1. Introduction

The ESD framework, as presented by organizations like UNESCO [

1], is fundamentally oriented towards empowering learners with the knowledge, competencies, values, and dispositions necessary to orchestrate sustainability transitions and fulfil Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This vision goes beyond content delivery, requiring the development of critical skills to engage with systemic complexity [

2,

3,

4]. Furthermore, the curriculum is meticulously structured to foster ethical standards and enable learners to address real-world challenges in a truly transformative approach [

5].

Together with this pedagogical transition, digital innovation has emerged as a significant catalyst for educational transformation, considering its potential to enhance accessibility, relevance, engagement, and inclusivity. Global reports and initiatives demonstrate that technology can improve learning outcomes, enable flexible delivery and promote equity in various contexts [

1,

6]. However, despite the concurrent rise of ESD and educational technology, the two remain insufficiently integrated in educational practice. This is evident in practice, with conventional approaches to sustainability education often being abstract and confined to the classroom, disconnected from students’ daily lives.

Although competence-oriented frameworks such as the European GreenComp [

2] have become important in defining the sustainability competences that learners require, they have not yet been widely implemented in digital, context-rich learning environments. This is particularly evident in attempts to encourage affective, inclusive and place-based sustainability learning among younger students [

7].

Mobile, location-based learning enhances student engagement, contextual awareness, and emotional connection to place [

8,

9,

10]. By anchoring learning in familiar environments, it promotes active and participatory experiences. Mobile Augmented Reality Games (MARGs) further this potential by turning urban spaces into interactive educational settings. When structured around meaningful narratives and game mechanics, MARGs have been shown to increase motivation, engagement, and knowledge retention [

11].

Cultural heritage provides a powerful context for sustainability education, offering an interdisciplinary lens that integrates ecological, aesthetic, social, and historical dimensions. Recent research advocates for embedding heritage sites into immersive ESD experiences [

12,

13]. Learning in authentic environments, through collaborative and inquiry-based methods, has been shown to foster engagement and develop sustainability competences [

14].

This study presents the

Art Nouveau Path, a MARG developed within the [Project] DTLE (project’s webpage), aimed at lower and upper secondary students. Implemented in [City]’s Art Nouveau district, it comprises 36 quiz-based tasks linked to eight heritage Points of Interest (PI). Each challenge connects sustainability themes with local heritage through multimodal and context-aware interactions.

Figure 1 presents the full path connecting the eight PI.

Integrating local built heritage into digital narratives, via AR and multimodal media, promotes sustainability awareness through storytelling. Each PI-specific challenge follows a narrative arc that encourages close observation of Art Nouveau architecture while fostering reflection on sustainability themes. The MARG is structured around the European GreenComp framework [

2] and aligned with national curricula and local history, enhancing its interdisciplinary value.

Developed within the [Project] Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem (DTLE), the

Art Nouveau Path exemplifies pedagogical innovation at the intersection of cultural heritage, ESD, and the SDGs. [Project] provides the digital infrastructure and authoring tools to create AR-based learning experiences that treat the city as a living classroom, fostering immersive, place-based learning [

15,

16].

Despite advances in educational AR and policy support for ESD, few empirical studies explore the intersection of heritage, mobile learning, AR, and competence-based approaches in real-world contexts [

17]. Moreover, existing methodologies rarely involve teachers in the co-design or validation of digital tools [

18,

19]. To address these gaps, this study applied a Design-Based Research (DBR) [

20,

21] approach to develop and validate the MARG.

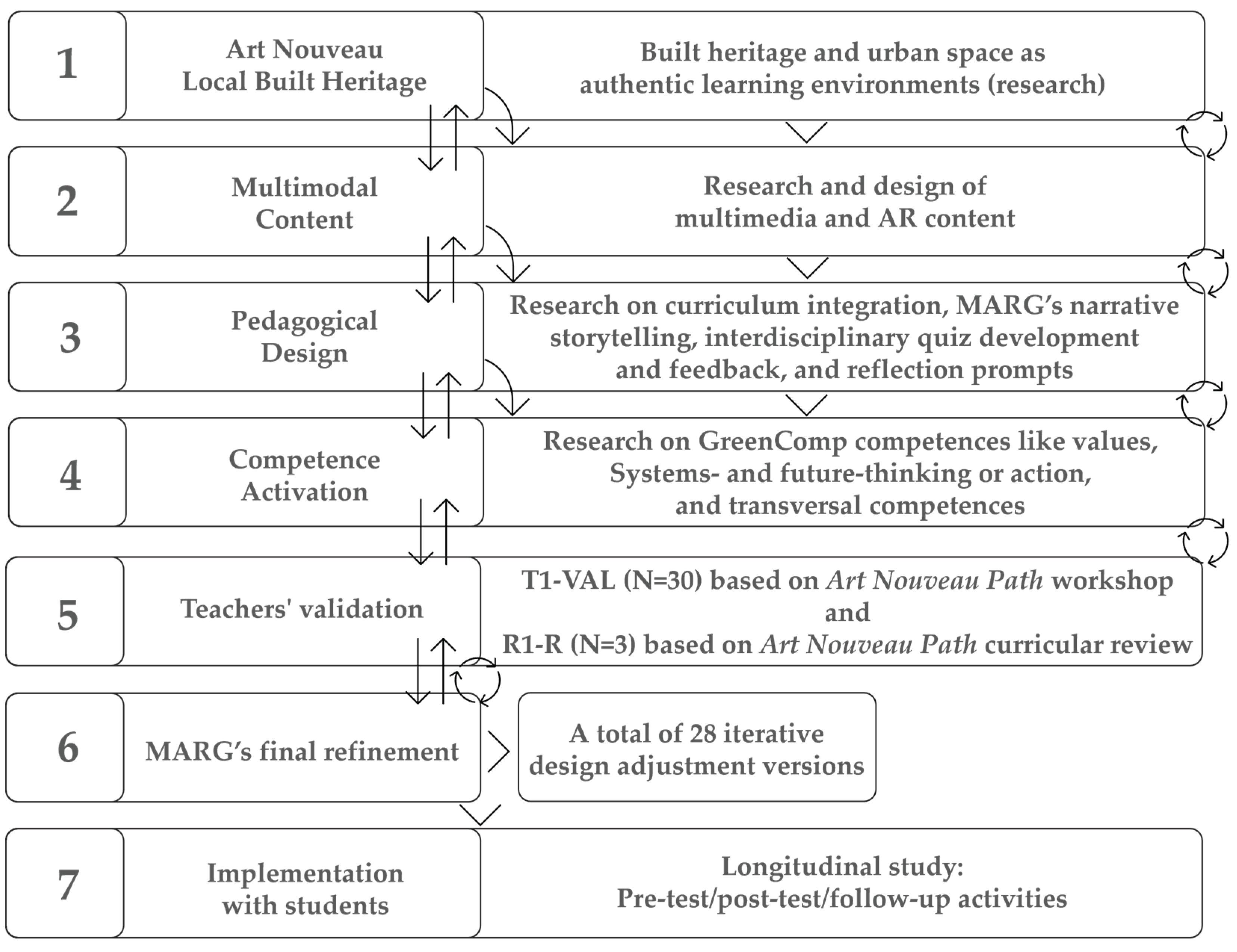

The design process involved iterative input from 30 in-service teachers (T1-VAL) and 3 other teachers, subject specialists (T1-R), whose feedback guided refinements. The intervention was then implemented with students in authentic settings.

As presented in

Figure 2, the design and implementation of the

Art Nouveau Path follows a multilayered pedagogical structure that consolidates heritage-based content, competence-driven learning strategies, and validated educational practices.

The overarching goal of the Art Nouveau Path is to establish a replicable model for inclusive and engaging ESD by integrating GreenComp sustainability competencies into a significant local heritage narrative. This approach aligns learning experiences with both local context and international policy frameworks.

The following research questions (RQ) were formulated to guide the study: (RQ1) How does the Art Nouveau Path MARG foster the activation of sustainability competences in students?; (RQ2) What are students’ perceptions of the MARG’s educational value, engagement, and usability in their urban environment?; and, (RQ3) What design and pedagogical insights emerge from applying the GreenComp framework and a design-based research approach in developing an inclusive, competence-oriented AR learning experience?

This study contributes to the field of digital education for sustainability along two axes: (1) by outlining the conceptual foundations and design principles of the Art Nouveau Path MARG; and (2) by detailing the DBR process and presenting initial empirical findings from its implementation. Results highlight the potential of combining MARGs and built heritage within DTLEs to foster inclusive, place-based, and competence-driven learning.

Following the introduction,

Section 2 presents a narrative thematic review of the literature and theoretical frameworks.

Section 3 describes the methodological design, including context, participants, instruments, and the DBR approach.

Section 4 reports findings from teacher validation (T1-VAL and T1-R) and the student diagnostic phase (S1-PRE).

Section 5 discusses the pedagogical and methodological implications of these results. The final section synthesizes key contributions, identifies limitations, and suggests paths for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section presents a narrative thematic literature review [

22,

23,

24], grounded in established procedures for thematic. The 17 studies were identified through multiple iterative searches combining terms such as

heritage,

ESD,

AR,

DTLE,

GreenComp, and

competences for sustainability. While Google Scholar was initially used for broader exploration, only articles indexed in Scopus and Web of Science were retained in the final corpus. The search strategy required multiple refinements, as certain keyword combinations, such as “Art Nouveau”, yielded thematically unrelated results. Notably, most studies linking

heritage and

sustainability competences tended to focus on conservation practices rather than on competence development through heritage-based learning

Building on this foundation, the corpus was analyzed using both inductive and deductive coding techniques [

29,

30] aligned with the study’s research questions. The resulting codes were then methodically organized into five intersecting domains of analysis: (1) ESD and SDG 4.7; (2) DTLEs; (3) AR and MARGs in game-based ESD learning; (4) GreenComp framework; and, (5) Built heritage as a place-based learning context, with a focus on [City]’s Art Nouveau heritage.

