1. Introduction

Plant-derived compounds have long been recognized as a rich source of bioactive molecules with diverse pharmacological properties. Among these, certain herbs have demonstrated potent effects on nematodes, making them promising candidates for developing environmentally friendly nematocides.

Ruscus hyrcanus,

Juniperus oblonga, and

Stachys lavandulifolia are three such herbs with a history of traditional medicinal use across Europe, the Middle East, and western Asia.

R. hyrcanus is an evergreen shrub endemic to Iran and Azerbaijan, traditionally valued for its diuretic, vasoconstrictive, and antimicrobial properties [

1,

2,

3,

4].

J. oblonga is a dioecious evergreen tree found in Iran, Turkey, and the Caucasus, with folk applications ranging from diuretic and antiscorbutic to antitumor and neuroprotective activities [

5,

6].

S. lavandulifolia, a herbaceous plant widely used in Turkish and Iranian medicine [

7,

8], exhibits analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Despite this rich ethnopharmacological knowledge, the mechanistic understanding of these herbs’ effects on nematodes and reproductive biology remains limited. Importantly, our previous studies have demonstrated a close interplay between DNA damage response and repair pathways and nematocidal effects in Caenorhabditis elegans, suggesting that modulation of genome integrity could be a key factor in herb-induced toxicity. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated cytotoxicity has been proposed as a common mechanism underlying nematode lethality, while perturbation of DNA damage response pathways may further contribute to germline defects. Motivated by this link, we sought to examine the molecular and cellular bases of nematocidal and reproductive effects of these medicinal plants.

In this study, we investigated the effects of R. hyrcanus, J. oblonga, and S. lavandulifolia extracts on C. elegans survival, fertility, and germline DNA damage responses. Using a combination of survival assays, germline cytology, and LC–MS profiling, we aimed to dissect both the shared ROS-mediated mechanisms and herb-specific contributions to DNA damage and apoptosis. Interestingly, while modulation of DNA damage responses was observed, our findings indicate that ROS generation plays a particularly prominent role in driving the nematocidal and fertility-reducing effects of these herbs. Collectively, this work provides a comprehensive assessment of how traditional medicinal plants and their phytochemicals can modulate oxidative stress and genome stability in vivo. By linking phytochemical composition with ROS-mediated bioactivity and reproductive outcomes, our findings emphasize not only the biological activity but also the safety-relevant cytotoxic potential of these herbs, contributing to a more balanced understanding of their nutritional and therapeutic implications.

2. Results

2.1. Nematocidal Effects

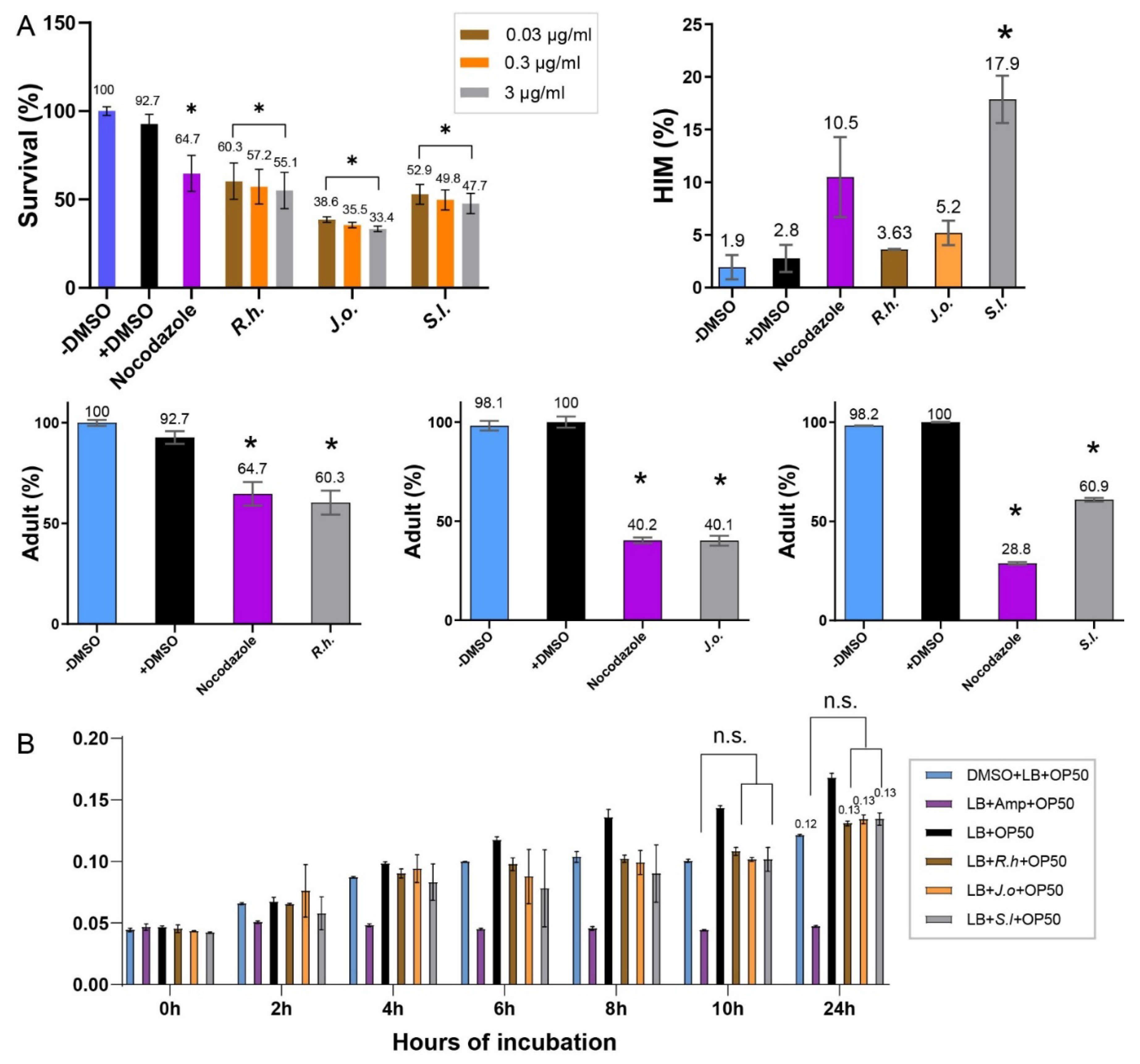

Extracts from all three herbs—Ruscus hyrcanus (R.h), Juniperus oblonga (J.o), and Stachys lavandulifolia (S.l)—significantly reduced the survival rates of C. elegans compared with the untreated control group. The extent of reduction was comparable to that observed in the DMSO control (

Figure 1A, 92.7 vs. 60.3 for +DMSO and R.h; 92.7 vs. 38.5 for +DMSO and J.o; 92.7 vs. 52.9 for +DMSO and S.l at 0.03 µg/ml). This suggests that all three extracts contain phytochemical compounds detrimental to the health and viability of C. elegans. In addition, exposure to the extracts led to larval arrest and lethality (92.7 vs. 60.3 adult (%) for +DMSO and R.h; 100 vs. 40.1 for +DMSO and J.o; 100 vs. 60.9 for +DMSO and S.l at 0.03 µg/ml). Together, these findings indicate that the three herbs exert potent nematocidal activity, likely linked to growth defects induced by bioactive compounds within the extracts.

In

C. elegans, errors in sex chromosome segregation during meiosis often result in an increased occurrence of males, a condition referred to as the High Incidence of Males (HIM) phenotype. The HIM phenotype is a well-established marker for studying the effects of environmental or chemical factors on reproductive health and genetic stability [

13]. Exposure to the three herbal extracts elevated the HIM phenotype, with the strongest effect observed in

S.l, suggesting that this extract may interfere with proper sex chromosome segregation (

Figure 1A, 2.8 vs. 3.63 for +DMSO and

R.h; 2.8 vs. 5.2 for +DMSO and

J.o; 2.8 vs. 17.9 for +DMSO and

S.l at 0.03 µg/ml).

The increased HIM phenotype, particularly prominent with

S.l extract, implies that these herbs may induce underlying genetic instability in

C. elegans. Disruption of normal meiotic processes leading to chromosome mis-segregation is a hallmark of genomic instability and is associated with various diseases, including cancer [

14,

15,

16]. These results highlight the potential of the three herbs as sources of nematocidal compounds with possible implications for genomic stability.

