Introduction

In a world that is changing faster than ever, our food systems face a threat from changing climate patterns and environmental conditions. In the distant past, to meet the demands of growing populations, to enhance the crops’ nutrition, and to protect them from environmental challenges, transgenic plants emerged with the principle of transferring foreign DNA into plant cells. During those times, transgenic plants were crucial to address the agricultural needs, but they were suboptimal in terms of environmental risks, gene flow transfer into wild relatives, public perception, and approvals from regular boards. Analysing all these potential risks, a shift to non-transgenic approaches is necessary. This shift does not reject transgenic methods but aims to achieve the same goal, rather by using the plant’s own genetic makeup to increase crops’ resilience, yield, and nutritional value while handling the issues of regulatory approval and public concerns and mitigating the ecological risks.

The SmartNative Genome Editing, a non-transgenic method, can be vital in addressing agricultural sustainability and improving a plant’s capabilities through its native regulatory machinery. This strategy primarily includes two methods.

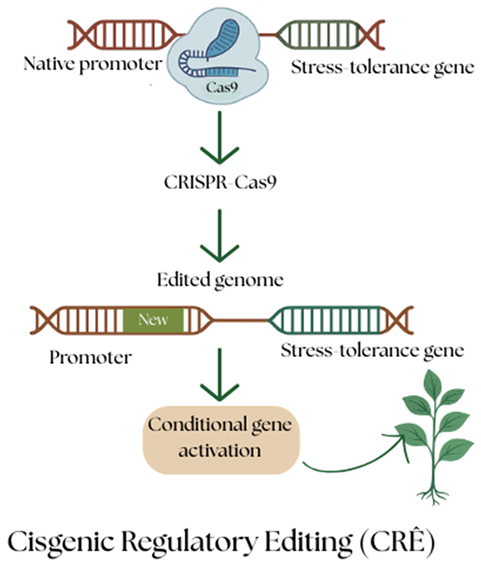

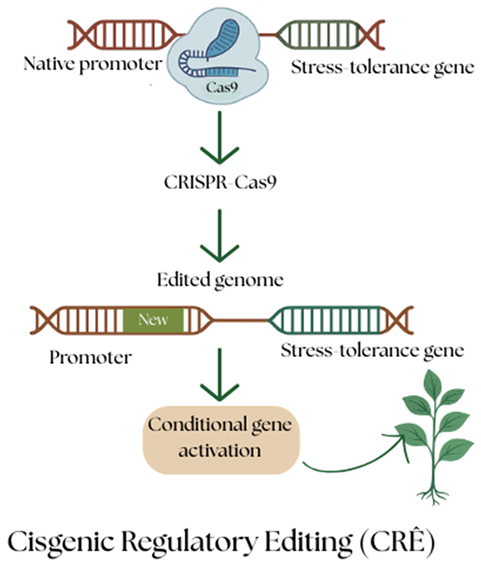

Cisgenic Regulatory Editing (CRE)

Cisgenic regulatory editing includes cis-regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, silencers, and insulators, which help to influence the gene expression level based on their binding with transcription factors. The further modifications to these sequences are done by using CRISPR-Cas9. Through this method, plants’ existing endogenous mechanisms will be further refined with the desirable traits using the same or closely related plant genome. This approach enables upregulation or conditional activation of stress-tolerance genes such as DREB, SOD, and RD29A (Lowder et al., 2015; Kasuga et al., 2004).

Case Examples

The native promoter SOD1 in rice can be replaced with light-inducible promoters such as OsRbcS or OsLEA3 from spinach to enhance the rice plants’ response towards oxidative stress, by which rice varieties can survive under high light conditions without any transgenic alterations (Kim et al., 2022).

The drought resistance gene ZmDREB2A in maize can be replaced with Rab17 from the same species to enhance early drought response while maintaining regulatory safety. (Qin et al., 2007)

Advantages

The edited gene and promoter come from the same or closely related plant species.

