1. Introduction

Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) integrate PV modules into the building envelope and represent a key technology for achieving Zero Energy Building (ZEB) targets through on-site power generation [

1,

2,

3]. BIPV systems eliminate the need for additional land for PV installation and are increasingly recognized as a high-value technology that can replace conventional building finishes. Nevertheless, their acceptance within the construction industry remains limited due to insufficient design information available to architects, low awareness among practitioners, and aesthetic concerns. To address these issues, colored PV modules in diverse colors have been developed, enabling BIPV systems to provide both power generation and architectural integration. These colored BIPV systems are gradually being adopted in the market, offering aesthetic appeal and harmony with building finishes [

4,

5].

However, unlike conventional BIPV systems, colored BIPV systems exhibit different performance characteristics in terms of temperature, electrical efficiency, and other factors due to the optical properties of the materials used, such as reflectance and transmittance, and thermal transfer differences based on rear insulation conditions. Therefore, a comprehensive performance evaluation considering these factors is necessary [

6].

Tzikas et al. compared conventional PV modules with gray-colored modules and reported an efficiency reduction of approximately 8–10% for the gray modules [

7]. Nicolas et al. investigated a colored BIPV system installed on the Kohlesilo building in Basel, Switzerland, employing crystalline silicon glass-to-glass modules in five colors (black, green, blue, gray, and gold). Relative to black modules, gray and gold modules yielded approximately 76% of the energy output, while green and blue modules reached about 84% [

8]. Kutter et al. developed colored PV modules using ceramic-colored glass, Morpho-structure, and colored encapsulants, and evaluated their performance under STC conditions. Modules with ceramic-colored glass and colored encapsulants exhibited efficiency losses of 6–31% compared to standard PV modules, whereas Morpho-structured modules showed much smaller reductions of 3–7% regardless of color [

9]. Kroyer et al. corroborated these findings, demonstrating that red, green, and blue Morpho-structured modules maintained efficiency losses below 7% [

10].

Roverso et al. examined colored BIPV façades, measuring solar radiation and module temperature, and demonstrated that the Ross coefficient effectively represents the correlation between incident solar energy and internal module temperature [

11]. Babin et al. conducted outdoor experiments with modules in terracotta, green, red, beige, and gray, integrated into BIPV façades. They found no direct correlation between total optical losses and module temperature. However, higher reflectance reduced absorbed energy, contributing to lower module heating. Notably, lighter-colored modules, such as gray and beige, exhibited rear-surface temperatures up to 5 K lower than standard modules [

12]. Saretta et al. analyzed clear, blue, light gray, dark gray, and terracotta BIPV modules under STC and outdoor conditions. Dark gray modules exhibited the lowest Pmax (13.43%), whereas blue modules achieved the highest efficiency among colored types. Outdoor experiments revealed color-dependent variations in efficiency and operating temperature; terracotta modules produced the lowest efficiency (~9.0%) but exhibited operating temperatures similar to clear modules (~45 °C) [

13]. Pelle et al. further highlighted that color layers induce distinct thermal behaviors, with Ross coefficients ranging from 0.0242 K·m²/W (white) to 0.0456 K·m²/W (mahogany brown), underscoring the significant role of color in thermal sensitivity [

14].

Zhihao et al. investigated crystalline silicon colored BIPV modules incorporating dielectric multilayer coatings and showed that optimized optical interference designs can achieve conversion efficiencies above 21% with photocurrent losses below 5% [

15]. Yuning et al. developed high-efficiency colored crystalline silicon PV modules in red, yellow, blue, green, and white using pearlescent pigments via screen printing. Their analysis indicated that efficiency losses were consistently below 20%, with green modules exhibiting the highest photocurrent density and lowest loss rates [

16]. Mahamoud et al. studied monocrystalline solar cells with colored filters under real climate conditions and found that relative power production strongly depended on filter color, yielding approximately 73% for yellow, 64% for red, and 54% for blue [

17]. Røyset et al. analyzed the application of optical interference coatings and provided design guidelines for balancing high color lightness, low efficiency losses, color performance, and angular dependence [

18].

Babin et al. also evaluated the long-term DC performance ratio (PR) of colored PV modules. Their results revealed that reference and green modules exhibited the lowest annual PR (~0.86), while gray, beige, and terracotta modules achieved slightly higher values (0.88–0.89). Interestingly, red modules demonstrated the highest PR (~0.95), partly attributed to spectral mismatch gains during afternoon hours [

19].

Overall, prior studies consistently demonstrate that colored BIPV systems provide enhanced architectural integration but typically incur efficiency penalties due to optical and thermal effects. However, the magnitude of these penalties depends strongly on the coloration technique, the overall system configuration with the chosen building materials, and the environmental conditions. In particular, experimental evidence on glass-to-glass (G/G) crystalline silicon modules with gray coloration under practical building-like conditions remains limited.

This study aims to analyze the temperature characteristics and electrical performance of BIPV systems equipped with gray-colored glass-to-glass (G/G) crystalline silicon modules. To evaluate the impact of coloration, the results are compared with those of a conventional non-colored BIPV system. An air layer and rear insulation material were incorporated to replicate practical installation conditions. The gray coloration of the PV modules was selected considering aesthetics, harmony with surrounding buildings, and electrical efficiency. The modules were fabricated using digital printing technology, which ensures high color quality while minimizing power losses associated with coloration.

2. Experiment

2.1. BIPV Full-Scale Mock-Up Building

An 89 m² full-scale mock-up building was constructed in Jeollabuk-do, South Korea, to evaluate the functionality and performance of a multifunctional façade based on a post-and-beam structure. The building consists of three identical, air-conditioned rooms, enabling controlled experimental environments by replacing the exterior walls with BIPV façades. This design allows for a comparative evaluation of different PV integration types, including BIPV and BAPV, under simulated real installation conditions.