2.2. Dose-Dependent Nematocidal and Larval Arrest Effects of the Extracts

To further validate the nematocidal effects, we investigated whether different concentrations of the extracts correlated with changes in C. elegans phenotypes. Increasing concentrations of the herbal extracts consistently led to reduced survivability, demonstrating a clear dose-dependent relationship (

Figure 1A). For example, in R.h-treated worms, survival decreased from 60.3% to 57.2% and 55.1% at concentrations of 0.03, 0.3, and 3 µg/ml, respectively. Similarly, survival rates for J.o declined from 38.5% to 35.5% and 33.4%, while those for S.l decreased from 52.9% to 49.8% and 47.7% across the same concentration range. These findings confirm a strong correlation between extract concentration and worm mortality, supporting the hypothesis that higher doses of these herbal extracts significantly compromise nematode viability.

Taken together, extracts from the three medicinal plants—Ruscus hyrcanus, Juniperus oblonga, and Stachys lavandulifolia—exhibited strong nematocidal activity in C. elegans, leading to reduced survival rates and larval developmental arrest, with a clear dose-dependent decline in viability observed at increasing concentrations. In addition, exposure to these extracts elevated the High Incidence of Males (HIM) phenotype, most prominently with S. lavandulifolia, indicating potential interference with proper sex chromosome segregation during meiosis. Collectively, these findings suggest that the three herbal extracts are promising sources of nematocidal compounds that may also induce genetic instability in C. elegans.

2.3. Three herb Extracts do Not Alter Bacterial Growth

Because the decreased survival of

C. elegans following exposure to the three herbal extracts could potentially arise from indirect effects on their bacterial food source, we tested whether the extracts inhibited the growth of

E. coli OP50. Cultures of OP50 were incubated with each extract for 24 hours, and bacterial proliferation was monitored by optical density at 600 nm. No significant differences were observed between the extract-treated groups and the DMSO control at either 12 or 24 hours, indicating that the extracts did not interfere with bacterial growth under the tested conditions. At the 24-hour time point, OD values remained nearly identical across groups (

Figure 1B, 0.12 for OP50 + DMSO vs. 0.13 for OP50 +

R.h,

J.o, or

S.l; P = 0.076, 0.1000, 0.1000, respectively). These results demonstrate that the reduced worm survival and larval arrest observed with the herbal extracts are not attributable to altered bacterial food availability, but rather reflect direct effects on nematode physiology.

Taken together with the dose-dependent decline in worm viability described above, these findings strongly support the conclusion that the three herbs exert potent nematocidal activity by targeting essential biological processes in C. elegans. This highlights their potential as promising candidates for further investigation into natural nematocidal compounds, independent of any impact on bacterial growth.

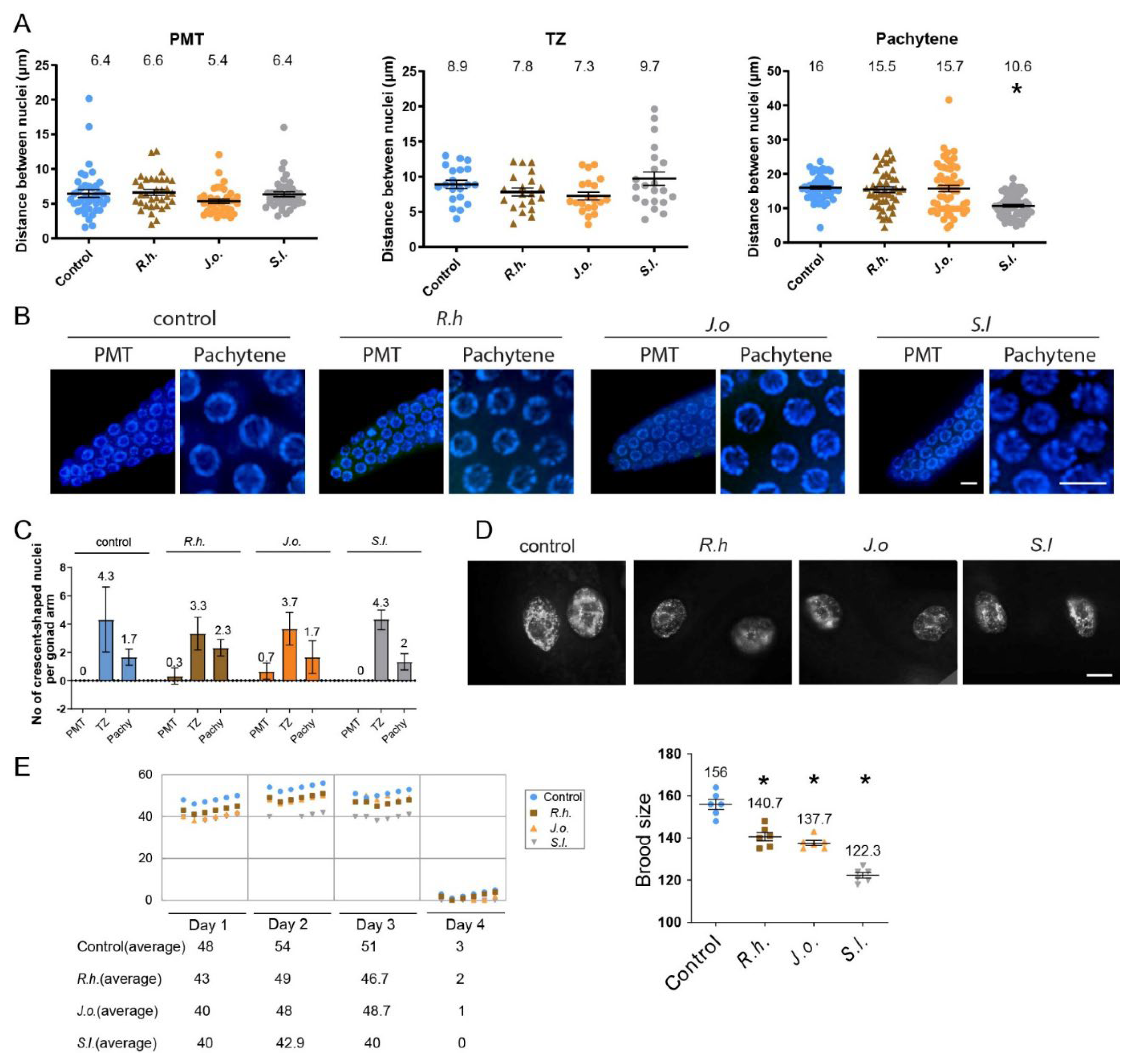

2.4. Impact of Herbal Extracts on Spatial Arrangement of Germline Nuclei

In

C. elegans, the development of the germline is a tightly regulated process where nuclei follow a specific spatial and temporal arrangement as they progress through various stages of meiosis and mitosis. During normal germline progression, mitotic nuclei are located at the distal tip of the premeiotic zone (PMT) and gradually transition to meiotic prophase as they move towards the transition zone (TZ), where nuclei begin to adopt a crescent shape. This shift marks the commencement of the meiotic process [

17]. Given that exposure to

S.l. extracts resulted in defective meiotic progression in our initial observations, we aimed to further investigate how these herbal extracts affect the overall organization of the germline in

C. elegans.

To explore this, we dissected adult hermaphrodites and examined the arrangement of nuclei in the germline. For this, we quantify the

distances between adjacent nuclei. While all three herb extracts treatment did not alter the distance in PMT or TZ significantly.

S.l exposed worms showed significant distance between nuclei at pachytene (

Figure 2A,B, P=0.3594, P=0.0925, P=0.7434 in PMT of

R.h,

J.o and S.I compare to control, respectively; P=0.1636, P=0.0742, P=0.7434 in TZ of

R.h,

J.o and S.I compare to control, respectively; P=0.3581, P=0.4397, P<0.0001 in Pachytene of

R.h,

J.o and S.I compare to control, respectively). Specifically, in the pachytene stage, the gap between nuclei decreased from 16 µm in the control group to 10.6 µm in the

S.l treated group (P<0.0001), suggesting mild but significant defective meiotic progression together with robust HIM phenotype.

2.5. Herbal Extracts Preserve Germline Nuclear Morphology and Mitotic Integrity

Another typical feature of

C. elegans germline is the appearance of crescent-shaped nuclei marks the transition from mitosis to meiosis [

18,

19]. However often crescent-shaped nuclei represented in PMT or pachytene indicating abnormal development of germline nuclei. Three herb extracts did not alter the frequency of crescent-shaped nuclei in both the PMT, TZ and pachytene stages. In the PMT stage, all three herb and control group exhibit 0-0.7crescent shape nuclei per gonad arm (

Figure 2C, P>0.999, P=0.3458, P=0.7469 compared to control in Rh,

J.o,

S.l respectively, with Mann-Whitney test.). Similarly no significant changes were visible at TZ and Pachytene (in TZ, P>0.990, P>0.999, P=0.7671 compared to control in Rh,

J.o,

S.l respectively; in pachytene, P=0.3017, P>0.099, P=0.6103 compared to control in Rh,

J.o,

S.l respectively with Mann-Whitney test.).

