Submitted:

29 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

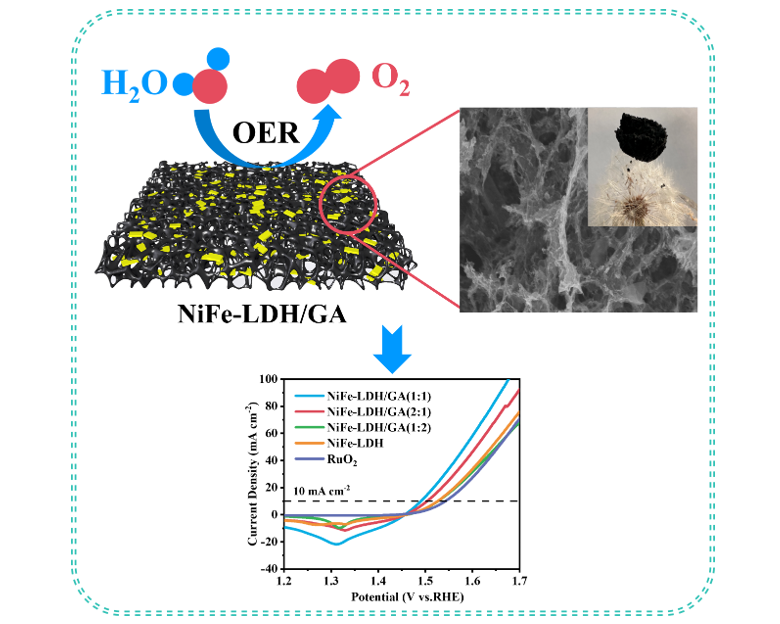

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

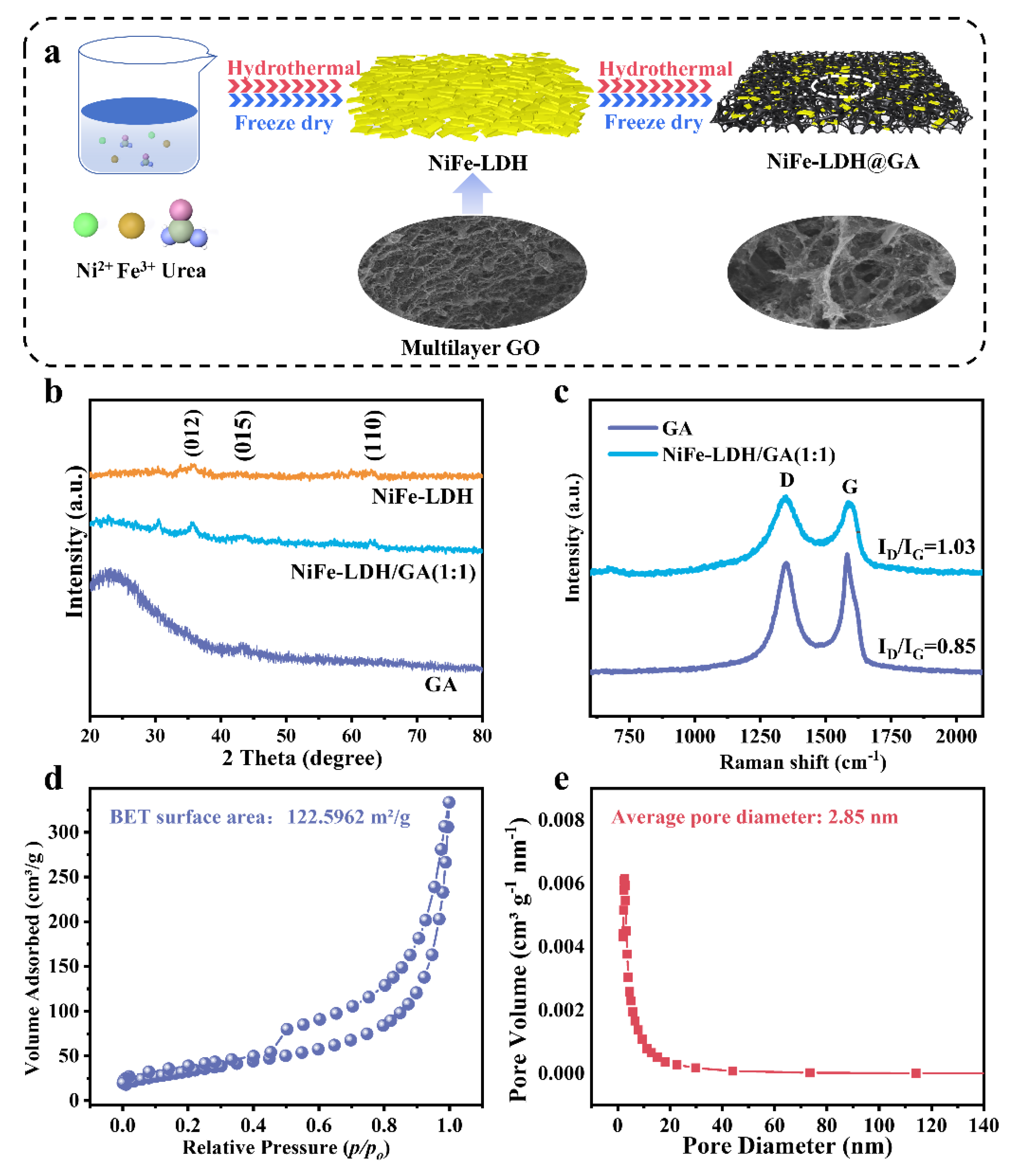

2.1. Synthesis of NiFe-LDH

2.2. Synthesis of 3D NiFe-LDH/GA

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

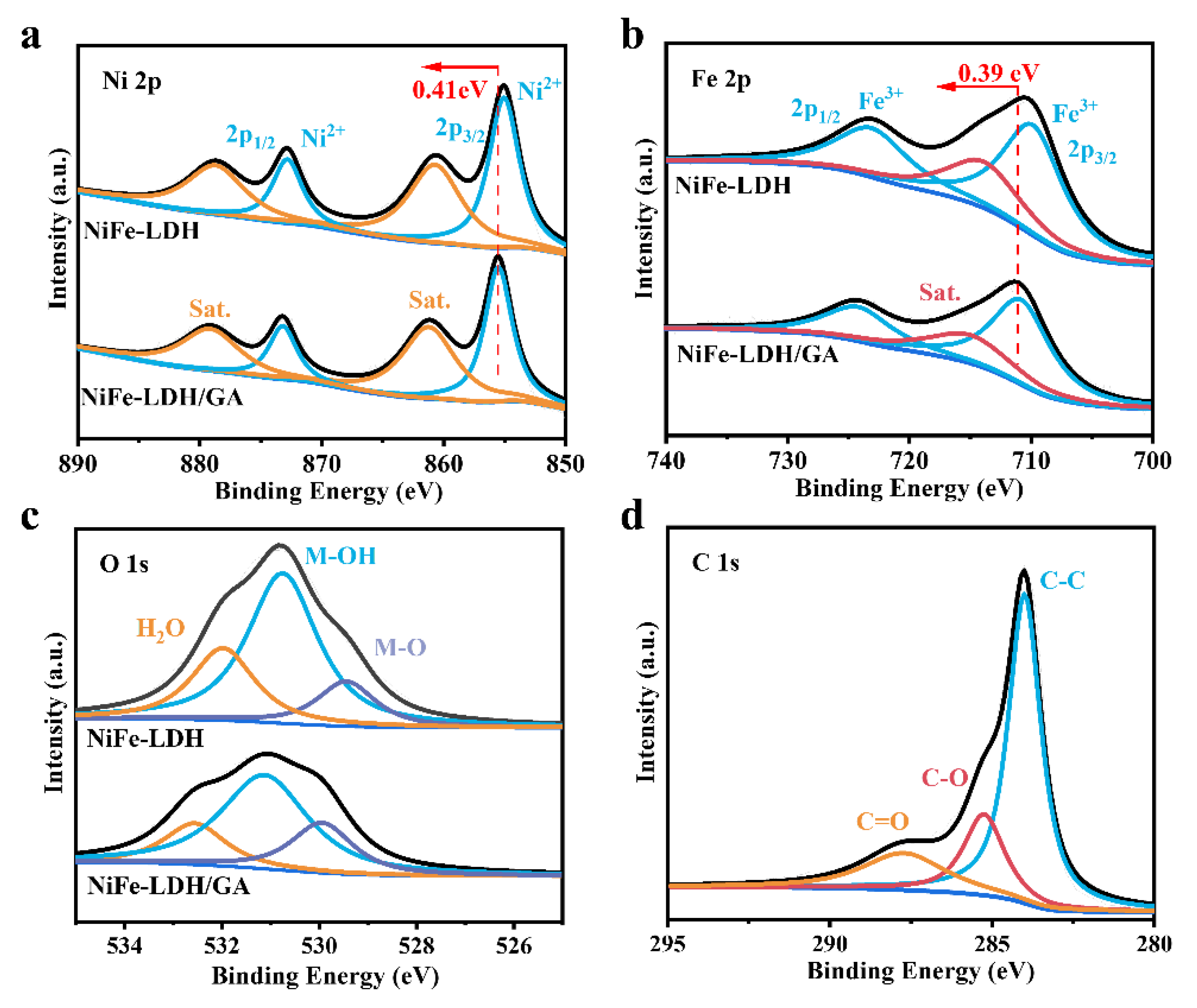

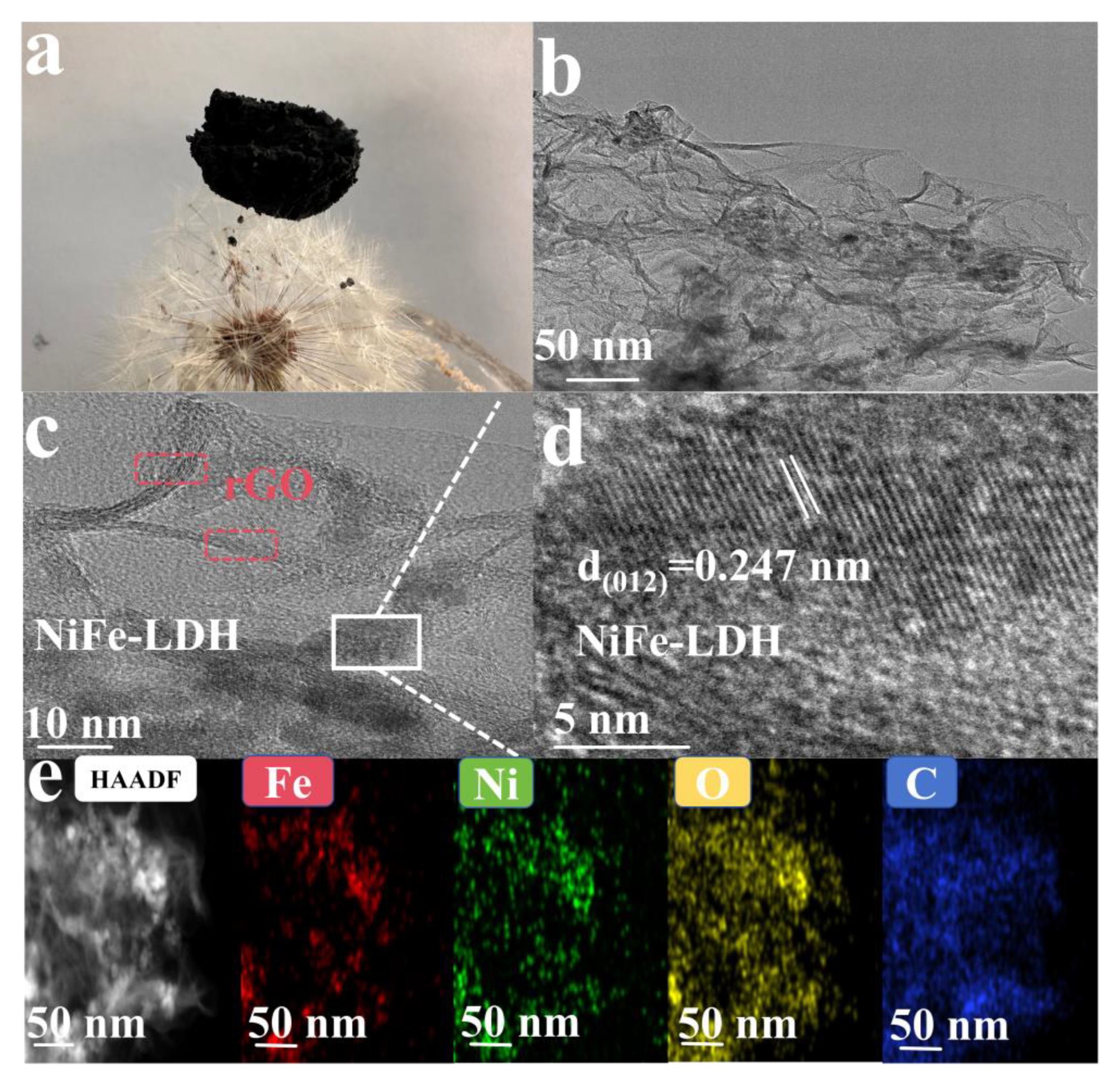

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Notes

References

- Qiu, Y.; Rao, Y. F.; Zheng, Y. N.; Hu, H.; Zhang, W. H.; Guo, X. H. Activating ruthenium dioxide via compressive strain achieving efficient multifunctional electrocatalysis for Zn-air batteries and overall water splitting. Infomat 2022, 4(9), e12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Zheng, Y. A.; Yue, S. L.; Hu, S. J.; Yuan, W. Y.; Guo, X. H. B-site substitution in NaCo1-2xFexNixF3 perovskites for efficient oxygen evolution. Inorg Chem Front 2023, 10(3), 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, J. X.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, S. Q.; Wang, W. T.; Chen, K.; Li, H. L.; Yuan, W. Y.; Qu, Y. T.; Guo, X. H. Interfacial Engineering of WN/WC Heterostructures Derived from Solid-State Synthesis: A Highly Efficient Trifunctional Electrocatalyst for ORR, OER, and HER. Adv Mater 2020, 32(7), 1905679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M. Q.; Budiyanto, E.; Tüysüz, H. Principles of Water Electrolysis and Recent Progress in Cobalt-, Nickel-, and Iron-Based Oxides for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed 2022, 61(1), e202103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K. X.; Zou, R. Q. Advanced Transition Metal-Based OER Electrocatalysts: Current Status, Opportunities, and Challenges. Small 2021, 17(37), 2100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, D.; Kim, J. Development of NiO/CoO nanohybrids catalyst with oxygen vacancy for oxygen evolution reaction enhancement in alkaline solution. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47(38), 16900–16907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D. J.; Li, P. S.; Lin, X.; McKinley, A.