The five domains delineated here address fundamental theoretical and empirical gaps, thereby providing the conceptual framework for the MARG's pedagogical design.

The analysis corpus was complemented by six foundational frameworks:

the GreenComp framework for sustainability competences [

2];

UNESCO’s framework for Education for Sustainable Development [

1];

UNESCO’s roadmap for Education for Sustainable Development [

25];

DigComp 2.2 for digital competence [

26];

the ‘Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society’ [

27]; and,

the ‘Eight Innovative and Emerging Cultural Heritage Education and Training Pathways’ developed by the CHARTER Alliance [

28]

These documents were selected for their thematic relevance and methodological rigor. Together, they informed both the pedagogical design of the MARG and the analytical criteria of this study. Previous exploratory analyses of these documents ensured conceptual continuity throughout the MARG’s development.

Building on this foundation, all documents were analyzed using both inductive and deductive coding techniques [

29,

30] aligned with the study’s research questions. The resulting codes were then methodically organized into five intersecting domains of analysis: (1) ESD and SDG 4.7; (2) DTLEs; (3) AR and MARGs in game-based ESD learning; (4) GreenComp framework; and, (5) Built heritage as a place-based learning context, with a focus on [City]’s Art Nouveau heritage.

The five domains delineated here address fundamental theoretical and empirical gaps, thereby providing the conceptual framework for the MARG's pedagogical design.

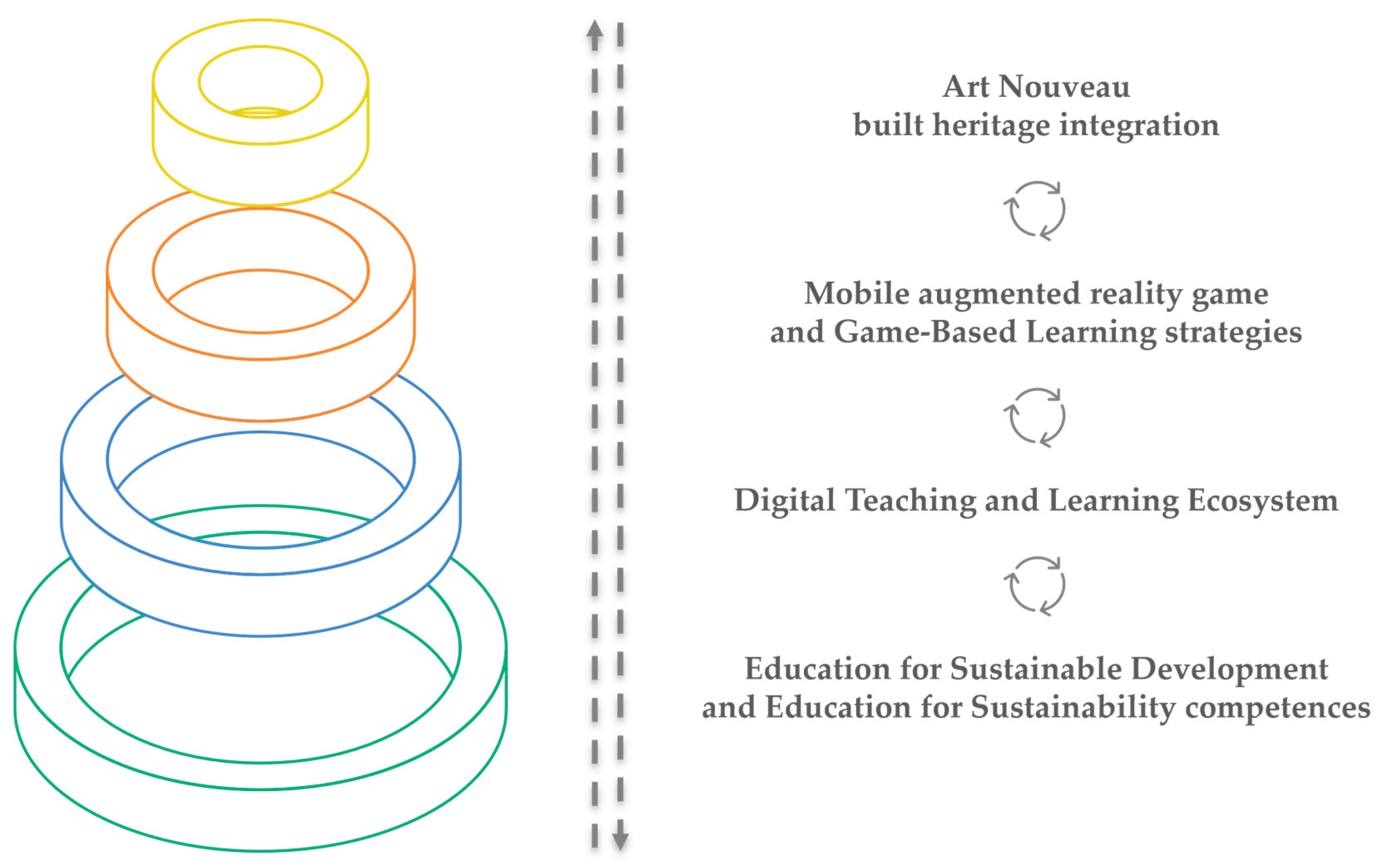

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the

Art Nouveau Path is situated at the intersection of these six layers, thereby establishing a nexus between global sustainability agendas and local cultural heritage.

To further structure the synthesis, three overarching conceptual strands were defined, aligned with the study's research questions: (1) Activation of sustainability competences through situated and digitally mediated learning (RQ1); (2) Students’ perceptions of educational value, usability, and engagement in mobile AR learning (RQ2); and, (3) Pedagogical design and validation of GreenComp-aligned AR learning using a DBR approach (RQ3).

The following subsections provide a comprehensive analysis of each of the five theoretical domains, while these strands offer transversal entry points for analysis and reflection.

2.1. ESD and SDG 4.7

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has become a key paradigm for promoting sustainability competences, as recognized in international frameworks such as UNESCO [

1,

25] and operationalized in the European GreenComp [

1,

2,

25]. Its core aim is to equip learners with Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes (KSA), conceived in GreenComp as a triadic model for sustainability competence development [

2].

As delineated in SDG 4.7 [

1], the concept of ESD extends beyond environmental literacy, encompassing global citizenship, social justice, and ethical responsibility. These concepts provide a foundation for a community-focused, value-driven educational system in both official and unofficial spheres, hence promoting the integration of sustainability competences into educational design and pedagogical strategies. Notwithstanding the substantial theoretical underpinnings of ESD, a persistent implementation gap persists. Numerous studies have noted that, while ESD is widely endorsed in terms of its importance, its concrete integration into curricula, pedagogical methods, and assessment systems is often fragmented [

31,

32,

33]. This gap is particularly pronounced when ESD is implemented through digital technologies, where emphasis often shifts towards technical skills at the expense of deeper transformative learning outcomes [

31,

34].

It is evident that certain educational interventions have sought to address this discrepancy by focusing ESD using arts, storytelling principles, or participatory projects [

32,

33]. While these approaches foster critical awareness and civic engagement, they rarely provide scalable models or robust frameworks for assessing competence development. Furthermore, although affective engagement and learner agency are frequently cited as objectives, few extant models explicitly link these outcomes to a framework like GreenComp [

2] or offer hints or mechanisms for validating sustainability competencies.

The present study makes a unique contribution to the extant literature by integrating the GreenComp framework with ESD principles within a game-based learning environment. The

Art Nouveau Path integrates GreenComp in two complementary ways: by offering an immersive, context-rich learning environment, and by employing a structured self-assessment tool (GCQuest) based on the 'Embodying Sustainability Values' domain [

35].

2.2. Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystems (DTLEs)

DTLEs are interconnected environments that integrate technological platforms, digital resources, pedagogical strategies, and human actors to support learning in dynamic, and adaptive ways [

26,

36].

DTLEs are explored here as a bridge between formal education and real-world complexity. They promote diverse, interconnected, and participatory modes of learning.

DTLEs, particularly when combined with mobile and AR technologies, have shown promise for educational innovation [

37,

38]. Yet, their success depends less on technological novelty and more on purposeful pedagogical design, teacher mediation, and curricular alignment [

31,

39]. The educational impact of a DTLE is contingent upon its underlying pedagogical design, the intervention of teachers, and alignment with explicit, adequate, and valuable curricular goals. Furthermore, while most reviewed works focus on the technical and motivational affordances of DTLEs, few studies explicitly examine how these ecosystems can cultivate sustainability competences [

31,

34].

The [Project] platform (project’s webpage) exemplifies a DTLE designed around ESD and place-based learning. It provides both a technical infrastructure and an authoring environment to develop AR experiences like the

Art Nouveau Path [

12]. [Project] also empowers teachers and communities to co-create mobile AR learning experiences, enhancing scalability and local adaptability across diverse urban contexts [

10,

37]. Also, the [Project] Project enables the creation and incorporation of AR and multimedia content into location-based learning experiences, empowering teachers, students and overall community to develop their own educational MARGs. The model's scalability across diverse urban contexts underscores its potential for transferability and adaptation to different geographical and social contexts.

