1. Introduction

More than 100 chemical modifications of the four canonical nucleotides, adenosine (A), cytosine (C), guanosine (G), and uracil (U) have been identified in RNA molecules. All modifications are posttranscriptionally incorporated by a diverse set of chemical reactions including deaminations, isomerizations, glycosylations, thiolations, methylations, and transglycosylations [

1] and affect not only A, C, G, and U, but also create hypermodifications such as queuosine or wybutosine from already modified nucleotides [

1,

2]. The most diverse collection of modifications has been found in rRNAs and tRNAs [

3].

With the advent of cost-effective high throughput sequencing, it has become possible to assess modified nucleotides on a genome- and transcriptome-wide scale. The common basis of a broad class of techniques is the use of reverse transcription (RT) that terminates just before certain modifications (e.g., for 1-methyladenosine (m

1A) and 1-methylguanosine (m

1G)) and/or misincorporates nucleotides at very high rates when encountering other modifications (e.g., inosine (I), m

1A, and 6-methyladenosine (m

6A)). The resulting cDNA is then subjected to high-throughput sequencing, mapped to a reference genome, and computationally analyzed for strong arrests of primer extension (RT-stops) and position-specific mismatch profiles [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. These events constitute a RT signature which varies depending on the modification type and the used reverse transcriptase [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. While some modifications directly affect reverse transcriptase activity or fidelity, other modifications require a preceding chemical treatment to become visible. The treatments can lead to a conversion of the modified nucleotide or induce a block of the primer extension by the reverse transcriptase. As a result, the read-out of the chemically treated nucleotide is different compared to the untreated control. Thus, these modifications can directly be detected by comparing treated versus untreated samples. For example, pseudouridine (Ψ) becomes detectable after treatment with carbodiimides which acylate one of the nitrogen positions of the base, resulting in Ψ-1-cyclohexyl-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide (CMC) adducts that block RT [

9,

10,

11]. The saturated pyrimidine ring of dihydrouridine (D) can be opened by sodium borohydride (NaBH

4) or under alkaline conditions. As a result, base pairing is impeded, leading to straightforward detection by RT signatures. In addition, 7-methyl-guanosine (m

7G) reduction by NaBH

4 leads to a depurination in RNA followed by the cleavage of the RNA chain by β-elimination [

12].

Mainly, tRNA modifications act as checkpoints for tRNA identity as well as integrity, regulate translation, modulate the structural stability, and ensure the correct folding of the tRNA molecule [

13]. They are further involved in structural fine-tuning of local elements and rapidly adapt tRNAs to environmental changes, such as stress and temperature [

14,

15]. Most chemical modifications modulate the tRNA structure in terms of stability and flexibility [

16]. m

1A at position 9 in the human mitochondrial tRNA

Lys, for example, disrupts a Watson-Crick base pair A9-U64 that stabilizes a non-functional rod-like structure and forces the tRNA to adopt the typical cloverleaf secondary structure and the L-shaped three-dimensional functional conformation [

17]. Other modifications in the D- and TΨC- loop, carrying D and Ψ, respectively, are involved in tertiary base pairs and enhance the folding of the transcript into the L-shape [

18,

19]. Pseudouridine, in particular, contributes to the overall stability of tRNA structures with the help of water-mediated bridging interactions between modified bases and the RNA backbone [

20,

21]. Dihydrouridine, on the other hand, frequently found in the D-arm, is the only non-planar base and thus reduces stacking interactions, conferring a certain flexibility to tRNAs [

22].

Initial studies indicate that the control of flexibility versus rigidity indeed plays a role in the temperature adaptation of microorganisms. Accordingly, high levels of D are found in psychrophilic organisms, where flexibility in macromolecules is interpreted as a frequent strategy for cold adaptation [

23,

24]. In psychrophilic Archaea, tRNAs contain a higher amount of D modifications than their thermophilic counterparts [

1,

25]. Pseudouridine levels in bacteria can also change as a response to growth temperature [

26,

27]. However, these analyses investigated the overall change of certain modifications, but did not analyze changes at the resolution of individual tRNA sequences. Hence, it is an interesting question as to how modification levels at individual positions in the tRNAs are adjusted in response to temperature changes to keep these molecules functional.

To investigate a possible correlation of temperature and posttranscriptional modifications in bacterial tRNAs, four closely related Bacillales with different growth temperature profiles (Bacillus subtilis (mesophilic), Exiguobacterium sibiricum, Planococcus halocryophilus (both psychrophilic), and Geobacillus stearothermophilus (thermophilic)) were used as model organisms. These strains were cultured at temperature ranges from 10-70°C, including the individual optimal growth temperatures as well as the minimum and maximum temperatures feasible in the laboratory. Together, this allowed a screen for temperature-dependent, short- term changes in the tRNA modification pattern within the organism and long-term evolutionary adaptation to their particular habitat.

3. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether variations in tRNA modifications represent an adaptation of bacteria to different growth temperatures. To address this inquiry, we cultivated four closely related Bacillales species

P. halocryophilus,

E. sibiricum,

B. subtilis, and

G. stearothermophilus under three different temperature conditions (minimal, optimal, and maximal). We combined an RNA seq approach with chemical pre-treatment of the tRNA samples and developed an analysis strategy that allows for systematic profiling of D, s

4U, and m

7G (NaBH

4-treatment) as well as Ψ (CMCT-treatment) modifications in the transcriptome at single-nucleotide resolution. Based on our statistical quantification of the data, we detected a variety of RT-stop sites which are significantly and strongly enriched in the treated samples compared to the untreated control. A significant challenge was that the tRNA treatments were designed to detect up to three different modifications in the resulting reads. In contrast to gene expression analysis, where statistical robustness and performance can be increased by aggregating reads from an entire gene, measurements of tRNA modifications comprise only single nucleotides [

40]. Another challenge was to distinguish true modification sites from noise. Such RT-stop sites occur since the reverse transcriptase is sensitive to certain structural features of the RNA template [

41,

42] or to other modifications which are not specifically enriched by the treatment. Complex processing of RNA, genomic misalignments of sequencing reads, and technical errors of the sequencing platform contribute to incorrect signals. We assumed that - due to the chemical tRNA treatments - the modified sites result in a considerably higher signal over noise ratio. The use of a specifically adapted FC cutoff is, therefore, suitable. In addition, low read coverage at specific tRNA positions may result in overestimation of the ratio of RT-stops to the total number of reads. In both treatments, these signals are particularly frequent in the TΨC-arm, D-arm, as well as the 5’-acceptor stem of tRNAs. In addition, we observed that the SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase exhibited an increasing tendency to incorporate incorrect bases in the 3’-range and terminate prematurely, leading to background noise in the data. Such signals were filtered out by only considering RT-stop sites that exhibited a minimum number and percentage of RT-stops at the respective position. We were not able to completely remove the background noise without accepting an increased false negative rate by more stringent parameter settings. As expected, an approximately equal numbers of type I FPs were observed using the

mim-tRNAseq tool. However, such FP RT-stop sites showed variability across different bacterial species and growth temperatures, indicating a lack of clear patterns. As ignoring the impact of FP detection likely leads to data misinterpretation, a careful consideration and mitigation of background noise and its incorporation into threshold determination may enhance the accuracy and reliability of tRNA modification profiling studies. To determine the optimal cutoffs, we classified RT-stop sites as TP modifications or FPs based on established information from the RNA modification database MODOMICS [

28] and relevant scientific literature [

3,

5,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. It is important to note that this classification was not specific to individual tRNAs, as our focus was on less well-characterized bacteria. Due to the lack of comprehensive characterization of the investigated bacteria, this method is limited in its ability to detect unexpected modifications that may occur during a temperature shift, as the true positive positions of modified tRNA were identified based on existing knowledge.Irrespective of potential false negatives at unexpected sites, our data provide insights in temperature dependent changes at those sites where we observe modifications with high confidence.

