1. Introduction

Phytophthora nicotianae is a soil-borne bi-flagellated oomycete, responsible for significant losses on a number of economically important species including fruit, oilseed, vegetables, and ornamental plants [

1,

2]. In tobacco,

P. nicotianae can infect all parts of the plant at any growth stage, causing severe damage under both greenhouse and field conditions [

3]. The infection typically begins in the roots, which become water-soaked and rapidly turn necrotic. As the disease progresses, leaves develop large circular lesions or turn brown to black. Because one of the most characteristic symptoms is blackening of the stalk base or shank, the disease is called black shank in tobacco [

4].

Based on the ability to infect various cultivars carrying different resistance genes

, four physiological races (0-3) of

P. nicotianaea were reported [

5]. In tobacco resistance breeding programs, two commonly mentioned resistant germplasms, Florida 301 and Beinhart 1000 (BH), have played important roles in the development of black shank-resistant cultivars [

6,

7,

8]. However, both germplasms exhibit limitations in terms of resistance durability and breeding efficiency. In addition to these sources, single dominant resistance (

R) genes,

Php and

Phl, have been successfully introgressed into cultivated tobacco through distant hybridization [

4]. While these genes confer immunity to race 0 of

P. nicotianaea, they are ineffective against other physiological races [

9,

10,

11]. Similarly, another

R gene,

NpPP2-B10, has been shown to provide resistance that is also race-specific [

12].

As

R gene-mediated resistance relies on the recognition of specific pathogen effectors and the activation of downstream defense responses, which are often race-specific and prone to being overcome by rapidly evolving pathogens, an alternative strategy involves loss-of-function mutations in susceptibility (

S) genes. All plant genes that facilitate infection can be considered as

S genes [

13] and disrupting these genes may interfere with the compatibility between the host and the pathogens, which can provide broad-spectrum and potentially more durable disease resistance [

14,

15,

16,

17]. One typical

S gene is

MLO (Mildew Locus O), which has been used in a wide range of plant crops such as apples, barley, cucumbers, grapevines, melons, peas, tomatoes, and wheat [

18]. Other

S genes, like

StDND1 and

StDMR6 in potato, showed enhanced late blight resistance upon gene knockdown [

19]. Although disruption of

S genes seems a faster and simpler way to achieve broad-spectrum and durable disease resistance, pleiotropic effects caused by their inactivation need to be evaluated and prevented [

20].

Arabidopsis

DMR6, a member of the 2-oxoglutarate Fe (II) dependent oxygenases (2OG oxygenases) superfamily, has been identified as an

S gene as the over-expression of

AtDMR6 increases disease susceptibility. The study also shows that this loss-of-function mutants of

dmr6 exhibit enhanced resistance to multiple pathogens, but slightly affects plant development, which is associated with increased levels of salicylic acid (SA) content [

21]. Subsequent research disclosed that

AtDMR6 encodes a salicylic acid 5-hydroxylase that hydroxylates SA, further establishing a mechanistic link between

dmr6-mediated resistance and SA accumulation [

22]. Comparable to Arabidopsis, knocking-out the homologs of

DMR6 in potato and tomato resulted in enhanced disease resistance, without any negative pleiotropic or growth retardation effect [

16,

18]. These findings indicate that

DMR6 represents a promising target for the genetic engineering of broad-spectrum and durable disease resistance in different crop species.

In this study, we identified two DMR6 orthologs in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S, and generated targeted mutants using CRISPR/Cas9 to assess their breeding potential and investigate their downstream regulatory networks. Loss of either gene conferred enhanced resistance, and RT-qPCR analyses revealed that genes associated with mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, energy metabolism, peroxidase activity, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were significantly affected. These results suggest that NtDMR6s modulate host immunity through multiple pathways, thereby broadening our understanding of S gene functions and underscoring the regulatory role of DMR6 in plant–pathogen interactions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Wild type tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Honghuadajinyuan, HD) was provided by the Tobacco Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Accession number 00000540). For greenhouse cultivation, tobacco seedlings of the NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S mutants and the wild type HD were transplanted into plastic pots filled with potting soil two weeks after sowing. Plants were grown in a controlled growth chamber under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod at 25 °C. After an additional two weeks of growth, plants were used for subsequent pathogen inoculation experiments. For field trials, sixteen-week-old seedlings were transplanted into plots at the Jimo Experimental Station, Tobacco Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (35.4°N, 119.3°E, 15 m altitude). The field layout included 10 m row lengths, with a row spacing of 1.2 m and a plant spacing of 0.5 m.

2.2. Construction of Phylogenetic Tree

Protein sequences containing the 2-oxoglutarate Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase domain (Pfam accession: PF03171) were retrieved from InterPro [

23]. Candidate 2OG oxygenase proteins in the

Nicotiana tabacum ZY300 reference genome (NCBI: PRJNA940510) [

24] were subsequently identified using HMMER 3.0 [

25] and further validated via the NCBI Batch CD-Search tool. Functionally characterized 2OG oxygenase protein sequences in

Arabidopsis thaliana were obtained from TAIR (

https://www.arabidopsis.org/). Homologous sequences of DMR6 in

Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) and

Solanum tuberosum (potato) were retrieved from NCBI. The phylogenetic trees (

Figure 1;

Figure 2a) were constructed using MEGA 7.0 with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method and then displayed with the online iTOL tool (

https://itol.embl.de/).

2.3. Promoter Analysis

The 2-kb promoter regions upstream of

NtDMR6T and

NtDMR6S were retrieved from the

Nicotiana tabacum ZY300 reference genome (NCBI: PRJNA940510) [

24]. PlantCARE (

http://bioin- formatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was used to analyze

cis-acting elements within these promoter sequences [

26].

2.4. Construction of the CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmids and Mutant Construction

Codon optimized hSpCas9 was linked to the maize ubiquitin promoter (UBI) in an intermediate plasmid, and then this expression cassette was inserted into binary pCAMBIA1300 (Cambia, Australia) which contains the HPT (hygromycin B phosphotransferase) gene. The originally existing BsaI site in the pCAMBIA1300 backbone was removed using a point mutation kit (Transgen, China). A fragment comprised of a OsU6 promoter, a negative selection marker gene ccdB flanked by two BsaI sites and a sgRNA derived from pX260 was inserted into this vector using the In-fusion cloning kit (Takara, Japan) to produce the CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector pBGK032. E. coli strain DB3.1 was used for maintaining this binary vector.

