Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. RNA Aptamers: Synthetic Precision in Targeting and Sensing

3. Epitranscriptomics: Decoding the Chemical Language of RNA Modifications

4. Structural Plasticity and Modification Sensitivity: A Conceptual Bridge

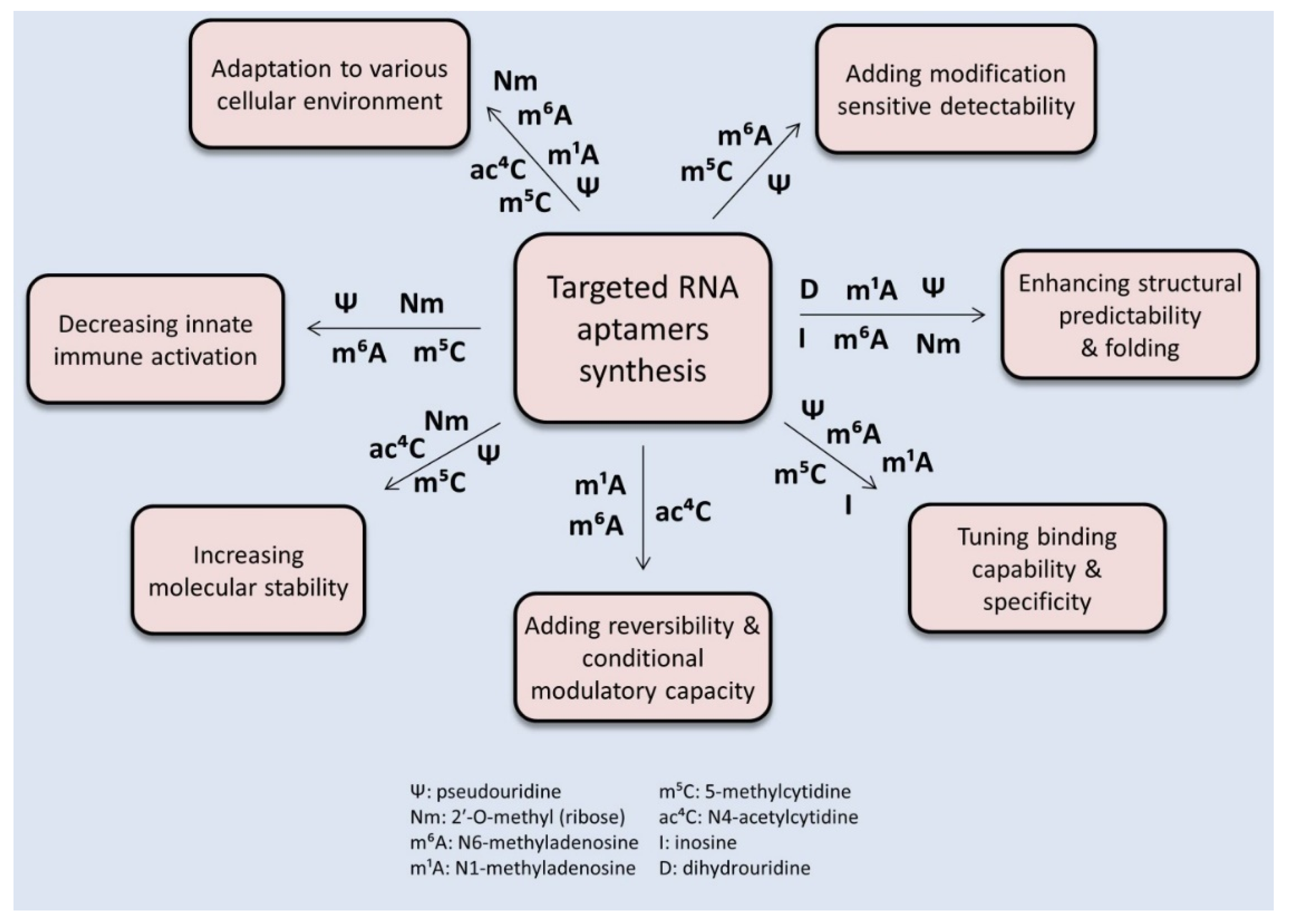

5. RNA Modifications as Modulators or Targets of Aptamer-Based Tools

6. Potential for Synthetic Biology and Theranostics Integration

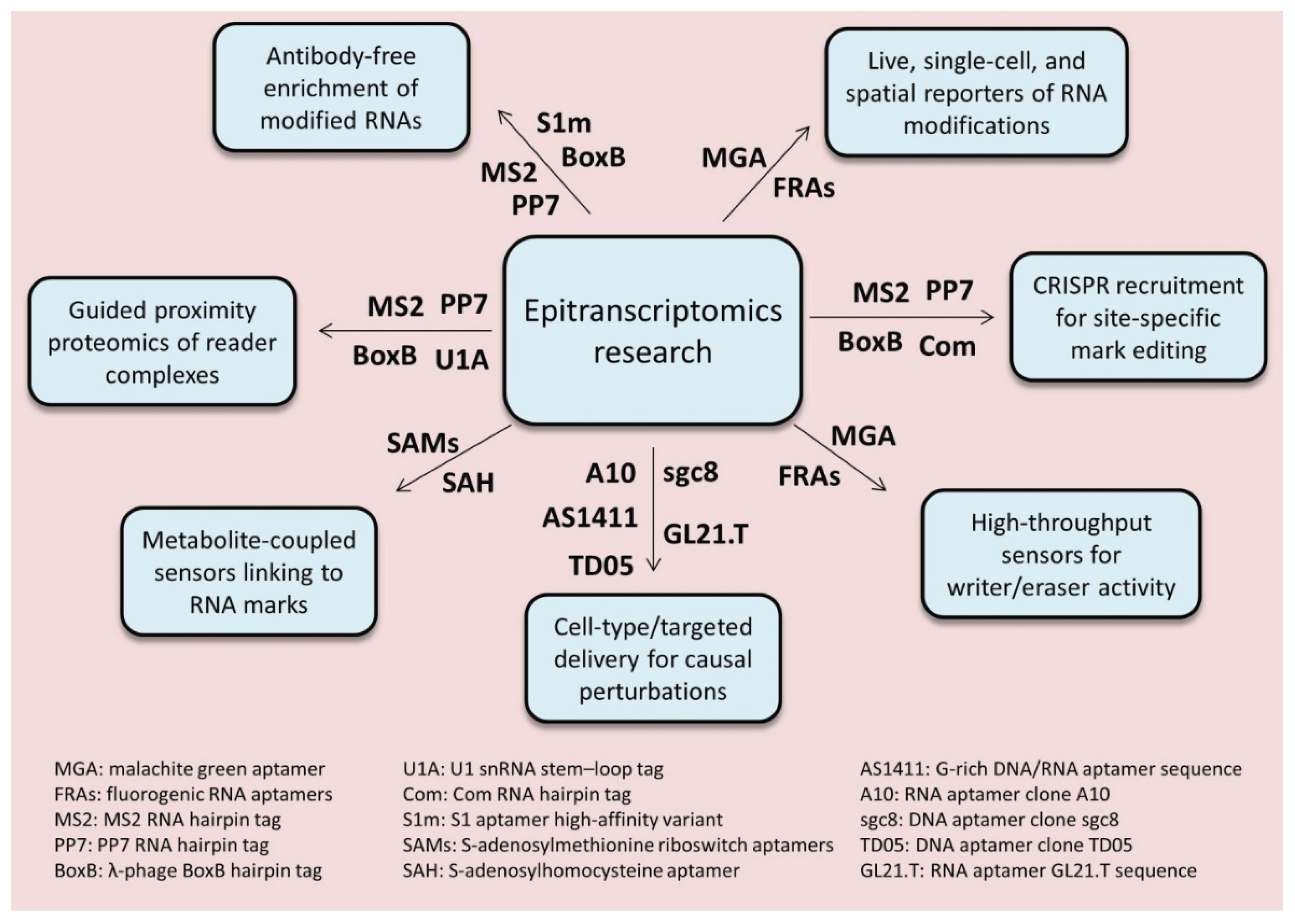

7. Technological Convergence: Detecting, Mapping, and Manipulating Modifications

8. Challenges and Considerations for Future Research

9. Conclusions

| Feature | RNA Aptamers | Epitranscriptomics | Possible Intersection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional dependency | Structure-dependent binding | Structure-dependent regulation | RNA modifications may alter aptamer folding or stability |

| Selection/design methods | SELEX-based in vitro evolution | Genetic, enzymatic, or chemical modification | Modified RNA libraries could be used for aptamer selection |

| Key chemical elements | Unmodified or chemically stabilized nucleotides | m⁶A, Ψ, m⁵C, etc. | Aptamers could be sensitive to or recognize these modifications |

| Role in gene regulation | Target inhibition; molecular recognition | mRNA splicing, stability, translation | Combined tools may control gene expression in a condition-specific manner |

| Therapeutic use | Targeted drug delivery; inhibition of proteins | Cancer, neurological diseases, immune regulation | Aptamer-based delivery of epitranscriptome-modifying agents |

| Response to cellular environment | May be degraded or misfolded | Responds to stress, development, signaling | Aptamer activity may vary depending on local modification state |

| Potential for biosensing | High specificity, real-time detection | Biomarker potential (modification levels) | Aptamers as sensors for detecting RNA modification patterns |

| Compatibility with in vivo systems | Requires stabilization strategies | Naturally occurring mechanisms | Modified-state-responsiveness could be integrated into aptamer designs |

| Regulatory feedback loops | Currently limited to design logic | Present in many cellular pathways | Aptamers could be designed to modulate reader/writer proteins |

| Application overlap | Synthetic biology, diagnostics, therapeutics | Functional genomics, disease mechanisms | Cross-disciplinary innovation in RNA-based systems |

