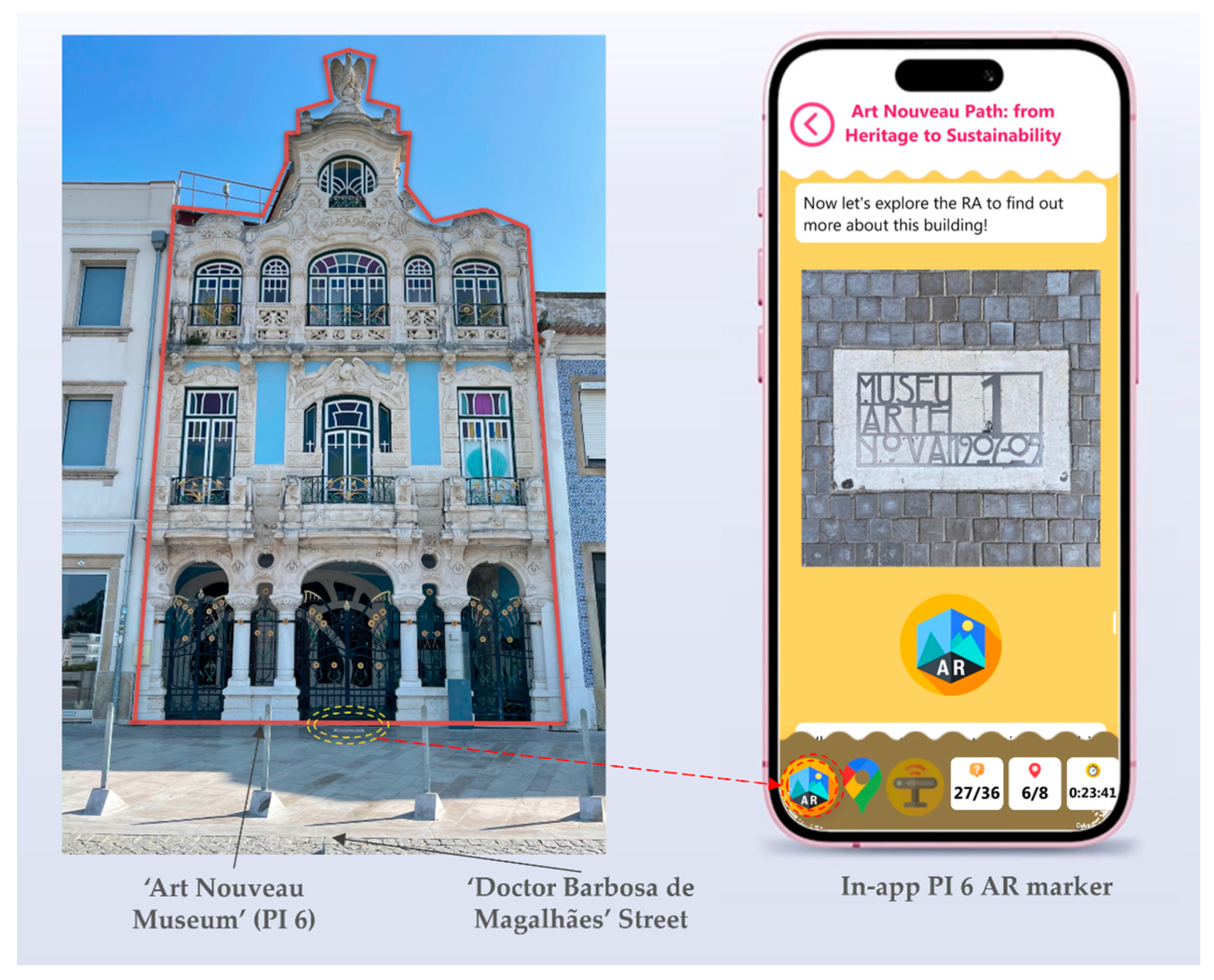

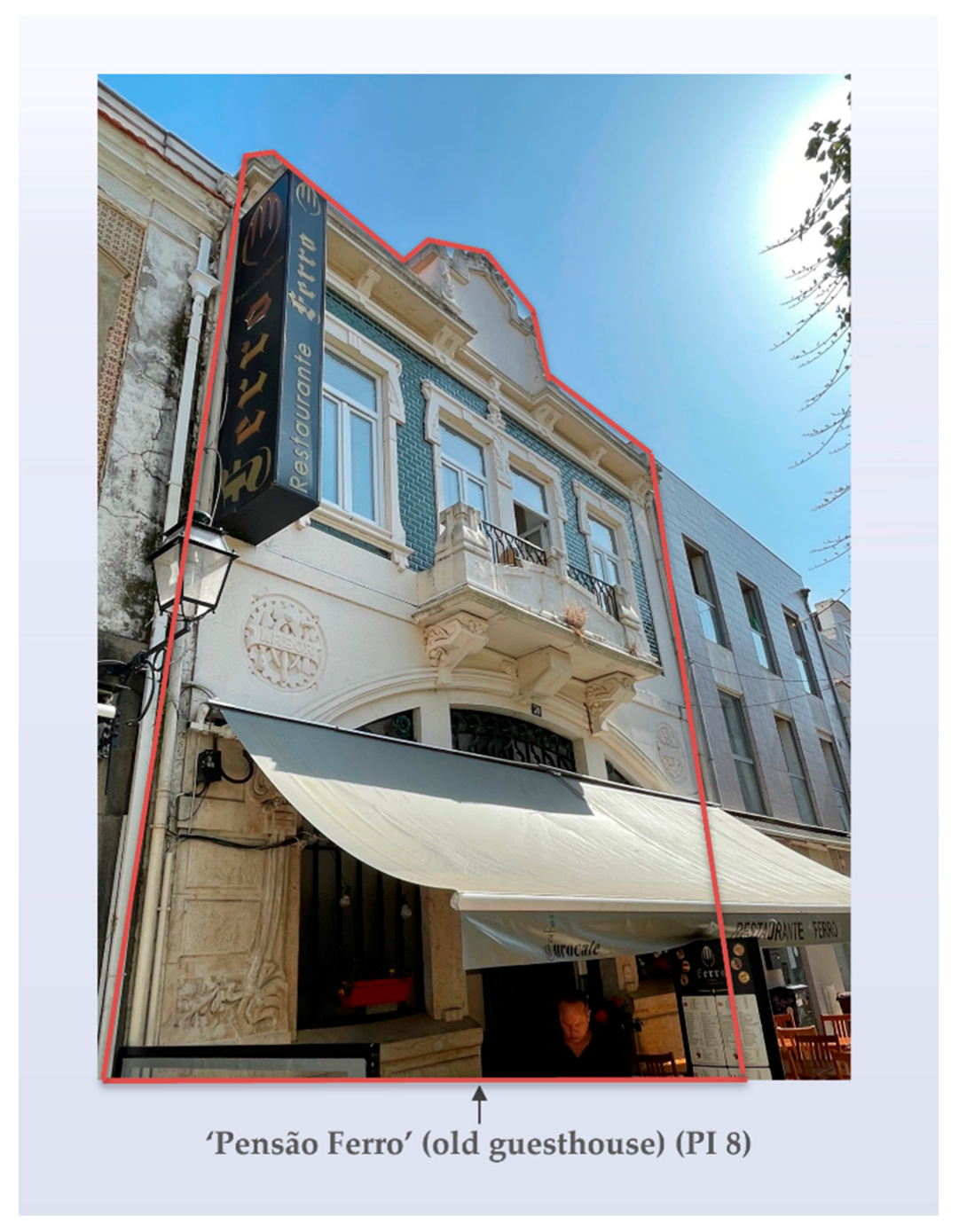

4.2. Attention to the Built Heritage and Architectural Details

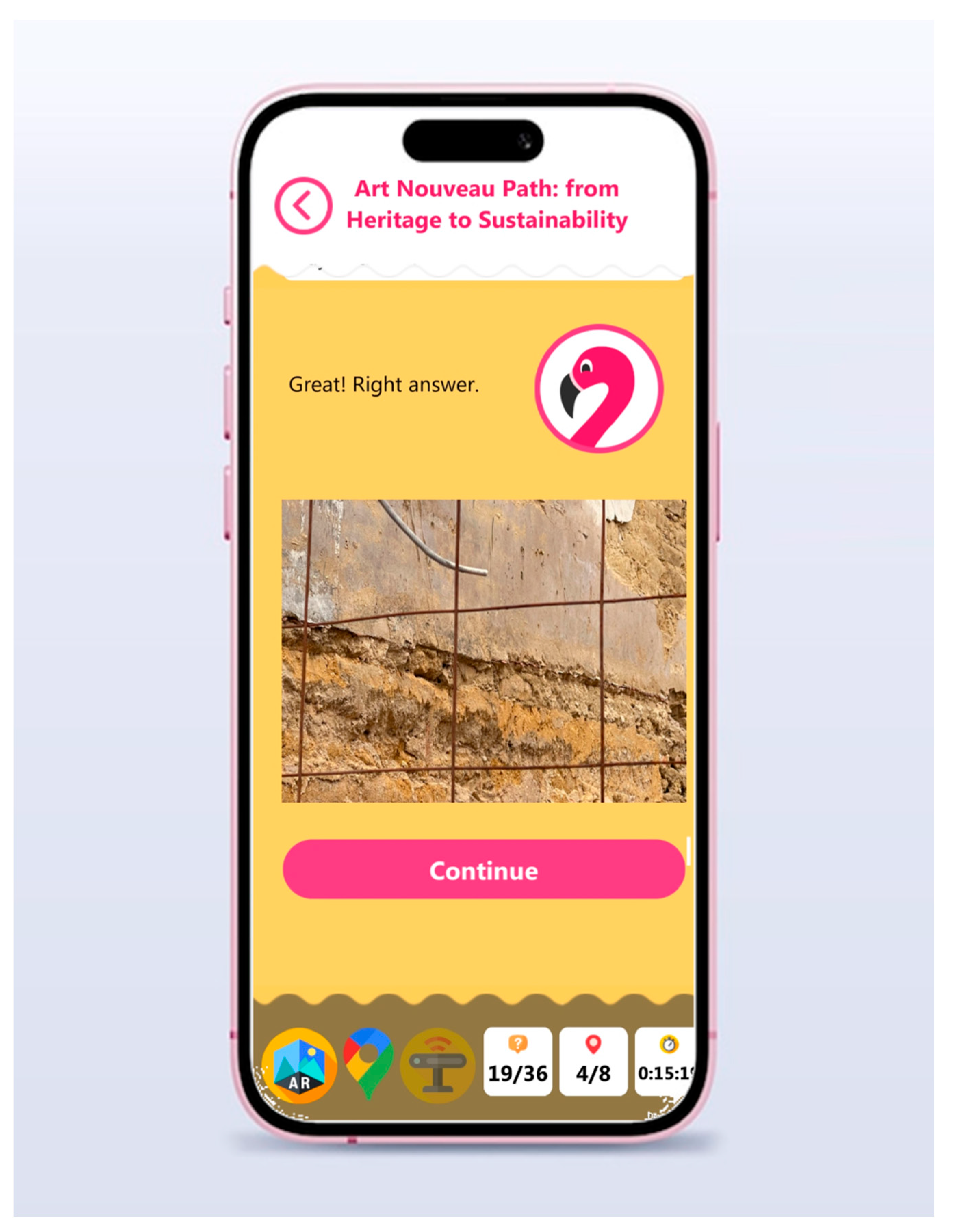

4.3. The Role of AR as a Catalyst for Interest

4.4. Spatial Trajectories and Urban Mobility

4.5. Critical Reflection on Sustainability and the City

4.6. Curriculum Validation by Teachers (T1-R)

5. Discussion of the Art Nouveau Path Findings

5.1. Location-Based MARGs as Sources of Geoinformation

5.2. AR as a Cartographic Interface

5.3. Conceptual Integration and Competence Orientation

5.4. Teachers’ Validation and Curricular Relevance

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Findings

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Future Work

6.4. Final Reflection

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| LBS | Location-Based Services |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| MARG | Mobile Augmented Reality Game |