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, W.; Lin, W. F.; Sun, X. M.; Duan, X. Layered double hydroxide-based electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction: identification and tailoring of active sites, and superaerophobic nanoarray electrode assembly. Chem Soc Rev 2021, 50(15), 8790–8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.-D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, D.-P.; Li, W.; Li, H.-W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, X. Ultrafast Formation of Amorphous Bimetallic Hydroxide Films on 3D Conductive Sulfide Nanoarrays for Large-Current-Density Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysis. Adv Mater 2017, 29(22), 1700404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Qian, Z.; Xing, L.; Du, C.; Yin, G.; Zhao, S.; Du, L. Re-Looking into the Active Moieties of Metal X-ides (X- = Phosph-, Sulf-, Nitr-, and Carb-) Toward Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31(37), 2102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Cui, M. W.; Huang, Y. S-Doping Promotes Pyridine Nitrogen Conversion and Lattice Defects of Carbon Nitride to Enhance the Performance of Zn-Air Batteries. Acs Appl Mater Inter 2022, 14(30), 34793–34801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J.; Park, S.-K. Metal–Organic Framework-Derived Hollow CoS Nanoarray Coupled with NiFe Layered Double Hydroxides as Efficient Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Small 2022, 18(16), 2200586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, W. W.; Shao, W. J.; Bai, M. R.; Zhou, M.; Li, S.; Ma, T.; Ma, L.; Cheng, C.; Liu, X. K. Synthesis and Electronic Modulation of Nanostructured Layered Double Hydroxides for Efficient Electrochemical Oxygen Evolution. Chemsuschem 2021, 14(23), 5112–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, M.; Li, Y. G.; Wang, H. L.; Liang, Y. Y.; Wu, J. Z.; Zhou, J. G.; Wang, J.; Regier, T.; Wei, F.; Dai, H. J. An Advanced Ni-Fe Layered Double Hydroxide Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135(23), 8452–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. D.; Luo, G.; Wang, L. G.; Liu, X. K.; Qu, Y. T.; Zhou, Y. S.; Zhou, F. Y.; Li, Z. J.; Li, Y. F.; Yao, T.; Xiong, C.; Yang, B.; Yu, Z. Q.; Wu, Y. Single