Introduction

Previously, we conducted a screening of herbal extracts to assess their potential anti-tumor effects using

C. elegans. [

1]. Of the extracts tested, 16% showed reduced survival rates and induced larval arrest or lethality, suggesting that larval arrest plays a crucial role in determining worm viability. Notably, a small subset of herbal extracts, including those from

Lappula patula,

Onobrychis cornuta, and

Torenia species, exhibited a remarkable increase in male occurrence and reduced survivability. Building on these observations, this report focuses on

Lappula patula to investigate its effects on growth, germline development, DNA damage checkpoints, and repair mechanisms in the

C. elegans model.

General Overview of the Lappula Genus (Boraginaceae)

The genus

Lappula, belonging to the family

Boraginaceae, consists of approximately 50 to 70 species [

2,

3], predominantly distributed across Eurasia, North Africa, the Americas, and Australia [

4,

5]. These species thrive in temperate regions, often inhabiting dry, sandy soils, grasslands, hillsides, and disturbed areas. For instance,

L. squarrosa, a rare species, is sporadically found in Central Europe. Central Asia, particularly Xinjiang Province in China, is recognized as a diversity hotspot for

Lappula species [

4,

5].

Lappula patula, in particular, is recognized as a species with a fragmented and localized distribution within certain regions. In some areas, it has been noted as a floristic rarity and regional novelty, with occurrences in limited or peripheral environments [

6].

Lappula plants typically feature blue or white flowers with five throat appendages, a subulate gynobase, and nutlets arranged in clusters of four. These nutlets, often equipped with marginal wings or glochids, facilitate dispersal by attaching to animals or surfaces [

7]. L. patula differs from its closely related species, L. botschantzevii, in both the size of the corolla and the structure of the inflorescence [

8].

Taxonomy and Phylogeny

The taxonomy of

Lappula has undergone significant refinement over time. Early classifications identified 38 species based on nutlet morphology [

9]. Subsequently, Popov et al. classified 39 species in the Flora USSR and introduced a more detailed infrageneric system [

7]. In the 21st century, Ovczinnikova et al. expanded the classification to 70 species [

3,

4]. However, molecular phylogenetic studies revealed that

Lappula is polyphyletic, leading to the reassignment of some species to other genera, such as

Rochelia and

PseudoLappula [

4,

10]. Recent research highlights the genus’s considerable diversity, particularly in northwestern China [

7].

Medicinal Properties and Uses

Several

Lappula species are known for their medicinal properties. For instance,

Lappula myosotis is used to treat wounds and joint issues due to its anti-inflammatory and insecticidal effects [

11]. Similarly,

Lappula echinata, prevalent in northern China, exhibits antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects, including protection against oxidative damage in macrophages [

12]. Its extracts also demonstrate antibacterial activity, with a quinolone alkaloid found to be effective against pathogens like

Pseudomonas pyocyanea and

Staphylococcus epidermidis [

11]. Traditional uses of

L. echinata include treating chronic diarrhea, with studies indicating its ability to inhibit intestinal smooth muscle contractions [

13].

Additionally,

Lappula species contain polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as stearidonic acid (SDA), which may provide anti-inflammatory and cardiovascular benefits [

14]. However, the presence of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) in

Lappula poses safety risks due to their genotoxic and carcinogenic properties [

14].

Despite these risks, the medicinal potential of the

Lappula genus remains promising.

C. elegans is an excellent model system for assessing the toxicity of herbal compounds. Its simplicity, coupled with genetic similarity to humans, conserved biological pathways, and advanced genetic tools makes it invaluable for toxicity studies [

15,

16,

17,

18].

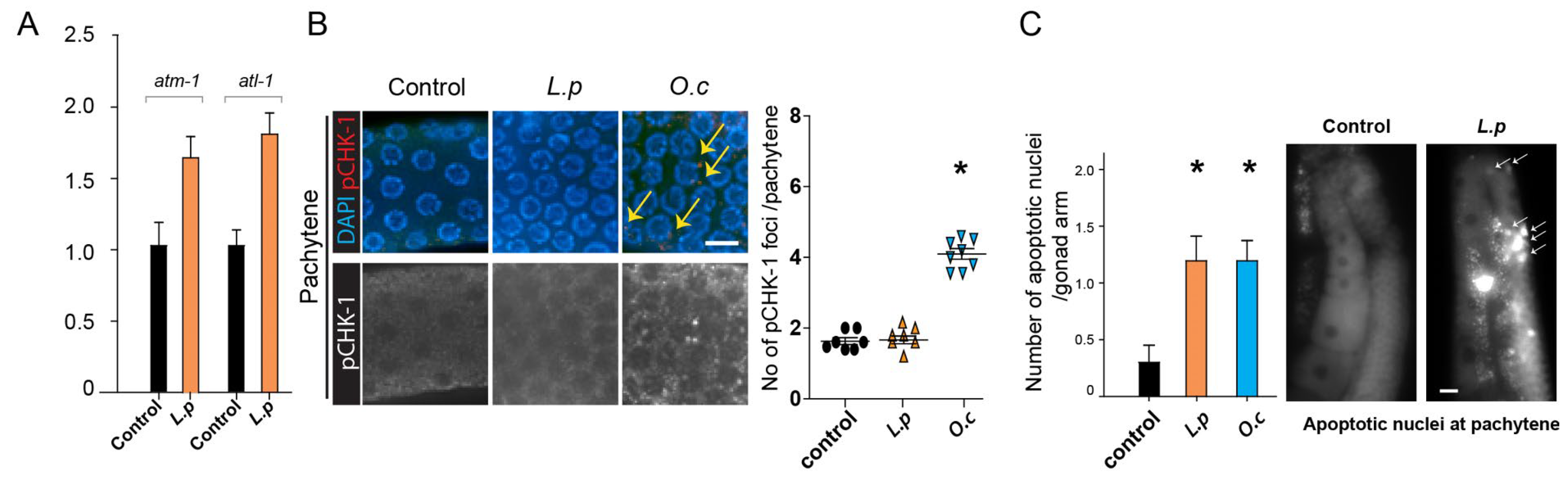

Findings on Lappula Patula

In this study, we observed that Lappula patula extracts activated a DNA damage checkpoint response via ATM/ATR pathways in a pCHK-1 independent manner. This response disrupted germline development and induced pachytene apoptosis, indicating impaired DNA damage repair mechanisms. Further analysis revealed a significant reduction in bivalents and disrupted meiotic progression, highlighting the adverse effects of Lappula patula extracts on developmental processes.

