Submitted:

08 October 2023

Posted:

08 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. Synthesis of Ni-LDH

2.2.2. Synthesis of Fe-LDH

2.2.3. Synthesis of NiFe-LDH

2.2.4. Synthesis of NiFe-LDH@CNT

2.3. Structural Characterizations

2.4. Electrochemical Characterizations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Structural Characterizations

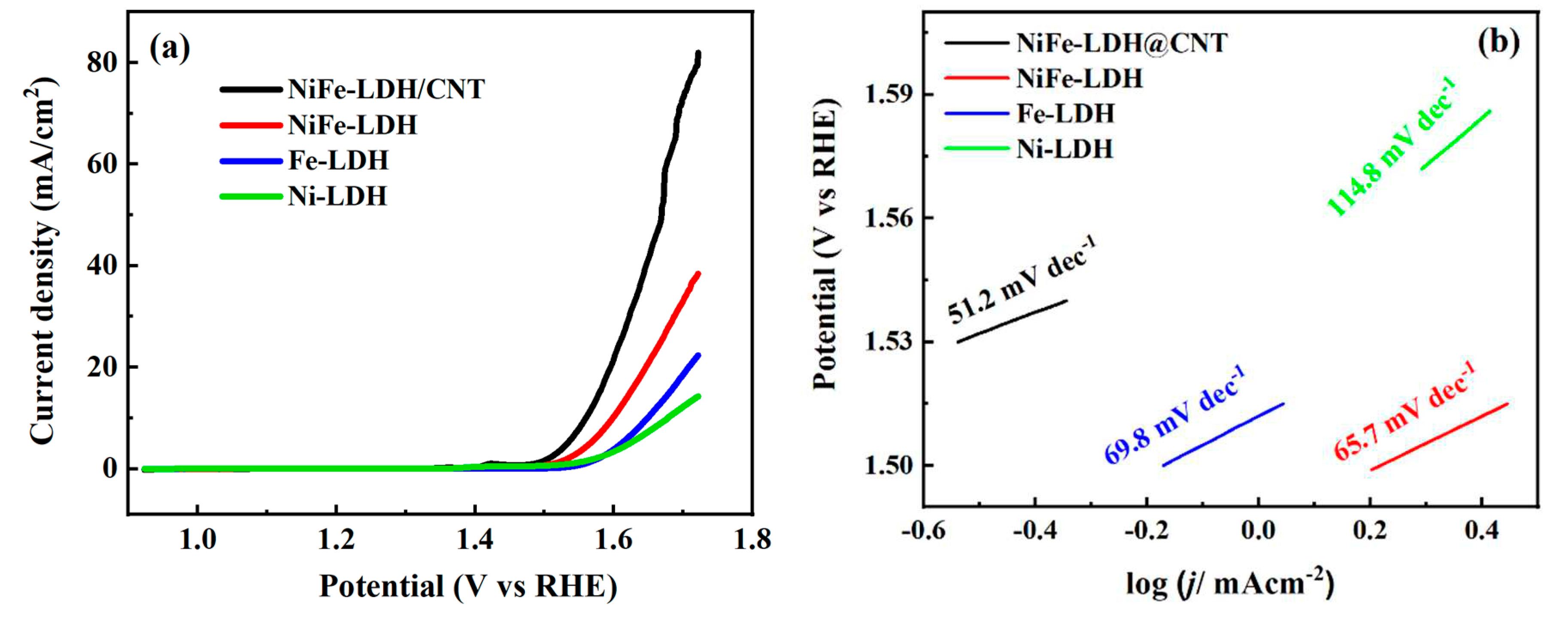

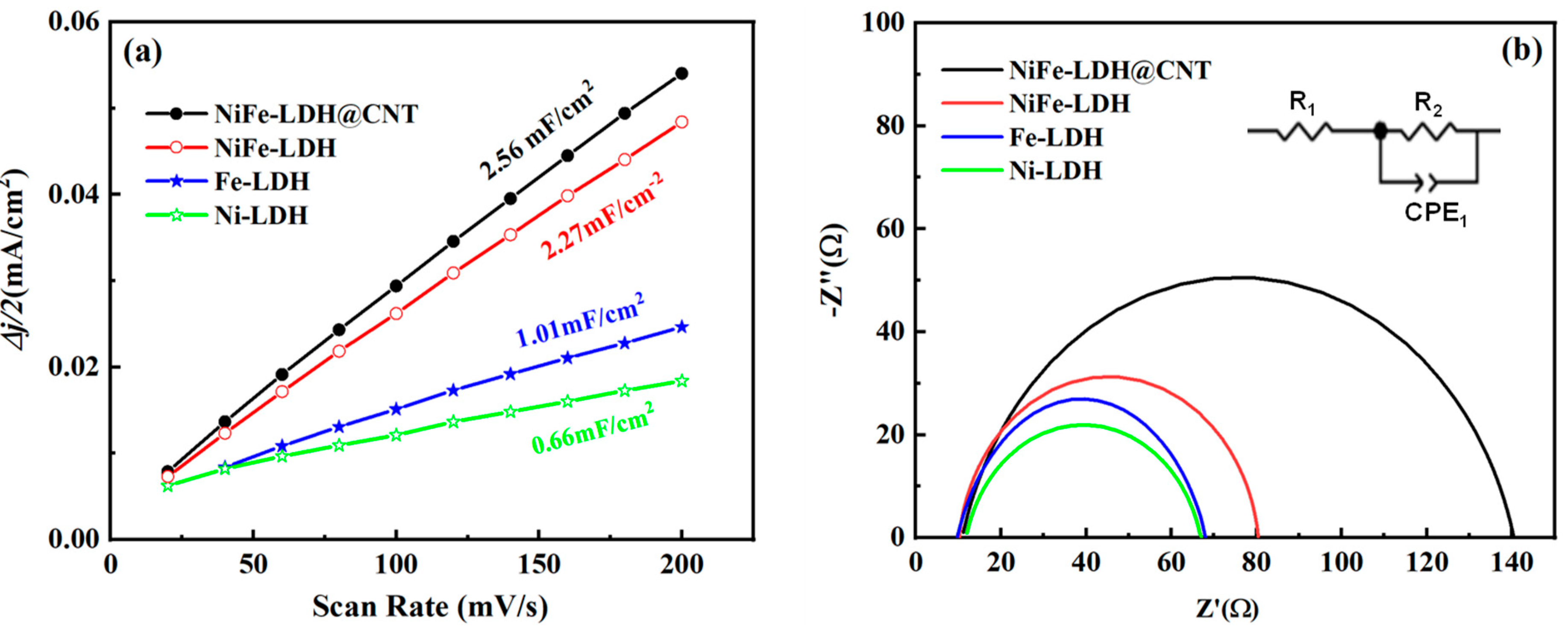

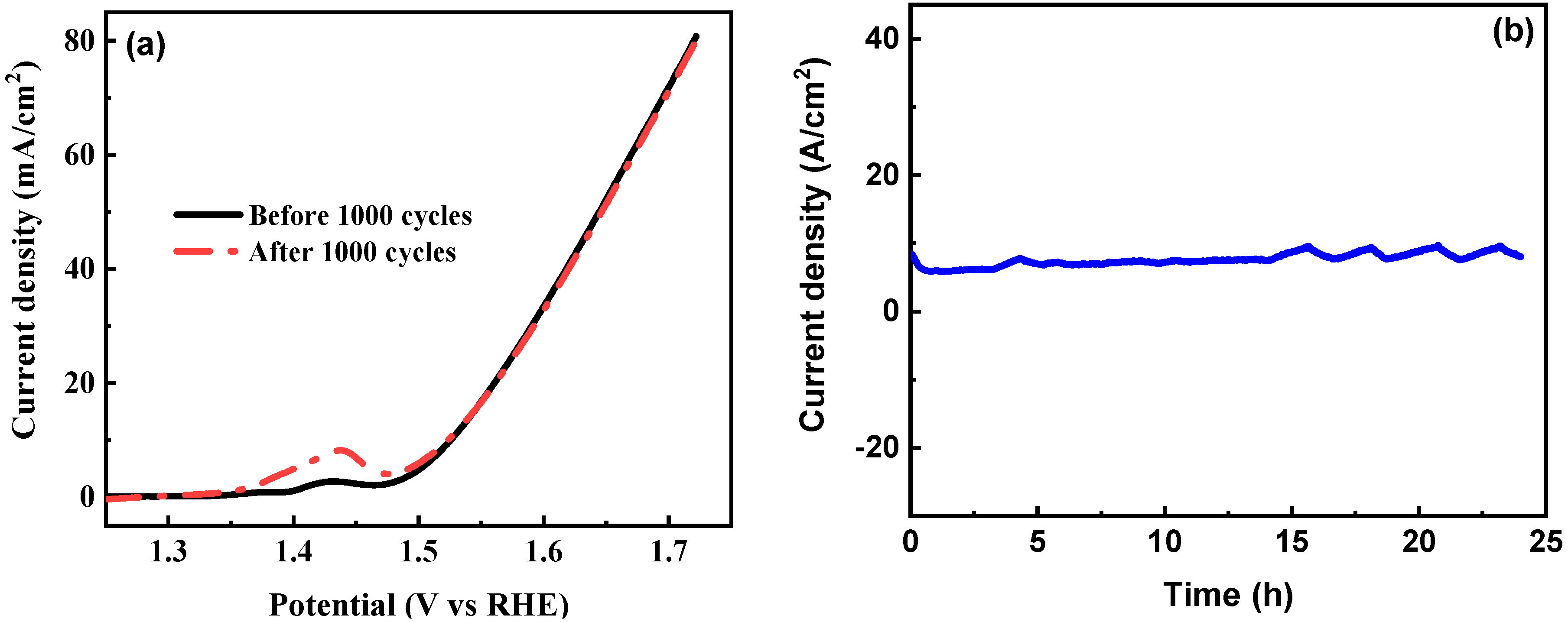

3.2. Oxygen Evolution Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Srinivas, K.; Wang, X.; Su, Z.; Yu, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, F.; Yang, D.; Chen, Y. Self-assembled CoSe2-FeSe2 heteronanoparticles along the carbon nanotube network for boosted oxygen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 9651–9658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Karthick, K.; Kumaravel, S.; Sankar, S.S.; Kundu, S. Enabling and Inducing Oxygen Vacancies in Cobalt Iron Layer Double Hydroxide via Selenization as Precatalysts for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution Reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 2023–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafpour, M.M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Manganese compounds as water oxidizing catalysts for hydrogen production via water splitting: From manganese complexes to nano-sized manganese oxides. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 8753–8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.L.; Wang, Q.F.; Choi, S.M.; Yin, Y.D. Noble-Metal-Free Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution. Small 2019, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Ganguli, A.K. FeCoNi Alloy as Noble Metal-Free Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER). ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 1630–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.M.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, T.; Fan, X.L.; Wang, J.J.; Xu, F. Recent progress in noble-metal-free electrocatalysts for alkaline oxygen evolution reaction. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.G.; Slade, R.C.T. Structural aspects of layered double hydroxides. In Layered Double Hydroxides, Duan, X., Evans, D.G., Eds. Springer-Verlag Berlin: Berlin, 2006; Vol. 119, pp. 1–87.