Persistent challenges include infrastructural inequalities, limited teacher training, scarce interdisciplinary collaboration, and the undervaluation of mobile technologies in formal education [

38,

39]. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to ensure that competence frameworks such as GreenComp [

2] are not only referenced in theory but fully embedded in the design, implementation, and assessment processes of DTLEs.

The

Art Nouveau Path responds to these gaps by exemplifying a pedagogically grounded DTLE. Through GreenComp-aligned design and teacher-validated co-creation [

40], this MARG demonstrates how digital tools can support situated, competence-based learning. The integration of GreenComp-aligned learning into a gamified, mobile environment that is rooted in students' everyday surroundings has been demonstrated to be effective [

41]. The iterative co-design process, validated through teacher participation [

40], exemplifies how technology can be aligned with purposeful pedagogy to foster sustainability competences in context-rich educational settings.

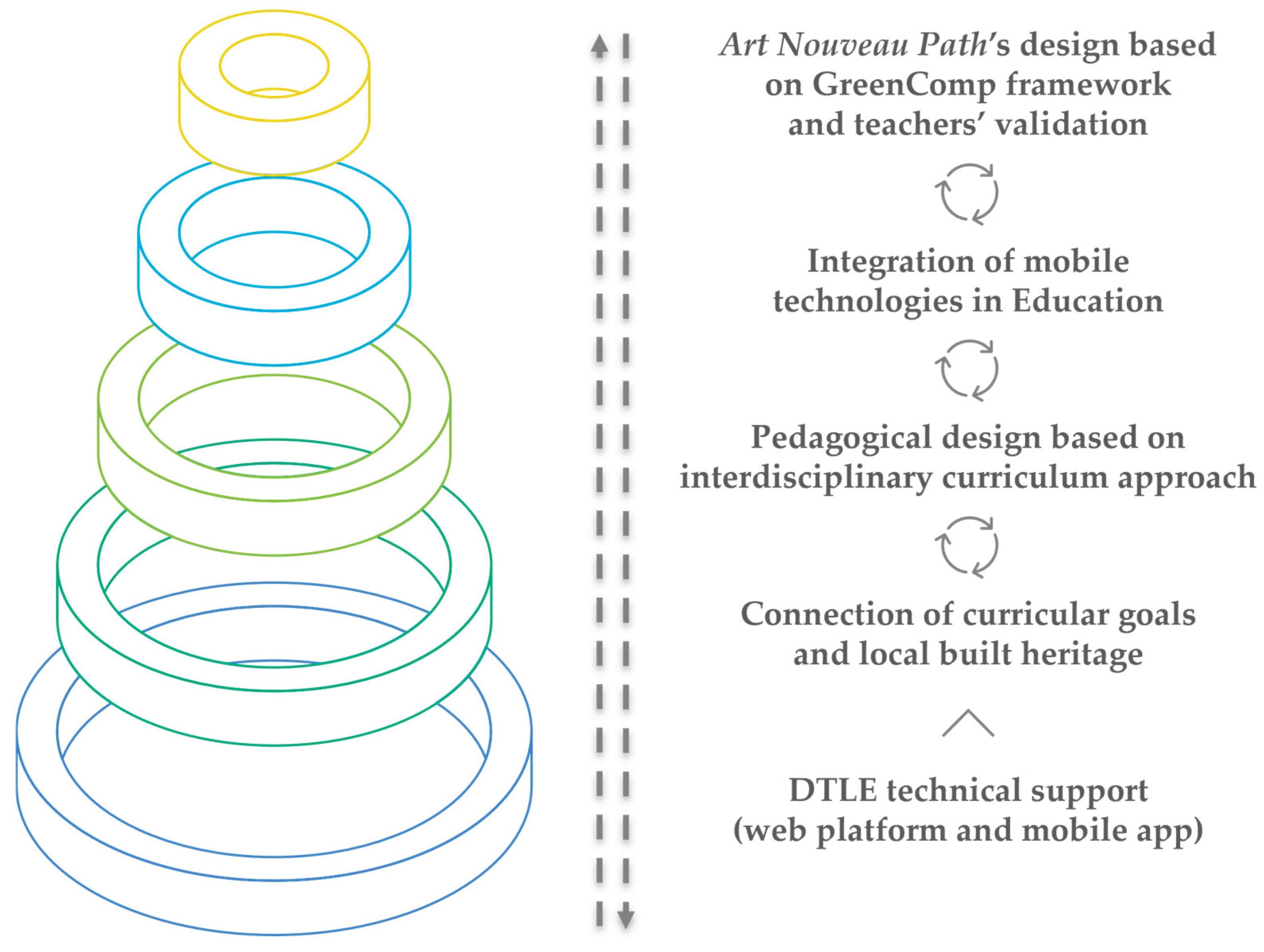

Figure 4 illustrates the integration of GreenComp [

2] within the

Art Nouveau Path, showing how co-design processes with teachers help bridge technical infrastructure with competence-based pedagogy in real-world contexts.

2.3. AR and Mobile Games in ESD

AR is increasingly recognized as a powerful tool in education, capable of fostering immersive, embodied, and context-sensitive learning experiences. The integration of digital information within physical environments, facilitated by AR, has been demonstrated to support the contextualization of abstract concepts and enhance the efficacy of educational activities. By embedding digital information in physical environments, AR enhances conceptual understanding and learner motivation [

42,

43,

44]. These affordances are particularly relevant to ESD, which calls for active participation, critical reflection, and systems thinking [

2].

Recent studies have documented a growing number of effective AR applications in education, such as enhanced textbooks, interactive museum experiences, and geolocated mobile games that encourage spatial exploration and storytelling [

10,

38,

45].

In the domain of sustainability education, AR is particularly appreciated for its potential to envision ecological processes, simulate future scenarios, and evoke emotional responses to global challenges [

31,

46,

47]. However, most educational uses of AR remain disconnected from formal competence frameworks such as GreenComp [

2]. While numerous studies have been published on the subject of "skills for sustainability" or "transformative learning" [

32,

33] few studies explicitly define the sustainability competences they aim to develop, hindering rigorous outcome evaluation. Furthermore, AR is often treated as an engaging add-on, rather than a pedagogically structured medium designed to activate targeted learning outcomes [

34,

45].

MARGs represent a promising format for ESD, combining multimodal interaction, gamification, and location-awareness to foster deep engagement and knowledge retention [

39,

46]. Game design elements, such as narrative progression, task-based challenges, and real-world spatial navigation, have been shown to promote learner agency and active participation.

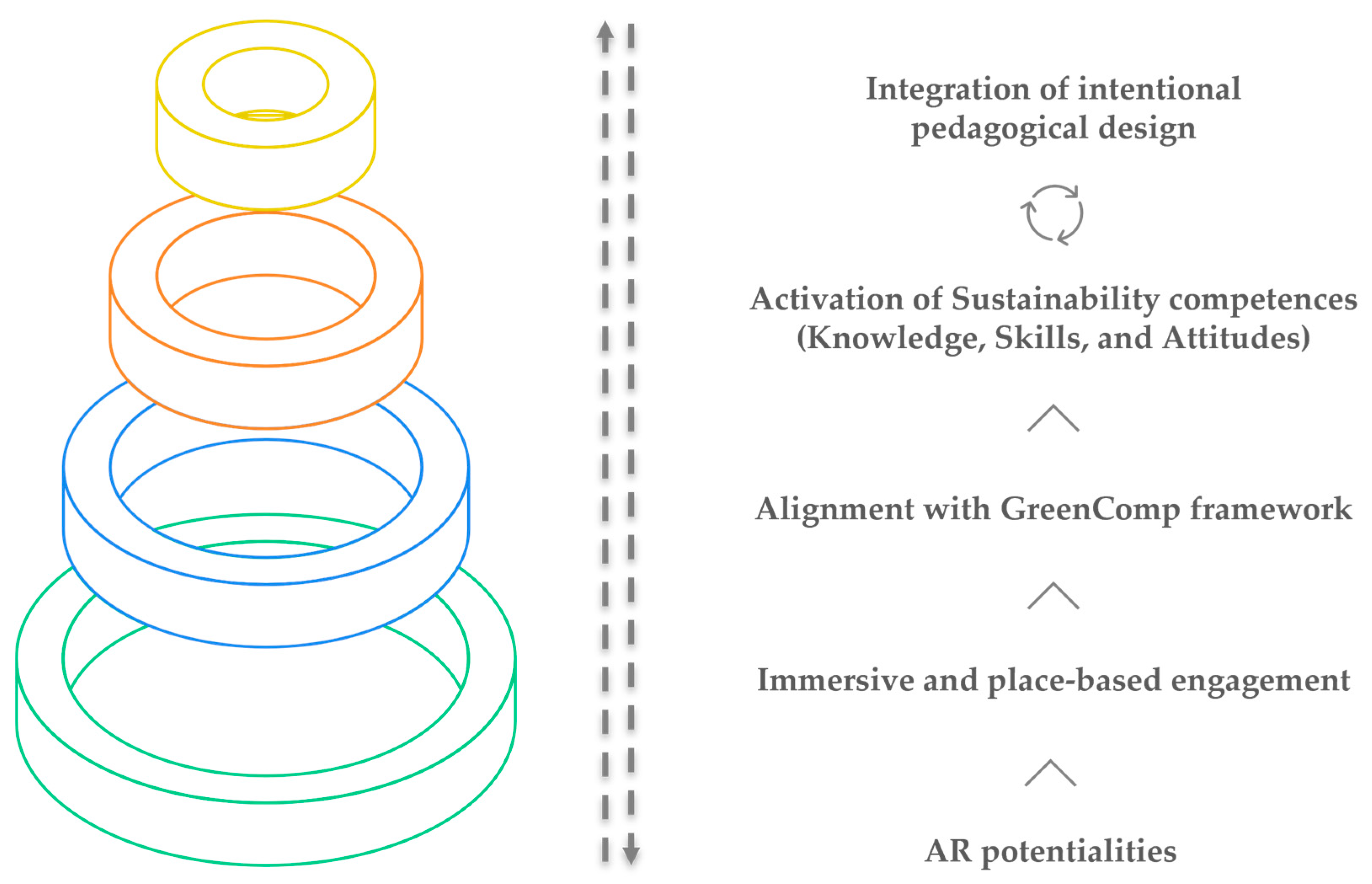

To illustrate the pedagogical distinction, the

HeritageSite AR project focused primarily on heritage appreciation and content delivery [