References

- Kang KN, Lee YS. RNA Aptamers: A Review of Recent Trends and Applications. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol [Internet]. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2012 [cited 2025 Aug 19];131:153–69. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/10_2012_136.

- Lu X, Kong KYS, Unrau PJ. Harmonizing the growing fluorogenic RNA aptamer toolbox for RNA detection and imaging. Chem Soc Rev [Internet]. Chem Soc Rev; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 6];52:4071–98. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37278064/. [CrossRef]

- Razlansari M, Jafarinejad S, rahdar A, Shirvaliloo M, Arshad R, Fathi-Karkan S, et al. Development and classification of RNA aptamers for therapeutic purposes: an updated review with emphasis on cancer. Mol Cell Biochem 2022 4787 [Internet]. Springer; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 19];478:1573–98. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11010-022-04614-x. [CrossRef]

- Lei X, Xia Y, Ma X, Wang L, Wu Y, Wu X, et al. Illuminating RNA through fluorescent light-up RNA aptamers. Biosens Bioelectron. Elsevier; 2025;271:116969. [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis J, Ming GL, Song H, He C, Shi Y. The rise of epitranscriptomics: recent developments and future directions. Trends Pharmacol Sci [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 20];45:24–38. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0165614723002547. [CrossRef]

- Wiener D, Schwartz S. The epitranscriptome beyond m6A. Nat Rev Genet 2020 222 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 5];22:119–31. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41576-020-00295-8. [CrossRef]

- Arzumanian VA, Dolgalev G V., Kurbatov IY, Kiseleva OI, Poverennaya E V. Epitranscriptome: Review of Top 25 Most-Studied RNA Modifications. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. MDPI; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 5];23:13851. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/22/13851/htm. [CrossRef]

- Germer K, Leonard M, Zhang X. RNA aptamers and their therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Int J Biochem Mol Biol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Aug 15];4:27. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3627066/.