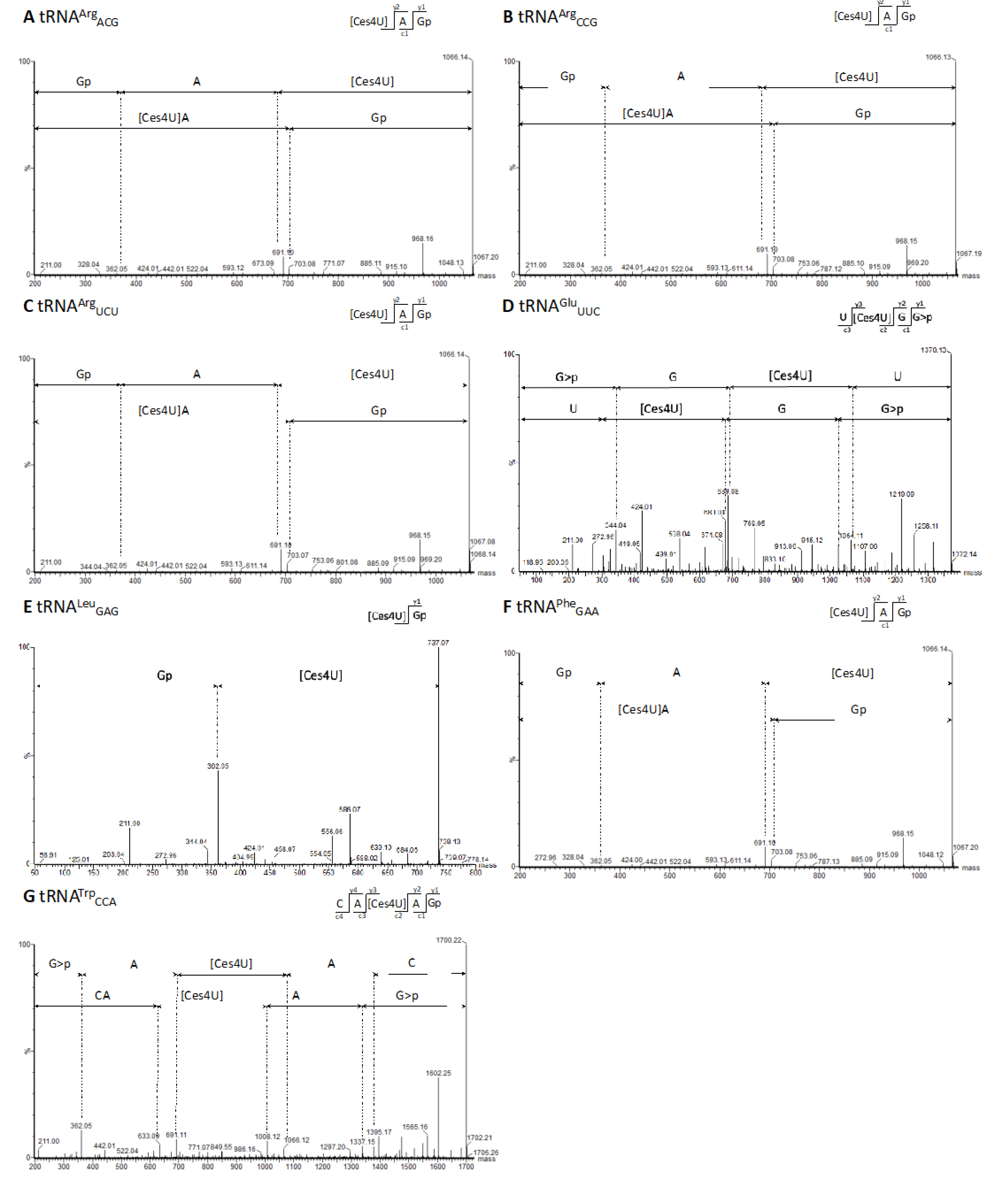

Upon initial examination of the NaBH

4-treated RNA seq data, we identified RT-enriched sites at position U8 in several tRNAs, suggesting a specific modification rather than random noise. It is noteworthy that s

4U modifications are typically associated with U8 in bacteria and archea [

28,

36,

37,

38]. Our mass spectrometry-based analysis (

Figure 4) validated the presence of s

4U8 modifications in

G. stearothermophilus. Since we detected both MS/MS signals and enriched RT stops in the same set of 8 tRNAs, we hypothesize that we could also identify s

4U8 modifications with the NaBH

4-treated data.

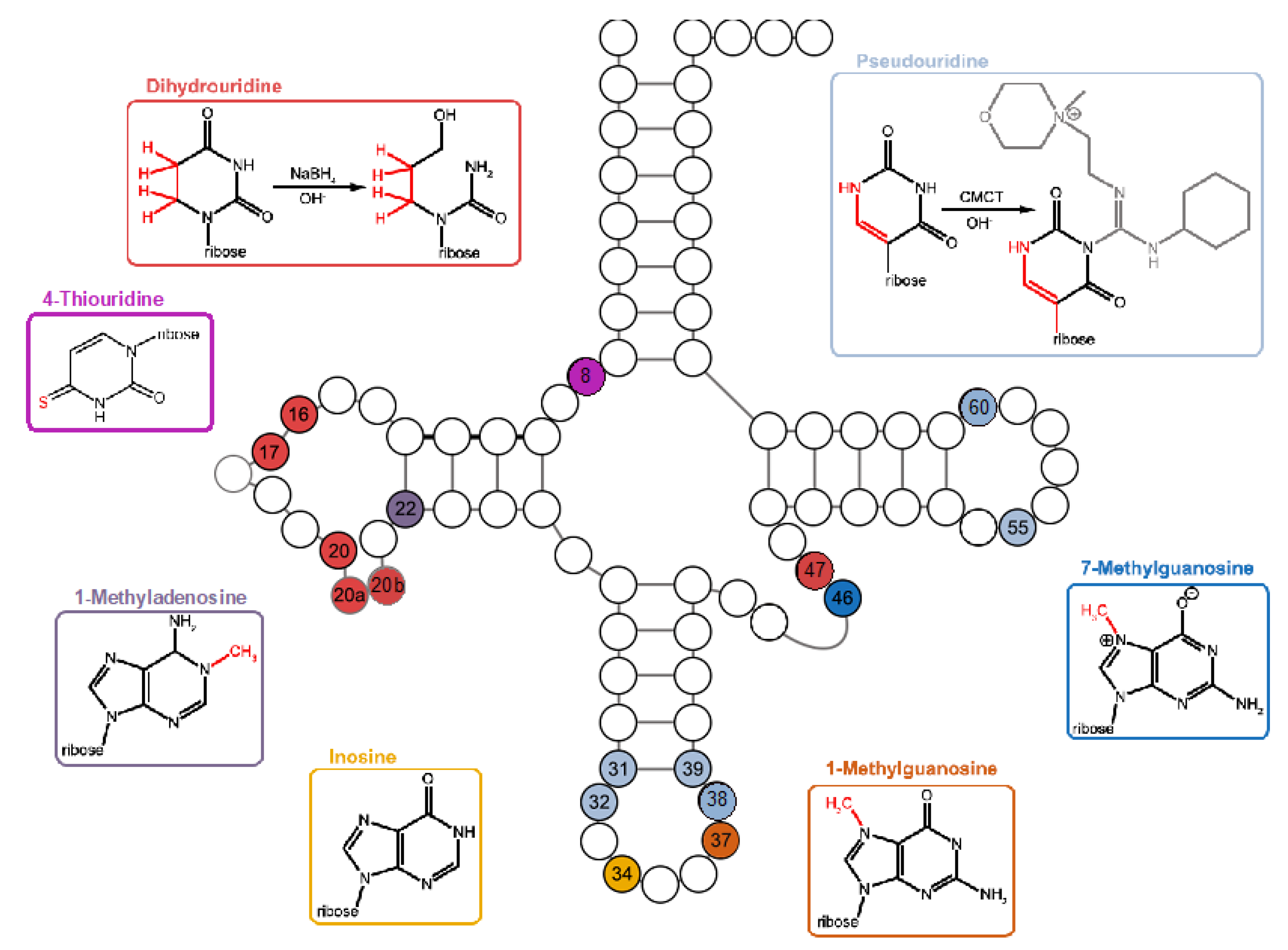

In addition to identifying the general tRNA modification patterns in the investigated bacteria, our study aimed to detect temperature-induced differences in tRNA modifications.The analysis revealed numerous strong RT-stop sites and base misincorporation accumulations in the mapping profiles, indicating the presence of various modifications such as s

