Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. [Project’s Name] Activities and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

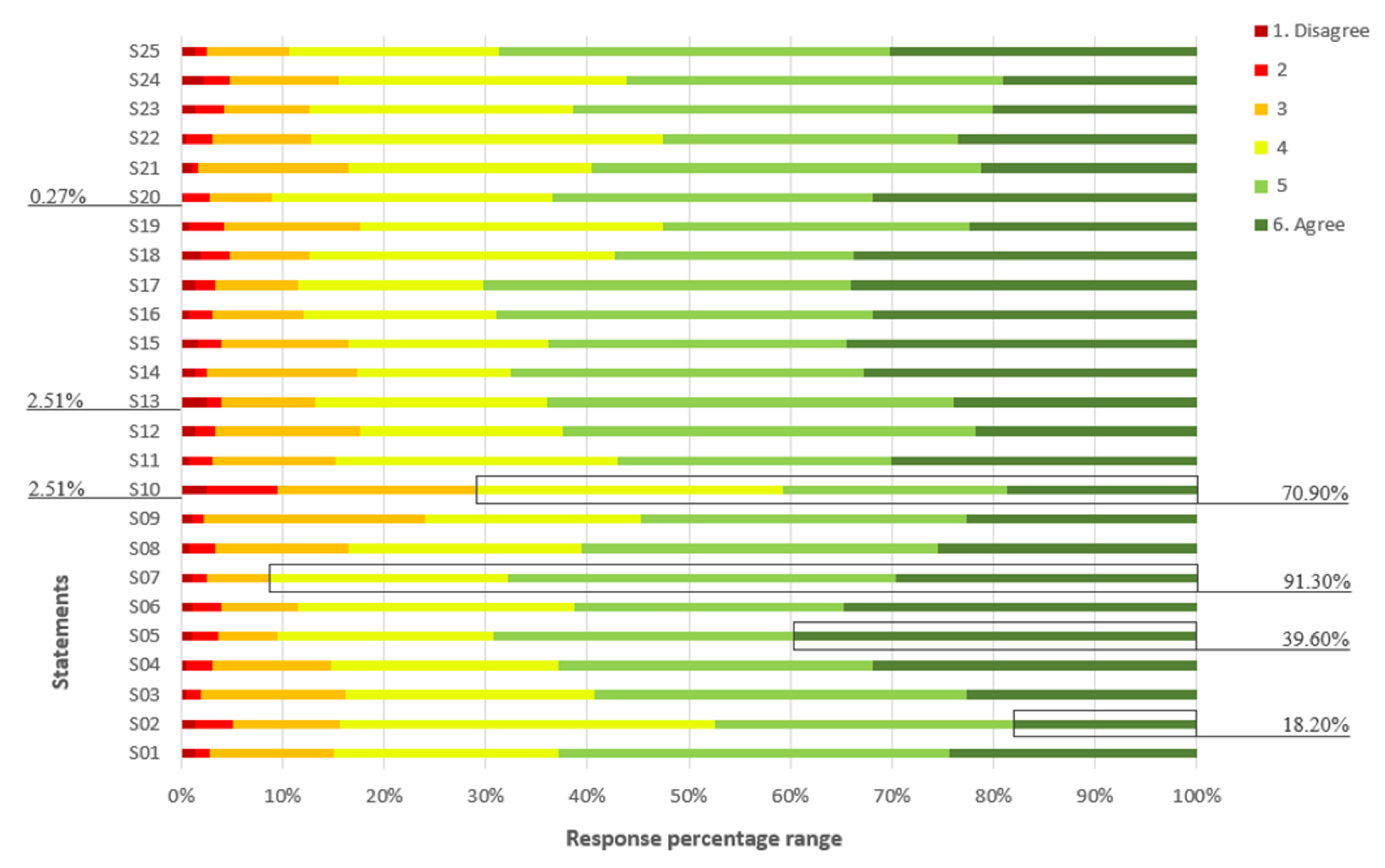

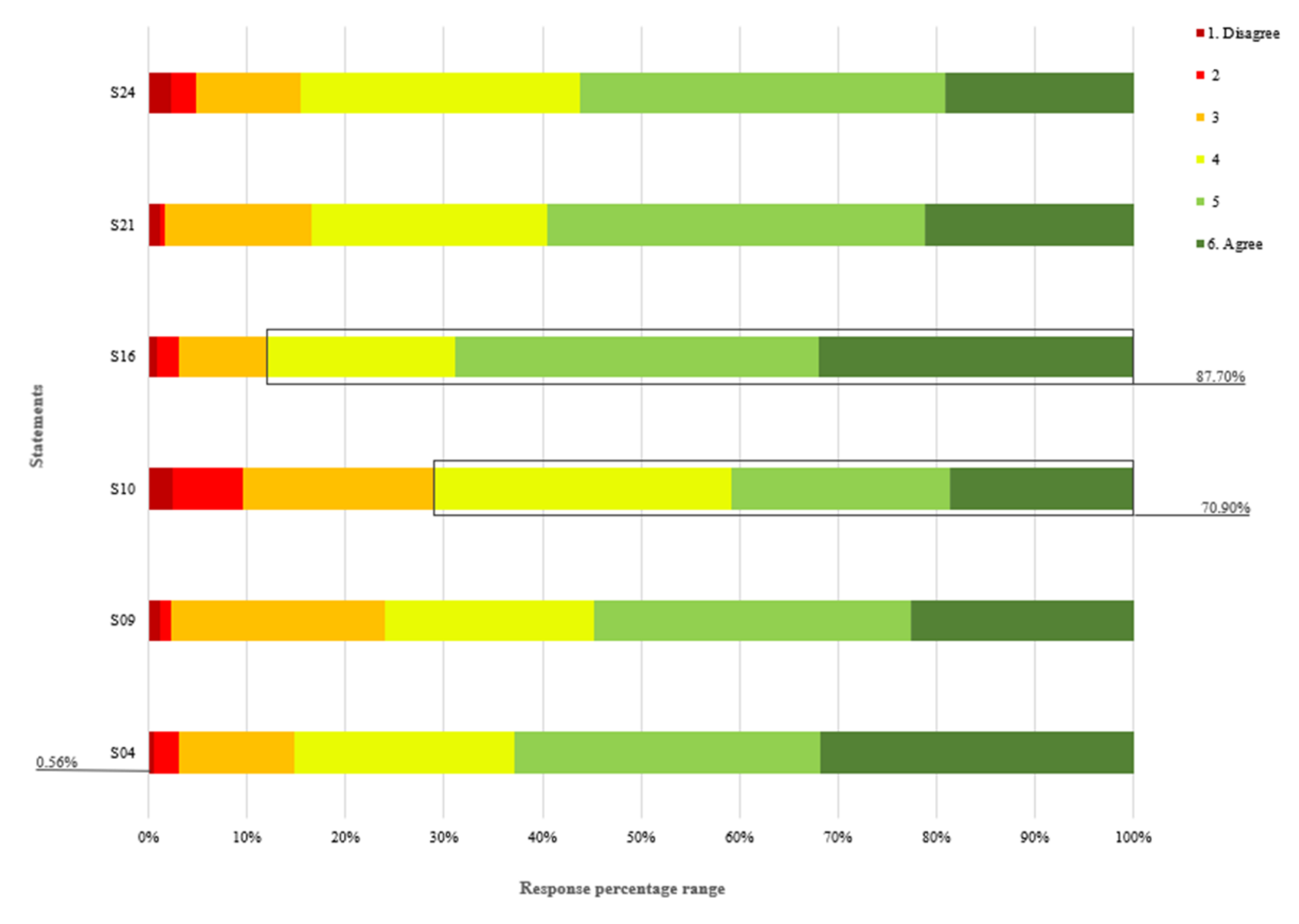

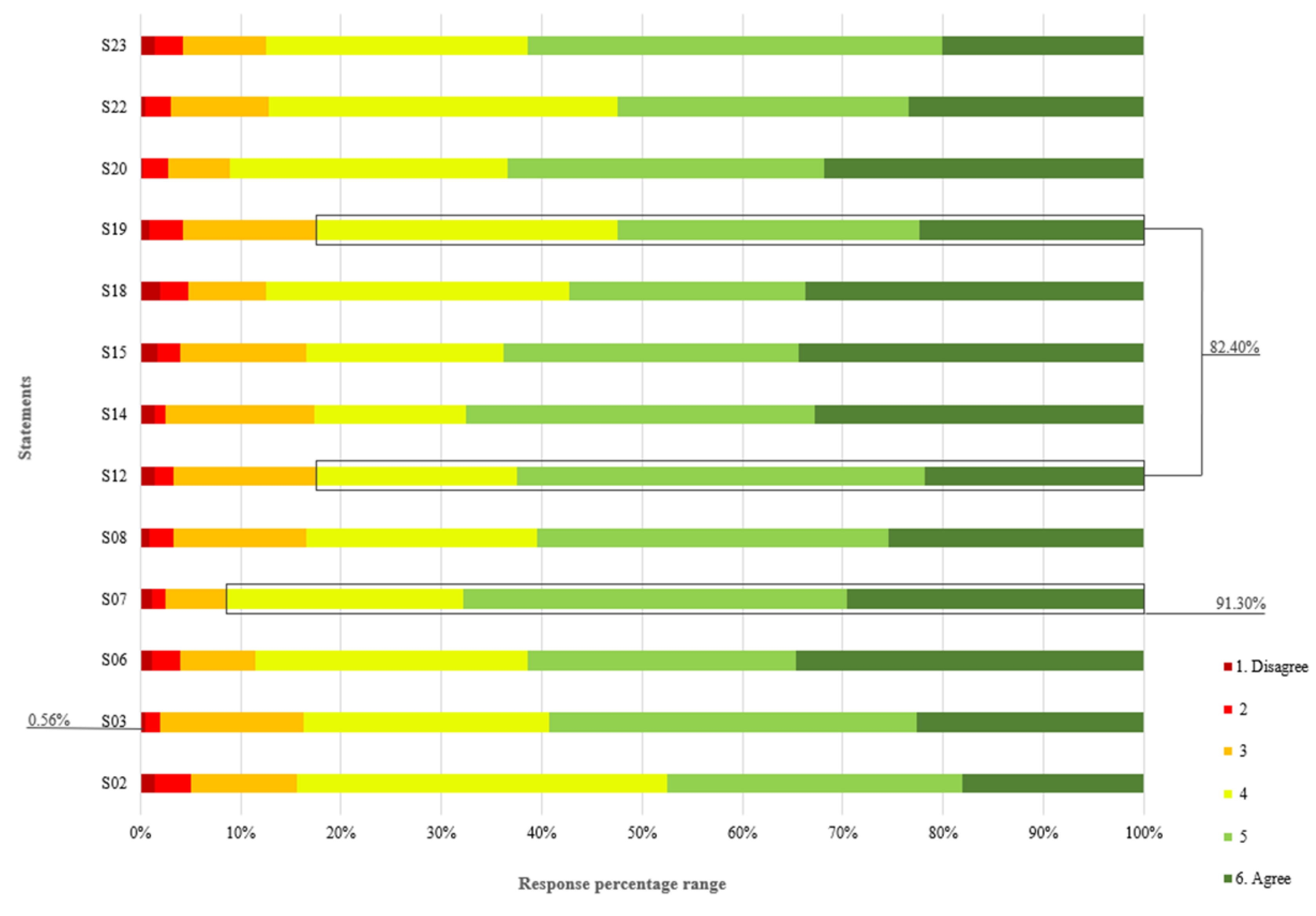

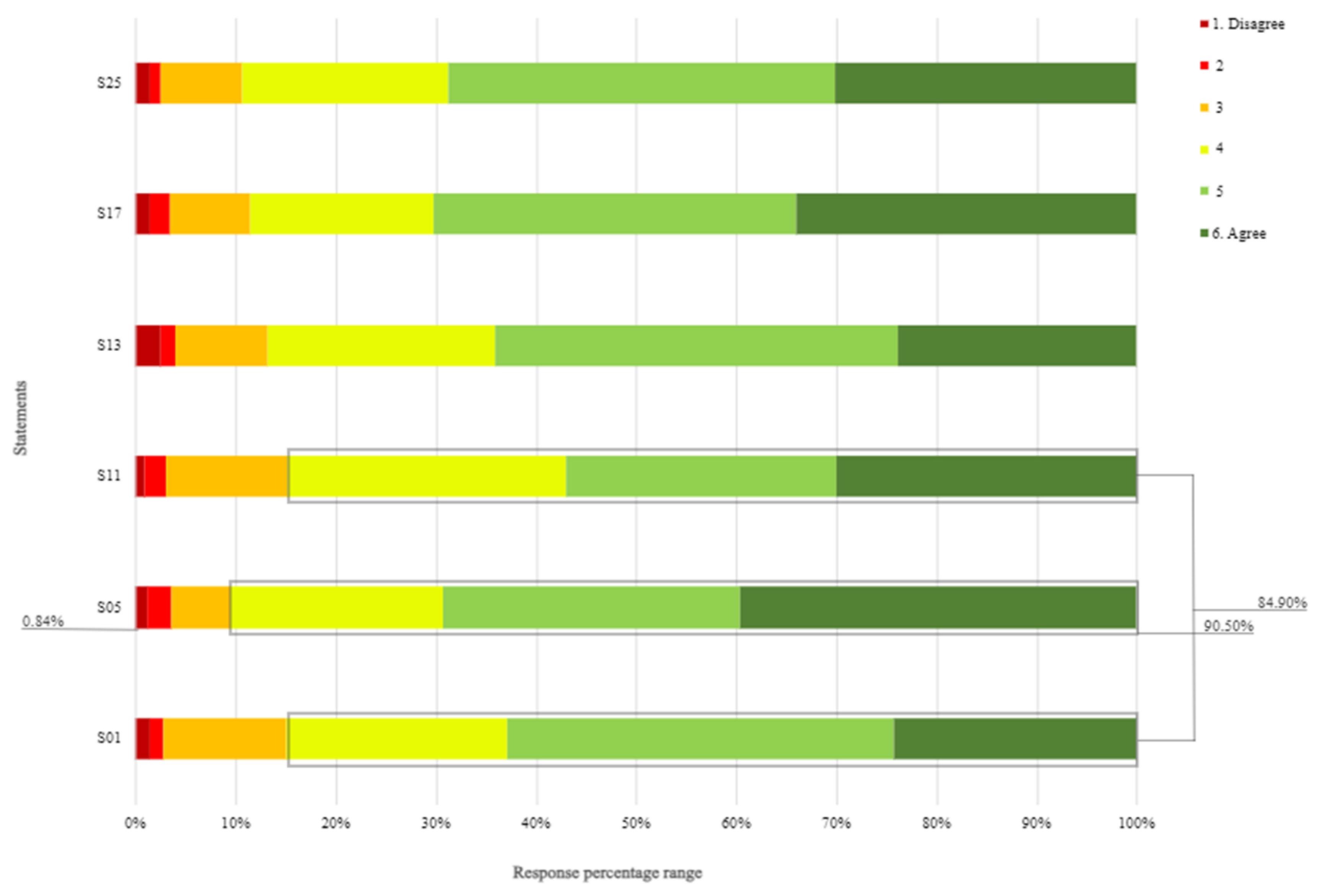

3.1. Participants’ Perception About [Project’s Name] Activities Contribution to Education for Sustainability

3.2. Game Logs: Educational Value

4. Conclusions

4.1. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| MARG | mobile augmented reality games |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| CBE | Cycle of Basic Education |

| KSA | Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes |

| [Removed] | [University’s name] |

References