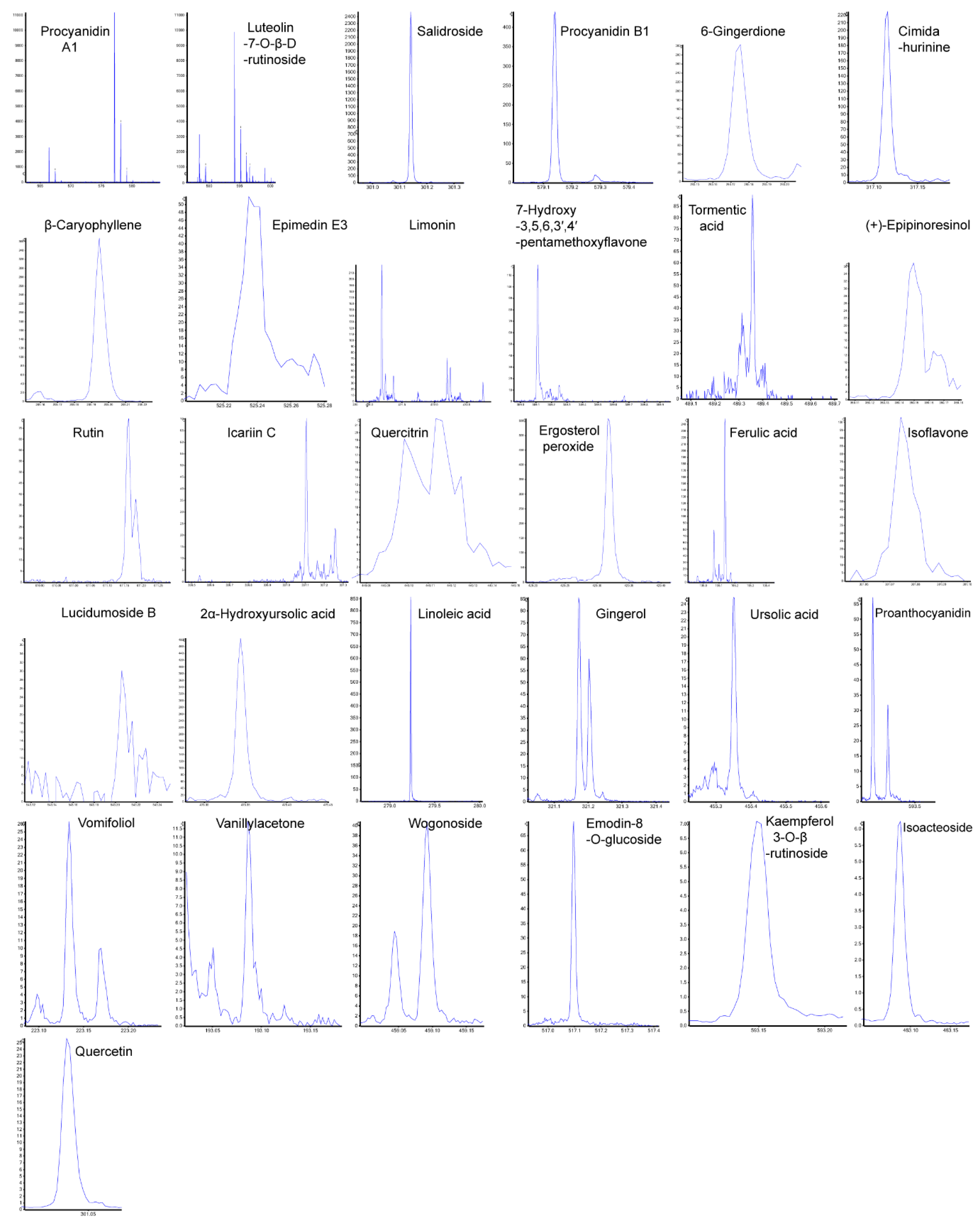

LC-MS analysis identified 112 compounds in Lappula patula extracts, 31of which possess known antitumor activity. Notably, linoleic acid was the only compound overlapping with Onobrychis cornuta, a plant previously identified for its potent antitumor properties. The abundance of anti-tumor compounds in Lappula patula underscores its broader therapeutic potential.

Results

Dose-Dependent Nematocidal and Larval Arrest of Lappula Patula Extracts

To further explore and confirm the nematocidal effects of

Lappula patula (

L.p.) extracts, we conducted a series of experiments to examine whether different concentrations of the extract were correlated with observed changes in

C. elegans phenotypes. This approach was inspired by previous studies on

Onobrychis cornuta (

O.c.) extract, which also exhibited dose-dependent effects on worm survival and larval development [

1]. As the concentration of the herbal extracts increased, we observed a progressive decline in survivability, representing a clear dose-dependent relationship (

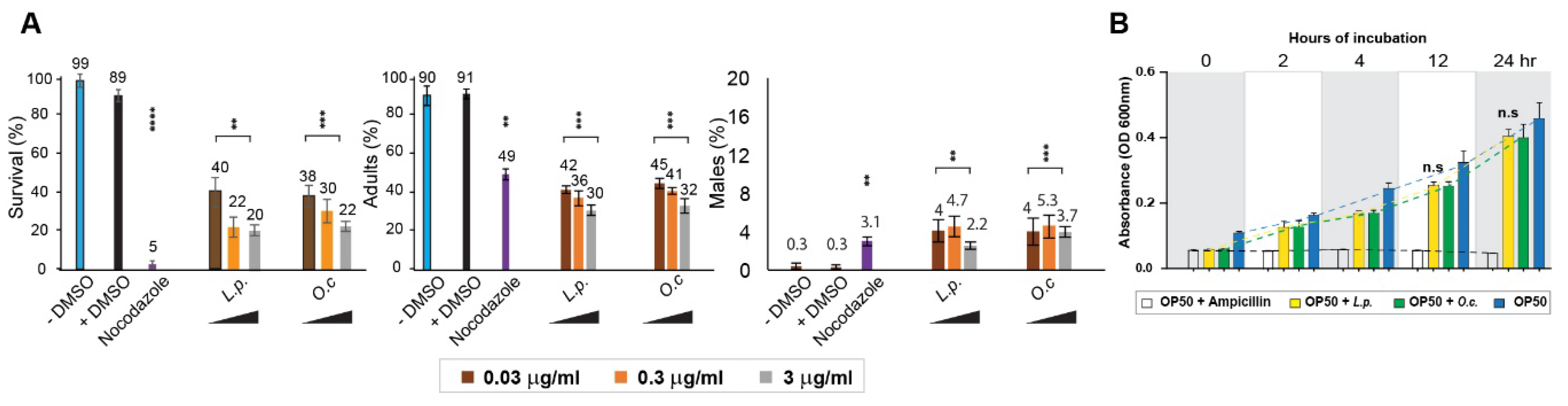

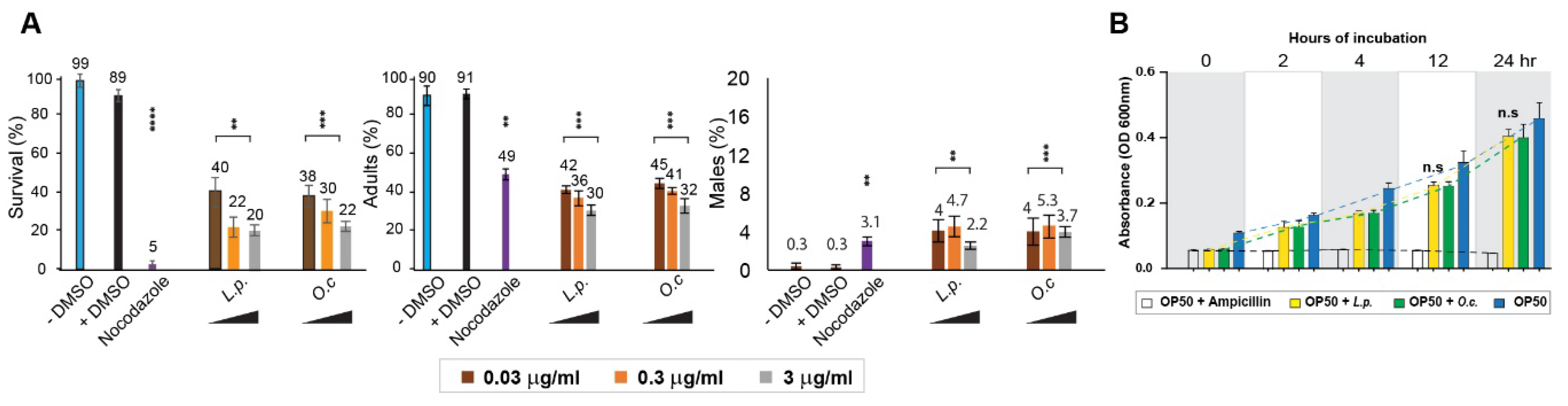

Figure 1A). For instance, in the case of

O. cornuta, the survival rate decreased from 38% to 30%, and finally to 22% with concentrations of 0.03, 0.3, and 3 µg/mL, respectively. Similarly, for

Lappula patula extracts, the survival rate dropped from 40% to 22%, and then to 20% with increasing concentrations of 0.03, 0.3, and 3 µg/mL, respectively. These results demonstrate a strong correlation between extract concentration and worm survival, supporting the hypothesis that higher doses of

Lappula patula extracts significantly impact nematode viability.