- Chen W, Zhao X, Yang N, Li X. Single mRNA Imaging with Fluorogenic RNA Aptamers and Small-molecule Fluorophores. Angew Chemie [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 6];135:e202209813. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ange.202209813. [CrossRef]

- Lin B, Xiao F, Jiang J, Zhao Z, Zhou X. Engineered aptamers for molecular imaging. Chem Sci [Internet]. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 19];14:14039–61. Available from: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/sc/d3sc03989g. [CrossRef]

- Sundaram P, Kurniawan H, Byrne ME, Wower J. Therapeutic RNA aptamers in clinical trials. Eur J Pharm Sci. Elsevier; 2013;48:259–71. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Jiang Y, Hao SH, Yan XY, Hong DF, Naranmandura H. Aptamers: an emerging navigation tool of therapeutic agents for targeted cancer therapy. J Mater Chem B [Internet]. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 19];10:20–33. Available from: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2022/tb/d1tb02098f. [CrossRef]

- Farjami E, Campos R, Nielsen JS, Gothelf K V., Kjems J, Ferapontova EE. RNA aptamer-based electrochemical biosensor for selective and label-free analysis of dopamine. Anal Chem [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2013 [cited 2025 Aug 19];85:121–8. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ac302134s. [CrossRef]

- Su Y, Hammond MC. RNA-based fluorescent biosensors for live cell imaging of small molecules and RNAs. Curr Opin Biotechnol. Elsevier Current Trends; 2020;63:157–66. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Mohan A, Sharma NR, Kumar A, Girdhar M, Malik T, et al. Computational Frontiers in Aptamer-Based Nanomedicine for Precision Therapeutics: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 19];9:26838–62. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsomega.4c02466. [CrossRef]

- Yadav L, Kumar S, Srivastava S, Golmei P. Aptamers: A Novel Class of Targeted Therapeutics. Biosens Aptamers [Internet]. Springer, Singapore; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 20];49–85. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-96-8387-1_3.

- Liu Y, Wang N, Chan CW, Lu A, Yu Y, Zhang G, et al. The Application of Microfluidic Technologies in Aptamer Selection. Front Cell Dev Biol [Internet]. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];9:730035. Available from: www.frontiersin.org. [CrossRef]

- Domsicova M, Korcekova J, Poturnayova A, Breier A. New Insights into Aptamers: An Alternative to Antibodies in the Detection of Molecular Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci 2024, Vol 25, Page 6833 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 20];25:6833. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/13/6833/htm. [CrossRef]

- El-Husseini DM, Sayour AE, Melzer F, Mohamed MF, Neubauer H, Tammam RH. Generation and Selection of Specific Aptamers Targeting Brucella Species through an Enhanced Cell-SELEX Methodology. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. MDPI; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 20];23:6131. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/11/6131/htm. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen MG, Breaker RR. In vitro Selection and in vivo Testing of Riboswitch-inspired Aptamers. Bio-protocol [Internet]. Bio-protocol LLC; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 20];13:e4775. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10338711/. [CrossRef]

- Marton S, Reyes-Darias JA, Sánchez-Luque FJ, Romero-López C, Berzal-Herranz A. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Selection Procedures for Identifying Potentially Therapeutic DNA and RNA Molecules. Mol 2010, Vol 15, Pages 4610-4638 [Internet]. Molecular Diversity Preservation International; 2010 [cited 2025 Aug 20];15:4610–38. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/15/7/4610/htm. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Luo H, Gubu A, Yu S, Zhang H, Dai H, et al. Chemically modified aptamers for improving binding affinity to the target proteins via enhanced non-covalent bonding. Front Cell Dev Biol. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2023;11:1091809. [CrossRef]

- Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016 181 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2016 [cited 2025 Apr 12];18:31–42. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm.2016.132. [CrossRef]

- Motorin Y, Helm M. RNA nucleotide methylation: 2021 update. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 9];13:e1691. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wrna.1691. [CrossRef]

- Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, Rechavi G. The epitranscriptome toolbox. Cell [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 12];185:764–76. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0092867422001477. [CrossRef]

- Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014 155 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2014 [cited 2025 Apr 12];15:313–26. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm3785. [CrossRef]

- Meyer KD. m6A-mediated translation regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gene Regul Mech. Elsevier; 2019;1862:301–9.

- Deng L, Kumar J, Rose R, McIntyre W, Fabris D. Analyzing RNA posttranscriptional modifications to decipher the epitranscriptomic code. Mass Spectrom Rev [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];43:5–38. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/mas.21798. [CrossRef]

- Mateos PA, Zhou Y, Zarnack K, Eyras E. Concepts and methods for transcriptome-wide prediction of chemical messenger RNA modifications with machine learning. Brief Bioinform [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 26];24:1–14. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Jolly P, Estrela P, Ladomery M. Oligonucleotide-based systems: DNA, microRNAs, DNA/RNA aptamers. Essays Biochem [Internet]. Portland Press; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 16];60:27–35. Available from: /essaysbiochem/article/60/1/27/78209/Oligonucleotide-based-systems-DNA-microRNAs-DNA. [CrossRef]

- Weigand JE, Suess B. Aptamers and riboswitches: Perspectives in biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. Springer; 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 16];85:229–36. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-009-2194-2. [CrossRef]

- Stoltenburg R, Reinemann C, Strehlitz B. SELEX—A (r)evolutionary method to generate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands. Biomol Eng. Elsevier; 2007;24:381–403. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Zu Y. Aptamers and Their Applications in Nanomedicine. Small [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 16];11:2352–64. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/smll.201403073. [CrossRef]

- Ruscito A, DeRosa MC. Small-molecule binding aptamers: Selection strategies, characterization, and applications. Front Chem [Internet]. Frontiers Media S. A; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 16];4:188509. Available from: www.frontiersin.org. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Rossi J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: current potential and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016 163 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 16];16:181–202. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd.2016.199.