Formation of chromatin bridges between gut cells, a hallmark of defective chromosomal segregation during anaphase or cytokinesis often found in exogenous DNA damage, [

15,

18], however no such chromatin bridges were observed in in any of three herb treated worms (n>15 for each herb). This indicates that the disruption caused by these three her extracts may not primarily manifest as mitotic defects in gut cells or other mitotic tissues (

Figure 2D).

2.6. Three Herb Extracts Significantly Reduce Brood Size in C. elegans

Given the reduction in survival observed in

C. elegans exposed to three herb extracts, we investigated that these defects in germline progression might also lead to a decrease in fertility. For this, we quantified the brood size of hermaphrodites exposed to

three herb extracts over a period of four days starting from the L4 stage. Compared with control worms,

three herb extract treated worms exhibited a significant drop in fertility starting on day 1 and continued until day3 or 4. Brood sizes decreasing from 156 in control to 140, 137, 122 in

R.h,

J.o and S.I, respectively (

Figure 2E, P=0.0063, 0.0049, 0.0049 restively, with Man-Whitney test). This reduction in fertility further supports the idea that these herb extracts interfere with meiotic development, resulting in compromised reproductive success.

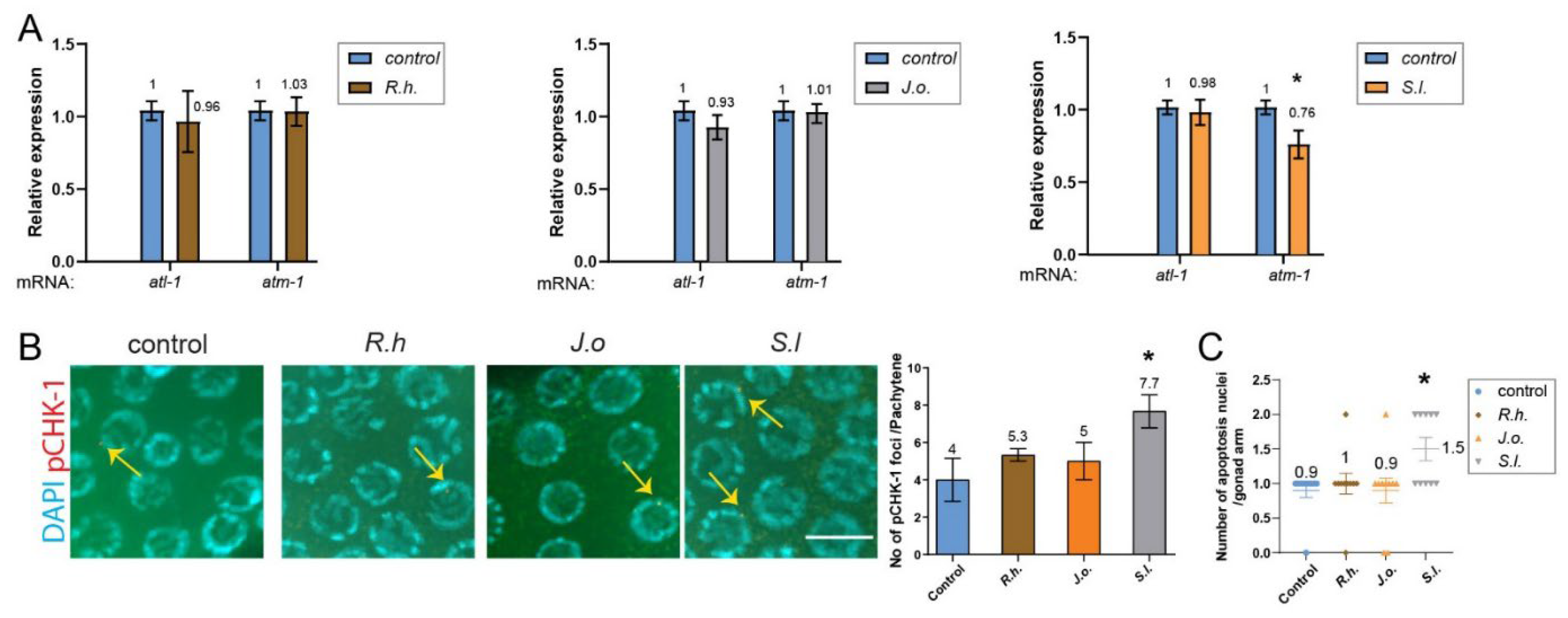

2.7. S.l Extract, but Not R.h or J.o, Modulates the DNA Damage Checkpoint Pathway Through pCHK-1

The DNA damage response constitutes a critical signaling cascade that initiates processes such as DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest [

20,

21,

22]. Both ATM and ATR can activate CHK1 directly or via intermediary kinases, with CHK1 activation driving downstream responses that facilitate DNA repair, arrest cell cycle progression, and preserve genome integrity in response to DNA damage or replication stress.

We examined the expression levels of

atm-1 (mammalian ATM),

atl-1 (mammalian ATR), and pCHK-1 (homologous to mammalian phospho-CHK1). Treatment with

R.h and

J.o herb extracts did not alter the expression of these two key DNA damage checkpoint components, suggesting that these treatments do not activate the DNA damage response. In contrast,

S.l extract mildly but significantly reduced

atm-1 expression (

Figure 3A, 1.0 vs. 0.76 in control and

S.l, P=0.012), whereas

atl-1 expression remained unchanged (1.0 vs. 0.98, P=0.3947). This finding suggests that

S.l extract may selectively attenuate ATM-mediated DNA damage signaling without broadly impairing ATR-dependent pathways, thereby indicating a potential herb-specific modulation of genome surveillance mechanisms rather than a general suppression of the DNA damage response.

Consistently, the downstream target of ATM and ATR, pCHK-1, did not show increased levels in the pachytene stage of germlines upon

R.h or

J.o treatment (

Figure 3B, P=0.5002, P=0.6429 for control vs.

R.h and

J.o, respectively; Mann–Whitney test). However,

S.l treatment significantly induced pCHK-1 foci levels (P=0.0326 for control vs.

S.l).

In

C. elegans hermaphrodites, germ cells undergo apoptosis in response to environmental stresses such as DNA damage. Germ cell apoptosis induced by DNA damage requires the DNA damage checkpoint,

cep-1 and

egl-1, but not the pathway for physiological apoptosis [

23,

24,

25]. We therefore analyzed DNA damage–induced apoptosis in the germline. Compared to the untreated control group, treatment with

R.h, or

J.o did not alter apoptosis levels during the pachytene stage (

Figure 3C, 0.9 vs. 1.0 in control and

R.h, P=0.6254; 0.9 vs. 0.9 in control and

J.o, P=0.9990). However, consistent with the pCHK-1 and

atm-1 expression results,

S.l exposure significantly increased apoptosis levels (0.9 vs. 1.5 in control and

S.l, P=0.0109).

Together, our apoptosis data indicate that exposure to S.l extract modestly but significantly altered the DNA damage checkpoint pathway and subsequent apoptosis, whereas R.h and J.o extracts did not affect these pathways.