In addition to the survival rate, the number of adult worms also declined as the concentration of the herb extracts increased, suggesting that the extracts disrupt mitotic growth and hinder proper development. Specifically, in Lappula patula-exposed worms, the percentage of adults dropped from 42% to 36%, and then to 30% as the concentration increased from 0.03 µg/mL to 0.3 µg/mL and 3 µg/mL, respectively. Similarly, in Onobrychis cornuta-treated worms, the percentage of adults decreased from 45% to 41%, and ultimately to 32%, following the same concentration gradient. This decline in adult worm numbers further reinforces the idea that Lappula patula extracts interfere with normal mitotic division and cellular proliferation in C. elegans.

Although we observed the induction of the High Incidence of Males (HIM) phenotype—characterized by an increase in the proportion of male worms—following exposure to both

Onobrychis cornuta and

Lappula patula extracts, we did not detect a clear dose-dependent pattern for this phenotype. This suggests that the induction of the HIM phenotype may not be directly tied to the concentrations of the herbal extracts, and other factors may contribute to the observed changes in sex chromosome segregation (

Figure 1A). In our study, the HIM phenotype in

Onobrychis cornuta was observed at frequencies of 4%, 5.3%, and 3.7% for 0.03, 0.3, and 3 µg/mL concentrations, respectively, while in

Lappula patula, the HIM incidence was found to be 4%, 4.7%, and 2.2% for the same concentrations. This indicates that although both extracts induce the HIM phenotype, the extent of induction is not directly proportional to the dose of the extract.

Taken together, our findings highlight a clear dose-dependent relationship between Lappula patula extract concentration and the survival rate, as well as the incidence of larval arrest and reduced adult worm numbers. However, the induction of the HIM phenotype does not follow a dose-dependent pattern, suggesting that other mechanisms may be at play in influencing sex chromosome segregation in response to herbal exposure. These observations emphasize the potential nematocidal and cytotoxic nature of Lappula patula.

Impact of Lappula patula Extracts on Nematode Survival and Bacterial Growth

One potential explanation for the observed decrease in C. elegans survival upon exposure to Lappula patula (L.p.) extracts could be a secondary effect related to bacterial growth, which serves as the primary food source for C. elegans in laboratory settings. Given that C. elegans relies on E. coli OP50 for nutrition, it is essential to confirm that the observed nematocidal effects are not confounded by bacterial inhibition. To test this hypothesis, we conducted experiments to assess whether Lappula patula extracts exert any inhibitory effects on the growth of Escherichia coli OP50, the bacterial strain used in C. elegans culturing.

We incubated

E. coli OP50 with

Lappula patula extracts for 24 hours and measured bacterial growth by monitoring optical density (OD) at 600 nm. The results revealed no significant difference in bacterial proliferation between the

Lappula patula-treated group and the DMSO control group, both at 12 and 24 hours of incubation. Specifically, at the 12-hour time point, the optical density was 0.32 for the OP50 + DMSO group and 0.25 for the OP50 +

Lappula patula extract group (

Figure 1B, P=0.2432), indicating no substantial inhibition of bacterial growth. At the 24-hour mark, the OD values were 0.46 for the OP50 + DMSO group and 0.41 for the OP50 +

Lappula patula extract group (P=0.2854), further reinforcing the observation that the herbal extract did not significantly impact bacterial growth under the conditions tested. This finding suggests that the reduced survival of

C. elegans upon exposure to

Lappula patula extracts is not due to a defect in bacterial growth, but rather reflects a direct impact of the extract on nematode health.

Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that Lappula patula extracts significantly impair C. elegans survival and development, including larval arrest and compromised sex chromosome segregation. The observed dose-dependent decrease in worm survivability and the induction of larval arrest further strengthens the idea that Lappula patula extracts exert a potent nematocidal effect. This suggests that the extract targets essential biological processes in C. elegans, rather than affecting their food source. The correlation between increased extract concentration and diminished survival, along with the observation of arrested larval development, highlights the potential of Lappula patula as a promising herbal candidate for further investigation into nematocidal properties, independent of its effects on bacterial growth.

Discussion

This research utilized

C. elegans to evaluate the nematocidal toxicity of

Lappula patula herbal extracts and explore their effects on DNA damage repair and checkpoint responses for the first time (

Figure 5). These findings suggest

L. patula has anti-cancer potential, a topic not studied before, and position it as a promising candidate for cancer therapeutics, warranting further research. A screening of 316 herbal extracts revealed

Lappula patula as a potent inducer of DNA damage checkpoint activation, apoptosis related to DNA damage, HIM phenotypes, impaired meiotic progression, and decreased survival rates. [

1,

22].

The induction of male phenotypes appears to occur only within a certain concentration range, beyond which further increases in dose do not affect the incidence of males. This suggests that male phenotype induction is not a direct consequence of higher doses but may instead result from a saturation effect beyond a specific threshold. In contrast, the dose-dependent larval arrest observed indicates that the herb extract’s effects on worm survivability correlate with its concentration. As the dose increases, larval growth is inhibited, leading to reduced survival rates. This supports the idea that the dose of L. patula extract directly impacts larval development and survival, although it does not appear to further influence male incidence at higher doses.

While it is surprising that

L. patula extract induced pCHK1-independent apoptosis, unlike O. cornuta extracts, several studies have demonstrated CHK1-independent DNA damage-induced apoptosis. For example, inhibition of Chk1 in human tumor cells triggers hyperactivation of ATM, ATR, and Caspase-2, leading to apoptosis after DNA damage [

28]. This is supported by our findings, which show elevated levels of both ATM and ATR upon exposure to

L. patula. Given the presence of numerous antitumor compounds in

L. patula, the synergistic effects of the 31 identified anti-tumor compounds may contribute to the complexity of the mechanism. Therefore, we plan to investigate these mechanisms in more detail through systematic approaches in future studies.

Potential Anti-tumor Properties of Lappula Patula

The components identified in

Lappula patula extracts exhibit a variety of potential anti-tumor effects through different biological mechanisms. Flavonoids such as Quercetin and Rutin, along with phenolic compounds like Ferulic acid, are well-known for their strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [

29]. These properties play a crucial role in tumor suppression and protection against oxidative stress, which can contribute to cancer prevention. Additionally, Ursolic acid and Oleanolic acid, two triterpenoids, have been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and metastasis, potentially playing a significant role in suppressing tumor growth and spread [

30,

31]

The anticancer compounds identified in

Lappula patula extracts play a role in the phenotypes observed in

C. elegans. For example, linoleic acid, an essential omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid present in both

Lappula patula and

Onobrychis cornuta, mimicked the phenotypes induced by the herb extracts. These include increased apoptosis and activation of the MAPK signaling pathway. [

1]. However, while linoleic acid or

O.c extracts induced pCHK-1 foci level,

L.p extracts did not, also suggesting the difference and complex mechanisms of the

L.p and

O.c.

This complexity may stem from diverse compound composition of herb: While most of the compounds identified in

Torenia species extracts were also present in the extracts of

Onobrychis cornuta and

Veratrum lobelianum [

1,

22] However, only linoleic acid found to be a common anti-tumor compound found in among

L.p,

O.c and V.I. suggesting a potential different mode in

L.p. This may explain why

L.p exhibited pCHK-1-independent DNA damage-induced apoptosis, whereas the other three extracts did not.