The 23-bp targeting sequences (

Table S1) were selected within the target genes and their targeting specificity was confirmed using a Blast search against the tobacco genome (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The designed targeting sequences were synthesized and annealed to form the oligo adaptors. Vector pBGK032 was digested by

BsaI and purified using DNA purification kit (Tiangen, China). A ligation reaction (10 µL) containing 10 ng of the digested pBGK032 vector and 0.05 mM oligo adaptor was carried out and directly transformed to

E. coli competent cells to produce CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids.

The constructed CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids were introduced into

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. Tobacco transformation was performed following the protocol described by Sparkes et al. [

27], using HD as the recipient genotype. Genomic DNA was extracted from the regenerated transformants, and the regions flanking the target sites were amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs (

Table S1). The resulting PCR products were sequenced to confirm genome editing events.

2.5. Pathogen Inoculation and Resistance Evaluation

Phytophthora nicotianae (race 0), originally isolated from infected tobacco stems in Jimo, Qingdao, Shandong Province in 2011, was cultured on oatmeal medium for 14 days. To induce zoospore release, 15 mL of 0.1% KNO

3 solution was added to each plate, followed by chilling at 4 °C for 20 min and incubation at 25 °C for 25 min. The resulting zoospore suspension was collected and adjusted to 1 × 10

5 cfu·mL

−1. One-month-old tobacco seedlings were immersed in the zoospore suspension in the dark at 25 °C for 3 h, then transferred to new Petri dishes containing 10 mL of sterile water to immerse the roots. Two layers of filter paper were placed over the roots to maintain a good moisture content. Plants were grown at 25 °C under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod. Disease severity was scored on a 0-9 scale, and the disease index was calculated using a standard formula. Meanwhile, root samples were independently collected at 0 h, 12h, 24h, 48 h, 72h post-inoculation, and these samples were subsequently stored at –80 °C. The experiment was independently repeated three times with consistent results.

2.6. cDNA Synthesis and RT-qPCR

Total RNA (1 µg) was reverse-transcribed using the HiScript III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Vazyme, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa, Japan) on a LightCycler 96 system (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) in 20-µL reactions. The composition of each PCR reaction was as follows: 10 μL master mix, 7 μL ddH2O, 1 μL cDNA, and 1 μL of both forward and reverse primers (5 μM). The RT-qPCR assay was performed three times with the following conditions: 95 °C for 30 s initially, then 40 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 15 s. Relative expression levels were computed via the 2

-ΔΔCt method.

NtActin (

NtZY23T00337.1) was used as an internal reference for normalization. Each assay included three biological replicates. Primer sequences are listed in

Table S1.

2.7. Measurement of Tobacco Agronomic Traits

To determine the effects of NtDMR6 impairment on plant growth in the greenhouse, the plant height (calculated as the height of the stem from the soil surface to stem apex) of 15 plants of each mutant (DC6198L, DC6527L, DC6229L) and 15 wild type (HD) plants were measured using a tape measure. To assess the effects of NtDMR6 impairment on plant growth under field conditions, four agronomic traits—plant height, leaf number, leaf length, and leaf width—were measured at maturity, approximately sixteen weeks after sowing.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, USA) was used to perform Student’s

t-test (

Table S2) and to generate histograms and other relevant graphical representations. A

P-value less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

2.9. Gene Accession Numbers

NtDMR6T (NtZY04T01846.1), NtDMR6S (NtZY06T02310.1), AtDMR6 (AT5G24530), AtDLO (AT4G10490, AT4G10500), AtFLS1 (AT5G08640), AtFLS3 (AT5G63590), AtANS (AT4G22880), AtF3H (AT3G51240), WRKY6 (NtZY03T00604.1), WRKY46 (NtZY21T01503.1), PR1 (NtZY07T00599.1), NPR1 (NtZY10T03125.1), RRS1 (NtZY21T01803.1), PSAF (NtZY03T03735.1), PNSL4 (NtZY11T01075.1), ARFA (NtZY13T01719.1), TCP4 (NtZY02T01123.1), MKK4 (NtZY22T03510.1), MPK3 (NtZY17T00471.1), MPK7 (NtZY17T03798.1), PCK1 (NtZY12T02043.1), PDHC (NtZY23T00063.1), PER1 (NtZY24T00949.1), PER2 (NtZY05T00437.1), CAMT3 (NtZY17T01647.1), CAS1 (NtZY01T02870.1).