- Shraim AS, Abdel Majeed BA, Al-Binni MA, Hunaiti A. Therapeutic Potential of Aptamer-Protein Interactions. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 16];5:1211–27. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acsptsci.2c00156. [CrossRef]

- Driscoll J, Gondaliya P, Zinn DA, Jain R, Yan IK, Dong H, et al. Using aptamers for targeted delivery of RNA therapies. Mol Ther [Internet]. Elsevier; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 16];33:1344–67. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S1525001625001741. [CrossRef]

- Kratschmer C, Levy M. Effect of Chemical Modifications on Aptamer Stability in Serum. Nucleic Acid Ther [Internet]. Nucleic Acid Ther; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 16];27:335–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28945147/. [CrossRef]

- Nimjee SM, White RR, Becker RC, Sullenger BA. Aptamers as Therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol [Internet]. Annual Reviews Inc.; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 16];57:61–79. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104558. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira-Antunes B, Ferreira HA. Nucleic Acid Aptamer-Based Biosensors: A Review. Biomed 2023, Vol 11, Page 3201 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 16];11:3201. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/11/12/3201/htm. [CrossRef]

- Sheraz M, Sun XF, Wang Y, Chen J, Sun L. Recent Developments in Aptamer-Based Sensors for Diagnostics. Sensors 2024, Vol 24, Page 7432 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 16];24:7432. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/24/23/7432/htm. [CrossRef]

- McKeague M, Wong RS, Smolke CD. Opportunities in the design and application of RNA for gene expression control. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 16];44:2987–99. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Paige JS, Wu KY, Jaffrey SR. RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein. Science (80- ) [Internet]. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 16];333:642–6. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1207339. [CrossRef]

- Jonkhout N, Tran J, Smith MA, Schonrock N, Mattick JS, Novoa EM. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 16];23:1754–69. Available from: http://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/23/12/1754.full. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Zhu L, Wang X, Jin H. RNA-based therapeutics: an overview and prospectus. Cell Death Dis 2022 137 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 16];13:1–15. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41419-022-05075-2.

- Trivedi J, Yasir M, Maurya RK, Tripathi AS. Aptamer-based Theranostics in Oncology: Design Strategies and Limitations. BIO Integr [Internet]. Compuscript; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 15];5:993. Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.15212/bioi-2024-0002. [CrossRef]

- Haran V, Lenka N. Deciphering the Epitranscriptomic Signatures in Cell Fate Determination and Development. Stem Cell Rev Reports [Internet]. Humana Press Inc.; 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 12];15:474–96. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12015-019-09894-3. [CrossRef]

- Che YH, Lee H, Kim YJ. New insights into the epitranscriptomic control of pluripotent stem cell fate. Exp Mol Med 2022 5410 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 12];54:1643–51. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-022-00824-x. [CrossRef]

- Livneh I, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Dominissini D. The m6A epitranscriptome: Transcriptome plasticity in brain development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. Nature Research; 2020;21:36-51. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zhai Y, Zhang S, Dai X, Li Z. Roles of N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) in Stem Cell Fate Decisions and Early Embryonic Development in Mammals. Front Cell Dev Biol [Internet]. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 12];8:566543. Available from: www.frontiersin.org. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y, Liu P, Li Y, Wang W, Jia H, Bai Y, et al. Regulatory role of m6A epitranscriptomic modifications in normal development and congenital malformations during embryogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother [Internet]. Biomed Pharmacother; 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 21];173. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38394844/. [CrossRef]

- Ahi EP. Regulation of Skeletogenic Pathways by m6A RNA Modification: A Comprehensive Review. Calcif Tissue Int 2025 1161 [Internet]. Springer; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16];116:1–23. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00223-025-01367-9. [CrossRef]

- Cayir A, Byun HM, Barrow TM. Environmental epitranscriptomics. Environ Res. Academic Press; 2020;189:109885.

- Ahi EP, Singh P. An emerging orchestrator of ecological adaptation: m6A regulation of post-transcriptional mechanisms. Mol Ecol. 2024;17545.

- Ahi EP, Schenekar T. The Promise of Environmental RNA Research Beyond mRNA. Mol Ecol [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 19];34:e17787. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/mec.17787. [CrossRef]

- Sikorski V, Selberg S, Lalowski M, Karelson M, Kankuri E. The structure and function of YTHDF epitranscriptomic m6A readers. Trends Pharmacol Sci [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16];44:335–53. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0165614723000627. [CrossRef]

- Rodell R, Robalin N, Martinez NM. Why U matters: detection and functions of pseudouridine modifications in mRNAs. Trends Biochem Sci [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 23];49:12–27. Available from: http://www.cell.com/article/S0968000423002773/fulltext. [CrossRef]

- Monroe J, Eyler DE, Mitchell L, Deb I, Bojanowski A, Srinivas P, et al. N1-Methylpseudouridine and pseudouridine modifications modulate mRNA decoding during translation. Nat Commun 2024 151 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];15:1–11. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-51301-0. [CrossRef]

- Chen YS, Yang WL, Zhao YL, Yang YG. Dynamic transcriptomic m5C and its regulatory role in RNA processing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 26];12:e1639. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wrna.1639. [CrossRef]

- Höfler S, Duss O. Interconnections between m6A RNA modification, RNA structure, and protein–RNA complex assembly. Life Sci Alliance [Internet]. Life Science Alliance; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];7. Available from: https://www.life-science-alliance.org/content/7/1/e202302240.