Research and Application Potential

The diversity of compounds identified in

Lappula patula extracts presents significant opportunities for future research and therapeutic applications. Notably, bioactive substances like Ergosterol peroxide and limonin have the potential to serve as novel candidates for anti-cancer drug development, offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention [

32,

33]. These compounds may share similar mechanisms of action with other promising bioactive molecules by targeting key cellular processes involved in cancer progression. Moreover, when used in combination with existing anti-cancer therapies, they may produce synergistic effects, enhancing the overall efficacy of treatment. The broad chemical profile of these compounds opens up exciting possibilities for the development of innovative drugs and combination therapies that could improve cancer treatment outcomes while minimizing side effects.

The findings indicate that L. patula extract contains a wide variety of bioactive compounds, which may contribute to its therapeutic potential. These results provide a valuable foundation for further pharmacological research and offer insights into the diverse mechanisms through which L. patula may exert its health benefits. Moreover, to fully validate the specificity of L. patula’s effects and deepen our understanding of its molecular mechanisms, it will be essential to conduct comparisons with additional control compounds targeting similar pathways. This approach will help clarify whether the observed effects are specific to L. patula or if they are shared by other compounds with similar biological activities. Investigating these effects using other plant extracts or synthetic compounds that target the same pathways will not only confirm the distinctiveness of L. patula’s actions but also aid in identifying the specific pathways involved, which could be crucial for its potential application. Such studies would be critical in validating L. patula as a promising candidate for future therapeutic development and ensuring that its bioactive compounds are not only effective but also selectively modulate cancer-related pathways.

While this study highlights the therapeutic potential of L. patella, which contains 31 identified anti-tumor compounds, it is important to acknowledge the potential risks associated with its use. Specifically, the extract exhibits cytotoxic effects, including genotoxicity, which could lead to unintended consequences. These risks should be carefully considered, and further studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety profile of L. patella for therapeutic applications.

Conclusions

Lappula patula extracts demonstrate significant nematocidal and cytotoxic effects in C. elegans, including reduced survival, disrupted germline development, and activation of the DNA damage response pathway, leading to apoptosis. These effects, independent of bacterial growth inhibition, highlight the extract’s direct biological impact. This is the first study to use LC-MS to analyze Lappula patula extracts, identifying 31 potential anti-tumor compounds. It also provides new insights into its biological effects, such as germline defects, DNA damage responses, and pCHK-1-independent apoptosis in C. elegans, which have not been explored previously. These findings suggest that L. patula has anti-cancer potential and position it as a promising candidate for cancer therapeutics, warranting further research. Future studies, including in vivo validation in mammalian models and further analysis of the most effective anti-tumor compounds, are essential to fully explore its therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action. However, our findings also raise concerns regarding its cytotoxic properties, underscoring the need for a careful evaluation of its safety. Given the broader medicinal potential of the Lappula genus, it is crucial to balance its therapeutic benefits with the potential risks through continued research.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Alleles

All

C. elegans strains were maintained at 20 °C as previously described [

34]. The N2 obtained from

Caenorhabditis Genetics Center was used as a wild-type reference.

Larval Arrest/Lethality, Survival and HIM

Hermaphrodites were harvested from NGM plates to establish synchronized L1 stage larvae, following protocols outlined in [

25,

35]. The larvae were then incubated in 180 µL of the herb extract solution and transferred to a 96-well plate. After gentle agitation, the plates were incubated at 20 °C for 24 hours, with continuous monitoring of phenotypic changes for up to 48 hours. To assess survival, worm mobility was tracked after 24 hours of exposure to the herbal extracts. The brood size was defined as the total number of eggs laid by each individual worm over a 4-5 day period post-L4 stage. Larval arrest or lethality was determined as the percentage of hatched worms that did not survive to adulthood. The male proportion in the population was also calculated, representing the percentage of adult males in each group. Statistical significance between different genotypes was assessed using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test ( 95% confidence interval). All experiments were repeated in triplicate. This protocol was adapted from Kim and Colaiacovo[

35].

LC‒MS Analysis

LC‒MS analysis was performed as described previously [

1,

22]. The results were validated against a standard sample database. All compounds identified were confirmed using this rigorous method.

Monitoring the Growth of E. coli

The growth of

E. coli OP50 in the presence of herb extracts was evaluated by measuring optical density (OD) at 600 nm, as previously described in [

1,

36]. The herb extracts were tested for their antibacterial effects by monitoring bacterial growth under 0.03 µg/mL of each extract.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence staining of whole-mount gonads was performed as described in[

25,

27,

37]. Primary antibodies used included rabbit anti-pCHK-1 (1:250, Cell Signaling, Ser345), and secondary antibodies were Cy3 anti-rabbit (1:300, Jackson Immunochemicals).

pCHK-1 Foci

pCHK-1 foci measurement was performed as described in [

25,

27]. Five to ten germlines per treatment were analyzed. Statistical comparisons were conducted using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test or a T test, with a 95% confidence interval.

Quantitation of Germline Apoptosis

Germline apoptosis was assessed by acridine orange staining in age-matched (20 hours post-L4) animals, following the method described in [

38]. A Nikon Ti2-E fluorescence microscope was used to score between 20 and 30 gonads per treatment. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, with a 95% confidence interval.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

cDNA was synthesized from RNA extracted from young hermaphrodite worms using the ABscript II First Strand synthesis kit (ABclonal, RK20400). Real-time qPCR was performed using ABclonal 2X SYBR Green Fast Mix (RK21200) in a LineGene 4800 system (BIOER, FQD48A). The initial denaturation step was performed at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 60 °C for 20 seconds, and elongation. A melting curve analysis (60 °C to 95 °C) was conducted to verify the specificity of the PCR products. Tubulin encoding gene tba-1 was used as a reference gene based on microarray data for C. elegans. PCR experiment was repeated at least twice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Methodology: Q.M.; Validation: Q.M.; Investigation: Q.M. and H.-M.K.; Reference collection and verification: A.H. and W.X.; Resources: R.P.B. and H.-M.K.; Writing—original draft: H.-M.K.; Writing—review and editing: R.P.B. and H.-M.K.; Proofreading: Q.M., A.H., W.X., R.P.B., and H.-M.K.; Supervision: H.-M.K.; Project administration: H.-M.K.; Funding acquisition: H.-M.K. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Kunshan Shuangchuang grant award (KSSC202202060) and Start-up grant from Duke Kunshan University to H.-M.K.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Kunshan Shuangchuang Grant Award (KSSC202202060) and Start-up grant from Duke Kunshan University to H.-M.K. We thank members of the Kim laboratory for proofreading, especially Zifei Liu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meng, Q.; et al. Exploring the Impact of Onobrychis cornuta and Veratrum lobelianum Extracts on C. elegans: Implications for MAPK Modulation, Germline Development, and Antitumor Properties. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, M.; et al. Boraginaceae. In Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Aquifoliales, Boraginales, Bruniales, Dipsacales, Escalloniales, Garryales, Paracryphiales, Solanales (except Convolvulaceae), Icacinaceae, Metteniusaceae, Vahliaceae; Kadereit, J.W., Bittrich, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 41–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ovczinnikova, S. The synopsis of the subtribe Echinosperminae Ovczinnikova (Boraginaceae) in the flora of Eurasia. Novit. Syst. Plant. Vasc. 2010, 41, 209–272. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.-F.; Zhang, M.-L.; Cohen, J.I. Phylogenetic analysis of Lappula Moench (Boraginaceae) based on molecular and morphological data. Plant Syst. Evol. 2013, 299, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-j. A STUDY ON THE GENUS LAPPULA OF CHINA. Bull. Bot. Res. 1981, 1, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, C.M.; et al. Novedades de flora soriana, 1. Flora Montiberica 2020, 76, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.-H.; et al. Lappula effusa (Boraginaceae), a new species from Xinjiang, China. Phytokeys 2024, 243, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovczinnikova, S. A new species Lappula botschantzevii (Boraginaceae) from the Northern Africa. Phytotaxa 2021, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candolle, Augustin Pyramus de and Candolle, Alphonse de, Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis, sive, Enumeratio contracta ordinum generum specierumque plantarum huc usque cognitarium, juxta methodi naturalis, normas digesta. Vol. v.10 (1846). 1846: Parisii, Sumptibus Sociorum Treuttel et Würtz, 1824–1873.