Ru Atoms Stabilized by Hybrid Amorphous/Crystalline FeCoNi Layered Double Hydroxide for Ultraefficient Oxygen Evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11(1), 2002816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. S.; Xiao, K. C.; Yu, C. L.; Wang, H. Q.; Li, Q. Y. Three-dimensional graphene-like carbon nanosheets coupled with MnCo-layered double hydroxides nanoflowers as efficient bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46(69), 34239–34251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y. Y.; Zhou, Y. S.; Li, R. K.; Lu, W. P.; Wang, K. K.; Liu, W. K. In situ growth of NiCoFe-layered double hydroxide through etching Ni foam matrix for highly enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47(56), 23644–23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. X.; Wang, X. Y.; Li, Z. J.; Yang, B.; Ling, M.; Gao, X.; Lu, J. G.; Shi, Q. R.; Lei, L. C.; Wu, G.; Hou, Y. Designing 3d dual transition metal electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline electrolyte: Beyond oxides. Nano Energy 2020, 77, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, Y. C.; Yu, Z. H.; Guo, S. S.; Yuan, M. W.; Yao, H. Q.; Liang, Z. P.; Lu, Y. R.; Chan, T. S.; Li, C.; Dong, H. L.; Ma, S. L. Self-supported NiFe-LDH@CoS nanosheet arrays grown on nickel foam as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 419, 129512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. L.; Miao, Y. E.; Zuo, L. Z.; Lu, H. Y.; Huang, Y. P.; Liu, T. X. Biomass-Derived Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanofiber Network: A Facile Template for Decoration of Ultrathin Nickel-Cobalt Layered Double Hydroxide Nanosheets as High-Performance Asymmetric Supercapacitor Electrode. Small 2016, 12(24), 3235–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, L. Z.; Gao, G. P.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Zhou, J. Z.; Soo, M. T.; Hong, M.; Yan, X. C.; Qian, G. R.; Zou, J.; Du, A. J.; Yao, X. D. A Heterostructure Coupling of Exfoliated Ni-Fe Hydroxide Nanosheet and Defective Graphene as a Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Adv Mater 2017, 29(17), 1700017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; He, H. Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Q. G.; Yuliarto, B.; Yamauchi, Y.; Xu, X. T.; Huang, H. J. 1D-2D hybridization: Nanoarchitectonics for grain boundary-rich platinum nanowires coupled with MXene nanosheets as efficient methanol oxidation electrocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 137932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Z.; Huang, H. J.; He, H. Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Q. G.; Li, W. H. Recent advances in MXene-based nanoarchitectures as electrode materials for future energy generation and conversion applications. Coord Chem Rev 2021, 435, 213806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y. C.; Li, J.; Luo, J.; Fu, L.; Chen, S. L. NiFe LDH nanodots anchored on 3D macro/mesoporous carbon as a high-performance ORR/OER bifunctional electrocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6(29), 14299–14306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawati, M.; Wang, Y. X.; Huang, W. H.; Wu, Y. T.; Cheng, Y. S.; Kurniawan, D.; Haw, S. C.; Chiang, W. H.; Su, W. N.; Yeh, M. H. Unraveling the efficiency of heteroatom-doped graphene quantum dots incorporated MOF-derived bimetallic layered double hydroxide towards oxygen evolution reaction. Carbon 2022, 200, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D. D.; Li, T.; Li, J. Z.; Ren, H. S.; Meng, F. B. A review of three-dimensional graphene-based aerogels: Synthesis, structure and application for microwave absorption. Composites, Part B 2021, 211, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, A. L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. J.; Liu, Y. H.; Cheng, T.; Zada, A.; Ye, F.; Deng, W. B.; Sun, Y. T.; Zhao, T. K.; Li, T. H. High-efficient adsorption for versatile adsorbates by elastic reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4 magnetic aerogels mediated by carbon nanotubes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. L.; Wei, Q. L.; Wang, Y. Y.; Dai, L. Y. Three-dimensional amine-terminated ionic liquid functionalized graphene/Pd composite aerogel as highly efficient