1. Introduction

Cultural heritage serves not only as a critical foundation for safeguarding cultural diversity but also as a persistent driver for promoting sustainable social, economic, and environmental development [

1] (SDGs 11.4). The 2011 UNESCO

Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape(HUL) emphasises the layering process and holistic conservation of historic cities. It advocates adopting a landscape approach to integrate the protection and management of cultural heritage into broader frameworks for urban sustainable development [

2]. This underscores the pivotal role of cultural heritage as a core element of urban identity and collective memory, essential for sustaining cultural diversity, fostering social cohesion, and enhancing ecological adaptation.

Focusing on the Chinese urban context, temples, as a distinctive form of architectural cultural heritage characterised by a long history, wide distribution, and rich spiritual significance, have consistently served a vital role in numerous Chinese historic cities [

3]. They serve not only as material embodiments of religious belief but also as concentrated expressions of historical memory, traditional craftsmanship, and local ecological wisdom [

4]. Their significance extends beyond their visual landmark function in the physical landscape; they also contribute to maintaining cultural diversity, fostering social cohesion, and supporting ecosystem balance [

5], exhibiting outstanding potential to act as “sustainable cultural markers” within historic cities. Therefore, understanding and activating the multifunctional roles and multidimensional values of temples is essential for advancing historic urban sustainability.

However, existing research predominantly focuses on static conservation of urban heritage, singular approaches to architectural restoration, or tourism-oriented development. There remains a notable lack of in-depth exploration into the historic processes, spatial configuration mechanisms, and strategies through which temple-based “cultural markers” can sustain value across different urban scales. This gap is particularly evident in the scarcity of empirical studies situated within specific geomantic landscapes.

As the sole province-level municipality and national central city in Southwest China, Chongqing boasts over three millennia of urban history. It constitutes a unique geographical region integrating diverse cultural traditions [

6]. Its spatial structure has been profoundly shaped by topography, resulting in a characteristic mountain-water-city nested configuration [

7]. Against this backdrop, this study selects Chongqing’s urban temples as the focus of investigation, for three main reasons.

First, endowed with abundant mountain and water resources, Chongqing emerged as an exemplar of the ancient urban planning philosophy of “conforming to natural laws”, representing an archetype of China’s traditional mountain-water-city integrated systems [

8]. This spatially constrained urban form provides a critical paradigm for analysing long-term human-environment sustainability.

Second, functioning as a religious-cultural confluence hub, particularly during the Qing dynasty, Chongqing integrated Buddhism, Taoism, folk beliefs, and religions in various regions through migration [

9]. This pluralistic practice fostered typological diversity and ecological adaptability in temple architecture [

10], with artistic expressions and environmental integration patterns serving as tangible manifestations of premodern ecological aesthetics.

Third, the intrinsic spatial relationship between urban expansion and temple development is particularly significant. Throughout four major phases of walled-city construction culminating in the Qing dynasty (1644–1912 CE) [

6,

11], its spatial configuration achieved maturity under the guidance of

Xiangtian Fadi (

象天法地, cosmic-terrestrial mimesis) planning principles [

12] and the

Jiugong Bagua (

九宫八卦, Nine Palaces-Eight Trigrams) geomantic schema[

8,

13]. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Chongqing’s culture, economy and society had reached their peak, and numerous temples were built both inside and outside the city walls. Anchored within layers of historical landscapes, temples functioned as cultural markers that actively shaped urban morphology by providing communal spaces, reinforcing social cohesion, and generating economic vitality.

This study focuses on the historic city of Chongqing during the Qing dynasty, examining the intrinsic relationships between temples and their holistic environments across multiple spatial scales: regional (macro), city (meso), and place (micro). By analysing the multi-scalar spatial characteristics of temples across historical periods, it elucidates how traditional religious spaces contribute to urban historic layering through environmental adaptation and cultural integration. These findings provide valuable empirical evidence for examining how cultural heritage can achieve creative transformation within contemporary sustainability frameworks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

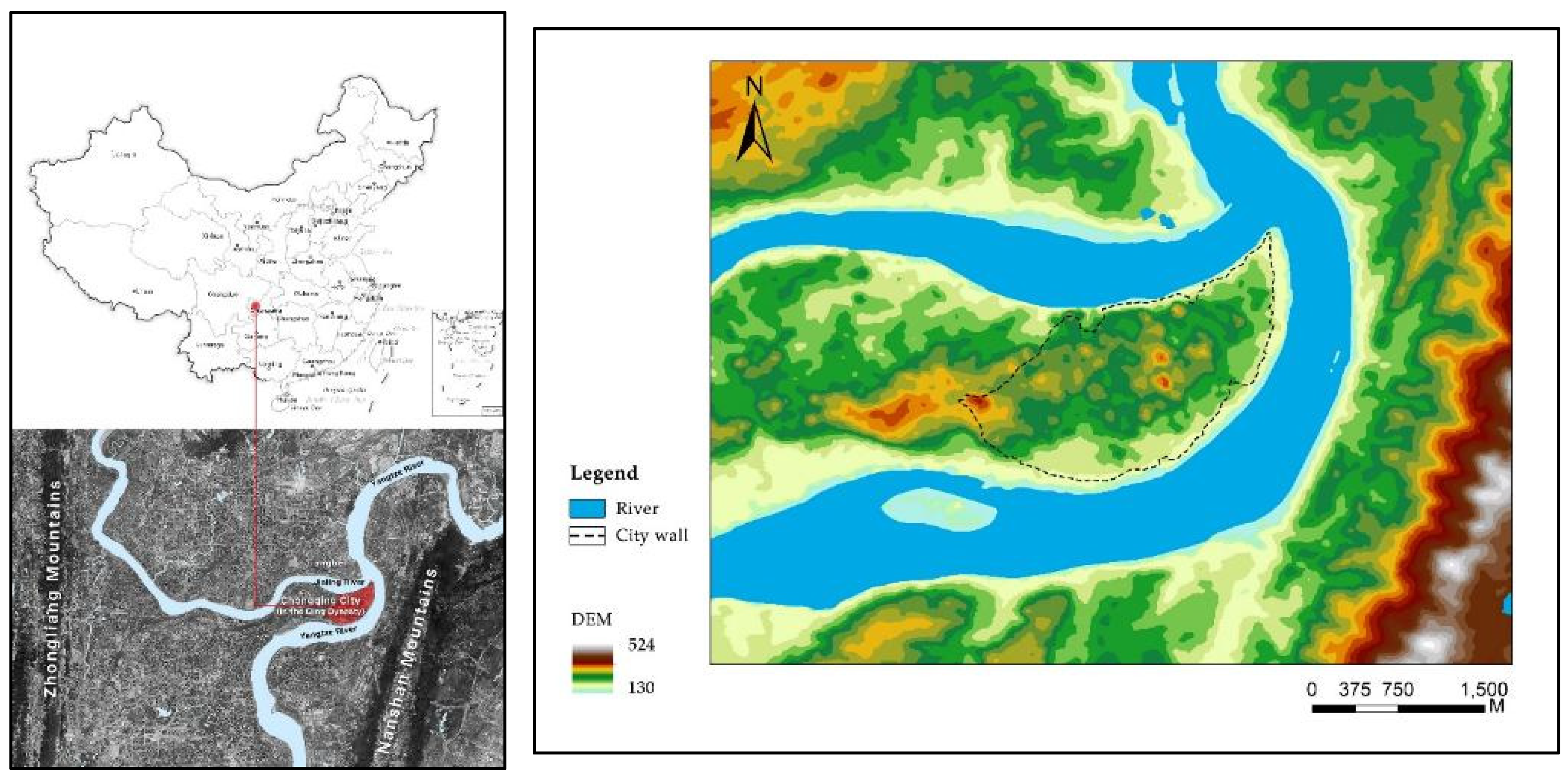

This study focuses on the 2.4 km

2 morphological boundaries of Chongqing’s walled city in the Qing Dynasty. At the same time, it extends its analytical scope to include the surrounding topography, specifically the mountain ranges and river networks visible from within the walled urban core (

Figure 1). Specifically, the study area extends from Fotuguan Pass in the west, the Jialing River in the north, the Nanshan Mountains in the east, to the Yangtze River in the south.

The holistic landscape configuration of this area has fundamentally influenced Chongqing’s urban development and historical-cultural evolution across successive dynasties, forming a distinctive mountain-water-city nested pattern. Moreover, the continuous spatial distribution of temples within this zone across historical periods provides a comprehensive perspective for tracing their developmental trajectories and evolutionary patterns within the ancient urban fabric.