- Khoshsokhan-Mozaffar, M.; Sherafati, M.; Kazempour-Osaloo, S. Molecular phylogeny of the tribe Rochelieae (Boraginaceae, Cynoglossoideae) with special reference to Lappula. Annales Botanici Fennici 2018, 55, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; et al. A New Quinolone Alkaloid with Antibacterial Activity from Lappula Echinata. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs 2005, 36, 490–492. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; et al. The Protective Effect of Lappula Echinata Gilib Extract LEGPS-II on Oxidative Damage in Mouse Macrophages. Journal of Tianjin Medical University 2012, 18, 412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; et al. A study on the anti-diarrhea mechanism of abstract from Lappula Echinata Gilib. Journal of Tianjin Medical University 2009, 15, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, L.; et al. Process Development of Lappula squarrosa Oil Refinement: Monitoring of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in Boraginaceae Seed Oils. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2014, 91, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaul, N.C.; et al. Insulin/IGF-dependent Wnt signaling promotes formation of germline tumors and other developmental abnormalities following early-life starvation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, D.Y.; Colaiacovo, M.P. Meiotic development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2013, 757, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duronio, R.J.; et al. Sophisticated lessons from simple organisms: appreciating the value of curiosity-driven research. Disease models & mechanisms 2017, 10, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami, K. Frailty and Caenorhabditis elegans as a Benchtop Animal Model for Screening Drugs Including Natural Herbs. Front Nutr 2018, 5, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, J.; Horvitz, H.R.; Brenner, S. Nondisjunction Mutants of the Nematode CAENORHABDITIS ELEGANS. Genetics 1979, 91, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquin, O.; et al. Progression from a stem cell-like state to early differentiation in the C. elegans germ line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107, 2048–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; et al. Histone Demethylase AMX-1 Regulates Fertility in a p53/CEP-1 Dependent Manner. Front Genet 2022, 13, 929716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Borris, R.P.; Kim, H.M. Torenia sp. Extracts Contain Multiple Potent Antitumor Compounds with Nematocidal Activity, Triggering an Activated DNA Damage Checkpoint and Defective Meiotic Progression. Pharmaceuticals.

- Zhang, X.; et al. Histone demethylase AMX-1 is necessary for proper sensitivity to interstrand crosslink DNA damage. PLoS Genet 2021, 17, e1009715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.R.; et al. Caenorhabditis elegans HUS-1 is a DNA damage checkpoint protein required for genome stability and EGL-1-mediated apoptosis. Curr Biol 2002, 12, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.M.; Colaiacovo, M.P. ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the C. elegans Germline. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marechal, A.; Zou, L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Colaiacovo, M.P. New Insights into the Post-Translational Regulation of DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2015, 200, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidi, S.; et al. Chk1 suppresses a caspase-2 apoptotic response to DNA damage that bypasses p53, Bcl-2, and caspase-3. Cell, 2008, 133, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Ferulic acid exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by inducing autophagy and blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol Cell Toxicol 2022, 18, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.Y.; et al. Antitumor Effects of Ursolic Acid through Mediating the Inhibition of STAT3/PD-L1 Signaling in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.Y.; et al. Anticancer activity of oleanolic acid and its derivatives: Recent advances in evidence, target profiling and mechanisms of action. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 145, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; et al. Ergosterol peroxide inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth through multiple pathways. Onco Targets Ther 2017, 10, 3467–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Limonin induces apoptosis of HL-60 cells by inhibiting NQO1 activity. Food Sci Nutr 2021, 9, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S. , The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics, 1974, 77, p. 71-94.

- Kim, H.M.; Colaiacovo, M.P. DNA Damage Sensitivity Assays in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-Protocol 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, S.M.A.; et al. Enhanced Healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans Treated With Extracts From the Traditional Chinese Medicine Plants Cuscuta chinensis Lam. and Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 604435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaiacovo, M.P.; et al. Synaptonemal complex assembly in C. elegans is dispensable for loading strand-exchange proteins but critical for proper completion of recombination. Dev Cell 2003, 5, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.O.; et al. Caenorhabditis elegans msh-5 is required for both normal and radiation-induced meiotic crossing over but not for completion of meiosis. Genetics 2000, 156, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Dose-Dependent Nematocidal Effects of Lappula patula Extracts on C. elegans Survival and Development, with No Impact on OP50 Growth. (A) Lappula patula extracts significantly reduce the survival and development of C. elegans. The effects were evaluated by treating worms with different concentrations of L. patula extracts (0.03, 0.3, and 3 µg/mL indicated by brown, orange and grey color, respectively) and monitoring their survival, adult formation, and male (HIM) phenotype over a 48-hour period. A clear inverse relationship was observed between the dose of the herbal extract and the survival and adult worm percentages, indicating that higher concentrations of L. patula extract led to a marked decrease in worm viability and maturation. However, the percentage of males did not exhibit a dose-dependent trend, suggesting that the disruption in sex chromosome segregation may not be directly influenced by the dosage of the extract. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed T-test, with **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001, comparing control (+DMSO) with treated samples. (B) To evaluate whether the nematocidal effects of Lappula patula could be attributed to an inhibition of bacterial growth, we assessed the growth of OP50 in the presence of L. patula extract. Over a 24-hour incubation period, no significant inhibition of bacterial growth was observed at 0.03 μg/mL of L. patula extract.

Figure 1.

Dose-Dependent Nematocidal Effects of Lappula patula Extracts on C. elegans Survival and Development, with No Impact on OP50 Growth. (A) Lappula patula extracts significantly reduce the survival and development of C. elegans. The effects were evaluated by treating worms with different concentrations of L. patula extracts (0.03, 0.3, and 3 µg/mL indicated by brown, orange and grey color, respectively) and monitoring their survival, adult formation, and male (HIM) phenotype over a 48-hour period. A clear inverse relationship was observed between the dose of the herbal extract and the survival and adult worm percentages, indicating that higher concentrations of L. patula extract led to a marked decrease in worm viability and maturation. However, the percentage of males did not exhibit a dose-dependent trend, suggesting that the disruption in sex chromosome segregation may not be directly influenced by the dosage of the extract. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed T-test, with **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001, comparing control (+DMSO) with treated samples. (B) To evaluate whether the nematocidal effects of Lappula patula could be attributed to an inhibition of bacterial growth, we assessed the growth of OP50 in the presence of L. patula extract. Over a 24-hour incubation period, no significant inhibition of bacterial growth was observed at 0.03 μg/mL of L. patula extract.