2.8. LC-MS Profiling of Three Herbal Extracts Reveals 113 Bioactive Compounds, Including 14 with Nematocidal Potential

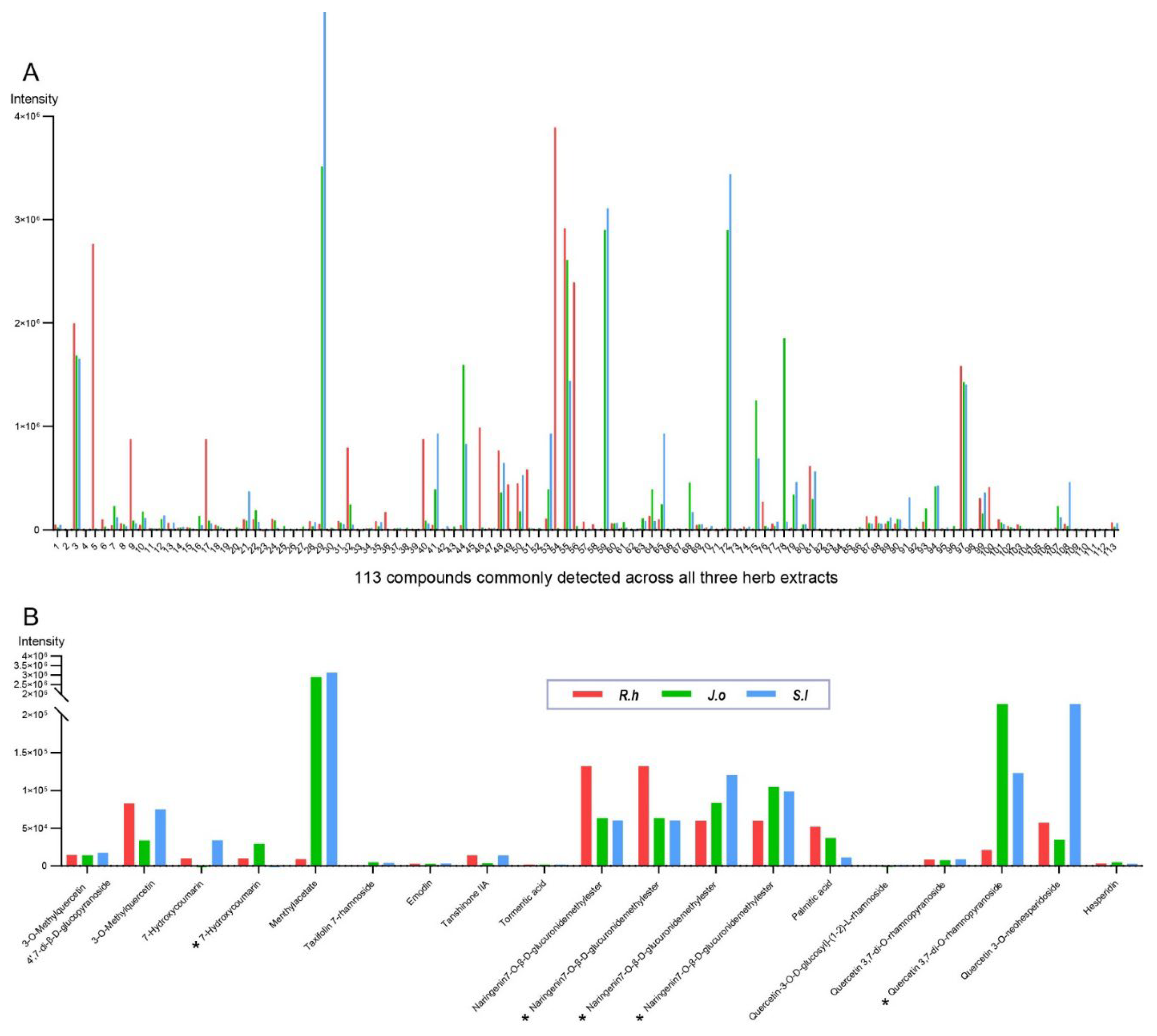

To gain insights into the specific compounds contributing to the nematocidal cytotoxicity, we conducted LC–MS analysis to identify the active constituents of three herb extracts. Surprisingly, all three extracts contained identical sets of compounds (113 in total), although their abundances differed among the herbs (

Figure 4A and

Supplementary Table S1).

2.8.1. Four Major Categories

The three herbal extracts are rich in diverse bioactive metabolites grouped into four major categories (

Table 1).

Phenolic compounds, including flavonoids, coumarins, lignans, and anthraquinones, provide antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anticancer activities by modulating key signaling pathways involved in proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis.

Glycosides and other carbohydrate derivatives, such as iridoids, contribute additional antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects.

Isoprenoids, including terpenes and terpenoids, offer notable anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities, enhancing the therapeutic potential of the extracts. Finally,

lipid derivatives, such as fatty acids and carboxylic acid esters, play roles in energy storage, inflammation regulation, and overall protective functions.

2.8.2. Nematocidal Effects

We further categorized the compounds based on their nematocidal potential. Across all three herbs, 14 compounds exhibited nematocidal or related bioactivities (

Figure 4B and

Table 2). Among the terpenoids, menthyl acetate displayed contact toxicity and repellency against Lasioderma serricorne adults [

26]. Tanshinone II induced cardiotoxicity and developmental malformations in zebrafish embryos [

27], while emodin exhibited insecticidal activity against Nilarparvata lugens and Mythimna separata [

28]. Tormentic acid caused apoptosis and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells, mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial dysfunction [

29].

Flavonoid derivatives also demonstrated nematocidal or parasiticidal effects through multiple mechanisms. Naringenin enhanced lifespan and reduced ROS accumulation in

C. elegans [

30], although it produced sublethal developmental effects in amphibian embryos [

31]. Hesperidin showed schistosomicidal activity in vitro, achieving complete mortality of Schistosoma mansoni adults [

32]. Apigenin inhibited larval growth in

C. elegans through activation of the DAF-16 pathway [

33], and quercetin derivatives caused neuromuscular paralysis via ROS-mediated effects, ultimately leading to paralysis and death of worms [

34]. Other compounds, such as 7-Hydroxycoumarin (7-HC) showed cytostatic and apoptotic effects in several human cancer cell lines [

35], and palmitic acid induced oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis in Chang liver cells [

36].

In contrast to the nematocidal compounds, a few flavonoid derivatives primarily exhibited protective or stress-tolerance effects rather than direct toxicity. Icariin and its metabolic derivative icariside II, extended lifespan in

C. elegans [

37]. Treatment with icariside II enhanced thermotolerance and oxidative stress resistance, slowed locomotion decline in late adulthood, and delayed the onset of paralysis caused by polyQ and Aβ1–42 proteotoxicity in an insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS) pathway–dependent manner. Similarly, luteolin derivatives did not alter the lifespan of wild-type N2 worms under normal conditions but conferred protective effects under oxidative stress [

38].

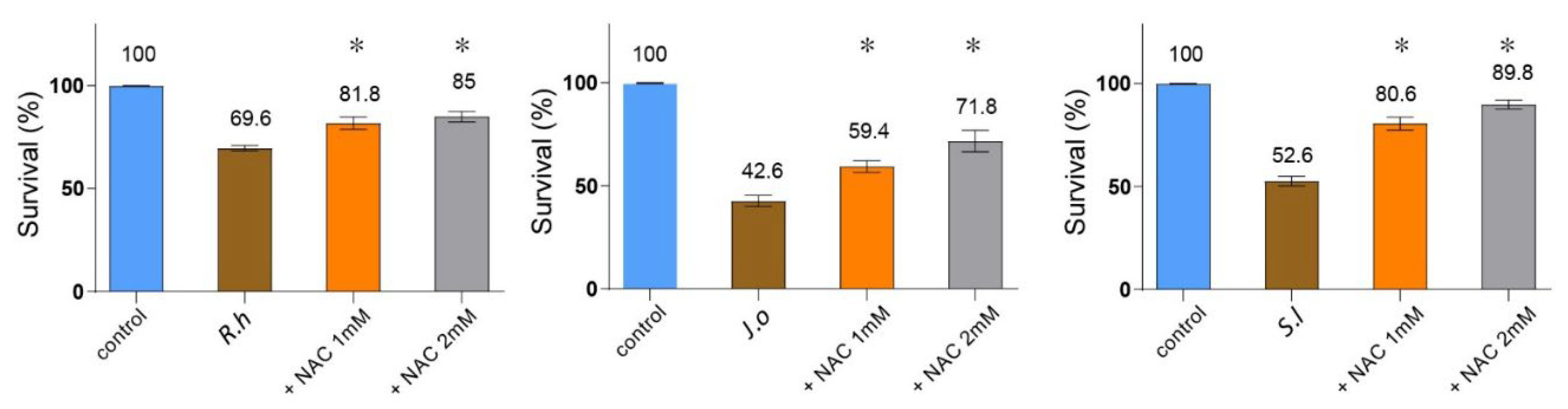

2.9. ROS Contributes to the Nematocidal Action of Herbal Extracts

Given that several of these compounds exert their bioactivities through ROS generation, and that ROS is also known to contribute to insecticidal activity, we examined whether ROS contributes to nematocidal death. To test this, we co-treated

C. elegans with each extract and the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and measured survival rates. All three extracts significantly reduced nematode survival compared to the untreated control (

Figure 5,

R.h: 69.6%,

J.o: 42.6%,

S.l: 52.6%;

p < 0.001, n = 30). Co-administration of NAC restored survival in a concentration-dependent manner: at 1 mM NAC, survival rose to 81.8% (

p = 0.0160) for

R.h, 59.4% (

p = 0.0120) for

J.o, and 80.6% (

p = 0.0095) for

S.l; at 2 mM, it further increased to 85.0% (

p = 0.0079), 71.8% (

p = 0.0117), and 89.8% (

p = 0.0093), respectively. These results demonstrate that the nematocidal effect of all three herbs is, at least in part, mediated through ROS-dependent cytotoxicity.

