1. Introduction

Plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere are key determinants of plant health, productivity, and soil fertility [

1,

2]. Among these microbes, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), which belong to the subphylum

Glomeromycotina, spontaneously form a functional endomycorrhizal symbiosis with grapevine roots. These fungi are present in most of the commercial vineyards, influencing the surrounding microbiome structure that forms the so-called mycorrhizosphere. This symbiosis significantly enhances grapevine establishment, growth, photosynthesis, and gas exchange, as well as nutrient uptake, drought tolerance, and grape quality [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These benefits are achieved through various mechanisms, which include: (a) improved root water uptake due to the increased soil exploration via extra-radicular hyphae, which effectively extend plant roots, thereby improving water uptake efficiency; (b) better mineral nutrition, especially with regards to phosphorus and other macro- and micronutrients, not only due to the extended root system facilitated by AMF but also thanks to the direct role of extra-radicular hyphae in nutrient uptake; (c) alterations in root architecture, anatomy, and morphology; (d) modification of some physiological processes and the production of secondary metabolites (e.g., phenolic compounds, stilbenes) as well as enzymatic activities, especially those involved in plant antioxidative responses [

5,

7]; and (e) induction of the plant hormones (e.g., ABA), which play an essential role in mediating some plant responses to different stresses, including drought [

8,

9]. Additionally, AMF hyphae contribute to soil structure by binding soil particles and producing glomalin, a gluelike insoluble substance [

10]. Moreover, AMF symbiosis can trigger a mycorrhiza-induced resistance in grapevines, enhancing tolerance to both biotic and abiotic stresses [

6,

7]. A recent study in grapevines also indicates that mycorrhization induced changes in the stomatal anatomy under water deficit, suggesting a potential regulatory role of AMF in the expression of genes related to leaf anatomy [

11].

It is also well-known that, under natural conditions, the entire mycorrhizal complex comprises not only the plant and the symbiotic fungus but also other associated microorganisms, being bacteria, and especially rhizobacteria, the most abundant [

12]. Rhizobacteria include plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and mycorrhizal helper bacteria (MHB). PGPR are a beneficial and heterogeneous group of microorganisms that can be found in the rhizosphere, on root surfaces, or in association with plant roots. Genera such as

Pseudomonas,

Azospirillum,

Rhizobium, and

Bacillus have been widely studied for their ability to enhance plant growth and health through multiple mechanisms: 1) they contribute to plant nutrition by facilitating the uptake of essential nutrients via biological nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and mineral mobilization; 2) they bolster plant defense by activating induced systemic resistance against pests and pathogens and by producing antibiotics, hydrolytic enzymes, and other antimicrobial compounds; 3) they influence hormonal balance and stress responses through the production of phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid, gibberellins, polyamines, nitric oxide, and stress-alleviating enzymes, supporting plant adaptation under adverse conditions [

1,

13,

14]. Synergistic interactions among PGPR strains have been shown to amplify these effects, enhancing both plant development and protection [

14]. Conversely, MHB play a crucial role in modulating plant–fungal interactions. They are known for their ability to enhance the mycorrhizal development by promoting hyphal growth, spore germination, and root colonization [

15]. Recent findings suggest that a specific MHB can alleviate drought stress in

Helianthemum almeriense plants colonized by mycorrhizal fungi by modulating water relations and plant hormone levels. [

12].

Although grapevine is a highly mycotrophic plant, intensive agricultural practices over recent decades, such as heavy fertilization, tillage, and the use of pesticides (including fungicides and herbicides), have reduced the beneficial effects on the soil, as well as the abundance, diversity, and efficacy of AMF and bacteria [

3,

6]. Therefore, the introduction of selected AMF or beneficial bacteria into agroecosystems may benefit crop growth by optimizing plant nutrition and enhancing plant survival [

16], especially when combined with more sustainable soil management practices. Microbial inoculants may also enhance agronomic efficiency by lowering production costs and minimizing environmental pollution, as they can enable the reduction or even elimination of chemical fertilizers [

1].

Although numerous studies have demonstrated the benefits of microbial inoculants such as AMF and PGPB (plant growth-promoting bacteria) in grapevine cultivation, their adoption in both conventional and organic viticulture is still restricted. This reflects an ongoing debate about their necessity and overall effectiveness in vineyard applications. A significant concern is the relatively high cost of commercial inoculants, which is further compounded by their fluctuating performance under real-world field conditions. Whereas controlled laboratory and greenhouse experiments have consistently shown positive effects of AMF and PGPB inoculation on grapevine growth and physiology [

6,

17], field trials often yield variable or unsatisfactory results. The success of bacterial inoculants depends on several factors, including the composition of root exudates, the efficiency of bacterial colonization, and the overall soil health [

1]. The performance of AMF communities is influenced by a wide range of environmental and biological factors, such as soil properties (e.g., pH, phosphorus and nitrogen content, moisture, temperature, and organic matter), agricultural practices (e.g., tillage

vs. no-tillage), irrigation regimes (e.g., deficit

vs. full irrigation), fungal metabolic activity, and the identity of the host plant. Specifically, the genotype of the rootstock and its compatibility with the fungal species play a critical role in determining the success of the symbiosis [

3,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Recent research also emphasizes the importance of host identity in shaping the composition and structure of AMF and bacterial communities in the rhizosphere and root endosphere. Differences in root exudate composition among grapevine rootstocks appear to be a key factor influencing microbial community dynamics [

22,

23].

There is increasing evidence that early field inoculation can enhance the establishment of beneficial interactions between grapevine roots and soil microbes. This is because microbes can more easily colonize plant niches due to a lower competition [

7,

9]. For instance, Camprubí et al. [

16] showed that early inoculation with a selected AMF strain improved the establishment and growth of the 110R, increasing vine survival by boosting plant fitness. Similarly, Torres et al. [

24] found that AMF inoculation in two-year-old, field-grown Merlot grapevines improved vegetative growth, water status, and photosynthetic activity, particularly under deficit irrigation. Rolli et al. [

13] also reported that PGPB significantly improved growth and yield in young grapevines compared to non-inoculated controls.

However, not all of the inoculation efforts are successful. Nerva et al. [

7] reported that a commercial AMF inoculant failed to establish in young Pinot noir/3309C vines, regardless of the timing of application. This failure was attributed to the ineffectiveness of the inoculant, over-fertilized soils—with exceptionally high phosphorus levels—and poor compatibility with the rootstock. Similarly, Camprubí et al. [

16] found that, whereas several native endophytes and

Glomus intraradices BEG 72 improved the growth of 110R under greenhouse conditions using sterile, low-phosphorus soil, only a specific inoculant produced significant improvements in survival and early growth under field conditions. Likewise, the presence of AMF alone does not guarantee a beneficial symbiosis, and it is essential to evaluate the actual functionality of the mycorrhizal association to determine whether it has a meaningful contribution to vine performance under field conditions [

6]. Moreover, in some cases, inoculation may even be unnecessary, particularly in soils that already host abundant native AMF populations capable of effectively colonizing grapevine roots [

20].

Therefore, grapevines tend to select a specific subset of available fungal and bacterial communities, which may lead to functional differences in the microbiome that can have an influence on ecosystem roles and affect the growth and adaptation to environmental conditions of the host plant. For instance, the addition of the mycorrhizal inoculum in vines promoted the genera

Pseudomonas in 1103P and

Bacillus in SO4. Both genera have the ability to protect vine plants against several fungal pathogens (

Botrytis,

Neofusiccocum,

Ilyonectria,

Aspergillus,

Phaeomoniella, Cylindrocarpon, and

Phaeoacremonium) as well as soil nematodes such as

Meloydogine and

Xiphinema [

25,

27]. Recent studies have demonstrated that the rootstock genotype is a key driver in shaping the composition of the soil and root-associated microbiome, including AMF, and that the efficiency of mycorrhizal colonization and its effects on plant growth can vary significantly depending on the specific rootstock–AMF combination. For example, Giovannini et al. [

28] showed that, although all tested AMF inocula were able to colonize different grapevine rootstocks, the extent of colonization and the resulting plant responses were highly dependent on the rootstock genotype, highlighting the importance of considering this interaction in sustainable viticulture strategies.

Besides, recent findings suggest that the interaction between rootstock and AMF + PGPB inoculum is a key factor in grapevine adaptation to water deficit, both under current and projected climate change scenarios [

11]. These findings highlight the importance of using carefully selected microbial inoculants, as not all of the AMF or bacterial strains, even within the same species, yield successful results in the field. To exploit the potential benefits of AMF and bacteria in vineyards, it is essential to conduct a careful, site-specific evaluation before inoculation. This includes an assessment of the soil fertility and management practices, the irrigation regimes, the composition of native soil microbiota, and the compatibility of grapevine genotype [

22,

24].

The main goal of this study was to evaluate the effect of a co-inoculation of commercial microbial inoculants containing AMF and PGPR, as well as the application of MHB in field-grown Monastrell plantlets grafted onto 140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C rootstocks. These commercial rootstocks were chosen because they are the most widely used in the study area and provide a good productive response, increasing the efficiency of water use and the quality of Monastrell grapes in warm, semiarid conditions. From the early establishment of the vineyard, we studied the physiological and agronomic response of inoculated young vines under irrigated conditions. Besides, we evaluated the effect of the rootstock on young Monastrell vines and its interaction with microbial inoculation in a semiarid environment. Considering the positive effects of inoculation with beneficial microorganisms (mainly AMF) on grapevines reported in the literature (especially under controlled conditions, such as those found in pots and greenhouses), we aimed to verify the following hypothesis under field semiarid conditions: a) early microbial inoculation with AMF/PGPR in a newly planted vineyard can improve water and nutrient uptake, growth, and yield, thereby increasing early plant fitness; and b) the rootstock can influence the grapevine's response to microbial inoculation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Conditions, Plant Materials, Irrigation, and Soil Treatments

The trial was conducted from 2017 to 2023 in a 0.2-ha plot of young (0-6 years-old) Monastrell (

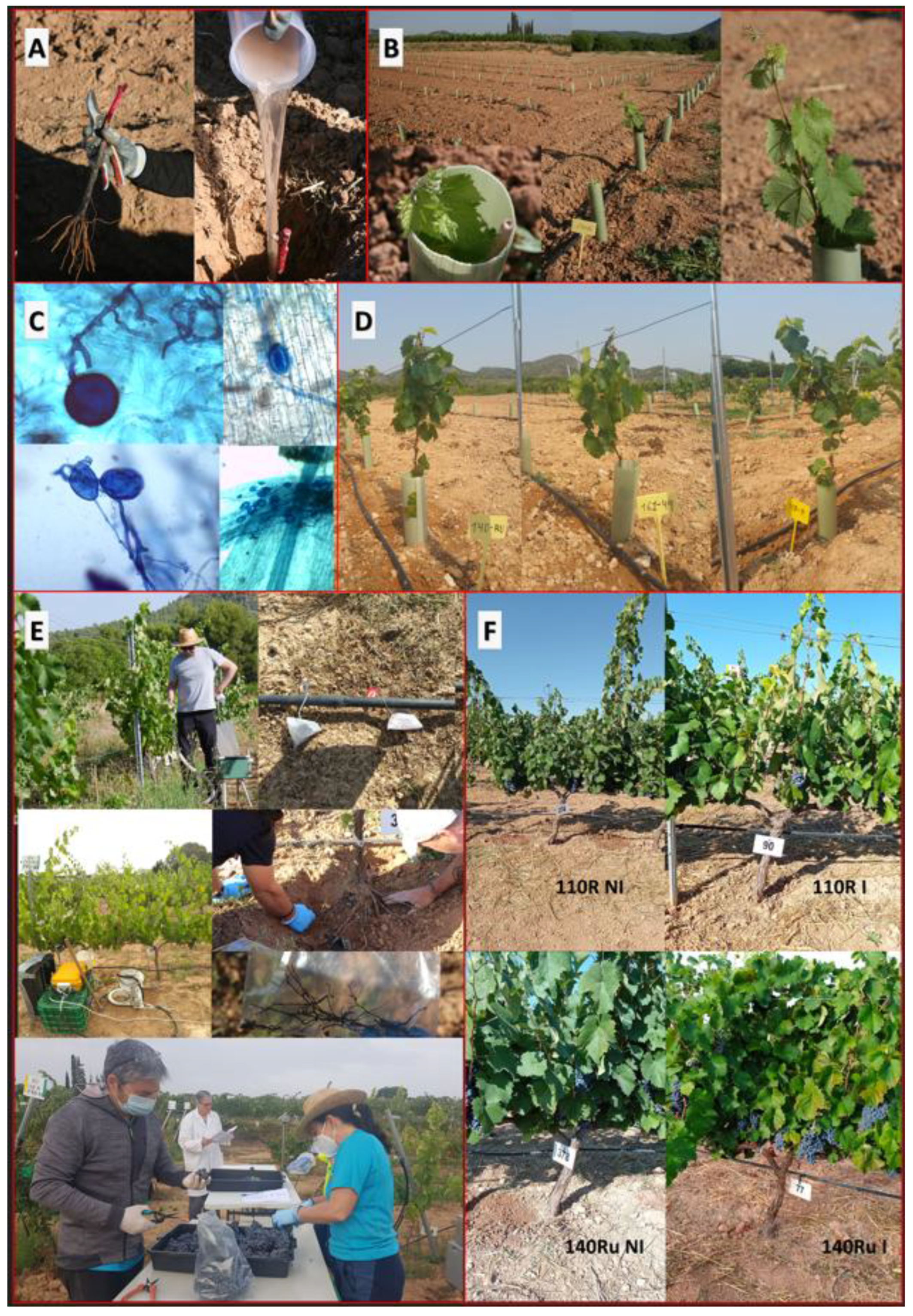

V. vinifera L. syn. Mourvedre) trellis vines grafted on three rootstocks, 140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C, in an experimental orchard located in Cehegín (SE Spain, 38° 6´ 38.13´´ N, 1° 40´ 50.41´´ W, 432 m a. s. l.). Planting took place in March 2017 (

Figure 1A). Planting density was 2.8 m between rows and 1.0 m between plants (3571 vines/ha). The soil in the plot had a clay-loam texture (45% clay, 34% silt, 21% sand) and an organic-matter content of 1.1%, an apparent density of 1.40, a pH of 7.83, an electrical conductivity of 0.117 mS cm

–1, an active limestone (CaCO

3) percentage of 15.3%, a C/N ratio of 8.9, a total N percentage of 0.072%, an assimilable P of 22.76 mg kg

–1, a K exchange of 0.99 meq/100 g, a Ca exchange of 13.48 meq/100 g, a Mg exchange of 2.85 meq/100 g, and a cation exchange capacity of 17.48 meq/100 g. The soil was highly compacted to a depth of 70 cm due to the previous land use. The climate was Mediterranean semiarid, characterized by hot, dry summers and a low annual rainfall (

Table 1). Irrigation water was sourced from a well, with a pH of 7.96 and an electrical conductivity ranging from 0.68 to 0.81 dS m

−1. The training system was a bilateral cordon trellised to a three-wire vertical system. Vine rows were oriented NW–SE. After pruning, six two-bud spurs (12 nodes) were left per vine. In May, non-productive green shoots were uniformly removed across all of the treatments, following standard local viticultural practices.