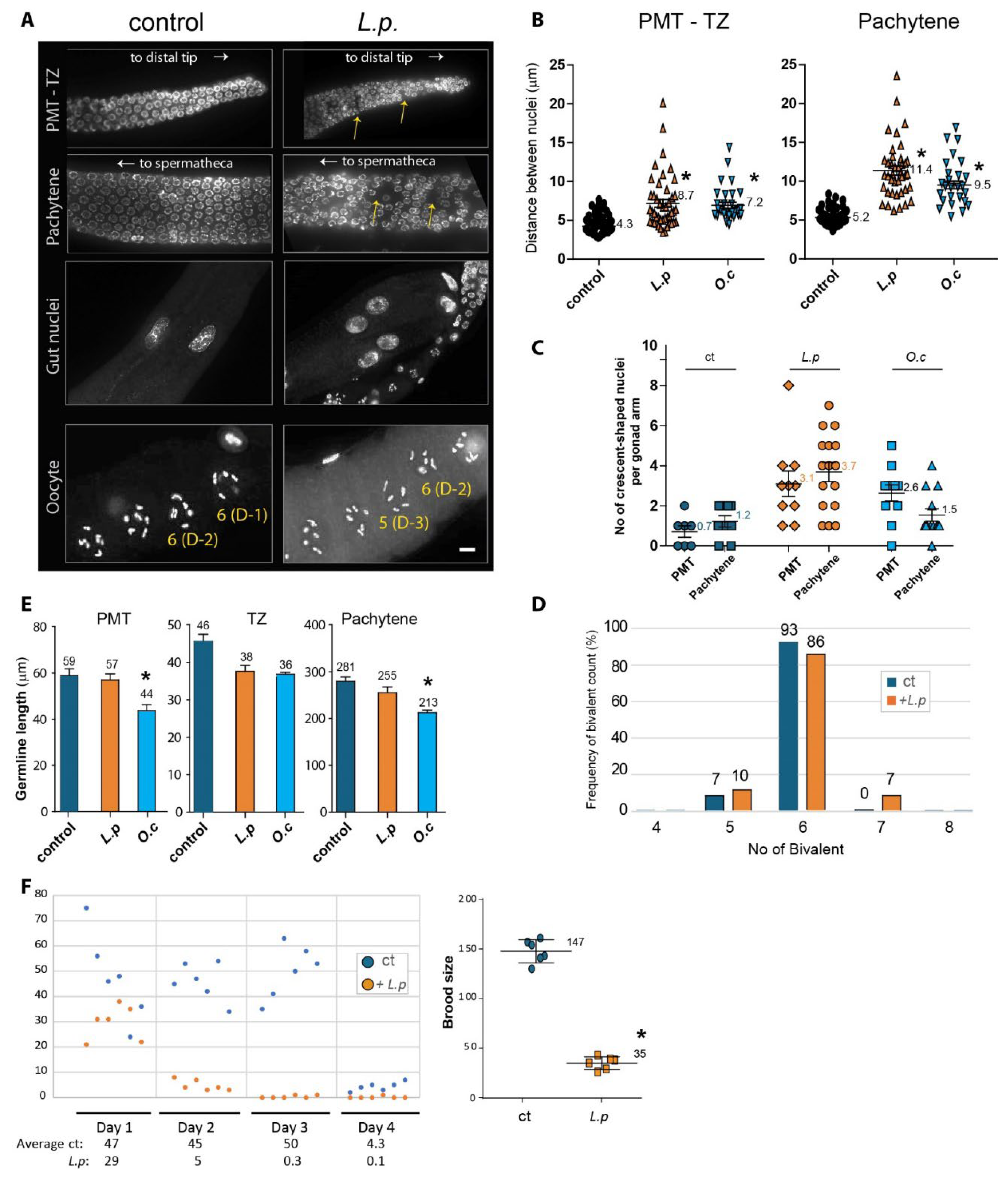

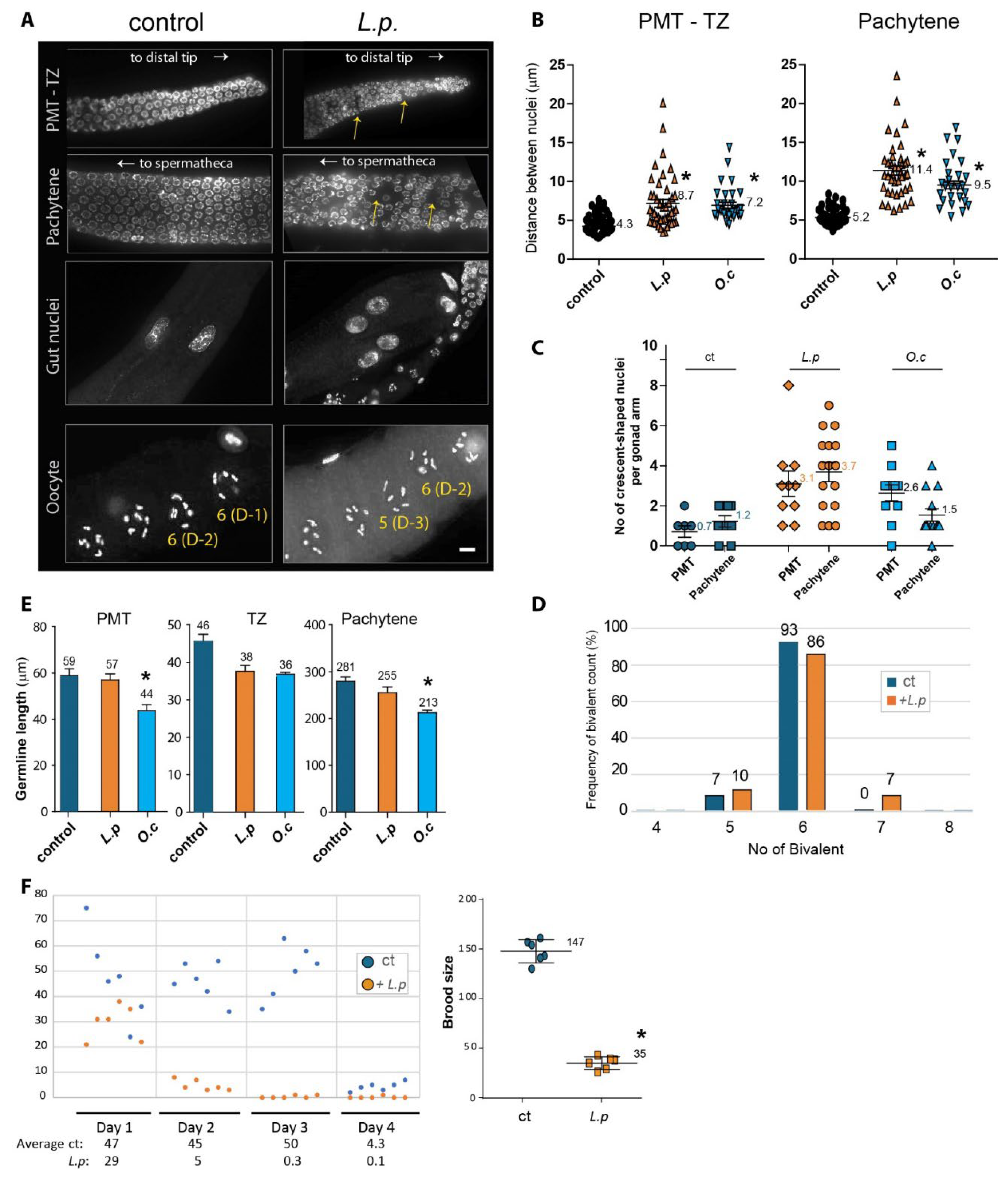

Figure 2.