and recyclable catalyst for the Suzuki cross-coupling reactions. Carbon 2018, 136, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z. C.; Wu, D.; Chen, G.; Zhang, N.; Wan, H.; Liu, X. H.; Ma, R. Z. Microcrystallization and lattice contraction of NiFe LDHs for enhancing water electrocatalytic oxidation. Carbon Energy 2022, 4(5), 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Y.; Han, B.; Xie, Y. L.; Liang, S. J.; Deng, H.; Lin, Z. Ultrathin Co-Co LDHs nanosheets assembled vertically on MXene: 3D nanoarrays for boosted visible-light-driven CO reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 391, 123519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H.; Ko, Y. I.; Lee, S. Y.; Lee, Y. S.; Kim, S. K.; Kim, Y. A.; Yang, C. M. Ni-Co layered double hydroxide coated on microsphere nanocomposite of graphene oxide and single-walled carbon nanohorns as supercapacitor electrode material. Int J Energy Res 2022, 46(15), 23564–23577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linghu, W. S.; Yang, H.; Sun, Y. X.; Sheng, G. D.; Huang, Y. Y. One-Pot Synthesis of LDH/GO Composites as Highly Effective Adsorbents for Decontamination of U(VI). Acs Sustain Chem Eng 2017, 5(6), 5608–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. J.; Song, M. L.; Huang, Y. C.; Dong, C. L.; Li, Y. Y.; Lu, Y. X.; Zhou, B.; Wang, D. D.; Jia, J. F.; Wang, S. Y.; Wang, Y. Y. Promoting surface reconstruction of NiFe layered double hydroxides via intercalating [Cr(C2O4)3]3-for enhanced oxygen evolution. J Energy Chem 2022, 74, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.; Hu, H. S.; Liu, R. J.; Xu, Z. X.; Wang, C. B.; Feng, Y. Y. Co-NiFe layered double hydroxide nanosheets as an efficient electrocatalyst for the electrochemical evolution of oxygen. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45(16), 9368–9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Du, Z. P.; Lai, X. Y.; Lan, J. Y.; Liu, X. J.; Liao, J. Y.; Feng, Y. F.; Li, H. Synergistically modulating the electronic structure of Cr-doped FeNi LDH nanoarrays by O-vacancy and coupling of MXene for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48(5), 