2.2. Data Sources

Chinese local gazetteers (

fangzhi) and historical maps have accumulated vast information regarding their rulers and citizens, religion, ways of life, events, topography, government, and more [

14]. These constitute critical references for this study. Historical temple data is drawn primarily from the Complete Map of Chongqing Prefecture (

Chongqing Fuzhi Quantu), and supplemented by local chronicles such as the Ba County Gazetteer (Baxian Zhi). Compiled by Zhang Yunxuan between 1886 and 1890, the Complete Map (dimensions: 78 cm × 145 cm; scale≈1:4,000) is preserved in Yale University Library. It meticulously depicts Chongqing’s urban landscape and riverfront areas before its opening as a treaty port (pre-1891) and is renowned for both its detail and artistic refinement. It remains one of the most precise surviving cartographic records of ancient Chongqing [

15].

The map employs landscape painting techniques for depicting peripheral mountains and semi-perspective techniques for rendering urban structures, enabling precise identification of: City gates, Dockyards, Temples, Government offices, and Confucian academies. It also annotates road networks and toponyms with remarkable precision, providing verifiable historical evidence for analysing Qing-dynasty Chongqing’s urban and religious spaces.

Road infrastructure data is supplemented by the New Survey Map of Chongqing City (Republican Era) and the Topographic Map of Chongqing City (Surveyed by Chongqing Public Works Bureau, 1929). Natural environment data (elevation, terrain, hydrography) is derived from SRTM DEM 12.5m (NASA;

https://www.gscloud.cn/) and China Geological Cloud Platform (CGS;

https://geocloud.cgs.gov.cn/).

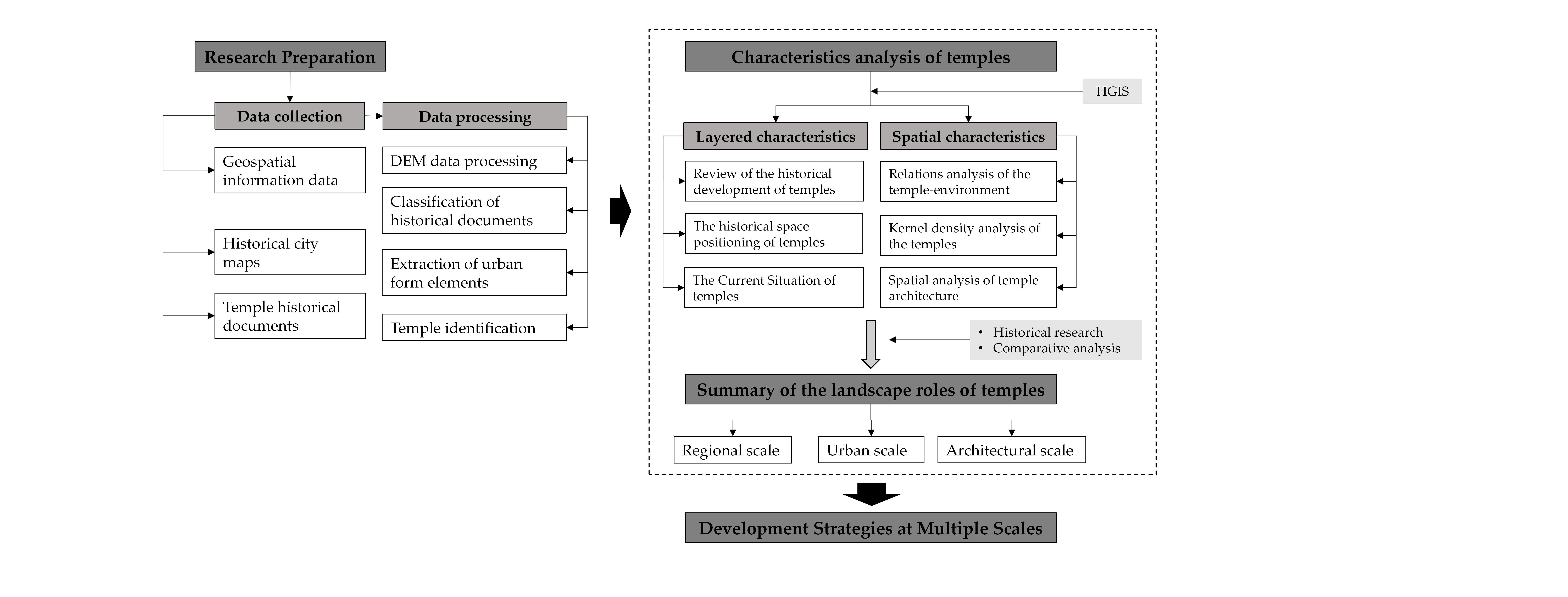

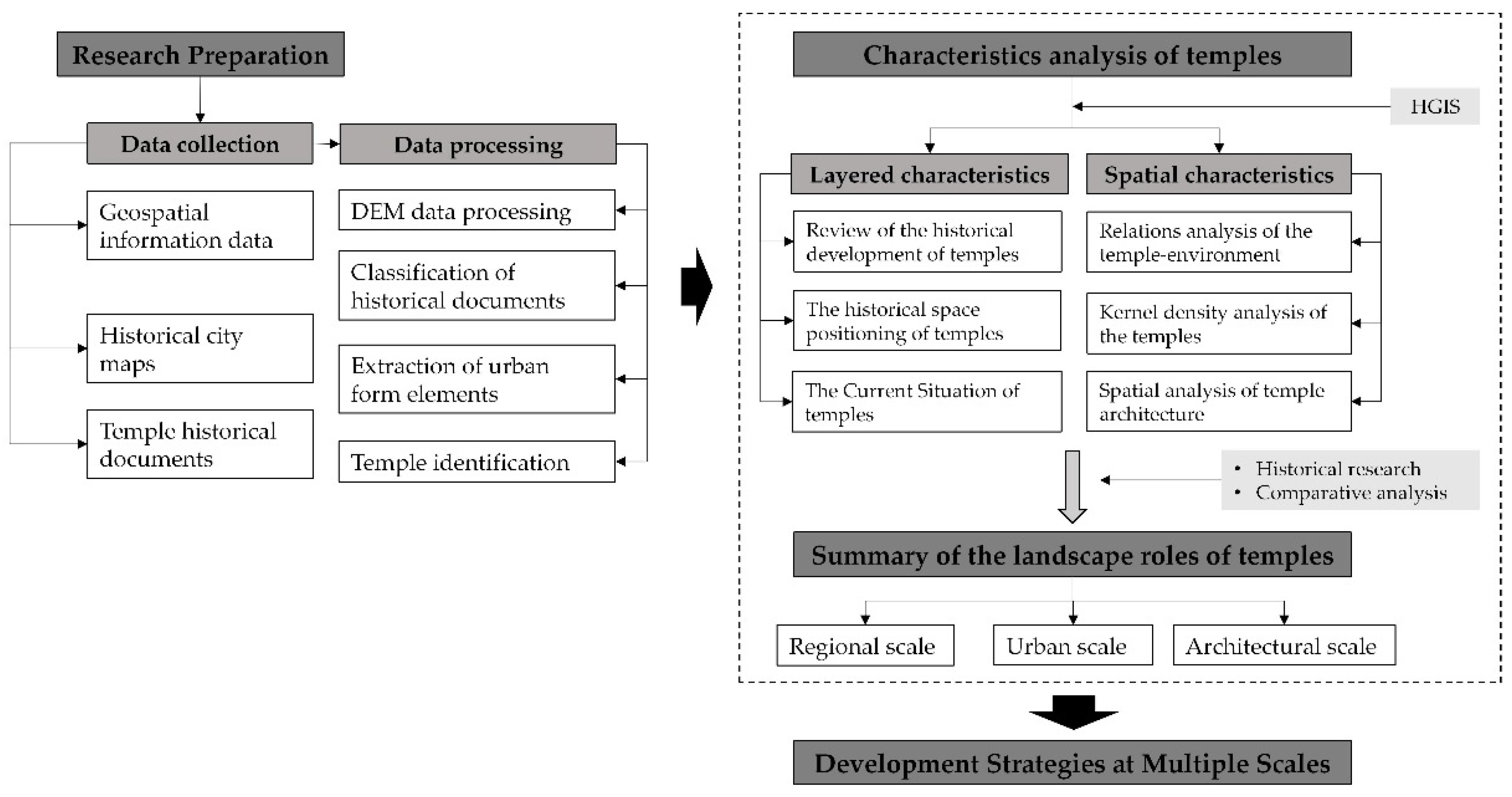

2.3. Research Methods

Historical Geographic Information Systems (HGIS) spatiotemporally integrate historical data with geographic information technologies and, through map visualisation, multi-layer overlays, and quantitative spatial analysis, can reveal patterns of landscape evolution and spatial relationships, making them a powerful research tool [

16]. This study employs an integrated approach combining Historical Geographic Information Systems (HGIS) and empirical research to systematically analyse the spatial distribution patterns and landscape functions of urban temples in Chongqing. The results aim to provide critical references for advancing contemporary urban cultural sustainability (

Figure 2).