Disruption of Germline Development Caused by Lappula patula Extracts. (A) DAPI-stained nuclei during germline development. Exposure to Lappula patula extracts led to an increase in gaps between nuclei in the PMT and pachytene, as indicated by the arrows. The distances between adjacent nuclei were greater in worms treated with the herb extract compared to the control (DMSO). Worms exposed to the herbal extract often exhibited fewer DAPI-stained bivalent bodies during diakinesis, suggesting impaired DNA recombination. Scale bar, 2 µm. (B) Quantification of the increased nuclear spacing in the premeiotic tip (PMT) and pachytene stages shown in panel. (C) Quantification of crescent-shaped nuclei in the germline. The number of crescent-shaped nuclei per gonad arm is indicated. (D) Quantification of DAPI-stained bivalents in the germline. The percentage of bivalent is indicated. (E) Quantification of germline size. Germline size, as indicated by the length of the PMT, TZ and pachytene stages, was measured in worms treated with L. patula or O. cornuta extracts. (F) Brood size of Lappula patula-exposed worms. Treatment with Lappula patula extracts led to a notable decrease in the number of offspring produced by hermaphrodite worms over a span of four days. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, as indicated by asterisks. All experiments were performed with C. elegans hermaphrodites, and the data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Disruption of Germline Development Caused by Lappula patula Extracts. (A) DAPI-stained nuclei during germline development. Exposure to Lappula patula extracts led to an increase in gaps between nuclei in the PMT and pachytene, as indicated by the arrows. The distances between adjacent nuclei were greater in worms treated with the herb extract compared to the control (DMSO). Worms exposed to the herbal extract often exhibited fewer DAPI-stained bivalent bodies during diakinesis, suggesting impaired DNA recombination. Scale bar, 2 µm. (B) Quantification of the increased nuclear spacing in the premeiotic tip (PMT) and pachytene stages shown in panel. (C) Quantification of crescent-shaped nuclei in the germline. The number of crescent-shaped nuclei per gonad arm is indicated. (D) Quantification of DAPI-stained bivalents in the germline. The percentage of bivalent is indicated. (E) Quantification of germline size. Germline size, as indicated by the length of the PMT, TZ and pachytene stages, was measured in worms treated with L. patula or O. cornuta extracts. (F) Brood size of Lappula patula-exposed worms. Treatment with Lappula patula extracts led to a notable decrease in the number of offspring produced by hermaphrodite worms over a span of four days. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, as indicated by asterisks. All experiments were performed with C. elegans hermaphrodites, and the data are presented as mean ± SEM.

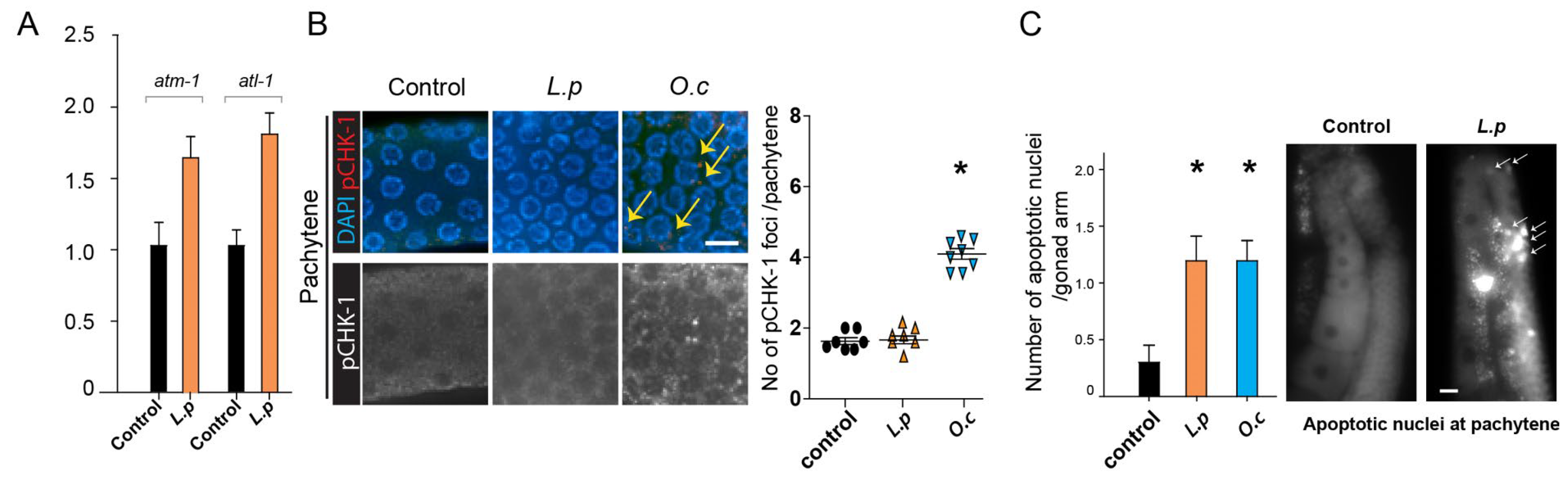

Figure 3.

Lappula patula extracts activate the DNA damage response, leading to upregulation of ATM-1 and ATL-1, and increased Apoptosis, but do not induce pCHK-1 foci. (A) Exposure to Lappula patula extracts significantly enhances the mRNA expression of atm-1 and atl-1, two essential proteins involved in the DNA damage response pathway, confirming the activation of this cellular defense mechanism. atm-1 and atl-1 are critical for activating repair pathways such as homologous recombination and cell cycle arrest, and their upregulation in response to the extract exposure provides evidence of the activation of these protective mechanisms. This upregulation suggests that the extracts may trigger a cellular reaction to DNA damage, which is necessary to repair the compromised genome. (B) No distinct increase in pCHK-1 foci was observed in the germline cells of worms treated with Lappula patula extracts. Despite the elevation of atm-1 and atm-1 level, no significant increase in pCHK-1 levels was observed, implying that while the DNA damage response was triggered, the downstream signaling associated with checkpoint activation, particularly the phosphorylation of CHK-1, did not occur as expected. The extract from O.c was used as a positive control for these experiments, as it has been previously shown to activate the DNA damage response pathway robustly. P=0.825 in control and L.p; P=0.0021 in control and O.c. Scale bar = 2 µm. (C) When examined during the pachytene stage, a significant increase in apoptosis was detected in the germline cells exposed to Lappula patula extracts. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, with asterisks denoting p-values that indicate significant differences between the control and experimental groups. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 3.

Lappula patula extracts activate the DNA damage response, leading to upregulation of ATM-1 and ATL-1, and increased Apoptosis, but do not induce pCHK-1 foci. (A) Exposure to Lappula patula extracts significantly enhances the mRNA expression of atm-1 and atl-1, two essential proteins involved in the DNA damage response pathway, confirming the activation of this cellular defense mechanism. atm-1 and atl-1 are critical for activating repair pathways such as homologous recombination and cell cycle arrest, and their upregulation in response to the extract exposure provides evidence of the activation of these protective mechanisms. This upregulation suggests that the extracts may trigger a cellular reaction to DNA damage, which is necessary to repair the compromised genome. (B) No distinct increase in pCHK-1 foci was observed in the germline cells of worms treated with Lappula patula extracts. Despite the elevation of atm-1 and atm-1 level, no significant increase in pCHK-1 levels was observed, implying that while the DNA damage response was triggered, the downstream signaling associated with checkpoint activation, particularly the phosphorylation of CHK-1, did not occur as expected. The extract from O.c was used as a positive control for these experiments, as it has been previously shown to activate the DNA damage response pathway robustly. P=0.825 in control and L.p; P=0.0021 in control and O.c. Scale bar = 2 µm. (C) When examined during the pachytene stage, a significant increase in apoptosis was detected in the germline cells exposed to Lappula patula extracts. Statistical significance was determined by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test, with asterisks denoting p-values that indicate significant differences between the control and experimental groups. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Fragmentation Patterns of 31 Potential Anti-Tumor Components Identified in Lappula patula Extracts. Out of 112 identified substances, 31 were found to be potential anti-tumor components. The peaks shown represent the breakdown patterns of these 31 components, analyzed using PeakView Analyst TF 1.6 software. Among them, 20 components were identified by proton addition (+H), and 11 by proton removal (-H). The x-axis shows the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and the y-axis shows intensity.

