Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common malignancies worldwide and remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality [

1]. The disease arises through a multistep process involving genetic mutations and epigenetic dysregulation, with well-established hallmarks including activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway, mutations in KRAS, loss of TP53, and aberrant regulation of apoptosis and proliferation [

2,

3]. Despite advances in targeted therapy and precision oncology, prognosis for advanced CRC remains poor, highlighting the need to identify novel molecular regulators and therapeutic strategies.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and play pivotal roles in cancer biology [

4,

5]. Among them, miR-133A is generally considered a tumor suppressor, with documented functions in regulating apoptosis, proliferation, and metastasis [

6,

7]. Dysregulation of miR-133A has been reported in several cancers, but most studies have examined it as a single entity, without distinguishing between its isoforms [

8]. MIR133 is expressed as three isoforms—miR-133A1, miR-133A2, and miR-133B—each potentially exerting distinct regulatory effects [

9,

10].

Isoform switching in microRNAs is increasingly recognized as a critical regulatory mechanism in cancer biology [

11]. In colorectal cancer, miRNA isoform variation has been implicated in regulating key oncogenic pathways such as KRAS and TP53, highlighting the potential role of isoform-specific expression patterns in tumor heterogeneity, progression, and therapy resistance [

12,

13]. Therefore, isoform-level characterization is essential to fully understand the biological functions of miRNAs in tumorigenesis. In CRC, the contribution of miR-133 isoforms has not been systematically explored.

The present study sought to characterize the isoform-specific transcriptomic effects of miR-133 in CRC. By integrating differential expression, functional enrichment, and comparative analyses across stable cell lines expressing each isoform, we aimed to uncover both shared and divergent regulatory programs of miR-133A1, miR-133A2, and miR-133B. Our results reveal isoform-specific modulation of key oncogenic pathways, providing novel insights into CRC pathogenesis and highlighting potential avenues for biomarker and therapeutic development.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Establishment of Stable Cell Lines

Human colorectal cancer SW48 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO₂. Stable cell lines overexpressing miR-133A1 (SW48-KI133A1), miR-133A2 (SW48-KI133A2), and miR-133B (SW48-KI133B) were generated using lentiviral vectors carrying each isoform under the control of a CMV promoter. Transduced cells were selected in puromycin (2 µg/mL) for two weeks, and expression of each isoform was confirmed by qRT-PCR. Parental SW48 cells served as controls.

RNA Extraction and Quality Assessment

Total RNA was isolated from SW48 parental and stable isoform-expressing cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined by NanoDrop spectrophotometry (Thermo Scientific), and integrity was confirmed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) > 8.0 were used for sequencing.

RNA Sequencing and Data Processing

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to generate 150 bp paired-end reads. Sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB). Raw reads were quality-checked with FastQC, and adapter sequences and low-quality bases were trimmed using Trimmomatic. Clean reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38/hg38) with STAR aligner. Gene- and isoform-level transcript quantification was performed using Salmon and Kallisto, and count matrices were generated for downstream analyses.

Differential Expression Analysis

Differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 in R. Genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log₂ fold change| ≥ 1 were considered significantly differentially expressed. Isoform-level differential usage and potential isoform switching events were assessed with IsoformSwitchAnalyzeR.

Gene Ontology and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Significantly up- and down-regulated genes from each isoform were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses using the clusterProfiler R package. Enrichment significance was defined as false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. Results were visualized as bar plots, bubble plots, and heatmaps using ggplot2 and pheatmap packages.

Clustering and Visualization of Differentially Expressed Genes

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and heatmap visualization of differentially expressed genes were performed using the pheatmap package in R. Log₂-transformed normalized counts were used to assess similarities across replicates and isoforms. Venn diagrams and scatter plots were generated with VennDiagram and EnhancedVolcano packages to highlight overlaps and isoform-specific expression profiles.

