Introduction

The ability to accurately insert new genetic information into a specific location within the plant genome represents the pinnacle of crop biotechnology. Since the 1980s, genetic engineering has transformed agriculture, primarily through targeted insertion of genetic material (

Figure 1), achieving novel traits unattainable by conventional breeding [

1]. This foundational approach, encompassing transgenesis and cisgenesis/intragenesis, demonstrated the immense potential of genetic modification [

2,

3,

4]. However, the unpredictable nature of random insertion of foreign DNA fragments frequently causes undesired outcomes, such as multiple insertion sites [

5,

6], transgene silencing, and unstable expression [

7,

8] or rarer phenomena like epigenetic suppression [

9] or large-scale chromosome rearrangement [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], fundamentally limiting its precision and reliability.

To overcome the limitations of random DNA integration methods, a precise DNA integration method called site-specific recombination was developed using recombinases like Cre and FLP [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This method requires a pre-existing recombination landing site within the plant genome for DNA sequence exchange with donors carrying transgenes, catalyzed by a recombinase. So far, there has been a limited number of reports showing efficient and routine applications of recombinase-based DNA insertion in plants [

19,

24,

25]. Alternatively, recombinases could be used to eliminate selection markers in the random DNA insertion approaches [

17,

18,

26,

27]. This action is taken to address safety concerns and prevent regulatory issues. [

19].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of common plant transformation techniques. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation involves the introduction of transfer DNA (T-DNA) into plant cells, leading to stable integration. Particle bombardment, on the other hand, propels DNA-coated gold/tungsten particles into plant cells, resulting in random insertion of DNA into the genome. PEG-mediated protoplast transfection introduces purified DNA into isolated protoplasts, which can then regenerate into whole plants. These techniques facilitate the creation of transgenic plants from single transformed cells. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of common plant transformation techniques. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation involves the introduction of transfer DNA (T-DNA) into plant cells, leading to stable integration. Particle bombardment, on the other hand, propels DNA-coated gold/tungsten particles into plant cells, resulting in random insertion of DNA into the genome. PEG-mediated protoplast transfection introduces purified DNA into isolated protoplasts, which can then regenerate into whole plants. These techniques facilitate the creation of transgenic plants from single transformed cells. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Precise DNA integration can also be achieved through gene targeting (GT), a technique that utilizes homologous recombination (HR) to replace genomic DNA with homologous DNA donors that carry desired modifications [

28,

29,

30]. The pioneering GT work in plants was the directed integration of transgenes within a predictable site in the tobacco genome [

30]. Subsequently, GT introduced a waxy allele replacement to improve rice grain quality [

31]. However, due to the low efficiency of homologous recombination in somatic cells, the gene transfer method has seen limited applications in plants [

28,

32]. A significant breakthrough occurred when it was discovered that GT efficiency could be greatly enhanced by generating a DSB at the recombination site [

32,

33].

Recently, the invention of customizable molecular scissors such as homing nucleases (HMs) (also known as meganucleases), zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) (CRISPR-Cas) systems (

Figure 2) have revolutionized the DNA integration field by assisting GT via site-specific DSB formation [

34,

35,

36] or upgrading the precise DNA insertion tool with novel approaches such as prime editing (PE) [

37,

38,

39] for short DNA insertion [

40] and PE-recombinase-mediated large sequence insertion [

41,

42,

43,

44] (

Figure 2). More importantly, the CRISPR-Cas-based methods offer much greater accuracy and specificity of DNA insertion, enabling single-copy, site-directed insertion of DNA fragments up to kilobase scales [

41,

42,

44]. Alternatively, large DNA sequence insertion at target sites of choice could also be possible with a transposase-assisted target-site integration (TATSI) system [

45]. These methods have transformed precise DNA insertion for crop breeding, creating more opportunities for plant synthetic biology and biotechnology applications that require controllable and customizable transgene integration and expression to produce bioactive compounds in plants.

In the context of our rapidly changing technological landscape, this review synthesizes and discusses the principal methods of DNA insertion in plants. We will outline the progression from traditional, albeit imprecise, random integration techniques to the highly controlled and programmable systems introduced by the CRISPR-Cas era. Additionally, we will critically evaluate recent findings, identify ongoing challenges that hinder routine application, and explore future prospects that could make precise DNA insertion a universally applicable tool in plant science.

Random DNA Insertion

Transgenesis

Transgenesis refers to molecular techniques that introduce genetic materials, known as transgenes, from one species into another. This process allows the recipient organism to acquire traits that cannot be achieved through conventional breeding methods. The foreign genetic material may include gene expression cassettes and regulatory elements such as promoters, terminators, and genetic insulators like matrix attachment regions (MARs) [

46]. Once delivered into the cell’s nucleus, transgenes can either function temporarily or become stably integrated into the host genome, enabling long-lasting expression.

To effectively express foreign DNA, it is crucial to use delivery methods that align with the biological characteristics of the host organism. The successful introduction of foreign DNA depends on various transformation techniques. Common techniques for gene delivery include

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (AMT) [

47], particle bombardment [

48], polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation, electroporation [

49,

50], microinjection [

50], liposome-mediated transformation [

51], viral vector-mediated delivery [

52,

53], and sonoporation [

54]. Among the transformation methods used in plant systems, AMT, particle bombardment, and PEG-mediated transformation stand out due to their compatibility with plant cell structures and regeneration processes.

AMT is commonly used in dicot plants and typically involves explants such as leaf discs or callus tissues. In contrast, particle bombardment is often applied to monocots or difficult-to-transform species, utilizing tissues like immature embryos or meristems. PEG-mediated transformation is widely used for plant protoplasts, allowing for the direct uptake of DNA. The choice of transformation method largely depends on the type of plant tissue or cell being used, whether intact tissue, callus, or protoplast, as well as the species-specific regeneration protocols [

55] (

Figure 1). Plant transgenesis has enabled various biotechnological applications, including studying gene function, introducing specific traits, molecular farming, and enhancing crop production [

56,

57,

58].

In prokaryotic organisms, particularly bacteria, foreign DNA is usually introduced using plasmid vectors. These plasmids replicate independently of the host’s genome. This allows for stable gene expression without requiring integration into the genome. Additionally, because bacteria have short generation times, it is relatively easy to remove or replace these vectors [

59,

60]. In eukaryotic systems, gene expression can be classified as either transient or stable, depending on how the transgene is delivered and whether it integrates into the genome. Transient expression occurs when the DNA remains in an episomal form. This type of expression is short-lived, as it is subject to degradation or dilution during cell division. Therefore, transient expression is useful for short-term gene expression studies or functional assays. In contrast, stable expression happens when foreign DNA integrates into the genome. This integration allows for long-term expression, the creation of transgenic organisms, and heritable transmission of the traits.

The molecular mechanisms that enable the stable integration of transgenes are still under investigation. While non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) has traditionally been considered the primary pathway for this process, recent studies indicate that microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) also plays a significant role [

61,

62,

63,

64]. MMEJ may facilitate the integration of transgenes through short homologous sequences or microhomologies, ranging from 2 to 20 nucleotides. However, it lacks specificity and cannot identify the precise insertion site [

65].

Transgenesis has greatly impacted several fields, but it faces two significant challenges that restrict its wider applications. First, organisms altered through transformation are categorized as genetically modified organisms (GMOs). This classification requires a costly and lengthy evaluation process before these organisms can be released into the market or the environment. Second, conventional transgenesis techniques often rely on the endogenous DSB repair mechanisms, such as MMEJ and NHEJ, for transgene integration. This process depends on the spontaneous occurrence of double-strand breaks, making it impossible to predict or customize the site, copy number, and orientation of the inserted transgene. The randomness can lead to unintended disruptions of endogenous genes, position-effect variegation, and instability in transgene expression [

66,

67].

The significant lack of control, along with public and regulatory concerns about “foreign” DNA, not only drove the quest for genuine site-specific integration but also encouraged the exploration of alternative strategies for modifying plants using genetic material sourced from their own breeding pools.

Cisgenesis and Intragenesis

To address the regulatory and public perception challenges related to the use of “foreign” DNA in genetic engineering, two alternative approaches have emerged: cisgenesis and intragenesis. Both methods involve the insertion of DNA solely from sexually compatible species, setting them apart from transgenesis, which permits the incorporation of genes from organisms that are not closely related phylogenetically [

68]. Both techniques aim to introduce specific genetic traits from within the conventional breeding pool, but differ in how they utilize the available genetic pool [

3].