| PI | Point of Interest |

| RQ | Research Question |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| GIScience | Geographic Information Science |

| CIDOC-CRM | International Committee for Documentation of the International Council of Museums Conceptual Reference Model |

| RANN | Réseau Art Nouveau Network |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| DBR | Design-based Research |

Appendix A

| Category | N | Reference | Author(s) (Year) | Central use in the paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Peer-reviewed Articles Peer-reviewed articles |

[1] ** | Hosagrahar et al. (2016) | Sec. 1, 2.5 – heritage & SDGs | |

| [3] ** | Lerario (2022) | Sec. 2.5 – heritage & SDGs | ||

| [4] | Goodchild (2004) | Sec. 2.1 – GIScience foundations | ||

| [5] | Raubal (2020) | Sec. 2.5 – spatial data science | ||

| [6] | Long et al. (2025) | Sec. 2.2, 4 – movement analysis | ||

| [7] | Bekele et al. (2018) | Sec. 2.3 – AR/VR/MR in heritage | ||

| [8] ** | Ibáñez & Delgado-Kloos (2018) | Sec. 2.3 – AR in STEM | ||

| [9] ** | Ch’ng et al. (2023) | Sec. 2.3 – social AR | ||

| [10] | Zheng et al. (2014) | Sec. 2.5 – urban computing | ||

| [11] | Angelis et al. (2021) | Sec. 2.2 – semantic trajectories | ||

| [12] | Caquard & Cartwright (2014) | Sec. 2.4 – narrative cartography | ||

| [13] | Caquard (2013) | Sec. 2.4 – narrative cartography | ||

| [14] | Flotyński (2022) | Sec. 2.3 – XR modeling | ||

| [16] ** | Kleftodimos et al. (2023a) | Sec. 2.3 – Doltso AR app | ||

| [17] ** | Kleftodimos et al. (2023b) | Sec. 2.3 – Dispilio AR app | ||

| [18] * | Ferreira-Santos & Pombo (2025a) | Sec. 3.4 – GCQuest baseline | ||

| [19] * | Ferreira-Santos & Pombo (2025b) | Sec. 2.5, 3 – EduCITY DTLE | ||

| [20] ** | Siddaway et al. (2019) | Sec. 3.6 – systematic reviews | ||

| [21] ** | Thomas & Harden (2008) | Sec. 3.6 – thematic synthesis | ||

| [22] ** | Boyd (2024) | Sec. 3.6 – hybrid thematic analysis | ||

| [23] ** | Braun & Clarke (2003) | Sec. 3.6 – thematic analysis | ||

| [24] | Goodchild (2007) | Sec. 2.1 – volunteered geography | ||

| [25] | Garau (2014) | Sec. 2.5 – smart heritage | ||

| [2] | Garau (2015) | Sec. 2.5 – smart heritage | ||

| [28] | Burbules et al. (2020) | Sec. 2.5 – education & technology | ||

| [29] | Zhuang et al. (2017) | Sec. 2.5 – smart learning environments | ||

| [33] | Shoval & Isaacson (2007) | Sec. 2.2 – sequence alignment | ||

| [34] | Andrienko & Andrienko (2013) | Sec. 2.1 & 2.2 – trajectory analysis | ||

| [35] | Doerr (2003) | Sec. 2.2 – semantic interoperability | ||

| [36] | Dunleavy & Dede (2014) | Sec. 2.3 – AR heritage | ||

| [37] | Ibañez-Etxeberria et al. (2020) | Sec. 2.3 – AR in heritage education | ||