Discussion

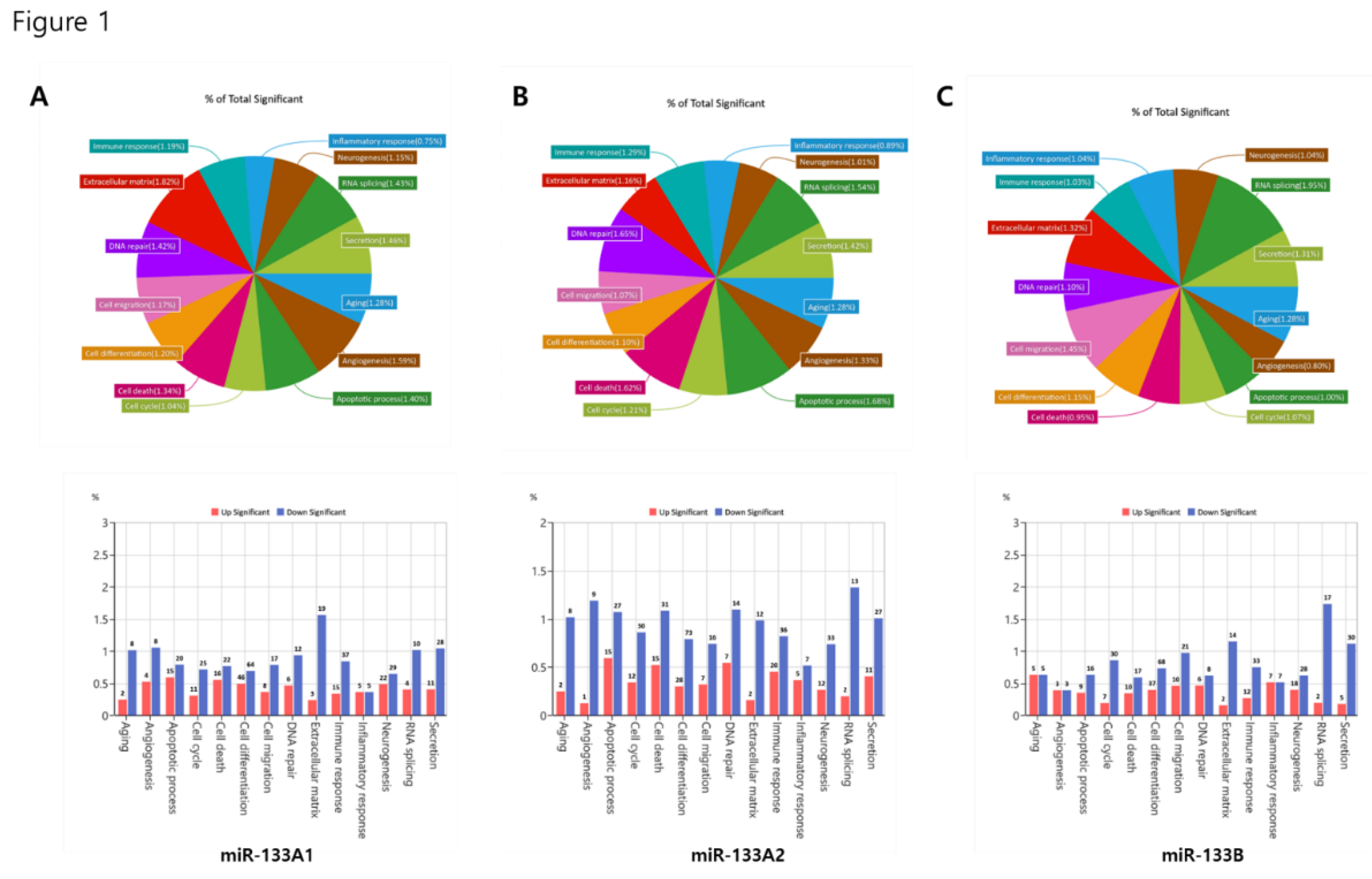

Our analysis demonstrates that miR-133 isoforms, while sharing a conserved regulatory signature, exert distinct transcriptional effects in colorectal cancer cells. The identification of 34 commonly upregulated and 195 downregulated genes across all isoforms (