- D. Perrotti, P. Verma, K. K. Srivastava, and P. Singh, “Challenges and opportunities at the crossroads of Environmental Sustainability and Economy research,” in Environmental Sustainability and Economy, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 345–360.

- T. Konrad, A. Wiek, and M. Barth, “Embracing conflicts for interpersonal competence development in project-based sustainability courses,” Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Rieckmann, Issues and trends in Education for Sustainable Development Issues and trends in Education. United Nations, 2018.

- A. Wiek, L. Withycombe, and C. Redman, “Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development,” Sustain. Sci., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 2011; 203–218. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap. UNESCO, 2020.

- D. Gheorghe, O. M. D. Martins, A. J. Santos, and L. Urdes, “Education for Sustainable Development : What Matters ?,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 9493, pp. 2024; 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Y.-L. Huang, D.-F. Chang, and B. Wu, “Mobile Game-Based Learning with a Mobile App: Motivational Effects and Learning Performance,” J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Informatics, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 2017; 963–970. [CrossRef]

- T. Macagno, A. Nguyen-Quoc, and S. P. Jarvis, “Nurturing Sustainability Changemakers through Transformative Learning Using Design Thinking: Evidence from an Exploratory Qualitative Study,” Sustainability, vol. 2024; 16. [CrossRef]

- K. Mettis and T. Väljataga, “Designing learning experiences for outdoor hybrid learning spaces,” Br. J. Educ. Technol., vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 2021; 498–513. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Cosio, O. Buruk, D. Fernández Galeote, I. D. V. Bosman, and J. Hamari, “Virtual and Augmented Reality for Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review,” Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. - Proc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Laine, “Mobile Educational Augmented Reality Games: A Systematic Literature Review and Two Case Studies,” Computers. 2018; 7, 1–218. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Bressler, J. Oltman, and F. L. Vallera, “Inside, Outside, and Off-Site: Social Constructivism in Mobile Games,” in Handbook of Research on Mobile Technology, Constructivism, and Meaningful Learning, J. Keengwe, Ed. IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2018, pp. 1–22.