2.3.1. Data Processing

We collected extensive local gazetteers and historical maps related to Chongqing’s ancient city and temples, focusing on building spatial data, urban and transportation morphology, and temple records. From these sources, we extracted spatial features, vectorised them, and incorporated multi-source data to establish baseline geographic information. Relying on Republican-period surveyed topographic maps, we digitally reconstructed Chongqing’s urban form and transport network, then matched and plotted temple locations on scaled topographic maps to rebuild their historical distribution. Using the positions of the temples in the

Chongqing Fuzhi Quantu and cross-referencing the

Siguan Zhi (Records of Temples) in the

Baxian Zhi (Chongqing Gazetteer) against the surveyed maps, we identified 79 verifiable temples to form the spatial dataset for analysis (

Figure 3).

2.3.2. Multiscale Spatial Analysis

Historical maps were georeferenced in ArcGIS 10.8, with the precise geospatial locations of all 79 temples plotted on scaled topographic basemaps. Kernel density analysis (200-meter radius) was applied to these temple points, in combination with quantitative statistical methods, to identify spatial distribution patterns.

This study conducts a multidimensional analysis of Chongqing’s historical temples at three scales—macro (regional mountain–river environment), meso (urban space), and micro (architectural place)—focusing on temples’ roles in landscape connectivity, the formation of urban imagery, social functions, and cultural consciousness, as well as their contributions to the sustainable development of the historic city. Finally, based on field surveys and an assessment of the conservation and reuse of surviving temple heritage, and drawing on historical experience and practice, the study proposes references and guidance for contemporary strategies of temple heritage protection and sustainable development.

3. Results

3.1. Layered Characteristics of the Temples

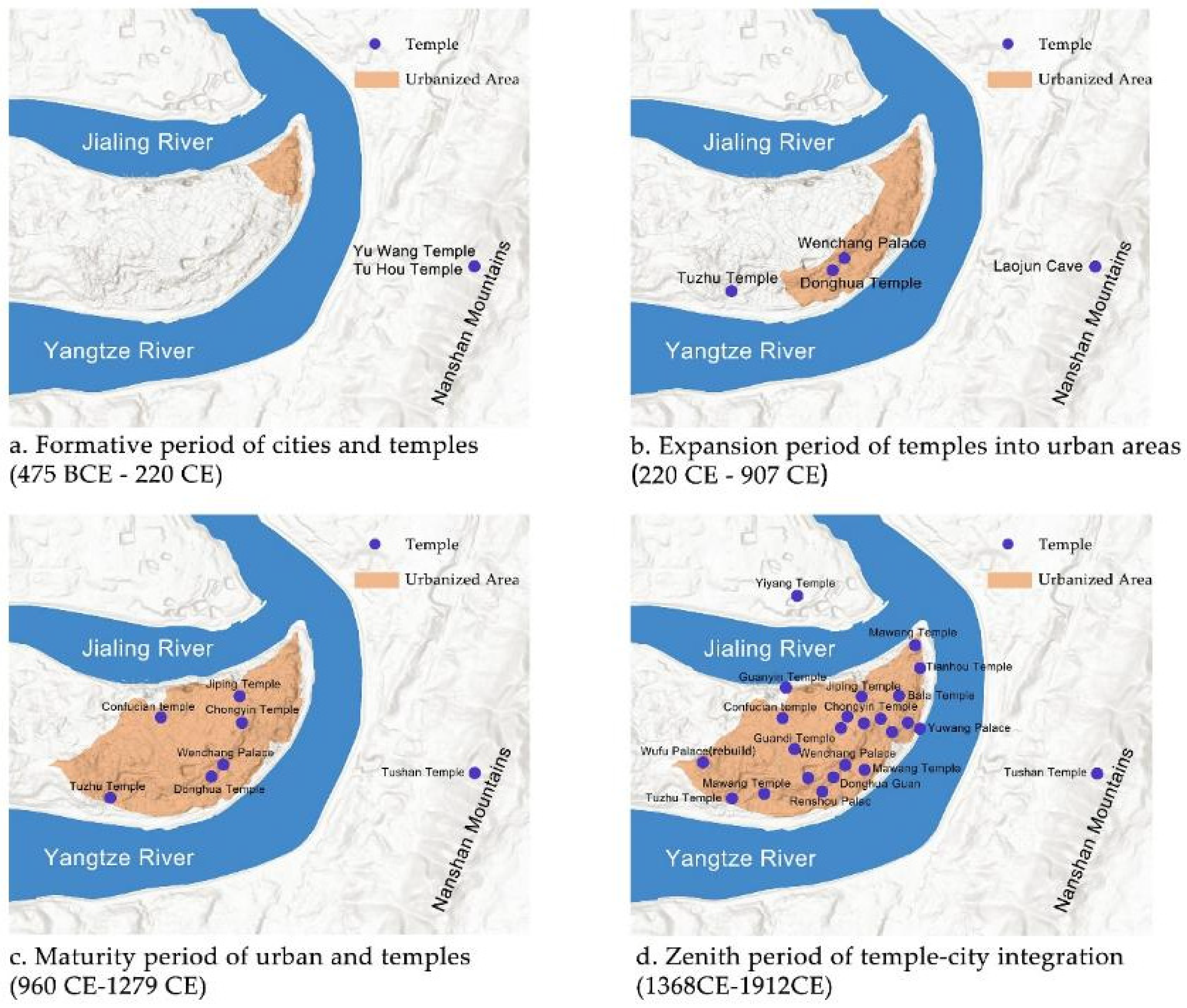

3.1.1. Formative Period of Cities and Temples (475 BCE–220 CE)

During the Warring States period, city-building had already begun at the confluence of the Jialing and Yangtze rivers. By the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty, Buddhism had only recently been introduced to China, and Daoism remained in its formative stage; records of temple constructions are exceptionally scarce. One temple recorded in historical sources is the “

Tianshi Dao(天师道)” Daoist site built on Tushan Mountain in 142 CE[

17], which later developed into

Yu Wang Temple and the

Tu Hou Temple, situated across the river from Chongqing city[

18].

3.1.2. Expansion Period of Temples into Urban Areas (220 CE–907 CE)

By 226 CE, General Li Yan of the Shu Han state constructed a new large fortress on the eastern side of today’s Yuzhong Peninsula, roughly corresponding to the area from present-day

Chaotianmen(朝天门) to

Nanjimen(南纪门) and south of the ridge. This marked the initial urban formation of Chongqing[

11]. During the Sui–Tang period, economic and cultural prosperity spurred temple construction in Chongqing. The well-known Daoist site Laojun Cave on Nanshan was established in 741, emerging from the earlier Yuwang Temple and the Tuhou Temple. Temples from this period with clear documentary evidence include Donghua Temple and Wenchang Temple within the city, and the Earth Deity Temple (Tuzhu Temple), which then stood outside the city wall.

3.1.3. Maturity Period of Urban and Temples (960 CE-1279 CE)

By the Song dynasty, Chongqing’s political and economic status had risen significantly. In the late Southern Song period (1238 CE), Prefect Peng Daya carried out an expansion of the city. The boundary was extended from the old ridgeline at Daliangzi to the present-day Linjiang Men–Tongyuan Men axis in Yuzhong District, incorporating the broad, gentle lands north of the ridge and the former western high point into the urban area. The overall area roughly doubled, establishing the spatial extent that Chongqing would retain through the Ming and Qing periods. With the expansion of the city limits, temples began to appear in the central urban area; historical records mention Zhiping Temple, Chongyin Temple, Chuanzhu Temple, and the Guandi Temple.

