Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Expression Profile Analysis

2.2. Upstream Analysis

2.3. Protein Network Construction

2.4. DE-LncRNAs

3. Results

3.1. Differential Expression Genes

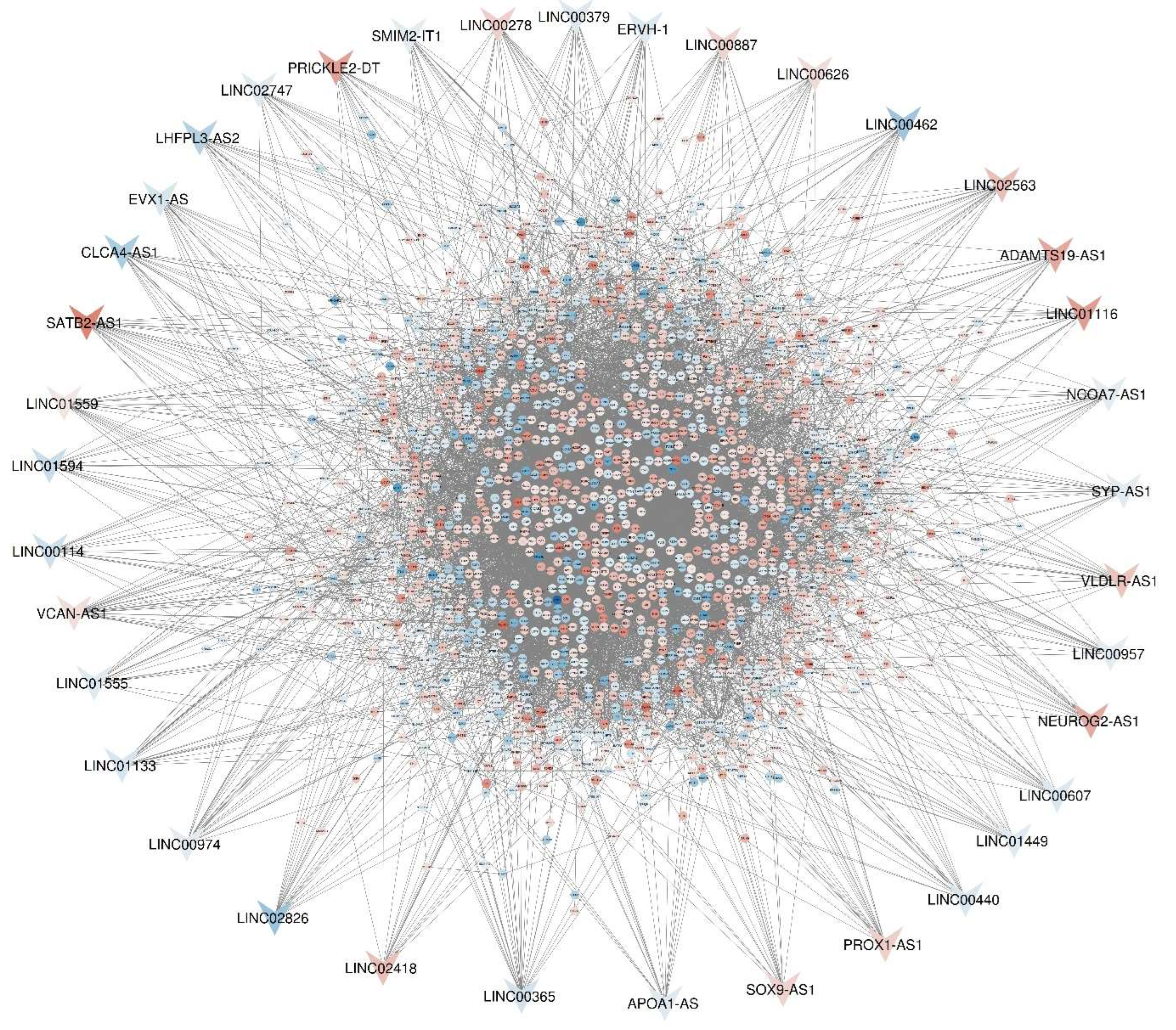

3.2. Construction of PPI Network

3.3. Upstream analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Sobrero, A.; Van Krieken, J.H.; Aderka, D.; Aranda Aguilar, E.; Bardelli, A.; Benson, A.; Bodoky, G.; et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016, 27, 1386–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, S.; Lepage, C.; Hatem, C.; Coatmeur, O.; Faivre, J.; Bouvier, A.M. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 2006, 244, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardis, E.R. Next-generation sequencing platforms. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2013, 6, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, D.J.; Dong, H.; Byrne, M.C.; Follettie, M.T.; Gallo, M.V.; Chee, M.S.; Mittmann, M.; Wang, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Horton, H.; et al. Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Biotechnol 1996, 14, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.X.; Koirala, P.; Mo, Y.Y. LncRNA-mediated regulation of cell signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 5661–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.M.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science 2002, 295, 1662–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozhabri, H.; Ghasemi Dehkohneh, R.S.; Razavi, S.M.; Razavi, S.M.; Salarian, F.; Rasouli, A.; Azami, J.; Ghasemi Shiran, M.; Kardan, Z.; Farrokhzad, N.; et al. Comparative analysis of protein-protein interaction networks in metastatic breast cancer. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0260584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, A.; Abazari, O.; Dayati, P.; Kardan, Z.; Salari, A.; Khalili, M.; Motlagh, F.M.; Modarressi, M.H. Identification of Potential Key Genes Linked to Gender Differences in Bladder Cancer Based on Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Database. Adv Biomed Res 2023, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, e47–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.; Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential analysis of count data–the DESeq2 package. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 10–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Deng, W.; Bao, H.; Lin, Z.; Liu, M.; Wu, J.; Zhou, X.; Qiao, M.; Yang, Y.; Cai, H.; et al. SOX4 facilitates PGR protein stability and FOXO1 expression conducive for human endometrial decidualization. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma'ayan, A. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mering, C.v.; Huynen, M.; Jaeggi, D.; Schmidt, S.; Bork, P.; Snel, B. STRING: a database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic acids research 2003, 31, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardoni, G.; Petterlini, M.; Laudanna, C. Analyzing biological network parameters with CentiScaPe. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2857–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qu, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, B.; Su, J.; Bian, X. LINC00365 functions as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting HIF-1α-mediated glucose metabolism reprogramming in breast cancer. Experimental Cell Research 2023, 425, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghehchian, N.; Farshchian, M.; Mahmoudian, R.A.; Asoodeh, A.; Abbaszadegan, M.R. The expression of long non-coding RNA LINC01389, LINC00365, RP11-138J23. 1, and RP11-354K4. 