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P. Q.; Wu, G.; Wang, X. Q.; Liu, S. J.; Zhou, F. Y.; Dai, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Yu, H. Q. NiCo-LDH nanosheets strongly coupled with GO-CNTs as a hybrid electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Research 2021, 14(12), 4783–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. F.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P. Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Q. G.; He, H. Y.; Huang, H. J. Holey MXene nanosheets intimately coupled with ultrathin Ni-Fe layered double hydroxides for boosted hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Carbon 2023, 212, 118141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C. W.; Jin, J.; Wei, X. Y.; Chen, S. Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, T. L.; Qu, H. X. Inducing the SnO based electron transport layer into NiFe LDH/NF as efficient catalyst for OER and methanol oxidation reaction. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Chen, H.; Ji, Y. F.; Huang, H.; Claesson, P. M.; Daniel, Q.; Philippe, B.; Rensmo, H.; Li, F. S.; Luo, Y.; Sun, L. C. Nickel-vanadium monolayer double hydroxide for efficient electrochemical water oxidation. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. N.; Yu, W. L.; Cao, Y. N.; Zhao, J.; Dong, B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, F. L.; Fan, R. Y.; Zhou, Y. L.; Chai, Y. M. S-doped nickel-iron hydroxides synthesized by room-temperature electrochemical activation for efficient oxygen evolution. Appl. Catal., B 2021, 292, 120150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, P.; Sun, J. M. Promoting electrocatalytic water oxidation through tungsten-modulated oxygen vacancies on hierarchical FeNi-layered double hydroxide. Nano Energy 2021, 80, 105540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Z.; Liu, L.; Qin, W. J.; Liu, S. J.; Tu, J. P.; Qin, Y. P.; Liu, J. F.; Wu, H. Y.; Zhang, D. Y.; Chu, A. M.; Jia, B. R.; Qu, X. H.; Qin, M. L. Mesoporous Single Crystals with Fe-Rich Skin for Ultralow Overpotential in Oxygen Evolution Catalysis. Adv Mater 2022, 34(20), 2200088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).