3.1.4. Zenith Period of Temple-City Integration (1368CE-1912CE)

During the Ming-Qing period, ruling elites actively promoted state-sanctioned religious institutions to cultivate social order, leading to the construction of officially commissioned temples[

19] such as Confucian Temples

(文庙), Wenchang Palaces

(文昌宫), Dongyue Temples

(东岳庙), and Guandi Temples

(关帝庙). At the same time, popular worship flourished as Buddhism and Daoism merged with folk beliefs, strengthening both their social influence and institutional presence. Meanwhile, in the late Ming and early Qing (17th–18th centuries), migrants poured into Chongqing and Sichuan in the large-scale repopulation historically termed “

Huguang Fills Sichuan” (

Huguang tian Sichuan)[

6]. This wave of migration spurred the extensive construction of guild halls, with each group bringing its patron deities. Halls such as Yuwang Palace, Tianhou Palace, and Nanhua Palace gradually developed into religious sites with ritual functions[

20]. Temple construction thus reached its zenith period, epitomised by Magistrate Wang Erjian’s (Qing dynasty) record in the Ba County Gazetteer[

21]:

Figure 4.

The historical layering development of temples.

Figure 4.

The historical layering development of temples.

“There is no area in the city without a mountain, and no mountain without a temple. From the urban centre to the rural villages, there are too many temples to enumerate (Wang, 1760).”

3.2. Temple Distribution Characteristics in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912)

There were a large number of temples of diverse types in Chongqing during the Qing dynasty, including Buddhist and Daoist temples, official temples, folk temples, and guild-hall temples. Over centuries of development, these temples became key elements in the evolution of the city’s historical landscape. Chongqing, where the Yangtze and Jialing rivers meet and flow through the town and which is ringed by ranges such as Bashan Mountain, Nanshan Mountain, and Tushan Mountain, was a typical Mountain-river city. This makes it an indispensable case for analysing the multi-scale cultural landscape characteristics of historical cities shaped by complex terrain conditions.

3.2.1. Temple–Environment Relationships at the Regional Scale

Statistical analysis reveals distinct elevational and spatial patterns among the 79 temples. Of these, 44.30% were located at elevations between 210 and 250 meters, 26.58% between 250 meters and 280 meters, and 11.39% on the Bashan and

Jinbi ridgelines above 280 m—the topographic high points within Chongqing city. Meanwhile, 17.72% were located below 210 meters, along the rivers outside the city walls (

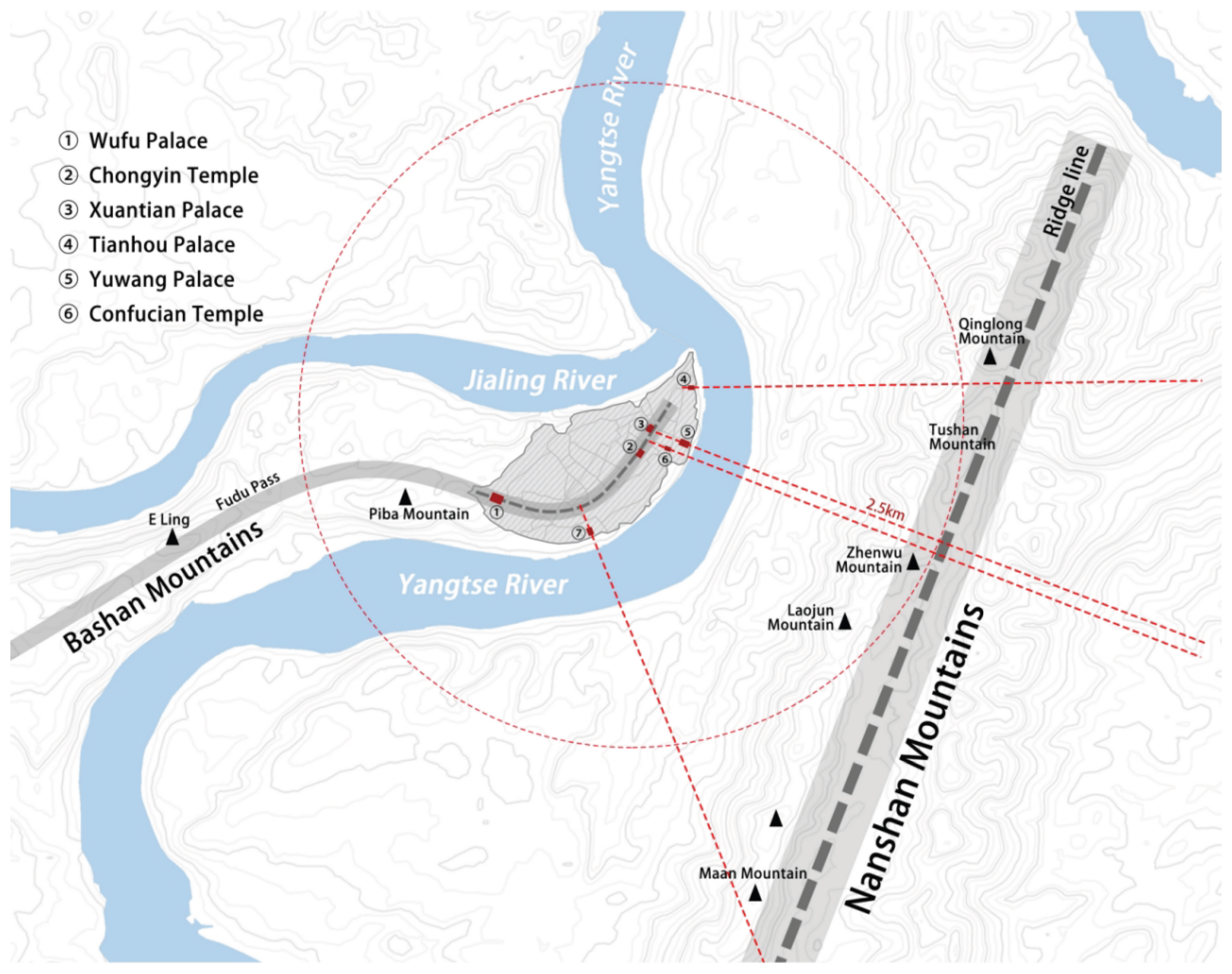

Table 1). Collectively, nearly one-third of all temples were positioned in direct physiographic connections to either the mountaintops or the riverbanks.

From the perspective of the regional landscape, a geospatial overlay of historical maps onto contemporary topography reveals that three topographic high points are each occupied by a temple: Tushan Temple on Nanshan Mountain, Wufu Palace atop the Bashan ridge within Chongqing’s urban extent, and Yiyang Temple at the highest point of the

Jiangbei Ting(江北厅) north of the Jialing River. Together, these three religious sites formed a triangular configuration that effectively encompassed much of historic Chongqing city (