2 in gastric cancer and their impacts on EMT. Molecular and Cellular Probes 2022, 66, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Bian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Li, L.; Yang, M.; Qian, H.; Yu, L.; Liu, B.; Qian, X. LINC00365 promotes colorectal cancer cell progression through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2020, 121, 1260–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Du, X.; Chen, M.; Han, L.; Sun, J. Novel insight into the functions of N 6-methyladenosine modified lncRNAs in cancers. International journal of oncology 2022, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Man, C.-F.; He, R.; He, L.; Huang, J.-B.; Xiang, S.-Y.; Dai, Z.; Wang, X.-Y.; Fan, Y. The interaction between N6-methyladenosine modification and non-coding RNAs in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 11, 784127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Yang, S.; Chen, C.; Shao, B.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, W. RNA methylation-mediated LINC01559 suppresses colorectal cancer progression by regulating the miR-106b-5p/PTEN axis. International journal of biological sciences 2022, 18, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Qian, X.; Xu, X.; Lv, P. Long non-coding RNA LINC01559 serves as a competing endogenous RNA accelerating triple-negative breast cancer progression. biomedical journal 2022, 45, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, F.; Xia, D. Propofol-induced LINC01133 inhibits the progression of colorectal cancer via miR-186-5p/NR3C2 axis. Environmental Toxicology 2024, 39, 2265–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, L.; Wu, S.; Ye, B.; Chen, C.; Shi, L. Construction of a metabolism-related long non-coding RNAs-based risk score model of hepatocellular carcinoma for prognosis and personalized treatment prediction. Pathology and Oncology Research 2022, 28, 1610066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; He, B. Predictive value of cuproptosis and disulfidptosis-related lncRNA in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma prognosis and treatment. Heliyon 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, R.; Sun, L.; Hu, X. An lncRNA model for predicting the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients and ceRNA mechanism. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8, 749313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqadami, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Khalaj-Kondori, M. lncRNA VLDLR-AS1 Gene Expression in Colorectal Cancer in Patients from East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Jentashapir J Cell Mol Biol 2023, 14, e141522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhan, W.; Chen, G.; Yan, S.; Chen, W.; Li, R. SP1-induced PROX1-AS1 contributes to tumor progression by regulating miR-326/FBXL20 axis in colorectal cancer. Cellular Signalling 2023, 101, 110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, M.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Liu, N.; Yao, J.; Dong, F.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; et al. LINC00887 promotes GCN5-dependent H3K27cr level and CRC metastasis via recruitment of YEATS2 and enhancing ETS1 expression. Cell Death & Disease 2024, 15, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Shang, X. Comprehensive analyses of correlation and survival reveal informative lncRNA prognostic signatures in colon cancer. World journal of surgical oncology 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Cui, P.; Li, Y.; Yao, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. LINC02418 promotes colon cancer progression by suppressing apoptosis via interaction with miR-34b-5p/BCL2 