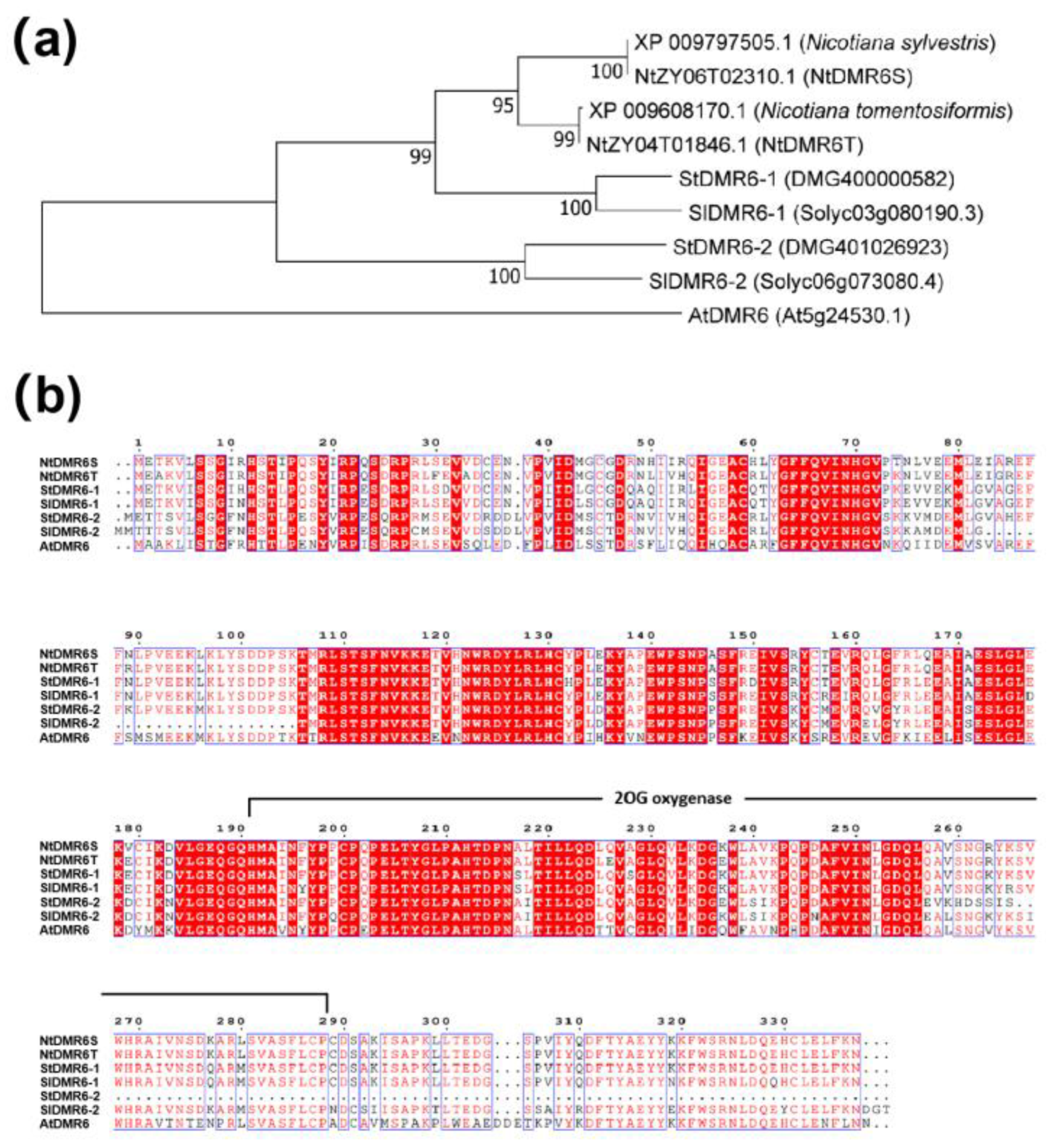

4. Discussion

Nicotiana tabacum (2n = 4x = 48) is a natural allotetraploid resulting from genome duplication. As a consequence, many gene copies are retained, some of which may maintain similar functions, while others may have become silenced through mutations or epigenetic modifications [

33]. For example, the

NtAn1 family members

NtAn1a (originated from

N. sylvestris) and

NtAn1b (originated from

N. tomentosiformis) appeared to be functionally and spatiotemporally redundant [

34]. A pair of plant natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (

NRAMP) homologous genes,

NtNRAMP6a (originated from

N. tomentosiformis) and

NtNRAMP6b (originated from

N. sylvestris) mainly affected the transport of cadmium from roots to shoots. But

NtNRAMP6a had manganese transport activity, while

NtNRAMP6b did not, although the main difference was only 12 amino acids between NtNRAMP6a and NtNRAMP6b protein sequence [

35]. In our study, we identified two DMR6 orthologs in tobacco, NtDMR6T, derived from

N. tomentosiformis, and NtDMR6S, derived from

N. sylvestris. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S clustered with DMR6-1 from other species, suggesting that both proteins may be involved in disease resistance (

Figure 2a). Consistent with this notion, expression analyses showed that both genes are induced by pathogen infection and exhibit similar tissue expression patterns. Nevertheless, their functional roles may have diverged, as promoter analysis revealed distinct profiles of