- Fagre C, Gilbert W. Beyond reader proteins: RNA binding proteins and RNA modifications in conversation to regulate gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];15:e1834. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wrna.1834. [CrossRef]

- Tanzer A, Hofacker IL, Lorenz R. RNA modifications in structure prediction – Status quo and future challenges. Methods. Academic Press; 2019;156:32–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA–protein interactions. Nat 2015 5187540 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 20];518:560–4. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14234. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Shi H, Rangadurai A, Nussbaumer F, Chu CC, Erharter KA, et al. A quantitative model predicts how m6A reshapes the kinetic landscape of nucleic acid hybridization and conformational transitions. Nat Commun 2021 121 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 26];12:1–17. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-25253-8. [CrossRef]

- Sağlam B, Akgül B. An Overview of Current Detection Methods for RNA Methylation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, Vol 25, Page 3098 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 16];25:3098. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/6/3098/htm. [CrossRef]

- Zhong ZD, Xie YY, Chen HX, Lan YL, Liu XH, Ji JY, et al. Systematic comparison of tools used for m6A mapping from nanopore direct RNA sequencing. Nat Commun 2023 141 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16];14:1–14. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-37596-5. [CrossRef]

- Fallah A, Imani Fooladi AA, Havaei SA, Mahboobi M, Sedighian H. Recent advances in aptamer discovery, modification and improving performance. Biochem Biophys Reports. Elsevier; 2024;40:101852. [CrossRef]

- Troisi R, Sica F. Aptamers: Functional-Structural Studies and Biomedical Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2022, Vol 23, Page 4796 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 16];23:4796. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/9/4796/htm. [CrossRef]

- Liu WW, Zheng SQ, Li T, Fei YF, Wang C, Zhang S, et al. RNA modifications in cellular metabolism: implications for metabolism-targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024 91 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 16];9:1–30. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-024-01777-5. [CrossRef]

- Sasso JM, Ambrose BJB, Tenchov R, Datta RS, Basel MT, Delong RK, et al. The Progress and Promise of RNA Medicine-An Arsenal of Targeted Treatments. J Med Chem [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 16];65:6975–7015. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00024. [CrossRef]

- Kornienko I V., Aramova OY, Tishchenko AA, Rudoy D V., Chikindas ML. RNA Stability: A Review of the Role of Structural Features and Environmental Conditions. Molecules [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 6];29:5978. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11676819/. [CrossRef]

- Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell. Cell Press; 2017. p. 1187–200. [CrossRef]

- Stewart JM. RNA nanotechnology on the horizon: Self-assembly, chemical modifications, and functional applications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. Elsevier Current Trends; 2024;81:102479. [CrossRef]

- Hopfinger MC, Kirkpatrick CC, Znosko BM. Predictions and analyses of RNA nearest neighbor parameters for modified nucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 27];48:8901–13. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Roost C, Lynch SR, Batista PJ, Qu K, Chang HY, Kool ET. Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: A spring-loaded base modification. J Am Chem Soc [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2015 [cited 2025 Apr 18];137:2107–15. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja513080v. [CrossRef]

- Kierzek E, Malgowska M, Lisowiec J, Turner DH, Gdaniec Z, Kierzek R. The contribution of pseudouridine to stabilities and structure of RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2014 [cited 2025 Apr 16];42:3492–501. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Spenkuch F, Motorin Y, Helm M. Pseudouridine: Still mysterious, but never a fake (uridine)! RNA Biol [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2014 [cited 2025 Aug 27];11:1540–54. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.4161/15476286.2014.992278. [CrossRef]

- Jones AN, Tikhaia E, Mourão A, Sattler M. Structural effects of m6A modification of the Xist A-repeat AUCG tetraloop and its recognition by YTHDC1. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 27];50:2350–62. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Mayer G. The Chemical Biology of Aptamers. Angew Chemie Int Ed [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 16];48:2672–89. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/anie.200804643. [CrossRef]

- Gelinas AD, Davies DR, Janjic N. Embracing proteins: structural themes in aptamer–protein complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. Elsevier Current Trends; 2016;36:122–32. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Lei Y, Chen M, Ma H, Shen T, Zhang Y, et al. A Demethylation-Switchable Aptamer Design Enables Lag-Free Monitoring of m6A Demethylase FTO with Energy Self-Sufficient and Structurally Integrated Features. J Am Chem Soc [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 20];146:34638–50. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jacs.4c12884. [CrossRef]

- Svensen N, Jaffrey SR. Fluorescent RNA Aptamers as a Tool to Study RNA-Modifying Enzymes. Cell Chem Biol [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2016 [cited 2025 Aug 16];23:415–25. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2451945616300046. [CrossRef]

- Odeh F, Nsairat H, Alshaer W, Ismail MA, Esawi E, Qaqish B, et al. Aptamers Chemistry: Chemical Modifications and Conjugation Strategies. Mol 2020, Vol 25, Page 3 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 16];25:3. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/25/1/3/htm. [CrossRef]

- Eremeeva E, Fikatas A, Margamuljana L, Abramov M, Schols D, Groaz E, et al. Highly stable hexitol based XNA aptamers targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 16];47:4927–39. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Low JT, Weeks KM. SHAPE-directed RNA secondary structure prediction. Methods. Academic Press; 2010;52:150–8. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson KA, Merino EJ, Weeks KM. Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nat Protoc 2006 13 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2006 [cited 2025 Aug 16];1:1610–6. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nprot.2006.249. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira R, Pinho E, Sousa AL, DeStefano JJ, Azevedo NF, Almeida C. Improving aptamer performance with nucleic acid mimics: de novo and post-SELEX approaches. Trends Biotechnol [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 16];40:549–63. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0167779921002274. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Qi X, Yan X, Huang Y, Liang X, Zhang L, et al. Engineering Aptamer with Enhanced Affinity by Triple Helix-Based Terminal Fixation. J Am Chem Soc [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 16];141:17493–7. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jacs.9b09292. [CrossRef]

- Soukup GA, Emilsson GAM, Breaker RR. Altering molecular recognition of RNA aptamers by allosteric selection. J Mol Biol. Academic Press; 2000;298:623–32. [CrossRef]

- Hoetzel J, Suess B. Structural Changes in Aptamers are Essential for Synthetic Riboswitch Engineering. J Mol Biol. Academic Press; 2022;434:167631. [CrossRef]

- Kelvin D, Suess B. Tapping the potential of synthetic riboswitches: reviewing the versatility of the tetracycline aptamer. RNA Biol [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 16];20:457–68. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15476286.2023.2234732%4010.1080/tfocoll.2024.0.issue-Synthetic_RNA_Biology. [CrossRef]