axis. Cancer Cell International 2020, 20, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.H.; Li, L.H.; Zhang, P.F.; Cai, Y.F.; Hua, D. LINC00957 Acted as Prognostic Marker Was Associated With Fluorouracil Resistance in Human Colorectal Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashkhashi Moghadam, S.; Bakhshinejad, B.; Khalafizadeh, A.; Mahmud Hussen, B.; Babashah, S. Non-coding RNA-associated competitive endogenous RNA regulatory networks: Novel diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med 2022, 26, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Song, A.; Gui, P.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Xu, Y.; et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC01594 inhibits the CELF6-mediated splicing of oncogenic CD44 variants to promote colorectal cancer metastasis. Cell Death & Disease 2023, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wang, W.; Liao, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. MYC-activated LINC00607 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating the miR-584-3p/ROCK1 axis. The Journal of Gene Medicine 2023, 25, e3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Qin, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, S. LINC00114 stimulates growth and glycolysis of esophageal cancer cells by recruiting EZH2 to enhance H3K27me3 of DLC1. Clinical epigenetics 2022, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Peng, K.; Wu, W. A Prognostic Model Based on Nine DNA Methylation-Driven Genes Predicts Overall Survival for Colorectal Cancer. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, M.; Karim, S.; Haque, A.; Alharthi, M.; Chaudhary, A.G.; Natesan Pushparaj, P. Deciphering gene expression signatures in liver metastasized colorectal cancer in stage IV colorectal cancer patients. Journal of King Saud University - Science 2024, 36, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xu, X.; Pan, B.; Chen, X.; Lin, K.; Zeng, K.; Liu, X.; Xu, T.; Sun, L.; Qin, J. LncRNA SATB2-AS1 inhibits tumor metastasis and affects the tumor immune cell microenvironment in colorectal cancer by regulating SATB2. Molecular cancer 2019, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-Q.; Jiang, D.-M.; Hu, S.-S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.-H.; Ai, M.-L.; Jiang, H.-J.; Han, Y.; Ding, Y.-Q. SATB2-AS1 suppresses colorectal carcinoma aggressiveness by inhibiting SATB2-dependent Snail transcription and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cancer research 2019, 79, 3542–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.; Lu, W.; Jiang, X. LncRNA SATB2-AS1 overexpression represses the development of hepatocellular carcinoma through regulating the miR-3678-3p/GRIM-19 axis. Cancer Cell International 2023, 23, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, Z.; He, Y.; Guo, W. Promising advances in LINC01116 related to cancer. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 736927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, A.; Omear, H.A.; Mansoori, Y.; Mansouri, P.; Deng, X.; Darbeheshti, F.; Zarenezhad, E.; Kohansal, M.; Pezeshki, B.; Wang, Z.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs and JAK/STAT signaling pathway regulation in colorectal cancer development. Frontiers in Genetics 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-K.; Zhang, X.-D.; Luo, K.; Yu, L.; Huang, S.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Li, R.-F. Comprehensive analysis of candidate signatures of long non-coding RNA LINC01116 and related protein-coding genes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterology 2023, 23, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | padj | Pvalue | Betweenness |

