Introduction

The origin of mass remains a central enigma in quantum field theories since the inception of modern particle physics [

1,

2]. The concept of mass remains profoundly unsettled within contemporary theoretical frameworks, with quantum chromodynamics (QCD), quantum electrodynamics (QED), and general relativity (GR) each conceptualizing "mass" through disparate mathematical and physical paradigms. In QCD, hadronic mass emerges predominantly from non-perturbative dynamics of the strong interaction, while the Higgs mechanism imparts bare masses to quarks via Yukawa couplings—accounting for only a negligible fraction approximately

of total hadron mass [

3,

4,

5]. In the context of QCD, the dominant contribution to proton rest mass instead arises from confinement energy, strong-interaction binding energy within gluon fields, and spontaneous chiral symmetry breaking [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Despite the combination of lattice QCD and the Higgs mechanism being recognized as the Standard Model explanation for hadronic masses, current lattice QCD simulations—incorporating gluon condensates and energy-momentum tensor form factors—reproduce proton mass values only by fitting parameters to match empirical parton distributions [

11,

12]. While numerically successful in reproducing hadron spectra [

13,

14,

15], these form-factor approaches fail to fundamentally elucidate the

physical origin of mass from first principles, unable to explain why the overwhelming majority of hadronic mass emerges from strong-interaction effects rather than the Higgs condensate. The intrinsically non-linear and non-perturbative nature of QCD renders a complete theoretical and analytical description of the proton’s mass and quark confinement mechanisms elusive, thus necessitating novel theoretical frameworks [

16,

17].

In QED, mass originates through renormalization procedures, wherein the divergent self-energy of charged point particles, such as the electron, undergoes absorption into a redefined physical mass parameter. Dirac initially identified this conceptual challenge in his seminal treatment of the electron’s self-interaction, which led to the formulation of an infinite "bare" mass shielded by vacuum polarization effects [

18,

19]. Contemporary QED formalism attributes the observed mass to the coupling between the electron and vacuum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, which manifest in experimentally verified phenomena such as the Lamb shift and anomalous magnetic moment [

20,

21]. The zero-point energy of the quantized electromagnetic field contributes as a ubiquitous background, modifying fundamental particle properties via loop corrections; nevertheless, the renormalization scheme remains mathematically formal—effectively subtracting infinite quantities without providing substantive physical mechanisms underlying mass generation [

22].

In general relativity, mass receives a fundamentally geometric definition through its influence on the spacetime metric tensor. According to Einstein’s field equations, mass-energy functions as the source term for spacetime curvature, with exact solutions such as the Schwarzschild metric explicitly establishing a mathematical correspondence between spherically symmetric mass distributions and resulting spacetime geometry [

23,

24]. Within this theoretical framework, the gravitational field becomes intrinsically encoded in the spacetime manifold structure, with inertial trajectories following geodesics defined by that curvature. While the equivalence principle successfully unifies gravitational and inertial mass concepts, it provides no explicit

mechanism for mass generation; massive entities are postulated

ab initio, and their gravitational influences are characterized through resultant metric curvature. Stated differently, GR presupposes the stress-energy tensor without specifying its microscopic structure, quantum origin, or the fundamental reason for mass-energy’s existence. This theoretical lacuna underscores the profound incompatibility between general relativity and quantum field theory in providing a coherent explanation for mass at the Planck scale. Considering the proton specifically, its mass effectively confines quarks through residual strong forces—yet interpreting these nuclear confining forces from a gravitational perspective would necessitate curvature magnitudes at femtometer scales that vastly exceed conventional expectations. Consequently, one might reformulate the inquiry, as Wilczek incisively proposed, not "why is gravity so weak?" but rather "why are hadronic masses so small?" [

25]. This conceptual reframing illuminates that the conventional assumption of gravitational weakness may represent a fundamental mischaracterization; instead, a more profound physical mechanism might be actively

screening vacuum energy with such remarkable efficiency that the observed hadronic mass appears inconsequentially small compared to the underlying vacuum energy density.

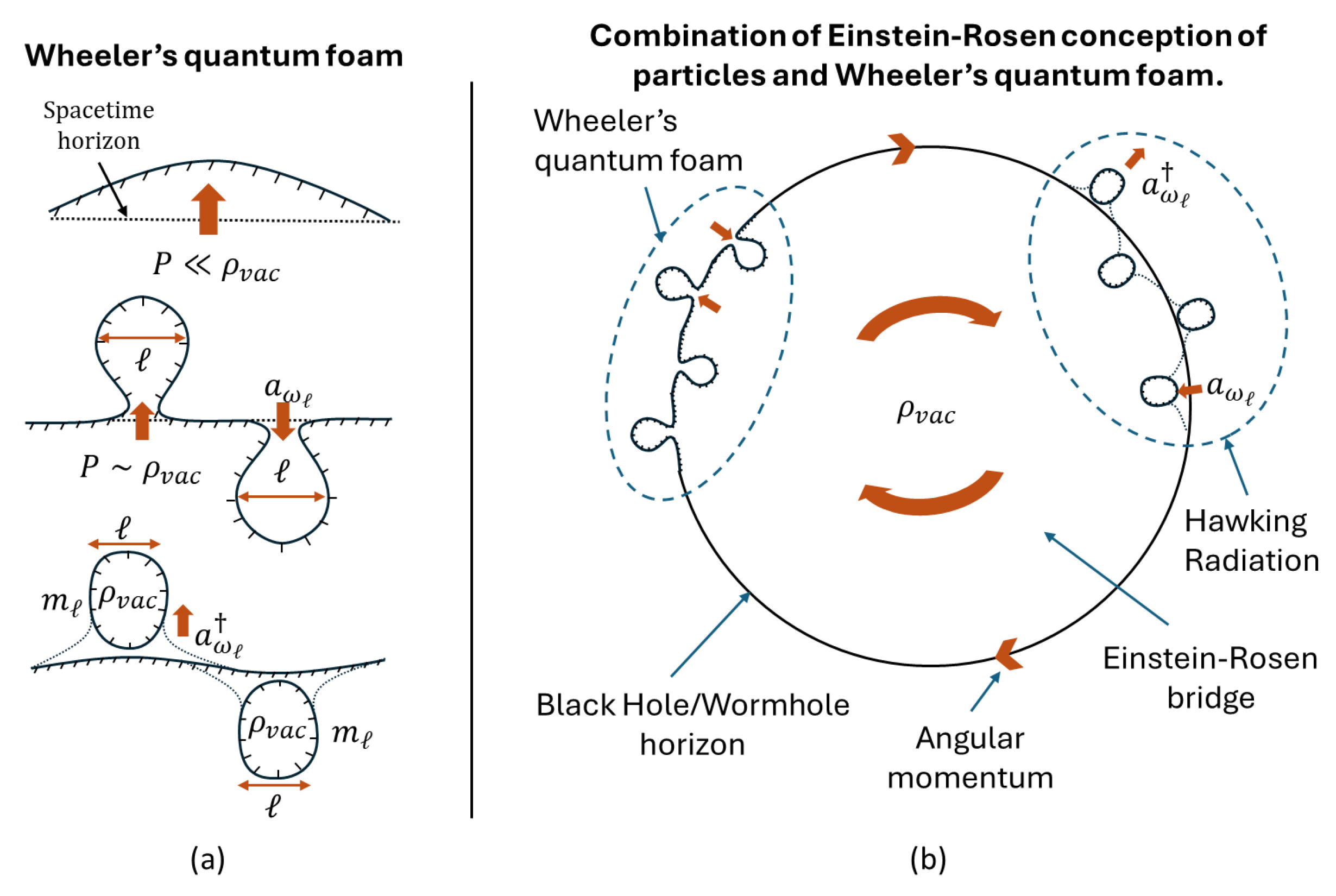

This fundamental tension between gravitational and quantum-mechanical conceptualizations of mass necessitates examination of unification attempts across theoretical physics. Efforts to reconcile these disparate theoretical frameworks have proven exceptionally challenging. Subsequent explorations, including Einstein and Rosen’s seminal work [

26], employed a purely geometric conceptualization of particles as nonsingular wormhole solutions—representing particles as topological features rather than entities

embedded within spacetime. Their approach described particles through "bridges" connecting two sheets of spacetime, avoiding singularities while unifying field and motion problems. In general relativity, these Einstein-Rosen bridges emerge from the same mathematical framework as black holes; a complete extension of the Schwarzschild solution demonstrate that a black hole from one perspective can be understood as a bridge to another region of spacetime, with the event horizon serving as the "throat." This geometrization approach to describing particles as spacetime structures, while mathematically elegant in classical general relativity, was ultimately abandoned primarily due to a significant scale discrepancy. Indeed, inserting the proton’s rest mass into the Schwarzschild solution yields a radius of

meters— approximately

times smaller than the Planck length and

times smaller than the measured proton charge radius.