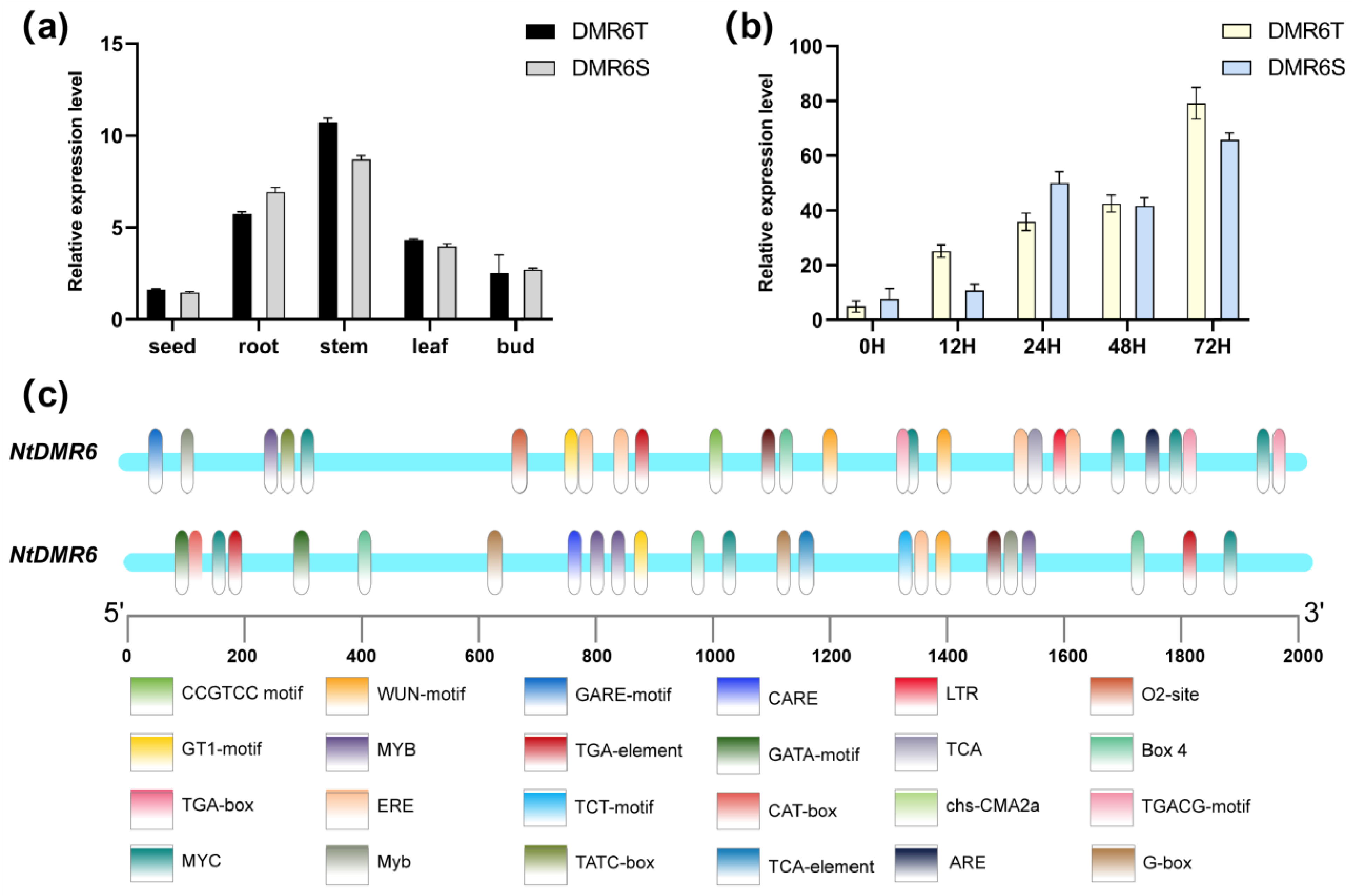

cis-acting regulatory elements.

NtDMR6T harbors a greater number of stress- and hormone-responsive elements, while

NtDMR6S is enriched in light-responsive elements (

Figure 3c). These differences imply that NtDMR6T is likely to be integrated more directly into stress- and hormone-mediated defense networks, while NtDMR6S may be more responsive to environmental or developmental cues. Such divergence suggests that although both genes are pathogen inducible, they may contribute to disease susceptibility through distinct upstream signaling pathways.

In tomato, the

Sldmr6-1 mutants exhibited increased resistance to various classes of tomato pathogens [

16]. In potato,

StDMR6 mutant lines can enhance the resistance to late blight [

36]. In banana, mutants of the

DMR6 orthologue can enhance resistance to

Xanthomonas campestris pv.

musacearum [

37], and in grapevine,

VviDMR6-1 is a candidate gene for susceptibility to downy mildew [

38]. By generating CRISPR/Cas9 mutants of

NtDMR6 genes, we aimed to evaluate whether

NtDMR6T or

NtDMR6S contribute to susceptibility to

P. nicotianae and to gain preliminary insights into their roles in tobacco. Compared to the susceptible control HD, all three mutant lines showed significantly reduced susceptibility to

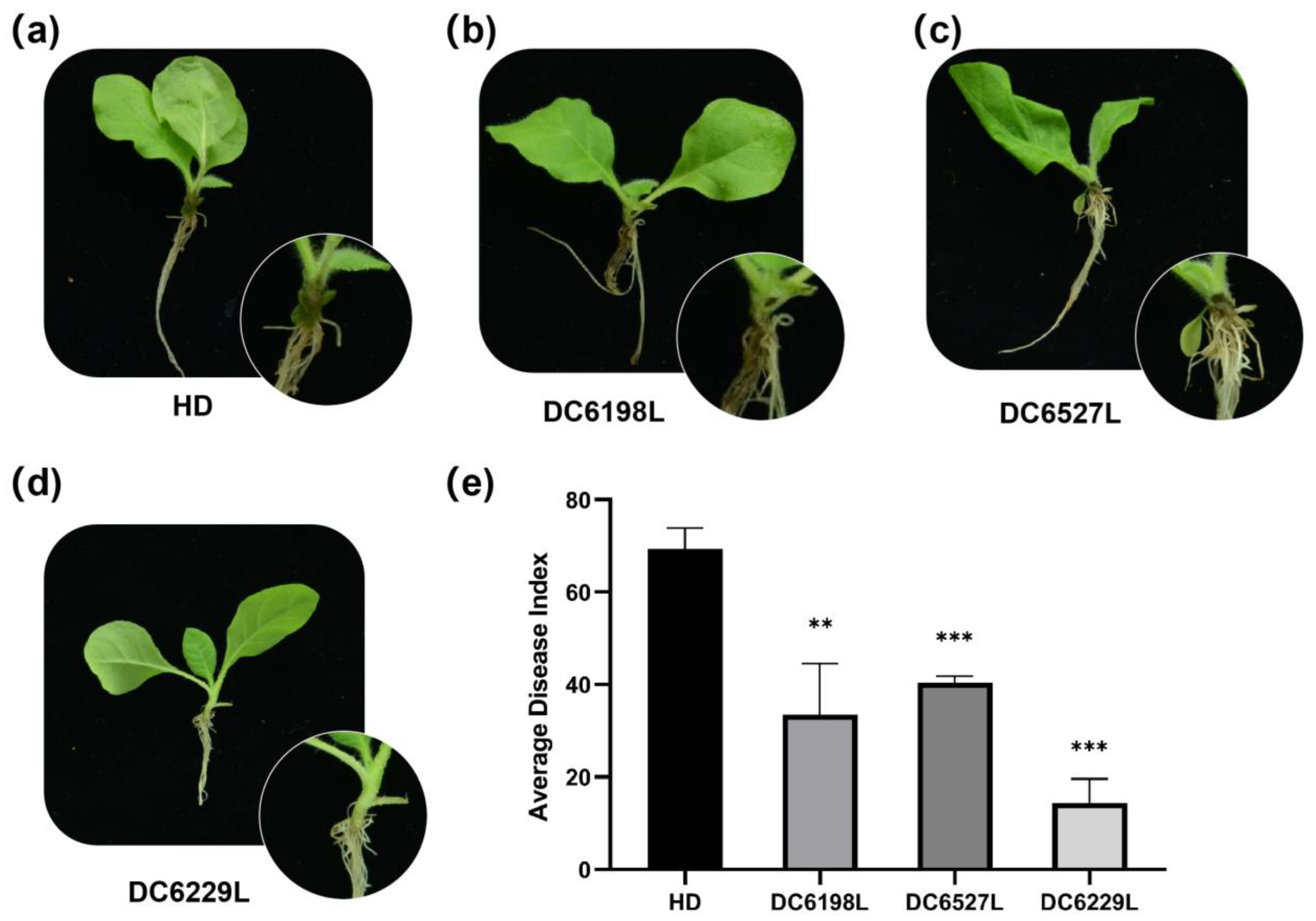

P. nicotianae. Notably, the single mutants DC6527L and DC6198L exhibited similar resistance levels, whereas the double mutant DC6229L showed a significantly lower disease index than either single mutant (

Figure 5). The stronger resistance phenotype of the double mutant implies that

NtDMR6T and

NtDMR6S may function in partially redundant but complementary pathways. Considering the distinct

cis-acting elements in each gene, such redundancy may represent an evolutionary strategy that safeguards susceptibility functions and ensures successful pathogen colonization.