39]. In contrast, the

Art Nouveau Path was conceived from the outset as a GreenComp-aligned educational tool [

40]. As presented in

Figure 5, the

Art Nouveau Path leverages: (1) immersive, place-based engagement, (2) alignment with the GreenComp framework, (3) activation of Sustainability competences (Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes – KSA), and (4) integration of intentional pedagogical design.

Despite the increased visibility of AR in heritage education, many implementations continue to privilege visual immersion over pedagogical depth. For instance, the

EcoMOBILE project used AR and environmental sensors to facilitate outdoor science education [

48]. However, it exhibited a gap in terms of integration with broader sustainability competencies and teacher-led design [

48]. In a similar vein, Boboc and colleagues [

49] determined that most AR educational applications are technology-driven, exhibiting minimal alignment with structured learning frameworks such as GreenComp [

2].

The

Art Nouveau Path was designed to address these limitations. In contrast to conventional AR uses, this MARG is anchored in a clearly articulated competence framework, follows a rigorous DBR approach [

20,

21], and is situated within the lived context of [City]'s Art Nouveau heritage. In this MARG, AR is not merely a decorative element but rather an indispensable pedagogical medium that activates the emotional, intellectual, and behavioral dimensions of sustainability learning.

This MARG uses geolocated triggers, derived from the architectural details of each PI, in combination with 3D and AR overlays, integrated multimodal media, and narrative-quiz challenges. These components are designed to foster systems thinking, futures thinking, and values awareness. Its narrative, which is firmly rooted in specific locations, has been demonstrated to promote heightened emotional engagement and enhance long-term memory retention. These effects are critical for fostering sustainability dispositions [

50].

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of the unique features that set the

Art Nouveau Path apart from other AR-based educational projects. This comparison also clarifies how the

Art Nouveau Path advances the pedagogical integration of AR in ESD design

As summarized in

Table 1, the

Art Nouveau Path distinguishes itself by integrating geolocated architectural triggers, AR overlays, and multimodal narratives to activate GreenComp-aligned sustainability competences. Validated by teachers (T1-VAL and T1-R), it stands out as a replicable model bridging cultural heritage, digital innovation, and transformative ESD practice.

2.4. Designing for Sustainability: Operationalizing GreenComp in the Art Nouveau Path

The GreenComp framework [

2] provides a structured, multidimensional reference for embedding sustainability in education. It outlines twelve key competences across four interconnected domains: (1) ‘Embodying sustainability values’, (2) ‘Embracing complexity in sustainability’, (3) ‘Envisioning sustainable futures’, and (4) ‘Acting for sustainability’.

Despite policy endorsement, many ESD initiatives remain fragmented or declarative [

16]. The challenge lies not in defining sustainability competences, but in embedding them meaningfully in pedagogical practice, curricula, and assessment. It calls for participatory, reflexive, and real-world-anchored pedagogical approaches. Their work suggests that KSAs should not be viewed as distinct dimensions but rather as interconnected elements of learning that empower learners to meaningfully address sustainability challenges. In a subsequent study, the same authors emphasize that, despite growing policy endorsement of competence-based ESD, many initiatives remain fragmented or declarative in nature [

16]. Integrating sustainability competencies into curricula, teaching strategies, and assessments remains mostly aspirational.

While GreenComp has gained traction, few empirical studies offer concrete models for applying it in immersive DTLEs [

31,

39]. Laherto and colleagues [

51] argued that addressing the gap between policy and practice requires pedagogical models that operationalize all four GreenComp domains in integrated and meaningful ways.

The

Art Nouveau Path was designed to overcome these limitations. From its inception, this MARG was designed around the GreenComp framework, which served both as a conceptual foundation and as a guiding structure for the learning process. It was carefully designed to foster sustainability competences through reflection and decision-making in a familiar, real-world context. Each question is connected to one or more GreenComp domains [

2]. For instance, a question on water conservation addresses ‘

Acting for sustainability’; one on urban air quality reflects ‘

Embracing sustainability complexity’; and a prompt on built heritage connects to ‘

Embodying sustainability values’. These connections can occur in the same PI, as presented in

Figure 6.

The MARG's design is combined with a formative evaluation strategy based on an adapted version of the GCQuest instrument [

35]. This qualitative tailored version is specifically aligned with the

Art Nouveau Path and captures learners’ engagement with the

Embodying Sustainability Values domain, particularly through the interpretation of artistic and architectural elements. The instrument is administered at three moments, before gameplay GCQuest-S1PRE diagnostic (available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16540741), immediately afterward (S2-POST) and available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15919739, and again one to two months later (S3-FU), enabling insight into how participants perceive and reflect on sustainability values over time. As the responses were collected anonymously, a cross-sectional design was adopted, allowing for time-based analysis without respondent pairing. This paper presents a partial analysis focused on the GCQuest-S1PRE.

This design establishes a formative feedback loop in which learning tasks are explicitly mapped to GreenComp domains and revisited through structured self-assessment at three key moments (S1-PRE, S2-POST, S3-FU), fostering iterative reflection.

Figure 7 schematically illustrates the integration between pedagogical design and formative evaluation, showing how the GreenComp framework informs both the MARG’s structure and its assessment strategy, and how immersive gameplay and reflective practice are connected through this evaluation cycle.

The analysis presented in this paper focuses on data derived from the teacher validation stages (T1-VAL and T1-R), as well as on qualitative responses from the students’ pre-test phase (S1-PRE). These results are presented in the corresponding findings section.

The integration of the GCQuest directly responds to the need for assessment strategies that go beyond factual knowledge, focusing instead on the affective and dispositional dimensions of learning, aspects often neglected in formal evaluation [

31,

33]. By using GreenComp [

2] both as a creative scaffold and as an evaluative framework, the

Art Nouveau Path offers a concrete example of how digital learning environments can support meaningful, competence-oriented ESD. More than fulfilling curricular expectations, the MARG invites learners to engage with sustainability not only cognitively, but also ethically and emotionally, through a lens that is both local and future-facing.

This approach aligns with recent efforts such as the

OpenPass4Climate project (

https://openpass4climate.eu/), which also operationalizes the GreenComp framework [

2] through digital initiatives. This project proposes a system of digital credentials, the ‘climate badges’ that recognizes learners’ progress in specific sustainability competences, encouraging active engagement and providing structured feedback on individual action.

While

OpenPass4Climate adopts a distributed, credential-based logic, both initiatives exemplify how GreenComp [

2] can be used as a pedagogical anchor across diverse technological formats, from immersive AR experiences to micro-credential ecosystems.

2.5. Built Heritage as a Learning Platform for Sustainability

Cultural heritage has significant potential for EfS when considered as a context for meaningful, situated learning. From constructivist and sociocultural perspectives, heritage is not just a repository of the past, but also a living medium that supports identity formation, intergenerational dialogue, and civic responsibility [

52,

53]. This is reflected in policy documents such as the Faro Convention [

27], which highlights the importance of cultural heritage in promoting democratic participation, shared responsibility, and social cohesion. It posits that heritage is not only an object of preservation but also a catalyst for community-based action and reflective engagement with contemporary challenges.

Research in EfS has demonstrated that heritage sites can promote critical reflection on human-environment relations, historical continuity, and the ethical implications of conservation, use, and reuse [

54,

55,

56,

57]. However, prevailing practices often lack conceptual coherence. The integration of heritage into formal education frequently occurs solely at the level of content transmission, with limited attention to its potential to foster sustainability competences, such as systems thinking, futures literacy, or values-based action [

32,

33]. In recent years, digital technologies have been increasingly used to revitalize heritage-based learning. MARGs have demonstrated efficacy in enhancing affective engagement and facilitating embodied, multimodal interactions with historical environments [

39,

45]. Projects such as

HeritageSite AR and

[Project] demonstrated the potential of digital tools to bring architectural narratives, local histories, and urban transformation processes, often incorporating gamification and storytelling to enhance learning outcomes [

10,

34].

Most existing strategies fail to explicitly connect heritage education with established sustainability competence frameworks, such as GreenComp [

2]. Although learners might gain insights into significant cultural sites or methods of preserving the environment, they seldom find encouragement to link this understanding with larger themes of social equity, ecological sustainability, or responsibilities across generations. Few initiatives propose structured pedagogical models that illustrate how heritage can function as a framework for developing sustainability competences.