- S.-Y. Chen, “To explore the impact of augmented reality digital picture books in environmental education courses on environmental attitudes and environmental behaviors of children from different cultures,” Front. Psychol., vol. 13, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Lampropoulos, E. Keramopoulos, K. Diamantaras, and G. Evangelidis, “Integrating Augmented Reality, Gamification, and Serious Games in Computer Science Education,” Educ. Sci., vol. 13, no. 2023; 6. [CrossRef]

- P. Beça et al. Citizen, Territory and Technologies: Smart Learning Contexts and Practices, S: Web App,” in Citizen, Territory and Technologies, 2018. [CrossRef]

- [Removed].

- J. M. Zydney and Z. Warner, “Mobile apps for science learning: Review of research,” Comput. Educ., vol. 94, pp. 2016; 94, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Sousa Santos, P. Dias, and J. Madeira, “A Virtual and Augmented Reality Course Based on Inexpensive Interaction Devices and Displays,” EuroGraphics 2015- Educ. Pap. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Akçayır and G. Akçayır, “Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature,” Educ. Res. Rev., vol. 20, no. February, pp. 1–11, 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Bianchi, U. Pisiotis, M. Cabrera, Y. Punie, and M. Bacigalupo, The European sustainability competence framework. 2022.

- R. B. Toma, I. Yánez-Pérez, and J. Á. Meneses-Villagrá, “Towards a Socio-Constructivist Didactic Model for,” Interchange. 2024; 55, 75–19. [CrossRef]

- M. Kalz, “Open Education as Social Movement? Between Evidence-Based Research and Activism,” in Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education, O. Zawacki-Richter and I. Jung, Eds. Singapore: Springer, 2023, pp. 43–53.

- OECD, OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: OECD Learning Compass. OECD, 2019.

- [Removed].

- [Removed].

- J. Schoonenboom and R. B. Johnson, “How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design,” Köln Z Soziol, vol. 69, no. Suppl 2, pp. 2017; 107–131. [CrossRef]

- A. Redman and A. Wiek, “Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability,” Front. Educ., vol. 6, no. November, pp. 1–11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- [Removed].

- [Removed].

- [Removed].

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qual. Res. Psychol., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101, 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Creswell and J. D. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2023.

- R. Groves, F. Fowler Jr., M. Couper, J. Lepkowski, E. Singer, and R. Tourangeau, Survey Methodology, 2nd ed. Wiley, 2009.

- [Removed].

- A. Baumber, Transforming sustainability education through transdisciplinary practice,” Environ. Dev. Sustain., vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 7622–7639, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Alkaher, D. Goldman, and G. Sagy, Culturally based education for sustainability-Insights froma pioneering ultraorthodox city in Israel,” Sustain., vol. 10, no. 10, pp. 1–25, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Oliveira and C. G. De Souza, “Gamification in E-Learning and Sustainability : A Theoretical Framework,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 11945, pp. 1–20, 2021.

- J. Sweller, P. Ayres, and S. Kalyuga, Cognitive Load Theory. Springer, 2011.

- T. H. Brown and L. S. Mbati, “Mobile learning: Moving past the myths and embracing the opportunities,” Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 1–21, 2015. [CrossRef]

| Games | Number of Activities | Number of Players | ||||

| 2nd / 3rd CBE | Secondary Education | Higher Education | Teacher Training | Total | ||

| Visit to the salt pans | 1 | 30 | - | - | - | 30 |

| [Project’s name] at the [University] Campus | 2 | - | 27 | 46 | 19 | 92 |

| [City], city of Art Nouveau and Liberty | 1 | 20 | - | - | - | 20 |

| Art Nouveau Path | 9 | 118 | 49 | 25 | - | 192 |

| [City], walking tour | 1 | - | - | - | 40 | 40 |

| Total | 15 | 168 | 76 | 71 | 59 | 374 |

| Theme | Subtheme | Descriptor |

Citation (translated sentence) |

N | Rel. Freq (%) |

| Cultural Awareness |

Local culture | Engagement with local identity, traditions, and heritage | ‘[Learn about the Arte Nova Museum and the José Estêvão Monument]’ | 304 | 59.49 |