- Qin, X.; Teng, J.; Guo, W.Y.; Wang, L.; Xiao, S.N.; Xu, Q.J.; Min, Y.L.; Fan, J.C. Magnetic Field Enhancing OER Electrocatalysis of NiFe Layered Double Hydroxide. Catal. Lett. 2023, 153, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhong, Z.; Yan, X.M.; Kang, L.T.; Yao, J.N. Cobalt layered double hydroxide nanosheets synthesized in water-methanol solution as oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 5999–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souleymen, R.; Wang, Z.T.; Qiao, C.; Naveed, M.; Cao, C.B. Microwave-assisted synthesis of graphene-like cobalt sulfide freestanding sheets as an efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 7592–7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, C.A.; Chen, J.Y.; Chen, Q.H.; Chen, Y.T. Heterostructure of ultrafine FeOOH nanodots supported on CoAl-layered double hydroxide nanosheets as highly efficient electrocatalyst for water oxidation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 600, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Shan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Yu, X. Controllable formation of amorphous structure to improve the oxygen evolution reaction performance of a CoNi LDH. Rsc Advances 2023, 13, 2467–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.Y.; Xue, H.R.; Gong, H.; Bai, M.J.; Tang, D.M.; Ma, R.Z.; Sasaki, T. 2D Layered Double Hydroxide Nanosheets and Their Derivatives Toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.B.; Yu, C.; Han, X.T.; Yang, J.; Zhao, C.T.; Huang, H.W.; Qiu, J.S. CoMn Layered Double Hydroxides/Carbon Nanotubes Architectures as High-Performance Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, D.; Luo, D.; Song, S.; Yuan, C.; Karim, A.