In cisgenesis, the entire gene, including its native promoter, coding region, and terminator, is transferred intact, maintaining the same sequence and orientation as in the donor organism. In intragenesis, by contrast, functional elements such as promoters, coding sequences, and terminators can be assembled, as long as they are all derived from sexually compatible species [

69]. This modularity facilitates the creation of customized gene constructs and enables the adjustment of gene expression levels, resulting in greater phenotypic variability compared to cisgenesis. These methods offer advantages over traditional breeding by allowing the introduction of targeted genetic materials without the risk of linkage drag, which can lead to the unintentional inclusion of undesirable alleles during cross-breeding [

70].

Importantly, because the inserted sequences originate from crossable species, cisgenic and intragenic plants are generally perceived as more natural and thus face less public resistance than transgenic plants. These are potentially more acceptable regarding ecological safety and potential human health impacts, which positions them more favorably under GMO regulations [

68]. This, in turn, may facilitate a more favorable path toward commercialization for such technologies. There are notable limitations to consider. The available genes for use are limited to species that can be crossed, and in the processes of cisgenesis and intragenesis, the insertion site cannot be precisely targeted. This leads to random integration of genes into the genome. Depending on where the gene is inserted, this random placement can significantly affect the organism’s gene expression. Since the DNA insertion in cisgenesis/intragenesis occurs randomly concerning both insertion site and copy number, consequently, even when the introduced gene is identical to that of the donor plants, recipient plants may exhibit variability in gene expression and silencing, potentially resulting in different phenotypes [

71,

72,

73]. For example, when multiple copies of the transfer DNA (T-DNA) integrate into the genome, gene expression levels can vary, and the orientation and position of the inserted gene may alter the expression of adjacent genes, leading to unexpected epigenetic or phenotypic effects [

74,

75]. Furthermore, when transformation is mediated by

Agrobacterium, the T-DNA border sequences remain as foreign elements flanking the inserted DNA. This undermines the ideal of introducing only native sequences in cisgenic or intragenic approaches.

Indeed, many cisgenic plants have been shown to retain T-DNA border sequences [

76,

77]. By definition, cisgenic/intragenic plants should not include sequences derived from outside the sexually compatible gene pool. Thus, strictly speaking, the presence of T-DNA border sequences means that these plants cannot be considered true cisgenic/intragenic plants. Although some studies have suggested that T-DNA border sequences can be omitted during AMT, these border sequences do not have significant effects on the plant phenotype, and T-DNA border-like sequences naturally exist in plant genomes [

78,

79,

80]. To achieve a genuine cisgenesis or intragenesis approach, additional strategies are required. This involves the development of methods to produce plants that are free from any exogenous DNA residues. Often, this includes techniques like co-transformation, followed by genetic segregation, or employing various molecular excision systems to remove unwanted DNA sequences after they have been integrated.

Several plants have been developed using cisgenesis and intragenesis approaches. The first reported cisgenic plant was an apple engineered to resist

Venturia inaequalis, the cause of apple scab [

77]. The scab resistance gene

HcrVf2, derived from the wild apple

Malus floribunda 82, was introduced into the susceptible cultivar Gala, providing enhanced resistance. Other notable examples include a marker-free potato (

Solanum tuberosum) harboring blight resistance genes Rpi-sto1 and Rpi-vnt1.1, derived from

S. stoloniferum and

S. venturii, respectively [

76]; an intragenic potato showing reduced enzymatic browning in the tubers [

81]; a cisgenic barley (

Hordeum vulgare) with enhanced grain phytase activity via introduction of a

HvPAPhya gene from a sexually compatible species [

82]; and bread wheat with constitutive expression of class I chitinase gene, resulting in increased resistance to leaf rust [

83,

84].

Some plants have incorporated genes derived from sexually compatible species, but removing antibiotic resistance markers could not be achieved. For example, several apple cultivars developed in previous studies for scab resistance [

85,

86], a grape (

Vitis vinifera) expressing the thaumatin-like protein gene that confers resistance to fungal disease [

87], as well as the Amflora potato developed by BASF Plant Science, contain antibiotic resistance genes. Since these markers are exogenous, the resulting plants are classified as transgenic GMOs rather than cisgenic/intragenic.

Overall, cisgenesis and intragenesis offer a significant improvement over traditional transgenesis by allowing for safer trait introduction without the need to cross species barriers. However, they do not address the main technical challenge of random integration, which means they still carry the same risks of position effects and unpredictable gene expression. This important limitation indicates that a genuine paradigm shift would involve not just managing the source of the inserted DNA but also mastering the specific location of its integration. This necessity paved the way for the first generation of true site-specific insertion technologies.

Pre-CRISPR-Cas Era-Based Precise DNA Insertion

The pursuit of true genomic precision began long before the advent of CRISPR-Cas. This “pre-CRISPR-Cas era,” spanning roughly from the late 1980s to 2012 [

88], was characterized by the development of foundational technologies that, while often inefficient or cumbersome, established the core principles of site-specific DNA integration. Two principal strategies dominated this period: the use of site-specific recombinases (SSRs) to catalyze DNA exchange at pre-defined “landing sites” (

Figure 3B) and the stimulation of the cell’s native HR pathway, a process that came to be known as GT.

SSRs were among the first tools used for controlled DNA integration. SSRs are categorized into two types: tyrosine recombinases (YR) and serine recombinases (SR). This classification is based on the catalytic amino acid residue that forms a covalent bond with the DNA during the recombination process [

89]. Tyrosine recombinases use identical recognition sites for bidirectional recombination, while serine recombinases recognize two distinct sites (e.g., attB and attP) and carry out unidirectional recombination [

90]. In genetic engineering, SSRs are utilized to reversibly recombine DNA sequences that are flanked by specific recombination sites, leading to the exchange of DNA sequences between donor and acceptor organisms [

4,

91]. The SSR systems, including Cre-lox, FLP-FRT, and PhiC31, were used to remove selection marker genes from transgenic plants [

17,

18,

26,

90,

92,

93,

94]. Additionally, site-specific integration of transgenes using SSRs was investigated to resolve transgene silencing issues caused by random insertion [

20,

25,

92,

95]. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of this method for de novo gene insertion was fundamentally limited by its reliance on pre-existing recombination sites within the host genome, which restricts its application to specially engineered plants.

