Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

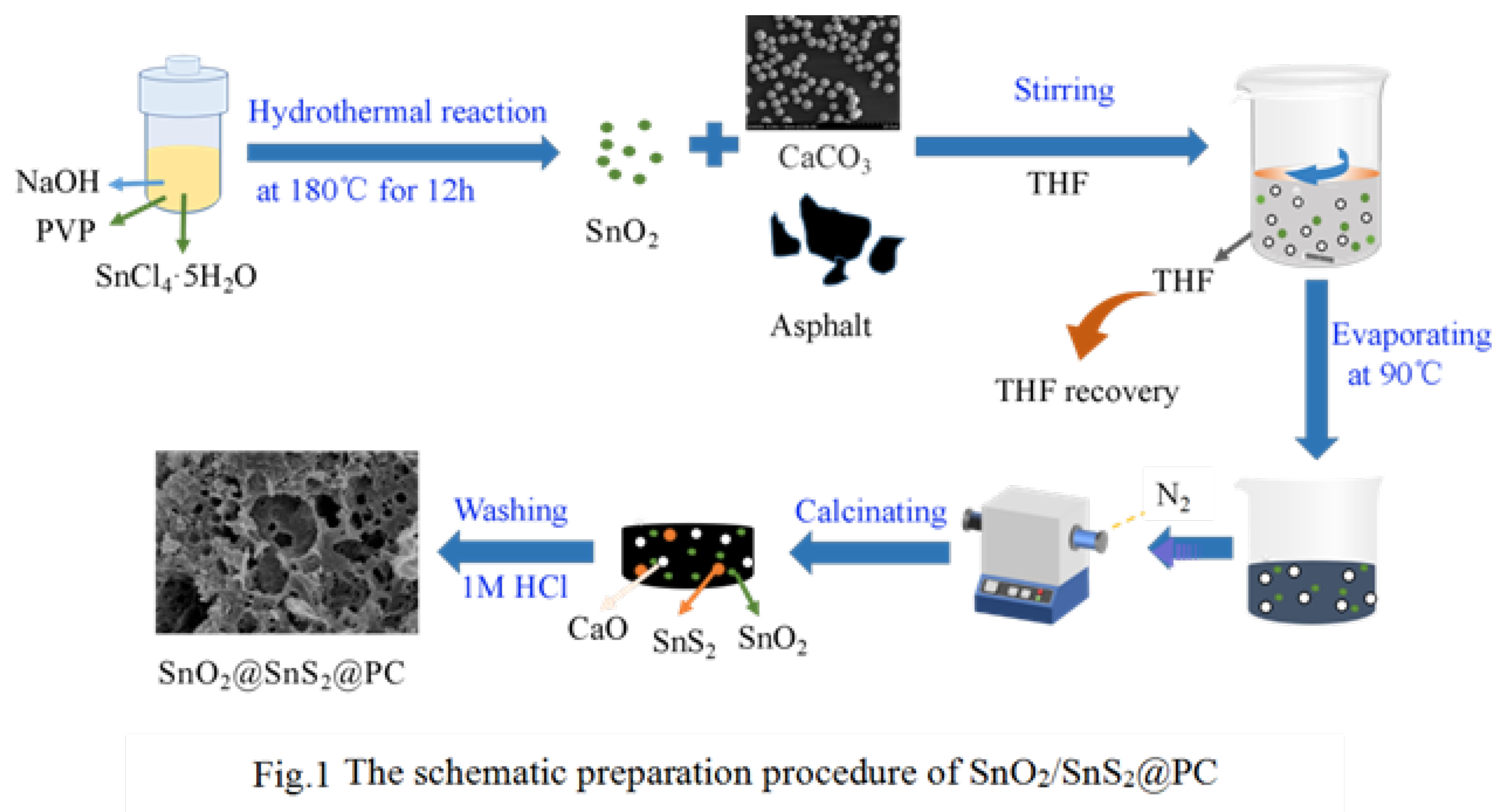

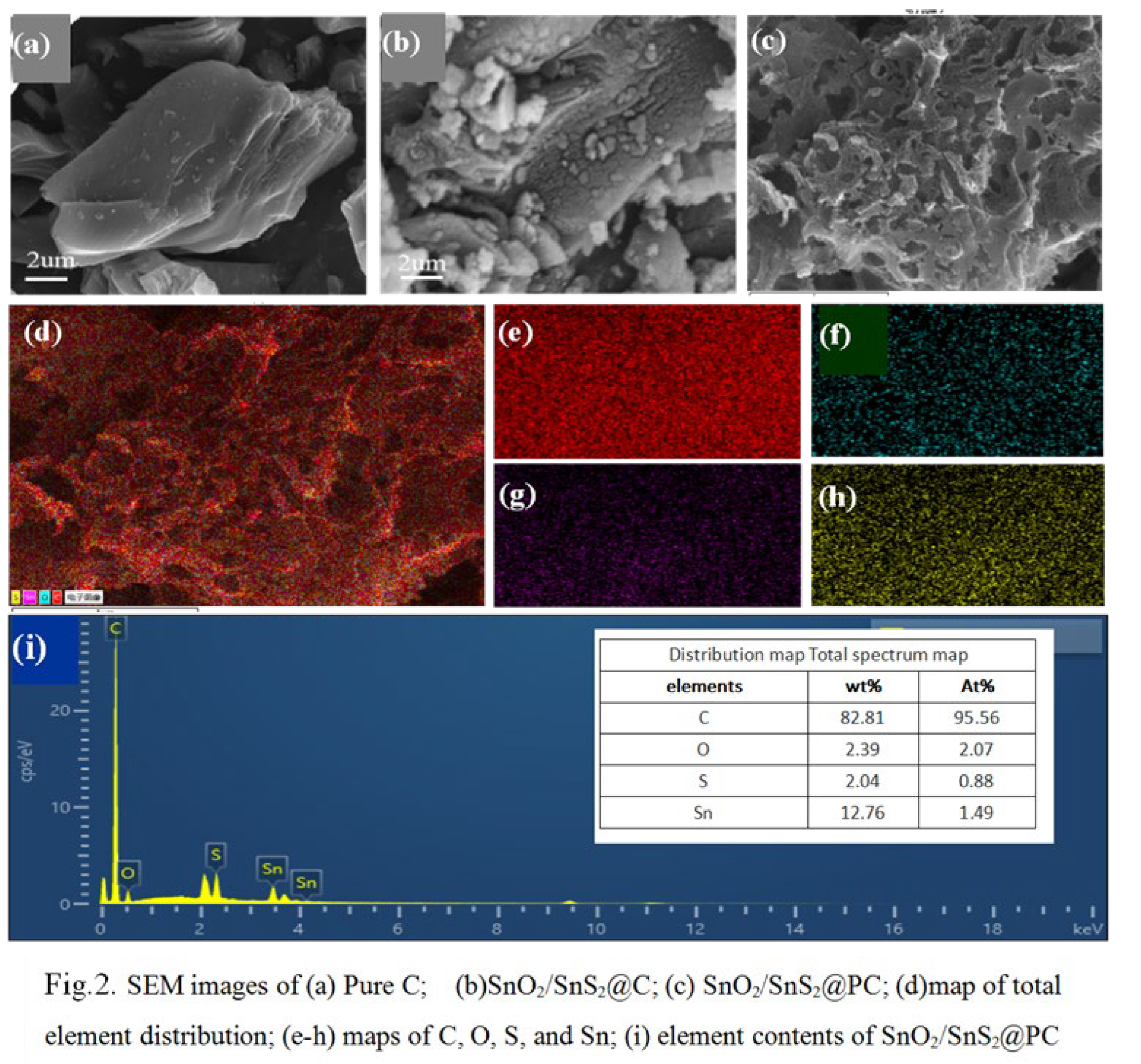

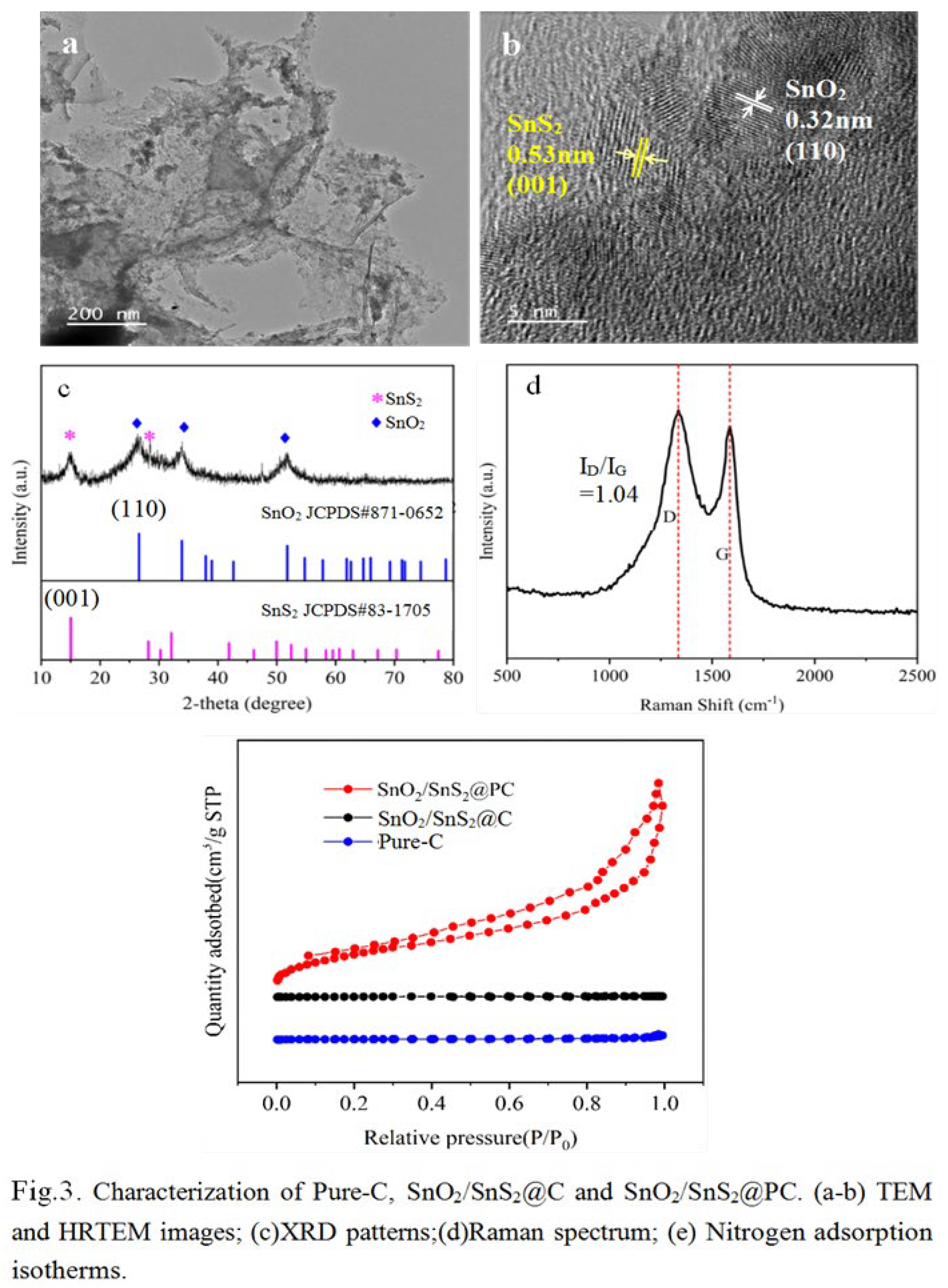

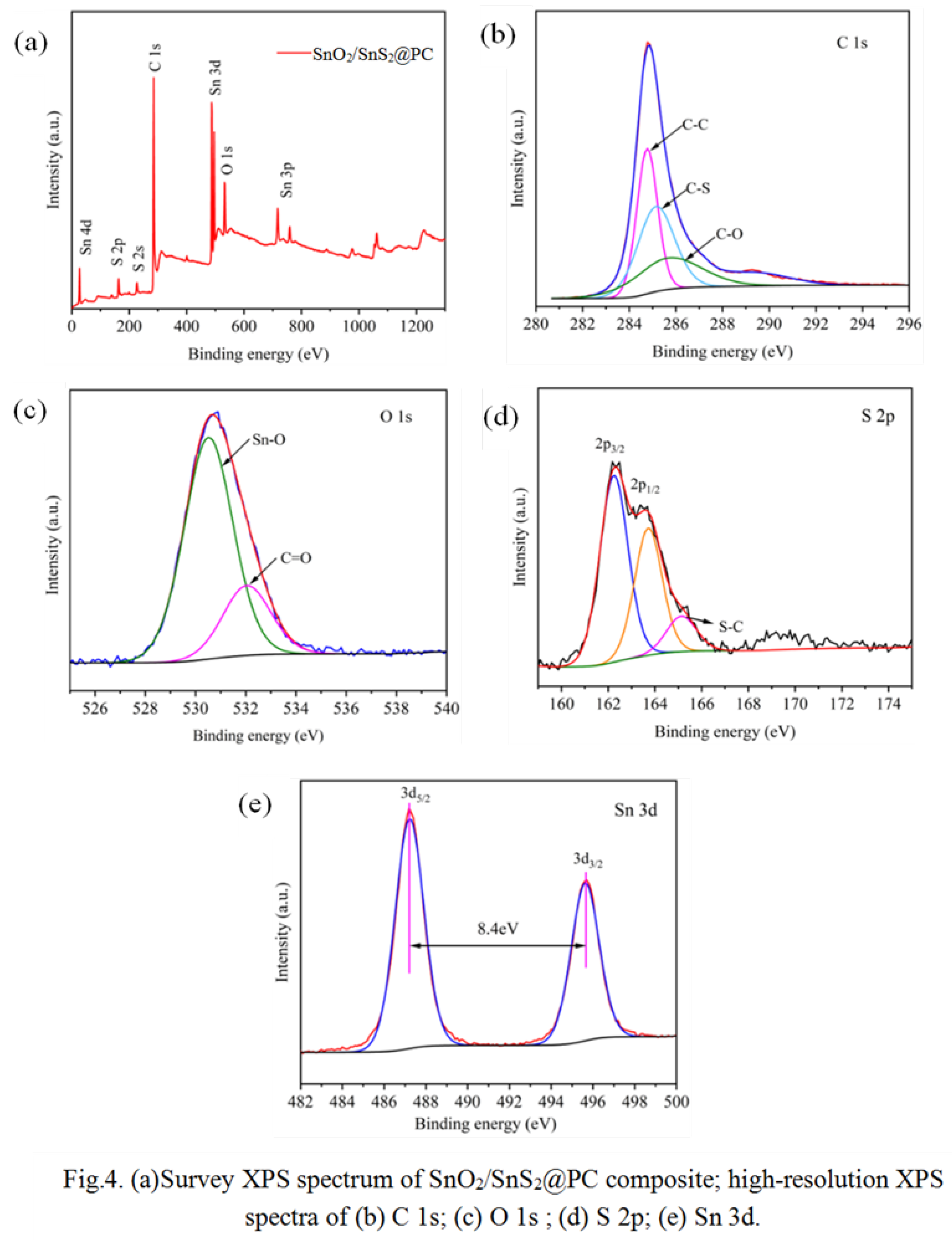

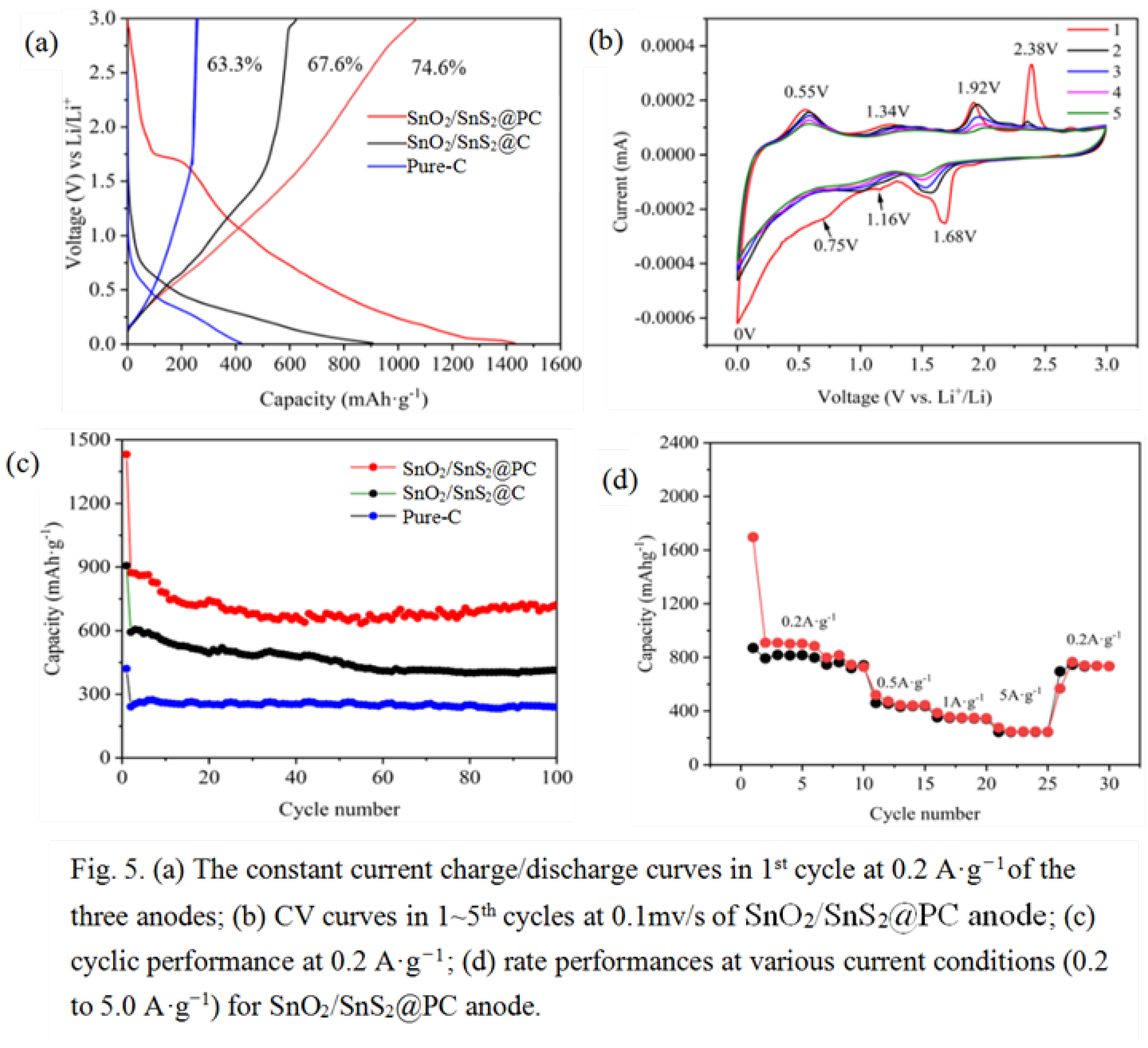