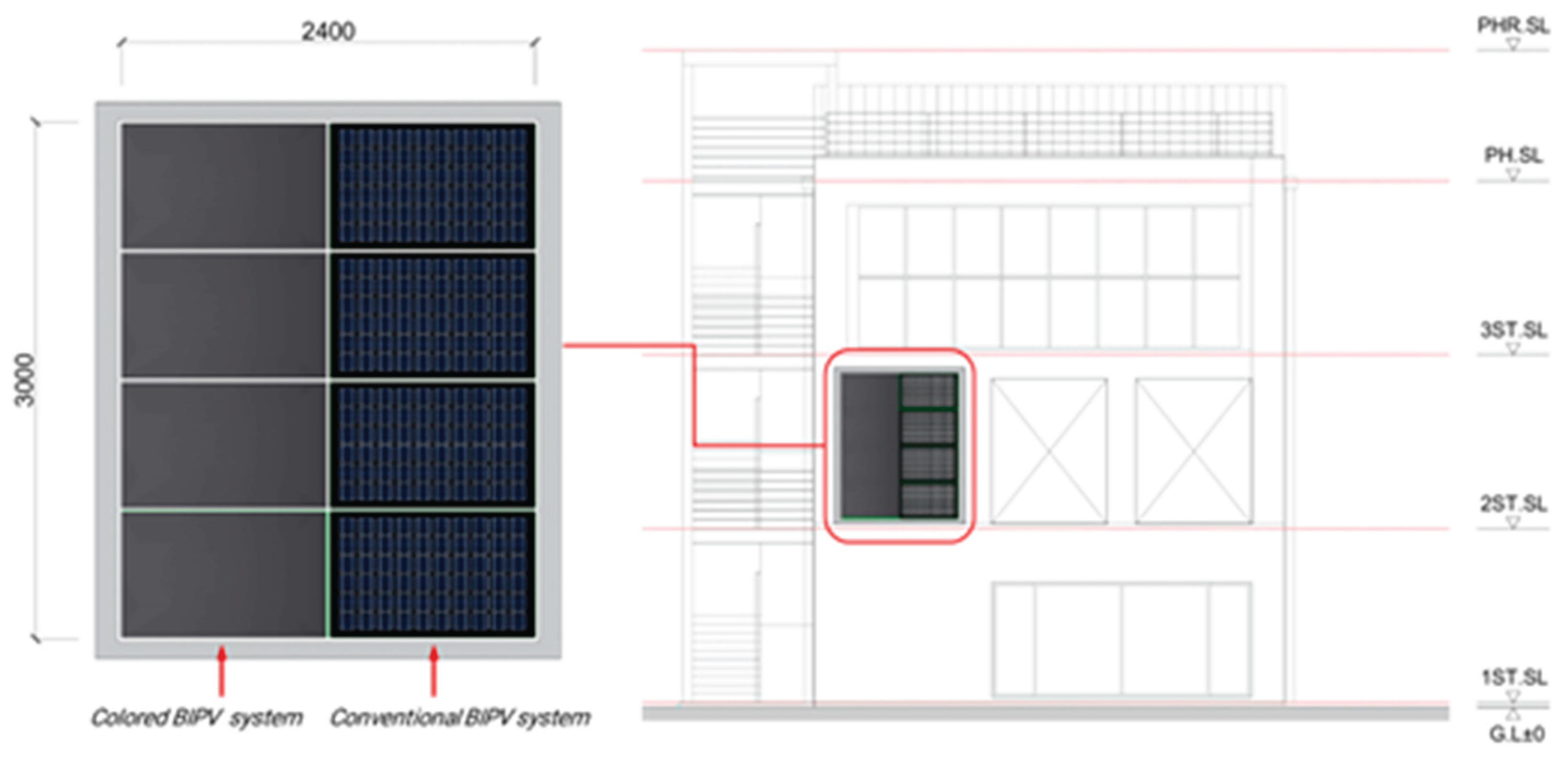

The gray BIPV system was installed on the south-facing exterior wall of the two-story building, and for comparison, a conventional BIPV system was mounted under the same configuration. The test wall had dimensions of 2,400 mm in width and 3,000 mm in height, accommodating a total of eight modules (700 × 1,150 mm each) arranged in two arrays of four modules.

Figure 1 illustrates the installation layout, and

Table 1 summarizes the detailed specifications of the conventional and gray PV modules applied in the BIPV systems.

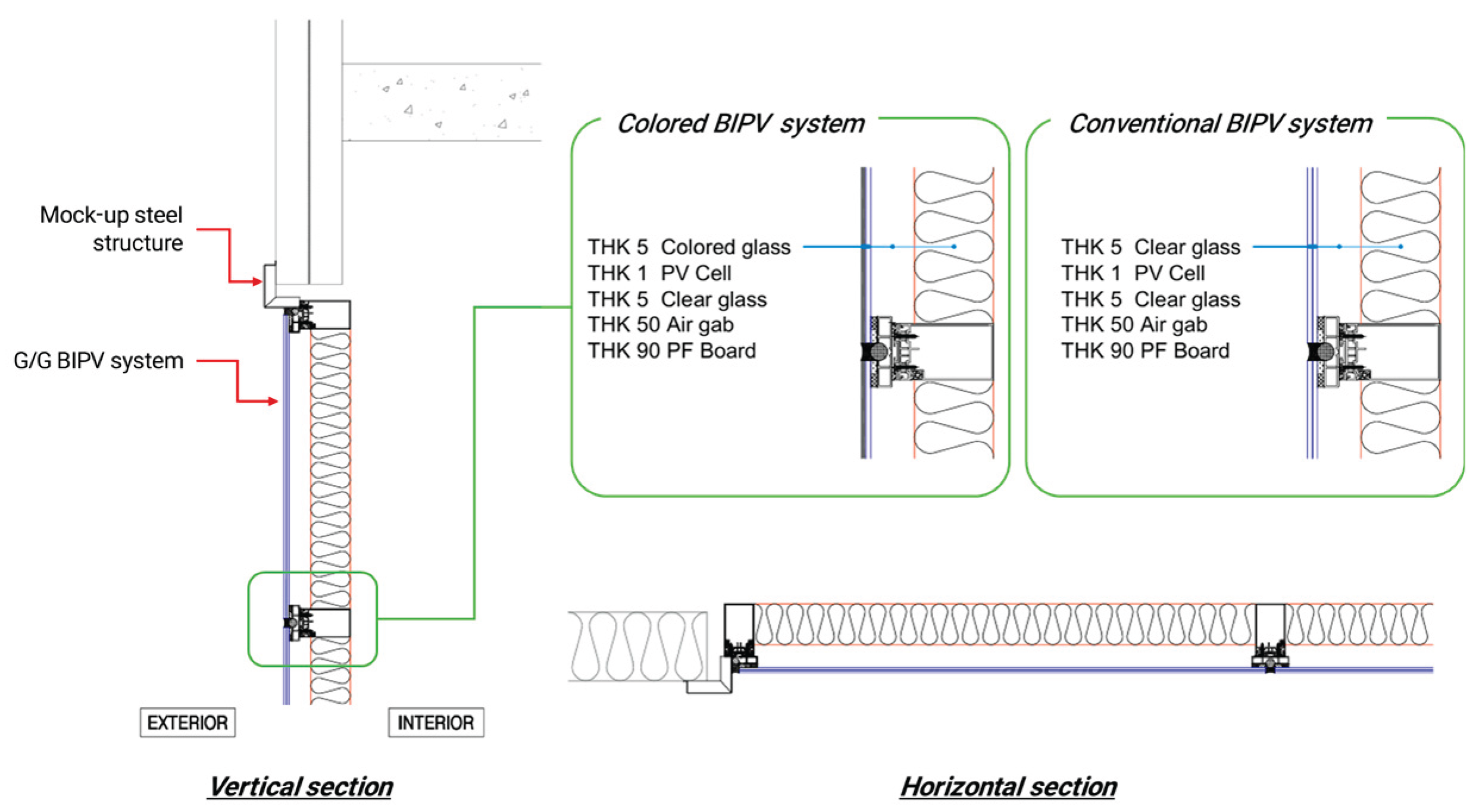

2.2. BIPV System Design Detail

For a comparative analysis of electrical performance between the gray-colored BIPV system and the conventional BIPV system, excluding the color elements of the front glass, the PV cell and the rear structure (BIPV layer configuration) were designed identically. The wall structure of the BIPV system mimics the spandrel part of a curtain wall structure and is designed to meet South Korea’s exterior wall insulation standards (U-value 0.24 W/m²K). The width of the internal air layer in the BIPV system is approximately 50 mm, and the insulation material has a thickness of 90 mm (

Figure 2).

Figure 3 illustrates the layout of the gray-colored BIPV system and the conventional BIPV system installed under identical experimental conditions in the mock-up buildings, as shown in

Figure 4.