| [38] | Delgado-Rodríguez et al. (2023) | Sec. 2.3 – AR for STEAM | ||

| [39] | Nikolarakis & Koutsabasis (2024) | Sec. 2.3 – AR heritage | ||

| [40] | Boboc et al. (2022) | Sec. 2.3 – AR heritage overview | ||

| [41] | Liamruk et al. (2025) | Sec. 2.3 – AR serious game | ||

| [42] | Perkins (2008) | Sec. 2.3 – cultures of map use | ||

| [43] | Healy (2020) | Sec. 2.5 – belonging & education | ||

| [44] | Lampropoulos et al. (2023) | Sec. 2.3 – AR & gamification | ||

| [46] | Tousi et al. (2025) | Sec. 2.5 – smart heritage | ||

| [50] ** | Nocca (2017) | Sec. 2.5 – heritage indicators | ||

| [51] * | Marques et al. (2025) | Sec. 2.5 – smart learning city | ||

| [53] ** | Anderson & Shattuck (2012) | Sec. 3.1 – DBR framework | ||

| [55] ** | Cebrián et al. (2021) | Sec. 2.5 – ESD competences | ||

| [56] ** | Doorsselaere (2021) | Sec. 2.5 – heritage & SDGs | ||

| [60] ** | Boeve-de Pauw et al. (2014) | Sec. 2.5 – values & competences | ||

| [62] | Schoonenboom & Johnson (2017) | Sec. 3.6 – mixed methods | ||

|

Policy and institutional frameworks |

6 | [2] ** | UNESCO (2017) | Sec. 2.5 – ESD objectives |

| [15] ** | Bianchi et al. (2022) | Sec. 2.5, 4 – GreenComp | ||

| [27] ** | European Commission (2019) | Sec. 2.5 – Key competences | ||

| [47] ** | UN (2015) | Sec. 1, 2.5 – SDGs framing | ||

| [48] ** | UN (2016) | Sec. 2.5 – New Urban Agenda | ||

| [49] ** | CHARTER Alliance (2024) | Sec. 2.5 – heritage education | ||

| Books, Chapters, and monographs |

9 |

[59] | Neves (1997) | Sec. 2.4, 3.2 – local Art Nouveau |

| [58] | Greenhalgh (2000) | Sec. 2.4 – Art Nouveau context | ||

| [31] ** | Choay (2019) | Sec. 2.5 – heritage theory | ||

| [30] ** | Choay (2021) | Sec. 2.5 – heritage theory | ||

| [54] ** | Mckenney & Reeves | Sec. 3.1 – DBR framework | ||

| [57] | Curado (2019) | Sec. 3.2 – Aveiro’s urban fabric | ||

| [32] | Stavrides (2021) | Sec. 2.5 – urban commons | ||

| [45] | Tonwsend (2013) | Sec. 2.5 – smart learning city | ||

| [52] | Susanne & Thomas (2019) | Sec. 2.5 – history, space, place | ||

| Prior authors’ works | 3 | [18] * | Ferreira-Santos & Pombo (2025a) | Sec. 3.4 – GCQuest baseline |

| [19] * | Ferreira-Santos & Pombo (2025b) | Sec. 2.5, 3 – EduCITY DTLE | ||

| [51] * | Marques et al. (2025) | Sec. 2.5 – MARGs in smart city |

References

- J. Hosagrahar, J. Soule, L. Girard, and A. Potts. Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda. BDC. Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini 2016, 16, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development Goals: learning objectives. Paris: UNESCO 2017.