Prior to utilizing impaired

S gene alleles in crop breeding, it is essential to identify and minimize potential negative side effects [

39]. Mutation of

DMR6 can lead to elevated SA levels, which may in turn result in dwarf phenotypes [

40,

41]. In our study, the

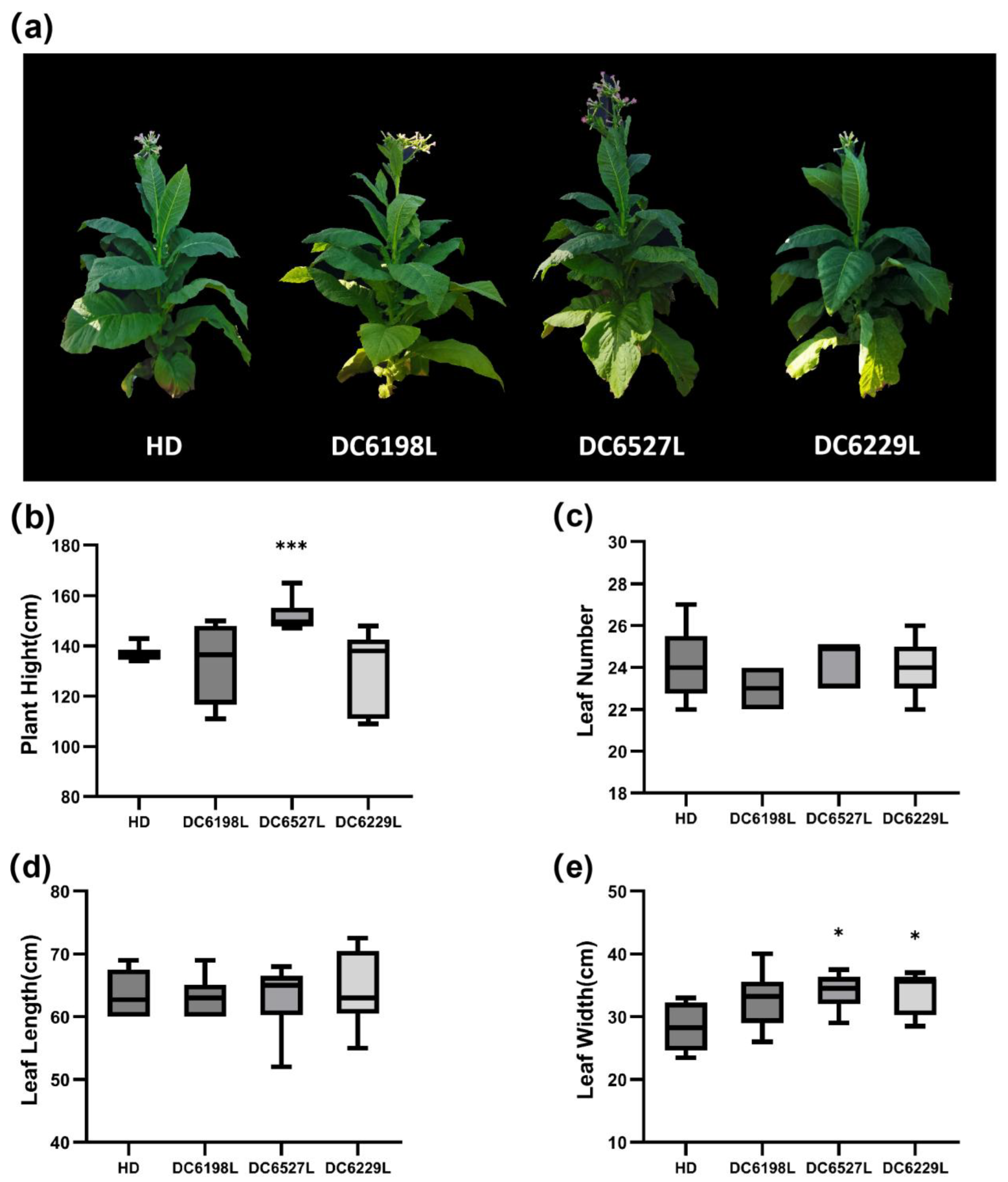

Ntdmr6 mutants—DC6527L, DC6198L, and DC6229L—did not exhibit any growth defects under field conditions (

Figure 6). This observation aligns with previous reports in other species: inactivation of

StDMR6-1 in potato showed no apparent growth penalty [

36], and knockout of

SlDMR6-1 in tomato did not cause detectable growth reduction under laboratory conditions [

16]. RT-qPCR analysis showed that the expression of a subset of plant development-related genes was not altered in DC6229L compared with HD, consistent with the observation that loss of

NtDMR6s did not cause developmental defects. Moreover, the leaves of DC6527L, DC6198L, and DC6229L were significantly wider than those of HD, suggesting that knocking out

NtDMR6s not only enhances disease resistance but may also contribute to increased yield potential. These findings support the notion that

NtDMR6s are promising

S gene targets for improving tobacco resistance without compromising plant growth.