4U, D, m

1A, m

7G, m

1G, I, and Ψ (

Figure 5). Despite most of these modifications occurred in the tRNA pool of the four species, the number of each modified tRNA position varied in the individual isoacceptor families. This provided a unique modification profile for each bacterium, even though they are closely related (

Supplementary Figure S11). It is important to note that the absence of certain modifications does not necessarily imply their non-existence but could be attributed to weaker expression levels or exclusion by our stringent cutoff criteria. For example, we did not observe strong RT-stops for Ψ38 in tRNAs of

B. subtilis, despite previous reports of its presence [

12,

43]. Further, m

1G37, involved in frame shift suppression [

44] was only found in

P. halocryophilus, while it is also described in

B. subtilis [

35]. Further validation methods such as deletion of RT-stop signatures by enzymatic demethylation of m

1G by AlkB-type enzymes [

45] or MS/MS analysis [

46,

47] could help confirm the presence of these modifications. Similarly, slight variations in the number of modified tRNA clusters within a species across different cultivation temperatures should not be overinterpreted as the variations may reflect differences in modification intensity rather than distinct modifications. Thus, our cutoff criteria allowed us to infer the presence of tRNA modifications with minimal intensity levels. In addition, strong RT-stop sites at position U54 are observed in numerous tRNAs across the bacterial species. In bacteria, only m

5U54 (ribothymidine) modifications have been documented [

3,

28,

35,

48]. Unfortunately, it is not known whether a CMCT treatment can effectively detect such modifications, posing challenges in definitively classifying the RT-stop sites without further validation. However, the presence of robust RT-stop sites at position U54 in almost all tRNAs aligns with the listing of m

5U modifications in the MODOMICS database, reinforcing the likelihood that this type of modification has been detected in this context.

The analysis of temperature-dependent tRNA modifications revealed intriguing patterns in psychrophilic and mesophilic bacteria, with consistent trends observed in these organisms. Interestingly, the thermophilic bacterium

G. stearothermophilus exhibited an increase in the number of tRNAs modified at specific positions as temperatures increased. This observation suggests a temperature-dependent regulation of tRNA modifications. Of particular interest is the significantly higher occurrence of s

4U8 modifications in

G. stearothermophilus compared to non-thermophilic bacteria. Previous studies have highlighted the role of s

4U modifications in stabilizing tRNA structures and influencing translation efficiency [

15,

49,

50]. It could be further demonstrated that s

4U8 is conserved in bacterial and archaeal tRNAs and plays a role as a UV protective [

15,

50]. The increased presence of s

4U8 in

G. stearothermophilus could be interpreted as an adaptive strategy to maintain tRNA stability and functionality under extreme high-temperature conditions, potentially serving as a factor for the thermotolerance of this organism. Furthermore, the presence of the Ψ55 modification has been identified as a control mechanism for thermal adaptation of tRNA functionality [

15,

51]. The presence of Ψ55 limits the incorporation of modifications that provide thermal stability, whereas its absence promotes the addition of such modifications, enhancing thermal stability. Originally identified as a modification that stabilizes tRNA structure, Ψ55 can also enhance flexibility and functionality of tRNAs at lower temperatures. While the investigated psychrophilic and mesophilic Bacillales did not show significant trends for Ψ55 modifications concerning temperature differences,

G. stearothermophilus exhibited a substantial increase in Ψ55 from 9 modified tRNA clusters at minimal growth temperature to 29 modifications at maximal growth temperature. This suggests that Ψ55 may play a crucial role in the thermal adaptation of

G. stearothermophilus by modulating stability and flexibility of tRNAs at varying temperatures.

It has been reported that some psychrophilic microorganisms have a higher dihydrouridine content in their tRNAs compared to mesophilic and thermophilic organisms environments [

15,

22,

24,

25,

52]. This modification represents the only base that adopts a chair conformation. All other bases in nucleic acids are strictly planar and readily form base-stacking interactions that stabilize and rigidify the surrounding structure. Due to its non-planar structure, dihydrouridine interferes with base stacking and leads to an increased local flexibility in tRNAs, a feature that may represent an important adaptation to cold environments [

15,

22,

24,

25,

52]. However, we cannot fully confirm this hypothesis, as we do not observe significant differences between psychrophilic and mesophilic bacteria. Nevertheless, the number of D modifications in tRNAs from psychrophilic and mesophilic bacteria is higher than in the thermophilic bacterium.

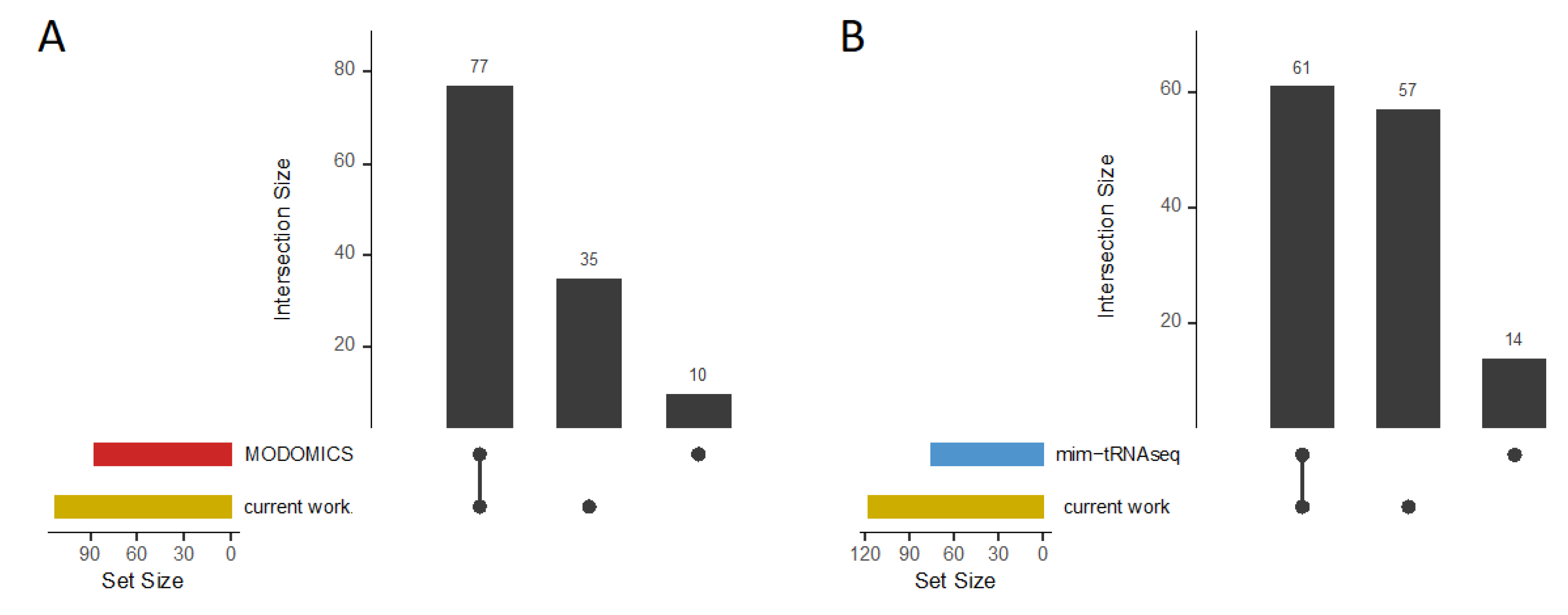

Only a few tools have already been published for the detection of tRNA modifications using treatment-based RT-stops in sequencing mapping profiles, for example see [

39,

53]. To compare our findings with those of an already established tool for such analyses, we utilized the

mim-tRNAseq tool. The

mim-tRNAseq methodology relies on prior knowledge to classify true positives, like the approach adopted in our analyses. Our method demonstrated high effectiveness, as we were able to identify over 81% of the modifications (grouped by amino acid families and their encoded anticodons) found by

mim-tRNAseq in

B. subtilis, along with an additional 57 modifications (

Figure 6B). Furthermore, we successfully identified 89% of the specific modifications listed in the MODOMICS database for

G. stearothermophilus and

B. subtilis, as well as detecting an additional 35 modifications for specific tRNA genes (

Figure 6A). This comprehensive coverage of known modifications highlights the robustness and reliability of the obtained data at single-base resolution. The ability to detect both previously known and novel modifications underscores the potential of our method for advancing the understanding of tRNA biology.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivation of Bacteria

B. subtilis strain DSM 10, E. sibiricum strain DSM 17290, P. halocryophilus strain DSM 24742, and G. stearothermophilus strain DSM 22 were purchased at the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ) and grown in the corresponding recommended liquid medium. Cultivation was carried out at various growth temperatures in a culture shaker at 180 rpm and a volume of 50-100 ml. Cell growth was photometrically monitored and cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 3,500 g once they had reached the mean log phase. According to organism and growth temperature, OD600 was between 0.31 and 0.84.