Figure 4.

Fragmentation Patterns of 31 Potential Anti-Tumor Components Identified in Lappula patula Extracts. Out of 112 identified substances, 31 were found to be potential anti-tumor components. The peaks shown represent the breakdown patterns of these 31 components, analyzed using PeakView Analyst TF 1.6 software. Among them, 20 components were identified by proton addition (+H), and 11 by proton removal (-H). The x-axis shows the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and the y-axis shows intensity.

Figure 5.

Lappula patula extract triggers a DNA damage response, which results in disturbances in germline development, enhanced apoptotic cell death, and disruption of the normal meiotic process. These findings suggest that the extract have cytotoxic effects. Furthermore, Lappula patula contains at least 31 compounds known for their potential anti-tumor properties. This presence of bioactive compounds underscores the potential of Lappula patula as a source of natural anti-cancer agents. Given the growing interest in plant-based treatments for cancer, further investigation into the specific compounds and their mechanisms in Lappula patula is essential to fully explore its therapeutic potential.

Figure 5.

Lappula patula extract triggers a DNA damage response, which results in disturbances in germline development, enhanced apoptotic cell death, and disruption of the normal meiotic process. These findings suggest that the extract have cytotoxic effects. Furthermore, Lappula patula contains at least 31 compounds known for their potential anti-tumor properties. This presence of bioactive compounds underscores the potential of Lappula patula as a source of natural anti-cancer agents. Given the growing interest in plant-based treatments for cancer, further investigation into the specific compounds and their mechanisms in Lappula patula is essential to fully explore its therapeutic potential.

Table 1.

Summary of Identified Compounds in

L. patula based on Chemical Categories. The full list and information can be found at

Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Summary of Identified Compounds in

L. patula based on Chemical Categories. The full list and information can be found at

Supplementary Table S1.

| Category |

Compounds |

| Flavonoids |

Rutin, Quercetin-3-o-rutinose, Quercetin, Isoquercetin, Hyperoside, Quercitrin, Isoquercitrin, Luteolin-7-O-β-D-rutinoside, Luteolin 7-O-Rutinoside, Wogonoside, Chrysoeriol, Isovitexin-2”-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, Isoorientin, Luteoloside, Astragalin, Tiliroside |

| Terpenoids |

Citral, 6-Gingerdione, Vomifoliol, β-Caryophyllene, Gingerene/α-Zingiberene, Aromadendrene, Ursolic acid, Betulinic acid, Tormentic acid, 3-Ketooleanolic acid, Acetyloleanolic acid, 2α-Hydroxyursolic acid, Limonin |

| Proanthocyanidins (Tannins) |

Procyanidin A1, Procyanidin B1, Proanthocyanidin |

| Fatty Acids and Lipids |

Linoleic acid, (Z,Z)-9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, Palmitic acid ethyl ester |

| Alkaloids |

Talatisamine, Cimidahurinine, Ikarisoside D, IKarisoside E |

| Stilbenoids |

Trans-THSG, Cis-THSG |

| Lignans |

(+)-Epipinoresinol, Isopinoresinol |

| Steroids & Glycosides |

Ergosterol peroxide, Oleuropein |

| Miscellaneous Compounds |

Uridine, Betaine, Dibutyl phthalate, Cyclo(Ile-Ala), Cyclo(Pro-Ser) |

Table 2.

List of 31 Anti-Tumor Compounds Identified from L.p. Extracts. This table highlights compounds with potential anti-tumor properties identified from the

L.p. extract in heptane using LC-MS. Please see

Supplementary Table S2 for a full description.

Table 2.

List of 31 Anti-Tumor Compounds Identified from L.p. Extracts. This table highlights compounds with potential anti-tumor properties identified from the

L.p. extract in heptane using LC-MS. Please see

Supplementary Table S2 for a full description.

| No |

Compounds |

Chinese name |

Chemical Formula |

Mass (Da) |

| 1 |

Procyanidin A1 |

原花青素A1 |

C30H24O12 |

576.12678 |

| 2 |

Luteolin-7-O-β-D-rutinoside |

木樨草素-7-O-β-D-芸香糖苷 |

C27H30O15 |

594.15847 |

| 3 |

Rosavin Salidroside |

红景天苷 |

C14H20O7 |

300.1209 |

| 4 |

Procyanidin B1 |

原花青素B1 |

C30H26O12 |

578.14243 |

| 5 |

6-Gingerdione |

6-姜辣二酮 |

C17H24O4 |

292.16746 |

| 6 |

Cimidahurinine |

北升麻宁 |

C14H20O8 |

316.11582 |

| 7 |

β-Caryophyllene |

β-榄香烯 |

C15H24 |

204.1878 |

| 8 |

Epimedin E3 |

淫羊藿黄酮次甙E3 |

C26H36O11 |

524.22576 |

| 9 |

Limonin |

柠檬苦素 |

C26H30O8 |

470.19407 |

| 10 |

7-Hydroxy-3,5,6,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone |

7-羟基-3,5,6,3′,4′-五甲氧基黄酮 |

C20H20O8 |

388.11582 |

| 11 |

Tormentic acid |

委陵菜酸 |

C30H48O5 |

488.35018 |

| 12 |

(+)-Epipinoresinol |

表松脂酚 |

C20H22O6 |

358.14164 |

| 13 |

Rutin |

芦丁 |

C27H30O16 |

610.15339 |

| 14 |

Icariin C |

淫羊藿苷C |

C20H16O5 |

336.09977 |

| 15 |

Quercitrin |

槲皮甙 |

C21H20O11 |

448.10056 |

| 16 |

Ergosterol peroxide |

过氧麦角甾醇 |

C28H44O3 |

428.32905 |

| 17 |

Ferulic acid |

阿魏酸 |

C10H10O4 |

194.05791 |

| 18 |

Isoflavone |

拟石黄衣醇 |

C16H12O6 |

300.06339 |

| 19 |

Lucidumoside B |

女贞果苷B |

C25H34O13 |

542.19994 |

| 20 |

2α-Hydroxyursolic acid |

2a-羟基熊果酸 |

C30H48O4 |

472.35526 |

| 21 |

Linoleic acid |

亚油酸 |

C18H32O2 |

280.24023 |

| 22 |

Gingerol |

姜辣醇 |

C19H30O4 |

322.21441 |

| 23 |

Ursolic acid |

熊果酸 |

C30H48O3 |

456.36035 |

| 24 |

Proanthocyanidin |

原花青素 |

C30H26O13 |

594.13734 |

| 25 |

Vomifoliol |

催吐萝芙木醇 |

C13H20O3 |

224.14124 |

| 26 |

Vanillylacetone |

姜酮 |

C11H14O3 |

194.09429 |

| 27 |

Wogonoside |

汉黄芩苷 |

C22H20O11 |

460.10056 |

| 28 |

Emodin-8-O-(6’-methylpyrrolyl) glucoside |

大黄素-8-O-(6’-甲基丙二酰)吡喃葡萄糖苷 |

C24H22O13 |

518.10604 |

| 29 |

Kaempferol 3-O-β-rutinoside |

莰菲醇-3-O-芸香糖苷 |

C27H30O15 |

594.15847 |

| 30 |

Isoacteoside |

异懈皮苷 |

C21H20O12 |

464.09548 |

| 31 |

Quercetin |

槲皮素 |

C15H10O7 |

302.04265 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).