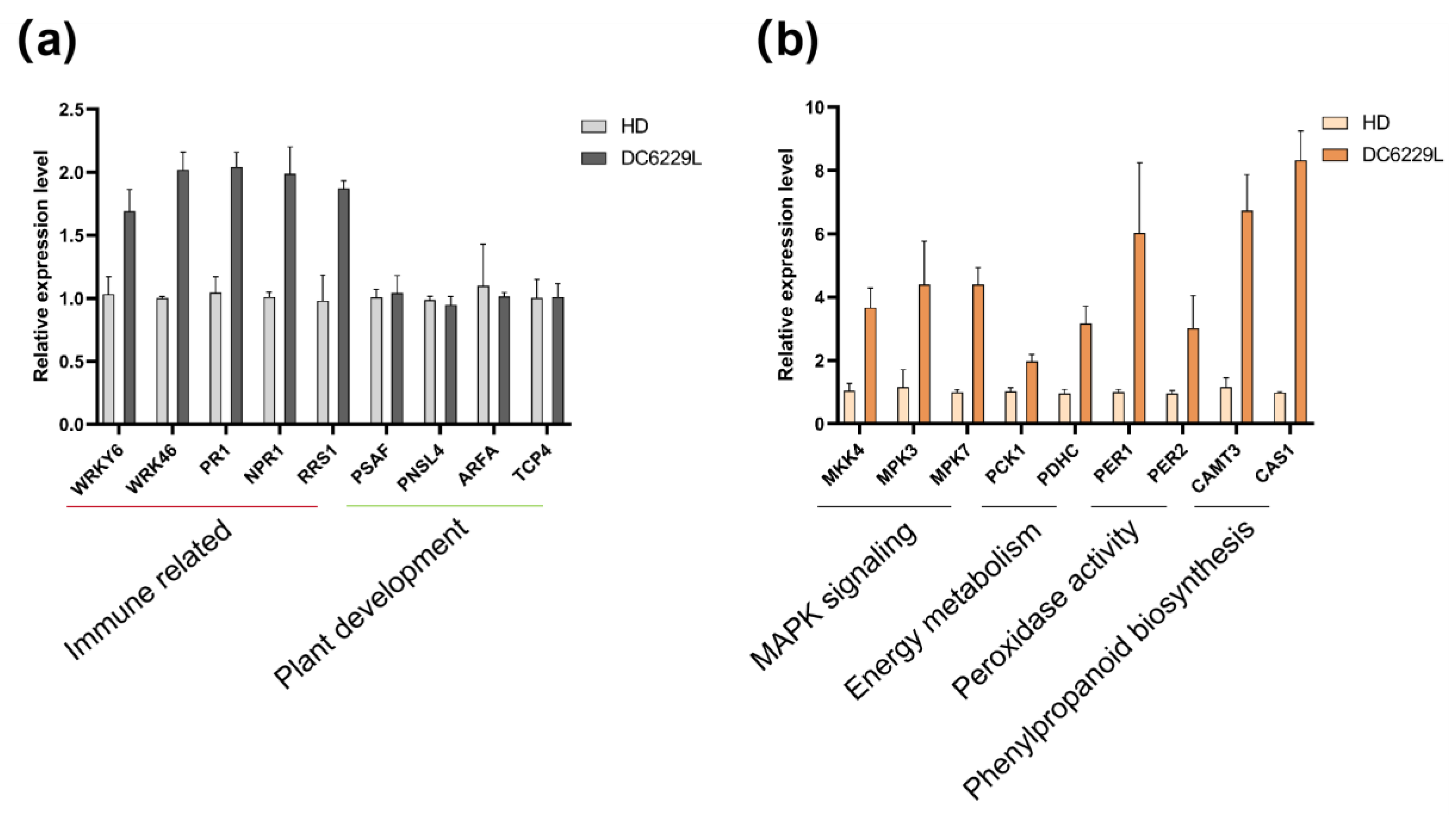

Existing studies have rarely investigated the downstream regulatory pathways regulated by DMR6. Our results indicate that, upon the loss of

NtDMR6s function, SA levels likely increase, as the core regulatory gene

NPR1 was up-regulated in the DC6229L mutant. After

P. nicotianae inoculation, genes associated with POD enzymes, MAPK cascades, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis were markedly up-regulated in DC6229L. These responses are unlikely to act in isolation but are more plausibly downstream amplification effects driven by SA. Specifically, SA accumulation can activate SA-responsive transcription factors (such as

WRKYs;

Figure 7a), which in turn amplify MAPK signaling, induce peroxidase activity to modulate reactive oxygen species, and stimulate the biosynthesis of antimicrobial secondary metabolites, including phytoalexins (

Figure 7b). Future work can focus on the direct downstream targets of

NtDMR6s. Such studies will not only clarify the causal role of DMR6 within SA-centered immune networks but also provide a molecular framework for exploiting S-gene editing to enhance broad-spectrum resistance in tobacco. Future work can focus on identifying the direct downstream targets of

NtDMR6s. This will not only clarify the role of DMR6 within SA-centered immune networks but also provide a molecular framework for leveraging

S gene editing to enhance broad-spectrum resistance in tobacco.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Y.B. and H.M.; methodology, H.W.; software, Z.L. and L.W; validation, L.C., A.Y. and R.V.; formal analysis, R.W.; investigation, H.W.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M. and H.M; writing—review and editing, L.W., L.C., and R.V.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, H.M.; project administration, A.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.L. and L.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