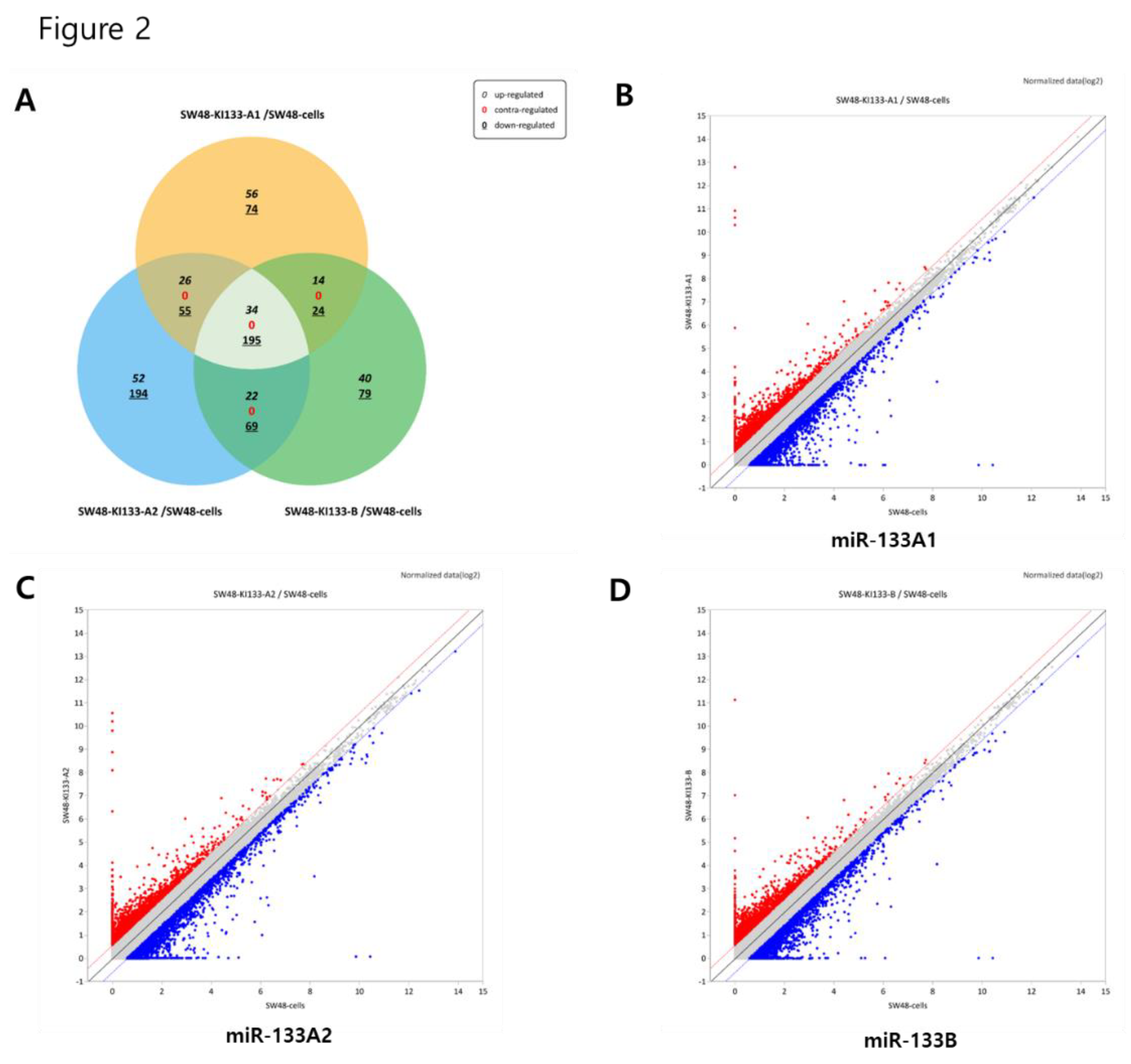

Figure 2A) suggests a fundamental role for MIR133A in modulating apoptosis and extracellular matrix remodeling, both central to tumor progression. Hierarchical clustering reinforced the close similarity of KI133A1 and KI133A2, whereas KI133B displayed a unique expression profile (

Figure 3).