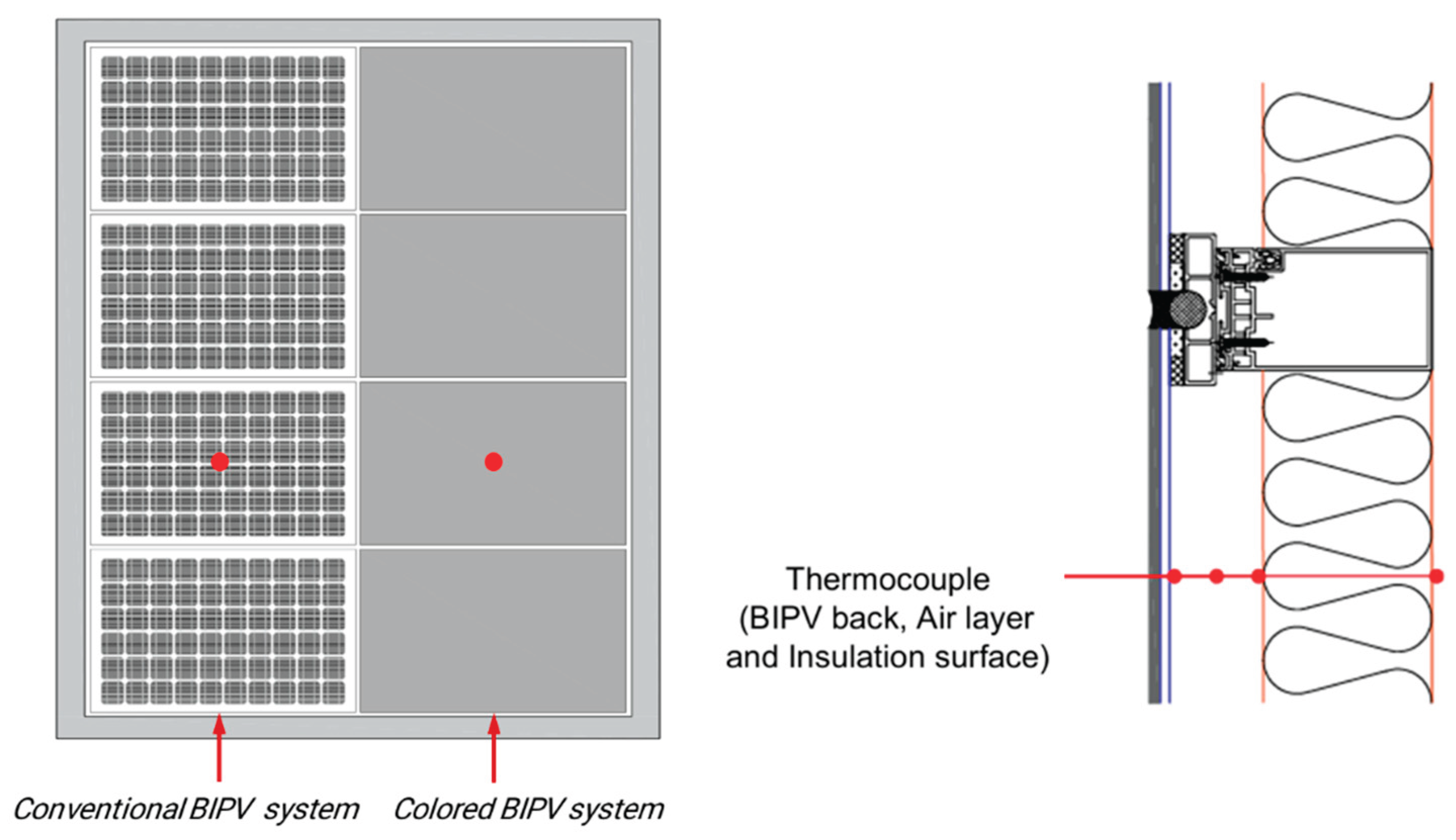

The temperature sensors installed in the two types of BIPV systems are presented in

Figure 5, which also provides detailed positions of the sensors placed on the rear surface of the modules, within the air gap, on the surface of the insulation layer, and on the interior surface.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the installation of conventional and gray-colored BIPV modules, which are integrated with special designed mounting frames for BIPV system, as well as interior view of the mock-up building where the systems are installed.

2.3. Monitoring Systems and Measuring Instruments

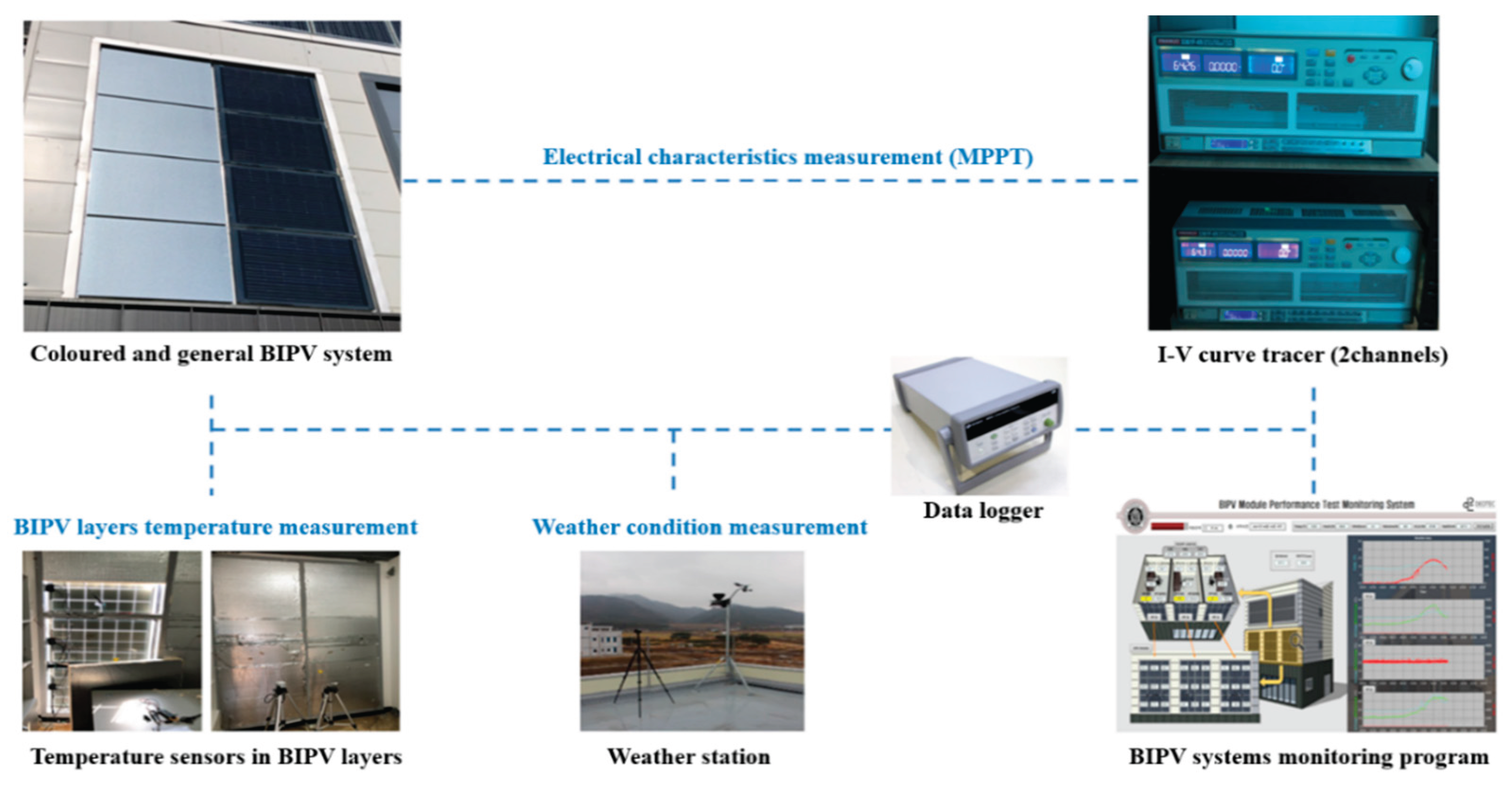

The

Figure 8 illustrates the experimental setup and measuring equipment for the gray and conventional BIPV systems of the building. Both the gray and conventional BIPV systems are connected to an I-V curve tracer, and the power generation performance (e.g. Pmax, Vmp, Imp, Voc, Isc) is measured in Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) mode. Additionally, a weather station is installed on the rooftop of the building to measure experimental environmental conditions (e.g. solar radiation, ambient temperature, humidity), and a data logger collects the measured values.

Furthermore, to analyze the temperature characteristics of the BIPV system, T-type thermocouples are installed internally. Four temperature sensors each are attached to the rear of the PV modules in the BIPV system, the internal air layer, and the inner and outer surfaces of the insulation material (air gap surface and inside surface). All measurement data are collected at 10-second intervals, and the detailed specifications of the measuring equipment used in the experiment are presented in 오류! 참조 원본을 찾을 수 없습니다..

Table 2.

Detail of the measuring equipment used in the experiment.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temperature Distribution of the BIPV Systems