- A. Lerario. The Role of Built Heritage for Sustainable Development Goals : From Statement to Action. Heritage 2022, 5, 2444–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. F. Goodchild. GIScience, Geography, Form, and Process. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2004, 94, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Raubal. Spatial data science for sustainable mobility. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Long, U. Demšar, S. Dodge, and R. Weibel. Data-driven movement analysis. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. K. Bekele, R. Pierdicca, E. Frontoni, E. S. Malinverni, and J. Gain. A Survey of Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality for Cultural Heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. B. Ibáñez and C. Delgado-Kloos. Augmented reality for STEM learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2017, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Ch’ng, S. Cai, P. Feng, and D. Cheng. Social Augmented Reality: Communicating via Cultural Heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zheng, L. Capra, O. Wolfson, and H. Yang. Urban Computing. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2014, 5, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Angelis, K. Kotis, and D. Spiliotopoulos. Semantic Trajectory Analytics and Recommender Systems in Cultural Spaces. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2021, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Caquard and W. Cartwright. Narrative Cartography: From Mapping Stories to the Narrative of Maps and Mapping. Cartogr. J. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- S. Caquard. Cartography I. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Flotyński. Visual aspect-oriented modeling of explorable extended reality environments. Virtual Real. 2022, 26, 939–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Bianchi, U. Pisiotis, M. Cabrera, Y. Punie, and M. Bacigalupo, The European sustainability competence framework. 2022.

- A. Kleftodimos, A. Evagelou, A. Triantafyllidou, M. Grigoriou, and G. Lappas. Location-Based Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage Communication and Education: The Doltso District Application. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- A. Kleftodimos, M. Moustaka, and A. Evagelou. Location-Based Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage Education : Creating Educational, Gamified Location-Based AR Applications for the Prehistoric Lake Settlement of Dispilio. Digital 2023, 3, 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Ferreira-Santos and L. Pombo. The Art Nouveau Path: Promoting Sustainability Competences Through a Mobile Augmented Reality Game. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Ferreira-Santos and L. Pombo. The Art Nouveau Path: Integrating Cultural Heritage into a Mobile Augmented Reality Game to Promote Sustainability Competences Within a Digital Learning Ecosystem. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. P. Siddaway, A. M. Wood, and L. V. Hedges. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Thomas and A. Harden. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Boyd. Reasoning within Hybrid Thematic Analysis. LINK 2024, 8. [Google Scholar]

- V. Braun and V. Clarke. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2003, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. F. Goodchild. Citizens as sensors: the world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Garau. From Territory to Smartphone: Smart Fruition of Cultural Heritage for Dynamic Tourism Development. Plan. Pract. Res. 2014, 29, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Garau, F. Masala, and F. Pinna. Benchmarking Smart Urban Mobility: A Study on Italian Cities. 2015; 612–623.

- European Commision, Key competences for lifelong learning. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019.

- N. C. Burbules, G. Fan, and P. Repp. Five trends of education and technology in a sustainable future. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Zhuang, H. Fang, Y. Zhang, A. Lu, and R. Huang. Smart learning environments for a smart city: from the perspective of lifelong and lifewide learning. Smart Learn. Environ. 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Choay, As questões do Património. Edições 70, 2021.

- F. Choay, Alegoria do Património, 3rd ed. Edições 70, 2019.

- S. Stavrides, Espaço comum: A cidade como obra coletiva. Orfeu Negro, 2021.

- N. Shoval and M. Isaacson. Sequence Alignment as a Method for Human Activity Analysis in Space and Time. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2007, 97, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Andrienko and G. Andrienko. Visual analytics of movement: An overview of methods, tools and procedures. Inf. Vis. 2013; 24. [CrossRef]

- M. Doerr. The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Module an Ontological Approach to Semantic Interoperability of Metadata. AI Mag. 2003, 24, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- M. Dunleavy and C. Dede. Augmented Reality Teaching and Learning. in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, 4th ed., J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, and B. M. J., Eds. New York: Springer, 2014, 735–745.

- A. Ibañez-Etxeberria, C. J. Gómez-Carrasco, O. Fontal, and S. García-Ceballos. Virtual environments and augmented reality applied to heritage education. An evaluative study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- S. Delgado-Rodríguez, S. C. Domínguez, and R. Garcia-Fandino. Design, Development and Validation of an Educational Methodology Using Immersive Augmented Reality for STEAM Education. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2023, 12, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Nikolarakis and P. Koutsabasis. Mobile AR Interaction Design Patterns for Storytelling in Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. G. Boboc, E. Băutu, F. Gîrbacia, N. Popovici, and D.-M. Popovici. Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Liamruk, N. Onwong, K. Amornrat, A. Arayapipatkul, and K. Sipiyaruk. Development and evaluation of an augmented reality serious game to enhance 21st century skills in cultural tourism. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Perkins. Cultures of Map Use. Cartogr. J. 2008, 45, 150–158. [CrossRef]