This geometric perspective experienced a remarkable renaissance through Susskind and Maldacena’s ER=EPR conjecture [

27], which proposed a fundamental equivalence between Einstein-Rosen bridges (wormholes) and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen entanglement. Their revolutionary insight suggested that quantum entanglement and geometric connectivity are different manifestations of the same underlying phenomenon. In this framework, Susskind and Maldacena viewed elementary particles as microscopic black holes, with quantum entanglement between particles corresponding to wormhole connections through spacetime. This approach offered a potential resolution to the scale problem that had previously derailed geometric particle models: rather than requiring classical Einstein-Rosen bridges at the Planck scale, the ER=EPR correspondence suggested that quantum mechanical effects at these scales naturally give rise to the geometric structures that manifest as particles. However, this framework remained largely conjectural, lacking the mathematical precision necessary to make testable predictions about particle interactions and hadronic mass.

Yet, the Einstein-Rosen’s approach contains a crucial insight that remained unrecognized for decades until now. The ratio between the measured proton radius and the calculated Schwarzschild radius yields precisely the fundamental constant , where represents the gravitational coupling constant—the ratio between the strong nuclear force and the gravitational force. This is no mere numerical coincidence: the calculation was revealing that the energy density concentration required at the proton scale to produce the observed confinement force is precisely .

This critical insight lies in reversing the conventional application of the Schwarzschild solution [?]. Rather than inserting the proton’s rest mass into to obtain an impossibly small radius, one should instead use the experimentally measured proton radius to calculate the requisite mass-energy that would generate a Schwarzschild radius of this size: . This inverted calculation yields , revealing that producing the observed strong confinement force requires a mass-energy density precisely times greater than the proton’s rest mass. This is not merely a numerical relationship but a fundamental physical insight: the ratio directly quantifies the screening of quantum vacuum energy density from Planck to nuclear scales.

Had this geometric relationship been recognized, it might have been realized that Einstein and Rosen’s approach was not failing but rather revealing the profound connection between spacetime geometry, vacuum energy density, and the hierarchy of forces—a connection that would require the full machinery of quantum field theory and an understanding of vacuum fluctuations to properly elucidate. Nevertheless, this pioneering work initiated a paradigm shift toward treating elementary particles as topological features of the spacetime manifold itself."

This geometric relationship between mass-energy density and force generation finds direct empirical validation in the nuclear mass defect phenomenon. When nucleons bind to form composite nuclei, the measured nuclear mass is systematically less than the sum of constituent nucleon masses: . This mass defect converts via Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence into the binding energy , which manifests as the residual strong force maintaining nuclear cohesion. For instance, the helium-4 nucleus exhibits a mass defect of approximately 0.03 atomic mass units, corresponding to a binding energy of 28.3 MeV—representing 0.75% of the total constituent mass transformed into confining force. This reveals that mass isn’t some immutable, unchanging quantity—it’s dynamic, convertible, and intimately connected to the forces and energies operating in nature. What we’re seeing is direct evidence that mass can transform into the very forces that bind matter together.

Recently, various researchers have unsuccessfully attempted to establish a consistent integration between general relativity and quantum chromodynamics [

17,

28]. String Theory and Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) represent the most mathematically developed approaches of quantum gravity that seeks to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity. String Theory conceptualizes fundamental particles as one-dimensional vibrating strings, with gravity mediated by gravitons in a 10- or 11-dimensional spacetime [

29], offering theoretical unification via the AdS/CFT correspondence [

30], yet suffers from the landscape problem’s combinatorial explosion of possible vacuum states [

31]. LQG provides a background-independent quantization of spacetime through spin networks, predicting a granular structure at the Planck scale [

32,

33], but encounters difficulties in recovering classical general relativity at macroscopic scales and lacks experimental validation [

34]. Alternative formulations—including Causal Dynamical Triangulations, Asymptotic Safety approaches, and non-commutative geometry models—have similarly failed to resolve the fundamental theoretical incompatibilities [

35]. The persistent limitations of these approaches—despite decades of intensive theoretical development—strongly suggests the necessity for fundamentally novel conceptual frameworks that transcend conventional quantum field theoretic and geometric paradigms, particularly in addressing the physical origin of mass and the nature of strong interactions at subnuclear scales.

Given these persistent challenges in unifying quantum theories with general relativity, we must reconsider the fundamental conceptualization of mass itself. Stepping back from the specialized treatments within individual theoretical frameworks, we observe that contemporary formulations of particle mass within the Standard Model framework necessitate confronting intrinsic infinities, manifesting either as the requirement for non-perturbative treatment of the QCD Lagrangian or as the introduction of divergent bare mass terms in QED renormalization schemes. Concomitantly, the framework of QED and subsequent advancements in quantum field theory established the concept of zero-point energy (ZPE)—a non-vanishing vacuum energy density persisting at absolute zero temperature [

36,

37]. Originating from Planck’s seminal resolution of the ultraviolet catastrophe in black-body radiation theory [

38], ZPE introduced a fundamental

term in quantum harmonic oscillator energy eigenvalues. Dirac, Pauli, Feynman, and other theoretical pioneers recognized that vacuum fluctuations necessitated by ZPE generate formal divergences when integrated across momentum space to arbitrarily short wavelengths [

39]. These quantum vacuum fluctuations have subsequently received experimental validation through multiple independent phenomena, including the Lamb shift in hydrogen spectral lines [

40], macroscopic Casimir force measurements between conducting plates [

41,

42], and spontaneous electron-positron pair creation [

43]. These theoretical foundations and experimental confirmations necessitate a fundamental reconsideration of vacuum field ontology: whether quantum vacuum fluctuations function solely as regularization artifacts within renormalization procedures, or whether they constitute the primary causal mechanism underlying both inertial mass generation and the manifestation of nuclear interaction potentials.

In this paper, we propose that vacuum fluctuations constitute not merely a passive background medium for zero-point shielding, but rather the fundamental ontological substrate from which both inertial mass and spacetime curvature emerge as complementary manifestations. This proposition extends seminal contributions by Wheeler on quantum foam [

44] and Sakharov’s mechanism of induced gravity [

45,

46], both of which establish theoretical frameworks wherein Planck-scale quantum processes translating the zero-point field fluctuations, are intrinsically and coherently related to local metric perturbations at that scale. Within this unified field-geometric paradigm, baryonic rest mass can be rigorously formulated as arising from coherent, collective excitation modes of the underlying vacuum field structure—specifically, the proton acts as a quantum-mechanical resonant cavity confining specific zero-point field eigenmodes exhibiting long-range collective phase correlation. The theoretical foundation for this mechanism draws further support from electromagnetic-gravitational coupling phenomena, including Yakov Zel’dovich’s investigation of electromagnetic-to-gravitational wave conversion [

47] based on prior works [

48,

49], and Hawking’s analysis of primordial metric perturbations [

50], which collectively indicate that sufficiently coherent electromagnetic field configurations generate spacetime curvature of sufficient magnitude to effectively confine energy within sub-femtometer volumes through purely geometric boundary conditions—thereby manifesting the phenomenological properties conventionally attributed to rest mass.

The foundational element of our theoretical framework connects the proton’s observed mass and strong nuclear forces with spacetime’s local geometry by examining how the proton’s core structure curves spacetime. Our formalism is grounded in Einstein’s field equations incorporating an explicitly defined electromagnetic stress-energy tensor constructed from zero-point field correlation functions at various length scales. Under weak-field perturbation analysis, the resulting covariant wave equations decompose into a system of coupled Klein-Gordon differential equations, each characterized by distinct eigenvalues corresponding to three fundamental length scales—Planckian, Comptonian, and hadronic—which solutions manifest precise exponential attenuation profiles mathematically isomorphic to the Yukawa potential that characterizes nuclear binding interactions [

51]. This formulation elucidates how macroscopic gravitational "weakness" emerges naturally as a screened residual of the same underlying vacuum energy pressure that generates the effective "color-confining" force with explicit geometric origins within the proton’s internal structure.