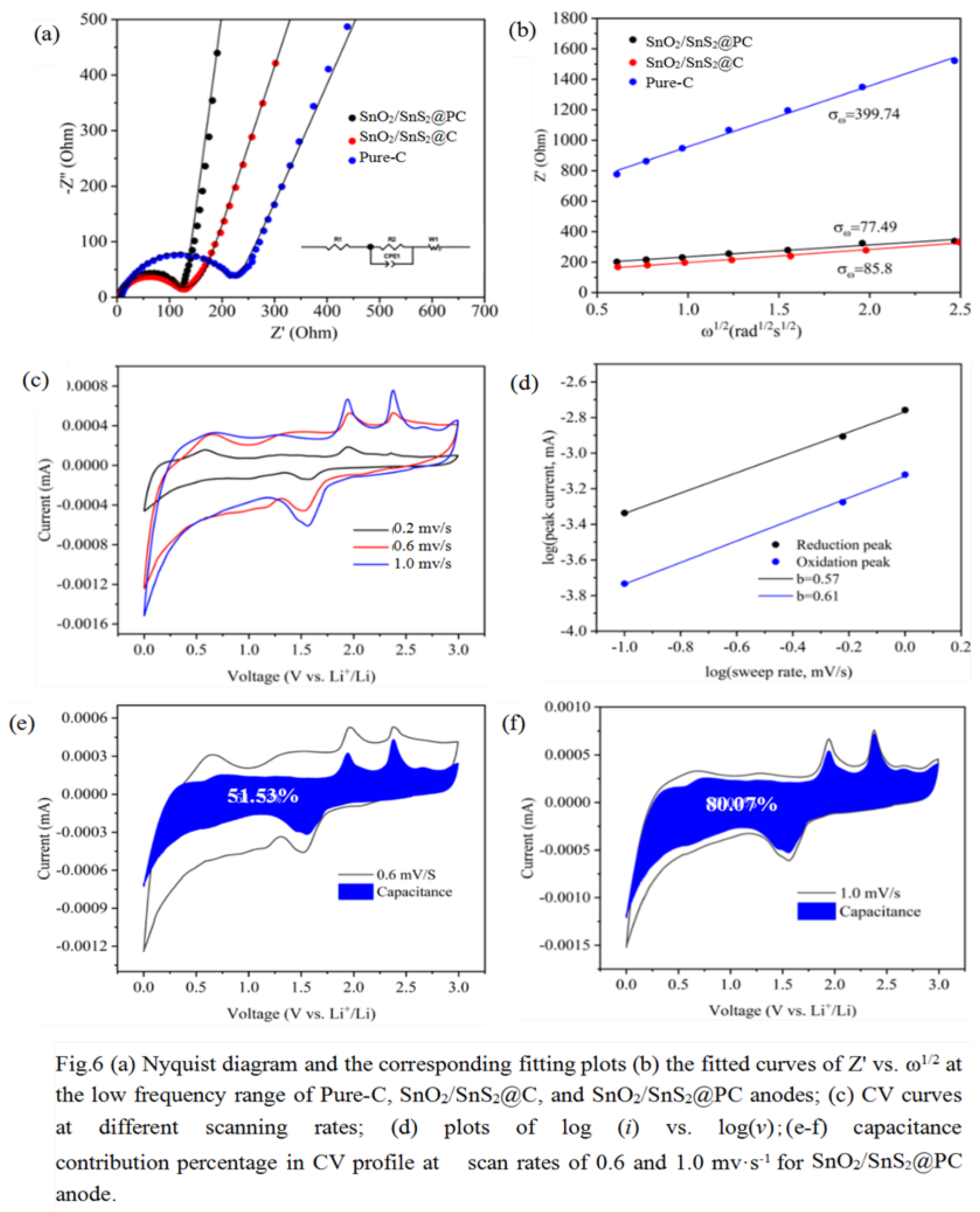

Tin-based materials have emerged as promising anode candidates for advanced lithium-ion batteries(LIBs) due to their high theoretical capacity (e.g. 994 mAh/g for Li₄.₄Sn), moderate operating potential, and natural abundance. However, Tin-based materials suffer from severe volumeexpansion (>300%) and rapid capacity during cycling. In this work, a composite composed of tin-based materials and porous carbon (PC), i.e. SnO2/SnS2@PC, was in-situ synthesized to mitigate these challenges. The composite was obtained by high-temperature calcination of a mixture containing SnO2, pe troleum asphalt and calcium carbonate, where petroleum asphalt acted as the carbon and sulfur resource, calcium carbonate acted as a pore-forming template. The prepared SnO2/SnS2@PC composite possed a specific surface area of 190.5 m2·g-1 with total pore volume 0.386 cm3·g-1, and delivered an initial specific capacity of 1431 mAh·g-1 and retained 722 mAh·g-1 at 100th cycle at 0.2 A·g−1, which is nearly three folds that of the actual capacity(~260 mAh/g) of commercial graphite and thus shows a promising application in next-generation LIBs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Synthesis of SnO2/SnS2@PC Composite