4.2. Isolation of Total RNA and Small RNA Enrichment

Bacterial cell pellets were resuspended in TRIzolTM. Cell disruption was performed using a FastPrep homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, Germany) for 40 s at 6 m/s, followed by incubation at room temperature for 5 min. 200 μl chloroform was added, mixed for 15 s and incubated for 3 min at room temperature. After centrifugation for 15 min at 12,000 g and 4°C, the supernatant was transferred to a sterile reaction tube, mixed with an identical volume of isopropanol, and incubated on ice for 15 min. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation and washed twice with 1 ml ethanol (70 %). After air drying at 30°C, the total RNA was dissolved in 200 μl sterile water. For small RNA enrichment, the total RNA preparation was mixed with 1/10 volume of 5 M NaCl and 50 % PEG 8,000, and incubated for 30 min at -20°C. After centrifugation for 30 min at 10,000 g and 4°C, the procedure was repeated with the supernatant. The resulting solution was mixed with 3 volumes of ethanol and incubated overnight at -20°C. Small RNAs were precipitated by centrifugation and resuspended in water.

4.3. NaBH4-Treatment for the Detection of Dihydrouridine and 7-Methylguanosine

Treatment of the small RNA fraction was done as described [

54]. 2-4 µg small RNA were adjusted with water to a volume of 50 µl, and 5 µl of a freshly prepared NaBH

4 solution (100 mg/ml in 0.01 N KOH) was added. The mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 µl 0.01 N acetic acid followed by ethanol precipitation. The RNA was resuspended in sterile water and kept at -20°C until use.

4.4. CMCT-Treatment for the Detection of Pseudouridine

The procedure is based on the protocol as described [

12] with slight modifications. Briefly, 2-4 μg small RNA were mixed with 30 μl of freshly prepared 1-cyclohexyl-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluene sulfonate (CMCT) solution (165 mM CMCT, 50 mM Bicine, pH 8.0, 7 M urea, 4mM EDTA) or CMCT buffer (solution without CMCT) as control and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by ethanol precipitation in the presence of 1 µg glycogen. The RNA pellet was resuspended in 40 µl 50 mM Na

2CO

3 solution (pH 10.3) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After another ethanol precipitation, the pellet was dissolved in sterile water.

4.5. Adenylation of Adapter Oligonucleotide and Ligation to Small RNA Samples

500 pmol of a 3’-terminally blocked adapter oligonucleotide (5’-pTGGAATTCTCGGGTGCCAAGG-amino-C7-3’) was mixed with 50 pmol of recombinantly expressed and purified TS2126 RNA ligase (CircLigase) in 20 μl adenylation buffer (50 mM MOPS, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl

2) containing 2.5 mM MnCl

2, 1 mM DTT, and 50 µM ATP and incubated for 2 h at 60°C as previously described [

55,

56]. The reaction was stopped by heat inactivation at 80°C for 10 min. Adenylated adapter was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and resuspended in water at a concentration of 20 µM. For ligation to the 3’-end of the prepared small RNA, 20 pmol of the adenylated adapter were incubated with 10 pmol sRNA sample in 10 µl 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl

2, 1 mM DTT, 0.4 mM ATP, 20% PEG 8,000 and 14 pmol recombinantly prepared T4 RNA ligase 2, truncated KQ (T4Rnl2KQ). After incubation at 25°C for 20 h, the reaction was stopped by heat inactivation at 65°C for 20 min.

4.6. Reverse Transcription

10 pmol phosphorylated RT primer (spiked with 1 pmol of 5’-

32P-labeled RT primer for monitoring) were added to the adapter-ligated small RNA sample. Reverse transcription was performed with SuperScript IV according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 μl 5 N NaOH and incubation at 95°C for 3 min. The solution was neutralized by adding 1 μl 5 N HCl. 8 μl 3x RNA loading buffer were added to the mixtures. Reaction products were separated on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, visualized by autoradiography, cut out using a sterile blade and isolated according to Roth et al. [

57]. As the RT primer (

Supplemental Table S1) was used for circularization of the complementary DNA (cDNA), it contained two 18-atom hexa-ethylene glycol spacers (Sp18) to avoid rolling circle amplification during PCR [

58,

59,

60]. In addition, the primer contained a binding site for the Illumina small RNA library primer for preparation of the sequencing library.

4.7. Circularization, Amplification and Indexing of cDNA

Gel-purified cDNA was incubated at 60°C for 2 h in the presence of 17 pmol TS2126 RNA ligase (CircLigase) in a volume of 20 µl adenylation buffer supplemented with 5 mM MnCl

2, 20 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM ATP. The ligation reaction was stopped by heat inactivation at 80°C for 10 min. The individual sequencing libraries were prepared by PCR according to the Illumina TruSeq smallRNA library instructions. 5 μl of circularized cDNA were added to a reaction volume of 50 μl containing 1x Phusion HF buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM primer containing Illumina P5 sequence, 0.5 μM index primer, and 1 U of Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Each reaction was split and amplified in 10 to 12 cycles. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the concentration was determined photometrically. P5-containing primer and primer containing Illumina P7 sequence are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.8. High Throughput tRNA Sequencing

Single-end RNA sequencing (RNA seq; 1x100 bp) of the cDNA libraries was performed on an Illumina MiSeq device using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3. Three biological replicates were sequenced for the NaBH4- and CMCT-treatment as well as for the corresponding untreated negative control for each bacterium and cultured temperature (in total 36 RNA seq libraries per species).

4.9. Annotation of tRNAs

Cytosolic tRNAs were annotated with

tRNAscan-SE v2.0 [

61] using the default model for bacteria. Obtained tRNA sequences were aligned to the tRNAdb [

36] database using

BLAST v2.4.0 [

62] to fit individual tRNA secondary structure annotation to the corresponding standard tRNA model [

63].

4.10. Mapping of tRNA Reads

To trim adapter sequences and low-quality portions of raw reads,

Cutadapt v1.16 [

64] was applied with a quality cutoff of 25 and a maximum error rate of 0.15. Only reads of 8 to 95 nts length (after trimming of adapter and low-quality bases) were captured. Read mapping and filtering were performed following the best-practice tRNA mapping strategy as described [

65]. In brief, the reads were mapped against a modified target genome in which known tRNA loci were masked and instead intronless tRNA precursor sequences were appended as artificial “chromosomes”. In a first pass, reads displaying specific precursor hallmarks were filtered out. In the second pass, the mature tRNA reads were mapped against mature tRNA sequence clusters which assembled identical tRNAs helping to overcome the multi-copy nature of tRNA genes. Consequently, only uniquely mapped high confidence tRNA reads were used for downstream analyses. The genomes of the four bacteria of the corresponding strain were obtained from the database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [

66].

4.11. Library Normalization

For direct comparisons of control and treated libraries, mapped data were scaled library- and replica-wise. Library-wise normalization was performed by scaling the number of mapped reads for each tRNA cluster position to the total sample number of reads. For replica-wise normalization, the mean value of replicates was calculated for each genomic tRNA position.