The predictive capacity of the model extends beyond qualitative explanation, reproducing the empirical values of nucleon masses, quark pressure distributions, and the confining string tension derived from lattice QCD numerical simulations [

13,

14]. By reconceptualizing nuclear interactions, we replace the conventional interpretation of gauge bosons as abstract exchange particles with quantifiable metric fluctuations—physically real spacetime deformations generated by coherent electromagnetic vacuum oscillations that establish boundary conditions at critical screening horizons. Rather than relying on ad-hoc renormalization procedures that merely discard divergent terms, our approach provides a physically meaningful mechanism explaining how vacuum energy generates observable mass-energy while remaining gravitationally screened at larger scales. This unified framework—requiring no additional free parameters—demonstrates that the same zero-point fluctuations underlying fundamental QED processes simultaneously generate both hadronic matter’s self-gravitating structures and large-scale spacetime curvature—which manifests as what we classically interpret as forces, particularly here nuclear forces.

The manuscript is organized as follows: Section I presents a comprehensive overview of zero-point field theory within QFT. Section II addresses the vacuum energy density computation, its renormalization via Planck-scale cut-off, and the consequent relationship to Wheeler’s quantum foam topology. Section III derives the proton rest mass through correlation function analysis of vacuum energy fluctuations yielding the observed decoherence mechanisms manifest an apparent Hawking temperature. Section IV solves Einstein’s equations with quantum vacuum stress-energy. Section V analytically computes the proton rest mass as the Hawking radiation spectrum emanating from the proton’s core black hole structure identified in Section IV. Section VI examines the implications of these results for spacetime metric deformation through solutions to the coupled Klein-Gordon equation system, demonstrating that proton’s internal mass-energy structure induces observed phenomena including color confinement and residual strong nuclear interactions. The discussion Section broadens the theoretical framework to cosmological scales.

4. From Quantum Vacuum Fluctuations to Gravitational Field in General Relativity

The quantum vacuum’s microscopic fluctuations play a crucial role in shaping the geometry of spacetime through their collective behavior. These fluctuations manifest as minute disturbances in the quantum fields permeating all of space, creating a dynamic fabric that simultaneously responds to and influences gravitational forces. In his groundbreaking 1967 work, physicist Andrei Sakharov proposed a microscopic foundation for gravitation arising from quantum vacuum fluctuations. Sakharov introduced the concept of "metric elasticity of space," incorporating the Planck length cut-off to establish a direct equivalence between electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations and the gravitational constant

G [

45].

with

, a geometrical constant on the order of unity and

is the sum of all modes of the electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations. Considering the Planck length cut-off, according to Sakharov’s definition, the gravitational force results directly from the energy density of the fluctuations in the quantum foam determined by the scale of the smallest oscillator [

70]

5. Here, the electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations are the source of spacetime elasticity generating the gravitational constant. However, the mechanism under which the microstates of the quantum vacuum electromagnetic field is converted to a gravitational component is undefined.

By treating the microstates of electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations as the fundamental building blocks of spacetime, we can demonstrate how classical gravity emerges from quantum mechanics. This approach creates a natural bridge between quantum field theory and general relativity, where classical geometry emerges as a collective behavior arising from quantum vacuum states.

4.1. First Screening : Electromagnetic Vacuum Fluctuations to Gravitational Wave Generation

In 1973, physicist Yakov Zel’dovich, building upon earlier work [

48,

49,

71], characterized the conversion of electromagnetic waves into gravitational waves when propagating through a strong magnetic field [

47]. Zel’dovich demonstrated that an electromagnetic wave with energy density

traveling through a magnetic field

H partially transfers its energy into gravitational energy. This gravitational energy flux along the propagation direction (specifically, along the

r-direction in spherical coordinates) can be quantified using the Landau-Lifschitz pseudo-tensor component

. Although this mechanism represents a classical effect derived directly from Einstein’s field equations (see

Appendix E), it exhibits characteristics analogous to a phase transition, wherein an extremely coherent electromagnetic field at the Planck scale undergoes an abrupt transformation to a lower coherence, curving spacetime at the hadronic scale.

While Zel’dovich described this mechanism as a ’conversion’ between electromagnetic and gravitational waves, it is crucial to understand that the electromagnetic wave generates a non-zero stress-energy tensor that produces gravitational curvature through Einstein’s Field Equations. The amount of gravitational curvature depends on the energy density of the electromagnetic wave, which in our case is related to the Planck plasma coherence or phase in that region of space. At sufficiently high energy densities to overcome spacetime elasticity, the electromagnetic field creates a gravitational field strong enough to confine most of the electromagnetic energy within a bounded region, i.e. a bubble is formed.

This self-confinement mechanism establishes a direct equivalence between the electromagnetic and gravitational components, both manifestations of the same underlying physical reality, rather than separate phenomena. The gravitational and electromagnetic descriptions represent complementary physical manifestations of a unified mechanism, such that the term ’conversion’ here describes how electromagnetic waves decohere in the presence of their own gravitational fields, with most energy remaining trapped in electromagnetic form while a portion manifests as gravitational radiation.

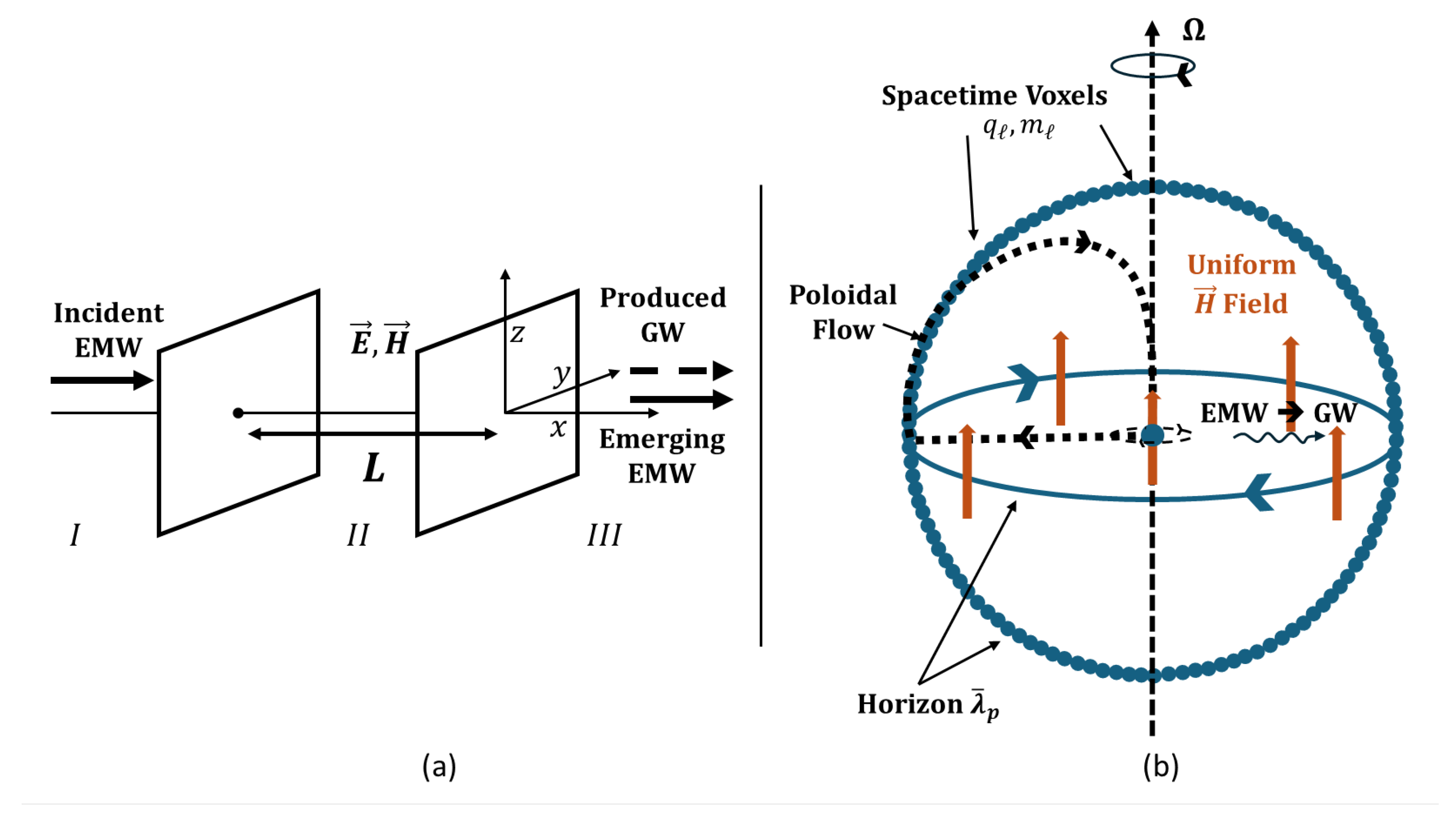

In this work, we model proton mass-energy density as the manifestation of quantum electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations’ collective behavior (Planck plasma flow) at the Planck scale producing gravitational energy flux at the proton scale. The Planck plasma flow can be conceptualized as spacetime voxels carrying a fundamental Planck charge

and exhibiting a toroidal flow (see

Figure 3.b). This flow generates vorticity and ensures high coherency (

) within the proton’s core. This configuration enables the production of an incident electromagnetic wave radiating radially from the center with energy density