Crop evapotranspiration (ETc = ETo × Kc) was estimated using varying crop coefficients (Kc) based on the FAO recommendations and adjusted for the Mediterranean region, as well as reference evapotranspiration (ETo) values (

Table 1). The applied Kc values were as follows: 0.35 in April, 0.45 in May, 0.52 in June, 0.75 from July to mid-August, 0.60 from mid-August to early September, and 0.45 from mid-September to October. ETo was calculated weekly from the mean values of the previous 5 years, applying the Penman-Monteith-FAO method. Daily climatic data were collected from a meteorological station (Campbell mod. CR 10X) located at the experimental vineyard and operated by the Agricultural Information Service of Murcia (SIAM, IMIDA, Murcia, Spain) (

Table 1). All of the vines, regardless of the rootstocks, were irrigated with similar annual water volumes from April to October, using high-frequency drip irrigation (2-5 times per week during the late evening, depending on the phenological period). Water was applied by one pressure-compensated emitter per plant (4 L h

–1) with one drip-irrigation line per row. During the first four years (2017–2020), vines were irrigated with high water volumes to ensure a proper vineyard establishment (

Table 1). In addition, all of the vines received the same annual dose of organic fertilizer—an amino acid-enriched liquid organic matter (compost, 50 L ha

−1 month

−1, certified for organic farming)—supplied through the drip irrigation system from April to August. From the fourth year onwards (2021–2023), vines were irrigated solely with water under a controlled deficit irrigation (DI) regime, applying between 90 and 100 mm year

−1 (

Table 1). Moreover, no liquid fertilizer was applied through irrigation. Instead, fertilization during this period consisted of a single annual application of solid organic/biodynamic cattle manure in autumn, distributed on both sides of the vine rows and incorporated into the soil via shallow trenching, at a rate of 4 to 7 tons ha

−1.

During the early years of vineyard establishment, management practices commonly used by local winegrowers were adopted. Inter-row and under-vine weeds were removed using mechanical methods throughout the growing season. Soil management involved no tillage, and all the vineyard management was conducted in accordance with organic production standards, without the use of unauthorized synthetic herbicides or pesticides. Since 2018, a cover crop of legumes and grasses (vetch, mustard, alfalfa, pea, wheat) has been sown annually in the inter-row spaces each autumn. These cover crops were allowed to grow until spring (April), when they were mowed and incorporated into the soil as green manure using minimal tillage (2-3 cm deep), to preserve the soil structure.

When designing this experiment, several key factors that could promote mycorrhization were initially taken into account to set it up: the low P content in the experimental soil, the selection of microorganisms adapted to a semiarid environment, the use of organic production (with no pesticides, herbicides, inorganic fertilization, or tillage), and the application of a deficit irrigation strategy after the establishment.

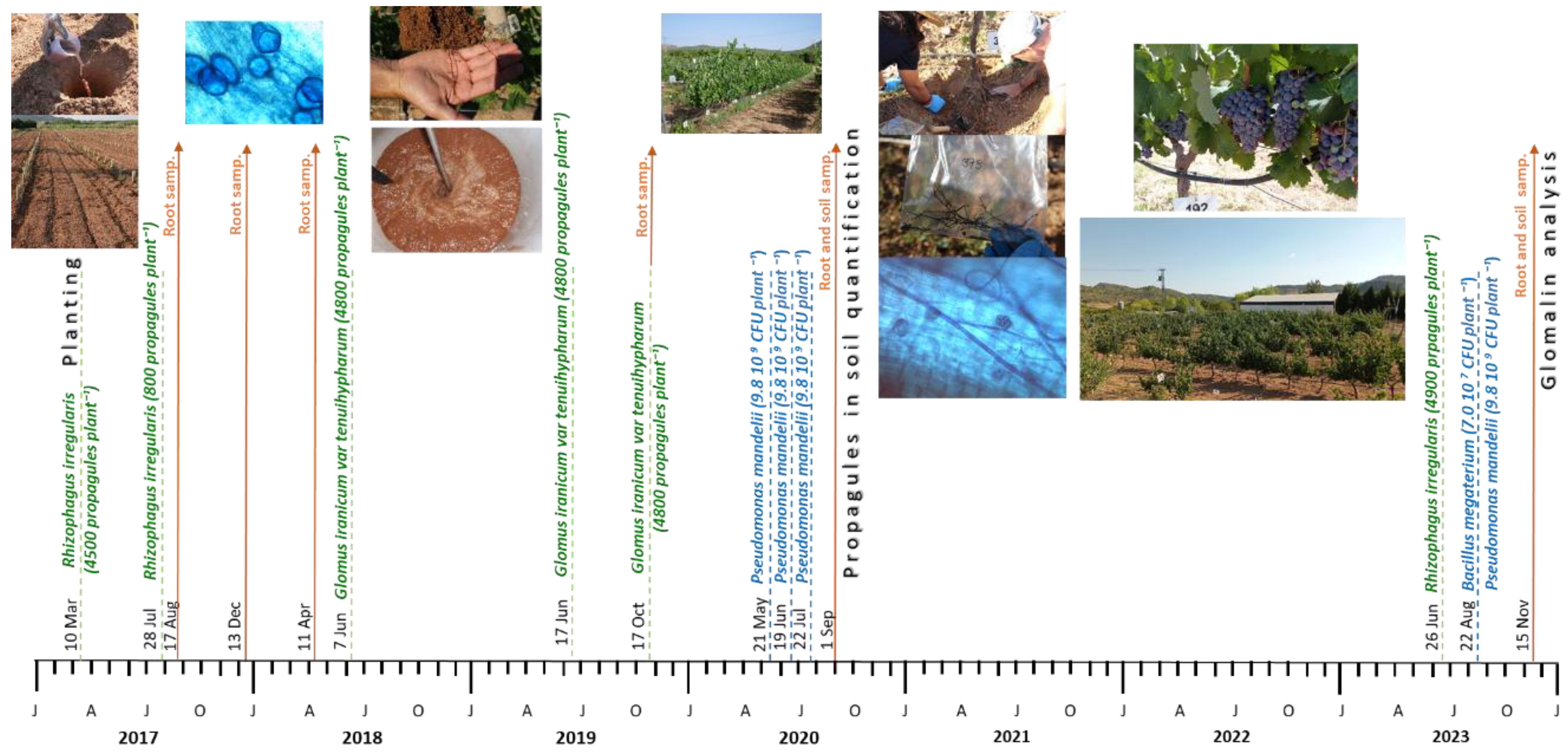

2.2. Experimental Design and Microbial Inoculation Treatments

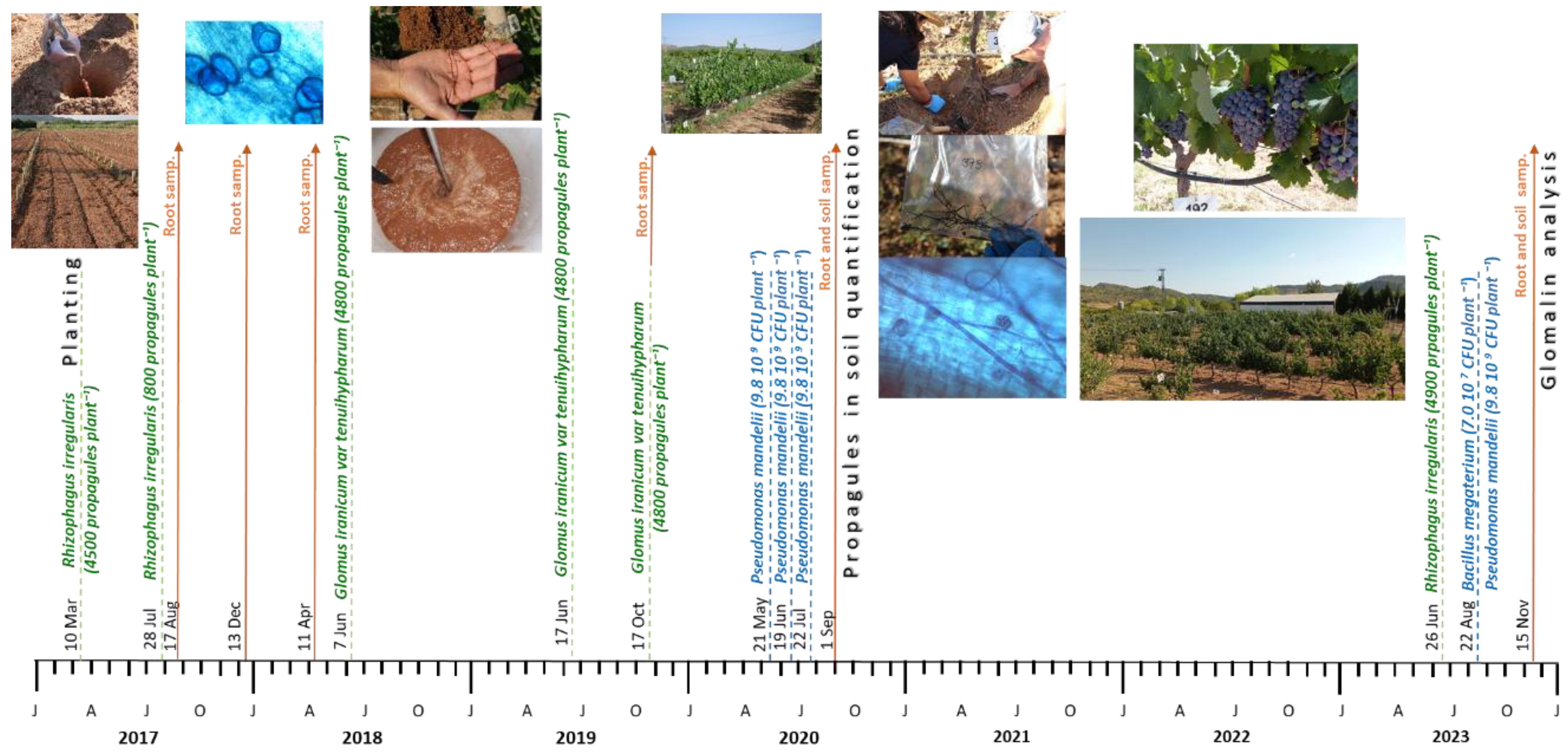

From the time of the planting, the vineyard was divided into four subplots, and the experiment followed a randomized block layout with four blocks in total (two blocks per subplot). Two of the subplots were inoculated with a commercial microbial inoculum (I), applied directly into the planting hole at the time of establishment in the field (

Figure 1), whereas the other two subplots served as non-inoculated controls (NI). Each subplot contained 24 vines of each rootstock (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C), totaling 48 vines per rootstock-inoculation combination. Additionally, during the course of the experiment, sequential microbial inoculations were performed using different AMF species (

Rhizophagus irregularis and

Glomus iranicum) as well as successive applications of an MHB (

Pseudomonas mandelii strain 29) and a PGPB (

Bacillus megaterium) in combination with

R. irregularis, in the inoculated subplots through the irrigation system, as shown in

Figure 2.

In both subplots (I and NI), five root samplings were conducted (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2023). For each of the samplings, four representative root samples were collected from different vines of each rootstock–inoculation combination, at a depth of 30–40 cm in the rhizosphere near the plant. These root samples were processed following standard procedures for this type of samples: root isolation, selection of fine roots, staining, and observation of mycorrhiza structures using optical microscopy. Root samples were cleaned and stained with trypan blue [

32], but replacing lactophenol with lactic acid. One hundred root segments per plant were mounted on slides, squashed by pressing on the coverslips, and quantified for AM colonization [

33]. The percentage of mycorrhization was calculated based on the number of microscopic fields in which mycorrhizal structures were observed. Two types of organelles were distinguished: those indicative of active mycorrhization (hyphae, vesicles, and arbuscules) and those not directly associated with active mycorrhization (spores). This allowed for a distinction to be made between active mycorrhization (defined by the presence of hyphae, vesicles, and arbuscules inside the root), and non-active mycorrhization (characterized exclusively by the presence of spores in the soil, outside the root) but associated with the mycorrhizal environment [

34,

35].

