Introduction

With their high mutation rates, short generation times, large effective populations, and strong selection forces, viruses provide effective models to study evolutionary processes, especially in the genomic era [

1]. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, far surpasses every other organism in terms of the number of individual genomes studied. Over 17 million genomic sequences have been deposited in the GISAID database in 5.5 years of the pandemic [

2]. With the fitness effect of its genetic mutations intensively studied, and its interaction with the human host closely monitored, the evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2 has been unfolding before the biological community. We have observed its rapid diversification, succession of variants, selective sweeps, and “extinction” of once dominant lineages [

3]. Consequently, the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 also evolved at a pace that has not been seen in other diseases [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Interestingly, there are signs that the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 is slowing down [

8,

9]. The purpose of this paper is to review the evolutionary patterns of SARS-CoV-2 and outline the lessons that the virus has taught us about biological evolution in general.

1. Rapid Adaptive Evolution in a New Host Species

Animal viruses tend to live commensally in their natural hosts. For example, an average human being harbors 8-12 viruses in his/her body [

10]. However, they often cause diseases if spilled over to another species. Examples of commensal animal viruses that cause severe diseases in humans include the monkey B virus and the simian/human immunodeficiency virus [

11,

12]. Likewise, coronaviruses usually cause no symptoms in their reservoir species, bats, but are pathogenic in humans [

13,

14]. When a virus encounters a new host species, it must adapt to the new cellular machinery and fight the new immune systems to survive. Some viruses fail to adapt and are expelled by the new host species. Examples include avian influenza viruses, which are not transmitted between people even though humans are occasionally infected [

15]. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) can transmit between people but so far have failed to establish human reservoirs [

16]. Other zoonotic viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), have taken root and thrived in human populations.

Viruses can afford error-prone replication enzymes to explore potentially beneficial genetic changes. In the past 5.5 years, SARS-CoV-2 has undergone an amount of evolution that is comparable to that of the human species since it diverged from chimpanzees (

Table 1). Although there is evidence of fast evolution of other zoonotic viruses such as the H1N1 influenza A viruses, SARS-CoV-1, and HIV-1 after they entered mankind, we have not seen viral evolution at such a large scale or with such real time documentation [

17,

18].

2. Adaptive Radiation and Selective Sweeps

A new zoonotic virus entering humanity can be compared to a new species arriving in a previously uninhabited island. Successful adaptation often leads to rapid diversification into multiple new forms. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, diversification was not driven by selective environments of different niches but driven by an unfavorable environment of the same niche—suboptimal cellular machinery and a hostile immune system. The only advantages the virus had were airborne transmission and ambulatory hosts. Adaptive radiation manifested as rapid fixation of new mutations leading to the emergence of over a dozen dominant variants (including Alpha to Mu designated by the World Health Organization) within the first 13 months of the pandemic (from December 2019 to January 2021). Subsequently, competition for the same niche resulted in a series of selective sweeps, driving most new forms to extinction. Within half a year into the pandemic, The D614G mutant had replaced the original virus in the first selective sweep [

23]. Noticeably, all Variants of Concern (VOCs) and the early Variants of Interest (VOIs) had unique mutation spectra which derived directly from the original virus—none of them evolved from a previous VOC or VOI. By early 2022, the Omicron VOC had replaced all other variants to become the sole remaining form of SARS-CoV-2.

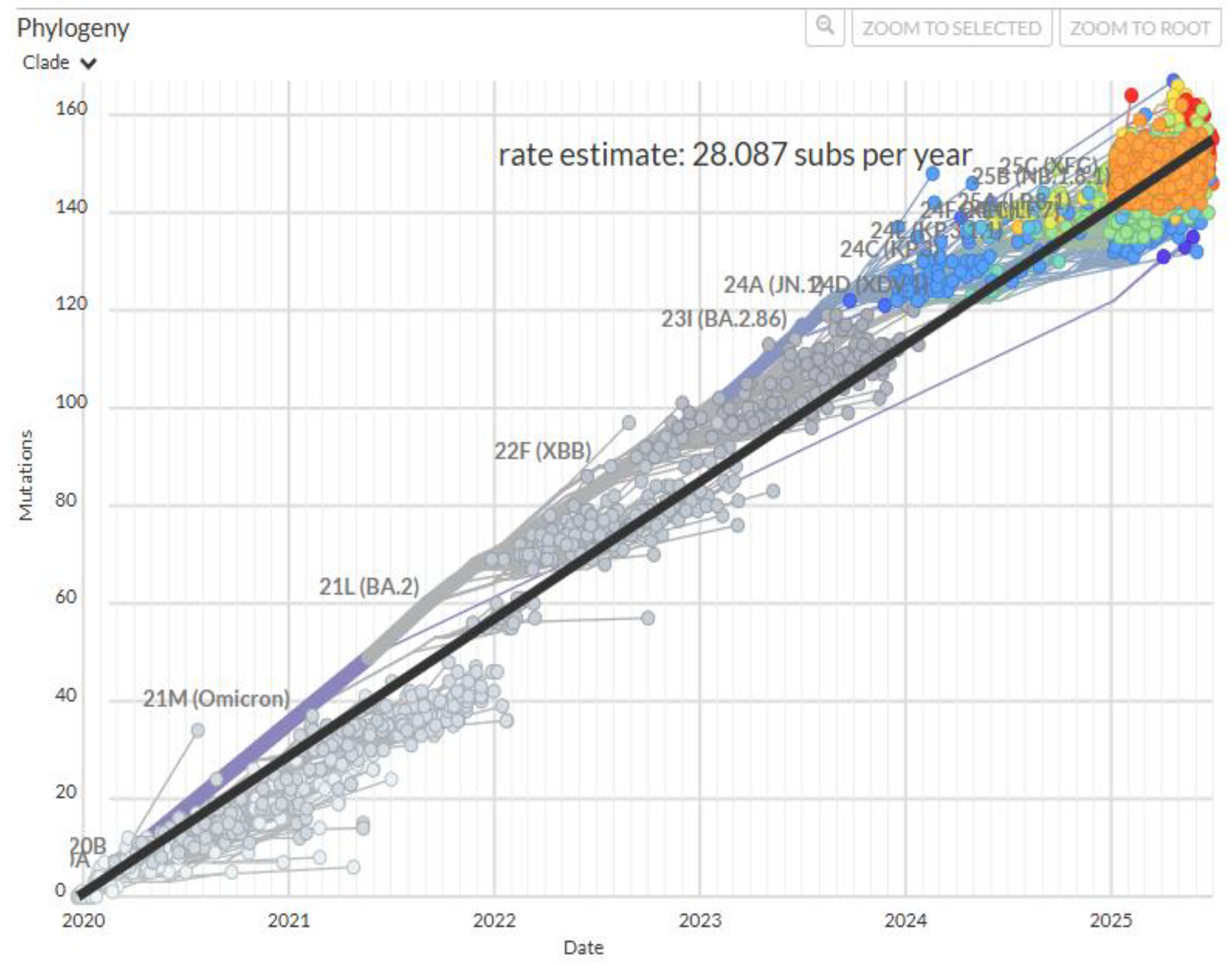

The Omicron variant continued to evolve leading to a succession of dominant subvariants. However, mutations became increasingly cyclic and repetitive [

24]. Since late 2023, evolution of SARS-CoV-2 seems to have slowed down as the accumulation of fixed mutations plateaued (

Figure 1) [

8,

9]. There has been no new VOC or VOI since the emergence of Omicron JN.1 in August of 2023.