| FN1 | 3.95E-27 | 1.13E-29 | 133042.2 |

| JUN | 1.59E-06 | 3.56E-08 | 101029.8 |

| SOX2 | 0.015148 | 0.001137 | 100116.9 |

| EGF | 3.00E-04 | 1.12E-05 | 78299.49 |

| AGT | 1.71E-10 | 1.97E-12 | 76350.64 |

| BCL2 | 0.252012 | 0.04707 | 73450.41 |

| CAV1 | 0.005062 | 2.95E-04 | 69762.45 |

| DLG4 | 0.001252 | 5.64E-05 | 55110.58 |

| CFTR | 4.89E-30 | 1.12E-32 | 48873.94 |

| CD74 | 1.86E-05 | 5.13E-07 | 48418.26 |

| First Dataset | Second Dataset | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | LogFC | P.Value | Padj | Targets | Symbol | LogFC | P.Value | Padj | Targets |

| LINC00365 | -1.96228 | 0.01873 | 0.13292 | 26 | VCAN-AS1 | 1.6172 | 0.00036 | 0.00448 | 29 |

| SATB2-AS1 | 1.3E-52 | 7.22302 | 6.2E-56 | 25 | SATB2-AS1 | -1.4441 | 0.04048 | 0.12922 | 25 |

| LINC00278 | 2.477 | 0.0095 | 0.07997 | 22 | LINC00974 | -1.1489 | 0.00107 | 0.00973 | 24 |

| LINC02826 | -4.91475 | 0.00683 | 0.06268 | 21 | SYP-AS1 | -1.1536 | 7.57E-05 | 0.00148 | 19 |

| LINC01559 | 1.14904 | 5.6E-11 | 3.9E-09 | 21 | LINC00440 | -1.4691 | 0.0008 | 0.00789 | 19 |

| CLCA4-AS1 | -3.87085 | 0.02089 | 0.14368 | 21 | SMIM2-IT1 | -1.03 | 0.00295 | 0.02051 | 18 |

| LINC01133 | -1.71347 | 1.9E-18 | 3.2E-16 | 21 | LINC01555 | -1.3152 | 0.007 | 0.03816 | 18 |

| LINC02563 | 3.48567 | 0.00133 | 0.01714 | 20 | LINC01449 | -1.2126 | 2.05E-07 | 6.73E-05 | 18 |

| LINC00462 | -4.69382 | 0.01943 | 0.13672 | 20 | LINC00114 | -2.1923 | 0.00927 | 0.04644 | 18 |

| VLDLR-AS1 | 3.19298 | 0.01845 | 0.13161 | 19 | NCOA7-AS1 | -1.0249 | 0.0004 | 0.00479 | 17 |

| PRICKLE2-DT | 5.4572 | 0.00024 | 0.00433 | 19 | ERVH-1 | -1.3516 | 0.00025 | 0.00347 | 17 |

| PROX1-AS1 | 2.56183 | 3.6E-09 | 1.9E-07 | 19 | APOA1-AS | -1.248 | 7.72E-07 | 0.00011 | 17 |

| ADAMTS19-AS1 | 4.95854 | 4.1E-06 | 0.00012 | 18 | LINC01116 | 1.9556 | 0.00066 | 0.00683 | 16 |

| LINC00887 | 2.25373 | 0.0002 | 0.00369 | 18 | LINC00626 | 1.7331 | 0.0161 | 0.06867 | 16 |

| EVX1-AS | -1.64684 | 0.00097 | 0.01333 | 18 | LINC00607 | -1.411 | 0.00133 | 0.01147 | 16 |

| NEUROG2-AS1 | 4.80579 | 1.6E-06 | 5.2E-05 | 17 | LINC00379 | -1.3688 | 0.01837 | 0.07516 | 16 |

| LHFPL3-AS2 | -3.44886 | 0.01825 | 0.13062 | 17 | |||||

| LINC02418 | 3.48651 | 0.00144 | 0.01826 | 17 | |||||

| LINC00957 | -1.05286 | 0.01165 | 0.09339 | 17 | |||||

| SOX9-AS1 | 2.3242 | 3.7E-24 | 8.9E-22 | 16 | |||||

| LINC02747 | -1.30917 | 0.00271 | 0.03019 | 16 | |||||

| LINC01594 | -2.46856 | 0.01107 | 0.09008 | 16 | |||||

| LINC01116 | 6.3E-07 | 5.67987 | 1.3E-08 | 16 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).