2.3. Extraction and Quantification of Arbuscular Fungal Propagules in Soil

In November 2020, in addition to root sampling, soil sampling was conducted to assess the effect of inoculation treatments carried out during that campaign on mycorrhization. For this purpose, a procedure for extracting and quantifying AMF propagules (spores and sporocarps) was used [

36]. Using this procedure and through the use of 250/125 and 50 µm mesh sieves, sporocarps and larger spores were separated with the former, whereas smaller spores were collected using the latter.

2.4. Glomalin Concentration in Soil

In November 2023, soil sampling was conducted to determine the presence of glomalin at the end of the trial. In the same vines that were used to sample the roots and evaluate the mycorrhization status, soil samples were obtained from the root environment to assess the concentration of total glomalin (TG). Replicate 0.25 g soil samples of dry-sieved 1–2 mm aggregates were extracted with 2 ml of extractant. TG was extracted using 50 mM citrate, pH 8.0 at 121° C for 90 min. For sequential extractions, the supernatant was removed by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 15 min; 2 mL of 50 mM citrate, pH 8.0 were added to the residue and autoclaved for 60 min. The process continued until the supernatant showed none of the red-brown color typical of glomalin. Extracts from each replicate were pooled and then analyzed. After completing the extraction cycles, protein in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford dye-binding assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard [

37].

2.5. Organic Matter Decomposition

We assessed the rate of organic matter decomposition using standard plant material, following the Tea Bag Index (TBI) method [

38]. Pairs of green and rooibos tea bags were used. Each tea bag was labelled with a waterproof marker and weighed (±0.01 g). Subsequently, one replicate of each tea type was buried in each of the plots at a depth of 8 cm, all of them being individually marked (for a total of 32 sample units, with 8 samples per rootstock-inoculation combination). Burial was carried out between May and June 2019, and tea bags were retrieved 90 days later. After recovery, tea bags were cleaned of roots and debris, dried, and reweighed. Based on the weight loss, we calculated the TBI parameters: k (decomposition rate constant) and S (stabilization factor). Green tea contains a highly labile fraction that decomposes rapidly at first. After 90 days, the extent of decomposition of this labile fraction (k) and the amount that has stabilized (S) can be determined. In contrast, rooibos tea decomposes much more slowly and remains in the initial phase of decomposition after 90 days; its weight loss serves as a proxy for the initial decomposition rate (k). TBI parameters were calculated using the spreadsheet template provided by the TBI research team, available at

http://www.teatime4science.org.

2.6. Soil Gas Exchange and Oxygen Diffusion Measurements

Between July 20 (pre-veraison) and September 8, 2021 (post-veraison), soil CO2 and H2O exchange were monitored in situ with a LI-8100A infrared gas analyzer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) equipped with a 20 cm survey chamber. To capture continuous diel patterns, we coupled the analyzer to an automated long-term chamber (model 8100-101). The chamber was mounted on each permanent stainless-steel collar for ≥ 48 h at some point between the onset of veraison and two weeks after its completion (mid-ripening). Measurements were taken in the wetted root zone (east-facing wet bulb) on four vines per rootstock × inoculation treatment, with sampling days selected randomly but under comparable weather conditions. Fluxes were logged at 60-min intervals, providing high-resolution time series for subsequent analysis.

In 2021, soil oxygen diffusion rate (ODR) was measured with a portable oxygen diffusion meter, model 14.36 (Royal Eijkelkamp, Giesbeek, NL). This instrument maintains a constant potential of 0.65 V between a cylindrical platinum–iridium micro-electrode (1.2 mm Ø, 6 mm exposed length) and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, driving the reduction of all of the O2 that reaches the Pt surface (constant-current technique). The steady reduction current is internally converted to flux and logged as µg O2 cm−2 min−1. Measurements were taken at a depth of 5–10 cm, in the wet root zone, with four replicates per rootstock × inoculation treatment, on randomly selected pre- and post-veraison days under comparable weather conditions.

2.7. Vine Water Status and Leaf Gas Exchange

Each year, the stem water potential (Ψs) was determined monthly from fruit set until harvest. Eight healthy, fully exposed, and expanded mature leaves were selected from the main shoots in the middle–upper part of the vine canopy for each rootstock × inoculation treatment. All of the leaves were east-facing, enclosed in aluminum foil, and covered with plastic for at least 2 h before midday measurement. Ψs was measured at noon (12:00 p.m.–1:30 p.m.) using a pressure chamber (Model 600; PMS Instrument Co., Albany, OR, USA).

Net leaf photosynthesis was measured every 14 days between 9:00 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. from May to September in 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2023 on selected clear and sunny days. Measurements were taken on east-facing, healthy, fully expanded, mature leaves exposed to sunlight (one leaf on each of 8 representative vines per rootstock, the same vines used to measure Ψs), located in the outer canopy and growing on the main shoots. Leaf gaseous exchange parameters were measured with a portable photosynthesis measurement system (LI-6400, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA) equipped with a broadleaf chamber (6.0 cm2). During the measurements, leaf temperature ranged from 23 to 39 °C, leaf-to-air VPD ranged from 1.4 to 5.3 kPa, and relative humidity ranged from 30 to 50%. The molar air flow rate inside the leaf chamber was 500 µmol mol−1. All of the measurements were taken at a reference CO2 concentration close to ambient concentration (400 µmol mol–1) and at a saturating PPFD of 1500 µmol m–2 s–1.

2.8. Leaf Mineral Analysis

Leaf samples were collected in July 2018, 2021, and 2023 for mineral analysis. About 40 leaves were collected from eight vines per rootstock × inoculation treatment. Leaves were washed immediately, dried at 65° C for one week, and milled. After plant tissue was digested, ashes were dissolved in HNO3, and K, Mg, Ca, Na, P, Fe, Mn, Zn, and B were analyzed with an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (Varian MPX Vista, Palo Alto, CA). Nitrogen concentration was determined using the LECO FP-428 protein detector.

2.9. Vegetative and Reproductive Development

From 2018 to 2023, the total leaf area (TLA) per vine at the end of July (veraison period) was estimated in 16 to 32 vines (depending on the year) per rootstock × inoculation treatment, using a non-destructive method. This method employed a first-order polynomial equation that related the shoot length (SL) to the TLA of the main shoot, previously developed for each of the rootstocks [

39]. TLA per plant was calculated by selecting five representative main shoots per vine, measuring their average SL with a tape, and multiplying the average shoot leaf area by the total number of main shoots of the vine. During the winters of 2018 to 2023, pruning weight (PW) measurements were taken in 24 vines per rootstock × inoculation treatment, including the same vines used for yield, leaf area, and shoot measurements.

Each year, at harvest (mid-late September), yield response was measured across 24 vines per rootstock × inoculation treatment. Harvest date was determined according to the grower's practices in the area, occurring when °Brix reached 23.5–24.0. Yield per vine (kg vine−1), number of clusters per vine, berry weight, and cluster weight were calculated. Productive water use efficiency (WUEyield) was expressed as the mass of fresh grapes produced per m3 of applied water per vine.

2.10. Berry and Must Quality

Samples of mature berries were collected from each rootstock × inoculation treatment at harvest in 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023, and transported to the laboratory. Each sample consisted of 800–900 g of berries, randomly gathered from different clusters on each vine. The berries were crushed with an automated blender (Coupe 550 GT), avoiding seed breakage. The crushed grape sample was then centrifuged, and the resulting juice was used for the analysis of pH, total soluble solids (TSS), solutes per berry, titratable acidity, and tartaric and malic acids [

39,

40]. The phenolic potential of the grapes was also calculated [

41,

42]. Grapes were homogenized and macerated for four hours at pH 1.0. Subsequently, total phenolic content and anthocyanin concentration were quantified spectrophotometrically by measuring absorbance at 280 nm and 520 nm, respectively.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and means were separated by Duncan's multiple range test, using Statgraphics 2.0 Plus software (Statistical Graphics Corporation, USA). One- and two-way ANOVAs were used to assess the effects of rootstock and AMF inoculation each year. In the global analysis of technological and phenolic maturity parameters, a three-way ANOVA was employed to evaluate the effects of rootstock, AMF inoculation, and year, and the rootstock × AMF inoculation interaction was analyzed. Linear and nonlinear regressions were fitted using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat, Richmond, CA), and the best fit for nonlinear models was selected based on Schwarz's Bayesian criterion index (SBC). Due to the non-normal distribution of mycorrhization percentage data, non-parametric statistical tests were applied to assess differences between treatments. The Krustal-Wallis test was used when comparing more than two treatments, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparisons. When significant differences were found among more than two treatments, a Duncan post hoc test was performed.

5. Conclusions and Future Remarks

We conclude that high-vigor and water-use-efficient rootstocks such as 140Ru and 110R are better suited for establishing new plantations under semiarid conditions and in the context of climate change, as they showed higher early survival rates and fewer grafting issues compared to the low-vigor 161-49C. Based on multi-season monitoring, these results confirm that rootstock choice is the single most decisive factor for rapid vineyard establishment under hot-dry scenarios, with 140Ru providing the highest early shoot and leaf area and, consequently, the largest cumulative yield during the initial years. This superior performance of 140Ru is probably linked to its deeper, highly conductive root system, which improves soil water extraction and hydraulic conductance [

71], thereby compensating for its slightly lower intrinsic foliar nutrient concentration through a larger total photosynthetic surface. In contrast, 161-49C (although it produces grapes with a higher quality) showed nearly 50% vine loss or severe decline by year 5, corroborating external reports that indicate that this low-vigor stock is prone to graft-take failure and early chronic decline in dry climates.