3. The Molecular Nature of Adaptation

On the molecular level, adaptation often involves some change in the specificity of protein interactions, such as receptor-ligand binding, enzyme-substrate binding, and antibody-antigen binding. Some of the binding proteins are built with inherent genetic or epigenetic plasticity, such as the DNA recombination and somatic hypermutation mechanisms in antibody production, the population polymorphism of glutathione S-transferase (GST) enzymes, and the epigenetic induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes [

25,

26,

27]. In mutational adaptation of enzymes, a gain in binding affinity toward a new substrate is often accompanied by a loss of binding affinity toward the original substrate [

28].

The most notable aspects of adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2 are receptor binding and antibody evasion. The former involves optimization of binding between the viral spike protein and its receptor on the host cell membrane, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Early in the pandemic, it was found that SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated lower binding affinity toward bat ACE2 than the human homolog [

29]. Moreover, the virus had lost the ability to replicate in bat cells unless the cells were engineered to express human ACE2, indicating rapid adaptation soon after entering humanity, or the virus had pre-adapted in an intermediate environment [

30]. Binding affinity toward bat ACE2 further declined in the Lambda and Omicron variants as the virus evolved [

31]. Meanwhile, binding affinity toward human ACE2 increased in most VOCs. Partly because of the higher concentration of the human ACE2 in the airway epithelium than in the lungs, later variants of SARS-CoV-2 increasingly infected the upper respiratory tract (nasal epithelium) while losing replicative fitness in lung cells (via a variety of mechanisms), accounting for the decreased frequency of severe pneumonia [

32,

33,

34,

35].

Another major driving force of SARS-CoV-2 evolution, especially later in the pandemic, is evasion of neutralizing antibodies. The spike protein, especially its receptor-binding domain (RBD), is the major target of neutralizing antibodies [

36]. Unlike receptor binding where there are optimal binding modes to strive toward, immune escape mutations are not necessarily directional. A structural change is beneficial as long as it reduces binding affinity toward the dominant antibodies of the time. However, because the spike protein presents a limited number of accessible, immune-dominant epitopes, and there is a limited number of common immunoglobulin genetic segments involved in the recognition of these epitopes, immune evasion mutations of SARS-CoV-2 are restricted to a limited number of amino acid residues of the spike protein [

37,

38,

39].

Besides receptor binding and immune escape, other factors affect the replicative fitness and epidemiological fitness of SARS-CoV-2. For example, the D614G mutation resulted in an RBD that bound less tightly to ACE2 than wild type, but the mutation increased the density of intact S trimers on the viral surface by preventing premature dissociation of S1 from S2 following furin cleavage in the producing cell [

40,

41]. Preference of the nasal epithelium over the lungs made viral shedding easier, resulting in shorter incubation periods and more effective transmission [

42].

4. The Constraints of Adaptation

4.1. Deleterious Pleotropic Effects

In a 2024 review paper, Yao and colleagues reported 43 immune escape mutations in the spike protein, 14 of which simultaneously enhanced infectivity/transmissibility of the virus, while 18 facilitated immune escape at the cost of infectivity/transmissibility [

43]. Immune escape mutations that reduced infectivity/transmissibility exemplify deleterious pleotropic effects [

44,

45]. The trajectory of SARS-CoV-2 evolution seemed to oscillate between maintaining ACE2-binding and immune evasion [

46,

47].

While in vitro evolution using yeast display of RBD variant libraries yielded one best model of receptor binding (RBD-62) with a binding affinity that is 1000-fold stronger than that of wild type [

48], the highest affinity the virus ever achieved in nature was no more than 20-fold stronger than wild type [

8]. The strongest receptor-binding variant in various reports was BA.2.75, XBB.1.5, or BA.2.86 (Omicron subvariants identified between 2022 and 2023), depending on measurement methods and samples analyzed [

35,

49,

50,

51,

52]. BA.2.86 and its descendants had five of the nine affinity-enhancing mutations in RBD-62 plus V445H/R that is similar to V445K in RBD-62 (

Table 2). The other three mutations found in RBD-62 were never fixed in natural variants, suggesting that these amino acid residues must be conserved for effective viral replication or for infection of the human host.

4.2. The Order of Mutation Fixation and Diminishing Returns

When a physiological function is optimized via adaptive genetic changes, beneficial changes follow a trend of diminishing return. Experimental studies showed that the same beneficial change yielded less fitness effect when it occurred after the genetic background had been improved by other changes [

54,

55,

56]. In other words, earlier changes exert a negative epistatic effect over later changes.

The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated another trend of consecutive beneficial changes—mutations with larger fitness effects are fixed before mutations with smaller fitness effects. Because the ways to improve a function are limited, mutation fitness effect declines over time.

Table 2 shows that multiple SAR-CoV-2 variants independently converged on a mutation spectrum that was predicted by the best in vitro evolution product, IBD-62 [

48]. N501Y strongly enhanced receptor binding affinity while E484K moderately enhanced receptor-binding but strongly reduced antibody binding [

57,

58]. Both mutations were fixed independently in multiple variants early in the pandemic. Omicron initially had E484A but switched to K484 in BA.2.86 [

59]. Q498R reduced ACE2-binding affinity by itself, but significantly enhanced binding in the presence of N501Y (positive epistasis) [

60]. Combination of Q498R and N501Y appeared in multiple in vitro evolution products but fixed in nature only in Omicron after two years into the pandemic [

48]. S477N moderately stabilized the RBD-ACE2 interaction and was detected in earlier variants (e.g. Iota) but fixed in Omicron only [

48,

61]. N460K was found to enhance ACE2 binding in digital simulations but not experimentally [

62,

63,

64], and its appearance and fixation in multiple Omicron subvariants in 2022-2023 were more likely due to its immune escape effect [

64,

65]. T478K enhanced ACE2-binding modestly and facilitated immune escape [

66,

67]. It was not predicted by in vitro evolution but was fixed in the Delta and Omicron variants. Although the emergence of most of the RBD mutations were largely path-independent, the order of their fixation followed a general trend from high-impact mutations to low-impact mutations.