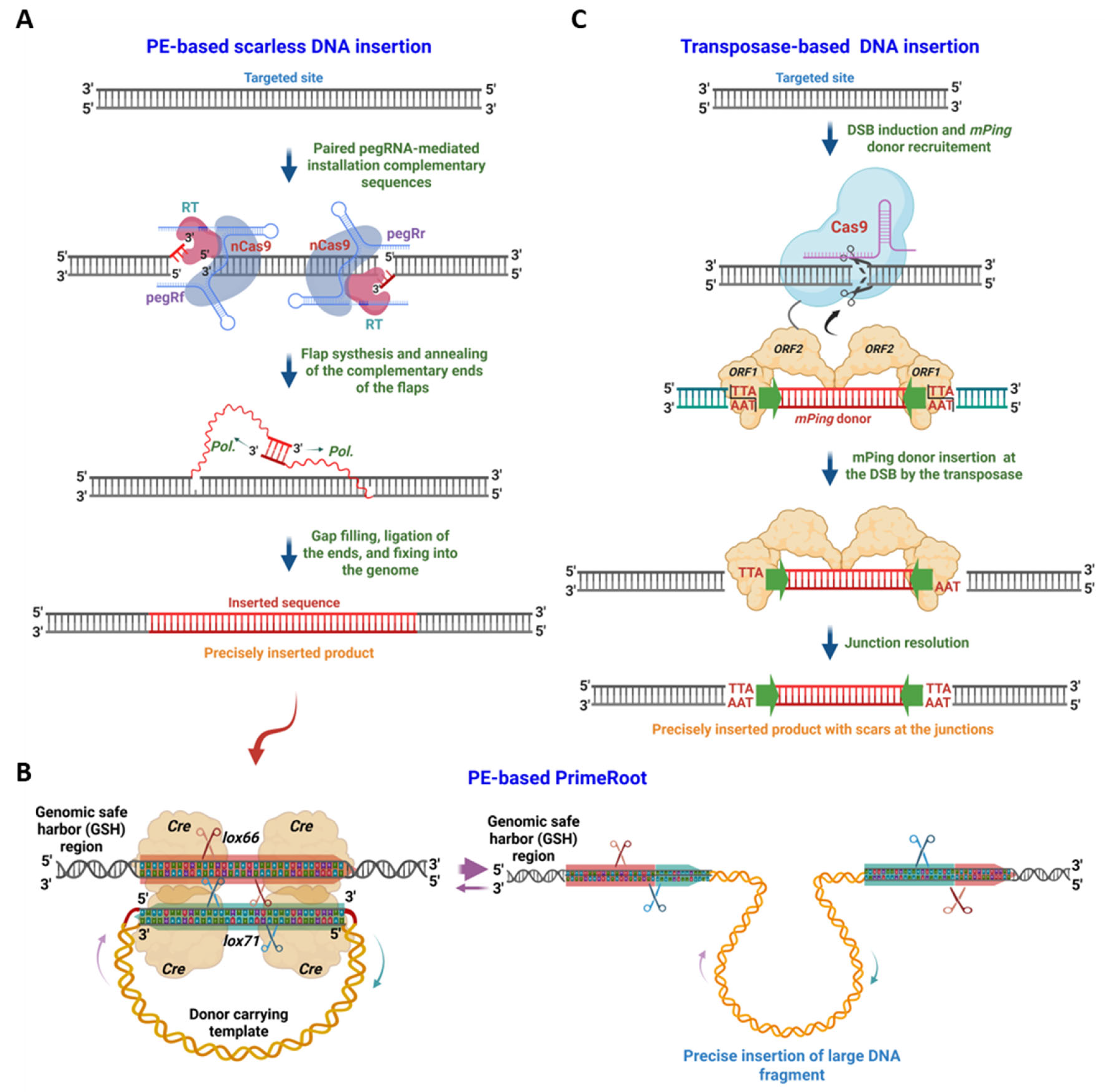

Figure 3.

PE and transposase-based DNA insertion methods. A. PE-Based DNA Insertion Methods. This revolutionary technique employs a paired pegRNA approach. The nCas9 protein nicks the non-target strand, while the RT enzyme copies genetic information from the 3′ extension of the pegRNAs, which contain the inserted nucleotides, into the nicked ends. This process forms a pair of complementary 3′ flaps that contain the desired inserted nucleotides. The annealing of these flaps allows for the seamless integration of the intended DNA sequence into the genomic site. B. PrimeRoot. The paired pegRNA approach can also be used to install a recombination site (RS), such as lox66, at a desired location, typically a genomic safe harbor (GSH). Following this, the Cre recombinase, which is co-expressed with the PE tool or later introduced to the RS-inserted cells, facilitates strand exchanges between a circularized donor DNA carrying an inserted DNA fragment and a lox77 site. This innovative strategy enables the insertion of large DNA fragments, up to kilobases in size, in plants. C. Transposase-assisted target-site integration (TATSI). In this system, a CRISPR-Cas9 or Cas12a protein is fused with the Pong transposase ORF1-ORF2 and guided by a gRNA to generate a DSB at the target site. The ORF1 binds to a mPing DNA donor, which is flanked by two 15-bp inverted repeats (indicated by green arrows) that have TTA or TAA repeats at their terminal ends, necessary for excision. The Pong transposase then excises and inserts the mPing donor (with TTA/TAA staggered ends) into the cleavage site (or within its 4-bp) created by the CRISPR-Cas protein, leaving minimal scars (usually with TTA/TAA duplication) at the junctions. This method allows for the insertion of intended DNA sequences up to several kilobases in size into the genomes of Arabidopsis and soybean using the mPing donor. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Figure 3.

PE and transposase-based DNA insertion methods. A. PE-Based DNA Insertion Methods. This revolutionary technique employs a paired pegRNA approach. The nCas9 protein nicks the non-target strand, while the RT enzyme copies genetic information from the 3′ extension of the pegRNAs, which contain the inserted nucleotides, into the nicked ends. This process forms a pair of complementary 3′ flaps that contain the desired inserted nucleotides. The annealing of these flaps allows for the seamless integration of the intended DNA sequence into the genomic site. B. PrimeRoot. The paired pegRNA approach can also be used to install a recombination site (RS), such as lox66, at a desired location, typically a genomic safe harbor (GSH). Following this, the Cre recombinase, which is co-expressed with the PE tool or later introduced to the RS-inserted cells, facilitates strand exchanges between a circularized donor DNA carrying an inserted DNA fragment and a lox77 site. This innovative strategy enables the insertion of large DNA fragments, up to kilobases in size, in plants. C. Transposase-assisted target-site integration (TATSI). In this system, a CRISPR-Cas9 or Cas12a protein is fused with the Pong transposase ORF1-ORF2 and guided by a gRNA to generate a DSB at the target site. The ORF1 binds to a mPing DNA donor, which is flanked by two 15-bp inverted repeats (indicated by green arrows) that have TTA or TAA repeats at their terminal ends, necessary for excision. The Pong transposase then excises and inserts the mPing donor (with TTA/TAA staggered ends) into the cleavage site (or within its 4-bp) created by the CRISPR-Cas protein, leaving minimal scars (usually with TTA/TAA duplication) at the junctions. This method allows for the insertion of intended DNA sequences up to several kilobases in size into the genomes of Arabidopsis and soybean using the mPing donor. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

In parallel, GT provided a more flexible approach for precise modifications by utilizing the cell’s own homologous recombination machinery to accurately insert or replace alleles using a homologous donor template [

30,

31,

33]. This was typically shown by restoring a truncated marker gene, leading to observable traits such as antibiotic resistance or fluorescence [

30,

96,

97]. However, due to its low efficiency (~10

-4), routine applications in plant breeding were limited and unpopular [

4,

34,

98].

The most critical finding of this period was the discovery that a targeted DSB at the recombination site could boost GT efficiency by several orders of magnitude, immediately highlighting the potential of site-directed nucleases. While early experiments used rare-cutting homing nucleases like I-SceI on pre-inserted recognition sites to study HR mechanics [

32,

33], the true breakthrough was the invention of programmable nucleases. The first generations of these tools, ZFNs and TALENs, were engineered proteins capable of inducing DSBs at specific genomic loci [

98,

99]. TALENs provide improved specificity and reduced cytotoxicity compared to ZFNs. They have been used to enhance plant genome editing by creating targeted DSBs in various plant species, including tobacco, tomato, barley, and rice. The editing frequency achieved was up to 3% in barley leaf cells, 6.3% in rice transformants, 9.65% in tomato calli, and 14% in tobacco protoplasts [

35,

100,

101,

102].

An efficient transformation and selection of GT cells, such as the positive-negative or allele-associated selection, facilitated the success of some cases in rice [

31,

103,

104,

105]. However, this selection system left a positive selection marker within the genome of the targeted plant. Another strategy to enhance GT in plants is modulating the HR machinery, which may enhance GT frequency at several orders of magnitude (10

-2 to 10

-1 frequency) [

106].

By the early 2010s, the field had made significant progress. The principles of precise DNA insertion were well-established, and with the use of TALENs, GT efficiencies were reaching levels suitable for practical application in major crops. However, a major bottleneck remained: the design, assembly, and validation of ZFNs and TALENs were complex, costly, and labor-intensive, which hindered their widespread adoption. As a result, there was a growing need for a new technology that could provide the same targeting capability but with much greater ease and programmability. This need would soon be spectacularly met by CRISPR-Cas.

CRISPR-Cas-Based Precise DNA Insertion in Plants

CRISPR-Cas Overview

The challenge of programming protein-based nucleases like ZFNs and TALENs was decisively overcome by the repurposing of a prokaryotic adaptive immune system: CRISPR-Cas. Initially, the CRISPR-Cas complexes were discovered as an adaptive immune system in bacteria. The first report of CRISPR arrays in 1987 in

E. coli [

107] marked the beginning of the study and understanding of CRISPR-Cas systems and their role in bacterial immunity. Bacteria store fragments of viral DNA (called spacers) in CRISPR arrays and use them as guide RNAs (gRNAs) to direct Cas proteins for sequence-specific cleavage of invading foreign DNA [

108].

The transformative breakthrough came in 2012 when researchers harnessed the CRISPR-Cas9 system from

Streptococcus pyogenes as a simple, programmable genome editing tool [

88]. By designing a guide RNA to target a complementary DNA sequence, Cas9 could induce a DSB at the desired site (

Figure 2). This DSB is the critical starting point for DNA insertion, as it is resolved by one of two major cellular repair pathways: the error-prone NHEJ pathway or the high-fidelity HR pathway. This simple, RNA-guided programmability opened the door to vast applications across biology and medicine [

109,

110].

The true versatility of CRISPR-Cas lies in its modularity. More recently, scientists have fused a deaminase with Cas9 nickase to make base editors, allowing direct conversion of single DNA bases such as C to T or A to G without inducing double-strand breaks [

111,

112]. CRISPR has also been modified to control gene activity without changing the DNA itself. Using a “dead” Cas9 (dCas9) fused with other proteins, scientists can turn genes on or off, edit epigenetic marks, or even target RNA. Most relevant to this review, the CRISPR-Cas system evolved to advanced insertion platforms like PEs and CRISPR-transposase systems.