- M. Healy. The Other Side of Belonging. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2020, 39, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Lampropoulos, E. Keramopoulos, K. Diamantaras, and G. Evangelidis. Integrating Augmented Reality, Gamification, and Serious Games in Computer Science Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Townsend, Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, And The Quest For A New Utopia. New York, NY, USA: W. W. NORTON & COMPANY, 2013.

- E. Tousi, S. Pancholi, M. M. Rashid, and C. K. Khoo. Integrating Cultural Heritage into Smart City Development Through Place Making: A Systematic Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). UN General Assembly, 2015. [CrossRef]

- UN, New urban Agenda. United Nations, 2016.

- CHARTER Alliance. Guidelines on innovative/emerging cultural heritage education and training paths. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://charter-alliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CHARTER-Alliance_Eight-innovative-and-emerging-cultural-heritage-education-and-training-pathways.pdf.

- F. Nocca. The role of cultural heritage in sustainable development: Multidimensional indicators as decision-making tool. Sustainability 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Marques, J. Ferreira-Santos, R. Rodrigues, and L. Pombo. Mobile Augmented Reality Games Towards Smart Learning City Environments: Learning About Sustainability. Computers 2025, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Susanne and T. Michael Thomas, History, Space, and Place. Routledge, 2019.

- T. Anderson and J. Shattuck. Design-Based Research. Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- S. Mckenney and T. Reeves. Education Design Research. in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology: Fourth Edition, 2014, 29.

- G. Cebrián, M. Junyent, and I. Mulà. Current practices and future pathways towards competencies in education for sustainable development. Sustain. 2021, 13, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Van Doorsselaere. Connecting sustainable development and heritage education? An analysis of the curriculum reform in Flemish public secondary schools. Sustain. 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. J. Curado, Evolução Urbana de Aveiro: Espaços e Bairros com origem entre os séculos XV e XIX. Sana Editora, 2019.

- P. Greenhalgh, (Ed.), Art Nouveau: 1890-1914. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2000.

- A. Neves, A Arte Nova em Aveiro e seu distrito. Aveiro: Câmara Municipal de Aveiro, 1997. [ISBN 972-9137-39-0].

- J. Boeve-de Pauw, K. Jacobs, and P. van Petegem. Gender Differences in Environmental Values: An Issue of Measurement? Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. W. Creswell and J. D. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2023.

- J. Schoonenboom and R. B. Johnson. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. Köln Z Soziol 2017, 69 (Suppl. S2), 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discipline | Curricular Relevance |

Interdisciplinary Potential | Critical/Reflective Emphasis | Age Appropriateness |

Sustainability Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Links to 9th grade and 11th grade | Bridges with Sciences (environmental changes) and Arts (aesthetic readings of facades) | Comparison of old vs. current photographs; reflection on memory, urban change, and heritage | Suitable for 3rd cycle; adaptable to secondary with research-based tasks | Anchors civic and political values (e.g., republican symbols) in local heritage |

| Natural Sciences | Connects with 8th grade (“Sustainability on Earth”) and topics of ecosystems, pollution, resources | Integrates biodiversity motifs with artistic facades; chemistry of acid rain on limestone | Reflection on human impact, resource management, conservation | Calibrated for 3rd cycle; scalable to secondary via case studies and environmental projects | Promotes ecological literacy and responsibility through heritage contexts |

| Visual Arts/Citizenship | Links to 3rd cycle Education Visual and secondary curricula in Drawing A/History of Arts | Combines artistic expression with history and sustainability debates | Civic reflection on “Who protects heritage?” and role of art in public space | Accessible for younger students; adaptable for secondary via design portfolios and urban intervention projects | Strengthens cultural identity, creativity, and civic responsibility |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).