Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

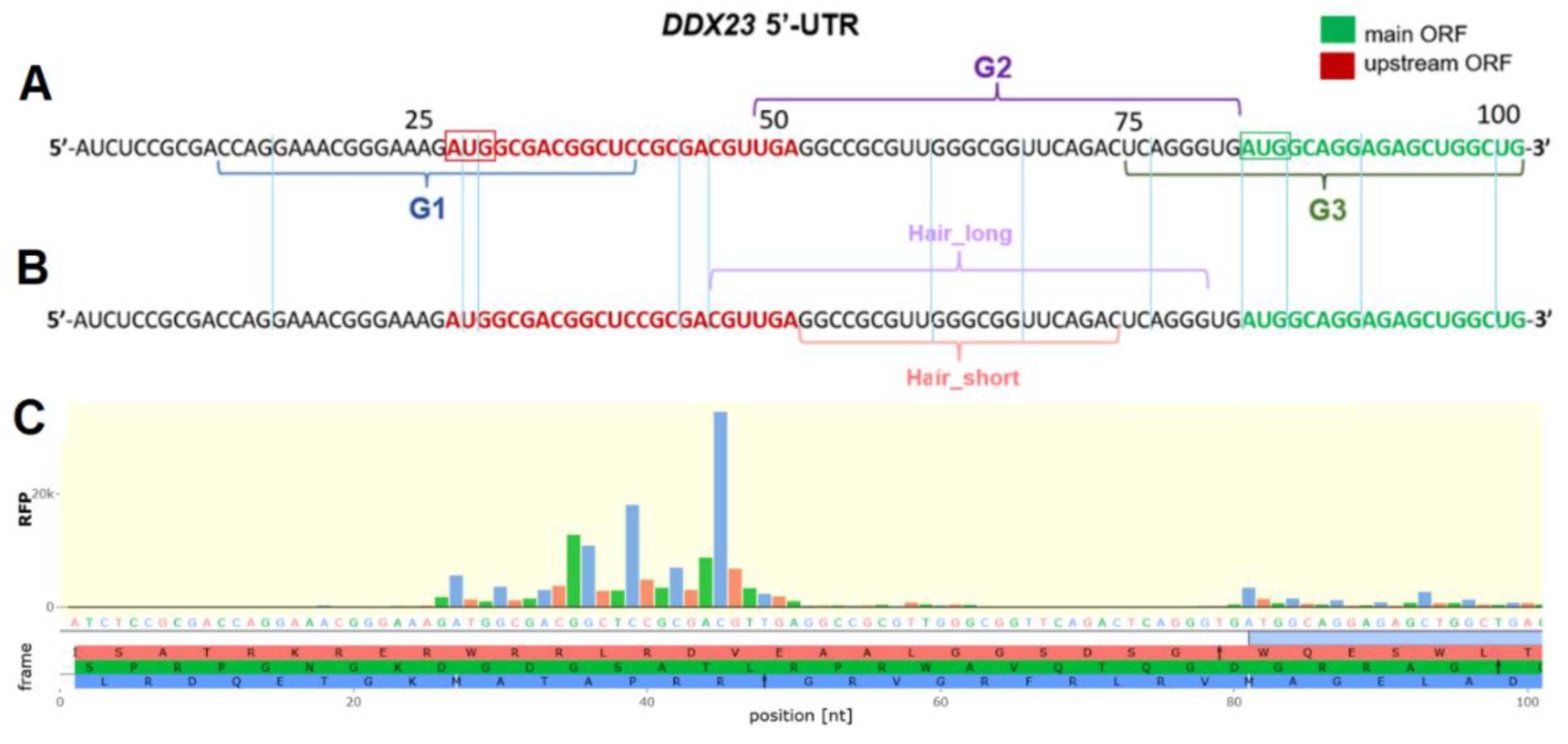

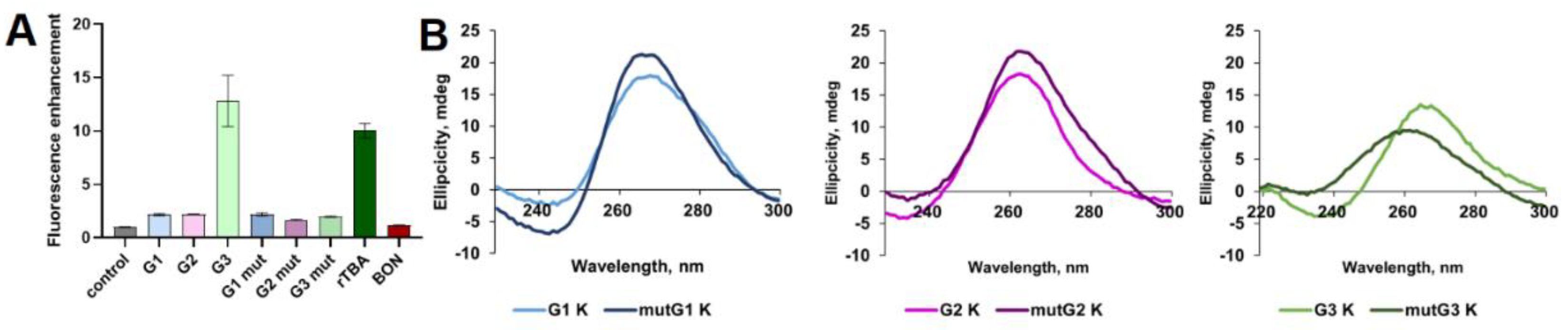

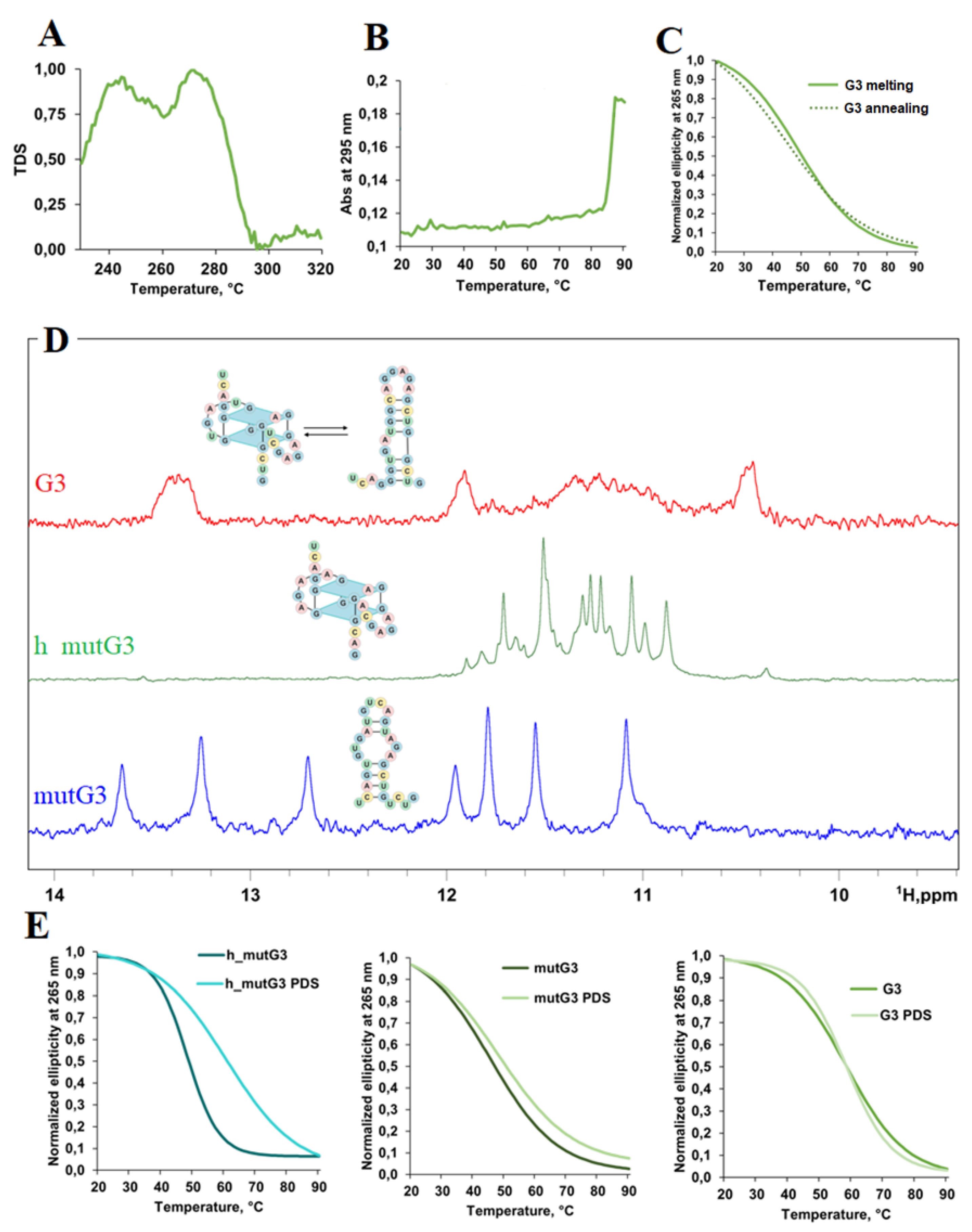

2.1. Analysis of Potential Regulatory G-quadruplex Elements in 5’ UTR of DDX23 mRNA