The gene structure is not changed, but regulating genes on and off is modified, so that it will produce the same protein.

It will not be classified as GMO and follows many countries’ rules or safety protocols, as no foreign DNA is added to the gene.

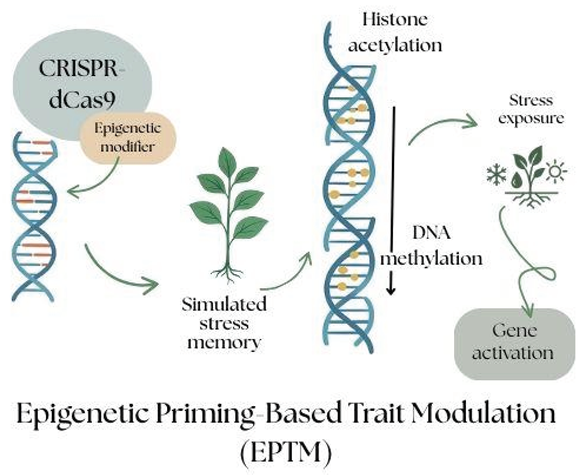

Epigenetic Priming-Based Trait Modulation (EPTM)

When a modification to sequence is done, the epigenetic priming-based trait modulation (EPTM) helps by bringing the heritable changes to gene expression without altering the original DNA sequence. These modifications are made to DNA methylation and histone proteins, which are the non-coding regions of RNA. Plants naturally exhibit responses to environmental conditions at the epigenetic level. EPTM alters the specific plant traits to enhance its response to stress.

Case Examples

Epigenetic priming at genes like DREB2A, RD29A, and LEA can induce a semi-activated chromatin state, which facilitates faster translational response upon abiotic stress exposure (Zhang et al., 2018).

Advantages

It is a reversible and non-permanent approach to deal with the stress tolerance of plants without any DNA altering (Springer & Schmitz, 2017).

It enables specific conditional gene activation to increase response against stress and activate them under certain environmental conditions.

EPTM modifies at the epigenetic level, which can be inherited by the next generations while preserving genomic integrity with no alteration to DNA sequences.

The Combined Effect of CRE and EPTM

CRE works on the hardware part of regulatory elements of DNA, i.e., to regulate the control over genes, whereas EPTM works more on the software level, i.e., on DNA and histones to regulate how genes are expressed during environmental cues. With both strategies, robust crops can be produced, where CRE provides the baseline defence and EPTM provides a smart response system against abiotic stressors.

Discussion

The powerful combination of CRE and EPTM under the method called SmartNatie Editing could provide us with a new journey to develop crops. It’s like making plants smarter using their own internal regulatory mechanisms. Instead of just adding genes from different genomes, in this method, plants’ existing DNA is used to make them more resilient and adaptable. With precision breeding and a regulatory approach, these can offer the target specificity and flexibility needed during gene modulation (Springer & Schmitz, 2017; Li et al., 2019).

However, like many new strategies, this combinational use of CRE and EPTM is not without limitations. CRE requires careful selection of promoters so that unintentional gene modifications can be mitigated, and EPTM editing revolves around epigenetic modifiers, and imprecision in them could lead to unintentional gene flow transfer to the next generations. With CRISPR-dCas9 certain modifications can be off target and cause stochastic changes, so the use of genome-wide off-target screening tools like ChIP-seq or bisulfite sequencing is important to monitor such changes.

The dynamic nature of EPTM still needed to be explored and studied: how this induced memory of stress resistance changes the plant epigenomes and effects across multiple generations. Though many target genes for EPTM are documented, their effect in combination with CRE will further need to be studied in how they can build resilience against various stresses.

By integration of transcriptomic and epigenomic data, multi-gene editing target sites can be understood, and improvement to these edits can be done and can be used to increase plants’ resilience. With future advancements, libraries of inducible promoters can be constructed and used to regulate the genes; with machine learning, the best targets for editing can be predicted, and tissue-specific chromatin editing can be identified. The complexities in these strategies’ implementation include the identification of delivery efficiency, off-target risk assessment methods, and long-term epigenetic stability.