With diminishing fitness gain, mutation accumulation in SARS-CoV-2 slowed down as replicative fitness approached optimum. Within-clade amino acid substitution rate quickly dropped from 10-15/year to 3-9/year [

68]. The overall interclade substitution rate also showed a trend of decline, especially after the advent of JN.1 in 2023 (

Figure 1).

4.3. Path Exclusion

The Delta VOC followed a different path, which led to a “dead end”. It contained only two mutations in the RBD, L452R and T478K. The former strongly enhanced ACE2-binding and synergized with the latter [

69,

70]. It did so partly by pushing Q493 closer to the N-terminal helix of ACE2 to form hydrogen bonds with multiple ACE2 residues. This understandably constrained the mutability of Q493 [

70]. (Q493H enhanced ACE2-binding in vitro while Q493R was fixed in multiple Omicron subvariants.)

There appeared to be a mutual negative epistasis between L452R and N501Y [

60]. In the Delta background, the effect of N501Y on ACE2 binding is reduced. In the presence of N501Y (all other VOCs), L452R dampened ACE2-binding instead of enhancing it (sign epistasis).

Delta outcompeted earlier variants because of its unique mutations that enhanced receptor binding and facilitated immune escape, but when Omicron came on stage, Delta failed to adapt further and was driven to extinction, while Omicron evolved toward the optimum configuration of RBD-62. The BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants of Omicron re-acquired L452R along with compensating mutations including the R493Q reversion, but they were soon outcompeted by other Omicron subvariants (such as XBB.1.5) that did not have L452R.

In addition, L452R is mutually exclusive with F490S. The latter was predicted by in vitro evolution and fixed in the XBB subvariants [

48,

71].

4.4. “Yoyo Mutations”: Recycling the Same Tricks

L452R and Q493R represent two of the seven “yoyo mutations” of SARS-CoV-2 which appeared and disappeared multiple times on the mutant landscape [

24]. As mentioned above, L452R was anti-correlated with Q493R. The latter appeared in Omicron subvariants BA.1 and BA.2 but reversed in BA.4 and BA.5 when they re-acquired L452R. Q493R enhanced ACE2-binding in the absence of L452R, but the reversal increased receptor-binding affinity in the presence of L452R (another case of sign epistasis) [

72]. The combination of R493Q and L452R allowed BA.4 and BA.5 to gain immune escape ability without sacrificing receptor binding [

73].

Q493H was predicted by in vitro evolution, and it was partially fulfilled by Q493R since R and H are both basic. However, the mutation of Q493 into glutamic acid (E) in recent Omicron subvariants (e.g., KP.3 and LP.8) came as a surprise, not only because it was electrostatically contrary to Q493H and Q493R, but because most other mutations in the RBD resulted in basic amino acids K, R, or H. However, Q493E increased ACE2-binding affinity in the presence of L455S and F456L in KP.3 and LP.8, as it formed local salt bridges with ACE2 H34 and K31 while avoiding electrostatic repulsion from ACE2 E35. [

74,

75].

Evidently, some of the temporal “reversions” were not true reverse mutations but was due to alternations of dominant variants. For example, the Δ69-70 mutation was present in Alpha, absent in Delta, present in BA.1, and absent in BA.2, but Delta and BA.2 did not regain the two deleted amino acids. They never lost them. Most current Omicron subvariants (JN.1 descendants and a few recombinants) have Δ69-70, indicating H69V70 have probably been deleted permanently from the spike protein.

The “yoyo” mutations created moving targets allowing the virus to dodge host immunity. As the virus gained sufficient affinity toward the human ACE2, it could afford mutating antibody targets back and forth depending on the dominant antibody profile of the time. The FLip mutations (L455F+F456L) in recent Omicron subvariants apparently served the same purpose of immune evasion while preserving receptor-binding affinity [

76].

5. Punctuated “Equilibrium”

Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 was marked by three periods of saltatory changes followed by gradual accumulation of mutations. The first period was the adaptive radiation between July 2020 and January 2021 when the virus diversified rapidly, giving rise to all the VOCs and VOIs from Alpha to Mu. Although we saw no more than three fixed mutations in the RBD in each of these variants, fixed mutations throughout the spike protein and the entire genome were numerous and diverse. For example, Gamma fixed 12 mutations in the spike while Delta fixed 29 mutations throughout the genome. The second evolutionary burst was the appearance of Omicron in December 2021 with its 30+ mutations in the spike and 50+ in the entire genome. The third evolutionary burst happened in BA.2.86 which was identified in August 2023 when the total number of mutations in the spike protein jumped to 57 and the total genome mutations jumped to over 90 [

53]. The period of gradual change between the first and second bursts was 11 months, and the period between the second and third bursts was 17 months [

77]. Two years have passed since BA.2.86 and there has been no more mutational burst.

Because most of the early variants were short-lived, gradual changes were mainly observed in Omicron. The overall trend of genetic changes was sudden addition of receptor-binding mutations followed by gradual appearance of immune escape mutations. The main affinity-enhancing mutations in BA.1 were S477N, Q493R, Q498R, and N501Y. Synergism between Q498R and N501Y reconfigured the RBD-ACE2 interaction and allowed for the affinity-reducing immune escape mutations to accompany or follow the affinity-enhancing mutations [

35,

78]. BA2.86, even with its numerous affinity-enhancing mutations, did not gain dominance over the reigning XBB lineages. One more mutation, L445S, which offered immune escape at the expense of receptor-binding, turned BA.2.86 to JN.1 which quickly outcompeted all other lineages to dominate the variant landscape [

51].

Although adaptive substitution rates have slowed down in the spike protein and throughout the genome, reversions are much fewer in number, so we have not seen an equilibrium concerning genetic changes. Functionally, however, the current JN.1 sublineages have been able to fine tune the RBD-ACE2 interactions to maintain effective receptor-binding (with newer mutations such as R346T and Q493E) while constantly eluding herd immunity [

75,

79]. At this point, the evolutionary relationship between the virus and the host conforms to the Red Queen Hypothesis of relative equilibrium, setting the stage for their long-term coexistence [

80].

6. Muller’s Ratchet

Muller’s ratchet refers to the irreversible accumulation of deleterious mutations in asexual organisms as a result of genetic drift [

81]. It has been experimentally verified using RNA viruses, protozoa, and

Salmonella typhimurium through artificial bottlenecks [

82,

83]. Moreover, genetic degeneration has also been documented in the human immunodeficiency virus and the influenza virus in nature even with their large population sizes [

84,

85]. SARS-CoV-2 has presented us with an opportunity to thoroughly observe the effect of Muller’s ratchet in real time.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been repeated instances of recombination between variants [

86]. The XBB subvariants that dominated the variant landscape for over a year between 2022 and 2024 were recombinants between two BA.2 sublineages. Nevertheless, recombination is relatively rare and does not seem to affect the overall evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2.