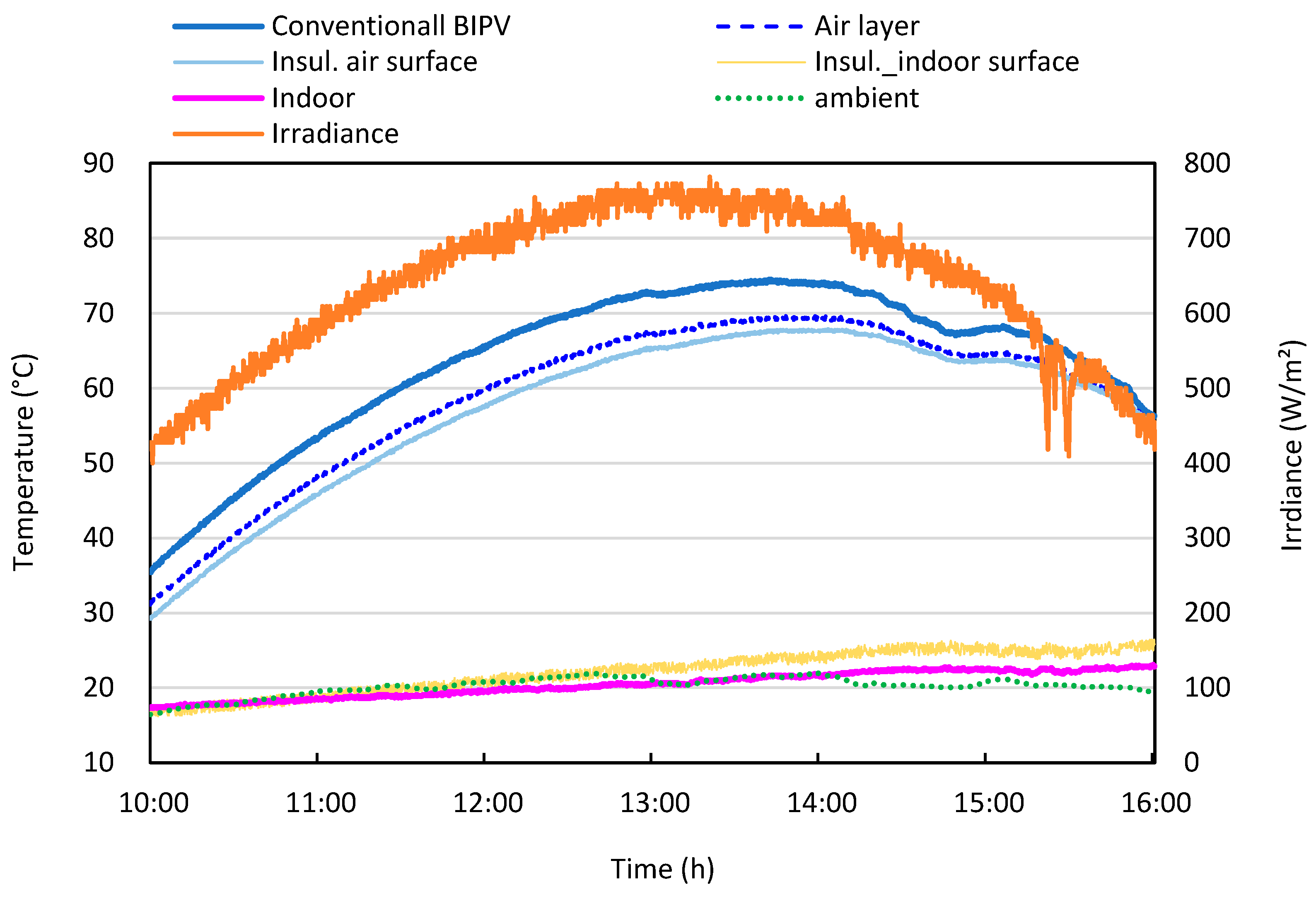

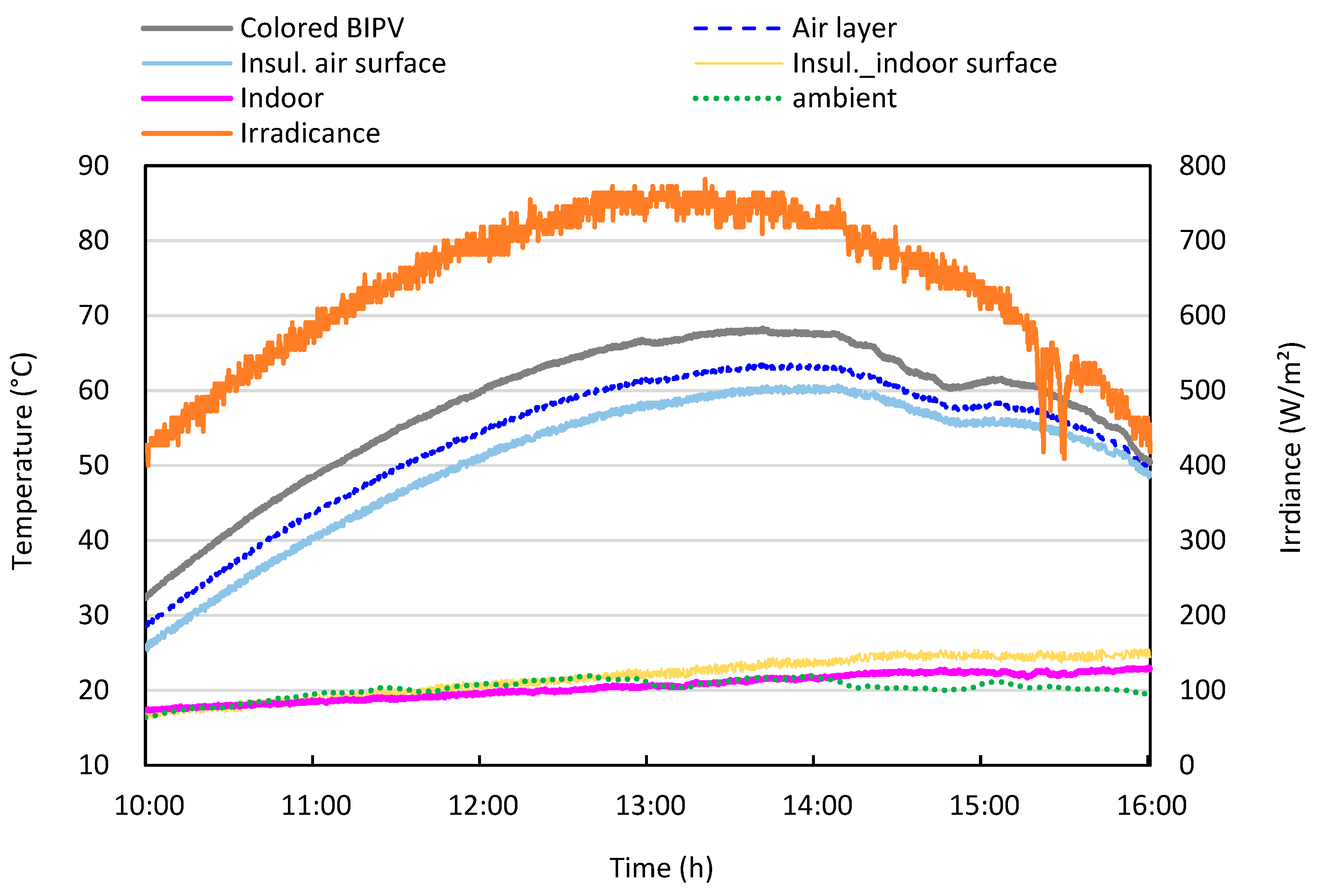

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 depict the temperature characteristics of the applied gray and conventional BIPV systems on the building. The outdoor performance experiment for the BIPV systems was conducted in October, during which the ambient conditions exhibited irradiation ranging from approximately 400 W/m² to 780 W/m² and outdoor temperatures fluctuated between 18°C and 21°C. The rear temperature of the gray BIPV modules ranged from approximately 33°C to 68°C, while the rear temperature of the conventional BIPV modules ranged from about 35°C to 75°C. The rear temperature of the gray BIPV modules was up to 8°C lower than that of the conventional BIPV modules. The temperature in the air layer within the BIPV system was measured to be 5 - 6°C lower compared to each module’s rear temperature. The temperature difference in the air layer for each BIPV system showed a similar pattern to the temperature difference in the module. The temperature of each component in the BIPV system decreased in the following order: BIPV module rear, air layer, insulation surface facing the air layer, and interior insulation surface. That is, the temperature was lower towards the interior.