4.12. Identification of Significant Base Misincorporation Sites

For detection of tRNA modifications directly visible as accumulation of nucleotide mismatches in mapped reads,

bcftools v1.15.1 [

67] was used. First, the

mpileup command of

bcftools was applied to generate genotype probabilities and read coverage at each genomic position. In a second step, the variants were read out using the

call command with the

-m option to determine rare variants to be included. Variants below the Phred-scaled confidence threshold of 20 and with a coverage of less than 10 reads were excluded.

4.13. Profiling Position-Wise RT-Stops

To identify whether a particular position in a tRNA was significantly altered by chemical treatment, the difference in the number of normalized RT-stop sites in the treated versus untreated libraries was determined. Drawing on the framework used in differential gene expression analysis, a fold change (FC) was calculated at first to differentially quantify effect sizes in RT-stop coverage between treatment and control samples and test for each tRNA position the null hypothesis that there is no significant change between both conditions. The FC for each tRNA and position

n was calculated as

where

Stop+ and

Stop- are the number of RT-stops of the treated and untreated libraries, respectively. In case of modified tRNAs, the RT terminates mostly one position upstream of the modified nucleotide. Thus, values of

and of

pertain to the chemical modification at position

n since the RNA template is read in 3’ to 5’ direction during RT. For between-sample normalization, the untreated library was scaled by the ratio

of total number of reads mapped per tRNAs cluster as scaling factor given by

To handle complications arising from zero counts, a pseudocount of α = 1 was added.

We do not expect or observe substantial overdispersion and hence model the sampling of read ends (caused by RT-stops) as a Poisson process [

68] as second step. Since we expect an enrichment of RT-stops only in the treated samples, the RT-stops derived from the untreated libraries were used to estimate the expected background signal as

. Since expression values are different for individual tRNAs (more precisely for the clusters of tRNAs with nearly Indistinguishable sequences),

is estimated separately for each tRNA cluster. This additionally reduced the influence of potential outliers. Subsequently, the P value for the observation of RT-stops

k (including the pseudo number) was calculated for each tRNA position as follows:

To account for multiple testing, the false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated by applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure [

69]. Only tRNA positions having an FDR adjusted P value of less than 0.01 were considered as significantly modified.

4.14. Choice of Cutoff Values to Reduce Noise

However, regardless of filtering, a large number of presumably spurious noise remain. To further reduce the latter three different parameters were considered:

Fold change (FC): A sufficiently large effect size (FC) is required, i.e., position-specific increase of the chemically introduced RT-stops in treated compared to the untreated library.

Total number of RT-stops: To reduce signals with an overestimated log2 FC, which can arise at positions with a low read coverage even at a few RT-stops.

Percentage of RT-stops: Treatment-based RT-stops have a higher ratio of reads with RT-stops to reads without RT-stops at the corresponding position compared to noise.

Therefore, an appropriate percentage of RT-stops helps to reduce noise. The thresholds were set as follows: FC > 1; total number of RT-stops ≥ 20; and percentage of RT-stops ≥ 2.

4.15. Outcome Comparisons with mim-tRNAseq

For the comparison study,

mim-tRNAseq v1.1.6 [

39] was utilized. A

misinc-thresh threshold (total misincorporation rate at a position in a cluster used to call unannotated modification) of 0.005 was used to reduce noise. All other parameters were set according to default settings.

4.16. MS/MS Analyses

4.16.1. tRNA Cyanoethylation

tRNAs were chemically treated with acrylonitrile to target 4-thiouridine (s

4U) modifications. The acrylonitrile derivatizations (Ces

4U for s

4U) result in a nucleotide mass increase of +53.0 Da, which can be readily detected using mass spectrometry (MS) [

70,

71].

4.16.2. tRNA Isolation by 2D-Gel Electrophoresis

tRNA isoacceptors were isolated using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis as described [

72]. In short, tRNA was briefly heated to 90°C. Then, samples were separated in a first-dimension 12.5% polyacrylamide gel under denaturing conditions containing 1x TBE and 8 M urea, followed by a second dimension under semi-denaturing conditions using a 20% polyacrylamide gel, TBE 1x and 4 M urea at room temperature. Gels were stained with an ethidium bromide solution (10 µg/l) for 10 min. Spots containing isolated tRNA isoacceptors were visualized and excised under UV light (302 nm).

4.16.3. In-Gel RNase Digestion of tRNAs

Gel spots containing tRNAs were desalted by at least eight washes with 100 µl 200 mM NH4AcO and dried under vacuum. For RNase T1 hydrolysis, gel pieces were rehydrated by 20 µl of 0.1 U/µl of RNase T1 or by 20 µL of 0.01 U/µL of RNase A (ThermoFisher Scientific) in 100 mM NH4AcO (pH not adjusted). For RNase U2 treatment, spots were digested by using 50 µl of recombinant RNase U2 at 0.3 ng/µl in 50 mM NH4AcO (pH 5.3) and incubated for 45 min at 65°C. After digestion, supernatants were dried under vacuum.

4.16.4. Nano Liquid Chromatography-MS/MS of RNA Oligonucleotides and Analysis

Pellets containing RNase digestion products were resuspended in 3 µl of milli-Q water and separated on an Acquity peptide BEH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 µm, 75 µm × 200 mm) using a nanoAcquity system (Waters). The analyses were performed with an injection volume of 3 µl. The column was equilibrated in eluant A containing 7.5 mM TEAA (Triethylammonium acetate), 7.0 mM TEA (Triethylammonium) and 200 mM HFIP (hexafluoroisopropanol) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Oligonucleotides were eluted using a gradient from 15% to 35% of eluant B (100% LC/MS Grade methanol) for 2 min followed by an increase of buffer B to 50% in 20 min. MS and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analyses were performed using SYNAPT G2-S (hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer) from Waters Corporation. All experiments were performed in negative mode with a capillary voltage set at 2.6 kV and a sample cone voltage set at 30 V. Source was heated to 130°C. The samples were analyzed over an m/z range from 550 to 1,600 for the full scan, followed by fast data direct acquisition scan (Fast DDA). Collision-induced dissociation (CID) experiments were achieved using Ar. All MS/MS spectra were deconvoluted using MassLynx software (Waters) and manually sequenced by following the y and/or c series (w ions were also used when sequencing was difficult or to confirm a sequence). tRNA identification was done bs comparisons with the genomic sequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., M.M. and P.F.S.; methodology, A.H., J.F., M.M., H.B. and P.F.S.; formal analysis, A.H., C.L., A.L. and P.W.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, A.H., M.M., P.F.S., H.B., J.F., A.L. and P.W.; visualization, A.H., A.L., P.W. and M.M.; supervision, J.F., M.M. and P.F.S.; project administration, M.M. and P.F.S.; funding acquisition, M.M. and P.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