- Hashmi MATS, Fatima H, Ahmad S, Rehman A, Safdar F. The interplay between epitranscriptomic RNA modifications and neurodegenerative disorders: Mechanistic insights and potential therapeutic strategies. Ibrain [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 16];10:395–426. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ibra.12183. [CrossRef]

- Arguello AE, Leach RW, Kleiner RE. In Vitro Selection with a Site-Specifically Modified RNA Library Reveals the Binding Preferences of N6-Methyladenosine Reader Proteins. Biochemistry [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 26];58:3386–95. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00485. [CrossRef]

- Brown A, Brill J, Amini R, Nurmi C, Li Y. Development of Better Aptamers: Structured Library Approaches, Selection Methods, and Chemical Modifications. Angew Chemie Int Ed [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];63:e202318665. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/anie.202318665. [CrossRef]

- Felix AS, Quillin AL, Mousavi S, Heemstra JM. Harnessing Nature’s Molecular Recognition Capabilities to Map and Study RNA Modifications. Acc Chem Res [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 27]; Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00287. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Ma Y, Mou Q, Shao X, Lyu M, Garcia V, et al. Sialic acid aptamer and RNA in situ hybridization-mediated proximity ligation assay for spatial imaging of glycoRNAs in single cells. Nat Protoc 2025 207 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 27];20:1930–50. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41596-024-01103-x. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Zhao S, Su C, Han Q, Han Y, Tian X, et al. Construction of a Quantum-Dot-Based FRET Nanosensor through Direct Encoding of Streptavidin-Binding RNA Aptamers for N6-Methyladenosine Demethylase Detection. Anal Chem [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 3];95:13201–10. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c02149. [CrossRef]

- Vögele J, Duchardt-Ferner E, Kruse H, Zhang Z, Sponer J, Krepl M, et al. Structural and dynamic effects of pseudouridine modifications on noncanonical interactions in RNA. RNA [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 27];29:790–807. Available from: http://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/29/6/790.full. [CrossRef]

- Gu L, Zheng J, Zhang Y, Wang D, Liu J. Selection and Characterization of DNA Aptamers for Cytidine and Uridine. ChemBioChem [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 27];25:e202300656. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cbic.202300656. [CrossRef]

- Yoo H, Jo H, Oh SS. Detection and beyond: challenges and advances in aptamer-based biosensors. Mater Adv [Internet]. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 6];1:2663–87. Available from: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2020/ma/d0ma00639d. [CrossRef]

- Ying X, Huang C, Li T, Li T, Gao M, Wang F, et al. An RNA Methylation-Sensitive AIEgen-Aptamer Reporting System for Quantitatively Evaluating m6A Methylase and Demethylase Activities. ACS Chem Biol [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 20];19:162–72. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acschembio.3c00613. [CrossRef]

- Catuogno S, Esposito CL, Ungaro P, De Franciscis V. Nucleic Acid Aptamers Targeting Epigenetic Regulators: An Innovative Therapeutic Option. Pharm 2018, Vol 11, Page 79 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 19];11:79. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/11/3/79/htm. [CrossRef]

- Yin Y, Morgunova E, Jolma A, Kaasinen E, Sahu B, Khund-Sayeed S, et al. Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science (80- ) [Internet]. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 19];356. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaj2239. [CrossRef]

- Ahi EP, Khorshid M. Potentials of RNA biosensors in developmental biology. Dev Biol [Internet]. Academic Press; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 30];526:173–88. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0012160625002027. [CrossRef]

- Murray MT, Wetmore SD. Unlocking precision in aptamer engineering: a case study of the thrombin binding aptamer illustrates why modification size, quantity, and position matter. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 19];52:10823–35. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Valsangkar V, Vangaveti S, Lee GW, Fahssi WM, Awan WS, Huang Y, et al. Structural and Binding Effects of Chemical Modifications on Thrombin Binding Aptamer (TBA). Mol 2021, Vol 26, Page 4620 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 19];26:4620. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/15/4620/htm. [CrossRef]

- Seelam Prabhakar P, A Manderville R, D Wetmore S. Impact of the Position of the Chemically Modified 5-Furyl-2′-Deoxyuridine Nucleoside on the Thrombin DNA Aptamer–Protein Complex: Structural Insights into Aptamer Response from MD Simulations. Mol 2019, Vol 24, Page 2908 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 19];24:2908. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/24/16/2908/htm.

- Bowles IE, Orellana EA. Rethinking RNA Modifications: Therapeutic Strategies for Targeting Dysregulated RNA. J Mol Biol. Academic Press; 2025;437:169046. [CrossRef]

- Qi S, Duan N, Khan IM, Dong X, Zhang Y, Wu S, et al. Strategies to manipulate the performance of aptamers in SELEX, post-SELEX and microenvironment. Biotechnol Adv. Elsevier; 2022;55:107902. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Galloway KE. RNA-based controllers for engineering gene and cell therapies. Curr Opin Biotechnol. Elsevier Current Trends; 2024;85:103026. [CrossRef]

- Hou Q, Jaffrey SR. Synthetic biology tools to promote the folding and function of RNA aptamers in mammalian cells. RNA Biol [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 26];20:198–206. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15476286.2023.2206248%4010.1080/tfocoll.2024.0.issue-Synthetic_RNA_Biology. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert W V., Nachtergaele S. mRNA Regulation by RNA Modifications. Annu Rev Biochem [Internet]. Annu Rev Biochem; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 26];92:175–98. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37018844/.

- Vazquez-Anderson J, Contreras LM. Regulatory RNAs: charming gene management styles for synthetic biology applications. RNA Biol [Internet]. RNA Biol; 2013 [cited 2025 Aug 19];10:1778–97. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24356572/.