6.1. Accumulation of Mutations in Nonstructural and Accessory Genes: Weak Selection, Drift, and Hitchhiking

Although positive selection has been the driving force for adaptive evolution of the spike protein, purifying selection has been the stronger force on nonsynonymous mutations overall, and the fitness effect of SARS-CoV-2 mutations has become more negative over time, consistent with a gradual slowdown of adaptive evolution [

8,

87]. However, purifying selection only eliminated a fraction of deleterious mutations. By February of 2022 (two years into the pandemic), ~62% of the viral genome had mutated at least once, 61.5% of which being nonsynonymous [

88]. The ratio between nonsynonymous mutations and synonymous mutation (dN/dS) are higher among the accessary genes, but are generally close to 1, indicating neutral evolution of these genes [

87,

89,

90,

91]. Nonsense mutations are almost exclusively found in accessory genes [

92].

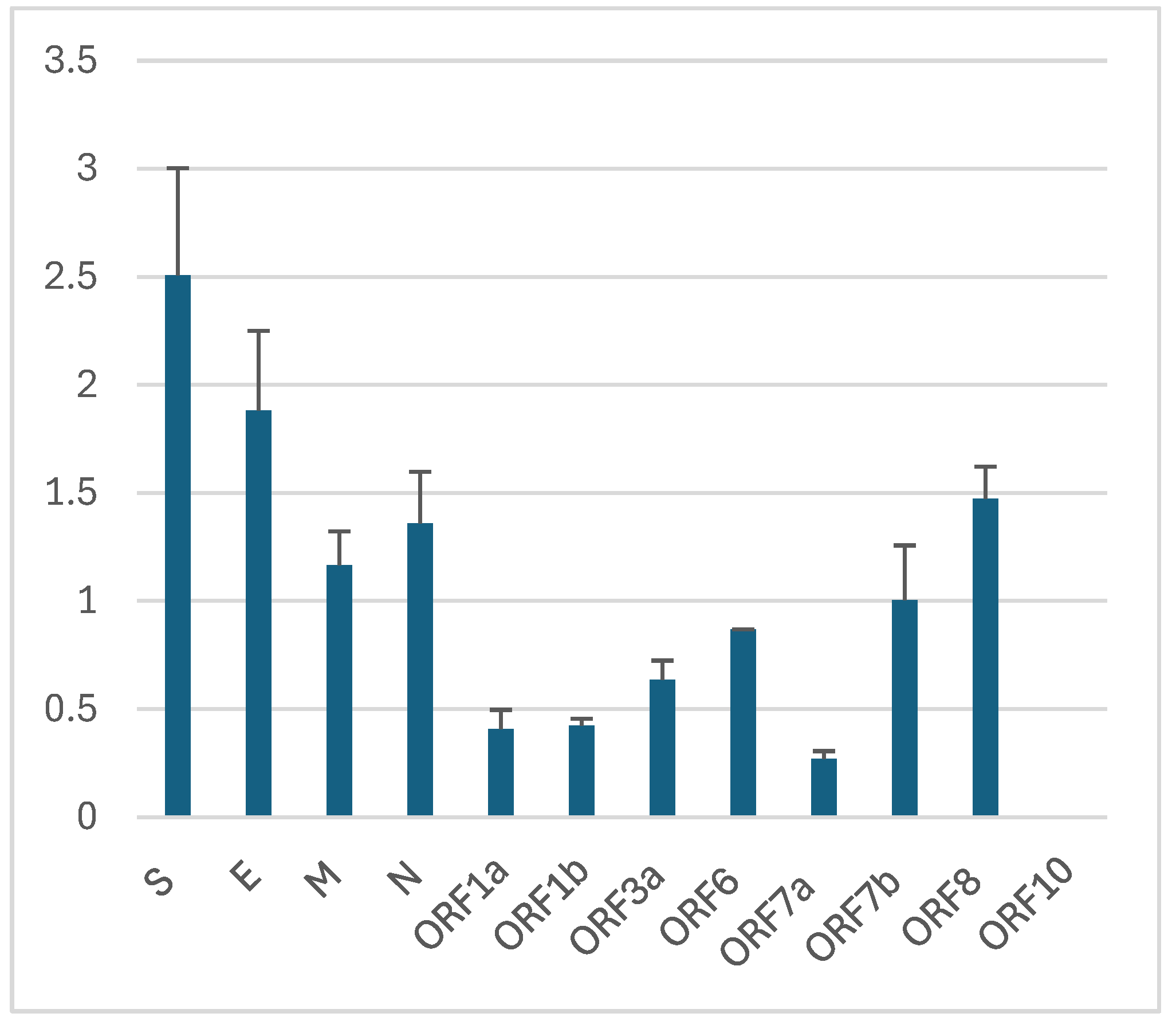

I calculated the mutation fixation rates in SARS-CoV-2 genes using the total mutation counts from two reports [

88,

92] and the number of fixed mutations found in all variants within the same period (

Table 3 and

Figure 2). The results show higher fixation rates in the structural genes (S, E, M, and N) and lower fixation rates in nonstructural genes (encoded by ORF1a and ORF1b), with accessory genes (ORF3, ORF6, ORF7-10) in between, in partial agreement with an early report [

93]. Even though the nonstructural proteins are under strong purifying selection (dN/dS ≈ 0.5) and fixed less than 0.5% of missense mutations, they still bear ~65% of the mutation load of the genome, most of which presumably being near neutral. From the strong purifying selection on the spike (S) and membrane (M) glycoproteins [

91], we can assume the high fixation rates in S and M are due to adaptative evolution. Since the envelope glycoprotein (E) and the nucleocapsid (N) are under weaker purifying selection [

91], we are less confident if the fixed mutations were due to selection or drift. However, we know that the Omicron-specific E:T9I mutation renders the virus resistant to lysosomal degradation and enhances transmission fitness, so it can be reasonably attributed to positive selection [

94].

On the other hand, mutations in ORF3a--S171L in Beta and T223I in Omicron—impede viral replication yet were fixed in the corresponding lineages, presumably due to hitchhiking or drift [

95,

96]. The D61L mutation in ORF6 is also detrimental to the virus. ORF6 antagonizes antiviral interferons by disrupting nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. D61L abolishes this function and reduces replicative fitness. Nevertheless, the mutation was fixed in BA.2, BA.4, XBB, and their descendants including the currently dominant lineages. The mutation might be responsible for the underperformance of BA.4 against BA.5 which did not have the mutation. However, the return and fixation of D61L in XBB likely hitchhiked on the epidemiological fitness of XBB over BA.5 and its sublineages, underlining the effect of linkage in the fixation of detrimental mutations.