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Facile synthesis of nanoparticle-stacked tungsten-doped nickel iron layered double hydroxide nanosheets for boosting oxygen evolution reaction. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2020, 8, 8096–8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, C.; Han, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, C.; Huang, H.; Qiu, J. CoMn Layered Double Hydroxides/Carbon Nanotubes Architectures as High-Performance Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Xu, Z.Y.; Liu, X.A.; Mahmood, S.; Shen, J.L.; Ning, J.Q.; Li, S.; Zhong, Y.J.; Hu, Y. Integrating trifunctional Co@NC-CNTs@NiFe-LDH electrocatalysts with arrays of porous triangle carbon plates for high-power-density rechargeable Zn-air batteries and self-powered water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Phosphorous doped cobalt-iron sulfide/carbon nanotube as active and robust electrocatalysts for water splitting. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 318, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diard, J.P.; Le Gorrec, B.; Montella, C. Diffusion layer approximation under transient conditions. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2005, 584, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jin, L.; Shang, H.; Xu, H.; Shiraishi, Y.; Du, Y. Advances in engineering RuO2 electrocatalysts towards oxygen evolution reaction. Chinese Chemical Letters 2021, 32, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-H.; Liu, Z.-P. Mechanism and Tafel Lines of Electro-Oxidation of Water to Oxygen on RuO2(110). Journal of the American Chemical Society 2010, 132, 18214–18222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, S. Butler-Volmer meets microscopic reversibility. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, K.; Chen, Y.; Su, Z.; Yu, B.; Karpuraranjith, M.; Ma, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, D. Heterostructural CoFe2O4/CoO nanoparticles-embedded carbon nanotubes network for boosted overall water-splitting performance. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).