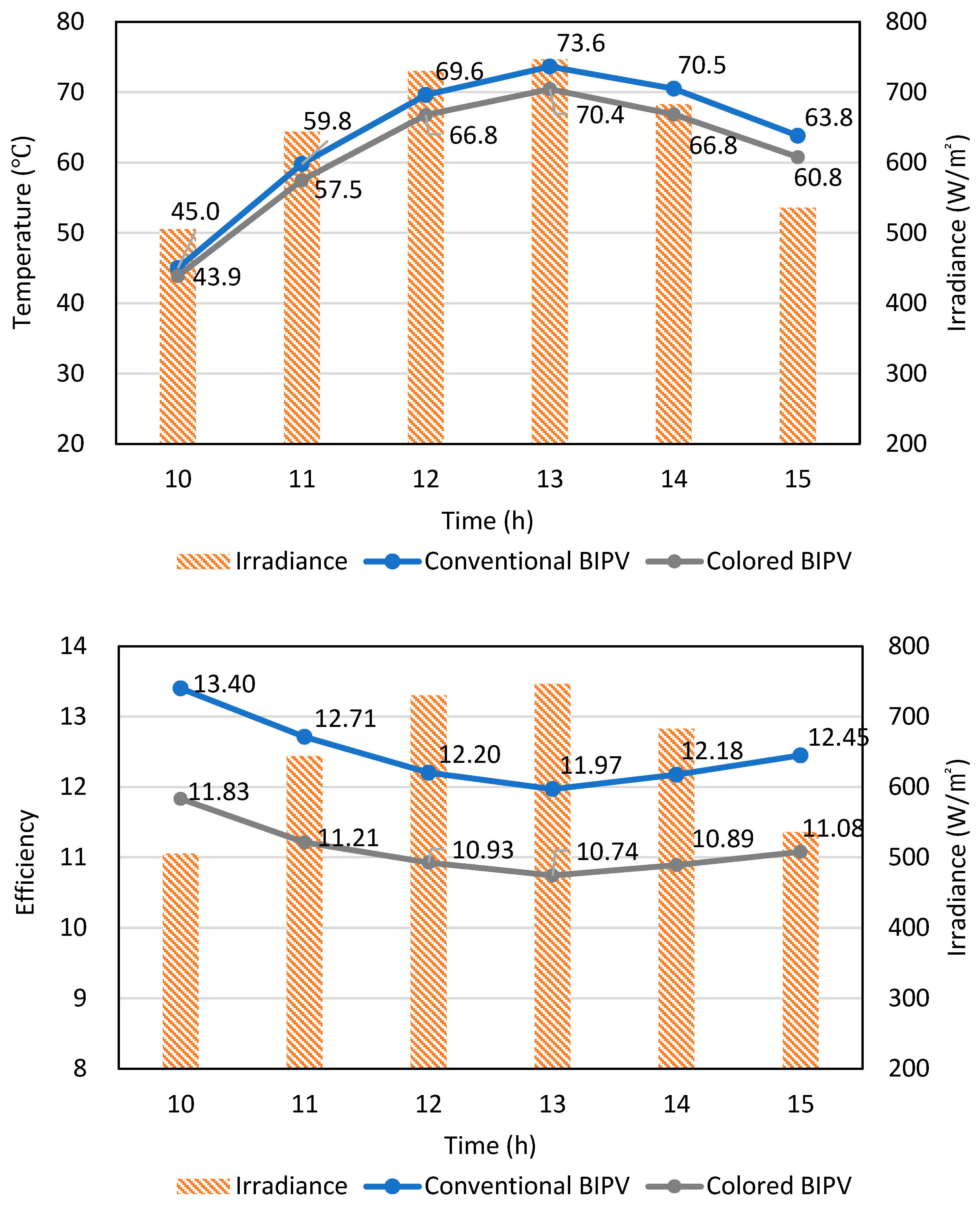

3.2. Hourly Power and Efficiency Comparison

Figure 11 presents the comparative thermal and electrical performance of conventional and colored BIPV modules under identical outdoor conditions. Both systems exhibited a distinct temperature rise with increasing irradiance, reaching their maximum values around 13:00. The peak rear-surface temperature of the conventional BIPV module was approximately 73.6°C, while that of the colored BIPV module was about 70.4°C, indicating that the colored module consistently maintained 2–3°C lower temperatures. This suggests that the colored BIPV system possesses slightly improved heat dissipation characteristics compared to its conventional counterpart.

In terms of electrical efficiency, the conventional BIPV system showed a decrease from 13.4% to 12.4% over the observation period, while the colored BIPV system declined from 11.8% to 11.0%. Although both systems demonstrated a gradual reduction in efficiency with time, the conventional BIPV module consistently outperformed the colored module by approximately 1.5–2 percentage points. This discrepancy can be attributed to optical losses, such as reflection and absorption, introduced by the surface coloring treatment.

The results indicate that the colored BIPV module exhibits a thermal advantage by operating at slightly lower temperatures, but this benefit is offset by reduced optical conversion efficiency. Conversely, the conventional BIPV module achieves higher absolute efficiency but is more vulnerable to performance degradation due to elevated operating temperatures. Furthermore, both systems experienced pronounced efficiency reductions during peak irradiance hours, highlighting the importance of thermal management strategies, such as improved ventilation and heat dissipation designs, for BIPV applications.

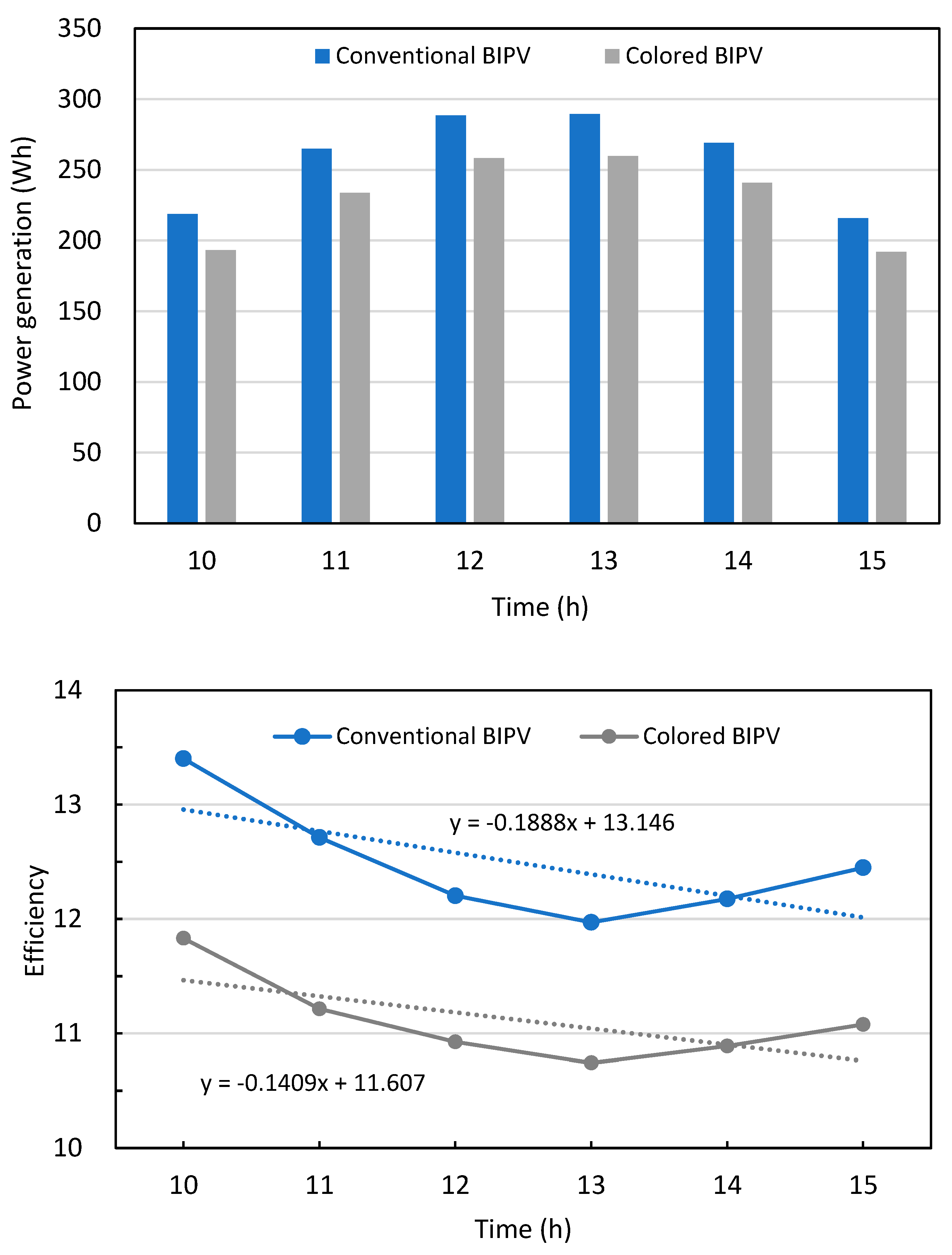

Figure 12 presents the hourly power generation and efficiency profiles of conventional and gray-colored BIPV modules. The conventional BIPV system consistently outperformed the colored BIPV system in terms of power generation across all measured hours. At 13:00, the peak power output of the conventional BIPV module reached approximately 290 Wh, compared to 260 Wh for the colored BIPV module, representing a difference of about 10%. This discrepancy can be attributed to optical losses introduced by the module colorization (gray), such as increased reflection and absorption.

The efficiency trends further emphasize the performance gap between the two systems. The conventional BIPV module showed higher absolute efficiency, ranging from 13.4% in the morning to 12.0% at midday, followed by a slight recovery in the late afternoon. In contrast, the colored BIPV module exhibited consistently lower efficiency values, decreasing from 11.8% to 11.0% during the same period. The regression analysis revealed that the efficiency of the conventional BIPV decreased at a steeper rate (slope = –0.1888) compared to the colored BIPV (slope = –0.1409), indicating a greater sensitivity to increasing operating temperatures.