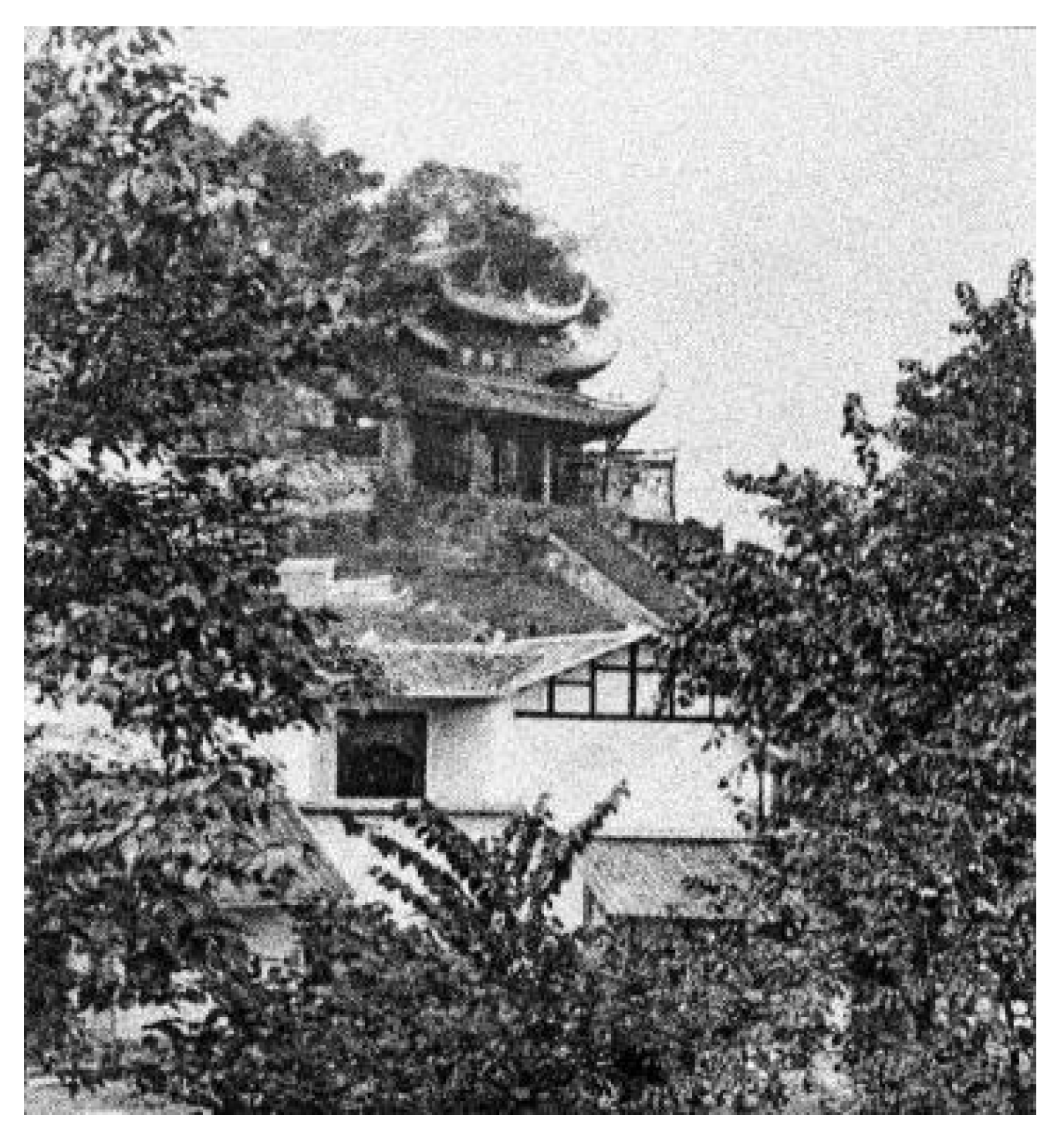

Figure 5). A late Qing–era photograph of the town corroborates this pattern, showing the Daba Mountain ridge running west–east through Chongqing, with Wufu Palace, Chongyin Temple, and Xuantian Palace aligned along this spine and functioning as prominent orientational references. Meanwhile, riverside temples such as Ziyun Palace, Shuifu Temple, and Yuantong Temple functioned as highly legible markers that demarcated the city’s edge along the river (

Figure 6).

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution of Temples at the Urban Scale

Kernel density analysis revealed multiple clustering hotspots in Qing-dynasty Chongqing’s temple distribution. The Daliangzi ridge functions as the city’s spine and the primary boundary between the”

Shangbancheng (

上半城, Upper City, north of the ridge) “and “

Xiabancheng (

下半城, Lower City, south of the ridge) “ (

Figure 7). The largest hotspot polygon, exhibiting both the highest kernel density value and the greatest spatial extent, is located in the lower half along the Yangtze riverfront in the

Dongshuimen–Cuiweimen–Chaotianmen sector, indicating a high number and dense clustering of temples there. From

Daliangzi toward

Hongyamen, a series of small contiguous hotspots indicates a relatively dense temple distribution along the ridge, and additional hotspot clusters occur adjacent to city gates and wharves, further evidencing temple aggregation in these areas (

Figure 8).

Statistical results indicate a significant correlation between temple spatial distribution and core elements of the urban transportation system. Analysis shows that approximately 39.24% of temples were located along the city’s main streets, while about one-quarter (25.32%) were situated adjacent to city gates and docks (

Table 2). These nodal points, as gateways during the heyday of waterborne transport, functioned as intermodal interfaces between land and river networks and as distribution hubs for both people and goods, underscoring the close relationship between temple siting and prevailing transportation corridors.

Based on religious affiliations, Qing-era temples in Chongqing can be classified into five types: Buddhist temples, Daoist temples, official temples, folk temples, and immigrant guilds that also served ritual functions (often labelled “

Gong” or “

Miao”). Quantitative analysis indicates that Buddhist temples (27.85%) and folk temples (25.32%) comprised the most significant shares, followed by Daoist temples (21.52%) (

Table 3). Clusters of Buddhist temples are primarily distributed in the northern “

Shangbancheng” of the city and along the Yangtze riverfront in the Nanjimen–Dongshuimen corridor. Daoist establishments formed kernel density hotspots in the “

Xiabancheng” around the

Jinzimen(金紫门)–Chuqimen(储奇门) area. Official temples were concentrated in the lower half of the city and exhibited a relatively even distribution, while folk temples showed higher kernel density peaks and a broader spatial extent. Immigrant guild temples are the least numerous (10.13%) but displayed a strong clustering at commercial nodes such as

Dongshuimen and

Chaotianmen, where they maintained efficient linkages with Yangtze River transport networks (

Figure 9).

3.2.3. Temple Spatial Layout at the Architectural Scale

Although the temples depicted in

Chongqing Fuzhi Quantu differ in affiliation and the constituencies they served, their architectural layouts, spatial functions, and formal typologies share notable commonalities. First, regarding orientation, statistical analysis of temple alignments (

Table 4) indicates that south--facing temples were the most numerous (29.11%), followed by southeast-facing and north-facing temples (17.72%), and east--facing temples represent 16.46% (

Figure 10). These orientation patterns correspond to the topographic characteristics of the Chongqing peninsula and broadly align with the traditional Chinese construction ritual that privileges southern orientation.

The floor plans of temple buildings largely adhere to the traditional spatial typology of Han--Chinese architecture, with symmetrical arrangements along a central axis and multiple structures enclosing one or more courtyards. On the Complete Map of Chongqing Prefecture, temples are depicted with yellow or dark-grey roofs and distinctive courtyard volumes that set them apart from surrounding streets and residential areas (

Figure 11). Quantitative analysis indicates that the vast majority of temples (79.75%) include courtyard spaces (

Table 5). In comparison, 16.46% contained two or more courtyards, including well--known temples such as Chongyin Temple, Zhiping Temple, and Wufu Gong Temple.

In terms of spatial function, in addition to the palace buildings necessary for religious activities, many temples also incorporated public activity spaces into their layout, thereby better providing residents with places for socialising, sightseeing, entertainment, and art appreciation. A case in point is Chongyin Temple, the largest Buddhist temple in the city, which features the Jingxiang Pavilion and Jinbi Terrace within its affiliated garden. These structures serve as significant viewpoints, offering vistas that are particularly noteworthy.