The

Art Nouveau Path addresses this challenge by positioning built heritage not merely as transmissible content, but as a dynamic learning environment, an active space for exploring sustainability issues through place-responsive pedagogy [

27,

58]. Each PI functions as a learning node where architectural elements are reinterpreted through sustainability lenses. In the

Art Nouveau Path, heritage functions as a foundational framework for systems thinking and futures thinking, two sustainability domains that are often difficult to convey in conventional educational settings [

59]. As demonstrated in

Figure 8, the

Art Nouveau Path functions as a catalyst for sustainability learning, integrating emotional engagement, cognitive challenge, and spatial exploration [

31,

60].

The

Art Nouveau Path fosters a model of contextualized citizenship, grounded in personal competence and agency. As learners navigate the urban landscape and reinterpret its cultural markers through a sustainability lens, they are invited to consider their own agency within broader ecological and societal systems. This approach supports a transformative vision of heritage education that frames it as a participatory, future-oriented process [

32,

51,

60,

61].

3. Materials and Methods

This study presents an exploratory case study methodology [

62,

63] within a DBR approach [

20,

21]. The

Art Nouveau Path was conceived and implemented as part of the [Project] DTLE, a research and development initiative hosted at the University of City (Country). [Project] explores the integration of MARGs into urban educational settings to advance EDS. Within this context, the

Art Nouveau Path functions as a place-based learning intervention, inviting students to engage with the city's Art Nouveau architectural heritage as both a "living classroom" and an experiential laboratory for sustainability learning.

3.1. Study Context and Intervention

The Art Nouveau Path MARG was developed between 2023 and 2024 as a research outcome of a doctoral project. The project's iterative design process entailed fieldwork on [City]'s Art Nouveau built heritage and the creation of digital assets, including 3D models, AR elements triggered by architectural features, and integrated multimedia narratives.

In this MARG, participants progress through a series of 36 quiz-type questions. Every question is defined by a uniform structure, which is outlined as follows: an introduction, a multiple-choice question containing four potential answers, and immediate feedback indicating correctness and providing rationale. The 36 quiz-type questions are geolocated at eight key Art Nouveau PIs within [City]'s historic city center. At each PI, the MARG delivers a blend of curated narrative prompts and multimedia content, including historical photographs, original and contextualized videos, and audio recordings. These are designed to trigger students' curiosity, spatial awareness, and critical reflection. The integration of these different contents is presented in

Figure 9.

Each quiz challenge was meticulously designed to vary in cognitive demand, ranging from ‘Remember’ to ‘Evaluate’ levels according to Bloom's revised taxonomy [

64]. All tasks were designed to integrate curriculum-relevant content with key themes in sustainability education. In this MARG students navigate eight Art Nouveau built heritage PIs, where architectural details such as tile panels, ironwork, or floral motifs serve as AR markers. These markers trigger interactive digital content, referred to as "ARBooks" or "Augmented Markers", which activate layered narratives and multimedia experiences, as illustrated in

Figure 10.

The narrative at each PI is augmented through the inclusion of historical imagery, original video and audio content, which together nurture a hybrid learning environment that intertwines factual data with interpretative reasoning. For instance, the analysis of decorative details or architectural functions is used as a catalyst for profound reflection on themes such as resource consumption, environmental stewardship, and sustainability values.

The MARG's design is conducive to high levels of learner engagement and situated learning, which is promoted by encouraging real-world exploration and complemented by digitally mediated heritage narratives. This combination cultivates a significant connection between students and their belonging urban environment, framing the city not merely as a passive setting but also as a dynamic contributor to educational experience [

65].

3.2. Participants and Procedures

The study involved two main participant groups: teachers and students. All procedures complied with the General Data Protection Regulation and the University of [City]’s ethical guidelines. Participation was entirely voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from teachers, and from students with additional parental authorization. No personally identifiable information was collected.

3.2.1. Teacher Validation (Phase T1)

In late 2024, a validation workshop was conducted with 30 in-service teachers (17 female, 13 male) from the central region of [Country], from various curricular areas, such as History, Geography, Arts, Natural Sciences, Mathematics, and Citizenship. Participants were recruited via a teacher-training initiative and engaged in a simulated classroom experience of the Art Nouveau Path MARG. Considering the weather conditions, the outdoor activity was replaced with an indoor session using printed AR markers and a prototype version of the [Project] mobile app. Participants were divided into small groups, replicating the collaborative dynamics experienced by students during gameplay. The mobile devices used were the same [Project] project smartphones employed in student sessions, ensuring full alignment with the original learning conditions. This arrangement enabled a faithful simulation of the MARG experience in an indoor setting.

Following the MARG, all teachers completed a mixed-format questionnaire (T1-VAL) composed of Likert-scale items, binary-response questions, and open-ended prompts. The aim of the questionnaire was to assess pedagogical value, usability, and curricular relevance. This instrument was developed based on validated instruments used in previous studies [

66,

67] (available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15916129).

Concurrently, a curricular review (T1-R) was undertaken by three teachers from different subject areas (History, Natural Sciences, and Arts/Citizenship). A structured rubric was utilized to validate the MARG's alignment with national curricular standards and its contribution to ESD (available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15917417). The evaluation process focused on interdisciplinary coherence and pedagogical robustness

3.2.2. Students’ Implementations (Phases S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU)

The students implementation followed three phases: (1) Prior to gameplay, 221 students (age range 13 to 18 years old) from lower and upper secondary education completed the GCQuest-S1PRE diagnostic (available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16540741), which assessed their initial conceptions of sustainability and readiness for AR-mediated heritage learning; (2) Immediately after gameplay, over 400 students completed the GCQuest-S2POST to assess short-term impact (not analyzed in this paper); and, (3) One to two months later, students completed the GCQuest-S3FU to evaluate knowledge retention and sustained engagement with sustainability values. A full analysis of the three questionnaires datasets will be addressed in subsequent publications.

During the S2-POST phase, 24 accompanying teachers completed the T2-OBS observation questionnaire, which evaluated students' engagement, the use of AR, and the pedagogical relevance of the MARG in real conditions (available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16540603).

The data collection process across all phases of the study followed a quasi-longitudinal structure, employing anonymous, independent cross-sectional samples. This approach enabled temporal comparisons while circumventing the necessity for individually matched data.

3.3. Data Collection Instruments

Multiple instruments were used to collect data from both teachers (

Table 2) and students (

Table 3), allowing triangulation consistent with the DBR framework.

The T1-VAL questionnaire was designed to elicit both quantitative and qualitative feedback. The curricular reviewers accessed all MARG materials to evaluate alignment with learning outcomes. The T1-R rubric focused on six key dimensions: (1) alignment with curricular goals, (2) interdisciplinary articulation across subjects, (3) promotion of critical thinking and reflection, (4) development of observation and analysis skills, (5) application of subject-specific competences, and (6) age-appropriateness for lower and upper secondary students.

The T2-OBS instrument was used during implementation to document learning dynamics and student engagement with AR.

Student data (

Table 3) were collected using an adapted version of the GCQuest questionnaire, grounded in the GreenComp framework with emphasis on the ‘

Embodying Sustainability Values’ domain. Besides open-end questions, the instrument presents a scale comprising 25 items, which were evaluated on a six-point Likert scale. The midpoint was deliberately excluded to encourage more decisive responses [

68]. The questionnaire was administered in Portuguese, with each session lasting approximately 20 minutes. The items were contextualized to reflect the themes and experiences of the

Art Nouveau Path MARG, ensuring content validity and relevance to the educational intervention.

This work focuses on two components of the study. First, the qualitative findings from the teacher validation phase (T1-VAL), which complement previously published T1-R and quantitative results [

40]. Second, the baseline diagnostic data collected from students (S1-PRE), prior to gameplay.

3.4. Data Analysis

The study used a mixed-methods analytical framework to integrate quantitative and qualitative insights. Quantitative data from T1-VAL were analyzed using descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and frequencies), as reported in another published work [

40]. Yes/no items from the student diagnostic (Section A) were summarized using both absolute and relative frequencies.

Thematic analysis was conducted on the open-ended response [

29,

30], following a six-phase coding process. Teacher responses from T1-VAL were thematically categorized under themes such as engagement, pedagogical effectiveness, and improvement suggestions. T1-R data were triangulated to verify curricular alignment with GreenComp [

2] and ESD objectives [

1,

25].Student responses to questions such as ‘

For me, sustainability is…’ were thematically coded, revealing subthemes such as environmental preservation, resource responsibility, and social equity. Further responses were collected to assess the respondents' existing knowledge of Art Nouveau heritage and their digital readiness.

Triangulating these analyses enabled a comprehensive evaluation of students' sustainability orientations and their receptiveness to digital heritage learning. This article presents two main data sources: (1) qualitative findings from teacher validation (T1-VAL and T1-R), and (2) baseline student data from the GCQuest-S1PRE diagnostic.

Although elements of the teacher validation were reported in previous work [

40], this study expands on those findings by offering a comprehensive interpretation of students' initial insights triangulated with teachers’ validation (T1-VAL and T1-R). The remaining datasets (T2-OBS, GCQuest-S2POST, GCQuest-S3FU) will be reported in subsequent publications, thus ensuring analytical depth and avoiding redundancy.

4. Findings: From Teachers’ Validation to Students’ Diagnosis Insights

This section presents the key empirical findings of the study, structured around two complementary perspectives: (1) teacher validation during the design and pilot phase (T1-VAL and T1-R), and (2) baseline diagnostic data from students (S1-PRE). Together, these findings offer a comprehensive overview of the MARG's educational relevance, its alignment with sustainability competences, and its potential to foster engagement in DTLEs.

