Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DNA Constructs

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Flow Cytometry and FACS

2.4. mRNA Collection and Analyses

2.5. Targeted Modification of the CTSD Locus

2.6. CatD Activity Assays

3. Results

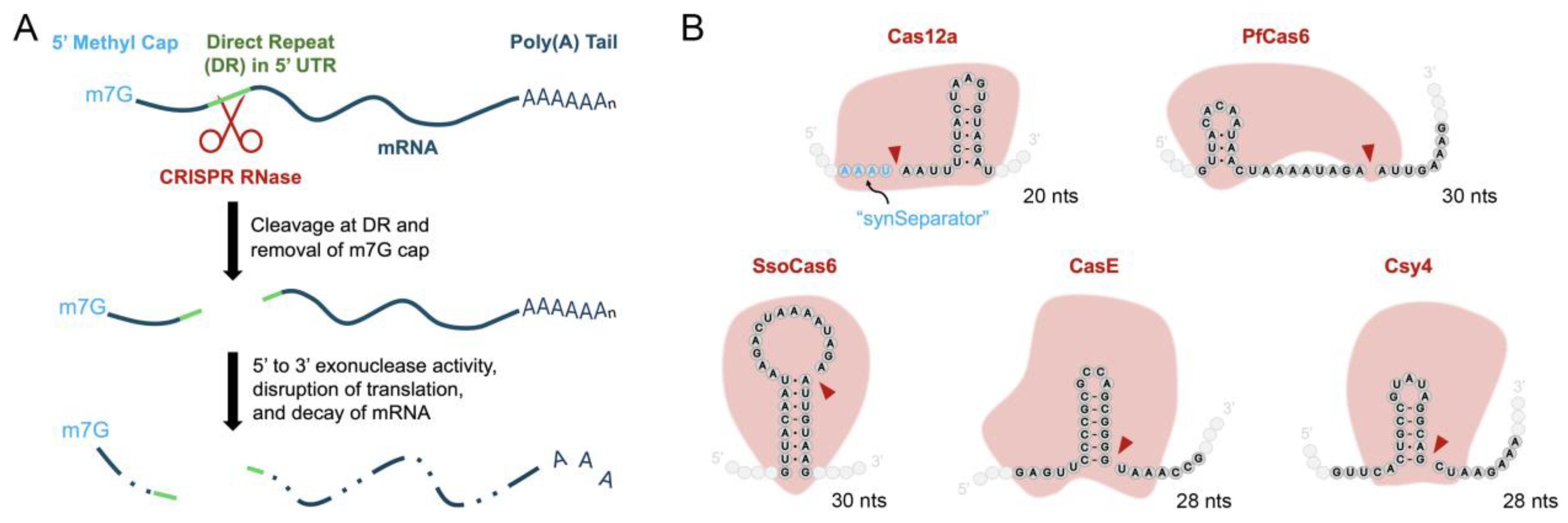

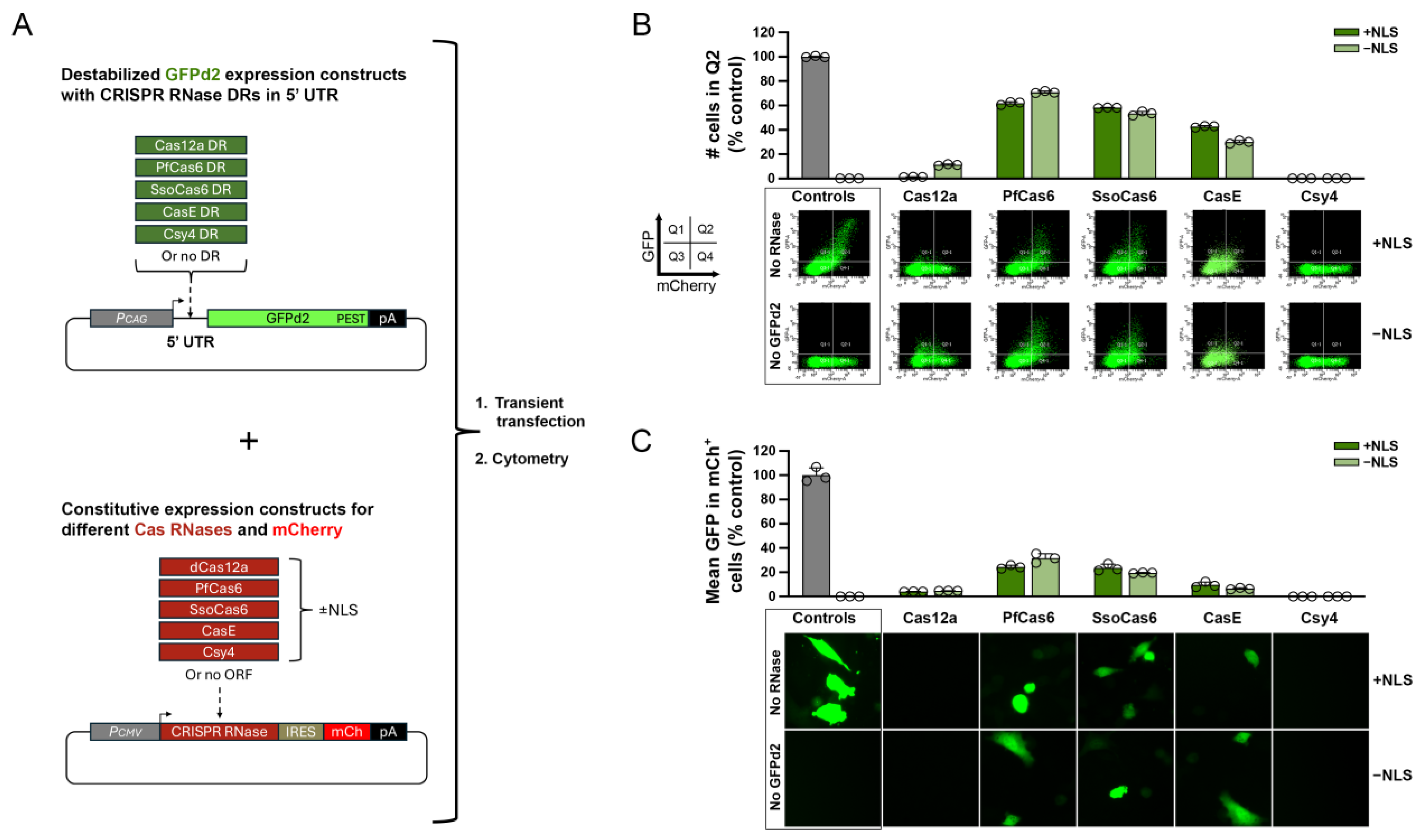

3.1. Selection and Screening of Candidate Cas RNases for 5' DREDGE

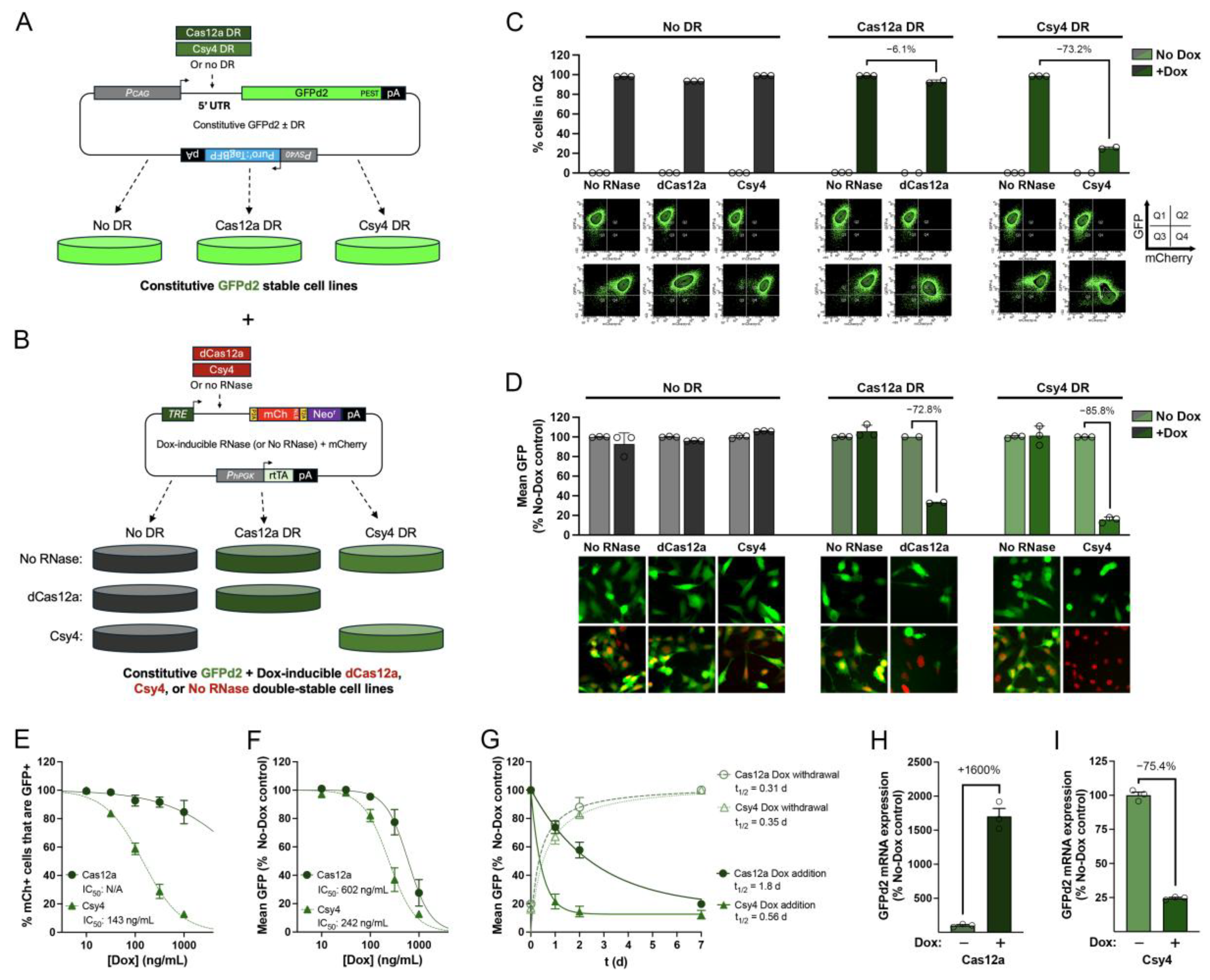

3.2. Dox-Regulatable Gene Expression by 5′ DREDGE Using dCas12a and Csy4

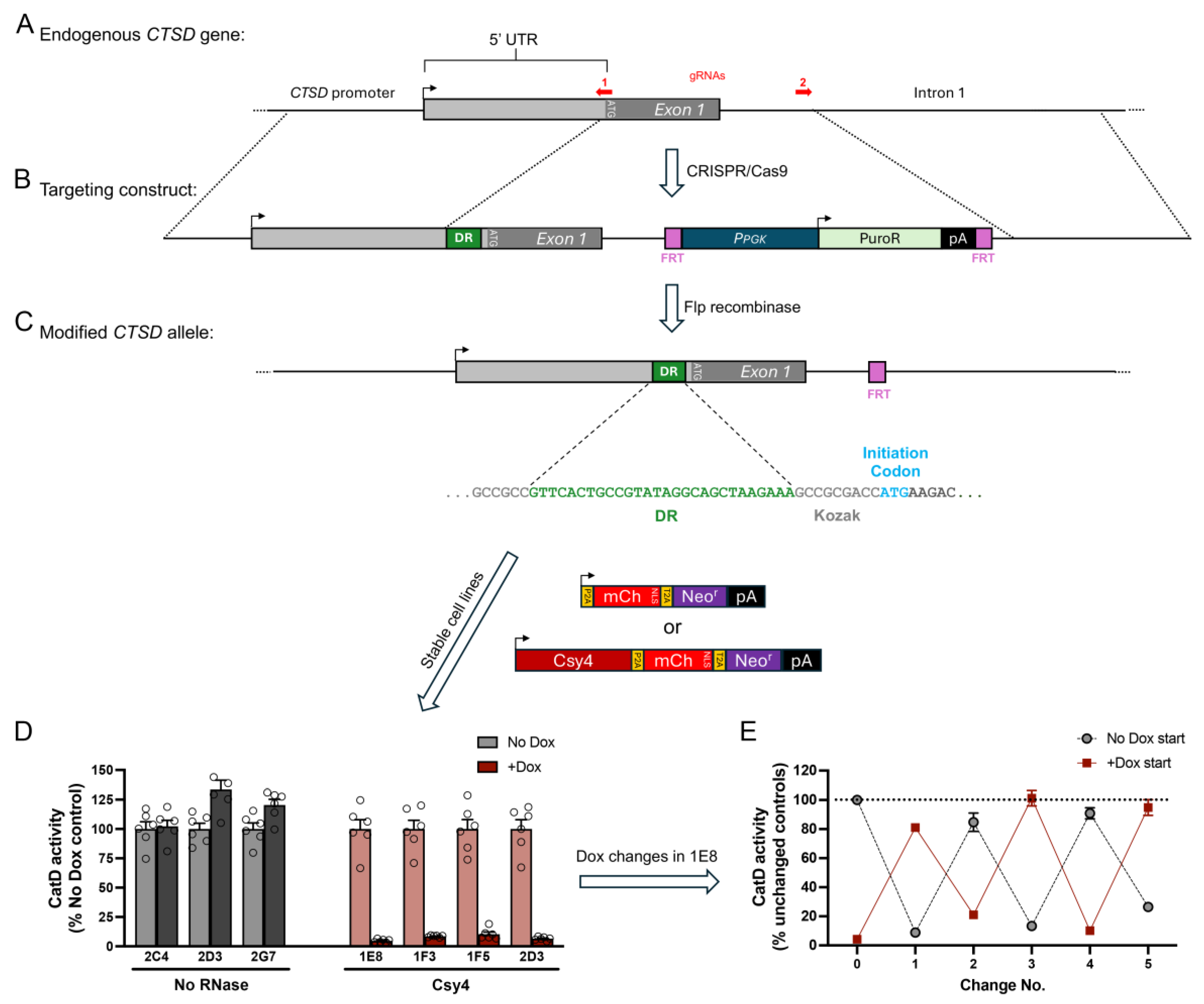