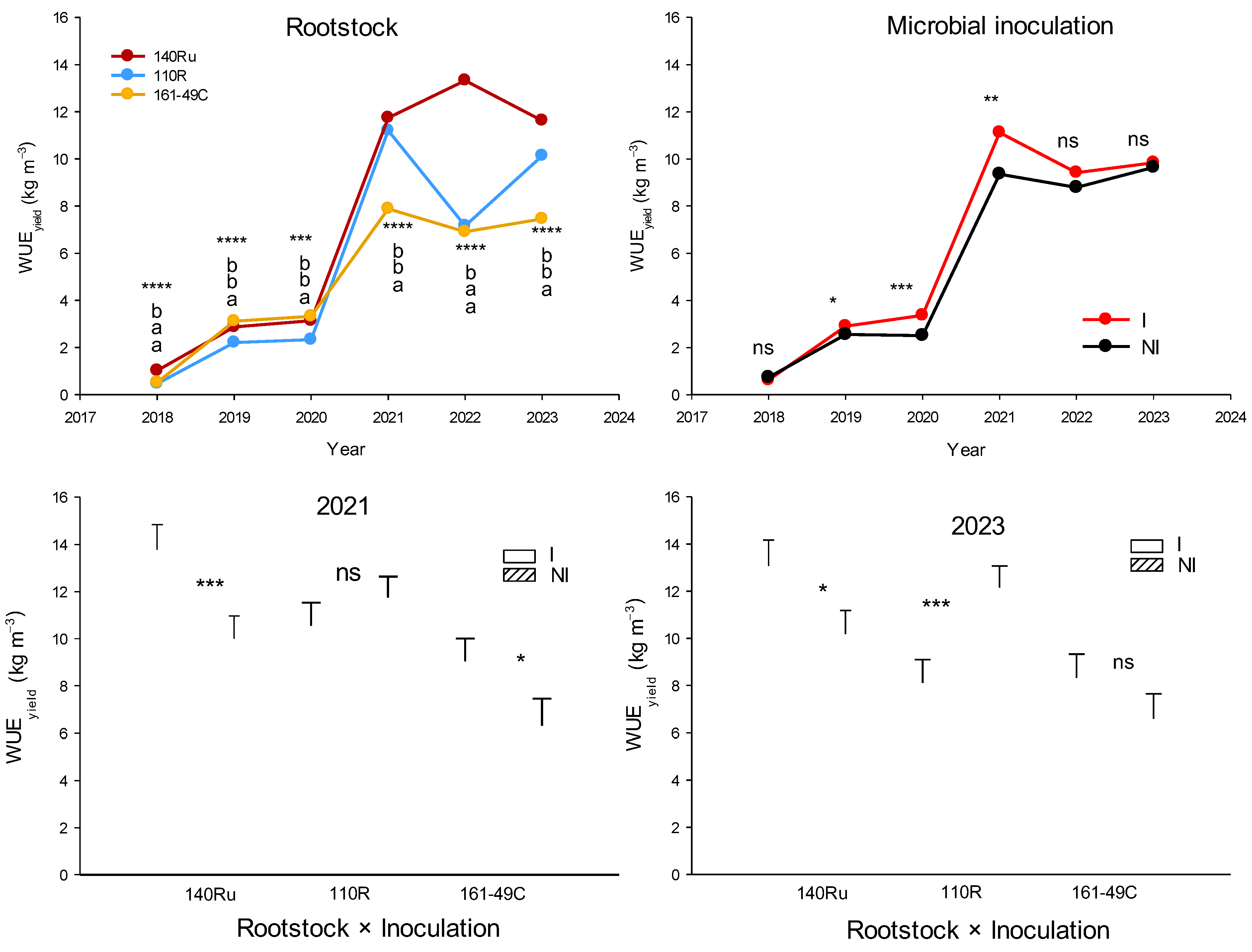

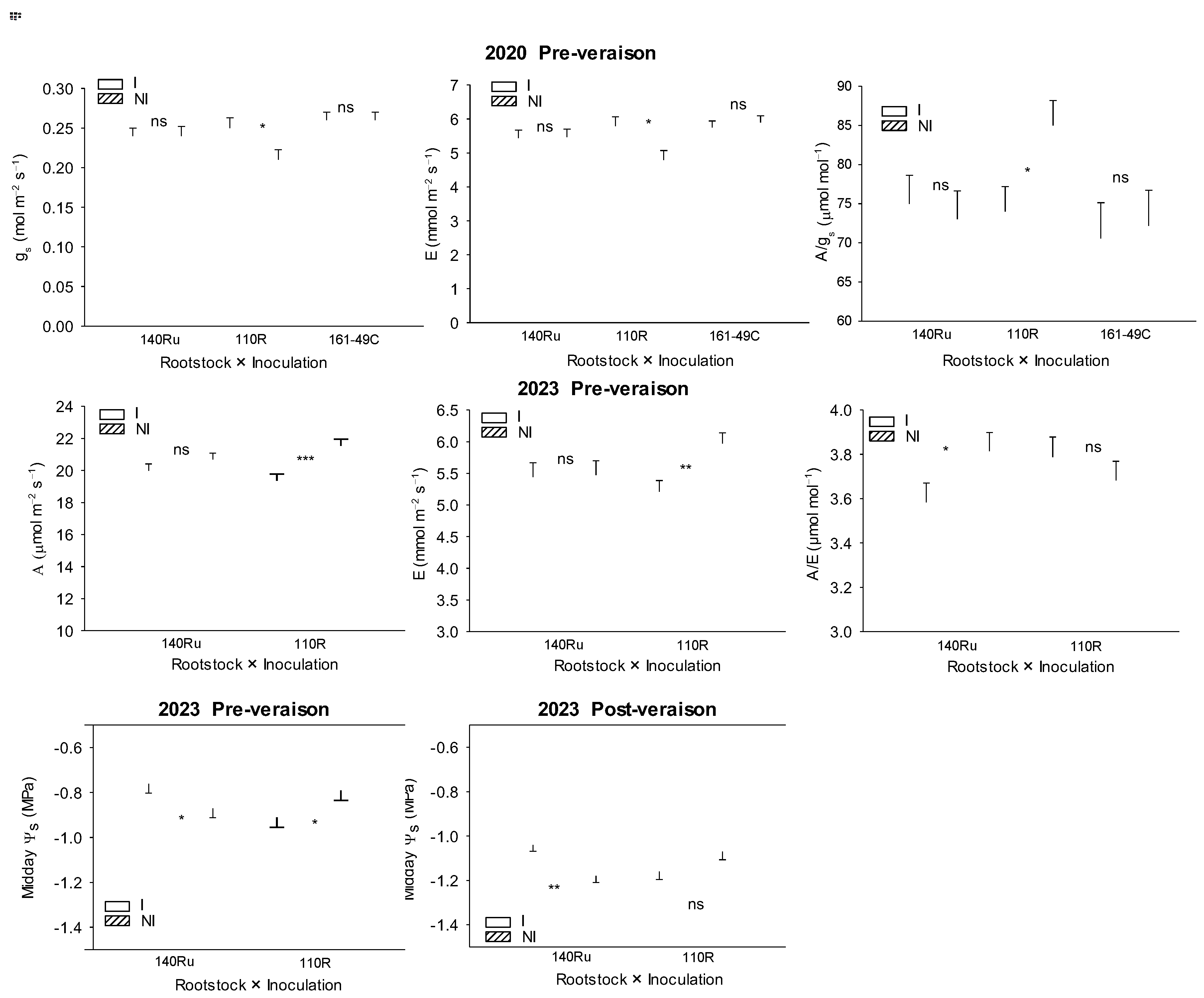

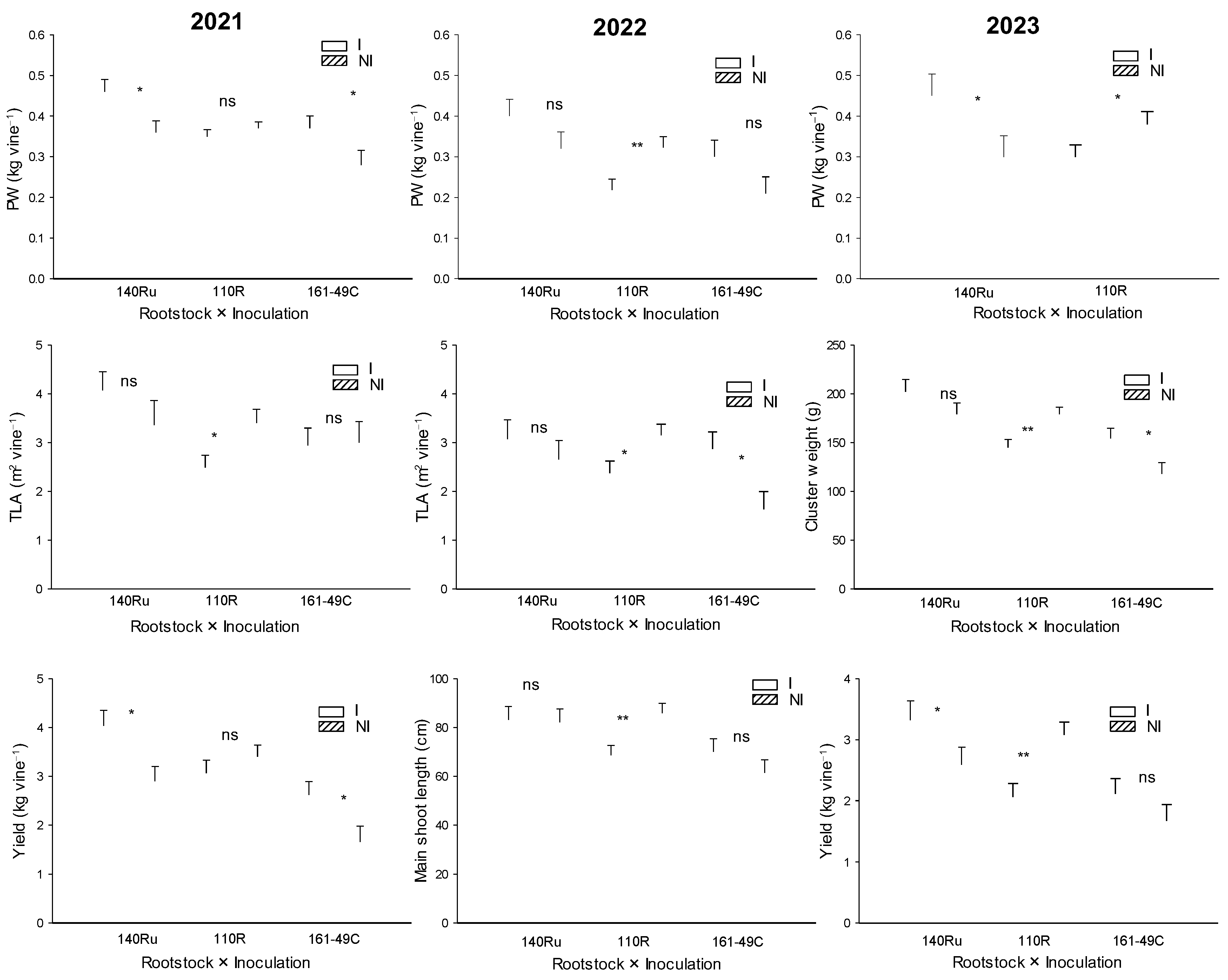

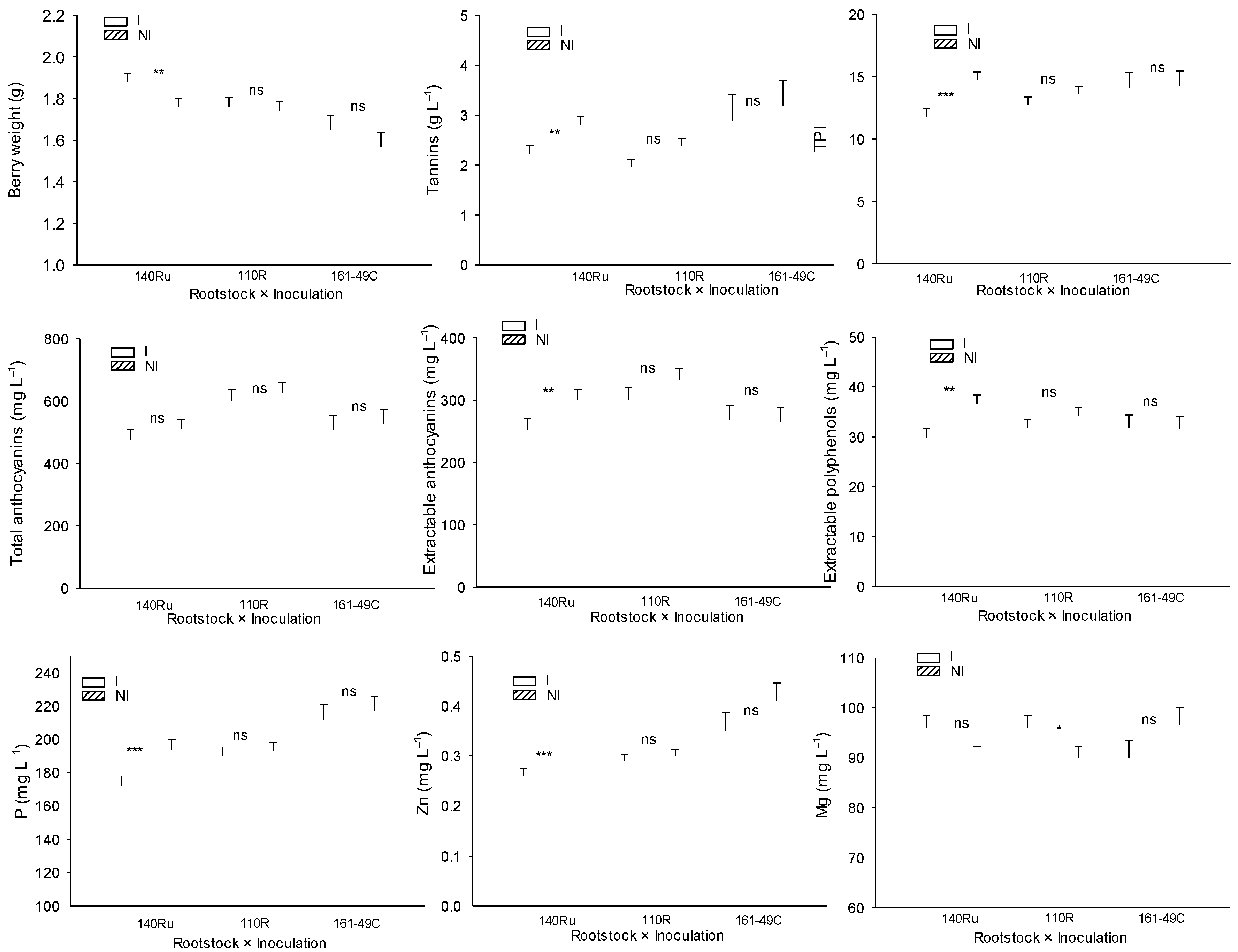

On the other hand, early microbial co-inoculation improved plant fitness in young Monastrell vines grafted onto 140Ru and 161-49C, but did not benefit vines grafted onto 110R, which exhibited a poorer overall performance under the given soil and climatic conditions. Inoculated vines on 140Ru and 161-49C developed larger canopies, higher pruning weights, and greater yields, while sustaining a better midday water status and a higher WUEyield under deficit irrigation. Conversely, inoculation slightly reduced A, Ψs, TLA, yield, and WUEyield values in 110R, suggesting a poor rootstock/microbial inoculum compatibility and a high carbohydrate-competition effect that highlights the need for a “precision inoculation” approach tailored to the AMF affinity of each of the rootstocks. Microbial inoculation also enhanced berry weight in 140Ru vines, but decreased final berry/must phenolic content. Significantly, inoculation did not alter must sugar or acidity in any of the rootstocks, and the slight drop in phenolics observed in 140Ru appears to be a dilution effect associated with larger berry size and could be counterbalanced through canopy or irrigation management.

Based on these results, the integration of microbial inoculants (such as AMF, MHB, and PGPB) into sustainable vineyard management should be approached with caution, as its effectiveness appears to depend on several factors, including the specific rootstock-microorganism interaction/affinity. Because elevated root colonization declined when annual inoculations ceased, sustained benefits would require recurring applications; therefore, the cost-to-benefit ratio must be carefully assessed.

There is also a lack of information regarding whether natural AMF/PGPB populations are sufficient to ensure adequate colonization in new vineyard plantings, as well as which factors influence their establishment. Future research should focus on long-term sustainable soil management strategies to promote native populations of beneficial fungi and bacteria already present in vineyard soils. This could include reducing pesticide use and implementing agroecological practices (such as mulching, cover cropping, and agroforestry), which not only could enhance AMF/bacterial diversity and root colonization in grapevines but also offer additional ecological services. In semiarid areas, these approaches may even prove to be more economically sustainable in the long term.