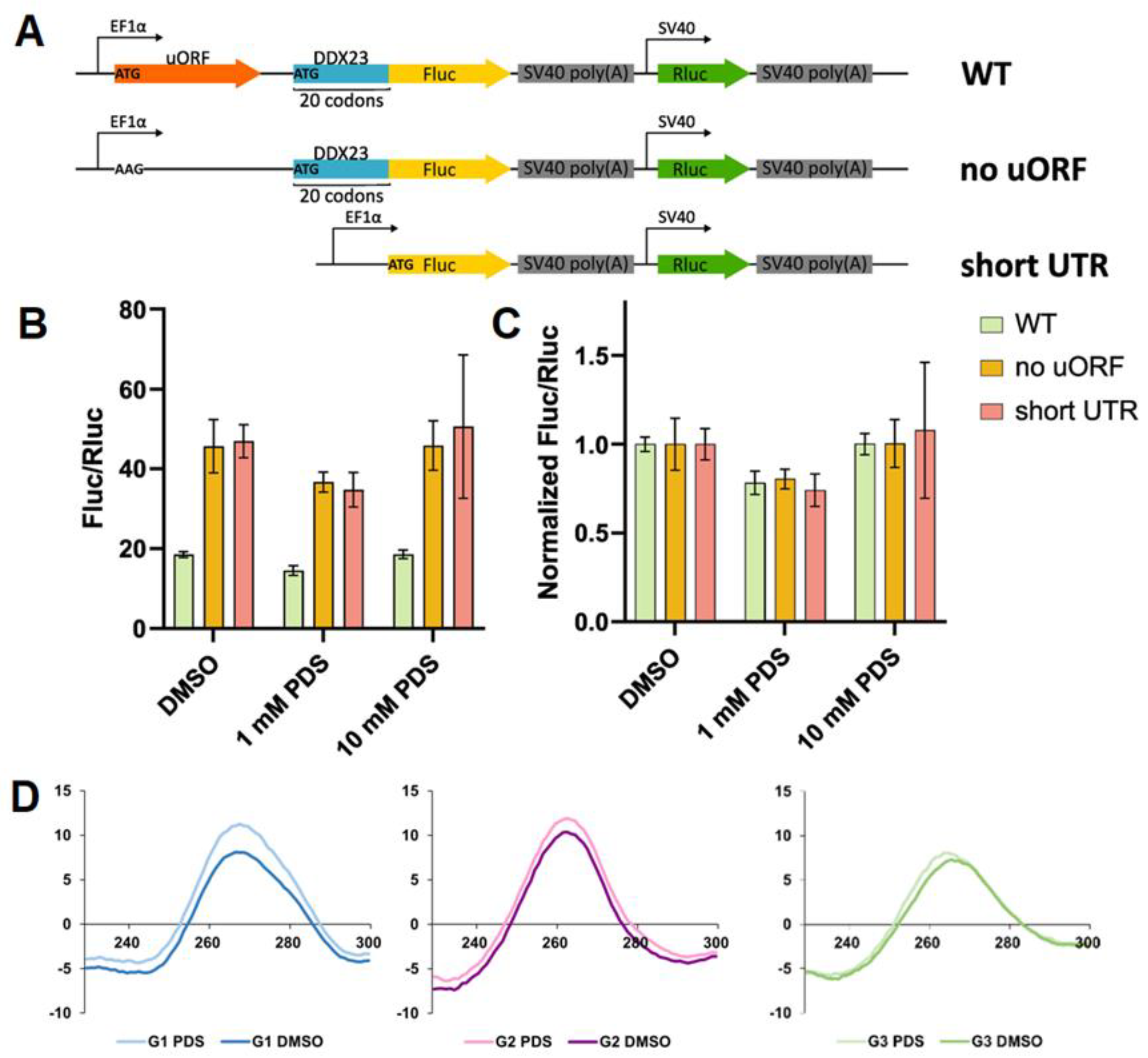

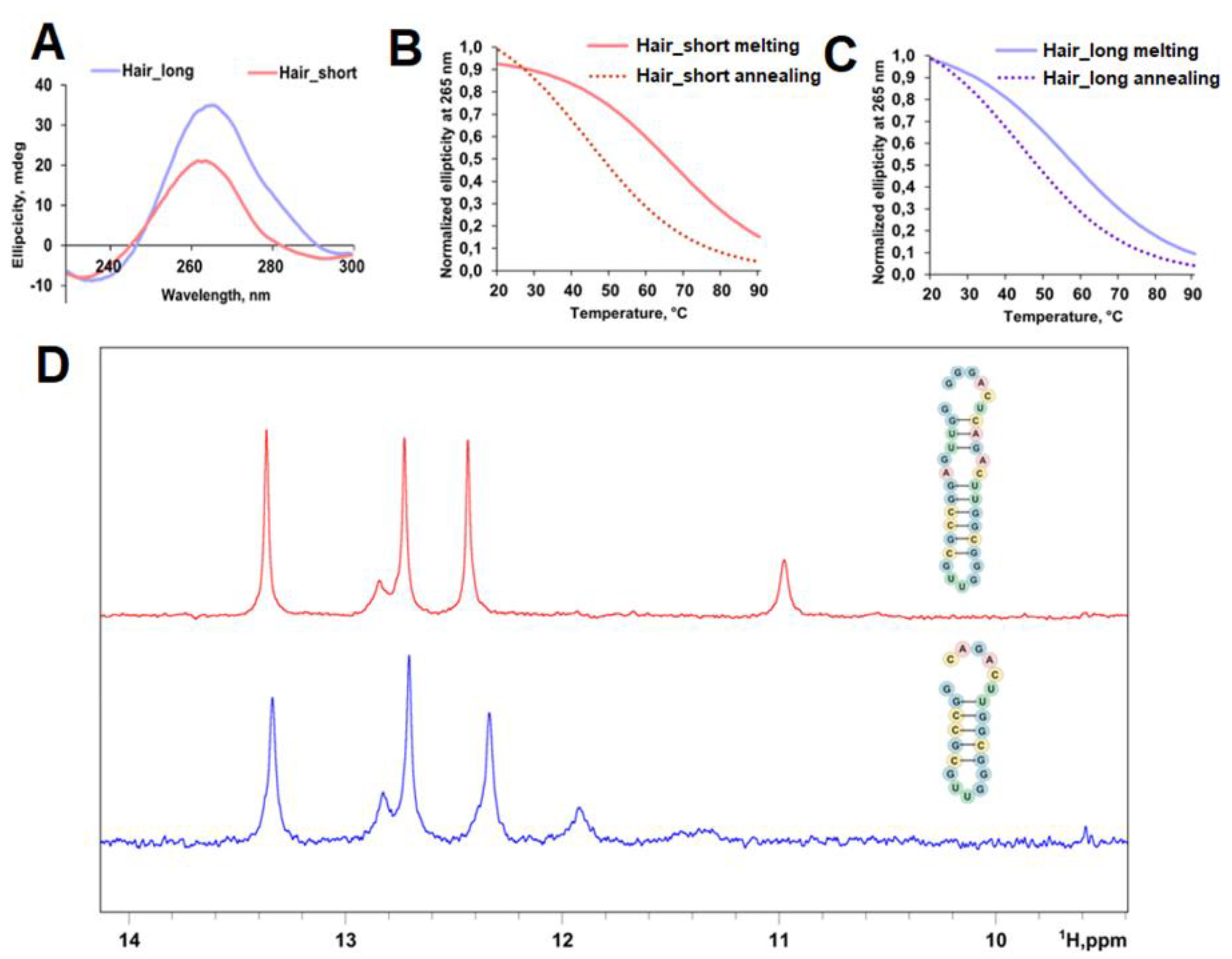

2.2. Analysis of Regulatory Stem-Loop Elements

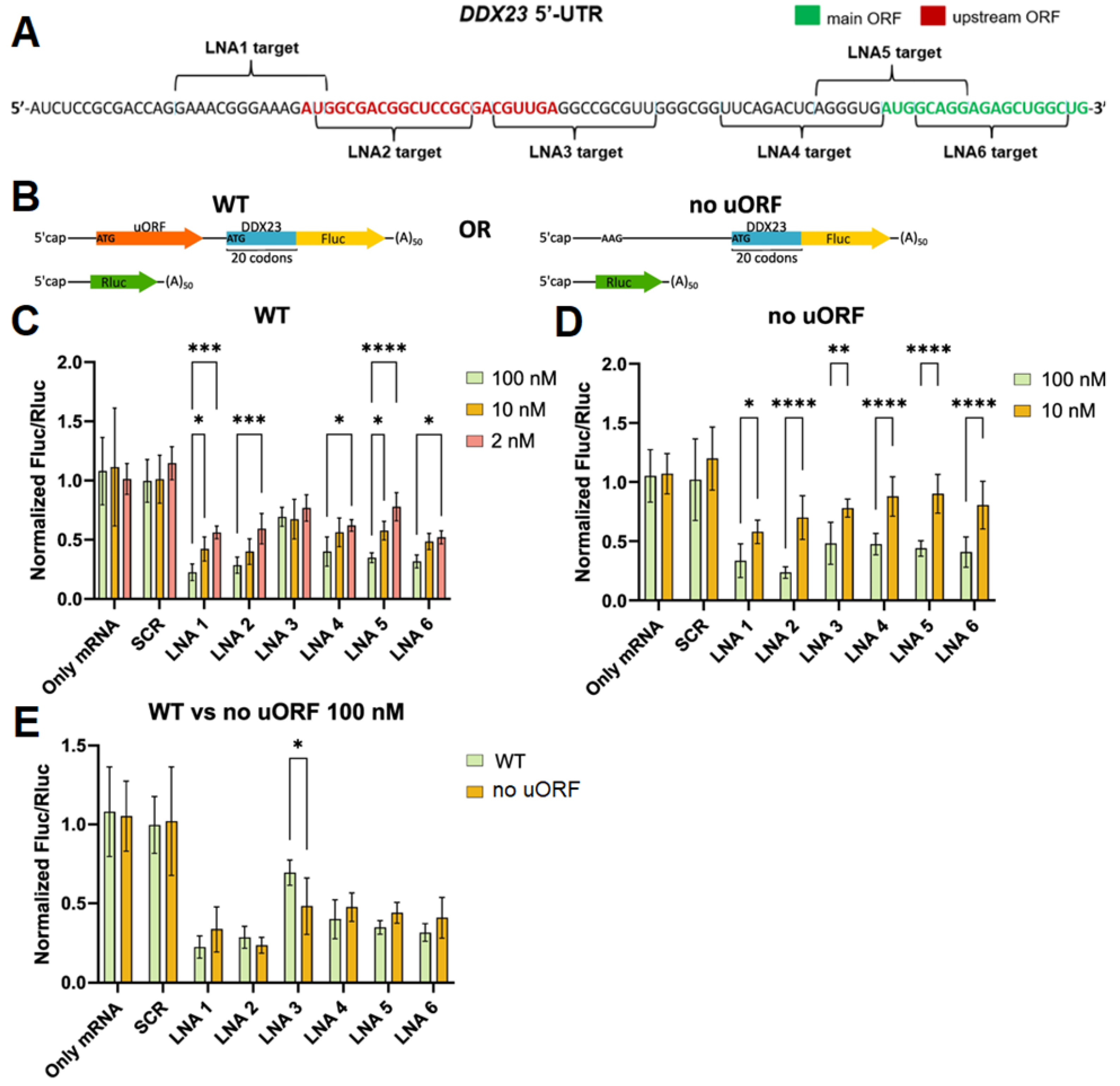

2.3 Evaluation of LNA-based ASOs Activity in DDX23 5’ UTR Translation Control

3. Materials and Methods

3.1 Oligonucleotide Synthesis and Sample Preparation

3.2 Thioflavin T (ThT) Light-Up Assays

3.3 Circular Dichroism (CD) and UV Spectroscopy and Melting

3.4 NMR Experiments

3.5 Cell Culturing

3.6 Plasmid Constructs

3.7 Transfection

3.8 In vitro Transcription

3.9 Luciferase Assay

3.10 Visualization of Ribosome Profiling

3.11 Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| CDS | Coding sequence |

| CH2Cl2 | Methylene chloride |

| CH3CN | Acetonitrile |

| CPG | Controlled pore glass |

| DDX23 | DEAD-box helicase 23 |

| DEPC | Diethyl pyrocarbonate |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| dsRNA | Double-stranded RNA |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| HF | Hydrofluoric acid |