Conclusions

SmartNative Genome Editing, a new way to improve crops, is free from transgenic constraints with precision. CRE and EPTM can act as the toolbox to upgrade the plants to face the demanding agricultural challenges by respecting the boundaries of the plants’ own genome. Through specific manipulation of cis-regulatory elements and inducing heritable epigenetic changes, robust crops can be developed without delays in regulatory approvals or harsh public perceptions. This strategy can be more sustainable when compared to its counterparts in developing abiotic stress-resilient crops that can meet the global demands and respect ecological diversity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the open-access scientific community and the innovators of CRISPR and epigenetic editing tools, which laid the foundation for the ideas and directions presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Gallego-Bartolomé, J. (2020). DNA methylation in plants: mechanisms and tools for targeted manipulation. The New phytologist, 227(1), 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, M. , Miura, S., Shinozaki, K., & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2004). A combination of the Arabidopsis DREB1A gene and stress-inducible rd29A promoter improved drought- and low-temperature stress tolerance in tobacco by gene transfer. Plant & cell physiology, 45(3), 346–350. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S. , Park, S.-I., Kim, J.-J., Shin, S.-Y., Kwak, S.-S., Lee, C.-H., Park, H.-M., Kim, Y.-H., Kim, I.-S., & Yoon, H.-S. (2022). Over-Expression of Dehydroascorbate Reductase Improves Salt Tolerance, Environmental Adaptability and Productivity in Oryza sativa. Antioxidants, 11(6), 1077. [CrossRef]

- Levi G. Lowder, Dengwei Zhang, Nicholas J. Baltes, Joseph W. Paul, Xu Tang, Xuelian Zheng, Daniel F. Voytas, Tzung-Fu Hsieh, Yong Zhang, Yiping Qi, A CRISPR/Cas9 Toolbox for Multiplexed Plant Genome Editing and Transcriptional Regulation , Plant Physiology, Volume 169, Issue 2, October 2015, Pages 971–985. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Manghwar, H., Sun, L., Wang, P., Wang, G., Sheng, H., Zhang, J., Liu, H., Qin, L., Rui, H., Li, B., Lindsey, K., Daniell, H., Jin, S. and Zhang, X. (2019), Whole genome sequencing reveals rare off-target mutations and considerable inherent genetic or/and somaclonal variations in CRISPR/Cas9-edited cotton plants. Plant Biotechnol J, 17: 858-868. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Yang, S., Zhao, M., Luo, M., Yu, C. W., Chen, C. Y., Tai, R., & Wu, K. (2014). Transcriptional repression by histone deacetylases in plants. Molecular plant, 7(5), 764–772. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, M.F. , Nasti, R.A., Vollbrecht, M. et al. Plant gene editing through de novo induction of meristems. Nat Biotechnol, 38, 84–89 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, M. and Abdulah, S.N.A. (2020), CRISPR/dCas9 platforms in plants: strategies and applications beyond genome editing. Plant Biotechnol J, 18: 32-44. [CrossRef]

- Papikian, A. , Liu, W., Gallego-Bartolomé, J. et al. Site-specific manipulation of Arabidopsis loci using CRISPR-Cas9 SunTag systems. Nat Commun, 10, 729 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Springer, N. , Schmitz, R. Exploiting induced and natural epigenetic variation for crop improvement. Nat Rev Genet, 18, 563–575 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tang, X. , Lowder, L., Zhang, T. et al. A CRISPR–Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants. Nature Plants, 3, 17018 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Qin, F. , Kakimoto, M., Sakuma, Y., Maruyama, K., Osakabe, Y., Tran, L.-S.P., Shinozaki, K. and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. (2007), Regulation and functional analysis of ZmDREB2A in response to drought and heat stresses in Zea mays L. The Plant Journal, 50: 54-69. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. , Lang, Z. & Zhu, JK. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 19, 489–506 (2018). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).