, passing through the static magnetic field

H produced by the circulation of spacetime voxels at the proton’s core surface, identified at its reduced Compton wavelength

. Due to the extremely high quantum vacuum energy density, which vastly exceeds the Schwarzschild condition, the resulting electromagnetic field is sufficiently strong to curve spacetime, generating a gravitational force that characterizes the proton’s mass-energy. Utilizing the formalism on which Zel’dovich’s analysis was built upon [

48,

49], we evaluate the corresponding gravitational component by computing the Landau-Lifschitz pseudo-tensor in the weak field approximation for Einstein’s field equations, which gives the energy flux per unit time radiated by the proton’s core surface

Figure 3.

(a) Initial work from Boccaletti

et al. investigating the conversion efficiency of electromagnetic waves (EMW) into gravitational waves (GW) as they propagate through a strong static electromagnetic field (

) over distance

L (adapted from [

49]). (b) Our proposed model illustrating the EMW-to-GW conversion mechanism at the hadronic scale. Here, an EMW generated by a spacetime voxel undergoes conversion to a GW. The magnetic field strength

is produced by a spherical shell of Planck charge

, which forms through the circulation of spacetime voxels orbiting at the modified Compton wavelength

.

Figure 3.

(a) Initial work from Boccaletti

et al. investigating the conversion efficiency of electromagnetic waves (EMW) into gravitational waves (GW) as they propagate through a strong static electromagnetic field (

) over distance

L (adapted from [

49]). (b) Our proposed model illustrating the EMW-to-GW conversion mechanism at the hadronic scale. Here, an EMW generated by a spacetime voxel undergoes conversion to a GW. The magnetic field strength

is produced by a spherical shell of Planck charge

, which forms through the circulation of spacetime voxels orbiting at the modified Compton wavelength

.

where

is vacuum permeability and

is the path length of the electromagnetic wave through the magnetic field (see

Appendix E for the detailed derivation).

We compute the proton’s internal magnetic field at its reduced Compton wavelength

through the coherent flow of Planck plasma quantum vacuum fluctuations. As a first-order approximation, these voxels collectively behave as an outer charged rotating spherical shell, thereby generating a constant magnetic field vector that aligns parallel to the rotation axis (here the z-axis). The magnitude of this intrinsic magnetic field can be expressed as

where

is the pulsation of the toroidal circulation undergoing four poloidal circulations in one toroidal rotation. With path length

, the energy transfer from electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations to the gravitational component can be computed as

Thus, the total gravitational wave energy

radiated at the surface

over a characteristic time

is

which is equivalent to a gravitational energy density within the enclosed volume

We can now identify the conversion coefficient

of the electromagnetic wave energy density

converting to a gravitational wave travelling through the proton’s core as

This extremely small gravitational conversion coefficient

of the electromagnetic vacuum density

represents a significant screening of the energy density available within the proton at that scale—thus the weakness of gravity relative to the electromagnetic force. By examining this screening coefficient, we can deduce a discrete mechanism clearly apparent in

, which we recognize from previous work [

69] as a surface ratio defined by the Planck-scale entities that pixelizes the surface

where

is a surface

at the reduced proton Compton wavelength (

) tiled by the cross-Section

of Planck scale voxels obtained earlier (see Equation (

37)). This surface appears to reduce the coherency of electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations, transducing a small quantity into gravitational wave energy density.

This formulation bridges the continuous and discrete approaches to quantum gravity. While Zel’dovich’s original analysis treated spacetime as a continuous medium through which waves propagate, our pixelization by Planck-scale voxels introduces a fundamental discreteness that resolves several theoretical inconsistencies. The ratio effectively quantifies the translation between these paradigms—representing how continuous field descriptions at the proton scale emerge from discrete Planck-scale phenomena. This duality allows us to maintain the computational advantages of continuous field equations while simultaneously acknowledging the discrete, quantized nature of spacetime at its most fundamental level. The screening coefficient thus represents not merely an energy conversion factor but a fundamental bridge between continuous mathematical formalisms (as exemplified in Einstein’s field equations of general relativity) and discrete mathematical approaches (as manifested in quantum mechanical operators and lattice quantum chromodynamics). This theoretical framework not only reconciles seemingly disparate mathematical treatments but also provides a foundation for deriving further physical insights into the quantum gravitational nature of hadrons.

Consequently, returning to our gravitational density computation (Equation (

56)), we find the following mass-energy

This remarkable result reveals the Schwarzschild solution , describing the energy density of a black hole with radius resulting from the collective coherent behavior of electromagnetic quantum vacuum fluctuations in the enclosed volume curving spacetime. This establishes a profound connection between quantum vacuum phenomena and classical gravitational structures at the hadronic scale. The emergence of the Schwarzschild metric at precisely the reduced Compton wavelength of the proton suggests that the gravitational screening mechanism we have identified corresponds to a fundamental topological feature of spacetime.

4.2. Kerr-Newman Solution and Black Hole Particle

Given the black hole structure found in the proton’s core, we can now rigorously confirm our first approximation of the magnetic field strength

H utilizing the Kerr-Newman solution for a charged rotating black hole at the hadronic scale with mass

, charge

, and angular momentum

. These parameters correspond to radius

and angular velocity

. In Boyer-Lindquist coordinates,

, where

M is the total energy of the black hole which can be approximated as

since charge and angular momentum contribute minimally to total energy. Therefore, the transverse magnetic field is

where

is the

component of the electromagnetic Faraday tensor in spherical coordinates (see

Appendix E). This result validates our previous first approximation model for predicting the internal proton’s magnetic field amplitude and confirms the Zel’dovich conversion factor characterizing quantum vacuum fluctuation conversion into gravitational effects or more precisely in terms of spacetime curvature that produce the black hole structure within the proton’s core.

The relationship between discrete Planck-scale physics and continuous gravitational formalism becomes particularly elegant when expressed in terms of screening of vacuum energy density

where

is the black hole mass-energy density. This formulation demonstrates how the seemingly enormous electromagnetic zero-point energy (

) is naturally regulated by a surface-to-volume ratio

which translates spacetime curvature reduction from the Planck scale to the reduced Compton wavelength event horizon.

This leads back to Einstein and Rosen’s visionary approach to unifying particle physics with general relativity. In their July 1935 work, they proposed that elementary particles are not point-like objects existing within space, but manifestations of spacetime geometry itself—specifically, bridge-like structures (now known as wormholes) equivalent to the Schwarzschild solution. Their revolutionary perspective sought to reduce the complexities of particle physics by treating protons and electrons as purely geometric features.

This approach was ultimately abandoned primarily due to a significant discrepancy in the calculation of the size of these black hole/wormhole tubes. Indeed, inserting the proton’s rest mass into the Schwarzschild solution yields a radius of

meters—approximately 20 orders of magnitude smaller than the Planck scale and 39 orders of magnitude smaller than the proton scale. However, this apparent contradiction contains a crucial insight. The ratio between the measured proton radius

and the calculated Schwarzschild radius

yields the fundamental constant

relating the gravitational force to the color force or strong force

Had this been noticed, it may have been realized that this calculation was hinting that the energy curvature at the proton scale—which produces the strong confining force—results from an energy density concentration

within that region of space. While the relationship of spacetime curvature and the forces at the hadronic scale, which includes a Yukawa potential, will be treated in the

Section 7.1, it is important to notice here that our formulation resolves this scale discrepancy by considering quantum vacuum fluctuations and a screening mechanism as the critical elements missing from Einstein and Rosen’s original conception. The screening coefficient

effectively quantifies what Einstein and Rosen were missing—the vacuum energy contribution that enables the geometric approach to yield physically consistent results. By incorporating Planck’s zero-point energy (ZPE), we demonstrate how Einstein’s geometric vision of particles as spacetime features can be reconciled with observed physical phenomena, effectively completing Einstein’s attempt at unification through geometry.