Accessory proteins, by definition, are dispensable for viral growth in cell cultures [

97]. Moreover, their functions seem to overlap each other, so deletion or knockout of these genes have been frequent [

98]. An ORF7 deletion mutant constituted 87% of the sequences in Australia during the Delta outbreak [

99]. However, most other ORF7 deletions are random and sporadic, and have never been fixed in any lineage, attesting to the neutral nature of the mutations [

99,

100]. On the other hand, ORF8 deletions are much more common and repetitive [

101]. ORF8 of SARS-CoV-2 encodes an accessory protein to downregulate expression of the major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) molecules on infected cells for the purpose of immune evasion [

102]. Alpha, Delta, and XBB each inactivated ORF8 in unique ways, accounting to the higher number of fixed mutations in ORF8 [

91,

98,

103]. These lineages caused the most devastating waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is evidence that deletion or knockout of ORF8 is positively selected [

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104]. If so, the return of intact ORF8 in the JN.1 lineages after XBB dominance is likely a result of hitchhiking.

Weak selection, hitchhiking, and drifting all contribute to nonadaptive diversification of the nonstructural and accessory genes which eventually may lead to a reduction in fitness.

6.2. The Mistigri Hypothesis on Gene Loss

Adaptive mutations often lead to loss of genetic material which may be functional in different environments. Multiple in-frame deletions in the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein aid in immune escape with no known functional loss [

105,

106]. Deletion of NTD amino acids 25-27, 31, 69-70, 144, and 212 have been fixed in multiple lineages [

53]. Adaptation by genetic streamlining has been proposed as an explanation for the origin of some mycoplasmas,

Rickettsia, and

Chlamydia—the Ministigri hypothesis [

107]. Not only nonfunctional microbial genes are often deleted in natural and laboratory settings, but functional genes may also be lost due to genetic drift [

108]. If deletions indeed increase replicative fitness by conserving energy [

98], we can see from the repeated, yet hard-to-fix deletions of SARS-CoV-2 accessary genes that the selective force for deletion is relatively weak. Even though deletions may increase fitness in some environments, loss of genetic information decreases adaptive potential. Theoretically, the gene loss of SARS-CoV-2 may reduce its infectivity in non-human host species.

6.3. Deoptimization of Codon Usage

Based on expected frequencies of the third nucleotide in four-fold degenerate codons, the fitness effect of synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2 were calculated to be neutral and occasionally negative [

87,

109]. Comparisons between mutation counts in coding and noncoding sequences indicated purifying selection on synonymous mutations [

110]. Synonymous mutations affect codon adaptation of the virus to the host’s codon usage bias (CUB). The codon adaptation index (CAI) and the codon pair adaptation index (CPAI) reflect the match of the viral codons and the host’s CUB. When the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) spilled from chimpanzees to humanity, codon usage of the virus progressively adapted to that of the human cell during the first 15 years, followed by deoptimization due to degenerative mutations [

84]. Most large sample analyses show that codon adaptation of SARS-CoV-2, especially in the larger genes, decreased until the emergence of Omicron [

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117]. There was a sudden jump in CAI or CPAI in the Omicron variant, followed by a tendency to drop again [

110,

111,

113]. Based on the data of Padhiar and colleagues [

117],

Error! Bookmark not defined. I found a statistically significant decline in CPAI of the spike gene up till July of 2024 [

8]. Interestingly, the decline of CAI in Omicron was accompanied with a rise in dN/dS over the same time period [

111], suggesting that adaptive amino acid substitutions took priority over codon optimization. Davidson and colleagues analyzed multiple DNA and RNA viruses and found that most viral proteins show declining CUB scores over time [

112].

Decline in codon adaptation likely leads to decreased replicative fitness in the host species, but its link to pathogenicity is complicated. SARS-CoV-2 has lower CAI than SARS-Cov-1 and MERS-Cov, which have been thought to contribute to its low pathogenicity [

116], but the CAI increase in the Omicron variant was associated with attenuated virulence, presumably due to accompanying nonsynonymous mutations.

6.4. Loss of Proofreading Function

Nonstructural protein 14 (NSP14) of SARS-CoV-2 encodes an exonuclease that is responsible for the proofreading function during viral replication [

118,

119,

120]. Mutations in NSP14 were associated with an accelerated increase in mutation density throughout the viral genome [

119]. One missense mutation, NSP14:I42V, has been fixed in the Omicron variant. The mutation has been associated with decreased neuropathogenicity [

121].

7. Preservation in Immunocompromised Patients?

Simultaneous emergence of multiple advantageous missense mutations in the Omicron variant along with an increase in CAI is puzzling because pleotropic effects of mutations usually result in functional trade-offs. Even though synonymous mutations may improve codon usage without pleotropic effects [

110], they are vastly outnumbered by missense mutations which typically sacrifices CUB [

88,

91,

111,

122]. The best accepted hypothesis for the origination of Omicron is long-term evolution in a chronically infected immunocompromised host [

123]. Random decay of CUB is often caused by founder effects when the virus transmits between hosts, which is avoided in long-term Intra-host evolution. Most of the mutations in the original B.1.1.529 were not fixed [

53]. Such a large number of missense mutations on their way to fixation is not seen in other variants, indicating a unique environment of low selection pressure which is explainable with the weak antibody response in an immunocompromised host. Low immune pressure may have given the virus time to maintain its original features and even to improve codon usage at non-synonymous mutation sites. It is noteworthy that the “improvement” of codon usage in Omicron was relative to the deoptimized CUB of the Delta variant, but the CPAI of the initial Omicron virus was still comparable to that of the original virus [

8,

117]. While all other VOCs were identified within one year of the pandemic, Omicron emerged at the end of year two. Since SARS-CoV-2 infections lasting over 500 days have been reported, the origination of Omicron could have been accomplished in a single patient [

124,

125]. The situation was like the immunotolerance and immunodeficiency in HIV-infection individuals, which gave the virus 15 years of codon optimization before eventual deoptimization [

84].

A similar mechanism has been proposed for the sudden appearance of multiple missense mutations in BA.2.86, which had increased CUB scores over the original Omicron [

112,

125]. However, BA.2.86 did not alter the overall declining trend in CPAI of the spike protein [

8,

117].

Conclusions

With its short life cycle, rapid mutation, and strong selective forces, SARS-CoV-2 provided an opportunity to observe evolutionary processes that would take longer time in cellular organisms. The virus confirmed many evolutionary concepts developed over the past centuries. Rapid emergence of multiple variants demonstrated adaptive radiation followed by selective sweeps and extinction. The nature of adaptation was functional adjustment and specialization, losing fitness in bat cells to gain fitness in human cells, losing fitness in lung cells to gain fitness in nasal cells, losing replicative fitness to gain epidemiological fitness. Due to pleotropic trade-offs, natural viral evolution in the human population could not improve receptor-binding affinity to the same level as in vitro evolution with isolated molecules. As the receptor-binding affinity approached its natural limit, further mutations yielded diminishing fitness gains, demonstrating negative epistasis, with reversions exemplifying sign epistasis. While the Delta variant outcompeted earlier VOCs and VOIs, its dead-end mutations prevented it from further evolution in the presence of Omicron, which ended up being the only variant evolving toward long-term coexistence with humanity. Positive epistasis was highlighted by the synergistic RBD mutations that reconfigured the receptor-binding interface. Punctuated equilibrium was illustrated by sudden appearance of receptor-binding and immune escape mutations followed by subsequent antigenic drift. Accumulation of deleterious mutations and a trend of codon deoptimization point to Muller’s ratchet in action. Somewhat surprisingly, low selection pressures in immunocompromised patients may have provided safe havens for adaptive evolution without degradation.