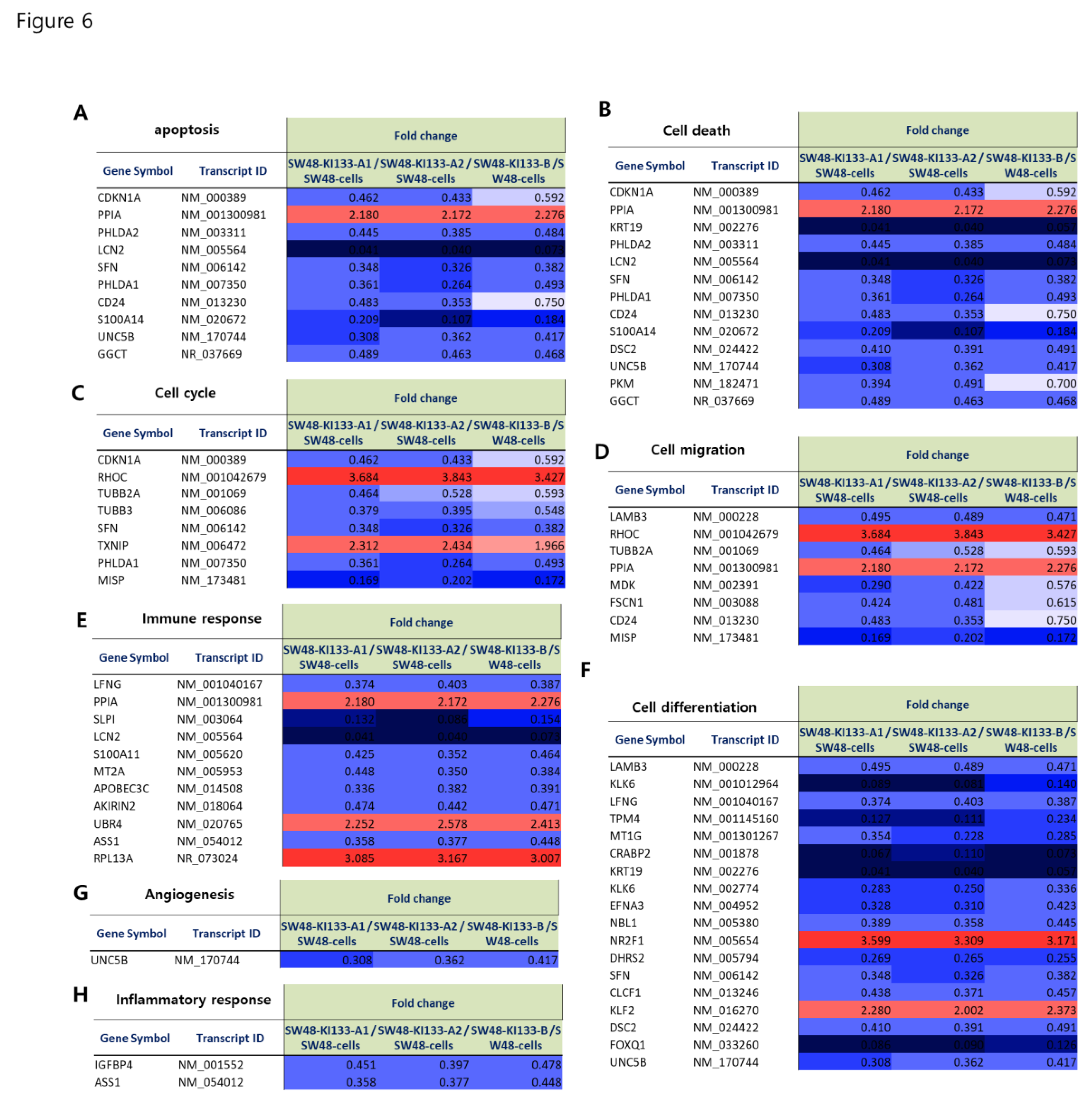

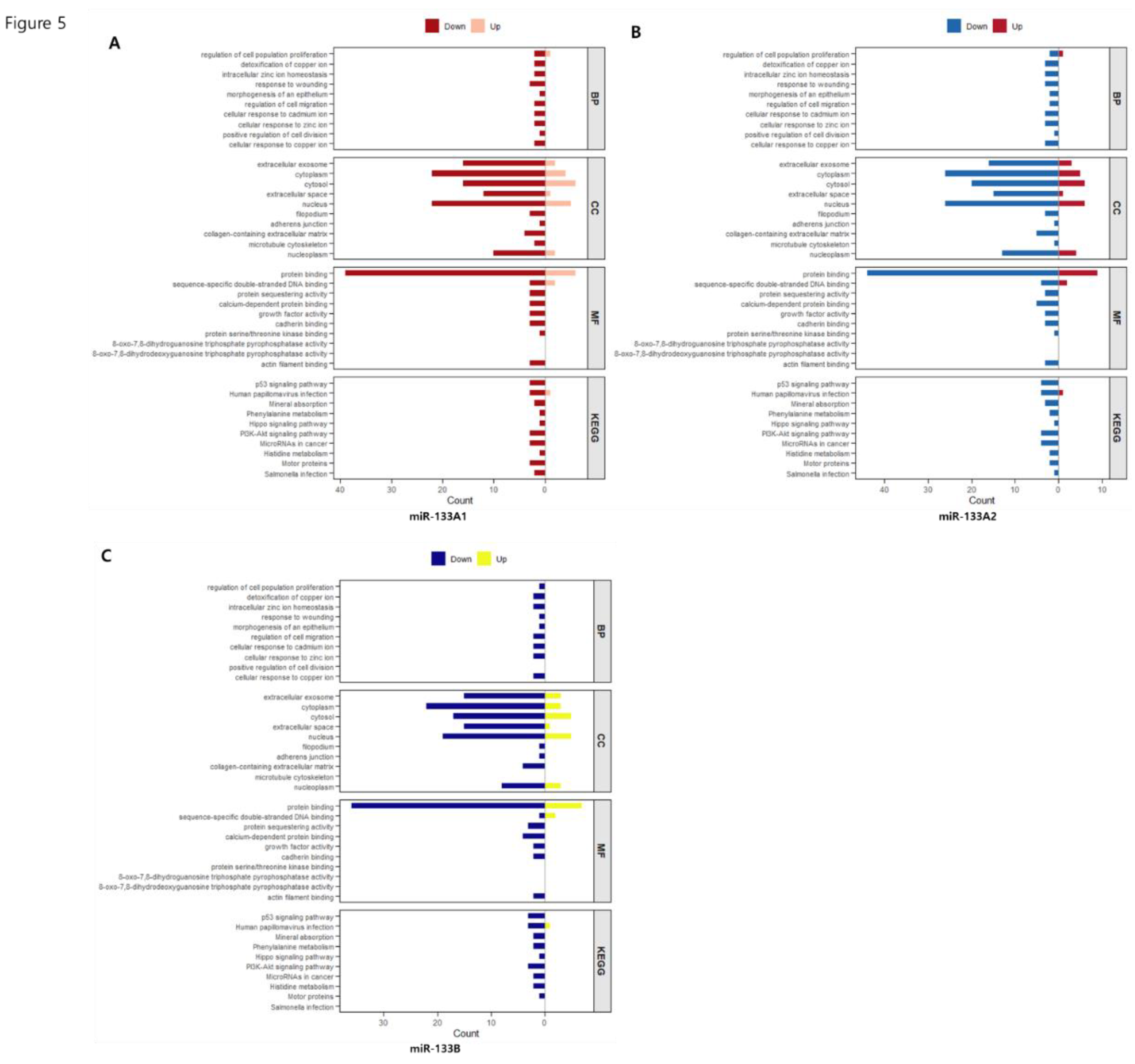

The enrichment of extracellular matrix and migration-related categories in KI133A1 and KI133A2 (

Figure 1A–B and

Figure 5A–B) indicates their potential role in regulating cell adhesion and invasive properties. Concurrent suppression of apoptotic pathways further suggests a shift toward survival and adaptation within the tumor microenvironment. In contrast, KI133B preferentially regulated signaling networks, including PI3K-Akt, Hippo, and p53 (

Figure 4C and

Figure 5C), and downregulated immune-related processes (

Figure 1C), implying a broader influence on oncogenic signaling and immune evasion.