4.1. Results from T1-VAL

A total of 30 in-service teachers from diverse subject areas, including History, Visual Arts, Natural Sciences, Geography, and Citizenship, participated in a structured workshop to validate the

Art Nouveau Path MARG. Quantitative results from the T1-VAL questionnaire revealed highly positive evaluations, with mean scores of approximately 5.60/6 for emotional and motivational engagement, 5.43/6 for curricular relevance, and 5.44/6 for overall educational value. Teachers noted that the MARG has strong potential to foster systems thinking and place-based learning. The AR features were particularly praised for encouraging new perspectives on urban environments and enhancing observational literacy. A more detailed statistical analysis is presented in a separate publication [

40].

4.1.1. Thematic Analysis of Teacher Feedback

A reflexive thematic analysis [

29,

30] of open-ended responses identified five core themes, summarized in

Table 4. These themes provide valuable criteria for evaluating the educational impact of the initiative: (1) Engagement and Motivation, (2) Visual Design and Pedagogical Relevance, (3) Augmented Reality and Technological Integration, (4) Curriculum Integration and Interdisciplinarity, and (5) Sustainability and Reflective Thinking.

Considering that open-ended responses contained multiple ideas, units of meaning were often coded into more than one subtheme. It is important to note that the frequencies refer to the number of coded segments, not the number of individual respondents.

The most prevalent theme was Engagement and Motivation (N = 31), followed by Visual Design and Pedagogical Relevance (N=21) and Augmented Reality and Technological Integration (N=13). It is evident that curriculum connections (N=9) and sustainability awareness (N=8) were less frequent, yet still noteworthy. Teachers frequently indicated that the MARG achieved a balance between challenge and learning, stimulated student curiosity, and promoted interdisciplinary approaches. These insights directly informed design improvements, including the addition of onboarding tutorials for AR.

These results reinforce Art Nouveau Path multidisciplinary and motivational value, while also highlighting the importance of clearer sustainability framing in educational initiatives.

4.1.2. Curricular Review Analysis

Three teachers specializing in History, Natural Sciences, and Arts/Citizenship conducted a structured curricular review based on a six-dimension rubric: (1) Alignment with formal curricular goals; (2) Potential for interdisciplinary integration; (3) Promotion of critical thinking; (4) Development of observation and analytical competences; (5) Reinforcement of subject-specific knowledge; and, (6) Cognitive suitability and age-appropriateness for lower and upper secondary levels.

The review confirmed a strong interdisciplinary alignment between the MARG's content and multiple curricular domains. In History, the analysis highlighted recurring themes such as urban transformation and democratic ideals. In Natural Sciences, topics like sustainability, biodiversity, and pollution were addressed. In Arts and Citizenship, the MARG promoted aesthetic literacy, visual interpretation, and civic engagement. Teachers emphasized the MARG's potential to foster situated critical thinking and visual analysis, particularly through comparisons between historical and contemporary urban landscapes.

The curricular reviewing teachers also documented the MARG’s alignment with GreenComp, particularly within the domains of ‘

Embodying Sustainability Values’ and ‘

Envisioning Sustainable Futures’ [

2]. These observations validate the MARG's contribution to structured and competence-oriented ESD practices.

4.2. Students’ Baseline Analysis (S1-PRE Phase)

Prior to gameplay, 221 students completed the GCQuest-S1PRE diagnostic instrument. This phase aimed to assess students’ baseline perceptions of sustainability, awareness of heritage, and readiness for mobile AR learning. All responses were considered valid, as students completed the questionnaire individually, in a supervised setting, after informed consent procedures and immediately before the flash sustainability training session with each class. This ensured data completeness and internal consistency for this phase.

4.2.1. Sustainability Perceptions and Competence Awareness

Students responded to the open-ended prompt: “For me, sustainability is…” (Item A.1.1). Responses were segmented into distinct units of meaning and coded into five subthemes, as presented in

Table 5. The most frequent categories included: (1) Resource Management and Practices (N=139); (2) Environmental Preservation (N=135); (3) Intergenerational Responsibility (N=99); (4) Individual Ethical Actions (N=56); and, (6) No Response / Not Clear (N=18).

These findings reveal a dominant focus on practical ecological actions, with limited attention to systemic or abstract dimensions, underscoring the need for deeper conceptual framing in sustainability education.

Students also answered three binary-response questions related to sustainability competences (

Table 6).

While 73.3% considered them important and 61.1% expressed a desire to learn more, only 51.1% were able to identify any, reinforcing the need for explicit competence-based learning activities.

4.2.2. Art Nouveau Knowledge and Heritage Perceptions

In item A.3.1, students were asked to describe their understanding of Art Nouveau. Most (N = 123) identified it as a general historical or artistic style. Only 38 referred to its visual characteristics, and just three mentioned [City]’s local context, despite its recognized Art Nouveau built heritage, as presented in

Table 7.

This empirical evidence substantiates the significance of place-based pedagogical methodologies, which integrate geolocation, contextual cues, and visual support.

4.2.3. Attitudes Toward Heritage and Mobile Learning

Items A.3.2 to A.3.6 explored students’ interest in learning via mobile AR and heritage themes. Results were very positive: over 70% expressed interest in learning about sustainability through Art Nouveau, and 80.5% appreciated mobile learning in urban settings, as presented in

Table 8.

As presented in

Table 8, the data indicates that students have a predominantly favorable attitude towards mobile and heritage-based learning experiences. A significant majority of respondents expressed an interest in sustainability-related content from an Art Nouveau perspective (72.4%), as well as a desire to learn more about Art Nouveau buildings in [City] specifically (67.9%). This illustrates the educational effectiveness of local heritage as a meaningful framework for ESD. Notably, 79.6% of students reported finding the MARG theme engaging, and an even higher proportion (80.5%) expressed a preference for outdoor and mobile learning environments.

4.3. Integrated Interpretation and Design Implications

The integration of teacher validation and student assessment yielded valuable insights into both the strengths of the MARG and opportunities for iterative improvement. Teachers confirmed its pedagogical value and curricular alignment, while student feedback informed the refinement of the narrative structure and the explicit integration of sustainability competencies. Students’ limited knowledge of Art Nouveau and sustainability frameworks highlighted the need for contextualized content and a competence-based structure, framed by GreenComp [

2], in both the MARG and the GCQuest assessment.

This feedback cycle, which is characteristic of design-based research, enabled iterative refinement while preserving the MARG's educational integrity. Ultimately, the Art Nouveau Path emerges as a contextualized, theoretically grounded MARG that effectively supports competence-based ESD through experiential, multimodal learning.

5. Findings: From Teachers’ Validation to Students’ Diagnosis Insights

This study demonstrates the pedagogical effectiveness of the

Art Nouveau Path MARG in promoting sustainability competences through culturally rooted, immersive, and engaging educational experiences. The results confirm the MARG's alignment with the GreenComp framework [

2] and emphasize its potential as a transformative learning tool within a DTLE.

The teacher validation phase (T1-VAL) highlighted the MARG's strong educational relevance and its capacity to generate emotional engagement among students. Thematic analysis of qualitative feedback revealed that teachers praised the integration of augmented content, the aesthetic coherence of the design and the MARG's ability to encourage engagement through location-based interaction. These features directly support the creation of transformative learning environments, as defined in the GreenComp [

2], which require emotionally engaging and contextualized learning scenarios [

25,

36].

The simultaneous curriculum review (T1-R) reinforced these findings, affirming the MARG's alignment with various disciplinary standards (History, Natural Sciences, Arts and Citizenship) and its resonance with GreenComp domains, such as 'Incorporating Sustainability Values' and 'Vision of Sustainable Futures'. Teachers also noted the value of MARG in promoting critical thinking, observational literacy, and interdisciplinary articulation.

Teachers’ feedback also revealed key implementation challenges. Concerns were raised about digital equity and students' readiness to use AR technology. These issues reflect wider systemic challenges in DTLEs [

41,

69]. In response, the design was adjusted iteratively to include integration mechanisms and gradual exposure to AR resources.

This adaptation process was guided by the principles of DBR [

20,

21] and ensured usability, inclusivity and pedagogical alignment. Student pre-test data (S1-PRE) provided a diagnostic snapshot of sustainability awareness and AR readiness. Most students associated sustainability with concrete ecological practices (e.g. recycling), while fewer articulated ethical or systems-based understandings.

These findings reaffirm the persistent limitations in fostering transversal sustainability competences [

3,

10,

70]. They also support existing literature that critiques the overemphasis on thematic content at the expense of integrated competence frameworks [

2].

The findings revealed a disconnect between students’ emotional investment in sustainability and their cognitive understanding of competence domains. While a notable 73.3% of respondents deemed these competencies to be significant, merely 51.1% were able to articulate any of them by name. This finding justifies the inclusion of an explicit GreenComp-based framework [

2] in the MARG's learning instructions, task structure, and assessment tools. The game architecture, which targets domains such as ‘

Embodying sustainability values’, ‘

Envisioning sustainable futures', and

'Acting for sustainability' [

2], directly addresses this gap.

Students' limited knowledge of Art Nouveau and its connection to [City]'s heritage further validates the need for contextual support and visual hints in the AR content. Conversely, there was strong enthusiasm for learning through heritage and mobile technologies.