| LNA | Locked nucleic acid |

| NMP | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDS | Pyridostatin |

| PIC | Pre-initiation complex |

| ppm | Parts per million |

| rG4 | RNA G-quadruplex |

| SCR | Scramble |

| rTBA15 | RNA 15-nt thrombin binding aptamer |

| TBDMS | tert-Butyldimethylsilyl |

| TDS | Thermal difference spectra |

| TEA | Triethylamine |

| ThT | Thioflavin T |

| Tm | Melting temperature |

| uORF | Upstream open reading frame |

| 5′ UTR | 5′ Untranslated region |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Cordin, O.; Beggs, J.D. RNA Helicases in Splicing. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teigelkamp, S.; Mundt, C.; Achsel, T.; Will, C.L.; Lührmann, R. The Human U5 snRNP-Specific 100-kD Protein Is an RS Domain-Containing, Putative RNA Helicase with Significant Homology to the Yeast Splicing Factor Prp28p. RNA N. Y. N 1997, 3, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, D.; Adams, D.W.; Hoffman, N.; Safaric Tepes, P.; Wee, T.-L.; Cifani, P.; Joshua-Tor, L.; Krainer, A.R. SRSF1 Interactome Determined by Proximity Labeling Reveals Direct Interaction with Spliceosomal RNA Helicase DDX23. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2322974121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhara, S.C.; Carvalho, S.; Grosso, A.R.; Gallego-Paez, L.M.; Carmo-Fonseca, M.; de Almeida, S.F. Transcription Dynamics Prevent RNA-Mediated Genomic Instability through SRPK2-Dependent DDX23 Phosphorylation. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Cao, Y.; Ling, T.; Li, P.; Wu, S.; Peng, D.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, A.; et al. DDX23, an Evolutionary Conserved dsRNA Sensor, Participates in Innate Antiviral Responses by Pairing With TRIF or MAVS. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.W.; Han, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, M.; Jin, Y.; Zhi, X.; Guan, J.; Sun, S.; Guo, H. The DDX23 Negatively Regulates Translation and Replication of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus and Is Degraded by 3C Proteinase. Viruses 2020, 12, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, A.; Vera-Estrella, R.; Barkla, B.J.; Méndez, E.; Arias, C.F. Identification of Host Cell Factors Associated with Astrovirus Replication in Caco-2 Cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10359–10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Qiu, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, Q.; Ma, X.; Song, K.; Kong, B. Splicing Factor DDX23, Transcriptionally Activated by E2F1, Promotes Ovarian Cancer Progression by Regulating FOXM1. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 749144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Jin, H.; Wu, L. DDX23-Linc00630-HDAC1 Axis Activates the Notch Pathway to Promote Metastasis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38937–38949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Lai, S.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Weng, S. METTL3 Enhances Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Progression and Gemcitabine Resistance through Modifying DDX23 mRNA N6 Adenosine Methylation. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Park, G.; Lee, J.E.; Choi, E.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, T.-H.; Park, N.; Jin, X.; Jung, J.-E.; Shin, D.; et al. DEAD-Box RNA Helicase DDX23 Modulates Glioma Malignancy via Elevating miR-21 Biogenesis. Brain 2015, 138, 2553–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, W.; Bird, L.M.; Heron, D.; Keren, B.; Ramachandra, D.; Thiffault, I.; Del Viso, F.; Amudhavalli, S.; Engleman, K.; Parenti, I.; et al. Syndromic Neurodevelopmental Disorder Associated with de Novo Variants in DDX23. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2021, 185, 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; He, J.; Gou, H.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Zhu, Y.-M. WGCNA Combined with GSVA to Explore Biomarkers of Refractory Neocortical Epilepsy. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 13, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asberger, J.; Erbes, T.; Jaeger, M.; Rücker, G.; Nöthling, C.; Ritter, A.; Berner, K.; Juhasz-Böss, I.; Hirschfeld, M. Endoxifen and Fulvestrant Regulate Estrogen-Receptor α and Related DEADbox Proteins. Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooke, S.T.; Baker, B.F.; Crooke, R.M.; Liang, X.-H. Antisense Technology: An Overview and Prospectus. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhuri, K.; Bechtold, C.; Quijano, E.; Pham, H.; Gupta, A.; Vikram, A.; Bahal, R. Antisense Oligonucleotides: An Emerging Area in Drug Discovery and Development. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boiziau, C.; Kurfurst, R.; Cazenave, C.; Roig, V.; Thuong, N.T.; Toulmé, J.-J. Inhibition of Translation Initiation by Antisense Oligonucleotides via an RNase-H Independent Mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Nichols, J.G.; Hsu, C.-W.; Vickers, T.A.; Crooke, S.T. mRNA Levels Can Be Reduced by Antisense Oligonucleotides via No-Go Decay Pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 6900–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Dheur, S.; Nielsen, P.E.; Gryaznov, S.; Van Aerschot, A.; Herdewijn, P.; Hélène, C.; Saison-Behmoaras, T.E. Antisense PNA Tridecamers Targeted to the Coding Region of Ha-Ras mRNA Arrest Polypeptide Chain Elongation. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 294, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Shen, W.; Sun, H.; Migawa, M.T.; Vickers, T.A.; Crooke, S.T. Translation Efficiency of mRNAs Is Increased by Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting Upstream Open Reading Frames. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Sun, H.; Shen, W.; Wang, S.; Yao, J.; Migawa, M.T.; Bui, H.-H.; Damle, S.S.; Riney, S.; Graham, M.J.; et al. Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting Translation Inhibitory Elements in 5′ UTRs Can Selectively Increase Protein Levels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 9528–9546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braasch, D.A.; Corey, D.R. Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA): Fine-Tuning the Recognition of DNA and RNA. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTigue, P.M.; Peterson, R.J.; Kahn, J.D. Sequence-Dependent Thermodynamic Parameters for Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA)−DNA Duplex Formation. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 5388–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadoni, E.; De Paepe, L.; Manicardi, A.; Madder, A. Beyond Small Molecules: Targeting G-Quadruplex Structures with Oligonucleotides and Their Analogues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6638–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, D.; Spiegel, J.; Zyner, K.; Tannahill, D.; Balasubramanian, S. The Regulation and Functions of DNA and RNA G-Quadruplexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamzeeva, P.N.; Alferova, V.A.; Korshun, V.A.; Varizhuk, A.M.; Aralov, A.V. 5’-UTR G-Quadruplex-Mediated Translation Regulation in Eukaryotes: Current Understanding and Methodological Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, P.; Cara, A.D. Hairpin RNA: A Secondary Structure of Primary Importance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, P.; Marsico, G.; Herdy, B.; Ghanbarian, A.; Portella, G.; Balasubramanian, S. RNA G-Quadruplexes at Upstream Open Reading Frames Cause DHX36- and DHX9-Dependent Translation of Human mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Qi, Y.; Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Ding, Y. G4Atlas: A Comprehensive Transcriptome-Wide G-Quadruplex Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D126–D134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.R.; Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Neuböck, R.; Hofacker, I.L. The Vienna RNA Websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofacker, I.L. Vienna RNA Secondary Structure Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3429–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.; Pujar, S.; Loveland, J.E.; Astashyn, A.; Bennett, R.; Berry, A.; Cox, E.; Davidson, C.; Ermolaeva, O.; Farrell, C.M.; et al. A Joint NCBI and EMBL-EBI Transcript Set for Clinical Genomics and Research. Nature 2022, 604, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikin, O.; D’Antonio, L.; Bagga, P.S. QGRS Mapper: A Web-Based Server for Predicting G-Quadruplexes in Nucleotide Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Y.; Lejault, P.; Chevrier, S.; Boidot, R.; Robertson, A.G.; Wong, J.M.Y.; Monchaud, D. Transcriptome-Wide Identification of Transient RNA G-Quadruplexes in Human Cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.U.; Bartel, D.P. RNA G-Quadruplexes Are Globally Unfolded in Eukaryotic Cells and Depleted in Bacteria. Science 2016, 353, aaf5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, Q.; Xiang, J.; Yang, Q.; Sun, H.; Guan, A.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Shi, Y.; et al. Thioflavin T as an Efficient Fluorescence Sensor for Selective Recognition of RNA G-Quadruplexes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, S.O.; Baleeva, N.S.; Zatsepin, T.S.; Myasnyanko, I.N.; Turaev, A.V.; Pozmogova, G.E.; Khrulev, A.A.; Varizhuk, A.M.; Baranov, M.S.; Aralov, A.V. Short Duplex Module Coupled to G-Quadruplexes Increases Fluorescence of Synthetic GFP Chromophore Analogues. Sensors 2020, 20, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Peng, P.; Wang, H.; Shi, L.; Li, T. Thioflavin T Binds Dimeric Parallel-Stranded GA-Containing Non-G-Quadruplex DNAs: A General Approach to Lighting up Double-Stranded Scaffolds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 12080–12089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bugaut, A.; Huppert, J.L.; Balasubramanian, S. An RNA G-Quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the NRAS Proto-Oncogene Modulates Translation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacht, A.V.; Seifert, O.; Menger, M.; Schütze, T.; Arora, A.; Konthur, Z.; Neubauer, P.; Wagner, A.; Weise, C.; Kurreck, J. Identification and Characterization of RNA Guanine-Quadruplex Binding Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6630–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pany, S.P.P.; Sapra, M.; Sharma, J.; Dhamodharan, V.; Patankar, S.; Pradeepkumar, P.I. Presence of Potential G-Quadruplex RNA-Forming Motifs at the 5′-UTR of PP2Acα mRNA Repress Translation. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 2955–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harpster, C.; Boyle, E.; Musier-Forsyth, K.; Kankia, B. HIV-1 Genomic RNA U3 Region Forms a Stable Quadruplex-Hairpin Structure. Biophys. Chem. 2021, 272, 106567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugaut, A.; Murat, P.; Balasubramanian, S. An RNA Hairpin to G-Quadruplex Conformational Transition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19953–19956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, M.; Sigurdsson, S.; Tomac, S.; Sen, S.; Rozners, E.; Sjöberg, B.-M.; Strömberg, R.; Gräslund, A. A Synthetic Model for Triple-Helical Domains in Self-Splicing Group I Introns Studied by Ultraviolet and Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 4678–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauca-Diaz, A.M.; Jung Choi, Y.; Resendiz, M.J.E. Biophysical Properties and Thermal Stability of Oligonucleotides of RNA Containing 7,8-dihydro-8-hydroxyadenosine. Biopolymers 2015, 103, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P.; Shukla, C.; Arya, A.; Sharma, S.; Datta, B. G-Quadruplexes in MTOR and Induction of Autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G-Quadruplex Nucleic Acids: Methods and Protocols; Yang, D., Lin, C., Eds.; Methods in molecular biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4939-9666-7.