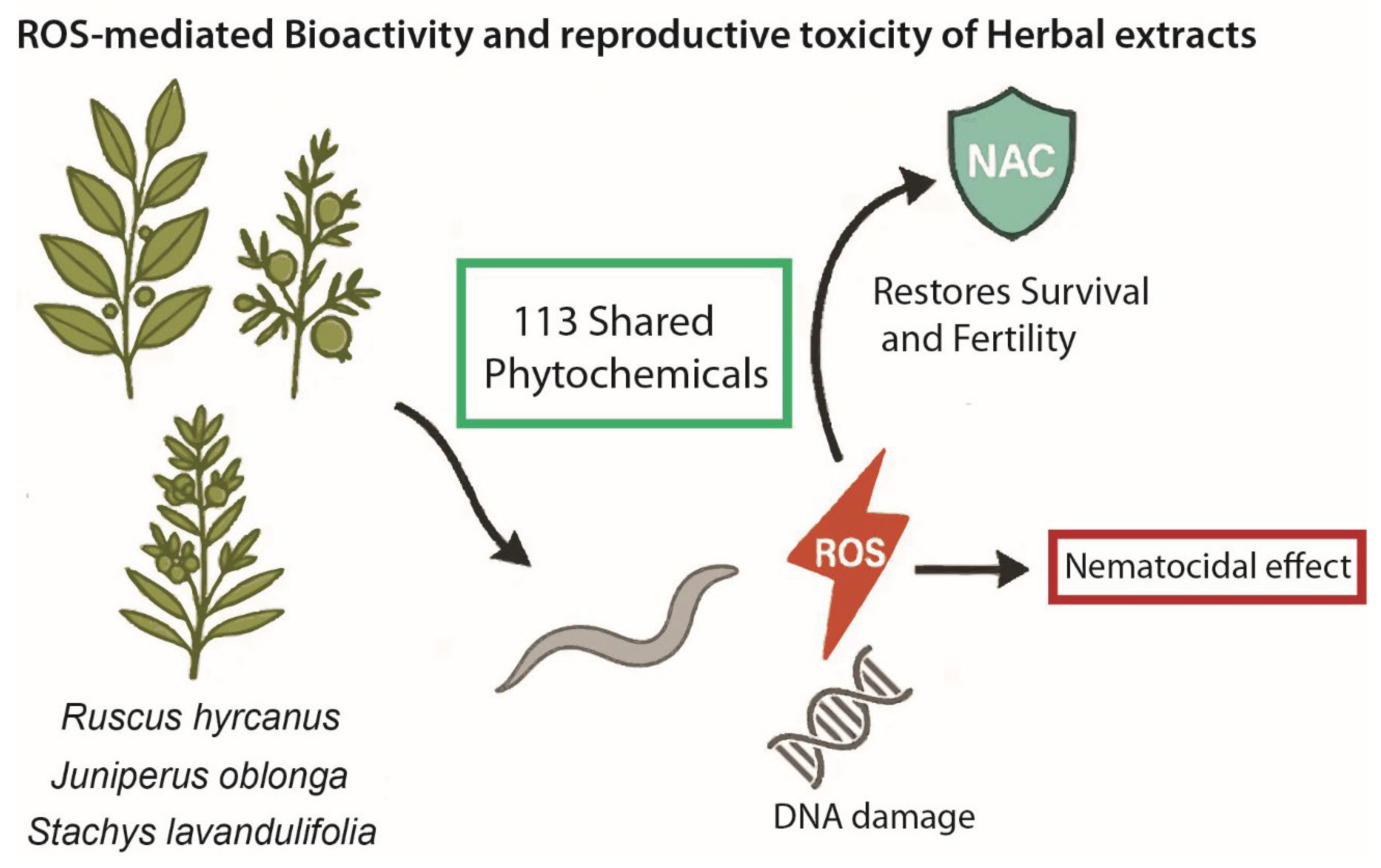

Taken together, our compound categorization revealed that multiple constituents from the three herbal extracts possess nematocidal or related bioactivities, frequently mediated through ROS generation, while a few others confer stress resistance or longevity benefits in

C. elegans. Functional assays using the ROS scavenger NAC further demonstrated that the nematocidal effect of all three extracts is, at least in part, dependent on ROS-mediated cytotoxicity (

Figure 6). These findings suggest that the biological activities of the herbal extracts arise from a complex interplay of both cytotoxic and protective compounds, with ROS acting as a central mechanism underlying their nematocidal action.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Strains and Alleles

All

C. elegans strains were maintained at 20°C under standard laboratory conditions, as previously described [

39]. The N2 Bristol strain was used as the wild-type reference.

3.2. Herb Extraction and LC-MS Assay

The three herbs were collected from Armenia as previously described [

18,

19]. Plant material was cleaned, air-dried, and ground into a coarse powder before methanol extraction. The resulting extracts were sequentially fractionated with n-hexane, dichloromethane, and n-butanol to yield hexane (-H), butanol (-B), and aqueous (-A) fractions; the butanol fraction was used for all subsequent experiments. Extracts were dissolved in DMSO (1 mg/mL) and diluted in M9 buffer to a final concentration of 0.03 µg/mL. LC–MS profiling was performed by YanBo times (Beijing, China), and English names were translated from the provided Chinese names.

3.3. Survival, Larval Arrest/Lethality, and HIM

Synchronized L1 larvae were obtained from gravid hermaphrodites on NGM plates following established protocols [

21,

40]. Larvae were incubated in herb extract solutions in 96-well plates at 20°C with gentle agitation. Survival and mobility were assessed after 24 h, and brood size was measured over 4–5 days post-L4 stage. Larval arrest/lethality was defined as the percentage of hatched worms failing to reach adulthood, and male proportion (Him) as the percentage of adult males. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests with 95% confidence intervals. All experiments were performed in triplicate [

40].

3.4. OS-Dependent Nematocidal Activity Assay

To determine whether the nematocidal activity of the herbal extracts was mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), C. elegans were co-treated with the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, Sigma-Aldrich). Synchronized L4-stage worms (n = 30 per treatment) were transferred to NGM plates supplemented with each herbal extract at the indicated concentrations. NAC was freshly prepared in M9 buffer and added to achieve final concentrations of 1 mM or 2 mM. Worms were incubated with herbal extracts with or without NAC at 20 °C for 24 h. Following incubation, worm survival was scored under a dissecting microscope. Worms failing to respond to gentle touch with a platinum wire were considered dead. Survival rates were determined from three independent biological replicates.

3.5. Assessment of E. coli Growth

The impact of herb extracts on the proliferation of

E. coli OP50 was assessed by measuring optical density at 600 nm, following the methodology outlined in [

19]. Each extract was tested at a concentration of 0.03 µg/mL to evaluate potential antibacterial activity by tracking bacterial growth over time.

3.6. Immunofluorescence Analysis

Whole-mount gonads were processed for immunofluorescence staining according to previously established protocols [

21,

23,

41]. The primary antibody used was rabbit anti-pCHK-1 (1:250, Cell Signaling, Ser345), and detection was performed with Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:300, Jackson Immunochemicals). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2-E inverted microscope equipped with a DSQi2 camera, with optical sections collected at 0.2 μm intervals. A 60× objective combined with 1.5× auxiliary magnification was used, and deconvolution was applied via NIS Elements software (Nikon). Partial projections of half-nuclei are displayed.

3.7. Quantification of pCHK-1 Foci and Germline Apoptosis

pCHK-1 foci were quantified as described in [

21,

23], analyzing five to ten gonads per treatment. Statistical analyses were conducted using either a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test or T test with a 95% confidence level. Germline apoptosis was evaluated using acridine orange staining in age-matched worms at 20 hours post-L4 stage, following [

42]. Between 20 and 30 gonads per condition were scored using a Nikon Ti2-E fluorescence microscope. Significance was assessed with a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test at a 95% confidence interval.

3.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from young hermaphrodites, and first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the ABscript II First Strand Kit (ABclonal, RK20400). qPCR reactions were carried out with ABclonal 2X SYBR Green Fast Mix (RK21200) on a LineGene 4800 system (BIOER, FQD48A). The cycling protocol consisted of an initial 95°C denaturation for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 20 seconds. A melting curve analysis from 60°C to 95°C verified amplicon specificity. The tubulin gene tba-1 served as an internal reference based on C. elegans microarray data. All reactions were performed at least in duplicate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Nematocidal and Fertility-Reducing Effects

This study demonstrates that extracts from Ruscus hyrcanus (R.h), Juniperus oblonga (J.o), and Stachys lavandulifolia (S.l) exert pronounced biological activity in Caenorhabditis elegans, manifested as reduced survival, developmental arrest, and markedly decreased reproductive output. Beyond these outcomes, the extracts perturbed meiotic progression and increased the HIM phenotype, with S.l producing the strongest impact. These findings suggest that phytochemicals within these herbs influence germline integrity, and that fertility reduction reflects not only general toxicity but also impaired meiotic fidelity. Interestingly, these changes occurred without activation of canonical DNA damage checkpoints in R.h and J.o, raising the possibility that their influence on genome surveillance proceeds through non-canonical or herb-specific mechanisms, highlighting the importance of considering both bioactivity and potential safety concerns.