While some of the history of SARS-CoV-2, such as the origin of the virus itself and of the Omicron variant, may have happened in an obscure corner of the world and remain in the dark forever, we are confident that the uneven access to virus-monitoring technology will not prevent us from witnessing the virus’ future development collectively, because, unlike HIV-1 whose subtypes established separate endemic reservoirs in different countries, the evolution of the airborne respiratory virus has been, and will likely continue to be, global in nature.

References

- Manrubia SC, Lázaro E. Viral evolution. Phys Life Rev. [CrossRef]

- Khare S, Gurry C, Freitas L, et al. GISAID’s Role in Pandemic Response. China CDC Weekly, 2021, Vol 3, Issue 49, Pages: 1049-1051, 1049. [CrossRef]

- Hodcroft, EB. CoVariants: SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and Variants of Interest. https://covariants.org/.

- Mukherjee V, Postelnicu R, Parker C, et al. COVID-19 Across Pandemic Variant Periods: The Severe Acute Respiratory Infection-Preparedness (SARI-PREP) Study. Crit Care Explor. [CrossRef]

- Endo H, Lee K, Ohnuma T, Watanabe S, Fushimi K. Temporal trends in clinical characteristics and in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19 in Japan for waves 1, 2, and 3: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy, 1393. [CrossRef]

- Flisiak R, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Dobrowolska K, et al. Change in the Clinical Picture of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 between the Early and Late Period of Dominance of the Omicron SARS-CoV-2 Variant. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, Vol 12, Page 5572, 5572. [CrossRef]

- Kojima N, Adams K, Self WH, et al. Changing Severity and Epidemiology of Adults Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States After Introduction of COVID-19 Vaccines, March 2021–August 2022. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 20 March. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Is SARS-CoV-2 facing constraints in its adaptive evolution? Biomolecules and Biomedicine, 9 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics, 4121. [CrossRef]

- Virgin HW, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Redefining Chronic Viral Infection. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Keeble, SA. B VIRUS INFECTION IN MONKEYS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri G, Paiardini M, Pandrea I, Lederman MM, Sodora DL. Understanding the benign nature of SIV infection in natural hosts. J Clin Invest, 3148. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe S, Masangkay JS, Nagata N, et al. Bat Coronaviruses and Experimental Infection of Bats, the Philippines. Emerg Infect Dis, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Hemnani M, da Silva PG, Thompson G, Poeta P, Rebelo H, Mesquita JR. Detection and Prevalence of Coronaviruses in European Bats: A Systematic Review. Ecohealth. 2024 Dec;21(2-4):125-140. [CrossRef]

- Beigel JH, de Jong D, Thi Kim Tien N, et al. Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Infection in Humans. New England Journal of Medicine, 1374. [CrossRef]

- Omrani AS, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): animal to human interaction. Pathog Glob Health. [CrossRef]

- Parrish CR, Holmes EC, Morens DM, et al. Cross-species virus transmission and the emergence of new epidemic diseases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. [CrossRef]

- Maljkovic Berry I, Athreya G, Kothari M, et al. The evolutionary rate dynamically tracks changes in HIV-1 epidemics: Application of a simple method for optimizing the evolutionary rate in phylogenetic trees with longitudinal data. Epidemics. [CrossRef]

- Amicone M, Borges V, Alves MJ, et al. Mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 and emergence of mutators during experimental evolution. Evol Med Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Sasani TA, Pedersen BS, Gao Z, et al. Large, three-generation human families reveal post-zygotic mosaicism and variability in germline mutation accumulation. Elife. [CrossRef]

- Eymieux S, Rouillé Y, Terrier O, et al. Ultrastructural modifications induced by SARS-CoV-2 in Vero cells: a kinetic analysis of viral factory formation, viral particle morphogenesis and virion release. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 3565. [CrossRef]

- Wang RJ, Al-Saffar SI, Rogers J, Hahn MW. Human generation times across the past 250,000 years. Sci Adv. [CrossRef]

- Plante JA, Liu Y, Liu J, et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature, 7852. [CrossRef]

- Focosi D, Spezia PG, Maggi F. Fixation and reversion of mutations in the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Ru H, Zhang P, Wu H. Structural gymnastics of RAG-mediated DNA cleavage in V(D)J recombination. Curr Opin Struct Biol. [CrossRef]

- Polimanti R, Carboni C, Baesso I, et al. Genetic variability of glutathione S-transferase enzymes in human populations: Functional inter-ethnic differences in detoxification systems. Gene. [CrossRef]

- Peng L, Zhong X. Epigenetic regulation of drug metabolism and transport. Acta Pharm Sin B. [CrossRef]

- Kaltenbach M, Tokuriki N. Dynamics and constraints of enzyme evolution. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Tan S, Niu S, et al. Cross-species recognition of SARS-CoV-2 to bat ACE2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Aicher SM, Streicher F, Chazal M, et al. Species-Specific Molecular Barriers to SARS-CoV-2 Replication in Bat Cells. J Virol. [CrossRef]

- Bakre A, Sweeney R, Espinoza E, Suarez DL, Kapczynski DR. The ACE2 Receptor from Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus) and Pallid Bat (Antrozous pallidus) Support Attachment and Limited Infection of SARS-CoV-2 Viruses in Cell Culture. Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Wark PAB, Pathinayake PS, Kaiko G, et al. <scp>ACE2</scp> expression is elevated in airway epithelial cells from older and male healthy individuals but reduced in asthma. Respirology. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Lu L, Peng Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant shows less efficient replication and fusion activity when compared with Delta variant in TMPRSS2-expressed cells. Emerg Microbes Infect. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai Y, Okada S, Ozeki T, Yoshikawa R, Kinoshita T, Yasuda J. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants progressively adapt to human cells with altered host cell entry. mSphere. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhao X, Shi J, et al. Lineage-specific pathogenicity, immune evasion, and virological features of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86/JN.1 and EG.5.1/HK.3. Nature Communications. [CrossRef]

- Yuan M, Liu H, Wu NC, Wilson IA. Recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain by neutralizing antibodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. [CrossRef]

- Chen EC, Gilchuk P, Zost SJ, et al. Convergent antibody responses to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in convalescent and vaccinated individuals. Cell Rep, 1096. [CrossRef]

- Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Addetia A, et al. Prospective mapping of viral mutations that escape antibodies used to treat COVID-19. Science (1979), 6531. [CrossRef]

- Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Crawford KHD, et al. Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell Host Microbe. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Jackson CB, Mou H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat Commun. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Cai Y, Xiao T, et al. Structural impact on SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by D614G substitution. Science (1979), 6541. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Wu Y, Kummer AG, et al. Assessing changes in incubation period, serial interval, and generation time of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. [CrossRef]

- Yao Z, Zhang L, Duan Y, Tang X, Lu J. Molecular insights into the adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Journal of Infection, 1061. [CrossRef]

- McGuigan K, Collet JM, Allen SL, Chenoweth SF, Blows MW. Pleiotropic Mutations Are Subject to Strong Stabilizing Selection. Genetics, 1051. [CrossRef]

- Otto, SP. Two steps forward, one step back: The pleiotropic effects of favoured alleles. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li W, Xu Z, Niu T, et al. Key mechanistic features of the trade-off between antibody escape and host cell binding in the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant spike proteins. EMBO J, 1484. [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani N, Alshahrani M, Gupta G, Verkhivker G. AlphaFold2 Modeling and Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Conformational Ensembles for the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Omicron JN.1, KP.2 and KP.3 Variants: Mutational Profiling of Binding Energetics Reveals Epistatic Drivers of the ACE2 Affinity and Escape Hotspots of Antibody Resistance. Viruses, 1458. [CrossRef]

- Zahradník J, Marciano S, Shemesh M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant prediction and antiviral drug design are enabled by RBD in vitro evolution. Nat Microbiol, 1188. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Wei P, Kappler JW, Marrack P, Zhang G. SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern and Variants of Interest Receptor Binding Domain Mutations and Virus Infectivity. Front Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Guo H, Wang A, et al. Structural basis for the evolution and antibody evasion of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 and JN.1 subvariants. Nature Communications. [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Yu Y, Xu Y, et al. Fast evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 to JN.1 under heavy immune pressure. Lancet Infect Dis. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Sugano A, Murakami J, Kataguchi H, et al. In silico binding affinity of the spike protein with ACE2 and the relative evolutionary distance of S gene may be potential factors rapidly obtained for the initial risk of SARS-CoV-2. Microb Risk Anal, 1002. [CrossRef]

- Gangavarapu K, Latif AA, Mullen JL, et al. Outbreak.info genomic reports: scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nat Methods. [CrossRef]

- Chou HH, Chiu HC, Delaney NF, Segrè D, Marx CJ. Diminishing Returns Epistasis Among Beneficial Mutations Decelerates Adaptation. Science (1979), 6034. [CrossRef]

- Khan AI, Dinh DM, Schneider D, Lenski RE, Cooper TF. Negative Epistasis Between Beneficial Mutations in an Evolving Bacterial Population. Science (1979), 6034. [CrossRef]

- Weinreich DM, Delaney NF, DePristo MA, Hartl DL. Darwinian Evolution Can Follow Only Very Few Mutational Paths to Fitter Proteins. Science (1979), 5770. [CrossRef]

- Jangra S, Ye C, Rathnasinghe R, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike E484K mutation reduces antibody neutralisation. Lancet Microbe. [CrossRef]

- Barton MI, Macgowan S, Kutuzov M, Dushek O, Barton GJ, Anton Van Der Merwe P. Effects of common mutations in the sars-cov-2 spike rbd and its ligand the human ace2 receptor on binding affinity and kinetics. Elife. [CrossRef]

- Kamble P, Daulatabad V, Singhal A, et al. JN.1 variant in enduring COVID-19 pandemic: is it a variety of interest (VoI) or variety of concern (VoC)? Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Hannon WW, et al. Shifting mutational constraints in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain during viral evolution. Science (1979), 6604. [CrossRef]

- Annavajhala MK, Mohri H, Wang P, et al. Emergence and expansion of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.526 after identification in New York. Nature, 7878. [CrossRef]

- Qu P, Evans JP, Zheng YM, et al. Evasion of neutralizing antibody responses by the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.75 variant. Cell Host Microbe, 1518. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HL, Nguyen TQ, Li MS. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants Do Not Differ Much in Binding Affinity to Human ACE2: A Molecular Dynamics Study. J Phys Chem B, 3340. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Song W, Wang L, et al. Characterization of the enhanced infectivity and antibody evasion of Omicron BA.2.75. Cell Host Microbe, 1527. [CrossRef]

- Huo J, Dijokaite-Guraliuc A, Liu C, et al. A delicate balance between antibody evasion and ACE2 affinity for Omicron BA.2.75. Cell Rep, 1119. [CrossRef]

- Mannar D, Saville JW, Zhu X, et al. Structural analysis of receptor binding domain mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern that modulate ACE2 and antibody binding. Cell Rep, 1101. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Liu C, Zhang C, et al. Structural basis for SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant recognition of ACE2 receptor and broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nat Commun. [CrossRef]

- Neher, RA. Contributions of adaptation and purifying selection to SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Virus Evol. [CrossRef]

- Tchesnokova V, Kulasekara H, Larson L, et al. Acquisition of the L452R Mutation in the ACE2-Binding Interface of Spike Protein Triggers Recent Massive Expansion of SARS-CoV-2 Variants. J Clin Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Chan KC, Song Y, Xu Z, Shang C, Zhou R. SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant: Interplay between Individual Mutations and Their Allosteric Synergy. Biomolecules, 1742. [CrossRef]

- Innocenti G, Obara M, Costa B, et al. Real-time identification of epistatic interactions in SARS-CoV-2 from large genome collections. Genome Biol. [CrossRef]

- Philip AM, Ahmed WS, Biswas KH. Reversal of the unique Q493R mutation increases the affinity of Omicron S1-RBD for ACE2. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 1966. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Guo Y, Iketani S, et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature, 7923. [CrossRef]

- Taylor AL, Starr TN. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.86 and epistatic emergence of the KP.3 variant. Virus Evol. [CrossRef]

- Feng L, Sun Z, Zhang Y, et al. Structural and molecular basis of the epistasis effect in enhanced affinity between SARS-CoV-2 KP.3 and ACE2. Cell Discov. [CrossRef]

- Jian F, Feng L, Yang S, et al. Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 XBB lineages on receptor-binding domain 455–456 synergistically enhances antibody evasion and ACE2 binding. PLoS Pathog, 1011. [CrossRef]

- Hulo C, De Castro E, Masson P, et al. ViralZone: a knowledge resource to understand virus diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. [CrossRef]

- Dejnirattisai W, Huo J, Zhou D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Mellis IA, Ho J, et al. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations confer growth advantages to select JN.1 sublineages. Emerg Microbes Infect. Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Duarte CM, Ketcheson DI, Eguíluz VM, et al. Rapid evolution of SARS-CoV-2 challenges human defenses. Sci Rep, 6457. [CrossRef]

- Muller, HJ. The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutation Research - Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. [CrossRef]