The applications of this revolutionary technology have been rapid and widespread, impacting diverse fields such as biomedical research and agriculture. In plant biotechnology, the key promise of CRISPR-Cas is to make precise DNA insertion an efficient and routine process. In the following sections, we will examine the primary strategies developed to achieve this goal. We will explore how the CRISPR-Cas platform has been utilized to harness different cellular mechanisms for DNA insertion, starting with DSB repair pathways (NHEJ and HR), and later advancing to more sophisticated, DSB-independent systems like PE and programmable recombinases.

CRISPR-Cas-Based GT for Precise Sequence Insertion

In contrast to the direct ligation approach of NHEJ, GT represents the gold standard for scarless, high-fidelity DNA insertion, a method revitalized and made practical by CRISPR-Cas (Fauser et al., 2012; Vu et al., 2019).

Briefly, once a DSB is formed and signaled/redirected to be repaired by HR mechanism, the broken ends are first resected to generate 3′ ssDNA overhangs that can then anneal with a homologous arm of a ssDNA/dsDNA donor, and thereby trigger DNA-dependent DNA polymerization that copies the information from the donor template into the genomic site (

Figure 2). In plant somatic cells, the HR mechanism may end up with noncrossover products via synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) [

33]. Theoretically, DNA sequences of any length flanked by homologous arms can be inserted via this method, provided that they can be introduced to the target site and the HR process has been initiated. However, GT in somatic cells faces low efficiency issues as HR is dominated by the NHEJ in repairing DSBs, thereby limiting its potential in plant research and applications [

29].

A DSB was shown to be critical for the initiation and success of a GT experiment [

32]. Initially, there was no tool to introduce a DSB at a target site to initiate DSB repair, and thus, GT events were likely obtained by the random DSB formation at or near the target region [

30,

31]. Since the customizable nucleases such as ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas were invented, the GT method has entered a new era of exploitation and application [

28,

125,

126]. By integrating DNA sequences within the homologous donor, researchers could precisely insert up to several kilobases into a genome site of interest in plants via the assistance of customizable nucleases that could induce DSBs at the GT-targeted sites [

127,

128].

At the early stage, the GT experiments were mostly focused on the demonstration of the GT’s feasibility, investigation of the underlined mechanisms, and improvement of GT efficiency. Due to the low efficiency, in most GT experiments, the homologous donor template contained an antibiotic selection or fluorescent marker to enrich the GT events, and for better comparison of the GT efficiency among treatments [

34,

129]. The allele-associated marker gene can later be excised via the employment of the transposon-mediated excision mechanism [

130,

131].

The majority of the GT data were reported with monocot plants such as rice and maize via particle bombardment delivery of the editing tools. The inserted sequence length varied from a dozen to thousands of nucleotides, and with varied frequencies (

Table 1). The bombardment method helps deliver a high dose of donor templates and thus significantly enhances GT efficiency. Despite some advantages, particle bombardment has notable disadvantages, including the occurrence of random DNA breaks and chromosomal rearrangements [

13]. When high copies of donor DNA are delivered alongside DSBs, it can also result in random insertions at these break sites within the plant genome. Alternatively, GT tools could also be introduced into plant cells via the AMT system. However, compared to particle bombardment, AMT has a limitation in the number of T-DNA copies that can be delivered into plant cells [

5,

132,

133]. Therefore, the number of homologous donor templates delivered by T-DNA is also limited and becomes one of the bottlenecks in achieving high GT efficiency. GT-mediated sequence insertion efficiency was recently shown to be significantly enhanced when homologous donors were delivered and amplified by geminiviral replicon vectors [

35,

36,

134], taking advantage of the autonomous amplification capacity of the replicons. Replicon-based tools significantly enhanced GT-mediated sequence insertion efficiency in plants (

Table 1). In Arabidopsis, since a geminiviral replicon system has not been established for GT, a sequential transformation may elevate the achievement of GT plants in the T2 generation [

135].

Tethering the donor to the CRISPR-Cas complex or other donor recruitment methods to provide the homologous DNA templates for GT reactions at the target sites is another way to enhance GT efficiency. Ali and colleagues fused

Agrobacterium VirD2 relaxase to Cas9 and included phosphorothioate-modified donor DNA to anchor the repair template, achieving 8.7% efficiency in precisely inserting an HA tag at the OsHDT site, a significant improvement over untethered systems [

136]. Similarly, Nagy and coworkers combined LbCas12a with the HUH endonuclease from Faba Bean Necrotic Yellow Virus to tether single-stranded donor DNA to the CRISPR-Cas complex, boosting local donor concentration at a target site (D5) in soybean. This strategy led to site-specific integration of a 70-nt oligonucleotide donor with 3.3% precise sequence insertion efficiency, higher than 1.3% in the case of the untethered system (

Table 1) [

137]. Recently, by fusing Cas9 with a geminiviral Rep protein, Zhou and coworkers enabled covalent tethering of donor DNA via rolling-circle replicons in vivo. This method increased knock-in efficiencies 4~7.6-fold compared to Cas9 alone, achieving up to 72.2 % of T

0 rice plants carried scar-free in-frame insertions of 33~519 bp tags, transmitted faithfully and without off-target events [

138]. Though the method was not used to precisely insert the gene-scale sequences, it is promising for the same to be evaluated and exploited for large-scale sequence insertion in plants.

PE Enables Precise Sequence Insertions

Seeking to circumvent the cellular dependency on DSBs and donor DNA templates altogether, PE emerged as a revolutionary approach that “writes” new genetic information directly into the genome [

37]. Theoretically, PE allows almost all types of DNA modifications, such as base substitutions, deletions, and insertions, without a DSB [

38,

39,

139]. PE utilizes a nickase SpCas9 (nCas9) to create an R-loop at the target site and single-stranded breaks (SSBs) on the non-target strand. The SSB releases a 3′ single-stranded end that anneals to the primer binding site (PBS) of a pre-designed pegRNA, which contains the PBS and reverse transcriptase template (RTT) sequences with desired bases to be inserted into the genome [

37] (

Figure 3A). An RT enzyme fused to nCas9 adds deoxynucleotides to the 3′-OH of the nicked end, resulting in a 3′ flap that competes with the original sequence during DNA repair [

37,

140], potentially involving mismatch repair (MMR) pathways [

141]. The technique is efficient and precise in animals [

37] and plants [

38,

39], albeit different loci often bring various editing efficiencies.

PE-Based Small-Scale Sequence Insertion

The frequency of DNA insertion or protein tagging in plants using PE was found to be inversely related to the length of the DNA. Only insertions of less than 100 base pairs were efficient in animals and monocotyledon plants (

Table 1). In mammalian cells, the efficiency of PE-based sequence insertions can be improved by using a pair of pegRNAs that generate overlapping 3′ flaps, such as the TwinPE [

43] approach and its modified variants [

142,

143]. Similarly, the GRAND-PE method [

143] can achieve efficient insertion of immunogenic tags (such as 6xHis, 1xHA, or 3xFLAG tag, up to 72-bp in size) in rice, which allows for deleting genomic sequences at the insertion sites [

144,

145]. Recently, PE-mediated gene tagging has been upgraded for convenient insertion of up to 204-bp sequences [

145,

146] and has hardly reached up to 403-bp insertion using a template-jumping PE approach [

147]. In dicotyledon plants, however, protein tagging has been extremely inefficient and has not been inheritable due to low PE efficiency [

148,

149]. With the breakthrough in dicot PE [

39] and a recent upgrade of the PE system with evolved PE variants [

150] in monocots [

146,

151], we can expect more efficient small-scale sequence insertion in dicots to be reported soon.