Approximately 70% of participants expressed interest in exploring sustainable practices through the lens of Art Nouveau, with 80.5% favoring mobile learning formats. Nonetheless, merely 51.6% succeeded in differentiating between AR and VR, thereby underscoring the pressing necessity for enhanced support in cultivating foundational digital competencies within immersive educational frameworks [

42,

71,

72].

These integrated findings support the broader assertion that embedding cultural heritage meaningfully within DTLEs underpinned by competency frameworks, has the potential to enhance ESD. The

Art Nouveau Path highlights the integration of emotional investment, reflective questioning, and localized learning experiences, thereby advancing systemic reasoning and ethics-oriented teaching. Its design nurtures individual connections to urban environments and cultural identities, resonating with the principles of affective and holistic pedagogical approaches [

73,

74].

Moreover, the iterative co-evaluation process, combining teacher validation and student assessment, provided actionable insights that facilitated pedagogical enhancement. This adaptive, feedback-oriented strategy accentuates the essential role of participatory and adaptive design within DBR, especially concerning the assimilation of technology-enhanced methodologies into established educational frameworks.

More broadly, the Art Nouveau Path offers a replicable model for incorporating ESD into urban and cultural contexts while maintaining curriculum alignment and technological accessibility. Its narrative logic draws on the aesthetic coherence of Art Nouveau as ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, a 'total work of art', to promote cognitive and emotional cohesion. Simultaneously, it equips teachers to address socio-environmental challenges through creative and experiential pedagogical strategies.

By translating theoretical competence frameworks into immersive, emotionally resonant learning experiences, the

Art Nouveau Path responds to current calls in ESD frameworks for integrative methodologies that promote agency and value internalization, as well as future-oriented thinking [

2,

25].

As this study demonstrates, carefully designed MARGs can significantly advance the role of DTLEs in education for sustainability

6. Final Reflections, Limitations, and Future Path

This study presents the design, implementation, and preliminary findings from the evaluation of the Art Nouveau Path, a MARG developed within the [Project] DTLE to foster sustainability competences through heritage-based learning. Anchored in the GreenComp framework, the game combines affective engagement, spatial exploration, and multimodal interactivity to create transformative learning experiences in real urban environments.

Teacher validation (T1-VAL and T1-R) provided positive feedback on the game’s motivational appeal, interdisciplinary value, and curricular alignment. Teachers recognized that the

Art Nouveau Path value towards the connection of sustainability education with local cultural heritage, especially when mediated through immersive technologies. The game’s alignment with national curriculum goals, and its activation of key GreenComp dimensions, especially within the domains of

'Embodying sustainability values' and

'Envisioning sustainable futures' [

2], reinforce its relevance as a scalable, curriculum-compatible resource for ESD.

The baseline analysis (S1-PRE) offered insights into students' initial readiness for sustainability- and heritage-focused learning. While binary-response data revealed strong interest in outdoor and mobile AR experiences, thematic analysis of open-ended responses revealed limited familiarity with sustainability competencies and [City]’s Art Nouveau heritage. Although many students demonstrated value-driven attitudes and curiosity, only a minority could articulate specific competences or identify stylistic elements of local architecture.

Aligned with the GreenComp framework, the Art Nouveau Path prioritizes the ‘Embodying Sustainability Values’ domain while establishing foundations for transversal engagement with systems thinking, futures literacy, and collaborative action. Integrating AR into real-world environments contributes to expanding research on how digital tools situated within local cultural heritage can support ESD in engaging, inclusive and contextually relevant ways.

In addition to its practical insights, this research offers valuable theoretical and procedural viewpoints on crafting and assessing DTLEs that combine technological innovation with educational authenticity. The project also exemplifies how a DBR approach informed by teacher validation and diagnostic student data can shape the development of serious games that align with curricular frameworks such as GreenComp [

2], while remaining adaptable to diverse educational contexts.

This study has two main limitations. First, it adopts an exploratory case study methodology. Second, the student data analysis concerns only the pre-intervention phase (S1-PRE), which limits conclusions regarding long-term change. While the broader research project includes post-test and follow-up stages, this article focuses specifically on the diagnostic and validation components.

Future research will examine learning outcomes, emotional engagement, and long-term development of sustainability competences over the full implementation cycle, incorporating post-test and follow-up assessments. Longitudinal analyses are essential for understanding whether interventions like this can foster the internalization of sustainability values, behavioral change and systems thinking over time. Further research will explore adapting the Art Nouveau Path for different age groups, integrating more complex or collaborative challenges and conducting comparative studies between AR-based learning and analogue alternatives, such as board or card games. This will clarify the pedagogical benefits of augmented spatiality and multimodal interaction.

Exploring the scalability and cultural adaptability of the Art Nouveau Path, particularly its local context to different urban or heritage contexts, represents a valuable path for future research. Future design improvements might utilize inclusive co-design approaches, which would engage students as partners in creation to improve ownership, relevance, and educational impact.

The Art Nouveau Path ultimately exemplifies how MARGs grounded in cultural heritage can foster sustainability competences and enrich digital educational environments.

The Art Nouveau Path offers a compelling example of how MARGs rooted in cultural heritage can activate sustainability competences and enrich digital learning ecosystems. In the context of increasing emphasis on experiential, value-oriented and technologically mediated education, this MARG presents a pragmatic and scalable model that connects learners with their environments, communities and their future roles as agents of sustainable transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, (name initials); methodology, (name initials); validation, (name initials) and (name initials); formal analysis, (name initials); investigation, (name initials); resources, (name initials); data curation, (name initials); writing – original draft, (name initials); writing – review and editing, (name initials) and (name initials); visualization, (name initials); supervision, (name initials); project administration (name initials) and (name initials).

Funding

This work was funded by National Funds through the [Funding Agency], under Grant Number [Grant code], with the following DOI:

https://[PhD grant DOI]. The [Project] project is funded by National Funds through the [Funding Agency], under the project [Project’s funding code].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the GDPR (27 th November 2024), and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of [City] (protocol code 1-CE/2025 on 5 th February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of the research team of the [project] project in the development of its app and the web platform. The authors also appreciate the willingness of the participants to contribute to this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint (Microsoft 365), DeepL (DeepL Free Translator), and ChatGPT (GPT-3.5 Turbo) for the respective purposes of writing text, analyzing data, designing schemes, translation and text improvement, and checking for redundances. Quantitative data was analyzed with Excel (Microsoft 365). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESD |

Education for Sustainable Development |

| MARG |

Mobile Augmented Reality Game |

| DTLE |

Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| DBR |

Design-Based Research |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| PI |

Point of Interest |

| RQ |

Research Question |

| KSA |

Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes |

| GCQuest |

GreenComp-based Questionnaire |

References

- UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development Goals: learning objectives. Paris: UNESCO, 2017.

- G. Bianchi, U. Pisiotis, M. Cabrera, Y. Punie, and M. Bacigalupo, The European sustainability competence framework. 2022.

- A. Wiek, L. Withycombe, and C. Redman, “Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development,” Sustain. Sci., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 203–218, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Redman and A. Wiek, “Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability,” Front. Educ., vol. 6, no. November, pp. 1–11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Sterling, Sustainable education: re-visioning learning and change. Dartington: Green Books, 2001.

- B. Alcott et al., “Technology in education: A tool on whose terms?,” Paris, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Cebrián, M. Junyent, and I. Mulà, “Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development: Emerging Teaching and Research Developments,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 579, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [Removed for peer review].

- K. Mettis, T. Väljataga, and Õ. Uus, “Mobile Outdoor Learning Effect on Students’ Conceptual Change and Transformative Experience,” Technol. Knowl. Learn., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 705–726, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [Removed for peer review].

- A. Kleftodimos, M. Moustaka, and A. Evagelou, “Location-Based Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage Education : Creating Educational , Gamified Location-Based AR Applications for the Prehistoric Lake Settlement of Dispilio,” Digital, vol. 3, pp. 18–45, 2023. [CrossRef]

- [Removed for peer review].

- [Removed for peer review].

- Y. N. Demssie, H. J. A. Biemans, R. Wesselink, and M. Mulder, “Fostering students’ systems thinking competence for sustainability by using multiple real-world learning approaches,” Environ. Educ. Res., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 261–286, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [Removed for peer review].

- G. Cebrián, M. Junyent, and I. Mulà, “Current practices and future pathways towards competencies in education for sustainable development,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 16, p. 8733, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Ch’ng, S. Cai, P. Feng, and D. Cheng, “Social Augmented Reality: Communicating via Cultural Heritage,” J. Comput. Cult. Herit., vol. 16, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. De Freitas and S. Jarvis, “Serious games - engaging training solutions: A research and development project for supporting training needs,” Br. J. Educ. Technol., vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 523–525, 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Tobar-Muñoz, S. Baldiris, and R. Fabregat, “Co-Design of Augmented Reality Games for Learning with Teachers: A Methodological Approach,” Technol. Knowl. Learn., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 901–923, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Anderson and J. Shattuck, “Design-Based Research,” Educ. Res., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 16–25, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Mckenney and T. Reeves, “Education Design Research,” in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology: Fourth Edition, 2014, p. 29.

- Y. L. Goddard, L. Ammirante, and N. Jin, “A Thematic Review of Current Literature Examining Evidence-Based Practices and Inclusion,” Educ. Sci., vol. 12, no. 38, pp. 1–10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Siddaway, A. M. Wood, and L. V. Hedges, “How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses,” Annu. Rev. Psychol., vol. 70, pp. 747–770, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas and A. Harden, “Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews,” BMC Med. Res. Methodol., vol. 10, no. 45, pp. 1–10, 2008. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap. UNESCO, 2020.