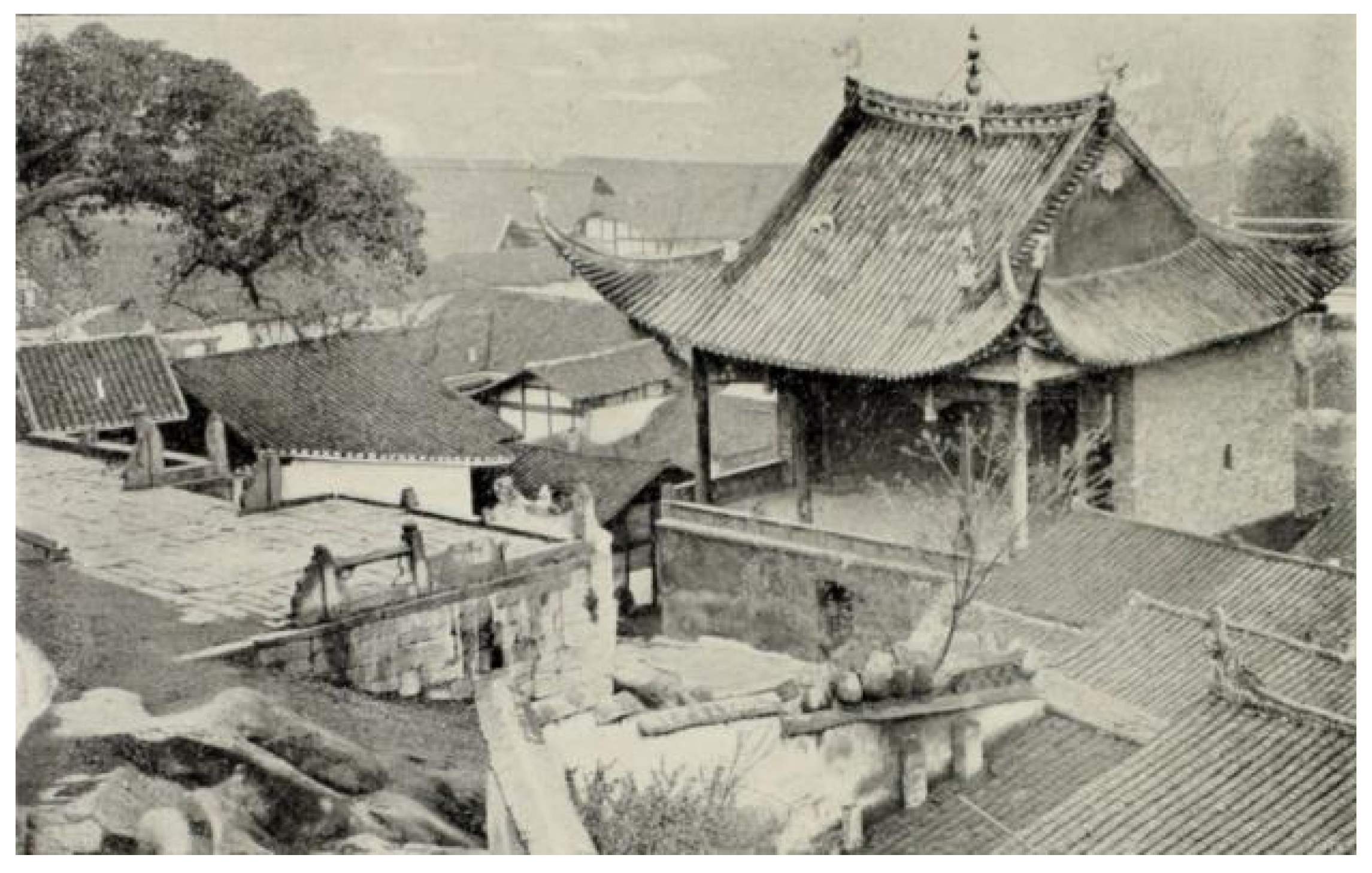

Wufu Gong, situated on the city’s highest point, exploited its elevation with high platforms and towers, creating commanding downward vistas and functioning both as a visual landmark in the urban skyline and as an essential orientational focus (

Figure 12). Theatre stages in temple courtyards were a common architectural form in Chongqing, with such stages often being set up for performances. (

Figure 13).

3.3. The Current Situation of the Temples

As a result of the impact of modern thought, wartime destruction, and rapid urbanisation, the number of temples within Chongqing’s historic Yuzhong Peninsula (the bounds of Qing--era Chongqing) has declined sharply. Surviving sites are limited to Sanjiao Tang (now Nengren Temple), Luohan Temple, Donghua Guan Temple (only its sutra--repository tower remains), and Yuwang Gong Temple located within the Huguang Guild complex (

Table 6). Yuwang Gong Temple has received integrated protection as part of a designated Chongqing historical--cultural street, together with Guangdong Guild, Qi’an Guild, the

Dongshuimen section of the city wall, the

Xiejia Yuanzi (

谢家院子), and other historic structures. The cliff-carved Buddha images at Luohan Temple and the sutra-repository at Donghua Guan Temple have been designated municipal-level cultural relics. At the same time, Nengren Temple currently lacks any official heritage protection status.

Compared with their former role as prominent marks of the urban templescape, the extant temples are now deeply embedded within a high--density modern metropolis. Their conservation and sustainable development face multiple challenges, including fragile physical fabric, fragmented survivals, isolated protection measures, and discontinuities in the historical landscape narrative.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Landscape Roles of Temples at Multiple Scales

4.1.1. Guiding Urban Landscape Order

Temples were typically constructed at key nodes within the mountain-and-river landscape configurations, where designers enhanced visual connectivity between urban areas and natural settings through deliberate landscape control[

22]. The classical Chinese garden treatise

Yuanye (

园冶, Treatise on Garden Design) conceptualises this approach as “ minor architectural interventions suffice to frame grand vistas. “ (

略成小筑,足征大观), epitomising the quintessential Chinese landscape philosophy [

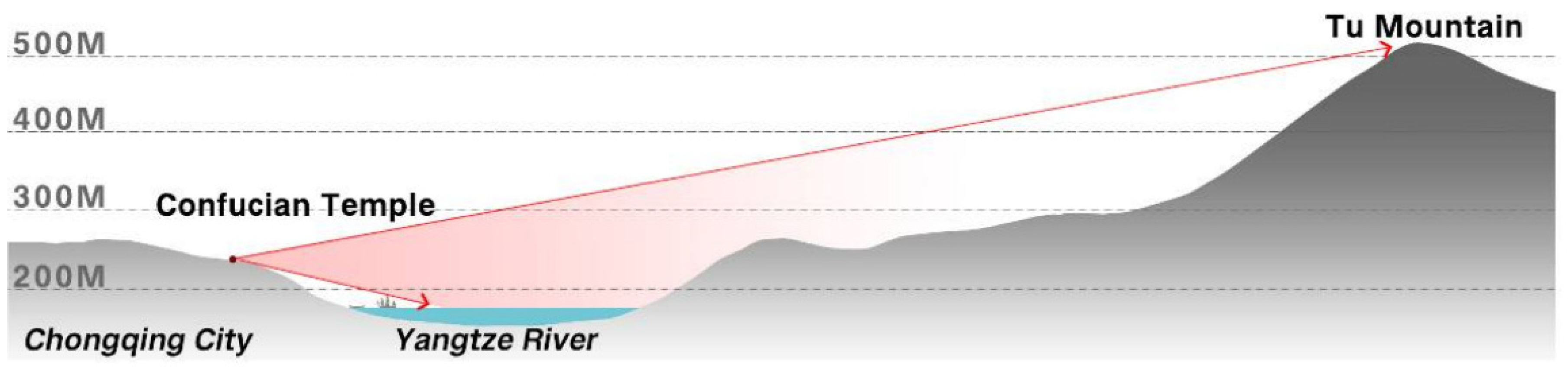

23]. The findings of this study corroborate this concept. For example, during the reign of Emperor Qianlong, the Ba County Annals (1760) records noted:

“The Confucian Temple is located on the banks of the Yangtze River, where buildings and vehicles once converged, blocking the temple’s connection to the Yangtze River. In the early years under the reign of Emperor Qianlong, the village official Long Weilin and two tribute students donated a total of around 300 taels of silver to purchase the land in front of the Confucian Temple to ensure that no building was constructed on this site, thus maintaining the scenic link between the Confucian Temple and the Yangtze River” (

Figure 14).

Similarly, temples such as Wufu Palace, Chongyin Temple, Xuantian Palace, and Yuwang Temple were constructed along the Bashan range, historically regarded as Chongqing’s “dragon vein”(

龙脉). They linked Nanshan Mountain, the Yangtze River, and the urban core through visual landscape corridors. They thus played a critical role in sustaining the structural coherence of the city’s mountain-river system. These historical materials suggest that in ancient Chongqing City, where natural landscape resources of mountains and rivers provided the city’s environmental characteristics, temple landscapes played an active role in visually connecting the town with its natural surroundings and in maintaining an ecological order between humans and nature[

24]. Regrettably (

Figure 15), the integrative role of temples in fostering interregional landscape connectivity has often been overlooked in contemporary urban practice.

4.1.2. Shaping Urban Landmarks

This study reveals that temples functioned analogously to landmarks in Kevin Lynch’s theoretical framework, playing a pivotal role in shaping the legibility of the city[

25]. As documented by Archibald Little in

Through the Yang-tse Gorges (1888): “Only temples and yamen buildings stood out above typical dwellings, with temples distinguished by their glazed green and golden tiles.[

26]” This highlights the high visual distinctiveness of religious architecture. Similar to other premodern Chinese cities such as Xian[

27], Hangzhou[

28], and Chengdu[

29], temples in Qing-period Chongqing served as urban landmarks through their distinctive architectural forms and strategic siting, thereby enhancing cognitive perception of the urban spatial structure.