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results

Electrochemical Properties of SnO2/SnS2@PC Composite

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.; Bao, Z.; Cui, Y.; Dufek, E.J.; Goodenough, J.B.; Khalifah, P.; Li, Q.; Liaw, B.Y.; Liu, P.; Manthiram, A.; et al. Pathways for practical high-energy long-cycling lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, B.; Kamath, H.; Tarascon, J.-M. Electrical Energy Storage for the Grid: A Battery of Choices. Science 2011, 334, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Ren, D.; Wang, L.; He, X. Graphite as anode materials: Fundamental mechanism, recent progress and advances. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 36, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, N.S.; Lalwani, S.; Hong, S.; Choi, D.S.; Kim, J.-K.; AlMarzooqi, F. Nanocarbon materials for lithium-ion battery anodes: Review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Kim, H.; Myung, S.-T.; Sun, Y.-K. Diverting Exploration of Silicon Anode into Practical Way: A Review Focused on Silicon-Graphite Composite for Lithium Ion Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35, 550–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.L. , Zhou J. , Li YG., Recent advances in black-phosphorus-based materials for electrochemical energy storage. Mater. Today, 2021, 42, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Qu, C.; Wen, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, G.; Sun, H.; Xu, S. Progress of transition metal sulfides used as lithium-ion battery anodes. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 2779–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. , Kim, J. , H, Y. et al. Synergistic effect of graphene nano perforation on the reversibility of the conversion reaction of a SnO2/nano perforated graphene composite. Chem. Eng. J, 2021, 417, 128542. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; An, T.; Ding, Z.; Yu, W.; Tong, H. Heterostructured SnO2-SnS2@C Embedded in Nitrogen-Doped Graphene as a Robust Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syum, Z.; Venugopal, B.; Sabbah, A.; Billo, T.; Chou, T.-C.; Wu, H.-L.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, K.-H. Superior lithium-ion storage performance of hierarchical tin disulfide and carbon nanotube-carbon cloth composites. J. Power Sources 2021, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Shi, B.; Guo, L.; Huang, J. In-situ liquid-phase transformation of SnS2/CNTs composite from SnO2/CNTs for high performance lithium-ion battery anode. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin SL, Xu X, Zhang C, et al. The elaborate interface design of SnS2/SnO2@C/rGO nanocomposite as a high-performance anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta, 2020, 349, 136369.

- Hassan A S, Moyer K, Ramachandran B R, et al. Comparison of storage mechanisms in RuO2, SnO2, and SnS2 for lithium-ion battery anode materials. J.Phys. Chem., 2016, 120, 2036–2046.

- Li, R.; Miao, C.; Yu, L.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, W. Novel self-assembled SnO2@SnS2 hybrid microspheres as potential anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2020, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, J. Construction of uniform SnS2/ZnS heterostructure nanosheets embedded in graphene for advanced lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M. and Mauger, A. Fabrication of Li4Ti5O12(LTO) as anode material for Li-ion batteries. Micromachines, 2024, 15, 310. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathi, B. , Thillai G. , Senthamaraikannan, et.al.. Hierarchically nanofibers embedded with NiMnS nanocrystals as anode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries: Experimental and theoretical studies. Chem.Eng. J., 2024, 481, 148578. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, S.T. , Mia R. , Mahmud S. S. S., et al. Recent developments of Tin (II) sulfide/carbon composites for achieving high-performance lithium-ion batteries: A Critical Review. Nanomater., 2022, 12, 1246. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, P.; Zheng, S.; Tang, H.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, L.; Cao, S.; Xue, H.; Pang, H. Transition Metal Sulfides Based on Graphene for Electrochemical Energy Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L B, Hu X L. Recent advances in porous carbons for electrochemical energy storage. Chemistry-an Asian J., 2018, 13, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LiY, Yang W, Tu Z. Q, et al. In-situ bonding with sulfur in petroleum pitch to synthesize transition metal (Mn, Mo, Fe, or Co)-based/carbon composites for superior lithium storage. Carbon, 2021, 182, 700–710.