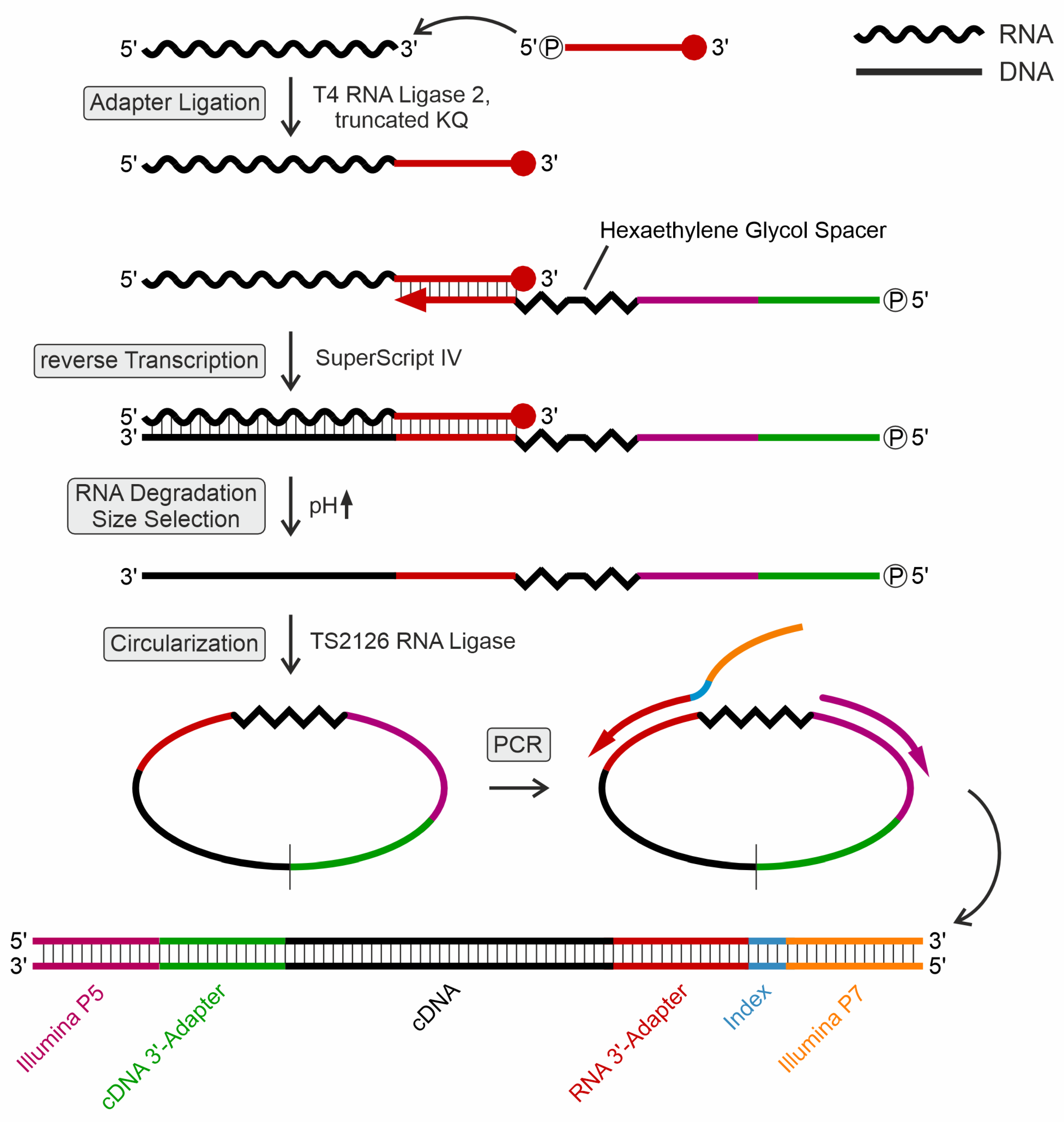

Figure 1.

Schematic workflow for library preparation. First, the 3’-protected RNA adapter was adenylated by TS2126 ligase. Subsequently, T4Rnl2KQ was used to ligate the adapter to the 3’-end of tRNAs. The adapter introduced the index primer binding site and served as a primer binding site for RT. The RT primer carries a hexa-ethylene glycol spacer to prevent rolling circle PCR amplification. After RT, RNA was degraded, and cDNA was size-selected in a polyacrylamide gel. cDNA was then circularized and served as a PCR template. The PCR primers introduced Illumina flow cell sequences P5 and P7, along with one of the 25 6-bp i7 indices used for multiplexing samples on the Illumina sequencing platform.

Figure 1.

Schematic workflow for library preparation. First, the 3’-protected RNA adapter was adenylated by TS2126 ligase. Subsequently, T4Rnl2KQ was used to ligate the adapter to the 3’-end of tRNAs. The adapter introduced the index primer binding site and served as a primer binding site for RT. The RT primer carries a hexa-ethylene glycol spacer to prevent rolling circle PCR amplification. After RT, RNA was degraded, and cDNA was size-selected in a polyacrylamide gel. cDNA was then circularized and served as a PCR template. The PCR primers introduced Illumina flow cell sequences P5 and P7, along with one of the 25 6-bp i7 indices used for multiplexing samples on the Illumina sequencing platform.