4.2. ROS-Dependent Cytotoxicity as a Common Mechanism

Our functional assays provide strong evidence that ROS generation is a unifying mechanism underlying the biological effects of all three herbs. Co-treatment with the ROS scavenger NAC substantially restored survival in a dose-dependent manner, confirming that ROS-dependent cytotoxicity accounts for much of the lethality and fertility reduction. These findings establish oxidative stress as a central mediator of herb-induced toxicity, independent of bacterial food supply, and position ROS as a key determinant of physiological outcomes. Importantly, this underscores that phytochemicals can act as a double-edged sword—exerting potent nematocidal activity through ROS generation, but also causing pronounced cytotoxic effects that compromise genome stability, an issue highly relevant to safety assessment.

4.3. Herb-Specific Differences in DNA Damage Responses

Although ROS-dependent cytotoxicity was a shared feature across all three extracts, they exhibited some herb-specific effects on genome stability. Notably, S. lavandulifolia showed unique changes in markers associated with DNA repair and apoptosis, suggesting a secondary, herb-specific modulation of genome maintenance. In contrast, R. hyrcanus and J. oblonga induced strong lethality and fertility reduction without detectable canonical checkpoint activation. These observations indicate that while ROS-mediated effects represent the central mechanism driving bioactivity, certain phytochemicals may additionally influence genome regulation in a herb-specific manner. Overall, these findings highlight both the broad bioactivity of the extracts and the importance of evaluating their safety-relevant impacts, providing insights for future nutraceutical and functional food applications.

4.4. Chemical Composition as a Basis for Functional Diversity

LC–MS profiling provides insight into the source of both shared and divergent effects. All three herbs contained 113 common compounds, including 14 with known or predicted bioactivity. This overlap likely explains their conserved ROS-dependent effects. However, the relative abundance and ratios of these compounds differed considerably across the extracts. Such variation provides a plausible explanation for the distinctive activity of S.l on DNA repair pathways, compared to the primarily ROS-driven responses of R.h and J.o. These findings highlight the importance of phytochemical composition and relative abundance in determining both functional outcomes and safety-relevant toxicological profiles.

5. Concluding Perspective

Taken together, our results reveal a dual framework of action: (1) a shared ROS-dependent mechanism that underlies reduced survival and fertility across all three herbs, and (2) herb-specific modulation of genome stability, with S.l uniquely affecting DNA repair and checkpoint responses. This integrative perspective highlights the importance of both qualitative and quantitative variation in phytochemical composition for shaping biological outcomes. Future work should aim to isolate the active constituents and determine how their interactions contribute to the balance between beneficial and adverse effects. By linking phytochemical composition with bioactivity and safety-relevant outcomes, our findings provide a foundation for evaluating traditional medicinal plants in the context of both nutraceutical potential and toxicological risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Methodology: Q.M., A.H., Z.L.; Validation: Q.M., A.H.; Investigation: Q.M., A.H., Z.L. and H.-M.K.; Reference collection and verification: A.H.; Resources: R.P.B. and H.-M.K.; Writing—original draft: H.-M.K.; Writing—review and editing: R.P.B. and H.-M.K.; Proofreading: Q.M., A.H., R.P.B., Z.L. and H.-M.K.; Supervision: H.-M.K.; Project administration: H.-M.K.; Funding acquisition: H.-M.K. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Kunshan Shuangchuang grant award from Kunshan city (KSSC202202060), DATA + Sustainability Grant from Duke Kunshan University to H.-M.K.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kim laboratory for discussions and proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dehghan, H., Y. Sarrafi, and P. Salehi, Antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of 11 herbal plants from Hyrcania region, Iran. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 2016. 24(1): p. 179-188.

- Ghorbani, S., et al., Genetic structure, molecular and phytochemical analysis in Iranian populations of Ruscus hyrcanus (Asparagaceae)伊朗天门冬科 Ruscus hyrcanus 种群的遗传结构、分子和植物化学分析. Industrial Crops and Products, 2020. 154: p. 112-116.

- Mozaffarian, V., Identification of medicinal and aromatic plants of Iran. Vol. 1. 2013: Farhang Moaser Publishers.

- Naidoo, C.M., et al., Bioactive Compounds and Biological Activities of Ruscus Species, in Bioactive Compounds in the Storage Organs of Plants. 2023, Springer, Cham. p. 1-20.

- Falcão, S., et al., Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of hydrodistilled oil from juniper berries. Industrial Crops and Products, 2018. 124: p. 878-884.

- Qiao, Y., et al., Labdane and Abietane Diterpenoids from Juniperus oblonga and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Molecules, 2019. 24(8): p. 1561.

- Delnavazi, M.-R., et al., Cytotoxic Flavonoids from the Aerial Parts of Stachys lavandulifolia Vahl. Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2018. 24(4): p. 332-339.

- Hassanpouraghdam, M.B., et al., Stachys lavandulifolia Populations: Volatile Oil Profile and Morphological Diversity. Agronomy, 2022. 12(6): p. 1430.

- Bahadori, M.B., et al., The health benefits of three Hedgenettle herbal teas (Stachys byzantina, Stachys inflata, and Stachys lavandulifolia) - profiling phenolic and antioxidant activities. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 2020. 36: p. 101-134.

- Barreto, R.S.S., et al., Evidence for the involvement of TNF-α and IL-1β in the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity of Stachys lavandulifolia Vahl. (Lamiaceae) essential oil and (-)-α-bisabolol, its main compound, in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2016. 191: p. 9-18.

- Hajhashemi, V., A. Ghannadi, and S. Sedighifar, Analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of the hydroalcoholic, polyphenolic and boiled extracts of Stachys lavandulifolia. Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2007. 1(2): p. 92-98.

- Rabbani, M., S.E. Sajjadi, and H.R. Zarei, Anxiolytic effects of Stachys lavandulifolia Vahl on the elevated plus-maze model of anxiety in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2003. 89(2): p. 271-276.

- Hodgkin, J., H.R. Horvitz, and S. Brenner, Nondisjunction Mutants of the Nematode CAENORHABDITIS ELEGANS. Genetics, 1979. 91(1): p. 67-94.

- Kim, H.M. and Z. Liu, LSD2 Is an Epigenetic Player in Multiple Types of Cancer and Beyond. Biomolecules, 2024. 14(5): p. 88.

- Ren, X., et al., Histone Demethylase AMX-1 Regulates Fertility in a p53/CEP-1 Dependent Manner. Front Genet, 2022. 13: p. 929716.

- Kim, H.M., X. Zheng, and E. Lee, Experimental Insights into the Interplay between Histone Modifiers and p53 in Regulating Gene Expression. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(13): p. 21-35.

- Cinquin, O., et al., Progression from a stem cell-like state to early differentiation in the C. elegans germ line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(5): p. 2048-53.

- Meng, Q., R.P. Borris, and H.M. Kim, Torenia sp. Extracts Contain Multiple Potent Antitumor Compounds with Nematocidal Activity, Triggering an Activated DNA Damage Checkpoint and Defective Meiotic Progression. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2024. 17(5): p. 611.

- Meng, Q., et al., Exploring the Impact of Onobrychis cornuta and Veratrum lobelianum Extracts on C. elegans: Implications for MAPK Modulation, Germline Development, and Antitumor Properties. Nutrients, 2023. 16(1): p. 1-22.

- Hofmann, E.R., et al., Caenorhabditis elegans HUS-1 is a DNA damage checkpoint protein required for genome stability and EGL-1-mediated apoptosis. Curr Biol, 2002. 12(22): p. 1908-18.

- Kim, H.M. and M.P. Colaiacovo, ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the C. elegans Germline. PLoS Genet, 2014. 10(10): p. e1004723.

- Marechal, A. and L. Zou, DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013. 5(9): p. 112-131.

- Kim, H.M. and M.P. Colaiacovo, New Insights into the Post-Translational Regulation of DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics, 2015. 200(2): p. 495-504.

- Derry, W.B., A.P. Putzke, and J.H. Rothman, Caenorhabditis elegans p53: role in apoptosis, meiosis, and stress resistance. Science, 2001. 294(5542): p. 591-5.

- Arvanitis, M., et al., Apoptosis in C. elegans: lessons for cancer and immunity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2013. 3: p. 67-77.

- Zhang, W.J., et al., Contact toxicity and repellency of the essential oil from Mentha haplocalyx Briq. against Lasioderma serricorne. Chem Biodivers, 2015. 12(5): p. 832-9.

- Wang, T., et al., Evaluation of Tanshinone IIA Developmental Toxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Molecules, 2017. 22(4): p. 24.

- Shang, X.-F., et al., Insecticidal and antifungal activities of Rheum palmatum L. anthraquinones and structurally related compounds. Industrial Crops and Products, 2019. 137(1): p. 508-520.