- Shanidze N, Lenkeit F, Hartig JS, Funck D. A Theophylline-Responsive Riboswitch Regulates Expression of Nuclear-Encoded Genes. Plant Physiol [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 19];182:123–35. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Khalil AS, Collins JJ. Synthetic biology: applications come of age. Nat Rev Genet 2010 115 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2010 [cited 2025 Aug 20];11:367–79. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg2775. [CrossRef]

- Maung NW, Smolke CD. Higher-order cellular information processing with synthetic RNA devices. Science (80- ) [Internet]. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2008 [cited 2025 Aug 20];322:456–60. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1160311.

- Kundert K, Lucas JE, Watters KE, Fellmann C, Ng AH, Heineike BM, et al. Controlling CRISPR-Cas9 with ligand-activated and ligand-deactivated sgRNAs. Nat Commun 2019 101 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2019 [cited 2025 Aug 20];10:1–11. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-09985-2. [CrossRef]

- Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nat 2002 4196910 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2002 [cited 2025 Aug 20];419:952–6. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature01145. [CrossRef]

- Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Zhang QC, Crisalli P, Lee B, Jung JW, et al. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nat 2015 5197544 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 26];519:486–90. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14263. [CrossRef]

- Feagin TA, Maganzini N, Soh HT. Strategies for Creating Structure-Switching Aptamers. ACS Sensors [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 26];3:1611–5. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acssensors.8b00516. [CrossRef]

- Akhter S. Mechanism of ligand binding to target RNA aptamer. Biophys J [Internet]. Elsevier BV; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 20];123:544a-545a. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0006349523040006. [CrossRef]

- Lyu M, Chan CH, Chen Z, Liu Y, Yu Y. Advantages, applications, and future directions of in vivo aptamer SELEX: A review. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids [Internet]. Cell Press; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 20];36. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2162253125001295. [CrossRef]

- Bayani A, Abosaoda MK, Rizaev J, Nazari M, Jafari Z, Soleimani Samarkhazan H. Aptamer-based approaches in leukemia: a paradigm shift in targeted therapy. Clin Exp Med 2025 251 [Internet]. Springer; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 20];25:1–14. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10238-025-01724-w. [CrossRef]

- Ng EWM, Shima DT, Calias P, Cunningham ET, Guyer DR, Adamis AP. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006 52 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2006 [cited 2025 Aug 20];5:123–32. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd1955. [CrossRef]

- Ni S, Zhuo Z, Pan Y, Yu Y, Li F, Liu J, et al. Recent Progress in Aptamer Discoveries and Modifications for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];13:9500–19. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsami.0c05750. [CrossRef]

- Doessing H, Vester B. Locked and Unlocked Nucleosides in Functional Nucleic Acids. Mol 2011, Vol 16, Pages 4511-4526 [Internet]. Molecular Diversity Preservation International; 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 20];16:4511–26. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/16/6/4511/htm. [CrossRef]

- Bunka DHJ, Platonova O, Stockley PG. Development of aptamer therapeutics. Curr Opin Pharmacol. Elsevier; 2010;10:557–62.

- Li Q, Liu J, Guo L, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Liu H, et al. Decoding the interplay between m6A modification and stress granule stability by live-cell imaging. Sci Adv [Internet]. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];10:5689. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adp5689. [CrossRef]

- Marayati BF, Thompson MG, Holley CL, Horner SM, Meyer KD. Programmable protein expression using a genetically encoded m6A sensor. Nat Biotechnol 2024 429 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];42:1417–28. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-023-01978-3. [CrossRef]

- Tegowski M, Meyer KD. Studying m6A in the brain: a perspective on current methods, challenges, and future directions. Front Mol Neurosci. Frontiers Media SA; 2024;17:1393973. [CrossRef]

- Tang W, Hu JH, Liu DR. Aptazyme-embedded guide RNAs enable ligand-responsive genome editing and transcriptional activation. Nat Commun 2017 81 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 26];8:1–8. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms15939. [CrossRef]

- Horner SM, Thompson MG. Challenges to mapping and defining m6A function in viral RNA. RNA [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];30:482–90. Available from: http://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/30/5/482.full. [CrossRef]

- Shachar R, Dierks D, Garcia-Campos MA, Uzonyi A, Toth U, Rossmanith W, et al. Dissecting the sequence and structural determinants guiding m6A deposition and evolution via inter- and intra-species hybrids. Genome Biol [Internet]. BioMed Central Ltd; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];25:1–29. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s13059-024-03182-1. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Lu Y, Wang Y, Wen X, Qi C, Piao W, et al. Current progress in strategies to profile transcriptomic m6A modifications. Front Cell Dev Biol. Frontiers Media SA; 2024;12:1392159. [CrossRef]

- Varenyk Y, Spicher T, Hofacker IL, Lorenz R. Modified RNAs and predictions with the ViennaRNA Package. Bioinformatics [Internet]. Bioinformatics; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 26];39. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37971965/. [CrossRef]

- Esfahani NG, Stein AJ, Akeson S, Tzadikario T, Jain M. Evaluation of Nanopore direct RNA sequencing updates for modification detection. bioRxiv [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 26];2025.05.01.651717. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.05.01.651717v1.

- Wu Y, Shao W, Yan M, Wang Y, Xu P, Huang G, et al. Transfer learning enables identification of multiple types of RNA modifications using nanopore direct RNA sequencing. Nat Commun 2024 151 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];15:1–19. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-48437-4. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan CJ, Marayati BF, Bhatia J, Meyer KD. In situ visualization of m6A sites in cellular mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 26];51:e101–e101. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- He B, Chen Y, Yi C. Quantitative mapping of the mammalian epitranscriptome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. Elsevier Current Trends; 2024;87:102212. [CrossRef]

- Motorin Y, Helm M. General Principles and Limitations for Detection of RNA Modifications by Sequencing. Acc Chem Res [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 26];57:275–88. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.accounts.3c00529. [CrossRef]

- Hendra C, Pratanwanich PN, Wan YK, Goh WSS, Thiery A, Göke J. Detection of m6A from direct RNA sequencing using a multiple instance learning framework. Nat Methods [Internet]. Nat Methods; 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 23];19:1590–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36357692/. [CrossRef]