While the notion that elementary particles may be black holes or contain singularities at their core might initially seem radical, it becomes more plausible when considering that quantum vacuum fluctuation densities in localized space substantially exceed the Schwarzschild threshold for black hole formation—yet remain screened by the mechanisms we have demonstrated. Significantly, the resulting energy values align precisely with measured nuclear confinement forces (detailed in

Section 7.2.1). In string theory, the concept of particles being related to black hole physics became prominent resulting in Leonard Susskind’s observation that “One of the deepest lessons that we have learned over the past decade is that there is no fundamental difference between elementary particles and black holes” [

72].

This screening mechanism of quantum vacuum fluctuations fundamentally transforms both the concept of black hole formation and our understanding of mass in Quantum Field Theory (QFT). Rather than vacuum fluctuations being responsible merely for the bare mass shielded by virtual particles, our model establishes that these fluctuations constitute the primary source of mass, as demonstrated by the correlation functions derived in this paper. The shielding effect arises from the dynamical properties of spacetime voxel flow, exhibiting behavior comparable to quark-gluon plasma at thermal and chemical equilibrium with their color charge and force.

However, our geometric framework stands in stark contrast to current approaches relies on lattice QCD, which model nuclear confining forces and proton rest mass (with the Higgs mechanism accounting for only 1-5%). This computational method discretizes spacetime into a four-dimensional grid where quark and gluon interactions require intensive numerical approximations. Unlike our analytically elegant solution that provides clear physical insights, lattice QCD demands enormous computational resources—some calculations requiring years of continuous processing on the world’s most powerful supercomputers just to obtain approximate solutions.

Despite this extraordinary computational investment, lattice QCD cannot fundamentally explain why the strong force exceeds gravity by a factor of —this enormous disparity is simply accepted as an unexplained given. While producing numerical predictions, the computational brute-force approach obscures rather than illuminates the underlying physical principles that connect these fundamental forces.

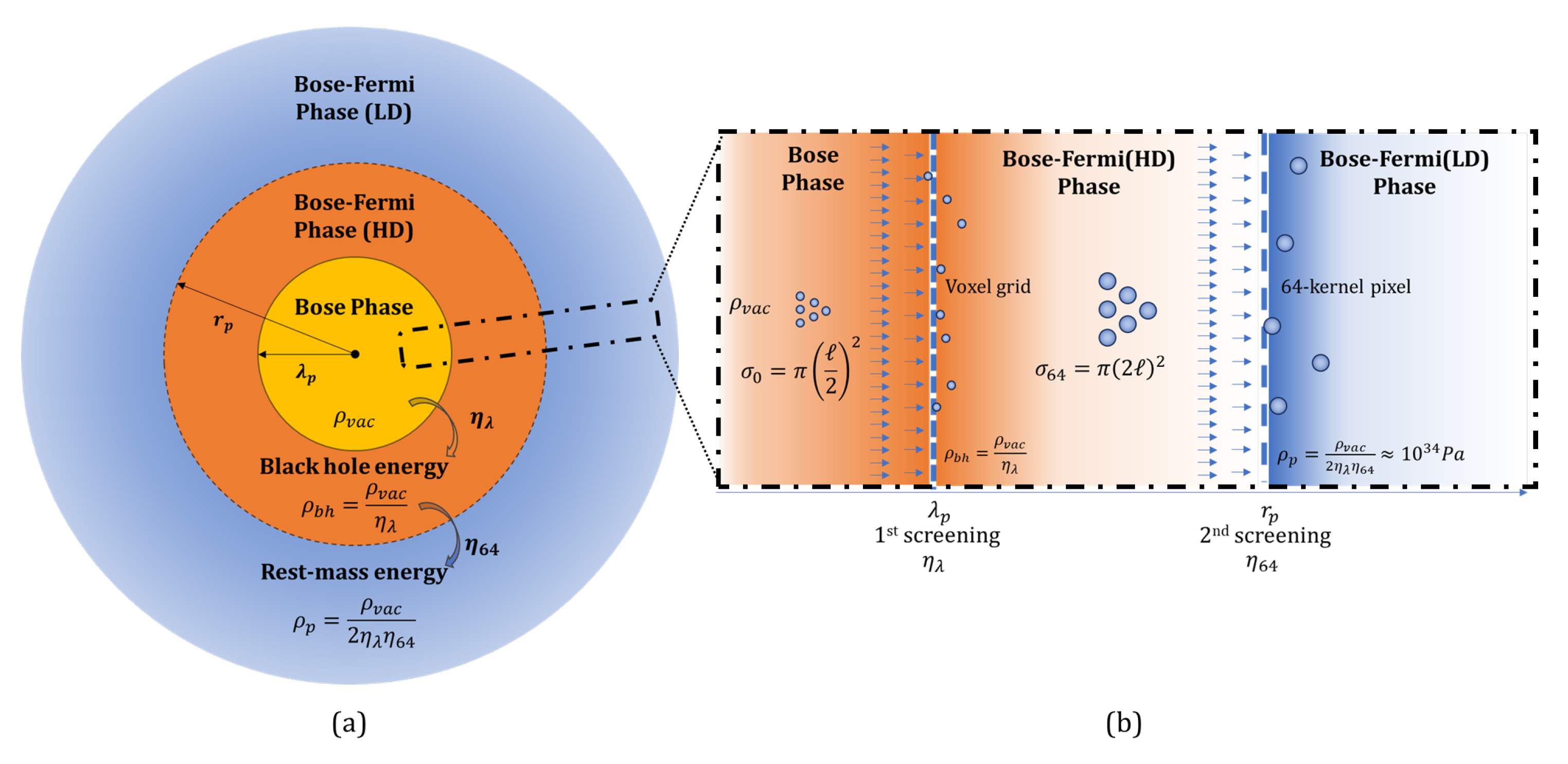

Our analysis demonstrates that the screening process of quantum vacuum fluctuations, due to an exponential decay phase transition (see

Section 6) decoherence at the proton scale, constitutes the source of mass, nuclear and gravitational forces. This spacetime Planck plasma model characterizes a phase transition between a coherent, high-energy Bose phase at the center that decoheres to a high density Bose-Fermi mixture at the black hole horizon. This high-density Bose-Fermi mixture creates a screening boundary where quantum coherence partially breaks down, comparable to atomic superfluids exhibiting both condensate properties and quantum statistical effects (see

Figure 4.a).

This screening mechanism can as well be generalized beyond the proton scale to any volume

V containing Planck plasma vacuum density

. The surface screening parameter

mediates the relationship between vacuum fluctuations energy and mass-energy

This formulation connects quantum vacuum fluctuations to classical gravitational phenomena, with

describing how vacuum energy transforms across spacetime structure boundary surfaces.

Contrary to the classical approach, which views black hole formation primarily as the result of accreting infalling material to a critical limit, our findings demonstrate that black holes form as a result of natural spacetime behavior at the Planck scale resulting in a high electromagnetic energy density in a region. Specifically, black holes emerge from a state of coherence among collective quantum vacuum fluctuation oscillators that generate an electromagnetic energy density, curving spacetime, an effect classically attributed to mass. This coherence mechanism fundamentally relates to the angular momentum of an oscillator, as Max Planck originally described. The coupling of these oscillators produces collective behaviors analogous to quantum vortices in a turbulent spacetime manifold flow, which we term a Planck Plasma flow, manifesting as what we observe as black hole dynamics.

These quantum vacuum coherent behaviors at the source of black holes formation may explain recent James Webb Space Telescope observations of supermassive black holes at redshifts

in the early universe, where conventional star formation and accretion timeframes appear insufficient to produce such massive structures [

73,

74]. Furthermore, this mechanism is in accordance with Stephen Hawking’s analysis of early universe formation, which concluded that “a sufficient concentration of electromagnetic radiation can cause gravitational collapse”, forming primordial and elementary black holes at Planck length and Compton wavelength scales [

50].