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Mirihana Arachchilage, G.; Basu, S. Metal Cations in G-Quadruplex Folding and Stability. Front. Chem. 2016, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.M.; Gudanis, D.; Coyne, S.M.; Gdaniec, Z.; Ivanov, P. Identification of Functional Tetramolecular RNA G-Quadruplexes Derived from Transfer RNAs. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Müller, S.; Yeoman, J.A.; Trentesaux, C.; Riou, J.-F.; Balasubramanian, S. A Novel Small Molecule That Alters Shelterin Integrity and Triggers a DNA-Damage Response at Telomeres. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 15758–15759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergny, J.-L. Thermal Difference Spectra: A Specific Signature for Nucleic Acid Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergny, J.-L.; Lacroix, L. UV Melting of G-Quadruplexes. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2009, Chapter 17, 17.1.1-17.1.15. [CrossRef]

- Varani, G.; McClain, W.H. The G·U Wobble Base Pair: A Fundamental Building Block of RNA Structure Crucial to RNA Function in Diverse Biological Systems. EMBO Rep. 2000, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.C.; Freeborn, B.; Moore, P.B.; Steitz, T.A. Metals, Motifs, and Recognition in the Crystal Structure of a 5S rRNA Domain. Cell 1997, 91, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, N.; Nissen, P.; Hansen, J.; Moore, P.B.; Steitz, T.A. The Complete Atomic Structure of the Large Ribosomal Subunit at 2.4 Å Resolution. Science 2000, 289, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, D.S.; Kotkowiak, W.; Kierzek, R.; Pasternak, A. Hybridization Properties of RNA Containing 8-Methoxyguanosine and 8-Benzyloxyguanosine. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Shah, V.; Datta, B. Assessing G4-Binding Ligands In Vitro and in Cellulo Using Dimeric Carbocyanine Dye Displacement Assay. Molecules 2021, 26, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Iaccarino, N.; Abdelhamid, M.A.S.; Brancaccio, D.; Garzarella, E.U.; Di Porzio, A.; Novellino, E.; Waller, Z.A.E.; Pagano, B.; Amato, J.; et al. Common G-Quadruplex Binding Agents Found to Interact With i-Motif-Forming DNA: Unexpected Multi-Target-Directed Compounds. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micura, R.; Höbartner, C. On Secondary Structure Rearrangements and Equilibria of Small RNAs. ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiniry, S.J.; Michel, A.M.; Baranov, P.V. The GWIPS-viz Browser. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2018, 62, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shin, B.-S.; Alvarado, C.; Kim, J.-R.; Bohlen, J.; Dever, T.E.; Puglisi, J.D. Rapid 40S Scanning and Its Regulation by mRNA Structure during Eukaryotic Translation Initiation. Cell 2022, 185, 4474–4487.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedaya, O.M.; Venkata Subbaiah, K.C.; Jiang, F.; Xie, L.H.; Wu, J.; Khor, E.-S.; Zhu, M.; Mathews, D.H.; Proschel, C.; Yao, P. Secondary Structures That Regulate mRNA Translation Provide Insights for ASO-Mediated Modulation of Cardiac Hypertrophy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braasch, D.A. Antisense Inhibition of Gene Expression in Cells by Oligonucleotides Incorporating Locked Nucleic Acids: Effect of mRNA Target Sequence and Chimera Design. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 5160–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-H.; Nichols, J.G.; Sun, H.; Crooke, S.T. Translation Can Affect the Antisense Activity of RNase H1-Dependent Oligonucleotides Targeting mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QIAGENE Tm Prediction GeneGlob Available online: https://geneglobe.qiagen.com/us/tools/tm-prediction.

- Xiang, Y.; Huang, W.; Tan, L.; Chen, T.; He, Y.; Irving, P.S.; Weeks, K.M.; Zhang, Q.C.; Dong, X. Pervasive Downstream RNA Hairpins Dynamically Dictate Start-Codon Selection. Nature 2023, 621, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. The scanning model for translation: An update. J. Cell. Biol. 1989, 108, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Sequence 5’→3’ | Target region |

LNA/RNA duplex Tm, °C |

GC, % |

| LNA1 | CATCTTTCCCGTTC | Upstream region to the uORF start codon | 134 | 50 |

| LNA2 | GCGGAGCCGTCGCCA | Downstream region to the uORF start codon | 98 | 80 |

| LNA3 | AACGCGGCCTCAACG | 5’ segment of hair_short and the uORF stop codon | 82 | 67 |

| LNA4 | CACCCTGAGTCTGAA | 3’ segment of hair_short and 5’ segment of G3 | 120 | 53 |

| LNA5 | TCCTGCCATCACCCT | Central region of G3 and the CDS start codon | 123 | 60 |

| LNA6 | AGCCAGCTCTCCTGC | 3’ segment of G3 | 104 | 67 |

| SCR | CATACGTCTATACGCT | Negative control | - | 44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).