PE-Based Large-Scale Sequence Insertion

Recently, a powerful strategy combining PE with SSRs has enabled the precise insertion of kilobase-scale DNA sequences into predefined genomic loci in both mammalian and plant cells [

41,

43,

152,

153] (

Figure 3B). In this two-step method, the PE system is first used to install specific recombination target sequences, such as loxP, lox66, or attB, into selected genomic regions. This step relies on the high precision of PE to introduce these recombination motifs without generating double-strand breaks. In the second step, exogenous donor DNAs flanked by matching recombination sites, such as lox71 or attP, are introduced into the edited cells, and site-specific recombination is catalyzed by co-delivered SSRs (e.g., Cre or phiC31 integrase), leading to precise and unidirectional integration of the donor fragment into the pre-installed recombination site [

43,

152,

153] (

Figure 3B). In plants, this concept has been significantly advanced by the development of PrimeRoot, a paired-PE-based platform that enables targeted insertion of large DNA fragments into any genomic site of interest with high precision [

41,

42] (

Figure 3B and

Table 1). PrimeRoot employs paired pegRNAs to introduce a recombination site, such as the lox66 sequence, into a genomic site of interest, thus creating a docking site for recombinase-mediated integration of a large DNA donor. A donor DNA containing a corresponding recombination motif, such as lox71, flanking the cargo DNA is then introduced, and the Cre recombinase facilitates directional recombination between the lox66 and lox71 sites. This results in a stable insertion of the donor DNA into the plant genome [

41]. PrimeRootv3 demonstrated its potential by successfully inserting a 4.9-kb gene expression cassette into a characterized genomic safe harbour site [

41]. Recently, the PrimeRoot system was upgraded with retrofitted recombination sites and artificial intelligence (AI)-based engineered recombinases that enabled precise insertion of up to 18.8 kb in the rice genome and scarless kilobase-to-megabase genome editing in plants and human cells [

44]. This cutting-edge platform provides a transformative tool for plant biotechnology by enabling the precise stacking of multiple genes or alleles at defined loci, thereby facilitating accelerated breeding of elite traits and supporting de novo domestication strategies tailored for next-generation crop improvement [

42,

44].

DNA Insertion for Plant Biology and Biotechnology

The advancement of precise DNA insertion technologies has evolved them from theoretical concepts into practical tools, enabling a wide range of applications in both fundamental plant biology and applied biotechnology. These applications include subtle modifications aimed at studying gene function, as well as the integration of entire multi-gene pathways to enhance crop improvement. In this section, we will examine three key areas where these technologies are having a transformative impact: in-locus protein tagging, cis-regulatory element engineering, and the targeted insertion of beneficial genes.

In-Locus Tagging for Gene Functioning

Precise in-locus tagging of endogenous proteins in plants has rapidly advanced, offering tools for real-time tracking, quantification, and functional analysis under native expression contexts [

155]. Tian and colleagues made a significant contribution by developing the TagBIT system, which allows for the insertion of a small HiBiT luminescent peptide tag into the coding sequences of endogenous genes in rice. This system facilitates the sensitive detection of tagged proteins through luminescence-based assays, immunoblotting, and immunoprecipitation (

Figure 4). The tagged lines were consistently passed down through generations, showcasing the system’s reliability and usefulness for quantitative proteomics in crops [

40].

PE has also emerged as a promising method for small epitope tag insertion (

Table 1). Using improved prime editor variants, researchers efficiently inserted immunogenic tags such as 6×His or HA tags precisely at the C-terminus of rice genes, enabling in-locus gene functioning in rice. This approach avoids double-stranded breaks and donor DNA templates, offering a precise and efficient strategy for seamless protein tagging in plants [

145,

146]. However, PE-based gene tagging has not been efficient with long sequences and in dicots, thereby demanding significant improvement in the systems [

148,

149].

For inserting larger tags, such as full-length fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP), CRISPR-Cas-based GT remains the primary method for enabling heritable, in-locus tagging, though its efficiency still requires improvement (

Table 1). This approach enables protein localization and dynamics to be visualized directly under endogenous regulation. While some proof-of-concept studies were limited to transient expression or used alternative luminescence reporters, the ultimate goal is to generate stably transformed plants with functional, tagged proteins, laying a foundation for advanced proteomics and cell biology in planta.

In summary, recent advancements in in-locus protein tagging and functional modification techniques for plants emphasize the expanding toolkit available for researchers. These approaches include small epitope tags, luciferase reporters, and enhancer elements, offering precise, heritable, and biologically relevant methods to study plant proteins and gene regulation directly within their natural context. As delivery and editing technologies continue to advance, in-locus tagging is set to become an essential practice in plant functional genomics, crop improvement, and synthetic biology.

Cis-Regulatory Element Insertion

The targeted insertion of cis-regulatory elements (CREs), such as enhancers and promoters, into plant genomes is emerging as a transformative strategy for fine-tuning gene expression without altering coding sequences. Unlike traditional overexpression methods, the insertion of CREs enables the endogenous regulation of gene activity, allowing for stable and contextually appropriate gene activation. This approach also differs from conventional CRISPR activation systems, which rely on transient dCas-effector proteins. A recent groundbreaking study by Yao and colleagues developed a precise strategy for inserting short transcriptional enhancers (STEs) upstream of endogenous genes in rice (

Figure 4). This approach led to a significant increase in transcriptional activity, achieving up to an 869-fold enhancement while maintaining the native gene structure. By simultaneously inserting multiple short enhancer modules, they realized strong, stable, and heritable gene activation across generations T0 to T3. This method allows for precise adjustment of gene expression strength, which is crucial for optimizing traits related to growth, metabolism, and stress responses [

156]. Shen et al. improved gene expression in rice by inserting the viral-derived translational enhancer AMVE into the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of target genes. This enhancement increased reporter activity by approximately 8.5-fold in rice protoplasts. When AMVE was inserted upstream of the

WRKY71 gene, it boosted protein levels by up to 2.8-fold without altering mRNA abundance, resulting in improved resistance to bacterial blight. Furthermore, incorporating AMVE into the

SKC1 gene enhanced salt tolerance in rice seedlings, demonstrating its potential for crop improvement [

157]. Kumar and colleagues employed the DOTI method to insert transcriptional enhancers, specifically distinct TAL effector-binding elements, into the promoter of the rice recessive

xa23 allele. These insertions allowed for pathogen-inducible expression of

xa23, resulting in heritable resistance to bacterial blight [

116]. The results show that targeted enhancer insertion can modify gene expression in response to environmental factors, providing an effective strategy for engineering disease resistance in crops.

Recently, using a CRISPR-Cas-based gene targeting method, Ke and colleagues focused on stress-responsive genes in rice that are related to drought and heat tolerance by inserting synthetic cis-regulatory elements (40-120 bp) upstream of the native promoters. The scarless insertion efficiency reached up to 10% [

158]. Functional tests demonstrated that plants with specific genetic insertions showed significantly increased expression of target genes in response to stress, resulting in improved performance under abiotic stress conditions. This research offers a promising strategy for fine-tuning the expression of endogenous genes to enhance crop resilience without the need for foreign gene introduction. Advances in gene technology build upon the groundbreaking work related to replicon-based delivery systems. For instance, the geminiviral replicon approach facilitates the precise insertion of regulatory sequences in important crop species, such as tomatoes. Cermak and his team have illustrated that replicon-enhanced homology-directed repair (HDR) can be achieved using the remarkable TALEN and CRISPR-SpCas9 technologies. They successfully inserted a CaMV 35S promoter before the

SlANT1 open reading frame (ORF), which significantly increased anthocyanin accumulation in tomato fruits [

35]. Vu and colleagues also demonstrated a similar approach using LbCas12a [

36]. These foundational platforms, initially designed for GT enhancement experiments, demonstrate that the concept can also be adapted for inserting regulatory elements into plants.

In-Locus Beneficial Gene/Allele Insertion

The insertion of genes or alleles into specific locations within the plant genome is a crucial aspect of precise plant genetic engineering. This technique enables the introduction of beneficial traits, such as pest resistance, stress tolerance, and improved nutritional content. Traditional methods primarily relied on AMT and random T-DNA integration, which often resulted in unpredictable gene expression due to position effects or gene silencing. Recent advancements using CRISPR-Cas technology have focused on achieving precise, efficient, and marker-free insertion of genes into predetermined genomic locations, thereby enhancing both predictability and safety in the genetic engineering process. Dong and colleagues made significant progress by inserting a 5.2 kb carotenoid biosynthesis cassette into a safe harbor locus in rice using the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing method [

159] (

Figure 4). The system successfully produced homozygous, marker-free rice lines with high carotenoid levels and no reduction in yield. This study demonstrated that large gene cassettes can be integrated stably and passed on to the next generations [

159].

The GT-based DNA insertion method holds promise for inserting genes and alleles; however, its low and inconsistent efficiency across various species restricts its broader use in plant breeding. This limitation has prompted the development of alternative strategies for inserting large DNA fragments. One notable example is the PrimeRoot system, which utilizes the high precision of PE to first install a recombination site at the targeted site. This initial step allows for the subsequent, efficient integration of a large donor cassette through an SSR (

Figure 3B) [

41]. Using the PrimeRoot method, Sun and colleagues successfully integrated a

PigmR gene cassette into a designated genomic safe-harbor site, with the cassette being driven by an Act1 promoter to provide resistance against rice blast disease. Importantly, the rice plants that contained this precise insertion showed improved resistance to blast disease, demonstrating a significant agronomic benefit [

41]. This research marks a significant advancement in crop genome engineering by providing a powerful alternative method for precisely stacking genes or regulatory elements to achieve desirable traits.