Figure 1.

Photographs showing various aspects of the experiment conducted between 2017 and 2023 on a newly established vineyard of the Monastrell variety. The study evaluated the effects of different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) under varying conditions of mycorrhization. Field microbial inoculation directly into the planting hole (A); plantlets at the beginning of the experiment in 2017–2018 (B); optical microscopy images showing the state of mycorrhization (C); Monastrell plants grafted onto the three studied rootstocks at the start of the experiment (D); various parameters explored during the experiment, including soil and plant gas exchange measurements, monitoring of organic matter degradation, root system sampling, yield control, and grape sampling for quality analysis (E); and the general condition of the vines and clusters of inoculated and non-inoculated vines grafted onto different rootstocks just before harvest (F).

Figure 1.

Photographs showing various aspects of the experiment conducted between 2017 and 2023 on a newly established vineyard of the Monastrell variety. The study evaluated the effects of different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) under varying conditions of mycorrhization. Field microbial inoculation directly into the planting hole (A); plantlets at the beginning of the experiment in 2017–2018 (B); optical microscopy images showing the state of mycorrhization (C); Monastrell plants grafted onto the three studied rootstocks at the start of the experiment (D); various parameters explored during the experiment, including soil and plant gas exchange measurements, monitoring of organic matter degradation, root system sampling, yield control, and grape sampling for quality analysis (E); and the general condition of the vines and clusters of inoculated and non-inoculated vines grafted onto different rootstocks just before harvest (F).

Figure 2.

Detailed timeline of the field experiment showing applied treatments and specific sampling events. Dashed lines represent microbial inoculations: inoculation with the AMF

Rhizophagus irregularis (4500, 800, and 4900 propagules plant

−1), the AMF

Glomus iranicum var.

tenuihypharum (4800 propagules plant

−1), the MHB

Pseudomonas mandelii strain 29 (9.8·10

8 CFU plant

−1), and the PGPR

Bacillus megaterium (7.0·10

7 CFU plant

−1). Vertical arrows indicate moments of root and soil sampling for various microbiological and root colonization analyses. The photographs visually illustrate the experimental phases: initial soil preparation, treatment applications, and inoculations (left); intermediate vegetative growth and sampling during crop development (center); final sampling, detailed root samples, microscopic observation of symbiotic structures, and final crop development (right).The commercial microbial inocula from Mycosoil and Mycostar (Agrogenia Biotech S.L.) and Mycoup (Symborg) were chosen based on their composition of AMF species typical of an area in the Region of Murcia, as well as on their previous successful application in other crops in the southeastern Spanish Mediterranean region. The last commercial AMF inoculum that was used (

R. irregularis) also contained PGPB (

B. megaterium), which solubilizes nutrients such as P and K [

29,

30]. In addition, the MHB (

P. mandelii strain 29) had also been isolated and tested by the University of Murcia as a phosphorus solubilizer that promotes mycorrhizal colonization [

12,

31].

Figure 2.

Detailed timeline of the field experiment showing applied treatments and specific sampling events. Dashed lines represent microbial inoculations: inoculation with the AMF

Rhizophagus irregularis (4500, 800, and 4900 propagules plant

−1), the AMF

Glomus iranicum var.

tenuihypharum (4800 propagules plant

−1), the MHB

Pseudomonas mandelii strain 29 (9.8·10

8 CFU plant

−1), and the PGPR

Bacillus megaterium (7.0·10

7 CFU plant

−1). Vertical arrows indicate moments of root and soil sampling for various microbiological and root colonization analyses. The photographs visually illustrate the experimental phases: initial soil preparation, treatment applications, and inoculations (left); intermediate vegetative growth and sampling during crop development (center); final sampling, detailed root samples, microscopic observation of symbiotic structures, and final crop development (right).The commercial microbial inocula from Mycosoil and Mycostar (Agrogenia Biotech S.L.) and Mycoup (Symborg) were chosen based on their composition of AMF species typical of an area in the Region of Murcia, as well as on their previous successful application in other crops in the southeastern Spanish Mediterranean region. The last commercial AMF inoculum that was used (

R. irregularis) also contained PGPB (

B. megaterium), which solubilizes nutrients such as P and K [

29,

30]. In addition, the MHB (

P. mandelii strain 29) had also been isolated and tested by the University of Murcia as a phosphorus solubilizer that promotes mycorrhizal colonization [

12,

31].

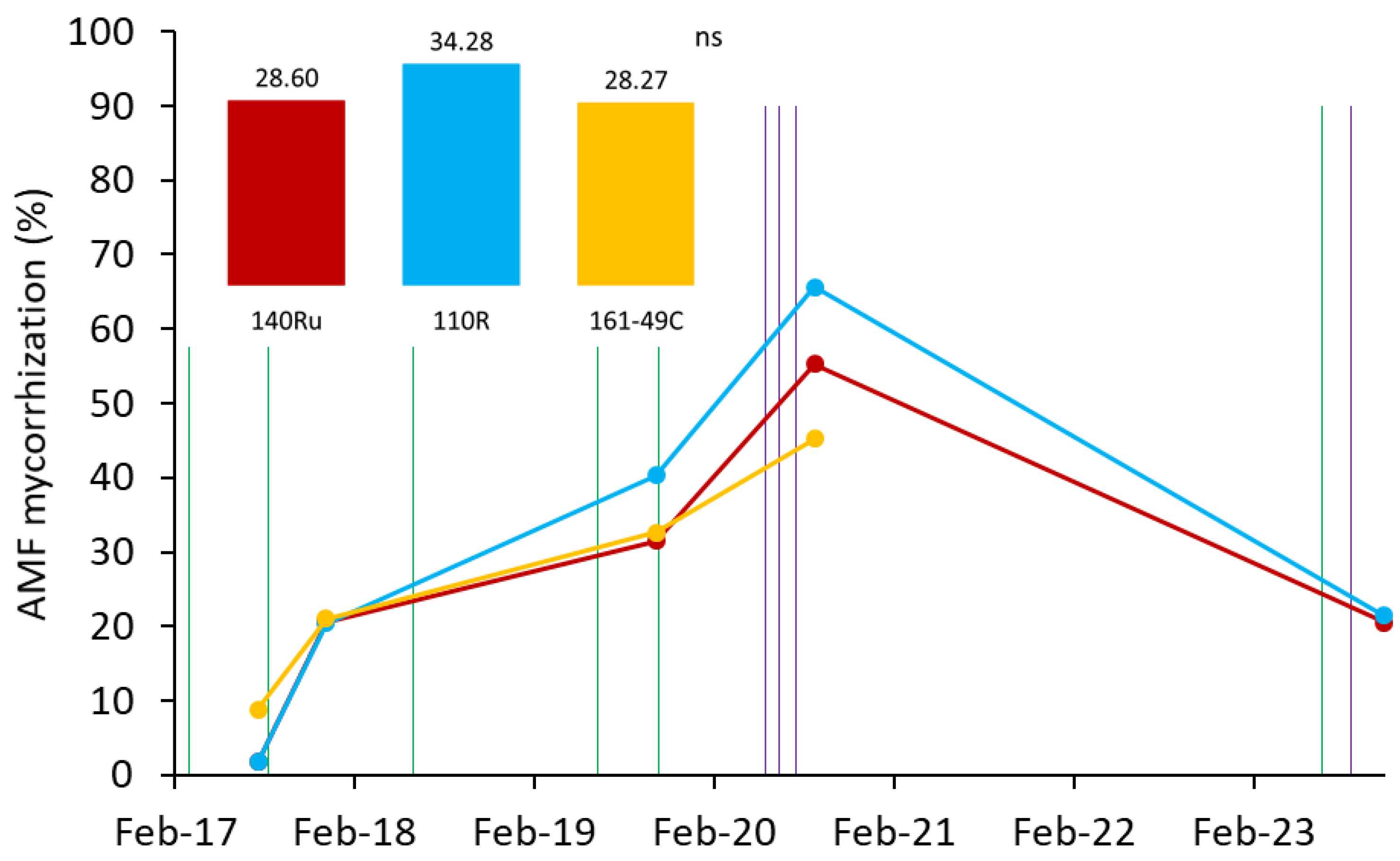

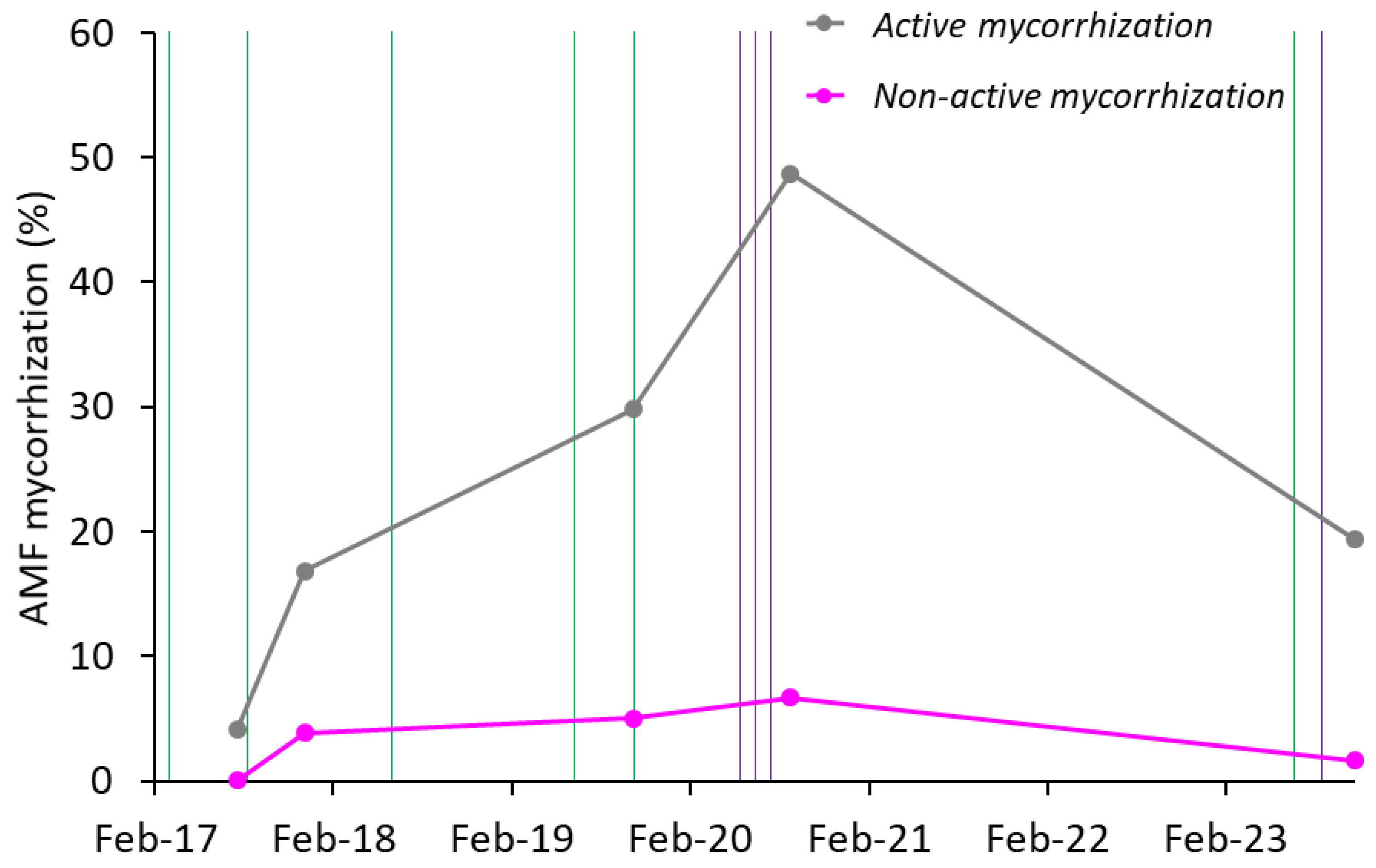

Figure 3.

Evolution of the percentage of root mycorrhization in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) during the experimental period (2017–2023). Colored bars represent the average percentage of mycorrhization for each of the rootstocks during the 2017–2020 period. Vertical lines represent the times of the AMF (green) and MHB (violet) inoculations. ns, not significant.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the percentage of root mycorrhization in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) during the experimental period (2017–2023). Colored bars represent the average percentage of mycorrhization for each of the rootstocks during the 2017–2020 period. Vertical lines represent the times of the AMF (green) and MHB (violet) inoculations. ns, not significant.