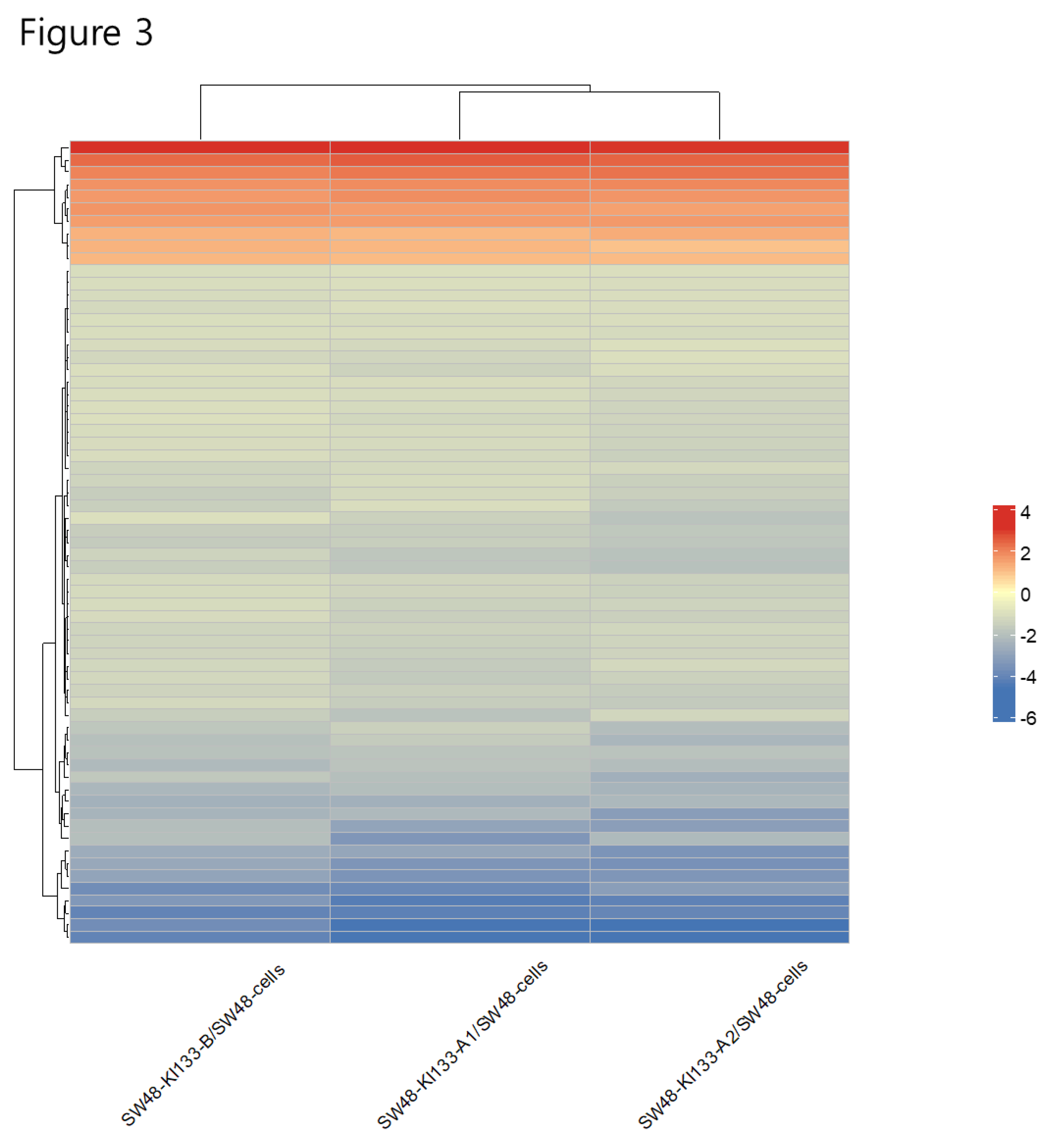

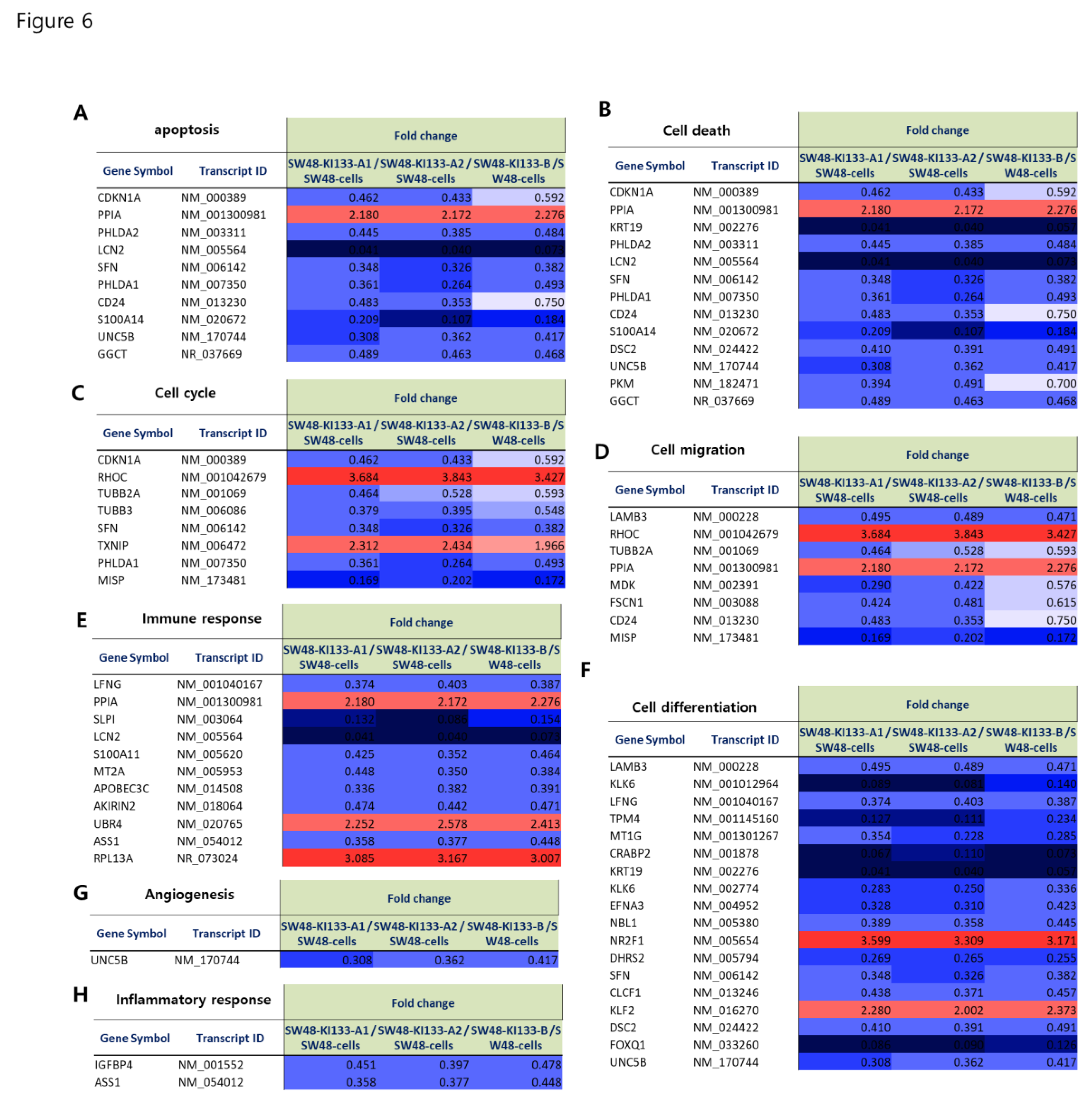

Our representative gene analysis (

Figure 6A–H) provides deeper insights into the functional heterogeneity of miR-133 isoforms in colorectal cancer. Consistent downregulation of BAX, CASP3, and FAS (

Figure 6A,B) demonstrates a shared suppression of apoptotic signaling, while upregulation of BCL2, CCND1, CDK4, and MYC (

Figure 6C,D) in KI133A2 and KI133B highlights their stronger promotion of survival and cell cycle progression. These findings align with the broader pathway enrichment analyses indicating proliferative and anti-apoptotic reprogramming (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Isoform-specific regulation of invasion-related genes such as MMP9, COL1A1, and ITGB1 (