- Zhang, T.-T., L. Yang, and J.-G. Jiang, Tormentic acid in foods exerts anti-proliferation efficacy through inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015. 19(A): p. 575-583.

- Ge, Y., et al., Naringenin prolongs lifespan and delays aging mediated by IIS and MAPK in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct, 2021. 12(23): p. 12127-12141.

- Perez-Coll, C.S. and J. Herkovits, Lethal and teratogenic effects of naringenin evaluated by means of an amphibian embryo toxicity test (AMPHITOX). Food Chem Toxicol, 2004. 42(2): p. 299-306.

- Allam, G. and A.S. Abuelsaad, In vitro and in vivo effects of hesperidin treatment on adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni. J Helminthol, 2014. 88(3): p. 362-70.

- Kawasaki, I., et al., Apigenin inhibits larval growth of Caenorhabditis elegans through DAF-16 activation. FEBS Lett, 2010. 584(16): p. 3587-91.

- Goel, V., et al., Targeting the nervous system of the parasitic worm, Haemonchus contortus with quercetin. Heliyon, 2023. 9(2): p. e13699.

- Marshall, M.E., et al., Growth-inhibitory effects of coumarin (1,2-benzopyrone) and 7-hydroxycoumarin on human malignant cell lines in vitro. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 1994. 120(1): p. S3-10.

- Park, E.J., et al., Multiple pathways are involved in palmitic acid-induced toxicity. Food Chem Toxicol, 2014. 67: p. 26-34.

- Cai, W.J., et al., Icariin and its derivative icariside II extend healthspan via insulin/IGF-1 pathway in C. elegans. PLoS One, 2011. 6(12): p. e28835.

- Yamamoto, R., et al., Luteolin enhances oxidative stress tolerance via the daf-16 pathway in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Science and Technology Research, 2024. 30(2): p. 253-260.

- Brenner, S., The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics, 1974. 77(1): p. 71-94.

- Kim, H.M. and M.P. Colaiacovo, DNA Damage Sensitivity Assays in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-Protocol, 2015. 5(11): p. 1-12.

- Colaiacovo, M.P., et al., Synaptonemal complex assembly in C. elegans is dispensable for loading strand-exchange proteins but critical for proper completion of recombination. Dev Cell, 2003. 5(3): p. 463-74.

- Kelly, K.O., et al., Caenorhabditis elegans msh-5 is required for both normal and radiation-induced meiotic crossing over but not for completion of meiosis. Genetics, 2000. 156(2): p. 617-30.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent nematocidal activity of three herb extracts. A) Survival of C. elegans decreased with increasing extract concentration (0.03–3 µg/mL), revealing potent, dose-responsive toxicity. B) Herb extracts did not alter E. coli OP50 growth (OD₆₀₀) after 24 h, confirming that nematode lethality is independent of bacterial food supply. Asterisks denote significance versus control group; n.s. indicates not significant.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent nematocidal activity of three herb extracts. A) Survival of C. elegans decreased with increasing extract concentration (0.03–3 µg/mL), revealing potent, dose-responsive toxicity. B) Herb extracts did not alter E. coli OP50 growth (OD₆₀₀) after 24 h, confirming that nematode lethality is independent of bacterial food supply. Asterisks denote significance versus control group; n.s. indicates not significant.

Figure 2.

Herb-induced meiotic and fertility defects. A) Nuclear spacing in PMT, TZ and pachytene was unchanged in R.h and J.o; only S.l induced a significant increase in pachytene nuclear gap (P<0.0001, Mann-Whitney test). B) Representative images of germline nuclei at PMT(premeiotic tip) and pachytene stages upon herb treatment. Bar= 2µm. C) Frequency of crescent-shaped nuclei remained unchanged across PMT, TZ, and pachytene stages (Mann-Whitney test). D) No chromatin bridges were detected in any herb-treated gut cells, indicating absence of distinct mitotic segregation defects. Bar= 10µm. E) Total brood size was significantly reduced from day 1 to day 4 in all herb groups, confirming compromised fertility without mitotic disruption. Asterisks denote significance versus control group. Right) The total brood size summed over 4 days is indicated.

Figure 2.

Herb-induced meiotic and fertility defects. A) Nuclear spacing in PMT, TZ and pachytene was unchanged in R.h and J.o; only S.l induced a significant increase in pachytene nuclear gap (P<0.0001, Mann-Whitney test). B) Representative images of germline nuclei at PMT(premeiotic tip) and pachytene stages upon herb treatment. Bar= 2µm. C) Frequency of crescent-shaped nuclei remained unchanged across PMT, TZ, and pachytene stages (Mann-Whitney test). D) No chromatin bridges were detected in any herb-treated gut cells, indicating absence of distinct mitotic segregation defects. Bar= 10µm. E) Total brood size was significantly reduced from day 1 to day 4 in all herb groups, confirming compromised fertility without mitotic disruption. Asterisks denote significance versus control group. Right) The total brood size summed over 4 days is indicated.

Figure 3.

S.l, but not R.h or J.o, mildly activates the ATM/pCHK-1 axis and downstream apoptosis, without triggering a canonical DNA damage checkpoint response. (A) qPCR analysis of atm-1 and atl-1 expression. R.h and J.o extracts did not alter transcript levels, whereas S.l extract significantly reduced atm-1 expression. (B) pCHK-1 foci in pachytene-stage nuclei. R.h and J.o showed no change compared to controls (n.s.), while S.l treatment significantly increased pCHK-1 foci. Bar= 2µm. (C) Germline apoptosis. R.h and J.o extracts showed no change (n.s.), whereas S.l extract significantly elevated apoptosis. Asterisks denote significance versus control group.

Figure 3.

S.l, but not R.h or J.o, mildly activates the ATM/pCHK-1 axis and downstream apoptosis, without triggering a canonical DNA damage checkpoint response. (A) qPCR analysis of atm-1 and atl-1 expression. R.h and J.o extracts did not alter transcript levels, whereas S.l extract significantly reduced atm-1 expression. (B) pCHK-1 foci in pachytene-stage nuclei. R.h and J.o showed no change compared to controls (n.s.), while S.l treatment significantly increased pCHK-1 foci. Bar= 2µm. (C) Germline apoptosis. R.h and J.o extracts showed no change (n.s.), whereas S.l extract significantly elevated apoptosis. Asterisks denote significance versus control group.

Figure 4.

LC–MS profiling of 113 compounds in R.h, J.o, and S.l extracts, highlighting potential nematocidal constituents. (A) Peak intensities (y-axis) are shown for 113 compounds commonly detected across all three herb extracts (x-axis).

R.h,

J.o, and

S.l are represented by red, green, and blue traces, respectively. The complete list of compounds is provided in

Supplementary Table S1. (B) Among these 113 compounds, 14 were identified as potential or known nematocidal compounds. Their peak intensities are shown on the y-axis.

R.h,

J.o, and

S.l are represented by red, green, and blue traces, respectively. Compounds detected more than once are indicated with an asterisk.

Figure 4.

LC–MS profiling of 113 compounds in R.h, J.o, and S.l extracts, highlighting potential nematocidal constituents. (A) Peak intensities (y-axis) are shown for 113 compounds commonly detected across all three herb extracts (x-axis).

R.h,

J.o, and

S.l are represented by red, green, and blue traces, respectively. The complete list of compounds is provided in

Supplementary Table S1. (B) Among these 113 compounds, 14 were identified as potential or known nematocidal compounds. Their peak intensities are shown on the y-axis.

R.h,

J.o, and

S.l are represented by red, green, and blue traces, respectively. Compounds detected more than once are indicated with an asterisk.

Figure 5.

Nematocidal activity of three herb extracts is mediated via ROS-dependent cytotoxicity. C. elegans were co-treated with each extract (R.h, J.o, and S.l) and the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), and survival was recorded. All extracts significantly reduced survival compared to the untreated control (n = 30). Co-administration of NAC restored survival in a concentration-dependent manner (1 mM and 2 mM), demonstrating that the nematocidal effect is, at least in part, mediated through ROS-dependent cytotoxicity. Asterisks indicate statistical significance versus the herb-only group.

Figure 5.

Nematocidal activity of three herb extracts is mediated via ROS-dependent cytotoxicity. C. elegans were co-treated with each extract (R.h, J.o, and S.l) and the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), and survival was recorded. All extracts significantly reduced survival compared to the untreated control (n = 30). Co-administration of NAC restored survival in a concentration-dependent manner (1 mM and 2 mM), demonstrating that the nematocidal effect is, at least in part, mediated through ROS-dependent cytotoxicity. Asterisks indicate statistical significance versus the herb-only group.