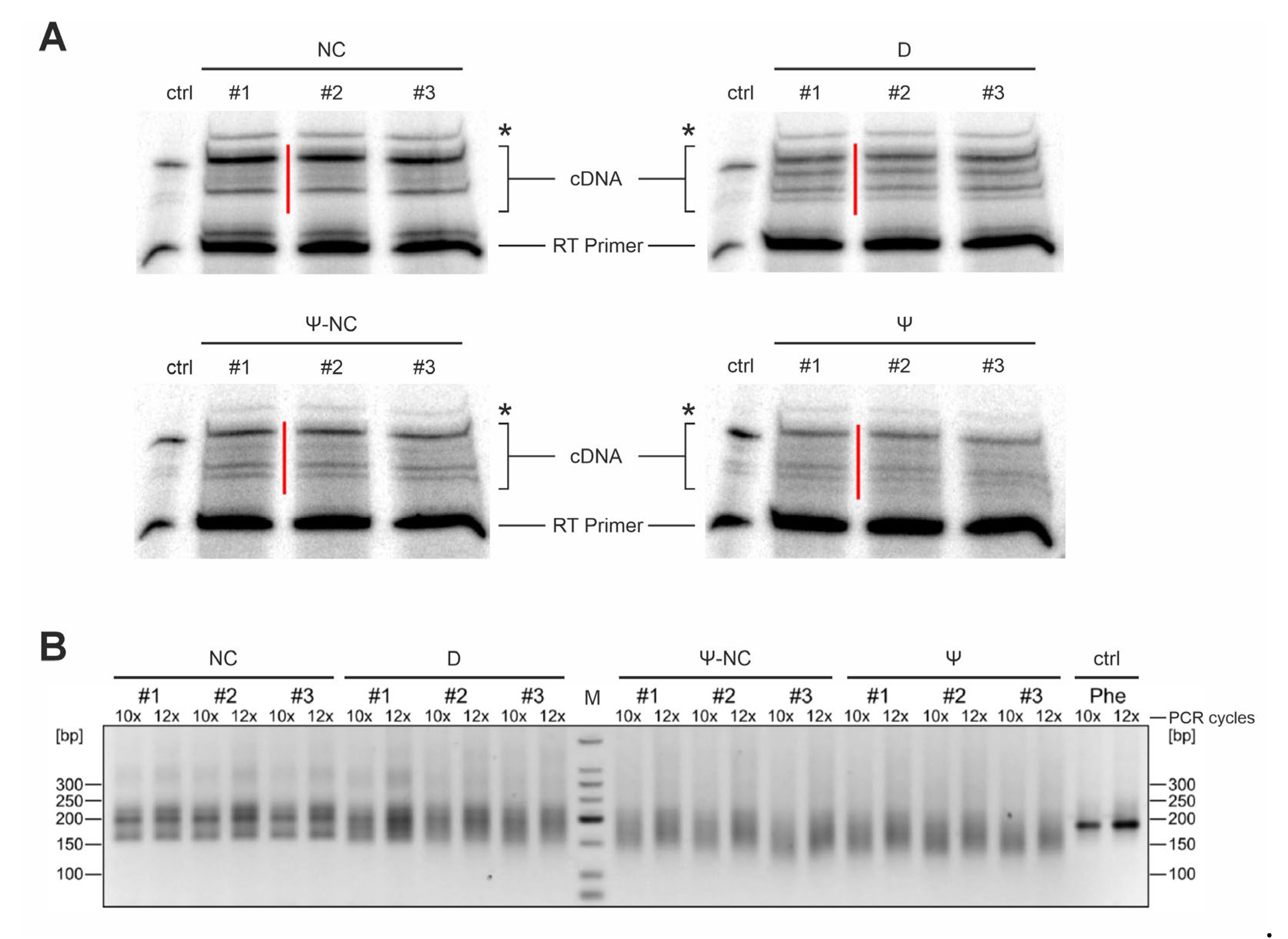

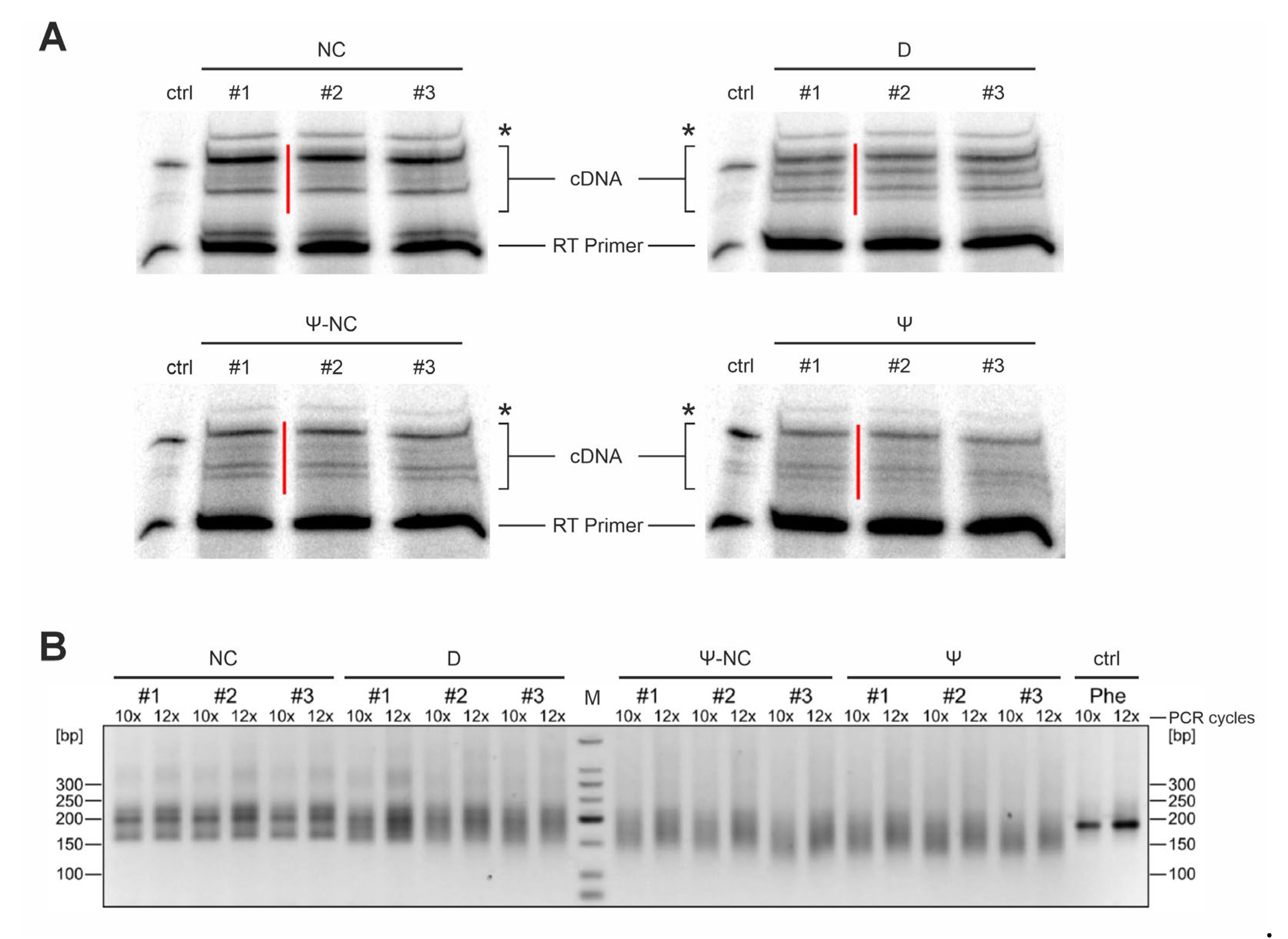

Figure 2.

Library preparation for Illumina RNA sequencing. Libraries for B. subtilis tRNAs at 20°C are shown as a representative example. (A) cDNA synthesis of untreated (negative control, NC), sodium borohydride (NaBH4)-treated (dihydrouridine detection, D), 1-cyclohexyl-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluene sulfonate (CMCT)-treated (pseudouridine detection, Ψ), and CMCT control sample (pseudouridine-negative control, Ψ-NC) were separated on preparative denaturing polyacrylamide gels for subsequent isolation. The red bars indicate the cut-out bands. The asterisk indicates the signal for 5S rRNA (verified by cloning and Sanger sequencing of individual clones). Accordingly, this band was omitted from further analysis. Numbers 1 to 3 represent the three biological replicates. Ctrl, control cDNA synthesis of in vitro transcribed yeast tRNAPhe. (B) Amplified sequencing libraries of the individual tRNA treatments shown above. (PCR cycles (10x or 12x) are indicated. All libraries show the expected smear, while the amplification product of an in vitro transcribed yeast tRNAPhe (control, ctrl, Phe) is represented by a single sharp band.

Figure 2.

Library preparation for Illumina RNA sequencing. Libraries for B. subtilis tRNAs at 20°C are shown as a representative example. (A) cDNA synthesis of untreated (negative control, NC), sodium borohydride (NaBH4)-treated (dihydrouridine detection, D), 1-cyclohexyl-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluene sulfonate (CMCT)-treated (pseudouridine detection, Ψ), and CMCT control sample (pseudouridine-negative control, Ψ-NC) were separated on preparative denaturing polyacrylamide gels for subsequent isolation. The red bars indicate the cut-out bands. The asterisk indicates the signal for 5S rRNA (verified by cloning and Sanger sequencing of individual clones). Accordingly, this band was omitted from further analysis. Numbers 1 to 3 represent the three biological replicates. Ctrl, control cDNA synthesis of in vitro transcribed yeast tRNAPhe. (B) Amplified sequencing libraries of the individual tRNA treatments shown above. (PCR cycles (10x or 12x) are indicated. All libraries show the expected smear, while the amplification product of an in vitro transcribed yeast tRNAPhe (control, ctrl, Phe) is represented by a single sharp band.