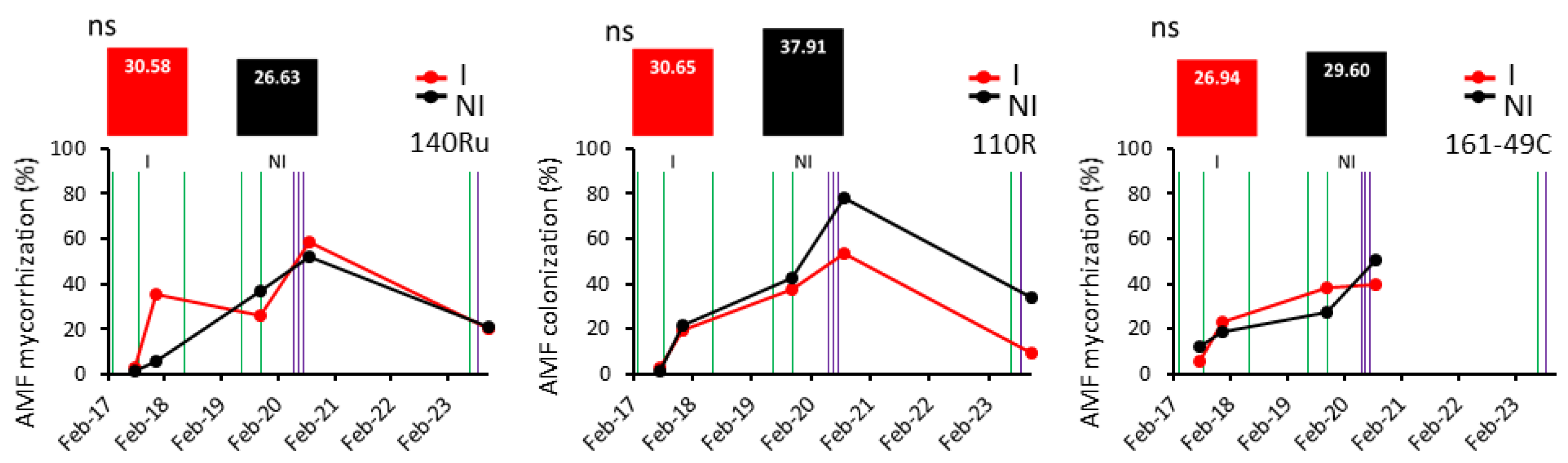

Figure 4.

Evolution of the percentage of root mycorrhization in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) during the experimental period (2017–2023). Colored bars represent the percentage of mycorrhization for each of the rootstocks during the 2017–2020 period. Vertical lines represent the times of AMF (green) and MHB (violet) inoculations. ns, not significant.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the percentage of root mycorrhization in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) during the experimental period (2017–2023). Colored bars represent the percentage of mycorrhization for each of the rootstocks during the 2017–2020 period. Vertical lines represent the times of AMF (green) and MHB (violet) inoculations. ns, not significant.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the percentage of active mycorrhization (hyphae, arbuscules, and vesicles) and non-active mycorrhization (spores) fractions during the experimental period (2017–2023), including the three rootstocks and both I and NI plants.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the percentage of active mycorrhization (hyphae, arbuscules, and vesicles) and non-active mycorrhization (spores) fractions during the experimental period (2017–2023), including the three rootstocks and both I and NI plants.

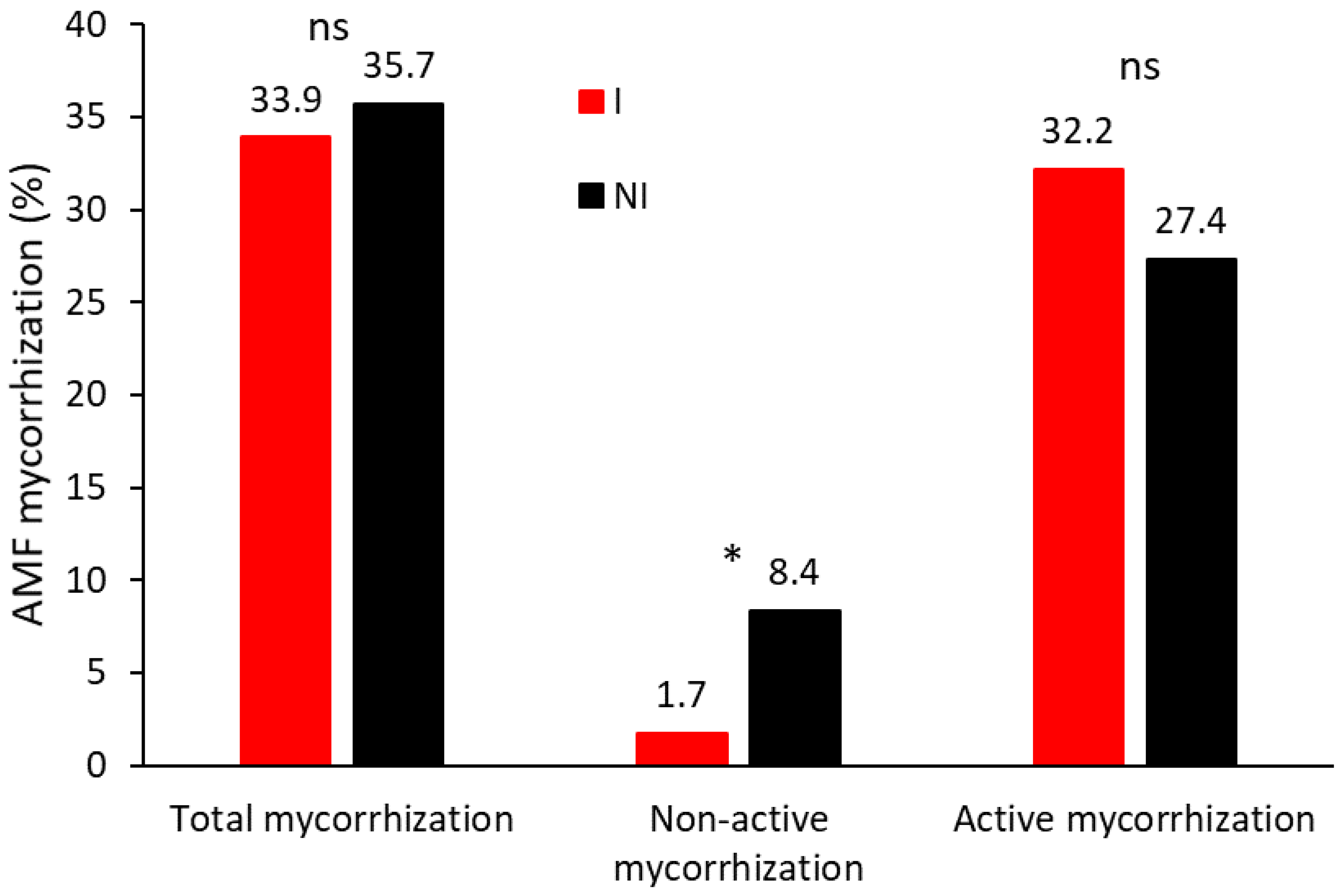

Figure 6.

Average percentage of AMF colonization in Monastrell vines under two different mycorrhizal inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) in October 2019 (after AMF inoculation but without MHB) across all of the rootstocks. Total mycorrhization includes spores and active structures (hyphae, arbuscules, and vesicles). ns, not significant; * P < 0.05, according to the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 6.

Average percentage of AMF colonization in Monastrell vines under two different mycorrhizal inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) in October 2019 (after AMF inoculation but without MHB) across all of the rootstocks. Total mycorrhization includes spores and active structures (hyphae, arbuscules, and vesicles). ns, not significant; * P < 0.05, according to the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test at a 95% confidence level.

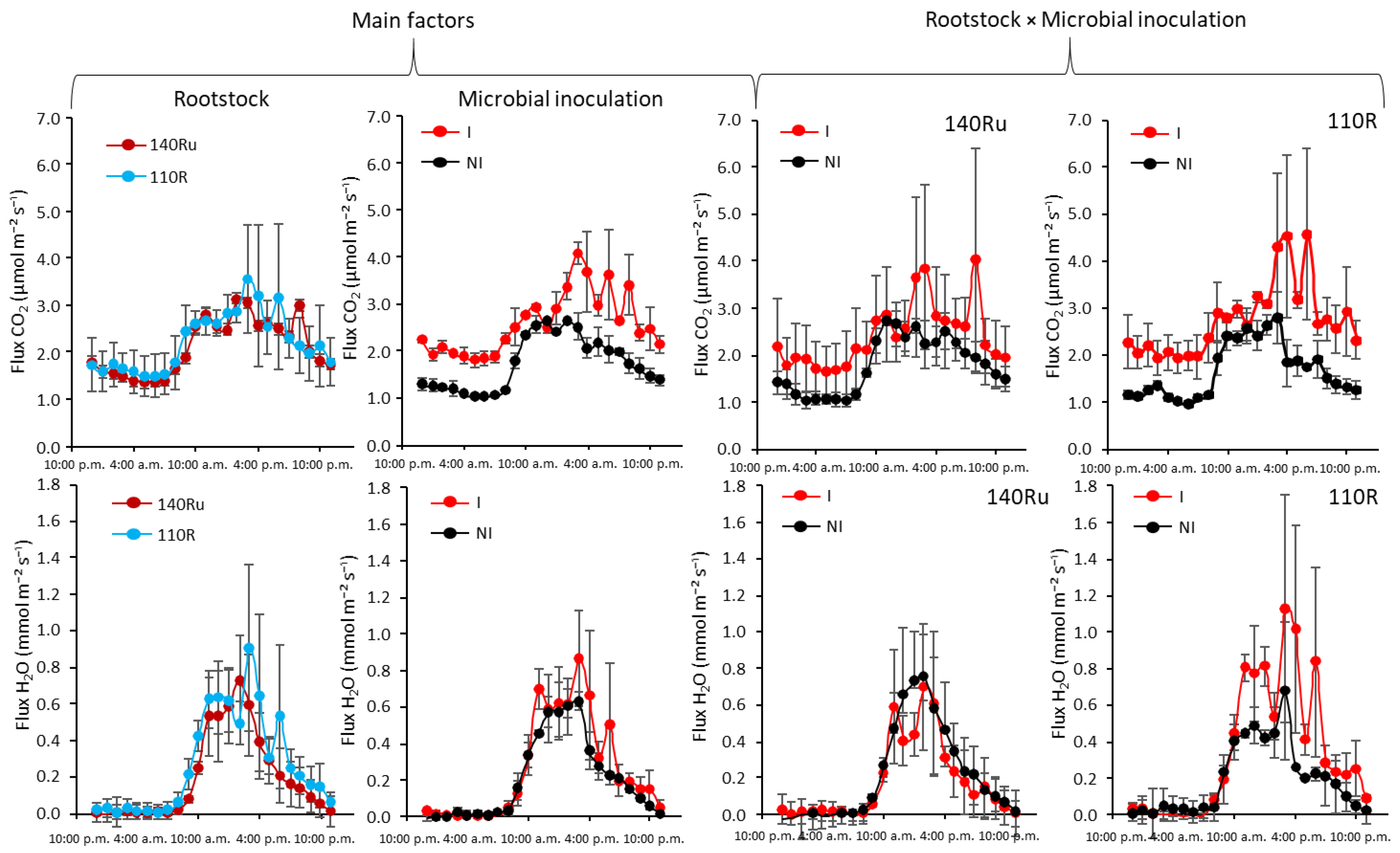

Figure 7.

Daily evolution of soil CO2 (respiration) and H2O (evaporation) fluxes measured during the post-veraison period (summer 2021), for vines on rootstocks 140Ru (maroon line) and 110R (blue line), under inoculated (I, red line) and non-inoculated (NI, black line) treatments. Left: Main effect of the rootstock (averaged across inoculation treatments); middle: Main effect of the microbial inoculation (I vs. NI); right: Rootstock × inoculation interaction. Error bars represent ± SE.

Figure 7.

Daily evolution of soil CO2 (respiration) and H2O (evaporation) fluxes measured during the post-veraison period (summer 2021), for vines on rootstocks 140Ru (maroon line) and 110R (blue line), under inoculated (I, red line) and non-inoculated (NI, black line) treatments. Left: Main effect of the rootstock (averaged across inoculation treatments); middle: Main effect of the microbial inoculation (I vs. NI); right: Rootstock × inoculation interaction. Error bars represent ± SE.

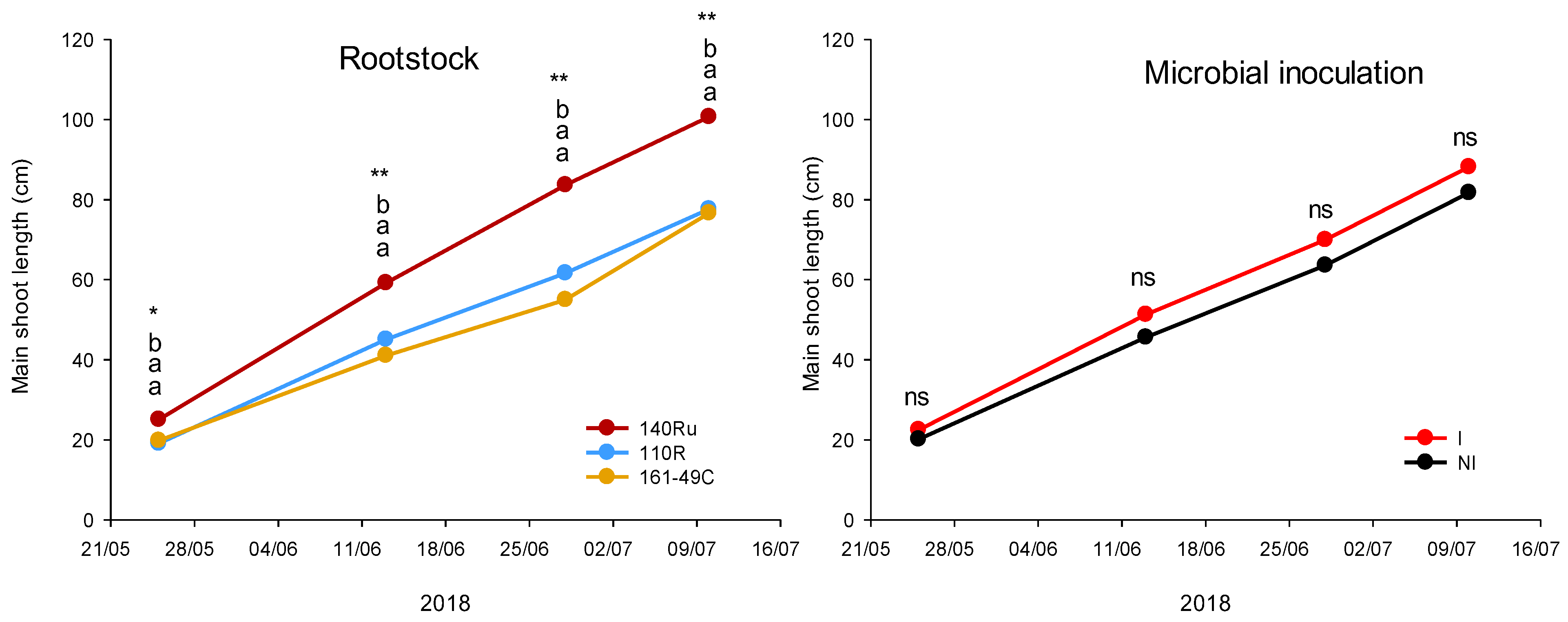

Figure 8.