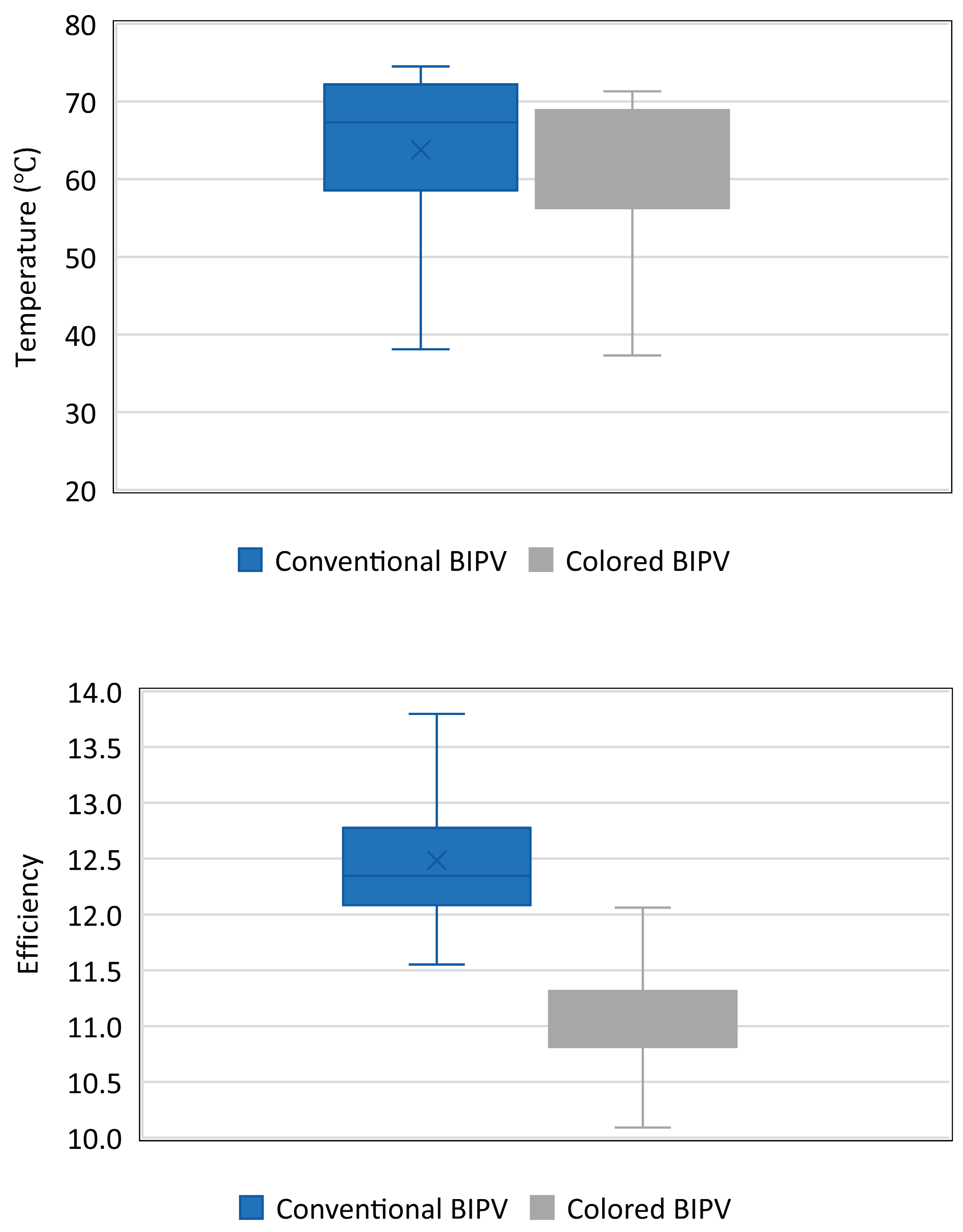

3.3. Statistical and Ross Coefficient Analysis

Figure 13 illustrates the statistical distribution of temperature and electrical efficiency for conventional and colored BIPV modules. The rear-surface temperature of the conventional BIPV modules exhibited a median value of approximately 64°C, with a range between 38°C and 76°C, while the colored BIPV modules showed a lower median of around 61°C and a broader variation from 37°C to 71°C. These results indicate that the colored BIPV modules consistently operate at slightly lower temperatures, suggesting improved heat dissipation characteristics compared to conventional BIPV modules.

In terms of efficiency, the conventional BIPV modules achieved a median value of 12.5%, with the distribution spanning from 11.6% to 13.8%. By contrast, the colored BIPV modules presented a median efficiency of 11.0%, concentrated within a narrower range of 10.1% to 12.1%. This demonstrates that, despite the thermal advantage, the colored BIPV modules suffer from reduced electrical performance due to optical losses introduced by the surface coloring treatment.

Overall, the results highlight a trade-off between thermal and electrical performance: conventional BIPV modules exhibit superior electrical efficiency but are more vulnerable to high operating temperatures, whereas colored BIPV modules demonstrate enhanced thermal stability at the expense of conversion efficiency. These findings emphasize the need for advanced coloring technologies and optimized thermal management strategies to balance aesthetics, temperature regulation, and power generation in BIPV applications.

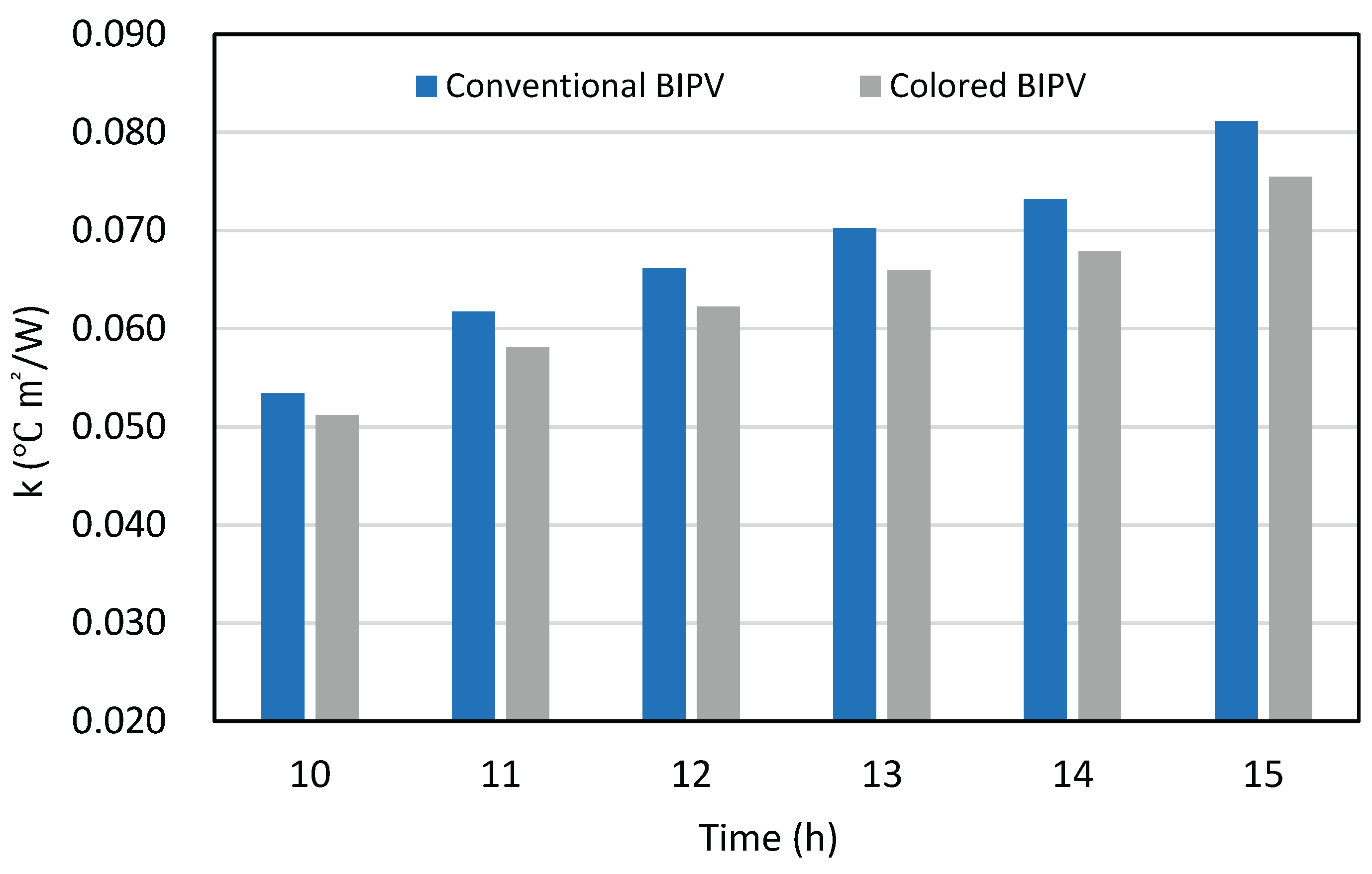

The Ross model is a widely used temperature model in the PV sector. It assumes a linear relationship between the temperature difference of the PV module and the ambient temperature (Tm Ta) and the irradiance on the plane of array (GPOA) (EQ. 1). The constant k, which varies with different boundary conditions, is specific to the module’s design and materials [

20].