- R. Vuorikari, S. Kluzer, and Y. Punie, DigComp 2.2, The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens - With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2022.

- Council of Europe, “Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society,” 2005. [CrossRef]

- CHARTER Alliance, “Guidelines on innovative/emerging cultural heritage education and training paths,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://charter-alliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CHARTER-Alliance_Eight-innovative-and-emerging-cultural-heritage-education-and-training-pathways.pdf.

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qual. Res. Psychol., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101, 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. Boyd, “Reasoning within Hybrid Thematic Analysis,” LINK, vol. 8, no. 2, 2024.

- V. Kioupi and N. Voulvoulis, “Education for Sustainable Development as the Catalyst for Local Transitions Toward the Sustainable Development Goals,” Front. Sustain., vol. 3, no. July, pp. 1–18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Lerario, “The Role of Built Heritage for Sustainable Development Goals : From Statement to Action,” Heritage, vol. 5, pp. 2444–2463, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Van Doorsselaere, “Connecting sustainable development and heritage education? An analysis of the curriculum reform in Flemish public secondary schools,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–17, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Ibañez-Etxeberria, C. J. Gómez-Carrasco, O. Fontal, and S. García-Ceballos, “Virtual environments and augmented reality applied to heritage education. An evaluative study,” Appl. Sci., vol. 10, no. 7, 2020. [CrossRef]

- [Removed for peer review].

- C. Redecker and Y. Punie, “European framework for the digital competence of educators - DigCompEdu,” Luxemburg, 2017.

- [Removed for peer review].

- S. Alhebaishi and R. Stone, “Augmented Reality in Education: Revolutionizing Teaching and Learning Practices – State-of-the-Art,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 23–36, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Xu, J. Liang, K. Shuai, Y. Li, and J. Yan, “HeritageSite AR: An Exploration Game for Quality Education and Sustainable Cultural Heritage,” in Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Apr. 2023, no. November, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- [Removed for peer review].

- S. A. Martínez-Ramos, J. Rodríguez-Reséndiz, A. F. Gutiérrez, P. Y. Sevilla-Camacho, and J. D. Mendiola-Santíbañez, “The learning space as support to sustainable development: A revision of uses and design processes,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 21, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Dunleavy and C. Dede, “Augmented Reality Teaching and Learning,” in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, 4th ed., J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, and B. M. J., Eds. New York: Springer, 2014, pp. 735–745.

- I. Radu, “Augmented reality in education: a meta-review and cross-media analysis,” Pers Ubiquit Comput, vol. 18, pp. 1533–1543, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Liang, Z. Zhang, and J. Guo, “The Effectiveness of Augmented Reality in Physical Sustainable Education on Learning Behaviour and Motivation,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 5062, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M.-T. Simón-Sánchez and M.-R. Fernández-Sánchez, “Tecnologías emergentes para el proyecto de educación digital:,” Educ. Knowl. Soc., vol. 24, p. e30613, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Ahdhianto, Y. K. Barus, and M. A. Thohir, “Augmented reality as a game changer in experiential learning: Exploring its role cultural education for elementary schools,” J. Pedagog. Res., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 296–313, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Olsson, N. Gericke, and J. Boeve-de Pauw, “The effectiveness of education for sustainable development revisited – a longitudinal study on secondary students’ action competence for sustainability,” Environ. Educ. Res., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 405–429, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Kamarainen et al., “EcoMOBILE: Integrating augmented reality and probeware with environmental education field trips,” Comput. Educ., vol. 68, pp. 545–556, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Boboc, E. Băutu, F. Gîrbacia, N. Popovici, and D.-M. Popovici, “Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications,” Appl. Sci., vol. 12, no. 19, p. 9859, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Pérez Ibarra, C. O. Tapia-Fonllem, B. S. Fraijo-Sing, N. Nieblas Soto, and L. Poggio, “Psychosocial Predispositions Towards Sustainability and Their Relationship with Environmental Identity,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 17, p. 7195, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Laherto, T. Rasa, L. Miani, O. Levrini, and S. Erduran, “Future-Oriented Science Education Building Sustainability Competences: An Approach to the European GreenComp Framework,” Sci. Curric. Anthr. Vol. 2, vol. 2, pp. 83–105, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Choay, As questões do Património. Edições 70, 2021.

- J. H. Falk and L. D. Dierkind, The Museum Experience. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- J. Hosagrahar, J. Soule, L. Girard, and A. Potts, “Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda,” BDC. Boll. Del Cent. Calza Bini, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 37–54, 2016. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, “Culture for Sustainable Development: Sustainable Cities.,” 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/culture-and-development/the-future-we-want-the-role-of-culture/sustainable-cities/.

- ICOMOS, “Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas,” 1987. [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS, “The Charter of Krakow 2000: principles for conservation and restoration of built heritage,” 2000. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-128776.

- Council of Europe, “European Charter of the Architectural Heritage,” 1975.

- C. Holtorf and A. Bolin, “Heritage futures: A conversation,” J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev., vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 252–265, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Zhang, Y. Gong, Q. Chen, X. Jin, Y. Mu, and Y. Lu, “Driving Innovation and Sustainable Development in Cultural Heritage Education Through Digital Transformation: The Role of Interactive Technologies,” Sustainability, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 314, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Smith, Uses of Heritage. Routledge, 2006.

- M. Barth and I. Thomas, “Synthesising case-study research - ready for the next step?,” Environ. Educ. Res., vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 751–764, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Yin, Case Study Research Design and Methods, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2015.

- L. Anderson et al., Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing, A: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Abridged Edition. Pearson, 2000.

- R. Zhuang, H. Fang, Y. Zhang, A. Lu, and R. Huang, “Smart learning environments for a smart city: from the perspective of lifelong and lifewide learning,” Smart Learn. Environ., vol. 4, no. 1, p. 6, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R.-J. Den Haan and M. C. Van der Voort, “On Evaluating Social Learning Outcomes of Serious Games to Collaboratively Address Sustainability Problems: A Literature Review,” Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 4529, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S.-J. Ho, Y.-S. Hsu, C.-H. Lai, F.-H. Chen, and M.-H. Yang, “Applying Game-Based Experiential Learning to Comprehensive Sustainable Development-Based Education,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 1172, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Cobern and B. Adams, “Establishing survey validity: A practical guide,” Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 404–419, 2020. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, “UNESCO strategy in technological innovation in Education (2022-2025),” Paris, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378847.

- J. Boeve-de Pauw and P. Van Petegem, “Because My Friends Insist or Because It Makes Sense? Adolescents’ Motivation towards the Environment,” Sustainability, vol. 9, no. 5, p. 750, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Ibáñez and C. Delgado-Kloos, “Augmented reality for STEM learning: A systematic review,” Comput. Educ., vol. 123, no. November 2017, pp. 109–123, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Klopfer, Augmented Learning. The MIT Press, 2008.

- P. Connerton, How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- F. Choay, Alegoria do Património, 3rd ed. Edições 70, 2019.

Figure 1.

Art Nouveau Path map in the [Project] app map (in-game screenshot, path, and 3 PI).

Figure 1.

Art Nouveau Path map in the [Project] app map (in-game screenshot, path, and 3 PI).

Figure 2.

Multilayered pedagogical model of the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 2.

Multilayered pedagogical model of the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 3.

Layered theoretical foundations of the Art Nouveau Path: From ESD to the integration of Built Heritage.

Figure 3.

Layered theoretical foundations of the Art Nouveau Path: From ESD to the integration of Built Heritage.

Figure 4.

Bridging DTLE to the Art Nouveau Path MARG design.

Figure 4.

Bridging DTLE to the Art Nouveau Path MARG design.

Figure 5.

Educational AR and GreenComp dimensions in the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 5.

Educational AR and GreenComp dimensions in the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 6.

Multiple questions mapped to distinct GreenComp domains within a single PI (‘Arcos Fountain’), demonstrating integrated pedagogical design logic.

Figure 6.

Multiple questions mapped to distinct GreenComp domains within a single PI (‘Arcos Fountain’), demonstrating integrated pedagogical design logic.

Figure 7.

Formative self-assessment cycle linking the GreenComp, the Art Nouveau Path, and the adapted GCQuest across three key moments (S1-PRE, S2-POST, S3-FU).

Figure 7.

Formative self-assessment cycle linking the GreenComp, the Art Nouveau Path, and the adapted GCQuest across three key moments (S1-PRE, S2-POST, S3-FU).

Figure 8.

[City]’s Art Nouveau heritage exploited as AR learning hub to activate GreenComp competences.

Figure 8.

[City]’s Art Nouveau heritage exploited as AR learning hub to activate GreenComp competences.

Figure 9.

Integration of multimedia and narrative prompts, and geolocation tasks in the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 9.

Integration of multimedia and narrative prompts, and geolocation tasks in the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 10.

Augmented heritage markers and layered multimedia content in the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Figure 10.

Augmented heritage markers and layered multimedia content in the Art Nouveau Path MARG.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of three AR-enhanced educational interventions in ESD and heritage-based learning.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of three AR-enhanced educational interventions in ESD and heritage-based learning.

| Dimension |

HeritageSite AR [39] |

EcoMOBILE [48] |

Art Nouveau Path |

| Primary Focus |

Heritage appreciation through exploration and storytelling |

Ecosystem science and water quality analysis |

Sustainability competences through built heritage |

| Target Users |

General public, students |

Middle school students |