- Sczepanski JT, Joyce GF. Binding of a structured d-RNA molecule by an l-RNA aptamer. J Am Chem Soc [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2013 [cited 2025 Aug 20];135:13290–3. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja406634g. [CrossRef]

- Dey S, Sczepanski JT. In vitro selection of l-DNA aptamers that bind a structured d-RNA molecule. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 20];48:1669–80. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Cawte AD, Unrau PJ, Rueda DS. Live cell imaging of single RNA molecules with fluorogenic Mango II arrays. Nat Commun 2020 111 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2020 [cited 2024 Dec 27];11:1–11. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-14932-7. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Chen W, Reheman Z, Jiang H, Wu J, Li X. Genetically encoded RNA-based sensors with Pepper fluorogenic aptamer. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 20];51:8322–36. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Xiao F, Su H, Liu H, Xu J, Tang H, et al. Inert Pepper aptamer-mediated endogenous mRNA recognition and imaging in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 20];50:e84–e84. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Fu Q, Williams BAR, Azzaz AM, Shogren-Knaak MA, Chaput JC, et al. Recognition imaging of acetylated chromatin using a DNA aptamer. Biophys J [Internet]. Biophysical Society; 2009 [cited 2025 Aug 20];97:1804–7. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S0006349509012296. [CrossRef]

- Gao W, Xu L, Jing J, Zhang X. A far red emissive RNA aptamer–fluorophore system for demethylase FTO detection: design and optimization. New J Chem [Internet]. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 20];47:5238–43. Available from: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/nj/d3nj00043e. [CrossRef]

- Jenison RD, Gill SC, Pardi A, Polisky B. High-Resolution Molecular Discrimination by RNA. Science (80- ) [Internet]. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 1994 [cited 2025 Aug 20];263:1425–9. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.7510417. [CrossRef]

- Pham H, Kumar M, Martinez AR, Ali M, Lowery RG. Development and validation of a generic methyltransferase enzymatic assay based on an SAH riboswitch. SLAS Discov. Elsevier; 2024;29:100161. [CrossRef]

- Berens C, Groher F, Suess B. RNA aptamers as genetic control devices: The potential of riboswitches as synthetic elements for regulating gene expression. Biotechnol J [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015 [cited 2025 Aug 26];10:246–57. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/biot.201300498. [CrossRef]

- Khosravi HM, Jantsch MF. Site-directed RNA editing: recent advances and open challenges. RNA Biol [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 26];18:41–50. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15476286.2021.1983288. [CrossRef]

- Ai X, Ding S, Zhou S, Du F, Liu S, Cui X, et al. Enhancing RNA editing efficiency and specificity with engineered ADAR2 guide RNAs. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids [Internet]. Cell Press; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 26];36:102447. Available from: https://www.cell.com/action/showFullText?pii=S2162253125000010. [CrossRef]

- Flamand MN, Ke K, Tamming R, Meyer KD. Single-molecule identification of the target RNAs of different RNA binding proteins simultaneously in cells. Genes Dev [Internet]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 26];36:1002–15. Available from: http://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/36/17-18/1002.full. [CrossRef]

- Okuda M, Fourmy D, Yoshizawa S. Use of Baby Spinach and Broccoli for imaging of structured cellular RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 20];45:1404–15. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Al Shanaa O, Rumyantsev A, Sambuk E, Padkina M. In Vivo Production of RNA Aptamers and Nanoparticles: Problems and Prospects. Mol 2021, Vol 26, Page 1422 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];26:1422. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/5/1422/htm. [CrossRef]

- Zhang HL, Lv C, Li ZH, Jiang S, Cai D, Liu SS, et al. Analysis of aptamer-target binding and molecular mechanisms by thermofluorimetric analysis and molecular dynamics simulation. Front Chem [Internet]. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 20];11:1144347. Available from: https://zdock.umassmed.edu/. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Li N, Gorenstein DG. Strategies for the discovery of therapeutic aptamers. Expert Opin Drug Discov [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 20];6:75–87. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1517/17460441.2011.537321. [CrossRef]

- Vorobyeva MA, Davydova AS, Vorobjev PE, Pyshnyi D V., Venyaminova AG. Key Aspects of Nucleic Acid Library Design for in Vitro Selection. Int J Mol Sci 2018, Vol 19, Page 470 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 20];19:470. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/2/470/htm. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Ren Z, Sun Y, Xu L, Wei D, Tan W, et al. Investigation of the Relationship between Aptamers’ Targeting Functions and Human Plasma Proteins. ACS Nano [Internet]. American Chemical Society; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 20];17:24329–42. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acsnano.3c10238. [CrossRef]

- Kelly L, Maier KE, Yan A, Levy M. A comparative analysis of cell surface targeting aptamers. Nat Commun 2021 121 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 20];12:1–14. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-26463-w. [CrossRef]

- Grozhik A V., Jaffrey SR. Distinguishing RNA modifications from noise in epitranscriptome maps. Nat Chem Biol 2018 143 [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 26];14:215–25. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nchembio.2546.

- Sarkar A, Gasperi W, Begley U, Nevins S, Huber SM, Dedon PC, et al. Detecting the epitranscriptome. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2021 [cited 2025 Aug 26];12:e1663. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wrna.1663. [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic KD, Gilbert JC, Jilma B. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of aptamers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. Elsevier; 2018;134:36–50. [CrossRef]

- Hostiuc M, Scafa A, Iancu B, Iancu D, Isailă OM, Ion OM, et al. Ethical implications of developing RNA-based therapies for cardiovascular disorders. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. Frontiers Media SA; 2024;12:1370403. [CrossRef]

- Mubarak G, Zahir FR. Recent Major Transcriptomics and Epitranscriptomics Contributions toward Personalized and Precision Medicine. J Pers Med 2022, Vol 12, Page 199 [Internet]. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 26];12:199. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/12/2/199/htm. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).