Tm = Ta + k ⋅ GPOA (1)

Figure 14 presents the hourly Ross coefficients of conventional and gray-colored BIPV modules. The Ross coefficient (k) serves as an indicator of the thermal sensitivity of PV modules, describing the rate of temperature increase relative to incident irradiance. The conventional BIPV modules exhibited consistently higher Ross coefficients across all time intervals, with values rising from approximately 0.055 at 10:00 to 0.075 at 13:00. In contrast, the colored BIPV modules demonstrated lower coefficients, ranging from 0.045 to 0.070, indicating reduced thermal sensitivity under the same external conditions.

This difference can be attributed to the optical characteristics of the gray-colored surface treatment, which reduces radiative transmittance and mitigates heat accumulation in the modules. The consistently lower Ross coefficients of the colored BIPV modules confirm that they are less prone to temperature elevation compared to conventional BIPV modules.

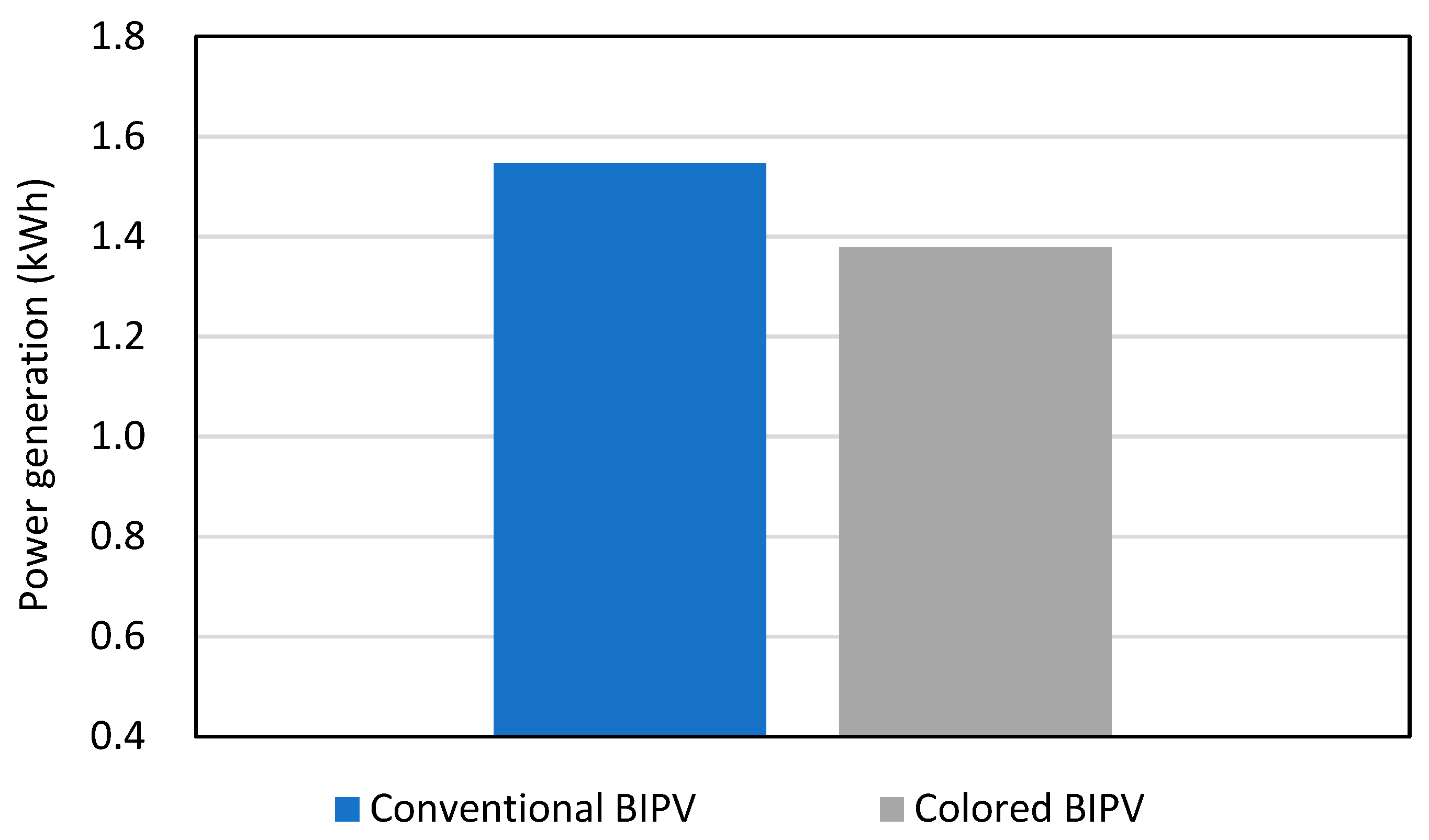

3.4. Daily Power Generation and STC vs. Outdoor Efficiency

Figure 15 compares the daily power generation of conventional and gray-colored BIPV modules. The conventional BIPV system produced approximately 1.55 kWh per day, while the colored BIPV system generated around 1.40 kWh. This corresponds to a reduction of nearly 10% in daily energy yield for the colored BIPV module compared to the conventional system.