- Xing, B.; Zeng, H.; Huang, G.; Jia, J.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Q.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, B. Magnesium citrate induced growth of noodle-like porous graphitic carbons from coal tar pitch for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 2021, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivazhagan, M.; K. , S.N.; Nallathamby, K. Demonstration of Biocarbon-Added NiS Porous Nanospheres as a Potential Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 8991–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Hu, H.; Teng, X.-L.; Zhu, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Chao, H.-X.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.-S.; Wu, M.-B. Templating synthesis of porous carbons for energy-related applications: A review. New Carbon Mater. 2022, 37, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Huang, G.; Guo, H.; Cao, J.; Cao, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z. Green synthesis of porous graphitic carbons from coal tar pitch templated by nano-CaCO3 for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 795, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Yang, H.; Yu, K.; Jin, W. Sunflower seed husk-derived submicron carbon spheres and SnO2 nanoparticles composite used as an anode for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Ma, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, M.; Liao, L.; Rujiralai, T.; Xu, L. In-situ coupling SnS with nitrogen-doped porous carbon for boosting Li-storage in lithium-ion battery and capacitor. Electrochimica Acta 2021, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Dai, Q.; Wu, Q.; Ren, H.; Lu, X.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Joo, S.W. Preparation of hollow SnO2@N-C nanospheres for high performance lithium-ion battery. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao X L, Tang Z H, Meng M, et al. Synthesis of crumpled SnO2/rGO nanocomposites with 2D-in-3D structure and high performance. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2020, 253, 123298.

- Zhang, R.; Fang, T.; Ni, L.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Xie, A.; Lao, L. SnO2/Bi2O3/NF heterojunction with ordered macro/meso-pore structure as an advanced binder-free anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Li, K.; Lin, Z.; Song, H.; Jiang, T.; Wu, J.; Shi, Y. Fabrication of a reversible SnS2/RGO nanocomposite for high performance lithium storage. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 32414–32421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-S.; Meng, W.-J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, C.-J.; Zhao, D.-L. Nanoplates-assembled SnS2 nanoflowers with carbon coating anchored on reduced graphene oxide for high performance Li-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, H.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, F.; Wang, R.; Xie, P.; Xu, J. Expanded graphite confined SnO2 as anode for lithium ion batteries with low average working potential and enhanced rate capability. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 107, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, M.L.; Praneetha, S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Aravindan, V. Next-generation Li-ion capacitor with high energy and high power by limiting alloying-intercalation process using SnO2@Graphite composite as battery type electrode. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2022, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.W. , Kun F. , Zou Z., et al. Enhanced Li storage through highly hybridized networks of self-assembled SnS2/rGO aerogels. J.Alloys Comp., 2020, 828, 154192. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Lin K. , Qin X., et.al. A nanoscale interlayer void design enabling high-performance SnO2-carbon anodes. Carbon, 2021, 183, 486–494. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. , Guo S. , Zhang P., et al. Polypyrrole-wrapped SnS2 vertical nanosheet arrays grown on three-dimensional nitrogen-doped porous graphene for high-performance lithium and sodium storage. ACS Applied Energy Mater., 2021, 4, 11101–11111. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.F. , Wang M. , Jia P., et,al. N-graphene motivated SnO2@SnS2 heterostructure quantum dots for high-performance lithium/sodium storage. Energy Storage Mater., 2019, 20, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Y. , Wei Z. , Qing Y., et al. The fabrication of hierarchical porous nano-SnO2@carbon@humic acid ternary composite for enhanced capacity and stability as anode material for lithium-ion battery. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2022, 650, 129560. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W. , Xie Z. , Cui X, et al. Hierarchical graphene-encapsulated hollow SnO2@SnS2 nanostructures with enhanced lithium storage capability. ACS Appl Mater Interface., 2015, 7, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Pan, Q.; Gong, F.; Li, C. The facile mechanical stripping of black phosphorus and hybriding with graphite to improve the performance of graphite–based anode material for lithium ion battery. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. , Shi D. , Yang M., et.al. Novel designed MnS-MoS2 heterostructure for fast and stable Li/Na storage: insights into the advanced mechanism attributed to phase engineering, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2007132. [Google Scholar]

| Scheme 2. | STotal (m2·g-1) |

SMic (m2·g-1) |

SMec (m2·g-1) |

VMac (cm3·g-1) |

VMec (cm3·g-1) |

VTotal (cm3·g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure-C | 2.3 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SnO2/SnS2@C | 3.0 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| SnO2/SnS2@PC | 190.5 | 17.3 | 173.2 | 0.006 | 0.380 | 0.386 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).