In contrast to the static morphological identification of landmarks, traditional Chinese city-building practices emphasised dynamic cultural narratives and the creation of the symbolic meaning of mountain-river forms[

30]. As articulated by Cai Mutang, a renowned Song-dynasty geomancer: “Mountains and rivers form are nature’s endowment, while the shaping of landscape is carried out by humans[

31]”. This principle advocated targeted interventions in topographically deficient environments, often through the placement of symbolic structures such as temples. Riverside temples dedicated to water deities, including Zhenjiang Temple, Wangye Temple, and Shuifu Temple. These temples functioned as highly legible vertical landmarks through their imposing walls and sweeping upturned eaves, while also forming sequential landscape nodes along river corridors. Critically, these temples embodied deep cultural meanings related to flood control and protection of navigation, establishing a ritually mediated adaptive system for human-water relations[

32]. Consequently, temples in traditional Chinese urban spaces served not only as physical spatial marks but also as cultural signifiers transmitting ecological adaptation wisdom and societal collective memory, performing simultaneously spatial identification and spiritual--cultural representation.

4.1.3. Anchoring Collective Memories

Studies indicate that in most Chinese cities, temples serve as anchoring points in the accretion of historical urban landscapes, gradually evolving from ritual sites into centres of civic belief and thereby sustaining historical continuity[

33]. Historically, temples served as critical public arenas for temple fairs, festivals, and folk activities, supporting communal values and collective memory as essential components of urban public space[

34].

However, compared with other premodern Chinese cities, Chongqing exhibits a multidimensional particularity in which temples function as carriers of local collective memory through dynamic reconfiguration of their roles over time[

9]. As a migrant “cultural melting pot,” immigrant groups preserved homeland memories through the worship of tutelary deities and, grounded in shared spiritual beliefs and survival interests, established diverse temple venues, including guild--type institutions such as Yuwang Palace, Wanshou Palace, and Nanhua Palace. Thus, Chongqing’s temple networks (e.g., “Nine Palaces and Eighteen Temples”

九宫十八庙) transcended mere spatial manifestations of religion[

35]; they operated as social integrators that unified diverse lineages and social strata through shared spiritual values, reinforced by religious, occupational, and immigrant organisational ties.

4.2. From Sacred Sites to Urban Anchors: Revelations and Strategies

This study reveals how temples have evolved from sacred sites into urban anchors, vital to sustaining historical continuity. Their multiscale landscape characteristics offer critical insights for enhancing cultural sustainability in modern high--density urban areas. We propose a comprehensive, integrated strategy for the holistic conservation and development of temple heritage across three dimensions: regional, urban, and site-specific.

4.2.1. At the Regional Scale

Based on the linkage between temple histories and regional landscape, it is necessary to reconceptualise ancient Chinese mountain--river cities by identifying spatially strategic nodes that are critical to the layering and accretion of historical urban landscape. Following the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) framework, temples should be situated and managed within a unified natural–cultural system, emphasising the symbiotic relationship between temple heritage and mountain--river landforms. To address the problem of fragmented conservation, a three--dimensional restoration strategy—integrity, layer, and connectivity[

36]—is proposed[

37,

38]. In historic mountain--river cities, the creation of cultural heritage corridors that integrate green ecological networks with temple--based cultural tourism systems is advocated as a means of sustaining the historical continuity of temple landscapes.

4.2.2. At the Urban Scale

Temple heritage should be integrated into the contemporary urban fabric to maintain its cultural continuity. In many historic towns in Chongqing, Sichuan, and beyond, a street–temple integration model historically created spatial networks that linked diverse community groups. Contemporary empirical studies further indicate that multiple temple sites can alleviate land constraints through shared space, offering a model of spatial intensification for high--density cities[

1]. For example, temples can serve as community cultural centres, attracting younger generations through festival programming[

39]. Establishing community participation mechanisms—such as resident oral--history collection, traditional craft workshops, and a range of cultural activities—can enhance recognition of temple value among diverse communities and encourage active engagement[

40], thereby avoiding museumification while reinforcing cultural identity. This approach sustains temple vitality within the city and supports its long-term sustainable development.

4.2.3. At the Architectural Scale

Holistic conservation of temple heritage should be strengthened, with respect for religious history and with caution applied to the restoration of later temple structures and the renewal of surrounding environments. Digital technologies can inject new vitality into protection and sustainable development: Historical GIS (HGIS) can be used to reconstruct the historical spatial sequences of temples[

41], while digital mapping can integrate temple cultural resources and support the design of themed tourism routes[

42,

43]. Temples should shift from static display to living transmission, enhancing the experiential design of temple sites. Attention must also be given to the safeguarding and transmission of intangible cultural heritage, particularly through its adaptive transformation in contemporary society, to improve public understanding of temple heritage and its cultural values.

4.3. Research Limitations

This study acknowledges three limitations. First, sample selection bias arises from reliance on Qing-dynasty official records (e.g., Complete Map of Chongqing Prefecture), which document only 79 temples while excluding numerous minor vernacular shrines due to systematic archival gaps. Second, data reliability is constrained by both the precision of historical cartographic and modern georeferencing errors: although the semi-perspective rendering in the 1886 map enables identification of city gates, structures, and docks, its abstract spatial representations introduce positional inaccuracies in temple locations. Third, methodological limitations remain: despite the use of kernel density analysis in ArcGIS, documentation gaps and fragmented records hinder the analysis of dynamic spatial evolution, restricting a comprehensive interpretation of temple landscape layering processes.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the role of temples as cultural signifiers in ancient Chongqing as a case study. It analyses spatial data for 79 Qing-dynasty temples primarily through Historical GIS, and by cross-referencing local gazetteers and historical maps, reveals the deep interaction mechanisms between temples and the mountain-water urban pattern. The research yields three core findings. First, at the regional scale, temples strategically occupy key mountain--water nodes; their distribution is significantly correlated with mountain ranges and waterways and exhibits coupled features across three hierarchical levels (macro, meso, micro). Second, temples act as cultural markers that guide urban landscape order, shape urban landmarks, and anchor collective memory, maintaining historical continuity and cultural sustainability through these three roles. Third, to address the fragmentation of temple heritage protection in present high--density cities, we propose sustainable development strategies across three dimensions—regional, urban, and architectural scale: (1) at the regional scale, integrate urban green networks and cultural tourism routes via cultural heritage corridors; (2) at the urban scale, embed temples within the urban fabric and establish community participation mechanisms; and (3) at the architectural scale, strengthen the integration of intangible cultural heritage, promote living transmission through experiential design, and introduce digital technologies to revitalize heritage sites.

Building on a study of Chongqing temple evolution and its multi--scale spatial characteristics, this research not only provides an empirical example for the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach but also points to pathways for heritage activation and sustainable development in contemporary high--density cities. Future work will adopt interdisciplinary methods, combining oral histories, stele inscriptions, archaeological findings, and digital technologies, to reveal broader values and the mechanisms of cultural resilience in temple heritage and to inform policies for urban cultural sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z.; methodology, R.Z. (HGIS construction and spatial analysis) and C.D. (theoretical framework of historic urban landscape); software, W.H.; validation, R.Z. and L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, R.Z. and H.X.; resources, H.X. and R.Z. (archival materials); writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.Z. and L.Z.; visualization, W.H. (maps and figures); supervision, C.D.; project administration, C.D.; funding acquisition, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts Academic Enhancement Project (grant number: 21XSB28) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China Key Program (grant number: 52238003).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the first author, Rongyi Zhou (rozzi@gzarts.edu.cn), upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Skrede, J.; Berg, S.K. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: The Case of Urban Densification. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 2019, 10, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heritage Centre—Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Li, X.M. Chinese Ideal Landscape Model and Temple Garden Environment. Human Geography 2001, pp. 35–39.

- Duan, Y.M. Chinese Temple Culture; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Du, C.L.; Jia, L.Y. Research on Ecological Wisdom: History, Development and Direction. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2019, 35, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. General History of Chongqing; Chongqing Publishing House: Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Du, C.L. Study on the Landscape Architecture of Mountain Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; He, X. The Idea of Mountain-River City Building in Yuzhong Ancient City, Chongqing (1760-1929) from the Perspective of “Using Images as Historical Evidence”. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition) 2022, 44, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, F.Z. Towns and Dwellings in Bashu; Southwest Jiaotong University Press: Chengdu, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Z. A Study on Regional Architectural Culture in Southwest China. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, B.T. The Ancient City of Chongqing; Chongqing Publishing House: Chongqing, China, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.B.; Du, C.L.; Zhao, J. Analysis on the Spatial Form Characteristics of Chongqing City in Ming and Qing Dynasties. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2017, 33, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Z. The Form of Sichuan Cities and the Spatial Pattern of Temple Buildings in the Qing Dynasty. Huazhong Architecture 2005, pp. 157–158, 163.