Overcoming the Bottlenecks to Routine Precision Insertion

Despite the impressive advancements and various applications of precise DNA insertion in plants, there are several significant challenges that hinder its routine and widespread adoption. These obstacles range from the molecular complexities involved in the editing process to the difficulties associated with plant regeneration and the overarching regulatory approval framework. Tackling these issues is the main focus of ongoing research and is crucial for unlocking the full potential of these technologies.

DNA Insertion with Scars or Scarlessness

A key factor at the molecular level is the characteristics of the final edited allele, specifically whether the insertion is seamless or leaves behind small sequence “scars.” Achieving scarless DNA insertion is the ultimate goal in precise plant genome engineering. This is particularly important for applications such as in-locus tagging, gene fusion, and partial gene replacement, where it is essential to preserve the reading frame.

Scarless editing is achievable through methods like GT, DOTI, and PE. However, each approach poses specific technical challenges: GT and DOTI require the precise selection of CRISPR-Cas cleavage sites and, in the case of DOTI, the synthesis of chemically modified long dsODNs; PE requires the design of longer and more complex RTTs and pegRNAs.

In contrast, DNA insertions accompanied by minor scars, such as small indels at the junctions, are often acceptable, particularly when full gene cassettes or regulatory elements are inserted at genomic safe harbor (GSH) sites or upstream regulatory regions. These scars may even be tolerated in in-locus tagging applications using the GRAND-PE approach, where short deletions at the insertion site do not impair gene function. Indeed, GRAND-PE often results in higher insertion efficiency and allows for longer sequence insertions compared to the scarless paired pegRNA strategy at identical loci [

143,

144,

146].

The Twin Challenges: Insertion Efficiency and Payload Size

One of the most significant technical barriers is the interconnected challenges of insertion efficiency and the size of the DNA payload that can be integrated. These two factors are often inversely correlated, representing the core limitations of current platforms.

For medium-sized insertions (up to several hundred base pairs), several competing strategies exist. The PE-based method is promising for scarless editing, but its efficiency is often dramatically reduced when the insertion length is increased (

Table 1). This is believed to stem from the increasing complexity and secondary structures (e.g., internal stem-loops) of the required RTT, which can hinder the reverse transcription process [

42]. Recent advances, such as the template-jumping PE (TJ-PE) strategy, have pushed the limit to ~400-bp in rice [

147], but this is still short of the ~800-bp achieved in human cells [

142], indicating room for improvement. Potential solutions being actively explored include engineered PE variants (e.g., PE6) that can better navigate complex RTTs [

150], AI-based engineering of PE components or small molecules, which can interfere with the MMR, such as the MLH1 binder [

160], and strategies like GRAND-PE that tolerate small junctional scars to achieve higher efficiency with longer sequences [

146,

151].

As an alternative to PE, NHEJ-based methods such as DOTI or MMEJ can also be employed. These strategies are often more efficient for generating insertions with small junctional scars but are generally inefficient for obtaining scarless products [

159]. The DOTI strategy, for example, can be enhanced by using chemically modified dsODNs (e.g., with phosphorylation and phosphorothioate linkages) to improve insertion frequency, but this approach is ultimately limited by the high cost and size constraints of synthetic donors [

113,

116,

156,

161,

162].

Integrating large DNA fragments, such as entire gene cassettes (>1 kb), remains a paramount challenge. The “gold standard” GT-based DNA insertion method allows scarless insertion up to ten kilobases, but its reliance on the low-frequency HR pathway results in low and highly variable efficiency among plant species and delivery methods (

Table 1). Newer platforms that combine with site-specific recombinases (e.g., PrimeRoot) [

41] and its upgraded version [

44] or CRISPR–transposase systems (e.g., TATSI) have successfully enabled kilobase-scale insertion [

45]. However, these may leave recombination scars and still be limited by the efficiency of the initial editing step, or leave recombination scars or rely on pre-installed docking sites, making true seamless integration difficult.

These molecular challenges are further compounded by the universal bottleneck of DNA delivery. While particle bombardment can deliver high doses of donor DNA, it is impractical for many species and can cause unwanted genomic damage. Conversely, the widely used AMT method is often limited in the dose of donor DNA it can deliver, a key bottleneck for both GT and NHEJ-mediated strategies. Several strategies can enhance AMT, such as increasing the binary vector copy number or pre-activating

Agrobacterium with acetosyringone, which is particularly relevant for large binary vectors used in GT [

163,

164]. Alternatively, the geminiviral replicon system integrated into AMT can amplify donor concentration in in planta, though it hardly delivers overly long DNA fragments due to constraints associated with the viral genome structure [

35,

36,

114,

134]. However, even with replicons, temporal coordination remains a significant hurdle; achieving the synchronized cleavages at both the genomic and donor sites required for some NHEJ-mediated strategies, or ensuring the genomic DSB coincides with the maximum local concentration of the donor template for GT, is challenging [

124].

Ultimately, to enhance insertion rates, a holistic and multi-faceted approach is essential: concurrently improving core editors, manipulating cellular DNA repair pathways, and optimizing delivery and plant regeneration systems.

Tissue Culture and Delivery Dependencies

In addition to the molecular events involved, a significant practical challenge is the reliance on tissue culture methods for transformation and regeneration. The process of inserting DNA into plants is often constrained by the dependence on these methods, which typically limit applicability to a narrow range of genotypes that are capable of forming callus and regenerating somatic shoots [

165,

166]. Protoplast-based techniques frequently face challenges such as low regeneration efficiency and poor integration rates [

167]. Furthermore, traditional methods like AMT and particle bombardment are dependent on the genotype and may result in unwanted genomic alterations, including random double-strand breaks or chromosomal rearrangements [

168,

169].

To address these challenges, several innovative delivery strategies are emerging. Nanocarriers and carbon nanotubes provide genotype-independent, non-integrative delivery systems [

170,

171]. Viral vectors, such as Potato virus X (PVX), enable transient expression and facilitate the efficient amplification of donor templates through replicons [

172]. Alternative methods like

de novo meristem induction and

in planta transformation aim to completely eliminate the need for tissue culture [

166,

173]. Moreover, methods such as pollen magnetofection and floral dip enhance the editing capabilities across various genotypes, offering new flexibility and efficiency in plant genome engineering [

173,

174,

175], albeit concerns regarding repeatability remain an issue [

176].

Regulatory Concerns

Finally, even a well-engineered plant faces the challenges posed by a complex and fragmented global regulatory landscape. The classification of genome-edited crops, which contain precisely inserted DNA sequences developed using techniques such as GT, PE, PrimeRoot, DOTI, or TATSI, primarily depends on the size, origin, and function of the inserted allele. Regulatory frameworks initially categorized these edits as either SDN-2 or SDN-3. SDN-2 refers to small, precise edits made using a homologous repair template that does not involve the integration of foreign DNA. In contrast, SDN-3 includes larger or transgenic insertions and is generally subject to regulations governing GMOs [

1,

177]. The difference between SDN-2 and SDN-3 can be ambiguous, especially for insertions that incorporate synthetic or cisgenic sequences resembling natural alleles.

Regulatory authorities adopt different approaches to assessing genetic products. Initially, the European Union (EU) classified all genetic edits that involve inserted DNA under the GMO law, regardless of their precision or the origin of the inserted sequence. However, a new category for “new genomic techniques” is currently being proposed, which could relax restrictions on modifications that involve fewer than 20 nucleotides. Notably, the EU Commission is considering the possibility of deregulating gene insertions if they originate from the gene pool of the same species (cisgenesis) and do not disrupt an endogenous gene [

178]. Countries like the United States, Japan, and China take a more nuanced approach to genetic modification. For instance, Japan allows small insertions without vector or marker sequences to bypass GMO regulations, as long as the product does not contain any transgenes. In the United States, the focus is on the risk profile of the final product rather than the specific editing method used. Similarly, China’s 2023 guidelines create a streamlined approval process for gene-edited crops that do not contain foreign DNA, although larger insertions face stricter scrutiny [

179].

The varying interpretations of regulations create uncertainty for crops that have precisely inserted alleles, even when these edits resemble natural variants or do not involve the use of transgenes. With the emergence of new tools like CRISPR-Cas-based GT, PE, PrimeRoot, and DOTI, regulators are challenged to find a balance between scientific accuracy and consistent policy. Furthermore, there is still no clear, science-based international consensus, which complicates the global adoption of edited crops in agriculture and trade.