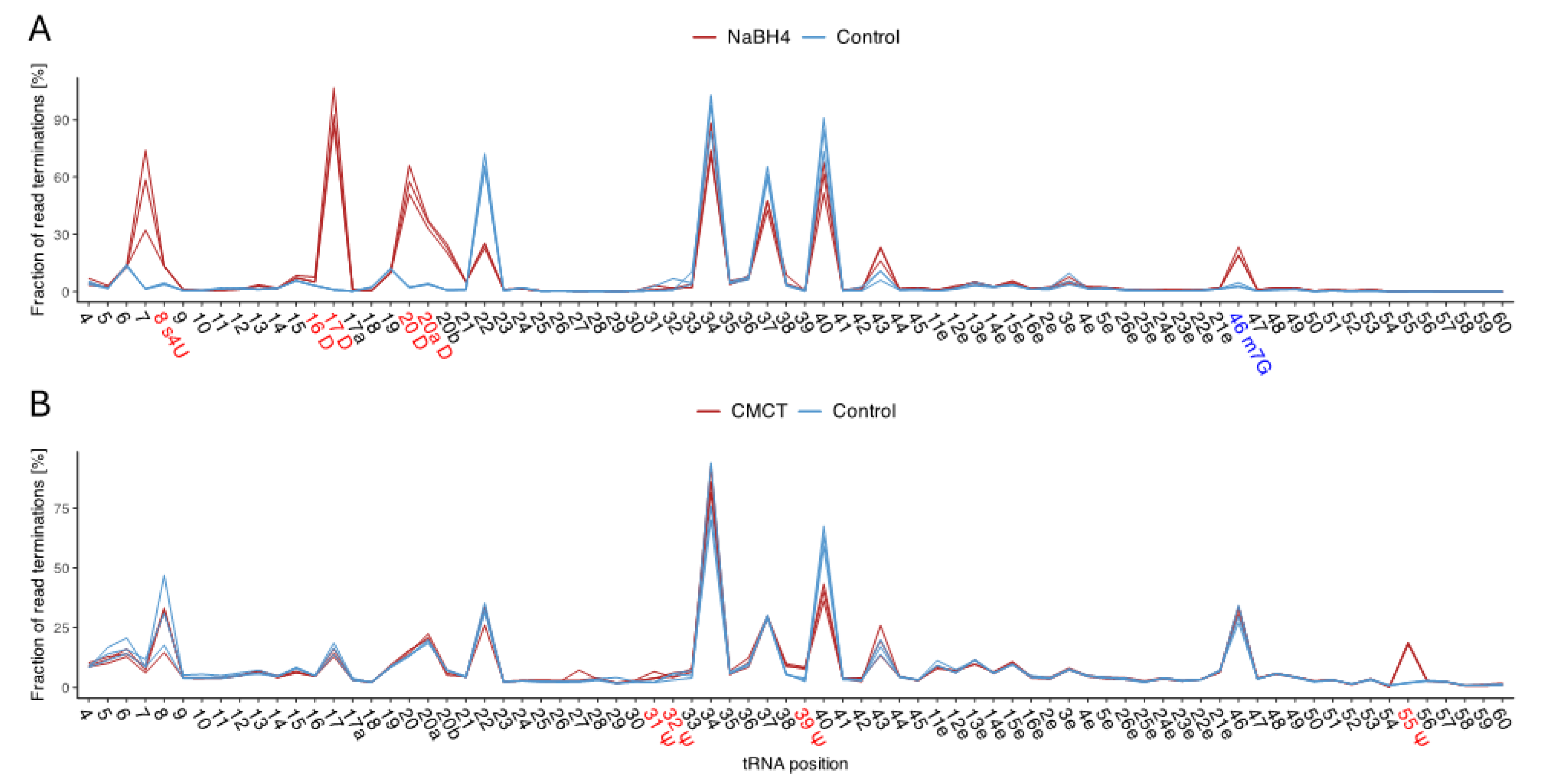

Figure 3.

Quantitative representation of the RNA-seq data for B. subtilis at 20°C. The percentage of reverse transcriptase stops for each tRNA position is provided. The mean value of each tRNA position across all clusters was utilized. The three replicates for the untreated control samples (blue) and the (A) NaBH4- and (B) CMCT-treated RNA-seq data (red) are displayed. Detected modifications are highlighted on the y-axis. High peaks in the treatments and low peaks in the controls indicate an enrichment of RT stops, suggesting modifications. However, modifications occurring in only a few tRNA clusters show a weaker increase in peak height between treatments and controls.

Figure 3.

Quantitative representation of the RNA-seq data for B. subtilis at 20°C. The percentage of reverse transcriptase stops for each tRNA position is provided. The mean value of each tRNA position across all clusters was utilized. The three replicates for the untreated control samples (blue) and the (A) NaBH4- and (B) CMCT-treated RNA-seq data (red) are displayed. Detected modifications are highlighted on the y-axis. High peaks in the treatments and low peaks in the controls indicate an enrichment of RT stops, suggesting modifications. However, modifications occurring in only a few tRNA clusters show a weaker increase in peak height between treatments and controls.

Figure 4.

MS/MS sequencing spectra containing cyanoethylated 4-thiouridine (Ces4U) at tRNA position U8 of G. stearothermophilus. (A) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAArgACG after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.14 z = 1-). (B) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAArgCCG after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.13 z = 1-). (C) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAArgUCU after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.14 z = 1-). (D) MS/MS spectrum U[Ces4U]GG>p of tRNAGluUUC after RNase U2 digestion (m/z 684,57 z = 2-). (E) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]Gp of tRNALeuGAG after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 737,07 z = 1-). (F) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAPheGAA after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.13 z = 1-). (G) MS/MS spectrum CA[Ces4U]AGp of tRNATrpCCA after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 849.61 z = 2-).

Figure 4.

MS/MS sequencing spectra containing cyanoethylated 4-thiouridine (Ces4U) at tRNA position U8 of G. stearothermophilus. (A) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAArgACG after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.14 z = 1-). (B) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAArgCCG after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.13 z = 1-). (C) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAArgUCU after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.14 z = 1-). (D) MS/MS spectrum U[Ces4U]GG>p of tRNAGluUUC after RNase U2 digestion (m/z 684,57 z = 2-). (E) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]Gp of tRNALeuGAG after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 737,07 z = 1-). (F) MS/MS spectrum [Ces4U]AGp of tRNAPheGAA after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 1066.13 z = 1-). (G) MS/MS spectrum CA[Ces4U]AGp of tRNATrpCCA after RNase T1 digestion (m/z 849.61 z = 2-).

Figure 5.

tRNA modification patterns of P. halocryophilus, E. sibiricum, B. subtilis, and G. stearothermophilus. Individual modifications were detected either through accumulations of base-calling errors in the mapping profile or by evaluating read-end distributions of chemically treated RNA seq libraries generated by induced RT-stops. Each of the tRNA modifications illustrated was identified within our analysis in at least one tRNA type of each bacterium, except for 1-methylguanosine at G37, exclusively found in P. halocryophilus; dihydrouridine at U20b, present only in E. sibiricum; and Ψ38, detected solely in P. halocryophilus and E. sibiricum. The modified tRNA positions are color-coded to their corresponding modification.

Figure 5.

tRNA modification patterns of P. halocryophilus, E. sibiricum, B. subtilis, and G. stearothermophilus. Individual modifications were detected either through accumulations of base-calling errors in the mapping profile or by evaluating read-end distributions of chemically treated RNA seq libraries generated by induced RT-stops. Each of the tRNA modifications illustrated was identified within our analysis in at least one tRNA type of each bacterium, except for 1-methylguanosine at G37, exclusively found in P. halocryophilus; dihydrouridine at U20b, present only in E. sibiricum; and Ψ38, detected solely in P. halocryophilus and E. sibiricum. The modified tRNA positions are color-coded to their corresponding modification.

Figure 6.

Validation overview. Upset plots, which visually represent the overlaps and unique elements between different datasets, are used to summarize (A) tRNA modifications (m1A, m7G, s4U, D, and Ψ) of specific tRNA genes from G. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis listed in the MODOMICS database in comparison to the results obtained in this study. (B) Upset plot summarizing potential m7G, s4U, D, and Ψ modifications identified in B. subtilis (30°C) through mim-tRNAseq and our current work.

Figure 6.

Validation overview. Upset plots, which visually represent the overlaps and unique elements between different datasets, are used to summarize (A) tRNA modifications (m1A, m7G, s4U, D, and Ψ) of specific tRNA genes from G. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis listed in the MODOMICS database in comparison to the results obtained in this study. (B) Upset plot summarizing potential m7G, s4U, D, and Ψ modifications identified in B. subtilis (30°C) through mim-tRNAseq and our current work.

Table 1.

Overview of tRNA modifications listed for different bacterial growth temperatures. tRNA cluster numbers of s4U, D, m7G, and Ψ tRNA modifications identified at specific tRNA positions across three measured temperatures in four bacterial strains.

Table 1.

Overview of tRNA modifications listed for different bacterial growth temperatures. tRNA cluster numbers of s4U, D, m7G, and Ψ tRNA modifications identified at specific tRNA positions across three measured temperatures in four bacterial strains.

| |

P. halocryophilus |

E. sibiricum |

B. subtilis |

G. stearothermophilus |

| |

10°C |

20°C |

30°C |

10°C |

20°C |

30°C |

20°C |

30°C |

37°C |

40°C |

55°C |

70°C |

| s4U8 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

- |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

30 |

32 |

24 |

| D16 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

- |

3 |

3 |

| D17 |

14 |

14 |

15 |

15 |

16 |

16 |

20 |

21 |

21 |

1 |

12 |

13 |

| D20 |

17 |

17 |

17 |

25 |

23 |

24 |

21 |

21 |

19 |

6 |

18 |

19 |

| D20a |

12 |

12 |

12 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

2 |

10 |

11 |

| D20b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Ψ31 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

| Ψ32 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

| Ψ38 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Ψ39 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

13 |

14 |

13 |

13 |

13 |

9 |

13 |

14 |

| m7G46 |

17 |

17 |

17 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

22 |

22 |

23 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

| D47 |

- |

3 |

1 |

14 |

4 |

7 |

- |

- |

10 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

| Ψ55 |

24 |

20 |

21 |

20 |

31 |

31 |

27 |

29 |

25 |

9 |

22 |

29 |

| Ψ60 |

- |

5 |

13 |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

12 |

- |

- |

12 |

10 |