- Chao, L. Fitness of RNA virus decreased by Muller’s ratchet. Nature, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson DI, Hughes D. Muller’s ratchet decreases fitness of a DNA-based microbe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. [CrossRef]

- Pandit A, Sinha S. Differential Trends in the Codon Usage Patterns in HIV-1 Genes. PLoS One, 2888. [CrossRef]

- Carter RW, Sanford JC. A new look at an old virus: patterns of mutation accumulation in the human H1N1 influenza virus since 1918. Theor Biol Med Model. [CrossRef]

- Chernyaeva EN, Ayginin AA, Kosenkov A V., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Recombination and Coinfection Events Identified in Clinical Samples in Russia. Viruses, 1660. [CrossRef]

- Bloom JD, Neher RA. Fitness effects of mutations to SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Virus Evol. [CrossRef]

- Lippi G, Henry BM. The landscape of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) genomic mutations. J Lab Precis Med. [CrossRef]

- McGrath ME, Xue Y, Dillen C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant spike and accessory gene mutations alter pathogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Gupta D, Bhatnagar S. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genome evolutionary patterns. Microbiol Spectr. [CrossRef]

- Yi K, Kim SY, Bleazard T, Kim T, Youk J, Ju YS. Mutational spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 during the global pandemic. Exp Mol Med, 1229. [CrossRef]

- Colson P, Chaudet H, Delerce J, et al. Role of SARS-CoV-2 mutations in the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Infection, 1061. [CrossRef]

- Omotoso OE, Babalola AD, Matareek A. Mutational hotspots and conserved domains of SARS-CoV-2 genome in African population. Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. [CrossRef]

- Klute S, Nchioua R, Cordsmeier A, et al. Mutation T9I in Envelope confers autophagy resistance to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. iScience, 1129. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Qu Y, Wang X, et al. Genetic variety of ORF3a shapes SARS-CoV-2 fitness through modulation of lipid droplet. J Med Virol. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann S, Radochonski L, Ye C, Martinez-Sobrido L, Chen J. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a drives dynamic dense body formation for optimal viral infectivity. Nat Commun, 4393. [CrossRef]

- López-Ayllón BD, de Lucas-Rius A, Mendoza-García L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins involvement in inflammatory and profibrotic processes through IL11 signaling. Front Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Focosi D, Spezia PG, Maggi F. Subsequent Waves of Convergent Evolution in SARS-CoV-2 Genes and Proteins. Vaccines (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Foster CSP, Bull RA, Tedla N, et al. Persistence of a Frameshifting Deletion in SARS-CoV-2 ORF7a for the Duration of a Major Outbreak. Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Panzera Y, Calleros L, Goñi N, et al. Consecutive deletions in a unique Uruguayan SARS-CoV-2 lineage evidence the genetic variability potential of accessory genes. PLoS One, 0263. [CrossRef]

- Lam JY, Kok KH. The Recurring Loss of ORF8 Secretion in Dominant SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Int J Mol Sci, 5778. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y, et al. The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-Ι. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Arduini A, Laprise F, Liang C. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8: A Rapidly Evolving Immune and Viral Modulator in COVID-19. Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Wagner C, Kistler KE, Perchetti GA, et al. Positive selection underlies repeated knockout of ORF8 in SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Nature Communications. [CrossRef]

- Colson P, Delerce J, Fantini J, Pontarotti P, La Scola B, Raoult D. The return of the “Mistigri” (virus adaptative gain by gene loss) through the SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.5 chimera that predominated in 2023. J Med Virol. [CrossRef]

- Rayati Damavandi A, Dowran R, Al Sharif S, Kashanchi F, Jafari R. Molecular variants of SARS-CoV-2: antigenic properties and current vaccine efficacy. Med Microbiol Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Moran, NA. Microbial Minimalism. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Meyer H, Sutter G, Mayr A. Mapping of deletions in the genome of the highly attenuated vaccinia virus MVA and their influence on virulence. Journal of General Virology, 1031. [CrossRef]

- Haddox HK, Angehrn G, Sesta L, et al. The mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 is highly variable between sites and is influenced by sequence context, genomic region, and RNA structure. Nucleic Acids Res. [CrossRef]

- Bai H, Ata G, Sun Q, Rahman SU, Tao S. Natural selection pressure exerted on “Silent” mutations during the evolution of SARS-CoV-2: Evidence from codon usage and RNA structure. Virus Res. [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli SE, Padhiar NH, Meyer D, et al. Analysis of 3.5 million SARS-CoV-2 sequences reveals unique mutational trends with consistent nucleotide and codon frequencies. Virol J. [CrossRef]

- Davidson A, Parr M, Totzeck F, et al. Over time analysis of the codon usage of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2034. [CrossRef]

- Mogro EG, Bottero D, Lozano MJ. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 synonymous codon usage evolution throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Virology. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Shan K jia, Zan F, Tang X, Qian Z, Lu J. Optimization and Deoptimization of Codons in SARS-CoV-2 and Related Implications for Vaccine Development. Advanced Science. [CrossRef]

- Posani E, Dilucca M, Forcelloni S, Pavlopoulou A, Georgakilas AG, Giansanti A. Temporal evolution and adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 codon usage. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark. [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Guo Y, Li N, Feng Y, Xiao L. Codon usage analysis of zoonotic coronaviruses reveals lower adaptation to humans by SARS-CoV-2. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. [CrossRef]

- Padhiar NH, Ghazanchyan T, Fumagalli SE, et al. SARS-CoV-2 CoCoPUTs: analyzing GISAID and NCBI data to obtain codon statistics, mutations, and free energy over a multiyear period. Virus Evol. [CrossRef]

- Takada K, Ueda MT, Shichinohe S, et al. Genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 can be accelerated by mutations in the nsp14 gene. iScience, 1062. [CrossRef]

- Eskier D, Suner A, Oktay Y, Karakülah G. Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 nsp14 exhibit strong association with increased genome-wide mutation load. PeerJ, 1018. [CrossRef]

- Hassan SS, Bhattacharya T, Nawn D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 governs mutational instability and assists in making new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Comput Biol Med, 1078. [CrossRef]

- Sangare K, Liu S, Selvaraj P, Stauft CB, Starost MF, Wang TT. Combined mutations in nonstructural protein 14, envelope, and membrane proteins mitigate the neuropathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 in K18-hACE2 mice. mSphere. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed JQ, Maulud SQ, Al-Qadi R, et al. Sequencing and mutations analysis of the first recorded SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant during the fourth wave of pandemic in Iraq. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1026. [CrossRef]

- Markov P, V. , Ghafari M, Beer M, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. Nature Research. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Zhao H, Espín E, Tebbutt SJ. Association of SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence with long COVID. Lancet Respir Med. [CrossRef]

- Machkovech HM, Hahn AM, Garonzik Wang J, et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection: significance and implications. Lancet Infect Dis. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).