Figure 6E,F) suggests that while KI133A1 and KI133A2 may limit invasive potential through ECM suppression, KI133B partially counteracts this by maintaining or even inducing ECM remodeling, potentially facilitating metastatic progression. Importantly, KI133B showed unique regulation of RNA processing and splicing factors (SRSF3, SF3B1) (

Figure 6G), pointing to isoform-specific control of RNA metabolism, which may underlie alternative splicing events associated with tumor adaptation. Stress response genes, including MT1 and HMOX1 (

Figure 6H), further demonstrated divergent patterns across isoforms, supporting the concept that miR-133 isoforms contribute to distinct modes of cellular adaptation under metabolic and oxidative challenges.

Beyond these processes, the expanded representative gene analysis revealed isoform-specific effects on DNA damage response (e.g., RAD51, ATM), angiogenesis (e.g., VEGFA, ANGPT2), and immune modulation (e.g., CXCL8, IL6), suggesting that miR-133 isoforms exert multifaceted regulatory roles in shaping tumor behavior. Collectively, these findings emphasize that apoptosis and cell cycle regulation represent the shared “core program” of miR-133 isoforms, whereas ECM remodeling, RNA metabolism, stress response, and signaling pathways represent isoform-specific regulatory layers.

The isoform-specific functions of miR-133 observed in this study carry potential clinical implications. Differential regulation of apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and RNA processing suggests that isoform expression profiles may serve as biomarkers to stratify colorectal cancer patients based on tumor aggressiveness or therapy response. For example, the enrichment of survival and angiogenesis pathways in KI133B may identify patient subgroups with more aggressive diseases, while suppression of apoptotic signaling by KI133A2 could contribute to resistance against conventional chemotherapeutics. Thus, isoform-level profiling of miR-133 may complement current molecular diagnostics and guide personalized treatment strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, the analyses were performed in a single colorectal cancer cell line (SW48), which may not fully capture the heterogeneity of CRC subtypes. Second, while transcriptomic profiling provided valuable insights into isoform-specific regulatory programs, functional validation in additional CRC models and patient-derived samples is required. Third, in vivo studies are needed to establish the impact of miR-133 isoforms on tumor progression and therapeutic response. Future work addressing these limitations will be essential to translate our findings into clinically relevant applications.

Figure 1.

Functional categorization of differentially expressed genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. Pie charts and bar plots depict enriched biological processes in stable cell lines expressing miR-133A1 (A), miR-133A2 (B), and miR-133B (C) compared with control. Each category represents a proportion of significantly regulated genes involved in processes such as cell cycle, apoptosis, migration, extracellular matrix organization, immune response, neurogenesis, and RNA splicing. Red bars indicate significantly upregulated pathways, while blue bars indicate downregulated pathways. The analysis highlights both shared and isoform-specific regulatory effects of miR-133 isoforms.

Figure 1.

Functional categorization of differentially expressed genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. Pie charts and bar plots depict enriched biological processes in stable cell lines expressing miR-133A1 (A), miR-133A2 (B), and miR-133B (C) compared with control. Each category represents a proportion of significantly regulated genes involved in processes such as cell cycle, apoptosis, migration, extracellular matrix organization, immune response, neurogenesis, and RNA splicing. Red bars indicate significantly upregulated pathways, while blue bars indicate downregulated pathways. The analysis highlights both shared and isoform-specific regulatory effects of miR-133 isoforms.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. (A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of differentially expressed genes among SW48-KI133A1, SW48-KI133A2, and SW48-KI133B cells compared with parental SW48 controls. Numbers indicate isoform-specific and shared upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes. (B–D) Scatter plots depicting log2-normalized expression changes in SW48-KI133A1 (B), SW48-KI133A2 (C), and SW48-KI133B (D) relative to SW48 control cells. Red dots represent significantly upregulated genes, while blue dots indicate significantly downregulated genes. The results highlight both common and isoform-specific transcriptional signatures regulated by miR-133 isoforms.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. (A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of differentially expressed genes among SW48-KI133A1, SW48-KI133A2, and SW48-KI133B cells compared with parental SW48 controls. Numbers indicate isoform-specific and shared upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes. (B–D) Scatter plots depicting log2-normalized expression changes in SW48-KI133A1 (B), SW48-KI133A2 (C), and SW48-KI133B (D) relative to SW48 control cells. Red dots represent significantly upregulated genes, while blue dots indicate significantly downregulated genes. The results highlight both common and isoform-specific transcriptional signatures regulated by miR-133 isoforms.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in miR-133 isoform-expressing SW48 cells. Hierarchical clustering analysis of SW48-KI133A1, SW48-KI133A2, and SW48-KI133B cells compared with parental SW48 controls. Rows represent individual genes, and columns represent biological replicates of each isoform. Red indicates upregulated genes, while blue indicates downregulated genes. The analysis reveals clustering similarity between KI133A1 and KI133A2, whereas KI133B exhibits a distinct transcriptional profile, indicating isoform-specific gene regulation.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in miR-133 isoform-expressing SW48 cells. Hierarchical clustering analysis of SW48-KI133A1, SW48-KI133A2, and SW48-KI133B cells compared with parental SW48 controls. Rows represent individual genes, and columns represent biological replicates of each isoform. Red indicates upregulated genes, while blue indicates downregulated genes. The analysis reveals clustering similarity between KI133A1 and KI133A2, whereas KI133B exhibits a distinct transcriptional profile, indicating isoform-specific gene regulation.