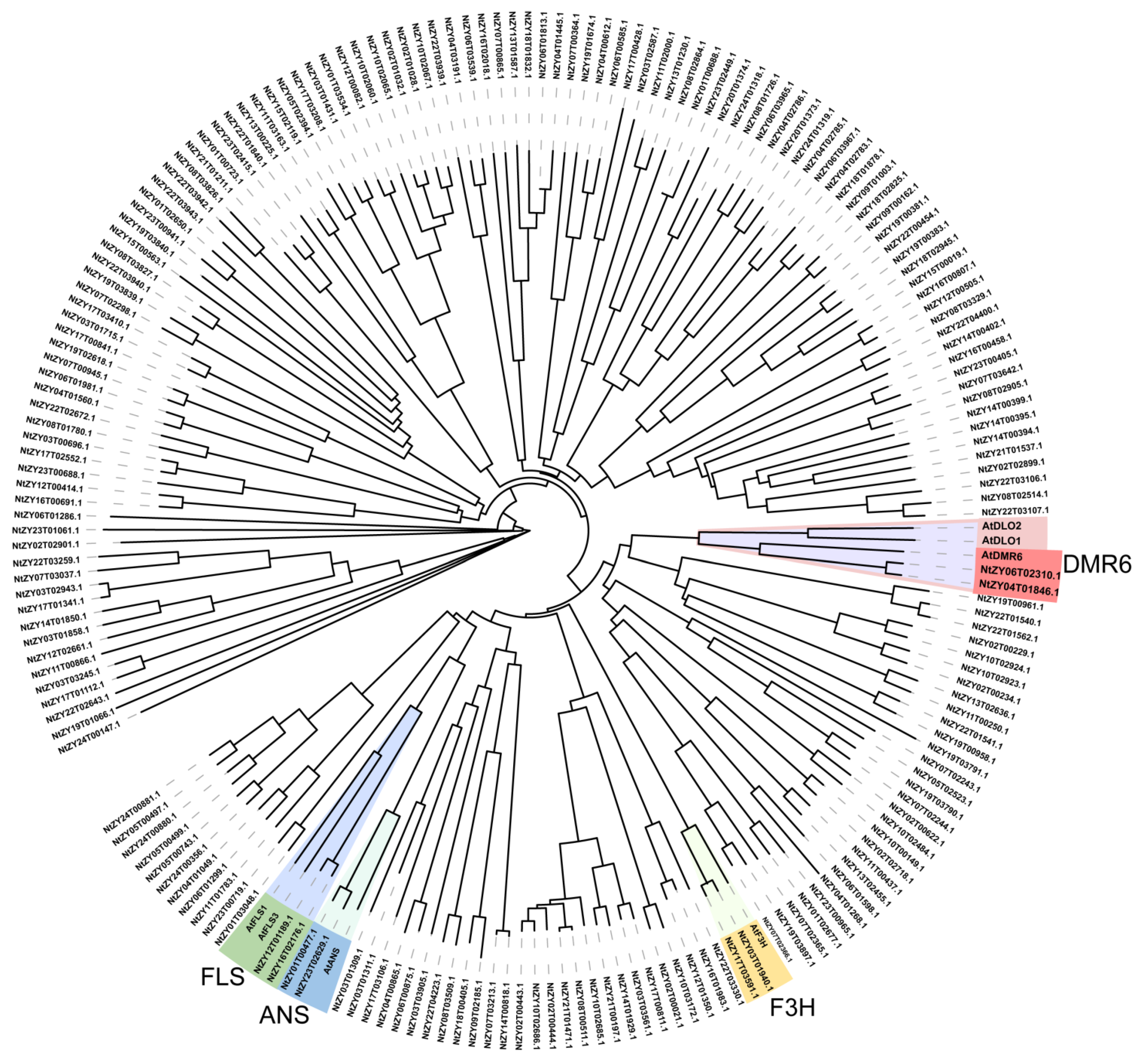

Figure 1.

Identification of AtDMR6 orthologs in tobacco. Phylogenetic tree of the 2OG oxygenases (Pfam domain PF03171) of Nicotiana tabacum with functionally known 2-ODD members in Arabidopsis, including AtDMR6, AtDLO, AtFLS, AtANS, and AtF3H.

Figure 1.

Identification of AtDMR6 orthologs in tobacco. Phylogenetic tree of the 2OG oxygenases (Pfam domain PF03171) of Nicotiana tabacum with functionally known 2-ODD members in Arabidopsis, including AtDMR6, AtDLO, AtFLS, AtANS, and AtF3H.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic and sequence alignment analyses of DMR6 orthologs. (a) Phylogenetic tree of DMR6 orthologs in different plant species, including proteins from N. tabacum, N. tomentosiformis, N. sylvestris, S. lycopersicum, S. tuberosum, and A. thaliana. The scale bar indicates amino acid substitutions per site. Bootstrap support values based on 100 replicates are shown at the nodes. (b) Protein sequence alignment of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S with AtDMR6, SlDMR6-1, SlDMR6-2, StDMR6-1, and StDMR6-2. The conserved 2OG oxygenase domain (Pfam: PF03171) is indicated.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic and sequence alignment analyses of DMR6 orthologs. (a) Phylogenetic tree of DMR6 orthologs in different plant species, including proteins from N. tabacum, N. tomentosiformis, N. sylvestris, S. lycopersicum, S. tuberosum, and A. thaliana. The scale bar indicates amino acid substitutions per site. Bootstrap support values based on 100 replicates are shown at the nodes. (b) Protein sequence alignment of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S with AtDMR6, SlDMR6-1, SlDMR6-2, StDMR6-1, and StDMR6-2. The conserved 2OG oxygenase domain (Pfam: PF03171) is indicated.

Figure 3.

Gene expression patterns of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S. (a) Expression pattern of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S in different tissues, including seed, root, stem, leaf, and bud. (b) Time-course expression of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S following inoculation with P. nicotianae (race 0) at 0, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-infection. (c) Distribution of cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of the two NtDMR6 genes. Colored rectangles represent different cis-elements.

Figure 3.

Gene expression patterns of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S. (a) Expression pattern of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S in different tissues, including seed, root, stem, leaf, and bud. (b) Time-course expression of NtDMR6T and NtDMR6S following inoculation with P. nicotianae (race 0) at 0, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-infection. (c) Distribution of cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of the two NtDMR6 genes. Colored rectangles represent different cis-elements.