Evolution of main shoot growth of Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) (A) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) (B) during 2018. ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Figure 8.

Evolution of main shoot growth of Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) (A) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) (B) during 2018. ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Figure 9.

Evolution of productive water use efficiency (WUEyield) in Monastrell vines grafted onto different rootstocks and under two microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) during the experimental period (2018–2023). Values of WUEyield for each of the rootstocks and for both inoculated and non-inoculated plants in 2021 and 2023 (one-way analysis). ns, not significant; * P < 0.1, ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01; **** P < 0.001 Differences between the mean values for each of the rootstocks were determined using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 9.

Evolution of productive water use efficiency (WUEyield) in Monastrell vines grafted onto different rootstocks and under two microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) during the experimental period (2018–2023). Values of WUEyield for each of the rootstocks and for both inoculated and non-inoculated plants in 2021 and 2023 (one-way analysis). ns, not significant; * P < 0.1, ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01; **** P < 0.001 Differences between the mean values for each of the rootstocks were determined using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 10.

Significant differences in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI), in leaf gas exchange parameters (A, leaf photosynthesis rate; gs, stomatal conductance rate; E, leaf transpiration rate; A/gs, intrinsic leaf water use efficiency, for years 2020 and 2023, and midday stem water potential [Ψs], for the pre- and post-veraison periods of 2023). For each of the rootstocks, one-way ANOVA was performed for each of the physiological parameters. ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P <0.001. Mean values for each of the rootstocks were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 10.

Significant differences in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI), in leaf gas exchange parameters (A, leaf photosynthesis rate; gs, stomatal conductance rate; E, leaf transpiration rate; A/gs, intrinsic leaf water use efficiency, for years 2020 and 2023, and midday stem water potential [Ψs], for the pre- and post-veraison periods of 2023). For each of the rootstocks, one-way ANOVA was performed for each of the physiological parameters. ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P <0.001. Mean values for each of the rootstocks were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 11.

Significant interactive effects between rootstock and microbial inoculation on vegetative (main shoot length; total leaf area, TLA; winter pruning weight, PW), and reproductive parameters in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI), for the years 2021, 2022, and 2023. For each of the rootstocks, a one-way ANOVA was performed for each vegetative and reproductive parameter. ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. Mean values for each of the rootstocks were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 11.

Significant interactive effects between rootstock and microbial inoculation on vegetative (main shoot length; total leaf area, TLA; winter pruning weight, PW), and reproductive parameters in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI), for the years 2021, 2022, and 2023. For each of the rootstocks, a one-way ANOVA was performed for each vegetative and reproductive parameter. ns, not significant; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. Mean values for each of the rootstocks were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 12.

Mean values of berry weight, berry phenolic quality parameters, and must mineral content in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI), during the experimental period (2018–2023). ns, not significant; * P < 0.1; ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01. Significant differences between the mean values for each of the rootstocks were determined using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Figure 12.

Mean values of berry weight, berry phenolic quality parameters, and must mineral content in Monastrell vines grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI), during the experimental period (2018–2023). ns, not significant; * P < 0.1; ** P < 0.05; *** P < 0.01. Significant differences between the mean values for each of the rootstocks were determined using Duncan's multiple range test at a 95% confidence level.

Table 1.

Annual applied volume of irrigation water and mean values of key climatic parameters for each year of the experiment in the study area.

Table 1.

Annual applied volume of irrigation water and mean values of key climatic parameters for each year of the experiment in the study area.

| Year |

Irrigation (mm year−1) |

ETo (mm year−1) |

VPD (kPa) |

Rainfall (mm year−1) |

Tmax (°C) |

Tmean (°C) |

Tmin (°C) |

RHmean (%) |

Solar rad. (W m−2) |

Daily sunshine (hours) |

| |

High irrigation conditions |

| 2018 |

274.4 |

1162 |

0.92 |

392 |

22.46 |

14.98 |

7.59 |

61.79 |

200.07 |

9.43 |

| 2019 |

283.1 |

1173 |

0.98 |

427 |

23.03 |

15.08 |

6.99 |

60.24 |

206.30 |

9.49 |

| 2020 |

304.0 |

1106 |

0.97 |

393 |

23.34 |

15.28 |

8.07 |

63.26 |

202.14 |

9.42 |

| |

Deficit irrigation conditions |

| 2021 |

103.5 |

1100 |

0.93 |

321 |

23.10 |

15.36 |

7.57 |

63.66 |

197.32 |

9.32 |

| 2022 |

89.4 |

1200 |

1.09 |

300 |

25.03 |

16.13 |

7.33 |

61.80 |

191.80 |

9.45 |

| 2023 |

90.6 |

1105 |

1.09 |

162 |

24.55 |

15.81 |

7.04 |

57.25 |

203.98 |

9.43 |

Table 2.

Mean values of total glomalin (TG) in the soil at the end of the experiment in 2023, mean values of oxygen diffusion rate (ODR) in the soil in pre- and post-veraison of 2021, and mean values of TBI parameters (stabilization factor S, and decomposition rate constant k) measured in 2019. Data were recorded for rootstocks 140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C in inoculated (I) and non-inoculated (NI) treatments.

Table 2.

Mean values of total glomalin (TG) in the soil at the end of the experiment in 2023, mean values of oxygen diffusion rate (ODR) in the soil in pre- and post-veraison of 2021, and mean values of TBI parameters (stabilization factor S, and decomposition rate constant k) measured in 2019. Data were recorded for rootstocks 140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C in inoculated (I) and non-inoculated (NI) treatments.

| Rootstock (R) |

TG (μg g−1 soil DW) |

ODR (μg m−2 s−1) |

S |

k |

S/k |

| Pre-veraison |

Post-veraison |

| 140Ru |

2267 |

62.8 |

48.5 |

0.23 |

0.019 |

14.3 |

| 110R |

2194 |

54.8 |

44.5 |

0.21 |

0.019 |

12.1 |

| 161-49C |

- |

56.6 |

44.7 |

- |

- |

- |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

2378 |

58.3 |

46.9 |

0.22 |

0.023 |

10.5 |

| NI |

2083 |

57.8 |

45.0 |

0.22 |

0.016 |

15.9 |

| R × MI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 140Ru |

I |

2580b |

65.8 |

49.6b |

0.22 |

0.024 |

10.1 |

| |

NI |

1953a |

59.8 |

47.5ab |

0.24 |

0.015 |

18.5 |

| 110R |

I |

2176ab |

53.5 |

41.6ab |

0.21 |

0.021 |

10.9 |

| |

NI |

2212ab |

56.1 |

47.5ab |

0.21 |

0.017 |

13.3 |

| 161-49C |

I |

- |

55.6 |

49.6b |

- |

- |

- |

| |

NI |

- |

57.6 |

39.9a |

- |

- |

- |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

*** |

*** |

| R × MI |

* |

ns |

* |

ns |

ns |

ns |

Table 3.

Mean values of leaf gas exchange parameters in the early morning (9:00 a.m.–10:30 a.m.) and midday stem water potential (12:30 p.m.–2:00 p.m.) measured in Monastrell young plants (from 1 to 6 years old) grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) for each of the years and in two different phenological periods (pre- and post-veraison) during the experimental period (2018–2023). A, net photosynthesis rate (μmol m−2 s−1); gs, stomatal conductance rate (mol m−2 s−1); E, transpiration rate (mmol m−2 s−1); A/gs, intrinsic leaf water use efficiency (μmol CO2 mol−1 H2O); A/E, instantaneous leaf water use efficiency (μmol CO2 mmol−1 H2O); Ψs, midday stem water potential (MPa).

Table 3.

Mean values of leaf gas exchange parameters in the early morning (9:00 a.m.–10:30 a.m.) and midday stem water potential (12:30 p.m.–2:00 p.m.) measured in Monastrell young plants (from 1 to 6 years old) grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) for each of the years and in two different phenological periods (pre- and post-veraison) during the experimental period (2018–2023). A, net photosynthesis rate (μmol m−2 s−1); gs, stomatal conductance rate (mol m−2 s−1); E, transpiration rate (mmol m−2 s−1); A/gs, intrinsic leaf water use efficiency (μmol CO2 mol−1 H2O); A/E, instantaneous leaf water use efficiency (μmol CO2 mmol−1 H2O); Ψs, midday stem water potential (MPa).

| |

Pre-veraison |

Post-veraison |

| |

A |

gs |

E |

A/gs |

A/E |

Ψs

|

A |

gs |

E |

A/gs |

A/E |

Ψs

|

| Rootstock (R) |

2018 |

| 140Ru |

18.8 |

0.160 |

4.6 |

140 |

4.7 |

−0.69 |

17.0a |

0.239a |

5.8 |

78 |

3.0 |

−0.75 |

| 110R |

18.4 |

0.156 |

4.6 |

136 |

4.5 |

−0.68 |

18.3b |

0.279b |

6.3 |

70 |

3.0 |

−0.75 |

| 161-49C |

17.9 |

0.137 |

4.1 |

152 |

4.9 |

−0.68 |

17.7ab |

0.268ab |

6.3 |

70 |

2.9 |

−0.75 |

| Microbial inoculation(MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

18.7 |

0.158 |

4.6 |

139 |

4.6 |

−0.69 |

18.1 |

0.270 |

6.4 |

72 |

2.9 |

−0.76 |

| NI |

18.0 |

0.144 |

4.2 |

146 |

4.9 |

−0.67 |

17.2 |

0.254 |

5.8 |

73 |

3.1 |

−0.74 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

* |

* |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

* |

ns |

* |

ns |

** |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2020 |

| 140Ru |

17.2 |

0.241 |

5.5ab |

74.2 |

3.2a |

- |

14.4 |

0.168ab |

4.5a |

91.9ab |

3.4 |

- |

| 110R |

18.0 |

0.231 |

5.3a |

79.4 |

3.5b |

- |

13.7 |

0.156a |

4.3a |

94.6b |

3.4 |

- |

| 161-49C |

17.8 |

0.256 |

5.8b |

71.4 |

3.1a |

- |

15.3 |

0.210b |

5.3b |

78.5a |

3.0 |

- |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

17.8 |

0.250 |

5.7 |

73.1 |

3.2 |

- |

14.7 |

0.181 |

4.8 |

85.9 |

3.2 |

- |

| NI |

17.5 |

0.235 |

5.4 |

76.8 |

3.4 |

- |

14.3 |

0.175 |

4.6 |

90.8 |

3.3 |

- |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

* |

ns |

*** |

- |

ns |

** |

** |

* |

ns |

- |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

- |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

- |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

** |

ns |

** |

- |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

- |

| Rootstock (R) |

2021 |

| 140Ru |

15.0 |

0.164 |

4.0 |

95.4 |

3.8 |

−0.97 |

12.5 |

0.117 |

2.9 |

117.7 |

4.6 |

−1.28b |

| 110R |

14.8 |

0.168 |

4.0 |

93.2 |

3.7 |

−1.02 |

12.6 |

0.119 |

2.9 |

115.2 |

4.5 |

−1.24b |

| 161-49C |

15.0 |

0.156 |

3.9 |

97.1 |

3.9 |

−1.07 |

11.4 |

0.115 |

2.8 |

113.3 |

4.3 |

−1.39a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

14.8 |

0.159 |

3.9 |

97.3 |

3.8 |

−1.04 |

11.7 |

0.114 |

2.8 |

113.5 |

4.3 |

−1.30 |

| NI |

14.9 |

0.166 |

4.0 |

93.1 |

3.8 |

−1.00 |

12.7 |

0.120 |

2.9 |

117.4 |

4.6 |

−1.30 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

* |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

** |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2023 |

| 140Ru |

20.3 |

- |

5.6 |

- |

3.7 |

−0.81 |

14.0 |

0.148 |

3.9 |

103.0 |

3.8 |

−1.11 |

| 110R |

20.5 |

- |

5.6 |

- |

3.7 |

−0.85 |

13.9 |

0.138 |

4.0 |

105.3 |

3.7 |

−1.12 |

| 161-49C |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

19.7 |

- |

5.4 |

- |

3.7 |

−0.83 |

13.5 |

0.129 |

3.6 |

107.7 |

3.9 |

−1.10 |

| NI |

21.1 |

- |

5.8 |

- |

3.8 |

−0.83 |

14.5 |

0.157 |

4.3 |

100.5 |

3.6 |

−1.12 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

- |

ns |

- |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| MI |

*** |

- |

** |

- |

ns |

ns |

* |

** |

** |

* |

ns |

ns |

| R × MI |

* |

- |

** |

- |

* |

** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

** |

Table 4.