Figure 4.

Gene ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. (A) Bar plot of enriched GO terms across the three main categories: Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF), along with KEGG pathways. (B) Bubble plot visualization of the same enriched terms. The x-axis represents fold enrichment, while the bubble size indicates the number of genes associated with each term. The color scale reflects statistical significance (–log10 P-value). Enrichment results show that miR-133 isoforms regulate pathways related to proliferation, apoptosis, migration, extracellular matrix regulation, and major cancer-associated signaling cascades.

Figure 4.

Gene ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. (A) Bar plot of enriched GO terms across the three main categories: Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF), along with KEGG pathways. (B) Bubble plot visualization of the same enriched terms. The x-axis represents fold enrichment, while the bubble size indicates the number of genes associated with each term. The color scale reflects statistical significance (–log10 P-value). Enrichment results show that miR-133 isoforms regulate pathways related to proliferation, apoptosis, migration, extracellular matrix regulation, and major cancer-associated signaling cascades.

Figure 5.

Isoform-specific GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in miR-133 stable cell lines. Bar plots represent enriched GO categories (BP: Biological Process, CC: Cellular Component, MF: Molecular Function) and KEGG pathways for SW48-KI133A1 (A), SW48-KI133A2 (B), and SW48-KI133B (C) compared with parental SW48 controls. Red/yellow bars indicate upregulated gene categories, while blue bars indicate downregulated categories. The analysis demonstrates both overlapping and isoform-specific regulation of pathways related to proliferation, apoptosis, extracellular organization, and cancer-associated signaling.

Figure 5.

Isoform-specific GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in miR-133 stable cell lines. Bar plots represent enriched GO categories (BP: Biological Process, CC: Cellular Component, MF: Molecular Function) and KEGG pathways for SW48-KI133A1 (A), SW48-KI133A2 (B), and SW48-KI133B (C) compared with parental SW48 controls. Red/yellow bars indicate upregulated gene categories, while blue bars indicate downregulated categories. The analysis demonstrates both overlapping and isoform-specific regulation of pathways related to proliferation, apoptosis, extracellular organization, and cancer-associated signaling.

Figure 6.

Heatmap representation of fold change values for representative genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. Heatmaps show the relative expression (fold change) of selected genes in SW48-KI133A1, SW48-KI133A2, and SW48-KI133B compared with parental SW48 controls. (A–B) Downregulation of pro-apoptotic genes (BAX, CASP3, FAS) across all isoforms. (C–D) Upregulation of survival and proliferation-associated genes (BCL2, CCND1, CDK4, MYC), particularly in KI133A2 and KI133B. (E–F) Isoform-specific regulation of extracellular matrix and migration-related genes (MMP9, COL1A1, ITGB1), with differential effects among isoforms. (G) Altered expression of RNA splicing and processing factors (SRSF3, SF3B1), predominantly in KI133B. (H) Stress response-related genes (MT1, HMOX1) showing isoform-dependent modulation. Red indicates upregulation, and blue indicates downregulation. The results highlight both overlapping and isoform-specific transcriptional programs in apoptosis, proliferation, migration, RNA metabolism, and stress adaptation.

Figure 6.

Heatmap representation of fold change values for representative genes regulated by miR-133 isoforms. Heatmaps show the relative expression (fold change) of selected genes in SW48-KI133A1, SW48-KI133A2, and SW48-KI133B compared with parental SW48 controls. (A–B) Downregulation of pro-apoptotic genes (BAX, CASP3, FAS) across all isoforms. (C–D) Upregulation of survival and proliferation-associated genes (BCL2, CCND1, CDK4, MYC), particularly in KI133A2 and KI133B. (E–F) Isoform-specific regulation of extracellular matrix and migration-related genes (MMP9, COL1A1, ITGB1), with differential effects among isoforms. (G) Altered expression of RNA splicing and processing factors (SRSF3, SF3B1), predominantly in KI133B. (H) Stress response-related genes (MT1, HMOX1) showing isoform-dependent modulation. Red indicates upregulation, and blue indicates downregulation. The results highlight both overlapping and isoform-specific transcriptional programs in apoptosis, proliferation, migration, RNA metabolism, and stress adaptation.