This is as well consistent with the holographic principle and Bekenstein’s entropy conjecture. Thereafter, Hawking-Bekenstein entropy can be written function of the surface information

where

represents the Boltzmann constant. This formulation establishes a direct measure of surface information, leading to Hawking temperature (

Section 5.1). At the horizon, entropy maximizes as coherent modes undergo decoherence, analogous to a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) quantum critical point. These nearly gapless Bogoliubov modes—collective quantum excitations requiring minimal energy to activate—exist at the horizon where quantum effects become significant and function as holographic degrees of freedom accounting for black hole entropy. This quantum mechanical framework posits that these excitations on the two-dimensional horizon surface encode the information of the entire three-dimensional black hole, providing a microscopic explanation for Bekenstein-Hawking entropy consistent with Dvali’s graviton condensate model [

75], comparable to the Hawking-Page transition in AdS-CFT correspondence [

30].

The correlation functions (treated earlier in Equation (

45)) establish a direct link between the highly coherent Bose phase of quantum vacuum fluctuations

and rest mass production at the proton’s effective time scale, suggesting a second decoherence mechanism. In the next Section, we will analytically describe how this second screening surface manifests through Hawking radiation at the proton scale, quantifying the thermodynamic properties of the screening boundaries and establishing precise correspondences between quantum gravitational phenomena and experimentally measurable parameters in hadron physics.

6. Solving Einstein’s Field Equations for a Continuous Energy Density Profile

In the previous Sections we described mass as a decoherence state of the quantum vacuum electromagnetic field through the correlation function. This ultimately identified an internal proton black hole horizon at the Compton wavelength and the proton rest-mass at its charge radius. Having established these two discrete screening boundaries, we now seek to derive the continuous energy density profile characterized by metric fluctuations that generates forces between and outside these horizons. While our analysis has revealed that vacuum energy screening manifests through discrete boundaries at the Compton wavelength and charge radius, the underlying principle of general covariance in Einstein’s field equations necessitates a continuously varying screening function that modulates the Planck plasma flow across the entire spacetime manifold, reconciling the discrete quantum transitions with the differentiable nature of classical gravitational fields.

Utilizing the wave equation derived by Boccaletti

et al. (see

Appendix E) from Einstein’s field equations within the weak field approximation, we find an equivalent Klein-Gordon equation with a mass term characteristic of each phase of the Planck plasma. We solve these equations for a spherically symmetric geometry, revealing notable parallels with massive scalar field theories that mediate both short and long-range interactions in quantum field theory. The total continuous energy density emerges as the sum of all solutions corresponding to each phase of the continuous Planck plasma flow.

Under the weak-field approximation (

), Einstein Field Equations can be expressed as a wave equation

where

represents metric fluctuations around a flat spacetime region characterized by the Minkowski metric

using the standard

signature convention. (

is used here to avoid confusion with the screening factor

.) Boccaletti and Zel’dovich calculated the energy conversion efficiency between an incoming electromagnetic wave of amplitude

a and the resulting gravitational wave

as it propagates through a region of length

d containing a static magnetic field

(

Figure 3). In this configuration, the Faraday tensor

combines both static field components and incident wave terms with amplitude

a

The electromagnetic stress-energy tensor (see

Appendix E) is given by

The solutions of Equation (

91) for metric fluctuations

represent gravitational waves converted from electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations

where

are static-field-dependent constants appearing in Einstein field equations (see

Appendix E). From Equation (

94), we can derive

By lowering

index and keeping the first order in

, this transforms Equation (

91) into

We find that Equation (

96) corresponds to a Klein-Gordon equation for a massive scalar field with complex mass

. In this formulation,

represents the wave number of the incident electromagnetic wave, while

d denotes the conversion pathlength specific to each region of the screening mechanism. These parameters collectively determine the efficiency and spatial characteristics of the electromagnetic-to-gravitational wave conversion process.

Remarkably, this mass term emerges naturally from our formalism without requiring the introduction of a larger counterterm mass—in contrast to quantum electrodynamics (QED), where an infinite bare mass must be introduced for the electron. In our model, the electromagnetic wave mode and the characteristic scale of the resonant cavity d together determine the effective mass that characterizes the metric fluctuations .

We extend Boccaletti’s framework to spherically symmetric geometry by solving for metric fluctuations between the screening horizons. This approach yields a Klein-Gordon equation while preserving the connection to Einstein Field Equations with electromagnetic stress-energy tensor sources. Unlike conventional quantum field theory where the massive scalar field equation serves as a source term, our model identifies the electromagnetic field generated by coherent quantum vacuum fluctuations curving spacetime as the source of the mass.

The derived Klein-Gordon equation possesses remarkable properties due to its complex mass term. The imaginary component generates a dissipative mechanism—manifested through exponential decay (Yukawa-like form)—while simultaneously mediating the electromagnetic-to-gravitational wave conversion process. This mathematical framework exhibits crucial phase-dependent adaptability, enabling the specification of distinct

and

d parameters for each phase. Following Boccaletti

et al., we constrain our analysis to the case where

, ensuring gravitational waves vanish in region I while being exclusively emitted in region III (

Figure 3.a).

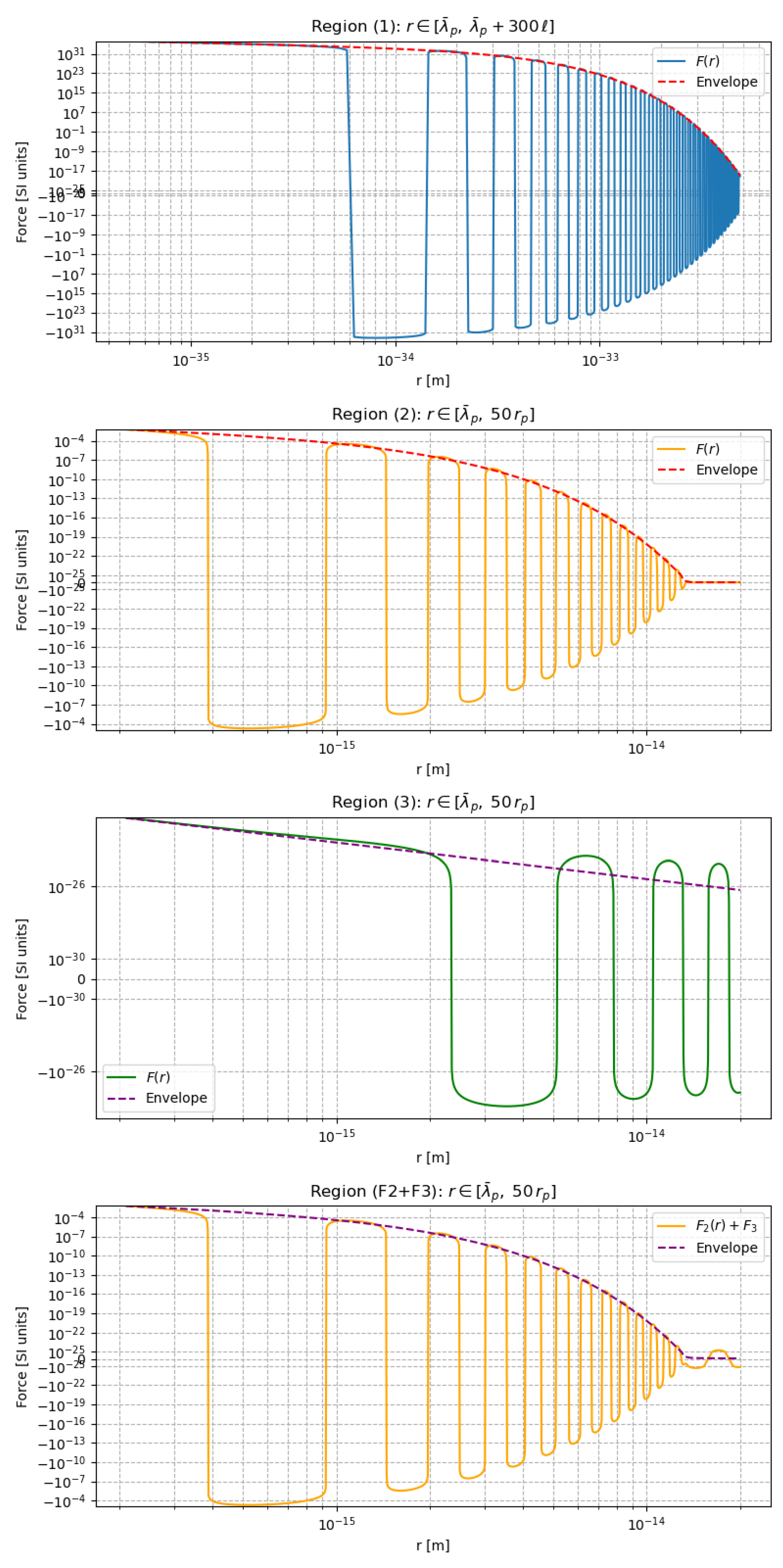

Our model describes the proton as a hierarchical quantum-gravitational structure characterized by three distinct phases, each associated with a specific horizon and screening mechanism:

- 1.