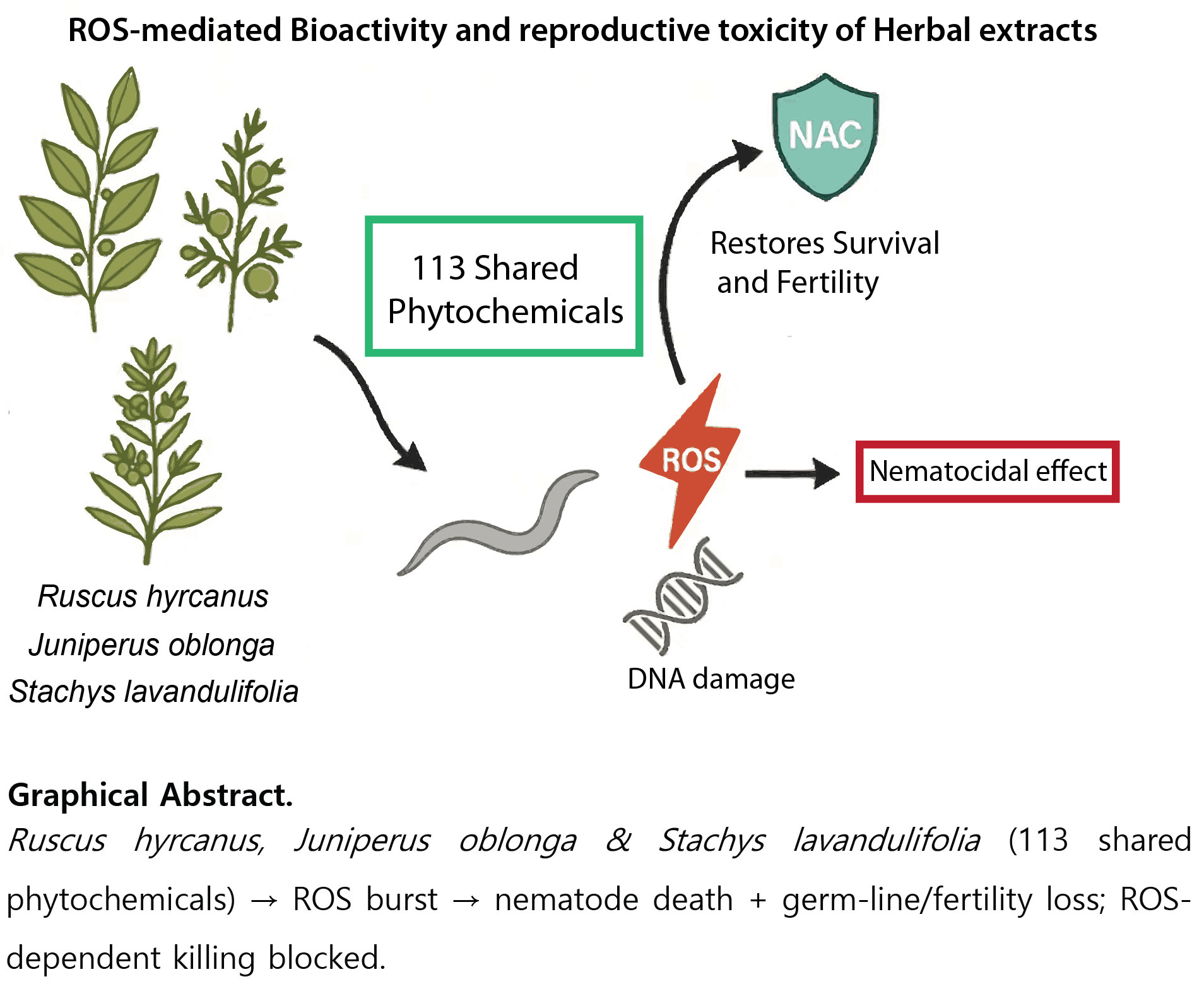

Figure 6.

ROS-mediated bioactivity and reproductive toxicity of herbal extracts in C. elegans. Extracts of Ruscus hyrcanus, Juniperus oblonga and Stachys lavandulifolia—sharing 113 phytochemicals—generate ROS that kills nematodes and causes germline/fertility defects; this ROS-driven lethality is suppressed by NAC.

Figure 6.

ROS-mediated bioactivity and reproductive toxicity of herbal extracts in C. elegans. Extracts of Ruscus hyrcanus, Juniperus oblonga and Stachys lavandulifolia—sharing 113 phytochemicals—generate ROS that kills nematodes and causes germline/fertility defects; this ROS-driven lethality is suppressed by NAC.

Table 1.

Categorical grouping of the 113 LC–MS-identified compounds shared among Ruscus hyrcanus, Juniperus oblonga, and S. lavandulifolia. Interestingly, all 113 compounds are present in identical compounds across the three extracts and are classified here into four major chemical families: Phenolic compounds, Glycosides, Isoprenoids, and Lipids & derivatives. Each subclass is listed to highlight the chemical diversity underlying the shared bioactivity of the herbal extracts.

Table 1.

Categorical grouping of the 113 LC–MS-identified compounds shared among Ruscus hyrcanus, Juniperus oblonga, and S. lavandulifolia. Interestingly, all 113 compounds are present in identical compounds across the three extracts and are classified here into four major chemical families: Phenolic compounds, Glycosides, Isoprenoids, and Lipids & derivatives. Each subclass is listed to highlight the chemical diversity underlying the shared bioactivity of the herbal extracts.

| Types of compounds |

Subclass |

| Phenolic compounds |

Flavonoids |

| Coumarins |

| Lignans |

| Anthraquinones |

| Phenols |

| Polyphenols |

| Glycosides |

Glucosides |

| Disaccharides |

| Iridoids |

| Isoprenoids |

Terpenes |

| Terpenoids |

| Isoprenoids |

| Lipids & derivatives |

Fatty acids |

| Carboxylic acid esters |

Table 2.

Identical nematocidal compounds shared among three herb extracts. LC–MS analysis revealed 113 compounds common to R.h, J.o, and S.l; among these, 14 compounds with reported nematocidal activity are listed here. All compounds are present in identical forms across the three extracts and are categorized into five chemical classes: Flavonoids, Terpenoids, Anthraquinones, Coumarins, and Fatty Acids. These shared constituents are proposed to underlie the ROS-dependent nematocidal activity observed in co-treatment assays. Darker shading within the table indicates higher LC–MS peak intensity.

Table 2.

Identical nematocidal compounds shared among three herb extracts. LC–MS analysis revealed 113 compounds common to R.h, J.o, and S.l; among these, 14 compounds with reported nematocidal activity are listed here. All compounds are present in identical forms across the three extracts and are categorized into five chemical classes: Flavonoids, Terpenoids, Anthraquinones, Coumarins, and Fatty Acids. These shared constituents are proposed to underlie the ROS-dependent nematocidal activity observed in co-treatment assays. Darker shading within the table indicates higher LC–MS peak intensity.

| Types of compounds |

R.h |

J.o |

S.l |

| Flavonoids |

Naringenin 7-O-β-D-glucuronide methyl ester |

Naringenin 7-O-β-D-glucuronide methyl ester |

Naringenin 7-O-β-D-glucuronide methyl ester |

| 3-O-Methylquercetin |

3-O-Methylquercetin |

3-O-Methylquercetin |

| Quercetin 3-O-neohesperidoside |

Quercetin 3-O-neohesperidoside |

Quercetin 3-O-neohesperidoside |

| Quercetin 3,7-di-O-rhamnopyranoside |

Quercetin 3,7-di-O-rhamnopyranoside |

Quercetin 3,7-di-O-rhamnopyranoside |

| 3-O-Methylquercetin 4',7-di-β-D-glucopyranoside |

3-O-Methylquercetin 4',7-di-β-D-glucopyranoside |

3-O-Methylquercetin 4',7-di-β-D-glucopyranoside |

| Hesperidin |

Hesperidin |

Hesperidin |

| Quercetin-3-O-D-glucosyl]-(1-2)-L-rhamnoside |

Quercetin-3-O-D-glucosyl]-(1-2)-L-rhamnoside |

Quercetin-3-O-D-glucosyl]-(1-2)-L-rhamnoside |

| Taxifolin 7-rhamnoside |

Taxifolin 7-rhamnoside |

Taxifolin 7-rhamnoside |

| Terpenoids |

Menthyl acetate |

Menthyl acetate |

Menthyl acetate |

| |

Tanshinone II |

Tanshinone II |

Tanshinone II |

| |

Tormentic acid |

Tormentic acid |

Tormentic acid |

| Anthraquinones |

Emodin |

Emodin |

Emodin |

| Coumarins |

7-Hydroxycoumarin |

7-Hydroxycoumarin |

7-Hydroxycoumarin |

| Fatty Acids |

palmitic acid |

palmitic acid |

palmitic acid |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).