3.3. Dox-Regulatable Downregulation of the Endogenous Gene, CTSD, by 5′ DREDGE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charpentier, E., H. Richter, J. van der Oost, and M. F. White. "Biogenesis pathways of RNA guides in archaeal and bacterial CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity." FEMS Microbiol Rev 39, no. 3 (2015): 428-41. [CrossRef]

- Hochstrasser, M. L. , and J. A. Doudna. "Cutting it close: CRISPR-associated endoribonuclease structure and function." Trends Biochem Sci 40, no. 1 (2015): 58-66. [CrossRef]

- Wiedenheft, B., S. H. Sternberg, and J. A. Doudna. "RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea." Nature 482, no. 7385 (2012): 331-8. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, S. J., H. M. Terron, L. A. Burgard, D. S. Maranan, D. D. Butler, A. Wiseman, F. M. LaFerla, S. Lane, and M. A. Leissring. "Targeted control of gene expression using CRISPR-associated endoribonucleases." Cells 14, no. 7 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Y. , and A. B. Shyu. "Mechanisms of deadenylation-dependent decay." Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2, no. 2 (2011): 167-83. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. Y., J. Bian, A. E. Davis, P. Liu, H. R. Kempton, X. Zhang, A. Chemparathy, B. Gu, X. Lin, D. A. Rane, X. Xu, R. M. Jamiolkowski, Y. Hu, S. Wang, and L. S. Qi. "Multiplexed genome regulation in vivo with hyper-efficient Cas12a." Nat Cell Biol 24, no. 4 (2022): 590-600. [CrossRef]

- Avila-Bonilla, R. G. , and S. Macias. "The molecular language of RNA 5' ends: guardians of RNA identity and immunity." RNA 30, no. 4 (2024): 327-36. [CrossRef]

- Borden, K. L. B. , and L. Volpon. "The diversity, plasticity, and adaptability of cap-dependent translation initiation and the associated machinery." RNA Biol 17, no. 9 (2020): 1239-51. [CrossRef]

- Mars, J. C., B. Culjkovic-Kraljacic, and K. L. B. Borden. "eIF4E orchestrates mRNA processing, RNA export and translation to modify specific protein production." Nucleus 15, no. 1 (2024): 2360196. [CrossRef]