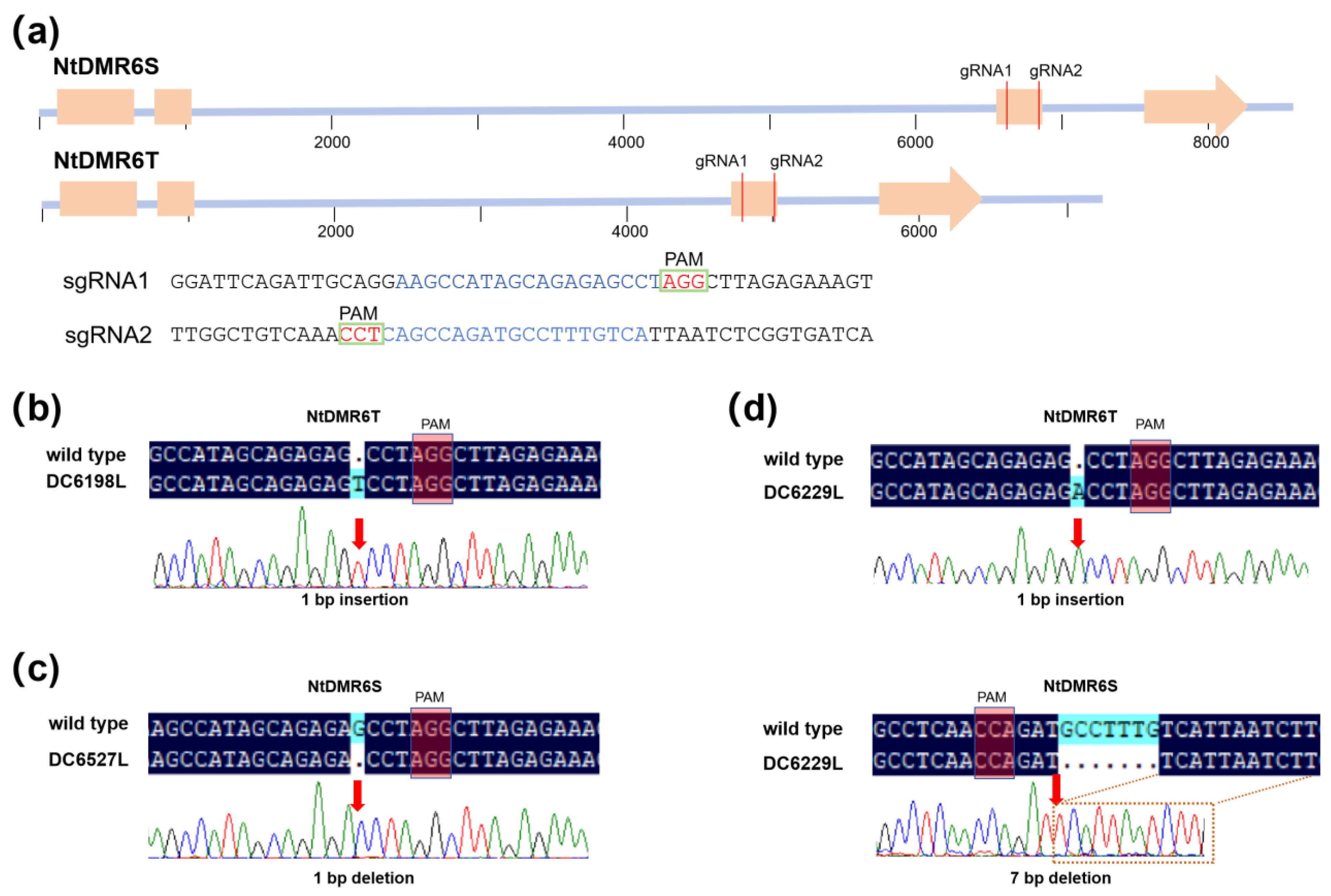

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of NtDMR6-specific gRNAs and mutant alleles. (a) Genomic structure of NtDMR6S and NtDMR6T showing the positions of two gRNAs designed to generate knockout mutants. The target sequences of gRNA1 and gRNA2 are shown, with the PAM sequence highlighted. (b) DC6198L, a homozygous line carrying a 1-bp insertion in NtDMR6T, while NtDMR6S remains unchanged. (c) DC6527L, a homozygous line carrying a 1-bp deletion in NtDMR6S, while NtDMR6T remains unchanged. (d) DC6229L, a homozygous line carrying a 1-bp insertion in NtDMR6T and a 7-bp deletion in NtDMR6S. The arrows indicate the positions of insertions or deletions that result in frame-shift mutations in the protein sequence.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of NtDMR6-specific gRNAs and mutant alleles. (a) Genomic structure of NtDMR6S and NtDMR6T showing the positions of two gRNAs designed to generate knockout mutants. The target sequences of gRNA1 and gRNA2 are shown, with the PAM sequence highlighted. (b) DC6198L, a homozygous line carrying a 1-bp insertion in NtDMR6T, while NtDMR6S remains unchanged. (c) DC6527L, a homozygous line carrying a 1-bp deletion in NtDMR6S, while NtDMR6T remains unchanged. (d) DC6229L, a homozygous line carrying a 1-bp insertion in NtDMR6T and a 7-bp deletion in NtDMR6S. The arrows indicate the positions of insertions or deletions that result in frame-shift mutations in the protein sequence.

Figure 5.

Wild type HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines infected with P. nicotianae at 5 days post inoculation. (a–d) Disease symptoms of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines, DC6198L, DC6527L, and DC6229L. Inoculation was performed using the suspension of P. nicotianae zoospores at 105 zoospores/mL. (e) Average disease index of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines. **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

Wild type HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines infected with P. nicotianae at 5 days post inoculation. (a–d) Disease symptoms of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines, DC6198L, DC6527L, and DC6229L. Inoculation was performed using the suspension of P. nicotianae zoospores at 105 zoospores/mL. (e) Average disease index of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines. **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t-test.

Figure 6.

Morphological characteristics of wild type HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines in the field. (a) Growth phenotype of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines. (b) Plant height, (c) leaf number, (d) leaf length, and (e) leaf width of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t-test.

Figure 6.

Morphological characteristics of wild type HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines in the field. (a) Growth phenotype of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines. (b) Plant height, (c) leaf number, (d) leaf length, and (e) leaf width of HD and Ntdmr6 mutant lines. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t-test.

Figure 7.

RT-qPCR analysis of selected genes in wild-type HD and DC6229L mutant after P. nicotianae inoculation. (a) Relative expression levels of immune related genes (WRKY6, WRKY46, PR1, NPR1, RRS1) and plant development related genes (PSAF, PNSL4, ARFA, TCP4) at 0 hpi, as determined by RT-qPCR. (b) Relative expression levels of genes associated with MAPK signaling (MKK4, MPK3, MPK7), energy metabolism (PCK1, PDHC), peroxidase activity (PER1, PER2), and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (CAMT3, CAS1) at 48 hpi. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Figure 7.

RT-qPCR analysis of selected genes in wild-type HD and DC6229L mutant after P. nicotianae inoculation. (a) Relative expression levels of immune related genes (WRKY6, WRKY46, PR1, NPR1, RRS1) and plant development related genes (PSAF, PNSL4, ARFA, TCP4) at 0 hpi, as determined by RT-qPCR. (b) Relative expression levels of genes associated with MAPK signaling (MKK4, MPK3, MPK7), energy metabolism (PCK1, PDHC), peroxidase activity (PER1, PER2), and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (CAMT3, CAS1) at 48 hpi. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Table 1.

Overview of the mutation events in the tobacco NtDMR6 CRISPR mutants.

Table 1.

Overview of the mutation events in the tobacco NtDMR6 CRISPR mutants.

| Event |

NtDMR6T |

NtDMR6S |

T2-Plants |

T3-Lines |

| 1 |

1-bp (T) insertion at gRNA1 |

no mutation |

DC6198 |

DC6198L |

| 2 |

no mutation |

1-bp (G) deletion at gRNA1 |

DC6527 |

DC6527L |

| 3 |

1-bp (A) insertion at gRNA1 |

7-bp deletion at gRNA2 |

DC6229 |

DC6229L |