| Environmental Protection | Waste management (e.g., microplastics, food waste) | Consequence awareness and actions related to reducing, reusing, and recycling waste | ‘[Food waste at the [University]]’ | 29 | 5.68 |

| Natural resources management (e.g., water, soil, stone and wood as building materials) | Responsible use and understanding of ecological materials | ‘[Examples of Art Nouveau buildings; sand/adobe constructions; materials used]’ | 20 | 3.91 | |

| Biodiversity preservation | Appreciation and care for ecosystems and species diversity | ‘[Preserving the environment and animals; What is salt and salt pans; Microplastics]’ | 17 | 3.33 | |

| Environment/ nature | General concern and connection to the natural world | ‘[soil composition, statue materials, carder materials]’ | 9 | 1.76 | |

| Local natural resources (e.g., salt) | Knowledge of region-specific environmental assets | ‘[Curiosities about salt and microplastics]’ | 4 | 0.78 |

| Theme | Subtheme |

Descriptor (based on GreenComp Framework) |

Citation (translated sentence) |

N | Rel. Freq (%) |

| Values and behaviors |

Responsible use of resources | To acknowledge that humans are part of Nature; and to respect the needs and rights of other species and of Nature itself to restore and regenerate healthy and resilient ecosystems | ‘[Don't spend all resources in the present’] | 93 | 23.79 |

| Sustainable lifestyle | To support equity and justice for current and future generations and learn from previous generations for sustainability | ‘[Sustainability is essential if we are to continue living on our planet.’] | 24 | 6.14 | |

| Sustainable values | To reflect on personal values; identify and explain how values vary among people and over time, while critically evaluating how they align with sustainability values | ‘[the formation of aware and committed citizens for a balanced future’] | 9 | 2.30 | |

| Present actions | Environmental preservation | To identify own potential for sustainability and to actively contribute to improving prospects for the community and the planet | ‘[It's about being responsible towards nature and the animals around us. In this way we can have a more cared and healthier planet to live on.’] | 91 | 23.27 |

| Future thinking | Intergenerational equity | To envision alternative sustainable futures by imagining and developing alternative scenarios and identifying the steps needed to achieve a preferred sustainable future | To manage transitions and challenges in complex sustainability situations and make decisions related to the future in the face of uncertainty, ambiguity and risk | ‘[thinking about the future of the planet’] | 85 | 21.74 |

| (Unspecified information or not related to sustainability) | 89 | 22.76 | |||

| [project’s name] Games | ||||||

| Visit to the salt pan | [project’s name] on [University] Campus | [city], city of Art Nouveau and Liberty | Path of Art Nouveau: from Heritage to Sustainability | [city], walking tour | ||

| Number of groups who played the game | 7 | 39 | 5 | 59 | 14 | |

| Final score | Average | 64.29% | 76.70% | 86.40% | 83.30% | 66.30% |

|

Standard deviation |

5.34 | 10.33 | 5.35 | 29.77 | 19.83 | |

| Minimum-maximum | 50.00%- 71.40% |

35.00%- 100.00% |

75.30%- 90.90% |

33.33%- 100.00% |

29.20%- 95.00% |

|

| AR score | Average | 56.25% | 86.84% | 81.81% | 75.00% | 81.80% |

|

Standard deviation |

3.20 | 21.95 | 19.00 | 40.16 | 3.16 | |

| Minimum-maximum | 0.00%- 100.00 |

4.17%- 100.00% |

83.33%- 100.00% |

27.27%- 100.00% |

57.14%- 100.00% |

|

| Correct answers | Average | 64.30% | 80.58% | 85.40% | 86.11% | 72.40% |

|

Standard deviation |

1.07 | 18.89 | 1.07 | 4.96 | 3.26 | |

| Minimum-maximum | 50,00%- 71.40% |

45.83%- 100.00% |

77.30%- 90.90% |

44.44%- 100.00% |

41.20%- 95.90% |

|

| Incorrect answers | Average | 35.70% | 19.42% | 13.60% | 13.89% | 30.30% |

|

Standard deviation |

1.07 | 5.11 | 1.07 | 4.96 | 3.55 | |

| Minimum-maximum | 28.60%- 50.00% |

0.00%- 54.17% |

9.10%- 22.70% |

0.00%- 55.56% |

4.20%- 62.50% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).