- Mostern, R. Dividing the Realm to Govern: The Spatial Organization of the Song State (960-1276 CE); Harvard University Asia Center: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.X.; Cao, G.H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Z.J.; Zheng, Y.S.; Yan, Y.; Xiong, M.; Xiao, C.L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.G.; et al. Chongqing Historical Atlas·Volume I Ancient Maps; Chongqing Institute of Surveying and Mapping: Chongqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, A.K. Historical Geographic Information Systems and Social Science History. Social Science History 2016, 40, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chongqing Municipal Commission of Ethnic and Religious Affairs. Chongqing Religion; Chongqing Publishing House: Chongqing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Q. Annotated Illustrations to the Records of the States South of Mount Hua; Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.S. History of Chinese Religion; Qilu Press: Jinan, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y. Historical and Cultural Geography of Southwest China; Southwest China Normal University Press: Chongqing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [Qianlong] Baxian County Records, Volume 2—[Qianlong] Baxian County Records Full Text Original—Shidian Ancient Books. Available online: https://www.shidianguji.com/book/HY4594/chapter/1ksj6jsetn8l0?version=6 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Wang, S.S. Recovering the Tradition of Landscape Making in Chinese Urban Planning. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2018, 34, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C. Yuanye; Annotated by Chen, Z.; 2nd ed.China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 1988.

- Cui, L.P.; Wang, S.S.; Cui, K.; Lai, J.L. Shanze Tongqi: A Planning Concept Integrating Urban and Mountain-River Environments. City Planning Review 2017, 41, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; ISBN 978-0-262-62001-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lillte, A.J. Through the Yang-Tse Gorges: Or, Trade and Travel in Western China; Sampson Low & Co.: London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Study on the Spatial Construction Characteristics of Temple Gardens in Shaanxi. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S. Shan-Shui Myth and History: The Locally Planned Process of Combining the Ancient City and West Lake in Hangzhou, 1896–1927. Planning Perspectives 2016, 31, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, Z.; Xu, N. The Chinese City in Mountain and Water: Shaping the Urban Landscape in Chengdu. Landscape Research 2024, 49, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.Y. Research on the Spatial Characteristics and Design Principles of Temple Gardens in the Three Gorges Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fengshui Classic, Fa Wei Lun (Cai Mutang). Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1762117457671622689&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Li, C.; Du, C.L. The Placeness Interpretation of Vernacular Settlement Landscape: A Case Study of Ancient Towns in Ba-Yu Region. Architectural Journal 2015, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.M. Temple Culture in Southwest China; Yunnan Education Press: Kunming, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Planning, Design, and Religion: America’s Changing Urban Landscape. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 2013, 30, 221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Du, C.L. Placeness Analysis of the “Nine Palaces and Eighteen Temples” Phenomenon in Ba-Yu Region. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2015, 31, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.F. The Anchoring and Stratification of Urban Historical Landscape: Cognition and Conservation of Historical Cities; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Cao, K.; Li, H.P. The Evolution Rule and Stratified Management of Urban Historical Landscape. Urban Development Studies 2018, 25, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A.N. Sustainable Design, Cultural Landscapes and Heritage Parks; the Case of the Mondego River. Sustainable Development 2016, 24, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, G.T.; Wang, Y.; Dean, K.; Lin, R.; Tang, C.; Choo, J.K.K.; Liu, Y.; Kui, W.K.; Dong, W.; Xue, Y.; et al. A Study of United Temple in Singapore—Analysis of Union from the Perspective of Sub-Temple. Religions 2022, 13, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, L.O.L.; Banda, C.V.; Banda, J.T.; Singini, T. Preserving Cultural Heritage: A Community-Centric Approach to Safeguarding the Khulubvi Traditional Temple, Malawi. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Jiao, X.; Sakai, T.; Xu, H. Mapping the Past with Historical Geographic Information Systems: Layered Characteristics of the Historic Urban Landscape of Nanjing, China, since the Ming Dynasty (1368–2024). Herit Sci 2024, 12, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Guo, X.; Huang, H. The Ontological Multiplicity of Digital Heritage Models: A Case Study of Yunyan Temple, Sichuan Province, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragohain, D.; Buragohain, D.; Meng, Y.; Deng, C.; Chaudhary, S. A Metaverse-Based Digital Preservation of Temple Architecture and Heritage. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 15484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Location and geographical features of Chongqing City in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912).

Figure 1.

Location and geographical features of Chongqing City in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912).

Figure 2.

Methodological research approach.

Figure 2.

Methodological research approach.

Figure 3.

Extraction process of historical map data.

Figure 3.

Extraction process of historical map data.

Figure 5.

Spatial relationship of temples at the commanding heights of Chongqing City. Source: Drawn by the author based on the Map of Ba County (1870).

Figure 5.

Spatial relationship of temples at the commanding heights of Chongqing City. Source: Drawn by the author based on the Map of Ba County (1870).

Figure 6.

Temples are located on the ridgeline of Chongqing City. Source: Drawn by the author based on historical photos of Chongqing City (Photographer: Manly, Wilson Edward. Time:1900-1920).

Figure 6.

Temples are located on the ridgeline of Chongqing City. Source: Drawn by the author based on historical photos of Chongqing City (Photographer: Manly, Wilson Edward. Time:1900-1920).

Figure 7.

Structural diagram of Shangbancheng and Xiabancheng.

Figure 7.

Structural diagram of Shangbancheng and Xiabancheng.

Figure 8.

Kernel density distribution map of Chongqing City temples.

Figure 8.

Kernel density distribution map of Chongqing City temples.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of temples with different categories.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of temples with different categories.

Figure 10.

Statistics of temples of different slope directions.

Figure 10.

Statistics of temples of different slope directions.

Figure 11.

Plan the layout of the typical temples.

Figure 11.

Plan the layout of the typical temples.

Figure 12.

Wufu Temple in 1911. (Source: by Hedwig and Fritz Weiss).

Figure 12.

Wufu Temple in 1911. (Source: by Hedwig and Fritz Weiss).

Figure 13.

A temple theatre. (Source: An Australian in China by G.E. Morrison, 1894).

Figure 13.

A temple theatre. (Source: An Australian in China by G.E. Morrison, 1894).

Figure 14.

The view corridor between the Confucian Temple, the Yangtze River, and the Tu Mountain.

Figure 14.

The view corridor between the Confucian Temple, the Yangtze River, and the Tu Mountain.

Figure 15.

The spatial relationship of the temple, the mountain and the river.

Figure 15.

The spatial relationship of the temple, the mountain and the river.

Table 1.

Statistics of temples of different elevations.

Table 1.

Statistics of temples of different elevations.

| Elevation value |

Quantity |

Proportion |

| < 210m |

14 |

17.72% |

| 210-250m |

35 |

44.30% |

| 250-280m |

21 |

26.58% |

| > 280m |

9 |

11.39% |

| Total |

79 |

100.00% |

Table 2.

Statistics of temples in different locations of the city.

Table 2.

Statistics of temples in different locations of the city.

| Location |

Quantity |

Proportion |

| Main Street |

31 |

39.24% |

| Side street |

18 |

22.78% |

| Cundy |

10 |

12.66% |

| The city gates and docks |

20 |

25.32% |

| Total |

79 |

100.00% |

Table 3.

Statistics of temples of different elevations.

Table 3.

Statistics of temples of different elevations.

| Temple types |

Quantity |

Proportion |

| Buddhism |

22 |

27.85% |

| Daoism |

17 |

21.52% |

| Official temple |

12 |

15.19% |

| Folk temple |

20 |

25.32% |

| Immigrant guild |

8 |

10.13% |

| Total |

79 |

100.00% |

Table 4.

Temple statistics of different slopes.

Table 4.

Temple statistics of different slopes.

| Slope |

Quantity |

Proportion |

| < 10% |

15 |

18.99% |

| 10%-25% |

48 |

60.76% |

| 25%-50% |

15 |

18.99% |

| > 50% |

1 |

1.27% |

| Total |

79 |

100.00% |

Table 5.

The current situation of the temples.

Table 5.

The current situation of the temples.

| Plan form |

Quantity |

Proportion |

| Three courtyards |

2 |

2.53% |

| Double courtyards |

5 |

6.33% |

| A single courtyard |

56 |

70.89% |

| No courtyard |

16 |

20.25% |

| Total |

79 |

100.00% |

Table 6.

The current situation of the temples.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).