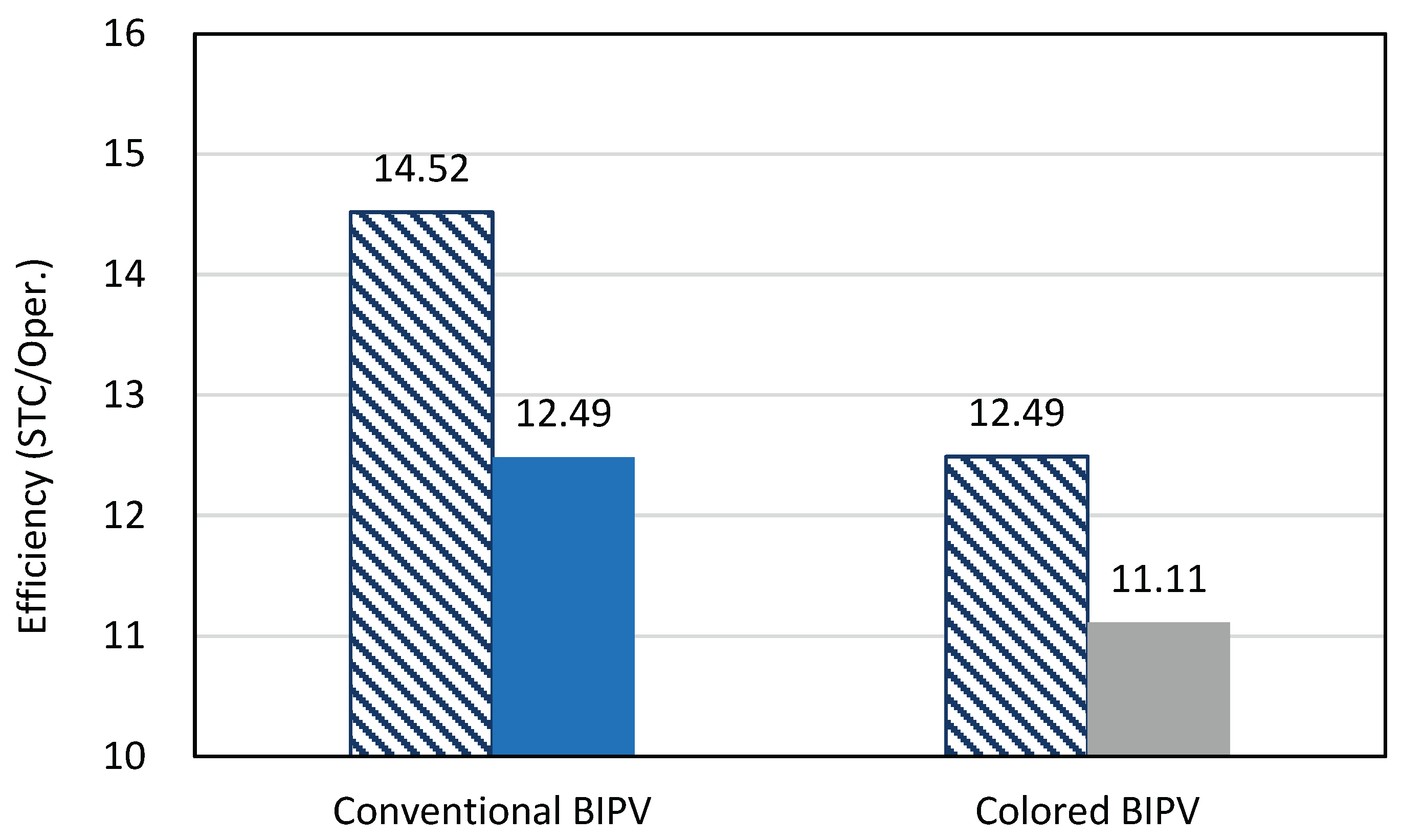

Figure 16 compares the efficiencies of conventional and gray-colored BIPV modules under standard test conditions (STC) and actual outdoor operation. Under STC, the conventional BIPV module achieved an efficiency of 14.52%, while the colored BIPV module recorded 12.49%. Under real operating conditions, both systems showed a reduction in efficiency, with the conventional BIPV at 12.49% and the colored BIPV at 11.11%.

The colored BIPV module consistently exhibited lower efficiency than the conventional module under both STC and outdoor conditions. The efficiency gap was approximately 2%p under STC and 1.4%p under real operating conditions. The relative efficiency losses were calculated to be about 15% for the conventional BIPV and 10% for the colored BIPV. This indicates that the colored module experiences less efficiency loss under real operating conditions compared to the conventional module, reflecting the relatively higher thermal stability of the colored BIPV system.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted an experimental evaluation of the thermal behavior and electrical performance of conventional and gray-colored BIPV systems installed in a full-scale mock-up building.

The outdoor measurements revealed that the maximum rear-surface temperature of the conventional BIPV module reached 75 °C, while the colored BIPV module remained lower at 67 °C. The temperature difference between the two systems varied from 3 to 8 °C depending on the irradiation level, primarily due to thermal energy retention in the rear insulation configuration of BIPV systems.

In terms of electrical performance, the colored BIPV module consistently exhibited lower absolute efficiency than the conventional module, with daily power generation reduced by approximately 10%. However, the relative efficiency loss under real outdoor conditions was lower in the colored BIPV system (≈10%) compared to the conventional system (≈15%), reflecting the relatively higher thermal stability of the colored module. These results indicate that although the application of colorization leads to optical losses and reduced efficiency, it contributes to mitigating the adverse thermal effects on system performance.

In conclusion, the findings highlight a fundamental trade-off between efficiency and aesthetics in BIPV applications. Conventional BIPV modules ensure higher conversion efficiency, while colored BIPV modules offer improved thermal stability and architectural integration potential. Future research should focus on extending the investigation to BIPV systems with various colorizations and insulation configurations, aiming to develop optimized technologies that minimize optical losses while securing adequate energy yield for building applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-H.K. and J.-T.K.; methodology, J.-H.K. and J.-G.A.; validation, J.-H.K.; formal analysis, J.-H.K. and J.-G.A.; investigation, J.-H.K. and J.-G.A.; resources, J.-H.K. and J.-G.A.; data curation, J.-H.K. and J.-G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-H.K.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.K. and J.-T.K.; visualization, J.-H.K.; supervision, J.-T.K.; project administration, J.-H.K. and J.-T.K.; funding acquisition, J.-T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) through the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20229400000130 and RS-2023-00266248).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mohammad, A.K.; Garrod, A.; Ghosh, A. Do Building Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) windows propose a promising solution for the transition toward zero energy buildings? A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Røstvik, H.N.; Steemers, K. The Contribution of Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) to the Concept of Nearly Zero-Energy Cities in Europe: Potential and Challenges Ahead. Energies 2021, 14, 6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylili, A.; Fokaides, P.A. Investigation of building integrated photovoltaics potential in achieving the zero energy building target. Indoor Built Environ. 2013, 23, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelle, M.; Lucchi, E.; Maturi, L.; Astigarraga, A.; Causone, F. Coloured BIPV Technologies: Methodological and Experimental Assessment for Architecturally Sensitive Areas. Energies 2020, 13, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, B.; Messaoudi, P.; Assoa, Y.B.; Thony, P.; Hammoud, R.; Perret-Aebi, L.-E.; Tsanakas, J.A.; Kenny, R.; Serra, J.M. Color coated glazing for next generation BIPV: performance vs aesthetics. EPJ Photovoltaics 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J. G.; Kim, J. H.; and Kim, J. T. , Performance analysis of grey PV module with optical characteristics, Solar Energy 2023, 264, 1–10.

- Tzikas, C.; Valckenborg, R.; Dorenkamper, M.; Donker, M. V. D.; Lozano, L. L.; Bognar, A. , Loonen, R.; Hensen, J.; and Folkerts, W., Outdoor characterization of colored and textured prototype PV facade elements, 35 European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, 2018, 1468–1471.

- Nicolas, J.; Rafic, H.; Jean, C.; and Adreas, S. , colored Solar Façades for Buildings, Energy Procedia 2017, 122, 175–180.

- Kutter, C.; Bläsi, B.; Wilson H., R.; Kroyer, T.; Mittag, M.; Höhn, O.; Heinrich, M. , Decorated Building-Integrated Photovoltaic Modules: Power Loss, Color Appearance and Cost Analysis, The Astrophysical Journal, 2018, 160, 1488-1492.

- Kroyer, T.; Eisenlohr, J.; Bläsi, B.; Höhn, O.; Heinrich, M.; Neuhaus, H.; Kuhn T., E. , Pilot installations of highly efficient coloured BIPV modules with anti-glare coating, Conference on advanced building skins, 2019, 550-555.

- Roverso, R.; Pelle, M.; Dallapiccola, M.; Astigarraga, A.; Lucchi, E.; Ingenhoven, P.; and Maturi, L. , Experimental Assessment and data analysis of colored photovoltaic in the field of BIPV technology application, 38 European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, 2021, 1468–1471.

- Babin, M.; Jóhannsson, I.H.; Jakobsen, M.L.; Thorsteinsson, S. Experimental evaluation of the impact of pigment-based colored interlayers on the temperature of BIPV modules. EPJ Photovoltaics 2023, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saretta, E.; Bonomo, P.; Frontini, F. , BIPV MEETS CUSTOMIZABLE GLASS: A DIALOGUE BETWEEN ENERGY EFFICIENCY AND AESTHETICS, 35th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, 2018, 1472-1477.

- Pelle, M.; Gubert, M.; Dalla Maria, E.; Astigarraga, A.; Avesani, S.; Maturi, L. , Experimental evaluation of the temperature related behaviour of pigment based colored BIPV modules integrated in a ventilated façade, Energy and Buildings, 2024, 323, 1-14.

- Xu, Z.; Matsui, T.; Matsubara, K.; Sai, H. Effect of multilayer structure and surface texturing on optical and electric properties of structural colored photovoltaic modules for BIPV applications. Appl. Energy 2024, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Dai, X.; Lu, S.M.; Ma, T. Colored and patterned silicon photovoltaic modules through highly transparent pearlescent pigments. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amara, M.; Balghouthi, M. Colored filter's impact on the solar cells' electric output under real climatic conditions for application in building integrated photovoltaics. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røyset, A.; Kolås, T.; Nordseth, Ø.; You, C.C. Optical interference coatings for coloured building integrated photovoltaic modules: Predicting and optimising visual properties and efficiency. Energy Build. 2023, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, M.; Andersen, N. L.; Thorning, J. K.; Thorsteinsson, S. ; Yield analysis of a BIPV façade prototype installation, Energy and Buildings, 2024, 322, 114730.

- Ross, R.G. Interface design considerations for terrestrial solar cell modules, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Baton Rouge, La, 1976, pp. 801–806.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

V/ W/m²

V/ W/m² m - 14

m - 14  m

m