Future Perspectives

The CRISPR-Cas systems have significantly influenced plant genome editing by allowing for precise gene knockouts and facilitating site-specific DNA insertions. However, achieving efficient and predictable insertion of long DNA sequences, particularly in elite germplasm or difficult-to-transform crops, continues to pose technical challenges. In the near future, efforts will likely concentrate on developing high-efficiency, programmable systems that enable precise integration of genes, regulatory elements, and synthetic circuits. To address the bottlenecks of efficiency and payload size, emerging platforms such as CRISPR–transposase fusions [

45], PE-based recombinase-assisted insertions [

41,

44], and novel systems, such as the programmable bridge recombination [

180], offer new possibilities for kilobase-scale, heritable DNA insertions without the need for homology arms or selection markers. Further, alternative systems of CRISPR-Cas, such as the tandem interspaced guide RNA (TIGR)-TIGR-associated (Tas) systems (TIGR-Tas) [

181] may be harnessed for precise DNA insertion in plants.

Simultaneously, improvements in PE and PE-based PrimeRoot, including engineered reverse transcriptases [

150], AI-based engineered recombinases [

44], RNA-stabilizing scaffolds [

182], accessory proteins such as RNA chaperones [

183], and novel priming strategies such as GRAND [

143] and template-jumping [

142], are expanding the potential for medium-sized insertions with greater precision. Suppressing the MMR pathway using defective plant homologs of MMR proteins [

141,

184,

185], AI-based engineered MLH1 small binder [

160], or knocking them down [

186] is also emerging as a potential strategy to enhance PE-based precise DNA insertion. To overcome the barriers to regeneration, developing tissue culture-independent delivery systems is essential. Techniques such as

in planta transformation, pollen magnetofection, and nanoparticle-based carriers are expected to help address regeneration challenges and improve access to difficult genotypes for transformation. As precise gene insertion methods evolve to support longer sequences, multiple genes, and alleles, as well as precision gene pyramiding, these advanced insertion platforms will play a crucial role in precision breeding workflows.

In parallel, regulatory frameworks are increasingly moving towards product-based assessments, especially for genetic edits that do not involve the introduction of foreign DNA. Countries like Japan, India, Kenya, and the UK have already established differentiated pathways for genome-edited crops, fostering innovation while ensuring biosafety. Future precision insertion technologies are expected to focus on cisgenic methods or new allelic variants that closely mimic naturally occurring genetic diversity, along with maintaining clear traceability and molecular characterization. These advancements will not only further scientific objectives but also help to build public trust and gain international acceptance.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, T.V.V., N.T.N, J.K., Y.W.S., W.S.C., and J.Y.K.; writing—review & editing, T.V.V. and J.Y.K.; funding acquisition, J.Y.K.; supervision, T.V.V. and J.Y.K. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (Program RS-2022-NR070609, RS-2025-02263262, RS-2021-NR060105, RS-2020-NR049590).

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those colleagues whose work could not be cited. All the figures were created with BioRender.com under a paid subscription.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

J.Y.K. is the founder and CEO of Nulla Bio Inc. The remaining authors declare that the review was written without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| 5′ UTR |

5′ untranslated region. |

| AMT |

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. |

| cNHEJ |

canonical NHEJ. |

| CRE |

cis-regulatory element. |

| CRISPR-Cas |

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR-associated protein (Cas). |

| dCas9 |

“dead” Cas9. |

| DDR |

DNA damage response. |

| DDR |

DNA damage response. |

| DETECTR |

SARS-CoV-2 DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter. |

| DOTI |

directional dsODN-based targeted insertion. |

| DSB |

double-stranded break. |

| dsODN |

dsDNA donor. |

| GMO |

genetically modified organism. |

| GOI |

gene of interest. |

| gRNA |

guide RNA. |

| GSH |

genomic safe harbor. |

| GT |

gene targeting. |

| HDR |

homology-directed repair. |

| HM |

homing nuclease. |

| HR |

homologous recombination. |

| MAR |

matrix attachment region. |

| MMEJ |

microhomology-mediated end joining. |

| MMR |

mismatch repair. |

| nCas9 |

nickase SpCas9. |

| NGT |

New Genomic Technique. |

| NHEJ |

non-homologous end joining. |

| ORF |

open reading frame. |

| PBS |

primer binding site. |

| PE |

prime editing. |

| PEG |

polyethylene glycol. |

| PVX |

potato virus X. |

| RTT |

reverse transcriptase template. |

| SDSA |

synthesis-dependent strand annealing. |

| SHERLOCK |

specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking. |

| SR |

serine recombinase. |

| SSB |

single-stranded break. |

| SSR |

Site-specific recombinase. |

| STE |

short transcriptional enhancer. |

| TagBIT |

tagging with the luminescent HiBiT peptide. |

| TALEN |

transcription activator-like effector nucleases. |

| TATSI |

Transposase-Assisted Target-Site Integration |

| T-DNA |

transfer DNA. |

| TIGR-Tas |

tandem interspaced guide RNA (TIGR)-TIGR-associated (Tas) system. |

| TJ-PE |

template-jumping PE. |

| TMV |

tobacco mosaic virus. |

| WDV |

wheat dwarf virus. |

| YR |

tyrosine recombinase. |

| ZFN |

zinc finger nuclease. |

| AI |

artificial intelligence |

References

- Vu, T.V., Das, S., Hensel, G. & Kim, J.-Y. Genome editing and beyond: what does it mean for the future of plant breeding? Planta 255, 130 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, C. et al. Cisgenesis and intragenesis: new tools for improving crops. Biol Res 46, 323-331 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Mullins, E. et al. Updated scientific opinion on plants developed through cisgenesis and intragenesis. EFSA Journal 20, e07621 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dong, O.X. & Ronald, P.C. Targeted DNA insertion in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, e2004834117 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G., Dickinson, L. & Jacob, Y. Genomic consequences associated with Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of plants. Plant J 117, 342-363 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Olhoft, P.M., Flagel, L.E. & Somers, D.A. T-DNA locus structure in a large population of soybean plants transformed using the Agrobacterium-mediated cotyledonary-node method. Plant Biotechnol J 2, 289-300 (2004).

- Schubert, D. et al. Silencing in Arabidopsis T-DNA transformants: the predominant role of a gene-specific RNA sensing mechanism versus position effects. Plant Cell 16, 2561-2572 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Daxinger, L. et al. Unexpected silencing effects from T-DNA tags in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci 13, 4-6 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. & Zhao, Y. Epigenetic Suppression of T-DNA Insertion Mutants in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 6, 539-545 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., Huang, T., Chen, L., Jiang, N. & Ren, G. T-DNA insertion in Arabidopsis caused coexisting chromosomal inversion and duplication at megabase level. Gene 923, 148577 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ruprecht, C., Carroll, A. & Persson, S. T-DNA-Induced Chromosomal Translocations in feronia and anxur2 Mutants Reveal Implications for the Mechanism of Collapsed Pollen Due to Chromosomal Rearrangements. Mol Plant 7, 1591-1594 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Nacry, P., Camilleri, C., Courtial, B., Caboche, M. & Bouchez, D. Major chromosomal rearrangements induced by T-DNA transformation in Arabidopsis. Genetics 149, 641-650 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. et al. Genome-Scale Sequence Disruption Following Biolistic Transformation in Rice and Maize. Plant Cell 31, 368-383 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M., Amundson, K., Kuppu, S., Britt, A. & Comai, L. Regeneration of Solanum tuberosum Plants from Protoplasts Induces Widespread Genome Instability. Plant Physiol 180, 78-86 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Raabe, K., Sun, L., Schindfessel, C., Honys, D. & Geelen, D. A word of caution: T-DNA-associated mutagenesis in plant reproduction research. J Exp Bot 75, 3248-3258 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kleinboelting, N. et al. The Structural Features of Thousands of T-DNA Insertion Sites Are Consistent with a Double-Strand Break Repair-Based Insertion Mechanism. Mol Plant 8, 1651-1664 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Dale, E.C. & Ow, D.W. Gene transfer with subsequent removal of the selection gene from the host genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88, 10558-10562 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.H., Hoopes, J.L. & Odell, J.T. Directed excision of a transgene from the plant genome. Mol Gen Genet 234, 49-59 (1992). [CrossRef]

- Ow, D.W. GM maize from site-specific recombination technology, what next? Curr Opin Biotechnol 18, 115-120 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Sauer, B. & Henderson, N. Targeted insertion of exogenous DNA into the eukaryotic genome by the Cre recombinase. New Biol 2, 441-449 (1990).