The innermost Bose phase, dominated by quantum vacuum fluctuations at the Planck scale

- 2.

-

The intermediate Bose-Fermi phase beginning at the reduced Compton wavelength boundary (), subdivided into:

- 3.

The outermost Fermi phase beginning at the full Compton wavelength (), governing long-range interactions

Each phase boundary represents a screening surface where electromagnetic waves generated by quantum vacuum fluctuations convert to gravitational waves through the Klein-Gordon process described above. This decoherence mechanism progressively transforms vacuum energy (

) into the observed proton rest mass (

) through precisely defined energy density transitions at each horizon (

Table 1). The mathematical formulation below quantifies the gravitational energy flux associated with each phase and its corresponding wave function. Building upon our previous analysis (

Section 5.3), the third screening horizon at

completes our model framework.

We find discrete boundaries but it corresponds to a continuous flow of discrete Planck‘s scale entities (see

Section 2.3) across the Planck plasma phases. The dynamics of each phase is characterized by the characteristic length of the oscillators generating the incident electromagnetic waves that are converted into gravitational waves. We can therefore identify for each phase, function of its reference density, a set of parameters

characterizing the continuous decoherence mechanism embedded in the Klein-Gordon equation (

96) as presented in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Phase boundary conditions and Klein-Gordon parameters: this table describes the characteristic energy density of each phase, setting boundary conditions at the screening surface previously identified within the discrete approach of the decoherence mechanism incorporated in the correlation functions. Each phase function of its reference density is associated to a set of parameters

characterizing the continuous decoherence mechanism embedded in the Klein-Gordon equation (

96).

Table 1.

Phase boundary conditions and Klein-Gordon parameters: this table describes the characteristic energy density of each phase, setting boundary conditions at the screening surface previously identified within the discrete approach of the decoherence mechanism incorporated in the correlation functions. Each phase function of its reference density is associated to a set of parameters

characterizing the continuous decoherence mechanism embedded in the Klein-Gordon equation (

96).

| Phase |

Boundary Conditions

(Discrete) |

Klein-Gordon Parameters

(Continuous) |

| Bose |

|

|

| Bose-Fermi (HD) |

|

|

| Bose-Fermi (LD) |

|

|

| Fermi |

|

|

For the spherically symmetric case, we restrict our analysis to the non-zero stress-energy tensor components

and

. The metric perturbations contributing to the gravitational wave energy flux

are characterized by

in wave equation (

96). Exploiting the spherical symmetry, the solution becomes independent of angular coordinates

and

, yielding a general spherical wave of the form

where

A and

B are amplitude constants with units of length, representing outgoing and incoming waves, respectively. The resonant coupling between the induced gravitational wave and the incident electromagnetic wave requires identical temporal frequencies

(as noted by Gertsenshtein, [

48]), ensuring that the solution satisfies the dispersion relation

thus

with

with

.

By considering only non-diverging solutions (as expanding gravitational waves with a diverging amplitude is not physically valid), we set

and the solution for

follows a Yukawa-like form

Therefore, using the results from Boccaletti

et al. (see

Appendix E), we compute the energy flux for any radius

r

where

is the number of voxels on the surface of radius

r as defined in

Section 4.1. As demonstrated in Equations (

54) and (

55), the energy flux

across a screening (or phase transition) surface is equivalent to an energy density characterizing the new phase through the relation

, such that the boundary conditions of

Table 1 set the energy flux at each phase transition surface.

The condition

ensuring only converging gravitational waves yields

and

with

. This result demonstrates notable correspondence with Davies’ result carries significant mathematical interest [

76]. In his 1989 analysis of Kerr-Newman black holes in de Sitter space, Davies identified a critical relationship between angular momentum and mass at

where the heat capacity discontinuity marks a second-order phase transition. The same mathematical value emerges in our formulation as the ratio

characterizing the spatial decay rate of metric fluctuations. For uncharged rotating black holes (Kerr case with

), Davies demonstrated that this specific ratio represents a critical threshold in black hole thermodynamics, separating regions of negative and positive specific heat. In our model, although we employ the full Kerr-Newman metric framework, the electromagnetic charge contribution is substantially smaller than the angular momentum component, allowing us to effectively approximate

in alignment with Davies’ Kerr black hole case. This mathematical parallel aligns with our framework where mass emerges as a decoherence state of quantum vacuum fluctuations undergoing phase transitions whose coherence is established by the angular momentum of the Planck plasma flow. The appearance of the same ratio in both contexts suggests a connection between the decay characteristics in wave equations and phase transition boundaries in gravitational systems. The mathematical correspondence with Davies’ work further suggests that the thermodynamic properties of macroscopic black holes and the quantum-gravitational structure of hadrons share deeper underlying principles than previously recognized and will be treated in an upcoming paper.

The gravitational energy flux can be written as

We can now compute the gravitational energy flux for any radius

r by determining the constant

B for each phase characterized by the parameter

and the boundary condition of

Table 1.

- 1.

-

Bose-Fermi (HD) Phase : First Screening ()

The energy density of the high-density Bose-Fermi phase emerges from the primary screening of quantum vacuum fluctuations, wherein kernel-64 aggregates of spacetime voxels coherently generate electromagnetic waves with characteristic wavelength

(see

Section 5.3). Applying the boundary condition

at the reduced Compton wavelength, we derive the amplitude constant

, yielding

and the corresponding gravitational wave

- 2.

-

Bose-Fermi (LD) Phase : Second Screening ()

The energy density of the low density Bose-Fermi phase resulting from the second screening mechanism involves electromagnetic waves generated by the proton black hole horizon, with wavelength

. The boundary condition

yields

, and results in

with the corresponding gravitational wave

- 3.

-

Fermi Phase: Long-Range Dynamics (_)

This final case represents the long-range behavior, incorporating a third screening of the gravitational energy flux where

which leads to

. Utilizing a first-order approximation where

and

, we obtain

And the corresponding gravitational wave

where

represents the gravitational coupling constant characterizing the relationship between the strong nuclear force and the gravitational force and, here, phase transitions of the Planck plasma flow associated to a change in energy density as described in

Section 4.1.

The total gravitational energy flux as a function of radius

r can be expressed as the sum of all three contributions (noting that

)

Our mathematical framework reveals a distance-dependent hierarchy in the gravitational energy flux, with each component dominating at a specific characteristic scale:

- 1.

The first term dominates in the innermost high density Bose-Fermi phase region near the reduced Compton wavelength

- 2.

The second term becomes predominant at intermediate distances around the proton charge radius in the low density Bose-Fermi phase.

- 3.

The third term governs the long-range interactions at distances far beyond the proton radius () in the Fermi phase.

This formulation provides a complete and continuous description of gravitational wave energy flux at any radial position near the proton. While the energy flux varies continuously throughout space, it undergoes its most dramatic changes in localized narrow regions, defining discrete screening surfaces. Importantly, our analysis reveals that vacuum energy () does not transfer uniformly throughout the volume, but rather experiences a steep attenuation in the vicinity of each screening surface—a fundamental quantum-gravitational phenomenon mediated by the Yukawa-type exponential decay with phase-dependent characteristic length scales. The efficiency of this transfer mechanism is precisely quantified by the screening parameter , which counts the number of Planck-scale spacetime voxels participating in the energy transfer at each spherical boundary surface. To clarify, our approach does not result in gravitational field screening but instead describes a screening mechanism of the electromagnetic field energy density through exponential decay, which consequently leads to spacetime curvature reduction. In the following Section, we explore how this systematic reduction in curvature manifests as the varying strength and range characteristics of nuclear confining forces within the proton’s core structure eventually leading to the Newtonian gravity.