- He, F. , and A. Jacobson. "Eukaryotic mRNA decapping factors: molecular mechanisms and activity." FEBS J 290, no. 21 (2023): 5057-85. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S. , and A. G. McLennan. "The complex enzymology of mRNA decapping: Enzymes of four classes cleave pyrophosphate bonds." Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 10, no. 1 (2019): e1511. [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, S. H., R. E. Haurwitz, and J. A. Doudna. "Mechanism of substrate selection by a highly specific CRISPR endoribonuclease." RNA 18, no. 4 (2012): 661-72. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T. , and C. L. Cepko. "Controlled expression of transgenes introduced by in vivo electroporation." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, no. 3 (2007): 1027-32. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T. R., G. Dhamdhere, Y. Liu, X. Lin, L. Goudy, L. Zeng, A. Chemparathy, S. Chmura, N. S. Heaton, R. Debs, T. Pande, D. Endy, M. F. La Russa, D. B. Lewis, and L. S. Qi. "Development of CRISPR as an Antiviral Strategy to Combat SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza." Cell 181, no. 4 (2020): 865-76 e12. [CrossRef]

- Loew, R., N. Heinz, M. Hampf, H. Bujard, and M. Gossen. "Improved Tet-responsive promoters with minimized background expression." BMC Biotechnol 10 (2010): 81. [CrossRef]

- Suire, C. N., S. O. Abdul-Hay, T. Sahara, D. Kang, M. K. Brizuela, P. Saftig, D. W. Dickson, T. L. Rosenberry, and M. A. Leissring. "Cathepsin D regulates cerebral Abeta42/40 ratios via differential degradation of Abeta42 and Abeta40." Alzheimers Res Ther 12, no. 1 (2020): 80. [CrossRef]

- Terron, H. M., D. S. Maranan, L. A. Burgard, F. M. LaFerla, S. Lane, and M. A. Leissring. "A dual-function "TRE-Lox" system for genetic deletion or reversible, titratable, and near-complete downregulation of cathepsin D." Int J Mol Sci 24, no. 7 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, J. P., A. R. Rios, L. Wu, and L. S. Qi. "Enhanced Cas12a multi-gene regulation using a CRISPR array separator." Elife 10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Campa, C. C., N. R. Weisbach, A. J. Santinha, D. Incarnato, and R. J. Platt. "Multiplexed genome engineering by Cas12a and CRISPR arrays encoded on single transcripts." Nat Methods 16, no. 9 (2019): 887-93. [CrossRef]

- Terron, H. M., S. J. Parikh, S. O. Abdul-Hay, T. Sahara, D. Kang, D. W. Dickson, P. Saftig, F. M. LaFerla, S. Lane, and M. A. Leissring. "Prominent tauopathy and intracellular beta-amyloid accumulation triggered by genetic deletion of cathepsin D: implications for Alzheimer disease pathogenesis." Alzheimers Res Ther 16, no. 1 (2024): 70. [CrossRef]

- Suire, C. N. , and M. A. Leissring. "Cathepsin D: A candidate link between amyloid beta-protein and tauopathy in Alzheimer disease." J Exp Neurol 2, no. 1 (2021): 10-15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., X. Lin, W. Xiang, Y. Chen, Y. Zhao, L. Huang, and L. Liu. "DNA target binding-induced pre-crRNA processing in type II and V CRISPR-Cas systems." Nucleic Acids Res 53, no. 3 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Dong, D., K. Ren, X. Qiu, J. Zheng, M. Guo, X. Guan, H. Liu, N. Li, B. Zhang, D. Yang, C. Ma, S. Wang, D. Wu, Y. Ma, S. Fan, J. Wang, N. Gao, and Z. Huang. "The crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with CRISPR RNA." Nature 532, no. 7600 (2016): 522-6. [CrossRef]

- Sinan, S., N. M. Appleby, C. W. Chou, I. J. Finkelstein, and R. Russell. "Kinetic dissection of pre-crRNA binding and processing by CRISPR-Cas12a." RNA 30, no. 10 (2024): 1345-55. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J., H. Hayder, Y. Zayed, and C. Peng. "Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation." Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9 (2018): 402. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).