- Golic, K.G. & Lindquist, S. The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the Drosophila genome. Cell 59, 499-509 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Onouchi, H. et al. Operation of an efficient site-specific recombination system of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii in tobacco cells. Nucleic Acids Res 19, 6373-6378 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, P. et al. Site-specific recombination in Arabidopsis plants promoted by the Integrase protein of coliphage HK022. Plant Mol Biol 57, 435-444 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Rubtsova, M. et al. Expression of active Streptomyces phage phiC31 integrase in transgenic wheat plants. Plant Cell Rep 27, 1821-1831 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Albert, H., Dale, E.C., Lee, E. & Ow, D.W. Site-specific integration of DNA into wild-type and mutant lox sites placed in the plant genome. Plant J 7, 649-659 (1995).

- Hare, P.D. & Chua, N.-H. Excision of selectable marker genes from transgenic plants. Nat Biotechnol 20, 575-580 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Hohn, B., Levy, A.A. & Puchta, H. Elimination of selection markers from transgenic plants. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 12, 139-143 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V. et al. Challenges and perspectives in homology-directed gene targeting in monocot plants. Rice 12, 95 (2019).

- Puchta, H. & Fauser, F. Gene targeting in plants: 25 years later. Int J Dev Biol 57, 629-637 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, J., Baur, M., Bogucki, A. & Potrykus, I. Gene targeting in plants. Embo J 7, 4021-4026 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Terada, R., Urawa, H., Inagaki, Y., Tsugane, K. & Iida, S. Efficient gene targeting by homologous recombination in rice. Nat Biotechnol 20, 1030-1034 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Puchta, H., Dujon, B. & Hohn, B. Homologous recombination in plant cells is enhanced by in vivo induction of double strand breaks into DNA by a site-specific endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res 21, 5034-5040 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Puchta, H., Dujon, B. & Hohn, B. Two different but related mechanisms are used in plants for the repair of genomic double-strand breaks by homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 5055-5060 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Fauser, F. et al. In planta gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 7535-7540 (2012).

- Cermak, T., Baltes, N.J., Cegan, R., Zhang, Y. & Voytas, D.F. High-frequency, precise modification of the tomato genome. Genome Biol 16, 232 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V. et al. Highly efficient homology-directed repair using CRISPR/Cpf1-geminiviral replicon in tomato. Plant Biotechnol J 18, 2133-2143 (2020).

- Anzalone, A.V. et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149-157 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q. et al. Prime genome editing in rice and wheat. Nat Biotechnol 38, 582-585 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V. et al. Optimized dicot prime editing enables heritable desired edits in tomato and Arabidopsis. Nat Plants 10, 1502-1513 (2024).

- Tian, Y. et al. Rapid and dynamic detection of endogenous proteins through in locus tagging in rice. Plant Commun 5, 101040 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. et al. Precise integration of large DNA sequences in plant genomes using PrimeRoot editors. Nat Biotechnol 42, 316-327 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V., Nguyen, N.T., Kim, J., Hong, J.C. & Kim, J.-Y. Prime editing: Mechanism insight and recent applications in plants. Plant Biotechnol J 22, 19-36 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.V. et al. Programmable deletion, replacement, integration and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nat Biotechnol 40, 731-740 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. et al. Iterative recombinase technologies for efficient and precise genome engineering across kilobase to megabase scales. Cell 188, 4693-4710.e4615 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. et al. Transposase-assisted target-site integration for efficient plant genome engineering. Nature 631, 593-600 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Holmes-Davis, R. & Comai, L. Nuclear matrix attachment regions and plant gene expression. Trends Plant Sci 3, 91-97 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Li, S. et al. Optimization of Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation in Soybean. Front Plant Sci 8, 246 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kikkert, J.R., Vidal, J.R. & Reisch, B.I. Stable transformation of plant cells by particle bombardment/biolistics. Methods Mol Biol 286, 61-78 (2005).

- Dunny, G.M., Lee, L.N. & LeBlanc, D.J. Improved electroporation and cloning vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 57, 1194-1201 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Electroporation: theory and methods, perspectives for drug delivery, gene therapy and research. Acta Physiol Scand 177, 437-447 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Deshayes, A., Herrera-Estrella, L. & Caboche, M. Liposome-mediated transformation of tobacco mesophyll protoplasts by an Escherichia coli plasmid. Embo J 4, 2731-2737 (1985). [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.S. & Mansoor, S. Viral Vectors for Plant Genome Engineering. Front Plant Sci 8, 539 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kolesnik, V.V., Nurtdinov, R.F., Oloruntimehin, E.S., Karabelsky, A.V. & Malogolovkin, A.S. Optimization strategies and advances in the research and development of AAV-based gene therapy to deliver large transgenes. Clin Transl Med 14, e1607 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zarnitsyn, V.G. & Prausnitz, M.R. Physical parameters influencing optimization of ultrasound-mediated DNA transfection. Ultrasound Med Biol 30, 527-538 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, J.G., Copley, T.R., Hoyos-Villegas, V., Charron, J.-B. & O’Donoughue, L. A comprehensive review of in planta stable transformation strategies. Plant Methods 20, 79 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. A transgenic perspective on plant functional genomics. Transgenic Res 9, 245-260; discussion 243 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M., Kozak, M., Balola, A. & Sá-Correia, I.J.C.m.r. Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria: a feared contamination risk in water-based pharmaceutical products. 33, 10.1128/cmr. 00139-00119 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Paul, M. & Ma, J.K. Plant-made pharmaceuticals: leading products and production platforms. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 58, 58-67 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H. et al. Comparison of Plasmid Curing Efficiency across Five Lactic Acid Bacterial Species. J Microbiol Biotechnol 34, 2385-2395 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Trevors, J.T. Plasmid curing in bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 1, 149-157 (1986).

- Yan, B.W., Zhao, Y.F., Cao, W.G., Li, N. & Gou, K.M. Mechanism of random integration of foreign DNA in transgenic mice. Transgenic Res 22, 983-992 (2013). [CrossRef]

- van Kregten, M. et al. T-DNA integration in plants results from polymerase-θ-mediated DNA repair. Nat Plants 2, 16164 (2016).

- Kralemann, L.E.M. et al. Distinct mechanisms for genomic attachment of the 5′ and 3′ ends of Agrobacterium T-DNA in plants. Nat Plants 8, 526-534 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y. et al. Agrobacterium T-DNA integration into the plant genome can occur without the activity of key non-homologous end-joining proteins. Plant J 81, 934-946 (2015).

- Deng, S.K., Gibb, B., de Almeida, M.J., Greene, E.C. & Symington, L.S. RPA antagonizes microhomology-mediated repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21, 405-412 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. et al. Position effect variegation and imprinting of transgenes in lymphocytes. 36, 2320-2329 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, J.; et al. Gene expression variability between randomly and targeted transgene integration events in tobacco suspension cell lines. Plant Biotechnol Rep 14, 451-458 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Schouten, H.J., Krens, F.A. & Jacobsen, E. Cisgenic plants are similar to traditionally bred plants: international regulations for genetically modified organisms should be altered to exempt cisgenesis. EMBO reports 7, 750-753 (2006).

- Holme, I.B., Wendt, T. & Holm, P.B. Intragenesis and cisgenesis as alternatives to transgenic crop development. Plant Biotechnol J 11, 395-407 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Holme, I.; et al. A cisgenic approach for improving the bioavailability of phosphate in the barley grain. ISB News report, 8-11 (2012).

- Hobbs, S.L., Warkentin, T.D. & DeLong, C.M. Transgene copy number can be positively or negatively associated with transgene expression. Plant Mol Biol 21, 17-26 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P. & Saedler, H. Homology-dependent gene silencing in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 47, 23-48 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Schubert, D.; et al. Silencing in Arabidopsis T-DNA transformants: the predominant role of a gene-specific RNA sensing mechanism versus position effects. The Plant Cell 16, 2561-2572 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Cardi, T. Cisgenesis and genome editing: Combining concepts and efforts for a smarter use of genetic resources in crop breeding. Plant Breeding 135, 139-147 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K., Kawabayashi, T., Shikanai, T. & Hara-Nishimura, I. Decreased expression of a gene caused by a T-DNA insertion in an adjacent gene in arabidopsis. Plos one 11, e0147911 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Jo, K.R.; et al. Development of late blight resistant potatoes by cisgene stacking. BMC Biotechnol 14, 50 (2014). [CrossRef]