8. Discussion and Theoretical Implications at the Cosmological Scale

Having established the foundational screening Equation (

87) in our analysis, we now extend our discussion to the broader theoretical implications of this formalism at the cosmological level. The demonstrated geometric relationship between electromagnetic quantum vacuum fluctuation decoherence and mass origin manifests at discrete spacetime boundaries that establish specific scale horizons for the continuous Planck plasma flow analytically computed in

Section 6. While the underlying energy transfer remains continuous across scales, these boundaries mark critical thresholds where the fluid structure undergoes abrupt transitions in quantum coherency state over remarkably short distances. This creates a dual discretization framework: first, through the fundamental spacetime voxelization at the Planck scale, and second, through emergent scale boundaries that demarcate coherency transitions—while preserving the continuity of the underlying plasma flow. These semi-permeable screening surfaces, characterized by parameter

, function as a fundamental coupling constant between vacuum energy at the Planck scale and observable mass at the proton scale—suggesting profound consequences for our understanding of quantum gravity.

This scaling relationship spans approximately 20 orders of magnitude in spatial dimension from the Planck scale to the proton scale, and extends symmetrically to cosmological dimensions. The geometric mechanism for energy reduction identified in our analysis creates a hierarchical propagation pattern across all scales, providing a mathematical bridge between quantum fluctuation dynamics and macroscopic cosmological parameters. This quantitative framework not only generates testable predictions for observational cosmology but also demonstrates how quantum geometric relationships become holographically encoded in the universe’s large-scale structure, suggesting a fractal-like organizational principle spanning the entire physical spectrum.

When we scale Einstein’s Field Equations to the universe’s observable size, we find the spacetime curvature corresponding to the Hubble constant

This scaling yields an equivalent energy density

Here, we recognize our first screening mechanism characterizing the black hole condition operating at the universal scale

. Remarkably, this relationship leads directly to

This final equation reveals a profound cosmological insight: the screened vacuum energy density at universal scale precisely corresponds to the critical density (

) measured by observational cosmologists—potentially unifying phenomena currently attributed to dark matter and dark energy. Moreover, our analysis demonstrates that the universe’s energy density satisfies the black hole condition, corroborating recent theoretical proposals that the observable universe itself exhibits black hole characteristics, as we previously established in [

85].

The proton’s total internal energy from quantum vacuum fluctuations, contained within its Compton radius volume

is given by

This enormous amount of energy equals the total energy in the observable universe, calculated using the current estimate of the Hubble constant (

)

This mathematical relationship reveals a crucial aspect of the holographic principle: each proton contains the same information as the entire observable universe. Like a hologram where each fragment contains the whole image, every node in the network stores complete information about the entire system, though only a tiny fraction is locally accessible due to the screening mechanism.

This formulation suggests that universal structure may manifest as a literal holographic interference pattern generated by quantum vacuum fluctuations, producing the observed hierarchy of forces and masses across multiple scales. The fundamental scaling parameters emerge directly from the screening mechanism, establishing quantitative relationships between seemingly disparate physical phenomena. We can express this relationship more elegantly through holographic ratios

—a fundamental geometric parameter defined as

[

85] which link mass-energy and geometric properties at both scales

Through this dimensionless representation, patterns emerge that illuminate scale connections. We can express this scaling law using the gravitational coupling constant

:

This shows how information encoded at the proton level mirrors the universe’s large-scale structure. The gravitational coupling constant serves as a bridge between quantum interactions and cosmic parameters, revealing connections between fundamental forces:

These relationships demonstrate that

serves as a natural scaling parameter across diverse universal scales, as previously shown by Carr and Rees [

93]. Our analysis reveals a profound connection between black hole proton cores and the force hierarchy, spanning from strong interactions (

) to gravity (

).

The holographic principle manifested in these equations suggests a bidirectional information flow between scales. The Planck-scale vacuum fluctuations screening at the proton’s surface boundary influences universal dynamics, while cosmological evolution imprints itself on local Planck plasma flows. This reciprocal relationship establishes a fundamental coherence mechanism within the proton—wherein sustained angular momentum maintains quantum vacuum fluctuations coherency to generate the vacuum energy density mass source term

, which subsequently undergoes decoherence due to the intrinsic spacetime elasticity within Einstein’s field equations. Furthermore, this bidirectional coupling suggests that universal expansion directly correlates with new protons formation, as the system compensates for pressure loss from volumetric expansion by generating additional hadronic matter as Einstein envisioned in his ’lost’ paper published in 2014 [

94].

At the cosmological scale, this relationship gives rise to the cosmological constant

, emerging naturally from our screening mechanism:

where the density parameter for dark energy is

and

is the universe holographic ratio [

85]. This derivation provides a theoretical foundation for the observed cosmic acceleration, offering a unified description of gravitational phenomena across scales—from quantum to cosmological.

Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrate that quantum electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations generate extreme spacetime curvature at the proton scale, providing a self-consistent mechanism for mass generation and confinement without ad hoc scalar fields or high-dimensional operators. By treating the proton as a resonant cavity and analyzing correlation functions of zero-temperature blackbody radiation, we quantitatively derive the proton’s rest mass from coherent electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations. The decoherence of these fluctuations manifests a Hawking-like temperature of a proton-size black hole, yielding a Kerr–Newman structure at the proton’s reduced Compton wavelength.

By extending zero-point energy (ZPE) to a multi-phase quantum fluid framework, establishing that electromagnetic modes transition from Planck scale to observable hadronic mass via two successive screening across semi-permeable horizons which function as phase boundaries, effectively transducing vacuum energy into observable rest mass-energy while simultaneously reducing local spacetime curvature. Unlike lattice QCD, this approach analytically explains why nucleon mass derives primarily from strong confinement dynamics rather than the Higgs mechanism which only predicts of their mass. While the decoherence process follows continuous field equations, we find it to be equivalent to a quantized screening of the electromagnetic vacuum field depending on the discrete number of Planck-scale voxels populating each screening surface.

This framework establishes a direct connection between quantum field correlations and spacetime geometry through Einstein field equations, where electromagnetic vacuum energy density directly induces metric curvature via spacetime elasticity sufficient to generate self-gravitating solutions. Analysis of the "first screening" reveals that black hole formation represents a fundamental quantum-gravitational process operational at subatomic scales, not merely an accretion phenomenon. The local energy density of zero-point fluctuations exceeds the critical threshold for gravitational self-collapse at the proton’s reduced Compton horizon, inducing a Kerr–Newman black hole configuration bounded by a semi-permeable horizon. This self-confinement mechanism—arising from coupling between quantum vacuum stress–energy and spacetime curvature—demonstrates that coherent vacuum modes inevitably generate black-hole-like geometries without conventional matter accretion.

This approach unifies nuclear-scale physics with gravitational phenomena by re-conceptualizing both confining forces and gravity not as separate fundamental interactions but as emergent manifestations of fundamentally gravitational phenomena governed by underlying spacetime curvature resolving Einstein-Rosen’s attempt at geometrizing particles and forces at the quantum scale [

26]. This framework reveals that what appears as the strong force at nuclear distances is actually an extreme gravitational effect arising from quantum vacuum-induced spacetime geometry. Zero-temperature black-body coherence and quantum foam serve as source terms for curvature at both Planck and hadronic scales. This establishes an energetic equilibrium where mass-energy generated through coherent electromagnetic correlations within the proton precisely compensates for Hawking radiation emitted at the charge radius boundary. Such equilibrium confers extraordinary stability to the proton through a self-regulating dynamical system, while dissolving the traditional bifurcation between gravitational and quantum-field-theoretic descriptions—revealing black holes as natural sub-nuclear manifestations of quantum vacuum dynamics that characterize Planck-scale physics.

We propose a fundamentally different approach to mass generation and symmetry breaking. While the Standard Model incorporates numerous arbitrary parameters and struggles to integrate gravity, our approach provides a more comprehensive, predictive framework with fewer phenomenological parameters while expanding explanatory scope across multiple scales. The screening mechanism of electromagnetic quantum field fluctuations constitutes a novel bridge between quantum field theory and general relativity, connecting the smallest and largest scales through quantum vacuum geometry without requiring additional dimensions or exotic matter fields. This unification of quantum vacuum dynamics with spacetime geometry provides a conceptual foundation for understanding mass generation and confinement as emergent phenomena from the most fundamental structures of physical reality—revealing the proton not merely as a constituent of matter, but as a quantum resonance structure embodying the fundamental principles of spacetime itself.