Leaf mineral concentration in Monastrell plants at veraison grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) in 2018, 2021, and 2023. N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and Na in % in DW, Fe, Cu, Mn, Zn, and B in mg L−1.

Table 4.

Leaf mineral concentration in Monastrell plants at veraison grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) in 2018, 2021, and 2023. N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and Na in % in DW, Fe, Cu, Mn, Zn, and B in mg L−1.

| |

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

Na |

Fe |

Zn |

Mn |

Cu |

B |

| Rootstock (R) |

2018 |

| 140Ru |

3.0a |

0.158a |

0.62a |

2.15 |

0.45b |

0.044a |

75.6 |

19.1 |

147 |

11.1 |

38.3 |

| 110R |

3.2b |

0.179b |

0.73b |

1.94 |

0.36a |

0.047a |

76.5 |

18.3 |

133 |

11.5 |

49.1 |

| 161-49C |

3.2b |

0.178b |

0.75b |

2.08 |

0.35a |

0.059b |

68.1 |

19.2 |

153 |

12.3 |

43.3 |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

3.2 |

0.175 |

0.72 |

2.03 |

0.39 |

0.047 |

70.5 |

18.7 |

146 |

11.6 |

42.8 |

| NI |

3.1 |

0.169 |

0.67 |

2.08 |

0.38 |

0.053 |

76.4 |

19.1 |

143 |

11.6 |

44.3 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

** |

** |

** |

ns |

**** |

** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2021 |

| 140Ru |

2.52 |

0.142 |

0.65 |

1.64 |

0.33b |

0.053b |

84.7 |

33.8 |

133ab |

14.4 |

27.7a |

| 110R |

2.47 |

0.139 |

0.65 |

1.62 |

0.28a |

0.040a |

83.7 |

32.9 |

125a |

13.1 |

31.5b |

| 161-49C |

2.43 |

0.138 |

0.69 |

1.67 |

0.26a |

0.037a |

82.5 |

35.3 |

145b |

13.9 |

25.6a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

2.48 |

0.140 |

0.68 |

1.67 |

0.30 |

0.033 |

80.6 |

36.6 |

136 |

13.7 |

27.8 |

| NI |

2.47 |

0.139 |

0.65 |

1.62 |

0.29 |

0.054 |

86.7 |

31.4 |

132 |

13.9 |

28.7 |

|

R × MI

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 140Ru |

I |

2.51 |

0.144 |

0.69 |

1.74bc |

0.34d |

0.032a |

80.7 |

35.7 |

135bc |

14.5bc |

27.9 |

| |

NI |

2.53 |

0.139 |

0.62 |

1.54a |

0.32cd |

0.075c |

88.6 |

31.9 |

131ab |

14.4bc |

27.4 |

| 110R |

I |

2.41 |

0.139 |

0.64 |

1.68abc |

0.31cd |

0.033a |

79.3 |

36.0 |

135bc |

13.9abc |

31.6 |

| |

NI |

2.53 |

0.139 |

0.65 |

1.57a |

0.26ab |

0.047b |

88.2 |

29.8 |

115a |

12.2a |

31.3 |

| 161-49C |

I |

2.52 |

0.137 |

0.70 |

1.59ab |

0.24a |

0.033a |

81.8 |

38.0 |

139bc |

12.6ab |

23.9 |

| |

NI |

2.35 |

0.139 |

0.67 |

1.76c |

0.29bc |

0.040ab |

83.3 |

32.5 |

151c |

15.2c |

27.3 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

*** |

*** |

ns |

ns |

*** |

ns |

*** |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

*** |

** |

*** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

*** |

*** |

*** |

ns |

ns |

** |

*** |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2023 |

| 140Ru |

2.27 |

0.111 |

0.64 |

1.63 |

0.35 |

0.017 |

65.2 |

28.3 |

133 |

18.3 |

48.9 |

| 110R |

2.25 |

0.111 |

0.62 |

1.60 |

0.29 |

0.016 |

63.4 |

28.0 |

119 |

20.2 |

48.2 |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

2.26 |

0.116 |

0.68 |

1.63 |

0.34 |

0.016 |

66.0 |

28.7 |

134 |

23.4 |

52.9 |

| NI |

2.26 |

0.108 |

0.58 |

1.59 |

0.30 |

0.018 |

62.5 |

27.6 |

119 |

15.2 |

44.1 |

|

R × MI

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 140Ru |

I |

2.27 |

0.116 |

0.66 |

1.72b |

0.38b |

0.016 |

65.5 |

26.9a |

141 |

19.3a |

57.3 |

| |

NI |

2.27 |

0.107 |

0.62 |

1.53a |

0.32a |

0.019 |

64.8 |

29.7ab |

126 |

17.4a |

40.4 |

| 110R |

I |

2.26 |

0.115 |

0.71 |

1.54a |

0.29a |

0.015 |

66.6 |

30.4b |

127 |

27.4b |

48.6 |

| |

NI |

2.25 |

0.109 |

0.54 |

1.65ab |

0.29a |

0.017 |

60.2 |

25.5a |

111 |

13.0a |

47.8 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

*** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| MI |

ns |

*** |

** |

ns |

** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

*** |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

* |

* |

ns |

ns |

*** |

ns |

** |

ns |

Table 5.

Mean values of vegetative (main shoot length; total leaf area, TLA; winter pruning weight, PW), and reproductive parameters of Monastrell plants grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) for each of the years during the experimental period (2018–2023).

Table 5.

Mean values of vegetative (main shoot length; total leaf area, TLA; winter pruning weight, PW), and reproductive parameters of Monastrell plants grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) for each of the years during the experimental period (2018–2023).

| |

Main shoot length (cm) |

TLA

(m2 vine−1)

|

PW

(kg vine−1)

|

Yield

(kg vine−1)

|

Number of clusters vine−1 |

Cluster weight (g) |

| Rootstock (R) |

2018 |

| 140Ru |

101b |

1.42b |

0.24 |

0.79b |

4.4b |

184 |

| 110R |

78a |

1.11a |

0.22 |

0.35a |

2.4a |

147 |

| 161-49C |

77a |

1.15a |

0.25 |

0.32a |

2.1a |

129 |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

88 |

1.20 |

0.28 |

0.47 |

2.9 |

153 |

| NI |

82 |

1.26 |

0.19 |

0.50 |

3.0 |

154 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

** |

*** |

ns |

*** |

*** |

ns |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

*** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock |

2019 |

| 140Ru |

68 |

1.75 |

0.19b |

2.27b |

17.4 |

131ab |

| 110R |

67 |

1.61 |

0.15a |

1.75a |

15.1 |

118a |

| 161-49C |

78 |

2.08 |

0.17ab |

2.42b |

16.4 |

146b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

76 |

2.00 |

0.18 |

2.33 |

16.4 |

144 |

| NI |

66 |

1.62 |

0.16 |

1.96 |

16.1 |

119 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

ns |

ns |

** |

*** |

ns |

*** |

| MI |

* |

ns |

ns |

* |

ns |

*** |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2020 |

| 140Ru |

94b |

2.88b |

0.41 |

2.68b |

11.3b |

212b |

| 110R |

83a |

2.37a |

0.40 |

2.02a |

9.8a |

188a |

| 161-49C |

95b |

2.97b |

0.45 |

2.81b |

11.6b |

221b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

96 |

3.02 |

0.44 |

2.87 |

12.0 |

219 |

| NI |

85 |

2.46 |

0.40 |

2.14 |

9.7 |

195 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

*** |

*** |

ns |

*** |

* |

*** |

| MI |

*** |

*** |

ns |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2021 |

| 140Ru |

113b |

3.72b |

0.41b |

3.37b |

17.8b |

178b |

| 110R |

95a |

2.95a |

0.36ab |

3.17b |

18.5b |

161b |

| 161-49C |

91a |

2.98a |

0.33a |

2.09a |

15.9a |

115a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

103 |

3.17 |

0.39 |

3.10 |

17.7 |

159 |

| NI |

97 |

3.26 |

0.34 |

2.67 |

17.2 |

144 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

*** |

* |

*** |

*** |

** |

*** |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

** |

** |

ns |

** |

| R × MI |

ns |

* |

** |

** |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2022 |

| 140Ru |

83b |

2.86 |

0.38b |

3.35b |

16.0b |

188 |

| 110R |

77 |

2.76 |

0.27a |

1.77a |

11.4a |

297 |

| 161-49C |

66a |

2.42 |

0.26a |

1.71a |

10.5a |

142 |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

74 |

2.77 |

0.31 |

2.36 |

13.0 |

263 |

| NI |

77 |

2.59 |

0.29 |

2.20 |

12.3 |

155 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

*** |

ns |

*** |

*** |

*** |

ns |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| R × MI |

** |

** |

** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Rootstock (R) |

2023 |

| 140Ru |

99 |

2.66 |

0.37 |

2.95b |

13.7b |

191c |

| 110R |

73 |

1.84 |

0.30 |

2.57b |

14.2b |

162b |

| 161-49C |

- |

- |

- |

1.96a |

11.7a |

140a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

86 |

2.48 |

0.33 |

2.52 |

12.7 |

169 |

| NI |

87 |

2.02 |

0.34 |

2.47 |

13.7 |

160 |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

*** |

* |

* |

*** |

** |

*** |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

* |

*** |

** |

*** |

Table 6.

Technological maturity parameters of Monastrell grape must at harvest, grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) from 2018 to 2023. Mean values are an average of five years, except for the sugar content, that uses the average of three years: berry weight (g), CI (color intensity), TSS (total soluble solids, °Brix), TA (titratable acidity, g tartaric acid L−1), MI (maturity index, TSS/TA), malic acid, tartaric acid (g L−1), glucose, fructose, and total sugar content (g L−1), anthocyanins/TSS (mg L−1 °Brix−1).

Table 6.

Technological maturity parameters of Monastrell grape must at harvest, grafted onto three different rootstocks (140Ru, 110R, and 161-49C) and under two different microbial inoculation conditions (I vs. NI) from 2018 to 2023. Mean values are an average of five years, except for the sugar content, that uses the average of three years: berry weight (g), CI (color intensity), TSS (total soluble solids, °Brix), TA (titratable acidity, g tartaric acid L−1), MI (maturity index, TSS/TA), malic acid, tartaric acid (g L−1), glucose, fructose, and total sugar content (g L−1), anthocyanins/TSS (mg L−1 °Brix−1).

| Rootstock (R) |

Berry weight |

CI |

TSS |

TA |

MI |

pH |

Malic acid |

Tartaric acid |

Tartaric/malic acid ratio |

Total solutes berry−1 |

Total soluble sugars |

Glucose |

Fructose |

Anthocyanins/TSS |

| 140Ru |

1.88b |

3.99a |

21.83a |

3.60b |

70a |

4.20b |

2.00b |

3.26 |

1.66a |

0.41b |

302ab |

146ab |

156ab |

19.1a |

| 110R |

1.84b |

4.66b |

22.65b |

3.43a |

77b |

4.21b |

1.64a |

3.37 |

2.31b |

0.41b |

328b |

160b |

168b |

23.6b |

| 161-49C |

1.68a |

4.38b |

21.59a |

3.52ab |

71a |

4.09a |

1.54a |

3.27 |

2.54b |

0.37a |

281a |

137a |

144a |

26.2b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

1.84 |

4.33 |

22.09 |

3.47 |

73 |

4.17 |

1.71 |

3.30 |

2.22 |

0.41 |

310 |

151 |

159 |

22.1 |

| NI |

1.77 |

4.36 |

21.97 |

3.56 |

72 |

4.16 |

1.74 |

3.31 |

2.11 |

0.39 |

297 |

144 |

153 |

23.8 |

| Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2018 |

1.87bc |

4.64b |

22.70c |

4.23c |

54a |

4.17ab |

3.03d |

3.89c |

1.35a |

0.42c |

- |

- |

- |

11.1a |

| 2020 |

1.92bc |

4.16b |

24.98d |

4.27c |

58a |

4.18ab |

1.74c |

3.64c |

2.24b |

0.47d |

- |

- |

- |

16.2a |

| 2021 |

1.47a |

4.25b |

19.10a |

3.89b |

54a |

4.06a |

1.59bc |

3.06b |

2.22b |

0.29a |

347 |

165b |

182b |

35.7b |

| 2022 |

1.96c |

3.56a |

23.13c |

2.64a |

114c |

4.16ab |

0.85a |

1.27a |

1.53a |

0.46cd |

290 |

143a |

146a |

16.1a |

| 2023 |

1.79b |

5.12c |

20.92b |

2.54a |

83b |

4.26b |

1.43b |

4.65d |

3.51c |

0.38b |

274 |

135a |

139a |

35.8b |

| ANOVA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R |

*** |

*** |

*** |

** |

*** |

* |

*** |

ns |

*** |

*** |

* |

* |

* |

*** |

| MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Year |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| R × MI |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |